- 1Jackson School of Global Affairs, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

- 2Department of Anthropology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

- 3Academie Diplomatique de Mauritanie, Nouakchott, Mauritania

- 4Department of English, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Introduction: A critical element of peacebuilding is engaging with how different groups understand pathways to peace, yet comparative insight across social groups remains limited. We conducted research with diverse stakeholder groups in Nouakchott, Mauritania — a socially diverse society negotiating peace within a conflict-affected region — to examine how people reason about pathways to everyday peace.

Methods and results: We used a participatory, systems mapping methodology (fuzzy cognitive mapping) to compare how people across diverse sectors of society see peace and think about pathways to everyday peace. Six focus groups included Mauritanian students, UNHCR-sponsored refugees, university professors, career diplomats, and townspeople (men and women). Each group of respondents defined everyday peace, then visually mapped key factors and perceived interconnections to describe local knowledge about pathways to peace. Three scenarios were run to visualize hypothetical interventions, modeling the relative importance of governance, socioeconomic, and community-level drivers. This study reveals important disconnects in how students, career professionals, and townspeople view pathways to everyday peace and what room exists to deliver system change.

Discussion: Mapping everyday peace reveals diverse forms of situated reasoning grounded in lived experience, social responsibility, and political agency. The study identifies not only how everyday peace is framed, but also how stakeholder groups evaluate room for change — what they consider actionable and where they see potential for meaningful intervention. The mapping analysis challenges assumptions of community consensus, highlighting critical blind spots and opportunities for dialogue across generations and social groups. It also offers a practical tool for civil society and state actors to clarify misalignments and develop strategies for inclusive peacebuilding efforts.

1 Introduction

The concepts of peace and peacebuilding can have different meanings for different groups of people. For this reason, knowledge representation across groups of stakeholders is important to map and understand, especially in contexts where peace is contested and difficult to sustain. Tensions often exist between local and international architectures of peace, which generates a need for dialogue between “local visions and diplomatic proposals for future solutions” (Lehrs et al., 2023). In this paper, we convened students, civil society, and state actors to document how people see peace and think about peace promotion across different generations and social groups of society. We conducted research in Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania, a city that presents an interesting case study for mapping knowledge about peace within a conflict-affected region. This study advances two aims. First, it shows how different social groups adopt distinct sociopolitical stances and forms of situated reasoning about peace, challenging assumptions of community consensus. Second, it demonstrates how a comparative, participatory mapping approach can operationalize the concept of everyday peace, offering insight into system change and identifying opportunities for peacebuilding dialogue.

Specifically, we asked six groups of stakeholders to proffer their thoughts and reach consensus regarding two questions: “What does everyday peace mean to you?” and “what are the drivers of everyday peace?” Our groups included Mauritanian students, UNHCR-sponsored refugees, university professors, career diplomats, and townspeople, both men and women. Asking the first question helped to elucidate what ‘everyday peace’ meant for people belonging to different sectors of society. Asking the second question helped to clarify how diverse groups of people thought about pathways to everyday peace, clarifying areas of agency, consensus, or significant disconnect, and highlighting entry-points for potential intervention. The central research question guiding our analysis was: what does comparison between stakeholder groups reveal about the subjective understanding of everyday peace and the local dynamics of peace promotion? The worldviews of people who live, learn, and work in Mauritania, while understudied, can inform empirical research on everyday peace and provide concrete suggestions to guide efforts on peace promotion.

We chose a participatory, visual, and scenario-generating approach to answer these questions. The ‘local-visual turn’ has been critical to recent shifts in peacebuilding research, emphasizing participatory and creative methods to visualize how people make sense of their social worlds. For example, visual methodologies have documented ongoing peacebuilding processes and social realities within local communities in Northern Ireland (Clark, 2024; Mac Ginty and Richmond, 2013), while photovoice projects have highlighted the ways ordinary citizens navigate and avoid spaces of conflict in Colombia (Fairey et al., 2023). The emphasis is placed on documenting the everyday knowledge of local actors, who navigate peace in conflict or post-conflict settings. Of note, innovative research has featured a hybrid combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches to reveal how people think about peace, examining what consensus exists, within local communities, about the drivers of conflict and the promotion of peace. For example, across multiple countries, research on Everyday Peace Indicators (EPI) have helped to measure the effectiveness of peacebuilding interventions from the perspectives of local actors (Firchow, 2018; Mac Ginty, 2021). The novel methodology we chose for this study — fuzzy cognitive mapping (FCM) — allows for the visual representation of local knowledge and modes of causal reasoning, helping to generate dialogue regarding how peace could be built or sustained. In this study, we describe how the concept of everyday peace encourages a close reading of how different groups of people see the world and map their social environments. Importantly, we show why a systems mapping approach is well suited to reveal how people see peace and think about peace promotion: it advances culturally-grounded research on everyday peace, engages diverse stakeholders, and encourages concrete problem-solving in peacebuilding approaches.

1.1 Everyday peace

As noted by Mac Ginty (2014, p. 550), “the term ‘everyday’ is beguilingly simple.” It captures the habitus of ordinary life in conflict or post-conflict settings, but rests upon largely invisible, muted practices and thinking about how people live in the world around them. Importantly, notions of everyday peace are often absent from peacebuilding discussions within diplomatic and policy circles. Everyday peace has been defined as a “series of actions and modes of thinking that people utilize to navigate through life in deeply divided and conflict-affected societies. [… It] is a way of seeing the world, or ‘reading’ a social environment, and of rationalizing a situation that might involve violence or the threat of violence. It relies on the deft use of a social infrastructure or a series of cultural, social, and economic networks that we use in our daily existence” (Mac Ginty, 2021, p. 9). In other words, research on ‘everyday peace’ allows for unpacking both social interactions and modes of reasoning — it highlights perspectives that valorize local identities, values, histories, and culture (Mac Ginty and Richmond, 2013). The concept of everyday peace has generated, empirically and theoretically, much interesting work on the meanings and forms of everyday peace practices in post-conflict societies.

Over the past decade, peacebuilding scholarship has undergone a local turn — an analytical shift that centers the everyday practices, relationships, and forms of knowledge through which people sustain coexistence beyond formal state institutions (Mac Ginty and Richmond, 2013; Autesserre, 2014; Firchow, 2018; Julian et al., 2019). This turn questions top-down models of peace and instead foregrounds how local actors understand and enact peace in their own settings. It provides an important conceptual backdrop for examining how peace is imagined and enacted in Mauritania, where multiple social worlds and governance traditions intersect. Boulding (2000, p. 4) wrote that “a culture of peace grows from the habits of everyday life — from the ways people learn to imagine and practice cooperation,” defining peace as a social learning process embedded in daily interaction. de Certeau (1984) similarly highlighted the knowledge and reasoning that emerge from ordinary practices of daily life. Building on these insights, Lederach (2005, p. 29) advanced an understanding of peacebuilding centered on what he called the moral imagination — the creative capacity to envision relationships that transcend current divisions and to perceive “the potential for something new to emerge.” His focus on imagining change links everyday reasoning to the possibility of transformation, offering an intellectual bridge between lived experience and systemic analysis. Together, these perspectives highlight peace as a form of situated knowledge — an understanding enacted through everyday experience and social interaction. This view underpins our systems mapping approach, which visualizes how diverse groups in Mauritania think about pathways to everyday peace.

Everyday peace can be “an important building block of peace formation” (Fairey et al., 2023, p. 1). This is because it focuses attention on people-oriented, rather than state-oriented, understandings of peace and peacebuilding. It provides an important counterweight to the ways that formal institutions and conflict resolution professionals approach peace accords, peacebuilding, and sustained peace. However, the real challenge is to connect different levels of analysis - namely, to effectively connect hyper-local realities of everyday peace with higher-level proposals for problem-solving in political and diplomatic spheres. On the one hand, this requires a systematic investigation of lived experiences and ways of reasoning at the individual and community level. On the other, it requires approaches to generate dialogue across groups of stakeholders, including those whose distinct views are often assumed or ignored, in ways that bridge potential disconnect. With respect to everyday peace, Firchow (2018, p. 156) reminded us to ask “whose knowledge counts?” when “threading the needle” between local, state, and international needs and priorities. A granular approach to understand local perspectives and the micro-dynamics of peace is useful to better understand how people make sense of the world around them (Brett et al., 2024). As such, developing methods that can map diverse knowledge systems is vital to reducing cultural bias in scientific inquiry, whilst developing methods that help understand the dynamic elements of a ‘peace ecosystem’ can improve analyses and problem-solving.

1.2 A systems mapping approach

In this study, we used a method known as Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping (FCM) to capture local knowledge in ways that rang true to local stakeholders. This is a participatory approach used to generate a ‘mental landscape’ — a ‘cognitive map’ — through group discussion, during which respondents identify a network of variables and their perceived interconnections (Tbaishat et al., 2025; Barbrook-Johnson and Penn, 2022; Gray et al., 2013; Panter-Brick et al., 2024; Sarmiento et al., 2020). It is a tool for collecting data on how people understand a complex issue, as well as a tool for making inferences from respondent-led data: we learn about the conceptual and dynamic characteristics of the map as a ‘knowledge system.’ Furthermore, it is a tool for learning and facilitating open discussion, within and across stakeholder groups: a series of maps, generated by different stakeholder groups, offer a transparent and systematic way to summarize information. This provides concrete and useful entry-points for dialogue across stakeholder groups: comparing maps generated by civil society or state actors can illuminate how different groups of people see the world around them (their belief systems) and think about the issues at hand (their understandings of potential system change). FCM is said to represent soft models of local knowledge, as well as simplified mathematical models to indicate causality and understand system dynamics (Sarmiento et al., 2020). It has been used to visualize how experts in peacebuilding policy, peace promotion, and peace education conceptualize system-level pathways to everyday peace, with a view to strengthening policy dialogue through participatory mapping (Panter-Brick et al., 2025).

