- Carnegie Mellon Institute for Strategy and Technology, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Taiwan is not just a victim-in-waiting, damsel in distress, or pawn in a new Cold War. Taiwan stands as an exemplar: the world’s first “Chinese democracy” and a democratic David in the shadow of an autocratic Goliath. Taiwan’s success in deepening democracy and resisting Chinese sharp power may hold lessons on how to counter the rising global tide of authoritarianism. To elucidate these lessons, we review Taiwan’s democratic history and ongoing efforts to defend its hard-won democracy.

1 Introduction

Globally, democracy is in peril. Publics in every region of the world appear increasingly dissatisfied with democracy (Wike, 2025). Political freedom worldwide has declined each of the last 18 years, according to Freedom House (Gorokhovskaia and Grothe, 2025). According to the Varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project, average (population-weighted) democracy levels globally in 2024 were back to 1985 levels, with 45 countries autocratizing but only 19 democratizing (Nord et al., 2025).

As democrats endeavor to defend democracy in an era of authoritarian sharp power (Walker, 2018; Dobson et al., 2023) and renewed great power competition (Chin et al., 2023), Taiwan is a pivotal frontline state (Erickson et al., 2024). Most recent discourse on Taiwan in the West is (perhaps understandably) focused on deterring Chinese aggression given growing Chinese military power and the rising threat of Chinese invasion (e.g., Kuo et al., 2024b; Robertson, 2024; Lin et al., 2025). Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, some fear that Taiwan could be next (e.g., Diamond, 2022, p. 174). This has led to urgency and reinvigorated debate in Washington over U. S. Taiwan policy and how to navigate the “patron’s dilemma” vis-à-vis Taiwan (Yarhi-Milo et al., 2016). Whereas some stress Taiwan’s strategic importance to the U. S. and call for greater strategic clarity and defense assistance to Taiwan (Kuo, 2023; Kuo et al., 2024a; Byman and Jones, 2025), “restrainers” doubt that Taiwan is a vital U. S. interest and favor greater ambiguity/limits on U. S. commitment (Lai, 2025).

Yet Taiwan is much more than a victim-in-waiting, damsel in distress, or pawn in a new Cold War. No longer an authoritarian U. S. client, Taiwan has become an exemplar: the world’s first “Chinese democracy” (Chao and Myers, 1994), a democratic David in the shadow of an autocratic Goliath (Sacks, 2024), and proof that liberal democracy is not incompatible with “Asian values” (Chang et al., 2017). Taiwan’s success in deepening democracy and resisting Chinese “sharp power” (Chen, 2022) hold lessons on how to counter rising global authoritarianism. To elucidate these lessons, this article reviews Taiwan’s democratic history and ongoing efforts to defend Taiwan’s hard-won democracy.

2 From Cold War martial law to Taiwan’s post-Cold War democratization

After half a century as a Japanese colony (1895–1945), Taiwan (Formosa) reverted to the sovereignty of the Republic of China (ROC) after Japan’s defeat in World War II. After the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) declared the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the Nationalist Party (KMT) forces fled for Taiwan. Combatants in the Chinese civil war became separated by the Taiwan Strait.

For most of the Cold War, Taiwan was ruled by a personalist single-party (KMT) authoritarian regime led by Chiang Kai-shek until his death in 1975 and then by his son Chiang Ching-kuo until his death in 1988 (Geddes et al., 2014; Wright, 2021). Unlike its mainland communist rival, the KMT pursued capitalist development (with U. S. support) and aligned closely with the U. S. (Lee, 2020). Still, the KMT was a Leninist party that harshly repressed dissent on Taiwan (Dickson, 1993).1 Mainland Chinese—representing only 14 percent of Taiwan’s population after 1949—monopolized government, leaving local Taiwanese—84 percent of the population—powerless (Vogt et al., 2015).

