- Department of Political Science and International Studies, College of Social Sciences, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Introduction: The knowledge and technology North Korea possessed concerning nuclear weapons systems during the first nuclear crisis in the period from 1993 to 1994 are incomparable to what they hold today. While the discourse on North Korea’s nuclear threat in the 2020s remains largely the same as it was in the early 1990s, the significant advancements in the country’s nuclear technology are noteworthy.

Methods: Using the concept of crisis and securitization, this article examines the patterns of discourse during the first and second Korean nuclear crises and explores the factors contributing to the relative absence of discourse on a third nuclear crisis.

Results: This analysis reveals that the securitization process regarding North Korea’s nuclear threat has become routinized, thereby diminishing its performative urgency.

Discussion: First, this analysis enables a reflexive examination of the nuclear crisis, challenging the casual use of the term crisis. Second, it facilitates an analysis that minimizes ideological bias. Third, it sheds light on the underlying permissive factors sustaining the protracted discourse on North Korea’s nuclear threat. Rather than proposing an illusory solution, this article constructs a novel framework for analyzing the Korean nuclear crisis and suggests a more informed direction for future securitization efforts.

1 Introduction

In retrospect, North Korea’s nuclear threat, spanning from the 1990s to the 2020s, has always been considered imminent and intolerable. As if North Korea was going to launch nuclear-tipped missiles shortly, the security actors—both practitioners and theorists—have vigorously argued that Pyŏngyang’s nuclear adventurism must be ended now otherwise the security of the international community would be on the verge of breaking down. In other words, North Korea’s nuclear threat has long been securitized. For an issue to be securitized, the issue needs to be elevated to a level of crisis, since “securitized issues are recognized by a specific rhetorical structure stressing urgency, survival, and ‘priority of action’” (Nyman, 2013, p. 53).

A crisis is typically “acute rather than chronic” (Eastham et al., 1970, p. 466). Merriam-Webster defines crisis as “an unstable or crucial time or state of affairs in which a decisive change is impending.” The Korean nuclear issue has been dubbed the “30 years of North Korean nuclear crisis” (Jun, 2023). Differently put, the issue has always been a crisis—so much so that the issue has been rhetorically securitized. Notably, the knowledge and technology that North Korea possessed concerning nuclear weapons during the 1990s cannot be compared to what they now possess. While Pyŏngyang has detonated atomic and hydrogen bombs and reinforced its nuclear power status by assembling more warheads, testing hypersonic missiles, and maneuvering a spy satellite, the essence of the discourse on North Korea’s nuclear threat in the 2020s remains similar to that of the early 1990s: dismantle your nuclear weapons completely, verifiably, and irreversibly then you will become a prosperous nation.

Another intriguing point is that while the discourses of the first and second North Korean nuclear crises (in 1993–1994 and 2002–2003, respectively) are widespread in academia and among practitioners (Bluth, 2011; Pollack, 2011; Wit et al., 2004), there is no consensus on when the third North Korean nuclear crisis occurred, if any, and what kind of crisis emerged after the second one. Looking at the nuclear crisis discourse from this critical viewpoint is important, because otherwise people would become insensitive to the real level of the threat and numbed by the incessant crisis discourse which, in turn, has already resulted in the 30 years of crisis. Based on this perspective, this analysis addresses the following research question: Why and how has the security discourse surrounding the North Korean nuclear threat become one of habitual securitization?

Methodologically, this study employs conceptual analysis and constructive theorizing. By identifying gaps in existing literature and synthesizing relevant concepts, this analysis proposes a novel analytical framework that serves as a foundation for future theoretical development and policy formulation by scholars and security practitioners. Rather than pursuing empirical generalization, the analysis focuses on constructing a theoretical argument that bridges concepts and theories.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows. First, by examining key terms related to this study, it puts forward a conceptual framework for analysis of the Korean nuclear crisis. Next, it outlines the dominant pattern of security discourse during the first and second crises. It then explores the reasons for the relative absence of a third nuclear crisis discourse, despite North Korea conducting several nuclear tests and continuously enhancing its nuclear capabilities thereafter. Subsequently, attention is turned to reflections on the main concepts of the analysis, highlighting that the current structure of security discourse restricts the means for resolving the protracted and complex security issue. Finally, this article concludes by drawing lessons and suggesting policy implications.

2 A conceptual framework

2.1 Parallel and inter-complementary concepts: crisis and securitization

As a material dimension, crisis is sometimes considered equivalent to threats “as existing in real-world form in the world.” From a subjective viewpoint, however, crisis could refer to “individual judgments and perceptions” (Kalbassi, 2016, p. 111). Hermann (1969, p. 414) saw crisis as “a situation that threatens high-priority goals of the decision-making unit.” In the same vein, crisis can be seen as “a serious threat to the basic structures or the fundamental values and norms of a social system, which—under time pressure and highly uncertain circumstances—necessitates making critical decisions” (Rosenthal et al., 1989, p. 10). Despite these definitions, the concept of crisis remains ambiguous. The seriousness of the threat, the determination of its severity, the establishment of values and norms, and the level of uncertainty in the situation are all subject to interpretation. Consequently, the main characteristics of a crisis remain open to debate.

In the realm of security studies, the logic that operates a securitization process is strikingly similar to that of a crisis. Securitization is a discursive process through which “an issue is dramatized and presented as an issue of supreme priority; thus, by labeling it as security an agent claims a need for and a right to treat it by extraordinary means” (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 26). The fact that securitization is a discursive process means that security is “language viewed in a certain way” (Fairclough, 2013, p. 7). However, discourse is not just language. Discourse is a more inclusive term that contains a meaning-making process. To put it differently, discourse does not merely depict the world as it is, but rather how we envision it to be. Discourse, therefore, emerges as the language of social practice (Fairclough, 2013). If we define discourse as the use of language in a broad manner, securitization, then, can refer to the activities using security-related languages. In the process, crisis discourse is a powerful medium through which a specific issue can be seen as something that holds a significant “position from which the act can be made” (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 32).

In summary, both crisis and securitization reside in the domain of interpretation, with the concept of threat at the core. As noted, a crisis begins when actors articulate something as a serious threat. The same applies to the securitization process. As soon as securitizing actors designate something as an existential threat, the utterance itself becomes the security act (Wæver, 1995, p. 55). The notion that crisis and securitization begin with the linguistic construction of existential threats implies the need for a thorough examination of the inherent characteristics of such threats. The constitution of a threat can be understood as stemming from the materiality itself (e.g., the nuclear weapons or fissile materials), the characteristics of the Other who governs that materiality (e.g., the North Korean regime), or our (the Self’s) perception that frames the Other as an antagonistic entity. If the intensity of a threat could be measured objectively, it would then be possible to gauge the objectivity of security discourse, thereby clarifying the criteria for crisis and securitization. However, this is an exceedingly challenging task. If it were feasible, the concept of the security dilemma would never have arisen in the first place. If materiality alone ensured objectivity, debates about distinguishing between offensive and defensive weapons would not occur. Similarly, disputes over the criteria for determining the beginning and end of life would not exist. Dilemmas arise from the difficulty of interpreting the motivations, intentions, and capabilities of an entity presumed to be an adversary, whether potential or actual. This represents an “unresolvable uncertainty,” inherently linked to an “existential condition” (Booth and Wheeler, 2013, p. 138).

