- Department of Global Studies, KFUPM Business School, King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia

This article is a conceptual intervention in the debate on the so-called democratic backsliding in Africa, and challenges the dominant narratives for overlooking more fundamental structural questions. Rather than mere erosion of democratic gains, I contend that recurring crises of democratization are manifestations of an enduring Structural Conflict (SC) in the political culture of African countries. SC refers to the dissonance between colonial political structures and indigenous popular agency. To capture this, I introduce two types of political agency—Dominant Majority Demo-Agency (DMD+), where citizens exercise genuine control, and Dominant Minority Demo-Agency (DMD−), where elites monopolize power—as novel tools for diagnosing Africa’s hollow democratic transitions. Building on Frantz Fanon’s analysis of coloniality, I theorize internalized structural inferiority as the mechanism through which many African states valorize external models and devalue indigenous ones. It is this internalization, I argue, that generates democratic self-sabotage: the embrace of alien structures that appear democratic while disabling majority agency and manifesting in coups, violent extremism, electoral disillusionment, and conflict. While recognizing Africa’s diversity, I propose Structural Blackening as a corrective: the deliberate reconstitution of political systems with indigenous agency, epistemologies, and aspirations. Structural Blackening offers a path toward authentic democratic emancipation rooted in epistemic and structural rebellion against coloniality.

Introduction

Many African countries witnessed significant liberal democratic openings in the early 1990s. In the years that followed, there appeared to be a preference for liberal democratic forms of governance, characterized by deepened political accountability and pluralism, in contrast to the preference for authoritarianism, elitist one-party rule, and military rule in previous decades (Gyimah-Boadi, 1996). Today, however, democracy scholars argue that African countries stand at risk of a gradual movement away from democratic consolidation towards authoritarianism (Gyimah-Boadi, 2015; Diamond, 2008). They argue that ‘a third wave of autocratization is indeed unfolding’ (Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019) to counter the so-called “third wave” of democratization (Huntington, 1993), and that ‘the democratic gains won in the period after 1990 are now eroding’ (Rakner, 2019). Their reasons include the following: the level of support for military governments in Africa has doubled, from 11.6% in 2000 to 22.3% in 2022, while in 26 out of the 37 countries surveyed, support for military dictatorships increased (García-Rivero, 2022), with low level of trust in political institutions and satisfaction with democratic performance (Logan et al., 2021; Afrobarometer (2024, 2025). Indeed, in the last 4 years alone, Africa has recorded seven coup d’états and several attempted ones.

Because much of Africa is expected to have undergone significant democratization, many analysts insist that the above developments are evidence of democratic “backsliding,” resurging authoritarianism, returning coups, and democracy in crisis (Ero and Mutiga, 2023; Gyimah-Boadi, 2021; Maphaka et al., 2024; Opalo, 2024). Departing from the point of accusation that these dominant narratives about coups and authoritarianism in Africa ignore more fundamental questions, this article reflects on and critically examines the liberal democratic project in Africa and, through that examination, makes claims about the challenges of democratic consolidation. Democratic consolidation is defined as when democracy becomes ‘so broadly and profoundly legitimate among its citizens that it is very unlikely to break down’ (Diamond, 1994).

Admittedly, democratic consolidation is not an event but a process, and there are reasons to be optimistic about democratization in many African countries. Thus, it may indeed be premature to ‘proclaim the “end of democracy”’ (Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019), and, as some insist (Cheeseman, 2015; Freedom House, 2024), there are ‘success stories that defy the odds.’ A small but durable cluster of emerging liberal democracies in Sub-Saharan Africa includes Cabo Verde, Mauritius, Ghana, Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, with recent improvers such as The Gambia (since 2016) and Zambia (since 2021) (Freedom House, 2024; International IDEA, 2023). Positive exemplars also suggest that political will plus institutions can shift trajectories. The Gambia’s 2016 transition and Zambia’s 2021 alternation improved pluralism, while Kenya (in 2017) and Malawi (in 2019–20) highlight judicial independence as a democratic backstop (International IDEA, 2023; Chatham House, 2020). Such cases show progress where elites accept adverse rulings and reform incentives align with majority agency.

Nevertheless, given the scale of the so-called democratic backsliding, it appears that instead of arguing that authoritarianism and militarism are “returning” in Africa, we should be wondering if their underlying factors left in the first place. In any case, it would be helpful to ask some questions: are the challenges of democratization in some African countries the result of fundamental structural problems? If so, what are some of these problems, and how could they be surmounted? In answering these questions, it is worth noting that for many African countries, there is every reason, over three decades since the liberal democratic opening, to ask whether that mode of governance is, at the very least, failing or has, at worst, failed. This article does not aim to answer that question. Instead, it is a conceptual continuation of the debate initiated 50 years ago by Davidson (1964), who posed the futuristic question, “Which Way Africa?” This question, despite receiving significant academic attention, remains relevant today.

Under neoliberalism, for instance, African leaders were urged to engage with democracy, but what has been the nature of this engagement several decades later? The above questions enable African countries to look inward for answers, considering Amin (2014) assertion that accepting the neoliberal ideal as the sine qua non for achieving human development prevents ‘real alternatives’. Interrogating the liberal democratic project against the backdrop of rising coup d’états, authoritarianism, and erosion of civil rights serves the need to rethink politics in Africa at a critical historical juncture. To do so, I bring Fanonian thought—in his Black Skin, White Mask (2017 [1952])—to examine the challenges of democratization and governance in parts of Africa. This article contents that recurring crises of democratic governance are manifestations of an enduring Structural Conflict (SC) in the political culture of ex-colonial African societies, not mere democratic backsliding. SC is a dissonance between colonial political structures and indigenous popular agency.

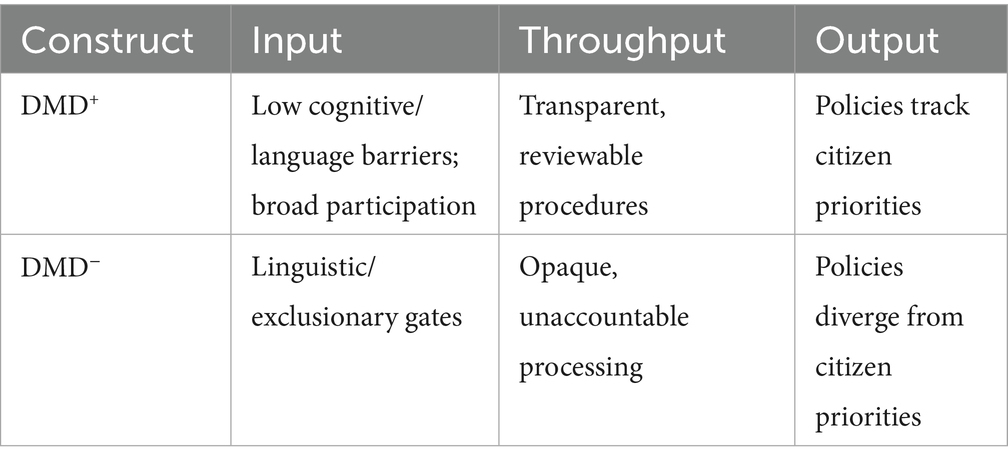

This argument stands on several novel and derived concepts whose full definitions are presented later in Table 1. Here I outline their theoretical lineage and original contributions that anchor the framework. SC is an original framework proposed here, grounded in Mamdani’s (1996) bifurcated state, Ekeh’s (1975) two publics, and Ake’s (1996) analysis of democracy’s structural preconditions. These scholars diagnose the colonial legacy as a source of fractured legitimacy. However, SC reframes this as an explicit conflict between imported structures and indigenous agency, and a structural inheritance problem that fuels democratic backsliding. Dominant Majority Demo-Agency (DMD+) and Dominant Minority Demo-Agency (DMD−) are also new terms. Inspired by Dahl’s (2000) ideal of “government by the people” and Ake’s (1996) critique of Africa’s democratic façades, these novel concepts focus on who actually steers political outcomes. This binary captures an “agency gap” that terms like “hybrid regime” only imply: in DMD+, the majority rules in practice; in DMD−, they have only their say, not their way. Fanon (2001) critique of superficial decolonization informs the reading of DMD− as a democracy where a Westernized minority governs the formerly colonized majority.

