- 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, Masaryk University, Brno, Czechia

- 2Mass Communication Department, Gulf University for Science and Technology, Hawally, Kuwait

- 3College of Business and Economics, American University of Kuwait, Salmiya, Kuwait

Introduction: The Arab Spring uprisings (2010–2011) brought renewed attention to the political agency of women in the Arab world, often referred to as the “Twitter” or “Facebook” revolution due to the prominent role of social media. This study explores whether the type and format of news media consumption are significant predictors of political attitudes and behaviors among Arab women.

Methods: Using data from the 2013–2014 wave of the World Values Survey, we conducted statistical analyses to investigate the relationships between media exposure (categorized as vertical and horizontal media) and political attitudes and actions among Arab women.

Results: Findings indicate that both vertical and horizontal media formats significantly predict political attitudes. Notably, horizontal media use (e.g., social media and peer-to-peer platforms) was associated with more non-traditional political views. Additionally, consumption of internet-based news correlated strongly with increased political involvement. However, demographic variables, as well as perceptions of social institutions and political processes, exerted a stronger influence on political behavior than media type alone.

Discussion: The results suggest that while media choice plays a meaningful role in shaping political attitudes among Arab women, structural and institutional factors remain more decisive in motivating political action. These findings contribute to a nuanced understanding of media’s role in political mobilization in post-Arab Spring societies.

1 Introduction

The Arab Spring, a series of pro-democracy uprisings that swept across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region between 2010 and 2011, was sparked by governments’ failure to respond adequately to the growing demands of political inclusion, good governance, job creation, and inclusive growth (Alqatan et al., 2025; Ogbonnaya, 2013). The term “Arab Spring” was coined by the media to refer to the People’s Spring Revolutions that occurred in Europe in 1848 (Grinin and Korotayev, 2022). The first Arab protest, the “Jasmine (or Dignity) Revolution” of Tunisia, was triggered by the self-immolation of a young fruit seller named Mohamed Bouazizi, who was frustrated by persistent demands for bribes from local officials (Bayat, 2021).

Women played a pivotal role in the Arab Spring, serving as “a causal factor in movements for democratic development” (Moghadam, 2018, p. 2). Multiple studies have documented the high level of agency displayed by women in protests that resulted in the overthrow of regimes in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and Yemen (Bayat, 2021; Grinin and Korotayev, 2022). For example, the resulting deposition of Tunisian President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali inspired the youth-led Egyptian Uprising of 2011, which saw armed forces and ordinary men assaulting women protesters, eventually leading to the toppling of Egyptian President Ḥosnī Mubārak (Abouelenin, 2022). In Libya, the Benghazi women’s protest, sparked by the arrest of the human rights lawyer Fethi Tarbel, led to the violent overthrow of strongman Muammar al-Qaddafi (Jurasz, 2013).

Although the Arab Spring uprisings of 2010–2011 led to the toppling of regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, and Libya (Al-Tamimi et al., 2020), they did not result in the anticipated political transformation of the MENA region, in which democratically elected systems would replace authoritarian regimes and improve the conditions of disenfranchised citizens, especially women (Abouelenin, 2022; Edam et al., 2024; Zoubir, 2020). The divergent economic grievances and social dynamics that led to these revolutions also played a role in the divergent outcomes. In Egypt, for instance, the first democratically elected president, Mohammed Morsi, was ousted, imprisoned, and replaced by General Abdelfattah El-Sisi, resulting in the return of military rule (Abouelenin, 2022). In Tunisia, class divisions continued to be a source of conflict, while Libya and Yemen were mired in protracted civil wars instigated by remnants of previous regimes and religious-sectarian figures (Abouelenin, 2022; Edam et al., 2024; Zoubir, 2020).

This study fills a gap in the existing literature by examining the post-uprising situation in the MENA region regarding Arab women, particularly whether their political attitudes and actions maintained the peak achieved during the Arab Spring uprisings or if they waned and allowed remnants of previous regimes and religious-sectarian figures to hijack the changes (Allinson, 2022; Bayat, 2021; Grinin and Korotayev, 2022). To achieve this, the study analyzes the 2013–2014 survey data from the World Values Survey of Arab women’s politics during the post-Arab Spring uprisings. These politics include attitudes and actions. The examined Arab women’s political attitudes are interest in politics, their perceptions about the importance of politics to them, their perceptions about the efficacy of a democratic role, and their attitudes toward gender egalitarianism. We also examined Arab women’s political actions in terms of voting in elections and political involvement.

Since social media played a significant role during the Arab Spring, leading to the epithet “Twitter or Facebook Revolution” (Blagojević and Šćekić, 2022; Jamil, 2022; Moore-Gilbert and Abdul-Nabi, 2021), this study aims to employ the Uses and Gratifications (U&G) perspective and Marshall McLuhan’s conceptualization of “The Medium is the Message” to examine the impact of different vertical and horizontal media news and information on various Arab women’s political participation. U&G is an audience-centered perspective that examines the type of media content used by people, which influences their attitudes and beliefs. On the other hand, “McLuhan’s theory of “The Medium is the Message” is a medium-centered perspective that explores the ways in which the attributes of a medium affect people’s attitudes and beliefs.

Accordingly, Arab women’s politics are examined as predicted by news and information received from vertical media that consist of television and newspapers and horizontal media that consist of mobile phones and the Internet. In addition, the influence of these news media is compared to the influence of religiosity as well as various perceptions and confidence levels in governmental agencies and institutions. It is pertinent to examine the emancipatory function of the media in women in the region. Therefore, the second objective of this study is to explore how women’s political activism through the use of news and information on various media platforms can help reconfigure overwhelmingly male-dominated Arab political realities.

This study examines Arab women’s politics in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and Yemen, mainly because uprisings caused the toppling of regimes in these countries. Although North African countries such as Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya are often studied comparatively, Yemen was included in this study because of the unrest and uncertainty that led to subsequent civil wars. The Arab Spring involved many countries, but only Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and Yemen toppled their regimes (Moghadam, 2018). In North Africa, Egypt, with a population of 100 million, is considered the heart of the Arab world, while Tunisia, with a population of 12 million, was the starting point of the Arab Spring. Libya, with a population of 7 million, is encircled by the Mediterranean Sea and six Arab-African countries, whereas Yemen, with a population of 29 million, is located on the southern Arabian Peninsula and is surrounded by Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the Arabian and Red Seas. Cooke (2016) noted that women were highly visible during the uprisings in all these countries.

2 Literature review

2.1 Uses and Gratifications: the power of media information

The Uses and Gratifications (U&G) theory is an audience-centered approach that examines how users utilize media, rather than how the media influences them (Al-Kandari and Hasanen, 2018). Originally designed to understand why people use media, U&G was later incorporated into media effects research to examine media exposure as a variable. This theory suggests that individuals seek different gratifications from the media based on their social conditions, personality traits, and abilities, resulting in diverse media usage patterns and effects (Al-Kenane et al., 2025; Bawack et al., 2023; Falgoust et al., 2022).

McLuhan’s (2017) work on media effects and culture has had an impact on the U&G theory. His often-quoted “The Medium is the Message” suggests that media technologies’ impact on society and culture is profound and goes beyond their content. McLuhan’s key argument is that the medium itself shapes how messages are received, perceived, and understood as much as the content of the message, if not more. He further argues that new media technologies create new sensory environments that alter the way people interact, think, and communicate with one another, as exemplified by television during the Golden Era, when many modern homes rearranged their living area around the television set, making it the focal point of social interaction. This demonstrates that the effects of the medium are not confined only to its content but also to the way the content is delivered, as well as to how social relationships are structured as a result of the medium.

U&G theory, when applied to the context of political news and information, implies that individuals use the media to satisfy their political needs. Examples of such needs include seeking information, expressing users’ opinions, and the availability of opportunities to participate in political activities. U&G theory assumes that different individuals use media for different political gratifications, such as entertainment, surveillance, or social interactions. This theory is useful for understanding media usage patterns across individuals and cultures. It also shows how the media affect political attitudes and actions, which would differ depending on the media’s motivation and context.