2.2 A new framework for analysis of the Korean nuclear crisis

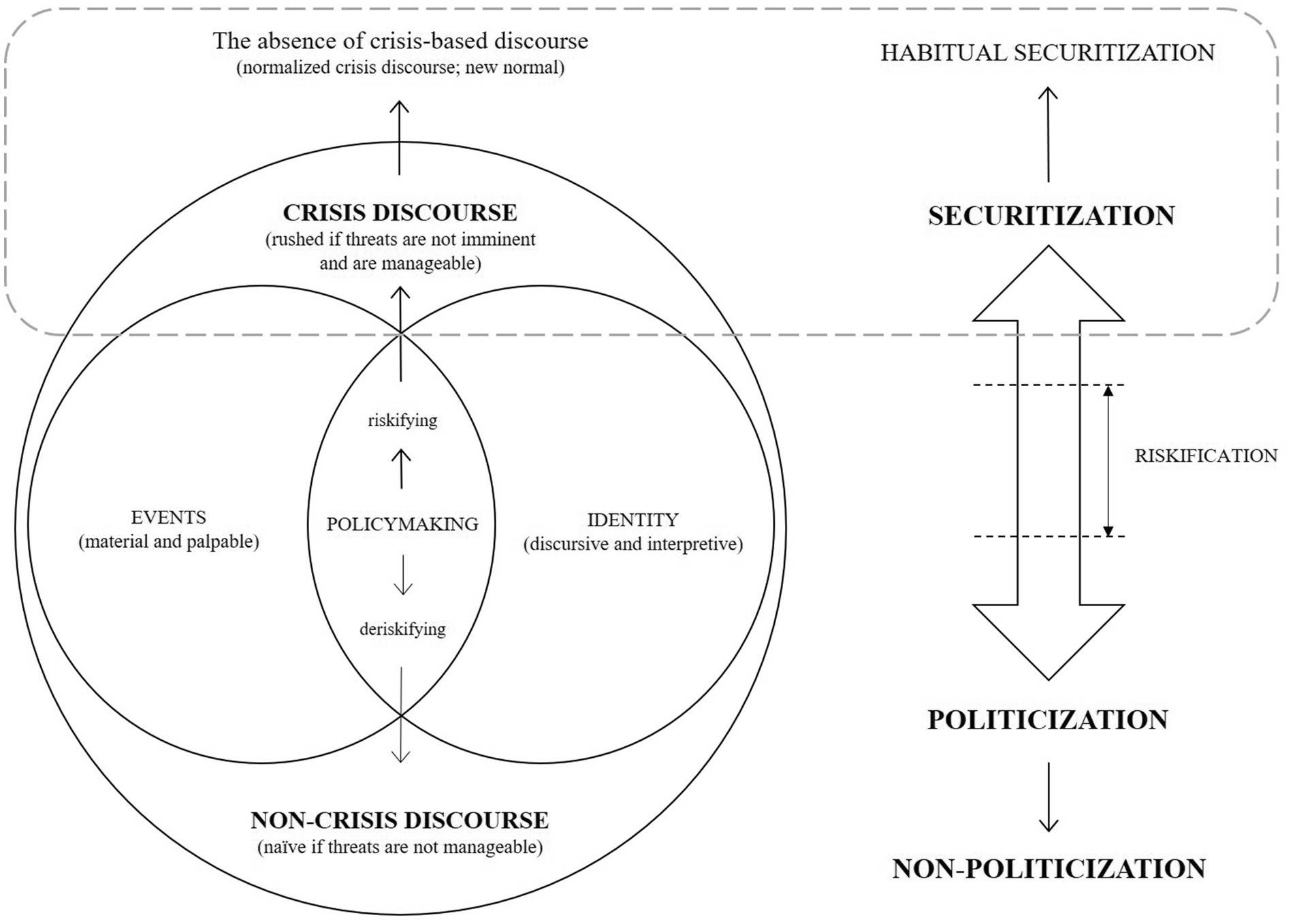

Having gained insights into the relations between crisis and securitization, Figure 1 shows the ways in which the two concepts are parallel and complemented by each other. First, at the heart of the space where crisis discourse and securitization take place are the policymakers (i.e., securitizing actors). The policymakers refer to “actors who securitize issues by declaring something—a referent object—existentially threatened” (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 36). Of course, the declaration does not occur in a vacuum. Despite speech acts being core components of securitization, policymakers still need to show something which is material or palpable to persuade the audience that the threat is real. Nevertheless, to reiterate, for one issue to be securitized, a discursive and interpretive process, which can be materialized through the lens of policymakers’ identities—whether they be formed by implicit assumptions, inferencing, or ideological convictions—is inevitable. In this respect, the securitizing actor straddles between the realm of events and identity.

The key here lies in the degree of the utterance, which can determine whether a specific issue can remain at a level of the normal political realm or beyond it. Regarding this, securitization is considered “a more extreme version of politicization” (Buzan et al., 1998, p. 23). As is shown on the right of Figure 1, securitization theory categorizes public issues into three main stages. In the non-politicized stage, the issue remains off the radar and policymakers do not handle it. Once the issue becomes politicized, it demands government decisions and allocation of political resources. In the securitized stage, the issue calls for emergency measures and justifies governmental actions that exceed the normal bounds of political procedures. The problem, however, comes from the rather obscure boundaries between the stages. The ambiguity surrounding the definition of crisis aligns with the distinction between securitization and politicization. What constitutes a security threat (i.e., crisis) and what does not (i.e., non-crisis)? As pointed out by Emmers (2013), the securitization spectrum lacks a clear boundary between an act of securitization and intense politicization. The realms of security and politics exist on a continuum.

Blanket labeling of any danger or risk as a security issue without considering the level and existentiality of the threat can lead to confusion, fatigue, and even numbness among security actors and audiences regarding the actual threat (habitual securitization). This is particularly important in that such a securitizing practice would lose a sense of urgency even if a genuinely imminent attack from the enemy is around the corner, i.e., the securitizing actors are “crying wolf.” The Taliban’s capture of Kabul in 2021 would be a case in point. On 14 August 2021, the US State Department proclaimed that “Kabul is not right now in an imminent threat environment” (Reuters, 2021). The Taliban seized Kabul the very next day. This marked the paradoxical conclusion of the United States’ two-decade-long habitual securitization against the Taliban. Adding to the irony, and coupled with the swift US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the newly established Taliban regime stated that there was no evidence that Osama bin Laden, regarded as the direct cause of the Afghanistan War, could be linked to the 9/11 attacks (Pannett, 2021).

In the context of habitual securitization, the crisis discourse pales into insignificance. As is illustrated on the left of Figure 1, if such discourse was formed in a rushed manner when threats are not imminent (or not genuine), the crisis is likely to be normalized as time goes by and, at some point, when the crisis-based discourse becomes so mundane, it would become the new normal. In a sense, this would be equivalent of the absence of crisis-based discourse because policymakers have to accept, at this stage, that they have no other options but to manage the crisis, which is, strictly speaking, no longer a crisis, but a reality. Conversely, when policymakers do not detect the emergency of the threat, when the threat is already imminent or not controllable, the consequence would be fatal, as in the events in Kabul in August 2021 or in Southern Israel in October 2023.1

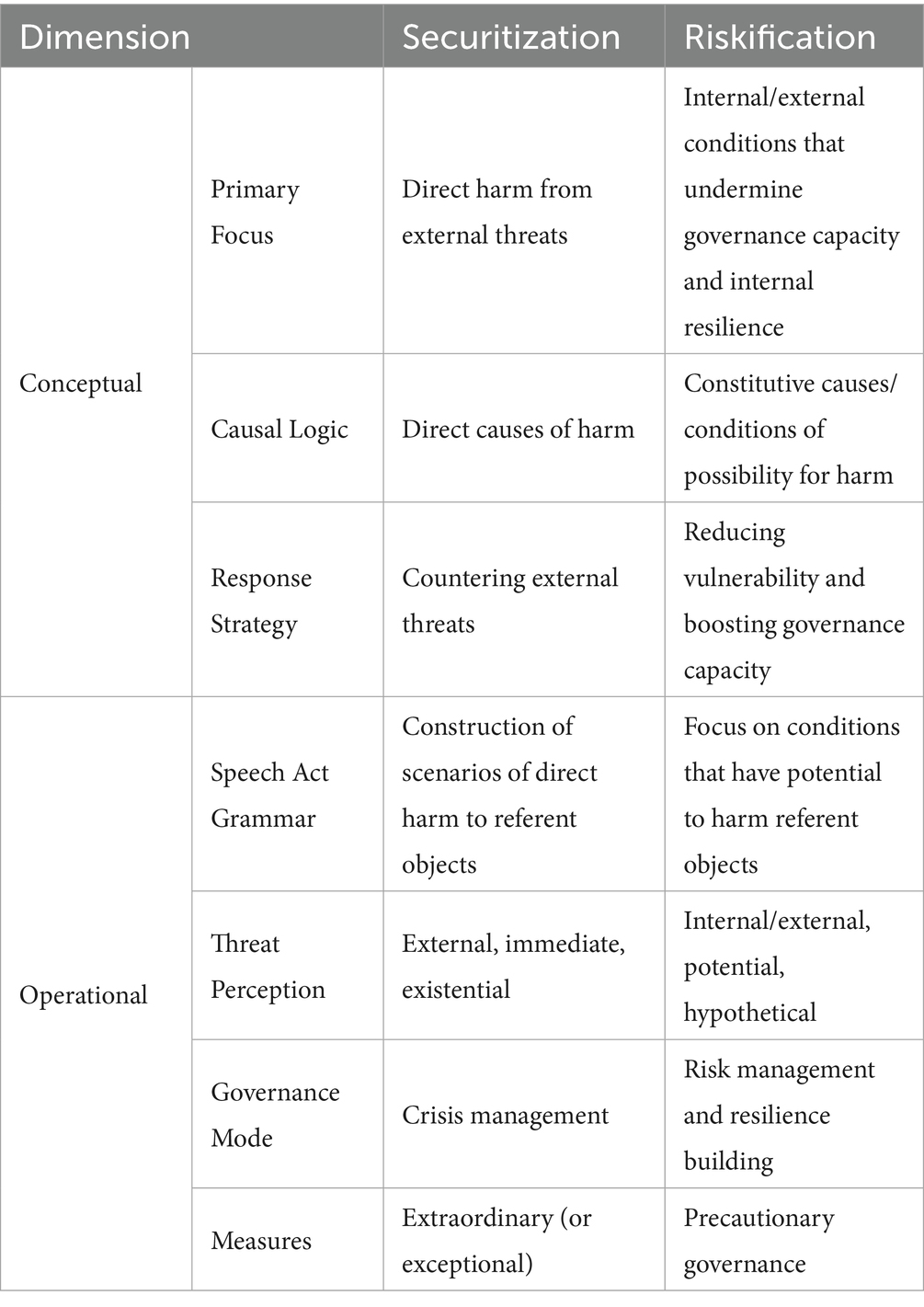

The need to distinguish between securitization and riskification emerges here. In the grammar of securitization, security actors construct a scenario of direct harm (presumably external) that can threaten a valued referent object. On the other hand, in the grammar of riskification, actors focus on conditions that have the potential to harm governance capacity and internal resilience. While securitization emphasizes the necessity of countering threats, riskification aims at “reducing vulnerability and boosting governance-capacity of the valued referent object itself” (Corry, 2012, p. 248). Indeed, in many cases, the seed of crisis emanates from within. Returning to the case of Afghanistan, the root cause of the Afghan Republic’s collapse was not the Taliban but rather the corrupt and authoritarian governance in Kabul, which eroded citizen trust (Murtazashvili, 2022). The Afghan Republic—whose referent object was to defend democracy—did not fall because its discourse lacked securitization against the Taliban. Instead, it failed to address or riskify its own governance shortcomings, or hamartia, and thus could not strengthen democratic resilience. Effective governance—characterized by the equitable distribution of political and economic resources throughout the state, fostering public confidence in democracy, and reinforcing the democratic rationale of government troops—should have been the outcome of a deliberate effort to address these risks (Table 1).

