- Department of Social Sciences and Business, Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

Although Denmark is often regarded as a forerunner in terms of gender equality, Denmark still has no dedicated gender studies departments. Departing from this puzzling fact, this article asks how researchers working in Denmark understand, analyze, and investigate gender and gender structures in Denmark. We conduct a hermeneutic literature review, focusing on research produced between 2008–2023, and demonstrate that most research analyzing gender in Denmark belongs to four broad theoretical categories organized around institutional theories, citizenship theories, interactionism, and masculinities. Furthermore, we find some evidence that the absence of gender studies departments in Denmark contributes to an ongoing separation between political science and sociological research investigating similar topics. However, we show that the traveling concept of intersectionality unites research analyzing gendered inequalities in Denmark but note that authors seldom understand or use intersectionality in the same way. The article concludes by arguing that although the use of intersectionality has enriched research examining gender in Denmark, enabling research to illuminate different inequalities, research must also better account for the specificities of the Danish welfare state to understand the operation of power and continuing gender inequality in Denmark.

1 Introduction

Around the world, anti-feminist movements are on the rise. Conceptualized at times as backlash movements (Alter and Zürn, 2020; della Porta, 2020), these political groups, parties, and social movements increasingly engage in attacks on academic disciplines like gender studies, sociology, and political science, target researchers who challenge our preconceptions surrounding gender, and contribute to the growth of ongoing moral panics about transgender individuals and their rights. Denmark is no exception to this trend. Researchers at Danish universities have increasingly found themselves subject to attacks from anti-feminist movements and their adherents. These attacks have even reached the Danish parliament, and in 2021, the Danish parliament adopted a motion criticizing researchers who study topics like gender, ethnicity, and migration as activists rather than scientists. Amidst these developments in our political arenas, researchers have increasingly recognized and emphasized the need for a stronger focus on the gendered character of the social world and better analyses of how gender structures, discourses, and norms promote, limit, or prevent forms of social action and organization (Fiig, 2019; Hvenegård-Lassen et al., 2020). As part of this increased awareness and recognition, fields like feminist STS, feminist International Relations, and feminist Criminology have grown in both number and influence, and we have witnessed the increasing prominence of gender studies as a discipline, with the establishment of increasing numbers of specialized Bachelor’s, Master’s, and doctoral programs as well as the institutionalization of academic departments. However, here, Denmark is an exception. In stark contrast to its Scandinavian neighbors Sweden and Norway, Denmark still has no dedicated gender studies departments and there are few opportunities for students to study courses or programs specializing in gender studies.

Although gender studies may lack an institutional foothold at Danish universities, research examining gender takes place in other departments and disciplines in Denmark. In this article, we investigate how researchers in Denmark understand, explore, and analyze gender, gender structures, and gender-based needs and consider how the institutional framework of Danish universities affects this research. Our analysis focuses particularly on how the characteristics of Danish society may or may not influence conceptualizations surrounding gender and explore whose voices and whose needs these conceptualizations highlight. Based on an exploratory literature review (Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2021), we find that researchers examining gendered inequalities in Denmark have clear theoretical and methodological preferences. However, we find little evidence that this research focuses on specifically Danish problems, needs, or topics relating to gender. Instead, we find that an increasing number of concepts have traveled to Denmark and taken on a Danish tint, allowing researchers to view Danish society through a new lens but also restricting access to certain particularly Danish phenomena. Considering these findings, we argue that the institutional structure of Danish universities limits the opportunities for researchers to develop theoretical perspectives and concepts rooted in the specificities of Danish society. We conclude in noting that while traveling concepts have clearly enriched and sharpened Danish discussions surrounding gender, understanding the role of gender in Danish society also requires concepts and theories that take the particularities of Denmark into account.

This article therefore proceeds as follows. First, we present our approach to our literature review, and briefly outline both our choices and their potential consequences. Second, we discuss the Danish institutional landscape, highlighting that research examining gender in Denmark tends to occur along two parallel disciplinary tracks. Third, we present the results of our literature review, discussing the most prominent theories, methods, and topics within the literature and highlighting the prominence of traveling concepts like intersectionality in this field. Fourth, we examine the use of intersectionality in Denmark, considering both why it has achieved a hegemonic position within research on gender in Denmark and the consequences of this development. Fifth, we consider the work of Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín (2017, 2019, 2020), and argue that their approach, developed in specific reference to Denmark, reveals different aspects of Danish society than work centered around traveling concepts. Finally, the article concludes by arguing that while research investigating gendered inequalities in Denmark has benefited from the increasing incorporation of traveling concepts, these analyses must be more clearly situated in Denmark to fully exploit these concepts both academically and politically.

2 Exploring Danish gender research

Literature reviews are a vital component of any research process. When conducting a literature review, we must make choices about search terms, scholars, topics, and even which texts to read. This is particularly the case when we explore a topic as vast as research on gender in Denmark. Due to the extensive corpus of texts that exist, we cannot claim to have conducted a comprehensive or systematic literature review, where we have identified “all relevant records” (Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2021, p. 139). However, we agree here with Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic (2010) that systematic literature reviews are neither necessarily desirable nor achievable, particularly within social-scientific fields. Instead, we have pursued a strategy more in line with the hermeneutic approach these authors propose (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010, 2014). A hermeneutic approach primarily views literature reviews as “a continuing, open-ended process through which increased understanding of the research area and better understanding of the research problem inform each other” (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010, p. 130). Conducting a literature review thus becomes an exercise in the hermeneutic circle, making the literature review an “iterative process that can be described by moving from the whole of all (identified) relevant literature to particular texts and from there back to the whole body of relevant literature” (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2010, p. 134). However, as any hermeneutic philosopher would tell us, a key aspect of this processual understanding of literature reviews regards how we began.

Our initial research question was vague and open-ended, concerned with exploring how gender was studied in Denmark in the last 15 years. We operationalized ‘the study of gender’ here as texts which are concerned with problematizing, questioning, or understanding different types of gender hierarchies and structures. Although we did not initially make any methodological, theoretical, or empirical distinctions, as we progressed, we ruled out texts where gender was only used as a categorical variable. This had the effect of removing a substantial portion of the quantitative literature regarding gender in Denmark from consideration. We argue that this choice is justified as we are not concerned with empirical descriptions of the situation of, for example, women in Denmark regarding wages, educational achievements, or birth rates, but rather with how the influence of gender is understood, examined, and explained amongst Danish scholars. Thus, for example, while we do not include articles that solely present statistics relating to wage levels in Denmark, we do include in our review Christina Fiig’s (Fiig, 2010a, 2018; Fiig and Verner, 2016) work on gender segregation in Danish politics and business life as she (and her co-author) attempt to explain and understand where gender differences arise.