This study specifically examines the use of media for political news and information and its effects, as this has been highlighted in previous research (Al-Kandari et al., 2022; Alivi, 2023; Cho et al., 2023a; Rathnayake and Winter, 2021). The category of information-seeking is particularly relevant, as it reflects a goal-oriented audience actively searching for news and information (Chan-Olmsted et al., 2020). This “lean-forward” behavior of online information seeking has been linked to increased political knowledge and involvement in online discussions (Al-Kandari et al., 2022) as well as an increased interest in politics (Cho et al., 2023b).

The operationalization of political attitudes and actions in this study builds on previous research (Al-Kandari and Hasanen, 2018) and is informed by the U&G theory and information utility to the politics of individuals, operationalizing political attitudes and actions. Political attitudes are operationalized as personal beliefs, opinions, and perceptions of individuals toward politics, including interest in politics, perceptions about the importance of politics in life, perceptions about the efficacy of a democratic role, and beliefs in gender egalitarianism. Political actions are operationalized as socially driven behaviors exhibited in relation to political processes at a societal level, including voting behaviors and political involvement. This study categorizes the politics of Arab women as traditional, including interest in politics and the importance of politics, and non-traditional, including the efficacy of a democratic role, gender egalitarianism, voting behaviors, and political involvement, based on the cultural and political context of the region (Altourah et al., 2021). The reason why the latter is classified as non-traditional is that Arab governments hinder Arab citizens from participating in politics that have the potential to change the existing political system.

Previous research suggests that media information utility predicts political attitudes better than political actions do (Kaye and Johnson, 2002). For example, Ancu and Cozma (2009) found no correlation between seeking information online and involvement in campaigns (a form of political action), while Kaye and Johnson (2004) found other U&G functions for using the web and online bulletin boards to be more responsible for voting as a political action. Additionally, demographic and cultural indicators, such as age, gender, hometown, race, education, life satisfaction, and social trust, frequently have greater predictive power than information motives (Park et al., 2009). Curnalia and Mermer (2013) found that the affective motive of using the media was predictive of political actions, such as voting and political activism, more than the information cognitive need. However, the strongest predictor of voting was age.

Based on the literature reviewed, two important assumptions can inform the hypotheses of this study. First, the media news and information utility can predict political attitudes better than political actions (Al-Kandari et al., 2022; Alivi, 2023; Cho et al., 2023a; Rathnayake and Winter, 2021). Second, other non-media factors can compete strongly with the media and control the effects of political actions (Curnalia and Mermer, 2013; Park et al., 2009).

Regarding political attitudes, the media news and information utility can predict interest in politics and the importance of politics in an individual’s life, as increased media exposure can satisfy personal desires for such information (Kaye and Johnson, 2002). However, building personal perceptions about the efficacy of a democratic role and the value of gender egalitarianism requires more engagement with the media, such as searching for specific news and information to form opinions on these issues (Kaye and Johnson, 2002). For many Arabs who are unaccustomed to non-traditional and democratic politics, more media involvement and cognitive processes may be necessary to adopt new perspectives (Altourah et al., 2021).

Regarding political actions, the media news and information utility may have a lesser effect due to the increased physical and personal commitment required for actions, such as voting and political involvement, as well as the perception that election results are manipulated (Altourah et al., 2021). Other factors, such as demographic, economic, and social mega factors, may have a stronger influence on political actions (Curnalia and Mermer, 2013; Park et al., 2009). For example, a decision to protest may be motivated more by a desperate economic situation than by media persuasion.

The above review informs the following hypotheses:

H1: Media news and information are more likely to predict political attitudes than political actions.

H2: Media news and information are more likely to predict an interest in politics and the importance of politics than the efficacy of democratic roles and gender egalitarianism.

H3: Media news and information are more likely to predict voting intention than political involvement.

2.2 The medium is the message: the effects of horizontal versus vertical media

At the heart of McLuhan’s “The Medium is the Message” concept is the way a medium’s format, features, or attributes can have an alternative impact on audiences. This impact can be equally as important as the effects of the conveyed messages, if not more. McLuhan emphasized the technological traits embedded in a specific medium—whether text, audio, or visual—that can influence an audience through the way the medium presents news and information that, in turn, influences the way audiences perceive and understand the same message differently when they receive it from various media (McLuhan, 2017). For example, a news story reporting violent demonstrations in video format will have a more sensational impact on an audience than a medium reporting the same news story in a newspaper. Similarly, reading a book and watching a movie of the same story will lead to different impacts and give audiences different experiences. In this sense, each medium has unique qualities, characteristics, and a level of affordance that can shape people’s perceptions and attitudes differently toward the world.

When relating the concept of “The Medium is the Message” to horizontal and vertical media, it can be envisioned that both can have different impacts on audiences. Horizontal media that include online and social media encourage a democratic contribution and distribution of media content, where a wider range of opinions can be voiced by ordinary people. This can lead to different impacts on audiences compared to vertical media, where content is centrally produced from an elitist top-down approach. A review of horizontal and vertical media necessitates consideration of the distribution of power, the structural hierarchy of media, the gatekeepers of content, and the narrative conveyed in terms of deliberation, sensationalism, and populism. In short, each medium—horizontal or vertical—can shape the worldviews of its respective audience users. Based on this understanding, horizontal media, as new and alternative media to vertical media, can affect Arab society’s politics in the same manner as the printing press revolutionized information dissemination in Europe when it was first introduced.

In this context, the distinction between horizontal and vertical media reflects the different messages that lead to different political effects. Vertical media are typically one-way, top-down sources of information that provide little interaction between the source and the audience, such as traditional television and newspapers (Shaw et al., 2012). Gatekeepers and agenda setters are professional journalists who determine what information a passive audience needs to read and view based on the elite perspective and ideology of the owner, upper management, and journalists. Historically, vertical Arab media has been controlled and supervised by Arab ministries of information, with the majority of private media operating within lines delineated by Arab authorities (Al-Kandari et al., 2022). As a result, such a format of authoritarian, propagandistic, and controlled Arab vertical media may have minimal effects on politics, particularly for issues that go against the status quo, such as the value of the efficacy of a democratic role, gender egalitarianism, voting, and political involvement.

In contrast, horizontal media are characterized by fluid, two-way, or more news and information that can be molded to fit the individual media user’s personal agenda, as seen on the Internet, social media, and mobile phones (Shaw et al., 2012). People have active agency in gatekeeping and agenda-setting processes by producing and disseminating media messages that reflect their wants and demands. Prior to the Arab Spring, horizontal media were already significant in bypassing mainstream media to reach the majority of the population (Liu et al., 2021). During the Arab Spring protests, horizontal media played a critical role in transmitting anti-government perceptions and providing organization and cohesion (Blagojević and Šćekić, 2022; Jamil, 2022; Moore-Gilbert and Abdul-Nabi, 2021). It drew local and international attention and gained “outside validation and countermovement pressure” through the dissemination of “a continuous stream of text, videos, and images from the streets of the uprising directly to millions via social media technologies, and indirectly through the republication of these messages on news networks such as Al Jazeera and CNN” (Blagojević and Šćekić, 2022, p. 120). When communication devices were shut down to physically prevent journalists from reporting in Egypt, the old regime’s outdated understanding of media as a “one-way information channel” failed to acknowledge protesters’ “newfound civic identities, which could not be neutralized by cutting off communication devices” (Rinke and Röder, 2011, p. 1282). The clampdown drove people away from their devices on the streets, forcing them to rely on person-to-person communication, including the use of landlines, which was the only form of communication available to Egyptians at the time.

Overall, the distinction between horizontal and vertical media is best understood in terms of the source of information dissemination and the involvement agency each media provides to their audiences (Shaw et al., 2012). While vertical media may have limited effects on politics, particularly on issues that go against the status quo, horizontal media can play a critical role in shaping political attitudes and actions, as seen in Arab Spring protests.

Based on the above, the following hypothesis is posited:

H4: The use of horizontal news media has a more predictive effect on Non-traditional Arab political attitudes and actions than vertical news media.

3 Method

3.1 World Values Survey (WVS)

The World Values Survey (WVS) is a global research initiative that investigates the attitudes, values, and predispositions of people in over 100 nations worldwide regarding a variety of issues. Composed of scholars from various countries, the project has generated more than 300 publications in different languages based on its database, which is accessible at http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp (Inglehart et al., 2014). This study used data from the 6th Wave of the survey (2010–2014), which covered the period following the Arab Spring from 2010 to 2011. The WVS collected data from Tunisia and Egypt in 2013 and from Yemen and Libya in 2014.