Internalized Structural Inferiority draws from Fanon’s analysis of internalized coloniality, extended here to the structural level, while Democratic Self-Sabotage explains how adopting ill-fitting Western models undermines democratic consolidation. Finally, Structural Blackening is a novel term for decolonizing political structures. It draws from Ngũgĩ’s (1986) call to “decolonize the mind” and Nkrumah’s (1964) vision of authentically African democracy. It packages these aspirations into a prescriptive program aimed at achieving Positive Structural Harmony—the alignment of political structures with the agency, values, and aspirations of the majority, away from Negative Structural Harmony, which is the alignment of political structures with the elite minority agency. Together, these concepts offer a diagnostic vocabulary linking colonial legacies to present-day agency deficits, and a remedy rooted in structural realignment toward majority rule.

I make the above argument in the following steps: the next section enunciates SC and its constituent parts further, and sets up SC as a continuation of existing research on the nature of politics in African societies. Another section then discusses the background to the conception of SC, particularly Fanonian thought in Black Skin, White Mask (2017 [1952]). This section discusses the structure and agency debate and defines the article’s usage of Black and White. A subsequent section focuses on defining democracy (and a lack of it) in the African context. Noting that there are many types of democracy, including during pre-colonial Africa, democracy here refers to liberal democracy unless otherwise qualified. Relatedly, the use of Western definitions of democracy in this article is an act of reduction ad absurdum of the liberal democratic ideal. A different section discusses one example of the Whiteness of political structures, the use of colonial language for politics and educational instruction, and how this Whiteness detracts from democratic consolidation and development politics. A final section then returns to Fanon. It presents ongoing crises of democratization, coups, conflicts, extremist militancy and insurgencies as the outcomes of internalizing structural inferiority and structural self-sabotage. A conclusion suggests ways of reducing and eventually removing SC in the democratic culture of ex-colonized African societies.

Structural conflict, DMD+, DMD–, and coloniality

The concept of Structural Conflict (SC) proposed in this article captures the enduring dissonance between inherited political structures and indigenous popular agency within African states. While the global discourse on democratization has often emphasized institutional design, electoral processes, and governance reforms, it has largely overlooked the deeper epistemological and ontological fractures that separate African citizens from the political systems ostensibly created to serve them (Amin, 2014; Mamdani, 1996). SC refers to the fundamental mismatch between political structures (that are rooted in colonial legacies and remain outward-looking, elitist, and Western-oriented), and the lived political agency of African populations, which remains predominantly inward-looking, indigenous, and communitarian.

This conflict is not simply ideological. It manifests materially in how African citizens experience exclusion from decision-making processes, perceive political institutions as alien, and engage in contestation, protest, and withdrawal cycles. The structures of governance, including language, law, and institutional design, largely continue to reflect colonial templates, which neither resonate with nor adequately represent the socio-political aspirations of the majority (Ekeh, 1975; Fanon, 2008). In effect, African citizens often operate within a political architecture that demands conformity to external norms and languages while marginalizing indigenous forms of political engagement, participation, and representation. SC thus prevents the realization of meaningful democracy because it inhibits the necessary structural harmony between political institutions and popular agency. Whereas democratic consolidation requires a close fit between the spirit of public institutions and the collective reasoning of the citizenry (Feit, 1968), the persistent coloniality of political structures ensures that the African state remains a domain primarily accessible to a small elite, leaving the majority structurally disenfranchised. The governance, legitimacy, and citizen alienation crises witnessed across Africa today are not temporary dysfunctions to be corrected through procedural reforms. Instead, they are enduring symptoms of a deep and unresolved structural conflict at the heart of African political life.

At the heart of SC lies the imbalance between two contrasting forms of political agency, namely Dominant Majority Demo-Agency (DMD+) and Dominant Minority Demo-Agency (DMD−). The DMD+/DMD− dyad is an original concept developed here to provide a framework for understanding who truly controls democratic processes and outcomes in African states. It integrates Dahl’s procedural benchmarks for democratic responsiveness (polyarchic participation/contestation) Dahl (2008), to theorize how citizens’ democratic agency can be structurally enabled (DMD+) or disabled (DMD−) even under formally electoral regimes. DMD+ refers to a political condition in which the collective agency of the majority of citizens meaningfully shapes the direction, operation, and outcomes of political governance. It represents the normative essence of democracy, wherein the majority exercises political power and is responsive to their needs, aspirations, and lived realities. In the context of this type of political agency, elections, civic participation, and governance mechanisms effectively translate popular will into policy outcomes and leadership accountability (Dahl, 2000; Munck, 2016).

In contrast, DMD− characterizes political systems where elite segment of the population exercises disproportionate influence over governance structures due to their historical and socio-cultural alignment with Eurocentric ethos. This elite class captures political processes to serve its interests, even under the formal guise of democratic procedures. Elections may be regularly held, and political parties may proliferate, but decision-making power remains insulated from popular control, reinforcing patterns of elite domination. The prevalence of DMD− in many African states is a direct consequence of SC. Political structures—being alien in origin and orientation—are naturally more accessible to those whose socialization, education, language, and economic status align with the colonial and postcolonial state apparatus. Meanwhile, the vast majority of citizens, who are embedded in indigenous socio-political ontologies and epistemologies that are marginalized or ignored by the state, find their agency structurally disempowered.

Thus, DMD+ emerges when there is structural harmony between political structures and the agency of the majority, enabling citizens to exercise meaningful control over governance and decision-making processes. In contrast, DMD− arises when political structures are harmonized with elite agency, aspirations and interests, allowing a small minority to monopolize power while marginalizing the broader populace. Where political structures align with the aspirations and participation of the majority, structural harmony fosters legitimacy, inclusion, and stability. Where, however, political structures remain alien to popular agency, through the preservation of colonial logic, languages, and norms, structural conflict persists, thereby producing crises of representation, democratic self-sabotage, and systemic instability. Because of the dominance of DMD–, hence a structural harmony between elites and political structures, the formal adoption of democratic institutions has not led to substantive democratization.

Rather, it has entrenched a system in which elites dominate political life, manipulate electoral processes, co-opt civil society, and perpetuate governance models that systematically exclude the majority. As Ake (1996) observed, African democracy has often amounted to little more than “a façade,” masking deep inequalities in political power and social influence. Understanding the dominance of DMD– over DMD + thus provides a crucial lens through which to interpret Africa’s contemporary political crises. It reveals that elections alone do not equal democracy and that without realigning political structures to empower majority agency, democratic consolidation will remain elusive. Thus, DMD− should not be conflated with the broader categories like “grey zone” façade democracies (Carothers, 2002), electoral authoritarianism (Schedler, 2006), competitive authoritarianism (Levitsky and Way, 2010), and illiberal democracy (Zakaria, 1997). While those typologies emphasize institutional form or electoral competitiveness, DMD− specifically names the condition of an agency gap: where the majority may participate procedurally yet cannot steer outcomes substantively. This diagnosis means that the most consequential sign of democracy deficit is not institutional weakness. Instead, it is the systematic displacement of majority agency by minority dominance.