After making these initial distinctions, we worked to acquire an overview of the field, through reading review articles (e.g., Dahlerup, 2015), exploring issues of Kvinder, Køn, og Forskning, and conversations with leading scholars in the fields of political science and sociology. From these early investigations, we identified a list of prominent gender scholars in Denmark and of prominent themes in the literature. In parallel, we also identified a list of topics, themes, and fields apparent in research on gender in other countries and traditions. From these three lists, the authors then collected over 150 texts (books, journal articles, and book chapters, primarily) to read. After reading these texts, the authors then performed a second round of selection, narrowing the texts under review to 70, based on perceived importance, scholarly merit, and representativeness. The authors then reread the chosen texts, and categorized them according to theoretical tradition, methodological approach, and topic. Through this process, we argue that we have obtained a clear overview of research focusing on gender structures and hierarchies in Denmark, and that our literature review enables us to “examine and critically assess existing knowledge in a particular problem domain, forming a foundation for identifying weaknesses and poorly understood phenomena, [and] enabling problematization of assumptions and theoretical claims in the existing body of knowledge” (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2014, p. 258).

3 Researching gender in Denmark

Research never takes place within a vacuum. Instead, researchers always find themselves working within a specific historical, institutional, and cultural setting which influences not only who does research but also how that research is conducted. In this section, we therefore provide an overview of the Danish research setting, identifying certain elements of this landscape that affect research examining gender. The Danish higher education sector contains eight universities and employs about 18,000 individuals as researchers (with about 3,000 of these employed in the social sciences)1. Danish universities are firmly embedded in the global higher education field and international rankings relating to quality and prestige now play an important role in Danish higher education. However, as late as the early 2000s, Danish politicians and policymakers exhibited skepticism towards the importance of university rankings (Lim and Williams Øerberg, 2017). Yet, Lim and Williams Øerberg (2017) demonstrate that this skepticism swiftly transformed into an embrace of university rankings, and Denmark adopted an explicit political goal of achieving high positions in international rankings around this time. This focus on rankings has had stark ramifications for university funding and university research in Denmark. Warren (2024, p. 41) notes, for example, that universities have implemented ‘internal mechanisms [that] encourage’ academics to direct their efforts towards activities that rankings reward. These mechanisms influence both how research is done in Denmark and what is perceived as ‘good’ research. Research in Danish has particularly declined, as researchers in Denmark find themselves in an international arena which privileges “knowledge published in English out of the metropole, at the expense of knowledges, knowers and languages from the periphery” (Rowlands and Wright, 2022, p. 584). These developments have also affected which journals researchers publish in, which topics they study, and which concepts they use (Rowlands and Wright, 2022; Warren, 2024). Researchers in Denmark today find themselves in a university sector concerned with securing international prestige and reputation. This setting privileges research in English and aimed at epistemic communities centered in English speaking countries. As we will discuss further below, these institutional factors have clear influence on the type of research on gender produced in Denmark.

While the international higher education field influences Danish research, national research infrastructure also affects gender research in Denmark. As we noted above, Danish universities still have no gender studies departments. However, Denmark does have several centers for gender research such as the Center for Gender, Sexuality, and Difference at Copenhagen University, the Center for Gender, Power, and Diversity at Roskilde University, and until 2022, FREIA-the Center for Gender Research at Aalborg University. These centers are usually interdisciplinary, counting amongst their members sociologists, political scientists, and others. Similarly, the most prominent gender studies journal in Denmark, Kvinder, køn, og forskning describes itself as an interdisciplinary journal that ‘aims to provide a meeting place for the exchange of gender research results and discussions.’2 Yet, despite these interdisciplinary efforts, in our literature review, we identify two clear disciplinary tracks, belonging to political science and sociology. Within the political science track, for example, we find studies of gender and institutions primarily, where authors focus on topics such as internal processes in political parties, gender quotas, and forms of citizenship. Conversely, in the sociological track, authors cover a greater variety of empirical areas, examining issues such as masculinity in Denmark, feminist activism, and parenthood in Denmark, but perform few studies of bureaucracies or organizations.

We argue that this divergence has its roots in the institutional setting. As no gender studies departments exist, gender researchers still primarily find themselves in departments oriented primarily towards political science or sociology. Political science and sociology have important differences in disciplinary conventions. Sociologists and political scientists receive different training, have different standards of evidence, and often focus on understanding different aspects of social life. At the same time, a puzzling aspect of this divergence relates to the few overlaps between these different tracks. For example, Dahlerup (2013b) and Siim (2016), located within the political science track, each discuss the role feminist social movements play and have played in changing discursive frames within Danish politics, with Dahlerup even incorporating concepts drawn from the social movement field into her work at times. Yet, when we examine studies of current social movements belonging to the more sociological track such as those from Christensen (2010), Stoltz et al. (2019), or Stoltz (2021), these studies do not appear to be in conversation with the studies occurring in the political science track. Similarly, while Bloksgaard et al. (2015), Ravn (2018), and Leine et al. (2020) all explore current Danish masculinities from different angles, we see little to no research exploring performances of masculinity within political parties, government institutions, or public discourses in the political science track. Despite the interdisciplinary forums that exist, these two tracks still appear to mostly exist in parallel. Political scientists remain mainly focused on the traditional areas of political science inquiry, analyzing large-scale gender issues in formal institutions in relation to processes like globalization or neo-liberalism, but neglecting the importance of interactional dynamics and studies of meso-or micro-level processes. Sociological research, conversely, frequently examines gender at the micro-level, producing important studies on everyday life and interaction, but often fails to link these processes to the broader context of Danish society and the changing character of modern society.

We argue therefore that the disciplinary background of Danish gender researchers exerts an important influence on the type of research done. Whether researchers find themselves in a more sociologically-or political science-oriented space matters for the type of research they do. At the same time, while institutional factors contribute to keeping these tracks separate, certain traveling concepts appear to bridge some of these gaps. We therefore now turn towards the results of our literature review and present the primary theoretical and methodological approaches we identify.

4 Research on gender in Denmark

In our literature review, we identify clear preferences for certain theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of gender. We also identify certain prominent areas of empirical focus amongst the works we review. In this section, we present these results and discuss some of their consequences.