Participants play an active role in generating their maps. First, they identify key variables and factors of influence. For example, to map pathways to peace, respondents might identify variables related to perceived safety (e.g., violence), governance (e.g., justice, corruption), socio-economic factors (e.g., inequality or poverty), and/or community values (e.g., tolerance). Second, they draw arrows to represent (perceived) causal relationships, both positive and negative, to link these variables together, visualizing the ‘system’ in real time. Third, respondents reflect on relative strength of impact, assigning values that range from −1 (strong negative influence) to +1 (strong positive influence) to each arrow on the map. Finally, respondents finalize their map, grouping variables that conceptually go together into color-coded categories, to give a legend to the map.

The power of this approach comes from facilitating comparison across different stakeholder groups, in order to better understand a complex issue and identify gaps in knowledge and experience, to improve learning and decision-making. The maps yield visual, qualitative, and semi-quantitative data of stakeholder knowledge (or mental landscapes) across respondent groups. They translate conceptual reasoning into semi-quantitative modeling, using the direction of specific arrows (perceived causality) linking variables in each map and their relative weights — a ‘fuzzy’ rather than exact quantitative measure of relative influence. This facilitates the development of ‘what if’ scenarios, comparing how different factors of interest will drive changes in the ‘ecosystem’ captured by each stakeholder map. For example, a hypothetical scenario might amplify the influence of ‘tolerance’ or diminish the influence of ‘corruption,’ if these factors featured prominently in representations of pathways to peace. The maps are the basis for exploratory scenarios run on respondent data, characterizing what respondents see as potential for system change.

In our research, we aimed to contrast the hands-on experience of different groups of people living, studying, and working in Mauritania. We convened Mauritanian students, UNHCR-sponsored refugees, university professors, career diplomats, and townspeople (men and women). Specifically, we wanted to capture the views of young people who were pursuing advanced education at university level — given that students likely invest time thinking about whether and how they intend to effect change in their personal and social lives. We also wanted to document the perspectives of a professional sector of society, namely university professors and career diplomats training the next generation of thought and peace leaders. Finally, we sought to capture the lived experiences of ordinary citizens, who raised families in Nouakchott, likely invested in thinking about the future. Empirically, we wanted to see whether these stakeholder groups spoke ‘the same language’ regarding everyday peace and approaches to peacebuilding.

1.3 Mauritania in context

Mauritania presents an interesting case study for mapping the pathways to everyday peace: it is characterized by socio-cultural diversity and peace promotion efforts within a conflict-affected region. Nouakchott is the administrative, cultural, and economic center of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, a nation that bridges the countries of the Maghreb with those of the Sahel. Situated at this crossroads, Mauritania has long felt the reverberations of regional instability — from recurrent insurgencies and trafficking routes in northern Mali and the wider Sahel to political turbulence across the Maghreb. These pressures have influenced domestic priorities around security, governance, immigration control, identity markers, and social cohesion, even as the country maintains an image of relative calm within a volatile region (Boukhars, 2016). Its population is composed of three main ethnicities: Bidhan or white Moors (Arabic-speaking nomadic communities of ethnic Arab and/or Berber descent), Haratin or black Moors (known as the descendants of enslaved Black Africans), and Afro-Mauritanians (primarily of the Wolof, Soninke and Halpulaar ethnic groups from coastal regions). While expressing great pride in their diversity, Mauritanians are sensitive to the ways cultural and ethnic diversity can be politicized to create division in their society (N’Diaye, 2010). Domestically, they have struggled to address ethnic and cultural grievances, which have pit Haratin and Afro-Mauritanian communities against the Bidhan community whose concentration of resources, power, and influence sustains social inequality. Violence between ethnic groups and a period of human rights violations from 1989 to 1992, referred to as the “passif humanitaire” [humanitarian liability], were followed with proposals for processes of truth and reconciliation (Amnesty International, 2023; MENA Rights Group, 2023; Sauriol, 2007).

Mauritania has experienced a fast rate of urbanization and pressures of migration. Because of its geographic location, Mauritania has become a gateway country for migrants, who flee conflict and poverty, en route to Europe (United Nations, 2023). It also hosts a growing refugee population (over 200,000 people in 2024; UNHCR, 2025), mainly from Mali. A resumption of regional conflict in 2012, and in 2023, led to more than 100,000 Malian refugees coming into Mauritania, many coming into the capital for education and employment. Recurrent war in neighboring Mali, the discovery of gas and oil reserves promising job opportunities, and the lure of prospects in Europe have made Nouakchott a magnet for migrants. Both forced displacement and economic migration, especially that of young people looking for sources of money (Craig, 2024), present distinct challenges for government institutions to address, as well as for communities to accommodate.

In this mosaic society, asserting a regional identity entails complex historical and cultural issues. Moreover, the influx of the refugees has heightened concerns regarding the infiltration of extremist groups and potential for a metastasis of instability in the region. To counter radicalization by outside groups, the Government has employed a series of measures relying on local imams to emphasize Mauritania’s Sufi Islamic tradition and engaging radicalized adherents in debates about Islam’s tenets. The policy of engagement and refutation of a culture of violence has enabled the Government to provide opportunity for formally radical Mauritanians to regain acceptance into local society. Philosophical, religious engagement on Islam combined with a robust military response to attempted incursions into its territory distinguish Mauritania as an outlier country of apparent stability, within a region plagued by instability, as seen in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso (N’Diaye, 2021).

Other threats to stability and security arise from the challenges of climate change and resource competition, which “threaten to disrupt the peace in the region” and “worsen the already fragile social fabric of the region” (United Nations, 2023). Tellingly, an informal cultural custom of cousinage or ethnic teasing, practiced primarily by Davidheiser (2006) and Dunning and Harrison (2010) has long been employed to diffuse everyday interpersonal tensions and to maintain a sense of commonality across social boundaries. Taken together, the legacies of ethno-racial hierarchy and competition, recurrent regional insecurity, and unequal access to economic opportunity form the backdrop to the social and political challenges of everyday peace. These conditions make coexistence an active, negotiated process rather than a stable condition, sustained through accommodation and dialogue. In brief, while Mauritania is considered to be at peace, it takes notable effort to sustain everyday peace.

2 Fieldwork and analysis

The study resulted from partnerships between the Diplomatic Academy of Mauritania, the University of Nouakchott, and the Jackson School of Global Affairs at Yale University. Previous collaboration took the form of practicum projects, involving students, professors, and career diplomats in the Sahel region. The study received ethics approval from the institutional review board of Yale University (Protocol 2,000,036,915).

2.1 Preparation and sampling

Research priorities and logistics were established through 2-h online team meetings prior to fieldwork. The research team co-constructed the research questions, discussed methodology, and established the sampling strategy. We aimed to conduct six FCM sessions (June 2024). Participants (n = 38) were recruited through WhatsApp messages sent by trusted local contacts. This platform helped to communicate research aims, basic demographic information, and respondent availability. Mauritanian students were recruited through the English Department of the University of Nouakchott. Refugees were contacted through a student-run organization that assisted UNHCR-sponsored refugees with scholarships for advanced study. Scholars were faculty teaching at the University of Nouakchott, while career diplomats were at the Diplomatic Academy. Townspeople were recruited through civil society organizations, who drew male and female respondents from different parts of the city, designating them as ordinary citizens and/or community members. The age, ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic composition of groups were not pre-determined during recruitment (except for community members, recruited into male and female groups). There were no financial incentives to participation. Our sampling strategy aimed to capture a range of social perspectives, following a qualitative and participatory approach appropriate for inductive mapping research. Given the small and purposive sample (38 participants across six stakeholder groups), the design sought diversity of reasoning across generational and socioeconomic urban groups, rather than numerical representativeness. The approach prioritized comparability, transparency, and reflexivity, with all procedures, facilitation steps, and analytical protocols documented to enable similar studies to be conducted in other settings.

Mapping sessions were led by one of two facilitators, chosen for their extensive experience leading group discussions and fluency in key languages. One (KD, female) was affiliated with the Diplomatic Academy, the other (YC, male) with the University of Nouakchott. Sessions were scheduled in the morning, afternoon, and evening, in order to suit work schedules, family obligations, and/or engagement in the presidential electoral campaign, which coincided with our period of fieldwork. Separate sessions were held for male and female community members, who often prefer to speak as groups of either men or women. By contrast, students, refugees, scholars and diplomats habitually interact in spaces that are not gender-segregated. Each session lasted between two and 3 h. At the start of each session, participants gave written informed consent, then detailed (anonymously) languages spoken at home, education, and conflict experiences. The facilitator invited respondents to introduce themselves (refugees, scholars and diplomats were acquainted through UNHCR or professional networks, while Mauritanian students and community members were meeting each other for the first time), before proceeding with sessions, which were audio-recorded. Two notetakers captured the verbatim conversation in Hassaniya (a variety of Maghrebi Arabic), French, and/or English, such that participants could speak in the language with which they were most comfortable, occasionally switching to Pulaar or Wolof, as needed. All mapping sessions were held in a medium-size room of the Diplomatic Academy, equipped with a laptop computer and a projector, where access to the internet would enable building a visual cognitive map in real time. We used the Mental Modeler software, a tool available online and free of charge, to facilitate map generation and analyses.

