Abstract

In the 2024 UK general election the radical right party, Reform, came third with a 14.3% share of the vote, capturing 5 seats in the House of Commons. This was a breakthrough election for the party, albeit with limited success in relation to the number of seats captured. This paper models the determinants of Reform party voting at the constituency level using Census data to analyze the sources of its support. It examines four distinct but related explanations of Reform voting. The four models can be labeled: anti-mainstream, relative deprivation, identity politics, and democratic dissatisfaction. The analysis shows that they all contribute to explaining Reform support, but dissatisfaction with democracy is marginally the most important.

Introduction

In the 2024 UK general election the radical right party, Reform, came third with a 14.3% share of the vote, capturing 5 seats in the House of Commons Library (2024). This was a breakthrough election for the party, albeit with limited success in relation to the number of seats captured. However, the change in support for the party can be judged by comparing its performance in the previous general election in 2019. In that election it was known as the Brexit party, and it won a 2% vote share and captured no Parliamentary seats at all (House of Commons Library, 2020).

The electoral success of the party should be seen as part of a trend which is visible across many democracies. This trend relates to the success of radical right-wing populist parties in recent elections. One example of this is the Italian election of September 2022, in which the “Brothers of Italy” (FDI/Fdi), the leading right-wing populist party, won the largest vote share with 26% and captured 119 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. Its leader, Giorgia Meloni, subsequently became the Prime Minister (Fella, 2022).

A second example relates to the June 2024 elections to the French National Assembly. This was a snap election called by the French President Emanuel Macron and the National Rally, the leading radical right populist party in France led by Marine Le Pen was the main winner. The party increased its representation in the National Assembly from 89 seats in the previous contest to 125 seats (Fella, 2024).

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, Donald Trump won the US Presidential election in November 2024 with a right-wing populist agenda. He obtained 312 Electoral College votes compared with 226 for his Democrat rival Kamela Harris and just under 50% of the vote share, compared with her share of just over 48%.1 It was a major victory for right-wing populism in the United States.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the sources of electoral support for Reform in the UK general election of 2024. There is a large and growing literature on radical right parties and several theories have been put forward to explain their electoral performance (Mudde, 2007; Oesch, 2008; Benczes and Szabo, 2023). This paper will examine four related explanations of the electoral performance of Reform contributing to a general theory of support for these parties. The analysis is at the aggregate level looking at the performance of the party in the 632 constituencies in Great Britain. This excludes Northern Ireland because it has its own distinctive party system.

We begin by briefly reviewing the literature on radical right-wing parties to situate the analysis. This is followed by a section which sets out a general theory of radical right populist voting that incorporates different accounts into one overall explanation. We then examine the Data and Methods used in analyzing Reform voting in the 2024 general election. This is followed by a section that examines constituency level indicators of the rival theoretical accounts and estimates their impact on Reform voting. A section on diagnostic tests of the theories follows and the paper concludes with a discussion of the results.

A brief review of the literature on populism

The literature on populism is voluminous and so cannot be fully reviewed here. But we will concentrate on the twin questions of defining populism and determining the sources of populist support. The earliest literature on radical right parties was preoccupied with defining populism both as an ideology and as a programme for parties seeking office under a populist banner. In a review of various definitions of right-wing populism Cas Mudde wrote:

“Populism is an essentially contested concept, given that scholars even contest the essence and usefulness of the concept, while a disturbingly high number of scholars use the concept without ever defining it” (Mudde, 2007, p. 27).

Mudde introduced a definition of populism which subsequently became quite influential. He defined it as:

“an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people' versus ‘the corrupt elite', and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde, 2004: p. 543).

He went on to refine this definition by arguing that populism as a “thin centred” set of ideas which do not constitute an ideology, but which are associated with each other (Mudde, 2017).

More recently populism has been defined in terms of three different but related concepts (Norris, 2020). Firstly, as an ideology, equivalent to liberalism or communism, but much less complex. A second approach has defined it as an “ideational” phenomenon, or a looser set of related ideas which do not constitute an ideology, but which nonetheless are associated with each other. This is a similar approach to the definition by Mudde (2017). To illustrate this, antagonism toward domestic elites and immigrants are linked to each other, since they share a dislike of the “other” in society, but this is not a coherent ideology. Rather they are psychological beliefs which can be associated with the personalities of some people (Adorno, 1950; Feldman and Stenner, 1997; Stenner, 2005).

A third approach is to define populism as a form of rhetoric or discourse (Laclau, 2005; Feldman, 2013; Weyland, 2017). The focus here is on popular narratives and strong rhetoric which can create and reinforce populist ideas in the minds of voters. In this respect a charismatic leader able to mobilize discontents among the voters is a crucial ingredient of the success of these parties.

More generally the comparative literature suggests that there are distinct varieties of populist parties (Caiani and Graziano, 2019). The PopuList database of parties in Europe classifies these into three different groupings (Rooduijn et al., 2024). The first is the extent to which populist parties are antagonistic to existing elites. Some parties are more opposed to elites than others, manifest in the way they campaign. In the case of Britain, Reform and the English Defense League are both radical right parties, but the former favors democratic means to advance their agenda, while the latter engages in street demonstrations which often turn violent (Pilkington, 2016).

The second distinction made in the PopuList database is between radical left and radical right parties. The former reject capitalism and free-markets commonly advocating revolution, at least in theory. In contrast, the latter are nativist and authoritarian believing that the nation should be ethnically homogenous which leads them to be hostile to immigration. In addition, radical right parties stress the importance of maintaining the social order and applying severe punishments for criminals.

Finally, the third type are Eurosceptic parties which emphasize opposition to further European integration, believing the nation state is the ultimate source of legitimate authority which should not be overruled by international institutions such as the European Union. These parties often compete in elections with a policy of leaving the European Union or opposing their country joining in the first place.

In his discussion of the determinants of radical right populism in Western Europe Oesch (2008) argues that there are three broad hypotheses which explain the growth in support for these parties. One stresses economic determinants, related to fears about wage pressures and competition over housing, employment and welfare provision, particularly in working class communities.

A second is related to cultural issues, particularly the perception that immigration is a threat to national identities and to the local character of traditional communities. A third argues that dissatisfaction among the voters with the way democratic institutions work in a country is also a source of support. In his analysis Oesch found that questions of community and identity were more important than economic grievances, while dissatisfaction with democracy was important in some though not all countries. With this framework in mind, we look at these factors in more detail.

The economic dimension has been extensively researched. In a review paper Benczes and Szabo (2023) argue that there are demand and supply forces at work in promoting economic populism. On the demand side they highlight the importance of economic shocks such as the financial crash in 2008 and the COVID19 pandemic which created economic disruption, inflation and unemployment (Mian et al., 2014). On the supply side they make the point that populist policies such as raising tariffs and restricting immigration reinforce the problems arising from these economic shocks. In other words, the demand side factors are likely to be in conflict with the supply side factors.