4.1 Theory

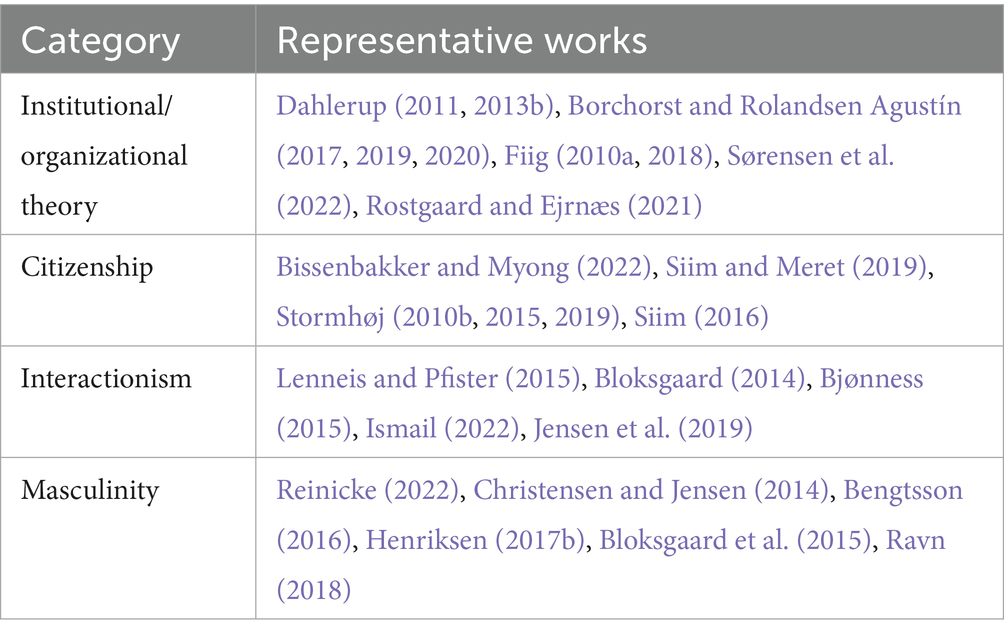

We start with a brief presentation of the most common theoretical approaches we identify. We categorize most of the works we reviewed within four broad theoretical categories (see Table 1). The first category includes work using institutional or organizational theories, best characterized by Dahlerup’s work on levels of representation (Dahlerup, 2013a) or Fiig’s work on women in the upper levels of formal organizations (Fiig, 2010a). Texts in this category primarily study the role of gender in Danish institutions, with different authors focusing on actors, organizations, or macro-structures. The second category contains works that study citizenship, almost exclusively using the theories of Nancy Fraser and Nira Yuval-Davis, and best exemplified by the works (Siim, 2013, 2016; Stormhøj, 2015, 2019). Within this category, scholars have primarily investigated barriers to full participation in Danish society and have increasingly attempted to incorporate conflict and contradiction into their analyses of belonging, rather than viewing social groups as homogenous. Each of these categories focuses on structural barriers to equality, enriching our understanding of what obstacles to full participation for all exist.

The third category consists of works using interactionist theory, investigating gender through the concepts of Goffman or West and Zimmerman, as in Bjønness’s (2015) exploration of motherhood or Ismail’s (2022) work on gender and elderly care. These works cover a broader variety of empirical topics and tend to investigate how ideas and norms surrounding gender are constructed, maintained, and resisted in everyday life. Finally, we also see a growing number of studies in the field of masculinity studies, employing concepts like hegemonic masculinity or hyper-masculinity, such as the work of Reinicke (2022) or Bengtsson (2016). Works in this fourth category primarily examine ideals of masculinity currently existing in Denmark, and how these relate to the broader patriarchal character of Danish society. Clearly, however, not all works exploring gender structures in Denmark fit neatly into these four categories. For example, we identify some notable outliers such as Dahl’s (2017) work on elderly care, Bindesbøl Holm Johansen et al.’s (2019) employment of gossip to examine gender and sexual norms, and Sandager and Ravn’s (2023) use of affect to study gender and educational imaginations. At the same time, within the field of research on gender in Denmark, we argue that most works belong to the four categories identified above.

As we noted above, gender scholars in Denmark tend to find themselves in department oriented more towards political science or sociology. Unsurprisingly, then, when we consider these four categories, we find clear preferences amongst political scientists for the first two categories while sociologists tend to use the theories belonging to categories three and four. Similarly, we find little cross-over or conversation between these categories. Since works in different theoretical traditions reveals different aspects of gendered relations and structures, we suggest that gender research in Denmark would benefit from increased exchange across these categories and disciplines. Concepts drawn from sociology, anthropology, or gender studies can shed new light on the traditional inquires of political science, while political science perspectives can similarly highlight different aspects of the social world for sociologists. The findings or theories of researchers who study macro-structures or processes can better inform those who examine more micro-issues, while work on large scale processes like globalization, neo-liberalism, or political system change can be better related to the concrete events and interactions that make up social life. Furthermore, as gender is an ever-present in social settings, extending the study of the performance or doing of gender to further areas would enable us to better understand how gender performances change, and how settings allow actors more or less freedom to do gender.

Yet, although we find little interaction between these different theoretical categories, we do find one commonality across these works. Namely, (almost) all authors and works above categorize themselves as intersectional. This categorization is present across all theoretical categories (including outliers), suggesting that intersectionality is a common denominator in (current) Danish gender research. However, despite this common identification, we also wish to emphasize the numerous meanings of intersectionality across these works. It is only a slight exaggeration to suggest that no two authors appear to understand intersectionality in the same way. While we will return to this point further in Section 5, we want to highlight that the common conceptual denominator in Danish research on gender is a traveling concept, rather than anything specific to the Danish environment or society.

4.2 Method

Methodologically, the most common approach we see in our literature review analyzes various forms of texts (defined broadly here, including images) as part of a discourse or document analysis. A variety of researchers analyze different forms of public documents, such as government reports, party manifestos, or policy documents (e.g., Bertelsen and Sørensen, 2019; Jørgensen, 2018; Madsen and Rolandsen Agustín, 2018; Stormhøj, 2021) while others examine texts from media sources (e.g., Christensen and Siim, 2010; Fiig, 2010b). These methods allow researchers to examine how discourses circulate and change in Denmark and similarly permit scholars to analyze how different decisions are justified in various government agencies or formal organizations. However, these methods are difficult to use to examine everyday life, and often only allow researchers to make arguments or analyses at the structural level due to their lack of contact with social actors. We also see the use of other approaches that focus on the structural level, and providing descriptions of broad trends in Danish society, such as survey-based approaches or the use of register data (e.g., Dahlerup, 2018; Dahlerup et al., 2021; Fiig and Verner, 2016).

In contrast to these approaches, we see a variety of approaches that utilize a more participant-centric method such as focus groups (e.g., Bloksgaard et al., 2015; Ravn, 2018), interviews (e.g., Boroumand, 2022; Rolandsen Agustín et al., 2023), and observations or ethnography (e.g., Bengtsson, 2016; Henriksen, 2017a). These methods are particularly favored within the sociological track we discussed above, with almost all ethnographic work occurring amongst criminologists. While we recognize that ethnographic methods carry with them several challenges in the form of time, resources, and access, we nonetheless believe that our understanding of gender structures in Denmark would benefit from more long-term studies, in many more areas. For example, in their article exploring gender representation amongst political parties in Denmark, Rolandsen Agustín et al. (2023, p. 40) note that “party organizations realize that women tend to disappear from local party politics when they start a family… party culture thus needs to facilitate their continued participation in order to attract this particular age group.” We argue that this finding provides a perfect jumping off point for a more in-depth study of party culture and gender. However, studying party culture, or the culture of any organization, requires researchers to engage more with the members of a given organization, and to spend more time in these settings. In relation to women’s representation, we suggest that more ethnographic studies are needed to gain a better picture of the daily aspects of party culture, institutional culture, or family culture that hinder the participation of women (and men) in different societal spheres. Particularly, we suggest that we need to learn more about how women (and men) negotiate and balance family life, friendship, and other obligations in their daily lives. Learning more about these negotiations would enable us to understand more about how gendered structures are recreated, reproduced, and challenged in everyday life, and allow us to better understand how power operates in Denmark.

