- 1Department of Political Science, Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia

- 2Polsight Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

- 3Department of Politics and Government Science, Diponegoro University, Semarang, Indonesia

- 4Faculty of Communication and Media Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Shah Alam, Malaysia

Generally, illegal activities are taboo to discuss, let alone perform. But does vote-buying carry the same stigma, or is it instead normalized as part of election tradition? This research investigates how the public perceives vote-buying practices and its impact on democracy, using a case study of West Bandung Regency, Indonesia. A quantitative survey was conducted on 1,200 respondents from November 10th to 14th, 2024, approximately 2 weeks before the 2024 Regional Elections (Pilkada). The findings reveal that vote-buying, despite its illegality, is not heavily stigmatized in the public eye. Nearly half of the respondents rationalized the practice in elections, and almost all of these respondents expressed willingness to accept money from candidates. Interestingly, a majority of those willing to accept money still stated they would vote according to their conscience—not the will of the vote “buyer”—in the secrecy of the polling booth. Furthermore, respondents tended to be responsive to the amount of money offered: the larger the sum, the more likely they were to comply with the payer's wishes—vice versa. These findings make a significant theoretical contribution by demonstrating that vote-buying, while widely considered wrong both legally and morally, nonetheless enjoys a high level of social acceptance. However, they contrast with traditional reciprocity theory, which assumes vote-buying functions like a transaction for goods/services; here, money does not always translate directly into votes, as voters still wish to vote according to their conscience. Practically, this research urges policymakers to address vote-buying systemically. It also criticizes previous solutions proven ineffective and suggests potential best solutions.

Introduction

Elections are ideally contests between political parties and charismatic candidates with grand visions. However, closer observation across global contexts reveals that electoral processes are often driven by pragmatic transactions exchanging material benefits for political support—a phenomenon termed “clientelism.” One of the most prevalent forms of clientelism is vote buying, a practice where candidates—either directly or through intermediaries—provide cash or other material rewards to voters to secure electoral support (Schaffer and Schedler, 2007). This practice manifests the opposite of democratic accountability: rather than citizens exercising sovereign oversight over politicians, vote-buying subordinates voters to political control, undermining their capacity to freely exercise political rights (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., 2014). Nearly all democratic countries explicitly prohibit vote buying in their electoral regulations, but on-the-ground facts show this illegal practice remains rampant, particularly in developing countries with unconsolidated democracies (Lewis and Dong, 2025; Murugesan and Tyran, 2023). This does not mean historically democratic countries are immune to vote buying, only that the practice is more pervasive and more decisive in countries undergoing democratic transitions (Schaffer, 2007c; Vicente, 2014).

Indonesia, the world's fourth-largest population and third-largest democracy, ranks among the countries with the highest vulnerability to vote buying. Following the collapse of Suharto's 30-year authoritarian regime in 1998, Indonesia's democratization from the outset has been marked by rampant exchanges of patronage for political support (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019). In the 2014 legislative elections, Muhtadi (2019a) estimated that the proportion of voters involved in vote buying ranged between 25% and 33%, making Indonesia the world's third-largest country in terms of vote buying prevalence. No significant change occurred after a decade. A 2024 Presidential Election exit poll survey by Indikator showed nearly half of voters considered vote-buying reasonable, with only about 8% of this tolerant group firmly refusing money from any candidate (Indikator, 2024). Meanwhile, a national Populix survey ahead of the 2024 Regional Elections found that most respondents had been offered money multiple times (31%) or at least once (19%) in previous elections (Populix, 2024). It is hardly surprising that political costs in Indonesia are exceptionally high. A Westminster Foundation for Democracy Limited study reported that legislative candidates in the 2024 elections spent an average of 5 billion rupiah (US$315,000) (Prihatini and Wardani, 2024). An ordinary Indonesian citizen with a median income of 36 million rupiah would need to work for 140 years without spending any money to finance such a political campaign.

Electoral dynamics at the local level could prove even more severe (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Aspinall and Sukmajati, 2018; Lewis and Dong, 2025). Noor et al. (2021, p. 241) contend that “the direct local election has great potential to be the major cause of money politics in Indonesia.” In several regions of Riau, for example, Saputra and Setiawan (2023) documented nearly 70% of respondents admitted to being targets of vote-buying. If this calculation is accurate, then vote-buying rates in Riau far exceed national rates. Similar patterns emerged in Subang Regency, where Komarudin et al. (2025) estimated vote-buying influenced nearly 70% of voting behavior. They identified this aggressive strategy as the decisive factor in unseating an incumbent with objectively strong performance. Two structural factors may explain local elections' heightened vulnerability. First, unlike national elections with vast coverage, political interaction patterns in local elections between regional heads and communities tend to be more personal (Driscoll, 2018). Second, local communities typically maintain high socioeconomic dependence on political elites, making patron-client relationships easier to form (Noak, 2024).

Nevertheless, given that decentralization and regional autonomy are relatively new in Indonesia, the phenomenon of vote-buying in local elections remains underexplored compared to national elections. Existing research has also yielded unsatisfactory results, as most studies rely on mass surveys that directly interrogate respondents about their involvement in vote-buying. Admittedly, this approach is highly practical and logical; if we want to know whether voters engaged in vote-buying, simply ask them directly. However, this pragmatic method fundamentally overlooks vote-buying's stigmatized nature. Beyond being legally illegal and morally wrong, voters may hesitate to admit selling their votes due to implications that they are impoverished enough to do so (Hatz et al., 2024). This negative stigma risks triggering social desirability bias, respondents' desire to project a positive image to interviewers, which depresses survey results below actual levels (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., 2012). As demonstrated by Blair et al. (2020) in their meta-analysis of 19 survey studies, direct measurement of vote-buying tends to be underreported by an average of 8 percentage points. When respondents answer dishonestly, survey data produce flawed aggregate estimates of public attitudes and behaviors, ultimately distorting causal analyses of sensitive topics like vote-buying.

Public perception surveys offer an alternative for mitigating social desirability bias in capturing empirical evidence of vote-buying. Rather than directly interrogating respondents, these surveys measure respondents' observations of vote-buying practices in their communities, their perceptions of the practice's acceptability, and their attitudes toward accepting such offers. By emphasizing hypothetical scenarios, respondents feel less intimidated and thus become more willing to honestly disclose how commonplace vote-buying is. Beyond reducing underreporting, perception surveys can also reveal behavioral nuances difficult to capture through direct questioning—such as whether voters feel indebted to vote “buyers” or have specific monetary thresholds for their votes. These insights support more accurate prevalence analyses and, crucially, generate actionable reform insights (Blair and Imai, 2012; Gallego and Wantchekon, 2012; Gans-Morse and Nichter, 2021). Understanding why voters justify vote-buying—whether due to poverty, distrust of candidates, or normalized corruption—enables policymakers to tailor interventions.

Therefore, this article examines public perceptions of vote-buying and its democratic implications through a case study of West Bandung Regency, Indonesia. As part of West Java, one of the provinces with the highest Election Vulnerability Index (Indeks Kerawanan Pemilu) in Indonesia (Bawaslu, 2023), West Bandung Regency receives less scholarly attention than Bandung City and Bandung Regency. Yet West Bandung directly borders both regions and has one of West Java's highest electoral vulnerability rates (Alhamidi, 2024). There is very little insight into vote-buying practices in West Bandung Regency other than some anecdotal evidence that is not even properly documented (Gunawan, 2024). Consequently, selecting West Bandung Regency as a case study not only enriches vote-buying literature in local election contexts but also completes the puzzle of how grassroots communities perceive democracy through everyday politics. Our findings reveal complex, multidimensional public attitudes toward vote-buying, with three significant outcomes: (1) social acceptance of vote-buying is relatively high; (2) a subset of respondents who accept money still tend to vote according to conscience; (3) monetary amounts critically influence respondents' willingness to accept offers. Subsequently, we detail the research design and findings review, followed by an in-depth discussion of implications for democracy and potential solutions.

