- 1Department of Communication and Community Development Sciences, Faculty of Human Ecology, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

- 2Rural Sociology Study Program, Faculty of Human Ecology, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

Since the enactment of Village Law No. 6/2014, rural communities in Indonesia have gained greater autonomy, aimed at promoting democratic governance and enhancing rural welfare. However, village democracy still faces persistent challenges, including elite dominance, limited civic participation, and unequal access to welfare. This study examines the relationship between democracy and welfare within the theoretical framework of deliberative democracy, using a mixed-methods approach in three ecologically and politically distinct villages in West Java: Gelaranyar, Margahayu, and Pantai Bahagia. The Village Democracy Index, based on eight indicators, is analyzed alongside the People’s Welfare Index, which captures key dimensions of socioeconomic well-being. The findings indicate that rational and inclusive deliberation, as well as the fair application of procedural rules in village decision-making, lead to more responsive policies and equitable allocation of resources. These democratic processes are positively correlated with improvements in health, employment, and social protection. However, enhanced transparency and civil society engagement do not always translate into better infrastructure or environmental outcomes. These results underscore the importance of strengthening deliberative, participatory, and data-driven village governance to promote inclusive and sustainable rural development. Reforms must ensure that village deliberative processes go beyond procedural compliance toward data driven substantive democratic practices to achieve equitable welfare outcomes.

1 Introduction

Over the past few decades, democracy has been globally promoted as a pathway toward improving human welfare. Yet, many democratic countries, especially in the Global South—struggle to deliver equitable welfare outcomes to their citizens. Democracy can provide welfare for its people; nevertheless, it does not provide a global remedy to address the inequities inflicted by free-market capitalism (Shammas, 2024). Likewise, decentralization and democratization are essential yet insufficient for rural development and poverty alleviation without genuine participation (Antlöv, 2003). In many emerging democracies, democratic institutions are vulnerable to elite capture and corruption, hampering their ability to deliver social justice and welfare (Tutuncu and Bayraktar, 2024; Foster and Rosenzweig, 2002). This theoretical challenge is evident in Indonesia’s efforts to institutionalize participatory rural democracy.

In the rural context, local democracy has enormous potential to become an instrument for improving the welfare of the people. As explained Asenbaum et al. (2024), local governance based on participatory democracy can play an important role in improving the quality of life in rural communities. Community-driven planning and governance that prioritizes direct community participation in the decision-making process can enhance the relevance and sustainability of local policies. However, this process requires a fundamental transformation in the way democracy is practiced, especially in areas with a history of marginalization or structural inequality. As Zhao et al. (2024) stated, the practice of democracy in rural areas through deliberative decision-making instruments is often hijacked by village elites who possess strong social and economic capital. The political decisions made do not always reflect the needs of the broader community and often benefit certain groups with greater political power (Knutsen and Rasmussen, 2020). Although democracy provides space for participation, high polarization can lead to instability and a decline in welfare in rural communities (Pied and Sappleton, 2023; Velásquez et al., 2021). This impacts village policy products that exacerbate socio-economic inequalities in rural areas.

This broader debate on participatory rural democracy resonates with Indonesia’s institutional shift through the Village Law framework, which formally embeds democratic principles into rural governance. Village Law No. 6 of 2014, later amended by Law No. 3 of 2024, grants villages the authority to manage their own governance and development based on local initiatives, customs, and participatory democracy. The law mandates democratic principles such as musyawarah desa (village deliberation), inclusive participation in development planning, and community oversight of village budgets and programs. These provisions aim to strengthen grassroots democracy and improve the welfare of rural citizens. However, the implementation of these democratic ideals at the village level remains problematic. Many village governments still operate under the influence of elite dominance, with limited genuine participation from marginalized groups. Deliberative processes are often reduced to formalities, lacking substantive dialogue or responsiveness to villagers’ actual needs. Consequently, the spirit of democratic governance envisioned by the Village Law has not been fully realized in practice. Previous research studies show that democratic village development is still not being carried out well, and the large amounts of money that were set aside for village development have not been used effectively (Sarawati, 2019). Azmi et al. (2020) stated that the financial resources designated for the communities have not succeeded in decreasing the poverty rate. This happens because of technocratic development planning, which only looks at the elite’s goals and interests and does not care about the community’s hopes and needs (Tjaija et al., 2020). The state’s programs to help people who are poor have big budgets, but they often fail to reach their goals because they are poorly planned, there is a lack of real accountability, organizers cut funding, resources are misallocated, and the same people keep getting social assistance funds (Gemiharto and Rosfiantika, 2017).

According to (BPS, 2023b), the poverty percentage in rural parts of Indonesia significantly exceeds that of metropolitan areas. In March 2023, the urban poor population declined by 0.24 million, from 11.98 million in September 2022 to 11.74 million. During the same year, the rural poor diminished by a lesser extent, specifically 0.22 million individuals (from 14.38 million in September 2022 to 14.16 million in March 2023). Specifically, in relation to the implementation of Village Law No. 6 of 2014, inequality increases from 3.12 to 3.18, while poverty has decreased from −1.48 to −0.08.

While numerous studies have examined democracy and welfare separately, there is a lack of empirical research in Indonesia that systematically measures both village-level democracy and rural welfare using a combined quantitative and qualitative approach. To date, no existing study has developed and applied an index to assess village democracy alongside a people welfare index at the village level.

Based on that background, this research departs from the urgent need to understand the correlation between democracy and community welfare, particularly in rural Indonesia. Therefore, this research has the following objectives: Firstly, the research aims to investigate the dynamics of democracy in rural areas, which includes the participation of rural communities in the electoral process, the evolution of political culture, and the interaction between village governments and the community. This study achieves this by investigating the measurement of the Village Democracy Index (VDI). Secondly, the research delves into the welfare conditions of rural communities, emphasizing their ability to meet basic needs. This research explores the measurement of the People’s Welfare Index (PWI). Third, this research analyses the correlation between democracy and the welfare of rural communities. With this understanding, it is hoped that this research can contribute to formulating policies that strengthen participatory democracy while simultaneously improving the welfare of rural communities.

1.1 Conceptual framework

Democracy in Indonesia ideally provides opportunities for the community to participate in decision-making and direct public policies that reflect the needs of the people, including in rural areas. However, in practice, democracy often has not yet become an effective instrument for improving the welfare of rural communities. On the contrary, the implementation of democracy at the village level is often undermined by the dominance of local elites and the minimal involvement of the community in the decision-making process (Alamsyah, 2009; Sjaf, 2014; Shohibuddin, 2016). The rural context in Indonesia, with its complex socio-economic structure, presents its own challenges in realizing substantive democracy and equitable welfare.

There is a strong correlation between democracy and the welfare of the people. Some previous studies explain that democracy is an important prerequisite for achieving the welfare of the people. Strong democratic institutions not only promote political and social stability but also improve economic indicators. As stated by Rivera-Batiz (2002), strong democratic institutions are capable of ensuring good governance and enhancing the economic growth of society. However, democracy must be accompanied by the rule of law, social justice, and effective civil liberties in order to support long-term welfare (Arslan and Küçük, 2024). There is a positive correlation between democracy and the welfare of the people. A fair and equitable democracy is necessary to ensure the welfare of the people equally, while equitable welfare of the people strengthens the legitimacy of democracy. The success of democracy in improving people’s welfare depends on the extent to which political rights and access to social services are evenly distributed at the local level (Giraudy and Pribble, 2019). Democracy plays an important role in expanding welfare programs for the people in middle-income countries, as well as contributing to the expansion of social programs such as health programs or cash transfers (Dorlach, 2021). At the rural level, a high level of village democracy significantly enhances community welfare through programs aimed at improving agricultural and forestry production efficiency (Xu et al., 2017). Supporting policies that meet basic needs like jobs, legal certainty, and voting in the government is an important part of a democracy. This makes room for social control to ensure openness and accountability in development, which in turn improves people’s well-being (Adhikari and Heller, 2024; Tobing-David et al., 2024; Vaijanath and Gadkar, 2024; Abbott et al., 2024).

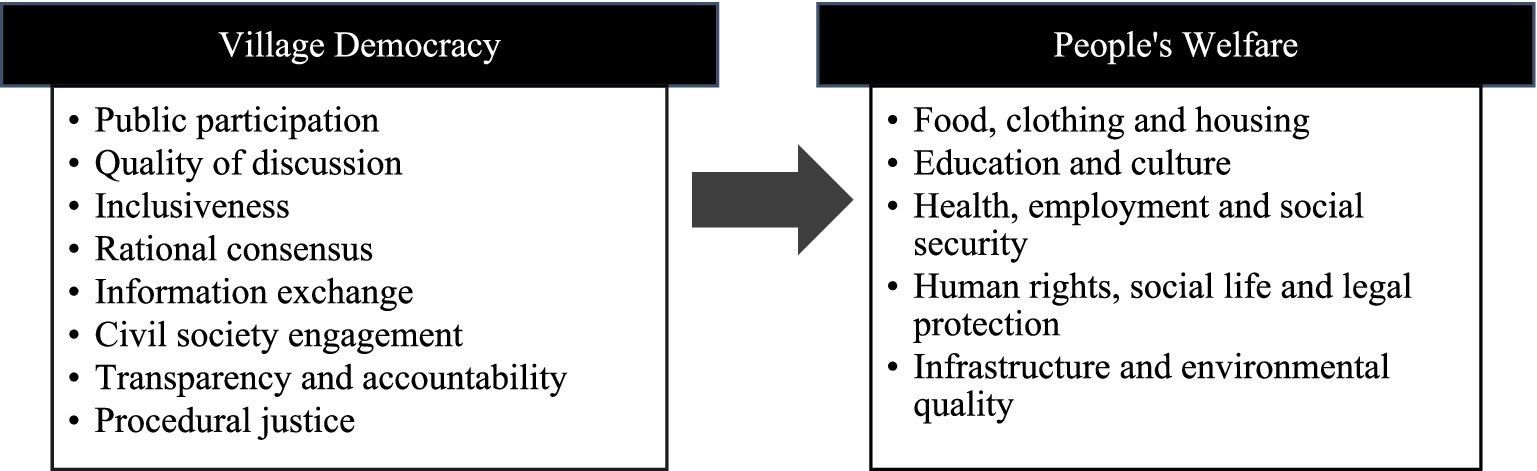

To illustrate the theoretical link between democracy and welfare, Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework that guides this study. It posits that village democracy, operationalized through indicators such as participation, transparency, and accountability, has a direct correlation with people’s welfare, measured by the fulfillment of basic rights including food, housing, education, health, and access to infrastructure and a sustainable environment. This framework reflects the assumption that democratic governance at the village level can foster more inclusive, responsive, and equitable development outcomes in rural communities.

