- The Levinsky-Wingate Academic College, Wingate Institute, Netanya, Israel

Purpose: This study examined a structured intervention designed to enhance intercultural competence and intergroup relations among Arab and Jewish students in a physical education teacher education (PETE) program in Israel.

Method: The 12-week ‘Roaming Course’ included 41 students (14 Arab, 27 Jewish), four study tours in mixed Arab-Jewish cities, and four on-campus sessions. Co-taught by an Arab and a Jewish instructor, the course integrated theoretical instruction, intercultural dialogue, and sport-based activities, drawing on the Contact Hypothesis, the Multi-Dimensional Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC), and the Sport for Development and Peace (SDP) framework. Qualitative data were collected from students’ reflective journals.

Results: Findings showed that structured intergroup contact in the PETE framework fostered trust, reduced prejudice, and enhanced intercultural awareness, empathy, and professional identity.

Discussion and conclusion: The study highlights sport’s role in bridging divides and presents a pedagogical model for higher education institutions promoting intercultural competence in diverse societies.

Introduction

One aim of higher education is to cultivate students’ intercultural communicative competence (ICC), or the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately with people from different cultural backgrounds, enabling them to navigate cultural differences and build meaningful relationships (Deardorff and Arasaratnam, 2017). This competence equips students with the tools necessary to successfully navigate the complexities of today’s global world. Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) often provide environments where individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds interact, creating opportunities for meaningful intercultural exchange (Deardorff and Arasaratnam, 2017; Guillén-Yparrea and Ramírez-Montoya, 2023; Guo and Jamal, 2007; Makarova, 2021). Such exposure allows students to engage with multiple perspectives, encouraging them to critically examine their own beliefs and assumptions, and develop key intercultural skills. This process fosters open-mindedness, negotiation skills, and the ability to navigate differences (Auschner, 2019; Hu and Kuh, 2003; Pike and Kuh, 2006). Through these experiences, HEIs can prepare students to engage constructively with difference, manage conflicts through dialogue, and collaborate effectively to reach mutual understanding (Hakvoort et al., 2022; Heleta and Deardorff, 2017; Jokikokko, 2021).

However, mere coexistence within a shared academic space does not guarantee meaningful intercultural learning (Groeppel-Klein et al., 2010). Research stresses the need for structured policies and curricula to support intergroup relations and ICC (Kudo et al., 2017). Most structured academic interventions aim to enhance the ICC of students from international contexts, whether between domestic and international students or through virtual exchange (Ramstrand et al., 2024). Recently, greater emphasis has been placed on “internationalization at home,” embedding ICC development into coursework to foster global citizenship (Jokikokko, 2021; López-Rocha, 2021). Still, less attention has been paid to structured efforts aimed at bridging divides among culturally diverse groups within the same national context.

Most ICC interventions have emerged from foreign language education (e.g., Galante, 2015; Liu, 2021). Yet, another discipline that has demonstrated significant potential in bridging cultural divides is sport (Coalter, 2009; Kidd, 2008). Sports-based interventions, which emphasize collaborative teamwork toward a common goal, have mainly targeted youth (Sugden and Tomlinson, 2017). While some research has also identified sport as an effective tool for fostering intercultural engagement among adults (Leitner et al., 2014; Litvak-Hirsch et al., 2016; Hellerstein et al., 2023), this area remains relatively underexplored.

This study addresses these gaps by examining a structured intervention aimed at enhancing intergroup contact and ICC among physical education teacher education (PETE) students from diverse intra-national backgrounds. By investigating guided sport-based engagement, it contributes to understanding effective strategies for fostering ICC in higher education.

Theoretical background

This study draws on three intersecting frameworks: the Contact Hypothesis (Allport, 1954), Byram’s Multi-Dimensional Model of ICC (1997), and the Sport for Development and Peace (SDP) movement.

The contact hypothesis

Cultural diversity in HEIs can foster engagement between culturally diverse social groups, challenging group boundaries and fostering mutual understanding. The Contact Hypothesis (Allport, 1954) posits that intergroup contact reduces prejudice and improves intergroup relations when four conditions are met: (1) equal status, (2) intergroup cooperation, (3) shared goals, and (4) institutional support.

Sharing academic spaces and collaborative projects have shown potential to reduce prejudice and build understanding among students (Bernstein and Salipante, 2017; Cheng and Zhao, 2007; Hendrickson, 2018; Hu and Kuh, 2003; Lin and Shen, 2020). Pettigrew and Tropp’s (2006) meta-analysis of over 500 studies affirmed the benefits of intergroup contact, especially when all four conditions are met within structured frameworks. The researchers explained that intergroup contact reduces anxiety about interactions and fosters empathy and perspective-taking, which mediate the reduction in prejudice.

However, Paluck et al. (2019) questioned the long-term impact of these interventions, many of which were short-term or contrived. While reaffirming that intergroup contact can have positive effects, they called for more rigorous research. Paolini et al.’s (2018) review of intergroup contact interventions concluded that while contact has the potential to improve intergroup relations and reduce prejudice, it is often avoided due to anxiety, thereby limiting its potential. Other scholars caution that contact can backfire, reinforcing stereotypes in unstructured settings where individuals self-segregate (Barlow et al., 2013; Reimer et al., 2017; Schrieff et al., 2016; Tredoux and Finchilescu, 2007). Conversely, structured programs have been criticized for failing to reflect the complexities of real-world interactions (Dixon et al., 2005).

Critiques also stress that contact is not universally beneficial, particularly in contexts of unequal power relations and ongoing conflict. As McKeown and Dixon (2017) argue, intergroup contact does not occur in a social vacuum; it is shaped by persistent inequalities, informal practices of segregation, and the possibility of “negative contact.” Positive encounters may even have paradoxical or “sedative” effects for disadvantaged groups, reducing recognition of injustice and willingness to mobilize for social change (McKeown and Dixon, 2017; Saguy et al., 2009). In such cases, contact can promote superficial harmony while leaving structural inequalities intact (Maoz, 2011). These insights highlight the need for caution when applying the Contact Hypothesis in divided societies, where power asymmetries and histories of conflict shape both the opportunities for and consequences of intergroup encounters.

Another line of critique points to the methodological reliance on quantitative self-report tools, most often pre- and post-questionnaires, shaped by researcher assumptions, prompting calls for qualitative studies that center participants’ voices (Blaylock and Briggs, 2023; Dixon et al., 2005; McKeown and Dixon, 2017).

In an attempt to address these challenges, the present qualitative study examines how a sport-based structured framework can foster meaningful intergroup contact over time among diverse intra-national students in a structured realistic HEI setting, while remaining attentive to the complexities and critiques outlined above. Unlike interventions that have been criticized for creating artificial, laboratory-like conditions through their structured design, this program moves beyond the laboratory by engaging students directly with diverse communities confronting these very conflicts. In doing so, it compels students to step outside their academic bubbles and cooperate across group boundaries in order to propose solutions to real-world challenges, while simultaneously questioning and reshaping their own assumptions.

The multidimensional model of ICC

Intercultural competence is a multimodal concept, often defined as the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately across cultures (Deardorff, 2006). Byram’s (1997) Multidimensional Model of ICC outlines five dimensions: (1) attitude—curiosity and openness to difference, and readiness to suspend disbelief; (2) knowledge—knowing about one’s own and others’ social practices, and knowledge of general societal and individual interaction; (3) Skills of discovery and interaction—acquiring and applying cultural knowledge in real-time encounters; (4) Skills of interpreting and relating—the ability to interpret products or events from another culture and relate them to one’s own; and (5) critical cultural awareness—the ability to critically evaluate perspectives, practices and products in one’s own and other cultural environments, based on objective criteria in a non-judgmental way.