While our understanding of participation in the formal spheres of Danish society would benefit from more in-depth interview and ethnographic studies, we wish to emphasize that we continue to need further analyses using other methods as well. However, greater methodological variety would help us to uncover further obstacles, challenges, and practices that prevent equality and the full participation of all in Danish society.

4.3 Policy implications

Having explored the theoretical and methodological approaches preferred in researching analyzing gender in Denmark, we now turn our attention to the areas of empirical focus apparent in this research. We also aim to discuss the policy solutions researchers propose. In the literature, we find extensive texts examining gender quotas (e.g., Dahlerup, 2013a; Rolandsen Agustín et al., 2018, 2020), gender gaps (e.g., Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín, 2020; Fiig and Verner, 2016), and gender mainstreaming (e.g., Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín, 2019; Madsen and Rolandsen Agustín, 2018). While some of these texts offer few solutions or proposals to achieve greater equality in Danish society, Madsen and Rolandsen Agustín (2018) suggest that the gender mainstreaming process in Denmark could be improved with a different approach to gender impact assessments in Danish government institutions, with more involvement of both external and internal experts at different points in the policy making process. Similarly, researchers have extensively examined topics such as political representation (e.g., Dahlerup, 2018; Dahlerup et al., 2021; Meret, 2015), the relationship between gender and religion (e.g., Stormhøj, 2010a, 2010b), prostitution (e.g., Bjønness, 2012; Stormhøj et al., 2015), and feminist activism (e.g., Christensen, 2010; Siim and Stoltz, 2015; Stoltz et al., 2019). We also find substantial bodies of text exploring knowledge production (e.g., Childs and Dahlerup, 2018; Nielsen, 2015; Skewes et al., 2021; Utoft, 2021), the media (e.g., Fiig, 2010b; Møller Hartley and Askanius, 2021, 2022), and care (e.g., Dahl, 2017; Ismail, 2022). In many of these areas, we find few direct policy proposals. Instead, these authors often advocate for dramatic societal changes, such as an end to neoliberalism, or major cultural shifts.

Researchers have also substantially investigated parenthood in Denmark (e.g., Bloksgaard, 2014; Boroumand, 2022; Kielsgaard et al., 2018; Liversage, 2015; McKenna, 2022). Here, we do find some suggestions from, for example, Bloksgaard (2014), who suggests that fathers should not need to negotiate their parental leave with their workplace superiors. However, similar to the areas mentioned above, we also see that the authors suggest that cultural change in how Danish individuals perceive parental leave, motherhood, and fatherhood is required to achieve greater equality. We also find a number of works analyzing men’s violence against women and sexual harassment (e.g., Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín, 2017; Leine et al., 2020; Ravn, 2018; Reinicke, 2022). The authors examining these topics offer several suggestions for solutions, both small and large, including the establishment of an independent commission on sexual harassment, increasing teaching in schools, better statistics surrounding sexual harassment, and further political initiatives.

Nonetheless, when we discuss gender inequalities in Denmark, most research focuses on describing and understanding current inequalities, rather than on offering solutions for how to alleviate or solve these issues. While we do not necessarily view this as an issue, we do argue that the lack of direct solutions or policy proposals may also be related to the lack of specificity afforded to the Danish context in some research. To explore this argument further, we now turn towards the use of intersectionality in Denmark and contrast the use of intersectionality with a theoretical perspective developed within Danish society.

5 The travels of intersectionality in Denmark

As we have previously mentioned, our literature review identifies one factor that tends to unite the disparate research examining gender inequalities in Denmark. Namely, identifying as intersectional is a shared characteristic of recent gender research in Denmark, cutting across the divides previously outlined. The hegemonic position of intersectionality in gender research in Denmark today is a fairly recent development (Fiig, 2019; Stoltz et al., 2021). Hvenegård-Lassen et al. (2020), for example, show that the concept of intersectionality began to enter Danish and Nordic academic discussions around the year 2000, and that the use of intersectionality rapidly accelerated towards the end of the 2000s and the beginning of the 2010s. When we consider this development, three questions arise. First, in this section, we consider how researchers in Denmark understand intersectionality. Although the word intersectionality may be ubiquitous, this does not mean that all (or even any) researchers understand intersectionality in the same manner, and we find a wide variety of uses in the literature. After outlining prominent understandings of intersectionality in Denmark, we turn our attention towards the question of why intersectionality has become the common denominator of Danish gender research and consider some of the consequences of this development. While the increasing prominence of intersectionality has undoubtedly benefited Danish gender research, we nonetheless also suggest that the turn toward intersectionality has some notable limitations.

As we noted above, despite this common identification, gender researchers understand intersectionality very differently. For example, Henriksen (2017a, p. 492) uses intersectionality as a theoretical framework to examine “the gendered ethnicities of young women navigating multi-ethnic urban terrains defined as ghettos,” focusing on how gender and ethnicity interact in the lives of these young women. Henriksen (2017a, pp. 493–494) focuses on “the fluid, relational, and situational aspects of identification and categorization” and argues that “intersectional theory provides a framework for understanding not only how multiple structures of domination and identification shape women’s lives and dispositions but also how intersecting categories modify each other.” Henriksen’s intersectionality, then, emphasizes the situatedness of meanings and categorizations while at the same time attempting to account for broader structures of marginalization in our societies. Conversely, when we turn to the work of Christensen and Siim (2010, p. 8), their article begins with the lines: “Intersectionality is not a theory. In our view it is a methodological approach, which makes it possible to do multi-faceted analyses, which include multiple inequality categories.” This is an immediate contrast to the work of Henriksen. Christensen and Siim (2010, pp. 10, 12) continue in proposing an “analytical model which aims to structure intersectional analyses at macro, meso, and micro levels” arguing that “intersectionality is a tool to analyze the dynamic interactions of structures, institutions, and identities at different levels.” They demonstrate the use of this model in a brief analysis of the debate surrounding headscarves in Denmark, suggesting that while an intersectional analytical approach helps problematize our taken-for-granted assumptions about social categorizations, other uses of “intersectional arguments can be instrumentalized—and abused—in ways that serve exclusionary objectives” (Christensen and Siim, 2010, p. 15).

Although these intersectional approaches are similar, there are also important differences between viewing intersectionality as a theoretical approach or a method. Primarily, in Henriksen’s theoretical approach, intersectionality offers a flexible and fluid approach to identity, while in Christensen and Siim’s methodological approach, intersectionality becomes a tool for structuring analysis at different conceptual levels. In the first case, intersectionality is used as a theory of identity while in the second, intersectionality is an analytical strategy. This conflict regarding understandings of intersectionality is not unique to Denmark. Rather, as Collins (2015, p. 3) suggests, intersectionality is a “broad-based knowledge project” containing at least three separate strands: intersectionality as a field of study; intersectionality as an analytical strategy; and intersectionality as critical praxis. We even see examples of this third strand in the Danish literature, in for example Stoltz’s (2021) text on co-optation or Stoltz et al.’s (2019) chapter on feminist activism.