3.2 Research and statistical design

3.2.1 Populations and samples

The diversity among Arab women is shaped by varying regional, cultural, religious, and political differences, as noted by Radsch (2012), with Libyan and Yemeni women being more conservative than Tunisians or Egyptians and enjoying less political freedom due to the use of military force to counter protests. Because of these differences, Moghadam (2018) suggests that women’s social participation, legal rights, and collective action capacities differed significantly across the region on the eve of the Arab Spring. However, Ibnouf (2013) argues that access to technology, especially social media, has a leveling effect across this spectrum, enabling women to participate and fully exploit their potential as change agents. The Dubai School of Government (2011) confirmed that access and technological literacy were greater barriers to social media use among women than were social and cultural constraints. Women’s political activism involves circumventing traditional barriers, aggregating and disseminating information to influence public opinion, raising awareness within their countries, and sharing information with the world (Dubai School of Government, 2011; Radsch, 2012). Access to media, especially social media, has blurred the lines between society and politics (Radsch, 2012).

WVS usually requires 1,200 individuals responding to their survey, which is considered the minimum requirement for a sample representing a country. The sample of the WVS consisted of a spectrum of demographics among people aged 18 years and older. The sampling methods are based on either probability or a mixture of probability and stratified sampling techniques. In this study, data were collected using personal interviews or phone calls to reach people in remote areas. To ensure and check data reliability, WVS professionals frequently conducted internal reliability tests during and after sampling. During interviews, the safety and anonymity of respondents are ensured.

The respondents consist of 3,148 individuals, with 1,033 Egyptian women making up 32.8% of the sample, 1,042 Libyan women (33.1%), 571 Tunisians (18.1%), and 501 Yemenis (15.9%).

3.2.2 Control variables

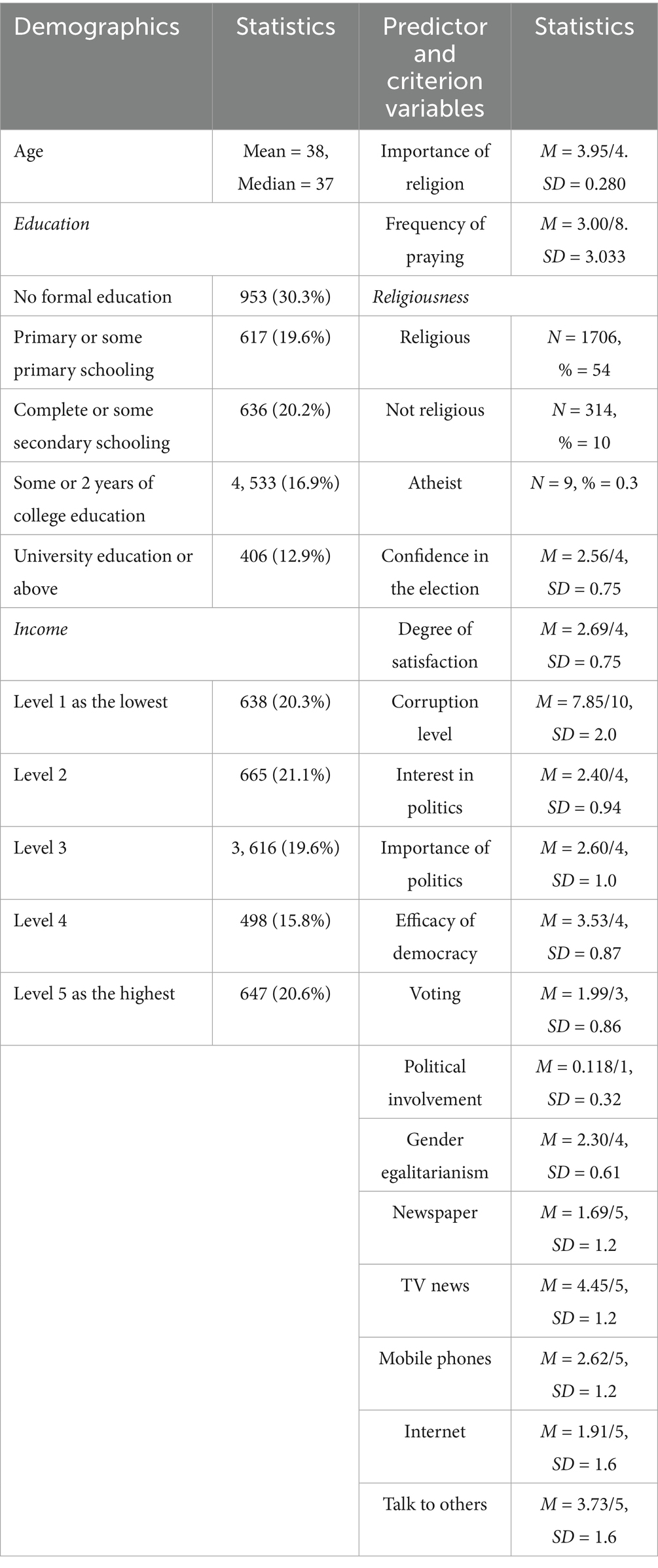

3.2.2.1 Demographics

This study emphasizes gender, age, education, and income in statistical analyses because demographics are considered the primary factors that predict and shape human beliefs, behaviors, and actions (Babbie, 2020).

The respondents provided their exact ages. Education was coded as 1 for no formal education, 2 for primary or some primary schooling, 3 for completion or some secondary schooling, 4 for some or 2 years of college education, and 5 for 4 years of university education or above. As for income, the WVS’s survey procedures required recording the income a respondent declared to a research assistant using a scale from 1 to 5 according to a bell-curve distribution of income in a country. For example, individuals with very low income would be given a value of 1 according to the income distribution sheet, to which the research assistant was supposed to refer (Table 1 includes the statistics of all variables).

As religion and politics are intertwined in the Middle East, religiosity was considered in the three variables. Attitudes toward the importance of religion in life were reported using a scale of 1–4, where 1 pointed to “Not at all important” and 4 to “Very important.” The frequency of praying was 1 for never through 8 for several times a day. For religiousness, each respondent indicated being “a religious person” as 1, “not a religious person” as 2, and “an atheist” as 3. System missing values were 1,119 (36%) (Table 1).

4 Results

4.1 Predictor variables

There are two sets of predictor variables. The first set narrows the focus to include media information sources respondents depended on for news and information: daily newspapers, television news, mobile phones, the Internet, and talking with others. Information engagement was indicated by choosing “Daily” coded as 5, “Weekly” 4, “Monthly” 3, “Less than monthly 2, and “Never” 1. Different perceptions of social institutions, political processes, and atmosphere were considered as part of the second set (Table 1).

The second set of predictor variables was related to perceptions of and confidence in various political aspects, such as confidence in different institutions, confidence in the election process, degree of satisfaction with a country’s governmental services, and level of corruption.