Methods

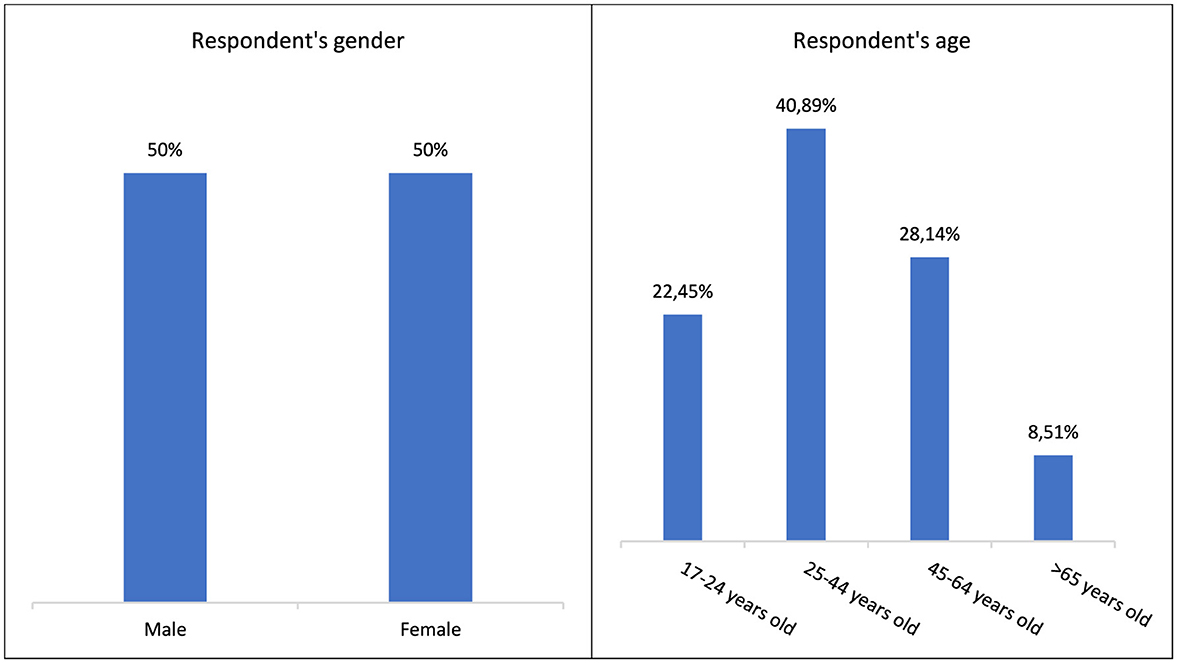

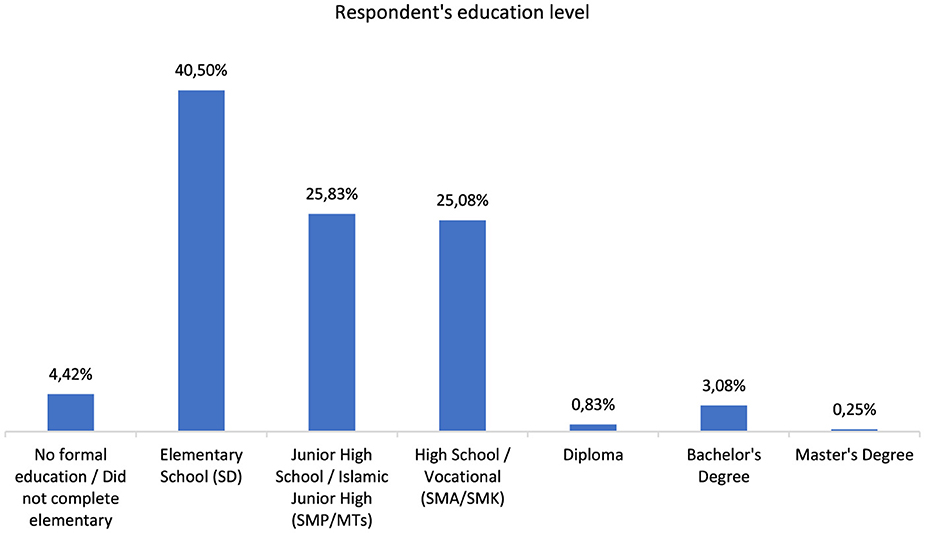

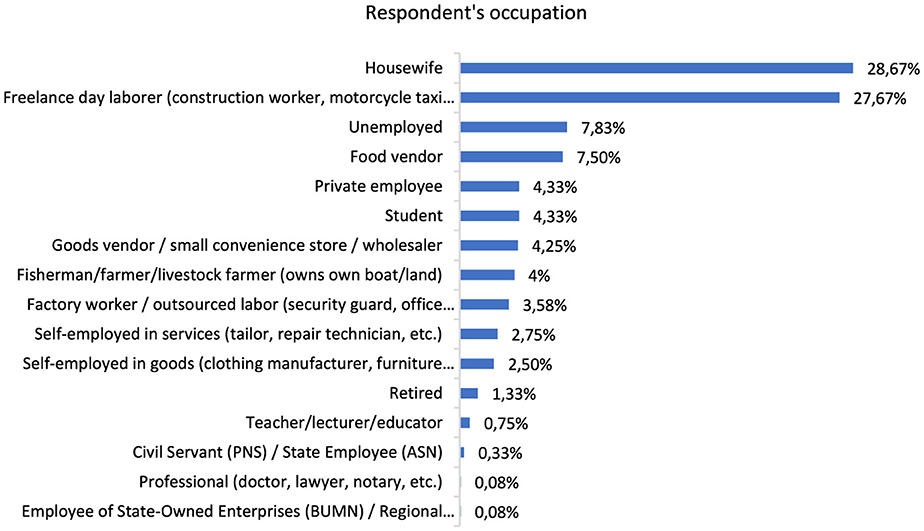

This study employed a quantitative survey methodology, sampling respondents from the 2024 Permanent Voter List (Daftar Pemilih Tetap, DPT) of West Bandung Regency, West Java, Indonesia. West Bandung Regency (Sundanese: Bandung Kulon), which was split off from Bandung Regency, has a population of 1.88 million and 1,309,568 registered voters in 2024. Using stratified-systematic random sampling, 1,200 respondents were selected proportionally across 16 subdistricts (kecamatan) and 165 villages (desa). Demographic representativeness was prioritized: gender distribution was perfectly balanced (50% male, 50% female), with multigenerational age coverage (17–24 years: 22.45%; 25–44 years: 40.89%; 45–64 years: 28.14%; ≥65 years: 8.51%) (Figure 1). A substantial proportion (40.50%) completed only elementary school, and another 25.83% finished junior high school. Those with high school or vocational diplomas comprised 25.08%, while higher education credentials were rare: merely 3.08% held bachelor's degrees, 0.83% held diplomas, and only 0.25% attained master's degrees (Figure 2). Notably, 4.42% had no formal schooling or incomplete elementary education. Occupations were heterogeneous: housewives constituted the largest cohort (28.67%), followed by diverse formal/informal workers (57.64%), unemployed individuals (7.83%), students (4.53%), and retirees (1.33%) (Figure 3).

Survey administration occurred during the critical pre-election window of November 10 to 14, 2024, about 2 weeks preceding the 2024 Regional Elections (Pilkada). To mitigate temporal bias and social desirability effects, questionnaire design deliberately avoided explicit references to the imminent election. Instead, questions probed generalized perceptions of electoral clientelism through abstracted scenarios. Our trained surveyors conducted face-to-face interviews using a standardized protocol emphasizing respondent anonymity and conversational neutrality. Surveyors were instructed to cultivate non-judgmental atmospheres to elicit candid responses, with explicit assurances that data would remain strictly confidential and used solely for academic purposes. The instrument deployed a sequential approach: initial modules collected socioeconomic covariates (gender, age, education, occupation, monthly expenditure); subsequent sections explored nuanced dimensions of vote-buying perceptions—including expected monetary thresholds, optimal transaction timing (pre-voting vs. election day), and self-reported behavioral influence. This measurement enabled frequency distribution analyses to quantify attitudinal prevalence while identifying dominant sociopolitical rationalizations. The survey achieved a ±2.86% margin of error at a 95% confidence level.

Descriptive statistical analysis served as the primary methodology for synthesizing both categorical and numerical data, employing frequency distributions, percentage tabulations, and visual summarization techniques—especially bar charts—to characterize central tendencies, dispersion patterns, and response modality. However, this analytical framework imposed significant epistemological limitations due to its exclusive reliance on descriptive statistics. Crucially, the absence of inferential testing precluded rigorous examination of variable interdependencies: we could not empirically verify how age cohorts differentially normalized clientelist practices, whether income thresholds moderated perceptions of transactional “reasonableness,” or how educational attainment mediated ethical judgments of vote-buying. Such constraints rendered our analysis fundamentally correlational rather than causal, as we lacked the statistical machinery to isolate whether observed patterns stemmed from lifecycle effects, economic pressures, or cultural socialization. Consequently, while the study successfully mapped attitudinal prevalence, it could not quantify effect sizes or establish predictive frameworks for voter susceptibility. Future research should therefore integrate multivariate methods—such as logistic regression to model acceptance probability or ANOVA for intergenerational comparisons—to test interaction effects between demographic predictors and perceptual outcomes. These advanced techniques would transcend descriptive mapping to deliver explanatory power regarding the structural drivers of electoral clientelism, transforming observed correlations into validated causal pathways.