Intriguingly, then, Danish uses of intersectionality appear similar to the uses of intersectionality internationally. At the same time, there are important differences between the use of intersectionality in the Danish literature and particularly the North American literature. In a text reviewing the travel of intersectionality into the Nordic and European literature, Christensen and Jensen (2019) address a central criticism of Danish and European adoption of intersectionality. Within the Danish literature, intersectionality tends to focus on the analysis of complex identities rather than structures of power (Christensen and Jensen, 2019, pp. 20–22). The authors suggests that this shift has expanded the scope of intersectional analysis in Denmark, broadening the subjects of study beyond black women to include other (marginalized) groups—including white heterosexual men (Christensen and Jensen, 2019, p. 22). Crucially, Christensen and Jensen argue that this manner of interpreting the concept increases the relevance of intersectionality in a Danish context, opening up new analytic possibilities for researchers. These authors are not alone in suggesting that intersectionality must be adapted to a Nordic context, with, for example, Siim (2016) also advocating for the necessity of developing intersectional theory adapted to the particular challenges of the Nordics.

If we accept that intersectionality must be adapted to the Danish context, the questions that arise revolve around how and why intersectionality has become hegemonic in Danish gender research. While there are a variety of potential answers to this question, in this article, we restrict our focus to three developments relating to the Danish context. First, starting in the 1990s and 2000s, researchers in the Nordics increasingly recognized that concepts like state feminism and women-friendly policies (Hernes, 1987) were ill-suited for the analysis of life in and changes to the social-democratic welfare states. Borchorst and Siim (2008, p. 221), for example, argue that “the analytic potential of Hernes’ concepts, state feminism and women-friendly policies are challenged by increased diversity amongst women and men” and note that Hernes’s approach tends to assume common interests amongst all women. Retrenchment and recommodification have also changed the character of the social-democratic welfare states. Thus, Borchorst and Siim (2008, p. 222) advocate for the development of new approaches that still include “social and gender equality as key normative principles… [and] a strong norm about equal political representation along class and gender line” but that can also account for “equally important principles of securing equal representation for immigrants and granting recognitions for cultural diversity, including diversity amongst women.”

While these large changes to Danish society have influenced the increasing use of intersectionality, developments within the university sector in Denmark appear to play an equally important role in explaining the prevalence of the concept. As we discussed above, policies at Danish universities strongly encourage researchers to focus on international debates, publish in international journals, and produce knowledge that travels between countries and settings. In the international research field examining gendered inequalities, intersectionality has a dominant, if not a hegemonic, position (Carastathis, 2014). It is perhaps unsurprising that researchers working in Denmark, entangled within the global academic field, therefore examine gendered inequalities through intersectional lenses. The use of intersectionality grants legitimacy to researchers in international arenas, and simultaneously provides a common language for debates and intellectual exchange with others working in very different contexts.

Finally, at the local level, the institutional structure of Danish universities also seems to play a role in explaining the prevalence of intersectionality. We demonstrated above that research examining gender in Denmark still tends to occur within separate disciplinary tracks. In this context, the term intersectionality acts as a common denominator across a landscape of gender research marked by disciplinary divides. We see this feature of intersectionality exemplified in works from, for example, Ravn (2018), Siim (2013), and Stormhøj (2019). While all three authors explicitly use intersectionality, their work differs substantially in terms of disciplinary orientation. Ravn (2018) uses intersectionality to conduct a micro-sociological analysis of identity, grounded in empirical data from focus group interviews while Siim (2013) uses intersectionality to produce a macro-political science analysis of the challenges of immigration and gender politics in the Nordic welfare states. Stormhøj (2019), finally, uses intersectionality to develop sexuality-related political theory in the field of political philosophy.

Clearly, there are other developments outside the scope and focus of this paper that have also influenced the adoption of intersectionality in Danish gender research. However, in the remainder of this paper, we chose instead to focus on some of the consequences of this adoption. The incorporation of intersectionality into Danish gender research has clearly strengthened and sharpened analysis of gendered inequalities in Denmark. However, we suggest that the widespread incorporation of traveling concepts like intersectionality risks losing the opportunity to develop needed theoretical perspectives and concepts rooted in the specificities of Danish society, such as the institutional approach we discuss in the following section. While intersectionality has enriched our understanding of gender in a Danish context, we argue that adopted concepts should be accompanied by locally grounded theoretical perspectives. In the following section, we explore one approach in the work of Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín (2017, 2019, 2020). We believe that these approaches allow us to understand aspects of gendered needs that international approaches, such as intersectionality, do not always capture. We suggest, therefore, that these perspectives are crucial for maintaining the relevance and importance of Danish gender research.

6 Danish structures of power

While intersectional frameworks enable researchers to uncover and examine different types of inequalities, frameworks based around traveling concepts also hide some of the specificities of Danish society. Denmark differs dramatically from the United States, and we argue that power does not operate along the same lines in a social-democratic welfare state as it does in a liberal welfare state. While we believe that intersectionality’s use has strengthened the analysis of (gendered) inequalities in Denmark, we also argue that researchers need to take the specificities of the Danish setting into greater account in their analyses. To illustrate the benefits of an approach more firmly rooted in Denmark, we therefore now briefly turn towards the work of Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín (2017, 2019, 2020) and their institutional approach. Although their work belongs to our first theoretical category, focused on institutional and organizational approaches, it has some important differences to other work in that category.

Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín analyze gender equality in relation to three different institutional arenas: the political, the trade union, and the legal. They argue that these arenas are ‘characterized by different regulations, key actors, and principals, which are conclusive for the ability for women’s organizations and other equality actors to influence gender equality policy’ (Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín, 2020, p. 56). In their work, these authors demonstrate that ‘entrenched institutions, like the Danish model of industrial relations, place clear limits on the possibilities for action’ and that the different arenas have, at different times, proved fertile ground for gender equality issues (Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín, 2020, p. 76). Although these authors identify their work as intersectional in other pieces, they do not focus on intersectionality here. Instead, they focus their analyses on the particularities of the Danish labor market. Through this three-pronged division, Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín uncover the ‘rules of the game’ in Denmark and show how these rules enable or limit actors in their attempts to achieve equality. In their analysis of sexual harassment, for example, they use this approach to arrive at the conclusion that the ‘Danish model is not well equipped to tackle sexual harassment’ even if ‘many sexual harassment settlements are reached’ (Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín, 2017, p. 174). This approach also enables them to explore how changes in one arena have consequences in the other arenas. Thus, when discussing the movement for equal wages, Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín (2020) demonstrate that increased efforts in the political arena led slowly to increased efforts in the trade union arena, rather than these two paths developing in parallel.