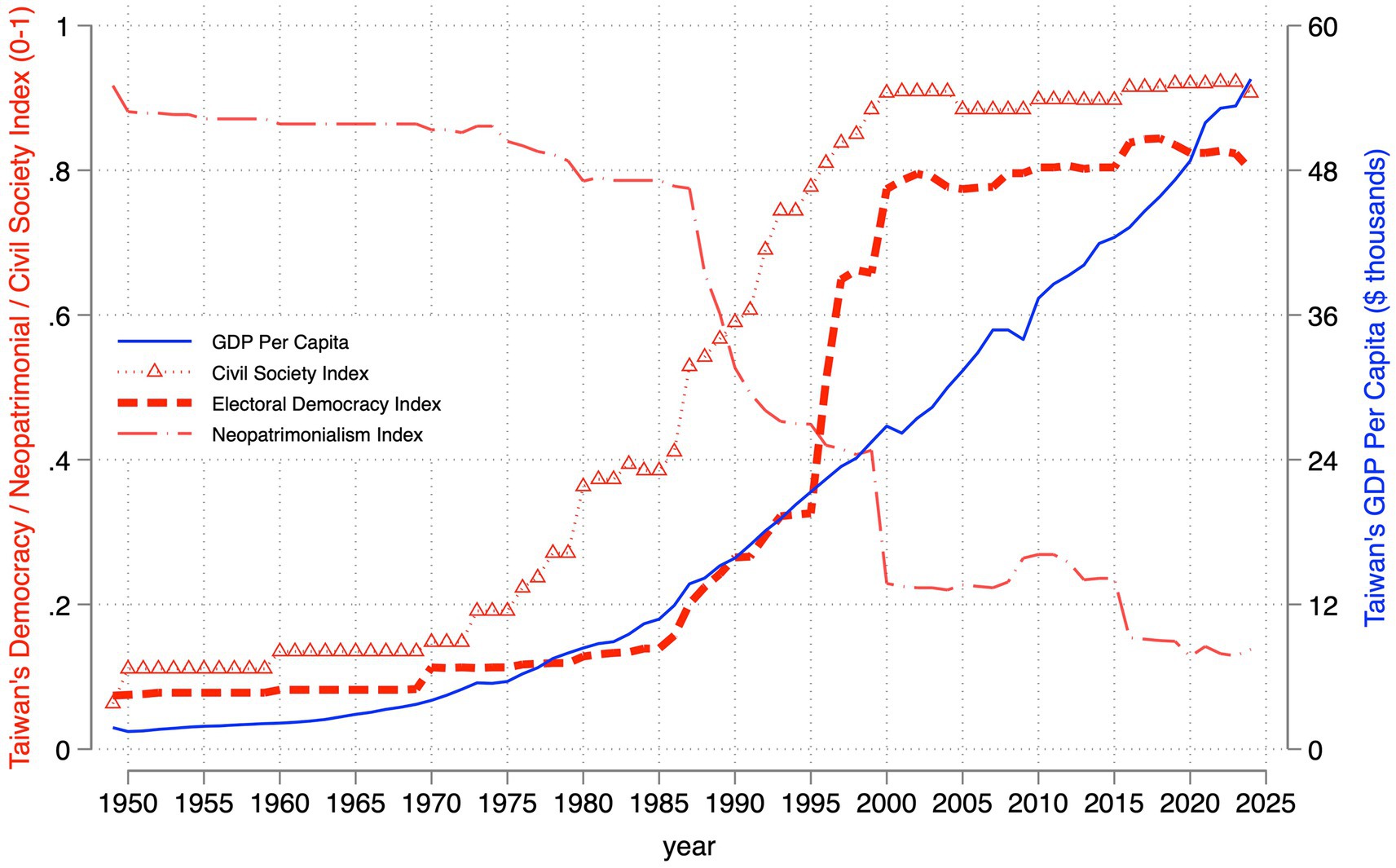

After three decades of martial law (since 1949), several trends—bottom-up pressures, top-down calculations, and international factors—converged after 1979 to put Taiwan on a path of gradual political liberalization in the 1980s (see Figure 1). Taiwan’s human rights record gradually improved after 1980 (Fariss et al., 2020) as did Taiwan’s electoral democracy scores after 1985.

Domestically, decades of authoritarian modernization had grown the middle class, empowering civil society and leading to more “bottom up” mass mobilization, social movements, and student activism (Treisman, 2015; So and Hua, 1992; Cheng, 1989; Fan, 2018; Chen, 2020). The number of social protests ballooned from 175 in 1983 to 1,172 in 1988 (Chu, 1993). To manage backlash to repression of the Kaohsiung incident in December 1979, Chiang Ching-kuo agreed to elections in 1980 and 1983 allowing opposition (dangwai, “outside the party”) candidates to compete for the first time (Yu, 2004). The dangwai coalesced into the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in September 1986. The new party embraced Taiwan identity and courted elements that had been excluded by the KMT.

At the top of the KMT regime, key leaders believed that the party was strong and would fare well under democracy (Copper, 2019; Slater and Wong, 2022). In his final years, Chiang Ching-kuo thus became a cautious advocate of political reform; he lifted martial law in July 1987 (Taylor, 2000, 369–428). The KMT’s and Chiang’s domestic strength was matched by Taiwan’s international weakness.

Internationally, Taiwan’s growing diplomatic isolation—from the loss of its UN seat in 1971 to the normalization of US-China relations in 1979—as the third wave of democracy took off and the Cold War thawed added geopolitical incentives for the KMT to democratize. After the US-ROC mutual defense treaty was terminated in 1980, the support of U. S. Congress under the Taiwan Relations Act for continuing arms sales became a security imperative for Taiwan’s leaders. Improving Taiwan’s human rights was key to gaining that U. S. congressional support (Bush, 2004). After the overthrow of another autocratic American ally, Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, in February 1986, Ching-kuo “saw the handwriting on the wall” and moved quicker to lift martial law (Katsiaficas, 2013, p. 192).

Taiwan continued political liberalization after 1988 under Lee Teng-hui, the first Taiwanese-born president. Mass protests in March 1990—the student-led Wild Lily movement—called for direct presidential elections and new elections for all legislative seats; that month Lee was indirectly elected by the National Assembly, which was full of old, unelected members (Chin and Zheng, 2025).

Given Taiwan’s international isolation and reliance on Western linkage and leverage for survival, Lee was unwilling to continue to pay the cost of repression to maintain the KMT’s monopoly on power (Levitsky and Way, 2010, p. 309–18). In the wake of the Wild Lily Movement, Lee negotiated with the DPP, which paved the way for the National Affairs Conference (summer 1990) and direct elections to the National Assembly in 1991 and Legislative Yuan in 1992 (Chao and Myers, 1994).

In 1996, Lee won the island’s first direct presidential elections, buoyed by his nationalist credentials and the electorate’s backlash to China’s intimidation with missile tests (Hood, 1996; Tien, 1996). Taiwan’s democratic transition was completed in 2000, when DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian won presidential elections–ending more than five decades of KMT rule on the island (Hsieh, 2001).

3 Taiwan’s democratic deepening in the 21st century

In the twenty-first century, Taiwan has had several more peaceful transfers of power: Ma Ying-jeou took back the presidency for the KMT from 2008 to 2016, but the DPP reclaimed the presidency in 2016, first under Tsai Ing-wen (Taiwan’s first female president) and then under Lai Ching-te since 2024. Taiwan’s Freedom House score steadily increased from 87 in 2011 to 94 (out of 100) in 2024 (Gorokhovskaia and Grothe, 2025). Taiwan’s human rights record has also continued to improve, maintaining globally high levels of human rights protections since the late 2000s (Fariss et al., 2020).

Since 2001, Taiwan’s impressive democratic gains are, in part, attributable to curbing “black gold” politics -- political corruption and vote-buying of local politicians with close ties to organized crime and/or corporate interests (Goebel, 2016; Templeman, 2022; Chin, 2003). Though judicial reform is still a work in progress, rule of law has also deepened (Templeman, 2022). Despite recent increasing elite political polarization between the pan-Blue (KMT-led) coalition and the pan-Green (DPP-led) coalition, Taiwan’s public is less polarized, with convergence toward a separate Taiwan identity as opposed to Chinese identity, which used to predominate (Clark et al., 2019; Bush, 2021b).

Taiwan’s civil society has also continued to be a force for democratic consolidation. In 2008, the student-led Wild Strawberry movement used a month-long sit-in to protest the visit to Taiwan of a high-level Chinese diplomat and restrictions on protest (Chin and Zheng, 2025). In 2012, the “Wild Strawberry generation” protested Chinese influence over Taiwan’s media (Tsui, 2012). In 2014, the student-led Sunflower movement blocked a KMT-proposed free trade deal with China (Ho, 2019). This subsequent “sunflower generation” determined to protect Taiwan (Davidson, 2024).

