Abstract

This article examines the structural conditions and barriers of youth participation in rural regions of Eastern Germany. Combining quantitative data from the AID:A 2023 survey and qualitative case studies from municipal youth parliaments, the study investigates how spatial disparities, infrastructural challenges, and institutional frameworks shape young people’s political engagement. The findings demonstrate that urbanity and age are decisive factors for politicization, while infrastructural deficits and a lack of binding participatory structures hinder sustainable youth participation in rural areas. The study emphasizes the need for targeted support measures, such as strengthening local youth organizations, improving mobility infrastructure, and fostering a culture of political recognition.

1 Introduction

1.1 Youth participation: between democratic potential and contextual challenges

Youth participation is a central element of democratic societies, since they depend on the affirmation by following generations (Reinhardt, 2004). It encompasses a wide range of political activities – from conventional forms such as elections and petitions to unconventional practices like protests or boycotts, as well as digital expressions of political engagement (Grasso and Giugni, 2022, p. 13).

For the purpose of terminological clarification, this article adopts a broad understanding of the term participation. It refers to a wide range of forms through which individuals can take part in decision-making processes and thereby influence outcomes (Straßburger and Rieger, 2019, p. 230). Following Steinhardt et al. (2022, p. 441), the concepts of involvement and engagement are understood as subcategories of participation. In this sense, participation is conceived as an overarching category that encompasses various levels of inclusion – from simply being informed, to submitting proposals, to actively contributing to decisions, and ultimately to forms of civic self-initiative and empowerment (Rifkin and Kanger, 2002, p. 42; Straßburger and Rieger, 2019, p. 232).

Further elaborations and critical perspectives on the different stages of participation can be found in the theoretical framework (Chapter 2.3), particularly in reference to Arnstein’s model (1969).

The United Nations describes youth participation as key to the fundamental transformation of youth development. In this vision, young people are no longer seen as passive recipients of resources or as the cause of society’s problems, but rather as essential contributors to the development of their countries. Youth participation should be understood as the active and meaningful involvement of young people in all aspects of their own development and that of their communities. This includes empowering them to contribute to decisions affecting their personal, family, social, economic, and political lives (United Nations, 2007, p. 244). Youth participation is not only a developmental principle, but also a fundamental human right. According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), ratified by nearly every country in the world, young people have the right to express their views freely in all matters affecting them (Article 12) and to have those views given due weight. Additional articles guarantee freedom of expression (Article 13), access to information (Article 17), and the right to freedom of association (Article 15). Together, these rights form the legal foundation for meaningful youth involvement in democratic processes and public life. Ensuring these rights is essential for building inclusive, responsive, and just societies (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2009).

The involvement of young people in political processes is viewed not only as a fundamental prerequisite for the legitimacy and stability of democratic systems, but also as a means of strengthening individual competencies such as self-efficacy, negotiation skills, and political judgment (Revi, 2024, p. 128). It is now well-established that youth participation differs significantly from adult political engagement – both in terms of forms of expression and in terms of motivations and institutional opportunity structures (Weiss, 2020, p. 5). Studies show that many young people engage politically without belonging to traditional institutions. They oscillate between protest and institution, between the voting booth and the street, between digital activism and local engagement (Fisher, 2012, p. 119).

One form of participation examined more closely in the following sections is institutionalized youth involvement through so-called youth parliaments and youth councils, as established in many municipalities across Germany. These are locally anchored institutions to which young people are typically elected. Elections are usually held in cooperation with local schools, which provide an organizational framework for the process. In the municipal context, youth parliaments often receive a certain degree of support—through funding, professional guidance, or organizational infrastructure. In many cases, they are perceived as a voice of the youth and are consulted in local decision-making processes. However, the specific conditions, actual influence, and institutional integration vary significantly depending on local circumstances and political culture within each municipality. Therefore, analyzing youth participation requires a nuanced consideration of various forms of participation and the specific contextual conditions.

What matters are the contexts. Empirical studies demonstrate that the political participation of young people is strongly influenced by their social, cultural, and spatial environment. For instance, Şerban (2023) shows that particularly young people from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, with low formal education or without political participation role models in their families, are less likely to become politically active. This tendency is even more pronounced in rural areas, where structural barriers – such as limited infrastructure, lack of resources, or minimal institutional support – determine additional obstacles (Suppers, 2024, p. 127). Similar patterns of restricted political participation among youth in rural areas can be observed in other post-socialist regions of Europe, such as Croatia. Botrić (2023, p. 910) describes that young people in these regions have significantly less access to political participation opportunities and are less likely to engage in political activities. These observations can be interpreted as structural parallels to the situation in East Germany, even though historical and institutional path dependencies must be considered specifically.

Spatial contexts—particularly the rural–urban divide—constitute a central analytical lens of this study. Regional structures not only shape the opportunities and obstacles young people face in political participation, but also influence their experiences of political efficacy and belonging. Accordingly, this paper places special emphasis on examining how rurality and urbanity interact with patterns of youth engagement, with a particular focus on East German regions.

1.2 Youth participation in East Germany: structural inequalities and institutional development

Focusing on East Germany, it becomes evident that there are specific structural and cultural conditions rooted in a historically shaped transformation situation. Even more than three decades after reunification, there are still notable differences between East and West Germany. The sociologist Mau (2024) characterizes these differences as expressions of the enduring socio-cultural imprint of East German regions, which differ from West German regions in terms of lifestyles, political orientations, and institutional structures. East Germany is, in comparison to the West, more rural (Gropp and Heimpold, 2019, p. 471), economically weaker (Blum, 2019, p. 360), significantly affected by the emigration of young people (Meyer, 2018, p. 1032; Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge et al., 2022, p. 185), and exhibits an above-average aging of the population (Bode et al., 2023, p. 410). This constellation is also reflected in political behavior: lower voter turnout, weaker party affiliation, and a less developed civil society have been documented in numerous studies (Ekiert and Foa, 2011; Arnold et al., 2015; Grande, 2023). Mau (2024, p. 39) speaks in this context of a “braked democratization” and notes a “civil society weakness”,1 which manifests in low engagement rates and weak intermediate institutions such as trade unions, churches, or associations. Furthermore, the few existing associations tend to focus more on leisure activities and socializing than on political and social involvement.

Recent developments in Eastern Germany’s political landscape have raised growing concern. In particular, rural areas have experienced a rise in anti-democratic movements, public protests, and increasing electoral support for far-right parties (Manow, 2021). Official police statistics reflect this trend: incidences of right-wing extremist violence, hate crimes, and attacks on refugee shelters are significantly higher in Eastern Germany than in other regions. Between 2001 and 2013, the five eastern federal states consistently recorded the highest absolute numbers of far-right violent offenses among all German states (Kohlstruck, 2018)—even though their overall population is considerably smaller. This numerical prominence underlines the exceptional scale of the issue in these areas. In addition, representative population surveys have shown that far-right and xenophobic attitudes are more widespread in Eastern Germany than in the West, and in some areas are anchored in broader segments of the population (Rees et al., 2021, p. 122). More recently, observers have noted the emergence of new far-right youth groups—often extremely young, sometimes underage, and openly willing to use violence. These groups have adopted visual styles reminiscent of the 1990s far-right scene, including bomber jackets and combat boots. Some members are as young as 14–16 years old. Experts warn that Eastern Germany may be on the brink of a resurgence of the so-called “baseball bat years” (Litschko, 2025) referring to the post-reunification period in the early 1990s, when the country witnessed a sharp increase in far-right violence, particularly in the East (Bangel, 2022).