The use of this three-pronged institutional model has clear benefits in increasing our understanding of historical developments in Denmark. However, we wish to highlight that it also brings us closer to understanding power relations today, and, more importantly, to how we might change them. Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín’s approach focuses on the specificities of Denmark, which enables them to suggest policy changes that would help address inequalities. In terms of sexual harassment, for example, they suggest that Denmark needs better statistics, more registration of cases, and political initiatives that increase employer responsibility, amongst other suggestions (Borchorst and Rolandsen Agustín, 2017). The focused initiatives suggested here form a sharp contrast to the general suggestions present in our discussion surrounding policy recommendations above. We argue that these authors can make focused recommendations since their work is firmly rooted in the institutional context of Denmark. This context-sensitive approach enables not only more specific analyses but also more specific solutions. At the same time, however, we note that adding an intersectional perspective would further enhance this model. Clearly, experiences in these three arenas differ according to class, ethnicity, and sexuality, amongst other identity categories, and an intersectional perspective would allow authors to offer even more nuanced recommendations. Again, we wish to highlight that while intersectionality has enriched our discussions surrounding gender equality in Denmark, better situating intersectional perspectives in the context of the Danish welfare state would help us both better understand power relations in Denmark and change them.

7 Conclusion

In this article, we have examined how researchers have investigated gender, gender structures, and gendered inequalities in Denmark over the last 15 years. This is a vast field of literature. This article therefore focuses primarily on texts that are particularly important and/or representative of tendencies within the literature, allowing us to discuss this field in general terms. Similarly, our approach has focused on research produced at Danish universities and considered the consequences in terms of Danish society. Within these parameters, our literature review identifies four major theoretical approaches within the literature: an organizational or institutional category, a category focusing on citizenship, an interactionist approach, and an approach based in studies of masculinity. While these approaches all have their strengths and weaknesses, we highlighted that little interaction appears to occur between the different categories. Despite this lack of interaction, however, we find further evidence for the hegemonic position of intersectionality within Danish research surrounding gender.

Yet, although intersectionality may occupy a hegemonic position within this research field, we have emphasized that understandings of intersectionality are not shared across researchers, approaches, or disciplines. Instead, we have shown that researchers in Denmark, like those internationally, employ intersectionality as a theory, method, or practice in pursuit of different disciplinary goals. While intersectionality has different characteristics in different pieces of research, we have also argued that the intersectionality has achieved prominence partly due to both changes in Danish society and the policies of Danish universities. Despite the lack of gender studies departments in Denmark, intersectionality unites the disparate research surrounding gendered inequalities and allows researchers to speak with a common language.

However, while the use of intersectionality has greatly enriched analyses of gender inequalities in Denmark, the concept must still be properly situated within the specific setting of Denmark. Contextualizing intersectionality within the Danish institutional arena allows researchers not only to provide more nuanced analyses of power and better understand how inequalities are maintained in daily life. As we close, we wish to highlight the importance of researchers continuing to develop specific theories and approaches suited to examining the Danish and broader Scandinavian context despite institutional pressures to compete in a global academic game. Although we live in an increasingly globalized world, and must continue to study how inequalities are maintained or challenged at the international or global level, we must also remember to examine and analyze how the different cultures and histories of nations create different forms of gendered inequalities. We believe that it is only in remaining attentive to the specific features of the Danish landscape that we will be better able to understand continuing gender inequalities in Denmark, and more importantly, it is only through acting in reference to the structures of power in Denmark that we will be able to combat them.

Author contributions

CF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 101060836.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/emner/uddannelse-og-forskning/forskning-udvikling-og-innovation/forskning-og-udvikling

References

Alter, K. J., and Zürn, M. (2020). Conceptualising backlash politics: introduction to a special issue on backlash politics in comparison. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 22, 563–584. doi: 10.1177/1369148120947958

Bengtsson, T. T. (2016). Performing hypermasculinity: experiences with confined young offenders. Men Masculinities 19, 410–428. doi: 10.1177/1097184X15595083

Bertelsen, E., and Sørensen, W. Ø. (2019). Kønsneutralisering af intim partnervold? Soc Kritik: Tidsskr. Soc. Anal. Debat 158, 19–23.

Bindesbøl Holm Johansen, K., Pedersen, B. M., and Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. (2019). Visual gossiping: non-consensual ‘nude’ sharing among young people in Denmark. Cult. Health Sex. 21, 1029–1044. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2018.1534140

Bissenbakker, M., and Myong, L. (2022). Governing belonging through attachment: marriage migration and transnational adoption in Denmark. Ethnic Racial Stud. 45, 133–152. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2021.1876901

Bjønness, J. (2012). Between emotional politics and biased practices—prostitution policies, social work, and women selling sexual services in Denmark. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 9, 192–202. doi: 10.1007/s13178-012-0091-4

Bjønness, J. (2015). Narratives about necessity—constructions of motherhood among drug using sex-sellers in Denmark. Subst. Use Misuse 50, 783–793. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.978648

Bloksgaard, L. (2014). “Negotiating leave in the workplace: leave practices and masculinity constructions among Danish fathers” in Fatherhood in the Nordic welfare states. Bristol: comparing care policies and practice. eds. G. B. Eydal and T. Rostgaard (Policy Press), 141–162.

Bloksgaard, L., Christensen, A.-D., Jensen, S. Q., Hansen, C. D., Kyed, M., and Nielsen, K. J. (2015). Masculinity ideals in a contemporary Danish context. Nordic J. Feminist Gender Res. 23, 152–169. doi: 10.1080/08038740.2015.1046918

Boell, S. K., and Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. (2010). Literature reviews and the hermeneutic circle. Aust. Acad. Res. Libr. 41, 129–144. doi: 10.1080/00048623.2010.10721450

Boell, S. K., and Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. (2014). A hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 34, 257–286. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.03412

Borchorst, A., and Rolandsen Agustín, L. (2017). Seksuel chikane på arbejdspladsen: Faglige, politiske og retlige spor. Aalborg: Aalbor Universitetsforlag.

Borchorst, A., and Rolandsen Agustín, L. (2019). “Køn, ligestilling og retliggørelse: Europæiseringen af dansk ligestillingspolitik” in Europeisering av nordisk likestillingspolitikk. eds. C. Holst, H. Skjeie, and M. Teigen (Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk), 106–122.

Borchorst, A., and Rolandsen Agustín, L. (2020). “Ligestillingspolitikken i politiske, faglige og retlige spor” in Konflikt og konsensus. eds. A. Borchorst and D. Dahlerup (Frederiksberg: Frydenlund Academic), 55–82.