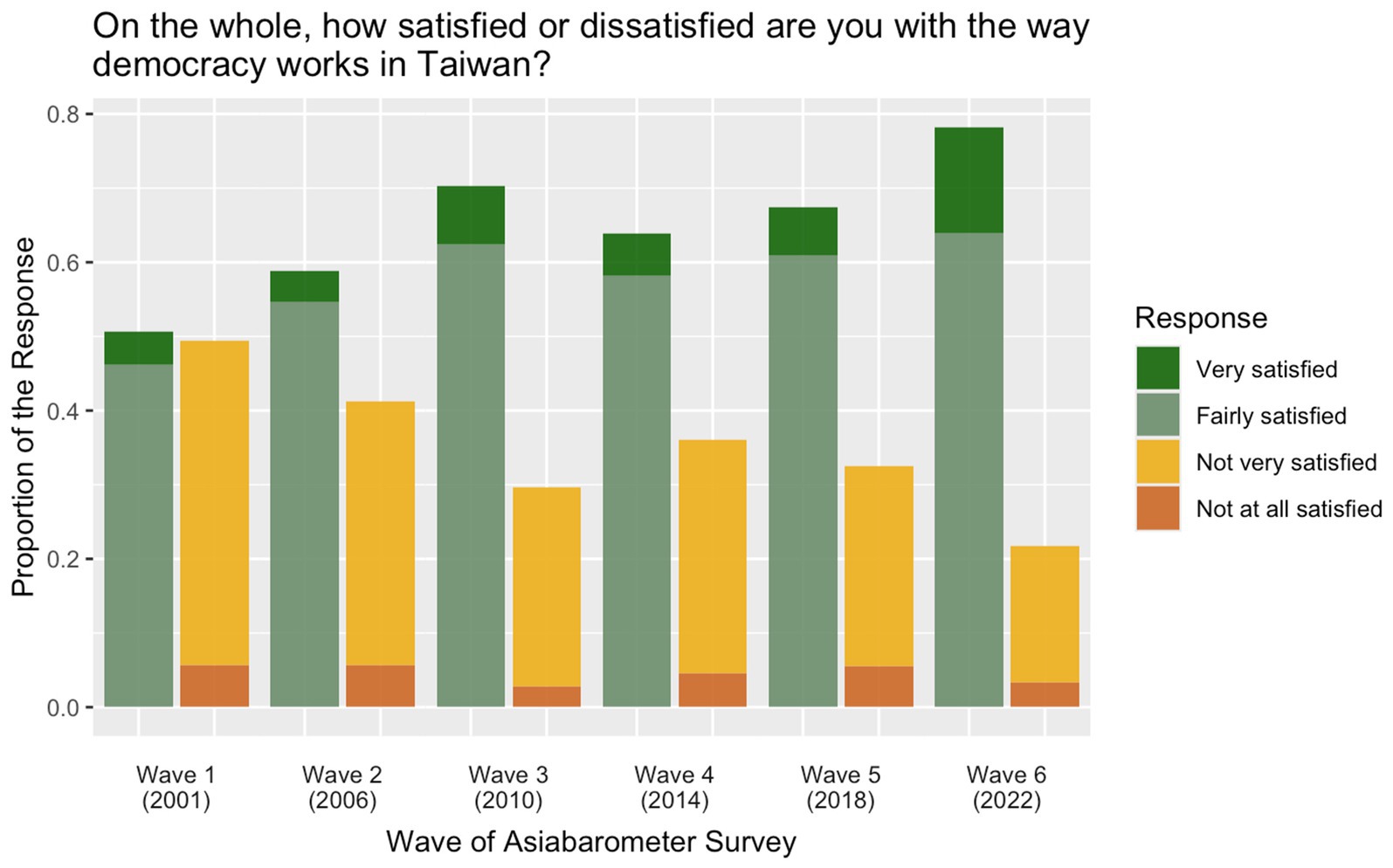

Mass values in Taiwan overwhelmingly support democracy and human rights (Gubbala and Fetterolf, 2024).2 Most Taiwanese say living in a democracy is “absolutely important” (World Values Survey, 2025). In contrast to global trends (Wike, 2025), satisfaction with the way democracy works in Taiwan has increased since 2001 to nearly 80 percent in 2022 (see Figure 2). According to Asian Barometer (2025) surveys, nearly three quarters of Taiwanese say democracy is capable of solving the problems of Taiwan’s society, up more than 15 points since 2018. 80 percent or more of Taiwanese consistently reject authoritarian alternatives (single-party, military, or technocratic rule).

As a result, Taiwan has experienced little democratic backsliding recently, and still boasts robust electoral participation, electoral contestation, and constraints on the executive (Boese et al., 2022).

4 Ongoing challenges to Taiwan’s democracy

Despite democratic deepening in the twenty-first century, Taiwan’s democracy faces continuing challenges. According to a leading democratic theorist, modern democracies face two key dangers: polarization and populism (Adam Przeworski [@AdamPrzeworski], 2022). Both are rising in Taiwan, though remain moderate compared to some democracies in 2024 per V-Dem data (Nord et al., 2025).

Populism in Taiwan is driven by cultural backlash and economic anxiety over cross-Strait economic dependence (Cheng, 2025), which has driven discontent with the establishment (Gallina et al., 2025). In 2024, third party/independent voters were a record 26% of voters, leading the populist Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) to win eight seats and become kingmaker in the Legislative Yuan (Shen, 2024).

Polarization has fostered a “no-holds-bar” “politics of paralysis” in Taiwan (Kuo and Kish, 2025; Kuo, 2025). Though the DPP retained the presidency in 2024 with William Lai’s victory, the DPP lost its legislative majority; the KMT edged them out. Divided government, in turn, has led to executive-legislative conflict and legislative gridlock. Lai has accused the opposition of obstruction, while the opposition has accused Lai of seeking an imperial presidency (Hass, 2025). Divisions over China provide the major fuel for polarization. The DPP favors a defense build-up and more assertive approach, while the KMT seeks to maintain cordial/strong ties to the PRC (Nachman and Yen, 2025).