There is good evidence to suggest that unemployment and inflation boosts support for populist parties, particularly when the response to economic shocks by incumbent parties involves austerity measures. The literature suggests that austerity is an ill-judged response to the growing demand for state spending resulting from these crises because it makes the problems worse (Jackman and Volpert, 1996; Golder, 2003; Borges et al., 2013; Funke et al., 2016). However, again there is a paradox at work in relation to policymaking because responding to these crises with “mercantilist” policies such as tariffs on imports and restrictions on skilled immigration are likely to make things worse (Conti, 2018; Funke et al., 2023).

An additional problem is that the recovery from a pandemic the size and impact of COVID in 2020 can be long and difficult. One large scale comparative study conducted over a long period of time showed that some economies never fully recover from serious pandemics (Cerra and Saxena, 2008). Surprisingly, this research showed that it was easier to recover from economic shocks caused by wars than those caused by pandemics. This is because wars primarily destroy physical capital assets such as factories and infrastructure which can be rapidly rebuilt when peace returns. In contrast, pandemics destroy skilled labour and human capital, making the recovery much slower because they are harder to replace.

Another aspect of the economics of populism is globalization, in which large international corporations have moved production to lower wage countries such as China and Vietnam (Bergh and Karma, 2021). This removes highly skilled and well-paid jobs from communities in developed countries which causes unemployment and wage reductions. This in turn polarizes politics and attracts support for populist parties. However, these developments can be ameliorated to some extent by governments introducing welfare support to compensate deprived communities (Swank and Betz, 2003). That said, the economic shocks put tight limits on the ability of countries to finance further welfare spending as a means of countering populism.

Turning to the issue of identify, much of the work on this has its origins in social identity theory (Tajfel, 1978). Populists argue that there are irreconcilable differences in norms, identities and interests between elites and the people, but also between different ethnic groups. This involves exaggerating both intra-group homogeneity and intergroup differences. However, an experimental study in 15 European countries showed that an anti-elitist identity frame in messaging can persuade voters to support populist parties, while framing this in terms of ethnic divisions is less effective (Bos et al., 2020).

Despite this, a robust finding is that immigration boosts support for populist parties on cultural and identity grounds as well as in relation to concerns about jobs wages and public services (Ivarsflaten, 2008; Hawkins et al., 2012). Some of this literature examines psychological theories about what triggers “fear of others” in response to immigration (Bakker et al., 2015). The idea is that rapid changes in communities resulting from an influx of large numbers of culturally and ethnically diverse groups triggers discontent among the indigenous population.

It is apparent that economic and identity drivers of populism are related to each other with links to long standing theories about relative deprivation as a determinant of political action (Runciman, 1966). Relative deprivation refers to the gap between an individual's expectations of their own status and prosperity and their actual experiences. A large gap between the two can trigger political discontent, protests and rebellions (Gurr, 1970; Mueller, 1979). Mass immigration is one of the triggers for such developments. That said, there is also evidence to show that communities tend to habituate to these developments over time (Claassen and McLaren, 2022).

As far as discontent with democracy is concerned the most common version of this idea is that a “democratic deficit” exists in contemporary democracies, and this boosts support for populist parties. This is consistent with the earlier definition of populism which stresses the conflict between “elites” and the “people”. William Galston expresses this idea writing that populism represents

“an illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism and thus is less an attack on democracy than a corrective to a deficit thereof” (Galston, 2018: p. 11).

More generally, there are concerns that mainstream parties no longer represent the voters and for a variety of reasons have become disconnected from the wider electorate (Schattschneider, 1960; Crouch, 2020). One manifestation of this is the widespread loss of trust in parties and in governments and what Peter Mair described as an indifference to politics among large numbers of voters (Mair, 2013). His point is that large numbers of citizens think that the political system is not relevant to them and their everyday concerns.

He developed the “cartel party” thesis which argues that mainstream parties collude rather than compete among themselves in elections. Their aim is to exclude new and insurgent parties from government and so protect their collective interest (Katz and Mair, 1995; De Vries and Hobolt, 2020). This idea was formalized very early on by Downs (1957) whose model shows that in two party systems the parties would converge on the same policy positions occupied by the median vote on the left-right ideological dimension. This means that their policies would be indistinguishable from each other, even though their campaign rhetorics would differ.

A third feature of this discussion is the idea that experts are superior to politicians when it comes to making long-term decisions about society's welfare (Majone, 1996). Politicians work on short-term solutions to political problems in the hope that successful outcomes will emerge before the next round of elections. If successful policies take a long period to implement and involve controversial short-term decisions, they are likely to be neglected.

Turning to the role of political institutions in democracies, they have a significant impact on populist parties. This is particularly true of the electoral system. The single member district or first past the post electoral system restricts the growth of these parties (Becher et al., 2023). The is evident in the case of Britain where the five Reform MPs each represented nearly 35 times the number of voters than the Labour MPs elected in the 2024 general election (House of Commons Library, 2024).

Reform combines different elements of the populist model. It is a radical right party which is both nativist and Eurosceptic. The former is often associated with racism, but the party does not explicitly support racial discrimination. This can be seen in the 2024 election party manifesto which strongly advocates reductions in immigration, giving it a distinct nativist character, but it contains no racist language or calls for racial discrimination (Reform, 2024).

Reform's predecessor party was known as the Brexit party and before that the United Kingdom Independence Party. There has been some interesting research on these earlier incarnations of the party (Ford and Goodwin, 2014; Eatwell and Goodwin, 2018). In particular UKIP campaigned strongly for British withdrawal from the European Union, and when this was achieved in the referendum vote of 2016, it changed its name to the Brexit party to emphasize the importance of fully delivering UK withdrawal (Whiteley et al., 2024).

It campaigned as the Reform party in the 2024 general election to widen its political appeal further and move away from the focus on leaving the European Union taken by its predecessor parties. It ramped up campaigning on other issues, notably immigration. That said, Reform continues to support Eurosceptic policies, calling for an immediate scrapping of any remaining EU regulations currently applying to Britain. At the same time, it also adopts an anti-elite rhetoric. This is illustrated in the introduction to the party's manifesto in 2024. The party leader, Nigel Farage, wrote:

“We are ruled by an out-of-touch political class who have turned their back on our country” (Farage, 2024).

In the next section we focus on placing these ideas into a unified theory of support for radical right populist parties.

A unified theory of populist support

The common underlying theme in this review of the determinants of support for populist parties is that of policy failure. Whether it is in relation to economic policies, immigration, identity politics in the face of rapid economic and cultural changes, or voter trust in the state to listen and act on their concerns the unifying theme is the same. It is a failure of the state to deliver policy outcomes that the voters want. In short, the common denominator is a generalized failure of valence politics.

The concept of valence politics has traditionally been applied to political parties in a context of electoral politics. The term was introduced by Stokes (1963) in a critique of spatial models of party competition. He argued that electoral politics was dominated by valence rather than spatial issues. As is well-known spatial issues measure divisive policies linked to questions such as the balance between taxation and spending, or whether Britain should leave or remain a member of the European Union. In contrast valence issues concern policy objectives that are widely supported such as delivering economic prosperity, ensuring security in the form of freedom from crime and terrorism and providing effective public services.