This model has been widely used in designing ICC interventions (Coşkun, 2022; Kremer and Pinto, 2025; Shadiev et al., 2024). Although informal campus settings can foster cultural intelligence (Cheng and Zhao, 2007; Hendrickson, 2018; Lin and Shen, 2020), research shows students tend to self-segregate, forming monocultural groups that hinder intercultural growth (Auschner, 2019; Dunne, 2009; Harrison and Peacock, 2010; Nesdale and Todd, 2000; Volet and Ang, 2012). Engagement often declines over time, reinforcing negative attitudes (Lehto et al., 2014).

To address these challenges, structured ICC interventions, predominantly focused on foreign language curricula have shown promise in promoting ICC in physical classrooms (Coperías-Aguilar, 2009; Kusiak-Pisowacka, 2018), or through virtual exchange (O’Dowd and Dooly, 2020; Salih and Omar, 2021). Yet, these efforts frequently center on Anglophone exchanges (Çetinavci, 2011; Zhou et al., 2024) and lack broader institutional support (Bennett et al., 2013; Kudo et al., 2017). Other academic disciplines, including physical education, remain underexplored. This study aims to broaden the understanding of how ICC can develop beyond language learning in an intra-national context.

Sport for development and peace

Sport fosters intergroup contact by uniting participants around shared goals (Schulenkorf and Sherry, 2021). Recognizing this potential, the UN’s 2030 Agenda identifies sport as a tool for development and peace. The SDP movement seeks to leverage sport to enhance social and civic conditions, including education, social integration, and conflict resolution (Kidd, 2008; Sugden and Tomlinson, 2017; Svensson and Woods, 2017). Within this concept lies the broader aim of fostering ‘social cohesion’, defined as the willingness of members of a society to cooperate with one another to survive and prosper (Grimminger-Seidensticker and Möhwald, 2020), and ‘social responsibility’, which refers to the ethical framework that suggests individuals and institutions have an obligation to act for the benefit of society at large (Auschner, 2019).

While SDP typically addresses international contexts (Coalter, 2009), its potential to bridge divides within national contexts has also been explored. Sugden and Tomlinson (2017) implemented the Football for Peace initiative in Ireland, South Africa, and Israel, applying the Contact Hypothesis. They argued that for sport to positively impact intergroup relations, it must be intentionally structured around principles such as mutual respect, trust, responsibility, and inclusion. Most SDP interventions, however, have focused on children, primarily through soccer, the most popular sport among youth. This emphasis is justifiable, given that children are generally receptive to change (Schulenkorf and Sherry, 2021; Sugden and Tomlinson, 2017; Svensson and Woods, 2017). Still, such programs may overlook their potential impact on adults, who possess greater metacognitive awareness and capacity for critical reflection. Extending SDP interventions to adults could provide valuable opportunities for fostering deeper intercultural learning.

With the growing recognition of the need to enhance students’ ICC, interest in leveraging sport within physical education has increased. Puente-Maxera et al. (2020), for example, introduced culturally diverse games in a Spanish high school, improving students’ intercultural awareness. In higher education, Ko et al. (2013) explored a virtual exchange between Korean and American PE graduate students. Discussions on personal and educational topics led to growth in ICC attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors, based on Deardorff’s (2006) model.

Despite promising results, SDP research is often criticized for its reliance on short-term surveys and overemphasis on quantitative data (Darnell et al., 2018; Langer, 2015; Levermore, 2011). More qualitative research is needed to capture participants’ developmental experiences.

Building on prior findings, this qualitative study explores participants’ experiences and perceptions of a sports-based 12-week intervention aimed at enhancing intergroup relations and ICC among culturally diverse PETE students in Israel. To our knowledge, it is the first such intervention within PETE in the country.

Context

Israel has a diverse population of 10 million people. In 2024, 76.9% identified as Jewish, 21% as Arab, and 2.1% as belonging to other groups (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2024a). Among Arabs, 84% identified as Muslim, 8.5% Christian, and 7.2% Druze. Within the Jewish population 43.5% self-reported as secular, 31.2% traditional, 12.5% religious, and 11.3% Ultra-Orthodox (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2024b).

In 2022, this demographic distribution was reflected in higher education, where Arab students made up 20% of undergraduates (Haddad Haj-Yahya et al., 2022). However, prior to university, most children attend schools divided along cultural and geographic lines. In addition to independently funded schools, Israel’s public system comprises four main streams: state (secular), state-religious (Jewish religious), ultra-Orthodox, and Arab (Abbas et al., 2018). Other public services also largely cater to separate communities, limiting cross-cultural interactions. Language and political tensions further reduce opportunities for meaningful engagement between Jews and Arabs (Shapira and Fisher-Shalem, 2024; Smooha, 2010).

Higher education often marks the first meaningful contact between Arab and Jewish citizens. While it was once assumed that studying together would improve intergroup relations, research suggests otherwise. A 2018 survey found that students mostly socialized within their own groups, both in and outside class (Abbas et al., 2018). Similarly, Sky and Arnon (2017) reported no significant shift in intergroup attitudes after four years of shared study at a teacher education college.

A large-scale study of 4,679 Arab and Jewish students across 12 HEIs in Israel found minimal actual interaction between groups, despite shared classrooms (Aslih et al., 2020). Students rarely collaborated on academic tasks and often self-segregated. The researchers concluded that while HEIs in Israel have the potential to foster intergroup relations, this potential remains unrealized.

The Swords of Iron War, which erupted on October 7, 2023, has further deepened tensions and heightened fears among Arab and Jewish students, making efforts to promote engagement more difficult (Nassar et al., 2024). The current study examines an intervention conducted a year prior to the war, during a period already marked by recurring violence, which shaped the students’ experiences. The intervention may hold important implications for academic contexts in the post-war period.

Rationale and aim

The Roaming Course was designed to promote ICC through sport among PETE students from diverse backgrounds, primarily Arab and Jewish, and was implemented in the spring semester of 2021–2022. The course was part of the Israeli Hope in Academia initiative (Edmond de Rothschild Foundation), which supported over 500 students in 33 courses across Israel. The initiative aims to position higher education as a space for social cohesion, where diverse communities can come together to shape Israel’s shared future (Israeli Hope in Academia, n.d.). With this goal in mind, the course was created and implemented eight months after the May 2021 Uprisings, during a time of ongoing political violence (Fabian, 2022) which erupted at different times throughout the course period.

Three main questions guided this study:

1. In what ways did intergroup contact, based on the Contact Hypothesis, affect the experiences and perceptions of the participants?

2. In what ways did participation in the course facilitate ICC development?

3. What role did sport play in the processes that the participants underwent?

Methods

To address the research questions, a qualitative research approach was employed, utilizing an instrumental case study design (Cousin, 2005; Stake, 1995). This approach aligns with the study’s focus on understanding the developmental processes of the participants’ lived experiences and perceptions, providing insights into the intersection of the three theoretical frameworks applied. In keeping with the nature of qualitative research (Patton, 2014), the study does not aim to provide objective data or broad generalizability, but rather to foreground the subjective voices of students as they experienced the intervention, offering a window into how they perceived and made sense of their own processes.

Participants

The program was offered as an elective course within the students’ degree studies. Interested students applied by submitting a short written statement outlining their motivation for taking the course and their commitment to actively engaging in the process. Although the course was initially capped at 40 participants, all 43 applicants were accepted. Two students subsequently withdrew before the course began, citing their inability to meet the course requirements. Ultimately, a total of 41 undergraduate PETE students participated in the study, including 14 men (34%) and 27 women (66%), with an average age of 26.24 years (SD = 2.9). The group included 14 Arab (32%) and 27 Jewish (68%) students. Arab students included Muslim, Christian and Druze students, and Jewish students were religious and secular, of diverse ethnic backgrounds, including native Israelis of Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Ethiopian descent, as well as immigrants from the Former Soviet Union and the US. The course was co-taught by two instructors who also served as the study’s researchers: a Muslim Arab-Israeli athletics instructor and pedagogical mentor, and a Jewish American-Israeli English language and ICC instructor. Approval was granted by the institution’s Ethics Committee. Following an oral and written explanation of the study aims and option to decline, participants opted in by signing a consent form.