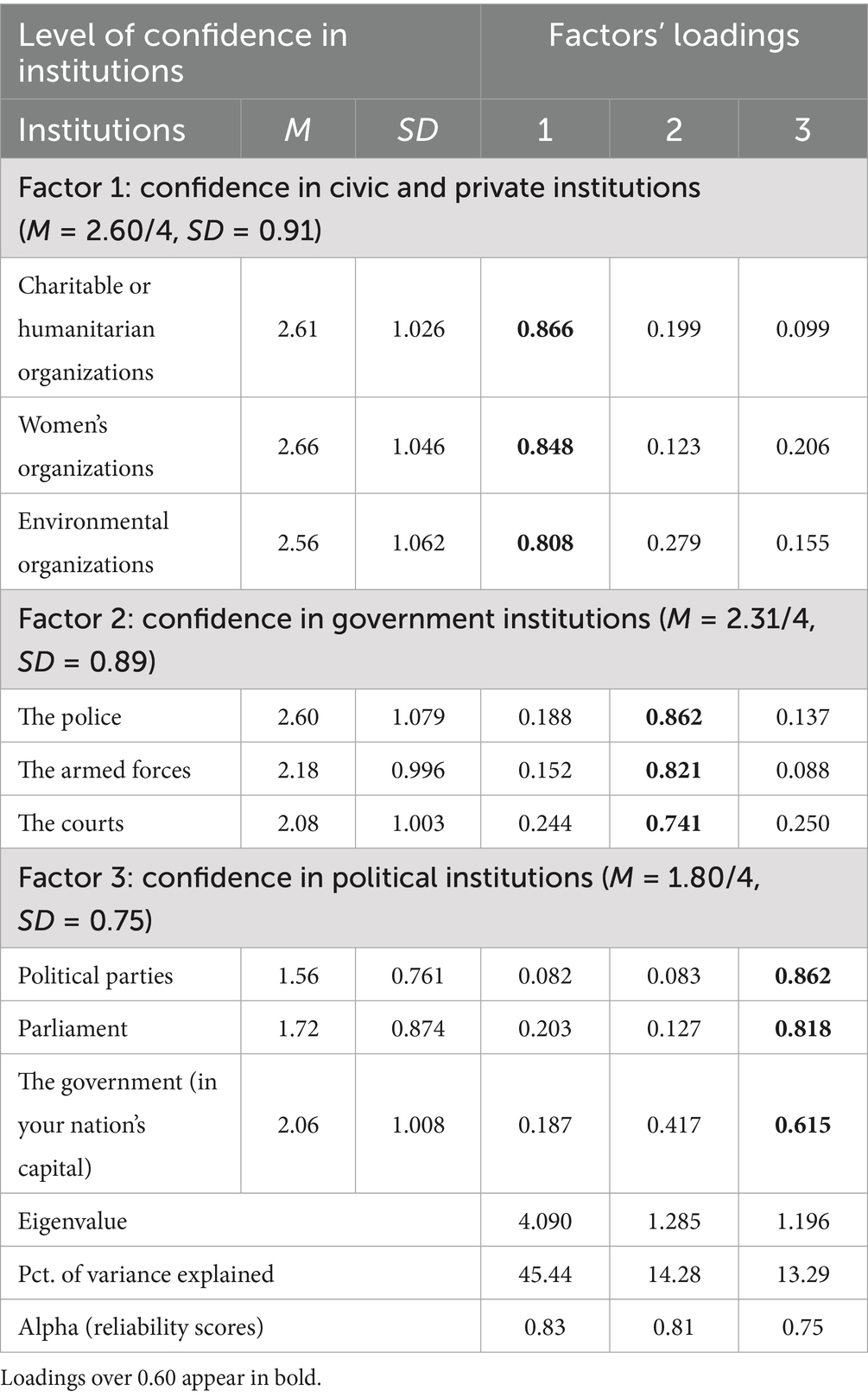

For confidence in institutions, specific sets of confidence were subjected to a factor analysis statistic using principal components with an eigenvalue of at least one for extraction and Varimax rotation. This was to group the institutions that the respondents believed belonged together. For those perceptions, respondents indicated their level of confidence employing a 4-point scale ranging from “A great deal” coded as 4, “Quite a lot” 3, “Not very much” 2, to “None at all” 1. The analysis extracted three types of confidence in institutions, together explaining 73% of the total variance. The extracted confidence levels were related to confidence in civic and private institutions (charitable or humanitarian organizations, women’s organizations, and environmental organizations), government institutions (police, armed forces, and courts), and political institutions (political parties, parliament, and government). Table 2 reports the statistics of all the factor loadings and their reliability tests.

Confidence in the election process was also a predictor. A five-statement-item index assessed beliefs in the fairness of conducting the election and whether intervention from the government was present, e.g., “Opposition candidates are prevented from running (reversed).” To express their perceptions, the options ranged from 4 as “Very often” to 1 as “Not at all often” 1. The Cronbach alpha reliability score for the index was 0.70 (Table 1).

Degree of satisfaction assessed perceptions of the quality of eight services that the governments provided, such as housing, healthcare, and schools. Respondents’ satisfaction level with the services was captured using a 4-point scale ranging from “Very satisfied” 4 to “Very unsatisfied” 1. The index recorded an Alpha score of 0.88 (Table 1).

Corruption level was another perception predictor, referring to levels of corruption in the government and private sectors as being high or low. The question items of the index were “How widespread is corruption within businesses in your country?” and “How widespread is corruption within the government in your country?” Respondents indicated their beliefs with a scale ranging from 1, indicating “High corruption,” to 10, as “Low corruption.” The alpha score was 0.80 (Table 1).

4.2 Criterion variables

The first criterion variable is interest in politics. Respondents indicated their level of interest in politics using a 4-point scale ranging from 4 as “Very interested” to 1 as “Not at all interested” (Table 1).

The second criterion variable was the importance of politics. The female respondents reported their attitudes ranging from “Very important,” 4, to “Not at all important,” 1 (Table 1).

Criterion variable 3 was an index assessing women’s perceptions of the efficacy of a democratic role to measure respondents’ belief that democracy can make a difference in their lives or bring about progress. Two question items utilized to create this index recorded a Cronbach’s alpha reliability score of 0.85. The items were “Having honest elections makes a lot of difference in your and your family’s lives” and “Having honest elections in whether or not this country develops economically.” Respondents indicated the efficacy of democracy on a 4-point scale of “Very important” 4 to “Not at all important” 1 (Table 1).

The fourth was voting in the elections. Participation in previous national elections was reported as being “Always” coded as 3, “Usually” 2, and “Never” 1 (Table 1).

Political involvement was the fifth criterion variable. Previous engagement in politics was reported as signing a petition, joining boycotts, attending peaceful demonstrations, joining strikes, or performing any other act of protest. For each choice, the respondents indicated whether they were involved. Involvement was coded as 1, whereas absence of involvement was coded as 0. The mean values of these involvements were used in the regression analysis. A total of 355 (12%) individuals reported their involvement in any type (Table 1).

Gender egalitarianism, the last criterion variable, was assessed using the five-item statement index. An example from the index was, “On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do (reversed).” Respondents expressed their opinions using a 4-point scale of “Strongly agree” 4 to “Strongly disagree” 1. This index’s alpha reliability score was 0.68 (Table 1).