This analysis focuses mainly on the South Korean policymakers’ discourses for several reasons. First, South Korea is no doubt an integral player in the narrative of the North Korean nuclear threat. However much that North Korea perceives the United States as its principal enemy, it is South Korea—including policymakers and, especially, ordinary citizens—that would bear the brunt of the North’s attack, whether conventional or nuclear. This has become more evident after Kim Chŏngŭn declared the two hostile states doctrine in 2023, by which Pyŏngyang would no longer see Seoul as their compatriot. Second, Seoul and Washington’s threat perception cannot be compared in a balanced manner. South Korea and the US are staunch allies, and it is also true that Seoul counts on Washington for nuclear deterrence; however, because of the very fact that South Korea has neither wartime operational control nor nuclear deterrent capabilities, the alliance is inherently asymmetrical and, therefore, the security discourse on Pyŏngyang emanating from Seoul should be distinct from that of Washington. Third, and perhaps most importantly, given that Washington’s (or Western) narratives have dominated not only the international arena but also International Relations (IR) literature (Chagas-Bastos and Kristensen, 2025), the narratives originating from Seoul must be given greater attention when addressing the issue of the Korean nuclear crisis. That said, this should not be misunderstood as an exclusion of the US narrative or its context. When necessary, this analysis also incorporates narratives from the US side. Ultimately, the crisis discourse has largely been shaped by the combined narratives of Seoul and Washington. These narratives are inextricably interlinked, as each “exists in a fabric of relations” (Lyotard, 1984, p. 15). In this respect, this analysis serves as an important stepping stone for future research aiming to conduct a more comprehensive discourse analysis.

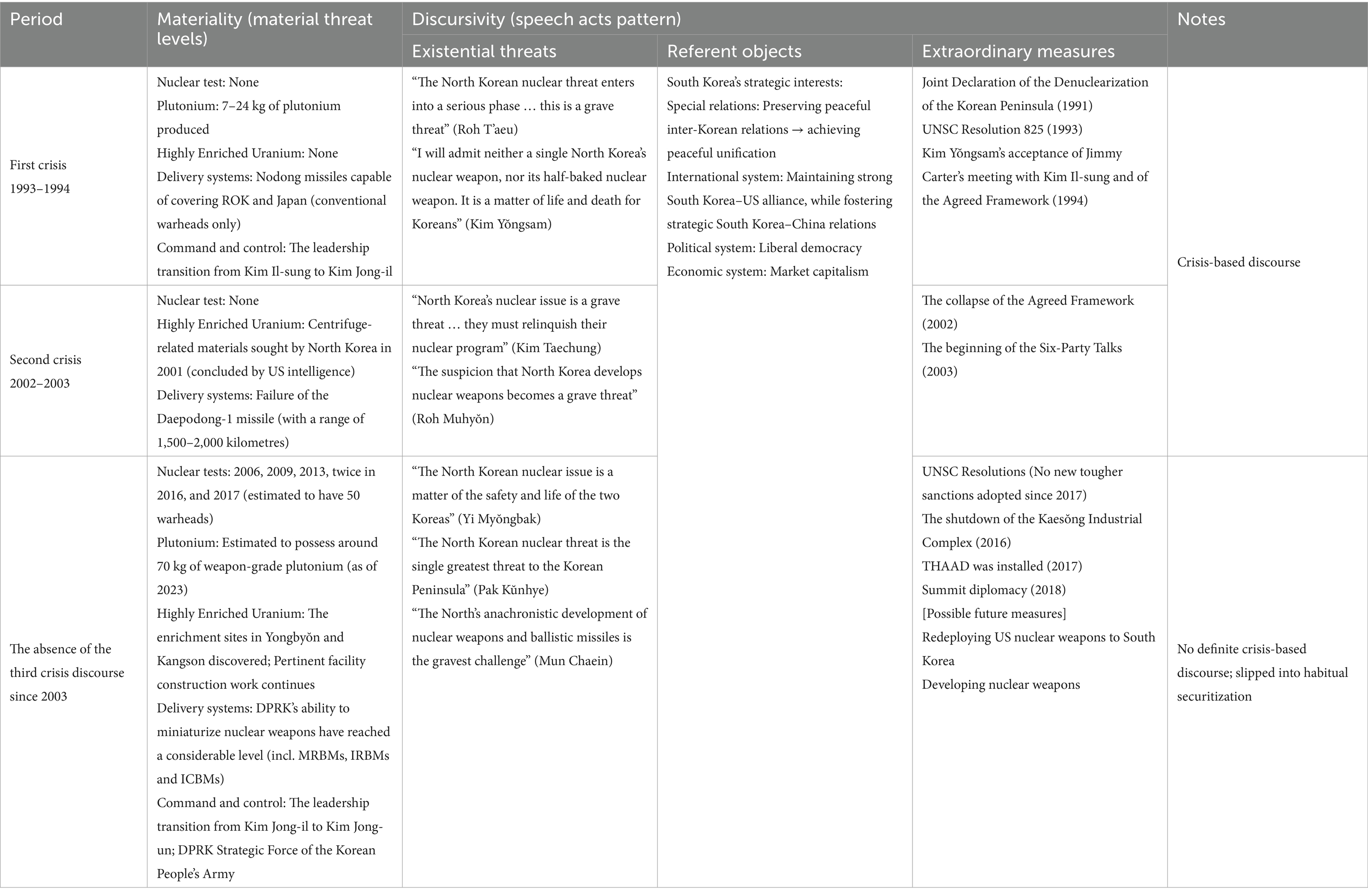

3 Securitization in practice: creating crisis

Given that the Korean nuclear crises have been extensively analyzed in previous studies (Bleiker, 2003; Lee, 2018; Moon, 2012; Pollack, 2011; Sigal, 1999; Wit et al., 2004), this section focuses more on the general patterns and characteristics of speech acts made by the principal securitizing actors, with speeches of the South Korean presidents being central to the process.2 In the realm of foreign and security policy, the role of South Korea’s presidents is difficult to overstate, so much so that Seoul’s security discourse on Pyŏngyang has been shaped by its presidents. Indeed, South Korea’s presidency has often been criticized as an imperial presidency (Ji, 2025). In that context, special attention is paid to the presidents’ articulations in their remarks, statements, and press conferences during their tenure. In the interest of intertextual analysis, the autobiographies written by pertinent actors and relevant media reports are also considered. The analysis is therefore a mapping of the main characteristics of the security actors’ speech acts, rather than a delineation of the crises in intricate detail. The timespan of the study ranges from Presidents Roh T’aeu to Yun Sŏgyŏl, during which period the South Korean security discourse on the North’s nuclear threat originated (the first nuclear crisis), developed (the second nuclear crisis), and stalled (the absence of a third nuclear crisis, i.e., perpetual securitization).

3.1 The first crisis (1993–1994)

The end of the Cold War and subsequent events, such as the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Seoul and Beijing, collectively engendered a heightened sense of vulnerability within North Korea. Meanwhile, Seoul found itself confronting a novel paradigm of security threat, with intelligence reports indicating that North Korea possessed a reprocessing facility in Yongbyŏn, capable of extracting weapons-grade plutonium from fuel (Oberdorfer and Carlin, 2013). Following the collapse of communism, suspicions regarding the North’s covert nuclear program began to escalate significantly. Despite North Korea being considered a threat for a prolonged period due to its bellicose image coupled with conventional weaponry, South Korea’s perspective on North Korea has been reshaped around the nuclear issue since the end of the Cold War.

The initial securitization of the nuclear issue took place during the Roh T’aeu administration (in office from 1988 to 1993). On 2 July 1991, during his meeting with then US President George H. W. Bush, Roh expressed deep concern, stating, “The North Korean nuclear threat has entered a serious phase. This poses a grave threat not only to the Korean Peninsula but also to Northeast Asia” (italics added). Roh’s apprehension about the nuclear threat was evident in his Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula (8 November 1991), where he asserted, “The North’s nuclear weapons development is a serious problem, entirely different from past issues.” In Roh’s speeches, the nuclear threat was considered existential and necessitated immediate and exceptional measures.

