- Department of Graduate Studies in Business and Management, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

This study examines global and Zambian progress on women’s parliamentary participation from 1995 to 2025, in line with Section G of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. It highlights the developmental significance of inclusive political representation and the persistent underrepresentation of women, averaging below 30% globally and in Zambia. The study employs a qualitative desk review methodology, systematically analysing academic literature, United Nations documents, and national policies and reports to synthesise existing knowledge and trends. Descriptive statistics are used to illustrate participation patterns over the past three decades, whilst qualitative analysis explores structural and societal barriers that continue to constrain women’s full engagement in political life. Despite notable policy reforms and gender responsive measures, progress remains slow. Evidence shows that when women are meaningfully represented, policies better reflect diverse needs and foster inclusive development. To accelerate change, the study recommends targeted measures including gender quotas, gender-responsive electoral systems, legal reforms, and institutional support mechanisms such as mentorship, training, and financial access to strengthen women’s political agency.

1 Introduction

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPfA) was adopted at the Fourth World Conference on Women, held from 4th to15th September, 1995, in Beijing, China. The agenda of the Beijing Conference was to review progress made since the adoption of previous global conferences on women. The Beijing Conference helped to unveil women’s issues that had remained unaddressed (Orisadare, 2019). It set a 30% minimum threshold for representation of women in decision-making bodies, with a goal of equal (50/50) participation and called for the removal of barriers to women’s equal participation in political life, including structural discrimination, patriarchal norms, and underrepresentation in leadership roles (United Nations, 2015). The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPfA) became the most comprehensive and forward-looking comprehensive policy agenda, global framework and plan of action for achieving gender equality and the human rights of all women and girls, laying the foundation towards just, equitable and inclusive societies that benefit all (United Nations, 2025). It outlines 12 critical areas to address gender inequalities and achieve women’s empowerment. Zambia is amongst the 189 countries which unanimously adopted the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which outlines 12 critical areas of concern for advancing women’s empowerment, including women’s political participation.

Scholars such as Tripp et al. (2009) and Krook (2010) have documented the global rise in women’s political representation, attributing gains to quota systems, party reforms, and international pressure. However, Goetz and Hassim (2003) cautions that formal inclusion does not guarantee substantive influence, especially in contexts where patriarchal norms and institutional inertia persist. In the Zambian context, Geisler (1995) highlight the historical and structural constraints that have limited women’s access to political leadership, despite policy commitments. This study builds on these insights by examining Zambia’s progress since the Beijing Platform for Action, assessing not only numerical representation but also the quality and impact of women’s participation in shaping development outcomes.

To situate these commitments within the broader discourse on governance and inclusion, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by political participation and, more specifically, how women’s political participation is conceptualised within this study. Political participation refers to voluntary activities by the public to either directly or indirectly influence public policy and also the selection of individuals who make these policies (Ojo, 2022). It can also be referred to as lawful activities that citizens engage in to influence the selection of government officials including the actions they take or fail to take (Verba and Nie, 1987, as cited in Ojo, 2022). Whilst these definitions highlight the broader understanding of political participation as a mechanism through which citizens exercise agency in governance, it is equally important to consider the gendered dimensions of such engagement. Women’s political participation refers to the full and equal involvement of women alongside men in every sphere of political life, including all stages of decision-making processes (Sahu and Yadav, 2018).

The Universal Declaration on Human Rights of 1948 states that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights and further states that everyone is entitled to all rights and freedoms without distinction of any kind including sex. Women’s political participation is a matter of human rights, gender equality, inclusive growth and general development as indicated in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 5 that states gender equality for men and women (Dialo and Sarumi, 2025). The Concept of Political Participation is therefore a development approach, which recognises the need to involve disadvantaged segments of the population, who include women in the design and implementation of policies. In recent years, the strengthening of women’s participation in all spheres of life has become a major issue in the development discourses because socio-economic development cannot be fully achieved without the active involvement of women in the decision-making levels in all society (Endale, 2012). Sustainable Development Goal 5.5 calls for the promotion of inclusive and equitable representation of women in leadership across political, economic, and public spheres, ensuring their full and meaningful participation in decision-making processes at all levels (United Nations, 2015).

Political life encompasses the range of activities and institutional processes through which individuals and groups participate in governance and policymaking, including voting, campaigning, and involvement in political parties and civic organisations. The foundational principles of women’s political engagement are articulated in the Convention on the Political Rights of Women, which affirms that women are entitled to vote, stand for election, and hold public office on equal terms with men, without discrimination, thereby establishing a legal basis for gender-equitable participation in governance and public service (United Nations, 1952). Women’s economic life encompasses their engagement in activities related to production, income generation, asset ownership, and financial decision-making, both within households and in broader market systems. It includes participation in formal and informal labour, entrepreneurship, access to credit and property, and influence over economic policies, all of which are essential for individual empowerment and inclusive development outcomes (UN Women, 2024). Public life involves the participation of individuals in societal affairs and community activities that impact collective well-being. This includes women’s involvement in civic organisations, community service, and public policy discussions, reflecting an active engagement in shaping societal norms and values, as emphasised in the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s 2025 Meaningful Engagement and Public Participation policy (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2025).

Enhancing women’s political participation is not only a matter of equity but a critical driver of inclusive and sustainable development. Political participation is therefore a prerequisite for political development because improving women’s political participation, given that they constitute over a half of the world’s population may help to advance political development and improve the quality of women’s lives (Seyedeh et al., 2010, as cited in Kassa, 2015).

In 2025, 30 years after the Beijing Conference, women’s political participation on average remains below the recommended 30% threshold, a fact acknowledged by the United Nations (UN) during the 69th session of the Convention on the Status of Women (CSW) in New York from 10th – 21 March 2025 at which the review of progress achieved in attaining gender equality and the empowerment of women 30 years after the Beijing Platform for Action (BDPfA) was discussed. Unanimously, a political declaration was adopted by all the government delegates to the conference. This declaration reconfirms State Party commitments to women’s empowerment and reaffirms that essential elements for sustainable development include gender equality and the empowerment of women and also acknowledges that no country has yet fully achieved gender equality and the empowerment of women, 30 years after the BDPfA was adopted in 1995 (United Nations (Commission on the Status of Women), 2025). Global assessments indicate significant but uneven progress towards women’s equal political participation. This study critically reflects on the global progress made under Section G of the BDPfA with regards to women’s political participation in parliament and how their participation contributes to development, three decades later.

1.1 Statement of the problem

Women’s political participation remains limited across many countries, despite three decades of global commitments to gender equality and inclusive governance. Frameworks such as the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPfA) and Sustainable Development Goal 5 have catalysed policy reforms and normative advances. Yet most countries, including Zambia, continue to fall short of the 30% representation threshold for women in parliament. This persistent underrepresentation reflects not only unmet numerical targets but also the enduring influence of structural and systemic barriers.

In Zambia, these challenges are further compounded by localised dynamics. Although the country has ratified key international instruments and adopted national gender equality policies, women’s substantive participation in politics remains limited. Existing scholarship predominantly examines descriptive representation, often neglecting the qualitative dimensions of women’s political agency and their contributions to development outcomes. Dominant theoretical approaches also tend to generalise across regions, overlooking the role of context-specific institutional arrangements and lived experiences in shaping women’s leadership trajectories.

Against this backdrop, the study interrogates both the extent of progress and the developmental implications of women’s political participation. The study is guided by the following research question: To what extent have women achieved the 30% political participation threshold outlined in the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA), both globally and in Zambia, and in what ways has their participation influenced development outcomes?

1.2 Study objectives

The overall aim of the study is to examine the progress in meeting the minimum threshold of women’s political participation outlined in the BDPfA and the contributions women parliamentarians make towards development outcomes. The specific objectives of the study are to:

1. Assess the global, regional and national progress made towards achieving the 30% minimum threshold of women’s participation in parliament 30 years after the BDPfA.

2. Examine the contribution of female parliamentarians towards development.

2 Literature review

2.1 Introduction

This literature review critically examines the evolution of global, regional, and national frameworks that have shaped the agenda for women’s political participation over the past three decades. It explores both the normative foundations and the scholarly debates surrounding the effectiveness of these instruments in translating commitments into substantive political change. By situating Zambia within this broader landscape, the review provides the conceptual and empirical grounding for assessing progress towards the 30% representation threshold and interrogating the quality of women’s parliamentary participation and their contribution to development outcomes.

2.2 Historical context

The agenda for accelerating women’s political participation globally can be traced back to the first United Nations World Conference on women held from 19 June and 2 July 1975 in Mexico City, Mexico. This landmark event was the first international conference organised by the United Nations to focus solely on women’s issues. It marked a significant turning point in policy directives, positioning women not merely as beneficiaries but as critical actors in the formulation and implementation of policies (United Nations, 1976). The conference led to the adoption of two key documents: the World Plan of Action and the Declaration of Mexico on the Equality of Women and Their Contribution to Development and Peace. These documents emphasised the importance of women’s full participation in development and peace processes, laying the groundwork for subsequent international efforts to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment (United Nations, 1976). It laid the foundation for the second conference held in Copenhagen, 1980, the third conference held in Nairobi in 1985 and the fourth conference held in Beijing in 1995.

Whilst the Mexico City Conference set the basic framework for advancing women’s development, the Copenhagen Conference reviewed these first goals with a focus on employment, health, and education; the Nairobi Conference presented specific plans to address the ongoing obstacles impeding progress; whilst the Beijing Conference, which culminated in the adoption of the BDPfA, was a major turning point (Belliard, 2021). The BDPfA remains the most comprehensive framework for advocacy for advancing women’s economic, political and social participation in all spheres of life (Greavs and Varsha, 2025). Other legally binding regional and international frameworks have since been developed to complement the BDPfA. These include the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) which obligates states to ensure women’s equal participation in political and public life under Article 7. At regional level, frameworks such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol on Gender and Development (2008, revised 2016) calls for 50% women’s representation in decision-making positions across all sectors; and the African Union Agenda 2063 aspires for full gender parity and representation of women in all governance structures.