That said, it must be noted that while SC is the core mechanism, outcomes are mediated by economic structures, external interventions, and ethnic cleavage configurations. Resource rents and weak state capacity can entrench neopatrimonial rule and heighten conflict risk (Fearon and Laitin, 2003). External involvement can internationalize civil wars and reshape incentives for elites (International IDEA, 2023). Institutionalized ethnicity, in turn, conditions coalition-building and the distribution of public goods (Posner, 2005). These variables interact with SC rather than supplant it so that SC may manifest acutely or latently. Secondly, “Africa” is a complex and politically and socioculturally diverse category. It contains countries consistently rated “Free” (e.g., Cabo Verde, Mauritius, Botswana, Ghana) to those that are conflict-affected or coup-prone, while governance trends also diverge across the continent (Freedom House, 2024; Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2023). My claims apply to recurrent structural mechanisms, not to all polities equally. Accordingly, the particular manifestation of structural conflict, whether latent or acute, will be contingent upon diverse sociopolitical and cultural realities.

Despite these caveats, this article’s arguments are important because they continue and contribute to previous scholarship that subjected democratic experience and state formation in Africa to extensive critical scrutiny and consistently emphasizes the deep structural fractures inherited from colonialism.

This previous scholarship shows that African postcolonial states were born not from popular sovereignty but from externally imposed architectures of domination (Mamdani, 1996; Young, 1994; Herbst, 2000; de Walle, 2001). Rather than dismantling the colonial logic of governance, independence movements often merely Africanised them, reproducing political forms fundamentally alien to indigenous agency. Here, Mahmood Mamdani (1996) concept of the bifurcated state remains central. Mamdani shows that colonial rule divided African societies into rural subjects governed through customary mores and urban citizens governed through civil law, a division maintained after independence. Young (1994) similarly pointed to an Africa where arbitrary colonial borders imposed ill-fitting political communities. Accordingly, as Bates (1981) and Herbst (2000), add, African states focused on urban extraction and control struggled to project legitimate authority into rural hinterlands. This exacerbated disjunctures between state and society. To de Walle (2001), this structural weakness entrenched neo-patrimonial governance, where clientelism and informal networks became necessary survival strategies within hollow state institutions.

The moral and social dimensions of this alienation are illuminated by Ekeh’s (1975) influential theory of the ‘two publics’. Ekeh demonstrates how colonialism produced a civic public, associated with the state and treated amorally, and a primordial public, associated with kinship and treated morally. This duality, echoed by Mamdani (1996), fundamentally fractured the foundations of public life, creating contradictory loyalties that inhibit the development of a unified civic culture. In the end, as Ake (1993, 1996) laments, African democracy has been reduced to the superficial transplantation of electoral rituals onto states whose structures and moral orders remain incompatible with liberal norms. To make sense of the chaos, Chabal and Daloz (1999) pointed to for the existence of an instrumentalization of disorder, arguing that African politics is not chaotic but rationally organized around informal norms of patronage, loyalty, and personalism rather than formal institutions.

Global structures of domination also persist. Amin (2014), Joseph (1997), and Grovogui (1996) observe that African states remain trapped within a global capitalist system that constrains economic autonomy and reproduces political dependency. To Joseph (1997), therefore, electoral competition in Africa has often masked persistent authoritarian tendencies maintained primarily for external validation. Accordingly, Grovogui (1996) challenges the assumed universality of Western democratic standards, by exposing how African political systems are judged against Eurocentric criteria that ignore colonial and postcolonial realities. Niang (2018) furthers this line, demonstrating how imported notions of statehood perpetuate crisis by failing to resonate with endogenous African political systems.

The role of civil society has similarly been problematized, with Harbeson et al. (1994) contending that African civil societies are weak, fragmented, and often urban-biased. Even where civil society flourishes, it often replicates elite interests rather than empowering mass agency. Thus, as de Waal (1997) observes, humanitarian interventions can be absorbed into patronage networks, reinforcing, rather than challenging, neo-patrimonial state dynamics. Even non-governmental organizations (NGOs), according to Hearn (2001), frequently become depoliticized service providers accountable to foreign donors rather than domestic constituencies. Accordingly, Wa Mutua (1995) criticizes human rights NGOs for exporting Eurocentric moral standards that are divorced from African historical contexts. At the psycho-social level, Fanon (2001, 2017) remains foundational in revealing how colonialism colonizes not only land but consciousness, producing elites who valorize Western norms and internalize racial and cultural inferiority. More contemporary scholars such as Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2013) and Maldonado-Torres (2007) extends this through the concepts of coloniality of power and coloniality of being. They demonstrate how colonial hierarchies persist epistemically even after formal decolonization and where the very existence of African subjects remains shaped by colonial structures of knowledge and valuation.

Some scholars critique rigidities in these models of explaining socio-economic and politico-cultural realities in African societies (Burton and Jennings, 2007; Finn, 2021). However, an observation that African states remain sites of fractured political subjectivities still holds. As scholars such as Adebanwi (2017), Osaghae (2006), and Rothchild and Chazan (1988) maintain, even where temporary moments of state-society balance emerge, they are precarious, vulnerable to relapse into elite capture and fragmentation. It is worth noting here that the determinant of inclusion within the civic public increasingly correlates with proximity to Whiteness and access to global capital and networks. The more “bourgeois” one becomes, the closer one moves toward political agency, while the majority remain trapped in marginalized spaces of informal governance and symbolic inclusion.

Thus, while existing literature has robustly documented the nature, persistence, and effects of structural bifurcation and elite domination in Africa, this article still adds much to the debate in the context of the so-called democratic backsliding. By reconceptualizing the crisis of democracy in Africa as rooted in the dissonance between colonial structures and indigenous agency, the article reframes the challenge beyond procedural deficits to foundational misalignment. It highlights how formal institutions perform democracy while reproducing exclusion and how civil society, law, and political participation remain spaces of structural alienation. The article proposes Structural Blackening (SB) as a transformative project. SB is a deliberate, pluralistic, context-sensitive reconstitution of political structures to align with indigenous epistemologies, values, and endogenous aspirations. Rather than perfecting inherited colonial forms, SB calls for epistemic rebellion, institutional reconstruction, and democratic imagination grounded in Africa’s histories and futures. This theoretical innovation seeks to move beyond critique to reimagine Africa’s democratic possibilities on sovereign and indigenous terms.

Metaphorising Fanon: agency and structure in “black” and “white”

For clarity, references to “Blackness” and “Whiteness” in this article are symbolic and not phenotypic. Ascribing Blackness to political agency and Whiteness to political structures draws on a metaphorisation of Frantz Fanon’s argument in his book White Skin, Black Masks (2017 [1952]) informed by the Structure-Agency debate. Despite disagreements regarding what determines individual action, scholars agree that structure and agency have a role in determining human and individual behavior. The point of contention concerns the extent or degree of that determination. Therefore, Giddens (1984) theory of Structuration emphasizes the ‘duality of structure’ in which agency and structure work together to determine reality. However, even Giddens conceived human action as the outcome of ‘practices ordered across space and time’ (Giddens, 1984, p. 2). On this score, cognizant of the postcolonial political history of African countries and without discounting the role of human agency, this article gives primacy to the structure in determining democratic and political behaviors in ex-colonial societies. There are several reasons for placing structure above agency.

The first is that the state in Africa, as it is currently run, is a colonial structural imposition, and political independence in the 1950s and 60S did little to put political structures in the hands of citizens. As Mamdani (1996, p. 6) has asserted, political independence in Africa may have deracialized the state but failed to democratize it. This is partly because, as Wa Mutua (1995) argues, the right of self-determination in Africa was not exercised by the victims of colonization but by their oppressors—the elites who dominate the international state system. African leaders, most of whom had been privileged by colonialism, retained colonial structures, political norms, doctrines and principles they had mastered. In the end, according to Ake (2003), the postcolonial state in Africa did not encourage endogenous development strategies. In this sense, the independence celebrated by African countries, being the outcome of the decolonial wave of the 1950s and 60, is only ‘politico-juridical freedom, which is often conflated with freedom for the ordinary peoples of Africa’ (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2012: Abstract). To the people, thus, the state in Africa is inherited and hence imposed (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2012).