2.2 Map generation

Each session generated one cognitive map, generated by a group of respondents in four participatory steps (Table 1). In steps one and two, the facilitator asked respondents to explain their understanding of everyday peace and to identify key factors of influence (they built a visual map, consisting of key variables and interconnecting arrows). In steps three and four, participants assigned a relative weight to each and every arrow, to quantify strength of influence, and grouped together sets of variables to create the map’s legend. The facilitator’s role was to keep time, prompt open discussion, remind respondents to achieve consensus, and manage power imbalances and disagreement where these might arise. For example, during several group discussions, some respondents disagreed on how exactly the variables ‘justice’ and ‘tolerance’ were interconnected (with incoming or outcoming uni/bidirectional arrows), and/or the degree to which these variables influenced everyday peace, with values ranging from −1 (strongly negative) to +1 (strongly positive). They discussed whether ‘justice’ was the same concept as ‘social justice,’ or ‘war’ the same concept as ‘violence’ or ‘genocide.’ They also debated how to group variables together, in a coherent way, with different colors assigned to those variables that, from their perspectives, conceptually went together. When this happened, the facilitator would remind respondents that they could name and rename variables, redraw arrows, assign new weights, and regroup variables, as an iterative process to building their ‘mental map.’ Each session was followed by short interviews with individual participants, invited to reflect on the value of the methodology. Each day ended with debrief sessions with the research team.

2.3 Map analyses

Following the fieldwork, we conducted analyses through online videoconferencing, to allow for an extensive discussion of maps, scenarios, and findings. We followed three analytical steps: thematic analysis, graph analysis, and scenario analysis (Table 1). In step one, team members reviewed the recordings and verbatim transcripts transcribed into both English and French. We discussed the examples and conceptual categorizations proffered by respondents during FCM discussion, noting areas of emphasis, disagreement, and consensus. In step two and three, we used the visual mapping interface of Mental Modeler to examine all variables and their interconnecting arrows. We then used the quantitative interface of Mental Modeler to understand the structural properties of each map and to create scenarios.

We focused attention on map dynamics: we identified driver variables and strength of perceived influence (represented by the quantitative values generated by the program) and we ran simulations to show how the system responded to amplifying factors of interest. Specifically, in step two, we counted all interconnecting arrows, examined their relative weights (positive or negative values), and categorized driver variables into distinct domains to enable comparison across groups of respondents. In step three, we amplified the relative influence of specific variables to predict impacts on everyday peace. We ran exploratory scenarios on each map, then compared the six maps in terms of how stakeholder groups perceived the pathways to everyday peace. These scenarios can be interpreted as simplified simulations of possible policy or programmatic interventions. For this analysis, we were guided by the ways respondents had discussed key variables, and by the structural properties of each map. Two researchers independently categorized all driver variables into five domains (governance, society and economy, community, wellbeing, and safety), before consensus about the categorization was reached with the research team. In scenario analysis, we activated (amplified) driver variables within a given domain (e.g., governance), to illustrate their relative influence on everyday peace and/or system change (from no change, to strong change).

Finally, we re-drew the Mental Modeler digital maps using the Gephi software: this allowed us to feature variables according to their relative importance (centrality), as circles of different sizes (reflecting the number of incoming and outgoing arrows). We also re-drew the results generated by the Mental Modeler program’s algebra calculations for specific scenarios, using Canva: the bar graphs visualized predicted impacts on key outcomes. This allowed us to focus on inter-group comparison.

3 Results

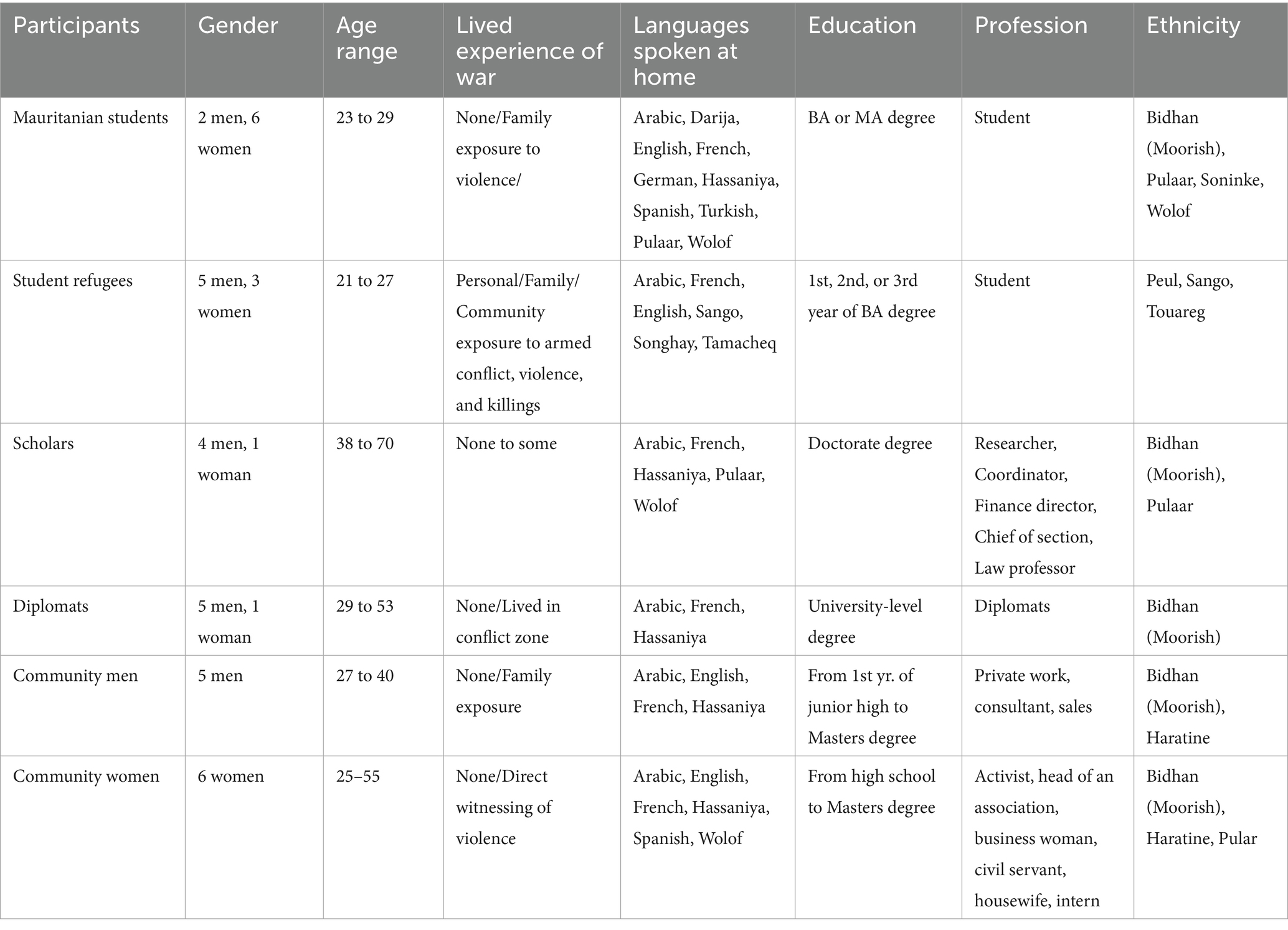

The six groups of respondents are shown in Table 2. While these groups do not capture statistically representative segments of the Mauritanian population, they do characterize a broad mosaic of society. Our respondents were linguistically very diverse. For example, Mauritanian students (group 1) spoke English, French, German, Hassaniya, Turkish, and/or Wolof, while community men and women (groups 5 and 6) spoke Arabic, Hassaniya, English, French, Wolof, and/or sign language. Indeed, it was only when the respondents introduced themselves, to each other, that a decision was made to have the group converse in either English (for Mauritanian students), French and Hassaniya (for refugees and scholars), or French, Hassaniya and Pulaar (for community men and women). With respect to education and social class, the students and professionals were fairly homogeneous groups, while ordinary citizens were more diverse: community men engaged in private work as cleaners, commerce, and/or research, with an education level that ranged from the first year of high school to graduate school, and community women described themselves as business people, civil activists, civil servants, interns, and/or housewives, with high school or graduate school degrees.

With respect to lived experience of conflict, this ranged from none to familial and/or personal war exposures. For example, in group 1, one student “listened to many stories from [his] uncle who was a fighter in the Saharan war.” A second stated that one of his uncles experienced the armed conflict between Mauritania and Senegal in the 1990’s, “having to flee because of that turmoil.” A third said his grandparents experienced conflict, in the 90s, “when the community people were exposed to the injustice acts of the colonizers.” In group 6, one woman stated she directly witnessed the “Sahara war and two other attacks,” while another said she lost contact with her husband when he was caught in the 1992 Angola conflict. For their part, refugees (group 2) disclosed many acts of violence: they cited attacks in northern Mali in 2012, family and community-level experiences of “political, military, ethnic, and religious conflicts,” parents being “massacred by Wagner mercenaries” in northern Mali, family members being killed, gravely injured, or imprisoned, and forced displacement. Seven respondents were from Mali, one from the Central African Republic. This diversity, within and across groups, was helpful to group discussion: respondents were inclined to explain their point of view, and discuss their differences, before reaching consensus about pathways to everyday peace.