Scholars have long debated the effectiveness of these frameworks in translating normative commitments into substantive political change. Tripp et al. (2009) argue that whilst instruments like CEDAW and the BPfA have catalysed legal reforms and increased women’s visibility in political spaces, their implementation often falters due to entrenched patriarchal structures and limited institutional accountability. Goetz and Hassim (2003) reinforces this critique, emphasising that formal representation alone does not yield transformative leadership, especially in contexts where women’s political roles are symbolically acknowledged but structurally constrained. In the Southern African region, Geisler (1995) critiques the tokenistic inclusion of women in political institutions, noting that regional protocols like the SADC Gender Protocol, though ambitious, lack robust enforcement mechanisms and sustained political will. These perspectives converge on a critical insight: numeric representation is insufficient without mechanisms that ensure meaningful participation and influence.

Building on these critiques, the analysis underscores that whilst global and regional commitments have created normative pressure for inclusion, the translation of these commitments into transformative governance remains uneven. By examining the depth and quality of women’s political participation, this review contributes to a broader discourse that moves beyond formal inclusion to explore the institutional, cultural, and policy conditions necessary for gender-responsive leadership. In doing so, it addresses the gap between symbolic representation and substantive agency that Tripp, Goetz, and Geisler highlight, offering a dual-level analysis that situates Zambia’s political landscape within broader global efforts to advance inclusive governance and gender-responsive leadership.

2.3 Global and regional trends

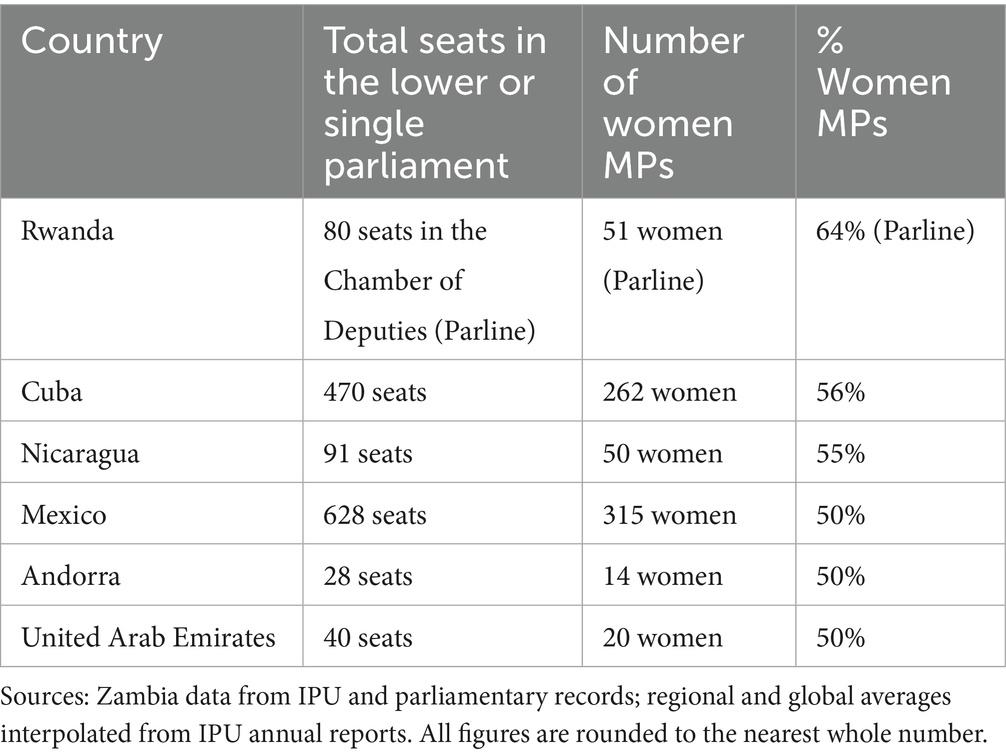

Since the adoption of the BDPfA in 1995, women’s political participation in parliament has doubled. However, only 1 in every 4 parliamentarians world wide is female (United Nations, 2025) and only six countries have achieved 50% or more women in parliament in a single or lower house (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). These countries include Rwanda with 64%, Cuba with 56%, Nicaragua with 55%, Andora with 50%, Mexico with 50% and the United Arab Emirates with 50% (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). Table 1 presents the actual number of female parliamentarians in countries that have achieved 50% or more representation, alongside total parliamentary seats, to illustrate the scale and significance of these gains in real terms.

Gender Quotas, and gender responsive electoral reforms have played a significant role in increasing women’s political participation (Dahlerup, 2006). This aligns with the critical mass theory which emphasises that the presence of a sufficient number of women is essential to influence institutional culture and decision-making dynamics (Lefley and Janeček, 2023). To ensure conceptual clarity, this study refers to both legislated and voluntary quotas collectively as gender quotas, whilst reforms to electoral rules and procedures are described as gender-responsive electoral systems. The most pressing challenges for women’s political participation include lack of constituents and lack of financial resources (Ballington and Kahane, 2015). The political participation of women is further impeded by the prevalence of male-dominated political frameworks, inadequate party and financial backing, weak connections with supportive entities, a lack of leadership training, and electoral systems that frequently disadvantage women (Ballington and Kahane, 2015). The political environment is also shaped by deeply rooted informal elements, sometimes referred to as “unwritten rules,” which include customs, cultural practises, traditions, socialisation, and gender stereotypes which manifest as gender-based violence and perpetuated by the media, electoral systems the way elections are managed as well as the unequal access to financial and other resources (Gender Links, 2022).

2.4 Zambia’s policy commitments and progress

Zambia has committed to the BDPfA and has ratified and domesticated key international and regional frameworks on gender equality, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Maputo Protocol promoting women’s participation in politics. National frameworks such as the Gender Equity and Equality Act (2015) and the National Gender Policy (2014) underscore the government’s commitment to increasing women’s political representation. Despite these commitments, Zambia’s progress has been inconsistent. As of 2025, women held only 15% of parliamentary seats (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025).

Zambia employs the First Past the Post (FPP) electoral system for electing members of parliament. The First Past the Post (FPP) electoral system allows the candidate with the most votes in a constituency to win a seat, regardless of whether they achieve a majority (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, 2022). This system has been cited as having an adverse impact on women’s political representation. In contrast, countries that employ proportional representation (PR) systems allocate legislative seats to political parties in proportion to the share of votes they receive (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, 2022). Similarly, those adopting mixed-Proportional Representation (PR) electoral systems, which combine proportional and majoritarian elements, record significantly higher levels of women’s political representation in comparison to those utilising first past the post electoral systems (Paxton et al., 2010). From 1975 to 2000, with the exception of the atypical instance in 1980, PR systems exhibited a consistent average rise of 2.5% in the representation of women. This trend corresponds with findings from cross-sectional studies indicating an increase of 2 to 3.5% in women’s representation within PR systems (e.g., Kenworthy and Malami, 1999; Paxton, 1997, as cited in Paxton et al., 2010).

