- The Division of International Relations, School of Political Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

While the “peace through globalization” literature is primarily framed as an effort to examine whether economic globalization promotes peace, most of its models investigate whether trade reduces conflict. This study argues that by defining different stages in the transition to peace as a dependent variable, the relationship between a state’s exposure to globalization and peace is more complex than theorized in the literature. Even in our still-globalized world, where countries have numerous options for forming new economic partnerships, greater exposure to the global economy increases the appeal of establishing economic ties with certain partners. Therefore, the ability of economic interactions to foster peace is conditional to some degree on countries’ exposure to globalization. Consequently, a country’s efforts to deepen global integration can amplify the expected benefits of peace with specific nations, creating opportunities for rapprochement. By using Israel-UAE relations as a case study, we illustrate how the UAE’s strategy of diversifying its global economic ties has enhanced the benefits of cooperation with Israel, thereby supporting and strengthening normalization efforts.

Introduction

In September 2020, Israel, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain signed the Abraham Accords, establishing the first full normalization of relations between Israel and Arab Gulf states. The new normalization ties were immediately followed by optimism regarding the role of economic factors in stabilizing relations among the nations.

This was hardly the first time a breakthrough in the regional peace process sparked hopes for creating significant “peace dividends” to stabilize peace in the Middle East. The longstanding proposition known in the International Relations literature as “commercial liberalisms,” which posits that trade promotes peace, has been echoed for decades through various visions and detailed official plans aimed at normalizing Arab-Israeli relations (Kahn and Arieli, 2020; Press-Barnathan, 2006; Ripsman, 2016).

Nonetheless, policymakers and analysts who aim to rely on established scholarly research to support the notion that the economic domain can promote regional peace in the Middle East and other regions may find it difficult to find adequate support in existing studies. While the literature on commercial liberalism is often framed around the question of whether “trade fosters peace,” most models examine whether trade reduces the likelihood of conflict.

Therefore, the evidence presented in the mainstream literature may support the argument that establishing trade ties between former rivals, such as Israel and the UAE, increases the likelihood that they will resolve future disputes peacefully. Nonetheless, further research is needed to clarify the role of the economic dimension in facilitating the signing and upgrading of normalization agreements. While work on the different levels and stages of peace stresses that the determinants of conflict do not necessarily apply to peace (Mattes and Weeks, 2024, p. 186), most research on reconciliation and conciliation that examines economic incentives links them to mechanisms presented in the literature on trade–conflict.

This paper seeks to bridge these gaps in the commercial liberalism and reconciliation literature. We focus on the positive aspects of globalization that make peace more likely. In the last two decades, most studies have shifted their attention from dyadic trade to exploring whether multilateral trade and other aspects of global economic integration reduce conflict. Some studies argue that as trade becomes more central to economies, the potential costs of disrupting trade with third parties in a conflict decrease the likelihood of war (Gartzke and Li, 2003; Russett and Oneal, 2001). However, critics contend that globalization weakens the deterrent power of trade by making it easier for belligerents to find alternative trade partners (Brutger and Marple, 2024; Gowa and Hicks, 2017).

Building on this ongoing debate, we argue that while increased economic globalization may reduce the deterrent effects of trade, it can also enhance the appeal of trade relationships with specific partners. Therefore, a country’s efforts to deepen its integration into the global economy may increase the expected benefits of peace with particular nations. As a result, periods of intensified global economic integration could foster opportunities for rapprochement and transition toward “warm peace.”

We used Israel-UAE relations as a case study to support this argument. Most scholars and analysts correctly argue that, at its core, the rapprochement between Israel and the UAE reflects the realist story of alignment among rivals with mutual enemies and shared national interests (Guzansky and Marshall, 2020; Fulton and Yellinek, 2021). Nevertheless, a closer examination of the relations between the two states reveals a more complex dynamic in which economic factors and business communities played a significant role in facilitating the discreet diplomatic contacts maintained long before the formal decision to normalize their relations. Moreover, these economic factors continue to play a crucial role in what appears to be a smooth transition toward a “warm peace.”

We argue that the UAE’s efforts to increase and diversify its global economic integration have amplified the expected benefits of economic cooperation with Israel’s open economy. These efforts should be considered a key factor in the positive impact of economic interactions on fostering and strengthening the normalization of ties.

We proceed as follows: First, we briefly review the “peace through globalization” literature, highlighting its limitations in addressing the different stages of peacebuilding. We then present our theoretical argument, explaining why, even in the still-globalized world where countries have numerous options for forming new economic partnerships, engagement with a specific country can hold unique importance, thereby encouraging the improvement of political relations. Next, we present our case study, which illustrates how global integration has positively impacted various stages of the transition to peace between the UAE and Israel. Finally, we discuss how our findings contribute to the existing literature.

The missing dimension of the “peace through globalization” literature

According to the standard causal mechanism of the commercial liberalism theory, extensive trade between a pair of states increases the opportunity costs of military conflict, thereby reducing the chances of conflict (Polachek and Xiang, 2010). Empirical tests largely support this claim, finding that bilateral trade reduces the likelihood of conflict (Hegre et al., 2010; Russett and Oneal, 2001).

Thus, while most of these studies are motivated to explore the “pacifying” effect of trade, their causal mechanism and empirical findings underscore trade’s role in reducing conflict.

Scholars investigating the role of economic factors in peacebuilding across different regions have emphasized the importance of bridging the gap between the classic liberal idea that “trade fosters peace” and the literature focused on conflict (Kahn and Arieli, 2020; Pernes and Möller, 2014; Press-Barnathan, 2006). However, this literature often critiques the traditional model of commercial liberalism, which focuses on bilateral trade and rarely engages with recent scholarship on extra-dyadic relations.

Other comprehensive studies of the different levels of interstate peace that consider economic interdependence likewise emphasize bilateral economic engagement between former rivals (Kupchan, 2010). Expanding beyond the dyadic economic engagement, some work highlights the role of third parties’ economic and financial aid in facilitating de-escalation and cooperation at different stages (Press-Barnathan, 2006; Rubinovitz and Rettig, 2018; Thompson et al., 2022).

This study contributes by shifting the focus from bilateral ties to multilateral links and by evaluating both the contributions and the limitations of the literature on globalization and conflict. It examines the challenges, limitations, and potential contributions of recent mechanisms tied to multilateral trade and other facets of economic globalization across the stages of the transition to peace.

Building on the logic of opportunity costs, many studies argue that multilateral trade integration reduces conflict. As trade becomes a larger part of a country’s overall economic activity, the costs of disrupting trade with third parties during conflict increase, thereby reducing the likelihood of conflict (Gartzke and Li, 2003; Russett and Oneal, 2001).

This mechanism has also been extended to other aspects of global economic integration, most notably the internationalization of capital. States that are highly exposed to foreign direct investments (FDI) are further deterred from conflict, as war can depress FDI and trigger capital flight (Bussmann, 2010; Bussmann and Schneider, 2007; Polachek et al., 2011). Because investments involve high sunk costs, multinational corporations (MNCs) have incentives to lobby their home governments to avoid conflict with host countries, and the negative externalities that conflict imposes on investment deter host governments. Fehrs (2016, 2024) shows that similar considerations apply to rapprochement: in wealthier states, strong MNCs can advocate for the economic dividends of reconciliation, while in countries undergoing economic liberalization, the need for foreign capital can itself motivate reconciliation. Ripsman (2016) likewise shows that the need for capital among economically distressed countries can incentivize leaders to engage in “top-down” peacemaking.

Other studies have called for moving beyond the opportunity-cost mechanism, highlighting additional ways in which economic globalization discourages conflict. One body of research has used social network analysis to show that the likelihood of conflict is lower between dyads that share many trading partners and are embedded in trade networks (Dorussen and Ward, 2010; Kinne, 2012). Another explanation for the conflict-reducing impact of trade integration and open capital markets is that economic openness enables states in crisis to send “costly signals” and demonstrate their resolve to use force without actually resorting to it (Gartzke et al., 2001; Kinne, 2014).

All these leading mechanisms implicitly or explicitly assume that dyadic conflicts disrupt multilateral trade, resulting in high costs. However, studies have challenged this assumption, arguing that trade globalization facilitates a smoother wartime substitution process by allowing states to shift trade and investments to alternative markets. Trade globalization reduces the income losses associated with conflict with an individual trade partner (Brutger and Marple, 2024; Schneider, 2014, 2023), thereby increasing the likelihood of dyadic conflict (Martin et al., 2008).