Program description

The course, titled ‘The Roaming Course: Sport as a Bridge Between Cultures,’ included eight sessions over a 12-week semester. Four were study tours to mixed Jewish-Arab cities—day trips to Lod and Jaffa, and a two-day visit to Acre and Haifa with an overnight stay in a youth hostel. These tours included visits to educational and community sites, meetings with local representatives, and physical activities with youth at schools or community centers.

The remaining four sessions were 90-min on-campus meetings. These introduced the theoretical frameworks of the Contact Hypothesis, ICC, and SDP and provided space to reflect on the tours and plan mixed-group student activities. For a detailed course description, see Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Throughout the semester, students submitted reflective journals in Hebrew after each tour, yielding 123 entries. Reflections were guided by open-ended prompts on impressions, teaching experiences, community interactions, and peer relations.

Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Lochmiller, 2021) was used to examine students’ written reflections through the lenses of the Contact Hypothesis, the Multi-Dimensional Model of ICC and SDP. Analysis followed Braun et al.’s (2016) six-phase process: (1) immersion, (2) coding, (3) theme generation, (4) development, (5) refinement, and (6) writing.

Each researcher independently read and coded the data using both inductive and deductive methods, allowing new insights to emerge beyond the original frameworks. Rather than seeking consensus, we shared our codes to offer diverse perspectives and enrich the analysis. Coding remained iterative and flexible (For a coding sample, see Appendix 2). After jointly reviewing the data using co-generated codes, we collaboratively refined overarching themes and subthemes. We then re-examined the data in light of these themes to finalize our interpretations. Selected journal excerpts were translated from Hebrew to English and back-translated to ensure accuracy (Tyupa, 2011).

Researcher positionality and reflexivity

Given the qualitative nature of the study and the thematic analysis applied, it is important to acknowledge the dual roles of the researchers, who also served as the course instructors. This insider positioning provided valuable contextual understanding and access to nuanced participant experiences. However, it may also have influenced data interpretation due to pre-existing relationships with the students and involvement in course delivery.

To minimize potential bias and enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, several steps were taken. The researchers engaged in reflexive dialogue throughout the course and the analysis process, critically reflecting on their own perspectives and interactions with the students. Peer debriefing with colleagues external to the course served as an additional perspective, encouraging examination of assumptions and enhancing analytical rigor. Furthermore, the independent coding process in analysis as above described, and diverse interpretations were discussed to broaden thematic insights rather than narrow them toward consensus. These strategies aimed to ensure transparency and maintain a critical awareness of how researcher positionality may have shaped the study’s findings.

Findings

The findings from the thematic analysis reveal insights into student experiences and perceptions over the 12-week course. To maintain confidentiality, student names are excluded, though their religious-ethnic backgrounds are included to understand how different perspectives interacted.

Contact hypothesis

Initial fears

A comparison of students’ reflections from the first and final tours reveals growing awareness of initial fears and a gradual reduction of prejudices. While early positive contact occurred through activities with elementary school children, deeper peer-to-peer connection developed more slowly.

During the first tour, students implemented sport activities they had co-designed in mixed groups at an Arab elementary school. For many Jewish students, it was their first time in an Arab school, an experience that challenged preconceptions:

“I started the day with many fears, but as the day progressed, and specifically at the school, the feeling changed and the fears disappeared.” (Jewish Ethiopian).

“Every time we hear about Arabs on TV, we hear about them in the context of throwing stones, Molotov cocktails… But the children we met were lovely and just wanted to play…I’d never met Arab children in my life, so I had a completely new experience.” (Former ultra-Orthodox Jew).

“I expected to meet children who would run amok and disturb us and would not connect with us. I discovered I held false prejudices; the children connected with us; They were very attentive and engaged.” (Religious Jew).

These initial fears appear rooted in limited exposure to and media-based stereotypes about Arab culture. Positive engagement with Arab children served as a turning point, beginning to dismantle these preconceptions.

Peer interactions also began to develop as expectations were countered. One Jewish student noted how receiving help with language barriers became moments of connection:

“The children did not know Hebrew, so I asked my partner to whisper the words in Arabic for me to say. The students were excited, and I learned new words.” (Religious Jew).

Arab students, too, reflected on shifting expectations:

“I was sure that the Jewish students would be reluctant to go into an Arab school and avoid interacting with the children, but some made a real effort… I admire [partner’s name]; he really made an effort to learn the words in Arabic and to connect with the kids. I did not expect it.” (Muslim Arab).

Peer division and missed opportunities

Not all experiences were positive. In some groups, Jewish students stepped back during activities, while their Arab peers led with minimal peer engagement. These mixed outcomes suggest that while some groups collaborated meaningfully, others needed more structured facilitation to build peer cooperation.

Interestingly, many students found engaging with local children easier than connecting with their peers. During lunch, students often sat in monocultural groups, reinforcing social boundaries.

“I expected a shared table at lunch, which unfortunately did not happen… I expected more work on our group and on the connection between us; if there’s a good relationship between us, we can become a model in the college and can help with college activities that encourage living together.” (Muslim Arab).

Students voiced disappointment about the limited dialogue, yet were reluctant to initiate interaction themselves:

“I expected to talk with the Arab students, to hear their opinions and listen to what they think, but it did not happen, which is disappointing. I look forward more to hearing the opinions of the Arab friends; to hear them talk and collaborate more; to show more willingness to approach us.” (Secular Jew).

These reflections point to openness to intergroup engagement, coupled with hesitation to take interpersonal risks. Students expected facilitators to create structured opportunities for dialogue, highlighting the need for intentional support to foster trust and interaction. Their responses underscore the critical role of institutional frameworks in shaping meaningful intergroup contact.

Perceptual shifts

By the end of the program, many students openly reflected on the evolution of their perceptions toward their peers. Jewish students, in particular, described how their initial prejudices were challenged through ongoing intergroup contact. This shift was especially significant given the tense national context in which the course began:

“I admit that when I came to the course, I held prejudiced views. Our course started during a tense period in Israel, and the tours took place only a day or two after severe attacks in which Jews, Druze and Arabs were also murdered. The atmosphere was very tense, and it was difficult to discuss and share our personal experiences… The meetings at the college helped us through the following days; I got to know my Arab peers and it became clear that they are smart, intelligent, inspiring.” (Religious Jew).

“The experiences in the course were accompanied by mixed emotions, a lot of confusion and lack of understanding …during the course, I saw a desire to connect. One Arab friend even invited me to iftar during Ramadan. For the first time, I realized there are Arabs who do not base their views on hatred as I’d been taught.” (Former ultra-Orthodox Jew).

These reflections demonstrate how structured, repeated contact disrupted existing stereotypes and created cognitive dissonance which led to a shift in perspectives. While Arab students expressed fewer shifts in prejudice, they described, like the latter reflection, moving from a sense of rejection, or belief that the other group viewed them negatively, to recognizing openness and support among Jewish peers:

“I’d experienced prejudice against me in the past when I was denied an internship at a kindergarten because I’m Arab. But one of the Jewish friends I made during the course tried to help me, and I realized not all Jews are against me.” (Muslim Arab).

Further expressions made among the Arab students related to an understanding that their peers are interested in equal rights and, in general, there are many organizations and people striving for equality and living in partnership:

“After all the violent eruptions, it’s easy to fall into hatred from both sides, but after this experience, we realized we are in this together and learned to appreciate each other.” (Muslim Arab).

Others noted increased awareness of shared efforts for equality:

“The significant differences between us, which at times are expressed in the most painful ways, were transformed in our course into positive situations that promote equality and a better future. We explored initiatives that promote equality between the two populations and contribute to shared living—at schools and among ourselves.” (Muslim Arab).