In valence theory electoral competition is about which party or coalition of parties can best deliver the consensus policy objectives, rather than disagreements about policy goals. Empirical work shows clearly that valence issues dominate spatial issues when it comes to explaining voting behavior in Britain (Clarke et al., 2004; Whiteley et al., 2013). That said, both types of issues make contributions to explaining voting behavior.

With this in mind, we can introduce the concept of state valence failure as the underlying determinant of the rise of populist politics. This idea applies to left-wing populist parties as well as right wing parties like Reform. State failure is at the heart of populist policies. This can be defined as a failure to deliver on consensus policies that voters want but also to manage identity conflicts arising from economic and social change as well as ensuring that the institutions of democracy work well. Valence failure has traditionally focused on parties delivering policies which determine their electoral success of failure. The present argument is that this applies much more broadly to the state itself. The concept needs to be generalized to the level of the state from its origins in understanding party strategies.

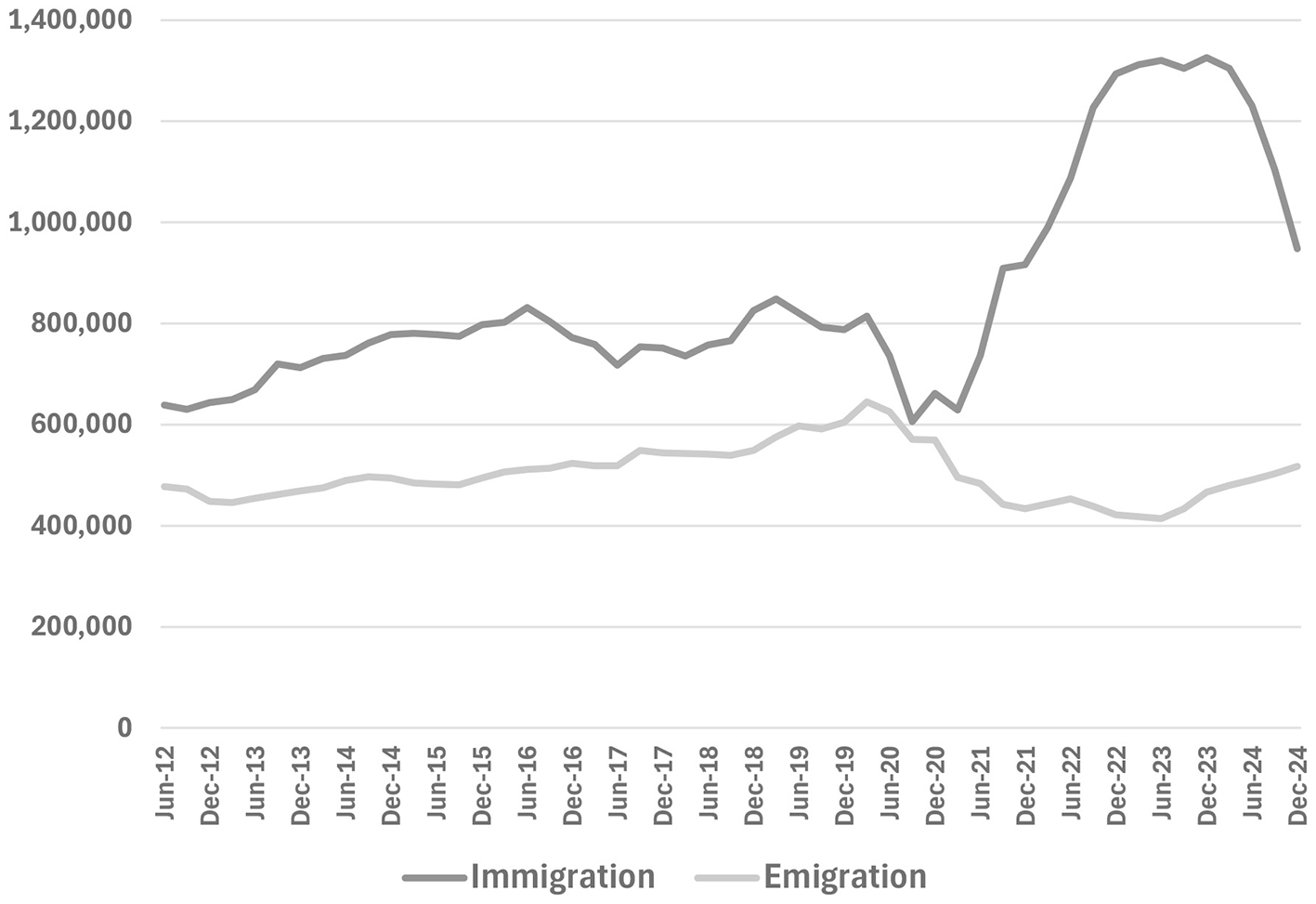

A key reason why this is state failure and not simply failure of incumbents is because all three mainstream parties of government over the last 15 years have failed to deal with the issue of immigration. This was true of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government in the run-up to the referendum vote in 2016 (Clarke et al., 2017). Similarly, the Conservative government following the 2015 general election also failed (Whiteley et al., 2024). More recently Labour has been criticized for not fixing the problem even though as Figure 1 shows net migration is now declining. When all mainstream parties of government fail to deliver what the voters want it becomes a systems failure not a party failure.

Figure 1

Immigration into and emigration from Britain 2012–2024 (quarterly data). Source: ONS.

Figure 1 identifies the failure of the British state to limit net migration into the country in the run-up to the 2024 general election. It uses quarterly data from 2012 to 2024 to show how immigration and emigration into Britain trended over time.2 It is noteworthy that immigration fell slightly, and emigration increased modestly after the Brexit referendum in 2016. However net immigration subsequently ballooned after the 2019 general election and did not significantly decline until after Labour was elected in 2024. Immigration played a key role in explaining the rise in support for Reform since it was a highly salient issue during this period (Whiteley et al., 2024).

There are of course other possible explanations for changes in support for Reform besides state valence failure. It can be argued, for example, that ideological beliefs captured by spatial models of party competition are relevant and the rise of political entrepreneurs taking advantage of voter discontent is also important. There are significant differences between left-wing and right-wing parties in relation to their stances on immigration and identity politics which are captured in the Party Manifesto project data (Budge et al., 2001). This is something particularly true of left-wing and right-wing populist parties suggesting that polarization determines populist support.

That said, there is a weakness in spatial theories of party competition as explanations for rising support for populist parties like Reform. The traditional two-party spatial model applied to Britain predicts convergence between mainstream parties (Downs, 1957). However, the rise of populism has produced divergence and fragmentation of the party system, not convergence around a median voter. More generally an explanation of the rise in populism has to explain why ideological beliefs have changed or political entrepreneurs like Nigel Farage have been able to take advantage of voter discontent. Policy failure by the state and incumbent parties provides such an explanation.

To round out this discussion it is useful to set out hypotheses which test the determinants of support for Reform:

-

H1: Voters disillusioned with state delivery by mainstream parties in relation to widely accepted valence policy goals are more likely to vote Reform.

-

H2: Voters who feel left behind in relation to the rest of society in their own economic circumstances and social status are more likely to vote Reform.

-

H3: Voters who feel threatened by economic and cultural changes in society and have a narrow sense of national identity are more likely to vote Reform.