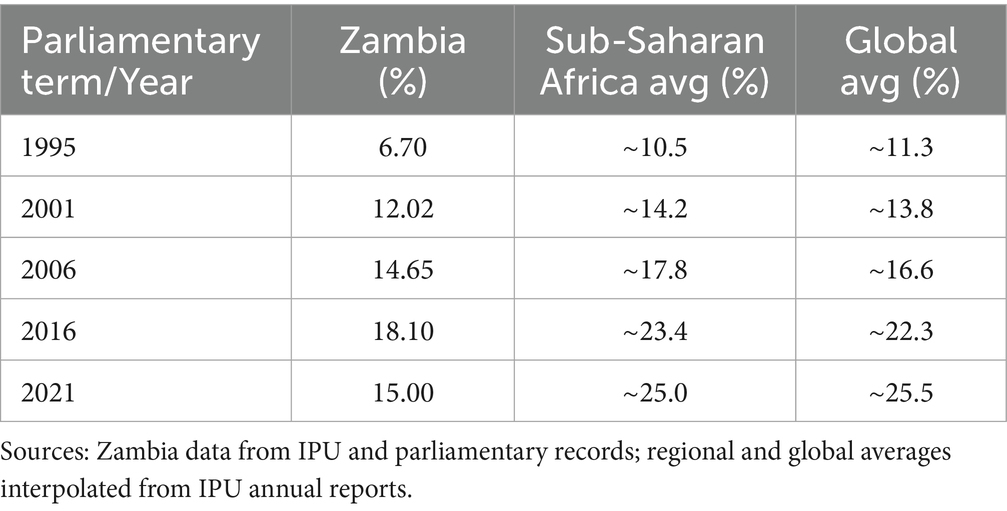

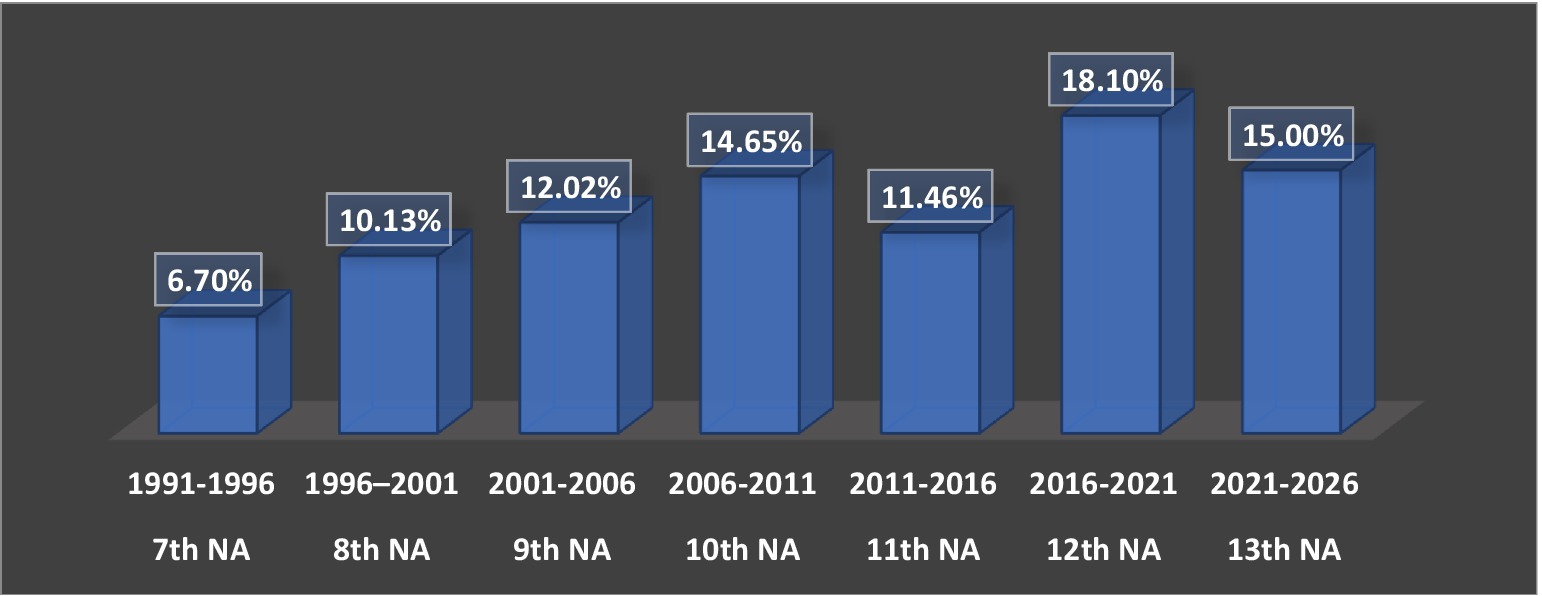

Zambia’s representation of women in parliament began at 6.7% in the early 1990s, rising to 18.10% by 2016 before declining to 15.00% in 2021, placing Zambia below both regional and global averages. Whilst this reflects some progress, Zambia has consistently trailed behind both Sub-Saharan African and global averages. The comparative data illustrated in Table 2 underscores the limitations of Zambia’s First Past the Post (FPP) electoral system and reinforces the argument for structural reforms to align with international benchmarks.

The reviewed literature demonstrates that whilst global and regional frameworks such as CEDAW, the BDPfA, and the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development have provided a strong normative foundation for advancing women’s political participation, their translation into substantive political change remains uneven. Scholars like Tripp, Goetz, and Geisler caution that numeric gains in representation often mask deeper structural and cultural barriers that limit women’s influence in decision-making. Comparative evidence shows that proportional representation systems tend to yield better outcomes than first past the post systems, further underscoring the importance of structural reforms. Zambia’s experience mirrors these broader trends: despite ratifying key international and regional commitments and enacting progressive national policies, women’s parliamentary representation remains below regional and global averages, constrained by electoral systems, patriarchal norms, and weak institutional accountability. Overall, the literature highlights that achieving meaningful participation requires moving beyond symbolic representation to addressing institutional, cultural, and systemic barriers that hinder women’s substantive agency in governance and development.

2.5 Theoretical framework

This study is underpinned by the Feminist Theory which offers the most appropriate framework for interrogating women’s political participation and developmental outcomes, 30 years post the BDPfA. Feminist theory is a political and intellectual framework that equips individuals to critically examine the injustices they face and to construct arguments for social change (McCann and Kim, 2017). It focuses on generating knowledge about women’s oppression and uses that understanding to inform strategies aimed at resisting subordination and advancing women’s well-being. By foregrounding power relations, gendered norms, and institutional biases (Tong, 2018; Lorber, 2012), Feminist Theory enables a critical examination of how legal, electoral, cultural and social systems shape gendered outcomes in political representation (Mackay et al., 2010).

It unveils the structural inequalities entrenched in patriarchal dynamics that limit women’s political participation whilst offering strategies for overcoming these barriers (Mackay et al., 2010). This theoretical lens compels inquiry into the effectiveness of gender quota systems, the limitations of first-past-the-post electoral arrangements, and the broader institutional conditions that hinder progress towards the 30% participation threshold outlined in the BPfA, both globally and in Zambia. In the context of electoral policy, Feminist Theory offers a critical lens for evaluating how systems such as proportional representation, candidate selection processes, and gender quota mechanisms either reinforce or challenge patriarchal power structures. It underpins the design of institutional reforms that advance gender-responsive governance, moving beyond symbolic inclusion towards substantive influence. These principles also extend into international relations, where Feminist Theory prioritises intersectional equity, human rights, and inclusive diplomacy (UN Women, 2024).

Beyond representation, Feminist Theory also addresses the second dimension of the research question: the developmental impact of women’s political participation. Feminist analysis demonstrates that when women hold political power, policy priorities often shift towards health, education, social protection, and inclusive economic growth, domains central to sustainable development (Mackay et al., 2010). Women’s political presence, therefore, is not merely a matter of numerical inclusion but a transformative force for equitable development outcomes.

By centring the analysis on Feminist Theory, the study engages its guiding question: to what extent have women achieved the 30% political participation threshold outlined in the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA), both globally and in Zambia, and how has their participation influenced development outcomes? Feminist Theory not only elucidates the structural barriers that hinder progress towards this benchmark but also provides a framework for identifying transformative strategies that aligned with the study’s objectives.

2.6 Research gap

Women’s participation in political decision-making remains limited across many countries, despite three decades of global commitments to gender equality and inclusive governance. Frameworks such as the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action has catalysed policy reforms and normative advances. Yet most countries, including Zambia, continue to fall short of the 30% representation threshold for women in parliament. This persistent underrepresentation reflects not only unmet numerical targets but also the enduring influence of structural and systemic barriers. In Zambia, these challenges are further compounded by localised dynamics. Although the country has ratified key international instruments and adopted national gender equality policies, women’s substantive participation in political processes remains limited.

Existing global and regional studies offer useful analyses of trends and enabling factors; however, there remains a notable gap in empirical research that directly connects women’s political leadership to measurable development outcome. Dominant theoretical lenses often generalise across regions, failing to account for the influence of localised institutional arrangements and the lived experiences that shape women’s leadership trajectories. This gap limits the ability of policy makers to fully appreciate the development value of inclusive political systems.

Against this backdrop, this study seeks to address this gap by generating evidence-based insights and recommendations to accelerate gender parity in political leadership and to highlight the development potential lost due to the continued underrepresentation of women in parliament. It interrogates both the extent of progress and the developmental implications of women’s political participation. The study is guided by the following research question: To what extent have women achieved the 30% political participation threshold outlined in the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA), both globally and in Zambia, and in what ways has their participation influenced development outcomes?

3 Methodology

This study employed a qualitative desk review methodology to examine trends in women’s representation globally and within Zambia’s Parliament from 1991 to 2025. The review was conducted between January and April 2025 and drew on a diverse range of academic and institutional sources to ensure both historical depth and contemporary relevance.

Google Scholar served as the primary platform for identifying peer-reviewed literature, using targeted keywords such as “Beijing Platform for Action,” “Development,” “Parliament,” “Women’s Political Participation,” and “Zambia.” No date restrictions were applied, allowing for the inclusion of both historical and contemporary coverage.

To complement the academic literature, a targeted review of global policy frameworks, including the United Nations’ Beijing Platform for Action and Sustainable Development Goal 5, was undertaken. International databases were also consulted to extract validated statistics and comparative insights. These included the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), which provides longitudinal data on women in national legislatures; UN Women, which offers thematic reports and country-level analyses on gender and governance; and the World Bank, which contributes governance indicators and gender-disaggregated development metrics. National reports and parliamentary records were reviewed to triangulate findings and enhance empirical robustness.

Sources were selected based on relevance, credibility, and thematic alignment with the study’s objectives. Particular attention was paid to identifying gaps in empirical coverage, policy coherence, and implementation outcomes. Only materials that explicitly addressed women’s political participation, either empirically through data, case studies, or analysis, or normatively through policy frameworks and commitments, were included. Both global and Zambian sources were considered to enable comparative and context-specific insights. Publications lacking substantive focus, offering anecdotal commentary without empirical or policy relevance, or unavailable in English were excluded.

This multi-source strategy enabled a comprehensive synthesis of academic literature and institutional reports, facilitating a nuanced understanding of both the quantitative shifts in representation and the normative frameworks shaping the global and Zambia’s gender and governance landscape. Whilst statistical data were used to illustrate participation trends over the past three decades, these figures served primarily to contextualise thematic insights rather than to support formal statistical testing.

This multi-source strategy enabled a comprehensive synthesis of academic literature and institutional reports. By so doing, it facilitated a nuanced understanding of both the quantitative shifts in representation and the normative frameworks shaping the global and Zambia’s gender and governance landscape. Whilst statistical data were used to illustrate participation trends over the past three decades, these figures served primarily to contextualise thematic insights rather than to support formal statistical testing. Qualitative data were analysed through manual coding, with themes identified using structured matrices and tables, and key findings, policy frameworks, and author insights summarised in Excel and Word tables. Quantitative data were analysed using Excel to organise and compute percentages, counts, and trend tables, providing descriptive statistics to illustrate shifts in women’s political representation over time.