Results

Public acceptance of vote-buying

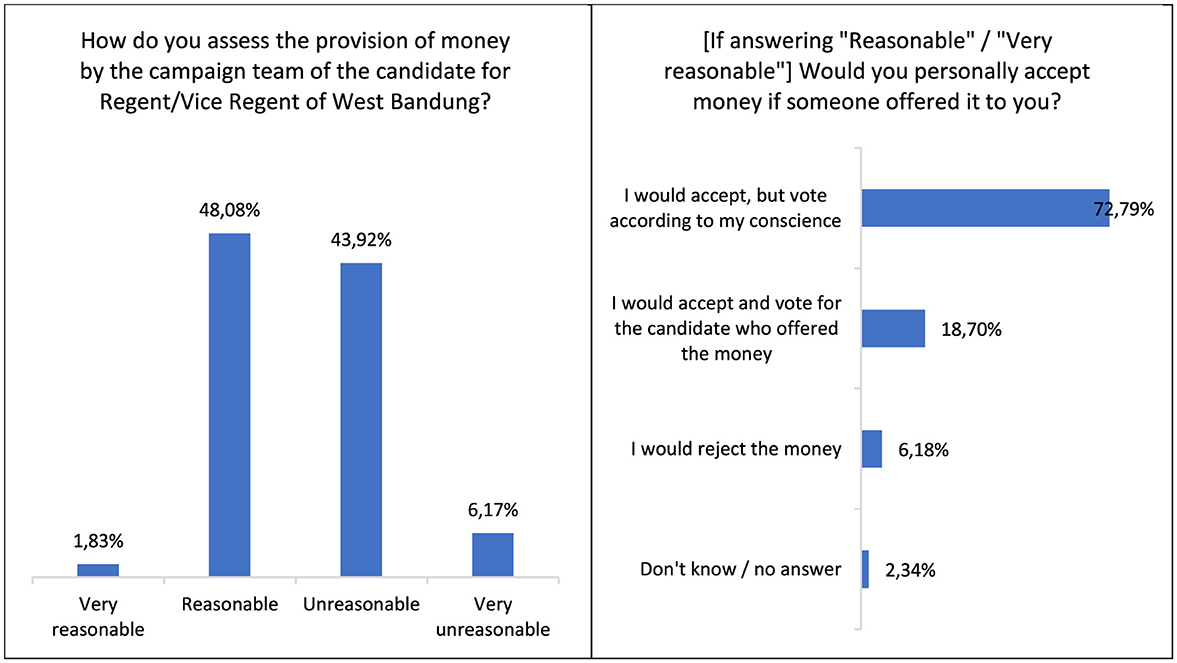

We examined whether vote buying was perceived as an acceptable practice. Our findings reveal that nearly half of all respondents (49.91%) perceived vote buying as commonplace in elections, with 1.83% responding “very reasonable” and 48.08% “reasonable.” Meanwhile, 50.09% viewed the practice as “unreasonable” (43.92%) or “very unreasonable” (6.17%). On one hand, despite the opposing proportion remaining larger, these results are surprising given vote buying's illegal nature. In other words, what has long been considered a stigmatized fraud appears increasingly normalized in practice. On the other hand, such high public acceptance is less surprising if vote-buying has indeed become pervasive in Indonesia—both nationally and locally (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Muhtadi, 2019b). Repeated direct exposure to this illicit practice desensitizes voters, thereby diminishing concern for abstract normative issues like illegality or democratic consequences (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., 2014). Familiarity cultivates permissive normative understandings that crucially sustain, reproduce, and rationalize such fraud among both perpetrators and victims.

Here, a distinction must be drawn between normalization and participation. Not all who normalize vote-buying are willing to engage in it. Nevertheless, regardless of their ballot choices, our data shows that nearly all respondents (91.49%) who rationalized vote-buying stated they would accept money from candidates. This result should not be interpreted simplistically as voter egoism. Voters possess varying capacities to observe, comprehend, and trust vote-buying's impacts. Some may participate solely for immediate gains—monetary compensation, strengthened social ties with vote brokers, or avoiding sanctions from political machines. Such motivations are predictable, even overly so. The greater complexity lies in understanding why they engage in illegal practices despite recognizing negative societal and democratic consequences. At the system level, most value democratic competition and rule of law while opposing corruption. Yet at the individual transaction level, people equally prioritize friendship, reciprocity, and promise-keeping alongside material benefits (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., 2014). This duality merits consideration when interpreting high vote-buying acceptance—a point we will deepen in the Discussion section.

Reciprocity and perceptions of timing

When voters receive money offered by candidates, they face two fundamental options: accept the money and vote for the vote “buyer,” or accept the money yet still vote according to their conscience. Traditional reciprocity frameworks in existing literature posit that accepting money, gifts, services, or assistance creates feelings of indebtedness and gratitude among voters, making them likely to support the benefactor in the voting booth (Finan and Schechter, 2012; Murugesan and Tyran, 2023). However, our survey reveals that only 18.70% of respondents followed this reciprocity logic (see Figure 4 above). Conversely, the majority (72.79%) stated they would accept money while maintaining their autonomous voting choice. The remaining respondents categorically rejected monetary offers (6.18%) or remained undecided (2.34%). In the context of voters, these findings suggest they do not automatically sacrifice personal integrity when engaging in monetary political transactions. For candidates, vote-buying constitutes a high-risk endeavor. When distributing money (or other material rewards) to voters, they cannot predict recipients' responses; they have no guarantee that beneficiaries will dutifully reciprocate in the secrecy of the polling booth.

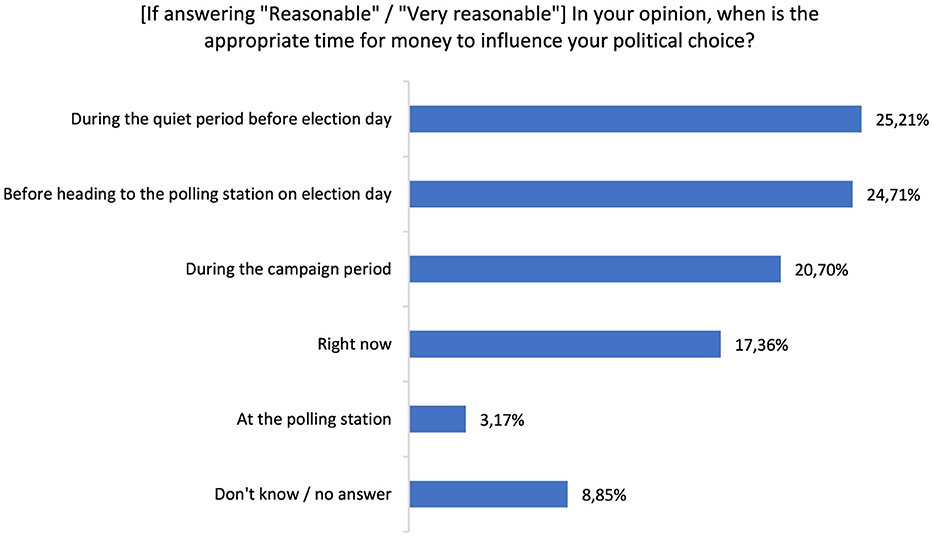

Additionally, we investigated the timing deemed most effective for vote “buyers” to influence vote “sellers.” A persistent assumption holds that candidates who distribute money latest are most memorable to voters in the booth. This explains why many candidates panic before elections, fearing competitors' intensified cash distribution requires matching tactics. Nevertheless, our data shows considerable variation (see Figure 5 above): 25.21% of respondents considered the pre-election quiet period optimal, while nearly as many (24.71%) preferred moments immediately before heading to polling stations—colloquially termed “serangan fajar.” Smaller but significant groups favored the campaign period (20.70%) or even earlier distributions (17.36%), with minimal respondents (3.17%) asserting money should be given at polling stations (TPS). This diversity indicates voters' acute sensitivity to payment timing, reflecting divergent perceptions of influence and urgency.

Responsiveness to the amount of money offered

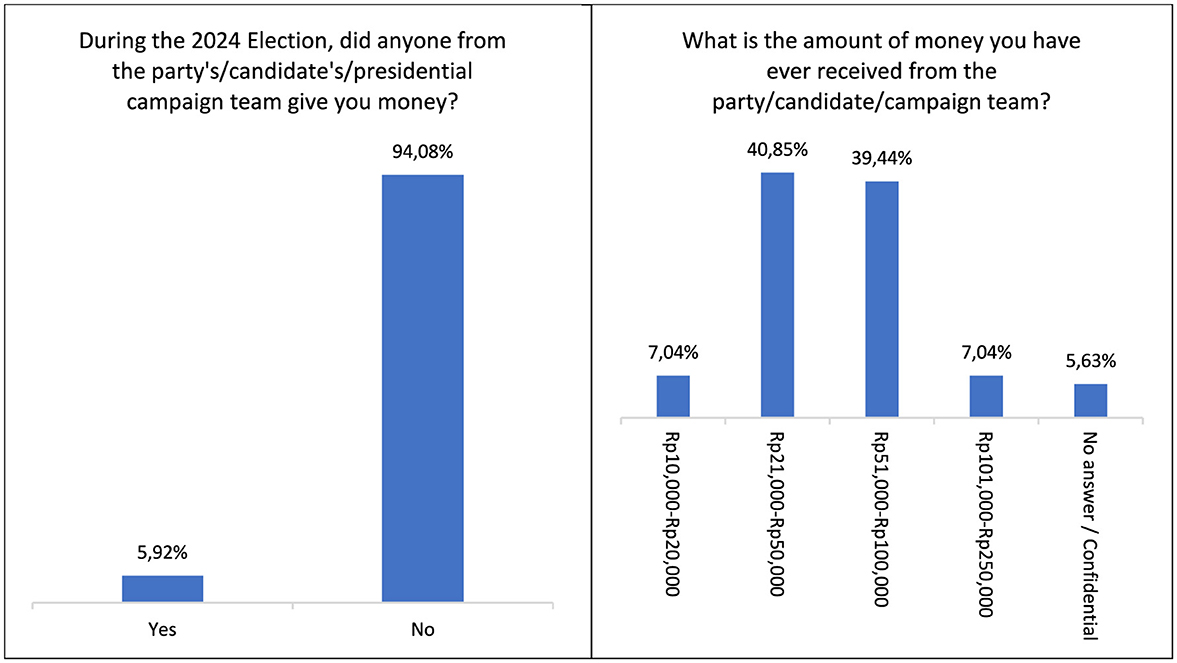

As anticipated, direct questions about respondents' involvement in vote-buying yielded low admission rates (5.92%) due to social desirability bias. We emphasize, however, that our intent was not to measure the prevalence of vote-buying in West Bandung Regency through such interrogative means. The core purpose of these questions was to establish actual monetary ranges received by voters for comparison with their expectations. Among those admitting receipt of money during the 2024 elections, most reported sums between Rp21,000–Rp50,000 (US$1,3–US$3,0) (40.85%), while 39.44% received Rp51,000–Rp100,000 (US$3,1–US$6,1) (Figure 6). Smaller segments reported lower (Rp10,000–Rp20,000 (US$0,6–US$1,2): 7.04%) or higher amounts (Rp101,000–Rp250,000 (US$6,2–US$15,2): 7.04%).