At the same time, countervailing developments can also be observed in East Germany. In recent years, various federal states have taken targeted measures to strengthen youth participation. For example, the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania established an inquiry commission for children’s and youth participation to improve structural and legal frameworks for participation (Wins et al., 2023). The state Brandenburg has recently legislated that youth participation in municipalities must no longer be viewed as a voluntary service, but rather as a mandatory task (Ruschin, 2022). Municipal youth parliaments are particularly relevant in this context. As institutionalized forms of interest representation, they offer young people continuous, structured, and thematically broad opportunities to influence local political decision-making processes (Roth and Stange, 2020, p. 7). Youth parliaments create learning spaces for democratic processes, promote self-efficacy, and strengthen local engagement. However, they often exhibit a strong top-down structure and align their design with the formal logics of adult parliaments, resulting in tensions concerning autonomy, representativeness, and actual influence (Gollan, 2024, p. 10).

1.3 Research gap and research question

Although youth participation has been the subject of extensive research, much of the existing literature focuses on urban contexts, national averages, or formalized participation settings. Rural regions, and particularly the structurally disadvantaged rural areas of Eastern Germany, have remained underexplored. Existing studies rarely consider how spatial disparities, infrastructural challenges, and institutional weaknesses specifically shape young people’s opportunities for political engagement outside of urban centers. Furthermore, while individual determinants such as education or socioeconomic status are well-documented, there is a lack of systematic analysis regarding the interaction between spatial structures and institutional opportunity contexts.

This study aims to address these research gaps by focusing on youth participation in rural regions of Eastern Germany. The central research question guiding the analysis is therefore:

Which structural conditions, spatial inequalities, and institutional barriers shape the political engagement of young people in rural regions of Eastern Germany?

2 Theoretical framework and state of research

The following sections provide a systematic overview of the theoretical foundations, empirically identified influencing factors, and the democratic-theoretical as well as the structural challenges of youth participation. Together, they form the conceptual foundation for the subsequent empirical analyses.

2.1 Theoretical foundations of political participation: social capital and rationales for youth participation

Political participation is widely regarded as a core element of democratic societies. This applies in particular to young people, as political socialization allows them to gain foundational experiences of political efficacy and belonging. In this context, youth participation is not merely considered a tool for civic education, but a necessary condition for long-term political inclusion and social integration.

Two overarching lines of argument structure the discourse on youth participation. First, a functional-instrumental perspective views the engagement of young people as a strategic response to societal challenges—such as political alienation, declining trust in institutions, or demographic transformation. Participation is understood here as a means to enhance democratic resilience. Second, a normative perspective emphasizes the democratic principle that young people are not simply future citizens, but already political subjects in the present, with legitimate rights to participation and voice (Bessant, 2003, p. 94; Meinhold-Henschel, 2008, p. 12).

These normative and instrumental perspectives can be linked to sociological theories—most notably, Robert Putnam’s concept of social capital. In his widely cited work Bowling Alone, Putnam (2000) describes a significant decline in social capital in the United States since the 1960s, associated with increasing individualization and a retreat from communal institutions such as political parties, associations, or churches. He distinguishes between “bonding capital,” which refers to cohesion within homogeneous groups (e.g., families or peer groups), and “bridging capital,” which connects individuals across social divides. The latter is particularly vital for democratic societies, as it fosters intercultural understanding, dialogue, and collaborative problem-solving:

“Bonding social capital constitutes a kind of sociological superglue, whereas bridging social capital provides a sociological WD-40.” (Putnam, 2000, p. 22)

In the context of youth participation, this implies that political engagement not only enables social integration, but also opens up tangible experiences of agency and influence. It creates opportunities for young people to become embedded in existing societal structures while actively engaging with diverse social groups, milieus, and generations. While numerous studies highlight the importance of early participatory experiences for later civic engagement (Lundberg and Abdelzadeh, 2025, p. 662), this assumption has been critically questioned. Critics argue that early participation may not automatically translate into long-term political involvement, but is instead shaped by contextual factors, opportunity structures, and ongoing reinforcement over time (Chan et al., 2014, p. 1829; Gaby, 2017, p. 940). Therefore, this study does not treat early engagement as a deterministic factor, but as one possible element in a broader process of political socialization.

To guide the empirical analysis, this study distinguishes between two key analytical dimensions: first, the tension between access and influence in participatory processes—i.e., whether young people can merely be present or also shape decisions. Second, it contrasts formalized and informal modes of youth participation, acknowledging that institutional settings (e.g., youth parliaments) may differ significantly from informal, project-based, or protest-oriented forms of engagement. These axes structure the comparative interpretation of qualitative and quantitative findings and enable a differentiated understanding of youth political agency in rural areas.

2.2 Determinants of participation and political interest

Young people engage in political life in a variety of forms and to varying degrees—but this participation is marked by significant social inequalities. Numerous empirical studies show that political involvement is especially common among adolescents with higher levels of education and from socioeconomically privileged family backgrounds (Cammaerts, 2016, p. 131).

Political engagement is shaped by an interplay of individual, social, and contextual factors. These include age, education, gender, socioeconomic status, migration background, and regional conditions. Adolescents with lower levels of formal education or those living in economically precarious circumstances participate considerably less in political processes. The same holds true—in many European contexts—for young people with a migration background, who have less access to formal participation formats and more frequently report experiences of political marginalization (Miera, 2009, p. 15; Walbrühl, 2021, p. 133). Studies also demonstrate that economic deprivation—particularly poverty and social precarity—has a limiting effect on political engagement (Cammaerts et al., 2014, p. 658; Schwieger, 2023, p. 420).

The Shell Youth Study, conducted regularly in Germany, provides comprehensive data on adolescents’ political self-understanding and engagement. While the study documented a sharp decline in political interest during the 1990s, it has reported a reversal of this trend since the early 2000s. In its most recent wave (Schneekloth and Albert, 2024), 42% of surveyed adolescents identified themselves as politically interested, with 8% reporting strong interest. Moreover, 37% indicated that political engagement is important to them. This highlights the importance of adolescence as a phase of political identity formation and increasing interest in public affairs. Political interest is particularly pronounced in the later stages of adolescence and is strongly correlated with higher educational attainment. Approximately 40% of young people are involved in institutional settings such as clubs or associations, while 46% report engaging actively through personal, non-institutional forms of participation.

Gender also remains a contested category in research on political engagement. Several studies have shown that male adolescents tend to rate their political competence more highly (Böhm-Kasper, 2006, p. 55; Zehrt and Feist, 2012, p. 112), whereas female adolescents are more likely to be active in traditional organizational settings, such as youth groups or associations (Gaiser et al., 2010, p. 433). Other studies note a gradual convergence in participation rates between genders over time (Gallego, 2007, p. 7).

Beyond social factors, spatial context plays a critical role in shaping participation. While overall levels of political engagement are relatively similar across urban and rural areas, the forms and pathways of participation differ significantly. In urban contexts, political discourse tends to be more polarized, dense, and contentious (Effing, 2021, p. 91). In contrast, young people in rural areas face particular structural barriers, such as long distances between home, school, and leisure infrastructure, limited mobility, and insufficient public services or institutional support (Grunert and Ludwig, 2023, p. 193; Brensing et al., 2024, p. 271).

Rather than treating rurality as a simple deficit category, it should be conceptualized as an analytically rich and heterogeneous context. As Lüdemann and Reichert (2025, p. 29) argues, rural areas can be understood as existing along a continuum between an “enabling rurality” and a “disconnected rurality”.2 While the former can offer young people social freedoms, close-knit community structures, and opportunities for agency, the latter is characterized by structural deficits and social inequalities in comparison to urban regions. This conceptual lens highlights that rural regions are not per se less participatory—but that opportunities for engagement depend on contextual configurations such as local governance, civic infrastructure, and mobility.

2.3 Youth participation between “tokenism” and “internal exclusion”

Despite the frequently emphasized societal and political importance of youth participation, its practical implementation often remains inadequate. While numerous studies document a growing willingness among young people to engage, there is a persistent lack of binding institutional frameworks that would enable meaningful participation (Cammaerts et al., 2014, p. 645). This results in a gap between political rhetoric and actual co-determination—a democratic deficit that becomes particularly evident in the case of young people (Bessant, 2003, p. 94).