Democracy not only functions as a system of government but also as a mechanism that can enhance the welfare of the people through responsive and inclusive public policies (Gerring et al., 2012). Democratic countries tend to have better public policies compared to non-democratic countries, especially in terms of welfare programs for the people (Mulligan et al., 2004). This is in line with the findings of Szikra and Öktem, which show that in countries experiencing a decline in democracy, welfare efforts can be hindered, negatively impacting rural communities (Szikra and Öktem, 2023). Many families in rural areas face obstacles in accessing welfare benefits due to a lack of information and available facilities (Reddy et al., 2021).

2 Research method

2.1 Research location

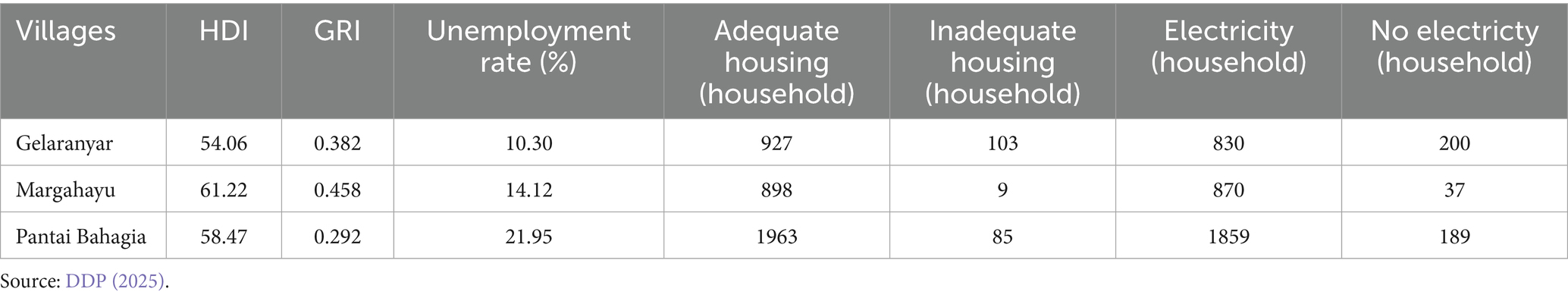

This research was conducted in three villages in West Java Province, namely Gelaranyar Village (Cianjur Regency), Pantai Bahagia Village (Bekasi Regency), and Margahayu Village (Subang Regency). The selection of locations was based on several key considerations that represent variations in democracy and welfare at the village level.

West Java was selected as it offers a strategic context for analyzing the intersection of village democracy and rural welfare. The province has consistently recorded a lower Democracy Index than the national average, particularly in the areas of civil liberties and democratic institutions. In 2020, for instance, West Java scored 69.57 on civil liberties (compared to the national score of 79.4) and 73.01 on democratic institutions (national score: 75.66). From 2018 to 2020, the province’s aggregate Democracy Index remained below the national average: 65.50 in 2018 (compared to 72.39 nationally), 69.09 in 2019 (compared to 74.92), and 71.32 in 2020 (compared to 73.66; BPS, 2021). In addition, this province also has the highest number of poor people in Indonesia (4,070,980 people) and a Gini Ratio Index (GRI) above 0.4 since 2014, indicating a significant level of inequality (BPS, 2023a). Thus, West Java provides an ideal context to explore the correlation between democracy and the welfare of rural people.

This study chose the three villages based on differences in welfare levels and economic inequality. Gelaranyar Village (Cianjur): Poverty 11.18% and GRI of 0.382. Pantai Bahagia Village (Bekasi): Poverty 5.21% and GRI of 0.292. Margahayu Village (Subang): Poverty 10.03% and GRI of 0.458. This study has more external validity because it uses these three villages to find patterns in the correlation between village democracy and welfare in a range of socioeconomic settings.

These villages have implemented Data Desa Presisi (DDP), a data collection methodology to produce a microdatabase that allows for more accurate welfare measurements compared to other secondary data. By using DDP, this research can reduce bias in measuring welfare indicators and ensure data accuracy at the village level (Sjaf et al., 2022).

Ecological typology is also an important consideration because it can influence patterns of political participation, access to resources, and the distribution of welfare. Gelaranyar Village (highland) is plantation-based. Desa Pantai Bahagia (coastal) is vulnerable to environmental changes. Desa Margahayu (lowland) has a more dominant agricultural sector. Considering the aspects of democracy, welfare, ecology, and data accuracy, the selection of this location is strategic in providing a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between village democracy and people’s welfare in Indonesia.

2.2 Data collection

This study employed a mixed-method approach. Quantitative data were collected using proportionate cluster random sampling, with sampling units based on neighborhood clusters (RW) in each village. The total sampling frame comprised 9,054 residents aged over 17 years from the three selected villages. Proportionate cluster random sampling was employed in this study, with sampling units based on the Rukun Warga (RW) in each village. The total sampling frame comprised 9,054 residents aged over 17 years from the three selected villages. The sampling frame was derived from secondary data sources, specifically the DDP of Gelaranyar Village (2021), Pantai Bahagia Village (2022), and Margahayu Village (2022). Using the Taro Yamane formula with a 10% margin of error (Olonite, 2021), the total sample consisted of 289 respondents, with the distribution as follows: 97 respondents from Gelaranyar Village, 95 from Margahayu Village, and 97 from Pantai Bahagia Village. The sample size for each RW within the villages was determined proportionally to their respective populations. In Gelaranyar, the distribution was as follows: RW1 (23), RW2 (20), RW3 (23), RW4 (16), and RW5 (15). In Margahayu, the sample size distribution was: RW1 (13), RW2 (15), RW3 (8), RW 4(9), RW5 (11), RW6 (14), RW7 (10), and RW8 (15). Finally, in Pantai Bahagia, the sample size was: RW1 (25), RW2 (13), RW3 (16), RW4 (7), RW5 (12), and RW6 (24). This ensures a proportional and representative sample from each village, reflecting the overall population distribution at the RW level.

All respondents were interviewed by trained enumerators using a structured questionnaire instrument. In addition, qualitative data were gathered through in-depth interviews with village officials, religious leaders, youth leaders, and women leaders in each village who possess insights into the village’s democratic processes and the welfare conditions of the local population. This combination of data sources ensured a comprehensive and context-specific understanding of the relationship between village democracy and people welfare. In addition to the primary data obtained through surveys and in-depth interviews, this study also utilised secondary data in the form of village development planning documents and data development achievment. The planning documents comprised the Village Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMDes) and the Village Government Work Plan (RKPDes). Data development achievment accessed from the Laboratory of Data Desa Presisi, IPB University, and the Ministry of Villages, Development of Disadvantaged Regions, and Transmigration in the form of the Village Development Index/Indeks Desa Membangun (IDM). These data sources provided contextual information on policy priorities, programme targets, and patterns of community participation in the formal planning process, as well as an overview of the development achievements of the villages under study.

2.3 Instrument validity and reliability

The validity of the research instrument was confirmed through a pilot test with 30 participants, where each question item was assessed for correlation, and items with a coefficient below r = 0.361 were excluded. This ensured that the instrument accurately measured the intended variables of village democracy and people’s welfare. Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha, yielding a value of 0.989, indicating excellent consistency across items, as values above 0.80 are considered very good (Priyatno, 2024). These high scores in both validity and reliability demonstrate that the instrument is both accurate and stable. Missing data and potential measurement errors were carefully managed through clear question design and appropriate data handling methods to ensure the integrity and trustworthiness of the collected data.

2.4 Data processing

This study employs the VDI to assess the quality of democracy at the village level. VDI consists of eight principal indicators that illustrate the quality of democracy. The indicators are public participation (PP), quality of discussion (QD), inclusiveness (IN), rational consensus (RC), information exchange (IE), civil society engagement (CE), transparency and accountability (TA), and procedural justice (PJ). Each indication is assessed using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, where the highest score signifies high democratic qualities. The value for each indicator is determined by averaging the scores provided by respondents in each village. The overall VDI value is calculated using the geometric mean approach by summing the scores from the eight indicators and dividing by the total number of indicators. The geometric mean is used to calculate the Village Democracy Index (VDI) because this method emphasizes the equal importance of each contributing dimension. In the context of village democracy, each dimension is considered non-substitutable. A low score in one aspect should not be offset by a high score in another, as the quality of democracy relies on a balanced and coherent system. This study determines the score for each indicator by calculating the average score of all respondents, as shown in Equation (1).

Explanation

: average score of democration indicator n.

: the score of the first respondent’s answer on that indicator.

N: number of respondents.

After obtaining the values from each indicator, the VDI is calculated using the geometric mean method of the eight indicators, as presented in Equation (2).

VDI categories are grouped into three levels:

High:

Medium:

Low:

The categorization of VDI into low (≤50), medium (51–80), and high (>80) is grounded in a normative and target-oriented framework that reflects the constitutional mandate of democratic governance in rural Indonesia. Rather than relying solely on statistical distribution, this classification serves as a benchmark for assessing the substantive realization of democratic principles as mandated by the Village Law (Law No. 6/2014). Democracy at the village level is not merely procedural but constitutes a legal obligation encompassing public participation, quality deliberation, inclusiveness, rational consensus, information exchange, civil society engagement, transparency, and procedural justice. A score above 80 is considered high because it indicates that these democratic values are being upheld as intended by law. Conversely, a score of 50 or below signals a critical deficiency in meeting these procedural obligations, thus justifying its categorization as low. This evaluative approach ensures that the measurement of democratic performance is not only empirically grounded but also normatively aligned with the legal and institutional expectations of participatory governance.

This study simultaneously computes the PWI to explain the welfare status of the villages under examination. The PWI assesses five primary indicators: the fulfilment of the right to food, clothing, and housing (FCH); the fulfilment of the right to education and culture (EDC); the fulfilment of the right to health, employment, and social security (HES); the fulfilment of the right to human rights, social life, and legal protections (HSL); and the realization of the right to infrastructure and environmental quality (IEQ). Similar to the VDI, each welfare indicator is assessed using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, with the final value of each indicator determined by averaging the values provided by respondents. The PWI value is calculated using the arithmetic mean of five indicators. The arithmetic mean is used in constructing PWI based on the principle that welfare is a cumulative outcome of multiple dimensions of basic rights fulfillment. Within the framework of national objectives, welfare is seen as a holistic ideal that integrates various socio-economic aspects. Each dimension complements the others and can independently contribute to improving people’s quality of life. This reflects the realities of development, where the fulfillment of basic rights often occurs incrementally and unevenly. This is consistent with the constitutional mandate that the state must pursue the welfare of all citizens through diverse, complementary pathways and sectors of development. The average computation for each welfare indicator adheres to the formula shown in Equation (3).

Explanation

: average score of the welfare indicator n

: the score of the first respondent’s answer on that indicator

N: number of respondents

After the values of each welfare indicator are obtained, the PWI is calculated using the arithmetic mean method of the five indicators, as presented in Equation (4).