Nonetheless, this line of criticism acknowledges that the ability to reduce trade-related costs through substitution is not uniformly distributed across states (Chen, 2021; Feldman et al., 2021; Peterson, 2015). Moreover, even scholars who argue that substitution undermines the deterrent power traditionally attributed to trade note that moving away from the first-best option entails efficiency costs (Gowa and Hicks, 2017, 654).

Thus, even in the still-globalized world, various markets enjoy competitive advantages, making them natural trading partners with other countries. While armed conflict creates constraints that may divert combatants from optimal trade partners, the absence of official relations with potential first-best options also leads to efficiency losses. These losses become more apparent to policymakers focused on transforming their economies.

When a country aims to diversify its economy and deepen global trade integration, specific sectors may naturally complement those in other nations. Nevertheless, the lack of normalized relations with these potential economic partners creates a barrier to establishing or expanding economic ties. Consequently, becoming more economically globalized can generate a strong incentive to pivot toward new markets and normalize political relations with them.

The positive aspect of peace through globalization

Because it encompasses overlapping dynamics, economic globalization is difficult to define and cannot be captured by a single measure. Early studies of the globalization–conflict nexus often relied on trade openness, which is the ratio of total trade to GDP (Gartzke and Li, 2003; Russett and Oneal, 2001). Later research showed that such proxies do not fully capture a state’s level of trade integration or the complex ways in which trade globalization influences conflict.

For instance, several studies have measured trade diversification and network structures to assess states’ ability to mitigate conflict-related costs by redirecting trade (Gartzke and Westerwinter, 2016; Kleinberg et al., 2012). Sadeh and Feldman (2020) use the KOF Economic Globalization Index, which combines sub-indices of trade and FDI flows with indicators of trade and capital restrictions (Dreher, 2006).

These studies argue and empirically demonstrate that greater trade diversification reduces the pacifying effect of bilateral trade by reducing concerns about the trade-related costs of conflict with a specific potential foe. Nonetheless, as with more traditional works, these studies conclude that their findings imply that trade diversification reduces trade’s ability to promote peace. However, their findings and analyses actually suggest that trade diversification decreases the deterrent power of trade. When focusing on peacebuilding as the dependent variable, trade and investment diversification could, in fact, have a highly constructive impact.

Consider a state that aims to diversify its economy and reduce its reliance on specific industries and commodity exports. Strategically minded policymakers would likely avoid replacing one source of economic vulnerability with another. As Copeland (2014, p. 2) notes, “commercial ties make states vulnerable to cutoffs—cutoffs that can devastate an economy.” Therefore, when a country diversifies its economy and seeks to increase its global economic exposure, it prefers to establish trade and investment relations with various new markets, thereby reducing its reliance on just a few economic partners.

However, certain countries may still be considered particularly important even when striving to avoid macro-level reliance on a few markets. These countries may possess competitive advantages that can contribute to the development of specific industries or reduce microeconomic reliance on a single supplier. This means that diversification efforts could increase the attractiveness of economic engagement with more potential countries, thereby incentivizing the normalization of relations with them.

Studies on the globalization of innovation suggest that countries capable of sustaining diverse, productive knowledge can manufacture complex products that few others can (IMF, 2023, p. 8). A large body of literature concludes that globalization is necessary but not sufficient for technology adoption and innovation (Archibugi and Iammarino, 2002; Skare and Soriano, 2021). Trade and investment are key channels for the international diffusion of innovation. However, for globalization to drive technological transformation, countries must be able to access and absorb advanced technologies from leading economies and collaborate with multinational corporations (MNCs) that possess state-of-the-art capabilities (Archibugi and Iammarino, 2002; Fatima, 2017). Consequently, states that liberalize capital controls and FDI policies may still fail to realize the full benefits if strained political relations with key partners restrict access to particular technologies or deter MNCs capable of transferring them.

One key feature of a globalized economy is the prevalence of cross-border intra-industry trade and vertical integration across long-distance supply chains. Countries integrated into the global economy are heavily involved in the trade of intermediate inputs, much of which occurs within subsidiaries of multinational MNCs. The growing role of MNCs in international trade has strengthened the interconnections between trade and FDI networks (Srivastava and Rahul, 2023). Consequently, the economic costs of being unable to engage with a key actor in these supply chains extend well beyond the immediate loss of bilateral trade. Disruptions can affect upstream and downstream trade flows along supply chains and may also weaken a country’s ability to attract certain types of FDI from third parties.

From a network-based literature perspective, this means that as a country deepens its economic integration, the expected utility of peace with another country is influenced by both countries’ position (or centrality) within trade and FDI networks. The network-based literature accounts for a country’s ties with every other country in the international trade system, representing its overall location within trade networks (Dorussen and Ward, 2010; Kinne, 2012).

Several studies suggest that a more central position within the network could enhance a state’s role as an effective or credible mediator during crises and interstate disputes (Dorussen and Ward, 2010; Kinne, 2014). However, a central actor in a trade network can also leverage its position during peacetime. For example, a well-positioned state in global or regional trade networks can serve as a credible mediator in resolving trust issues that prevent countries from fully realizing the benefits of economic engagement.

By normalizing relations with one country, an integration-seeking country could expand trade and investment relations with other countries in the region. Consider States A and B, which cannot fully exploit the economic potential of their bilateral relationship due to political tension, trust issues, or political risks that deter foreign investment. State C, which has trade relations with B but not A, could become a credible intermediary and participate in a joint economic project between A and B if it develops extensive trade and investment relations with A.

As Copeland (1999, 2014) argues in his work on trade expectations theory, positive expectations about the ability to sustain profitable trade in the future can help prevent conflict, reduce tensions, and promote more cooperative relationships between rivals. We maintain that positive expectations about future economic engagement can likewise facilitate the path to rapprochement and enhance the stability of normalization agreements. Such expectations are likely to be stronger when states seek to increase their exposure to the world economy.

When states pursue deeper integration into the global economy, economic engagement with specific partners becomes especially attractive, raising the expected returns to normalization. Put differently, the costs of political barriers to economic engagement become more salient when governments adopt explicit strategies to diversify trade and attract FDI to boost productivity and innovation. Accordingly, a country’s degree of exposure to economic globalization shapes the expected benefits of normalizing relations with particular partners and, in turn, the effectiveness of economic cooperation as a pacifying tool among globalized states. We therefore contend that economic cooperation between former adversaries is more likely to foster peacebuilding when at least one party actively pursues deeper global economic integration.

Case study

Case selection

To examine the pacifying impact of global economic exposure, we focus on the different stages of the UAE-Israel normalization process. The Abraham Accords serve as a valuable case study for several reasons. First, they represent an extreme value of our independent variable: an intense effort to increase economic integration. As detailed below, the UAE has been pursuing a strategy to diversify its economy through expanded trade and investment. Israel, too, has expressed its intent to open up to new markets.

Second, the case involves two high-income countries with narrow economic power disparities. This helps to control for one of the key factors often blamed for the failure of post-normalization economic initiatives in the region: asymmetric economic power and trade relations. Critics of commercial liberalism have long emphasized the negative impact of asymmetric trade relations, maintaining that the less dependent state might use its position to coerce the more dependent state without incurring any significant economic costs (Barbieri, 2002). Deepening ties between weaker and stronger economies can exacerbate concerns about uneven profit distribution, potentially shifting the balance of power (Gartzke and Westerwinter, 2016).

The shadow of economic power disparities has long loomed over regional peace processes, dating back to the early years of the implementation of the Israeli–Egyptian peace treaty. Economic incentives played a major role at various stages of Israel’s de-escalation with Egypt, yet most involved U. S.-provided support in multiple forms, leveraging economic distress in Egypt and Israel (Ripsman, 2016, p. 84; Thompson et al., 2022, pp. 256–260). By contrast, Egyptian concerns that emerging economic frameworks would yield relative gains for Israel and allow it to dominate Egyptian markets slowed early efforts to promote post-conflict normalization through bilateral economic cooperation (Press-Barnathan, 2006; Rubinovitz and Rettig, 2018).

Relative-gains concerns resurfaced in nearly every initiative promising “peace dividends” from deeper integration with Israel. These concerns either blocked comprehensive agreements or provoked domestic backlash during implementation. The constraining effects of asymmetric economic power were likewise evident in the formation and implementation of one of the most notable efforts to stabilize normalization through economic cooperation: the Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZ) initiative. Framed by the U. S. as a tool to support regional peace through the facilitation of economic cooperation, the QIZ model offers non-reciprocal duty-free access to U. S. markets for industrial goods manufactured cooperatively by Israel and its neighbors in “Qualified Industrial Zones.”