-

H4: Voters who feel that democratic institutions no longer represent them and their interests are more likely to vote Reform.

To test these ideas, the hypotheses are operationalised with a variety of variables to test the overarching concept of state valence failure, and we discuss these next.

Data and methods

The analysis is conducted at the constituency level involving 632 Westminster Parliamentary constituencies in England, Wales and Scotland. There is a long tradition of electoral analysis based on aggregate data in Britain, particularly in the field of political geography (Miller, 1977; Budge and Farlie, 1983; Johnson et al., 1988, 2001). Since elections in Britain are decided by the party winning most seats in the House of Commons, and not most votes in the country this approach is adopted in the present paper.

Aggregate analysis has its advantages. It avoids the problems of using self-reported turnout in individual level surveys which are known to be inaccurate (Bernstein et al., 2001). In addition, it bypasses the problems associated with the multi-level modeling of individuals nested in constituencies. Often the assumptions required for efficient estimation of these models are not met in practical applications making them potentially misleading (Buttice and Highton, 2017).3

The source of election data is the House of Commons Library (2024). The constituency social and economic characteristics are derived from the Office of National Statistics 2021 Census data which is aggregated to the Parliamentary constituency level.4 Such data avoids any problems of endogeneity or two-way causation which can be feature of some voting models.

The method used is OLS regression modeling with the Reform percentage vote share in each constituency as the dependent variable (Table 1). The models estimate standardized coefficients of the predictors to facilitate comparisons between variables along with the usual significance test statistics. The diagnostic tests include Aikaike information criterion statistics (AIC) to evaluate nested models, the standard R-squared statistic and Variance Inflation Factors which are used to identify multicollinearity. The AIC penalizes models with large numbers of predictors which might artificially improve the fit in comparison with more parsimonious models Burnham and Anderson, (2002).

Table 1

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative vote % | 23.6 | 10.8 |

| Labour vote% | 35.5 | 13.9 |

| Liberal democrat vote% | 11.7 | 13.2 |

| Green vote % | 6.9 | 5.4 |

| Reform vote % | 14.8 | 7.2 |

| SNP vote % | 2.7 | 8.7 |

| PC vote % | 0.75 | 4.2 |

| Relative income | 100.7 | 12.0 |

| Economically inactive % | 34.5 | 5.6 |

| British identity | 51.1 | 14.8 |

| English identity | 14.1 | 6.0 |

| Scottish identity | 5.9 | 19.0 |

| Welsh identity | 2.8 | 12.4 |

| Not-white % | 15.9 | 16.9 |

| Turnout % | 59.9 | 7.0 |

| Invalid votes | 180 | 105 |

| Independent votes% | 1,582 | 2,903 |

Descriptive statistics N = 632.

To clarify the four hypotheses introduced earlier, we can describe four different models. They are (1) anti-mainstream, (2) relative deprivation, (3) identity politics, and (4) democratic dissatisfaction. Each of these examines different aspects of state valence failure, linked to the hypotheses.

The anti-mainstream model is the traditional valence model of electoral support, which focuses on parties that have recently been in government and therefore able to influence policies. It is most relevant to hypothesis H1. The devolved Parliaments in Wales and Scotland are included in this definition since they have considerable powers. Accordingly, the models examine the effect of support for the five mainstream parties in Britain, namely, the Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, the Scottish National Party and Plaid Cymru on Reform voting. These parties have been in government either in Westminster, in the Holyrood Parliament in Scotland, or in the Welsh Senedd.

The Conservative party controlled the Westminster Parliament prior to the 2024 election having won the election of 2019. Accordingly, they should have a big impact on the Reform vote. However, we also include the two other traditional national parties, Labour and the Liberal Democrats, because the former was in government from 1997 to 2010 and the latter in coalition with the Conservatives from 2010 to 2015. In addition, Labour is currently in power and the Scottish National Party has been in government or in coalition in Scotland since 2007. Finally Plaid Cymru was in coalition with Labour in the Welsh Senedd from 2007 to 2011. If as H1 suggests, voters are discontented with all mainstream parties with a history of recent incumbency, then this should boost support for Reform producing negative relationships between Reform and the other parties.

If we examine bivariate correlations between Reform voting and support for each of the other mainstream parties, this is potentially misleading. This is because there are complex interactions between support for the different parties at the constituency level. For example, if Reform took votes from the Conservatives in a constituency, this would indirectly help Labour since they are directly challenged by the Conservatives. Equally in a constituency where Labour was unpopular both Reform and the Conservatives could increase their vote shares at the same time. If so, this would produce a positive relationship between Reform voting and Conservative voting. Other interactions of this type are possible too, and this explains why it is necessary to control for them in the modeling, using multivariate regression models.

Turning to the relative deprivation model, this uses census data to identify two sources of deprivation across constituencies. The first is the difference between the median earnings of full-time workers in a constituency compared with median earnings in all constituencies across Britain. Relative deprivation theory suggests that voters in constituencies below the national median income will tend to support Reform if they feel neglected in relation to the country's overall economic performance. This is the classic phenomenon of voters feeling “left behind” associated with H2. This also implies that constituencies whose wage levels are above the national median income will not experience this effect.

A second predictor from the census which is relevant to feelings of deprivation is the percentage of the population who are not economically active. This includes the unemployed, the retired, the disabled, students, children, and those who look after their homes full-time. This is a very disparate group of people, but it is relevant because one of the most significant developments in the UK labour market since the pandemic has been the growth of economically inactive people (Murphy and Thwaites, 2023; Local Government Association, 2024). A high dependency ratio, that is, large numbers of inactive people relative to the overall population in a constituency is likely to contribute to poverty in those communities. This in turn can give rise to feelings of deprivation in the constituencies most affected, which should increase support for Reform.

The third model focuses on identity politics, and in this case the emphasis is on national identities and H3. The census included questions which asked respondents if they thought of themselves as “British”, “English”, “Scottish”, “Welsh” and so on. Respondents could report multiple identities such as being “British and Scottish” or “British and Welsh”. In the analysis of the model for Britain as a whole, we focus on “British” identity compared with “English” identity. In separate models for England, Scotland and Wales we look at single identities related to each country, again compared with “British” identity. The aim is to determine the extent to which Reform can be regarded as an English nationalist party, equivalent to those in Scotland and Wales, although with rather different objectives than these nationalist parties.

The fourth model, democratic dissatisfaction, is relevant to H4 and is the most challenging one to estimate since there are no direct measures of dissatisfaction with democracy in the census data. Accordingly, we use three variables from the voting data as proxy measures. The first is the percentage turnout in a constituency, which is a good indicator of how many people are interested enough in politics and in the election to participate. The expectation is that Reform will do well in constituencies that have low turnouts, because it is mobilizing protest voters who are dissatisfied with the existing party system and so opt for an insurgent alternative.

The second measure is the percentage of respondents who vote for independents or for one of the many very minor parties standing in the election. The idea here is that if Reform is a protest party running against the traditional party system which underpins democracy it will take votes from minor parties and independent candidates in the election. In the competition for protest votes it will reduce support for these alternatives.