The results were derived through thematic analysis, enabling a structured synthesis of findings that reflect the interplay between global commitments and local governance realities. This approach contributes meaningfully to both scholarly discourse and policy development by distilling patterns that reflect systemic gaps and opportunities for reform. In addition to thematic synthesis of qualitative data, descriptive statistical analysis was applied to quantitative datasets obtained from IPU and Zambia Parliamentary records. This allowed the study to illustrate shifts in women’s representation across time, providing an empirical foundation for interpreting patterns alongside qualitative findings.

4 Findings and discussions

Findings of the study reveal that 30 years post the Beijing Conference, there has been a significant increase in women’s political participation in varying degrees between regions and countries. Affirmative action measures have been identified as the major contributor to the increment. However, this increase has not yielded the desired 30% female representation in all parliaments as stipulated in the BDPfA with only few countries achieving and/or exceeding gender parity.

4.1 Trends in women’s global representation in parliament (1995–2025)

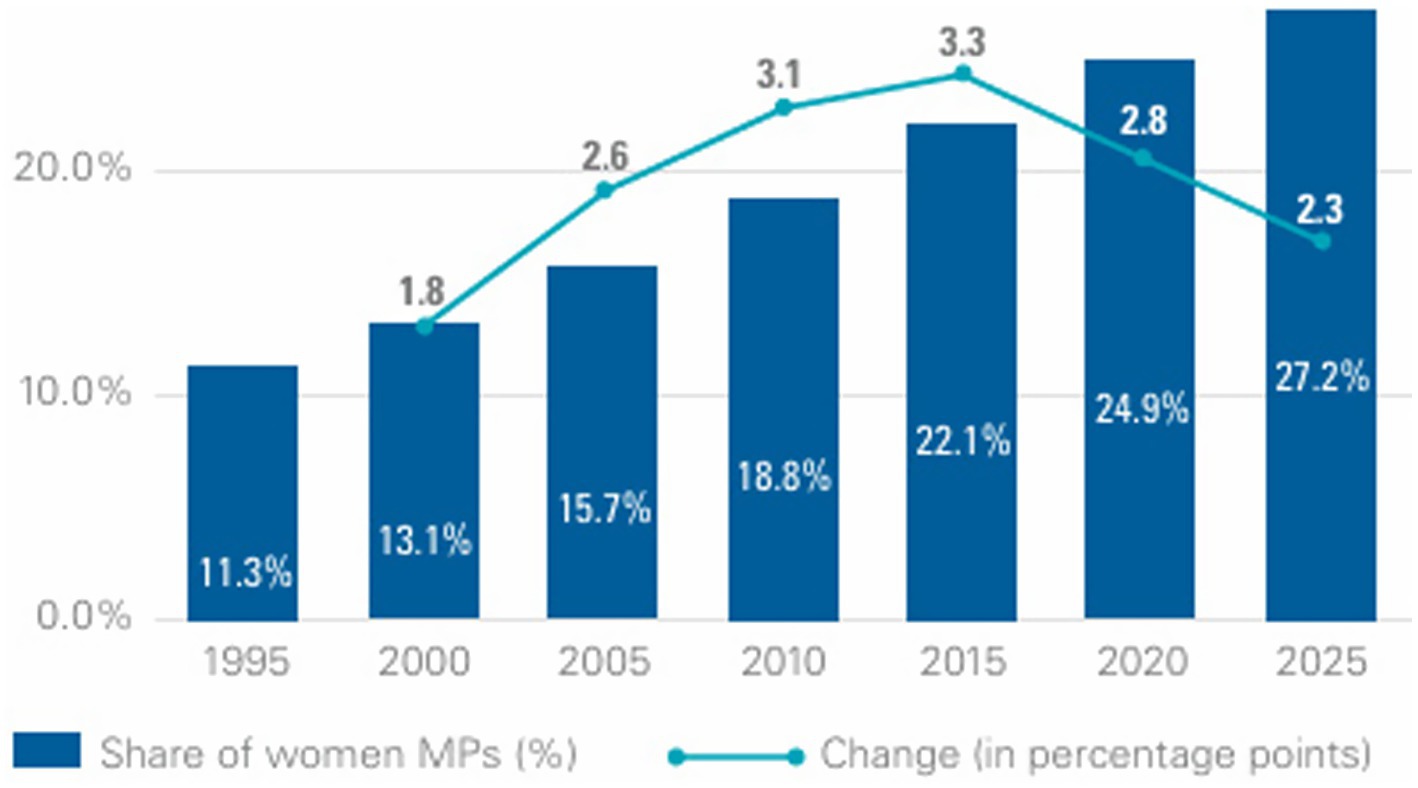

Analysis of data for the period 1995–2025 shows that despite an increase in women’s political participation in parliament, gender parity in parliament has not been achieved in many parliaments. Women still occupy fewer seats in parliament compared to their male counterparts. Although global averages show that there has been a steady increase in women’s political participation at parliamentary level from 11.3% in 1995 to 27.2% in 2025 (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025) as reflected in Figure 1. These global averages still show that women’s participation is well below the 30% threshold and the pace at which women’s political participation is increasing is very slow. For instance, in 2025, women’s political participation only increased by a meagre 0.3% from 2024 (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025).

Figure 1. Women’s political participation in parliament: world averages 1995–2025. Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union (2025). Women in parliament: 1995–2025, reproduced with permission from Inter-Parliamentary Union, licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.