PWI categories are grouped into three levels:

High:

Medium:

Low:

The categorization of the People’s Welfare Index into low (≤50), medium (51–80), and high (>80) is established through an evaluative framework anchored in the constitutional mandate to ensure the fulfillment of fundamental rights as stated in the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, particularly Article 28. Rather than reflecting statistical distribution alone, this categorization adheres to a normative ideal rooted in the foundational aspirations of the Indonesian state to guarantee the well-being of its citizens. The index encompasses five core dimensions: the right to food, clothing, and housing; the right to education and culture; the right to health, employment, and social security; the right to social life, legal protection, and human rights; and the right to adequate infrastructure and environmental quality. These dimensions reflect essential human needs and social entitlements that the state is obligated to fulfill. A score above 80 represents the adequate realization of these rights, while a score of 50 or below signals a critical failure to meet constitutional obligations, justifying its categorization as low. This evaluative threshold thus ensures that welfare assessments are aligned not only with empirical measurements but also with the legal and moral commitments of the Indonesian state to uphold social justice and dignity.

With this approach, this research provides a data-based overview of the complexity of the correlation between village democracy and the welfare of the people at the rural level. This study uses the simple average method to calculate VDI and PWI. This methodology ensures an objective measurement process, free from any subjective weighting that could potentially alter the results.

This study also analyses the correlation between democracy indicators and the welfare of the people in rural Indonesia. Data were obtained through questionnaires distributed to respondents in the three villages. Each question in the questionnaire is grouped based on democracy indicators and welfare indicators, which are then scored to calculate the total score for each respondent. Next, this study conducted a normality test of the data using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk methods to determine the data distribution. The test results indicate that the data does not follow a normal distribution (p < 0.05), so the Spearman correlation test was used for the correlation analysis instead of a parametric method. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the monotonic relationships between village democracy indicators and welfare indicators. However, while this non-parametric method is useful for identifying monotonic relationships, it does not control for potential confounding variables.

The Spearman correlation test is used to measure the correlation value between democracy indicators and people’s welfare. The Spearman correlation calculation yields a correlation coefficient (𝜌) ranging from −1 to 1, where a positive value indicates a direct relationship, a negative value indicates an inverse relationship, and a value close to zero indicates a weak or insignificant relationship. Significance tests were conducted at the p value 0.01 and p value 0.05 to determine whether the detected relationships are statistically significant. The correlation results are then visualized in the form of color scale diagram, where “red color” indicates a strong positive correlation, “blue color” indicates a strong negative correlation, and white indicates a weak or insignificant relationship. This visualization illustrates the patterns of the correlation between democracy and welfare across many villages, enhancing comprehension of the economic and social dynamics in rural Indonesia.

2.5 VDI indicators and parameters

The VDI in this study was developed based on a combination of various sources to ensure a more accurate and contextual measurement of democracy at the village level. The indicators used in the VDI do not appear randomly but are the result of a synthesis of various approaches that have been developed in previous democracy studies. This study looks at the ideas of public participation (Boese, 2019), the quality of public discussion (Fuchs and Roller, 2018), political inclusiveness (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., 2012), rational consensus (Bühlmann et al., 2012), information exchange (Møller and Skaaning, 2021), civil society engagement (Bethke and Pinckney, 2021), transparency and accountability (Beliakova, 2021), and procedural justice (Chan, 2022). The first indicator is public participation in elections. This indicator encompasses the freedom and fairness of elections, including their transparent and intimidation-free conduct. Boese notes that free and fair elections are one of the important components in measuring democracy (Boese, 2019). The second important component is the quality of public discussion. Institutional structures not only determine the quality of democracy but also the ability of citizens to engage in political discussions. They propose that the measurement of democratic quality should include indicators that reflect active participation and community engagement in the decision-making process (Fuchs and Roller, 2018). Third, inclusiveness. This indicator assesses the extent to which various groups in society, including minorities, are represented in the political process. Fair representation in government is an important indicator of a healthy democracy (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., 2012). Fourth, there should be a rational consensus. Consensus is an important value in deliberative democracy. Consensus helps ensure that the decisions made reflect integrity and consistency, allowing society to act as a united agent. Rational consensus is an integral part of measuring the quality of democracy (Bühlmann et al., 2012). The fifth indicator is the exchange of information. Freedom of the press and access to information are also important indicators. Møller and Skaaning emphasize that a free and independent media is key to ensuring accountability in governance (Møller and Skaaning, 2021). The sixth indicator is civil society engagement. This indicator includes the level of public participation in the political process, such as voter turnout in elections and involvement in civil society organizations. Bethke and Pinckney use participation measures as one of the components in assessing the quality of democracy (Bethke and Pinckney, 2021). The seventh component is transparency and accountability. Transparency, accountability, and the effectiveness of government institutions are important aspects of measuring the quality of governance as part of the measurement of democracy (Beliakova, 2021). The last, procedural justice is an important role in shaping individuals’ social identities within groups. They argue that fair procedures can enhance cooperation and compliance among the public with decisions made by the government, which in turn strengthens the legitimacy of democracy (Chan, 2022).

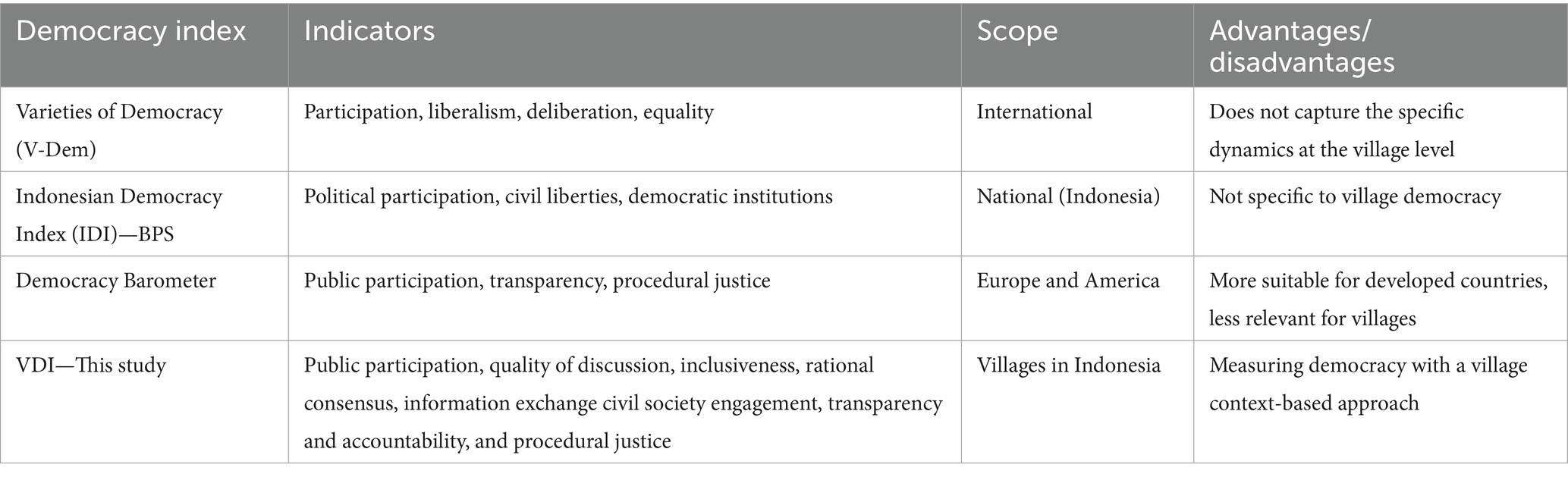

The VDI employed in this study incorporates elements from other global democracy indices, such as Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), Democracy Barometer, and the Indonesian Democracy Index (IDI) from BPS, but is modified to align with the democratic context of Indonesian villages. This combination allows the VDI to assess democracy not only through electoral dimensions but also through deliberation, transparency, and accountability facets of village governance. This is a comparison of the VDI with other democratic indicators (Table 1).

The assessment of the democracy index entails the evaluation of multiple variables that signify the level of democracy, civic engagement, and political liberty. Employing a multifaceted perspective and suitable methodology allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the status of democracy in different nations. In a rural context, evaluating the VDI is crucial for assessing government quality and community engagement at the village level.

This research computes the VDI utilizing eight indicators. The elements include public participation (PP), quality of discussion (QD), inclusiveness (IN), rational consensus (RC), information exchange (IE), civil society engagement (CE), transparency and accountability (TA), and procedural justice (PJ). The researcher formulates the subsequent operational definitions for each indicator (Table 2). Eight indicators, reflecting the main aspects of democratic practices at the village level, form the basis for measuring the VDI. The first indicator, public participation, evaluates community involvement in various political processes, such as elections, public discussions, and acceptance or rejection of money politics, to measure the level and quality of participation. The second indicator, the quality of discussion, assesses the extent to which discussions in village deliberations are based on accurate information, provide equal opportunities, respect differing views, and are free from the threat of violence. The third indicator, inclusiveness, measures the involvement of minority or underrepresented groups in the decision-making process, as well as the extent to which their views are respected and considered. The fourth indicator, rational consensus, assesses whether political decisions are based on rational argumentation, considering all viewpoints, and free from the dominance of certain groups or discrimination. The fifth indicator, information exchange, evaluates the ease with which the community can access information about the political process, decisions, and village head candidates to support effective participation. The sixth indicator, civil society engagement, looks at how often and how well members of civil society get involved in politics. This includes how they interact with the village government and any possible problems, like threats to the right to gather. The seventh indicator, transparency and accountability, assesses the openness of the village government in conveying information, providing reasons behind decisions, and involving the community in the decision-making process, as well as the willingness to accept responsibility if mistakes occur. Lastly, procedural justice evaluates the fairness of the decision-making process, the equality of citizens in voicing their opinions, the consistent application of rules, transparency, and the influence of certain groups in that process. These eight indicators provide a comprehensive picture of the quality of democracy at the village level, from community participation to transparency and procedural fairness in decision-making.

2.6 PWI indicators and parameters

Measuring the PWI is an important aspect of understanding and evaluating the socio-economic conditions of society. Various approaches have been proposed to measure well-being, which include economic, social, and environmental indicators. One of the approaches often used is the Human Development Index (HDI), which measures well-being based on three main dimensions: health, education, and income. However, Pratama and Nasrudin show that the Human Development Index (HDI) does not provide a comprehensive picture of people’s welfare (Pratama and Nasrudin, 2022). Well-being is also often trapped in unsustainable approaches, such as the use of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the primary measure. They argue that GDP is unable to accurately reflect the welfare of the people because it does not consider environmental impacts and other social aspects (Yanuarti and Rachmawati, 2022). This underscores the necessity for the creation of a more comprehensive welfare index that incorporates sustainability aspects.