The third measure of democratic dissatisfaction is the number of invalid votes recorded in each constituency. A small number of these can be accounted for by voters making mistakes on the ballot paper. But the large variation in the number of invalid votes across constituencies cannot easily be explained in this way. For example, in the North Cornwall constituency there were 47 invalid votes cast in the election, many of which could be due to mistakes. But in the Cheltenham constituency there were 986 invalid votes, a figure which is not at all consistent with this explanation.

Research shows that voters who spoil their ballots can be classified into two categories: those who simply make a mistake when filling in the ballot and those who are protesting (Kouba and Lysek, 2018). Mistakes are easy to make in countries with complex electoral systems. However, in Britain, the first-past-the-post system ensures that this is not a significant factor because the system is so simple. The bulk of spoilt ballots are protests of various kinds, taking the form of blank ballots, write in candidates, or abusive messages about the government, parties and candidates.

Results

Table 2 contains the standardized coefficient estimates of the predictors in the four models of the Reform vote shares in Britain.5 There is a model for Britain as a whole followed by models for England, Scotland and Wales. The Variance Inflation Factor statistics (VIF) shows that multicollinearity was a concern in the Scottish and Welsh models,6 though not in the overall model for Britain. Accordingly, the Liberal Democrat vote shares were omitted from the specifications in Table 2 in these countries to deal with the problem.

Table 2

| Predictors | Britain (N = 632) | England (N = 543) | Scotland (N = 57) | Wales (N = 32) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Conservative vote | −0.40*** (8.6) | −0.33*** (6.8) | 0.24* (1.7) | −0.80*** (4.5) |

| % Labour vote | −0.73*** (12.3) | −0.72*** (11.0) | 0.05 (0.4) | −0.40* (1.7) |

| % Liberal democrat vote | −0.86*** (17.2) | −0.88*** (16.0) | — | — |

| % Green vote | −0.49*** (14.8) | −0.50*** (13.5) | −0.39*** (3.1) | −0.56*** (3.9) |

| % SNP vote | −0.63*** (17.7) | — | 0.17 (1.4) | — |

| % Plaid Cymru vote | −0.20*** (6.4) | — | — | −0.85*** (3.4) |

| R squared fit statistic | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.53 |

| Aikake information statistic | 3,875.8 | 3,381.7 | 217.5 | 185.8 |

| Variance inflation factor | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

The relationship between Reform voting and support for rival parties in Britain in 2024.

t statistics in parenthesis: ***p < 0.01; *p < 0.10.

The R-square goodness of fit statistics varied from 0.33 to 0.53, so rival parties all have a contribution to make in explaining the Reform vote in Britain as a whole. The diagnostics include the Aikake Information Statistic (AIC). These statistics are not directly comparable to each other in the different models, but they are included because they will prove useful in interpreting the fully specified models reported in Table 3.

Table 3

| Party vote percentages | Britain | England | Scotland | Wales |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative vote % | −0.43*** (11.7) | −0.36*** (9.9) | 0.47*** (4.2) | −0.90*** (3.0) |

| Labour vote % | −0.66*** (12.8) | −0.53*** (9.9) | −0.14 (1.3) | −0.41 (1.1) |

| Liberal democrat vote % | −0.65*** (14.8) | −0.54*** (12.1) | ___ | ___ |

| Scottish national vote % | −0.53*** (11.6) | ___ | −0.08 (0.6) | ___ |

| Plaid Cymru vote % | −0.16*** (5.9) | ___ | ___ | −0.85*** (2.9) |

| Relative income | −0.08*** (3.1) | 0.09*** (3.5) | 0.14 (1.3) | 0.03 (0.1) |

| Economically inactive % | 0.13*** (4.9) | 0.12*** (3.6) | −0.09 (1.1) | −0.03 (0.1) |

| British identity % | −0.18*** (3.9) | −0.03 (1.4) | −0.29 (1.4) | ___ |

| English identity % | 0.45*** (9.7) | 0.48*** (10.9) | ___ | ___ |

| Scottish identity % | — | — | −0.03** (0.1) | ___ |

| Welsh identity % | — | — | — | 0.02 (0.1) |

| Non-white % | −0.12*** (3.4) | −0.07* (3.6) | −0.53*** (2.9) | −0.51* (1.9) |

| % Turnout | −0.27*** (9.3) | −0.30*** (9.6) | −0.63*** (3.8) | 0.15 (0.4) |

| Invalid votes | −0.33*** (17.9) | −0.39*** (20.2) | −0.08 (0.6) | −0.26* (1.6) |

| % Independent votes | −0.29*** (9.6) | −0.24*** (7.5) | −0.11 (1.2) | −0.35** (1.9) |

| R-square fit statistic | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.59 |

| Change in Aikake statistic | 694.5 | 709.9 | 43.3 | 7.6 |

| Variance inflation factor | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.6 |

The encompassing models of Reform voting.

t statistics in parenthesis: ***p < 0.05; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.10.

Looking at the individual coefficients in Table 2, the large number of constituencies in Britain make it possible to estimate effects for the Liberal Democrats alongside the other major parties. In the event the Liberal Democrats provided the strongest challenge to Reform with a negative standardized coefficient of −0.86 in the analysis. Historically, the party has won a high proportion of protest votes in UK elections (Whiteley et al., 2006). These are votes from individuals who support neither Labour nor the Conservatives, the traditional parties of government, and are generally not attached to any party. The size of this effect suggests that the Liberal Democrats and Reform competed strongly for this vote.7

The second largest effect was associated with support for Labour with a standardized coefficient of −0.73, indicating that the challenge to the party was highly significant. The third most important rival to Reform were the Greens with a coefficient of −0.49. The most interesting finding is that the Conservatives who are the major rival party to Reform on the right of British politics had the smallest coefficient in the model of −0.40, setting aside the nationalist parties. This suggests that Reform and the Conservatives were to some extent allies as well as rivals.

Table 4 analyses the four alternative models separately to get a preliminary sense of which are the most important for explaining the Reform vote. At this stage it appears that the Identity politics model explains most variance with an R-square of 0.45. Looking at the coefficients in the identity model the strongest effect by far is English identity (0.88). Clearly, English nationalism plays a very important role in explaining the Reform vote. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact the more inclusive British identity variable has a negative impact on the Reform vote (−0.34). The third variable in the identity model is the number of non-white residents in a constituency which had a relatively small positive effect on Reform voting (0.10). This implies that ethnic divisions in constituencies play a role in increasing support for Reform, but the dominant factor is English national identity.

Table 4

| Party vote percentages | Anti-mainstream | Relative deprivation | Identity politics | Democratic dissatisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Conservative vote | −0.13*** (2.6) | — | — | — |

| % Labour vote | −0.60*** (8.8) | — | — | — |

| % Liberal democrat vote | −0.71*** (12.4) | — | — | — |

| % SNP vote | −0.43*** (11.3) | — | — | — |

| % Plaid Cymru vote | −0.09** (2.6) | __ | __ | __ |

| Relative income | — | −0.31*** (7.6) | — | — |

| % Economically inactive | — | 0.23*** (5.7) | — | — |

| % British identity | — | — | −0.34*** (6.5) | — |

| % English identity | — | — | 0.88*** (15.6) | — |

| % Non-white | — | — | 0.10** (2.2) | — |

| % Turnout | – | – | — | −0.24*** (6.7) |

| Invalid votes | — | — | — | −0.40*** (11.6) |

| % Independent votes | — | — | — | −0.21*** (5.6) |

| R-square fit statistic | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.28 |

| Variance inflation factor | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

Standardized estimates of Reform voting in the 2024 general election in Britain (N = 632).

t statistics in parenthesis: ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05.