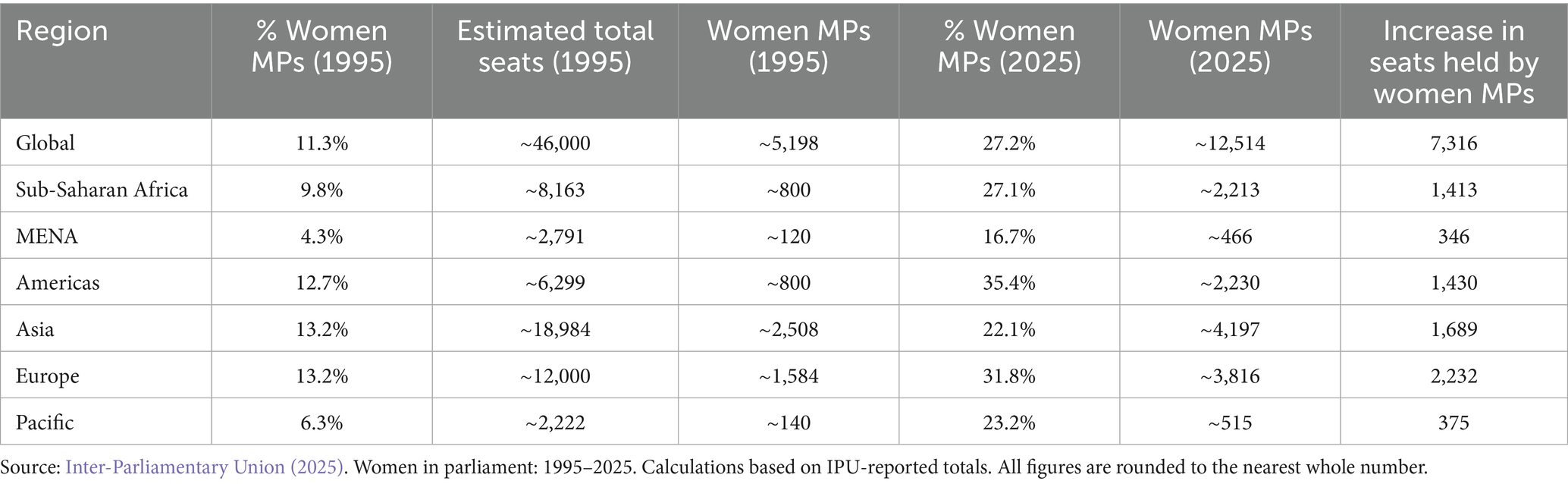

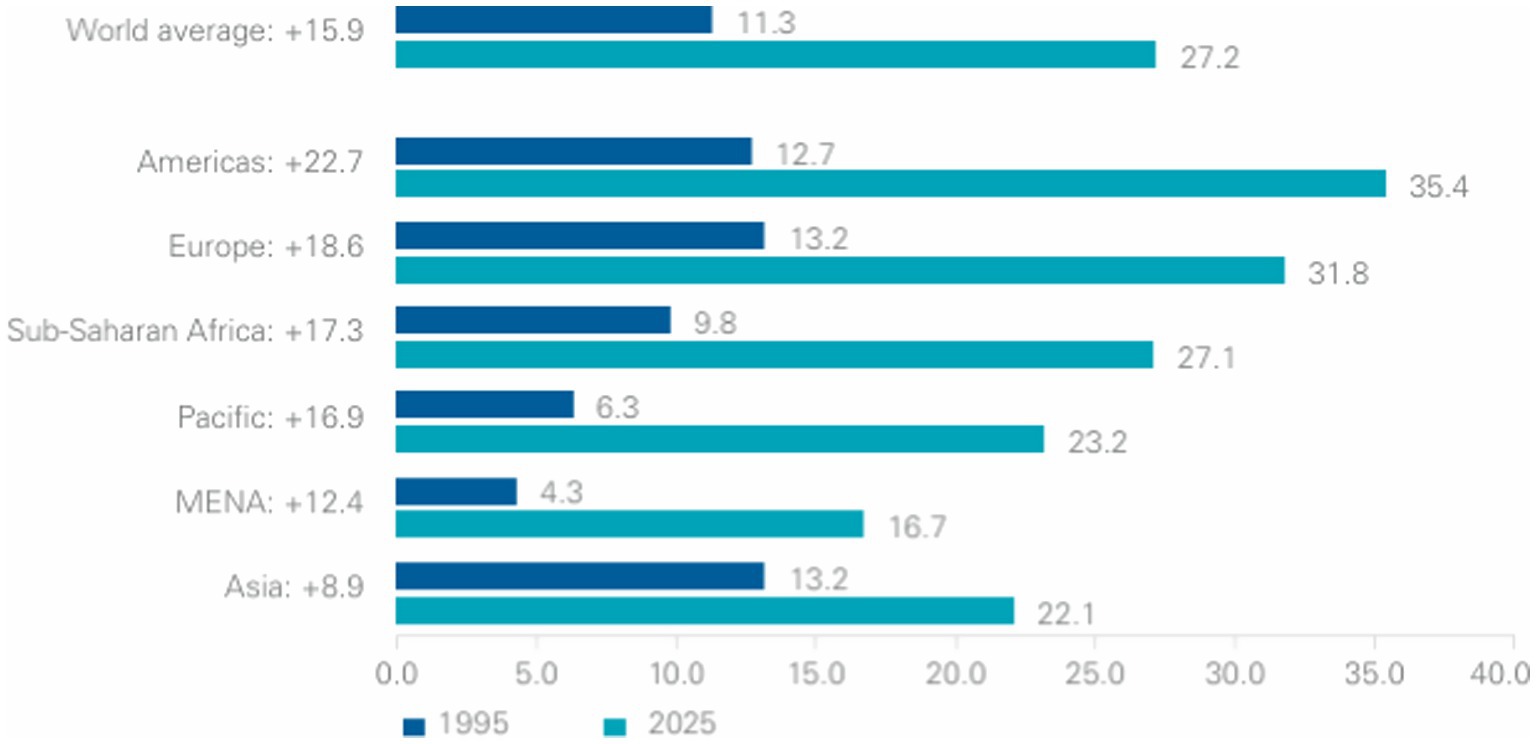

At regional level, statistics show that the Americas recorded the highest increase in women’s political participation in parliament of 22.7% from 12.7% in 1995 to 35.4% in 2025 (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). Figure 2 illustrates the divergent regional trajectories in women’s parliamentary representation between 1995 and 2025, highlighting the Americas’ substantial gains and the uneven progress across Europe, Asia, and other regions in meeting the 30% BDPfA threshold. Europe and Asia which had the highest number of women in parliament in 1995 at 13.2% only recorded an increase of 18.6 and 8.9%, respectively. The figures reflect notable regional disparities in the incremental rates. Europe and Asia which led in 1995 have been surpassed by the Americas in making progress towards attaining gender parity. Regional averages show that only the Americas and Europe have met and exceeded the 30% BDPfA threshold although they have not yet attained gender parity whilst other regional averages continue to fall below the 30% thresholds. This trend highlights the varying effectiveness of regional strategies and political will in promoting women’s political participation in parliament, underscoring the need for context specific approaches to accelerate progress towards equal representation.

Figure 2. Women’s regional political participation: a comparison between 1995 and 2025. Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union (2025). Women in parliament: 1995–2025, reproduced with permission from Inter-Parliamentary Union, licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.

In 1995, there was no single country in the world that had attained gender parity in parliament and a high number of countries (105) had <10% female representation (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). By 2025, this scenario had improved significantly with six countries having attained and/or exceeded gender parity. The greatest progress in women’s representation has been achieved by Rwanda with 63.8%; other countries that had reached and/or exceeded gender parity are Cuba with 55.7%, Nicaragua with 55%, Mexico with 50.2%, Andorra with 50% and United Arab Emirates with 50% (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). All these countries have affirmative action measures such as gender quotas, to promote women’s political participation. According to Inter-Parliamentary Union (2025), countries that have gender quotas have made significant strides in progress towards gender parity in parliament. An additional 21 countries have reached and exceeded 40% but have not yet reached gender parity and a further 42 countries ranged between 30 to 40%. There has also been a decrease in the number of countries with less than 10% female parliamentarians to 20 from 105, in 1995 with only 3 countries with zero women in parliament compared to 9 in 1995 (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). Elections held in 2024 presented an opportunity to increase women’s participation in parliament globally. However, despite the 73 parliamentary elections that took place that year, only 26.5% women were elected or appointed to parliament, a marginal increase of 1.4% from the previous elections/appointments (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). To illustrate these trends more concretely, Table 3 presents the real numbers of women parliamentarians alongside total parliamentary seats at global and regional levels between 1995 and 2025.

Literature shows that whilst there has been commendable progress in increasing women’s political participation in parliaments globally since 1995, the pace of change remains slow and uneven across regions. The global average of 27.2% women in parliament in 2025 falls short of the 30% target set by the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, underscoring the need for renewed commitment and strategic interventions. Countries that have implemented gender quotas and other affirmative action measures demonstrate that targeted efforts can yield significant gains. To achieve true gender parity, sustained political will, policy reforms, and inclusive electoral systems must be prioritised.

4.2 Spotlight on Zambia: assessing women’s political participation

Despite women in Zambia constituting 51% of the population (Zambia Statistics Agency, 2022), they remain under represented in parliament. Reflecting on the 30 years post the Beijing Conference, women’s representation in the Zambian parliament recorded a marginal increase of 8.3% from 6.7% in 1995 to 15% in 2025 and ranked 128 from 168 countries globally (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025). At continental level, Zambia ranks 38th in Africa in terms of women’s representation in parliament (SADC, 2022). At the Southern African Development Community (SADC) regional level, Zambia ranks 13th out of 16 countries (SADC, 2022). In 2025, women’s political representation in parliament stood at 15% (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2025) far from the Beijing target of 30% and the gender parity target of 50%. Empirical evidence from Zambia suggests that electoral system design plays a critical role in shaping women’s political participation. SADC Member States that employ Proportional Representation electoral systems combined with gender quotas have a higher representation of women in the National Assembly (SADC, 2022).

Zambia’s continued use of the first-past-the-post system, coupled with the absence of legislated gender quotas, has constrained progress. Furthermore, the legal and policy frameworks, including the Gender Equity and Equality Act, have not yet translated into effective strategies or structural reforms, such as electoral system changes or the adoption of gender quotas, that would significantly enhance women’s political participation (SADC, 2022).

As such, Zambia exhibits several factors that hinder women’s political advancement, including a majoritarian electoral system, the absence of electoral gender quotas, and a lack of post-conflict opportunities for new actors, such as women, to contest established power structures (Tripp and Kang, 2008; Stockemer, 2011; Muriaas et al., 2013; Hughes and Tripp 2015, as cited in Wang et al., 2021). Research by Daka et al. (2023) highlights commercialisation of politics as a major impediment, with women often excluded from being adopted as candidates due to limited financial resources in favour of male candidates with greater financial resources. This exclusion reinforces gender disparities in political access and undermines the effectiveness of constitutional provisions such as Article 9 and Article 45, which mandate gender equity in leadership and electoral representation.

Political party practises also remain a critical bottleneck. A study on party-level adoption trends found that despite public commitments to gender inclusion, major parties failed to meet internal targets for female candidate selection in the 2016 and 2021 elections (Daka et al., 2023). The inadequacy of internal affirmative action mechanisms and the persistence of gender stereotypes within party structures continue to limit women’s visibility and viability as political contenders.

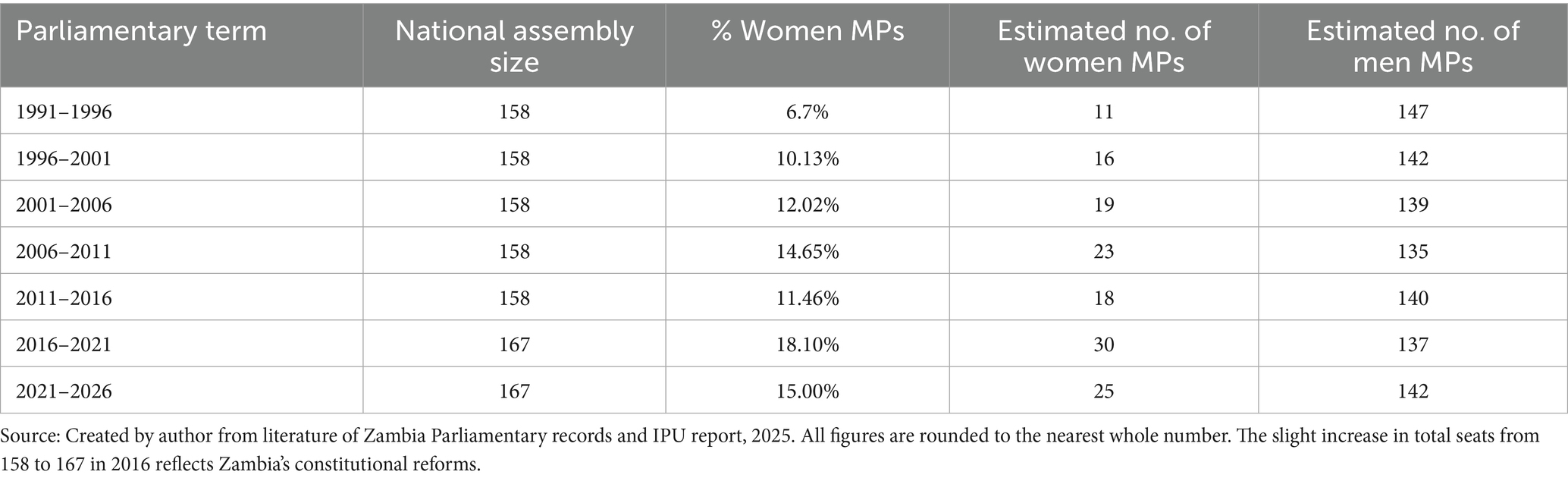

The highest representation of women in parliament was achieved during the 2016–2021 term when women’s representation rose to 18.1% from 12.6% during the 2011–2016 national assembly (National Assembly of Zambia, 2017) as reflected in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Parliamentary terms and percentage of women MPs, Zambia. Source: Created by author from literature of Zambia Parliamentary records and IPU report, 2025.