With the help of the TPP, the KMT-controlled legislature passed two controversial bills in December 2024 giving greater power to the legislature at the expense of the executive and judiciary (Chung et al., 2024). One paralyzed the Constitutional Court while the KMT refuses to confirm Lai’s judicial nominees; the other increased voter petition requirements to recall elected officials (Levine, 2025). Meanwhile, the parties waged a budget battle that resulted in the KMT cutting central government spending (including on defense) and shifting spending to local governments (Reuters, 2024).

With Taiwan on the brink of a constitutional crisis (Templeman, 2025b), DPP activists launched a movement to recall what they saw as pro-China KMT legislators. However, after recall elections in July and August 2025, all 31 KMT legislators kept their seats (Hioe, 2025). Divided government is here to stay, for now. During the only prior period of divided government (2000–2008), polarization did not derail Taiwan’s democratic deepening; hope remains it will not derail Taiwan’s democratic consolidation today, with both sides perhaps now incentivized to compromise (Templeman, 2025a).

Internationally, Taiwan also faces headwinds (Brown, 2025). In addition to mounting pressure from China (see section 5 for Taiwan’s efforts to counter this pressure), the Trump administration has posed strategic problems for Taiwan. In August 2025, the U. S. imposed 20% reciprocal tariffs after a trade deal wasn’t reached. Meanwhile, the Trump administration is also pushing Taiwan to provide more for its own defense and thus ease problems of “burden-sharing” (Whiton, 2025; Lai, 2025).

Despite these challenges, Taiwan’s democracy remains secure and stable for now. And despite polarization, there remains surprising consensus on the big issues. Neither the DPP, KMT, nor TPP favor re-unification with China. “All are pro-democracy and anticommunist, all want to maintain ties with the United States, and none support immediate independence” (Gordon and Hass, 2025).

In his national day speech on October 10, 2025, President Lai presented a hopeful vision, noting this year marks a milestone in Taiwan’s democratization, with the time since the end of martial law now surpassing that of the martial law period. Lai promised to continue to promote “whole-of-society” resilience to deter Chinese aggression (Office of the President Republic of China (Taiwan), 2025). It is to Taiwan’s critical efforts to resist China’s democratic subversion efforts that we now turn.

5 Taiwan’s lessons on resisting Chinese sharp power

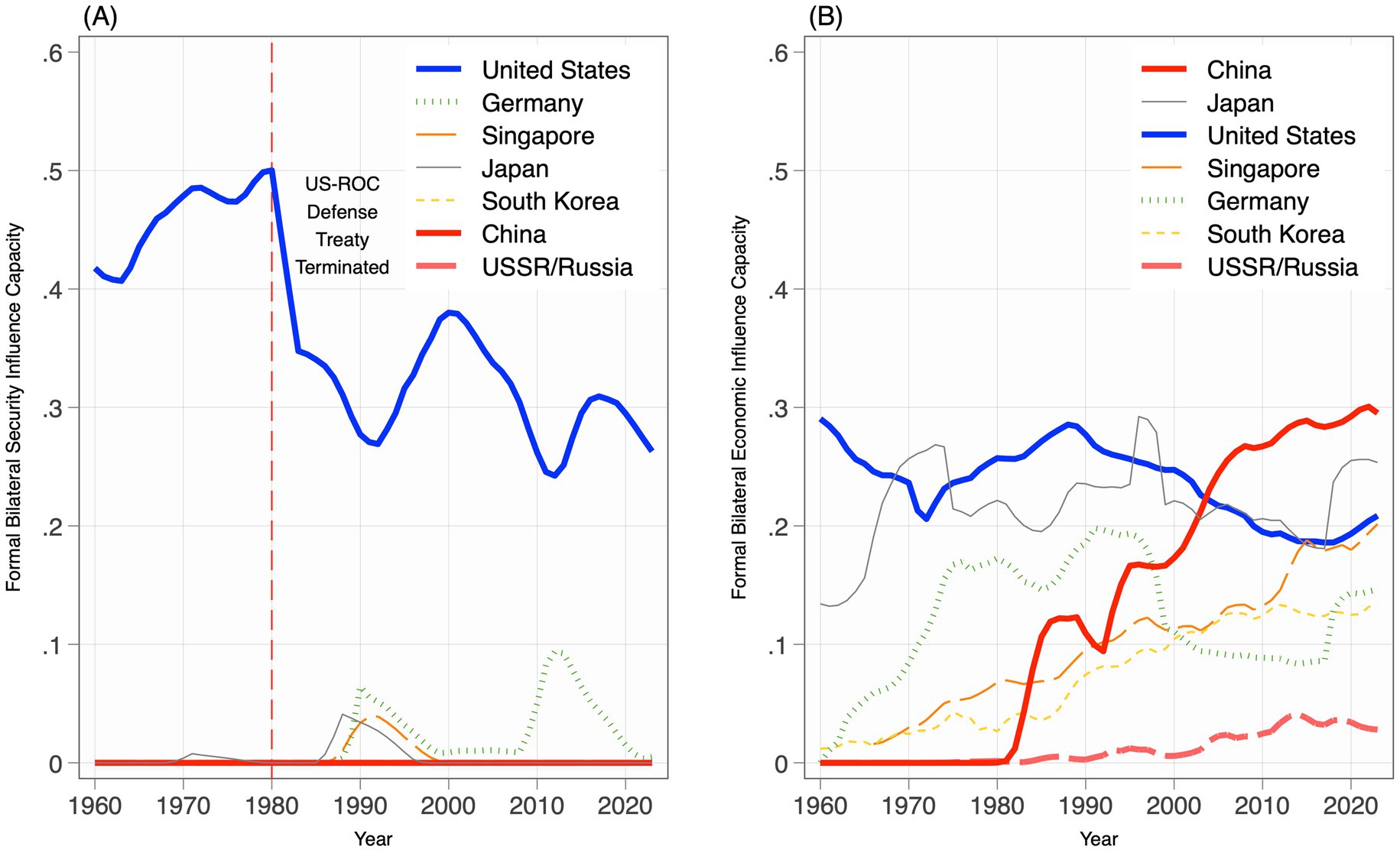

U. S. influence capacity in Taiwan has gradually declined since 1980 while Chinese influence capacity has gradually risen since the mid-1980s, per the formal bilateral influence capacity (FBIC) index (Moyer et al., 2024). However, the overall trend masks key variation across security and economic realms. In Figure 3A, we see that U. S. security influence capacity dropped significantly between 1980 and 1990, but that in 2023 (the last year for which we have data) U. S. influence in security realm on Taiwan remained hegemonic. Figure 3B shows that Chinese influence capacity in Taiwan has risen exclusively in the economic realm, where it overtook the U. S. in the mid-2000s.