President Kim Yŏngsam’s (1993–1998) speech pattern was not significantly different from that of Roh. The nuclear issue was not definitively resolved during the Roh administration and persisted into the Kim administration. Kim (2001) personally recalled enduring anguish between March 1993 when Pyŏngyang declared its withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and October 1994 when Pyŏngyang and Washington reached the Agreed Framework. In this context, Kim Yŏngsam withheld all plans for economic cooperation with the North. In 1994, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA, 1998) “leaked its assessment that North Korea might have enough plutonium for one or two nuclear weapons” (Albright, 1994, p. 64). On 6 June 1994, during a meeting with journalists accompanying him to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, Kim stated “I will acknowledge neither a single North Korean nuclear weapon, nor its half-baked nuclear program. It is a matter of life and death for Koreans, and peace for the Korean Peninsula, Northeast Asia, and the world.”

Interestingly, during his presidency, Kim did not explicitly label the situation as a crisis. Later, in his memoir, he recalled the period as a crisis. It was the looming specter of a potential outbreak of the second Korean War, triggered by the US surgical strike on North Korea’s nuclear site, that left Kim uneasy and agitated. For Kim, the US plan of bombing Yongbyŏn posed an extremely perilous scenario. As part of his efforts, Kim summoned James T. Laney, then US ambassador to South Korea, and emphasized:

The South would be reduced to ashes by the North’s bombardment as soon as the United States bombs North Korea. Let me be clear. Never ever will there be war as long as I am in the presidency, […] The United States cannot wage war borrowing our land. (Kim, 2001, pp. 316–317)

However, Kim’s speeches flip-flopped as the negotiations between Pyŏngyang and Washington entered the final phase toward the Agreed Framework. In an interview with the New York Times in October 1994, Kim asserted, “We [South Korea] know North Korea better than anyone. […] the United States should not be led on by the manipulations of North Korea.” He further emphasized that “compromises might prolong the life of the North Korean government,” underscoring North Korea’s precarious state, and suggested that “time is on our [South Korea and the United States] side” (Sterngold, 1994).

Can this phenomenon-at-large be called a crisis? For Kim Yŏngsam, it was the actions of the United States that led to a real crisis. What is certain is that the US securitizing actors at that time, including influential political figures and media outlets, extensively referred to the North Korean issue as a crisis. Even as early as the 1990s, the New York Times reported that North Korea was only 4 or 5 years away from producing effective nuclear weapons (KBS, 1991). The Washington Post (Will, 1994; italics added) labeled Pyŏngyang’s nuclear ambitions “a decisive event for the 21st century,” citing former US senator and presidential candidate, John McCain, who referred to it as “the defining crisis of the post-Cold War period.” The analysis of the US discourse on the North Korean nuclear problem surely warrants further investigation, as Seoul’s security discourse has been closely linked to that of Washington.

3.2 The second crisis (2002–2003)

The administrations of Kim Taechung and Roh Muhyŏn (1998–2003 and 2003–2008, respectively) marked a period of both highs and lows in the context of the North Korean nuclear quandary. The first-ever inter-Korean summit was held during Kim’s tenure (June 2000), and the first Joint Statement addressing the nuclear issue was achieved (September 2005). However, these administrations also navigated the stormy waters of the so-called second nuclear crisis (2002–2003) and subsequently confronted North Korea’s inaugural nuclear test in October 2006.

For Kim Taechung, the political pressure surrounding the nuclear issue was relatively mitigated, largely due to the Agreed Framework. Though its implementation was gradual, the agreement between Pyŏngyang and Washington effectively froze and monitored North Korea’s plutonium-based program prior to the onset of the second nuclear crisis in late 2002. The five-megawatt reactor, capable of producing approximately seven kilograms of plutonium annually, remained suspended and subject to inspections. Furthermore, the construction of two larger reactors in Yongbyŏn and Taechŏn, with capacities of 50 and 200 electrical megawatts, respectively, was halted.

Within this context, James Kelly, then serving as US Assistant Secretary of State, made a significant announcement on 17 October 2002. He claimed to have presented “documentary evidence” to North Korean officials during his visit to Pyŏngyang earlier that month, and they had “confessed” to operating a highly enriched uranium (HEU) program. US officials accompanying Kelly reported that Kang Sŏkju, the North Korean Deputy Foreign Minister at the time, was assertive and even alluded to the existence of more powerful weapons. This perceived threat suddenly morphed into an existential one in the rhetoric of relevant securitizing actors. For instance, the CIA asserted that “North Korea likely could produce an atomic bomb through uranium enrichment in 2004” (Niksch, 2003, p. 1).

Kim Taechung’s language increasingly aligned with the discourse of securitization. He depicted the nuclear issue as an urgent and existential threat not only to the Korean Peninsula but to the entire East Asian region. As with Roh T’aeu and Kim Yŏngsam’s words, Kim Taechung called the North’s nuclear issue a grave threat in his address to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit held in Mexico on 27 October 2002. Kim then proposed three principles to tackle the nuclear issue: (1) South Korea can never condone the development of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) in the Korean Peninsula; (2) North Korea must relinquish their nuclear program; and (3) the nuclear issue must be resolved peacefully.

Upon assuming office in 2003, Roh Muhyŏn began securitizing North Korea in his speeches on the nuclear issue (Roh, 2003a, 2003b). During his tenure, Roh often referred to the North Korean nuclear problem as nothing short of a grave crisis (Yoon, 2019). Yet, with the benefit of hindsight, it becomes evident that the second crisis fell short of being genuinely classified as a crisis. Just as the first crisis emerged due to suspicions surrounding North Korea’s hidden nuclear materials, the core of the second crisis was driven by concerns that “North Korea may have hidden some nuclear materials from inspectors before the verification measures of Agreed Framework” (Gill, 2002; italics added).

Perhaps, then, Roh, whether consciously or not, was effectively in a “pre-crisis phase that takes the form of an incubation period that is difficult to interpret and during which ill-defined problems are difficult to see” (Roux-Dufort, 2007, p. 111), rather than in a full-blown crisis phase. Concurrently, however, akin to the precedent set by Kim Yŏngsam, Roh also pursued the securitization of the plausible eventuality of a US offensive against North Korea. This act of securitizing the United States was a significant issue, as it could be seen as a move jeopardizing the US–South Korea alliance. Roh was deeply concerned about the possibilities of such an attack. Lee Jong-sŏk, former Unification Minister and Chief of the National Security Council under the Roh administration, confirmed that Roh believed the United States might attack North Korea (Bush, 2010; Cheney et al., 2011; Lee, 2014).

Nevertheless, it is important to note that Roh’s securitization against the Bush administration bore no implication of desecuritization of the North Korean nuclear issue. Desecuritizing moves would have entailed scant perception of nuclear threats, minimal articulation of relevant referent objects, and paucity of extraordinary measures. However, all the core components of securitization were present in Roh (2003b, 2006) speeches, all revolving around the North’s nuclear threat.

On a positive note, the aftermath of the second crisis led to a tangible outcome during Roh’s tenure: the September 19 Joint Statement in 2005. This Joint Statement was a major result of the Six-Party Talks, a series of multilateral negotiations held between 2003 and 2008 involving South and North Korea, China, Russia, Japan, and the United States. The main contents of the statement included verifiable denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula in a peaceful manner, normalization of the United States–North Korea relationship, and negotiating a permanent peace regime on the Korean Peninsula. Despite this achievement, the implementation of the agreement was contingent on the willingness of Pyŏngyang, Seoul and Washington to engage. More to the point, the Joint Statement was only the beginning of resolving the nuclear problem, and the crisis-driven discourse per se was not sufficient to guarantee a smooth implementation process.

3.3 After the second crisis: the absence of the third crisis discourse in perpetual securitization

From the realm of policy discourse emerges a question about the notion of the elusive third Korean nuclear crisis. Surprisingly, to date, no unequivocal consensus has been reached regarding its existence or the precise juncture of its occurrence. Some voices within academic circles contend that the third crisis unfolded during North Korea’s second nuclear test in 2009 (KNSI, 2009). Lee (2023) argued that the third crisis has existed since December 2008, when the last round of the Six-Party Talks halted. Another viewpoint suggests a period of heightened tension between the United States and North Korea in 2017 (INSS, 2017; Lee, 2018). During this time, former President Donald Trump tweeted a provocative warning to Pyŏngyang, stating they would be “met with fire and fury.” Trump also mentioned that his “Nuclear Button [&] is a much bigger & more powerful one.” than Kim Chŏngŭn’s, prompting a derisive response from North Korea, who labeled him “the spasm of a lunatic” (Al Jazeera, 2019).

However, this leaves us in a conundrum, with academics and policymakers failing to agree on a specific period for anointing as the third (or subsequent) crisis. Beyond the elusive categorization lies another revelation. As the second nuclear crisis discourse waned, the discursive structure of the nuclear crisis had already become habitual (or institutionalized). As French philosopher François Jullien pointed out, “the notion of event is intrinsically related to the idea of time … we would have no consciousness of time without the events that punctuate it” (cited in Roux-Dufort, 2007, p. 109). This notion prompts us to reassess the discourse on the North Korean nuclear crisis. Truly significant events related to the nuclear threat posed by North Korea, such as conducting physical nuclear tests and launching solid-fueled ballistic missiles, have actually occurred long after the end of the second crisis period.

During both the first and second crises, North Korea was rather on the defensive, showing reluctance to fully cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the US on technical and intelligence matters. However, after the collapse of the Agreed Framework, which was caused by the second nuclear crisis discourse, North Korea’s nuclear discourse became notably emboldened and assertive. As mentioned, North Korea “quickly breached red lines in US policy” by reactivating “its long-suspended plutonium program” (Pollack, 2011, p. 132).