Sherry Arnstein analyzed this tension in her influential model, the “Ladder of Citizen Participation” (Arnstein, 1969). She distinguishes eight levels of participation, ranging from complete “non-participation,” through symbolic involvement—referring here to a form of pseudo-participation—to genuine decision-making power. The middle rungs, such as “Informing” or “Consultation,” are described by Arnstein as “Degrees of tokenism,” which suggest participation while withholding real influence:

“When they are proffered by powerholders as the total extent of participation, citizens may indeed hear and be heard. But under these conditions they lack the power to insure that their views will be heeded by the powerful. When participation is restricted to these levels, there is no follow-through, no ‘muscle’, hence no assurance of changing the status quo.” (Arnstein, 1969, p. 217)

Applied to youth participation, this model reveals that many participatory formats remain at a symbolic level. Warming (2011, p. 121) describes such scenarios as instances where “children seemingly have a voice, but in fact have little or no influence.”

Iris Marion Young has also highlighted structural mechanisms of exclusion. She differentiates between “external exclusion,” which refers to the general denial of access to political arenas, and “internal exclusion,” where contributions may be formally permitted but are not taken seriously or are strategically dismissed. Young people experience this latter form when their statements are ignored, trivialized, or patronized—“others ignore or dismiss or patronize their statements and expressions” (Young, 2002, p. 55).

The central democratic-theoretical challenge is therefore not only to ensure formal access to participatory bodies, but also to secure the genuine recognition of youth contributions as equal and valid positions within political discourse (Young, 2002, p. 55; Nullmeier, 2015, p. 102). International studies—from countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia—underscore this issue: youth participation is often confined to seemingly apolitical issues and lacks legal safeguards. As a result, the ability of young people to exert real influence remains limited. Bessant (2003, p. 98) concludes:

“Youth participation is confined to specific issues that do not challenge the political power of policy makers on significant issues. There is no legislative or other framework operating, or proposed, that ensures what young people want or don’t want will not be overridden by adults who disagree with the views expressed.”

Participation thus often becomes a symbolic gesture devoid of substantive influence—a structural problem that must be critically examined, especially in the context of youth policy bodies such as youth parliaments.

2.4 Youth parliaments in rural regions: structural challenges

Children’s and youth parliaments are considered a key institutionalized form of youth participation at the municipal level. In these forums, elected or delegated young people represent the interests of their peers and make proposals to shape local living conditions (Richter and Riekmann, 2025, p. 299). Despite widespread willingness among young people to engage politically, actual participation—especially in Eastern Germany—often falls short of expectations (Oswald and Schmid, 1998, p. 147).

A central challenge lies in the high degree of heterogeneity in the legal and institutional design of these bodies. Depending on the federal state and local municipal constitution, youth participation may be legally binding, encouraged, or entirely voluntary (Fehser et al., 2023, p. 24). As a result, the actual integration of young people into municipal decision-making processes largely depends on the commitment of individual actors and the political will of the respective local authorities. In addition, structural power asymmetries exist between young participants and adult stakeholders. Compared to professional actors in municipal politics, young people generally possess less institutional experience, more limited knowledge, and fewer strategic resources. While their capacity for judgment is by no means inferior (Oerter, 1998, p. 44), they often lack sustained opportunities for participation and continuous integration into decision-making structures. These asymmetries can be understood through the concept of “generationing” (Alexi, 2014; Alanen, 2020, p. 143), which refers to the social structuring of roles, rights, and participation opportunities based on age. Generationing involves the social practices through which children and youth are assigned specific positions in society: “Children are children by force of generationing” (Alanen, 2005, p. 80). In the case of institutionalized youth participation, these roles and limits are frequently shaped by the authority and discretion of adult political decision-makers.

In practice, significant variation exists in how youth parliaments operate. Some have only the right to speak in public meetings, while others serve in advisory roles or are embedded in local statutes with formal participatory rights. In some municipalities, youth bodies are well-established and operate continuously; in others, they exist only sporadically or on a project basis. Their actual impact depends strongly on available resources, adult support, and the degree of integration into formal political processes. Moreover, many youth parliaments closely mirror adult political structures—with formal rules of procedure, ritualized meetings, and protracted decision-making processes. These rigid formats can significantly dampen young people’s motivation to participate (Stange, 2002, p. 26).

These challenges are particularly pronounced in rural areas of Eastern Germany. There, participatory structures are often rudimentary or unstable. Studies show that low levels of youth engagement are not the result of disinterest, but rather of a lack of accessible and meaningful participation opportunities (Effing, 2021, p. 88). Aggravating this situation, many municipalities face resource constraints that prevent them from providing sufficient staffing or suitable institutional frameworks for sustainable youth engagement (Just and Kallenbach, 2022, p. 139). Youth representatives are often expected to speak with a unified voice on behalf of “the youth.” This expectation can be overwhelming and fails to do justice to the diversity of young people’s perspectives (Beierle et al., 2016, p. 30).

Another structural barrier to continuous youth participation in rural areas is limited mobility. Participation in political meetings or project-based initiatives often requires long travel distances, which can make regular involvement difficult. Hüfner (2025, p. 181) emphasizes that mobility is a key factor in determining the everyday agency of young people. In rural areas, however, public transportation is often unreliable or insufficient, creating structural exclusions (Brensing et al., 2024, p. 271). Moreover, young people navigate competing demands from school, family, friends, and part-time jobs. Farin (2020, p. 132) notes that political participation competes not only with limited time but also with other leisure activities, which are themselves shaped by issues of spatial accessibility and availability.

In light of these structural constraints, many young people turn to alternative, less formalized forms of political participation. These include protest actions, youth-led campaigns, digital activism, or the creation of self-organized initiatives in their communities (Teixeira, 2024, p. 16). Such practices often emerge outside adult-controlled institutions and allow for more flexible, expressive, and autonomous forms of engagement. In contrast to formal youth parliaments—which may be perceived as rigid or overly bureaucratic—these informal modes of action are more responsive to the everyday lifeworlds and interests of young people (Cammaerts, 2016, p. 54).

However, they are rarely recognized as legitimate by local authorities and often lack resources, continuity, or institutional support (Olk, 2008, p. 17). This reflects a broader structural bias in youth policy, which tends to favor adult-shaped formats over youth-driven agency. Particularly in rural regions, where institutional infrastructure is weak, informal youth participation can serve as a vital outlet for civic expression—but only if it is acknowledged and supported as such (Booth et al., 2024, p. 16).

Taken together, youth parliaments in rural regions possess significant potential from a democratic theory perspective. Ideally, they could serve as arenas for deliberation in which young people are not only politically expressive but also collectively empowered to influence decisions. This potential is even more pronounced when youth participation is understood in broader terms—including both institutionalized and self-organized forms of engagement. In practice, however, this potential remains largely untapped. Strengthening these bodies sustainably will require not only legal and political commitment but also a critical assessment of existing participation formats in terms of their actual effectiveness and appeal to young people.

Based on the outlined theoretical foundations and the identified structural and spatial determinants of youth participation, the following empirical analysis explores how these dynamics manifest in practice. Specifically, it examines the conditions under which young people in rural regions of Eastern Germany engage politically, the barriers they encounter, and the participatory forms that emerge.

To guide this analysis, three interrelated analytical dimensions are derived from the theoretical discussion:

(1) generationing and age-based power asymmetries;

(2) symbolic and structural forms of exclusion such as tokenism or limited agency; and.

(3) spatial opportunity structures tied to rurality.

These axes serve as interpretative lenses throughout the empirical sections, linking young people’s experiences to broader institutional and geographical configurations.

3 Methodological approach

The present study employs a multimethod research design that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This approach aims to analyze youth participation in rural areas both in terms of its structural framework and from the perspective of young people themselves. Standardized survey data provide a broad empirical foundation for identifying general determinants and patterns of political engagement, qualitative case studies offer deeper insights into subjective motivations, interpretative frameworks, and perceived barriers as they emerge in the everyday lives of adolescents.