4.3 Multiple linear regression

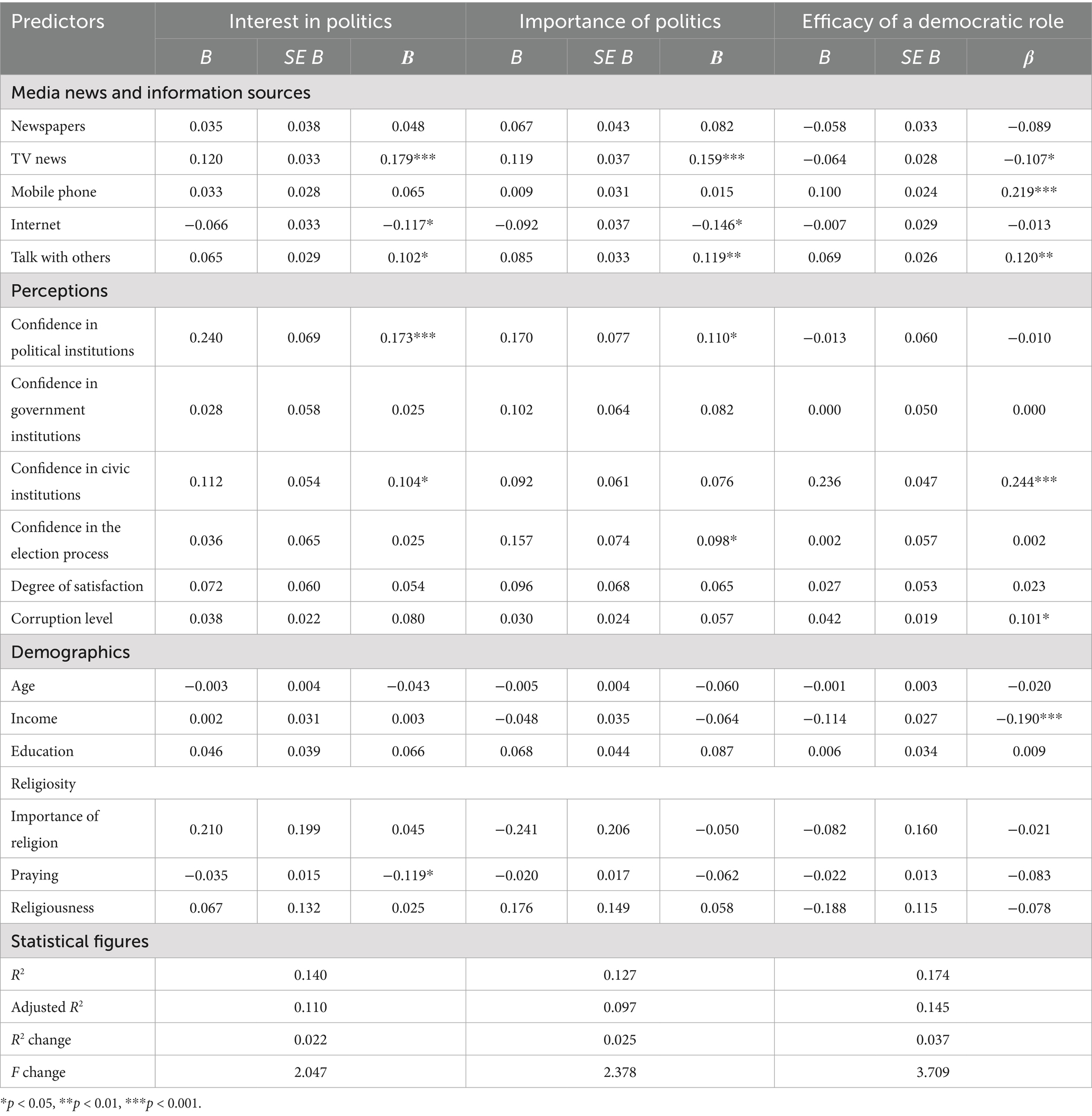

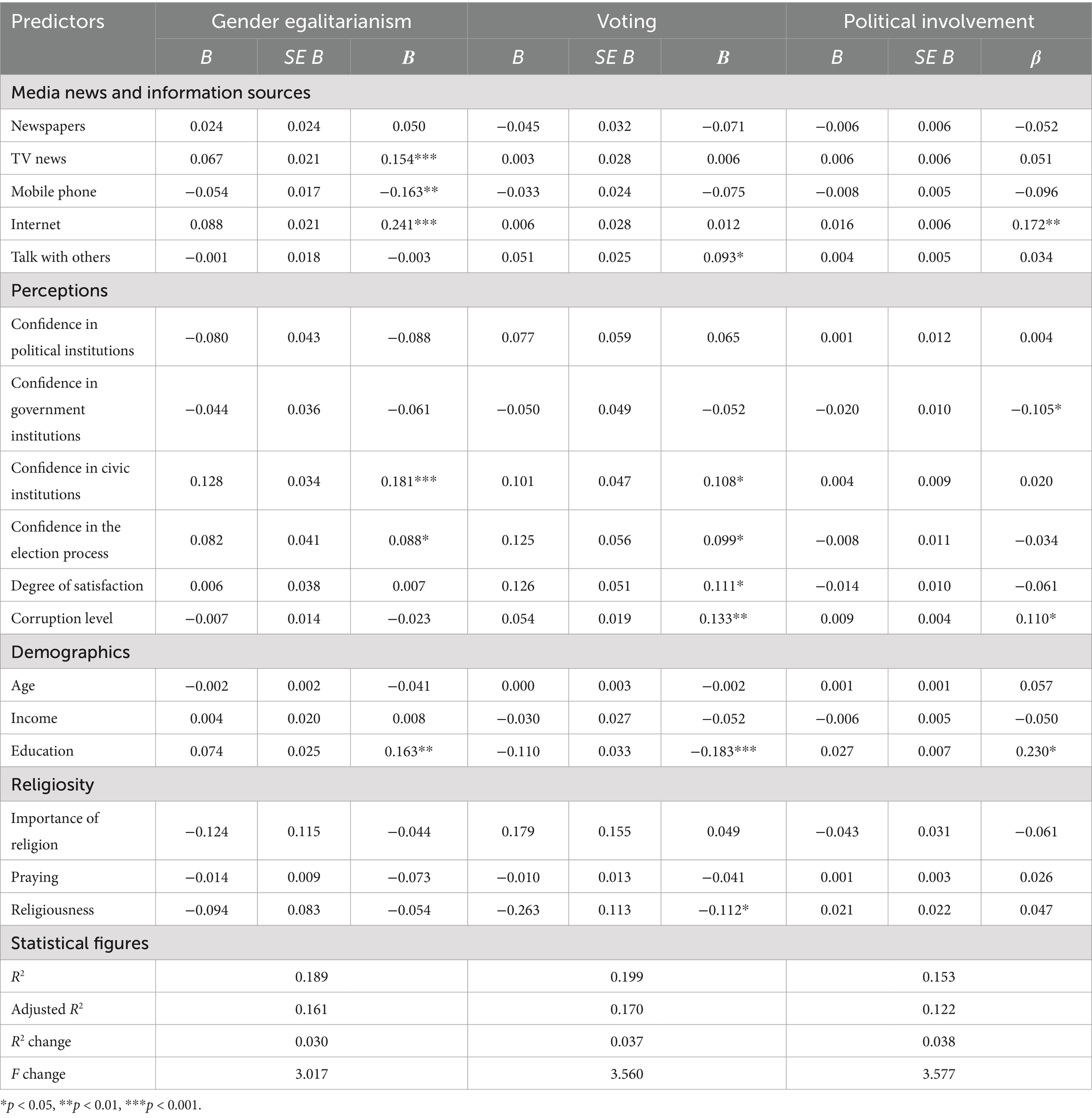

Two Multiple Linear Regressions (MLRs) were applied to the data separately on two levels. The first level included media information sources and perceptions of politics and different institutions as part of the first-level independent variables block of the MLR. The second set of variables, entered in the second block of the MLR, consisted of demographic and religiosity variables, which were treated as control variables to examine the effects of the focus variables in this study, media information sources, and the perceptions of various institutions. Each variable was analyzed in strict order against six criterion variables each time: interest in politics, importance of politics, efficacy of a democratic role, voting, political involvement, and gender egalitarianism. All data regarding the country were removed from the datasets, as we treated the sample homogeneously (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3. Multiple regression analyses of the predictors of interest in politics, importance of politics, and importance of democracy.

Table 4. Multiple regression analyses of the predictors of voting intentions, political involvement, and gender egalitarianism.

5 Findings and discussion

5.1 Predictors of political attitudes

The first MLR analysis, aimed at examining the predictors of interest in politics, was significant at the second level, which controlled for demographic and religious indicators (R2 change = 0.021, F(6, 488) = 4.684, p = 0.001). At this level, exposure to television news and talking with others positively predicted the criterion variable, whereas using the Internet for news and information was a negative predictor. Confidence in political institutions and confidence in civic institutions were significant positive predictors of political interest. Finally, the frequency of praying was a negative predictor. Table 3 shows the statistical significance of Beta scores for each predictor.

The second MLR procedure, testing the predictors of the importance of politics in the lives of these women, was significant at the second level (R2 change = 0.025, F(6, 489) = 4.190, p = 0.001). Exposure to television news, talking to others, confidence in political institutions, and confidence in the election process were positive predictors. Internet use for news and information was a new additional negative predictor (Table 3).

For the predictors of efficacy of democratic role, the MLR analysis was significant at the last level, R2 change = 0.038, F(6, 493) = 6.090, p = 0.001. Here, TV news was a negative predictor, but mobile phones, talking to others, confidence in civic institutions, and corruption level were positive predictors of the efficacy of the democratic role. Income level was found to be a negative predictor (Table 3).

The fourth MLR for the predictors of gender egalitarianism was significant at the second level (R2 change = 0.029, F(6, 492) = 6.753, p = 0.001). Exposure to TV news, newspapers, information on the Internet, confidence in civic institutions, confidence in the election process, and education were predictors of the criterion variable. Use of mobile phones was a negative predictor of gender egalitarianism (Table 4).

5.2 Predictors of political actions

The fifth MLR procedure, testing the predictors of voting intentions, was significant at the second level (R2 change = 0.044, F(6, 465) = 6.812, p = 0.001). Confidence in talking to others, confidence in civic institutions, confidence in the election process, degree of satisfaction, and corruption level were all positive predictors, whereas education and religiosity were negative predictors (Table 4).