A cascade of materially threatening events followed. Pyŏngyang declared itself as a nuclear state in 2005, and conducted its first nuclear test the following year. After a brief hiatus between 2007 and 2008, the North more “forcefully expanded its claims to standing as a nuclear-weapons state” (Pollack, 2011, p. 157). In 2012, the revision of their constitution served as a reaffirmation of their nuclear-armed status. Since their proclamation of the Byŏngjin policy in 2013, aiming to develop nuclear capability alongside the economy, North Korea’s nuclear displays have consistently increased and expanded. In addition to the thermonuclear weapon test in 2017, it has tested advanced ballistic missiles with various ranges and hypersonic missiles. In 2022, it passed a law officially declaring itself a nuclear weapons state, and in 2024, it signed a comprehensive strategic partnership treaty with Russia, committing to strengthened military ties.

Where, then, does the third crisis discourse lie? Have the subsequent South Korean presidents (Yi Myŏngbak, Pak Kŭnhye, Mun Chaein, and Yun Sŏgyŏl) failed to articulate threats with the same gravity as their predecessors? The answer is unequivocally no. For instance, during his presidency from 2008 to 2013, Yi Myŏngbak pursued the ambitious goal of achieving complete securitization of the nuclear issue (Lee, 2009a, 2009b). He implemented extraordinary measures in the form of his flagship policies, known as Vision 3,000: Denuclearization and Openness. However, paradoxically, after the Chŏnan and Yŏnpyŏng incidents in 2010, Yi’s focus shifted toward seeking apologies from Pyŏngyang (Snyder and Byun, 2011). Consequently, the once-urgent nuclear issue took a backseat on the priority list for a significant period. Yi later remarked, “We came to a realization that it no longer makes sense for us to anticipate that the North would abandon its nuclear program” (Lee, 2010).

Yi’s consternation turned into a boycott on resuming the Six-Party Talks, the apparatus of diplomacy on which he himself placed an emphasis in order to realize Pyŏngyang’s denuclearisation. Yi also turned his eyes to a more distant (and ambiguous) future of unification by proposing a unification tax in a rather abrupt manner (Oliver, 2010). This proposal seemed to have little to do with the impending and existential nuclear threat posed by North Korea. Ironically, the absence of the third nuclear crisis discourse during Yi’s era led him to be somewhat distracted from fully contemplating the gravity of the North’s nuclear threat.

Albeit demonstrating somewhat different manners, the same logic applies to Yi’s successor, Pak Kŭnhye (2013–2017). Despite Pyŏngyang’s third nuclear test in February 2013, less than a month before her inauguration, Pak emphasized the concept of trust as the central pillar of her securitizing moves regarding the nuclear issue. However, in her words, trust seemed to be something that should be considered more like a by-product of the North’s denuclearization, rather than a precondition for eliciting denuclearization. For example, in her Dresden speech on 28 March 2014, Pak addressed that “North Korea must choose the path to denuclearization so we can embark without delay on the work that needs to be done for a unified Korean Peninsula.” She defined the nuclear threat as the “single-greatest threat to peace on the Korean Peninsula and in Northeast Asia” (italics added).

Indeed, Pak’s position on practicing trustpolitik underwent a significant change, as her extraordinary measures culminated in the closure of the Kaesŏng Industrial Complex in February 2016, a month after North Korea conducted its fourth nuclear test. The decision was based on an unconfirmed story suggesting that wages for North Korean workers in the complex were being diverted to upgrade Pyŏngyang’s nuclear weapons (Wyeth, 2020). In stark contrast to Seoul’s expectations, however, North Korea aggressively tested a series of ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons during the remaining 2 years of Pak’s tenure. Meanwhile, the core pattern of security discourse on the nuclear threat posed by the North remained largely unchanged; i.e. “Completely abandon your nuclear weapons that pose a grave threat to the world, otherwise, you’ll be isolated continually.”

In 2017, North Korea’s nuclear threat reached another critical juncture. Following the fourth and fifth nuclear tests in the preceding year, the North conducted its sixth nuclear test, releasing an estimated minimum of 140 kilotons of energy. The test, claimed by Pyŏngyang to be a hydrogen bomb, was later confirmed by international scientists (Lester, 2019). This was not universally recognized as a third crisis, despite some referring to it as such, as mentioned earlier. After Pak’s impeachment in 2017, Mun Chaein (2017–2022) passionately attempted to broker a deal between Kim Chŏngŭn and Donald J. Trump while securitizing the nuclear threat from North Korea. The three inter-Korean summits and the historic North Korea–US Singapore summit in 2018 were the tangible results of these efforts. However, similar to the situation in 2005 with the September 19 Joint Statement, both the inter-Korean Panmunjom Declaration and the Joint Statement between North Korea and the US eventually stalled due to differing views on implementation.

Amidst these developments, rather than explicitly highlighting the nuclear threats posed by North Korea, Trump’s statement underscored the equivocal nature of the discourse surrounding the Korean nuclear crisis. This shifted from warnings like “[North Korea] will be met with fire and fury” to the assertion that “there is no longer a nuclear threat from North Korea” (Reuters, 2018). Furthermore, even when Pyŏngyang resumed launching ballistic missiles prohibited by United Nations Security Council resolutions, Trump dismissed them as “some small weapons, which disturbed some of my people, and others, but not me” (Trump, 2019).

A similar change in tone was apparent in statements by Mun. When North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test and launched intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), Mun (2017; italics added) called it an “utterly absurd and strategic blunder,” further asserting that “our government will ensure that North Korea has no choice but to abandon its nuclear weapons and missile programs in a verifiable and irreversible manner.” However, when the IAEA chief stated in 2021 that North Korea’s nuclear program was going “full steam ahead,” the official response from Mun’s administration was simply, “[We] have no specific position on it” (Lim, 2021). Neither a sense of urgency nor extraordinary measures were evident in the statements of the latter half of his presidency.

The discourse surrounding the nuclear threat has remained the same during the Yun Sŏgyŏl government. Notably, Yun floated the idea of South Korea possessing nuclear weapons (Choe, 2023). If that happens, it would be a paradigm shift for South Korea’s policy in terms of setting an extraordinary measure against the North. However, it is essential to recognize that this idea did not emerge in isolation but rather as part of a bargaining strategy, as evidenced by the subsequent Washington Declaration in 2023 reaffirming the US commitment to extended deterrence for South Korea. The same goes for the US-ROK Nuclear Consultative Group (since 2023) and the US-ROK Guidelines for Nuclear Deterrence and Nuclear Operations (since 2024). The basic logic of these measures declared by Seoul and Washington is essentially the same: extended nuclear deterrence or, in other words, the nuclear umbrella. In addition, although claims advocating for Seoul to acquire nuclear weapons have slowly transitioned from the political fringes to the mainstream political space, South Korea recognizes the considerable difficulties in pursuing such a path (Lind and Press, 2023).

The crux of the matter here lies not in the weakening perception of the threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear weapons. Rather, it is the habitual securitization of the North Korean nuclear issue that has led to its institutionalized measures—measures that are difficult to refer to as extraordinary—without sufficient time for introspection on the existential nature of the nuclear threat. As a result, the articulation of the threat by various actors has become relatively locutionary, detached from its original function or purpose, and consequently distanced from being perlocutionary, which would involve problem-solving discourse. This situation has led to a shift in focus from devising efficient and effective measures to more ambiguous and less practical actions and concepts. While a certain level of securitizing moves has continued in South Korea, the North has unabashedly expanded its nuclear capabilities (Table 2).

4 Rewriting the crisis: protracted threat and obscured measures

Regarding the first crisis, the security actors’ discourse was driven by the incomplete disclosure of North Korea’s reprocessed amounts of plutonium in 1992, leading them to emphasize the urgency of the situation. However, the crisis-oriented discourse could have been less enunciated considering the actual material level of the nuclear threat posed by North Korea during that period. As Pollack (2019) highlighted, the reactor at Yongbyŏn “was the country’s sole avenue for producing meaningful amounts of fissile material.” Given that Pyŏngyang’s main goal at the time was to “cultivate foreign suspicions that they had enough fissile material on hand to be dangerous” (Pollack, 2019), what was necessary instead was to construct a more level-headed and dispassionate discourse which was tight enough to monitor the Yongbyŏn area.

This is an interesting point because, during the second Trump–Kim summit in Hanoi in 2019, North Korea demonstrated its willingness to dismantle the nuclear facilities in Yongbyŏn. Surprisingly, the US refused to accept that offer, insisting that Pyŏngyang must also disclose other related facilities beyond Yongbyŏn. This was very ironic in that Yongbyŏn has been at the core of all the Korean nuclear crises. Three years later, in 2022, Rafael Grossi, the chief of the IAEA, mentioned that “the reported centrifuge enrichment facility at Yongbyŏn continues to operate and is now externally complete, expanding the building’s available floor space by approximately one-third” (Kim, 2022).