3.1 Quantitative secondary analysis: AID:A 2023

The survey Growing Up in Germany (AID:A), conducted by the German Youth Institute (DJI), represents the most recent data set of the institute’s long-term youth study. Implemented as a panel study in a multi-actor design, it collects data from children, adolescents, and their parents. The study aims to identify factors that contribute to successful growing-up processes and to describe the configurations and conditions associated with less favorable life trajectories (Kuger et al., 2024a, p. 7).

The most recent wave – AID:A 2023 – has been available in its processed form since late 2024. It includes a representative sample of approximately 12,700 target individuals aged 0 to 27 years, complemented by around 8,700 parental interviews. The combination of self-reports and third-party assessments allows for differentiated analyses of life situations, educational trajectories, and forms of youth participation. For the purpose of analyzing political activities and preferences, a subsample of 409 respondents aged between 14 and 24 years was selected. These individuals provided information on both their cognitive orientations toward political issues and their actual engagement in political activities, influence attempts, and protest actions. The resulting sample is a representative cross-sectional dataset—weighted by household affiliation—of this age group in Eastern Germany and is characterized by the following attributes.

The composition of the sample, as shown in Table 1, accurately reflects the young population in Eastern Germany. Key variables such as socioeconomic status and educational attainment were selected not only for their statistical relevance but also in light of theoretical discussions on structural inequalities in youth participation (Cammaerts et al., 2014; Schwieger, 2023).

Table 1

| Specifics | Representation | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 49% |

| Female | 51% | |

| Material deprivation | Not deprived | 74% |

| Deprived | 26% | |

| Education | Lower/medium level | 43% |

| Higher level | 57% | |

| Residential area | Rural | 40% |

| Urban | 60% | |

| Migration background | Yes | 10% |

| No | 90% | |

| Average age | 19.3 years | |

Quantitative sample for Eastern Germany—representation of selected characteristics.

The following explanatory notes refer to the operationalization of the variables used in the analyses: The gender variable includes only male and female categories, as other response options could not be analyzed due to low case numbers. The binary measure of material deprivation refers to the respondent’s household and is based on Eurostat criteria, such as the ability to cover unexpected expenses or to afford at least one annual holiday. Educational attainment is categorized into lower, middle, or higher trajectories based on age and educational status. Programs leading to a high school diploma were coded as higher educational attainment, while secondary and intermediate levels were classified as lower or middle. For residential location, the classification follows a size-based approach: municipalities with fewer than 20,000 inhabitants are considered rural; larger ones are classified as urban. A migration background is recorded if at least one parent of the respondent was born abroad. Political thinking and political action are closely intertwined, interdependent, and mutually reinforcing (Reichert, 2010, p. 72; Eckstein et al., 2013, p. 431). The analyses focus on a composite index of political activation, calculated as the mean of 9 individual items. This index captures both the cognitive dimension of political engagement – such as political interest and subjective assessments of issue salience – as well as actual participatory behavior. The latter include conventional forms of participation (e.g., voting, signing petitions) and non-conventional practices (e.g., protest actions, boycotts, or digital activism) (DiGrazia, 2014, p. 113; Pitti, 2018, p. 7). The survey instrument captures both attitudinal and behavioral aspects of political participation, reflecting the dual normative and functional logics discussed in the theoretical framework (Bessant, 2003; Meinhold-Henschel, 2008). The index demonstrates good internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.637). The analysis revealed a strong intercorrelation of the individual items on the construct “participation,” indicating solid construct validity and empirical discriminability. The item set includes the interest in politics in general as well as different forms of participation (depicted in Figure 1) like, e.g., voting, attending demonstrations, signing petitions, or taking part in public political discussions. The composite index reflects not only access to political arenas (e.g., through voting) but also perceived and actual agency—dimensions emphasized in theoretical discussions on tokenism and internal exclusion (Arnstein, 1969; Young, 2002). For time comparisons, the 2019 wave of AID:A was also used. It comprises a representative subsample of 600 young people from East Germany aged between 13 and 24 years.

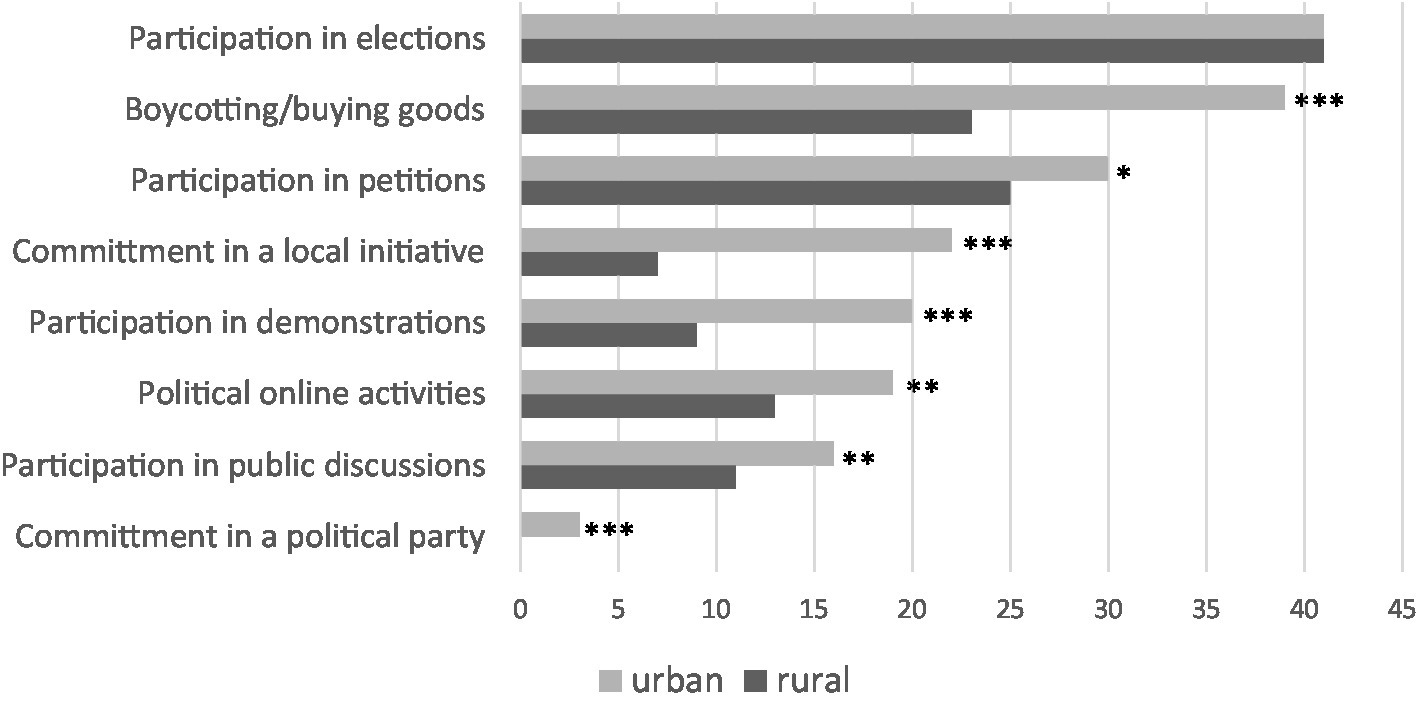

Figure 1

Forms of political participation practiced by young peple in Eastern Germany in the last 12 months (in %, 223 ≤ n ≤ 305) (For the analysis of the participation in elections only the sub-sample of those aged 16 or older (n = 223) was used, since they are already eligible to vote – at least on the local body and the level of the federal state). Significance levels (t-test): p < 0.001, p < 0.01, p < 0.05.

3.2 Qualitative case studies

In addition to the quantitative analysis, several qualitative case studies were conducted on child and youth participation in the rural Eastern German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Guided interviews were carried out following a semi-structured approach (Flick, 2023). All interviews were conducted in regions classified as “sparsely populated rural districts” (BBSR, 2023) according to the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development.