The last MLR procedure that explored the predictors of political involvement was significant at the second level (R2 change = 0.029, F(6, 476) = 5.044, p = 0.001). Only Internet use and education were positive predictors of involvement in politics (Table 4).

From Tables 3, 4, of the 10 significant predictions (those with p values <0.05), media news and information utility predicted 9 cases of political attitudes and only one case of political action. These clearly and strongly confirm H1. Out of those 9 significant predictions of political attitudes, media information utility predicted 4 cases for attitudes of interest in politics and the importance of politics and 5 cases for the efficacy of a democratic role and gender egalitarian attitudes. Consequently, H2 and H3 were rejected.

Interestingly, perceptions of institutions and the political atmosphere and process predicted 14 cases related to the politics of individuals and 10 predicted Non-traditional Arab politics. Of those 10, 6 predicted Non-traditional Arab actions, which suggest the following: first, perceptions are a more important influence on the politics of individuals than media news and information (media news and information predicted 10 cases, and perceptions predicted 14 cases); second, perceptions are more important for predicting Non-traditional Arab politics than traditional Arab politics (perceptions predicted 10 cases of Non-traditional Arab attitudes and 4 cases of traditional Arab politics). Of the 10 non-Arab traditional political predictions, perceptions predicted more Non-traditional Arab political actions than Non-traditional Arab political attitudes (perceptions predicted 6 cases of non-Arab political actions and 4 cases of Non-traditional Arab attitudes).

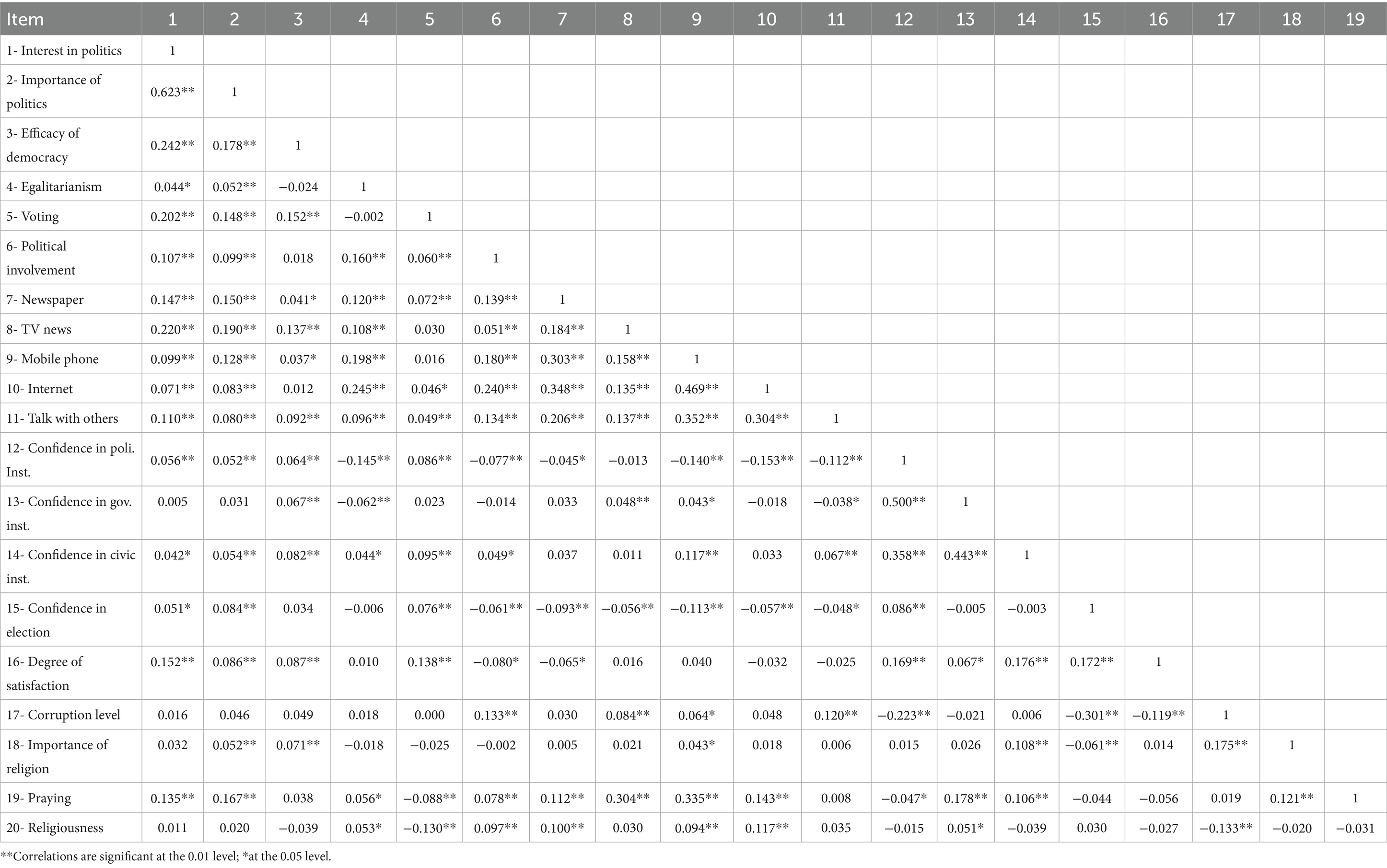

This outcome indicates the greater influence perceptions have on political actions than on political attitudes. The fact that demographics predicted Non-traditional Arab political actions, whereas no demographic factors predicted traditional Arab attitudes, confirms previous studies indicating the importance of the influence of non-media factors on political actions (Curnalia and Mermer, 2013; Park et al., 2009). These findings compel a serious need to link media effect studies to perceptions, as the media has indirect effects on people’s political attitudes and actions by creating certain perceptions that directly influence people’s politics. Future research must look for the mechanisms that construct these perceptions through the media, public opinion, and society, as these perceptions, especially those of Arab women, are currently unknown. Media is one factor, while social and religious elements also determine those perceptions. Indeed, Table 5 of the correlations between the predictor and criterion variables shows that media information and religious indicators correlate with perceptions (Table 5).

The preceding findings indicate that the media is just one of several factors influencing individuals’ political attitudes and behaviors. To fully understand these effects, future research must adopt a comprehensive multilevel approach that considers the interplay of various contextual, social, and psychological influences. This aligns with the arguments of Curnalia and Mermer (2013) and Park et al. (2009), who contend that non-media factors play a crucial role in shaping individuals’ political engagement and orientation. Even politics has to be categorized differently into attitudes and behaviors to identify the sources that influence them. This aligns with the findings of Al-Kandari and Hasanen (2018). These outcomes also align with the findings of Altourah et al. (2021), who employed both direct and indirect media effect approaches in their study, concluding that media influence can manifest either directly or indirectly depending on the context. These results also suggest that different media can have different types of effects. In line with other researchers, such as Kaye and Johnson (2002) and Ancu and Cozma (2009), this study found that different media influence women’s political attitudes and behaviors differently.

Internet news and information negatively predicted traditional Arab political attitudes, such as interest in and the importance of politics. However, it positively predicted non-traditional attitudes, such as gender egalitarianism, and non-traditional actions, such as political involvement. This suggests two things: a negative prediction of Internet information for Non-traditional Arab attitudes suggests that the politics of the Internet are unappealing to ordinary or average individuals seeking basic and traditional politics. Second, horizontal media appeals to specialized audiences with specific niches of interest (Shaw et al., 2012). Horizontal media appeals to political activists seeking extreme actions and non-traditional politics.

Finally, talking to others as a form of news and information through personal communication alone predicted 4 out of 14 (29%) cases of media information, including newspapers, TV news, mobile phones, and the Internet. Individuals in Arab societies are likely to feel more secure in discussing political matters in private, familiar settings rather than through online horizontal media, where state surveillance may be more pervasive. This same observation should compel further research to understand why horizontal media news and information predicted Non-traditional Arab attitudes but failed to predict Non-traditional Arab political actions. Horizontal media predicted Non-traditional Arab political attitudes because these attitudes correspond with an exposure activity that an Arab authority would allow. On the other hand, horizontal media failed to predict Non-traditional Arab political actions, probably because of people’s belief that accessing information that incites actions could jeopardize their safety. Arab women may feel monitored by Arab authorities when viewing serious politics, such as involvement in politics, which affects the status quo of those authoritarian regimes. Future research should consider the influence of interpersonal communication and media information on politics in the Arab world.