The anti-mainstream model is the second in the rankings with respect to the fit statistics. This had an R-Square of 0.30 and the estimates show an interesting phenomenon, namely that while support for all five parties had a negative effect on Reform voting, the second weakest effect was associated with support for the Conservatives (−0.13). This reinforces the earlier conclusion that the competition between the Conservatives and Reform was significantly weaker than between Reform and the other parties with the exception of the Welsh nationalists.

The democratic dissatisfaction model is the third in the rankings in terms of the fit statistics. This contains three variables all of which have a negative impact on the Reform vote. The first is turnout, indicating that when this is high the Reform vote declines (−0.24). Lower turnout is an indicator of political apathy and discontent, suggesting that Reform benefitted from this at the constituency level. Secondly, a high number of invalid votes also reduced support for Reform (−0.40). This is an indicator of dissatisfaction with the established party system in Britain. Essentially Reform picked up support from voters who opted for “none of the above” as far as the traditional parties were concerned. Finally, Reform did well when votes for independents and candidates from very small parties declined, indicating that the party captured many of these protest votes (−0.21).

The relative deprivation model comes fourth in the rankings in relation to fit statistics. In this case the estimates show that when constituency median incomes fall below the national average the Reform vote increases (−0.31). This proxy measure of relative deprivation works as expected with constituencies that are left behind showing greater support for Reform. This conclusion is reinforced by a high dependency ratio involving many people who are not economically active in a constituency (0.23) which boosts the Reform share of the vote. According to the coefficients, relative incomes have a stronger impact on the Reform vote than economic inactivity.

Examining the four models separately provides important insights into relationships but these results are incomplete and subject to specification error in the analysis (Kennedy, 2008, p. 71–89). Each of them omits variables which we know to be important, and this can give a misleading picture. Only a fully specified model with all the relevant variables included will provide an accurate picture of the relative importance of the models. This is done in Table 3.

Table 3 presents encompassing or fully specified models for Britain, England, Scotland and Wales by combining all four models into one. This deals with the problem of possible errors in Table 4 arising from the restricted specifications. Fully specified versions of the models change their importance as explanations of the Reform vote. If we start by looking at the model for Britain first, not surprisingly the rival incumbent parties had a very large impact on Reform voting. Unlike in Table 2 the census variables are incorporated into the analysis in Table 3, but the results as far as rival parties are concerned do not differ greatly from Table 2. The main difference is that the size of the rival party coefficients are smaller which is to be expected given the additional variables. In addition, Labour (−0.66) is the strongest rival to Reform by a tight margin over the Liberal Democrats (−0.65).

The goodness of fit statistics range from an R-square of 0.84 in England to 0.59 in Wales, so the fit statistics are generally high. In addition, we can use the AIC statistics as an alternative measure of fit. This involves comparing the AIC statistics in Table 2 to those in Table 3. Since the latter models have many more variables than the former, it is important to determine if the improvement in fit is merely an artifact of the expanded specification or alternatively a significant improvement in explanatory power. In the event, the AIC statistics are significantly smaller in Table 3 than in Table 2, although the improvement in Wales is rather modest. This means that the encompassing models significantly improve the fit when explaining Reform voting compared with Table 2.

In the Britain model the Conservative vote effect was weaker than the others, but it was nonetheless negative and highly significant (−0.43). In the full specification the Conservatives and Reform were greater rivals than is apparent in Table 2, but the competition between these parties was still significantly less than with the other mainstream parties. Similarly, the SNP was a strong rival to the vote for Reform in Scotland (−0.53), but Plaid Cymru was rather weaker in Wales (−0.16).

Identity politics looms large in Table 3 in the Britain model with English identity having a significant positive impact on the Reform vote (0.45) while the effect of British identity was negative (−0.18). This strengthens the conclusion that English nationalism was a strong driver of support for Reform in the election.

The relative deprivation model played a weaker, though still significant role in explaining support for Reform in Britain. While the effects of low incomes (−0.08) and an economically inactive population (0.13) were weak they were significant. Clearly, the relative deprivation model contributes to the overall picture, but less so than the anti-mainstream and identity politics models.

The same cannot be said about the democratic dissatisfaction model, since this remained a very important influence on the Reform vote in Britain. The strongest effect related to the number of invalid votes in a constituency (−0.33), but the effects relating to turnout (−0.27) and support for independent candidates (−0.29) were also important. Again, many invalid votes, higher turnouts and fewer independents all reduced support for Reform. This is consistent with the general point made earlier that Reform is competing for the “none of the above” protest voters disillusioned with the traditional parties.

Turning next to the separate models for the three countries we observe a rather similar picture in England to the results in Britain as a whole. This is not surprising, given that the number of constituencies in England is so much larger than in Scotland and Wales. With respect to the 57 constituencies in Scotland, there are notable differences compared with the Britain model. Labour had no effect on the vote for Reform in Scotland, something also true of the SNP. Surprisingly, the Conservative and Reform vote shares were positively correlated (0.47),8 indicating that the two parties were allies rather than rivals in that country.

Another important difference between the Scottish and British models relates to identity politics. British identity had no significant impact on support for Reform in Scotland, whereas it had a negative effect on Reform voting in Britain as a whole. In addition, Scottish identity had a relatively weak, though significant negative impact on Reform voting in Scotland. This is consistent with the earlier point that Reform is in many respects an English nationalist party. The growth in Scottish identity over time has favored the SNP rather than a radical right-wing populist party like Reform (Keating, 2020; Scholes and Curtice, 2020). This makes the role of identity in Scottish politics markedly different from England.

The democratic dissatisfaction model had a weaker effect on support for Reform in Scotland than in Britain, since the only variable which had a significant impact on the Reform vote was turnout. As in Britain as a whole, a high turnout had the effect of reducing support for Reform. But the other two variables in that model had no effect on Reform support in Scotland.

Turning finally to the Welsh model, a similar picture emerged as in Scotland. The contest was very much between the Conservatives, Plaid Cymru and Reform in Wales, with Labour support having no impact on the Reform vote.9 The effects of the variables in the other models were negligible in this case, with the exception of support for independent candidates and a weak effect for invalid votes, both of which had negative impacts on the Reform vote.

Overall, the modeling finds support for all four hypotheses set out earlier. Voters disillusioned with state delivery by mainstream parties in relation to widely accepted policy goals are more likely to vote Reform. The left behind are more likely to vote for Reform as are the electors with narrow national identities and who are disillusioned with the way democratic institutions work in Britain.

In the final section the relative importance of the different models estimated in this exercise.