Integrated unity

Throughout the semester, students moved from social separation to a sense of unity. Initially, they remained in monocultural groups and expressed fears. By the final tour, many described a genuine bond:

“On the first two tours, I did not feel connected to my Arab peers. But by the last tour, we played tennis, hung out at night, laughed together. It’s the small moments that matter.” (Former Religious Jew).

“You can see that all the members of the group had one goal—to make it pleasant to live in our country, and we have a role as future physical education teachers. Despite our differences, we enjoyed working together and in cooperation, which we had not before at the college because we always went to our comfort zone—to friends we’d always known from our own group… After the final tour, we willingly chose to hang out together.” (Christian Arab).

Students recognized this development as a meaningful shift in group dynamics:

“At the start, we worked together out of necessity, but by Acre-Haifa tour, something shifted, and we felt an amazing bond… a sense of belonging; we come from different backgrounds and feel like one big and cohesive group.” (Secular Jew).

These reflections illustrate the transition from intergroup anxiety to social bonding through shared goals, underscoring the power of repeated, cooperative contact in fostering social cohesion. A shared sense of belonging emerged across group lines, reinforcing the potential of sustained intergroup engagement to reduce division and promote connection.

The multi-dimensional model of ICC

Knowledge and attitude

Following the first tour, many students realized how little they knew about each other’s cultures and the complexities of life in mixed cities. Both Arab and Jewish students expressed a desire to learn more.

“I was exposed to new knowledge…, especially about the Arab community, and I was glad to hear and be exposed to this side.” (Religious Jew).

“The community center director provided me with a wealth of knowledge about the social situation in Lod; I’d never thought about it before. I did not expect to return from the tour with such extensive knowledge, emotion and awareness.” (Muslim Arab).

This awareness sparked an affective and intellectual openness, shifting students from ignorance to curiosity. They were motivated to explore perspectives different from their own, a critical first step in developing intercultural competence.

Skills of discovery and interaction

Meeting with diverse mixed-city representatives enhanced students’ capacity to listen and engage with opposing views.

“I was interested in hearing the Arab side and the Jewish side to learn that not everything that appears in the media is true and that they do not present both sides; It’s good to really know what’s happening, to understand the fear between both sides.” (Christian Arab).

“I come from a home with very ‘extreme’ views…this was the first time I’ve heard the other side talking.” (Former ultra-Orthodox Jew).

Students reported learning to listen without necessarily agreeing, and several reflected on the challenge of confronting views that clashed with their own.

“I realized that we need to learn to listen to others, to be exposed to populations that we are not comfortable being with… After hearing opinions contrary to mine, and after the tour, I opened up to other thoughts. As a teacher, I understand that I’ll need to integrate in my teaching the importance of accepting the other and especially hearing the other’s opinion, even if it is less suitable for me.” (Religious Jew).

“I was interested in hearing each of the stories from the mouths of the different representatives. Each of them told slightly different things from their personal point of view. These enriched me and my knowledge, and left me with many thoughts I shared with my family and friends after the tour.” (Christian Arab).

The above reflection illustrates the ripple effect of exposure to diverse views beyond the classroom. Nevertheless, several students expressed the unease of listening to a contrary view.

“I was not pleased to hear from him [Jewish representative] that the Arabs are always the ones who start conflicts, even though it’s not true and there are always two sides, … and what he continued to say offended me a bit. “(Muslim Arab).

Another wrote of his difficulty to hear an Arab representative.

“… the meeting with him bothered me ideologically, because it goes against my ‘truth’, but I refrained from reacting and tried to hear and understand the other side. Looking back, I’m glad I was able to refrain and listen to an opinion that’s against my own.” (Religious Jew).

The discomfort students experienced when hearing opposing views reflects the early stages of intercultural learning. However, rather than avoiding such moments, the structure of the course encouraged active listening, followed by dialogue and reflection which gradually enabled students to develop tolerance of ambiguity. Students who initially remained silent later reported gratitude for the experience, suggesting they had navigated through initial resistance toward a more dialogic and empathetic stance. This transformation appears to be facilitated not only by the interpersonal contact itself but by the course’s design, which raised their awareness of the process taking place while providing support and safety.

This process prompted students’ curiosity and desire to expand knowledge, leading some of them to continue exploring mixed cities independently.

“After the tour, I drove around the city and even to Ramla [a mixed city near Lod] to experience it a little; it made me think about whether the situation that exists today can still change? And above all, do I want my children to grow up into the current reality?” (Secular Jew).

Once planted with the initial seeds of knowledge, and curiosity had been piqued, students experienced a sense of desire and confidence to continue the process independently. In addition, a reflexive process is demonstrated by students at each stage of the process.

Skills of interpreting and relating and critical cultural awareness

By the final tour, students showed progress in viewing situations from multiple perspectives. While this dimension emerged to a limited extent following the initial tour, they abound in entries after the final tour and show a much more in-depth and extensive process.

“The course opened up a different way of thinking for me; I can say that it empowered me in certain places and taught me how to see things differently and take the other’s story into account.” (Muslim Arab).

“Re-reading my diary entries, many points suddenly inter-connected; I realized how the course is actually a process of self-observation. In every situation we were in, I put myself in the shoes of one of the characters, and every time, I wonder again and again how I would react in the different situations.” (Secular Jew).

Several of the students explained that before the course, they did not discuss their views to avoid conflict or out of fear of the other’s reaction, leading them to remain silent and segregated. However, the ability to discuss difficult issues and express their views enabled each to better understand the other, bringing them closer together.

“…the course made us normalize Arab-Jewish discourse. Often, out of a desire to respect or not offend, we do not ask questions and therefore do not get to know people with a different way of life. When no questions are asked, lack of knowledge is formed; when there are question marks, there is alienation and fear. The open dialogue in the course is what I think is most important to preserve as human beings and as educators…” (Former Religious Jew).

Another student reflected on meaningful interaction:

“The course enabled me to talk about the differences, the difficulties, the wounds from all sides; it made me think more about the other side, and how it also sees things, and also if it sees how I see things and how I feel. I have Jewish and Arab friends outside the course who are of different religions or cultures and I’ve never seen any differences except for each person’s personality, but we also never talked about the things we discussed in the course and revealed the pain to each other, which helps strengthen the relationship.” (Muslim Arab).

One student related to a specific situation in which the ability to ask each other questions brought them closer.

“In Haifa, I could not go into the church we visited, and one of my Arab friends called me to join; I said ‘no, I cannot’, and I saw and felt the unpleasantness each of us experienced. He approached me and asked me why I had not gone in; it wasn’t like me to behave like that. So, I told him that I was glad he came to ask to understand the reason for my behavior; I explained that from a halachic [Jewish religious law] aspect, I’m not allowed to enter a church; there are things that I can be open to, while others are black and white, like keeping Kosher (thanks to the course I actually strengthened my Jewish identity with even more persistence and strictness). We ended the conversation with mutual understanding and respect.” (Traditional Jew).

The example above shows how an incident that could have led to a greater misunderstanding and distancing could be diffused due to the sense of trust and comfort to ask each other questions which previously they might have avoided. The ability to interpret and relate products and events from another culture to one’s own are possible in this instance by the other dimensions at play. The ability to ask questions and to learn from one another, driven by skills of discovery and interaction, led to enhanced knowledge and skills of interpreting and relating.

Students’ engagement with culture and identity issues in order to explain them to their peers of other cultures, led them to question and better understand their own. At the end of the process, one student questioned her own views and assumptions by trying to view them from the eyes of the student’s Jewish peers. Similar to the student in the earlier passage who felt she had strengthened her religious Jewish identity as a result of the process, this student also describes a process of self-questioning and better understanding of her identity as a Muslim Arab.