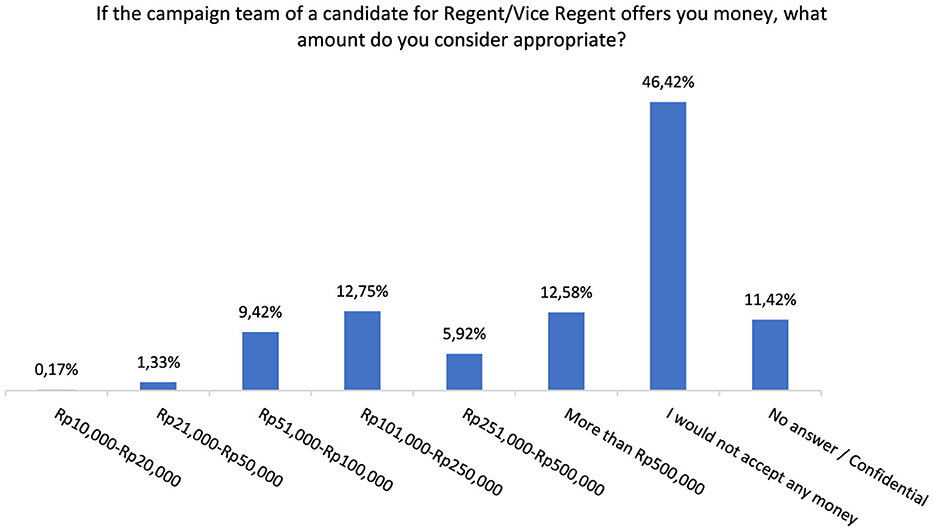

We then inquired about the amount they deemed appropriate to “buy” their vote. Is there a specific price threshold? Nearly half of our respondents (46.42%) outright rejected monetary offers. However, among those open to receiving money from candidates, the amounts considered appropriate varied considerably. Nearly equal proportions (12.75% vs. 12.58%) expected Rp101,000–Rp250,000 (US$6,2–US$15,2) and over Rp500,000 (more than US$30), respectively. Some voters appeared not only to expect large sums but also to consider their realism. Regardless, a notable pattern emerged: the two smallest monetary ranges received the lowest acceptance. Merely 0.17% respondents considered Rp10,000–Rp20,000 (US$0,6–US$1,2) appropriate, and 1.33% for Rp21,000–Rp50,000 (US$1,3–US$3,0) (Figure 7). This diversity of responses made it difficult to pinpoint a definitive ideal threshold. Nevertheless, a clear pattern emerged: nearly all voters expected higher sums than candidates typically provide. Moreover, smaller amounts were increasingly deemed inappropriate—and vice versa.

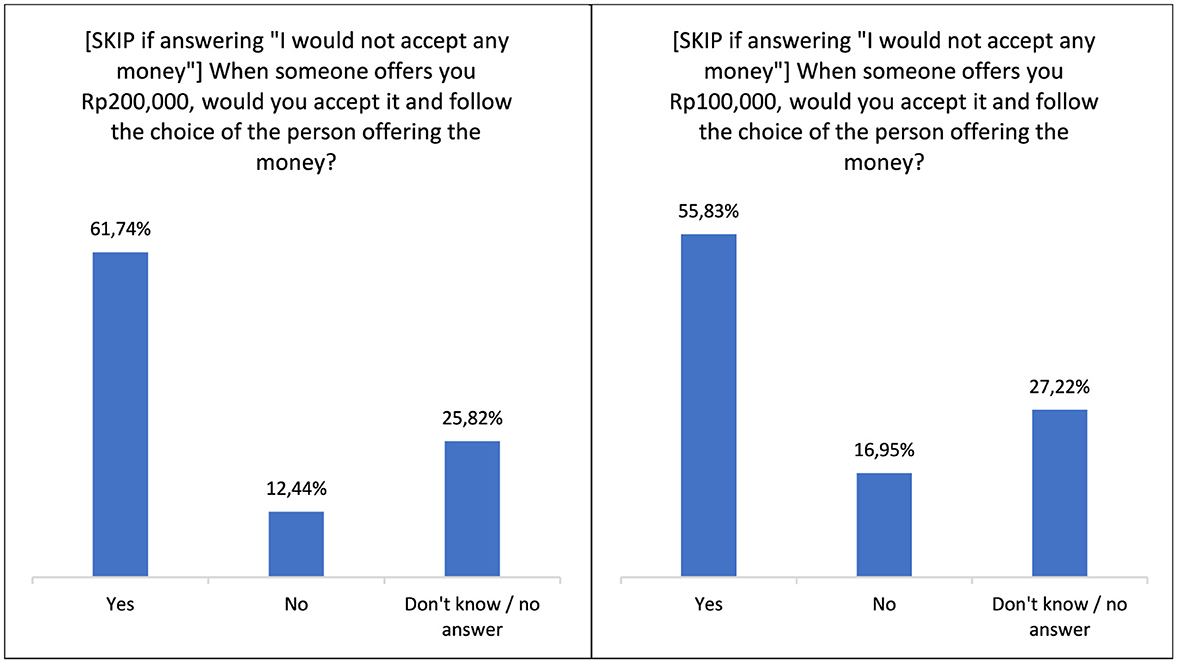

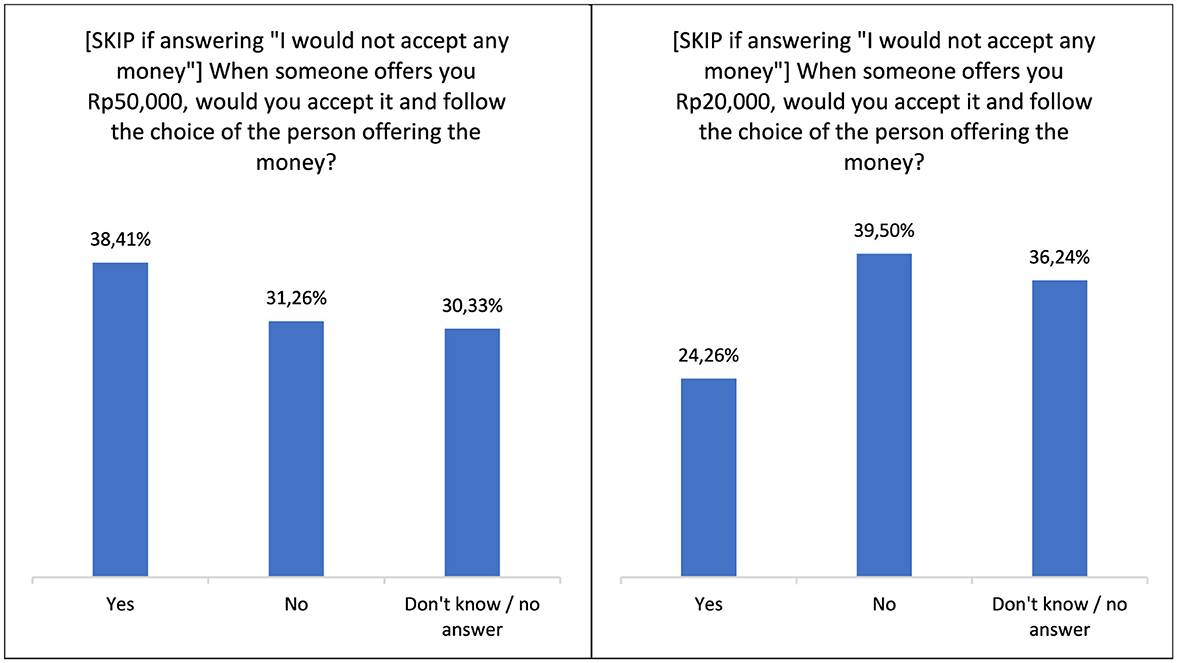

Further examination of the survey data confirmed this correlation. We analyzed the relationship between the amount offered and the likelihood of accepting money while voting for the payer. When presented with a hypothetical offer of Rp200,000 (US$12), 61.74% of respondents stated they would accept the money and follow the candidate's direction, compared to lower acceptance rates for smaller amounts. For Rp100,000 (US$6), acceptance was slightly lower at 55.83% (Figure 8), dropping further to 38.41% for Rp50,000 (US$3). An offer of Rp20,000 (US$1) saw even lower acceptance, with only 24.26% inclined to comply (Figure 9). This patterned response indicates voters are highly sensitive to financial incentives, with higher amounts progressively increasing compliance likelihood.