The previous results align with many recent studies that have established the fact that new media are transforming politics in newer ways. For many Arab women, horizontal media reflect the progressive politics that people seek out when they cannot find themselves in vertical media (Shaw et al., 2012). Horizontal media platforms offer an ideal space for politically engaged individuals to express their views and engage in online protests against perceived societal injustices (Liu et al., 2021). They can be places not only where people can express their frustration about politicians but also for people to politically organize (Blagojević and Šćekić, 2022; Jamil, 2022; Moore-Gilbert and Abdul-Nabi, 2021). Indeed, this study suggests that future research should account for the distinct political implications of vertical and horizontal media, as these forms may differently influence political attitudes and behaviors (Shaw et al., 2012).

6 Conclusion

The findings suggest that Arab women’s politics were influenced by media use, interpersonal communication, institutional trust, and religiosity. In particular, media use, especially television news, emerged as a consistent positive predictor of political attitudes, such as interest in politics, the importance of politics, and gender egalitarianism, while the Internet played a mixed role, sometimes even negatively influencing political interests and perceptions of democracy. Talking to others consistently predicted both attitudes and actions, reinforcing the enduring role of interpersonal networks in political socialization. However, confidence in institutions stood out as the most robust predictor across both attitudinal and behavioral dimensions, particularly in shaping Non-traditional Arab political engagement.

The study’s initial objective results, as depicted in Table 1, suggest a decline in Arab women’s political engagement post-Arab Spring, except for their beliefs in democratic efficacy. This decline might have contributed to post-uprising setbacks. Despite voicing a desire for democracy, women may not have steadfastly pushed for full revolutionary demands, enabling regression, such as military resurgence in Egypt and civil strife in Yemen and Libya. This observation, not a generalization, reveals the reemergence of toppled regimes, exemplified by Egypt’s military regain and the Yemeni president’s alignment with the civil war. Gulf states supported reversals in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, and Libya to safeguard their own regimes.

The study’s second objective examined how various media platforms can reshape the mostly male-dominated political landscape in the Arab world. The findings revealed that all media channels (TV news, Internet, and mobile phones) and platform types (vertical and horizontal) predicted political attitudes, but not actions. While the media influenced Arab women’s attitudes, they did not drive action. To change their status, women’s political actions are essential, requiring grassroots efforts for institutional change and increased access.

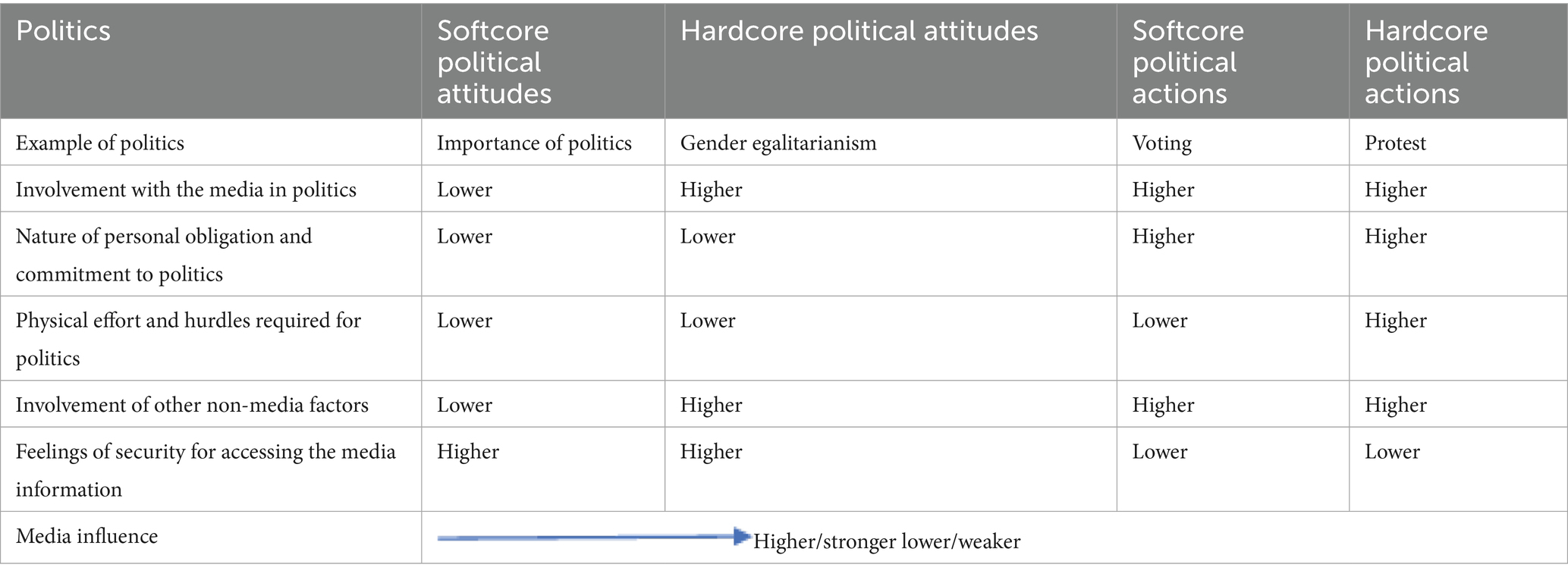

Altourah et al. (2021) and Al-Kandari and Hasanen (2018) categorized politics into softcore and hardcore attitudes and actions based on dimensions. This study refined these categories to consider personal obligations, media involvement, physical effort, and non-media factors affecting attitudes and actions.

Softcore political attitudes, such as interest or importance in politics, align with media information utility. Individuals require only a single exposure to political content to satisfy their curiosity. Cognitive involvement was minimal. Believing in democracy and gender egalitarianism requires more cognitive and physical media involvement. Individuals actively seek information for opinion forming and engaging in cognitive processes (AlReshaid et al., 2025).

Softcore political actions engage in politics without requiring physically demanding activities or risking harm, such as voting or online discussions, unlike attending protests. Demographic, economic, and mega-social factors play a role.

Overall, the study’s findings suggest that the level of media involvement and physical effort required to engage in politics influence an individual’s political attitudes and actions. The study’s categorization provides a useful framework for understanding how media can shape political attitudes but does not necessarily lead to political actions and highlights the need for grassroots efforts to effect institutional change.

As for future research, these findings have several implications for future research. First, studies should move beyond measuring media exposure alone to investigating how individuals interpret political content in relation to their trust in institutions and personal networks. This can be explored through qualitative or mixed-method approaches that delve into media framing and interpersonal dialogue. Second, the stronger role of perceptions in predicting non-traditional political actions signals a shift in Arab political engagement dynamics, warranting a deeper examination of how evolving perceptions of governance and corruption foster civic participation outside of traditional structures. Future research should also explore why religiosity negatively influences political participation and assess whether this reflects ideological disengagement or institutional alienation. Finally, longitudinal studies are needed to assess how changes in trust and media use over time affect political development, especially among women and youth in transitional and semi-democratic societies (see Table 6).

Table 6. A conceptualization categorization of political attitudes and political actions in relation to media political effects.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp.

Author contributions

KC: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Writing – original draft, Project administration. AA-K: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Resources, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AA: Writing – original draft, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This publication was made possible with the support of Gulf University for Science and Technology (GUST).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abouelenin, M. (2022). Gender, resources, and intimate partner violence against women in Egypt before and after the Arab spring. Violence Against Women 28, 347–374. doi: 10.1177/1077801221992877

Al-Kandari, A. A., Frederick, E., Hasanen, M. M., Dashti, A., and Ibrahim, A. (2022). Online Opinion Expression about women serving as judges among university students in Egypt and Kuwait: an integrative study of the spiral of silence and uses and gratifications. Electron. News 16, 104–138. doi: 10.1177/19312431211052056

Al-Kandari, A., and Hasanen, M. (2018). Egypt 5 years after the revolution: a political gratifications study of the motives for viewing television news and political programs that predict political attitudes. Electron. News 12, 128–144. doi: 10.1177/1931243117719927

Al-Kenane, K., Almoraish, A., Al-Enezi, D., Al-Matrouk, A., AlBuloushi, N., and Alreshaid, F. (2025). The process through which young adults form attitudes towards sustainable products through social media exposure in Kuwait. Sustainability 17:4442. doi: 10.3390/su17104442

Alivi, M. A. (2023). Voter’s gratification in using online news and the implications on political landscape in Malaysia. Asian Polit. Policy 15, 623–642. doi: 10.1111/aspp.12718

Allinson, J. (2022). The age of counter-revolution: states and revolutions in the Middle East. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

AlReshaid, F., Erturk, A., Alkhayyat, R., Abdallah, F., Abidi, O., and De La Roche, M. (2025). Are we on the same wavelength? Supervisor-subordinate cognitive style congruence and its association with supervisors’ self-awareness through leader member exchange. Front. Psychol. 16:1583837. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1583837

Al-Tamimi, A., Abdulwahid, A., and Venkatesha, U. (2020). Arab spring in Yemen: causes and consequences. Shodh Sarita 7, 59–63.