Following a desk research process that compiled online information from the past 2 years—including websites, Instagram pages, and news articles—on all youth parliaments in the federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, a theory-based sampling strategy was applied to select concrete case studies. The aim was to capture a broad variation along key characteristics of the youth parliaments (Strübing, 2014, p. 30). The selection criteria included: the size of the municipality, the geographical distribution of the requested groups, the presumed age of participants (inferred from online presence), and the degree of institutional establishment or professionalism, also derived from public-facing content.

Based on these criteria, three youth parliaments were selected as in-depth cases, each contrasting strongly in terms of the identified attributes. In each of the three regions, the research aimed to conduct two interviews with active members of the youth parliament, one expert interview with a local political stakeholder familiar with the field of youth participation, and—where available—an additional interview with a person serving as full-time support for the youth parliament.

Particularly the interviews with structurally embedded youth provided in-depth insights into the practical realities of local youth parliaments. Respondents shared their experiences, reflected on the specific regional contexts, articulated personal motivations, and described perceived challenges and needs for the further development of local participation infrastructures. Typical recurring interview questions included how their engagement originated and what motivated them to get involved. In addition, participants were asked to describe the work within the youth council, to share their current concerns and projects, and to reflect on the challenges and difficulties they encounter in the context of their participation.

In total, eight qualitative interviews were conducted with young people aged between 12 and 23 years (average age: 17.5 years). These were supplemented by four interviews with support staff and five additional interviews with political stakeholders involved in local youth participation processes. Each interview lasted between 40 and 60 min. The data were analyzed using a structured content analysis approach based on Mayring (2022). For the purpose of this article, the data from the youth interviews was analyzed deductively. Relevant passages were identified and coded with regard to youth participation practices as well as statements on enabling conditions, inequalities in access, and institutional barriers.

3.3 Potentials and limitations

This section reflects on the added value and limitations of the mixed-methods approach applied in this study. The presented multi-method approach highlights the strengths of a mixed-methods design, in which quantitative and qualitative perspectives complement and enrich one another. The quantitative data from the AID:A dataset allow for representative statements about the diversity of young people’s practices, providing robust statistical insights into political interests and participation patterns as well as differentiated analyses of social and geographical subgroups. By contrast, the qualitative approach offers access to young people’s lived experiences, shedding light on the underlying motivations and contexts of their participation. It adds depth and nuance to the interpretation of the quantitative results and provides practical illustrations that go beyond purely numerical representations. In this way, each method addresses the blind spots of the other, and this mutual enhancement leads to a more comprehensive understanding that combines standardized findings with rich, descriptive insights into individual perspectives. Together, they provide a deeper and more multifaceted understanding of youth political participation in rural areas.

Despite the strengths of the mixed-methods design, the approach also faces several limitations—particularly on the quantitative side. The AID:A dataset, while comprehensive in scope, prioritizes breadth over depth. It includes a wide range of topics such as employment, health, support measures, and family circumstances, but only limited detail on political participation. Although there are items on voluntary engagement, political attitudes, and value orientations, they remain relatively superficial. For this study’s focus on institutional participation, more detailed and specific items—particularly regarding organized forms of participation—would have been desirable. Youth parliaments, for example, which play a central role in the qualitative strand, are not adequately represented in the data. The few relevant items could therefore only be used in a limited way to establish meaningful connections between both strands of analysis, making the integration of findings more difficult. Furthermore, while the standardized survey enables broad insights into participation patterns, it is ill-suited to capture more nuanced or process-oriented aspects of youth participation. Dimensions such as symbolic forms of exclusion (tokenism), internal power asymmetries (generationing), or the perceived legitimacy of youth voice cannot be sufficiently addressed using quantitative indicators alone. These limitations are particularly significant in light of the theoretical framework, which emphasizes not only access to participation but also questions of recognition and influence. These conceptual dimensions are therefore explored in greater depth through the qualitative component, which is better suited to examine the internal logics and experiences of youth engagement.

The qualitative strand of the research also has limitations. By focusing on youth parliaments, only one of many possible forms of youth participation is examined—and one that is highly formalized and closely aligned with adult institutional structures. Informal, creative, or protest-oriented forms of participation are largely excluded. Moreover, the qualitative sample primarily includes young people who are already actively involved, leaving out other forms of youth participation in rural areas—such as self-organized initiatives that operate outside formal institutions and create autonomous spaces for action. This narrow focus limits the generalizability of the findings but enhances depth in one specific domain.

These limitations affect the degree to which the two strands can be fully integrated, but they also underscore the value of qualitative perspectives in contextualizing and enriching standardized data. Precisely because the AID:A dataset captures only a limited range of political participation, the qualitative component was deliberately designed to provide deeper insights into underrepresented dimensions. Thus, despite structural asymmetries between methods, their combination yields a theoretically grounded and empirically rich understanding of youth participation in rural contexts—one that captures both institutional frameworks and subjective experiences.

4 Empirical findings

4.1 Quantifying political activities in rural areas

4.1.1 Particularities of East Germany and political interest over time

More than three decades after the reunification of Germany in 1990, youth in Eastern Germany continue to grow up under distinct social, spatial, and structural conditions. According to a typology by the Thünen Institute (Ewert, 2021), all East German federal states—with the exception of the city-state of Berlin—are still classified as predominantly rural. Further structural characteristics, such as demographic ageing, weaker economic structures, and a lower proportion of people with a migration background further shape these contexts, as discussed in earlier sections.

To examine the research questions, cross-sectional data from the AID:A survey (Growing up in Germany: Everyday Worlds) from the 2019 and 2023 waves were analysed (Kuger et al., 2024b). The analyses—partly comparative over time—focus on respondents aged between 13 and 24 years, allowing both a comparative perspective over time and insights into political socialization during adolescence.

The results indicate that young people in East Germany report significantly lower levels of political interest than their peers in the West, although levels of actual political participation are similar. This suggests that attitudinal dimensions of political engagement diverge regionally, while behavioral patterns remain comparable—a finding that supports the notion of an underlying disconnect between political orientation and actual engagement, despite their statistically significant correlation.

A time-series comparison for East Germany shows a general decline in political interest from 2019 to 2023 – thus, the share of those young people stated to be politically interested “much” or “very much” dropping from 27.5% in 2019 to 23% in 2023. Notably, political attitudes were more polarized in 2019, with a greater share of both highly politically interested and completely uninterested respondents. This polarization may be linked to the election-rich context of 2019, which included local elections in all five East German states as well as the European Parliament elections. Correspondingly, a higher share of young people reported having voted within the past 12 months in 2019. In contrast, 2023 saw a general decline in most forms of political participation—except for involvement in local citizen initiatives, which appeared to be on the rise. This suggests that elections still act as catalysts for political socialization processes, drawing young people out of passive observer roles and prompting active engagement with political issues (Verba et al., 1995; Tillmann and Langer, 2000).

4.1.2 Determinants of politicization

Although rural areas are structurally heterogeneous, this analysis applies a dichotomous classification: “rural” refers to municipalities with fewer than 20,000 inhabitants, which are typified as small towns or rural communities in spatial monitoring by the BBSR (2024). In contrast, municipalities with 20,000 or more inhabitants are considered “urban.”

The results reveal that young people in urban areas of East Germany consistently show higher levels of political participation than their rural counterparts (see Figure 1). This applies to both conventional forms (voting, petitioning) and unconventional forms of participation—including, strikingly, even location-independent formats such as online activism. This may be partly attributed to the relatively poor digital infrastructure in many rural parts of East Germany (Arnold et al., 2016, p. 21). Overall, the data suggest that the degree of urbanity is a key predictor of both attitudes towards politics and engagement behaviors. While political interest itself does not differ significantly between urban and rural contexts, differences emerge in political self-placement: This reflects broader empirical patterns linking spatial context with ideological dispositions and suggests that urban environments may facilitate more pluralistic or left-leaning political cultures.