Secondly, the ubiquitous presence of the “imported” (Badie, 2000) or imposter state in the lives of citizens continues even after several policies and programmes aimed at hollowing it out. Given the little control citizens have over the doings of the state in many African countries, one can assert that across space and time, the political experience in many African countries has largely defied the logic that human action is the outcome of reflexive relationships between individuals and structures. As the colonial matrices of power work to maintain Africa’s subaltern position in global politics (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2012), at home, everyday citizens have had little control of the postcolonial state in competition with elites. In the end, despite attempts to make the state “Black” at independence and citizens’ struggle against the continuing Whiteness of the state in the immediate post-independence era, political structures are still at the mercy of global coloniality. This is evidence of the triumph of structure over the agency of the majority, and it is safe to assert that in African countries, the political structure (the whole) is greater than the agency of its constitutive constituency (citizens).

This role of global coloniality makes Fanon (2017) essential. Frantz Fanon (2008) offered one of the most enduring analyses of the psychological and social effects of colonialism and racism on the psyche of colonized peoples. Central to his analysis are two interconnected phenomena: the internalization of inferiority and self-sabotage. Fanon theorized that colonial domination devalues the culture, appearance, and worth of Black subjects through every institution—education, law, religion, and media—until the colonized internalizes the prejudices of the colonizer. The result is a fractured self-perception where the colonized subject sees themselves through the gaze of Whiteness, leading to feelings of inadequacy, self-rejection, and a desperate desire to assimilate into the dominant colonial culture. The desire to escape the “stigma” of Blackness compels the colonized to adopt colonial languages, beauty standards, norms of governance, and social conduct (Wa Thiong’o, 1986; Glissant, 1997). However, as Fanon (2008, p. 80) poignantly observed, capitulating to the self-hating logic of “whiten or perish” does not secure acceptance. Instead, it deepens humiliation as proximity to Whiteness cannot erase the ontological condition of Blackness in a colonial world. In seeking recognition from the structures that dehumanize them, the colonized commit acts of self-sabotage and caught in an impossible dialectic of mimicry and rejection.

Building on this Fanonian framework, this article applies the concepts of internalized inferiority and self-sabotage to political structures and political agency in Africa. Since independence, African states operating in a Western-centric international system have adopted and retained colonial political structures, believing that alignment with Western norms would secure legitimacy, modernity, and global acceptance. Like the colonized individual seeking White approval, African states embraced Western constitutional models, governance frameworks, and legal systems, even at the expense of indigenous political forms and traditions that had historically structured African societies. However, the anticipated acceptance never materialized. Despite mimicking Western state forms, Africa continues to experience political marginalization and economic subordination within the global order (Grovogui, 1996; Zeleza, 2019, 2006; Zondi, 2021). The mimicry has not translated into acceptance. Domestically, citizens face alienation from political systems that remain fundamentally disconnected from lived realities. This has reinforced democratic disenchantment and cycles of protest, and rebellion. Here, the adoption of colonial structures is a manifestation of internalized structural inferiority—the belief that proximity to Whiteness, whether through governance or economic policy, is the pathway to recognition and dignity.

This phenomenon reveals a deeper layer of structural self-sabotage. African states unwittingly reproduce a structural conflict in their political culture that undermines their legitimacy by persisting with colonial political forms. As Maldonado-Torres (2007) contends, coloniality persists through political domination and the internalization of epistemic and ontological hierarchies that devalue indigenous knowledge systems and forms of governance. This article, therefore, extends Fanon’s insights into the domain of political structure and theorizes the crisis of postcolonial African democracy as a manifestation of this structural conflict. It proposes that the way forward requires a calculated rejection of colonial structural mimicry.

Defining democracy (and its illusion) in Africa

Before returning to Fanon to discuss how SC prevents democratic consolidation as a manifestation of the internalization of structural inferiority, I must first discuss democracy and its lack from the standpoint of its key proponents and scholars. To do this, I need to first answer the crucial question of whether democracy, as commonly understood, is inherently Eurocentric. Following Dahl, democracy is a procedural value that combines public control with political equality and which is realizable via multiple institutional forms (Dahl, 2000). Ake reminds us that democratic feasibility in Africa depends on historically grounded participation and material inclusion (Ake, 1996). Thus, democracy is not inherently Eurocentric, but the imposition of a liberal-procedural template universalized as neutral is. Democratization involves ‘meaningful and extensive competition among individuals and organized groups’; a “highly inclusive” level of political participation’ in which ‘no major (adult) social group is excluded’ leading to ‘a level of civil and political liberties’ and ‘integrity of political competition and participation’ (Diamond, 1988, p. 4). Amin (2014) echoed this understanding when he advocated for democratization which encompasses every sphere of social existence, including economic governance, and remains a continuous and open-ended process driven by the struggles and creativity of the people. If so, then democracy ought to be assessed in terms of the decision-making power of the majority. In that case, the majority of citizens, not just the elite, must be the source of tangible democratic impact and meaning-making.

This definition prioritizes the essence and goal of democracy—at the most fundamental level, human security—rather than merely governance processes. Similarly, democracy ought to penetrate the private sphere of the community, family, and street, allowing all segments of society to meaningfully and effectively partake in it. However, an enabling and empowering political culture is predicated on understanding the prevailing democratic structures and the modality of engaging with them, including the value of that engagement (Lipset, 1959, p. 73). In other words, there must be a political culture in which the traditions of society, ‘the spirit of its public institutions, the passions and the collective reasoning of its citizenry, and the styles and operating codes of its leaders […] fit together as part of a meaningful whole and constitute an intelligible web of relations’ (Feit, 1968, p. 180). This is necessary for democracy to function as a decision-making process involving citizens’ engagement with the political system and its impact on public policy (Gerodimos, 2001, p. 27).

To say that citizens do not have this involvement does not mean that elites are automatons of structure, while citizens remain passive agents. In line with Giddens’ duality of structure perspective (Giddens, 1984), the focus ought to be on relational agency and power. Here, power is ‘the chance of a man [person] or a number of men [collective] to realize their own will in a communal action even against the resistance of others who are participating in the action’ (Weber, 1946, p. 180). As Migdal and Schlichte (2005, pp. 14–5) note, while many actors are involved in ‘doing the state,’ both in cooperation and competition with others, the outcome of ‘such negotiation processes must be seen as imprints of domination by the more powerful [actors] over weaker groups.’ Politics, therefore, manifests as an interactive ‘exercise of choice by multiple actors within existing parameters’ (Chazan et al., 1999, p. 22). This truism implies two things. First, democracy is to be assessed based on the ability of the majority to participate in the production and distribution of democratic culture (Dahl, 2000, p. 159) and shape the direction of the democratic meaning-making and material outcome of that participation (Munck, 2016).

Secondly, participation and outcome must be against the opposing will and agency of a minority segment of society. Since political culture is an ‘important link between the events of politics and the behavior of individuals in reaction to those events’ (Verba, 1969, p. 516), democratic culture is, thus, considered democratic to the extent that all citizens have a fair chance to participate in democratic cultural production. Similarly, the will of the majority, acting against that of the minority, must dominate in terms of the outcomes of that culture beyond mere processes like “free and fair” elections and transfer of power. Otherwise, granting suffrage only to citizens at a certain age would make no sense since adult suffrage assumes that it is insufficient for electoral positions to be taken and expressed. Instead, their expression must be informed, effective and impactful. In other words, political agency is defined in relation to power structures. For meaningful democratic participation and consolidation, the sum of the political agency of the majority of citizens ought to dominate that of the minority. From this conclusion, DMD+ exists when the political agency of the majority is dominant in determining the desired outcome of the democratic process relative to the agency of the minority. Conversely, DMD− is where the political agency of the minority dominates. While the former enables (+) the interests of the everyday citizen to ultimately triumph in the “communal action” of political processes, the latter disables (−) that interest.