“Over the course of the semester, I began to ask myself if I’d been born Jewish in Israel, would I be left or right wing? How would I look at everything that was happening? And the course guided me to the answer; I discovered things about myself that I had not known before.” (Muslim Arab).

Critical cultural awareness, the culmination of the previous four dimensions, is illustrated when students described ‘making the strange familiar, and the familiar strange.’ In their reflections, students wrote about their attempts ‘to put themselves in the shoes of the other,’ questioning their own reactions from different stances, or ‘opening up to a new way of thinking’ by taking the other’s story into account. Developing this process led to a better understanding of their own identity.

These reflections indicate a developmental process, as the vast majority of students attributed the course participation to their enhanced ability to listen to diverse opinions, a better understanding of their worldview and self-identity.

Sport for development and peace: developing an activist PE teacher identity

A significant impression left on the students from the program was the realization that sport can be an effective tool in bridging between cultural divides. This recognition led them to reflect upon their professional identity and their role in implementing this tool as future educators. As a result of this gradual process, they developed an activist educator credo for social change through SDP principles.

“It was amazing to conduct the activity and see that the language is not an obstacle between me and the students at all. They did not care that I was Jewish and they were Arabs. They just joined in and played with me without thinking. It’s amazing to think that we as PE teachers have a place and an option to have such an influence. These are things that never occurred to me at all before this tour.” (Secular Jew).

The students’ experiences highlighted that sport transcends linguistic and cultural barriers. This statement underscores a critical mechanism of sport: its ability to facilitate non-verbal communication and shared experiences, which are essential for building understanding and trust among diverse groups. The SDP framework posits that sport can promote social cohesion by providing a neutral ground where individuals can engage without the weight of cultural identifiers. In this context, students experienced firsthand how collaborative sports activities fostered connections that would often be hindered in more formal or culturally charged settings.

“I teach dance and at that moment when the students and the children both the Arabs and Jews danced together it was such a moving moment, I was really on the verge of tears; it only strengthened the fact that I love my job so much and it could be a great opportunity for me to connect worlds without words.” (Secular Jew).

The selections above illustrate the students’ process of initial realization of the influence they have as PE teachers. The affective experiences shared by students further illustrate the significant emotional engagement involved in their learning, in addition to the cognitive understanding of diversity. This emotional engagement through intergroup connections can help dismantle stereotypes and foster a sense of belonging among participants, reinforcing the idea that sport can catalyze profound social change.

This understanding, as we can see in the selection below, led to a gradual development of their social activist identity as future educators:

“I realized that as a teacher my role is also to lead and create social change and to teach the children what is cooperation and acceptance of others. It is always possible to change and create a partnership between cultures.” (Druze).

When examining student reflections at the end of the program, a more profound understanding of the role of sport in bridging between cultures as their role as future PE teachers can be seen.

“When I first came to the course, I came a little closed up to the attempt to open my mind and understand that we live in a complex country and that there is a place for all religions. I can say today, after the course is over, I do think I managed to change my attitude and understand how much of a gap there is between the two sides and that sports and physical education can bridge this gap big time!” (Muslim Arab).

This reflection indicates a shift from viewing teaching solely as a technical skill, limited in its influence, to recognizing it as a platform for social activism. The course encouraged students to embrace a broader mission: to be agents of change who actively promote intercultural understanding and acceptance through their roles as educators.

Another student further explained how the practical experience, rather than keeping the concepts theoretical, helped crystallize for him as a future PE teacher how to implement the tool of sport to bridge between groups.

“There is something very simple in sports that removes a lot of masks and makes everyone just play. I’m not really interested in what the person in front of me believes, who he prays to or what he eats in the morning… I’m interested in him being a person who loves sports as much as I do and who wants to play a game with me for the fun. And it’s amazing to see it happening in practice and not just in the air with big words. Each of us has the ability to influence even a small group and make them believe in people thanks to sports.” (Secular Jew).

These selections illustrate that although the students realized at the end of the course the significance of gaining knowledge of difference and of embracing diversity, they nevertheless viewed sports as a form of removing difference or barriers and as a tool that makes its participants ‘the same,’ or rendering the differences irrelevant. Moreover, learning how to harness the tool of sport for integrating between Arab and Jewish children led to an evolution in the students’ professional identity, from the start of the course when the concept of agent of social change was introduced, to the end of the course, when the student adopts more profound core values as an educator, as can be seen in the following reflection:

“During the course, I found myself in a situation I had never experienced before, teaching and activating children from the Arab sector… As an educator, I now have a new professional credo, more upgraded than the previous one, and now as an educator I can reach additional goals that I had not thought about at all beforehand.” (Religious Jew).

These findings illustrate that the Roaming Course not only enhanced students’ understanding of intercultural dynamics but also fostered a profound sense of purpose in their roles as educators. By integrating SDP principles into their training, students recognized their potential to influence future generations. The shift from a technical understanding of a PE teacher to an activist educator identity marks a significant development in their professional trajectories.