The welfare state plays an important role in improving the welfare of the people through the fair distribution of resources. State intervention is necessary to address market failures and ensure the welfare of society (Sukmana, 2017). This indicates that the measurement of welfare does not only depend on economic indicators but also on public policies that support fair distribution.

Based on Sjaf et al. (2021) and Sjaf (2023), the Indonesian constitution says that the state’s job is to promote the welfare of the people. This includes meeting their basic needs in five areas: the fulfilment of the right to food, clothing, and housing (FCH); the fulfilment of the right to education and culture (EDC); the fulfilment of the right to health, employment, and social security (HES); the fulfilment of the right to human rights, social life, and legal protections (HSL); and the fulfilment of the right to infrastructure and environmental quality (IEQ). Overall, measuring the PWI requires a multidimensional approach and consideration of various factors that influence the quality of life in society. By combining economic, social, and environmental indicators and considering the local context, we can obtain a more accurate picture of the people’s well-being.

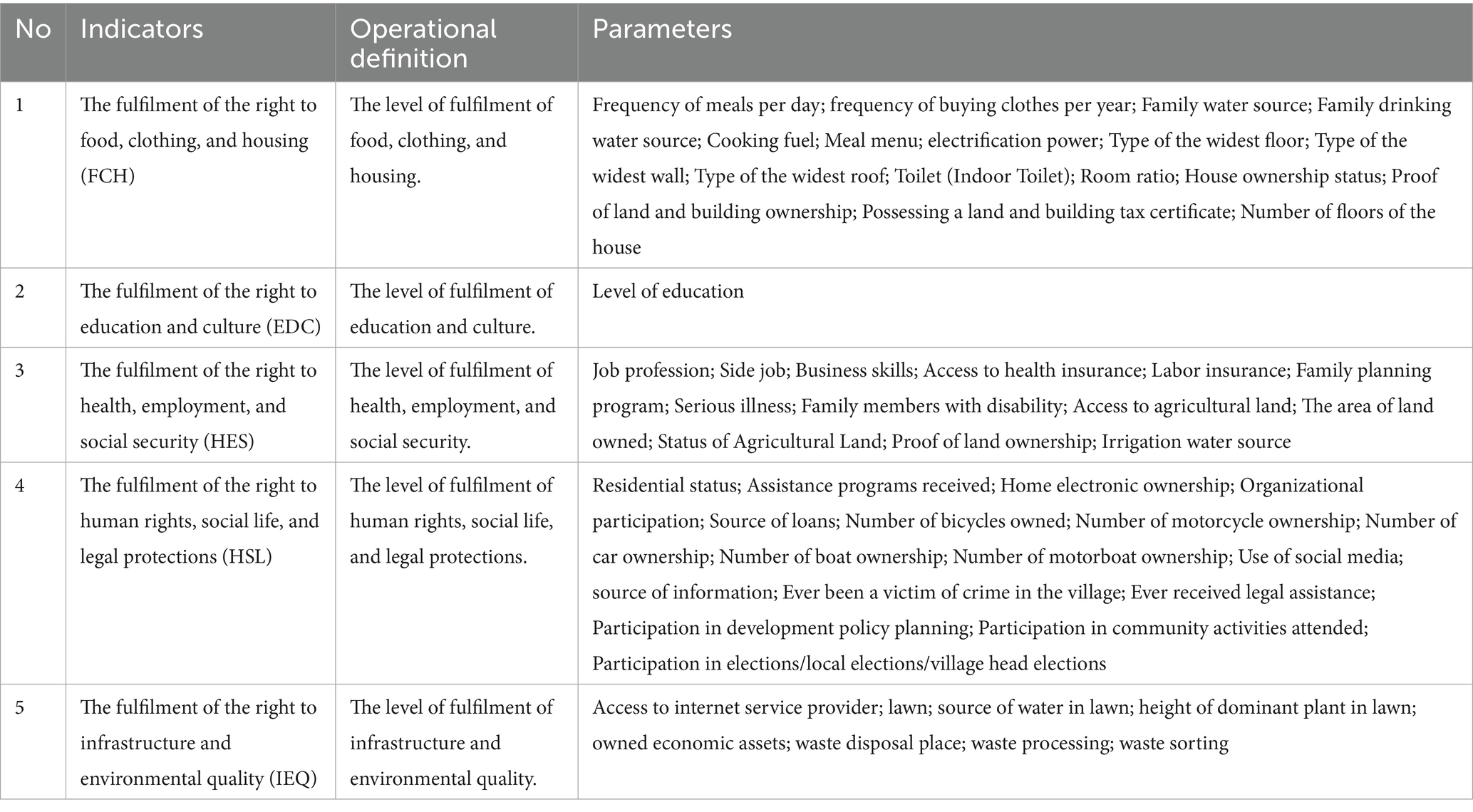

This research calculates the PWI, measured by five indicators, as stated by Sjaf et al. (2020) and Sjaf (2023). For each indicator, the researchers developed operational definitions and parameters as follows (Table 3).

3 Result

This research measures the quality of village democracy and the level of community welfare in the three studied villages. First, there is an analysis of the VDI, which uses eight main indicators to rate the quality of democracy. Second, there is an analysis of the PWI, which uses five main indicators to rate the level of welfare. Third, there is an analysis of the correlation between VDI and PWI to see how village democracy affects people’s welfare.