Influenced in part by worries about uneven profit distribution, Egypt rejected the U. S. offer to join the QIZ in 1996. It later reversed course and signed a QIZ agreement in 2004, primarily to offset the anticipated negative effects of shifts in the global trading system on the competitiveness of its textile industry (Kahn and Arieli, 2020). Jordan, by contrast, signed a QIZ agreement in 1997, shortly after the U. S. proposal. The QIZ generated some tangible peace dividends for Jordan, including increased foreign direct investment and higher exports to the United States. However, its implementation also drew domestic backlash, with critics arguing that the agreement disproportionately benefited Israeli and third-country multinational firms (Arieli and Kahn, 2019; Bouillon, 2004).

Asymmetry aside, various structural domestic factors make it easier for the UAE to openly promote normalization with Israel (Podeh, 2022, p. 71). However, because there is no substantial economic power disparity between the states, those seeking to destabilize normalization would find it difficult to raise credible concerns that engaging with Israel’s strong economy would have negative strategic implications, as it would empower Israel at the expense of the UAE. Measures commonly used in the literature to illustrate disparities in economic power indicate that, in some sense, this time, Israel can be regarded as the weaker party. The gap in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) levels was almost unnoticeable on the eve of the normalization agreement. In 2020, Israel’s nominal GDP was $407.1 billion, while the UAE’s was $385 billion. Israel’s GDP per capita in current nominal prices was also slightly higher than the UAE’s, at $44,180, compared to $38,600 in the UAE. Nonetheless, the UAE’s GDP per capita, in terms of purchasing power parity, was significantly higher than Israel’s, at $71,140 compared to $41,200 (IMF, 2025). For comparison, on the eve of the peace agreement between Israel and Egypt, the gap in their GDP size was marginal, but Israel’s GDP per capita was approximately six times higher than Egypt’s. In 1994, Israel’s GDP was approximately 10 times higher than Jordan’s, and its GDP per capita was approximately 4.5 times higher (IMF, 2025).

In addition to political factors, economic fundamentals reflected in economic-power disparities may constrain the scope for wide-ranging cooperation. For instance, expectations of substantial cross-border transfers of advanced goods and services from Israel to Egypt and Jordan largely went unrealized, partly because both economies had limited need for the particular advanced technologies Israel supplied (Kahn and Arieli, 2020, p. 10, Ripsman, 2016, pp. 109–110).

Accordingly, from a regional perspective, Israel–UAE relations can be treated as a “most-likely case” for the thesis that economic cooperation supports peace. The dyad brings together two high-income economies with relatively small economic power disparities, a configuration more favorable than earlier Egypt–Israel and Jordan–Israel efforts to stabilize peace through economics. However, in a broader comparative frame, it also has features of a “hard case.” Despite never fighting a direct war, the UAE and Israel sustained decades of diplomatic hostility: the UAE formally boycotted Israel from 1972, consistently opposed its foreign policy, and aligned with several of Israel’s past and present adversaries (Fulton and Yellinek, 2021). Therefore, if economic factors help facilitate the signing of a normalization agreement and stabilize relations between these longstanding rivals, the finding would suggest that economic drivers may likewise support normalization among other state pairs, most of which face fewer historical grievances.

The road for normalization: did trade follow the flag?

One of the leading debates in the literature on the relationship between trade and peace concerns the direction of influence of the two variables. Whereas commercial liberalism maintains that trade promotes peace, the “trade follows the flag” hypothesis emphasizes the primacy of high politics, arguing that political relations influence trade patterns but not vice versa (Chen and Zhou, 2021; Gowa and Mansfield, 1993).

Similar divisions appear in the reconciliation literature. Fehrs (2016, 2024) presents evidence indicating that economic development incentives were among the most important factors motivating rivals to pursue reconciliation. By contrast, Kupchan (2010) argues that reconciliation opens the door to economic integration, not the other way around. Acknowledging the potential positive impact of economic incentives, Thompson et al. (2022) conclude that such incentives are neither necessary nor sufficient, on their own, to achieve reconciliation.

At first glance, the signing of the Abraham Accords and their trade-related implications might be regarded as clear evidence favoring the ‘trade follows the flag’ hypothesis. Almost all policy-oriented and academic research maintains that national security interests dominated economic considerations in making normalization possible (Guzansky and Marshall, 2020; Fulton and Yellinek, 2021). Shared concerns about Iran’s nuclear ambitions, as well as the common hostility toward Islamic extremists that has intensified in the Arab Gulf states following the Arab Spring, have laid the foundations for a long-lasting strategic dialog. This coordination deepened after the 2015 Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA), which both sides saw as a sign of the U. S. disengaging from the region, further uniting their interests. These factors eroded the UAE’s commitment to the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative, which tied normalization to an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement (Guzansky and Marshall, 2020; Ravid, 2022).

The last year of President Donald J. Trump’s first term created additional incentives for the UAE to move toward full normalization. Shortly after the signing of the agreement, it was revealed that the UAE and the U. S. had reached several strategic understandings, including an American guarantee to supply the UAE with advanced F-35 fighter jets. Negotiations took place amidst Israel’s plans to annex parts of the West Bank. Israel agreed to suspend these plans as part of the agreement, enabling the UAE to present the normalization as a diplomatic win for the Palestinian cause (Guzansky and Marshall, 2020; Vakil and Quilliam, 2023). For Israel, the agreement represented a major diplomatic success, allowing it to normalize relations with an important regional power and to formalize elements of regional security integration, without making substantive concessions on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Therefore, one might argue that the direction of influence between the variables is straightforward: strategy-motivated factors that led to the signing of an official peace agreement opened the door for economic engagement rather than vice versa. Nonetheless, a closer examination of the states’ relations reveals a more complex dynamic.

While the normalization agreement surprised many, it was rooted in a secret diplomatic and strategic dialog that had been going on for many years. The various tracks of this strategic dialog took place alongside overlapping economic tracks, with extensive interactions conducted under the radar (Black, 2019). The strategic context followed the extent of economic ties, but in many cases, it was also the other way around.

Unlike Oman and Qatar, which briefly engaged in official trade with Israel after the 1993 Oslo Accords, the UAE preferred to keep its economic interactions with Israel unpublicized (Vakil and Quilliam, 2023). In response, a few officials from the Israeli Foreign Ministry guided Israeli companies on how to enter the UAE market discreetly. The goal was to establish business networks that could eventually lead to political engagement. By 2006, Israel had a secret presence in Dubai, operating under the commercial name “The Center for International Development and Commerce,” a “firm” with Israeli diplomats on its board (Ravid, 2022, pp. 116–112).

In 2009, Israel’s defense establishment blocked a secret drone deal with the UAE, straining the covert relationship. Tensions worsened after Mossad agents assassinated Hamas operative Mahmoud al-Mabhouh in Dubai in 2010 (Black, 2019, p. 12). While these events significantly reduced commercial interactions and cut off almost all political interactions, the secret Israeli representative continued to operate, albeit in a much more muted form (Ravid, 2022, p. 128).

Representatives of Israeli firms predicted that their discreet business activity would return to normal soon, as the UAE would not be willing to deny itself access to Israeli hi-tech, agricultural, and medical know-how (Friedman, 2010). Diplomatic and economic ties were restored less than 2 years after the crisis. Analysts concluded that shared strategic concerns helped overcome the rift, with security and interagency coordination playing a key role (Jones and Guzansky, 2017, p. 408). However, the strategic and economic domains were closely linked, as much of the economic engagement involved Israeli defense products, surveillance equipment, and cybersecurity services that required approval from the Israeli Ministry of Defense.

Once relations resumed, economic factors became the most visible aspect of the Israel-UAE relationship. The number of Israeli businesses, often operating through third-party states, steadily increased. Between 2011 and 2020, international media occasionally reported that Israeli firms were finalizing contracts in defense, high-tech, cybersecurity, agriculture, and medicine (Black, 2019; Traub et al., 2023). Jones and Guzansky (2017, 2020) argue that these economic ties are part of the “tacit security regime” (TSR) between Israel and the Gulf states. Such regimes, driven by shared strategic interests, emerge without formal agreements. In the Israel-UAE case, the economic interactions helped mute the structural constraints that often challenge cooperation between official adversaries (Jones and Guzansky, 2017).