Figure 3 illustrates the trajectory of women’s representation in Zambia’s National Assembly from 1991 to 2025, revealing a generally upward trend. Beginning at 6.7% in the 7th Parliament (1991–1996), the proportion of women MPs rose incrementally across successive terms, peaking at 18.1% in the 12th Parliament (2016–2021) following constitutional reforms that expanded the number of seats to 167. However, the subsequent decline to 15% in the 13th Parliament (2021–2026) signals persistent structural and political barriers to gender parity. Despite modest gains, the data underscores the need for more robust mechanisms, such as gender quotas, inclusive party nomination processes, and targeted capacity-building, to sustain and accelerate progress towards equitable representation (Table 4).

Several measures have been put in place to promote women’s political participation in Zambia. Article 9 of the Zambian Constitution mandates the government to promote gender balance and equity in leadership and decision-making positions, whilst Article 45 requires the electoral system to ensure gender equity in representation and participation in governance. In 2015, the enactment of the Gender Equity and Equality Act marked a significant step towards domesticating key International Frameworks on gender equality. Notably, section 20 of the Act mandates affirmative action to accelerate the equal representation of women in politics and decision-making positions. Despite this enabling legal and policy environment, women’s political participation remains way below the 30% threshold stipulated in the BDPfA and way below regional and global averages. This underrepresentation limits the country’s potential for inclusive governance and robust development.

Whilst empirical evidence directly linking women parliamentarians to development outcomes remains limited, several country-specific sources offer insight into their legislative agency, strategic positioning, and influence on governance reforms. One notable example of institutional agency and strategic positioning is the Zambian Women Parliamentarians’ Caucus (ZWPC), which has emerged as a key platform for collective advocacy. According to the Southern and Eastern African Regional Centre for Women’s Law (2023) report, the Caucus has actively engaged in legislative processes and sought formal recognition as a Standing Committee, a move endorsed by Speaker Nelly Mutti in her 2023 parliamentary address. The Speaker further reiterated this commitment by calling for a renewed gender agenda among female parliamentarians to strengthen women’s collective advocacy and leadership visibility within the legislature (National Assembly of Zambia, 2023). This institutional positioning signals a shift from symbolic inclusion towards structured influence within parliamentary governance.

In terms of policy influence and legislative engagement, women MPs have played a visible role in shaping gender-responsive legislation. The Zambia Law Development Commission’s publication The Future is Female highlights the strategic appointments of women to leadership positions, including the Vice Presidency and Speakership, as milestones in advancing gender parity (Zambia Law Development Commission, 2023). These appointments have catalysed discussions on a gender parity bill and broader reforms to electoral and nomination systems.

With regard to participation in policy formulation and oversight, the Policy Monitoring and Research Centre (PMRC) report (Policy Monitoring and Research Centre, 2020) on women’s involvement underscores the distinction between nominal representation and substantive influence. The report indicates ath women MPs have the potential to contribute meaningfully to oversight functions, particularly in sectors such as education, health, and community development.

At the level of local governance and development linkages, women’s participation in Community Resource Boards (CRBs) demonstrates how elected female leaders influence natural resource governance and contribute to local development outcomes (Malasha, 2020). These case studies provide empirical grounding for the argument that women’s political participation extends beyond legislative chambers into community-level decision-making, reinforcing the broader significance of inclusive representation.

Whilst Zambia has made commendable strides in establishing a legal and institutional framework for gender equity, persistent gaps in representation and influence underscore the need for deeper integration of women’s voices in governance. Strengthening empirical evidence and showcasing local impact remain essential to advancing the commitments of Beijing+30 and fostering inclusive development.

4.3 Women’s contribution to development through political participation

There is growing evidence showing the positive impact of women’s political participation on development. Most scholars agree that one of the main forces behind economic advancement is the empowerment of females (Lagerlöf, 2003; Kabeer and Natali, 2013; Agénor and Canuto, 2015, as cited in Mirziyoyeva and Salahodjaev, 2023). Gender equality represents a strategic economic advantage, as it can increase economic efficiency and positively influence various developmental outcomes (World Bank, 2012). Mutume (2004) revealed that women’s political participation results in increased income, savings and investments not only for their families but also to the country’s economic growth (cited in Konte and Tirivayi, 2020).

Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras (2014, as cited in Baskaran et al., 2024) assert that countries with higher levels of women’s participation in politics tend to experience more stable economic growth, improved service delivery, and stronger institutional frameworks. Women’s political involvement is linked to more inclusive policies that prioritise health, education, and infrastructure, sectors essential for human development (Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras, 2014, as cited in Baskaran et al., 2024). The evidence indicates that female legislators are less prone than their male counterparts to misuse their positions for personal financial benefit, as lower levels of corruption are associated with enhanced economic growth (Dollar et al., 2001; Swamy et al., 2001; Mauro, 1995; Prakash et al., 2014; as cited in Baskaran et al., 2024).

Khorsheed (2020) conducted a study which included a selection of countries amongst the world’s top 10 by GDPs, such as the United States, China, Germany, the United Kingdom, India, France, Brazil, and Italy. Results from this study show that increasing the number of women in parliament can significantly contribute to economic growth. Specifically, a 10% increase in women’s parliamentary representation is associated with growth rates of 0.27% in high-income countries, 0.36% in upper-middle-income, 0.22 precent in lower-middle-income, and 0.49% in low-income countries. These findings are consistent with established economic theories and are supported by previous research, including the study by Jayasuira and Burkes (2013, as cited in Khorsheed, 2020).

In another study, results of tests performed using the Hansen J-test and second-order autocorrelation [AR (2)] test show that the coefficient for female parliamentary representation is statistically significant and favourably influences GDP growth implying that an increase in the proportion of women in parliament promotes economic development in Europe and Central Asia (Mirziyoyeva and Salahodjaev, 2023). For instance, a 10% rise in women’s parliament representation results in a 0.92% rise in GDP growth (Mirziyoyeva and Salahodjaev, 2023). The results underscore the need of female empowerment in public service in Europe and Central Asia (ECA) areas and match related worldwide studies (Jayasiriya and Burke, 2013 as cited in Mirziyoyeva and Salahodjaev, 2023).

In 2015, McKinsey estimated that eliminating the gender gap under an optimal scenario may contribute up to $28 trillion to the global yearly GDP by 2025, an amount comparable to the combined economies of the United States and China at that time. If all countries attained gender parity comparable to the top-performing nation in their region, over $12 trillion might be contributed to the global GDP by 2025 (Woetzel et al., 2025). This underscores the significant economic gains that can be realised if gender parity is achieved in parliament thereby making gender parity in parliament not only a social imperative, but a powerful economic strategy as well.

India provides further evidence in studies that contrast the performance of female and male parliamentarians with results showing female led constituencies out perform their male counterparts with a higher economic growth rate of 1.85% clearly showing how women’s political leadership positively impacts economic performance (Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras, 2014, as cited in Baskaran et al., 2024). The India study also shows the propensity of women political leaders to complete projects that are critical for development such as road infrastructure projects, compared to their male counterparts (Baskaran et al., 2024).

Konte and Tirivayi (2020) posit that literature has shown that the gender of parliamentarians determines the type of public goods and services that are provided. This view is supported by Beaman et al. (2006) and Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras (2014) who also state that more female politicians have a propensity to invest in local infrastructure and goods and services such as water and public heath which address concerns not only the concerns of women but the entire population (as cited in Konte and Tirivayi, 2020). In another study in India, Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras (2014) found that female politicians invest more in infrastructure at village level resulting in reduced neonatal deaths; as infant survival rates improve, there are higher chances of them growing up to contribute to human capital development and long-term socio-economic growth in their communities (as cited in Baskaran et al., 2024).

Studies have also shown that when women are empowered political, they are able to contribute economic growth of their countries through increased income at family level, savings, and investments thereby contributing to national economic prosperity (Mutume, 2004, as cited in Konte and Tirivayi, 2020). Another conducted in India found that politically active women improve access to safe and clean drinking water relative to men (Beaman et al., 2006, as cited in Konte and Tirivayi, 2020).

A study by Chattopadhyay and Duflo (2001) identified a correlation between increased women’s representation in leadership and improvements in the quality of public health services. Gender equality can increase other development results and boost economic efficiency (World Bank, 2012). The United Nations (2015) emphasises that sustainable development cannot be achieved without respecting human rights and ensuring access to quality education and health for all. Women’s participation also leads to a reduction in the gender gap in primary school and improved immunisation rates (Beaman et al., 2006 cited in Konte and Tirivayi, 2020). Education enhances human capital, which leads to economic development (World Bank, 2018). This view is reinforced by Bah (2023), whose research examined economic performance across 89 countries from 2002 to 2020 which found a positive correlation between education and economic growth by means of the OLS technique.

In an analysis of 50 countries with available data from 1997 to 2016, Konte and Tirivayi (2020) makes an interesting empirical analysis which indicates that regions within countries where women occupy a greater percentage of national assembly seats tend to exhibit lower fertility rates, higher ages at first birth, reduced incidence of early marriage, and increased access to electricity. Evidence increasingly suggests a correlation between elevated unintended pregnancy rates and diminished human development scores, alongside heightened health-related expenditures. A study by the World Bank indicates that the lifetime opportunity costs associated with adolescent pregnancy vary significantly, ranging from 1% of annual GDP in China to 30% in Uganda (Chaaban and Cunningham, 2011).