Figure 3. Security influence capacity (A) vs. economic influence capacity (B) levels in Taiwan, 1960–2023.

In the latest Asian Barometer poll (2022), seven in 10 Taiwanese say U. S. influence is mostly positive. By contrast, four in five Taiwanese say that China’s influence is mostly negative, up from 50 to 60 percent in prior surveys. Recent souring on Chinese influence (economic incentives and military threats) is in part tied to the rise of a “Taiwanese only” identity (Wang, 2017). It is also in part a response to the evolution of China’s influence operations that has seen a decline in China’s “soft power” (e.g., public diplomacy emphasizing cultural affinity and tourism) and the rise of China’s “sharp power,” which seeks to more directly undermine Taiwan’s autonomy, deter moves toward independence, and even actively meddle in democratic elections (Walker, 2018; Wu, 2019).

Two aspects of Chinese sharp power in Taiwan stand out: partisan electoral intervention and (dis)information campaigns. The latter are increasingly used in the pursuit of the former (e.g., Quirk, 2021). Since 1996, China has repeatedly sought to shape the outcome of Taiwan’s elections (Barss, 2022), though China’s tactics have shifted: “the broad threats of earlier elections have been replaced with narrowly targeted efforts to mobilize Beijing-friendly segments of Taiwan’s population” (Wilson, 2022). For example, China has used religious institutions such as urban Mazu temples to mobilize votes for relatively pro-China (e.g., KMT) candidates (Sher et al., 2024). Over time, Taiwan’s political parties have adapted to China’s repeated meddling in elections (Wilson, 2022).

Under Xi Jinping, the Chinese government’s dissemination of false information abroad—with Taiwan a primary target—has increased, especially since 2018 (Wiebrecht, 2022; Chen, 2022). China has waged an online foreign influence effort in Taiwan since at least 2014 (Martin et al., 2023). For over a decade, Taiwan has been the country most affected by disinformation, per V-Dem data (Mien-chieh and Hetherington, 2024). China’s information manipulation operations in Taiwan have four goals: (1) undermine DPP’s electoral success, (2) sell the CCP’s governance model, (3) induce anxiety about Taiwan’s strategic situation to make resistance seem futile, and (4) unravel the fabric of Taiwan’s democracy by pushing polarization and undermining trust in institutions (Niven, 2024).

In the runup to Taiwan’s 2020 elections, China launched an aggressive disinformation campaign, which failed to block a landslide DPP victory and Tsai Ing-wen’s re-election (Kurlantzick, 2019; Templeman, 2020; Huang, 2024). China’s propaganda has become more sophisticated since, including more use of local proxies, AI-generated videos, and conspiracy theory narratives that exploit cognitive biases (Chan and Thornton, 2022; Iyengar, 2024; Hsu, 2024). Social media platforms such as TikTok have become key battlegrounds in China’s information warfare against Taiwan (Wu, 2025). A 2024 study by Taiwan’s National Security Bureau reported a 60% increase in Chinese disinformation (identifying over 28,000 fake accounts), with young Taiwanese as the primary targets (Yan, 2025).

As disinformation campaigns become more common and covert (Mattis and Yu, 2025), Taiwan has shifted from fining actors for spreading fake news to promoting news literacy and use of fact-checking apps (Aspinwall, 2024; Shu-ling, 2023; Cheung, 2023a). Civil society groups like Doublethink Lab and Taiwan Information Environment Research Center have continuously monitored ongoing PRC information warfare since 2019 (Chen, 2022). Taiwan’s approach to combatting information manipulation has been described as the “POWER” model: purpose-driven, organic, whole-of-society, evolving, and remit-bound (Doublethink Lab, 2024). Taiwan’s young techies and entrepreneurs play key roles fighting disinformation; Taiwan AI Labs, for example, has used AI to identify and counter AI-generated deepfake messaging (Feigenbaum and Popova, 2024).

As a result, China’s recent election interference in Taiwan has had mixed results at best. China used propaganda, economic statecraft, and military intimidation to try to prevent a DPP victory in the January 2024 elections (Cheung, 2023b; Kuo and Staats, 2024; Kuo, 2024), but Lai managed to prevail (by admittedly a narrow margin, Chong, 2024). DPP authorities have claimed that China also sought to interfere in the 2025 recall elections (Reuters, 2025a), though with what effect is unclear.

The Lai administration is pioneering one of the world’s first “whole-of-society resilience” initiatives (Thompson, 2024) to combat rising Chinese sharp power. In March 2025, President Lai declared China a “foreign hostile force” under Taiwan’s 2019 “Anti-Infiltration Act” (Bloomberg, 2025), and outlined a series of 17 legal and economic counter-measures to Chinese “infiltration” (Reuters, 2025b). In October 2025, after former Taipei mayor and KMT chairperson candidate claimed that “external cyber forces” sought to influence the party’s upcoming chairperson election, DPP lawmakers proposed cooperation with the opposition to tighten national security laws (ANI, 2025).

6 Conclusion

As Taiwan is a testing ground for Chinese sharp power and on the frontlines fighting disinformation (Chen, 2022), understanding the sources of Taiwan’s democratic emergence and consolidation provides insights that may prove important for promoting democratic resilience during the ongoing global third wave of autocratization (Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019).

While Taiwan’s democratization may not be replicable in mainland China any time soon (Chin, 2018), other countries can still learn valuable lessons from Taiwan’s democratic experience. Taiwan demonstrates that an active civil society and responsible leaders—aided by civil resistance and outside pressure from democracies—can forge and keep democracy even in a once-Leninist dictatorship.

Beyond being a “frontline state,” Taiwan plays an active role in the global fight for democracy, as Taiwan’s former President Tsai Ing-wen (2016–2024) passionately noted in Foreign Affairs in 2021 (Tsai, 2021). In 2003, Taiwan established Asia’s first democracy promotion NGO, the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, modeled on the U. S. National Endowment for Democracy. It has provided “critical support to Asian pro-democracy civil society groups” (Green and Twining, 2024).