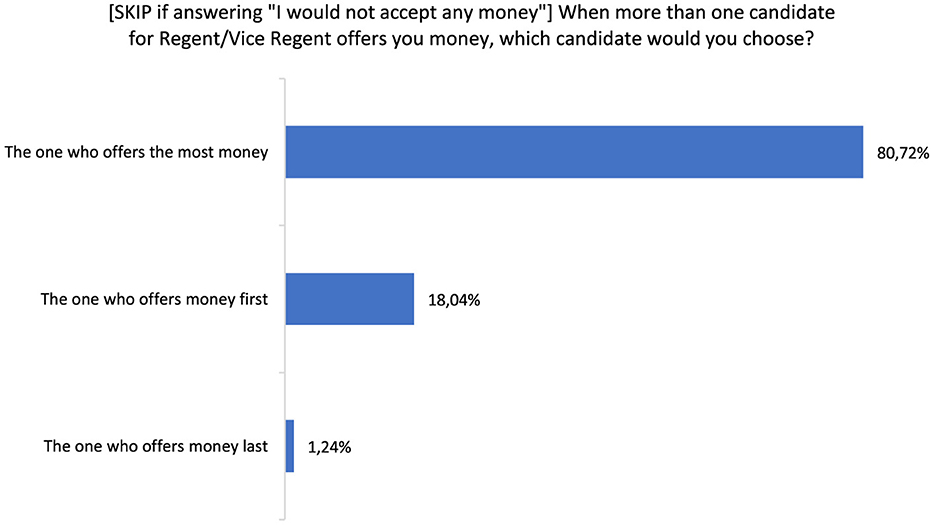

This tendency remained consistent in our final analysis of voter preferences when receiving money from multiple candidates. Among those willing to accept payments, a majority (80.72%) stated they would vote for the highest bidder. A smaller yet significant percentage (18.04%) preferred the earliest payer, while only 1.24% chose the latest payer (Figure 10). On one hand, this finding dispels the assumption held by many candidates that the last payer is most likely to secure votes. On the other hand, it reinforces the overall positive correlation between payment magnitude and the vote “buyer's” success rate. In other words, for most voters, the payment amount does matter. Just as different candidates employ different strategies, different voters hold distinct preferences. This pattern confirms other findings, such as Aspinall et al. (2017), who observed that winning candidates made higher average individual payments to voters (Rp23,700) than losers (Rp17,250). Seat-winning candidates spent an average of 612 million rupiah on vote-buying, while losers spent 253 million rupiah.

Discussion

This study investigates how the public perceives the illegal practice of vote-buying and its implications for democracy, using a case study from West Bandung Regency, Indonesia. We find that vote-buying, which is both legally and morally wrong, is not as stigmatized as one might expect. Nearly half of the respondents accept vote buying as a normal practice in an election, and although accepting it does not mean participating in it, almost all of these respondents expressed their willingness to accept money from candidates. Interestingly, this tendency does not necessarily result in an exchange of money for votes; most of those willing to accept money stated that they would still vote according to their conscience. Equally interesting, respondents tend to be responsive to the amount of money offered, with larger sums increasing the likelihood of acceptance (and voting for the “buyer”). Next, we will critically discuss the implications of these findings for democracy, both at the local and national levels. We argue that vote-buying, which has already been “normalized,” risks turning elections into temporary economic transactions. However, instead of a lack of information and/or income as identified in previous studies, we see inequality of power as the root cause of rampant vote-buying.

Elections as a “harvest season”

Due to its pervasive occurrence and open-secret status in Indonesia, many voters no longer appear particularly troubled by the illegality of vote-buying; over time, they have come to perceive it as an embedded electoral tradition. This “normalization” absolves involved parties of guilt. On one hand, rather than viewing it as bribery, candidates frame monetary offers as “gifts” or compensation for voters sacrificing time and energy—and thus forfeiting potential daily income—to visit polling stations. On the other hand, recipients similarly reject the bribery narrative; instead, they interpret candidates' payments as gestures of generosity, empathy, and economic capability—especially within Indonesia's strong culture of “utang budi” (reciprocal indebtedness) (Theodora, 2024). Furthermore, it is plausible that some voters perceive elections as a “harvest season” granting rare opportunities for easy income, particularly during economic hardship (Fionna, 2015).

The high acceptance rate of vote-buying in our study indicates a market logic underpinning democratic practice. This is evidenced by the conspicuous correlation between monetary amounts and voting behavior: financial incentives exert stronger influence as offered sums increase. Our findings align with—yet methodologically extend—prior research. Aspinall et al. (2017), for instance, documented candidates operating within a market logic: they employ economic terminology while meticulously monitoring competitors' payments and adjusting “prices” when feasible. Conversely, we reveal this market logic equally governs voter behavior. Specifically, voters approach elections as auction markets: supporting candidates who offer the highest monetary or material bids (Nwagwu et al., 2022). This dynamic sustains Indonesia's reputation as a “demokrasi wani piro”—a Javanese term meaning “daring to pay how much” (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019, p. 4).

Without systemic reform, market logic's dominance in elections will perpetually concentrate disproportionate power among the wealthy. In clientelist political arenas, affluent politicians and business allies possess inherent advantages enabling electoral victory, resource access (national or local), and further wealth accumulation (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Hidayat, 2024; Schaffer, 2007c). Consequently, politics becomes an exclusive domain for the financially privileged, creating extreme power imbalances that marginalize the economically vulnerable while further entrenching elites (Matsubayashi and Sakaiya, 2021; Satz, 2010; Taylor, 2017). This exclusivity disadvantages integrity-driven candidates lacking vote-buying funds, regardless of their commitment to public service. Conversely, deep-pocketed candidates—even if they are less competent or criminally implicated—prevail through financial persuasion (Hidayat, 2024). Thus, rather than producing competent and ethical officials, elections become instruments enabling corrupt and immoral politicians to perpetuate power.

Equally critical, given exorbitant campaign costs, elected officials risk entering corruption cycles to recoup expenses. They face pressure to immediately repay campaign debts, satisfy creditors, and fund future elections (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Nwagwu et al., 2022). As Davies (2021) observes in Nigeria, vote-buying victors typically adopt an “investment mindset”: upon gaining budget-accessing positions, they prioritize recovering campaign expenditures (“balik modal” or break-even recovery). Investor-politicians inevitably seek returns—at minimum partial—through any means, even sacrificing essential services. Lewis and Dong (2025) find Indonesia's shift to direct regional elections, particularly in clientelism-intensive areas, moderately increased personnel spending pre- and during election years. Conversely, sharp declines occurred in regional capital expenditures before, during, and after elections. This reflects clientelist systems' inherent disincentive toward public service delivery: politicians often redirect funds toward politically expedient uses (e.g., employee bonuses or travel allowances) to consolidate political support (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019).

Receiving but betraying?

However, it must be noted that this market logic does not always translate into literal transactions. Our findings indicate that the majority of voters willing to accept money still vote according to their conscience rather than the will of the vote “buyer.” This challenges traditional reciprocity theory, wherein vote “sellers” feel compelled to reciprocate the goodwill extended by vote “buyers” (Stockemer and Amaechi, 2024), yet aligns with recent patterns observed in several African (Nwagwu et al., 2022) and South American countries (Muñoz, 2014). This tendency is partly enabled by the secrecy of the ballot, allowing voters freedom to vote according to their own judgment without succumbing to vote buyers' control. In fact, a primary purpose of the secret ballot is to render vote-buying contracts unenforceable or at least excessively risky for candidates, thereby protecting voters vulnerable to coercion (Satz, 2010, pp. 102–103). These “traitorous” voters, if one may call them so, need only show up at the polling station to protect themselves. If they stay home, vote “buyers” would know definitively they did not vote for the designated candidate. By going to the polling station (TPS), voters at least create doubt for the “buyer” due to ballot secrecy (Schaffer, 2007c).

In this context, voters who accept money yet vote conscientiously are not truly engaging in vote trading; they are merely gaining a one-sided benefit (Schaffer and Schedler, 2007). This uncertainty makes elections highly risky for corrupt candidates, as there is no guarantee that voters accepting material offers will reciprocate on election day. As an illegal transaction occurring in a black market and thus unprotected by law, vote buyers can do little if the deal is (quietly) violated. This explains why many candidates experience an “error margin” far exceeding expectations. Aspinall et al.'s (2017) study found that candidates secured votes from only 27% of payments distributed by their teams on average. In Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, Gallego et al.'s (2023) comparative study showed vote buying boosted voter turnout in only 11 of 37 elections, and even fewer where material gifts translated into electoral gains. Nevertheless, Muhtadi (2019b, pp. 213–214) argues that this high “error margin” does not automatically weaken candidates' desire to engage in vote buying, as it can determine victory in intensely competitive elections with narrow winning margins.