I admit that many African citizens sometimes engage in democratic politics far more than is usually assumed. Afrobarometer evidence shows that Africans report substantial democratic engagement, such as contacting leaders, joining community meetings, and attending demonstrations (Logan et al., 2021; Afrobarometer, 2024, 2025). Accordingly, comparative evidence from the Global Barometer Surveys (2023) indicates that Africans report substantial democratic engagement. A growing middle class and active civil society organizations in Africa are equally good signs of participatory politics. In this vein, civil society activism and grassroots movements challenge political structures and promote democratic participation. However, the contention is not the presence or lack thereof of civil society organizations and activism. Instead, it is in the outcome of these exercises. For instance, as Mills (2011, p. 14) notes, there is ‘little bottom-up pressure on leadership to make better choices, notwithstanding the encouraging growth of civil society in parts of the continent over the last two decades’. Despite substantial engagement, trust in political institutions and satisfaction with democratic performance are often low in Africa (Maathai, 2009), and this dissatisfaction and perceived non-responsiveness predict protest and, in some contexts, openness to military interventions (Afrobarometer, 2024, 2025). This pattern contrasts with some non-African regions, where high participation more often coincides with higher institutional trust.

Therefore, the comparative point is not that Africans participate more, but that high engagement can coexist with low institutional trust and political satisfaction (Logan, 2017). There lies the agency–outcome gap consistent with the DMD− condition theorized here. This negative kind of political agency perpetuates a political culture in which the “majority have their say (at elections) and the minority their way (in impact and outcome of governance),” thereby enabling most leaders of African countries to consistently dishonour the trust of their citizens and get away with it despite evidence of participation and engagement. In this regard, we cannot entirely speak of democracy in the countries concerned, since democratic governance is one where the actions of leaders, the statute that regulates them, their claims to authority, and the exercise of domination are a function of most citizens’ effective participation in civic and political life.

Types of political legitimacy

At the intersection of democratic processes and their outcomes, scholars have highlighted different kinds of legitimacy by which a democratic system can be accessed to the extent that it fulfils all kinds (Abulof, 2017; Schmidt, 2013; Scharpf, 2009). Abulof (2017) differentiates positive and negative political legitimacy, arguing that whereas the former answers who is the legitimator, the latter answers what is legitimate. The source of positive legitimacy is appropriate actors, while the source of negative legitimacy is appropriate actions (Abulof, 2017). Although appropriate and necessary, political actions like elections and protests do not make the everyday citizen the ultimate legitimator of leaders and their actions during, after, and between elections. Therefore, Scharpf (2009) conceives of input and output legitimacy, while Schmidt (2013) introduced the concept of throughput legitimacy. Here, the extent of a government’s political legitimacy can be examined by assessing the responsiveness to citizen concerns due to citizen participation, called input legitimacy, and the effectiveness of policy outcomes for the people, called output legitimacy (Scharpf, 2009). Throughput legitimacy highlights the political legitimacy between input and output legitimacy (Schmidt, 2013).

Throughput legitimacy is an extremely useful criterion because it sustains the link between input and output legitimacy. A government may respond to citizens’ concerns only during elections and abandon its promises once electoral (negative) legitimacy is granted. Positive political legitimacy must tick all three criteria of legitimacy. DMD+ produces positive legitimacy that passes at the input, throughput, and output levels. Where the political choices and expressions of the few dominate, governments survive based on negative legitimacy that comes from input legitimacy and democratic processes such as elections, without throughput legitimacy, which ultimately undermines output legitimacy. In other words, in countries that are supposed to practise democracy, DMD+ equals positive legitimacy, while DMD− equals negative legitimacy. While the former is essential for democratic consolidation, we cannot speak of true democracy where there is only negative legitimacy that comes from the latter, which is the case for most, if not all, the countries of Africa. As we shall discuss later, negative legitimacy is the outcome of SC and breeds coups, insurgencies, and armed rebellions as expressions of the structural self-sabotage and internalization of inferiority. Table 2 illustrates the operational indicators of DMD+, DMD–, agency and legitimacy as espoused in this article.

DMD+ is present where (i) input legitimacy shows inclusive rule-making access (e.g., language-accessible ballots, low barriers to petitioning), (ii) throughput legitimacy shows transparent, contestable procedures (open committee hearings, reasons-giving), and (iii) output legitimacy shows policy responsiveness to median citizen preferences. DMD− is present where these three channels are structurally compromised or blocked (Scharpf, 2009; Schmidt, 2013). Unlike neopatrimonialism, which explains rule via personalized exchange and informalization (Bratton and Van de Walle, 1997; Chabal and Daloz, 1999), DMD− is a relational outcome. It is the structural disabling of citizens’ democratic agency even where elections are present. Patron-client ties can be carriers of DMD−, but DMD− centres on compromised input-throughput-output channels rather than on patronage per se.

Notably, both DMD + and DMD– create their versions of structural harmonies. The former births Positive Structural Harmony (PSH) while the latter births Negative Structural Harmony (NSH). PSH denotes a durable fit between institutions and the majority’s agency such that input/throughput/output channels work credibly and outcomes reflect popular preferences (DMD+, positive legitimacy). NSH denotes a durable fit between political structures and a minority coalition’s interests. Here, procedures are internally coherent, yet they systematically displace majority agency, yielding DMD− and negative legitimacy only stabilized by coercion or co-optation. The distinction clarifies why some countries are “stable” yet democratically hollow, and it operationalizes harmony by asking not only whether structures are coherent, but for whom they are coherent.

Structural whiteness of colonial language

The sanctity of a state comes not from the legal or policy frameworks that establish it alone. More importantly, it comes, from the type of legitimacy that only citizens can guarantee. Joseph Strayer (2005, p. 5) observes that ‘a state exists chiefly in the hearts and minds of its people; if they do not believe it is there, no logical exercise will bring it to life.’ The evidence that the state in Africa draws its oxygen from Europe rather than from within is overwhelming (Ake, 1996; Ekeh, 1975; Mamdani, 1996; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2012; Rodney, 1975). The state in Africa is not born out of political contestation but of colonial subjugation. The artificiality of the state in Africa condemns politics to Whiteness more than anything else, since the state’s origin, languages of business, underlying norms, doctrines and principles remain predominantly Eurocentric. As stated earlier, SC is amenable to several factors and there can be no one way of illustrating it. One has to look at the totality of the state’s existence to appreciate how structural Whiteness denies DMD+. Below, I use the case of colonial language for illustration. Here “colonizer’s language” denotes the former imperial administrative tongue (e.g., English, French, Portuguese).

Language is more than a means of communication. For Fanon (2008, p. 2), possession of language means possession over ‘the world expressed and implied by this language.’ Wa Thiong’o (2009, p. 20) similarly identified language as ‘inseparable from ourselves as a community of human beings with a specific form and character, a specific history, and specific relationship to the world.’ Therefore, ascribing to a language means ‘assuming a culture and bearing the weight of a civilization’ and the appropriation of ‘its world and culture’ (Wa Thiong’o, 2009, p. 21). Fanon (2008) concludes that the more and better the colonized subject can speak the colonial master’s language, the “whiter” he (thinks he) gets and can gain a ‘feeling of equality with the European and his achievements’. No matter the justifications for it, adopting colonial language as the formal or preferred language of politics embeds the foreignness of the state in the hearts of most citizens.

Language, however, is essential for political understanding and democratic engagement and thus plays a critical role in democratic participation (McLaughlin, 2015). Indeed, ‘the context within which political activities take place and how messages are defined, diffused and received by people is of utmost importance in fostering a functional relationship between political communication and prompting of initiatives for national development’ (italics added) (Mutsvairo and Karam, 2018, p. 14). Mastery of the language of politics is, therefore, a prerequisite for effective participation and increased demo-agency. However, in many countries language has played the role of a gatekeeper that prevents ‘the access of the common man (sic) to the elite club of power and prosperity’ (Umrani and Bughio, 2017, p. 114). Where ballots, hearings, and legal drafts rely primarily on such languages, comprehension and efficacy gaps depress input/throughput access. Conversely, multilingual recognition and vernacular voter education correlate with higher turnout and comprehension in country cases such as South Africa (McLaughlin, 2015). Language, can stand between citizens who seek access to politics and elites who already have it. Across many African countries, therefore, it denies the fundamental prerequisite to participating in politics.