The shift in the UAE’s attitude toward Israel, which broke the decades-long official boycott and eventually led to the normalization agreement, would have been impossible had the parties not shared core strategic interests. However, all studies that explain the UAE’s decision to normalize relations with Israel agree that the Abraham Accords resulted from the quiet ongoing diplomatic engagements with a strong economic dimension. Although isolating the overlapping economic and strategic elements is challenging, the economic interactions were, at the very least, a variable that played a significant role in building trust between the states, mitigating the constraints on political engagement before normalization, and facilitating the decision to normalize relations more easily.

In line with the literature stressing the role of positive future trade expectations in promoting cooperative relationships between rivals (Copeland, 1999, p. 2015), Israel-UAE economic ties and the expectation of expanding them helped strengthen pre-normalization cooperative relations. The absolute gains from unrecorded economic activities indicated the vast economic potential available if business and trade activities were conducted openly within the framework of an official relationship. As we discuss in further detail below, the increased expected utility of normalization, which would facilitate formal trade relations, is closely linked to the UAE’s diversification and globalization objectives.

The facilitative role of economic factors in warming the peace

The transition to peace is a lengthy process that extends beyond the initial step of establishing formal relations (Diehl et al., 2021; Mattes and Weeks, 2024). Scholars distinguish levels of interstate relations, ranging from severe rivalry through cold and warm peace to security communities. Within this framework, war is an event or outcome, whereas rapprochement and reconciliation are understood as processes (Mattes and Weeks, 2024) or as relationships (Goertz et al., 2016). Miller (2005) illustrates how difficult it can be to move from the first stage of achieving a peace agreement to a “warm peace,” in which strong transnational ties exist and the prospect of returning to war becomes unthinkable. Kupchan (2010) argues that transforming a peace treaty into a “stable peace,” in which cooperation and mutual trust replace deterrence and eliminate the possibility of conflict, is a lengthy process that requires fulfilling several demanding conditions.

In the case of Israel-UAE relations, however, the transition period between signing the agreement and what appears to be a move toward warm or stable peace has been quite smooth. That is not to say that all hurdles to economic and diplomatic interactions stemming from security concerns, bureaucracy, or political tensions have been removed. Nonetheless, in a very short period, Israel and the UAE have established extensive economic relations, which are most visible and highlighted in their interactions.

Until recently, it was almost impossible to find an article or official statement referring to the Abraham Accords without mentioning the phrase “warm peace,” which is often linked to the economic sphere. That wave of optimism and euphoria, characterized by vibrant public diplomacy and high-profile economic interactions, has somewhat diminished and become more subdued since the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. Many have expressed concern that this conflict will cool relations, dampening the UAE’s willingness to engage economically with Israel openly (Grossman, 2024). One notable event that drew significant attention was the report that BP and Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. (ADNOC) suspended their planned acquisition of a 50% stake in Israeli gas company NewMed Energy, citing geopolitical tensions stemming from the Gaza conflict (Turak, 2024).

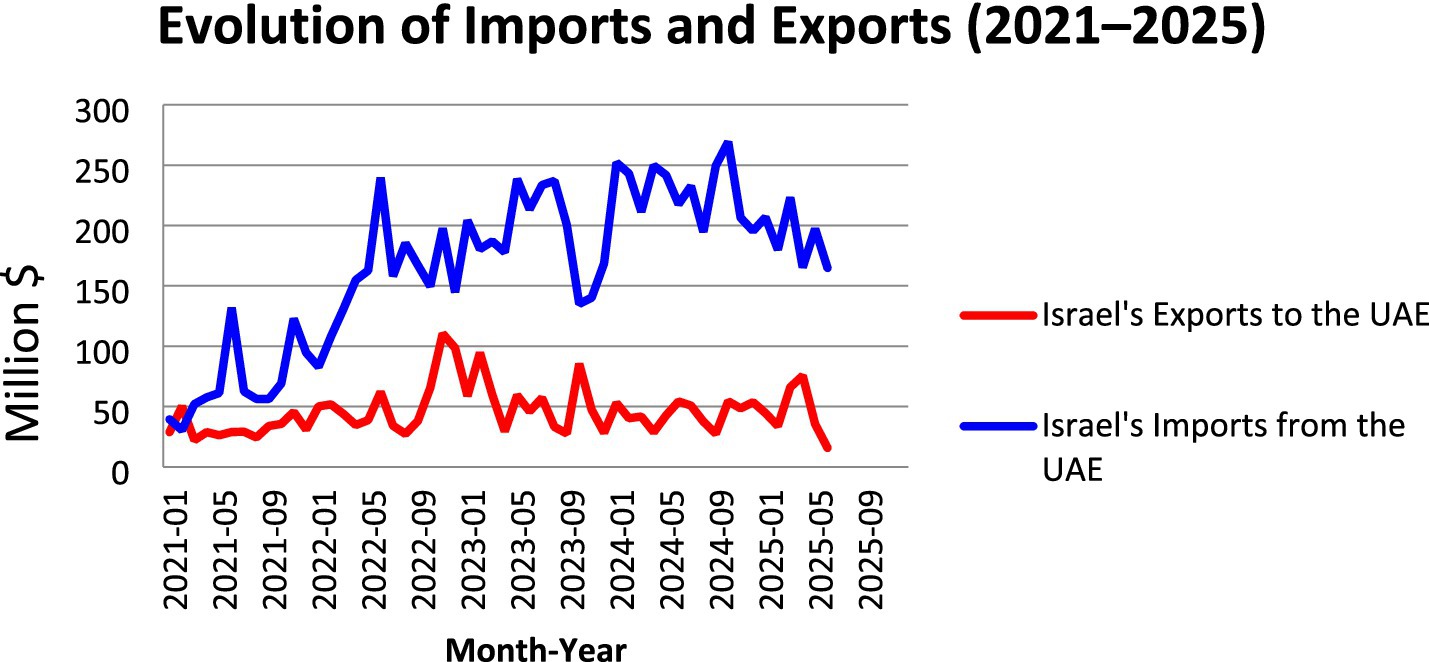

However, alongside these concerns, there is widespread recognition of the strong economic potential, which The Economist dubbed “the commercial logic of the rapprochement” (The Economist, 2023). Throughout the Israel–Hamas war in Gaza, Israel–UAE economic engagement has continued, albeit with a lower public profile. In 2024, Israel’s imports from the UAE increased by approximately 8.5 percent compared to 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Israel’s imports and exports from the UAE. Data source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS).

Four years into the Abraham Accords, Israel and the UAE are engaged in extensive, growing bilateral trade. In 2021, trade in goods reached $1 billion. By 2022, it had exceeded $2.5 billion, and by 2023, it had grown to nearly $3 billion (Israel CBS, 2025). In May 2022, the parties signed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), marking the first free trade agreement between Israel and an Arab country. Officials from both states estimate that the CEPA, which provides immediate or gradual tax exemptions on 96% of trade between the countries, will boost trade to 10 billion dollars within 5 years, positioning the UAE among Israel’s top ten trade partners (Lieber, 2022).

These numbers are added to hundreds of millions of dollars in trade in services and in Israeli defense exports, the real amounts of which remain secret. According to Israel’s Ministry of Defense, in 2021, sales to the ‘Abraham Accords countries’ amounted to 7% of Israel’s 11.3 billion dollar total defense exports (Nissenbaum, 2022). In August 2024, Bloomberg reported that Israel Aerospace Industries was moving forward with plans to establish a presence in Abu Dhabi, where it would convert Emirates aircraft into freighters (Al-Rashdan, 2024). A year later, in August 2025, reports indicated that the UAE’s Edge Group was set to procure the Hermes 900 unmanned aerial vehicle from Israel’s Elbit Systems. According to an analysis by the Washington Institute, a key feature of the agreement is its phased technology transfer component, which accompanies the purchase of an undisclosed number of drones and is designed to enable eventual domestic production by an EDGE Group subsidiary (Dent, 2025). The willingness of the UAE to engage with Israel’s defense industry amid the peak of regional tensions can signal its commitment to long-term economic and defense-industrial cooperation with Israel.

Since the normalization agreement, more than 1 million Israeli tourists have flown directly to the UAE. Even during the Gaza war, when many international airlines suspended flights to Israel, UAE carriers continued operating, maintaining a vital air bridge between Israel and the Gulf. This resilience allowed Dubai to emerge as a principal transit hub for Israelis, described in Israeli media, notably Globes, as a “lifeline for Israeli travelers” (Livne, 2025). Alongside trade and investment activity, cooperation channels and people-to-people activities have been established between universities, research centers, and cultural institutions, most of which continued, albeit more quietly, during the war (Halevi et al., 2025).