Discussion

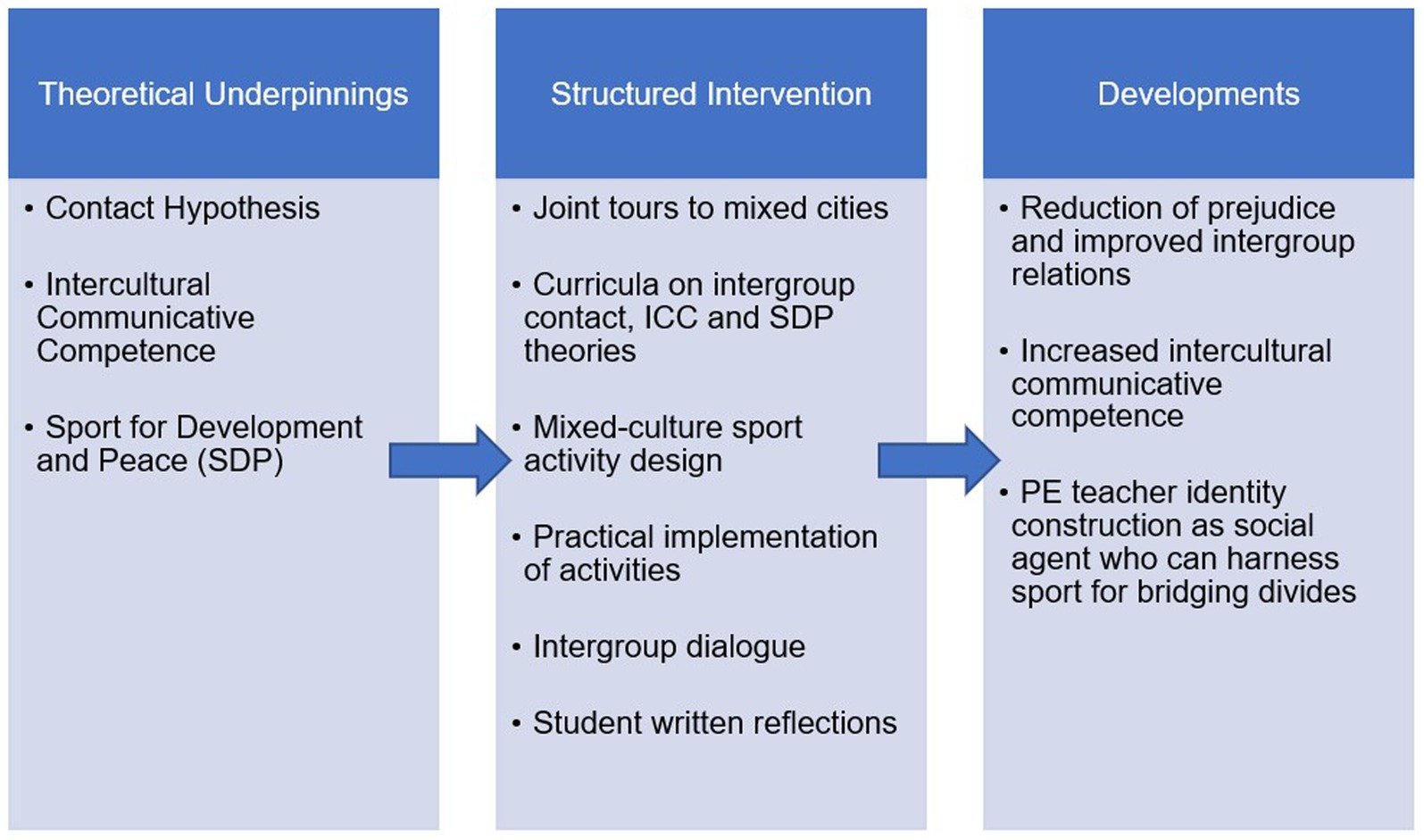

The study aimed to explore how intergroup contact influences the experiences and perceptions of PETE students from diverse backgrounds and facilitates their development of intercultural communicative competence (ICC). Thematic analysis of student reflections led to the construction of a pedagogical model for developing intergroup relations and ICC through sport in PETE (see Figure 1). This model conceptualizes a process in which structured intergroup contact, facilitated through sport and enriched by dialogue and reflection, leads to improved intergroup relations, reduced prejudice, the development of ICC, and the formation of a professional identity aligned with SDP principles. Each component of the process is discussed below.

Figure 1. A pedagogical model for developing intergroup relations and ICC through sport in PETE education.

Intergroup contact

The program met all four conditions of the Contact Hypothesis. Although Arab and Jewish student numbers were unequal, internal ethnic and religious diversity prevented dominance of any one group, and all students shared equal status as PETE undergraduates, supported by instructors from both groups. Students collaborated on assignments toward a shared goal of successfully completing the course within an academic setting that offered institutional support.

Student reflections showed attitudinal change, with final journal entries indicating reduced prejudice and improved intergroup relations. These findings align with previous research on the Contact Hypothesis, particularly in academic contexts involving collaborative projects (Bernstein and Salipante, 2017; Cheng and Zhao, 2007; Hendrickson, 2018; Hu and Kuh, 2003; Lin and Shen, 2020; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006). Paluck et al.’s (2019) meta-analysis of 27 interventions found that only 13 involved college students, all but one in the U.S., with just three addressing religious intergroup contact, and only one involving Arabs and Jews. Most interventions were short-term and failed to meet all four Contact Hypothesis conditions, relying mainly on cross-sectional quantitative methods. Only one study analyzed diary entries (Page-Gould et al., 2008).

Unlike most prior studies, this long-term intervention with Arab and Jewish college students in Israel fulfilled all four Contact Hypothesis conditions. The qualitative data reinforce the model, showing how fear—often rooted in perceived hostility, lack of knowledge and media disinformation—sustains prejudice. Prolonged cooperation toward a shared goal within a structured setting fostered meaningful change.

Students described a shift from fear to connection and desired living in partnership, driven by several mechanisms. Students described a process of cognitive dissonance and an affective impact, leading to stereotype disconfirmation. Over 12 weeks, repeated dissonance between media-based expectations and real interactions led to a reflective process, especially among Jewish students. This finding contrasts with critiques of the Contact Hypothesis that suggest it primarily serves to reduce prejudice among historically disadvantaged groups toward majority populations (McKeown and Dixon, 2017). Arab students came to see that both groups shared a desire for equality and partnership (Dovidio and Gaertner, 1999). Both groups reported initially holding false beliefs that students from the other group harbored negative perceptions of them, which contributed to feelings of apprehension. Upon recognizing that these fears were unsubstantiated, participants expressed greater openness to establishing interpersonal connections. These findings also stand in contrast to critiques that intergroup contact can diminish differences by promoting superficial harmony and suppressing group identities (McKeown and Dixon, 2017). On the contrary, students’ reflections reveal a process of learning about, becoming more familiar with, and developing a deeper understanding of their peers’ diverse identities and cultural backgrounds. Rather than erasing difference, this process allowed students to engage more openly with it, fostering meaningful dialogue and cooperation in the search for constructive ways to address conflict.

Students emphasized that change occurred due to the course’s structured framework and joint activities. Theoretical tools such as active listening, perspective-taking, and suspending disbelief enabled dialogue and challenged biases. Ongoing written reflections helped students critically examine and reassess their initial prejudices in a safe environment for dialogue.

One of the main criticisms of intergroup contact interventions is that they often create an idealized “bubble” removed from the complexities of real social dynamics (Dixon et al., 2005; McKeown and Dixon, 2017). In contrast, this program reflected the realities of Israeli society, with its diverse Jewish majority and diverse Arab minority, thereby presenting a more authentic intergroup context. Importantly, the intervention moved students beyond the “laboratory” conditions of the classroom and into mixed cities, where they engaged directly with representatives of communities in conflict. Through meetings with proactive social leaders striving for change, whether through sport or other initiatives, students were exposed to lived experiences of inequality and cooperation. These encounters, combined with the sports activities that students designed and implemented collaboratively in these communities, fostered a sense of responsibility and motivation to become active agents of change, rather than remaining “sedated” into accepting the status quo as critics of the Contact Hypothesis have warned (McKeown and Dixon, 2017). The subsequent guided classroom discussions, which encouraged reflection and processing of these experiences within a supportive academic environment, helped to reduce fears and further highlighted the potential of HEIs to lead such transformative processes (Paolini et al., 2018).

Most literature on the Contact Hypothesis relies on quantitative self-report data. Responding to calls for deeper insight into participant experiences, this study analyzed students’ written reflections. These not only illustrated the students’ experiences but also played an active role in the developmental process. Writing about their perceptions and reflecting on their experiences helped students recognize and confront their fears, biases, and emotions, making reflection an integral part of the transformation.

Development of ICC

Consistent with existing literature, this study supports the vital role of HEIs in developing ICC (Gregersen-Hermans, 2017; López-Rocha, 2021). However, it shows that while HEIs offer potential for ICC development, opportunities often go unrealized due to ingroup preferences, as seen in other Israeli academic contexts (Abbas et al., 2018; Sky and Arnon, 2017). Findings reveal that students expressed interest but were generally unwilling to engage in intercultural encounters without a structured framework integrating theoretical content and practical activities. While in many cases they showed an open attitude and curiosity, the lack of knowledge about other cultures and their own hindered the development of skills of discovery and interaction and skills of interpreting and relating, preventing critical cultural awareness. While the model proposes interaction among the five dimensions, this study suggests the first two—attitudes and knowledge—are foundational.

Raising students’ awareness of ICC developmental processes and designing collaborative mixed-group activities facilitated the development of curiosity about other cultures, leading them to improve their skills of discovery and interaction with outgroup peers. This process led to meaningful interactions between the students which facilitated the development of skills of interaction with students of other cultures as well as their own, with students reflecting on the process of enhanced self-identity. This development led to critical cultural awareness that enabled students to better understand their own culture in comparison to other cultures with which they engaged, in fact strengthening their cultural values as they learned about and better understood the values of their peers of other cultures.

The Multi-Dimensional Model of ICC (Byram, 1997), developed in foreign language education, asserts that effective communication in a foreign language requires intercultural competence alongside linguistic competence (Hoff, 2014). For this reason, the model has influenced curricula, teaching, and assessment across diverse language learning contexts (Galante, 2015; Liu, 2021), particularly in study abroad programs (Boye, 2016; Luo, 2021) and online collaborations (e.g., O’Dowd and Dooly, 2020). A systematic review of 54 virtual exchange programs found that Byram’s model was the most commonly used ICC framework, showing positive outcomes (Lewis and O’Dowd, 2016).