The more perplexing puzzle is why voters accept money if they ultimately vote according to conscience. Several explanations illuminate this paradoxical behavior. First, voters may not perceive the money or other gifts they receive as an electoral transaction. It should be noted that vote brokers—often called “tim sukses” (success teams) in Indonesia—rarely explicitly state the purpose of the envelopes they distribute, given vote buying's illegal and taboo nature. They typically assume voters implicitly understand their intent near election time. The problem is, voters lack this same knowledge and thus interpret the money in varied ways. Some may understand and feel obligated to vote for the candidate in the booth, but others may view the money as a non-binding gesture of goodwill (Aspinall and Sukmajati, 2018; Carlin and Moseley, 2022; Schaffer and Schedler, 2007). Consequently, although they accept the money, they feel no indebtedness and still vote according to conscience.

Another potential explanation is that voters are actually punishing corrupt candidates. Several prior studies identify how voters who do not receive payments are more likely to sanction politicians engaged in vote-buying (Guerra and Justesen, 2022). Our findings add that cheating politicians are also punished by voters who accept monetary offers by “betraying” them in the voting booth. As frequently advocated by financially constrained politicians and civil society organizations championing free and fair elections: accept the money or goods offered by corrupt candidates, but still use your secret ballot according to conscience (Davies, 2021). The goal is to reduce or even end vote-buying practices by rendering them ineffective as electoral tactics (Carlin and Moseley, 2022; Tawakkal et al., 2017). Alternatively, voters may be more opportunistic than strategic. They might recognize vote-buying as normatively wrong yet simultaneously realize that their refusal of offered money would not stop the practice. Thus, however aware they are of its damaging illegality, they feel relieved to at least extract personal benefit from a broken system (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019, pp. 252–253). This justification strengthens if they believe post-election benefits will be negligible, as candidates primarily self-enrich once in office (Baniya et al., 2025).

A more plausible explanation is that voters trapped in moral dilemmas. This is best explained through cognitive dissonance theory, which posits that when people experience conflict between two or more contradictory beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors, they feel psychological discomfort and tend to adjust attitudes/behaviors to achieve internal consistency (Harmon-Jones and Mills, 2019). In vote-buying contexts, some voters may recognize the practice's wrongness, yet acute needs—typically economic needs—compel them to accept candidates' cash (Pradhanawati et al., 2019; Tawakkal et al., 2017). This internal tension creates cognitive dissonance: on one hand, they take money to alleviate financial pressure, but on the other hand, they acknowledge vote-buying undermines democratic integrity and is ethically questionable. To resolve this contradiction, voters accept money but vote conscientiously, mentally separating the act of receiving cash from casting their ballot. This compromise lets them enjoy financial gain without fully sacrificing ethical values, reducing psychological discomfort from contradictory behavior.

Toward a more equal society

Efforts to disrupt vote-buying markets require a double-bluff strategy targeting both supply and demand. On the demand side, the most frequently proposed solution is civic or voter education. The premise is simple: strengthening support for norms, idealism, and democratic governance can weaken vote-buying. Public education is believed to enhance citizens' normative conviction that money politics harms governance, representation, and democracy—making them reluctant to engage in it (Carlin and Moseley, 2022; Gherghina and Tap, 2024; Vicente, 2014). However, the assumption that adequate information reduces voter participation in vote-buying proves incomplete. First, while public education may alter voters' normative evaluation of vote-buying, it fails when voters' primary motive is economic need (Pradhanawati et al., 2019; Tawakkal et al., 2017). Second, it overlooks the fundamental reality of moral obligations sometimes binding “sellers” to “buyers.” When educators—as often occurs—focus narrowly on instrumental motives while failing to acknowledge the social pressures and expectations driving vote-selling, public education becomes hollow or even counterproductive (Schaffer, 2007a,b). We emphatically do not claim civic education is futile; we argue only that it should not be overrelied upon merely because it is logistically simpler than macrostructural solutions.

Some observers' suggestions to increase income and middle-class growth have also not been entirely effective. This approach indeed accurately captures the reality that voters with economic disadvantages are the most vulnerable to engaging in vote-buying practices (Kramon, 2016; Ravanilla and Hicken, 2023; Shin, 2015; Tawakkal et al., 2017). Economic pressures lead many voters to sacrifice their independence for at least one day's worth of food. At the same time, corrupt candidates tend to target poor voters because they are more “affordable” to buy, explaining why candidates start their dirty practices from the bottom rather than the top of the income distribution. Based on this conception, it makes sense to assume that wealth will reduce voters' electoral vulnerability. However, this assumption has a serious flaw because it assumes that average income growth will only increase voters' wealth. In fact, economic development means more resources for both voters and candidates, so ultimately the prevalence of vote-buying may not be affected (Gherghina and Tap, 2024; Hicken, 2007).

We contend that such solutions remain ineffective without addressing vote-buying's root causes: economic and political inequality. Extensive research documents how clientelism thrives in regions with undiversified economies and power concentrated among elites (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Lehoucq, 2007; Matsubayashi and Sakaiya, 2021; Stokes, 2007). This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: unequal systems perpetuate dependence on patrons who exploit economic disparities to retain power, deterring voters from demanding better public services. When citizens rely on short-term elite handouts rather than demanding policy reforms for long-term gains, dependency deepens. Thus, mere income growth is insufficient; combating vote-buying requires economic diversification and redistributed political power (Noak, 2024). Only then can citizens gain autonomy from elites and generate social counterpressure against clientelism (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019).

Disrupting the supply side of vote-buying poses equal complexity. Candidates face a “prisoner's dilemma” during elections (Muhtadi, 2015): if one candidate deploys money politics, abstainers risk defeat. Thus, while vote-buying does not guarantee victory, non-participants almost certainly lose. Though politicians may desire alternative tactics, fear of losing to well-funded rivals locks them into conventional approaches. This dynamic frames vote-buying eradication as a collective action problem—where actors await others' moves before changing their own (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019, pp. 252–253). Resolving this requires cross-tier political will to combat the practice (Lundstedt and Edgell, 2022; Nwagwu et al., 2022). Legislation that prohibits or strictly regulates vote-buying is a first step, but it is clearly not enough. In fact, this form of fraud has been strictly prohibited in election regulations, namely Law No. 7 of 2017 in Indonesia, but vote-buying continues to be rampant. To truly prevent candidates from buying votes, anticipatory measures must increase the probability of detection and related sanctions. Sanctions can vary, ranging from fines to lifetime political bans, with significant imprisonment/office disqualification proving most impactful for ambitious politicians (Hicken, 2007).

This research highlights the complex relationship between clientelistic practices like vote-buying and decentralization, which has reshaped local democracy in developing countries, including Indonesia. This study highlights the complex relationship between client-abuse practices such as vote buying and decentralization, which have reshaped local democracy in developing countries, including Indonesia. Related to this, there is a study conducted by Dutta with a research locus in Bangladesh, which states that the main purpose of decentralization is to distribute power fairly and optimize governance efficiency to counter traditional clientism (Dutta, 2020). However, experts have observed that the large-scale decentralization movements in the developing world over the past three decades have instead spawned new clientelistic practices alongside traditional ones among socio-political actors created by decentralization itself (García-Guadilla and Pérez, 2002; Khemani, 2015; León and Wantchekon, 2019). How does this paradox arise? We argue that democratic decentralization can dismantle clientelistic practices—including vote-buying—only when it deliberately distributes decision-making sovereignty, not merely administrative functions. As long as decentralization relocates authority without redistributing power, clientelism will not end; it will only become more diffuse, enhancing local elites' expertise in perpetuating patronage networks. Such decentralization increasingly resembles privatization, managerial deconcentration, and heightened inequality. By contrast, decentralization should elevate democracy from mere representation to participation, where citizens engage in defining collective problems and solutions (Mookherjee, 2015).

Our argument explains why decentralization succeeds or fails in combating clientelism (such as vote-buying) across global regions—from Asia and Africa to Europe and Latin America. In the Philippines, decentralization did increase citizen participation in local governance. However, political dynasties swiftly co-opted this engagement to tighten their grip by creating clientelistic dependencies, turning participation into a tool for local control (Porio, 2017). In Venezuela and Ukraine, decentralization emphasized deconcentration and privatization of responsibilities rather than political decentralization through participatory democracy. Consequently, local and regional elites retained power with little challenge from grassroots movements (Bondarenko, 2025; García-Guadilla and Pérez, 2002). Moreover, decentralization often empowers local politicians and elites, enhancing their skill and flexibility in targeting benefits to key voters and organized interest groups in exchange for political support (Khemani, 2015). State-driven top-down development models combined with depoliticized decentralization have fueled political personalization. In consolidating democracies like Indonesia, Pakistan, India, and African nations, decentralization and democratization do reform formal institutions. Yet old informal norms remain dominant, often overriding formal state procedures with laws. Thus, personal clientelistic ties continue to define political and economic relationships (Bénit-Gbaffou, 2011; Hidayat et al., 2025; Rehman and Javed, 2016; Sadanandan, 2012).