3.1 How groups of respondents see everyday peace

The phrasing of our first question - “what does everyday peace mean to you” — was easily understood across respondent groups. When phrased in French, respondents referred to “la paix quotidienne” [daily peace] or “la paix de jour en jour” [peace, from day to day]. In Hassaniya, the phrase was rephrased as: “el amen, youm we youm we youm baad youm” [peace, day by day and day after day]. Verbatim statements from respondents are exemplified in Table 3. For Mauritanian students, everyday peace was a “state of quiet and coexistence,” calm enough to sit at home “reading a book.” For refugees, it was not just a state “of calm and tranquility,” but an environment of safety, justice, and rights where one could “circulate without fear” and carry out one’s everyday tasks, like shopping for food. For their part, scholars echoed the importance of being able to carry out simple, “ordinary activities” such as hold classes and visit a neighbor, with a freedom of choice and the ability to pursue one’s hopes. More pointedly, they spoke of the “chimera” of peace, which would remain a mirage if “stability” were not at its core. Diplomats drew attention to border issues, where feelings of insecurity were heightened: “as a person coming from the border, peace is key to survival. If you do not feel safe, you cannot go to work, you can lose your property at any time.” Given the significance of commerce and social transactions, they quickly went on to mention: “if you do not have a justice system, and you have an issue, then you are not sure you will get a fair trial, you cannot have a feeling of peace. To have this feeling of peace, you will need to feel that you can be heard.”

Table 3. Examples of respondents’ definitions of everyday peace, in answer to the prompt “what does everyday peace mean to you?.”

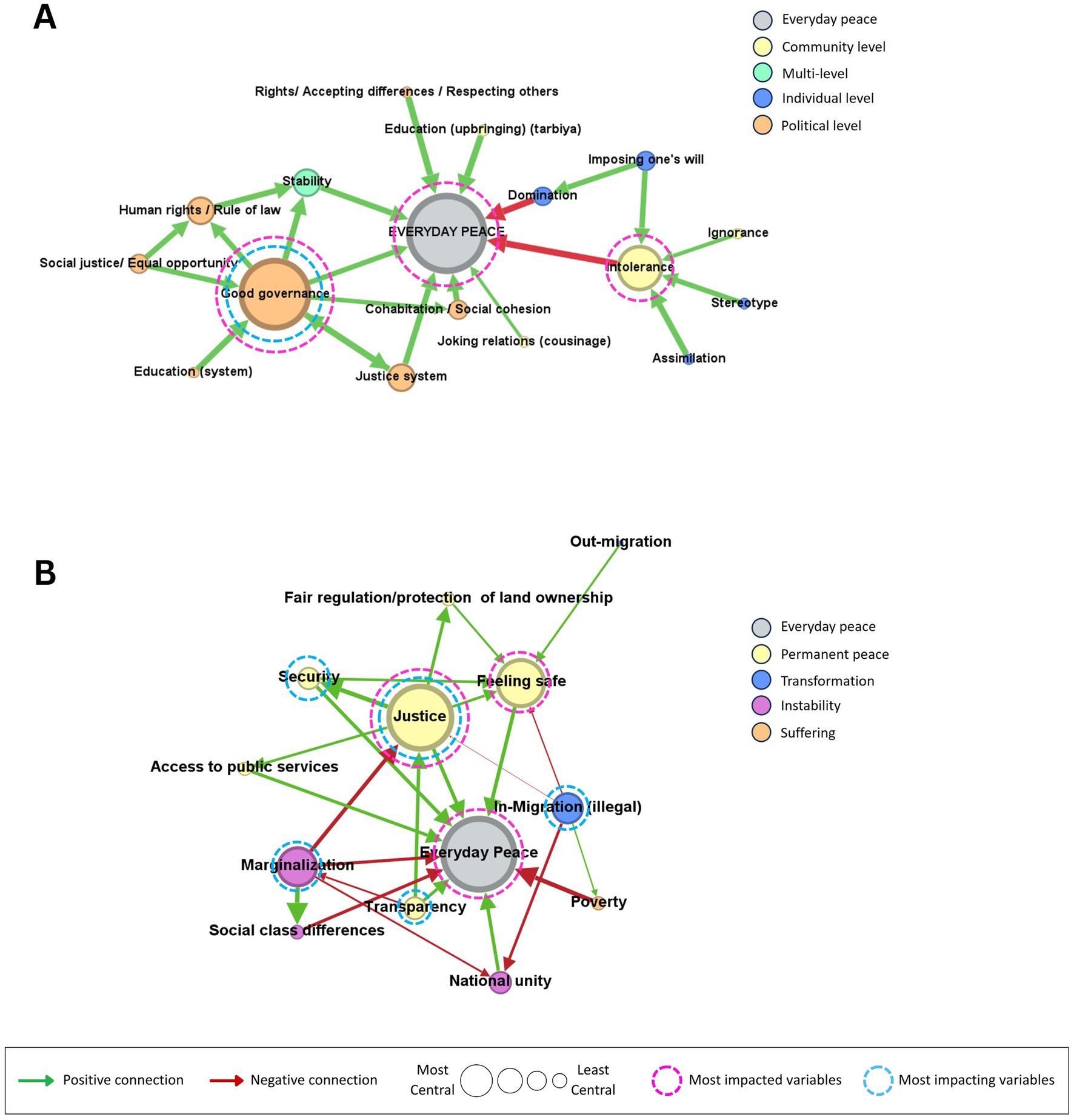

Our second question — “what are the drivers of everyday peace” — prompted open discussion, in which respondents considered and, through consensus, identified the factors that increased or decreased their everyday peace. The cognitive maps are ‘mental landscapes’ drawn by groups of respondents. They show how respondents saw everyday peace in terms of factors and perceived causal connections. They also show which are the most impacted (receiver) variables (with the most incoming connections), as well as which are the most impactful (driver) variables (with the most outgoing connections). We discuss each map in turn (Figures 1–3).

Figure 1. (A) Mauritanian students generated two main clusters (everyday peace; any form of violence) in their map. (B) Refugee students also visualized two clusters (everyday peace; forms of violence related to war and genocide).

Figure 2. (A) Scholars visualized a push-pull dynamic between three main variables: everyday peace, good governance, and intolerance. (B) Diplomats identified as many as six main clusters, including everyday peace, justice, and feeling safe.

Figure 3. (A) Community men identified variables that reflected family-level concerns (everyday peace, family peace, and a secure income). (B) In their map, community women balanced the negative and positive factors influencing everyday peace.

3.2 Maps drawn by Mauritanian and refugee students

Mauritanian students identified two main clusters (everyday peace and violence) and four main driver variables (system corruption, economic stability, ignorance, and insecurity; Figure 1). They described issues in Mauritanian society that would impact their lives and future, categorizing them as instability, economic status, peace, and self-fulfillment (see legend). For example, system corruption was the root of instability in society, together with insecurity, poverty, violence (in any form), injustice, conflict, misunderstanding, and dominance/misuse of power. Ignorance and education were distinct concepts, related to ‘self-fulfillment’ — the former referred to a societal mindset and upbringing, the latter to features of formal educational systems. Economic stability was key to health and prosperity, hence everyday peace.

Refugee students also generated a map with two main clusters: everyday peace and war/genocide (Figure 1). However, the content and tone of their group discussion were quite different. Refugees began the session, without hesitation, by naming variables that were negatively impacting everyday peace. They spent time discussing whether war, conflict and genocide were fundamentally distinct categories, or forms of violence that could be lumped together for the purposes of the mapping exercise. Only further into their discussion did participants list factors with a positive influence on everyday peace, such as equality. Their map showed perceived direct links between colonization, democracy, and everyday peace; direct links between climate change, economic development, good governance, and everyday peace; and direct links between racism, religious extremism, and ignorance on the one hand, and war/genocide on the other. Given their lived experience of conflict and forced displacement, student refugees honed in on issues of personal security, conveying the intimate connections between peace and safety, stating “peace for me is being able to move about without fear.” They paid attention to threats to personal security, including banditry, ignorance, vengeance, religious extremism, racism and violence, all of which were mapped through group consensus. Conversely, they identified factors that enabled flourishing, such as solidarity, cultural diversity, citizenship/patriotism, discipline, and justice. These concepts mattered to them profoundly, a compass to life in the present and in the future.

3.3 Maps drawn by scholars and diplomats

For scholars, three main variables dominated the map: everyday peace, good governance, and intolerance (Figure 2). Visually, these clusters represent a push-and-pull dynamic between governance on the one hand and intolerance on the other, with everyday peace being impacted by both. Good governance was manifested through respect for human rights/rule of law, the pursuit of social justice/equal opportunity, the quality of the education system, and the justice system. Intolerance was a collective mindset, which in Mauritanian society, was engendered by ignorance, stereotype, assimilation, and imposing one’s will (through individual-level behaviors, community practices, and/or one-sided government policies). This group fiercely debated the concepts included in the map, often adopting a philosophical and theoretical stance. For example, after some contestation, respondents came to a consensus regarding the (positive) relationships between assimilation, intolerance, and ignorance. The more (enforced) assimilation in society, the more intolerance, because assimilation implied a disregard for difference and/or cultural diversity. One participant exclaimed: “le colonisateur n’était pas ignorant” - the colonizer was never ignorant, when pursuing a policy of cultural assimilation. When mapping everyday peace, scholars were thus engaged in debating the histories of colonization, the politics of assimilation, and the benefits and challenges of living in a highly diverse society.

Diplomats identified as many as six main clusters in their map (Figure 2). Justice, everyday peace, and feeling safe loomed large in this ecosystem. Justice was notably impactful (with direct outgoing arrows to everyday peace, security, feeling safe, having access to public services, and fair regulation or protection of land), yet also impacted by marginalization (in the sense of limited opportunities engendered by nepotism), as shown by an incoming arrow. In-migration, marginalization, and transparency were three important driver variables. Of all the groups, diplomats were the ones who drew the most connections between variables. Immersed in current affairs and policy issues, they articulated historical and governance arguments about Mauritania’s experience with illegal in-migration from neighboring countries, with the increase of youth out-migration, and with perceived insecurity in society. For them, a sense of national justice and safety was fundamental to the conceptualization of everyday peace. Justice meant the fair distribution of resources, predicated on equality or equity of resources: “a fair redistribution of resources is needed in society.” Justice was linked to politics and the sense of everyone being treated fairly. For example, within the administrative sector, to see justice was to get a job according to one’s qualifications, rather than social connections. A robust justice system could engender a sense of security (at the national level) and a sense of safety (at a personal level). Respondents emphasized that “there is insecurity when there is no agreement across regions of the country.” In their view, younger generations would leave Mauritania because of the risk of violence, as well as the promise of financial gain.