This raises another question: If a relatively small amount of plutonium allegedly produced by Pyŏngyang with a modest nuclear capability created such urgency and a crisis in the early 1990s, why was it no longer considered a crisis in 2019, even as Pyŏngyang increased the level of fissile materials and enhanced nuclear facilities in Yongbyŏn? Despite the possibility of North Korea having established additional nuclear facilities beyond Yongbyŏn by 2019, should not North Korea’s facilities and capacity for producing weapons-grade plutonium, HEU, and tritium, used in making hydrogen bombs, have been thoroughly examined? The UK think tank International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) concluded that:

Dismantling all Yongbyŏn facilities, as discussed at the Hanoi summit in February 2019, would significantly reduce Pyŏngyang’s capability to make weapons-usable fissile materials. If only one other enrichment plant is operational, then eliminating the Yongbyŏn facilities would reduce North Korea’s weapons-production capacity by up to 80%. (IISS, 2021, p. 7)

While the nuclear issue should always be treated as a security concern, it does not necessarily demand an immediate sense of urgency. In the context of crisis clarification, Svensson (1986, p. 134) pointed out that “one must first specify which kind of object has come to a crisis, and secondly specify how this political object has been challenged.” He continued:

It is not reasonable to speak of a crisis whenever a political object faces problems, new problems or even severe problems. Nor is it reasonable to speak of a crisis whenever a political object undergoes changes, sudden changes or even extensive changes. Only the combination of challenges that could lead to the breakdown of the object or to structural changes of a fundamental character constitutes a crisis.

For Seoul, a pivotal referent object rested in the preservation of its regime and the unwavering safeguarding of their people, firmly rooted in the bedrock of their cherished ideologies—liberal democracy and market economy. Yet, did these valued objects confront challenges that could shatter their foundational stability? Obviously not. As the so-called first North Korean nuclear crisis discourse emerged amidst the collapse of the communist bloc, it was North Korea that grappled with existential crisis at that juncture. The weighty conundrum faced by Pyŏngyang hinged upon the precarious balance between sustaining regime stability and navigating the uncertainties that loomed large (Wampler, 2017).

The collapse of the Agreed Framework, intertwined with the second crisis in late 2002, ostensibly resulted from Pyŏngyang’s covert HEU program. However, the authenticity of this program was too ambiguous at the time to be verifiable and too underdeveloped to pose intense difficulty or danger. In other words, hastily pursuing the second crisis discourse based on uncertain and remote dangers (the presumed HEU program) while risking the breakdown of the Agreed Framework, which had successfully controlled a more tangible threat (plutonium-based nuclear weapons program), might not have been reasonable under the circumstances. Nonetheless, the event ultimately acquired the title of crisis in widely accepted international security discourse.

Why, then, was there an absence of discourse for a third nuclear crisis despite the increased material level of the threat posed by North Korea? At least three components can be inferred from the analysis above in terms of the crisis-securitization nexus within the context of the Korean nuclear issue: ontological, discursive, and theoretical.

First, from an ontological viewpoint, North Korea’s nuclear ambition in and of itself constitutes an existential threat to South Korea. For Seoul, North Korea is no more than a political entity which illegally occupies the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. Therefore, the existence of the North itself poses a threat. It should be noted that regardless of the nuclear weapons, the South Korean perception of North Korea has always been deeply ingrained in the concept of security. It is in this respect that the term nuclear crisis was accepted in a wider Korean society in a natural or inadvertent manner.

The psychological and ideological chasm between the two Koreas was etched into the collective memory through the scars of the Korean War. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, South Korea faced a surge in North Korean provocations, including the Panmunjŏm Axe Murder Incident, the assassination of the South Korean first lady, Yuk Yŏngsu, and the discovery of infiltration tunnels under the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), among others. The Chŏn Tuhwan administration (1980–1988) witnessed a deepening phase of the Cold War in the 1980s. During this period, Pyŏngyang attempted to assassinate Chŏn at the Martyrs’ Mausoleum in Yangon (Rangoon), Myanmar. In 1987, KAL 858, en route from Abu Dhabi to Seoul, was tragically destroyed in mid-air after two highly-trained North Korean espionage agents planted a powerful bomb on board. In short, the threat from the North was indeed existential.

Given this track record, the mere thought of a nuclear-armed North Korea is deeply frightening to most South Koreans. The perception of the nuclear threat from the North, in a sense, is merely an extension of the already embedded threat perception. It is, therefore, understandable to consider that the nuclear issues were securitized from the very beginning. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that the habitual securitization of the nuclear issue over the last three decades has been neither effective nor conducive to problem-solving discourse. In this process, the South’s “feelings of fear were displaced by feelings of fatigue [caused by the nuclear crises discourse and subsequent securitizing moves]” (Rythoven, 2015, p. 468).3

Second, from a discursive viewpoint, the repetitive incantations of denuclearization unwittingly ushered us into the realm of the new normal, referring to Pyŏngyang nearly completing its nuclear weapons program while still not being officially recognized as a nuclear power. In other words, “the North is on a glide path toward acceptance as a de facto non-NPT nuclear power like Pakistan” (Russel, 2019). While Seoul and Washington have preserved the main discourse on the North Korean nuclear issue, complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization (CVID), Pyŏngyang has enhanced their knowledge and technology regarding nuclear weapons and, therefore, the future process of denuclearization—inspection, verification, dismantlement, final disposition of nuclear materials, etc.—becomes much more complex and improbable. In short, according to the current discursive track, North Korea can never be a nuclear weapons state on one hand, and on the other, it is a de facto nuclear state.

The new normal discourse raises questions about the practical efficacy of securitization. Did the hastily made securitizing moves (referring to North Korea’s nuclear ambition as a crisis) contribute to the normalization of nuclear North Korea? If we are lenient enough to describe the current situation—North Korea as a de facto nuclear country—as the new normal (and no longer call it a crisis), did the events of 1993 and 2002 truly merit being labeled as crises in the first place? Why did security actors not attempt to address the North Korean nuclear issue (when its level of threat was significantly lower compared to the present time) during the two crises by using a more objective and unpretentious discourse instead of labeling it as a nuclear crisis? In this regard, the new normal discourse is not only misleading but also deceptive.

Alternatively, one might posit that persistent securitization—despite its inflationary logic—can provide a degree of deterrence or stabilization. This view is contentious because securitization is originally conceived to address immediate and present threats (Buzan et al., 1998; Wæver, 1995); by design, it is not meant to be sustained indefinitely. The U.S.-led intervention in the first Gulf War (1990) and NATO’s campaign in Kosovo (1999) serve as illustrative cases: the Hussein regime was expelled from Kuwait, and Yugoslav forces withdrew from Kosovo, preventing further atrocities. The conceptual ambivalence of securitization is perhaps best encapsulated in the Independent International Commission on Kosovo’s assessment that NATO’s bombing was “illegal but justified.” However, when securitization becomes unnecessarily prolonged, it often loses either its perfunctory urgency or its material preparedness. This was evident in the second Gulf War and the war in Afghanistan that ended in 2021. As noted earlier, the Korean case reflects similar dynamics. The consequences of inflated and extended securitization have included the rise of the Islamic State (ISIL), the reinstatement of the Taliban regime, and North Korea’s emergence as a de facto nuclear state (Ministry of National Defense, 2023). In the latter three cases, the key to deterring external threats lies not in the persistence of securitized rhetoric, but in the enhancement of resilience within both political and security institutions.

Third, from an IR theoretical standpoint, it is fair to say that the crisis-driven discourse of the Korean nuclear issue was mainly influenced by the so-called problem-solving theories. Notably, the realist tradition, whether classical, structural, or neoclassical, has had a profound impact on shaping security discourse concerning Pyŏngyang’s nuclear threat (Klingner, 2018; Park and Kim, 2012; Terry, 2013; to name a few). However, from predicting North Korea’s collapse to formulating theories of reunification, the description of IR realism has proven to be inaccurate. In the 1990s, during the first crisis, observers of Pyŏngyang insisted that the demise of the regime would occur in the not too distant future. A CIA intelligence report (1998, p. 4) even predicted the likely dissolution of Pyŏngyang’s regime within 5 years. The erroneous prediction from the realist viewpoint persisted throughout the 2000s and 2010s (Bush, 2010; Kaplan, 2006; Lankov, 2011; Rice, 2011).

Liberalism and constructivism are not the exceptions to the trend of securitization discourse. Both were not discerning enough in that IR liberals and constructivists accepted the reality wherein Pyŏngyang’s nuclear program is naturally seen as constituting crises. Despite them having strived to contrive a different approach to North Korea in solving the nuclear issue, whether it be reconciliation or cooperation, their way of seeing the North Korean nuclear issue was fundamentally bounded by the way IR realists defined it (Moon, 2012; Moore, 2008; Nah, 2013). As noted, even progressive policymakers of South Korea, such as Kim Taejung, Roh Muhyŏn, and Mun Chaein, were not able to break out of the crises-based discourse.

In summary, the theoretical accounts of the Korean nuclear issue have remained more static than realistic. The continued emphasis on reiterating North Korea’s nuclear threat has overshadowed critical “questions about the long-term future of human society” on the peninsula (Booth, 2005, p. 6), resulting in a myopic discourse on nuclear crises.4 As a consequence, important human rights issues, such as the fate of families separated by the Korean War for over 70 years, have been sidelined. Likewise, the rights of North Korean defectors and individuals abducted by the North Korean regime from South Korea or Japan have received little attention. In this regard, discourses centered solely on nuclear weapons and crises are unlikely to bring about structural change.