Despite its flaws, Taiwan’s democracy and democratic resilience remain inspirational (Hur and Yeo, 2024), and Taiwanese themselves would do well to recall the lessons that secured their democracy in the first place. Even as the DPP and KMT play constitutional hardball, Taiwan’s partisan leaders should continue to play by democratic rules—and remember the geopolitical imperative to remain democratic remains strong.3 Taiwan remains a democratic David worth supporting and studying (Khrestin, 2024). After all, Taiwan may just be the democratic light the world desperately needs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JC: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation. SR: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The origins of the present collaboration lie in the “final teaching assignment”—a blog originally titled “Taiwan is the Democratic Light that the World Desperately Needs”—that one of us (Staten) submitted for an introductory International Relations course at CMU taught by the other of us (Chin). In expanding that blog idea into a full research report, we ultimately benefitted from the excellent research assistance of two other CMU students: YG Gu (who compiled Asia Barometer data and created Figure 2) and Kevin Zheng (who helped research the Wild Lily movement and the importance of civil society mobilization for Taiwan’s democracy).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

^Though repression became more discriminate and surveillance-based after 1955, during the “white terror” era Taiwan had similar levels of internal security personnel per capita as East Germany or North Korea today (Greitens, 2016, p. 9).

^In 2019, Taiwan became the first country in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage (Paulson, 2024).

^AsBush (2021a, p. 248) puts it, “Uniquely, Taiwan has included its democratic system in its security toolkit.”

References

Adam Przeworski [@AdamPrzeworski]. (2022). This is my current understanding of the value and the essence of democracy, in 350 words. Twitter, January 19.

ANI (2025) Taiwan lawmakers call for bipartisan action to counter Chinas election interference. The Tribune, October 12. Available online at: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/world/taiwan-lawmakers-call-for-bipartisan-action-to-counter-chinas-election-interference/

Asian Barometer. (2025) Accessed May 19, 2025. Available online at: https://www.asianbarometer.org/.

Aspinwall, N. (2024). Taiwan learned you can’t fight fake news by making it illegal. Foreign Policy, January 16. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/16/taiwan-election-china-disinformation-lai/.

Bloomberg (2025) Taiwan president formally designates China a ‘Foreign Hostile Force. The straits times, March 14. Available online at: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/taiwan-president-formally-designates-china-a-foreign-hostile-force

Boese, V. A., Gates, S., Henrik Knutsen, C., Nygård, H. M., and Strand, H. (2022). Patterns of democracy over space and time. Int. Stud. Q. 66:sqac041. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqac041

Brown, K. (2025). Taiwan faces a precarious future – whether or not US and China continue on path to conflict. Conversat. doi: 10.64628/AB.h5veyrmap

Bush, R. C. (2004). “Congress gets into the Taiwan Human Rights Act” in At Cross Purposes. 1st ed (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe).

Bush, R. C. (2021a). Difficult Choices: Taiwan’s quest for security and the good life. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Bush, R. C. (2021b). Taiwan’s democracy and the China challenge. Brookings Institution, January 22. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/taiwans-democracy-and-the-china-challenge/.

Byman, D., and Jones, S. G. (2025). How to toughen up Taiwan. Foreign Aff. March 13. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/how-toughen-taiwan

Chan, K., and Thornton, M. (2022). China’s changing disinformation and propaganda targeting Taiwan. The Diplomat, September 19. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2022/09/chinas-changing-disinformation-and-propaganda-targeting-taiwan/.

Chang, Y.-H., Wu, J. J., and Weatherall, M. (2017). Popular Value Perceptions and Institutional Preference for Democracy in ‘Confucian’ East Asia. Asian Perspect. 41, 347–375. doi: 10.1353/apr.2017.0017

Chao, L., and Myers, R. H. (1994). The first Chinese democracy: political development of the Republic of China on Taiwan, 1986-1994. Asian Surv. 34, 213–230. doi: 10.2307/2644981

Chen, W. (2020). “Student activism and authoritarian legality transition in Taiwan” in Authoritarian legality in Asia. eds. W. Chen and H. Fu. 1st ed (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Chen, K. W. (2022). Combating Beijing’s sharp power: Taiwan’s democracy under fire. J. Democr. 33, 144–157. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0029

Cheng, T.-j. (1989). Democratizing the quasi-Leninist regime in Taiwan. World Polit. 41, 471–499. doi: 10.2307/2010527

Cheng, H. (2025). Distinctive economic anxiety and cultural backlash in Taiwan: two key dimensions driving the rise of populism in Taiwan. Taiwan Politics, 1–21. doi: 10.58570/001c.142786

Cheung, E. (2023a) Taiwan Election: Taiwan Faces a Flood of Disinformation from China Ahead of Crucial Election. Here’s How It’s Fighting Back. CNN, December 16. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2023/12/15/asia/taiwan-election-disinformation-china-technology-intl-hnk/index.html

Cheung, E. (2023b) Taiwan Official: Chinese Leaders Met to Hash out Interference Plans Targeting Island’s Presidential Election. CNN, December 8. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2023/12/08/asia/taiwan-intelligence-china-leaders-meeting-election-interference-intl-hnk/index.html

Chin, K.-l. (2003). “Black gold politics: organized crime, business, and politics in Taiwan” in Menace to society. Roy Godson editor. (New York: Routledge).

Chin, J. J. (2018). The longest march: why China’s democratization is not imminent. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 23, 63–82. doi: 10.1007/s11366-017-9474-y

Chin, J. J., Skinner, K., and Yoo, C. (2023). Understanding national security strategies through time. Tex. Natl. Secur. Rev. 6, 103–124. doi: 10.26153/tsw/48842

Chin, J. J., and Zheng, K. (2025). The lasting legacy of Taiwan’s 1990 wild lily movement. The Diplomat. March 16. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2025/03/the-lasting-legacy-of-taiwans-1990-wild-lily-movement/

Chong, J. I. (2024) Taiwan’s voters have spoken. Now what: implications of Taiwan’s 2024 elections for Beijing and Beyond. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 9 Available online at: https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/02/taiwans-voters-have-spoken-now-what-implications-of-taiwans-2024-elections-for-beijing-and-beyond?lang=en

Chu, Y.-h. (1993). “Social protests and political democratization in Taiwan” in The Other Taiwan, 1945–92. 1st ed Murray A. Rubinstein editor (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe).