While citizens of different African countries have different colonial language literacy levels, hence varying levels of access to politics, it is important to highlight that most citizens of African countries do not have colonial/political language literacy at a level adequate to guarantee access to the system that governs them and the politics by which they are organized. This institutional mechanism agrees with Fanon’s and Ngũgĩ’s analyses of linguistic alienation and political agency (Fanon, 2008; Ngũgĩ’s, 1986). Language bifurcates the state and democratization. Alexandre (1972, p. 86) observation is, thus, still relevant today that:

Power, it is true, is in the hands of this minority. Herein lies one of the most remarkable sociological aspects of contemporary Africa: that the kind of class structure which seems to be emerging is based on linguistic factors. On the one hand, is the majority of the population often compartmentalized by linguistic borders which do not correspond to political frontiers; this majority uses only African tools of linguistic communication and must, consequently, irrespective of its actual participation in the economic sectors of the modern world, have recourse to the mediation of the minority to communicate with this modern world. This minority, although socially and ethnically as heterogeneous as the majority, is separated from the latter by that monopoly which gives it its class specificity: the use of a means of universal communication, French or English, whose acquisition represents a form of capital accumulation.

Language becomes one of the ‘hidden aspects of those institutional and cultural forces that maintained colonialist power and that remain even after political independence is achieved’ (Ashcroft et al., 2000, p. 56). It continues to disenfranchise the majority and hand over political control to the minority elite.

Measures such as listing indigenous languages as official languages and the proliferation of media channels that broadcast political events and analysis in local dialects have been implemented to address this language apartheid. In countries such as South Africa and Tanzania, this does improve democratic participation (McLaughlin, 2015). However, the murder of local languages and their inferiorization against colonial languages through what Wa Thiong’o (1986) termed ‘cultural bomb’ means local languages become second options or only special occasion languages. Local media houses that air political programs in local languages and dialects tend to ‘favor resource-endowed individuals/parties’ who ‘dominate the media with all kinds of messages and propaganda, especially during national election season’ (Diedong, 2018, p. 257). Thus, most citizens’ democratic participation is mediated by political pundits who master colonial languages and map the socio-political universe of the people for political point-scoring. Ultimately, their interpretations of the democratic process and decisions are primarily as self-interested and alienating as the Eurocentric political structures in which those interpretations are embedded.

In the end, as Hearn (2001, p. 43) maintains, even civil society organizations could be rendered into ‘an arena in which states and other powerful actors intervene to influence the political agendas of organized groups with the intention of defusing opposition’. Elites’ autonomy over the political use of language denies the autonomy of citizens in being independent and ‘sufficiently informed about government to exercise a participatory role’ (Dalton, 2006, p. 2). Under these circumstances, political culture becomes characterized by ‘systems based on personalized structures of authority where patron-client relationships operate behind a façade of ostensibly rational state bureaucracy’ (Taylor and Williams, 2008, p. 137). This facilitates elite capture of civil society, which prevents the state from finding meaning within indigenous ontologies and knowledge systems.

While the Whiteness of political structures bastardizes the majority of citizens, it allows the state to find meaning from outside, thereby perpetuating its Whiteness and elitism away from its locale. The elite minority, due to their proximity to Whiteness, thus can cling to power while perpetuating adverse internal conditions through strategies such as extraversion (Bayart and Ellis, 2000), mimicking Western states (Pritchett et al., 2013, pp. 14–15), outsourcing of political agency (Malito and Dan Suleiman, 2024), and negative sovereignty (Jackson, 1986). These leaders compensate ‘for their difficulties in the autonomisation of their positions and in intensifying the exploitation of their dependents by […] mobilizing resources derived from the (possibly unequal) relationship with the external environment’ (Bayart and Ellis, 2000, p. 218). Rodney (1975, p. 8), therefore, concluded that the postcolonial state in Africa has existed through defending an alliance between the ruling class and imperialism and ‘against the African people’. To him, Africa’s mini-states are ‘engaged in consolidating their territorial frontiers, in preserving the social relations prevailing inside these frontiers, and in protecting imperialism in the form of the monopolies and their respective states’ (Rodney, 1975, p. 8). Table 3 illustrates what DMD+ and DMD− look like in practice, using the case of colonial language usage.

Internalized structural inferiority and democratic self-sabotage

Colonialism entrenched European cultural, legal, and political norms as emblematic of superiority and civilization while simultaneously denigrating indigenous African systems. Eventually, the leaders of postcolonial states internalized the notion that Western frameworks of statehood, democracy, economic systems, and legal structures are innately superior, prompting them to adopt these models in pursuit of legitimacy, modernization and development as conceptualized by Western standards, even if doing so means marginalizing more congruent indigenous approaches that do exist (Ake, 1996). Thus, the predilection for Western models contributes to neglecting or degrading indigenous knowledge systems, governance practices, and social frameworks that might offer viable alternatives for societal organization in ways that resonate more with local traditions, needs, and aspirations (Englebert, 2000).

However, as I have established, transplanting Western democratic models without adequately tailoring them to local contexts can result in the formation of nominal democracies where formal structures are devoid of substantive democratic engagement and public participation, potentially exacerbating divisions, fueling corruption, and diminishing state efficacy (Hyden, 2006). In the frame of my argument, the imposition of systems misaligned with African societies’ sociocultural and historical realities has engendered governance issues such as legitimacy deficits, inefficiency, and conflict. Thus, the internalization of structural inferiority within African countries had led to democratic self-sabotage. We can speak of democratic self-sabotage to the extent that adopting White political structures detracts from citizens’ ownership of political culture and their effective participation in the democratic process. This, the article argues, is the case, as adopting White political structures has created ‘a relative lack of democracy in Africa [that allows African leaders] to get away with ruinous, self-interested decisions’ (Mills, 2011, p. 14). This democratic self-sabotage highlights a structural mechanism: postcolonial elites, having internalized colonial models as superior, adopt and preserve ill-fitting institutions that systematically undermine popular agency even while formal democracy persists (Diamond, 2002).

Following from the above, empirical evidence of democratic crises across Africa would constitute a political humiliation borne out of the Whiteness of political structures. Across several countries in Africa, including in the continent’s most applauded democracies such as Ghana and South Africa, Gyimah-Boadi (2015, p. 105) notes that ‘the exercise of authority enjoyed by presidents and their appointees effectively negates the voice of the people, as expressed via elections, print and electronic media, and even lawsuits’. A recent survey in Liberia indicates that six out of 10 people are unhappy with how the country is run (Afrobarometer, 2018). According to Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2024 survey, only 8 of 49 Sub-Saharan African countries (16%) are classified as “Free” (Freedom House, 2024). This marks a decline from earlier decades, with a regional pattern of democratic fragility, shrinking civil liberties, and flawed elections. Consequently, the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2023) finds that citizens’ expectations continue to outpace delivery. Satisfaction with governance is 10 points lower than performance scores in Participation and Rights, and progress in Human Development has slowed. Security and Rule of Law scores have declined in 29 countries (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2023).