Certainly, the Korean nuclear issue presents a more complex case where the line between riskification and securitization becomes blurred. As mentioned earlier, North Korea-related issues had already been securitized even before the nuclear issue surfaced. From a South Korean perspective, since North Korea is not so much an equal state as an illegitimate political entity, any issues concerning North Korea, be they security issues or not, are more likely to be securitized. Desecuritization (a reverse process of securitization) becomes nearly impossible in this context. As Donnelly (2013, p. 49) opined, however, when security discourse becomes a norm rather than an exception, the lines between politicization and securitization become more blurred.5

As such, reflecting on the past 30 years of securitization of the nuclear threat is crucial. Particularly concerning the nuclear threat, as discussed, it is fair to say that North Korea’s nuclear capabilities did not reach the level of posing a direct harm during the time of the first two crises. Hence, it is also safe to say that there was room for South Korean securitizing actors to formulate a more pragmatic security discourse utilizing the grammar of riskification instead of securitization. For example, given the polarized political situation and the unnecessarily competitive culture between departments, such as the National Intelligence Service, Ministry of Unification, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, National Police Agency, and Supreme Prosecutors’ Office, the South Korean securitizing actors could have paid greater attention to creating a more consistent and effective policy toward Pyŏngyang rather than (re-)producing a crisis discourse.

5 Conclusion: the future of crisis discourse

Contemplating the two concepts—crisis and securitization—provides valuable insights for analyzing the Korean nuclear issue. First, it allows for a reflexive approach in examining the Korean nuclear crisis, where the term crisis has been casually (or unwittingly) used. Put differently, while we may appear to be living in an era of crisis management, we are, paradoxically, living in an era where genuine crisis discourse is absent. Perhaps more accurately, we have long been at a crossroads of misplaced securitization. Second, this approach facilitates an analysis that is relatively free from ideological divisions. Regardless of whether the South Korean securitizing actors are conservatives or liberals, it was revealed that they have fallen into the trap of either crisis-based discourse or securitization which, in turn, has led to hastily made measures doomed to be inconsistent and short-lived. Last but not least, it illuminates the permissive causes underlying the protracted discourse on the North Korean nuclear threat, as it highlights the boundary issues between crisis and non-crisis, as well as between securitization and politicization (or riskification). In so doing, this analysis aims not only to construct a fresh conceptual framework that can better analyze the crisis discourse, but also to contribute to the overall literature on securitization theory by suggesting a more informed direction for future securitization efforts, which should not be limited to the case on the Korean Peninsula.

Where should we go from here? In the midst of habitual securitization, what is the point of calling an event a crisis? The lessons learned from the crisis discourses in the 1990s and 2000s should serve as a cautionary tale, reminding us of the importance of measured and rational security discourse. North Korea has been cognizant that launching a nuclear attack or taking recklessly escalatory actions would be suicidal. This understanding persists, and both Seoul and Washington share this conviction (AFP, 2023; Persio, 2018; Yoo, 2024). Perhaps, then, a promising starting point to rectify the distorted security discourse could be reached by acknowledging that the securitization process over the last three decades has been hastily triggered. Labelling events that could have been managed with less securitization as crises has led to a repetitive cycle of securitization. As Pyŏngyang has made progress in its nuclear capabilities, the international community’s call for denuclearization of North Korea has seemingly become a hollow mantra (i.e., habitual securitization).

There are forthcoming events that may potentially punctuate our collective consciousness, thereby necessitating a more cautious formulation of the crisis discourse. Two such scenarios loom on the horizon. First, North Korea’s prospective additional nuclear tests are likely to unveil Pyŏngyang’s bolstered nuclear capacity, with amplified explosive power. This will inevitably trigger consternation and strident calls for sanctions. However, the geopolitical landscape remains complex, as North Korea, aligned with Russia and China, casts blame on Seoul and Washington for their justifiable policies. Thus, pursuing a unified and robust sanction becomes a more formidable challenge. In addition, the aberration of Trump’s approach to Pyŏngyang is another main variable that can make the securitization process more complicated. Amidst such intricate circumstances, the efficacy of the crisis discourse may be called into question once again.

Second, South Korea’s potential decision to equip itself with nuclear weapons could prove to be a game-changing move. While delving into the intricacies of this event is beyond the scope of this study, if Seoul were to declare its withdrawal from the NPT, it would undoubtedly trigger an overwhelming surge of crisis discourse—this time, targeting the South, not the North. This transformation would reshape the well-worn crisis discourse centered around the North Korean nuclear program into a renewed focus on the global implications of such a declaration: potential repercussions on the NPT regime, with the risk of other East Asian nations like Japan and Taiwan following suit, further encroachment on US security guarantees in the region, and more (Lind and Press, 2023; Mohan, 2023).

Neither scenario is problem-solvable nor desirable. Both will exacerbate the already crisis-embedded situation (and this will desensitize us all the more to the real existential threat posed by nuclear weapons). The future path that needs to be focused on is then clear. The policymakers’ security discourse should sublate, if not totally eliminate, the easy way to securitize the potential threat. Finding a manageable way of dealing with the nuclear issue in the realm of riskification is de rigueur.6 The whole peninsula would be highly likely to be devastated and “a return to the pre-nuclear war state would not be possible” (Yoon, 2019) if nuclear weapons are used.

How can the current reliance on securitization be disrupted? There is no simple answer, but historical institutionalists have demonstrated that path dependence can shift through external shocks (like war or regime collapse), changes in leadership and ideas, or gradual institutional evolution. Recent events—the largest European war since World War II between Russia and Ukraine, the rise of Trumpist unilateralism, and the symbolic alignment of Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and Kim Jong-un in Beijing in September 2025—may signal such a turning point. This analysis, however, does not predict which events might serve as sufficient triggers to break path-dependent trajectories. Future research on this question would be highly valuable.

To reiterate, this analysis does not require that securitizing actors cease to pay attention to securitizing nuclear issues. Rather, it argues for a more balanced construction of the securitization (and riskification) process through nuanced security discourses. The analysis sheds light on the reasons behind the absence of effective and dependable measures against the nuclear threat posed by North Korea, viewed through the lenses of crisis and securitization. In doing so, it underscores the imperative of formulating and implementing pragmatic security discourse, grounded in a risk-based approach to the nuclear issue, rather than pursuing an ambitious discourse that dismisses potential political middle grounds (e.g., the abject rejection of the North Korean regime or the underestimation of the existence of Pyŏngyang–Beijing–Moscow cooperation).

This article also offers an improved framework to facilitate a more precise analysis and lays the groundwork for future research endeavors. For example, it raises essential questions such as: How can we break free from habitual securitization? How do we distinguish non-crisis, risk, and crisis situations within the realm of security studies, especially in nuclear security where tactical nuclear weapons continue to evolve with the rising concept of the grey zone, so as to prevent an inflated level of securitization?

Within this context, securitizing actors should be wary of creating self-replicating security discourse, which tends to deprive them of reasonable spaces for critical thought in practicing security policies. As a process, the forging of securitizing moves is not inherently difficult. What is challenging is resisting the temptation to make hasty securitizing moves and constructing security discourse in an unpretentious manner while keeping sight of the real existentiality of a threat. The securitization dynamics observed during the Korean nuclear crises carry relevance beyond the peninsula, yet they also need to be understood in the specific context of South Korea’s national identity.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: http://pa.go.kr/research/contents/speech/index.jsp.

Author contributions

SY: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2023S1A5A8076707).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Ironically, however, this outcome can also be a result of habitual securitization. The existence of both the Taliban and Hamas was so habitually securitized that the US and Israeli governments could not manage the threats in a timely and appropriate manner when the actual strike from the others occurred.

2. ^Presidential speeches quoted in this article are from the official electronic presidential archives, available at http://pa.go.kr/research/contents/speech/index.jsp.

3. ^According to the latest survey conducted by Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU, 2024), North Korea’s nuclear threat and its assertion of a hostile two-state narrative have had minimal impact on South Korean public opinion. For many South Koreans, the nuclear threat has become a normalized issue, while interest in unification continues to decline.

4. ^This argument is in line with the views of critical security theorists. A defining feature of critical security studies is its broadening and deepening of the security agenda. Security is no longer seen as synonymous with defense. Instead, a broadened and deepened understanding of security adopts a more historical and structural mode of thinking.

5. ^It should be noted that riskification is not synonymous with desecuritization. As Figure 1 highlights, riskification falls somewhere between securitization and politicization. While desecuritization means removing a specific issue from the security agenda, riskification connotes a more nuanced and flexible process that depends on internal or external conditions.

6. ^At the time of writing, North Korea is once again tightening its border and going backwards to its reclusive life with its pursuit of nuclear weapons unabated. Nevertheless, our strength comes from democracy and its resilience. We do not need to keep holding idées fixes that North Korea would not budge or would never give up their nuclear weapons.

References

Albright, D. (1994). North Korean plutonium production. Sci. Global Security 5, 63–87. doi: 10.1080/08929889408426416

Al, Jazeera (2019). Trump and Kim in quotes: From bitter rivalry to unlikely bromance. Doha: Al Jazeera.

Bleiker, R. (2003). A rogue is a rogue is a rogue: US foreign policy and the Korean nuclear crisis. Int. Aff. 79, 719–737. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.00333

Booth, K., and Wheeler, N. J. (2013). “Uncertainty” in Security studies: An introduction. ed. P. D. Williams (Oxon: Routledge), 137–154.