As the figure illustrates, these differences are especially pronounced in participation formats typically found in urban settings—such as demonstrations or engagement in local initiatives. In contrast, the urban–rural gap is less evident in location-independent forms of participation, such as voting or signing petitions online. These patterns can be partly explained by differing opportunity structures—urban areas tend to have a higher density of political events and civil society organizations (Norris, 2002). Moreover, cities are often marked by a more vibrant political culture in cities, which fosters greater public discourse and a stronger valuation of civic involvement (Putnam, 2000).

To assess the influence of various factors on political attitudes and participation, a composite index of politicization was created, combining the dimensions of political interest and engagement. Based on this index, multiple linear regression models were estimated—one for the overall German sample and one specifically for East Germany (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variable | Germany (n = 1,507) | East Germany (n = 409) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SD | Beta | SD | |

| Urbanity | 0.156 *** | 0.042 | 0.251 *** | 0.107 |

| Material deprivation | −0.132 *** | 0.044 | 0.059 | 0.114 |

| Migration background | 0.079 ** | 0.052 | 0.024 | 0.159 |

| Gender (male) | 0.035 | 0.020 | −0.030 | 0.066 |

| Age | 0.170 *** | 0.008 | 0.299 *** | 0.020 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.069 | 0.126 | ||

Linear regression model predicting the index variable “politicisation.”

SE, Standard error. Significance levels: p < 0.001, p < 0.01, p < 0.05.

A comparison of the two models shows that urbanity and age have significantly stronger effects on politicization in East Germany than in the national sample. In contrast, other factors that are typically central in the broader German context—such as socioeconomic disadvantage or migration background—are less influential. This finding suggests that regional context and structural conditions play an especially decisive role in shaping political engagement among young people in East Germany. A specific constellation of disadvantages—such as social inequality, limited infrastructure, and a low density of civil society organizations—appears to create significantly poorer conditions for political participation in rural regions.

4.1.3 Socio-demographic factors of non-participation

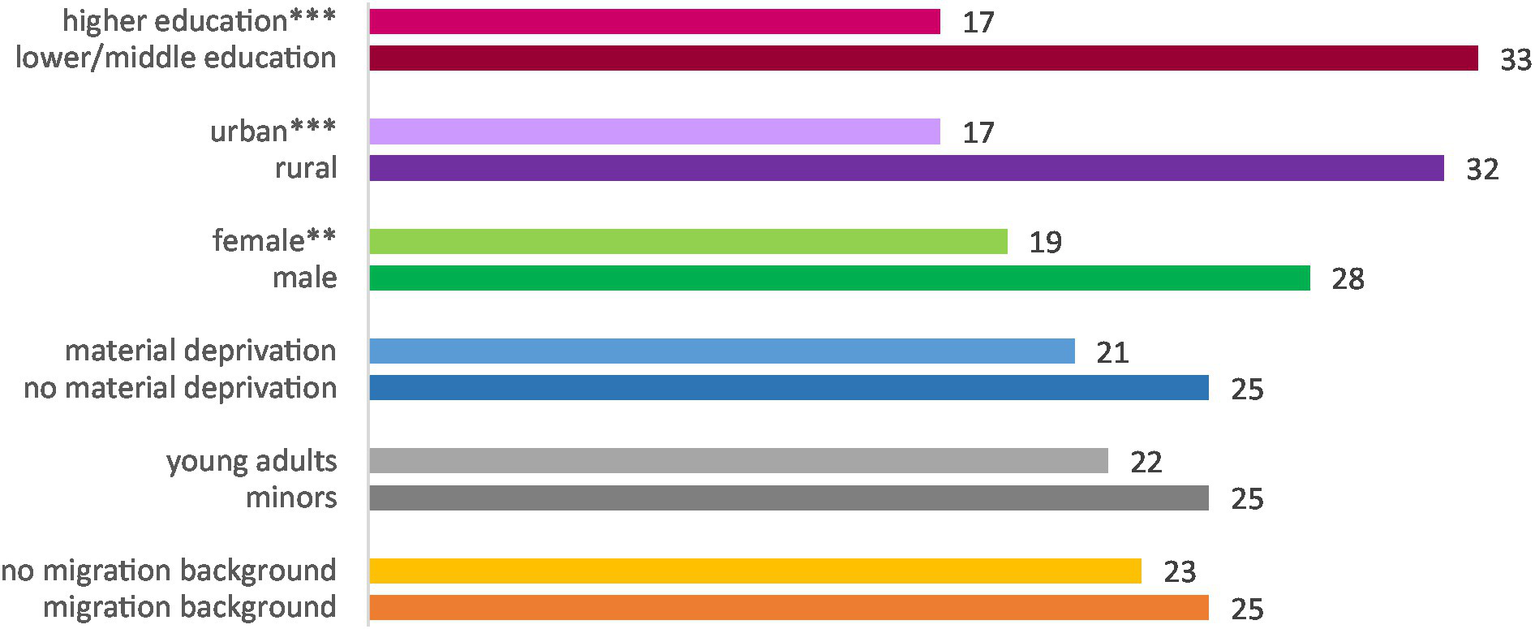

In order to examine the characteristics introduced above with regard to the extent of non-participation in politics, a target variable was created to represent minimum participation. It provides information on whether at least one form of participation has been used within the last 12 months. The percentage complement to this can be interpreted as an indicator of non-participation within the range of formats surveyed. This reveals clear differences (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Differences of political non-participation in any of the forms within the last 12 months by selected features (in %, n = 243). Significance levels (t-test): ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

The graph provides indications of which groups of young people are not reached by political offerings, with this proportion standing at 23% among young people in Eastern Germany as a whole. This does not rule out the possibility that there may be other, informal forms of political expression or protest that are not taken into account here, such as participation in camps or festivals on political topics as more experiential offerings in civic education (Berger and Frech, 1997).

Based on the significant differences, the influencing factors known from the state of research depicted in section 2.2 can be examined with regard to their applicability to the eastern German regions. This confirms findings according to which especially young men, young people with lower educational qualifications and those from rural regions are more likely to be politically inactive. Allthough there is a significant correlation of age and the extent of political participation – surprisingly, the group of minors is hardly more often completely politically inactive, which illustrates how unfounded the widespread view of decision-makers is, who question the political participation needs of young people (Beierle et al., 2016). However, the differences in terms of age, ethnic origin and material situation are not significant. Beside of that, the formerly mentioned subgroups are precisely the target groups that require special attention from those involved in civic education.

4.1.4 Young people and their place on the political spectrum

The right–left spectrum is a common heuristic for locating oneself within the political spectrum.3 In adolescence, such self-positioning—particularly on political matters—is a key developmental milestone (Autor:innengruppe Kinder- und Jugendberichterstattung, 2017). Among young people who identify as right-leaning, attitudes toward migration emerge as a central dividing line: this orientation is often linked with a rejection of immigration and cultural pluralism. Additionally, young people with right-wing orientations tend to express distrust toward political institutions and are more likely to hold anti-democratic views (Rommelspacher, 2006, p. 113).

The analysis first explores how right- and left-leaning young people differ in terms of political interest and participation. Respondents who identify as left-wing or leaning left report noticeably higher levels of political interest: 31% of them state that they are “very” or “quite” interested in politics, compared to only 19% of those who identify as right-wing or leaning right. This divide becomes even more apparent when examining political behavior: across all measured forms of participation, right-leaning youth engage significantly less frequently than the overall average. They cannot, therefore, be considered a particularly politically active subgroup.

The next step examines how political self-positioning correlates with individual and contextual characteristics. With regard to place of residence, a statistically significant association (p < 0.05) was found between right-wing identification and rural living environments. This finding supports broader research that identifies a stronger presence of conservative values and skepticism toward pluralism in rural areas across Europe (Weckroth and Kemppainen, 2023). However, contrary to widespread public assumptions, no significant differences in right-wing identification were observed between East and West Germany. This suggests that the electoral success of right-wing populist parties among young voters in the East may not necessarily reflect a stronger right-wing self-identification—but perhaps a different perception of these parties altogether.