Evaluating the models

Turning finally to the question of which model had most impact on the Reform vote, we can investigate this issue using a dominance analysis (Budescu, 1993). This technique is used to evaluate the relative importance of a predictor variable, or groups of predictors, on a dependent variable in a regression analysis. It does this by investigating different model specifications, so we can determine which, if any, dominates the picture. This is done in Table 5 where the standardized dominance statistics make it possible to rank the four models in order of their importance, when it comes to explaining the Reform vote. In fact, all four models contribute to explaining the Reform vote and the dominance statistics indicate that there is no single outstanding model which is much more predictive than its rivals. At the same time the differences between them are statistically significant.

Table 5

| Party vote percentages | Standardized dominance statistics | Ranking in importance |

|---|---|---|

| Dissatisfaction with democracy | 0.30 | 1 |

| Identity politics | 0.29 | 2 |

| Relative deprivation | 0.21 | 3 |

| Anti-incumbency | 0.20 | 4 |

The model dominance statistics for Britain.

That said, the Democratic Dissatisfaction model has the edge over the other three when it comes to predicting the vote. However, it is closely followed by the Identity model which in turn is slightly more influential than the relative deprivation model, with anti-mainstream model taking fourth place. These differences are not large, but they show that a generalized disillusionment with the way democracy works in Britain is a very important component of support for Reform. This has not been fully recognized in the past since economic deprivation and identity politics tend to be the focus of most analyses.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper highlights the importance of several different factors which have contributed to the remarkable success of the Reform party in winning votes in the 2024 general election. The four models do not of course explain all the factors at work in driving support for the party. Aggregate modeling of this type means that individual level variables such as the personality characteristics of voters or the impact of campaigns on voters cannot be included in the analysis. That said, the high goodness of fit statistics in the Britain analysis, means that the great majority of the variance in Reform voting across constituencies is explained by these models. Reform is a case study of a more widespread phenomenon present across the world's democracies, and by implication these or similar variables will play an important role in explaining the growth of radical right-wing parties elsewhere.

The fact that the democratic dissatisfaction model comes out on top when they are all evaluated in relation to goodness of fit should cause some concern. It implies that state valence failure is more important than anti-incumbency associated with specific governing parties. Given this the results suggest that support for Reform is likely be sustained in the future.

The next general election is due to take place in 2028 or 2029, and these results suggest that Reform will be an important player in that election. This conclusion is reinforced by the importance of the identity model and particularly the growth of English identity at the expense of British identity. This is a major driver of support for Reform in Britain. It highlights a fragmentation of support for the UK political system, and a weakening of what Almond and Verba (1963) described as the “civic culture” in their pioneering study of five democracies more than 60 years ago.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: UK Office of National Statistics 2021 Census data and House of Commons Library Report on the 2024 general election.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

PW: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ https://apnews.com/projects/election-results-2024/?office=P

2.^See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration.

3.^Our approach does not make any inferences about individual voting behavior in violation of the ecological fallacy. See Robinson (1950).

4.^See https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/sources/census_2021_bulk.

5.^Standardized coefficients can be misleading for a number of reasons, but a comparison with the unstandardized versions (not shown), indicates that this is not a problem.

6.^As a rule of thumb VIF statistics which exceed 10 indicate serious multicollinearity in the modeling Kennedy, (2008), p. 199).

7.^Note that a model which explained Reform vote using vote shares from rival parties in the 2019 election would have helped to explain the sources of the Reform vote. However, the revision of constituency boundaries which took place in 2023 make it impossible to compare the 2019 with the 2024 results since there were extensive changes in constituency boundaries.

8.^The Liberal Democrats are omitted due to multicollinearity but the bivariate correlation between Liberal Democrat and Reform voting is Scotland was −0.22.

9.^Liberal Democrat voting and British identity were omitted from this model because of multicollinearity.

References

1

Adorno T. (1950). The Authoritarian Personality. New York, NY: Joanna Colter Books.

2

Almond G. Verba S. (1963). The Civic Culture – Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

3

Bakker B. N. Rooduijn M. Schumacher G. (2015). The psychological roots of populist voting: evidence from the United States, the Netherlands and Germany. Eur. J. Pol. Res.55:302–320. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12121

4

Becher M. Menendez Gonzalez I. Stegmueller D. (2023). Proportional representation and right-wing populism: evidence from electoral system change in Europe. Br. J. Polit. Sci.53, 261–268. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000703

5

Benczes I. Szabo K. (2023). An economic understanding of populism: a conceptual framework for the demand and supply of populism. Polit. Stud. Rev.2, 680–696. doi: 10.1177/14789299221109449

6

Bergh A. Karma A. (2021). Globalisation and populism in Europe. Public Choice189, 51–70. doi: 10.1007/s11127-020-00857-8

7

Bernstein R. Chadha A. Montjoy R. (2001). Overreporting voting: why it happens and why it matters. Public Opin. Q.65, 22–44. doi: 10.1086/320036

8

Borges W. Clarke H. D. Stewart M. C. Sanders D. Whiteley P. F. (2013). The emerging political economy of austerity in Britain. Elector. Stud.32, 396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2013.05.020

9

Bos L. van der Brug W. de Vreese C. (2020). The effects of populism as a social identity frame on persuasion and mobilisation: evidence from a 15-country experiment. Eur. J. Polit. Res.59, 3–24. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12334

10

Budescu D. V. (1993). Dominance analysis: a new approach to the problem of relative importance of predictors in multiple regression. Psychol. Bull.114, 542–551. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.542

11

Budge I. Farlie D. (1983). Explaining and Predicting Elections. London: George Allen and Unwin.

12

Budge I. Klingemann H. D. Volkens A. Bara J. Tanenbaum E. (2001). Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors and Governments 1945–1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

13

Burnham K. P. Anderson D. R. (2002). Model Selection and Multimodel Inference. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

14

Buttice M. K. Highton B. (2017). How does multilevel regression and post-stratification perform with conventional national surveys?Polit. Anal.21, 449–467. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpt017

15

Caiani M. Graziano P. (2019). Understanding varieties of populism in times of crises. West Eur. Polit.42, 1141–1158. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1598062

16

Cerra V. Saxena S. C. (2008). Growth dynamics: the myth of economic recovery. Am. Econ. Rev.98, 439–457. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.1.439

17

Claassen C. McLaren L. (2022). Does immigration produce a public backlash or public acceptance? Time-series, cross-sectional evidence from thirty European democracies. Br. J. Polit. Sci.52, 1013–1031. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000260

18

Clarke H. D. Goodwin M. Whiteley P. (2017). Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

19

Clarke H. D. Sanders D. Stewart M. C. Whiteley P. (2004). Political Choice in Britain.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

20

Conti T. V. (2018). Mercantilism: a materialist approach. Scand. Econ. Hist. Rev.66, 186–200. doi: 10.1080/03585522.2018.1465847

21

Crouch C. (2020). Post-Democracy: After the Crisis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

22

De Vries C. E. Hobolt S. B. (2020). Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

23

Downs A. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

24

Eatwell R. Goodwin M. (2018). National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. London: Penguin Random House.