Withdrawing from normalization would strand sunk costs in several high-profile ventures (detailed above and below), resulting in real losses for key firms and funds in both countries. That said, current Israel–UAE trade levels, though impressive in scale and growth, are not, by themselves, sufficient to generate the macro-level opportunity costs that would make a break in normalization unthinkable. Israel’s imports from the UAE account for less than 1% of its total imports (Israel CBS, 2025). The UAE’s exports to Israel amount to less than 0.5 percent of its total exports (UAE Ministry of Economy and Tourism, 2025).

Nonetheless, the facilitating role of economic engagement should be assessed from a broader perspective, one that extends beyond the opportunity costs of specific investments or short-term trade fluctuations. The swift transition from no official economic ties to formal, steadily expanding trade provides tangible evidence of both governments’ and business communities’ willingness and political capacity to realize new opportunities. These positive signals generated early momentum among a wide range of actors seeking to deepen economic engagement.

This momentum is evident in the regular visits by senior officials and business leaders, the establishment of offices and R&D centers by Israeli firms in the UAE and by UAE firms in Israel, as well as in the signing of dozens of memorandums of understanding. Beyond the importance of these interactions for current or future economic gains, they create developed and broad-based transnational ties, which is one of the characteristics of a “warm” or “stable” peace (Miller, 2005, p. 232; Kupchan, 2010, p. 7). As these transnational ties deepen, breaking them becomes more difficult, and returning to the pre-normalization status becomes more unthinkable.

Notably, Israel and the UAE have never been engaged in a war, which may explain their ability to adopt the phrase ‘warm peace’ more easily. Furthermore, the question of whether economic interactions move countries toward the stage where war is unthinkable is irrelevant. Nevertheless, it appears that economic interactions are playing a significant role in reducing the likelihood that the two countries will withdraw from the normalization agreement. As recently putted by Al-Nuaimi, a member of the UAE’s Federal National Council: “In the UAE, Israelis are not only accepted but welcomed by both the government and society. Although the UAE disagrees with many of the current Israeli government’s policies, it has rejected the regional norm of expressing displeasure by withdrawing ambassadors or closing embassies. Instead, it has remained committed to engagement, believing that Israel’s integration strengthens both the UAE’s security and the region’s collective stability” (Halevi, 2025).

The conditioning effect of globalization on the pacifying role of economic engagement

Our theoretical argument is that economic cooperation between former rivals is more likely to improve overall relations when at least one party in the dyad seeks to enhance its global economic integration. This section connects the previously discussed economic dynamics to the UAE’s globalization efforts over the past decade. We demonstrate that these dynamics, network effects, and the expected future economic benefits are closely aligned with the UAE’s long-term strategy to diversify its economy through increased global integration.

Independent variable

In his study on the impact of states’ centrality in the network on conflict, Kinne (2012) uses the UAE to illustrate why trade openness may not adequately reflect a state’s level of trade integration. He rightly observes that oil-exporting countries, such as the UAE, can achieve high total trade-to-GDP ratios while trading with only a limited number of partners and maintaining low levels of globalization exposure (Kinne, 2012, p. 310).

However, since the publication of Kinne’s paper, the UAE has undergone significant economic changes that have dramatically increased its centrality in global trade and investment networks and steadily improved its position in various other globalization rankings. For instance, its ranking in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index rose from 46th place in 2009 to 16th in 2020 (The World Bank, 2024). Over the past two decades, the share of non-oil exports in total exports has doubled. Recent policies aimed at easing restrictions on foreign ownership have also contributed to the UAE’s rising rank in the global share of FDI inflows, moving from 37th place for 2000–2009 to 16th place for 2019–2021 (IMF, 2023).

These developments stem from the UAE actively pursuing policies to lessen its reliance on oil revenues by diversifying trade and investing in technology, renewable energy, logistics, and finance sectors. These objectives were introduced in 2010 as part of a national strategy called “Vision 2021” and in subsequent initiatives, such as the “UAE 2050 Strategy and Climate Neutrality Goal.” The IMF contends that the overall aim of these comprehensive visions is “to boost the country’s integration into global value chains, expand employment of nationals in the private sector, and incentivize advanced technology creation and adoption” (IMF, 2023, p. 5).

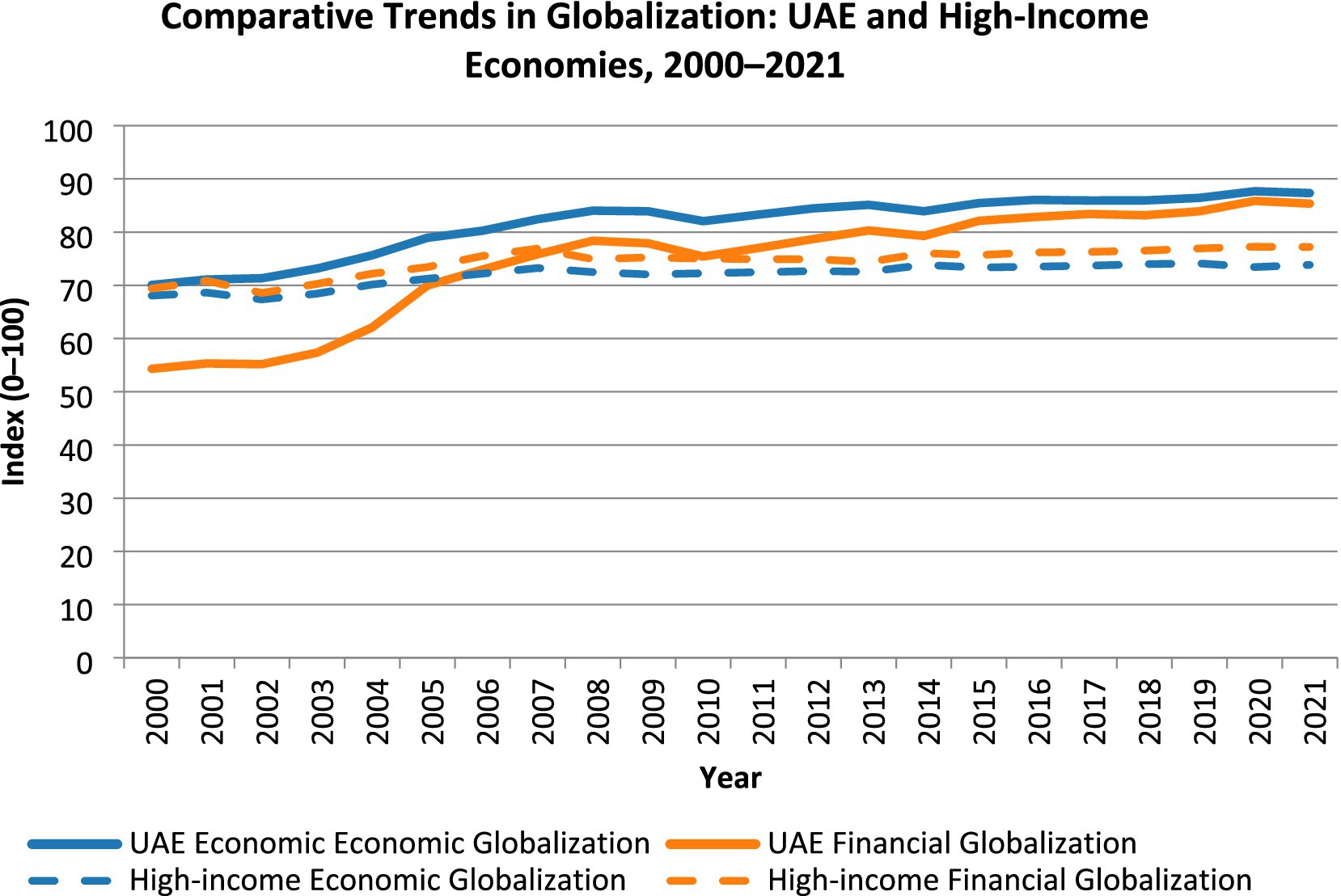

The effects of these developments are evident in widely used measures of economic globalization. Figure 2 presents the evolution of two KOF indices: (1) the KOF Economic Globalization Index, composed of subindices that capture countries’ actual trade and FDI flows as well as restrictions on trade and capital; and (2) the KOF Financial Globalization Index, which reflects inward and outward stocks and flows of foreign capital and the stringency of capital controls. As the figure shows, the UAE’s scores on both indices have steadily increased, surpassing the average for high-income economies.