In addition, Konte and Tirivayi (2020) asserts that regions with a high percentage of women in parliament have more people with access to electricity. Mavisakalyan and Tarverdi (2019) express a similar that women’s participation in legislative bodies results in more attention to issues such as renewable energy, conservation efforts, and environmental justice (cited in Kandemir et al., 2024). The importance of increased women’s political participation resulting in improved institutional quality and good governance was pointed out by Grown et al. (2005), as this contributes to stronger systems for achieving development.

Further research suggests that gender balance in the political sphere promotes gender balance in the work force. This represents tremendous economic potential, as evidence shows that gender equality in the workforce would lead to a doubling in global GDP growth by 2025 (Woetzel et al., 2025) and evidence also shows that countries with high engagement of women in public life experience lower levels of inequality (DiLanzo, 2019). More gender equality also increases other development results, including economic efficiency. Including women in politics also allows institutions to be more democratic, as there is a better representation of the population (Revenga and Shetty, 2012).

This research analyses the influence of political parties on the improvement of women’s representation within the Zambian Parliament. The text underscores that, despite Zambia’s commitment to gender equality, women’s political participation is limited by factors including political party dynamics, cultural barriers, and insufficient affirmative action. The study highlights that the insufficient representation of women in political decision-making hinders the nation’s capacity to attain sustainable development, especially in domains such as poverty alleviation, healthcare, and gender equality.

4.4 Barriers to women’s political participation

Women’s political participation is a fundamental human right and a birthright and therefore protecting and promoting them is a primary responsibility of governments as outlined in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995). International and regional frameworks highlight the importance of ensuring that the human rights of women are fully recognised and effectively protected, applied, implemented and enforced in national law as well as well as in national practise, to enable women enjoy them otherwise they will exist in name only. The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995) also highlights that there is often a gap between having rights and actually enjoying them and this happens because many governments do not fully commit to protecting these rights or educating people, both women and men, about them, compounded by not proper systems to report or address violations, and when there aren’t enough resources to support these efforts at both national and international levels. State parties have signed to commitments to promote women’s political participation but still, barriers exist. In Zambia, for instance, the absence of constitutionally mandated gender quotas in the legal and policy framework, as well as the lack of obligations on political parties or electoral bodies to promote gender parity, perpetuates a political culture that hinders women’s political participation. The Democracy Works Foundation and Zambia National Women’s Lobby (2021) contends that Zambia’s failure to meet the SADC and AU 50–50 gender parity in parliament and other governance institutions is attributable to weak enforcement mechanisms and institutional implementation capacities as well as poor resourcing for gender equity and equality interventions.

Women’s political participation continues to be hindered by structural and capacity gaps (Abiola, 2019). Structural barriers are due to discriminatory laws, policies, institutions and processes which prevent women’s effective participation (Abiola, 2019). Culture significantly contributes to gender inequality and perpetuates stereotypes against women (Ojukwu and Ibekwe, 2020, as cited in Ilodigwe and Uzoh, 2024). Akpabot (1975) claims that through its common ideas, feelings, and beliefs, culture defines the particular character of a society (as cited in Ilodigwe and Uzoh, 2024). Amongst the cultural ideological factors that affect women’s political participation is patriarchy system where gender inequality is determined by the uneven access to political governance (Pateman, 1988, as cited in Olayinka, 2021). Patriarchy, which is deeply rooted in gender stereotypes and power inequalities that support traditional beliefs and practises mainly assigning women to household responsibilities, restricts their participation in public and political arenas and this is highly prevalent in most African nations (Gender Links, 2022).

Women also face challenges such as gender-based violence in political spaces, which discourages many from seeking or holding office. According to Adolfo et al. (2017), political violence against women is a global issue, with cases reported in countries such as Mexico, Australia, Kenya, India, and the United States (as cited in Chisanga et al., 2024). For example, during Afghanistan’s 2010 elections, 90% of threats against candidates were directed at women and in Peru whilst a study by the Jurado Nacional de Elecciones revealed that almost half of the elected women in 2011 and over a quarter of female candidates in the 2014 regional and local elections faced violence or harassment (Chisanga et al., 2024). In another study, data from the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) in countries like Bangladesh, Burundi, Guinea, Guyana, Nepal, and Timor-Leste also showed that women in politics were four times more likely to be targeted by political violence than their male counterparts (Adolfo et al., 2017, as cited in Chisanga et al., 2024). Between 2011 and 2021, Zambia experienced an increase in violence against women in politics, including incidents where female politicians were stripped, assaulted, and harassed, raising serious concern amongst stakeholders (Carter Center, 2016; Carter Center, 2021, as cited in Chisanga et al., 2024).

Capacity barriers faced by women include low educational attainment, inadequate resources to engage amongst others (Abiola, 2019). Evidence from a study by the Zambia National Women’s Financial constraints, limited access to political networks, and entrenched gender stereotypes are amongst the key barriers to women’s participation in politics (Democracy Works Foundation and Zambia National Women’s Lobby, 2021). Since politics has now become commercialised, colossal amounts of money are required for participation thereby limiting women’s participation due to their lack of access to and ownership over productive resources (Bekele, 2019). Women often lack social capital because they are often not head of communities, tribes or kinship groups, resulting in the absence of constituency base for them and means of political participation such as political skills, economic resources, education, training and access to information (Bari, 2005 cited in Bekele, 2019). The representation of women in political leadership such as parliament remains low due to various factors such as the commercialisation of politics, electoral violence against women, societal norms as the low economic, financial and social status of women (Democracy Works Foundation and Zambia National Women’s Lobby, 2021).

A substantial body of literature highlights the persistent barriers to women’s political participation, pointing to a combination of structural, cultural, and individual-level factors. Studies have identified that responsibilities within the family, limited access to institutional and financial support, and entrenched sociocultural perceptions regarding gender roles significantly hinder women’s entry and sustained engagement in politics (Phiri, 2017; Ballington, 2008; Lawless and Fox, 2012; Sampa, 2010, as cited in Daka et al., 2023). In addition, a perceived lack of political ambition amongst female candidates is frequently cited as a contributing factor to their underrepresentation. These findings collectively underscore the urgent need for comprehensive structural reforms and targeted strategies that promote a more inclusive and supportive political environment for women.

Women’s political participation is therefore overall limited by a complex interaction of structural and capacity-related constraints firmly ingrained in legal, cultural, institutional, and socioeconomic systems. Globally and nationally committed to gender equality, discriminating policies, cultural ideologies, political violence, and resource restrictions nevertheless marginalise women from full political participation. Dealing with these complex problems calls for not only legislative and regulatory change but also transforming action to destroy dismantle harmful norms, increase institutional responsibility, and improve women’s access to political, social, and financial resources. Inclusive and fair political representation will remain unattainable without intentional, consistent efforts.

4.5 Study limitations

Although this paper offers insightful analysis of the worldwide and Zambian settings of women’s political involvement following the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, it is not without limits. First of all, the study is predicated on secondary data and a literature analysis, so restricting the capacity to establish clear causal relationships between women’s political engagement and development results. Second, there is still a clear discrepancy in country-specific statistics for Zambia even whilst worldwide data progressively supports the developmental advantages of women’s political participation. Particularly there is no empirical data proving the specific contributions of Zambian women legislators to development outcomes such as budgetary priorities, infrastructure building, education, and social investment. This data gap limited the capacity of the study to properly evaluate the degree and type of influence of women parliamentarians on national development. Future studies should give priority to collection and analysis of gender disaggregated national data on the contributions of women in political leadership in order to support evidence-based advocacy, policy design, and inclusive governance.

5 Conclusion

Globally, women’s right to participate in politics is affirmed in various international agreements, including the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPfA). Whilst many countries have made strides in domesticating these commitments into national laws, leading to notable gains in women’s political participation, implementation has been slow and uneven. Employing a qualitative desk review triangulated with descriptive statistics, this study has examined global and Zambian progress on women’s parliamentary participation over the past three decades. The findings confirm that whilst representation has more than doubled globally since 1995, from 11.3 to 27.2%, progress remains slow and uneven, with Zambia still below both regional and global averages at 15% in 2025. Anchored in Feminist Theory, the study demonstrates that women’s underrepresentation is not merely a numerical shortfall but the result of entrenched structural barriers such as patriarchal norms, financial exclusion, male-dominated political parties, and the continued use of first-past-the-post electoral systems in countries such as Zambia. These barriers require urgent attention and contextualised measures at all levels.

Evidence shows that when women attain meaningful representation, they shape policy priorities in health, education, social protection, and economic growth, thereby contributing to inclusive and sustainable development. Their participation in parliament is thus a pivotal driver of good governance and equitable growth, making it imperative that women, who constitute the majority in most countries, are not left out or underrepresented in policymaking organs such as parliament. By bridging the gap between descriptive representation and substantive influence, the study contributes new insights to the literature, particularly in the Zambian context where empirical linkages between women’s leadership and development outcomes remain underexplored. It underscores that achieving gender parity is both a democratic imperative and a developmental necessity: without it, societies risk undermining inclusive governance, economic prosperity, and social cohesion.

5.1 Policy implications

The study underscores the need for strengthened gender-responsive legislative frameworks and the enforcement of affirmative action policies to increase women’s representation in parliament. It calls for the review and implementation of gender responsive political party regulations, electoral laws, and national gender policies to eliminate structural and systemic barriers to women’s political participation.

5.2 Practical implications

Practically, the study underscores the need for targeted investments in leadership training, mentorship, and financial support for women candidates. It also emphasises the importance of public awareness campaigns to challenge detrimental gender norms and highlight the critical role of women’s leadership in advancing equitable and inclusive development in Zambia.