25

Farage N. (2024). Reform UK Election Manifesto 2024: ‘Our Contract With You'. Reform UK. Available online at: https://assets.nationbuilder.com/reformuk/pages/253/attachments/original/1718625371/Reform_UK_Our_Contract_with_You.pdf?1718625371 (Accessed January 31, 2025).

26

Feldman S. (2013). “Political ideology,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, Eds. L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, and J. S. Levy (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 591–626.

27

Feldman S. Stenner K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Polit. Psychol.18, 741–770. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00077

28

Fella S. (2022). Italy: General Election and New Government. House of Commons Library Research Briefing 9629. London: House of Commons Library.

29

Fella S. (2024). France: Recent Political Developments and the 2024 National Assembly Elections. London: House of Commons Library.

30

Ford R. Goodwin M. J. (2014). Revolt on the Right: Explaining Support for the Radical Right in Britain. London: Routledge.

31

Funke M. Schularick M. Trebesch C. (2016). Going to extremes: politics after financial crises, 1870–2014. Eur. Econ. Rev.88, 227–260. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.03.006

32

Funke M. Schularick M. Trebesch C. (2023). Populist leaders and the economy. Am. Econ. Rev.113, 3249–3288. doi: 10.1257/aer.20202045

33

Galston W. A. (2018). The populist challenge to liberal democracy. J. Democr.29, 5–19. doi: 10.1353/jod.2018.0020

34

Golder M. (2003). Explaining variation in the success of extreme right parties in Western Europe. Comp. Polit. Stud.36, 432–466. doi: 10.1177/0010414003251176

35

Gurr T. R. (1970). Why Men Rebel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

36

Hawkins K. A. Riding S. Mudde C. (2012). “Measuring populist attitudes,” in Working Paper Series on Political Concepts. Colchester: ECPR Committee on Concepts and Methods.

37

House of Commons Library (2020). General Election 2019: Results and Analysis. House of Commons Briefing Paper 8749. London: House of Commons Library.

38

House of Commons Library (2024). General Election 2024: Results and Analysis. House of Commons Briefing Paper 10009. London: House of Commons Library.

39

Ivarsflaten E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comp. Polit. Stud.41, 3–23. doi: 10.1177/0010414006294168

40

Jackman R. W. Volpert K. (1996). Conditions favouring parties of the extreme right in Western Europe. Br. J. Polit. Sci.26, 501–521. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400007584

41

Johnson R. Pattie C. Allsop J. G. (1988). A Nation Dividing? The Electoral Map of Great Britain 1979-87. Harlow: Longman.

42

Johnson R. Pattie C. Dorling D. Rossiter D. (2001). From Votes to Seats. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

43

Katz R. S. Mair P. (1995). Changing models of party organization and party democracy: the emergence of the cartel party. Party Polit.1, 5–28. doi: 10.1177/1354068895001001001

44

Keating M. ed. (2020). The Oxford Handbook of Scottish Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

45

Kennedy P. (2008). A Guide to Econometrics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

46

Kouba K. Lysek J. (2018). What affects invalid voting? A review and meta-analysis. Gov. Oppos.54, 745–775. doi: 10.1017/gov.2018.33

47

Laclau E. (2005). On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

48

Local Government Association (2024). Economic Inactivity Interdependencies in England Report. London: LGA.

49

Mair P. (2013). Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy. London: Verso.

50

Majone G. (1996). Regulating Europe. London: Routledge.

51

Mian A. R. Sufi A. Trebbi F. (2014). Resolving debt overhang: political constraints in the aftermath of financial crises. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon.6, 1–28. doi: 10.1257/mac.6.2.1

52

Miller W. L. (1977). Electoral Dynamics in Britain Since 1918. London: Macmillan.

53

Mudde C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos.39, 541–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

54

Mudde C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

55

Mudde C. (2017). “Populism: an ideational approach,” in The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Eds. C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 27–47.

56

Mueller E. N. (1979). Aggressive Political Participation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

57

Murphy L. Thwaites G. (2023). Post-Pandemic Participation: Exploring Labour Force Participation in the UK, from the Covid-19 Pandemic to the Decade Ahead. London: Resolution Foundation.

58

Norris P. (2020). Measuring populism worldwide. Party Polit.26, 697–717. doi: 10.1177/1354068820927686

59

Oesch D. (2008). Explaining workers' support for right-wing populist parties in Western Europe: evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev.29, 349–373. doi: 10.1177/0192512107088390

60

Pilkington M. (2016). Loud and Proud: Passion and Politics in the English Defence League. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

61

Reform (2024). UK election manifesto ‘Our Contract with You'. Available online at: https://assets.nationbuilder.com/reformuk/pages/253/attachments/original/1718625371/Reform_UK_Our_Contract_with_You.pdf?1718625371(Accessed January 31, 2025).

62

Robinson W. S. (1950). Ecological correlations and the behaviour of individuals. Am. Sociol. Rev.15, 351–357. doi: 10.2307/2087176

63

Rooduijn M. Pirro A. L. P. Halikiopoulou D. Froio C. Van Kessel S. De Lange S. L. et al . (2024). The PopuList: a database of populist, far-left, and far-right parties using Expert-Informed Qualitative Comparative Classification (EiQCC). Br. J. Polit. Sci.54, 969–978. doi: 10.1017/S0007123423000431

64

Runciman W. G. (1966). Relative Deprivation and Social Justice. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

65

Schattschneider E. E. (1960). The Semisovereign People. Hinsdale, IL: The Dryden Press.

66

Scholes A. Curtice J. (2020). The Changing Role of Identity and Values in Scotland's Politics. London: National Centre for Social Research Report.

67

Stenner K. (2005). The Authoritarian Dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

68

Stokes D. E. (1963). Spatial models of party competition. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.57, 368–377. doi: 10.2307/1952828

69

Swank D. Betz H.-G. (2003). Globalization, the welfare state and right-wing populism in Western Europe. Socio Econ. Rev.1, 215–245. doi: 10.1093/soceco/1.2.215

70

Tajfel H. (1978). “The achievement of inter-group differentiation,” in Differentiation Between Social Groups, Ed. H. Tajfel (London: Academic Press) 77–100.

71

Weyland K. (2017). “Populism: a political-strategic approach,” in The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Eds. C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 48–72.

72

Whiteley P. Clarke H. D. Goodwin M. Stewart M. (2024). Brexit Britain: The Consequences of the Vote to Leave the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

73

Whiteley P. Clarke H. D. Sanders D. Stewart M. (2013). Affluence, Austerity and Electoral Change in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

74

Whiteley P. Seyd P. Billinghurst A. (2006). Third Force Politics: Liberal Democrats at the Grassroots. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Summary

Keywords

multivariate modeling, Reform party, general election 2024, constituency analysis, census data

Citation

Whiteley P (2026) The rise of the Reform party in Britain—Modeling Reform voting in the 2024 general election. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1614636. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1614636

Received

19 April 2025

Accepted

28 October 2025

Published

06 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

John Eaton, Florida Gateway College, United States

Reviewed by

Fred Paxton, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom

David Jeffery, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Whiteley.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paul Whiteley, whiteley@essex.ac.uk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.