We emphasize that we do not reject decentralization. Rather, we deem it necessary yet insufficient when limited to redistributing authority. When top-down control loosens, power must be equitably redistributed to establish robust bottom-up oversight mechanisms. Without this, decentralization risks exacerbating clientelistic systems—including vote-buying. Drawing from West Bandung Regency and global comparisons, we propose that democracy-based decentralization hinges on the autonomy and consolidation of social movements. Civil society cannot expect clientelistic elites to voluntarily reform institutions or share power. Change requires collective citizen action: leveraging democratic rights to sanction politicians, building advocacy coalitions, and pressuring state authorities (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2017; Berenschot and Aspinall, 2020; Berenschot and Mulder, 2019). Thus, while decentralization is often assumed to organically generate social movements capable of dismantling clientelism, we argue the inverse: strong, organized social movements are the essential prerequisite for successful decentralization and democratization in combating clientelism. Only then do incentive structures emerge that motivate competent leaders to promote accountability and implement policy reforms.

Conclusion

This article reveals that public perception of vote buying in West Bandung Regency is not as stigmatized as expected, even though the practice is illegal. Nearly half of respondents consider vote-buying to be a normal practice, and almost all of these respondents expressed their willingness to accept money from candidates. Interestingly, even though many were willing to accept money, the majority of respondents still said they would vote according to their conscience. In other words, monetary transactions do not always result in a direct exchange of money for votes. Equally intriguing, respondents demonstrated a sensitive response to the amount of money offered, with larger sums increasing the likelihood of acceptance and voting for the money provider in the voting booth. These findings indicate that (electoral) democracy, to a certain extent, can be traded for a momentary economic transaction. However, such transactions are fluid and uncertain; the money distributed does not always translate into votes. This ambivalence highlights how vote-buying can become a common and debated practice within the same community.

The implications of these findings for democracy are highly significant. The normalized practice of vote-buying has led some voters to perceive this fraud as part of electoral tradition. Coupled with market logic influencing voter behavior, elections risk yielding disproportionate power for financial elites. This dynamic clearly benefits wealthy politicians and their business allies while deepening power imbalances in society. Consequently, elections become fragile and tend to fail in producing competent and ethical public officials. Instead, this environment enables corrupt politicians to endure—even after being proven guilty of criminal acts—because the system fails to ensure moral accountability. Thus, we argue that the root problem extends beyond individual moral decay promoting vote-buying; it lies in systemic governance failure where decentralization paradoxically strengthens political capture and personalization in politics. To counter this, rather than rejecting decentralization, it must be redirected to distribute power equitably—not merely through administrative devolution, but by involving citizens in collective decision-making. Historically, decentralization was assumed to automatically generate social movements eradicating clientelism. Instead, we contend that strong, organized social movements are a primary prerequisite for successful decentralization itself.

This study makes a significant contribution by presenting perceptual data on money politics through a spatial case study in West Bandung Regency. Our research creates opportunities to enrich understanding of how vote-buying practices are perceived within local contexts, while simultaneously stimulating theoretical development in political science. However, several limitations should also be noted. For instance, the data we collected and the analytical techniques employed did not allow us to uncover relationships between socioeconomic status and public perceptions of vote-buying. Additionally, the hypothetical vote-buying scenarios outlined in our survey instrument reflect a relatively narrow view of how such transactions operate in practice, since money politics often constitutes part of long-term clientelistic relationships rather than one-time exchanges. At the same time, our survey question construction focused exclusively on a highly specific form of clientelism: cash-for-votes exchanges during election campaigns. Further research is essential to comprehensively understand factors influencing stigma across diverse electoral contexts. Would stigma diminish when money politics transactions involve repeated interactions and thus more closely resemble established relationships? Would other forms of targeted distributive politics—such as patronage, club goods provision, or conditional cash transfer programs—demonstrate equivalent levels of social rejection? Vote-buying remains a widespread yet enigmatic practice, whose secrets can only be gradually uncovered.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

All the participants (respondents) provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. KN: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AS: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MJ: Writing – review & editing. AR: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN, Indonesian: Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. A. (2017). Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity and poverty (A. Subiyanto, Trans.). Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo.

Alhamidi, R. (2024). Politik uang dominasi pelanggaran pemilu di Jabar. Detik Jabar. Available online at: https://www.detik.com/jabar/berita/d-7176244/politik-uang-dominasi-pelanggaran-pemilu-di-jabar

Aspinall, E., and Berenschot, W. (2019). Democracy for Sale: Elections, Clientelism, and the State in Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Aspinall, E., Rohman, N., Hamdi, A. Z., Rubaidi, and Triantini, Z. E. (2017). Vote buying in Indonesia: candidate strategies, market logic and effectiveness. J. East Asian Stud. 17, 1–27. doi: 10.1017/jea.2016.31

Aspinall, E., and Sukmajati, M., (eds.) (2018). Electoral Dynamics in Indonesia: Money Politics, Patronage and Clientelism at the Grassroots. Singapore: NUS Press Pte Ltd.

Baniya, J., Meserve, S. A., Pemstein, D., and Seim, B. (2025). Vote buying and local public goods provision: substitutes or complements? Am. J. Pol. Sci. 12982. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12982

Bénit-Gbaffou, C. (2011). ‘Up close and personal' – how does local democracy help the poor access the state? Stories of accountability and clientelism in Johannesburg. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 46, 453–464. doi: 10.1177/0021909611415998

Berenschot, W., and Aspinall, E. (2020). How clientelism varies: comparing patronage democracies. Democratization 27, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1645129

Berenschot, W., and Mulder, P. (2019). Explaining regional variation in local governance: clientelism and state-dependency in Indonesia. World Dev. 122, 233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.021

Blair, G., Coppock, A., and Moor, M. (2020). When to worry about sensitivity bias: a social reference theory and evidence from 30 years of list experiments. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 1297–1315. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000374

Blair, G., and Imai, K. (2012). Statistical analysis of list experiments. Polit. Anal. 20, 47–77. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpr048

Bondarenko, O. (2025). Failure or success? Regime fragmentation in the context of decentralization reform in Ukraine. Democratization, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2025.2511760

Carlin, R. E., and Moseley, M. W. (2022). When clientelism backfires: vote buying, democratic attitudes, and electoral retaliation in Latin America. Polit. Res. Q. 75, 766–781. doi: 10.1177/10659129211020126

Davies, A. E. (2021). “Money politics in the Nigerian electoral process,” in Nigerian Politics, Eds. R. Ajayi and J. Y. Fashagba (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 341–352.

Driscoll, B. (2018). Why political competition can increase patronage. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 53, 404–427. doi: 10.1007/s12116-017-9238-x

Dutta, P. (2020). Democratic decentralization and participatory development: focus on Bangladesh. J. Contemp. Gov. Public Policy 1, 82–91. doi: 10.46507/jcgpp.v1i2.23

Finan, F., and Schechter, L. (2012). Vote-buying and reciprocity. Econometrica 80, 863–881. doi: 10.3982/ECTA9035

Fionna, U. (2015). “Vote-buying in Indonesia's 2014 elections: the other side of the coin,” in ISEAS Perspective: Watching the Indonesian Elections 2014, ed. U. Fionna (Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute), 94–102. Available online at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/iseas-perspective/votebuying-in-indonesias-2014-elections-the-other-side-of-the-coin/90B6EE49F3DC9116E7FD787786E3F002 (Accessed December 2024).

Gallego, J., Guardado, J., and Wantchekon, L. (2023). Do gifts buy votes? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. World Dev. 162:106125. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106125

Gallego, J., and Wantchekon, L. (2012). “Experiments on clientelism and vote-buying,” in Research in Experimental Economics, Vol. 15, Eds. D. Serra and L. Wantchekon (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 177–212.

Gans-Morse, J., and Nichter, S. (2021). Would you sell your vote? Am. Polit. Res. 49, 452–463. doi: 10.1177/1532673X211013565

García-Guadilla, M. P., and Pérez, C. (2002). Democracy, decentralization, and clientelism: new relationships and old practices. Lat. Am. Perspect. 29, 90–109. doi: 10.1177/0094582X0202900506

Gherghina, S., and Tap, P. (2024). Selling their vote expensively: the effects of information, apathy and age. Party Polit. 30:13540688241311866. doi: 10.1177/13540688241311866

Gonzalez-Ocantos, E., De Jonge, C. K., Meléndez, C., Osorio, J., and Nickerson, D. W. (2012). Vote buying and social desirability bias: experimental evidence from Nicaragua. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 202–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00540.x

Gonzalez-Ocantos, E., De Jonge, C. K., and Nickerson, D. W. (2014). The conditionality of vote-buying norms: experimental evidence from Latin America. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 58, 197–211. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12047

Guerra, A., and Justesen, M. K. (2022). Vote buying and redistribution. Public Choice 193, 315–344. doi: 10.1007/s11127-022-00999-x

Gunawan, D. (2024). Dugaan Politik Uang Pilkada Bandung Barat, Warga Terima Amplop Rp50 Ribu. Media Indonesia. Available online at: https://mediaindonesia.com/jabar/berita/721166/dugaan-politik-uang-pilkada-bandung-barat-warga-terima-amplop-rp50-ribu (Accessed December 2024).

Harmon-Jones, E., and Mills, J. (2019). “An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory,”. in Cognitive Dissonance: Reexamining a Pivotal Theory in Psychology, 2nd ed., ed. E. Harmon-Jones (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 3–24.