5.3 Recommendations for enhancing women’s political participation

To ensure that Zambia and in Zambia, commitments under BDPfA are met, it is imperative to address the barriers to women’s political participation and create a more inclusive political environment. Several recommendations emerge from the literature:

• Adopt gender responsive electoral laws and policies: Countries like Zambia that rely on the first past the post electoral system for parliamentary elections should consider undertaking electoral reforms to adopt gender responsive electoral systems such as the proportional representation or mixed member electoral systems. These have worked in increasing women’s representation in parliament for those countries that have adopted these electoral systems. Reforms should also target political party constitutions and manifestos to ensure that they embed equity and gender quotas.

• Introduce Gender Quotas: Zambia and other countries that are not implementing gender quotas for women’s political participation in parliament should introduce this affirmative action measure. Research indicates that gender quotas can be effective in increasing women’s representation in politics. Countries that have implemented gender quotas have seen significant increases in female political participation, which has led to more inclusive and development-oriented policies (Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras, 2014 cited in Baskaran et al., 2024). Zambia and other countries that currently do not have gender quotas could benefit from adopting these to enhance women’s political participation in parliament and other decision-making levels. Gender Quotas should start from political parties who sponsor candidates for elections.

• Promote Capacity and Networking Opportunities: Expanding women’s access to political training and leadership development programmes would help address the knowledge gap that many women face in navigating political processes (Democracy Works Foundation and Zambia National Women’s Lobby, 2021). Additionally, creating platforms for women to build political networks would facilitate their candidacies and political campaigns.

• Address Societal norms hindering women’s political participation: A multi-pronged approach will be required to address societal norms. This should include public awareness campaigns promoting women’s political participation and challenging gender stereotypes; including aspects of gender equality in the school curriculum to foster gender equality tenants amongst children from an early age, engaging men and boys as allies and community leaders including traditional and religious leaders to support women’s political participation will shift societal attitudes and create an enabling environment where women’s political participation is seen as both necessary and valuable.

• Providing targeted support to female candidates: Providing targeted training, mentorship and financial support to female candidates can help to level the playing field and empower women to effectively participate in the political sphere.

• Address Electoral and other forms of GBV: Addressing electoral and other forms of GBV is critical for creating a safe space for women to engage in political leadership. Research by the Electoral Commission of Zambia (2021) suggests that anti-violence policies targeting female candidates could help mitigate the challenges faced by women in politics.

Author contributions

PN: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Validation, Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI tools, such as Chat GPT and Quill Bot, were utilised exclusively to enhance grammar and coherence. All AI-assisted outputs were thoroughly reviewed and edited by the author, who assumes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abiola, I. A. (2019). Women’s political participation and grassroots democratic sustainability in Osun state, Nigeria (2010-2015). J. Interdiscip. Fem. Thought 11:18. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/jift/vol11/iss1/3

ACE Electoral Knowledge Network. (2022). Gender and elections. Retrieved from https://aceproject.org

Bah, I. A. (2023). The relationship between education and economic growth: a cross-country analysis. RSD 12:e19312540522. doi: 10.33448/rsd-v12i5.40522

Ballington, J., and Kahane, M. (2015). Women in parliament: 20 years in review. New York, USA: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Baskaran, T., Bhalotra, S., Min, B., and Uppal, Y. (2024). Women legislation and economic performance. J. Econ. Growth 29, 151–214. doi: 10.1007/s10887-023-09236-6

Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPfA). (1995). Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action: The fourth world conference on women. New York, NY: United Nations.

Bekele, M. L. (2019). Political empowerment of women for sustainable development in Ethiopia. J. Cult. Soc. Dev. 46, 1–5. doi: 10.7176/JCSD/46-01

Belliard, C.M., (2021). World Conference on Women (1997–1995). Presented at the Women’s History Network Conference 2021, HAL (multi-disciplinary open access archive), Online, United Kingdom; p. 1.

Chaaban, J., and Cunningham, W. (2011). Measuring the economic gain of investing in girls: the girl effect dividend, World Bank policy research working paper no. 5753. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Chattopadhyay, R., and Duflo, E., (2001). Women as policy makers: evidence from a India wide randomised policy experiment. Massachusetts, USA: Cambridge.

Chisanga, A. S. J., Matole, A., Kawila, E. L., and Mulubale, S. (2024). Exploring forms of political violence against women and their effect on women’s political participation in Matero constituency of Lusaka district, Zambia. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. VIII, 730–739. doi: 10.51244/IJRSI.2024.1103051

Dahlerup, D. (2006). Women, quotas and politics, Routledge research in comparative politics. London: Routledge.

Daka, H., Phiri, C., Kanyamuna, V., Mudando, J., and Brill, P. (2023). Exploring the role of political parties in the enhancement of women representation in parliament, Zambia: a phenomenological perspective. Eur. J. Dev. Stud. 3, 21–31. doi: 10.24018/ejdevelop.2023.3.6.310

Democracy Works Foundation and Zambia National Women’s Lobby (2021). Zambia’s Women’s manifesto: Towards a better Zambia for all. Lusaka, Zambia: Democracy Works Foundation and Zambia National Women’s Lobby.

Dialo, A. O., and Sarumi, R. F. (2025). Gender equality and Women political participation for sustainable development in Nigeria fourth republic: issues and challenges. Covenant Univ. J. Polit. Int. Aff. Spec. Issue Leadersh. Dev. https://journals.covenantuniversity.edu.ng/index.php/cujpia/article/view/5004

DiLanzo, T., (2019). Strengthen Women’s political participation and decision-making power. Massachusetts, USA: Cambridge.

Electoral Commission of Zambia. (2021). 2021 general election report. Lusaka, Zambia: Electoral Commission of Zambia.

Endale, A. H. (2012). Factors that affect Women participation in leadership and decision-making position. Asian J. Humanity Art Lit. 1:20. doi: 10.18034/ajhal.v1i2.287

Geisler, G. (1995). Troubled sisterhood: Women and politics in southern Africa. Case studies from Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana. London: Methuen.

Goetz, A. M., and Hassim, S. (Eds.) (2003). No shortcuts to power: African Women in politics and policy making. London: Zed Books.

Greavs, G., and Varsha, N. (2025). The four world conferences on Women: milestones in global gender equality. Barbados: United Nations.

Grown, C., Gupta, G. R., and Kes, A. (2005). Taking action: achieving gender equality and empowering women : United Nations.

Ilodigwe, A. O., and Uzoh, B. C. (2024). An appraisal on the impact of gender inequality and stereotypes on female participation in politics in Anambra state. Afr. J. Soc. Behav. Sci. 14:12. https://journals.aphriapub.com/index.php/AJSBS/article/view/2585

Inter-Parliamentary Union, (2025). Women in Parliament: 1995–2025. Geneva, Switzerland: Inter-Parliament: 1995–2025.

Kandemir, A. S., Lone, R. R., and Simsek, R. (2024). Women in parliaments and environmentally friendly fiscal policies: a global analysis. Sustainability 16:7669. doi: 10.3390/su16177669

Kassa, S. (2015). Challenges and opportunities of Women political participation in Ethiopia. J. Glob. Econ. 3:7. doi: 10.4172/2375-4389.1000162

Khorsheed, E. (2020). The impact of women parliamentarians on economic growth: modelling and statistical analysis of empirical global data. Int. J. Stat. Probab. 9:23. doi: 10.5539/ijsp.v9n3p23

Konte, M., and Tirivayi, N. (Eds.) (2020). Women and sustainable human development: Empowering Women in Africa, Gender Development and Social Change. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Krook, M. L. (2010). Women’s representation in parliament: a qualitative comparative analysis. Polit. Stud. 58, 886–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00833.x

Lefley, F., and Janeček, V. (2023). Board gender diversity, quotas and critical mass theory. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 29, 139–151. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-2023-0010

Lorber, J. (2012). Gender inequality: Feminist theories and politics (5th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mackay, F., Kenny, M., and Chappell, L. (2010). New institutionalism through a gender lens: towards a feminist institutionalism? Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 31, 573–588. doi: 10.1177/0192512110388788

Malasha, P. (2020). “Increasing Women’s participation in community resources boards in Zambia: outcomes and lessons learned from the election process” in Integrated land and resource governance task order under the strengthening tenure and resource rights II (STARR II) IDIQ (Washington, DC: USAID).

McCann, C. R., and Kim, S.-K. (Eds.) (2017). Feminist theory reader: Local and global perspectives. 4th Edn. New York: Routledge.

Mirziyoyeva, Z., and Salahodjaev, R. (2023). Does representation of women in parliament promote economic growth? Considering evidence from Europe and Central Asia. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1120287. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1120287

National Assembly of Zambia (2017). Parliamentary debates: the launch of the public financial management handbook. Lusaka, Zambia: National Assembly of Zambia.

National Assembly of Zambia (2023). Speaker Mutti calls for gender agenda push among female parliamentarians. Lusaka: National Assembly of Zambia.

National Gender Policy. (2014). Revised national gender policy. Lusaka, Zambia: Cabinet Office, Gender Division.

Ojo, O. (2022). Overview of Women and political participation in Nigeria (2015-2022). Dyn. Polit. Democr. 1:11. doi: 10.35912/DPD.v1531

Olayinka, O. F. (2021). Women’s right to active participation in political governance: the issues, prospects and challenges in the post-Beijing Nigeria. Int. J. Hum. Rights Const. Stud. 8:21. doi: 10.1504/IJHRCS.2021.117971

Orisadare, M. A. (2019). An assessment of the role of women group in women political participation, and economic development in Nigeria. Front. Sociol. 4:52. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00052