Respondents went on to discuss systemic factors such as ‘national unity’ as an important factor for peace: “in this country, some use ethnic diversity as a way to create conflict between groups, to project the issue of ethnic conflict. If you do not have national unity, or a system of coherence, then you cannot have a feeling of peace.” Because Mauritania was a land rich in resources, participants asserted that there could be prosperity among local people, a consensus about land rights and distribution, and a way for locals to exchange and do commerce among communities that would guarantee peace. They noted, however, that, in recent years, agribusinesses, benefiting from big machinery and government backing, had swooped in to buy local land, rendering much of the local population landless. Ethnic and cultural bonds to the land, which had endured for generations, were broken: “The government was in a hurry to do development without paying proper attention to the mosaic of society.” What was needed was transparency, by which respondents meant “the information about public wealth,” referring to fiscal transparency reports released by the government.

3.4 Maps drawn by community members

Townspeople, men and women from the community, were our last comparison group. Their maps reflected a more intimate expression of lived experience. Men largely talked about the kind of peace that affected the family-level environment, revealing a preoccupation with the burden of shouldering family obligations. Their map featured three main variables (everyday peace, family peace, and secure income; Figure 3). They were aware of the challenges of unemployment and “obstacles” that one could not control, as well as the benefits of having income, good health and an appropriate environment. Men were concerned with building the father as a role model to the family, which was challenging where there were spousal differences in socioeconomic standing, education, and/or expectations. For example, one father stated that when his wife made new demands for housing and material goods, this broke the peace, as he, as a provider, would have to say no, given his limited income. Another respondent argued that he was “man enough” to provide what he could for his wife, who also had the right to ask for more even if he could not afford it. In terms of gender dynamics, her demands did not, in his eyes, diminish his own sense of worth. That same respondent, however, expressed deep frustration about his inability to control a child with anger issues. ‘Building the father as a role model’ was thus a key concern: this phrase reflected the gendered nature of family-level tensions, as men were anxious to assure an appropriate environment for the family, show compassion to children who were hard to control, and to build the next generation’s future. Undoubtedly, for these fathers, the center of gravity for sustaining everyday peace was to sustain family peace and a secure income.

Women’s sense of everyday peace was expressed in terms of life, unease, and wellbeing (see legend, Figure 3). They drew five negative arrows, and five positive arrows, to balance the cluster representing everyday peace. Most strikingly, they identified six main driver variables: violence, social inequality, financial dependence, poverty, ignorance, and tolerance (all categorized as “unease”). They stated that financial dependence restricted one’s ability to make choices - it “made a person a slave to other people’s will” - and was at the root of social inequality, as well as a threat to peace. They ascribed “ignorance” to a lack of good upbringing (“tarbiya”), saw “cohabitation” as key to wellbeing in the community, and thought peace meant the acceptance of differences in upbringing, customs and behaviors. In their words, “la paix c’est accepter les differences, de religion, de langue, de comportement” [peace is the acceptance of differences, of religion, language, and behavior]. Women frequently alluded to the idea of an “other” in society, urging that differences be accepted and declaring that “the real Mauritania is peaceful.” They invoked faith-related notions of “love for one’s neighbor,” forgiveness, and concession – everyday practices that were generative of life. Indeed, women infused their description of everyday peace with religious terminology, citing a hadith (quoted in Table 3) to emphasize that “good health, security, and financial independence” is the basis for everything. Their discussions captured a sense of a journey through life, rooted in values such as love, forgiveness, tolerance, and mutual respect, and reflected the prominence of religious principles in the lives of many Mauritanian women.

3.5 Key insights

Our analysis reveals the different ways in which groups of respondents were ‘seeing’ everyday peace. Each group articulated a consensual interpretation of everyday peace and a subjective causal logic when ‘thinking’ about inter-connections. This offers noteworthy insights. In their definitions of everyday peace, respondent groups offered many overlapping views: their priorities touched upon peace of mind (“a state of calm”), security and stability, co-existence in a mosaic society (“accepting differences”), and freedom of choice and expression (“the ability to pursue one’s desires” and to “freely express my conscience”). In thinking about peace promotion, however, the six groups prioritized different pathways: from their standpoint, some cause-and-effect relationships were far more tangible than others. Because of this, they built their maps differently.

In maps drawn by students and refugees, peace and violence are featured prominently — as binary opposites. However, the pathways to everyday peace (as shown by inter-connections) are differently perceived. The students’ map is largely conceptual: students applied a critical, problem-solving approach to tackle issues of governance (e.g., system corruption), economic stability (including prosperity and poverty), and collective mindset (e.g., ignorance). The fact that their map has four main driver variables means that, from their standpoint, there are four points of interventions (system corruption, economic stability, ignorance, and insecurity) likely to generate potential change relevant to peace promotion. By contrast, the map drawn by refugees speaks volumes to the lived experience of violence (including war, conflict, and genocide) and poverty, categorized together as “evils.” Their map has three main drivers, identified as war/genocide, poverty, and equality. From the standpoint of respondents who experienced the challenges of forced displacement and resettlement, these variables were likely to generate the most room for system change, for better or for worse.

In maps drawn by scholars and diplomats, we see everyday peace as intimately tied to governance and/or justice. Scholars vigorously debated both political governance and social intolerance, being preoccupied with colonial legacies and present-day challenges of achieving social cohesion within a very diverse society. For them, pathways to peace hinged on amplifying good governance. They spoke from the perspective of a privileged elite and a generation which had seen much turbulence and transformation in Mauritanian society. For the diplomats, the peace ecosystem was even more complex. The three main drivers of potential change reflected the present-day concerns with (illegal) in-migration, social marginalization, and threats to transparency, all of which threatened social cohesion and everyday peace (as well as viable employment opportunities). The diplomats essentially catalogued issues commonly seen as threats to peace in conflict-torn countries. They did, however, give voice to a range of grievances expressed by the younger generation of Mauritanians, who have felt stymied by limited job opportunities, connecting unfair resource distribution to the government’s responsibility for ensuring justice.

In maps drawn by ordinary citizens, we do not see a preoccupation with governance or institutions related to justice or education. Rather, we see that everyday peace is a matter of balancing external demands (e.g., for financial security or independence) with internal wellbeing (living with family and one’s neighbors). In stark contrast to scholars and diplomats, seen to hold professional expertise about local society and regional conflicts, “ordinary citizens” (a term used by Mauritanian respondents) saw the dynamics of peace in terms of lived experiences of community, family, and everyday wellbeing. Specifically, men featured a variable called “family peace” in their consensual map, while women explicitly invoked expressions of ignorance and tolerance, of violence and love, driving everyday peace in community. While there was conceptual overlap with other maps – in terms of variables such as ignorance, poverty, safety, and violence – the maps from community members reflected their proximate, day-to-day concerns. They also reflected the gender roles assumed within family and society, with women taking active responsibility for upholding the codes of behavior and the tenets of Islamic life.