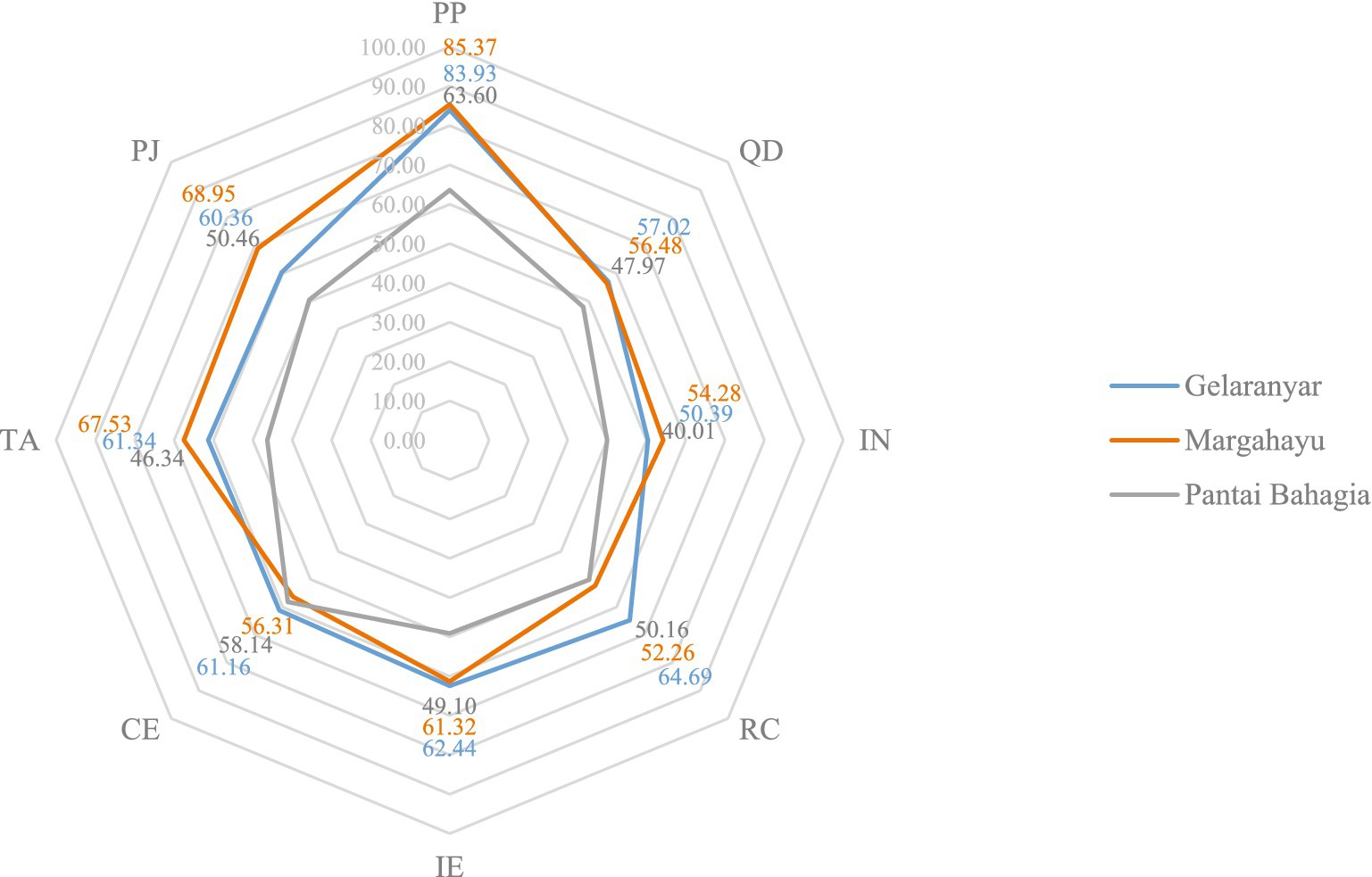

3.1 Village democracy index (VDI)

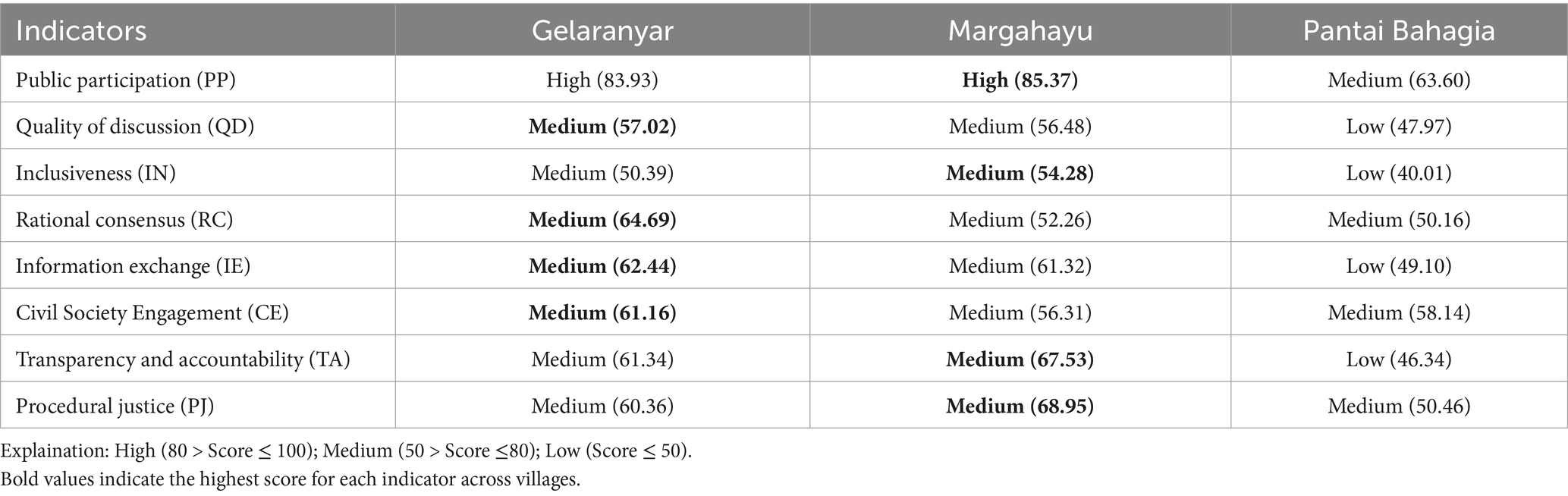

The results of the Village Democracy Index (VDI) reveal notable differences in public participation across the three villages, reflecting varying levels of engagement in democratic practices (Figure 2). Margahayu stands out for its high levels of voter engagement, where residents consistently participate in elections, demonstrating both awareness and voluntary involvement. In contrast, Gelaranyar also shows significant participation, though a small portion of residents are influenced by external pressures, indicating some challenges to achieving fully free and fair participation. Pantai Bahagia shows a stark difference, with much lower conscious participation due to coercion and hesitation among voters. This disparity is largely driven by the pervasive practices of money politics and the politicization of social assistance, which significantly affect the quality of the democratic process. Despite high voter turnout in Pantai Bahagia, the influence of transactional politics undermines the integrity of the process, highlighting that high participation does not always equate to healthy democracy, especially in more marginalized villages.

The Quality of Discussion Indicator (QD) reveals significant variations in community engagement across the three villages. In Gelaranyar, residents show the highest level of participation in fact-based discussions, indicating greater involvement in informed debates. Meanwhile, Margahayu and Pantai Bahagia show relatively lower participation, suggesting that opportunities for structured and evidence-based dialogues may be more limited in these villages. In terms of equal opportunities in discussions, Gelaranyar again leads, with a higher percentage of residents feeling that discussions are accessible to all, while Margahayu and Pantai Bahagia face challenges in ensuring equal participation. This difference in openness correlates with the quality of public discussions in the villages. Margahayu and Gelaranyar benefit from better access to village policy information, which encourages more active and objective input in the decision-making process. On the other hand, in Pantai Bahagia, limited access to information hampers community participation, and the dominance of village elites further restricts the diversity of voices heard, resulting in policies that may not adequately reflect the broader community’s needs.

The Inclusiveness Indicator (IN) highlights a significant disparity in the level of representation and participation among the three villages. Margahayu stands out for its higher level of inclusivity, where a greater proportion of minority groups feel they have equal opportunities in village politics. In Gelaranyar, while inclusivity is also relatively good, there are still notable barriers to full representation. Pantai Bahagia, however, faces considerable challenges, with fewer residents, particularly those from minority groups, feeling adequately represented in the decision-making process. This difference in inclusivity is closely tied to the influence of votes. In Pantai Bahagia, many residents feel that their voices are not given enough consideration in the formulation of village policies, a sentiment not shared to the same extent in Gelaranyar and Margahayu, where a higher proportion of residents feel their opinions are heard. These findings suggest that Margahayu has made stronger efforts to ensure that decision-making is more inclusive, giving all segments of society a meaningful role in shaping village policies. In contrast, Pantai Bahagia demonstrates that a lack of inclusivity in political processes can lead to low participation and marginalization of specific community groups.

The Rational Consensus (RC) indicator shows a clear difference in the decision-making processes across the three villages. Gelaranyar stands out for its approach, where decision-making is more rationally based, and a broader range of perspectives is considered in the process. This approach allows for more inclusive deliberation and open argumentation in policy-making. In contrast, Pantai Bahagia faces challenges in achieving consensus, with decision-making being predominantly driven by certain groups, which limits the inclusivity and fairness of the process. This often results in decisions that do not reflect the collective will of the entire community. While Margahayu shows some progress in this area, the level of rational consensus remains lower than that of Gelaranyar, indicating that while some deliberative processes are in place, they are not as fully developed or effective as in Gelaranyar.

The Information Exchange Indicator (IE) highlights a significant gap in the accessibility of village information across the three villages. Gelaranyar leads with better access to information, where residents report higher levels of transparency in the sharing of village policies. In contrast, Pantai Bahagia faces challenges in ensuring that residents have sufficient access to political information, with fewer people actively receiving updates on village matters. This discrepancy reflects a broader issue of information inequality, where Pantai Bahagia struggles to provide equal access to political and governance-related information, hindering informed participation. In comparison, both Gelaranyar and Margahayu show relatively higher levels of information access, with Margahayu demonstrating a more equitable distribution of information, though still facing its own challenges in ensuring full transparency across all community members.

The Civil Society Engagement (CE) indicator reflects the level of involvement of community groups in shaping village policies. Gelaranyar stands out with higher levels of community participation, where residents feel that their civil groups play an active role in influencing village decision-making. Margahayu and Pantai Bahagia, though also showing notable engagement, have slightly lower levels of participation. However, when it comes to the influence of civil society, Margahayu performs better, as its residents report a stronger impact on village policies compared to Gelaranyar and Pantai Bahagia. This suggests that while all three villages have some degree of civil society involvement, Margahayu benefits from a more effective and influential engagement in the policy-making process.

The Transparency and Accountability (TA) indicator shows a clear difference in how well village governments communicate with their residents. Margahayu excels in this area, with residents reporting high levels of transparency in the dissemination of policy information. This openness fosters greater trust in the village government, as residents feel more informed about how policies are formulated and how resources are allocated. In contrast, Gelaranyar also performs relatively well, but there are still some gaps in the accessibility and clarity of information, which could impact residents’ understanding of policy decisions. Pantai Bahagia faces significant challenges in this regard, with limited access to information and lower levels of transparency, leading to a sense of alienation among residents. This lack of transparency reduces their involvement in decision-making and hampers their ability to understand the direction of village development.

The Procedural Justice (PJ) indicator highlights significant differences in how fair and consistent village governance is perceived across the three villages. Margahayu stands out for having the most equitable governance, where residents feel that village rules are applied fairly and consistently, contributing to stronger trust in the system. In contrast, Gelaranyar demonstrates relatively stable procedural practices, but there is room for improvement in ensuring complete fairness. Pantai Bahagia faces challenges with discriminatory practices and the continued dominance of certain groups in decision-making, which undermines the fairness of village governance. These disparities in the implementation of procedural justice are crucial in shaping residents’ trust in the system, as those in Margahayu feel that decisions reflect the common interests of all, while in Pantai Bahagia, the lack of fairness has led to dissatisfaction and a decline in trust.

Overall, Margahayu and Gelaranyar have a higher level of village democracy compared to Pantai Bahagia (Table 4). Improvements that need to be made in Pantai Bahagia include increasing access to information, addressing practices of intimidation and intervention against the community during the election process, and better representation for minority groups in every democratic and development process in the village. Enhancing transparency and accountability is crucial to encourage residents to actively participate in village democracy. With continuous improvement efforts, it is hoped that the quality of democracy in these villages can continue to improve in accordance with the principles of inclusive and participatory democracy.

Table 4. Comparison of scores and categorization of the VDI in Gelarnayar, Margahayu, and Pantai Bahagia.

The differences in achievements on the VDI in each village reflect how the level of citizen participation, access to information, quality of discussions, and involvement of minority groups, as well as the level of transparency and fairness in village governance, contribute to shaping a better democracy system. Villages with high public participation, broad access to information, and a more transparent and inclusive governance system have higher village democracy scores. Conversely, villages that still face obstacles in terms of access to information, elite dominance, and the limited involvement of minority groups have lower democracy scores. To improve the quality of village democracy in areas with lower scores like Pantai Bahagia, it is necessary to enhance access to information, strengthen transparency, and make efforts to increase the participation of minority groups in decision-making. With increased transparency and openness, residents become more active in village democratic participation, so the policies produced truly reflect the needs and interests of the entire community.

3.2 People’s welfare index (PWI)

The PWI is measured based on five main indicators. Each indicator has specific parameters that reflect the dimensions of welfare in various aspects of community life. This analysis aims to provide a more profound understanding by considering the basic data that has been collected for each indicator, thereby strengthening the argument regarding the welfare achievements in each village.