Chung, J., Garcia, S., and Khan, F. (2024). KMT, TPP pass controversial changes. Taipei Times, December 21. Available online at: https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2024/12/21/2003828864.

Clark, C., Tan, A. C., and Ho, K. (2019) Political polarization in Taiwan and the United States: a research puzzle Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10092/17739

Davidson, H. (2024). How the sunflower movement birthed a generation determined to protect Taiwan : World News The Guardian, March 21. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/mar/21/what-is-taiwan-sunflower-movement-china.

Diamond, L. (2022). Democracy’s arc: from resurgent to imperiled. J. Democr. 33, 163–179. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0012

Dickson, B. J. (1993). The lessons of defeat: the reorganization of the Kuomintang on Taiwan, 1950-52. China Q. 133, 56–84.

Dobson, W. J., Masoud, T., and Walker, C. (2023). Defending democracy in an age of sharp power. Baltimore: JHU Press.

Doublethink Lab (2024) Taiwan POWER: a Model for resilience to foreign information manipulation and interference. Medium, August 30. Available online at: https://medium.com/doublethinklab/taiwan-power-a-model-for-resilience-to-foreign-information-manipulation-interference-70ea81f859b7

Erickson, A. S., Collins, G. B., and Pottinger, M. (2024). The Taiwan catastrophe. Foreign Aff. February 16. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/taiwan-catastrophe

Fan, Y. (2018). Social movements in Taiwan’s democratic transition: linking activists to the changing political environment. 1st Edn. New York: Routledge.

Fariss, C., Kenwick, M., and Reuning, K. (2020). Latent Human Rights Scores Version 4. Version 3.0. Harvard Dataverse.

Feigenbaum, E., and Popova, A. (2024) How Taiwan’s young techies fight political disinformation. Politics Possible. June 30. 50:12 Available online at: https://www.politicspossible.com/how-taiwans-young-techies-fight-political-disinformation

Gallina, M., Camatarri, S., and Luartz, L. A. (2025). Populist voting beyond Western borders? Populist attitudes and electoral behaviour in East Asia. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2025.2570376

Geddes, B., Wright, J., and Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: a new data set. Perspect. Polit. 12, 313–331. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714000851

Goebel, C. (2016). The quest for good governance: Taiwan’s fight against corruption. J. Democr. 27, 124–138. doi: 10.1353/jod.2016.0006

Gordon, P. H., and Hass, R. (2025). Nobody lost Taiwan. Foreign Aff. September 22. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/nobody-lost-taiwan

Gorokhovskaia, Y., and Grothe, C. (2025) Freedom in the world 2025: the uphill battle to safeguard rights Freedom House. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2025/uphill-battle-to-safeguard-rights

Green, M., and Twining, D. (2024). The strategic case for democracy promotion in Asia. Foreign Affairs. January 23. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/strategic-case-democracy-promotion-asia

Greitens, S. C. (2016). Dictators and their secret police: coercive institutions and state violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gubbala, S., and Fetterolf, J. (2024) Support for democracy is strong in Hong Kong and Taiwan Pew Research Center, March 19. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/03/19/support-for-democracy-is-strong-in-hong-kong-and-taiwan/

Hass, R. (2025) Taiwan President Lai’s Three Big Challenges in 2025. Brookings, February 12. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/taiwan-president-lais-three-big-challenges-in-2025/

Hioe, B. (2025). Taiwan’s great recall movement is officially over. The Diplomat, August 25. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2025/08/taiwans-great-recall-movement-is-officially-over/.

Ho, M.-S. (2019). Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven: Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Hood, S. J. (1996). Political change in Taiwan: the rise of Kuomintang factions. Asian Surv. 36, 468–482. doi: 10.2307/2645494

Hsieh, J. F.-S. (2001). Whither the Kuomintang? China Q. 168, 930–943. doi: 10.1017/S0009443901000547

Hsu, E. (2024) 2024 Taiwan Election: the increasing polarization of taiwanese politics — reinforcement of conspiracy narratives and cognitive biases. Doublethink Lab, April 8 Available online at: https://medium.com/doublethinklab/2024-taiwan-election-the-increasing-polarization-of-taiwanese-politics-reinforcement-of-2e0e503d2fe2

Huang, A. (2024). “Combatting and defeating Chinese propaganda and disinformation: a case study of Taiwan’s 2020 elections” in State-Sponsored Disinformation around the Globe, Martin Echeverría, Sara García Santamaría, Daniel C. Hallin editors. (New York: Routledge).

Hur, A., and Yeo, A. (2024). Democratic ceilings: the long shadow of nationalist polarization in East Asia. Comp. Polit. Stud. 57, 584–612. doi: 10.1177/00104140231178724

Iyengar, Rishi. (2024). How China Exploited Taiwan’s election—and what it could do next. Foreign Policy, January 23. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/23/taiwan-election-china-disinformation-influence-interference/.

Katsiaficas, G. N. (2013). Asia’s Unknown Uprisings. Volume 2: People Power in the Philippines, Burma, Tibet, China, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Thailand, and Indonesia, 1947–2009.

Khrestin, I. (2024) Supporting Taiwan’s democracy is essential to global security. George W. Bush Presidential Center, November 8 Available online at: https://www.bushcenter.org/publications/supporting-taiwans-democracy-is-essential-to-global-security/

Kuo, R. (2023) ‘Strategic ambiguity’ may have U.S. and Taiwan trapped in a Prisoner’s Dilemma. RAND Corporation, January 18 Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2023/01/strategic-ambiguity-may-have-us-and-taiwan-trapped.html

Kuo, R. (2024). Why Taiwan’s voters defied Beijing—again. J. Democr. Available online at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/elections/why-taiwans-voters-defied-beijing-again/.

Kuo, R. (2025). Taiwan’s risky no-holds-barred politics. J. Democr. Available online at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exclusive/taiwans-risky-no-holds-barred-politics/.