Borchorst, A., and Siim, B. (2008). Woman-friendly policies and state feminism: theorizing Scandinavian gender equality. Fem. Theory 9, 207–224. doi: 10.1177/1464700108090411

Boroumand, K. (2022). Lone motherhood and welfare feminism: a comparative case study of Iceland and Denmark. Soc. Polit. 29, 141–163. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxab036

Carastathis, A. (2014). The concept of intersectionality in feminist theory. Philos Compass 9, 304–314. doi: 10.1111/phc3.12129

Childs, S., and Dahlerup, D. (2018). Increasing women’s descriptive representation in national parliaments: the involvement and impact of gender and politics scholars. Eur. J. Polit. Gender 1, 185–204. doi: 10.1332/251510818X15272520831094

Christensen, A.-D. Resistance and violence: constructions of masculinities in radical left-wing movements in Denmark. NORMA, (2010), 5, 152–168. idunn.no.

Christensen, A.-D., and Jensen, S. Q. (2014). Combining hegemonic masculinity and intersectionality. NORMA 9, 60–75. doi: 10.1080/18902138.2014.892289

Christensen, A.-D., and Jensen, S. Q. (2019). Intersektionalitet – begrebsrejse, kritik og nytænkning. Dansk Sociol. 30:Article 2. doi: 10.22439/dansoc.v30i2.6038

Christensen, A.-D., and Siim, B. (2010). Citizenship and politics of belonging–inclusionary and exclusionary framings of gender and ethnicity. Kvind. Koen Forsk. 2, 8–17. doi: 10.7146/kkf.v0i2-3.28010

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41, 1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

Dahlerup, D. (2011). “Women in Nordic politics–a continuing success story?” in Gender and power in the Nordic countries, Editor. K. Niskanen, (Oslo: Nordic Gender Institute) 59–86.

Dahlerup, D. (2013a). “Denmark: high representation of women without gender quotas” in Breaking male dominance in old democracies. eds. D. Dahlerup and M. Leyenaar (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 146–171.

Dahlerup, D. (2013b). “Trajectories and processes of change in women’s representation” in Breaking male dominance in old democracies. eds. D. Dahlerup and M. Leyenaar (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 238–259.

Dahlerup, D. (2015). The development of Women’s Studies/gender studies in the social sciences in the Scandinavian countries. Stockholm University.

Dahlerup, D. (2018). Gender equality as a closed case: a survey among the members of the 2015 Danish parliament. Scand. Polit. Stud. 41, 188–209. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12116

Dahlerup, D., Karlsson, D., and Stensöta, H. O. (2021). What does it mean to be a feminist MP? A comparative analysis of the Swedish and Danish parliaments. Party Polit. 27, 1198–1210. doi: 10.1177/1354068820942690

della Porta, D. (2020). Conceptualising backlash movements: a (patch-worked) perspective from social movement studies. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 22, 585–597. doi: 10.1177/1369148120947360

Fiig, C. (2010a). A man’s world? Vertikal kønsfordeling i centraladministrationens departementer. Politica 42, 479–498.

Fiig, C. (2010b). Media representation of women politicians from a gender to an intersectionality perspective. Kvind. Koen Forsk. :Article 2-3, 41–49. doi: 10.7146/kkf.v0i2-3.28013

Fiig, C. (2018). Gendered segregation in Danish standing parliamentary committees 1990-2015. Femina Politica 27:Article 2. doi: 10.3224/feminapolitica.v27i2.09

Fiig, C. (2019). Skarpere med end uden? Kønsforskning og politologi. Politica 51:Article 1. doi: 10.7146/politica.v51i1.131102

Fiig, C., and Verner, M. (2016). Lige for lige? Kønssegregering i Folketingsudvalg og i ledelsen af det private erhvervsliv. Politik 19:Article 4. doi: 10.7146/politik.v19i4.27637

Gusenbauer, M., and Haddaway, N. R. (2021). What every researcher should know about searching – clarified concepts, search advice, and an agenda to improve finding in academia. Res. Synth. Methods 12, 136–147. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1457

Henriksen, A.-K. (2017a). ‘I was a scarf-like gangster girl’ – negotiating gender and ethnicity on the street. Ethnicities 17, 491–508. doi: 10.1177/1468796816666592

Henriksen, A.-K. (2017b). Navigating hypermasculine terrains: female tactics for safety and social mastery. Feminist Criminol. 12, 319–340. doi: 10.1177/1557085115613430

Hernes, H. M. (1987). Welfare State and Woman Power: Essays in State Feminism. Oslo: Norwegian University Press.

Hvenegård-Lassen, K., Staunæs, D., and Lund, R. (2020). Intersectionality, yes, but how? Approaches and conceptualizations in Nordic feminist research and activism. Nordic J. Feminist Gender Res. 28, 173–182. doi: 10.1080/08038740.2020.1790826

Ismail, A. M. (2022). ‘Doing care, doing gender’: towards a rethinking of gender and elderly care in the Arab Muslim families in Denmark. J. Relig. Spiritual. Aging 36, 56–68. doi: 10.1080/15528030.2022.2145413

Jensen, M. B., Herold, M. D., Frank, V. A., and Hunt, G. (2019). Playing with gender borders: flirting and alcohol consumption among young adults in Denmark. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 36, 357–372. doi: 10.1177/1455072518807794

Jørgensen, M. B. (2018). Dependent, deprived or deviant? The case of single mothers in Denmark. Polit. Gov. 6, 170–179. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i3.1436

Kielsgaard, K., Kristensen, H. K., and Nielsen, D. S. (2018). Everyday life and occupational deprivation in single migrant mothers living in Denmark. J. Occup. Sci. 25, 19–36. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2018.1445659

Leine, M., Mikkelsen, H. H., and Sen, A. (2020). ‘Danish women put up with less’: gender equality and the politics of denial in Denmark. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 27, 181–195. doi: 10.1177/1350506819887402

Lenneis, V., and Pfister, G. (2015). Gender constructions and negotiations of female football fans. A case study in Denmark. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 12, 157–185. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2015.11687961

Lim, M. A., and Williams Øerberg, J. (2017). Active instruments: on the use of university rankings in developing national systems of higher education. Policy Rev. High. Educ. 1, 91–108. doi: 10.1080/23322969.2016.1236351

Liversage, A. (2015). “Minority ethnic men and fatherhood in a Danish context” in Fatherhood in the Nordic welfare states. eds. G. B. Eydal and T. Rostgaard. 1st ed (Bristol: Bristol University Press), 209–230.

Madsen, D. H., and Rolandsen Agustín, L. (2018). Gender mainstreaming in the Danish central administration: (Mis) understandings of the gendered impact of law proposals. Kvinder Køn Forskning 4, 38–49. doi: 10.7146/kkf.v26i4.110557

McKenna, M. B. (2022). Constructions of families in the legal regulation of care. Kvind. Koen Forsk. 1, 33–49. doi: 10.7146/kkf.v32i1.128685

Meret, S. (2015). Charismatic female leadership and gender: pia Kjærsgaard and the Danish people’s party. Patterns Prejudice 49:81. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1023657

Møller Hartley, J., and Askanius, T. (2021). Activist-journalism and the norm of objectivity: role performance in the reporting of the #MeToo movement in Denmark and Sweden. J. Pract. 15, 860–877. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2020.1805792

Møller Hartley, J., and Askanius, T. (2022). “#MeToo 2.0 as a critical incident: voices, silencing, and reckoning in Denmark and Sweden” in Reporting on sexual violence in the #MeToo era. eds. A. Baker and U. Manchanda Rodrigues (Abingdon: Routledge), 33–47.