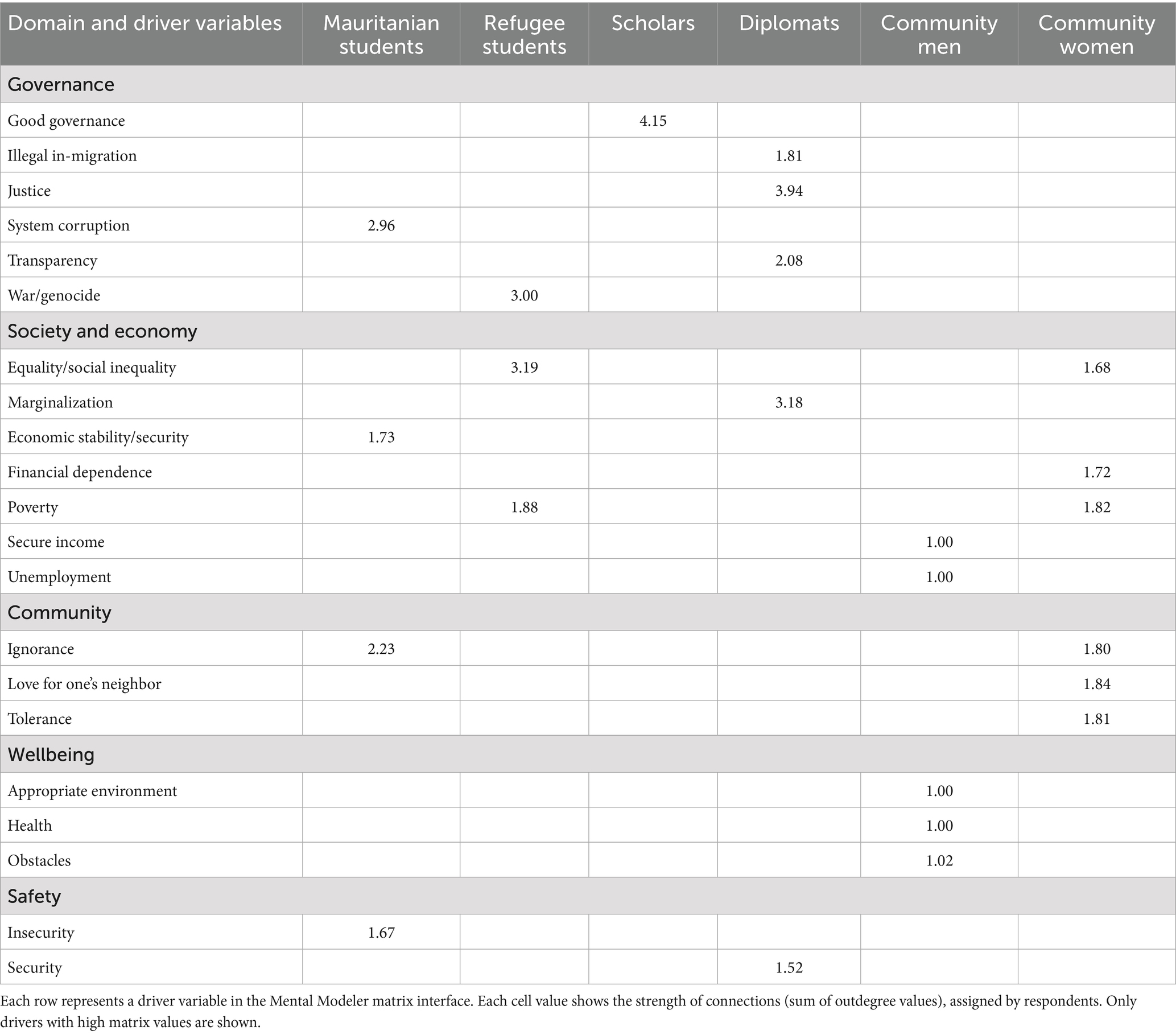

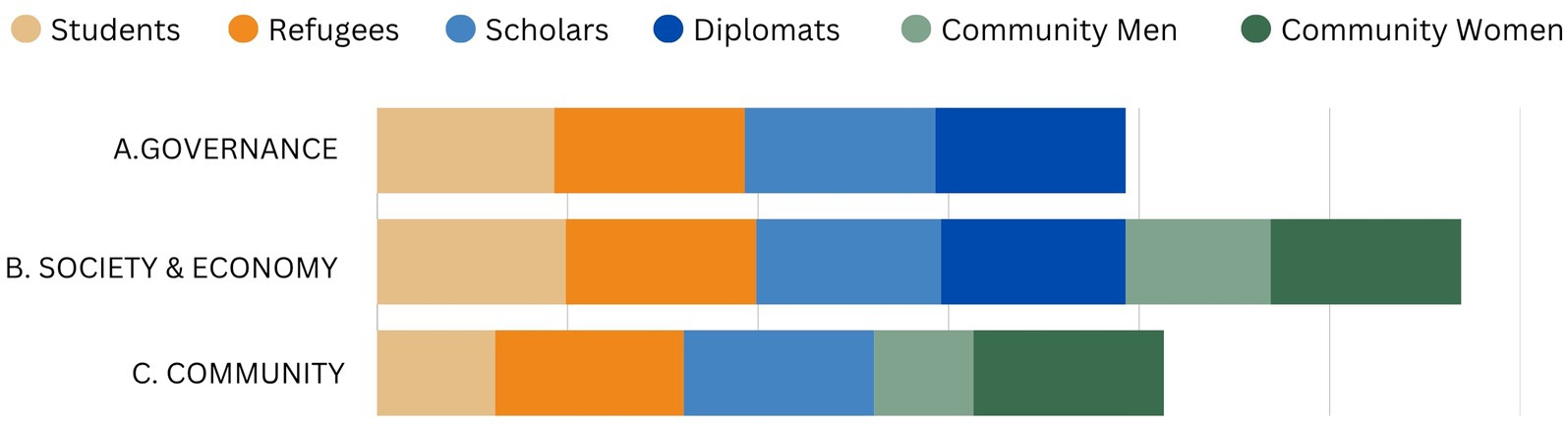

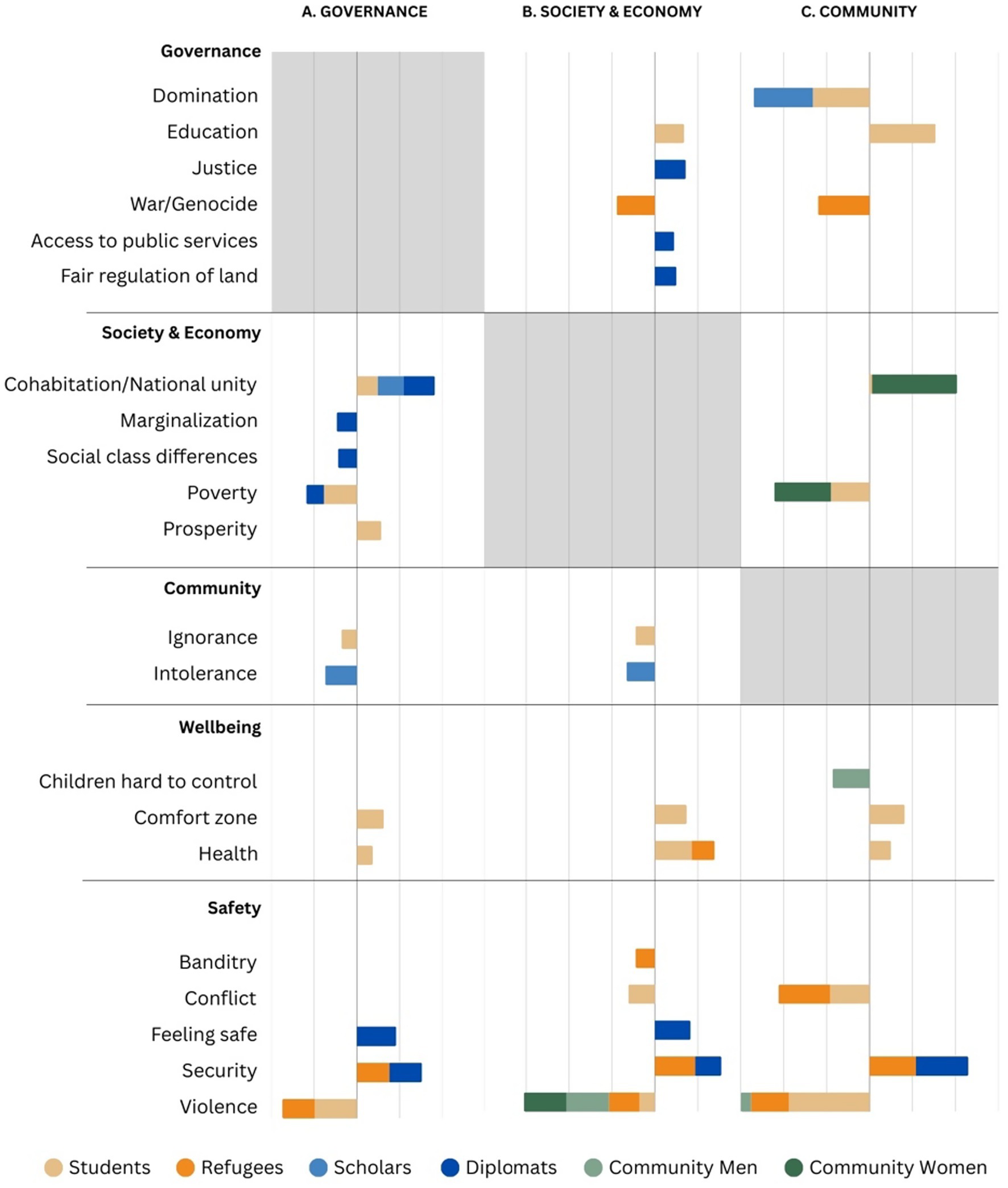

The maps thus reflect how different stakeholder groups positioned themselves visa vis the peace ecosystem. To facilitate inter-group comparison, we displayed our data on the number of driver variables across several domains of thematic interest (Figure 4, Table 3, step 2). For analytical purposes, we focused on five broad domains: (i) governance; (ii) society & economy; (iii) community; (iv) wellbeing; and (v) safety. Governance, for example, included the following variables: colonization, corruption, democracy, dominance/misuse of power, the education system, forced assimilation, the justice system, public services, regulation of land, regulation of migration, respect for human rights, social justice, transparency, and the waging of war/genocide. Figure 4 thus shows the alignment and/or divergence in stakeholder knowledge, with respect to how many variables were identified in each domain. We see that Mauritanian students, refugee students, scholars, and diplomats readily perceived the importance of governance-related factors, as directly connected to everyday peace. In stark contrast, community men and women did not.

Figure 4. Dimension analysis of the factors connected to everyday peace. Each chart plots the number of factors identified by stakeholders in domains of governance, society and economy, community, wellbeing, and safety (larger radial values indicate a higher number of factors identified in group discussion). The charts illustrate alignment and divergence in stakeholder knowledge. For example, Mauritanian students, refugee students, scholars, and diplomats differ from community men and women in perceiving the salience of governance factors as directly connected to everyday peace.

For their part, the community men’s group focused attention on the domain characterizing wellbeing: building the father as a role model, controlling children, enabling comfort zones, addressing family needs, ensuring family peace, overcoming obstacles, resolving spousal differences, building an appropriate environment, and sustaining health. The women, in turn, were most attentive to balancing community values with societal drivers of everyday peace. In placing strong emphasis on community values, the women aligned themselves with the group of scholars: the values guiding community behaviors included compassion, concession, education as upbringing (“tarbiya”), forgiveness, ignorance, imposing will over others, intolerance, love for one’s neighbor, misunderstanding, selfishness, tolerance/respect, acceptance of difference/rights, and vengeance. In placing strong emphasis on societal drivers — a slew of variables related to cultural diversity, cohabitation, financial stability, and marginalization, community women aligned themselves with students and refugees. These broad prioritizations likely reflected how stakeholder groups envisioned their agency, within a complex ecosystem, and what they perceived would matter, for bolstering everyday peace.