Altourah, A. F., Chen, K. W., and Al-Kandari, A. A. (2021). The relationship between media use, perceptions and regime preference in post-Arab spring countries. Glob. Media and Commun. 17, 231–259. doi: 10.1177/17427665211001894

Alqatan, A., Simmou, W., Shehadeh, M., AlReshaid, F., Elmarzouky, M., and Shohaieb, D. (2025). Strategic pathways to corporate sustainability: the roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing, and innovation. Sustainability 17:5547. doi: 10.3390/su17125547

Ancu, M., and Cozma, R. (2009). MySpace politics: uses and gratifications of befriending candidates. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 53, 567–583. doi: 10.1080/08838150903333064

Babbie, E. R. (2020). The practice of social research. 15th Edn. Melbourne, Australia: Cengage Learning.

Bayat, A. (2021). Revolutionary life: the everyday of the Arab spring. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press.

Bawack, R. E., Bonhoure, E., Kamdjoug, J. R. K., and Giannakis, M. (2023). How social media live streams affect online buyers: a uses and gratifications perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 70:102621. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102621

Blagojević, J., and Šćekić, R. (2022). The Arab spring a decade on: information and communication technologies as a mass mobilization tool. Kybernetes 51, 2833–2851. doi: 10.1108/K-03-2021-0240

Chan-Olmsted, S., Wolter, L.-C., and Adam, E. D. (2020). Towards a video consumer leaning spectrum: a medium-centric approach. Nord. J. Media Manag. 1, 129–185. doi: 10.5278/njmm.2597-0445.4600

Cho, Y. Y., Park, A., and Choi, J. (2023a). Motives for using news podcasts and political participation intention in South Korea: the mediating effect of political discussion. Media Int. Aust. 187, 39–56. doi: 10.1177/1329878X231154052

Cho, Y. K., Sutton, C. L., and Taskin, N. (2023). Positive relationships between service performance and social media use in internet retailing: Does information symmetry matter? Contemp. Manag. Res. 19, 207–233. doi: 10.7903/cmr.22963

Cooke, N. A. (2016). Information sharing, community development, and deindividuation in the eLearning domain. Online Learning, 20, 244–260. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1105905.pdf

Curnalia, R. M., and Mermer, D. (2013). Integrating uses and gratifications with the theory of planned behavior to explain political disaffection and engagement. Am. Commun. J. 15, 59–82.

Dubai School of Government. (2011). Arab Social Media Report, Vol. 1, No. 2: Facebook usage: Factors and analysis. Dubai School of Government. Available at: https://www.arabsocialmediareport.com/UserManagement/PDF/ASMR%20Report%202.pdf

Edam, B. K., Shaari, A. H., and Aladdin, A. (2024). The representation of Arab women in English-language newspapers: a comparative analysis of Arab and Western media post-Arab spring. 3L Lang. Linguist. Lit. 30, 110–124. doi: 10.17576/3L-2024-3001-09

Falgoust, G., Winterlind, E., Moon, P., Parker, A., Zinzow, H., and Madathil, K. C. (2022). Applying the uses and gratifications theory to identify motivational factors behind young adult’s participation in viral social media challenges on TikTok. Hum. Factors Healthc. 2:100014. doi: 10.1016/j.hfh.2022.100014

Grinin, L., and Korotayev, A. (2022). “The Arab spring: causes, conditions, and driving forces” in Handbook of revolutions in the 21st century. Societies and political orders in transition. eds. J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_23

Ibnouf, F. O. (2013). Women and the Arab spring: a window of opportunity or more of the same. Women Environ. Int. Mag. 92, 18–21. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/magazines/women-arab-spring/docview/1508756505/se-2?accountid=16531

Inglehart, R., Haerpfer, C., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., et al. (Eds.) (2014). World values survey: round six—country-pooled datafile version. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

Jamil, S. (2022). Postulating the post-Arab spring dynamics of social media & digital journalism in the Middle East. Digit. Journal. 10, 1257–1261. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2022.2040040

Jurasz, O. (2013). “Women of the revolution: the future of women’s rights in post-Gaddafi Libya” in The Arab spring: New patterns for democracy and international law. Vol. 82, Nijhoff law specials. eds. C. Panara and G. Wilson (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff), 123–144. Available at: http://www.brill.com/arab-spring

Kaye, B. K., and Johnson, T. J. (2002). Online and in the know: uses and gratifications of the web for political information. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 46, 54–71. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4601_4

Kaye, B. K., and Johnson, T. J. (2004). A web for all reasons: uses and gratifications of internet components for political information. Telematics Inform. 21, 197–223. doi: 10.1016/S0736-5853(03)00037-6

Liu, P., Han, C., and Teng, M. (2021). The influence of Internet use on pro-environmental behaviors: An integrated theoretical framework. Res. Conserv. Recycl. 164:105162. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105162

McLuhan, M. (2017). “The medium is the message” in Communication theory. (2nd Edition). ed. C. D. Mortensen (New York: Routledge), 390–402. doi: 10.4324/9781315080918

Moghadam, V. M. (2018). Explaining divergent outcomes of the Arab spring: the significance of gender and women’s mobilizations. Polit. Groups Identities 6, 666–681. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2016.1256824

Moore-Gilbert, K., and Abdul-Nabi, Z. (2021). Authoritarian downgrading, (self) censorship and new media activism after the Arab spring. New Media Soc. 23, 875–893. doi: 10.1177/1461444818821367

Ogbonnaya, U. M. (2013). Arab spring in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya: a comparative analysis of causes and determinants. Altern. Turk. J. Int. Relat. 12, 4–16. Available at: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=2c2e503b-cdf9-3a2d-bd6d-cd4ea65da1a0

Park, N., Kee, K. F., and Valenzuela, S. (2009). Being immersed in social networking environment: Facebook groups, uses and gratifications, and social outcomes. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 12, 729–733. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2009.0003

Radsch, C. (2012). Unveiling the revolutionaries: cyberactivism and the role of women in the Arab uprisings. Houston, TX: James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University.

Rathnayake, C., and Winter, J. S. (2021). Do platforms favour dissidents? Characterizing political actor types based on social media uses and gratifications. Hum. Syst. Manag. 40, 249–263. doi: 10.3233/HSM-200888

Rinke, E. M., and Röder, M. (2011). Media ecologies, communication culture, and temporal-spatial unfolding: three components in a communication model of the Egyptian regime change. Int. J. Commun. 5, 1273–1285.

Shaw, F. (2012). The politics of blogs: Theories of discursive activism online. Media Int. Aust. 142, 41–49. doi: 10.1177/1329878X1214200106

Keywords: Arab Spring, Arab women’s agency, Uses and Gratifications, political attitudes, political actions, vertical and horizontal media

Citation: Chen K, Al-Kandari AA and Alsaber A (2025) Women’s use of news media and its influence on political engagement in post-Arab Spring countries. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1622520. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1622520

Edited by:

Muddassir Quamar, Jawaharlal Nehru University, IndiaReviewed by:

Carmelo Cattafi, Tecnologico de Monterrey, MexicoDina Tahat, Al-Ain University, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2025 Chen, Al-Kandari and Alsaber. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmad Alsaber, YWFsc2FiZXJAYXVrLmVkdS5rdw==

KhinWee Chen

KhinWee Chen Ali A. Al-Kandari

Ali A. Al-Kandari Ahmad Alsaber

Ahmad Alsaber