Several factors substantiate these indictments of democracy in Africa. Firstly, over 30 years after the neoliberal turn or third wave of democratization, the ritual of violence during elections continues, including in celebrated African democracies like Ghana, where the last two elections claimed eight lives in 2020 and six in 2024 (Agbove, 2025). Relatedly, presidents in Burundi, Rwanda, Togo, Gabon, Uganda, Chad, Cameroon, Djibouti, the Republic of Congo, Sudan, Eritrea, the Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have fidgeted with presidential constitutional terms to stay longer in power. These phenomena have led to oxymorons that attempt to describe how democracy in many African countries is not democracy after all, namely, “constitutional coups,” “democratic coups,” and “dynastic coups” where incumbents and elites tweak the constitution and usurp political processes to take or perpetuate power (Camara, 2016; Mbaku, 2018). More recent examples include Alassane Ouattara in La Côte d’Ivoire (constitutional coup) and Mahatma Idris Derby of Chad (successfully staged a dynastic coup). Since 2020, there have been almost a dozen military coups across the continent. Both as the outcome and a manifestation of these events, trust in key African institutions has significantly declined.

Before the recent spate of coups, democratization in Africa between 1990 and 2010 registered significant setbacks, and democracy on the continent was becoming ‘increasingly illegitimate’ (Lynch and Crawford, 2011, p. 275). Within that period, there have been endemic corruption, widespread ethnic voting and violent politics of belonging, local realities of incivility and violence, and political controls and inequality (Lynch and Crawford, 2011, p. 275). A survey of voting intentions in 16 African countries by Bratton et al. (2012, p. 27) found that in countries with few dominant parties, voters prefer certain parties ‘because they wish to […] avoid retribution after the election’. Before the above cases of democratic oxymorons, Nwosu (2012, p. 11) concludes that African countries were headed ‘towards illegitimate and unpopular self-succession, hereditary trends, the appointment of proxies’. He acknowledged ‘a few instances of emerging liberal democratic regimes’ which included Ghana, where the last two elections claimed 14 lives.

What is perhaps a better evidence of democratic self-sabotage is that three decades of neoliberal democracy have done very little to achieve national cohesion in many African countries. The outcome is that there are perennial cases of widespread violent conflicts and popular anti-state resentments. While old conflicts smoulder across the continents, we can also speak of a “jihadist turn” in Africa’s experience with armed anti-state rebellion. Across the Sahel, Rift and Horn regions of Africa, locally grounded but globally affiliated militant groups that speak the language of religion have sprung up, with egregious human security consequences and economic cost. As of 2023, attacks related to jihadist groups in Africa’s Sahel region had increased by over 2,000% over the past 15 years (Institute of Economic and Peace, 2025).

In Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, casualties from terrorist attacks as of 2020 ‘increased fivefold since 2016 with over 4,000 deaths reported in 2019 as compared to an estimated 770 deaths in 2016’ (United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), 2020). In 2025, Africa is still the epicenter if global terrorism (Institute of Economic and Peace, 2025). Indeed, as Adrian Leftwich (1993, p. 615) noted decades ago, the rise of anti-state movements, coup d’états, and secessionist sentiments are the consequences of a state whose fundamental organizational framework is not accepted by the people (Leftwich, 1993, p. 615). While the above picture of democracy leaves out some nuance, it points to the fact that Africa’s three-decade-long experience with neoliberal democracy has translated into little people’s power, putting most citizens at the receiving end of elite power. Figure 1 is diagrammatic illustration of SC, from the internalization of structural inferiority to democratic self-sabotage.

Conclusion: toward structural blackening and DMD+

This article has argued that the crises of democracy in Africa cannot be fully understood through the narrow lens of democratic backsliding. Instead, they are manifestations of Structural Conflict (SC)—a dissonance between colonial political structures and indigenous/endogenous popular agency. Through a conceptual framework linking Structural Conflict, Dominant Majority Demo-Agency (DMD+), Dominant Minority Demo-Agency (DMD−), Internalized Structural Internalized Structural Inferiority, Structural Conflict, Dominant Majority Demo-Agency (DMD+), Dominant Minority Demo-Agency (DMD−) and Democratic Self-Sabotage, the article has demonstrated how inherited political architectures continue to alienate the majority of citizens, thereby undermining efforts at democratic consolidation. Table 1 above consolidates the conceptual components of Structural Conflict (SC) and related terms.

The continuing coloniality—what I have termed the Whiteness—of political structures in Africa undermines the development of political structures that are in harmony with the popular agency of the majority. It produces a political order in which elites, by their proximity to Whiteness (coloniality), enjoy enhanced democratic agency, while the majority, by their proximity to Blackness (indigeneity), remain structurally compromised in meaningfully engaging the political system. Rather than fostering a harmonious web between political structures and popular agency, the persistence of Whiteness barricades the citizenry behind deep colonial fault lines that are reproduced through practices such as language apartheid, legal alienation, and the devaluation of Indigenous institutions. As with the structural humiliation suffered by Africans who believed assimilation into Whiteness would yield acceptance, the adoption of colonial political structures has led to governance crises in the form of insurgencies, coups, conflicts and deepening democratic disenchantment across the continent.

This argument points to a sustainable path to nurturing, practising, and consolidating democracy. This is the pursuit of Structural Harmony, a condition in which political structures are organically aligned with the citizenry’s collective reasoning, epistemologies, and agency. Achieving such harmony, however, requires a deep existential rupture with coloniality. In the words of Fanon (2017, p. 192), it demands liberating ‘the black individual from herself’ through a process of “collective catharsis”—a collective cleansing of the inferiority complexes and epistemic subjugations inflicted by colonial domination. For Fanon, this will not be achieved by imitation or catching up with Europe but by finding ‘something different’ and asserting that ‘we today can do everything, so long as we do not imitate Europe’ (Fanon, 2001, p. 251).

While there are various strategies to achieve Structural Harmony to mitigate SC in African political cultures, this article contends that genuine transformation is impossible without engaging in what may be described as Structural Blackening (SB). SB is the deliberate reconstitution of political structures to shed their Whiteness and realign them with indigenous/endogenous realities. SB is, therefore, a process of epistemic, institutional, and cultural disalienation that rejects external pacification, recovers local political imaginations, and restores the centrality of African agency in political life. In doing so, political structures would increasingly become endogenous expressions of popular sovereignty. Although SB does not guarantee the automatic emergence of DMD+ or a perfect democracy, creating an environment where popular agency can thrive on its own terms is necessary. Without it, citizens will remain structurally disadvantaged vis-à-vis elites, who will continue to exploit the existing alignment between political structures and elite interests.

My argument does not suggest that achieving SB will be without challenges. Indeed, the risks of essentializing “tradition,” entrenching local elites, or fragmenting rights enforcement remain. However, safeguards such as rights supremacy (constitutional review over customary fora), minority-language accommodations, and periodic audits of throughput quality can reduce this risk. Hybrid designs show how reformers can use inherited institutions to advance structural alignment. Traditional authorities can complement elected bodies where chieftaincy retains legitimacy (Baldwin, 2016; Logan, 2008, 2009), and electoral-justice remedies can translate popular agency into outcomes within liberal frameworks. What this suggests is that SB is not about rejecting everything that liberal democracy represents. As Césaire (2010, p. 152) noted, ‘there are two ways to lose oneself: walled segregation in the particular or dilution in the “universal”’. The search for SB avoids both. It only targets those actions, beliefs and values that dismember, dehumanise, inferiorize, and disempower African knowing, being and doing. As Fanon (1986, p. 170) asserted, ‘I do battle for the creation of a human world—that is a world of reciprocal recognitions.’

However, hybrid regimes are fragile without broader structural shifts. The shifts towards SB could take concrete form through interconnected reforms that restore African languages as primary mediums of political engagement and educational instruction, decolonize curricula to foreground indigenous knowledge systems, and indigenize and diversify university pedagogy, learning materials, and historical studies to highlight African contributions to world development and civilization. It could also mean reimagining constitutional orders rooted in local traditions of governance and indigenous institutions such as chieftaincy systems and customary fora for civil matters while safeguarding constitutional rights (Adelman, 1998; Law Library of Congress, 2021).