Educational background also shows a clear association with political positioning. Only 3% of respondents with a high school diploma or enrolled in a university-track program identify as right-wing or leaning right, compared to 22% of those in secondary or vocational tracks. This suggests that higher educational attainment is associated with a lower susceptibility to right-wing ideologies. A similar pattern is found with regard to material conditions: nearly 19% of young people from materially deprived households identify as right-wing, compared to only 7% from more secure economic backgrounds. These findings align with previous research, which shows that social disadvantage can foster fears of downward mobility and promote scapegoating tendencies toward minorities (Yendell and Pickel, 2020).

Lastly, gender differences are also evident. Only 5% of surveyed young women identified as right-wing or leaning right, compared to 16% of young men. This gap may be attributed in part to the appeal of right-wing ideologies to traditional ideals of masculinity, which emphasize militarism, dominance, and hierarchy (Overdick, 2014).

4.2 Voices from rural youth parliaments

The following qualitative findings are based on semi-structured interviews with young people who are actively involved in municipal youth parliaments or similar participatory bodies in rural regions of Eastern Germany.4 The aim was to explore what motivates their participation, what expectations and hopes they associate with institutionalized involvement, and what barriers they encounter in day-to-day municipal politics. The interviewees come from various municipalities and youth bodies and are partially connected through interregional networks. Despite regional differences, their statements reveal striking structural similarities, recurring experiences, and shared challenges.

In the interviews, young people often spoke with visible pride about their concrete achievements and the wide range of projects they have already implemented or are currently advancing. These include the artistic redesign of a schoolyard shelter, decisions about the placement of youth-friendly benches in public spaces, the organization of discussion forums with local politicians, co-determination in the design and naming of playgrounds, and the independent planning of community sports events such as local football tournaments. Recognition of their work—through visits from regional politicians or local media coverage—is also perceived as highly meaningful. Some participants reported being regarded as official points of contact for local decision-makers, a sign of increasing responsibility and institutional trust.

These experiences not only foster a strong sense of self-efficacy but also contribute positively to personal development, self-confidence, and future aspirations. Many of the young people emphasized that their involvement taught them how to organize themselves, speak confidently in groups, and take on responsibility—skills they had previously had little opportunity to develop elsewhere. Moreover, such engagement opens up new social spaces: it facilitates recognition within the community, enables intergenerational connections, and may even inspire new interests or career paths.

This form of participation goes far beyond serving as a pedagogical tool. It represents a genuine democratic resource—tangible in its local impact and profound in its effect on the personal development of those involved. At the same time, despite this clear sense of empowerment, structural limitations and tensions also emerged—these will be further explored and contextualized in the following sections.

4.2.1 Motivation and highlights of local youth participation

In many cases, the initial motivation for participation stems from concrete, everyday issues relevant to the youths’ lives: requests for a youth club, a skatepark, or a sheltered meeting space. These concerns are directly linked to their leisure time and the quality of their immediate environment. The opportunity to contribute their own ideas and see tangible change fosters genuine motivation. Often, it is not only about symbolic recognition but about real experiencing real agency, influence, and the ability to shape one’s local surroundings.

The social aspect is equally important: many describe youth parliaments as spaces of belonging and shared community. Interactions with peers, collaborative project work, and even simple routines like sharing meals strengthen the sense of solidarity. For youth from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, participating regularly in such forums can provide access to additional social and emotional resources.

“It’s almost like a little family. You can communicate openly and comfortably here, you don’t have to be embarrassed, you can propose your ideas and plans. It really is a pleasant atmosphere. I’m also happy that we try to implement things so that young people have a voice and people know that something is actually being done here.”

(Case Study 2, Youth 2)

This quote illustrates a participatory mode that goes beyond mere presence and enables democratic involvement in the sense of empowerment. Being listened to without having to meet formal prerequisites alloes young people see themselves as legitimate political actors—regardless of their educational background or institutional status. In this sense, youth parliaments can foster a form of “bridging capital” (Putnam, 2000) that connects young people to broader social and political structures while building confidence in their own civic efficacy.

4.2.2 Challenges and structural tensions

At the same time, the interviews reveal a range of challenges. Access to established municipal decision-making structures is often described as difficult. Although many municipalities formally allow youth to attend committee or city council meetings, in practice, these opportunities are rarely utilized—not due to a desinterest, but because institutional practices are poorly aligned with the everyday realities of young people. Long evening meetings, a high degree of formality, and a lack of transparency can be discouraging.

“Technically we can always attend the council meetings. But we don’t go every time because they’re often REALLY REALLY… It’s all pretty dull and usually runs late into the evening. That wears on your nerves, and not everyone has time that late at night.”

(Case Study 3, Youth 2)

Another central challenge is the lack of formal decision-making power. Youth participants are typically limited to advisory roles—at best, they can offer suggestions or speak as guests. Many recognize this limited influence and describe their participation as non-binding or symbolic:

“The problem is, they don’t really have any guaranteed decision-making power. Theoretically, the committee could just say, when it comes to certain topics, we don’t care what the youth group says because, in the end, we decide ourselves.”

(Case Study 2, Youth 1)

These accounts expose a blurred boundary between meaningful participation and tokenism. Simply opening access to political spaces is insufficient without guaranteed agency. This reflects the theoretical frameworks discussed earlier, particularly those of Young (2002) and Arnstein (1969), which highlight the gap between nominal access and actual influence. Participation situated in these “degrees of tokenism” (Arnstein, 1969) can foster frustration, especially when youth recognize that their presence is valued rhetorically, but their impact remains marginal. Moreover, several interviewees described situations of “internal exclusion” (Young, 2002), in which contributions are permitted but ignored, trivialized, or framed as naive. This form of subtle marginalization often remains invisible yet deeply undermines perceived legitimacy.

Another recurring theme is the lack of structural support: many youth report insufficient guidance from municipal staff or professionals. They often lack clear points of contact, access to resources, and even physical meeting spaces. Understanding bureaucratic procedures and navigating municipal decision-making often exceeds their capacity without professional assistance.

“We’re kind of lost. We don’t get any support from the town hall or the city administration. […] You can’t expect us young people to deal with tax law and construction regulations. We also have school, and that takes up time too…”

(Case Study 1, Youth 1)

Such reflections illustrate a fundamental mismatch between the expectations of youth participation and the available support structures—be they temporal, emotional, or organizational. Especially in rural areas with limited mobility infrastructure, long and difficult travel distances to meetings further hinder participation. This imbalance is closely linked to generational power asymmetries. Drawing on the concept of “generationing” (Alanen, 2005), it becomes clear that youth are often positioned in subordinate roles defined by adult discretion. Their roles are often shaped by adult-defined expectations and formats, which restrict autonomy and self-determination and often provides few opportunities to gain experiences of self-efficacy.

A further structural barrier stems from the mismatch in timing between youth engagement and municipal policy cycles. While adolescents’ commitment typically spans only a few years, many local government initiatives take much longer to implement. As one interviewee remarked, “by the time a proposal is implemented, we are already too old to benefit from it.” This temporal misalignment is not only demotivating but also reinforces feelings of disconnection and disillusionment with institutional processes.

Such timing mismatches constitute a form of exclusion in their own right—when political responsiveness fails to match young people’s temporal realities, participation risks becoming irrelevant, even if formally open. In the end, they are in fact inattractive to young people.

4.2.3 Concluding reflection

Despite these challenges, all interviewed youth remained actively engaged—some for several years. Their continued commitment underscores a high level of civic motivation and place-based attachment, even under difficult conditions.

Yet, the findings also highlight the need to move beyond symbolic gestures toward institutional frameworks that genuinely empower young people. This includes not only legal and structural guarantees but also flexible, accessible, and youth-oriented formats of participation that acknowledge the diversity of their realities.