Hatz, S., Fjelde, H., and Randahl, D. (2024). Could vote buying be socially desirable? Exploratory analyses of a ‘failed' list experiment. Qual. Quant. 58, 2337–2355. doi: 10.1007/s11135-023-01740-6

Hicken, A. D. (2007). “How do rules and institutions encourage vote buying?,” in Elections for Sale, ed. F. C. Schaffer (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 47–60.

Hidayat, A. R., Hospes, O., and Termeer, C. J. A. M. (2025). Why democratization and decentralization in Indonesia have mixed results on the ground: a systematic literature review. Public Adm. Dev. 45, 159–172. doi: 10.1002/pad.2095

Hidayat, F. (2024). Money politics in a democratic political system: a case study of South Korea and European countries. Bestuurskunde J. Gov. Stud. 4, 101–114. doi: 10.53013/bestuurskunde.4.2.101-114

Indikator (2024). Rilis Exit Poll Pilpres 2024 Indikator: Basis Demografi Dan Perilaku Pemilih. Jakarta: Indikator. Available online at: https://indikator.co.id/rilis-exit-poll-pilpres-2024-indikator/ (Accessed December 2024).

Khemani, S. (2015). “Political capture of decentralization: vote buying through grants to local jurisdictions” in Is Decentralization Good For Development?, Eds. J.-P. Faguet and C. Pöschl (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 196–223.

Komarudin, U., Handoko, W., and Hussain, F. (2025). Money politics and voter behavior: factors behind incumbent defeat in Subang Regency's 2024 regional election. Jurnal Hukum 41, 216–235.

Kramon, E. (2016). Electoral handouts as information: explaining unmonitored vote buying. World Polit. 68, 454–498. doi: 10.1017/S0043887115000453

Lehoucq, F. (2007). “When does a market for votes emerge?” in Elections for Sale, ed. F. C. Schaffer (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 33–46.

León, G., and Wantchekon, L. (2019). “Clientelism in decentralized states,” in Decentralized Governance and Accountability, 1st ed., Eds. J. A. Rodden and E. Wibbels (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 229–247.

Lewis, B. D., and Dong, S. (2025). The transition to direct mayoral elections in clientelistic environments: causal public spending and service delivery effects. J. Dev. Econ. 172:103380. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2024.103380

Lundstedt, M., and Edgell, A. B. (2022). Electoral management and vote-buying. Electoral Stud. 79:102521. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102521

Matsubayashi, T., and Sakaiya, S. (2021). Income inequality and income bias in voter turnout. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 66:101966. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2020.101966

Mookherjee, D. (2015). Political decentralization. Annu. Rev. Econ. 7, 231–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115527

Muhtadi, B. (2015). Money Politics and the Prisoner's Dilemma. New Mandala. Available online at: https://www.newmandala.org/money-politics-and-the-prisoners-dilemma/ (Accessed December 2024).

Muhtadi, B. (2019a). “The prevalence of vote buying in Indonesia: building an index,” in Vote Buying in Indonesia (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 45–79.

Muhtadi, B. (2019b). Vote buying in Indonesia: the mechanics of electoral bribery, 1st edn. Singapore: Springer Singapore Pte. Limited.

Muñoz, P. (2014). An informational theory of campaign clientelism: the case of Peru. Comp. Polit. 47, 79–98. doi: 10.5129/001041514813623155

Murugesan, A., and Tyran, J.-R. (2023). The Puzzling Practice of Paying “Cash for Votes” (Working Paper 10504). CESifo. Available online at: https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=4477992 (Accessed December 2024).

Noak, P. A. (2024). Political clientelism in rural areas: understanding the impact on regional head elections in Indonesia. J. Ecohumanism 3, 3898–3909. doi: 10.62754/joe.v3i7.4517

Noor, F., Siregar, S. N., Hanafi, R. I., and Sepriwasa, D. (2021). The implementation of direct local election (Pilkada) and money politics tendencies: the current Indonesian case. Politik Indonesia Indones. Polit. Sci. Rev. 6, 227–246. doi: 10.15294/ipsr.v6i2.31438

Nwagwu, E. J., Uwaechia, O. G., Udegbunam, K. C., and Nnamani, R. (2022). Vote buying during 2015 and 2019 general elections: manifestation and implications on democratic development in Nigeria. Cogent Soc. Sci. 8:1995237. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2021.1995237

Populix (2024). Partisipasi dan opini publik menjelang pilkada 2024: politik dinasti dan politik uang. Jakarta: Populix. Available online at: https://info.populix.co/data-hub/reports/partisipasi-dan-opini-publik-menjelang-pilkada-2024-politik-dinasti-dan-politik-uang (Accessed December 2024).

Porio, E. (2017). “Citizen participation and decentralization in the Philippines,” in Citizenship and Democratization in Southeast Asia, Eds. W. Berenschot, H. S. Nordholt, and L. Bakker (Leiden: Brill), 31–50.

Pradhanawati, A., Tawakkal, G. T. I., and Garner, A. D. (2019). Voting their conscience: poverty, education, social pressure and vote buying in Indonesia. J. East Asian Stud. 19, 19–38. doi: 10.1017/jea.2018.27

Prihatini, E. S., and Wardani, S. B. E. (2024). The Cost of Politics in Indonesia. Westminster Foundation for Democracy Limited. Available online at: https://costofpolitics.net/asia-and-the-pacific/indonesia (Accessed December 2024).

Ravanilla, N., and Hicken, A. (2023). Poverty, social networks, and clientelism. World Dev. 162:106128. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106128

Rehman, A., and Javed, S. A. (2016). I Give You Vote; What Will You Give Me? A Vote Exchange Perspective From Democratic Decentralization in Pakistan. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301478228_Working_Paper_154_I_Give_You_Vote_What_Will_You_Give_Me_A_Vote_Exchange_Perspective_from_Democratic_Decentralization_in_Pakistan

Sadanandan, A. (2012). Patronage and decentralization: the politics of poverty in India. Comp. Polit. 44, 211–228. doi: 10.5129/001041512798837996

Saputra, A. B., and Setiawan, A. (2023). Does money triumph over identity? A survey findings from the local levels. Politik Indonesia Indones. Polit. Sci. Rev. 8:3. doi: 10.15294/ipsr.v8i2.42301

Satz, D. (2010). Why Some Things Should Not be for Sale: The Moral Limits of Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, F. C. (2007a). “How effective is voter education?” in Elections for Sale, ed. F. C. Schaffer (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 161–180.

Schaffer, F. C. (2007b). “Lessons learned,” in Elections for Sale, ed. F. C. Schaffer (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 183–200.

Schaffer, F. C. (2007c). “Why study vote buying?,” in Elections for Sale, ed. F. C. Schaffer (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 1–16.

Schaffer, F. C., and Schedler, A. (2007). “What is vote buying?” in Elections for Sale, ed. F. C. Schaffer (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 17–30.

Shin, J. H. (2015). Voter demands for patronage: evidence from Indonesia. J. East Asian Stud. 15, 127–151. doi: 10.1017/S1598240800004197

Stockemer, D., and Amaechi, O. C. (2024). Why do voters accept bribes? Evidence from Edo State in Nigeria. Representation 60, 303–323. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2023.2213722

Stokes, S. C. (2007). “Is vote buying undemocratic?” in Elections for Sale, ed. F. C. Schaffer (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), 81–100.

Tawakkal, G. T. I., Suhardono, W., Garner, A. D., and Seitz, T. (2017). Consistency and vote buying: income, education, and attitudes about vote buying in Indonesia. J. East Asian Stud. 17, 313–329. doi: 10.1017/jea.2017.15

Taylor, J. S. (2017). Markets in votes and the tyranny of wealth. Res Publica 23, 313–328. doi: 10.1007/s11158-016-9327-0

Theodora, A. (2024). Politik uang dan komoditas “suara rakyat”. Kompas.id. Available online at: https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2024/01/11/politik-uang-dan-pemilu-pasar-bebas

Keywords: vote-buying, money politics, clientelism, public perception, elections

Citation: Djuyandi Y, Nugraha KP, Sugiharto A, Jamri MH and Ridzuan AR (2025) Normalizing the illegal: public perceptions of vote-buying in West Bandung Regency and its democratic consequences. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1630335. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1630335

Received: 17 May 2025; Accepted: 16 July 2025;

Published: 06 August 2025.

Edited by:

Andi Luhur Prianto, Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Cecep Darmawan, Indonesia University of Education, IndonesiaSaddam Rassanjani, Syiah Kuala University, Indonesia

Aditya Batara Gunawan, Bakrie University, Indonesia

Jatswan Singh, Taylor's University, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Djuyandi, Nugraha, Sugiharto, Jamri and Ridzuan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yusa Djuyandi, eXVzYS5kanV5YW5kaUB1bnBhZC5hYy5pZA==

Yusa Djuyandi

Yusa Djuyandi Kiki Pratama Nugraha2

Kiki Pratama Nugraha2 Agus Sugiharto

Agus Sugiharto Mohamad Hafifi Jamri

Mohamad Hafifi Jamri Abdul Rauf Ridzuan

Abdul Rauf Ridzuan