As a medium for accessing knowledge, hence power, language remains critical. Language inclusion should be expanded to mandate bilingual or vernacular ballots, legislative hearings, and budget briefs, with government officials and representatives required to communicate in widely spoken local languages, even if interpreters would be required. Further reforms might include devolved participatory budgeting that empowers counties to co-decide spending priorities through audited feedback loops, as seen in Kenya’s Makueni and West Pokot counties (World Bank, 2016), and institutionalizing cultural accessibility by embedding indigenous protocols, consultation norms, and dispute resolution practices into formal governance. An additional step would be the creation of an oversight house, similar to a senate, composed of traditional and community leaders, mandated to review legislation for cultural congruence and grassroots legitimacy.

Despite the article’s theoretical orientation, it offers clear directions for future research. Comparative case studies across different African states could illuminate the varied manifestations of Structural Conflict, from latent to acute, and the contextual conditions under which different strategies for democratic renewal succeed or fail. Further research could also explore intersectional dimensions of power, investigating how gender, ethnicity, class, and regional inequalities intersect with Structural Conflict to shape patterns of political agency. Policy-oriented research could assess the impacts of specific governance reforms and decolonization efforts, and identify best practices and pitfalls. Finally, analyzing the role of external actors, such as donors, international institutions, or foreign states, in perpetuating or mitigating Structural Conflict would offer a fuller understanding of the global entanglements that shape African political dynamics.

Author contributions

MDS: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abulof, U. (2017). ‘Can’t buy me legitimacy’: the elusive stability of Mideast rentier regimes. J Int Relat Dev. 20, 55–79. doi: 10.1057/jird.2014.32

Adebanwi, W. (2017). Africa’s ‘two publics’: colonialism and governmentality. Theory Cult. Soc. 34, 65–87. doi: 10.1177/0263276416667197

Adelman, S. (1998). Constitutionalism, pluralism & democracy in Africa. J. Legal Pluralism 42, 73–98.

Afrobarometer. (2024). Africans want more democracy – but their leaders still aren’t listening (policy paper no. 85). Available online at: https://www.afrobarometer.org/publication/pp85-africans-want-more-democracy-but-their-leaders-still-arent-listening/ (accessed August 15, 2025).

Afrobarometer. (2025). African insights 2025. Available online at: https://www.afrobarometer.org/feature/african-insights-2025/ (accessed August 15, 2025).

Afrobarometer. (2018) Liberians views on democracy, trust and corruption: findings from Afrobarometer round 7 survey in Liberia. Available online at: http://afrobarometer.org/media-briefings/liberians-views-democracy-trust-and-corruption (accessed December 20, 2023).

Agbove, P. T. (2025). Blood on the ballot: Election violence in Ghana. Washington, DC: Institute for War & Peace Reporting (IWPR).

Alexandre, P. (1972). Languages and language in black Africa. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Amin, S. (2014). The democratic fraud and the universalist alternative. In: Samir Amin, SpringerBriefs on Pioneers in Science and Practice, Cham: Springer. 16, 75–90. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-01116-5_9

Ashcroft, B., Griffiths, G., and Tiffin, H. (2000). Postcolonial studies: The key concepts. 2nd Edn. London and New York: Routledge.

Badie, B. (2000). The imported state: Westernizing the political order. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Baldwin, K. (2016). The paradox of traditional chiefs in democratic Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Bates, R. (1981). Markets and States in Tropical Africa: the Political Basis of Agricultural Policies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bayart, J.-F., and Ellis, S. (2000). Africa in the world: a history of extraversion. Afr. Aff. 99, 217–267.

Bratton, M., Bhavnani, R., and Chen, T.-H. (2012). Voting intentions in Africa: ethnic, economic or partisan? Commonw. Comp. Polit. 50, 27–52. doi: 10.1080/14662043.2012.642121

Bratton, M., and Van de Walle, N. (1997). Democratic experiments in Africa: Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burton, A., and Jennings, M. (2007). Introduction: the emperor’s new clothes? Continuities in governance in late colonial and early postcolonial East Africa. Int. J. Afr. Histor. Stu. 40, 1–25. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034788 (Accessed October 17, 2025).

Camara, K. (2016) Here’s how African leaders stage ‘constitutional coups’: they tweak the constitution to stay in power. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/09/16/heres-how-african-leaders-stage-constitutional-coups-they-tweak-the-constitution-to-stay-in-power/ (accessed December 20, 2023).

Carothers, T. (2002). The End of the Transition Paradigm. Journal of Democracy 13, 5–21. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0003

Chabal, P., and Daloz, J.-P. (1999). Africa works: Disorder as political instrument. Oxford: James Currey.

Chazan, N., et al. (1999). Politics and society in contemporary Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner Publishers.

Cheeseman, N. (2015). Democracy in Africa: Successes, failures, and the struggle for political reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dahl, R. A. (2008). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Dalton, R. J. (2006). Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. 4th ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

de Walle, N. (2001). African economies and the politics of permanent crisis, 1979–1999. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Waal, A. (1997). Famine crimes: politics & the disaster relief industry in Africa. Indiana, IN: Indiana University Press.

Diamond, L. (1988). Class, ethnicity, and democracy in Nigeria: the failure of the first republic. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Diamond, L. (2002). Elections without democracy: thinking about hybrid regimes. J. Democr. 13, 21–35. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0025

Diamond, L. (2008). The democratic rollback: the resurgence of the predatory state. Foreign Aff. 87, 36–48. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/fora87&div=24&id=&page= (Accessed October 17, 2025).

Diedong, A. L. (2018). “Political communication in Ghana: exploring evolving trends and their implications for national development” in Perspectives on African political communication. eds. B. Mutsvairo and B. Karam (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 255–268.

Ekeh, P. P. (1975). Colonialism and the two publics in Africa: a theoretical statement. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 17, 91–112. doi: 10.1017/S0010417500007659

Englebert, P. (2000). State legitimacy and development in Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Ero, C., and Mutiga, M. (2023) The crisis of African democracy: coups are a symptom—not the cause—of political dysfunction. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/africa/crisis-african-democracy (accessed May 18, 2024).

Fanon, F. (2017). Black skin, white masks (C.L. Markmann, trans.; original work published 1952). London: Pluto Press.

Fearon, J. D., and Laitin, D. D. (2003). Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97, 75–90. doi: 10.1017/S0003055403000534

Feit, E. (1968). Military coups and political development: some lessons from Ghana and Nigeria. World Polit. 20, 179–193.

Finn, B. M. (2021). The popular sovereignty continuum: civil and political society in contemporary South Africa. Environ. Planning C Politics Space 39, 152–167. doi: 10.1177/2399654420941

Freedom House (2024). Freedom in the world 2024: The mounting damage of flawed elections and armed conflict. Washington, DC: Freedom House.

García-Rivero, C. (2022). Authoritarian personality vs institutional performance: understanding military rule in Africa. Politikon 49, 175–194. doi: 10.1080/02589346.2022.2072582

Gerodimos, R. (2001). Democracy and the internet: engagement and deliberation. J. Syst. Cybernetics Inf. 3, 26–31. Available online at: https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/1013/1/Gerodimos_Output_2.pdf (Accessed October 17, 2025).

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Glissant, É. (1997). Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

Global Barometer Surveys. (2023). Global barometer surveys results portal. Available online at: https://www.globalbarometer.net/ (accessed August 15, 2025).

Grovogui, S. N. Z. (1996). Sovereigns, quasi sovereigns, and Africans: Race and self-determination in international law. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2015). Africa’s waning democratic commitment. J. Democr. 26, 101–113. doi: 10.1353/jod.2015.0000

Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2021) Democratic backsliding in West Africa: nature, causes and remedies. Kofi Annan Foundation Report. Available online at: https://kofiannanfoundation.org/app/uploads/2021/11/Democratic-backsliding-in-West-Africa-Nature-causes-remedies-Nov-2021.pdf (accessed May 18, 2024).

Harbeson, J. W., Rothchild, D. S., and Chazan, N. (eds.) (1994) Civil society and the state in Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.