3.6 How groups of respondents think about peace promotion

We now move to scenario analysis (Table 1, step 3). For this, we consider quantitative measures of influence, to better understand how groups of respondents saw potential system change, and thereby, potential spaces of intervention. The Mental Modeler software generates a matrix which defines actual system dynamics: it lists all the variables included in a specific map and translates their interconnections into quantitative values (between +1 and −1). Each cell value then represents the fuzzy approximation of influence that bound the matrix and its components together. We noted that there was no single driver variable (e.g., justice, inequality, tolerance) that was shared across all six groups. This meant that we could not focus on a single variable, in scenario modeling, to examine potential impact across all respondent groups. For comparative analysis, we focused on modeling system change within broader domains (governance, society & economy, community, wellbeing, and/or safety).

3.7 Spaces of intervention

We turn attention to the most consequential drivers — shown in Table 4. Each row represents a driver variable, with the cell value calculated in the matrix interface of Mental Modeler. Whereas Figure 4 plots the number of all factors identified by respondents when building their map, Table 4 lists only those drivers likely to be consequential for change, given the strength attributed to all interconnections (a high matrix value). For example, Mauritanian students, refugees, and scholars identified just one variable consequential for systemic change: system corruption (value = 2.96), war/genocide (value = 3.00), and good governance (value = 4.15), respectively. Other governance factors listed in their map did not have matrix values high enough to power change in scenario simulation. For their part, diplomats identified five strong drivers of change: illegal in-migration (value = 1.81), justice (value 3.94), transparency (value = 2.08), marginalization (value = 3.18), and security (value = 1.52). Community men and women saw none.

Table 4. The most impactful factors impacting everyday peace, as mapped by six groups of respondents.

3.8 Hypothetical scenarios

We then ran ‘what if’ scenarios: using the Mental Modeler interface, we activated (amplified or diminished) select variables, maximizing their positive influence (+1) or decreasing their negative influence (−1), to visualize quantitative effects. We demonstrated these scenarios, albeit briefly, to groups of respondents. For example, with diplomats, we demonstrated the relative impact of hypothetically ‘decreasing’ social marginalization (assigning a matrix value of −1), showing how changes rippled through the system, improving everyday peace, justice, and national unity, as well as decreasing social class differences, and affecting connections thereon. The online program visualizes such outcomes (predicted impacts) as bar charts that quantify the relative change in the map’s components, under a chosen scenario. This helps develop an understanding of system change — the extent to which changes in the relative influence of one or several variables affect all other variables in the map.

We chose three scenarios for comparative analysis. In scenario A, we activated the governance factors only; in scenario B, we activated socioeconomic factors only; and in scenario C, we activated community factors only. We did not model the influence of wellbeing factors, since only one group of respondents (community men) perceived them as consequential (Table 4), nor did we model the influence of safety factors, to avoid presenting tautological findings (decreasing feelings of insecurity would increase everyday peace).

Figure 5 shows predicted impacts on everyday peace, the main variable of interest. The horizontal bars quantify the positive change anticipated under a specific scenario (A, B, or C). Results are broadly similar for three of the six groups: as perceived by students, refugees, and scholars, amplifying (A) governance, (B) society and economy, and (C) community factors will foster everyday peace, given the interconnections drawn in their cognitive maps. For the diplomats, however, there are no perceived impacts of community-level factors on everyday peace, while for community men and women, there are no perceived impacts of governance factors on everyday peace (the interconnections were absent or weak in influence). This confirms an important result: diplomats do not think about influential spaces of intervention at the level of community factors, whilst community members do not see that changes in governance will likely impact everyday peace.

Figure 5. Scenarios predicting impacts on everyday peace. Each bar represents the predicted change in everyday peace, under a chosen scenario. Based on the map dynamics identified by stakeholder groups, the three scenarios activate (A) governance, (B) society and economy, or (C) community-level factors. Activating variables, using the Mental Modeler program, denotes amplifying their strength to maximum value (−1 or +1). For example, the perspectives of Mauritanian students, refugee students, and scholars were well-aligned. However, diplomats did not prioritize community-level factors, nor did community men and women prioritize governance factors, as drivers of everyday peace.

Figure 6 shows predicted impacts on other variables in the peace ecosystem. This allows us to compare what room exists for potential system change, as seen by different stakeholder groups: the horizontal bars show the extent to which variables are impacted through scenarios A, B, or C. Diplomats saw that improved governance (scenario A) would strengthen national unity, reduce marginalization, poverty, and social class differences, reduce intolerance, and improve feelings of safety and security. They also anticipated that improving socioeconomic factors (scenario B) would strengthen the justice system, access to public services, and fair regulation of land, in addition to boosting stability and feelings of safety. Scholars predicted fewer impacts, limited to cohabitation, domination, and intolerance, while Mauritanian students anticipated many notable improvements across governance, socioeconomic, community, wellbeing, and safety domains. Refugee students, thought that all three scenarios would improve security and reduce violence, and that improving socioeconomic factors would reduce banditry, make war/genocide less likely, and improve health. Lastly, community women viewed system change in terms of impacts on cohabitation, poverty, and violence, being most attentive to issues of community, safety and wellbeing. For their part, community men discerned very few pathways for system change.

Figure 6. Scenarios predicting systemic impacts. Each bar represents the predicted change in variables in the peace ecosystem, under a chosen scenario. Based on the map dynamics identified by stakeholder groups, the three scenarios activate (A) governance, (B) society and economy, or (C) community-level factors. Each scenario is run for one domain (shaded in grey) at a time. Activating variables, using the Mental Modeler program, denotes amplifying their strength to maximum value (−1 or +1). The scenarios help develop an understanding of system change, with pathways to peace mapped through different variables.

Taken together, these scenarios illustrate how groups differed not only in what they viewed as drivers of peace, but in how they conceived of change itself. The simulations reveal contrasting orientations toward system change: actors positioned closer to formal institutions associated peace with structural reform and governance coherence, while others, grounded in everyday social life, emphasized shifts in social values and relationships. Mapping these hypothetical policy options helps to visualize where different groups expect leverage for improvement — and where dialogue is needed to connect institutional reform with the social reasoning that sustains peace in daily life.

4 Discussion

This paper adopted a system mapping approach to analyze how different groups within Mauritanian society see everyday peace and think about peace promotion. Our analysis reveals how different social actors conceptualize peace, locate responsibility, and imagine change. This section revisits our central research question: what does comparison between stakeholder groups reveal about the subjective understanding of everyday peace and the local dynamics of peace promotion? Our discussion makes two core arguments. First, we capture expressions of everyday peace as situated reasoning, within a plurality of respondent stances, challenging an elusive search for community consensus. Second, we underscore the value of comparative, participatory analysis to identify blind spots in dominant peacebuilding narratives — and to support more inclusive dialogue across state and civil society.

4.1 Everyday peace as situated reasoning

This study reveals that our respondent groups adopted distinct sociopolitical stances — rooted in how they positioned themselves in relation to social order and political power. Each map was a visual representation of their stance, allowing for the expression of situated reasoning: each reflects the participants’ own ways of making sense of peace and social order, grounded in their ordinary logic rather than formal systems of thought. The scenario analysis extended this comparison, showing how groups not only understood peace differently but anticipated different leverage points for change — from structural reform to social repair. As argued by Mac Ginty (2021, pp. 221–2), “everyday peace often takes the form of a mode of thinking as well as manifesting itself in actions or speech acts. It often takes the form of a stance, or the orientation of the individual or groups of individuals.” The notion of a stance, he reflected, has been underexplored in peace and conflict studies. The value of these maps lies in the fact that local stakeholder knowledge on everyday peace — the stance and the ordinary logic of a group of people - is often difficult to see.

As this study shows, respondents framed the peace ecosystem in different but interconnected ways. Everyday peace was a layered concept, understood as peace of mind, safety, co-existence, tolerance, justice, and transparency. In essence, the groups offered different lenses on peace in society, whilst bound together by a sense of how governance, societal context, and community values prove consequential for everyday life. We saw a multi-layered awareness of the different factors responsible for sustaining everyday peace. This plurality of respondent stances is often obscured in dominant representations of peace efforts within and outside Mauritania, and in the elusive search for representing a ‘local community’ and a legitimate ‘community consensus’ in global peacebuilding initiatives. Our study challenges the assumption that local communities speak with one voice, alerting us to the fact that divergent views are not simply background noise, but socially and politically meaningful.

Who then speaks for the community when there are competing logics of everyday peace? Participatory research in a city like Nouakchott will reveal shared understandings, but also contradictory or competing stances in how urban residents locate responsibility and imagine change. In their own research, Lehrs et al. (2023) argued that ‘seeing peace’ like a city is notably different from ‘seeing peace’ like a state, because urban local actors (e.g., residents and community leaders) understand peace as tolerance in everyday life, whilst government policy actors (e.g., diplomats) concern themselves with proposals for peace and security promotion. This disconnect between city- and state-centric visions of peace is another example of differences in reasoning, local responsibility, and perceived agency in ushering proposals for change. Divergent framings will reveal how knowledge about peace is stratified — not just by social identity or ideology, but by one’s structural relationship to the state. A local community, as invoked in many peacebuilding frameworks, is not a unified actor but a heterogenous set of actors with overlapping and sometimes contradictory stances. Furthermore, Jirmanus et al. (2021) cautioned that structural inequalities will often limit the participatory and emancipatory possibilities of community-based participatory approaches. This means that paying attention to everyday reasoning and the plurality of respondent stances does not guarantee that citizens and civil society actors will be empowered to raise their voices and take action in everyday life, given limits to personal and relational agency in conflict-affected societies. In practice, what is often interpreted as political apathy or disconnection from formal governance may be reflecting a reasoned stance: a belief that meaningful change happens not through political engagement, but through managing one’s immediate social or family environment. Understanding this perspective helps recalibrate peacebuilding efforts that are otherwise misaligned with people’s lived expectations.