Despite clear progress in economic diversification, the UAE and international organizations acknowledge that the country is still far from fully capitalizing on the potential benefits of further integration to achieve its strategic economic objectives. Vision 2021’s leading goal is to become a “competitive knowledge economy.” The UAE’s share of high-tech exports has increased from 3.3% in 2008 to almost 9% in 2021 (The World Bank, 2023). However, as the IMF notes, UAE exports still have “weak technology content,” and the country stands to gain significantly from deeper integration with the knowledge-based economies of the 11 countries with which it has recently signed or begun negotiations for CEPAs (IMF, 2023, p. 8).

Diversification’s effect on the “peace dividend”

UAE economic diversification policies are often outlined as both its strongest source of “soft power” and a factor motivating the emphasis on different ‘soft power’ measures (Vakil and Quilliam, 2023). Despite often being attributed to soft power, the ambition to materialize the economic model is a high-level political factor that shapes its foreign policy. Vision 2021 motivated the UAE to increasingly emphasize soft power measures to bring it closer to those who could help realize the plan (Traub et al., 2023). Nonetheless, even studies emphasizing the primacy of traditional national security considerations note that the UAE’s ambition to move toward a more open knowledge economy has increased the appeal of interacting with Israeli firms (Jones and Guzansky, 2017, p. 409; Fulton and Yellinek, 2021, p. 506).

Engaging with the well-known Israeli high-tech industry is particularly well-suited to helping it achieve one of Vision 2021’s leading goals: becoming a ‘competitive knowledge economy’. The Digital Economy Strategy, launched in 2022, aims to increase the digital economy’s contribution to the UAE’s GDP from 9.7% in 2022 to 19.4% over the next decade. It also aims to enhance the UAE’s position as a leading hub for the digital economy, both regionally and globally (United Arab Emirates Government, 2024).

To achieve these goals, the UAE has established funds and venture capital to invest in foreign firms and attract foreign investment to help establish tech hubs. Israeli firms have already joined some of these innovative programs, and UAE sovereign wealth funds have already invested in venture capital firms in the Israeli tech sector (Lieber, 2022). In 2022, The Wall Street Journal reported that the UAE’s sovereign wealth fund, Mubadala, had invested over $100 million in several Israeli venture capital firms. According to the report, senior executives from Mubadala met with approximately 100 different investors before selecting these funds. Notably, some of the chosen funds had also invested in Emirati startups, highlighting the bidirectional nature of the economic relationship (Jones and Liber, 2022).

Following the normalization, UAE officials stated that collaborating with Israel could stimulate innovation in other areas, including health engineering, water desalination, space, and advanced agriculture technologies (Shulman, 2021). These sectors are all outlined in Vision 2021 and are the main pillars of more recently announced visions, such as “The UAE Energy Strategy 2050.”

In a more disaggregated approach to the accords’ expected economic potential, some publications have highlighted the sectors in which Israel and the UAE complement each other. One straightforward way to identify a country’s export strengths is to measure its Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) across various product categories. RCA is calculated by dividing a country’s export share of a specific product by the global export share of that same product. RCA-based comparisons suggest that Israel is a natural importer of plastics, aluminum, cement, and other goods from the UAE, which the UAE re-exports. Conversely, Israel is well-positioned to meet the UAE’s strong demand for medicines, medical electrodiagnostic devices, electrical machinery, chemical products, and arms and ammunition, all of which rank high on Israel’s export list or boast high RCA scores. Both sides can also benefit from two-way trade in products that each imports and re-exports on a large scale, such as telecommunications equipment and automatic data-processing machines (Atradius Group, 2021; Rivlin, 2021). The demand and supply for many of these goods are reinforced by the UAE’s strategy to position itself as a cutting-edge technology, manufacturing, and trade hub.

Israel is one of the 11 countries with which the UAE has signed or declared its intention to sign CEPAs. This is part of its strategy to consolidate its position as a global hub for trade, investment, and the digital economy. According to the UAE’s trade minister, these countries were carefully chosen, and deepening integration with them would help make the UAE a “gateway to the world” (Kohli and Cokulan, 2022; Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022).

The UAE is already a major re-export point connecting various markets and intermediary supply chains. Its recent efforts to establish free trade agreements with additional partners and reduce tariffs aim to develop the country’s trade and investment networks and strengthen its position as a “global trade and logistic hub” (United Arab Emirates, Ministry of Economics, 2023).

Based on the empirical evidence in the network literature, such processes are expected to reduce the likelihood that the UAE would initiate conflict. However, their pacifying effect goes beyond reducing the likelihood of conflict. Its current position in global trade networks and its ambition to strengthen its position as a global hub for advancing innovation are key factors behind its and Israel’s strong expected economic benefits of peace.

Notably, about 79% of the UAE’s current total exports to Israel are comprised of goods re-exported from third parties (Emirati Federal Competitiveness and Statistics Centre, 2025). Israel expects the UAE to become a strategic point from which Israeli goods will be re-exported to various countries in Asia. Israeli officials also hope that the flow of Israeli goods re-exported from the UAE will help deepen the existing unofficial economic and political relations with other Gulf states (Al Lawati, 2022).

As explained in the theoretical sections, a country that establishes economic relations with a new trade partner might have the incentive and ability to deepen the economic and political engagement between this new trading partner and other countries connected to it through networks of strategic and economic ties. The UAE is already playing the role of an actor that helps promote communication between Israel and other states in the region. In 2021, the UAE, Jordan, and Israel signed an MOU to advance a clean energy and sustainable water desalination project. According to the MOU, an Emirati government-owned firm, Masadr, would build a solar photovoltaic plant in Jordan that would produce clean energy for export to Israel, which, in return, would export water to Jordan (Maher, 2022).1

In February 2022, Israel agreed to expand the amount of natural gas exported to Egypt through a new trade route that crosses via the existing pipeline in Jordan (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022). Israel and Egypt had conducted fruitful deals in the gas sector prior to the Abraham Accords, and the recent export expansion is not directly attributable to them. However, the UAE became relevant in Israel’s gas sector after Delek Drilling sold its 22% stake in the Mediterranean Tamar gas field to Abu Dhabi’s government-owned Mubadala Petroleum.

Following the Negev Summit, the UAE, Israel, Bahrain, Morocco, Egypt, and the United States established a new cooperative framework called the “Negev Forum,” which aims to “build a new regional network enabling broad cooperation in a variety of fields of common interest” (US Department of State, 2022). The central location of the UAE in the global network and its commercial and political influence have also been featured in other, more ambitious visions for possible future joint regional projects. For example, Israel’s current and former high-ranking officials often touted the idea of opening a land bridge of trade between Europe and the Gulf via Israel and Jordan (Ben-Shabbat, 2022, p. 16).

Discussion

One of the declared goals of many of the UAE’s policies is to diversify the sources and number of importers of essential goods, thereby reducing reliance on any key trade partner. Therefore, in line with the argument that globalization reduces the deterrent power of trade, one might argue that the UAE’s pro-globalization policy reduces the likelihood that integrating with Israel would entail opportunity costs significant enough to make breaking the normalization unthinkable.

While this might be the case, the UAE’s pro-globalization policy increased the appeal of integrating with Israeli firms during the pre-normalization period. More evidently, it is a leading variable in shaping strong expectations for future economic engagement and in developing broad-based transnational ties, which are among the characteristics of a warm peace.

The case demonstrates that when setting different stages in the transition to peace as a dependent variable, higher exposure to the globalization process can have a substantial pacifying effect. Even when security concerns are prioritized over economic ones, economic interactions can play an important role in paving the way for peace agreements and stabilizing them after they are signed. Furthermore, the case highlights the importance of the growing body of research that uses network analysis to examine the pathways through which trade integration reduces conflict. While this line of research empirically investigates how different characteristics of trade networks reduce the likelihood of aggression, the case demonstrates that some of these characteristics positively affect the ability to stabilize peace through economic interactions and expand their positive externalities to other states in the network.

As with every study that relies on a single case study, the attempts to generalize beyond the case and develop broader theoretical concepts are limited. The fact that Israel and the UAE have never been engaged in a direct war between them raises questions about the ability to generalize from this case to the ability of economics to facilitate the transition to peace between enemies that have been engaged in actual fighting. Nevertheless, the role of economic factors in pushing toward normalization between these two old rivals and the momentum that the Abraham Accords generated in promoting broader cooperation in a very complex region might support the logic that economic cooperation can help lead to peace, at least between the many countries that have less hostility and fewer constraints on their desire to reconcile.