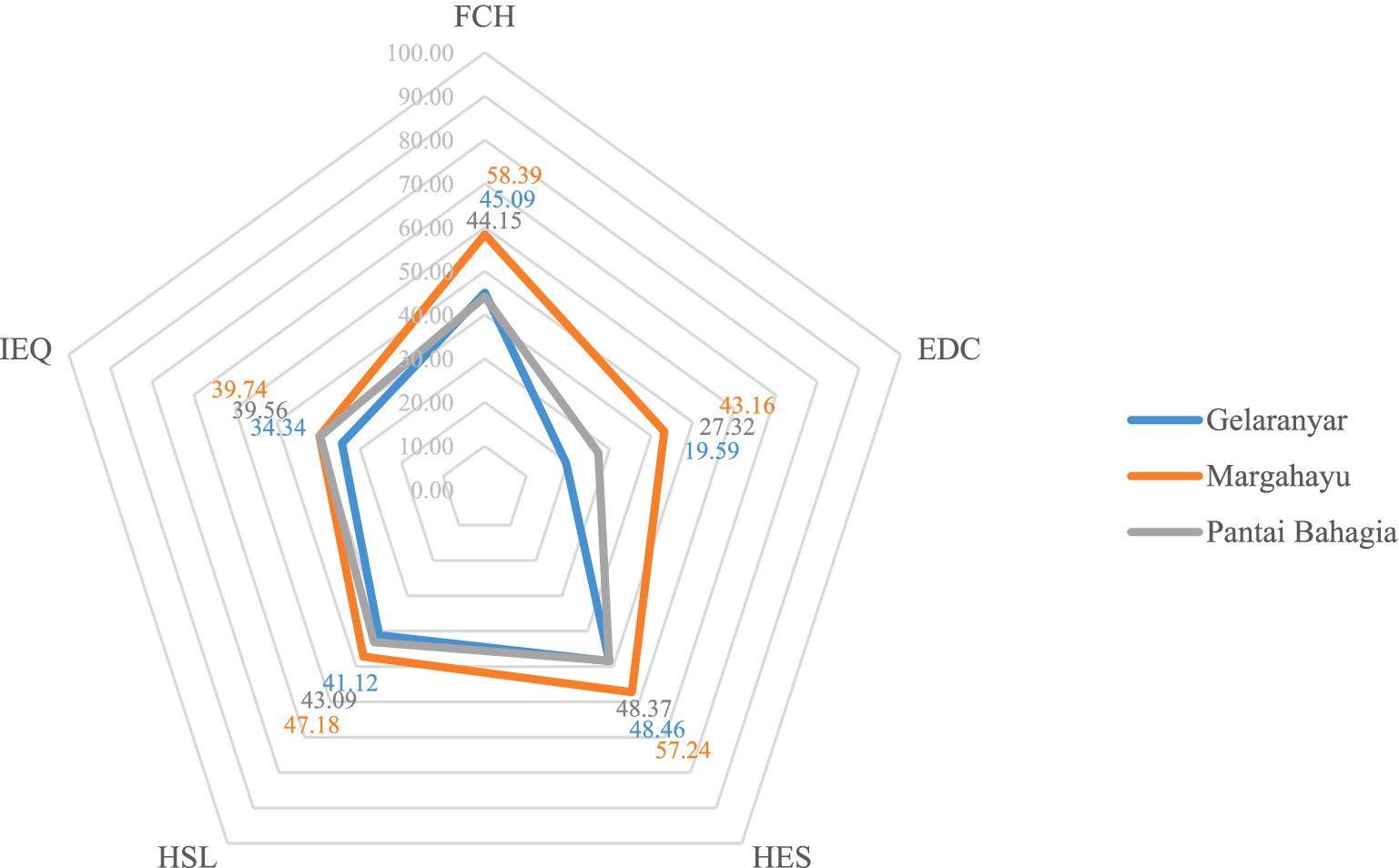

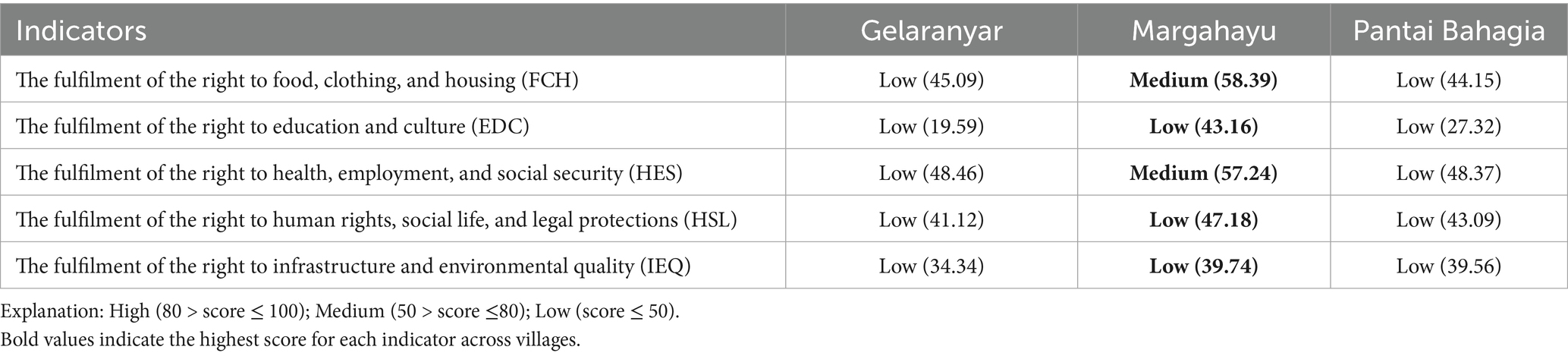

Fulfilment of the rights to food, clothing, and housing (FCH) shows how well the community can meet their basic needs. This dimension can be seen by how often people eat every day, where their families get water, what kinds of floors and roofs their homes have, and whether they own their land and pay land and building taxes. Based on the measurement of the PWI as presented in Figure 3, Margahayu obtained the highest score in this aspect with a value of 58.39, while Gelaranyar and Pantai Bahagia lagged behind with scores of 45.09 and 44.15, respectively. Specific parameters indicating the community’s access to basic needs can account for this difference. Data shows that the average frequency of meals per day in Margahayu is 3 times, the same as in other villages, but the number of houses with drinking water sources from deep wells reaches 89.5%, higher than Gelaranyar (76.4%) and Pantai Bahagia (82.7%). In terms of housing quality, Margahayu has 70.8% of houses with ceramic floors, whereas in Gelaranyar, 31.6% of houses still use earthen or wooden floors, reflecting disparities in housing quality. In terms of land ownership and tax payment, 52.6% of households in Margahayu have land certificates and pay the Land and Building Tax on time, compared to Gelaranyar, which only has 34.7%. These factors explain why welfare, in terms of basic needs such as food, clothing, and housing (FCH), is higher in Margahayu compared to the other two villages.

The fulfilment of the right to education and culture (EDC) reflects the level of achievement in formal education and access to culture in community life, which in this study is measured based on the parameter of the highest level of education or diploma held by the head of the family. In this indicator, Margahayu consistently outperforms the other villages, with Pantai Bahagia and Gelaranyar lagging behind. Based on the data, the average number of family members pursuing education in Margahayu is 1.06 per household, higher compared to Gelaranyar (0.75) and Pantai Bahagia (1.01). In addition, 42.1% of heads of families in Margahayu have a high school diploma or higher, whereas in Gelaranyar only 18.3%. The low level of education attainment in Gelaranyar indicates limited access to education or low participation rates in formal education, which may be caused by economic factors or a lack of educational facilities in the village. On the other hand, Pantai Bahagia has a higher proportion of regional language use in daily communication (63.2%), indicating a better level of cultural preservation compared to the other two villages.

The HES measures a community’s ability to get health care, employment, and have enough social security. It looks at things like the type of work, business knowledge, participation in health insurance, family planning programs, the number of serious diseases in the family, and access to farmland. In this indicator, Margahayu leads, followed by Gelaranyar and Pantai Bahagia. Based on the data, 74.6% of Margahayu’s population has permanent jobs, higher than Gelaranyar (61.2%) and Pantai Bahagia (67.5%). The high rate of permanent employment in Margahayu reflects better economic stability. Moreover, only 64.7% of Gelaranyar residents have access to health insurance, compared to 85.3% of Margahayu residents. In terms of health, 13.9% of households in Gelaranyar reported having family members suffering from serious illnesses, higher than Pantai Bahagia (9.6%) and Margahayu (7.3%), which may explain why access to healthcare services in Gelaranyar needs to be improved.

Fulfilment of human rights, social life rights, and legal protection (HSL) measures how stable the community’s social life is and how well its legal protection is. It looks at things like permanent residence status, assistance received, household asset ownership (electronics and vehicles), membership in organisations, loan access, voting, and village development policy planning. Margahayu again emerged as the top performer in this indicator, followed by Pantai Bahagia, with Gelaranyar having the lowest score. Based on the data, 91.2% of Margahayu’s residents receive government social assistance, higher than Pantai Bahagia (79.4%) and Gelaranyar (68.5%). In terms of asset ownership, 56.7% of households in Margahayu own motorcycles, compared to 38.9% in Gelaranyar. Motorcycle ownership is an important indicator of economic stability and access to transportation, which is crucial for accessing education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. In the Indonesian context, particularly in rural areas, motorcycles have long been a vital mode of transportation. They are often the primary means for families to travel to markets, schools, health centers, and other essential services. This makes motorcycle ownership an even more significant indicator of economic mobility and well-being in rural communities. In addition, the level of participation in elections is also higher in Margahayu, with 89.5% of residents exercising their voting rights in the last village head election, while in Gelaranyar only 73.8% participated.

The right to infrastructure and the environment quality (IEQ) is satisfied when the available infrastructure is of excellent quality and the environment is sustainable. This phenomenon can be seen by looking at things like internet access, home yards with water sources, owned property, and waste management systems. In this indicator, Margahayu continues to lead, followed closely by Pantai Bahagia, while Gelaranyar records the lowest performance. Basic data shows that 61.4% of households in Margahayu have access to WiFi internet, higher than Pantai Bahagia (42.8%) and Gelaranyar (27.5%). 58.3% of households in Pantai Bahagia have a system for separating organic and inorganic waste. This rate is higher than in Margahayu (49.7%) and Gelaranyar (33.9%), which shows that people in Pantai Bahagia care more about the environment. This increased focus on waste management and environmental practices in Pantai Bahagia can be linked to the village’s vulnerable coastal location, which is regularly impacted by flooding (known as banjir rob). As a community living in a region prone to environmental crises, such as rising sea levels and flooding, Pantai Bahagia’s heightened environmental awareness and practices reflect the community’s adaptive response to mitigate the impact of these ecological challenges. Their efforts to improve waste management and environmental sustainability are not only a reflection of their concern for the environment but also a strategic adaptation to survive and thrive amid the frequent environmental challenges posed by their coastal setting.

Margahayu has a better overall level of people’s welfare compared to Gelaranyar and Pantai Bahagia (Table 5). This village has higher scores on almost all indicators, reflecting economic stability, better access to basic services, and more active social participation. Gelaranyar and Pantai Bahagia have similar achievements in many indicators, with both facing challenges in education, infrastructure, and basic needs. Pantai Bahagia has very low scores in several indicators, especially in basic needs fulfilment of food, clothing, and housing (FCH) and the fulfilment of the right to education and culture (EDC), which reflect the suboptimal welfare conditions of the people.

Table 5. Comparison of scores and categorization of the PWI in Gelaranyar, Margahayu, and Pantai Bahagia.

Overall, Margahayu has better conditions in terms of social welfare, while Gelaranyar and Pantai Bahagia show areas that need improvement, especially in education, infrastructure, and basic needs fulfilment. Efforts to improve education, access to decent jobs, and the development of basic infrastructure should be the main focus of enhancing welfare in both villages. Considering the analysed baseline data, more inclusive and locally need-based policies are necessary to improve the welfare of the community in each village more evenly and sustainably.

The variation in the People’s Welfare Index (PWI) across the three villages reflects differences in planning quality and specific dimensions of development achievement. Margahayu, which records the highest social resilience score in the IDM, also shows relatively stronger human development indicators, lower housing inadequacy, and near-universal electricity access (Tables 6, 7). These outcomes are consistent with its RKPDes, which outlines targeted programs in infrastructure, health, economic empowerment, and community capacity building, suggesting a planning process that is both data-informed and attentive to local priorities. Gelaranyar, although classified as a developed village in the IDM, presents comparatively lower human development figures and higher housing and electricity deficits. This pattern aligns with the broader and less operational nature of its RPJMDes, which may limit the translation of plans into measurable outcomes. Pantai Bahagia, with a developing status in IDM and moderate environmental resilience, shows the lowest social and economic resilience scores, alongside higher unemployment, greater income inequality, and notable gaps in adequate housing and electricity coverage. These findings suggest that while IDM scores provide a useful composite measure, they may not fully capture intra-village disparities or the household-level conditions revealed by DDP. Overall, the evidence indicates that villages with operational and concrete development plans formulated in alignment with local needs, are more likely to achieve stronger and more balanced development outcomes.