Harper (2023) argues that despite extensive research, ICC remains underrepresented in higher education curricula and advocates for its inclusion, particularly by language educators. This study demonstrates that ICC can also be taught effectively in courses on cultural diversity and identity, prompting meta-cognitive reflection on the development of intercultural competence. Unlike studies focusing on international students learning language, this research examined ICC among intra-national students—Arab and Jewish PETE students—interacting face-to-face in a higher education setting. Dervin (2016) and Hoff (2020) critique the model’s homogenic view of culture, failing to take into account intra-national cultural diversity. Hoff also emphasizes that identity is dynamic and multi-dimensional, and should not be essentialized only to nation or culture. The current study supports this view by showing how collaboration in an academic setting deepened students’ understanding of identity as dynamic and multifaceted. Exposure to diverse backgrounds allowed students to move beyond an Arab-Jewish binary, recognizing Israeli identity as a complex mosaic of cultures, religions, and ethnicities. This shift led students to view peers as individuals rather than cultural stereotypes, a transformation essential for inclusive education. The course fostered this understanding by encouraging dialogue and self-reflection, promoting a nuanced view of cultural complexity. Thus, the study affirms the model’s relevance in culturally diverse intra-national HEI contexts.

Simultaneously, students explored their emerging professional identities as PE teachers. Despite the cultural diversity revealed, a shared identity as inclusive educators, capable of uniting diverse students through sport, emerged.

Sport for development and peace: developing an activist PE teacher identity

The Roaming Course significantly shaped students’ perceptions of their roles as novice PE teachers, underscoring sport’s transformative potential to bridge cultural divides. Through structured interactions and reflective practice, students came to see sport as a means of fostering inclusion, empathy, and social change, in line with SDP principles.

Reflections revealed a growing awareness of sport’s capacity to transcend linguistic and cultural barriers. Designing and implementing activities in mixed groups with children highlighted how sport facilitates non-verbal communication and shared experiences, key to building trust and understanding. This was especially evident among non-Arab-speaking Jewish students, who successfully bonded with non-Hebrew-speaking Arab children, illustrating SDP’s emphasis on using sport to promote cooperation, respect, and social responsibility.

The SDP framework posits that sport creates neutral ground for social cohesion, enabling engagement beyond cultural identifiers (Kidd, 2008; Sugden and Tomlinson, 2017; Svensson and Woods, 2017). Students experienced firsthand how collaborative sports activities fostered connections often hindered in more formal or culturally charged settings.

As students advanced through the course, their successful teaching experiences deepened their understanding of intercultural dynamics and reshaped their professional identities. They began to view teaching not only as a means of developing physical skills, but also as a platform for social activism. The course helped shift their perspective from seeing PE as a technical subject to embracing their roles as activist educators, committed to collaboration, inclusion, and the transformative power of sport.

While most studies exploring PE and ICC focus on school-aged children (Grimminger-Seidensticker and Möhwald, 2020; Puente-Maxera et al., 2020), research on PETE students remains limited. Anttila et al. (2018) reported that a 3-day online workshop raised Finnish PETE students’ awareness of diversity and equality, though the experience was theoretical and not embedded in practical, diverse contexts. Ko et al. (2013) observed enhanced ICC in American and Korean graduate students after a 7-week online PE course. By contrast, the present study involved culturally diverse intra-national students in a three-month, face-to-face, practical program. Working in mixed groups and teaching children from varied backgrounds grounded ICC development in real-world experience, providing empirical support for embedding intercultural education in PETE curricula.

Shapira and Fisher-Shalem (2024), studying 68 Arab and Jewish teachers in a Shared Education program, found that despite challenges, teachers believed in their role in promoting peace and shared living. They stressed the need to educate older students to value multiple perspectives. The current study reinforces this view, highlighting the pivotal role of young adults, particularly future teachers, in shaping a more inclusive society. When integrated with sport and physical education, this potential is amplified: these disciplines provide powerful tools for cultivating collaboration, mutual understanding, and social cohesion.

In conclusion, the Roaming Course illustrates sport’s capacity to shape activist teacher identities and foster intercultural understanding. By embedding SDP principles in PETE, the course contributes meaningfully to peacebuilding efforts in divided societies.

The social model as dynamic theory

“The power of example is a tried and tested way for ideas to break through to policymakers and the public. When people see something working that appears to solve a problem or meet a need, it cuts through faster than any published research. Social scientists can learn from this by identifying and developing demonstration models that show social problems being solved in reality” Alexander (2025, p. 3).

The pedagogical model developed through the Roaming Course represents such a demonstration model—a “real-time social model” grounded in lived experience and designed to address a pressing societal issue: the persistent self-segregation of social groups and the underdevelopment of ICC in Israeli society.

The social models as dynamic theory offers a compelling framework for reconceptualizing higher education as responsive, iterative, and embedded in real-world sociocultural contexts. Rather than remaining a detached, theoretical exercise, the Roaming Course serves as a live model of such an approach. It evolves through engagement with students and diverse communities, adapting to contextual realities, and generating feedback that informs ongoing development. Its integration of intercultural dialogue, experiential learning, and reflective practice into PETE curricula illustrates how dynamic theory can be structurally embedded into teacher education.

Situated at the “Mini” level of Alexander’s (2025) Levels of Social Models Scale—as an “organizational unit”—the course provides evidence of transformative change within the localized setting of a teacher education program. Yet, its implications and aspirations extend beyond.

Following the pilot’s success, the model is currently being expanded to the “Midi” level, targeting the broader institutional “entity.” Over the next three years, the course will be scaled up as part of a college-wide initiative. Two additional courses based on the model will be offered in the upcoming academic year, followed by two more each year, culminating in six courses by the third year. This expansion is supported by the Israeli Council for Higher Education (CHE) through the national Academic 360 initiative, which seeks “to promote deep changes in academic curricula in higher education institutions in order to maintain the relevance and impact of academic education on its surrounding environment—both for the individual and for society” (Council for Higher Education in Israel, 2024).

The model will be adapted with student teachers in the fields of music education and art education. In this sense, the course exemplifies a dynamic theory in action, continuously evolving through interaction with diverse student populations and real-world community partners. This adaptability supports Alexander’s (2025) argument that dynamic social models must go beyond static curricula and abstract theory to become attuned to and embedded within changing social realities.

Moreover, this longitudinal implementation creates an infrastructure for comparative research with parallel initiatives at other higher education institutions in Israel, with the goal of collaboratively generating real-time data and experiential knowledge. Through this integrative process, the model may evolve toward the “Macro” level—impacting policy and shaping public discourse on intercultural education and social cohesion at the national level.

An intervention at one level of the system often produces ripple effects across others. Just as a well-designed course may reshape institutional practice and yield broader economic or social outcomes, the Roaming Course holds the potential to influence future educators’ professional identities and civic responsibilities, thereby contributing to systemic educational and societal change. As such, the model affirms the hypothesis that “the most valuable advances in social science are likely to come from work on real-time social models (“dynamic theories”) which improve the human condition” (p. 13).

Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the development of intergroup relations and ICC among PETE students through a structured sport-based intervention, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although the three-month duration of the course represents a longer intervention than many previous studies on intergroup contact and ICC, it remains relatively short in terms of tracking long-term developmental outcomes. A longitudinal design spanning the full duration of students’ academic studies could yield richer data on the sustainability of attitudinal and behavioral change over time.

Second, the qualitative nature of the study, while enabling an in-depth exploration of students’ experiences and reflections, necessarily limits generalizability. The findings are context-specific, reflecting the unique social and political dynamics of Arab–Jewish relations in Israel. The course was implemented in 2021–2022, shortly after the May 2021 Arab–Jewish riots (Barnea, 2024) and prior to the 2023 Swords of Iron War. This was a period marked by heightened volatility, recurring acts of violence, and deep mistrust between the groups. Recent studies suggest that intergroup anxieties and levels of distrust were actually higher in this pre-war period than after October 7, 2023, when the massacre and ensuing war led to a greater sense of shared vulnerability and tragic loss across both Arab and Jewish communities. Surveys indicate that the war generated, at least temporarily, a stronger sense of shared destiny under a common threat, though this occurred alongside persistent tensions rooted less in the war itself than in longstanding civic and structural inequalities (Hazran, 2024; Lavie et al., 2023).