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., and Wilde, J. D. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Chagas-Bastos, F. H., and Kristensen, P. M. (2025). Mapping quality judgment in international relations: cognitive dimensions and sociological correlates. Perspectives on Politics. doi: 10.1017/S1537592724002676

Cheney, R. B., Cheney, D., and Cheney, L. (2011). In my time: A personal and political memoir. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Choe, S. (2023). In a first, South Korea declares nuclear weapons a policy option. New York, NY: The New York Times.

CIA (1998). Exploring the implications of alternative north Korean endgames: Results for a discussion panel on continuing coexistence between north and South Korea. CIA Intelligence Report. Available online at: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/18238-national-security-archive-doc-19-cia (accessed July 19, 2023).

Corry, O. (2012). Securitisation and ‘riskification’: Second-order security and the politics of climate change. Millennium J. Int. Stud. 40, 235–258. doi: 10.1177/0305829811419444

Donnelly, F. (2013). Securitization and the Iraq war: The rules of engagement in world politics. Oxon: Routledge.

Eastham, K., Coates, D., and Allodi, F. (1970). The concept of crisis. Can. Psychiatr. Assoc. J. 15, 463–472. doi: 10.1177/070674377001500508

Emmers, R. (2013). “Securitization” in Contemporary security studies. ed. A. Collins (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 168–181.

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Oxon: Routledge.

Hermann, C. F. (1969). “International crisis as a situational variable” in International politics and foreign policy: A reader in research and theory. ed. J. M. Rosenau (New York, NY: The Free Press), 409–421.

IISS (2021). DPRK strategic capabilities and security on the Korean peninsula: Looking ahead. London: International Institute for Strategic Studies.

INSS (2017). 2017nyŏndo chŏngsep'yŏnggawa 2018nyŏndo chŏnmang [status assessment of 2017 and forecast for 2018]. Seoul: Institute for National Security Strategy.

Ji, D. (2025). S. Korea's 'imperial presidency': How it became threat to democracy. Seoul: The Korea Herald.

Kalbassi, C. (2016). Identifying crisis threats: A partial synthesis of the literature on crisis threat assessment with relevance to public administrations. J. Risk Anal. Crisis Response 6, 110–121. doi: 10.2991/jrarc.2016.6.3.1

KBS (1991). Miguk, puk’an haekkaebal kanggyŏngipchang [the United States adopts a hardline stance on North Korea’s nuclear development]. Seoul: Korean Broadcasting System.

Kim, S. (2022). N. Korea continuing to run uranium enrichment facility at Yongbyon site: IAEA. Seoul: Yonhap News.

Kim, Y. (2001). Kim Yŏngsam taet’ongnyŏng hoegorok: Minjujuŭirŭl wihan naŭi t’ujaeng [the autobiography of Kim young-Sam 1: My struggle for democracy]. Seoul: Chosun Media.

KINU (2024). The KINU unification survey 2024: North Korea’s two hostile states doctrine and South Korea’s public opinion on nuclear armament. Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification.

Klingner, B. (2018). What lies behind North Korea’s ‘charm offensive’ at the olympics. Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation.

KNSI (2009). “3ch’a puk’aegwigi punsŏkkwa chŏngch’aekcheŏn” [the analysis of the third north Korean nuclear crisis and policy advice]. Seoul: Korean National Strategy Institute.

Lee, M. (2009a). Address at a luncheon hosted by Council on Foreign Relations. Sejong: Presidential Archives.

Lee, W. (2023). Hanbando haekkyunhyŏngnon: Puk’anŭi haekpoyuguk’wawa mijung p’aegwŏn’gyŏngjaeng [the theory of nuclear balance on the Korean peninsula: North Korea's Nuclearization and U.S.-China hegemonic competition]. Paju: Yeoksain.

Lee, Y. (2018). Puk’aeng 30nyŏnŭi hŏsanggwa chinshil: Hanbando haekkeimŭi chongmal [truth and delusions behind 30 years of north Korean nuclear saga: The end of nuclear game on the Korean peninsula]. Paju: Hanul Academy.

Lester, L. (2019). 2017 North Korean nuclear test was order of magnitude larger than previous tests. Advancing Earth and Space Sciences. Available online at: https://news.ucsc.edu/2019/06/nuclear-test.html. (accessed July 21, 2023).

Lim, H. (2021). Puk’an, haekp’ŭrogŭraem chŏllyŏk IAEA p’yŏnggae ch’ŏngwadae ‘pyŏl-do ŭigyŏn ŏpta’ [IAEA: ‘North Korea fully committed to nuclear program’; blue house stays silent]. Paju: Yonhap News.

Lyotard, J. -F. (1984). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Mohan, J. (2023). Nuclear weapons gaffe in South Korea is a warning to leaders everywhere. Chicago, IL: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Moon, C. (2012). The sunshine policy: In defense of engagement as a path to peace in Korea. Seoul: Yonsei University Press.

Moore, G. J. (2008). America’s failed North Korea nuclear policy: A new approach. Asian Perspect. 32, 9–27. doi: 10.1353/apr.2008.0002

Murtazashvili, J. B. (2022). The collapse of Afghanistan. J. Democr. 33, 40–54. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0003

Nah, T. L. (2013). Explaining North Korean nuclear weapons motivations: Constructivism, liberalism, and realism. North Korean Rev. 9, 61–82. doi: 10.3172/NKR.9.1.61

Niksch, L. A. (2003). North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Nyman, J. (2013). “Securitization theory” in Critical approaches to security. ed. L. J. Shepherd (Oxon: Routledge), 51–62.

Oberdorfer, D., and Carlin, R. (2013). The two Koreas: A contemporary history. New York, NY: Hachette.

Pannett, R. (2021). Taliban spokesman says ‘no proof’ bin laden was responsible for 9/11 attackes. Washington, DC: The Washington Post.

Park, H., and Kim, B. (2012). Time to balance deterrence, offense, and defense? Rethinking South Korea’s strategy against the north Korean nuclear threat. Korean J. Def. Anal. 24, 515–532. doi: 10.22883/kjda.2012.24.4.008

Persio, S. L. (2018). Will North Korea attack the U.S.? It would be a ‘suicidal’ move, Russian expert reports from Pyongyang. Washington, DC: Newsweek.

Pollack, J. D. (2011). No exit: North Korea, nuclear weapons, and international security. Oxon: Routledge.

Pollack, J. D. (2019). What sort of deal does North Korea expect? Washington, DC: Arms Control Wonk.

Reuters (2021). Taliban seize more Afghan cities, assault on capital Kabul expected. London: Reuters.

Roh, M. (2003b). Remarks at a dinner cohosted by the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Sejong: Presidential Archives.

Rosenthal, U., Charles, M. T., and Hart, P. T. (1989). Coping with crises: The management of disasters, riots, and terrorism. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas.

Roux-Dufort, C. (2007). Is crisis management (only) a management of exceptions? J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 15, 105–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2007.00507.x

Russel, D. (2019). How the world should deal with North Korea’s ‘new normal’. Tokyo: The Japan Times.

Rythoven, E. V. (2015). Learning to feel, learning to fear? Emotions, imaginaries, and limits in the politics of securitization. Secur. Dialogue 46, 458–475. doi: 10.1177/0967010615574766

Sigal, L. V. (1999). Disarming strangers: Nuclear diplomacy with North Korea. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Snyder, S., and Byun, S. (2011). Cheonan and Yeonpyeong: The northeast Asian response to North Korea’s provocations. RUSI J. 156, 74–81. doi: 10.1080/03071847.2011.576477

Svensson, P. (1986). Stability, crisis and breakdown: Some notes on the concept of crisis in political analysis. Scand. Polit. Stud. 9, 129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.1986.tb00341.x

Terry, S. M. (2013). North Korea’s strategic goals and policy towards the United States and South Korea. Int. J. Korean Stu. 17, 63–92.

Wæver, O. (1995). “Securitization and desecuritization” in On security. ed. R. D. Lipschutz (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 46–87.

Wampler, R. A. (2017). Engaging North Korea: Evidence from the Bush I administration. Available online at: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/korea-nuclear-vault/2017-11-08/bush-43-chose-diplomacy-over-military-force-north-korea (accessed July 19, 2023).

Wit, J. S., Poneman, D. B., and Gallucci, R. L. (2004). Going critical: The first north Korean nuclear crisis. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Wyeth, G. (2020). Time to reopen the Kaesong industrial complex? A conversation with Jin-Hyang Kim. London: The Diplomat.

Yoo, J. (2024). S. Korea warns of end of N. Korean regime if Pyongyang uses nuclear weapons. Seoul: Yonhap News.

Keywords: North Korea, nuclear weapons, crisis, securitization, security discourse

Citation: Yoon S (2025) Why is there no “third” Korean nuclear crisis? Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1630455. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1630455

Edited by:

Stylianos Ioannis Tzagkarakis, Hellenic Open University, GreeceReviewed by:

Helder Ferreira Do Vale, Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), BrazilGeorgia Dimari, Ecorys, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Yoon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seongwon Yoon, dmlzaW9ueXN3QGhhbnlhbmcuYWMua3I=

Seongwon Yoon

Seongwon Yoon