3.3 The correlation of village democracy with people’s welfare

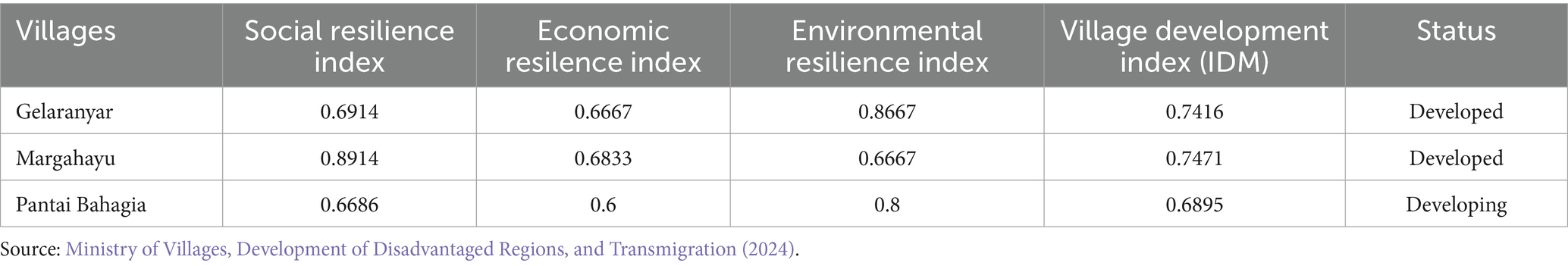

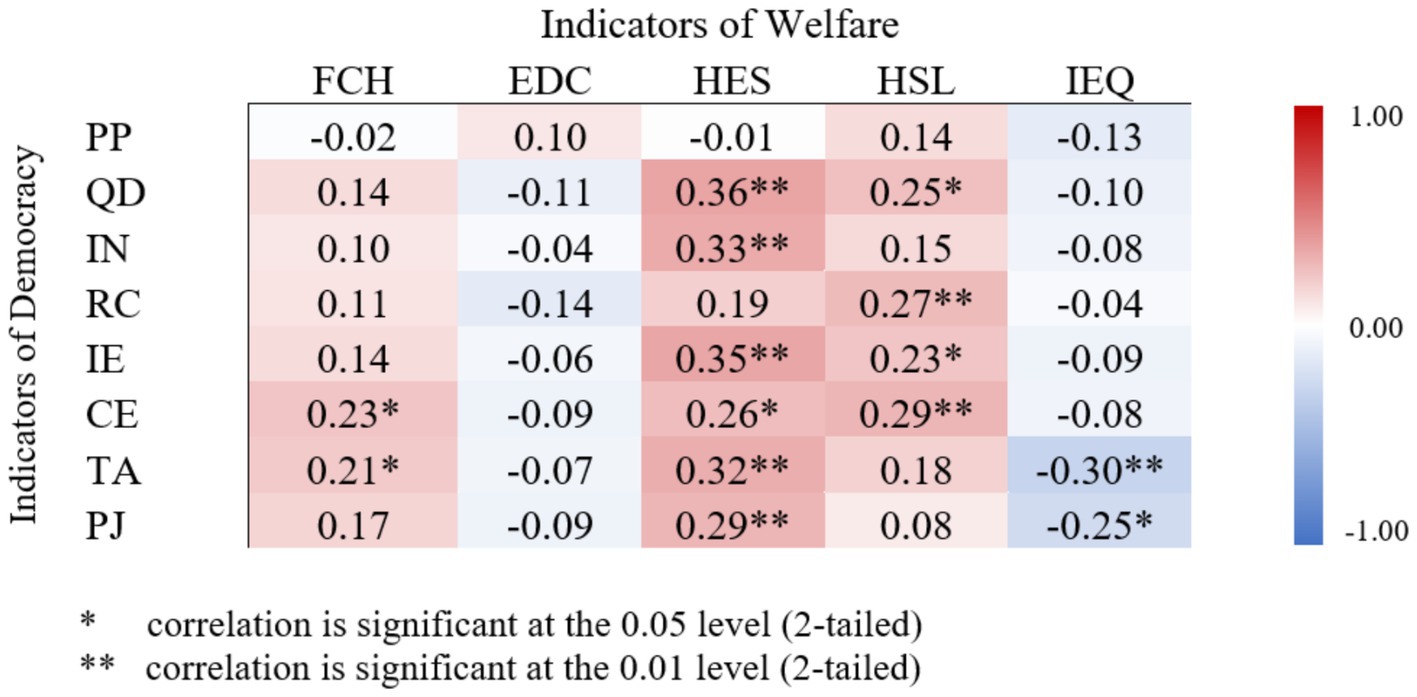

This research conducts a correlation test between village democracy indicators and people’s welfare indicators in Gelaranyar, Margahayu, and Pantai Bahagia Villages. The correlation test was conducted separately for each village. This was done to identify which indicators are correlated with each other in different contexts in each village. A color scale diagram visualises the results of the correlation tests from each village. Here is the correlation between the village democracy indicators and the people’s welfare indicators in Gelaranyar village (Figure 4).

The results of the correlation test between village democracy indicators and people’s welfare indicators in Gelaranyar Village suggest that there is a positive relationship between the level of village democracy and certain dimensions of welfare. Specifically, the Rational Consensus (RC) indicator shows a positive correlation with the fulfilment of rights in health, employment, and social security (HES), which points to the importance of inclusive and structured decision-making. However, it is important to note that this correlation does not necessarily imply a direct cause-and-effect relationship. Other factors, such as the availability of resources, local governance capacity, and external support, may also play significant roles in improving welfare outcomes.

Field observations in Gelaranyar reveal that various community members, including residents, religious leaders, and village officials, engage in Syahriahan, a monthly study session that fosters dialogue on both religious matters and local issues. In these meetings, community members address issues such as the sustainability of livelihoods, road infrastructure development, and health services. This suggests that participatory spaces like Syahriahan provide platforms for constructive deliberation, which may contribute to enhanced community engagement and shared understanding of development priorities. However, it is also crucial to consider that the effectiveness of such deliberations depends on how well the community’s needs are represented and addressed, and whether the outcomes align with equitable welfare goals.

"Every month, the Kyai/religious leaders from each mosque in the village, together with the government, regularly hold a monthly sermon in the village hall, attended by all residents, both men and women from all hamlets, not only to learn about Islam but also to discuss development issues in the village. Alhamdulillah, mutual understanding has been built from this meeting” (DHT—Chairman of the MUI Village of Gelaranyar).

In addition, rational consensus (RC) also has a positive correlation with the fulfilment of human rights, social life, and legal protections (HSL). This finding shows that decisions built through consensus based on rationality are followed by guarantees of social life, legal protection, and human rights for the village community.

Furthermore, the correlation test results also show a positive correlation between the procedural justice (PJ) indicator and the fulfilment of needs for human rights, social life, and legal protections (HSL). Procedural justice in village decision-making affects the fulfilment of social rights, legal protection, and human rights. Procedural justice instills a sense of trust in the community towards the existing system. This approach ensures that justice in the village decision-making process and the enforcement of village regulations can strengthen public trust and maximise social welfare. There are several village legal products that have been formed and implemented, namely village regulations on 1,000 koin as a program to alleviate poverty in the village that requires all families in the village to contribute IDR500 per week or whenever a disaster occurs to the residents. The village distributes the accumulated contributions, totalling IDR1,500,000 per month, to impoverished residents or families facing misfortunes. Poor families can provide assistance in the form of cash donations or livestock breeding. Other village legal products include the determination of poor village families, conducted participatively based on accurate data (DDP). This database of poor families serves as a reference for the distribution of various social assistance programs originating from the central, provincial, and district governments, as well as from village fund budgets.

"The provision of assistance in the 1000 koin program is aimed at the poor families in the village in a fair manner. We compare data from the central government with data that the village has (Data Desa Presisi). Poor families who have not yet received assistance from the central government are the target of the 1000 koin program, which is based on recommendations from poor families identified through the Data Desa Presisi” (DNI—Head of People's Welfare of Gelaranyar Village).

There is something interesting from the correlation test results, namely the existence of a negative correlation between the village democracy indicator and the people’s welfare indicator. Negative correlation indicates an inverse relationship between two indicators, where an increase in the democracy indicator tends to be accompanied by a decrease in certain dimensions of welfare. The Civil Society Engagement (CE) indicator with the Fulfilment of Rights to Infrastructure and Environmental Quality (IEQ) has a negative correlation. Furthermore, transparency and accountability (TA) in the decision-making process for developing Gelaranyar village have a negative correlation with the fulfilment of infrastructure and environmental needs (IEQ) for the community. This is caused by a conflict in development priorities that places environmental sustainability programs at the lowest priority. For example, waste management in the village of Gelaranyar has not been well-regulated, with most villagers burning their household waste, which has the potential to pollute the environment and public health. Waste management in Gelaranyar Village is also hindered by the county road infrastructure, which has not yet been developed in several areas. The condition of the road infrastructure, which is still rocky and unpaved, poses an obstacle in the transportation and management of household waste in Gelaranyar Village.

The results of this study also show a positive but weak correlation between Public Participation (PP) and the fulfilment of the right to education and culture (EDC), as well as a negative but weak correlation between discussion quality (QD) and the fulfilment of the right to infrastructure and the environment (IEQ). This suggests that the public’s role in decision-making may not have been effectively directed towards the fields of education and culture. This occurs because the process of village and hamlet deliberations may not always be based on actual and accurate information and data regarding the conditions of education, infrastructure, and the living environment in the village. Public discussions in village or hamlet deliberations may sometimes be based on the subjectivity of representatives, often biased towards the interests of village elites, without prioritising aspects of educational rights as well as community infrastructure and environmental conditions.