4.2.4 Theoretical synthesis and transition

The qualitative findings vividly demonstrate that the formal existence of participatory structures alone does not ensure meaningful youth engagement. Across interviews, participation often oscillates between genuine involvement and symbolic inclusion, reflecting Arnstein’s (1969) concept of “tokenism.” While young people may be heard, their ability to influence outcomes remains limited, particularly when participation lacks binding mechanisms or institutional follow-through.

Moreover, even when access is granted, the interviews reveal patterns of “internal exclusion” (Young, 2002): contributions by young people are often filtered, trivialized, or dismissed within adult-dominated political arenas. These dynamics undermine the democratic ideal of equal voice and recognition while they rather contribute to frustration and disillusionment.

At the same time, the structural asymmetries captured in the data reflect generational hierarchies—what Alanen (2005) terms “generationing.” Youth participation is often conditional upon adult-defined formats – especially in formalized committee work – and expectations, reinforcing the subordinate role of young people within institutional settings.

Despite these challenges, the interviews also demonstrate that when participation is supported by strong interpersonal relationships, accessible formats, and a shared sense of purpose, it can facilitate the formation of bridging social capital (Putnam, 2000). Under such conditions, young people are not only able to connect across social and institutional boundaries, but also gain confidence in their ability to meaningfully influence their surroundings.

Taken together, these findings suggest that meaningful youth participation requires more than access—it demands structural recognition, institutional responsiveness, and a critical rethinking of intergenerational power relations. The next section will further explore how these dynamics can be addressed and what conditions are necessary for participatory formats to realize their democratic and developmental potential.

5 Conclusion and discussion

This study explored the conditions and forms of youth political participation in rural Eastern Germany. Drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data, it examined how structural, spatial, and symbolic factors shape young people’s engagement, and under what circumstances participation becomes meaningful, limited, or even inaccessible. The findings reveal that political participation in rural areas is characterized by both formal inclusion and informal exclusion. Young people may be invited to participate, but their contributions are often undervalued, their engagement limited by infrastructural or procedural barriers, or their preferred modes of expression not recognized as legitimate forms of participation.

This tension reflects what Iris Marion Young (2002) describes as internal exclusion: when the conditions of participation are formally in place but fail to translate into real influence or recognition. Our study shows that this is not due to a general lack of political interest among rural youth. In fact, the AID:A data reveal that even though young people in Eastern Germany express lower levels of political interest than their western peers, their rates of actual participation are comparable.

However, the qualitative findings illustrate a persistent mismatch between the political lifeworlds of young people and the institutional logic of municipal politics. Participation is often organized in rigid, formal structures—like youth parliaments—that require long-term commitment, specialized knowledge, and bureaucratic navigation. These formats rarely align with young people’s needs for flexibility, immediacy, and relevance. As many interviewees highlighted, participation processes are frequently too slow, too abstract, or too disconnected from their everyday experiences. One interviewee noted, “By the time something happens, we are already gone.”

A second major challenge lies in the spatial barriers of rural areas. Public transport and digital infrastructure remain insufficient, and meeting places or youth centers are either unavailable or inaccessible. While the assumption that better broadband alone would lead to more digital participation remains speculative, the interviews suggest that digital infrastructure is a necessary but not sufficient condition: it must be accompanied by responsive, youth-oriented formats to be effective.

In response to these challenges, many young people turn to informal or self-organized practices—such as protest actions, school-based initiatives, or localized campaigns. However, these forms of engagement are often delegitimized by local authorities and excluded from formal decision-making processes. This reflects a broader structural bias towards adult-controlled participation formats, which do not account for the creative, spontaneous, and sometimes oppositional forms of agency that many adolescents prefer.

Despite these constraints, participation can succeed under certain conditions. When young people experience relational support, accessible formats, and a sense of collective identity, their participation fosters not only political engagement but also personal growth. As Bandura (1969) and Putnam (2000) suggest, such experiences strengthen both individual self-efficacyand bridging social capital. Interviewees who felt heard and supported described meaningful learning processes—negotiating, compromising, and working in teams. These findings confirm previous research showing that political engagement in adolescence can have long-lasting developmental effects (Bessant, 2003; Weiss, 2020). The empirical analysis contributes to the literature in several ways:

-

The study identifies exclusion mechanisms beyond formal access, highlighting how political participation is constrained by lacking symbolic recognition, spatial inequalities, and a mismatch between institutional practices and young people’s everyday lives.

-

It expands existing typologies of youth participation by showing how rurality, informal engagement, and institutional forms intersect in ways that challenge binary distinctions such as formal/informal or urban/rural.

-

It contributes a regionally grounded analysis by focusing on the specific participatory conditions and barriers faced by young people in rural eastern Germany, offering insight into a context that remains underrepresented in youth participation research.

From these insights, several recommendations follow. Youth participation must be systematically strengthened—not only in legal or institutional terms, but in how it is experienced by young people. This includes:

-

Reducing spatial and procedural barriers, e.g., through improved mobility, digital access, and the adaptation of participation timelines to the shorter commitment windows typical in adolescence.

-

Recognizing and supporting informal and self-organized participation as valid and valuable, rather than marginalizing it as unstructured or disruptive.

-

Expanding outreach-based and hybrid formats that meet young people where they are—in schools, public spaces, or online—rather than relying solely on council-based models.

-

Providing accessible entry points and short-term projects, where young people can experience quick feedback and visible outcomes.

-

Establishing local anchor structures (e.g., youth work institutions, advisory boards, regional participation hubs) that offer continuity, mentorship, and legitimacy.

Finally, this study opens avenues for future research. A key question is how participation can be re-designed in ways that truly resonate with young people’s lived realities—particularly in rural and structurally disadvantaged areas. Longitudinal studies could track whether youth who experience early self-efficacy in political processes remain engaged over time. Moreover, comparative research could further explore how rural contexts shape participation differently across national or regional borders.

In short, meaningful youth participation requires more than formal access. It depends on trust, recognition, accessibility—and the political will to let young people truly shape the spaces they inhabit.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://surveys.dji.de/.

Author contributions

SF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. FT: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ In the original German: "ausgebremsten Demokratisierung" und "zivilgesellschaftliche Formschwäche".

2.^ In the original German: "ermöglichende Ländliche" und "abgekoppelte Ländliche".

3.^ The division between a left wing aiming for change and social equality and a right wing focused on preserving the current or traditional status quo originally stems from the distribution of seats in the French National Assembly after 1789 Lamprecht (2023, p. 3).

4.^ The quotations included in this section were originally conducted in German and have been translated as closely as possible to the interviewees’ original phrasing and intent.

References

1

Alanen L. (2005). “Kindheit als generationales Konzept” in Kindheit soziologisch. eds. HengstH.ZeiherH.. 1st ed (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 65–82.

2

Alanen L. (2020). Generational order: troubles with a ‘travelling concept’. Child. Geogr.18, 141–143. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2019.1630715

3

Alexi S. (2014). Kindheitsvorstellungen und generationale Ordnung. Opladen/Berlin/Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

4

Arnold F. Freier R. Kroh M. (2015). Political culture still divided 25 years after reunification?DIW Econ. Bull.5, 418–491.

5

Arnold M. Neumann F. Pavel F. Weber K. (2016). Schnelles Internet in ländlichen Räumen im internationalen Vergleich. Berlin: MORO Praxis 5.

6

Arnstein S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Planners35, 216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225

7

Autor:innengruppe Kinder- und Jugendberichterstattung (2017). 15. Kinder- und Jugendbericht: Bericht über die Lebenssituation junger Menschen und die Leistungen der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe in Deutschland. Berlin: Autor:innengruppe Kinder- und Jugendberichterstattung.

8

Bandura A. (1969). “Social-learning theory of Identificatory processes” in Handbook of socialisation theory an research. ed. GoslinD. (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally), 213–262.

9