Nielsen, M. (2015). Limits to meritocracy? Gender in academic recruitment and promotion processes. Sci. Public Policy 43:scv052. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scv052

Ravn, S. (2018). “I would never start a fight but…”: young masculinities, perceptions of violence, and symbolic boundary work in focus groups. Men Masculin. 21, 291–309. doi: 10.1177/1097184X17696194

Reinicke, K. (2022). Men after# MeToo: Being an ally in the fight against sexual harassment. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rolandsen Agustín, L., Borchorst, A., and Teigen, M. (2020). Virksomhedskvotering i Danmark og Norge: Debatter om demokrati, retfærdighed og ligestilling in Konflikt og Konsensus. eds. A. Borchorst and D. Dahlerup (Frederiksberg: Frydenlund Academic), 109–136.

Rolandsen Agustín, L., Fiig, C., and Siim, B. (2023). “Practices and strategies of gender representation in Danish political parties: dilemmas of “everyday democracy.”” in Party politics and the implementation of gender quotas: Resisting institutions. eds. S. Lang, P. Meier, and B. Sauer (London: Springer International Publishing), 29–49.

Rolandsen Agustín, L., Siim, B., and Borchorst, A. (2018). Gender equality without gender quotas. Transforming Gender Citizenship, 400–423.

Rostgaard, T., and Ejrnæs, A. (2021). How different parental leave schemes create different take-up patterns: Denmark in Nordic comparison. Soc. Inclus. 9, 313–324. doi: 10.17645/si.v9i2.3870

Rowlands, J., and Wright, S. (2022). The role of bibliometric research assessment in a global order of epistemic injustice: a case study of humanities research in Denmark. Crit. Stud. Educ. 63, 572–588. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2020.1792523

Sandager, J., and Ravn, S. (2023). Affected by STEM? Young girls negotiating STEM presents and futures in a Danish school. Gend. Educ. 35, 454–468. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2023.2206841

Siim, B. (2013). Gender, diversity and migration—challenges to Nordic welfare, gender politics and research. Equal. Divers. Inclus. Int. J. 32, 615–628. doi: 10.1108/EDI-05-2013-0025

Siim, B. (2016). Feminist challenges to the reframing of equality and social justice. Nordic J. Feminist Gender Res. 24, 196–202. doi: 10.1080/08038740.2016.1246109

Siim, B., and Meret, S. (2019). “Dilemmas of citizenship and evolving civic activism in Denmark” in Citizens’ activism and solidarity movements: Contending with populism. eds. B. Siim, A. Krasteva, and A. Saarinen (London: Springer International Publishing), 25–50.

Siim, B., and Stoltz, P. (2015). Particularities of the Nordic: challenges to equality politics in a globalized world. In S. T. Faber and H. P. Nielsen (Eds.), Remapping gender, place and mobility (1st ed., pp. 19–34). Abingdon: Routledge

Skewes, L., Occhino, M., and Rolandsen Agustín, L. (2021). Making ripples and waves through feminist knowledge production and activism. Kvind. Koen Forsk. 2, 5–14. doi: 10.7146/kkf.v29i2.124891

Sørensen, A. E., Jørgensen, S. S., and Hansen, M. M. (2022). Half a century of female wage disadvantage: an analysis of Denmark’s public wage hierarchy in 1969 and today. Scand. Econ. Hist. Rev. 70, 195–215. doi: 10.1080/03585522.2021.1988698

Stoltz, P. (2021). “Co-optation and feminisms in the Nordic region: ‘gender-friendly’ welfare states, ‘Nordic exceptionalism’ and intersectionality” in Feminisms in the Nordic region: Neoliberalism, nationalism and Decolonial critique. eds. S. Keskinen, P. Stoltz, and D. Mulinari (London: Springer International Publishing), 23–43.

Stoltz, P., Halsaa, B., and Stormhøj, C. (2019). “Generational conflict and the politics of inclusion in two feminist events” in Intersectionality in feminist and queer movements. eds. E. Evans and E. Lepinard (Abingdon: Routledge), 271–288.

Stoltz, P., Mulinari, D., and Keskinen, S. (2021). “Contextualising feminisms in the Nordic region: neoliberalism, nationalism, and Decolonial critique” in Feminisms in the Nordic region: neoliberalism, nationalism and decolonial critique. eds. S. Keskinen, P. Stoltz, and D. Mulinari (London: Springer International Publishing), 1–21.

Stormhøj, C. (2010a). Køn, (u)ligebehandling og den danske folkekirke. Politik 13, 53–61. doi: 10.7146/politik.v13i1.27442

Stormhøj, C. (2010b). Women’s citizenship rights and the right to religious freedom. Nord. J. Relig. Soc. 23, 53–69. doi: 10.18261/ISSN1890-7008-2010-01-04

Stormhøj, C. (2015). Crippling sexual justice. Nordic J. Feminist Gender Res. 23, 79–92. doi: 10.1080/08038740.2014.993423

Stormhøj, C. (2019). Still much to be achieved: intersecting regimes of oppression, social critique, and ‘thick’ justice for lesbian and gay people. Sexualities 22, 1309–1324. doi: 10.1177/1363460718790873

Stormhøj, C. (2021). Danishness’, repressive immigration policies and exclusionary framings of gender equality. S. Keskinen, P. Stoltz, and D. Mulinari (S. Keskinen, P. Stoltz, and D. Mulinari Eds.). Feminisms in the Nordic region: neoliberalism, nationalism and decolonial critique (89–109). London: Springer International Publishing

Stormhøj, C., Pedersen, B. M., Hansen, K. G., Henningsen, I. B., and Rahm, T. (2015). Prostitution in Denmark: research and neoliberal public debates. Nordic J. Feminist Gender Res. 23, 220–226. doi: 10.1080/08038740.2015.1059364

Utoft, E. H. (2021). Maneuvering within postfeminism: a study of gender equality practitioners in Danish academia. Gend. Work. Organ. 28, 301–317. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12556

Keywords: Denmark, gender, gender inequalities, gender studies, intersectionality

Citation: Flaherty C and Petersen KP (2025) Examining gender inequalities in Denmark: traveling concepts, intersectionality, and social democracy. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1623152. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1623152

Edited by:

Alba María Aragón Morales, Pablo de Olavide University, SpainReviewed by:

Andreas Beyer Gregersen, Aalborg University, DenmarkMonika Eigmüller, University of Flensburg, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Flaherty and Petersen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Colm Flaherty, Y29sbWZAcnVjLmRr

Colm Flaherty

Colm Flaherty Katrine Ploug Petersen

Katrine Ploug Petersen