Conclusion

Three decades after Shimon Peres famously presented the vision of the “New Middle East,” there is renewed popularity and interest in fostering peace in the Middle East through economic cooperation. In one of the dozens of economic conferences that have taken place after the Abraham Accords were signed, the CEO of one of Israel’s largest banks echoed the “New Middle East” narrative, stating that, “If in the past peace agreements were signed between neighboring countries in order to achieve protection and security, today peace is being signed mainly for economic reasons” (Spiro, 2020).

This is one of many statements that incorrectly downplay the strategic domain while highlighting the economic domain. The case presented here highlights that economic and strategic explanations for peace should not be regarded as competing domains, but rather as complementary domains that amplify each other’s importance.

Since the original “New Middle East” concept was coined, the academic literature exploring whether trade fosters peace has made substantial progress. Nonetheless, policymakers, officials, and analysts who rely on scholarly research to support the notion that the economic domain can play a facilitative role in the regional peace process will find it challenging to substantiate this claim based on these studies.

The study highlights that the link between a state’s exposure to globalization and peace is more complex than the recent literature suggests. While recent research suggests that globalization reduces the deterrent power of trade, this study demonstrates that increased economic integration may create a range of economic incentives for two particular states to improve their relations.

Ironically, the voices repeating the “trade brings peace” notion in the context of the Arab-Israeli conflict are doing so when the economic system is shifting, with more countries adopting policies focused on relative rather than absolute gains. Our study suggests that one consequence of the so-called backlash against globalization may be a reduction in the likelihood of reaching and stabilizing peace agreements.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. All data used for the figures and discussion are cited within the text and reference list. Figure source files can be provided upon request.

Author contributions

NF: Writing – original draft. CL: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Due to the deterioration in Israel-Jordan relations following the Gaza war, the progress of this project is currently on hold.

References

Al Lawati, A. (2022). How the UAE went from boycotting Israel to investing billions in its economy. CNN. Available online at: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/06/01/business/uae-israel-trade-deal-mime-intl/index.html.

Al-Rashdan, L. (2024). Israel aerospace to set up freighter shop in Abu Dhabi. Bloomberg. Available online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-08-12/israel-aerospace-to-convert-emirates-planes-in-mideast-expansion.

Archibugi, D., and Iammarino, S. (2002). The globalization of technological innovation: definition and evidence. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 9, 98–122. doi: 10.1080/09692290110101126

Arieli, T., and Kahn, Y. (2019). Transforming regions of conflict through trade preferential agreements: Israel, Jordan and the QIZ initiative. Peace Econ. Peace Sci. Public Policy 25:20180032. doi: 10.1515/peps-2018-0032

Atradius Group. (2021). Israel–UAE peace treaty: Great for trade, but long-term value will take time to develop. Atradius Economic Research. Available online at: https://group.atradius.com/publications/economic-research/israel-uae-trade-relations.html.

Barbieri, K. (2002). The Liberal illusion: Does trade promote peace? Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ben-Shabbat, M. (2022). The Abraham accords at year two: A work plan for strengthening and expansion. The Jerusalem Strategic Tribune 6, 14–20. doi: 10.1111/fpa.1205

Black, I. (2019). Just below the surface: Israel, the Arab Gulf States and the limits of cooperation. London: LSE Middle East Centre Report.

Bouillon, M. (2004). The failure of big business: on the socio-economic reality of the Middle East peace process. Mediter. Polit. 9, 1–28. doi: 10.1080/13629390410001679900

Brutger, R., and Marple, T. (2024). Butterfly effects in global trade: international borders, disputes, and trade disruption and diversion. J. Peace Res. 61, 903–916. doi: 10.1177/00223433231180928

Bussmann, M. (2010). Foreign direct investment and militarized international conflict. J. Peace Res. 47, 143–153. doi: 10.1177/0022343309354143

Bussmann, M., and Schneider, G. (2007). When globalization discontent turns violent: foreign economic liberalization and internal war. Int. Stud. Q. 51, 79–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00440.x

Chen, F. R. (2021). Extended dependence: trade, alliances, and peace. J. Polit. 83, 246–259. doi: 10.1086/709149

Chen, Q., and Zhou, Y. (2021). Whose trade follows the flag? Institutional constraints and economic responses to bilateral relations. J. Peace Res. 58, 1207–1223. doi: 10.1177/0022343321992825

Copeland, D. C. (1999). Trade expectations and the outbreak of peace: détente 1970–74 and the end of the cold war 1985–91. Secur. Stud. 9, 15–58. doi: 10.1080/09636419908429394

Dent, E. (2025). Israel-UAE defense cooperation grows under the Abraham accords. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Available online at: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/israel-uae-defense-cooperation-grows-under-abraham-accords

Diehl, P. F., Goertz, G., and Gallegos, Y. (2021). Peace data: concept, measurement, patterns, and research agenda. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 38, 605–624. doi: 10.1177/0738894219870288

Dorussen, H., and Ward, H. (2010). Trade networks and the Kantian peace. J. Peace Res. 47, 29–42. doi: 10.1177/0022343309350011

Dreher, A. (2006). Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization. Appl. Econ. 38, 1091–1110. doi: 10.1080/00036840500392078

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2022). Israel and Egypt collaborate on natural gas development. Available online at: https://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1830749566

Emirati Federal Competitiveness and Statistics Centre. (2025). Statistics by subject. Available online at: https://fcsc.gov.ae/en-us/Pages/Statistics/Statistics-by-Subject.aspx.

Fatima, S. T. (2017). Globalization and technology adoption: evidence from emerging economies. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 26, 724–758. doi: 10.1080/09638199.2017.1303080

Feldman, N., Eiran, E., and Rubin, A. (2021). Naval power and effects of third-party trade on conflict. J. Confl. Resolut. 65, 342–371. doi: 10.1177/0022002720958180

Fehrs, M. (2016). Letting bygones be bygones: rapprochement in US foreign policy. Foreign Policy Anal. 12, 128–148.

Fehrs, M. (2024). Making up is hard to do: reconciliation after interstate war. Int. Politics, 1–31. doi: 10.1057/s41311-024-00565-w

Friedman, R. (2010). Israelis doing business in Dubai will wait out storm. The Jerusalem Post. Available online at: https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Israelis-doing-business-in-Dubai-will-wait-out-storm.

Fulton, J., and Yellinek, R. (2021). UAE–Israel diplomatic normalization: A response to a turbulent Middle East region. Comp. Strateg. 40, 499–515. doi: 10.1080/01495933.2021.1962200

Gartzke, E., and Li, Q. (2003). Measure for measure: concept operationalization and the trade interdependence–conflict debate. J. Peace Res. 40, 553–571. doi: 10.1177/00223433030405004

Gartzke, E., and Westerwinter, O. (2016). The complex structure of commercial peace: contrasting trade interdependence, asymmetry, and multipolarity. J. Peace Res. 53, 325–343. doi: 10.1177/0022343316637895

Gartzke, E., Li, Q., and Boehmer, C. (2001). Investing in the peace: economic interdependence and international conflict. Int. Organ. 55, 391–438. doi: 10.1162/00208180151140612

Goertz, G., Diehl, P. F., and Balas, A. (2016). The puzzle of peace: The evolution of peace in the international system. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gowa, J., and Hicks, R. (2017). Commerce and conflict: new data about the great war. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 47, 653–674. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000289

Gowa, J., and Mansfield, E. D. (1993). Power politics and international trade. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 87, 408–420. doi: 10.2307/2939050

Grossman, M. (2024). As the Israel–Hamas war continues, the Abraham accords quietly turns four. Atlantic Council, MENASource. Available online at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/abraham-accords-anniversary-gaza/

Guzansky, Y., and Marshall, Z. A. (2020). The Abraham accords: immediate significance and long-term implications. Isr. J. Foreign Aff. 14, 379–389. doi: 10.1080/23739770.2020.1831861

Halevi, Y. K., Al-Nuaimi, A., Stroul, D., and Ross, D. (2025). October 7, two years on: repercussions for Israel, the Middle East, and U.S. policy. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Available online at: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/october-7-two-years-repercussions-israel-middle-east-and-us-policy

Hegre, H., Oneal, J. R., and Russett, B. (2010). Trade does promote peace: new simultaneous estimates of the reciprocal effects of trade and conflict. J. Peace Res. 47, 763–774. doi: 10.1177/0022343310385995

IMF. (2023). United Arab Emirates: Selected issues (IMF Country Report No. 23/224). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available online at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/06/22/United-Arab-Emirates-Selected-Issues-535076