Against this backdrop, the significance of the present small-scale qualitative study lies in its ability to capture nuanced student voices during a particularly fragile moment in Arab–Jewish relations. As was shown, during the intervention we as facilitators were also required to navigate a number of challenges and dilemmas regarding how best to proceed, underscoring the complex and dynamic nature of conducting such work in real-world contexts. While not statistically generalizable, studies of this kind provide crucial insights into the processes through which structured interventions can foster intercultural learning, empathy, and cooperation in highly divided societies. By documenting how these dynamics unfolded in a concrete setting, the study offers a transferable pedagogical model that may inform similar interventions in other conflict-affected or deeply divided contexts, both within and beyond Israel. The approach and underlying principles may thus hold relevance across diverse settings and could be adapted to address intergroup tensions in other societies, as well as incorporated into teacher education programs aiming to foster intercultural competence and social cohesion. While the model developed here is particularly applicable within the discipline of PETE, it may also be adapted to suit other teacher training contexts seeking to promote inclusive and interculturally responsive education. Looking ahead, larger-scale empirical studies are recommended to further examine the robustness of this model, test its applicability across different contexts, and assess the sustainability of its long-term outcomes.

Third, although students submitted multiple reflections throughout the course, data collection relied exclusively on self-reported narratives. While these reflections were rich in personal insights and revealed important transformations, they may have been influenced by social desirability or by students’ awareness of being part of a structured program. Future studies could therefore incorporate complementary methods—such as interviews, focus groups, or observational data—to provide a more comprehensive and triangulated understanding of the processes involved. At the same time, it is important to note that reflective journals are particularly well-suited for capturing participants’ subjective voices over time, aligning with the qualitative aim of this study to foreground how students themselves perceived and made sense of their experiences. The iterative nature of journaling, combined with guided prompts after each course encounter, also provided a form of “process data” that allowed developmental shifts to be tracked across the semester, which would be more difficult to achieve through single-point interviews alone.

Overall, these limitations highlight the need for cautious interpretation of the findings while also underscoring the value of this study as a pilot that offers both a transferable pedagogical model and a foundation for future, larger-scale and longitudinal research.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the potential of a structured, sport-based academic course to foster intergroup relations and develop ICC among Arab and Jewish PETE students in a higher education context. Drawing on the Contact Hypothesis, the Multi-Dimensional Model of ICC, and the SDP framework, the intervention created a supportive environment where students engaged in meaningful dialogue, reflection, and collaborative practice. The findings highlight how structured intergroup contact, guided by theoretical and pedagogical frameworks, can reduce prejudice, build mutual understanding, and shape socially active PE professional identities. As such, the study underscores the vital role of higher education in preparing future educators to lead in diverse, divided societies, and points to the transformative power of sport in advancing this mission.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Levinsky-Wingate Academic College. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation. MS: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We wish to thank the Edmond de Rothschild Foundation for funding the Roaming Course program. We also wish to thank the Levinsky-Wingate Academic College President’s Fund for supporting the research and its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used for language editing purposes.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1626285/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbas, F., Greenberg-Ra’anan, M., and Maayan, Y. (2018). Sense of belonging to the academic institution among Arab students survey. Inter-Agency Task Force. Available online at: https://www.iataskforce.org/resources/view/1660 (Accessed May 10, 2025).

Alexander, T. (2025). Social models as dynamic theories: how to improve the impact of social and political sciences. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1443388. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1443388/full

Anttila, E., Siljamäki, M., and Rowe, N. (2018). Teachers as frontline agents of integration: Finnish physical education students’ reflections on intercultural encounters. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 23, 609–622. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2018.1485141

Aslih, S., Eldar, L., Hasson, Y., and Halperin, A. (2020) Maximizing the potential of the Jewish-Arab encounter in academia. aChord center, Abraham initiatives research report

Auschner, E. (2019). “Fostering intercultural competence in higher education: designing intercultural group work for the classroom” in Examining social change and social responsibility in higher education. ed. S. L. Niblett Johnson (Hershey, PA: IGI Global Scientific Publishing), 116–126.

Barlow, F. K., Hornsey, M. J., Thai, M., Sengupta, N. K., and Sibley, C. G. (2013). The wallpaper effect: the contact hypothesis fails for minority group members who live in areas with a high proportion of majority group members. PLoS One 8:e82228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082228

Barnea, A. (2024). Missed signals that led to a strategic surprise: Israeli Arab riots in 2021. INSS. Available online at: https://www.inss.org.il/strategic_assessment/israeli-arab-riots/ (Accessed June 26, 2025).

Bennett, R. J., Volet, S. E., and Fozdar, F. E. (2013). “I’d say it’s kind of unique in a way”: the development of an intercultural student relationship. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 17, 533–553. doi: 10.1177/1028315312474937

Bernstein, R. S., and Salipante, P. (2017). Intercultural comfort through social practices: exploring conditions for cultural learning. Front. Educ. 2, 31–45. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00031

Blaylock, D., and Briggs, N. (2023). “Intergroup contact” in Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology. ed. O. Braddick (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Boye, S. C. (2016). Intercultural communicative competence and short stays abroad: perceptions of development. Münster: Waxmann Verlag.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon: Multicultural Matters.

Çetinavci, U. R. (2011). Intercultural communicative competence in English (foreign) language teaching and learning. Mediterr. J. Humanit. 2, 59–71. doi: 10.13114/mjh/20111789

Cheng, D. X., and Zhao, C. M. (2007). Cultivating multicultural competence through active participation: extracurricular activities and multicultural learning. NASPA J. 43, 1209–1234. doi: 10.2202/1949-6605.1721

Coalter, F. (2009). “Sport-in-development: accountability or development” in Sport and international development. Global culture and sport. eds. R. Levermore and A. Beacom (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 55–75.

Coperías-Aguilar, M. J. (2009). Intercultural communicative competence in the context of the European higher education area. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 9, 242–255. doi: 10.1080/14708470902785642

Coşkun, D. (2022). “Assessment of intercultural communicative competence in higher education contexts: a systematic review” in Essentials of foreign language teacher education. eds. A. Önal and K. Büyükkarci (Konya: ISRES), 110–133.

Council for Higher Education in Israel (2024) The CHE program to promote deep curricular reform in undergraduate study programs: “Academia 360.” (Heb). Available online at: https://che.org.il (Accessed August 27, 2025).

Cousin, G. (2005). Case study research. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 29, 421–427. doi: 10.1080/03098260500290967

Darnell, S. C., Chawansky, M., Marchesseault, D., Holmes, M., and Hayhurst, L. (2018). The state of play: critical sociological insights into recent ‘sport for development and peace’ research. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 53, 133–151. doi: 10.1177/1012690216646762

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 10, 241–266. doi: 10.1177/1028315306287002

Deardorff, D. K., and Arasaratnam, L. A. (2017). Intercultural competence in higher education: International approaches, assessment and application. London: Routledge.

Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education: a theoretical and methodological toolbox. London: Springer.

Dixon, J., Durrheim, K., and Tredoux, C. (2005). Beyond the optimal contact strategy: a reality check for the contact hypothesis. Am. Psychol. 60, 697–711. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.697

Dovidio, J. F., and Gaertner, S. L. (1999). Reducing prejudice: combating intergroup biases. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 8, 101–104.

Dunne, C. (2009). Host students’ perspectives of intercultural contact in an Irish university. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 13, 222–239. doi: 10.1177/1028315308329787