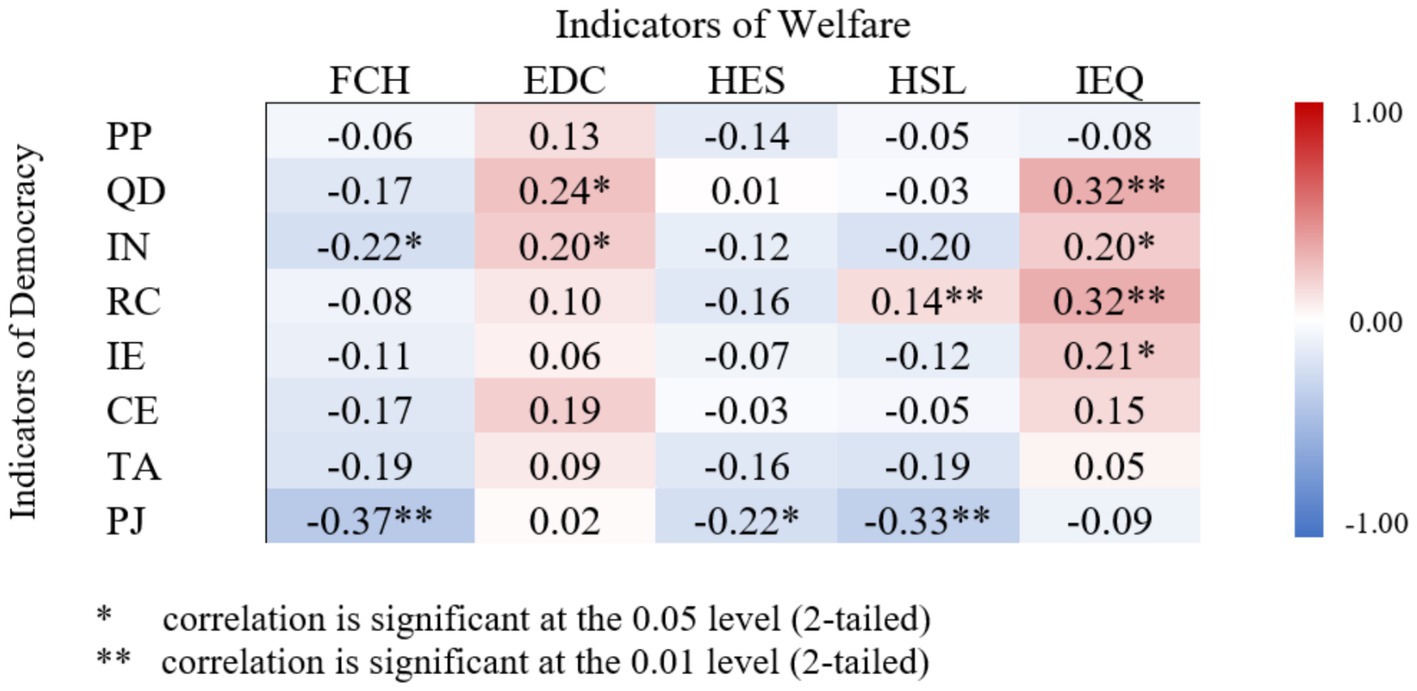

Meanwhile, the results of the correlation test between village democracy and the welfare of the people in Margahayu Village show a positive correlation between the quality of discussion (QD) and the fulfilment of basic needs for health, employment, and social security (HES); a correlation between community engagement (CE) and the fulfilment of rights to human rights, social life, and legal protections (HSL); and a correlation between transparency and accountability (TA) and the fulfilment of rights to health, employment, and social security (HES) (Figure 5). This evidence suggests that public discussions conducted during deliberations at the hamlet or village level may address issues of health, employment, and social security, though the extent of their effectiveness can vary across different contexts and may depend on local dynamics. The results of the observation show that health and social security issues receive significant attention from the village government. In a meeting in one of the hamlets in Margahayu, the issue of residents with mental health disorders who have no family to support them was discussed. The village government, along with other community members, sought a solution for the livelihood of these residents by channelling them to a social foundation owned by other villagers. Another case involves a poor family experiencing mental health issues in another hamlet, which also received attention from the village government and other community members. This attention included covering their daily food needs, providing health insurance for the residents, and implementing a housing repair program. The implementation of this policy involves a deliberation process at the hamlet and village levels, where citizens participate in both the planning and implementation stages. Village and hamlet deliberations provide greater space for civil society participation in the decision-making process, which can strengthen social protection, health, and human rights.

"It has been 5 years since the Head of Margahayu Village has served, providing excellent attention to poor and mentally ill families. The village government has provided assistance for health insurance participation and home repairs. Neighbors also give daily food to these poor and mentally ill families" (ERT—Head of RW 5 Margahayu Village).

The negative correlations found in our study suggest an inverse association between certain welfare dimensions and higher village democracy scores. For instance, greater transparency and accountability (TA), as well as more rigorous procedural justice (PJ), are linked to lower outcomes in infrastructure and environmental quality (IEQ). While these findings do not imply causation, they may indicate practical challenges in aligning democratic processes with infrastructure delivery. Supporting this, Margahayu Village demonstrates moderate levels of TA and PJ, yet scores low on the IEQ dimension of the People’s Welfare Index. Although road access is relatively adequate, waste management remains underdeveloped, with most households still relying on open burning. These observations point to the importance of balancing democratic governance with effective service delivery, particularly in addressing environmental needs in rural areas.

The study also found a weak link between a number of indicators. For example, there is a weak negative correlation between public participation (PP) and meeting basic needs for food, shelter, and clothing (FCH), and a weak negative correlation between rational consensus (RC) and meeting the right to education and culture (EDC). This evidence indicates that public participation in elections, regional elections, or political processes in the village does not correlate with the fulfilment of basic needs, especially in terms of clothing, food, and shelter. Similarly, the rational consensus that takes place in public spaces, such as village and hamlet meetings, may not have consistently focused on issues of education and culture. One possible explanation is that educational attainment in Margahayu Village is relatively high, with many residents holding high school or university degrees, which may lead to a perception that these issues are less urgent to address in deliberative forums.

Next, the results of the correlation test between democracy and the welfare of the people in Pantai Bahagia Village (Figure 6). A study found a positive correlation between rational consensus (RC) and the fulfilment of the right to infrastructure and the environment (IEQ). There is also a positive correlation between quality of discussion (QD) and IEQ. Finally, there is a positive correlation between the quality of the discussion and the fulfilment of the right to education and culture (EDC). Based on field observations, the process of village deliberations up to the village level does indeed proceed administratively in a procedural manner, but substantively, the consensus built in the deliberation process is not yet based on actual and accurate information and facts. Often, the decisions made in the deliberations are based on the interests and desires of the village elites. This trend correlates positively with the condition of infrastructure and the living environment in Pantai Bahagia village, which is also poor. The village infrastructure, such as roads, is in poor condition at several points. Tidal inundation often exacerbates the poor condition of the roads. Seawater is beginning to submerge certain areas in the western part of the village. Our fish ponds, which provide our livelihood, and several villages are now part of the ocean. The lack of road infrastructure also poses a challenge for the community in managing household waste. Most of the community burns waste and disposes of it in rivers and the sea. Such behaviour can explain the positive correlation between indicators of village democracy and the achievement of community welfare.

"We need supporting infrastructure. The community here consists of fishermen and farmers, and it is very difficult for them to deliver their catch. The economy of the fishermen is declining, the farmers are declining. In my opinion, infrastructure is a primary need, because infrastructure supports many things, not only the economy but also health; there are many cases of residents giving birth on the road. At the fastest, it takes 2 hours to reach the Bungin branch of the regional hospital. Similarly, household waste management is also hindered due to road access. Likewise, education. Here, there are 2 private junior high schools; families without vehicles have to walk to school” (AC—Vice Chairman of the Village Consultative Body of Pantai Bahagia).

Findings from this study also show that there is a negative correlation between procedural justice (PJ) and meeting the needs for health, work, and social security (HES); a negative correlation between procedural justice (PJ) and meeting the needs for clothing, food, and shelter (FCH); and a negative correlation between procedural justice (PJ) and meeting the right to social life, legal protection, and human rights (HSL). A negative correlation suggests an inverse relationship between an increase in democratic indicators and certain dimensions of welfare. Procedurally, the process of village and hamlet deliberations always involves the community through open forums, where the community can actively provide input for village development. However, after village and hamlet deliberations, there remain issues, such as the exploitation of village elite interests through the manipulation of development planning documents. This leads to a negative correlation between procedural justice, transparency, and accountability, and the welfare of the people, particularly in the areas of infrastructure and the environment. The development process in Pantai Bahagia village remains procedural, maintaining a semblance of transparency and accountability.

"The preparation of planning documents is conducted in a closed manner by the team, so the development priorities usually align with the interests of the drafting team. Sometimes we propose the construction of a 600-meter road, but only 200-300 meters get approved. Then, the proposal from another neighborhood unit (RW) is also approved for only 200-300 meters. So, the road construction was never connected. When the planning is finalized during the village deliberation, the drafting team can actually make changes without verification from the village secretary and head" (BNG—Head of Planning Division, Pantai Bahagia Village).

The study also found a weak link between a number of indicators. For example, there is a weak negative correlation between public participation (PP) and the fulfilment of social, legal, and human rights (HSL), and a weak negative correlation between information exchange (IE) and the fulfilment of social, legal, and human rights (HSL). The evidence shows that public participation in elections, regional elections, or political processes in the village does not correlate with legal protection and social life. Likewise, the exchange of information that takes place in the public sphere regarding the village’s political process has not yet optimally raised the issue of legal protection for the community. Most of the people in Pantai Bahagia village live in legal uncertainty regarding their residences because these areas are classified as forests. This is what causes uncertainty in other socio-economic aspects of the Pantai Bahagia Village community.

4 Discussion

The results of this study show that village democracy has a complex relationship with the welfare of the people in rural Indonesia. In general, villages with a higher level of deliberative democracy and rational consensus-based governance tend to have higher levels of welfare, especially in access to health, employment, and social security. However, this relationship is not always linear, as there are several paradoxes and structural barriers that hinder democracy from improving welfare.

These findings contribute to the debate in the literature regarding the relationship between democracy and welfare. Previous studies have emphasised that democracy can enhance welfare through mechanisms of accountability and more equitable resource distribution (Mulligan et al., 2004). This study adds a new aspect, though: it shows that democracy at the local level is more complicated than democracy at the national level. This is especially true when social inequality, the power of the local elite, and different types of village government are taken into account.

This research found several paradoxes in the relationship between village democracy and welfare. In certain villages, the effectiveness of infrastructure and environmental development inversely correlates with increased transparency and accountability. This phenomenon occurs because the increased oversight mechanisms and administrative procedures can slow down the implementation of development programs, especially when there are conflicts of interest among local actors (Knutsen and Rasmussen, 2020). These findings indicate that transparency and public participation need to be balanced with efficient governance to avoid hindering the implementation of development policies. Although political participation in some villages is high, it is often driven by transactional politics, such as the provision of money or social assistance as tools for mobilising votes (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., 2012). This phenomenon weakens the quality of democracy because community decisions are more influenced by short-term interests rather than data-based deliberation and the actual needs of the community. As a result, democracy, which should be a tool for improving welfare, instead reinforces patterns of exclusion and inequality (Szikra and Öktem, 2023).

Villages that have strict procedural rules in decision-making often experience delays in implementing welfare policies. Procedural justice that is too formalistic can reduce flexibility in responding to the urgent needs of the community, especially in the context of poverty and social access (Shammas, 2024). This study indicates that a balance is needed between procedural justice and the flexibility of local policies so that democracy remains inclusive without hindering the effectiveness of village development.