IMF. (2025). IMF DataMapper: United Arab Emirates GDP, current prices (NGDPD). Available online at: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/ARE?year=2023

Israel CBS. (2025). Available online at: https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/cbsNewBrand/Pages/Foreign-Trade-Statistics-Monthly.aspx

Jones, C., and Guzansky, Y. (2017). Israel's relations with the Gulf states: toward the emergence of a tacit security regime? Contemp. Secur. Policy 38, 398–419. doi: 10.1080/13523260.2017.1292375

Jones, C., and Guzansky, Y. (2020). Fraternal enemies: Israel and the Gulf monarchies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kahn, Y., and Arieli, T. (2020). Post-conflict normalization through trade preferential agreements: Egypt, Israel and the qualified industrial zones. Peace Econ. Peace Sci. Public Policy 26:20190020. doi: 10.1515/peps-2019-0020

Kinne, B. J. (2012). Multilateral trade and militarized conflict: centrality, openness, and asymmetry in the global trade network. J. Polit. 74, 308–322. doi: 10.1017/S002238161100137X

Kinne, B. J. (2014). Does third-party trade reduce conflict? Credible signaling versus opportunity costs. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 31, 28–48. doi: 10.1177/0738894213501135

Kleinberg, K. B., Robinson, G., and French, S. L. (2012). Trade concentration and interstate conflict. J. Polit. 74, 529–540. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611001745

Kohli, A. S., and Cokulan, C. (2022). UAE to sign trade deals with 8 countries; seize new investment opportunities. Khaleej Times. Available online at: https://www.khaleejtimes.com/business/uae-to-sign-trade-deals-with-8-countries-seize-new-investment-opportunities.

Kupchan, C. A. (2010). How enemies become friends: The sources of stable peace. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lieber, D. (2022). Israel signs free-trade agreement with U.A.E. In first-of-its-kind deal with Arab state. The Wall Street Journal. Available online at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/israel-signs-free-trade-agreement-with-u-a-e-in-first-of-its-kind-deal-with-arab-state-11654048054.

Livne, S. (2025). UAE carriers prove lifeline for Israeli travelers. Globes. Available online at: https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-uae-carriers-prove-lifeline-for-israeli-travelers-1001521650.

Maher, M. (2022). Two years on, the Abraham accords bear fruit. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Available online at: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/two-years-abraham-accords-bear-fruit.

Martin, P., Mayer, T., and Thoenig, M. (2008). Make trade not war? Rev. Econ. Stud. 75, 865–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-937X.2008.00492.x

Mattes, M., and Weeks, J. L. (2024). From foes to friends: the causes of interstate rapprochement and conciliation. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 27, 185–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-041322-024603

Miller, B. (2005). When and how regions become peaceful: potential theoretical pathways to peace. Int. Stud. Rev. 7, 229–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2486.2005.00482.x

UAE Ministry of Economy and Tourism (2025). International trade map. Available online at: https://www.moet.gov.ae/en/international-trade-map.

Nissenbaum, N. (2022). Israel’s defense industry is big winner two years after Abraham accords. The Wall Street Journal. Available online at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/israels-defense-industry-is-big-winner-two-years-after-abraham-accords-11665360600.

Pernes, J., and Möller, U. (2014). Coming together over trade? A study of the resumed dialogue between India and Pakistan. Asian Security 10, 221–240. doi: 10.1080/14799855.2014.976615

Peterson, T. M. (2015). Insiders versus outsiders: preferential trade agreements, trade distortions, and militarized conflict. J. Confl. Resolut. 59, 698–727. doi: 10.1177/0022002713520483

Podeh, E. (2022). The many faces of normalization: models of Arab–Israeli relations. Strat. Assessm. 25, 55–78.

Polachek, S. W., Seiglie, C., and Xiang, J. (2011). “Globalization and international conflict: can FDI increase cooperation among nations?” in The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Peace and Conflict, 733–762.

Polachek, S., and Xiang, J. (2010). How opportunity costs decrease the probability of war in an incomplete information game. Int. Organ. 64, 133–144. doi: 10.1017/S002081830999018X

Press-Barnathan, G. (2006). The neglected dimension of commercial liberalism: economic cooperation and transition to peace. J. Peace Res. 43, 261–278. doi: 10.1177/0022343306063931

Ravid, B. (2022). Trump’s peace: The Abraham accords and the reshaping of the Middle East. Yedioth Ahronoth. [In Hebrew].

Ripsman, N. M. (2016). Peacemaking from above, peace from below: Ending conflict between regional rivals. New York: Cornell University Press.

Rivlin, P. (2021). The UAE and Israel: Developing relations and the challenge ahead. Tel Aviv, Israel: Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel Aviv University. Available online at: https://dayan.org/content/uae-and-israel-developing-relations-and-challenge-ahead

Rubinovitz, Z., and Rettig, E. (2018). Crude peace: the role of oil trade in the Israeli-Egyptian peace negotiations. Int. Stud. Q. 62, 371–382. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqx073

Russett, B. M., and Oneal, J. R. (2001). Triangulating peace: Democracy, interdependence, and international organizations. New York: W. W. Norton.

Sadeh, T., and Feldman, N. (2020). Globalization and wartime trade. Coop. Confl. 55, 235–260. doi: 10.1177/0010836719896613

Schneider, G. (2014). Peace through globalization and capitalism? Prospects of two liberal propositions. J. Peace Res. 51, 173–183. doi: 10.1177/0022343313497739

Schneider, G. (2023). “Economics and conflict: Moving beyond conjectures and correlations” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Shulman, S. (2021). ‘We’re both nations of problem-solvers,’ says UAE minister. CTech. Available online at: https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/en/article/r1KjAQy1u.

Skare, M., and Soriano, D. R. (2021). How globalization is changing digital technology adoption: an international perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 6, 222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2021.04.001

Spiro, J. (2020). Today, peace is being signed mainly for economic reasons,’ says Bank Leumi CEO. CTech. Available online at: https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/articles/0,7340,L-3876851,00.html.

Srivastava, D., and Rahul, M. (2023). Network analysis of trade and FDI. SN Business Econ. 4, 4–15. doi: 10.1007/s43546-023-00606-1

The Economist. (2023). Can Israeli–Emirati business ties survive the Gaza war? Available online at: https://www.economist.com/business/2023/11/02/can-israeli-emirati-business-ties-survive-the-gaza-war.

The World Bank. (2023). Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) – United Arab Emirates. Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?locations=AE.

The World Bank. (2024). Doing business archive 2004–2020. Available online at: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/en/data.

Thompson, W. R., Sakuwa, K., and Suhas, P. H. (2022). Analyzing strategic rivalries in world politics. Singapore: Springer.

Traub, D., Cohen, R. A., and Kertcher, C. (2023). The road to normalization: the importance of the United Arab Emirates’ neoliberal foreign policy in the normalization with Israel, 2004–2020. Digest Middle East Stud. 32, 60–78. doi: 10.1111/dome.12286

Turak, N. (2024). BP and Abu Dhabi’s Adnoc suspend major purchase in Israeli gas firm. CNBC. Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/03/13/bp-abu-dhabis-adnoc-suspend-major-purchase-in-israeli-gas-firm.html

United Arab Emirates, Ministry of Economics. (2023). Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreements | Ministry of Economy - UAE. Available online at: https://moec.gov.ae/

United Arab Emirates Government. (2024). Digital Economy Strategy. Available online at: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/finance-and-economy/digital-economy-strategy

US Department of State. (2022). The Negev forum regional cooperation framework adopted by the steering committee (November 10, 2022). Available online at: https://www.state.gov/the-negev-forum-working-groups-and-regional-cooperation-framework

Vakil, S., and Quilliam, N. (2023). The Abraham accords and Israel–UAE normalization: Shaping a new Middle East. London: Chatham House. Available online at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/2023-03-28-abraham-accords-israel-uae-normalization-vakil-quilliam-1.pdf.

Keywords: commercial liberalism, peace through globalization, Abraham Accords, United Arab Emirates, Israel

Citation: Feldman N and Lutmar C (2025) Give “peace through globalization” a chance: the role of economic globalization in UAE-Israel normalization. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1622709. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1622709

Edited by:

Carlos Leone, Open University, PortugalReviewed by:

Arie Marcelo, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, IsraelJohn J. Chin, Carnegie Mellon University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Feldman and Lutmar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nizan Feldman, bmZlbGRtYW5AcG9saS5oYWlmYS5hYy5pbA==

Nizan Feldman

Nizan Feldman Carmela Lutmar

Carmela Lutmar