4.2 Envisaging room for change

In discussing everyday peace, respondent groups offered local knowledge from their own perspective. The novelty of fuzzy cognitive mapping exercises, however, consisted in revealing the fundamentally different logics about what aspects of the peace ecosystem could or should be changed. The scenarios showed that differences between groups were not merely epistemological, but sociopolitical — they reflected each group’s position within society, knowledge of institutions, and experience of structural constraints or social privilege. Indeed, social and political subjectivities were at the root of people’s expectations of change. Some respondents readily engaged the state as a potential vehicle for peace; others bypassed state institutions, investing instead in economic security and social repair. Recognizing these divergent logics is critical for designing peacebuilding interventions that resonate with the lived realities of the people they intend to serve.

Our intergroup comparison served to recognize potential blind spots in peace-related knowledge and also to open up important spaces for dialogue and potential intervention. Strikingly, while career diplomats approached everyday peace as current and future agents of their government’s authority over ordinary citizens, community members did not consider the government’s reach to effectively drive change in family and community-level relations. The prioritization of which levers of change – or pathway to peace – was perceived to be important, or ripe for change, reflected how respondents envisioned their agency and articulated their concerns.

Mauritanian students were clearly preoccupied with the kind of system corruption that strangled economic opportunities and the social mindset that might allow lives to flourish: they discussed the nexus of economic status, instability, co-existence, and self-fulfillment. In contrast, knowing that everyday life is often precarious, refugees thought that arresting the “evils” of social biases was paramount: fairness in social structure was a guarantor of everyday peace. For their part, diplomats — aligned with their roles within state systems — emphasized having fair, coherent institutional structures as fundamental processes, connecting the justice system with the ability to work and to resolve disputes. Scholars looked to how the system and social behaviors would impact everyday peace, social cohesion, and a respect for difference. They discussed tarbiya [Arabic] as a form of moral and social upbringing that binds communities together, and cousinage [French] as the creative practice of conflict resolution habitually deployed in the Sahel. Tarbiya, in Islamic and Mauritanian contexts, conveys a broader notion of social and moral formation that extends beyond formal education, encompassing respect for elders, proper comportment, and the transmission of communal values through family and religious life. Cousinage refers to ritualized teasing between families, clans, or ethnic groups, a culturally recognized way to maintain harmony, diffuse tension, affirm cross-cutting social ties, and mediate potential conflict (Davidheiser, 2006; Dunning and Harrison, 2010; UNESCO, 2014). Both tarbiya and cousinage express the everyday ethics of coexistence: the first through disciplined socialization and moral restraint, the second through humor and reciprocal teasing. These practices were invoked as small acts of peace — concrete examples of the ways people navigate social tensions with purposeful behavior.

By contrast, townspeople framed the drivers of everyday peace in terms of collective responsibilities to create an “appropriate environment” at home and in the community. While men discussed the importance of a secure income, women discussed issues of cohabitation. Ordinary citizens discussed peace in intimate terms: financial independence, family dynamics, and moral values shaped by religion and tradition. They rarely mentioned state structures, suggesting a logic of self-reliance, seeing change as most possible in the domain of social values, interpersonal harmony, and moral behavior. Women, for example, invoked the economic crisis as engendering inequality and unease across social groups. The framing of discussions also reflected the influence of gender and Islam in Mauritanian society. Women are custodians of the home life – as caregivers, mothers, and models of appropriate religious comportment – and also custodians of important tenets of the Islamic faith that specifically relate to understanding peace (Kadayifci-Orellana, 2015). Even if governance and structural factors disrupted citizen lives, addressing injustice, inequality, and social discrimination was a family-level responsibility.

As revealed in this study, peacebuilding approaches need to be very attentive to social issues, livelihoods, and everyday behaviors, as well as to institutional governance. This hints to the distinction between peacebuilding and state-building made in published work on everyday peace (Firchow, 2018). In Mauritania, a main concern was guarding against a descent into insecurity, violence, and social disruption, given the economic crisis, the problems of illegal migration, and other threats to everyday peace. From the perspective of respondents, the guarantors of everyday peace included stable co-existence, economic independence, and fairness – hinting that government institutions were effective only if they helped people build their lives and secure a socioeconomic footing. Peacebuilding policies that increased financial empowerment and social cohesion would therefore resonate strongly with civil society actors who saw themselves as largely removed from state institutions.

One key consideration was the social contract regulating interactions across generations and socioeconomic groups. Mauritanians have experience with political and social narratives exploiting ethnic and social diversity as a political wedge issue to foster insecurity, instability, and armed conflict (N’Diaye, 2010). The traditional caste system and the history of ethno-racial politics continue to influence formal and informal relationships (Villalón and Bodian, 2021), even as social, economic, and educational opportunities change across generations. Gender narratives work within this enormous social and ethnic diversity (da Silva, 2022). For this reason, preserving everyday peace while addressing cultural diversity was central to discussion. As one research team member reflected, “bringing together communities can help us dissect some complicated concepts […]. This cultural diversity we have is so strong, very enriching to the country. We’re very proud of it, but there is still always the risk that people might tend to play on that to create some problems.” She emphasized why it was “important not to take for granted the peace that Mauritania has, in contrast to neighboring countries,” concluding that “peace is priceless.”

4.3 Study strengths and limitations

Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping is a tool for understanding systems from the vantage point of different stakeholders (Panter-Brick et al., 2024). The methodology has been used over the last two decades across multiple disciplines, including business, medicine, the social sciences, and the natural sciences. Our research is the first to leverage FCM to visualize the drivers of everyday peace and to explore system change with diverse stakeholders as potential spaces of peacebuilding intervention. The method has three main limitations: the maps do not describe all factors of influence; bias can arise from participant sampling and power dynamics; and hypothetical scenarios provide limited insights to potential systems change (Panter-Brick et al., 2024). A cognitive map will be sensitive to the views of group participants, which means that intra-group dynamics might affect inter-group comparison. For example, participant bias may arise from vocal and reticent respondents contributing differentially to the discussion — this can be mitigated with careful group facilitation. Bias can also arise from convening groups of respondents that are not wholly representative of targeted sectors in society — a limitation shared with other qualitative research methodologies. While it is possible to run several FCM sessions per stakeholder group, then aggregate maps for that group, this entails combining (and reducing) driver variables for scenario analysis, aggregating in ways that respondents did not. In summary, though centered on Nouakchott, this study breaks new ground as the first to advance the concept of everyday peace in Mauritania, translating local experience into a broader conceptual and empirical conversation.

Engaging in FCM proved a valuable experience to respondents. Mauritanians stated that they wanted to avoid the kind of violence, instability and social unrest that plague their Sahelian neighbors. Respondents felt a sense of ownership: women from the local community were among the most enthusiastic about the research process, asking to take selfies in front their ‘peace map,’ and sending those pictures to friends and family through WhatsApp. Local research team members noted that fuzzy cognitive mapping helped to analyze peace systems at different levels - community, municipal, national, and international levels. Participants thus concluded that FCM could help them advance toward peace, because visual mapping allowed them to discuss and identify specific factors sustaining good governance, coexistence, stability, and community values.

4.4 Implications

This brings us to consider practical implications for decision-making and policy formulation. In peace promotion, what is needed is “a data-driven path to align international and local priorities and increase the chances of success from the perspective of all stakeholders” (Firchow, 2018, p. 6). Participatory methodologies, based on inductive reasoning, can help to bridge quantitative and qualitative data and to harmonize local with international approaches to peacebuilding. They help describe attitudes, institutions, and structures that create peaceful and flourishing societies (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2024). This study, specifically, helps to make explicit whose peace we are talking about and, through scenario modeling, which drivers of everyday peace might empower impactful change. As a next research step, we are collaborating with other research teams to systematically compare findings generated through fuzzy cognitive mapping (FCM) and the Everyday Peace Indicators (EPI) approach – two hybrid methodologies that integrate participatory processes with both inductive and deductive analytical frameworks. Fuzzy cognitive mapping (FCM) complements the Everyday Peace Indicators (EPI) approach by modeling how people reason about causal relationships and pathways to change. Combining inductive reasoning from qualitative discussion with deductive scenario modeling, FCM visualizes how participants think about existing conditions and possible transformations. Crucially, it adds a forward-looking dimension by testing how people anticipate system change and the effects of hypothetical interventions. In this way, the method builds on everyday peace research by linking locally grounded indicators to the interpretive reasoning through which people envision and anticipate change.

Aware of the need for cross-over approaches, the Diplomatic Academy and the University of Nouakchott in Mauritania are currently building a joint curriculum on peace promotion, with inputs from diplomats and scholars from the Sahel and North African region. A deeper dive with fuzzy cognitive mapping could help innovate current training modalities and flesh out a diversity of viewpoints on drivers of everyday peace. To offer a hypothetical example, FCM exercises could be one way of grounding a strategic study of how national or regional policies resonate with diverse social groups within a given country. Using FCM to address pathways to peace is particularly useful for diplomats tasked with developing policies on societal development or conflict-resolution strategies. It is useful to identify areas of disconnect. Indeed, the language that diplomats use in conflict resolution might prove more effective if drawn from notions of concession and tolerance at community level, rather than from what Robert Cox called “problem-solving approaches” used in liberal peacebuilding strategies (Kadayifci-Orellana, 2015).