Kuo, Raymond, Hunzeker, Michael, and Christopher, Mark A. (2024a) Getting Serious About Taiwan. RAND Corporation, May 23 Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/05/getting-serious-about-taiwan.html

Kuo, R., Hunzeker, M., and Christopher, M. A. (2024b). Scared strait. Foreign Aff. March/April 2024 (February). Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/scared-strait

Kuo, R., and Kish, C. (2025). Taiwan’s Will to Fight Isn’t the Problem. War on the Rocks, September 5. Available online at: https://warontherocks.com/2025/09/taiwans-will-to-fight-isnt-the-problem/.

Kuo, Naiyu, and Staats, Jennifer (2024) Taiwan’s Democracy Prevailed Despite China’s Election Interference. United States Institute of Peace, January 24. Available online at: https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/01/taiwans-democracy-prevailed-despite-chinas-election-interference

Kurlantzick, J. (2019) How China Is Interfering in Taiwan’s Election. Council on Foreign Relations, November 7 Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/how-china-interfering-taiwans-election

Lai, E. Y. (2025). Trump’s Approach to Taiwan Is Taking Shape. The Diplomat, October 4. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2025/10/trumps-approach-to-taiwan-is-taking-shape/.

Lee, J. (2020). US grand strategy and the origins of the developmental state. J. Strateg. Stud. 43, 737–761. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2019.1579713

Levine, B. (2025) Leveraging legislative power: the KMT’s strategy to regain influence in Taiwan/Part 2: the weakening of political accountability. Global Taiwan Institute, February 5. Available online at: https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/02/leveraging-legislative-power-the-kmts-strategy-to-regain-influence-in-taiwan-part-2/

Levitsky, S., and Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Problems of international politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lin, B., Culver, J., and Hart, B.. (2025). The risk of war in the Taiwan Strait is high—and getting higher. Foreign Aff. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/risk-war-taiwan-strait-high-and-getting-higher.

Lührmann, A., and Lindberg, S. I. (2019). A third wave of autocratization is here: what is new about it? Democratization 26, 1095–1113. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029

Martin, D. A., Jacob, N. S., and Ilhardt, J. G. (2023). Introducing the online political influence efforts dataset. J. Peace Res. 60, 868–876. doi: 10.1177/00223433221092815

Mattis, P., and Yu, C. (2025). Chinese communist party covert operations against Taiwan : Global Taiwan Institute. Available online at: https://globaltaiwan.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/OR_CCP-Covert-Operations-Against-TW.pdf

Mien-chieh, Yang, and Hetherington, William. (2024). Taiwan Most Affected by Disinformation. Taipei Times, March 25. Available online at: https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2024/03/25/2003815440.

Moyer, J. D., Meisel, C. J., and Matthews, A. S. (2024) Foreign Bilateral Influence Capacity Index Codebook, Version 3.6. Frederick S. Pardee School for International Studies, University of Denver, October

Nachman, Lev, and Yen, Wei-Ting. (2025). Taiwan’s democracy is in trouble. Foreign Aff., Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/taiwans-democracy-trouble.

Niven, T. (2024). How Taiwan should combat China’s information war. J. Democr., Available online at: https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exclusive/how-taiwan-should-combat-chinas-information-war/.

Nord, M., Angiolillo, F., Good God, A., and Lindberg, S. I. (2025). State of the world 2024: 25 years of autocratization–democracy trumped? Democratization 32, 839–864. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2025.2487825

Office of the President Republic of China (Taiwan) (2025) President Lai Delivers 2025 National Day Address. October 10 Available online at: https://english.president.gov.tw/News/7022

Paulson, J. (2024) Towards a more equal equality: LGBTQ+ rights in Taiwan’s post-2019 political landscape. Global Taiwan Institute, June 12. Available online at: https://globaltaiwan.org/2024/06/towards-a-more-equal-equality-lgbtq-rights-in-taiwans-post-2019-political-landscape/

Quirk, S. (2021). Lawfare in the disinformation age: Chinese interference in Taiwan’s 2020 elections. Harv. Int’l LJ 62:525.

Reuters. (2024). Taiwan warns defence could suffer under opposition’s funding laws. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/taiwan-warns-defence-could-suffer-under-oppositions-funding-laws-2024-12-23/.

Reuters. (2025a). China ‘clearly’ trying to interfere in Taiwan’s Democracy, Taipei says before recall vote. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-clearly-trying-interfere-taiwans-democracy-taipei-says-before-recall-vote-2025-07-23/.

Reuters. (2025b). Taiwan president warns of China’s ‘Infiltration’ Effort, Vows Countermeasures. The Straits Times (Singapore), Available online at: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/taiwan-president-warns-of-chinas-infiltration-effort-vows-counter-measures.

Robertson, N. (2024). How DC became obsessed with a potential 2027 Chinese invasion of Taiwan. Def. News, Available online at: https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2024/05/07/how-dc-became-obsessed-with-a-potential-2027-chinese-invasion-of-taiwan/.

Sacks, D. (2024). Taiwan’s democracy is thriving in China’s Shadow. Council on Foreign Relations, Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/blog/taiwans-democracy-thriving-chinas-shadow.

Shen, Chenxi (2024) What do the Taiwanese really need? Unfolding Public Sentiment Amidst Taiwan’s Emerging Populist Politics. Global Taiwan Institute. Available online at: https://globaltaiwan.org/2024/05/what-do-the-taiwanese-really-need-unfolding-public-sentiment-amidst-taiwans-emerging-populist-politics/

Sher, C.-Y., Pien, C.-P., O’Reilly, C., and Liu, Y.-H. (2024). In the name of Mazu: the use of religion by China to intervene in Taiwanese elections. Foreign Policy Anal. 20:orae009. doi: 10.1093/fpa/orae009

Shu-ling, K. (2023) Taiwan on the frontline of China’s information operations. Power 3.0: Understanding Modern Authoritarian Influence, September 12. Available online at: https://www.power3point0.org/2023/09/12/taiwan-on-the-frontline-of-chinas-information-operations/

Slater, D., and Wong, J. (2022). “Taiwan: the exemplar of democracy through strength” in From development to democracy: the transformations of modern Asia (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

So, A. Y., and Hua, S. (1992). Democracy as an antisystemic movement in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China: a world systems analysis. Sociol. Perspect. 35, 385–404. doi: 10.2307/1389385

Taylor, J. (2000). The Generalissimo’s Son: Chiang Ching-Kuo and the Revolutions in China and Taiwan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Templeman, K. (2020). How Taiwan stands up to China. J. Democr. 31, 85–99. doi: 10.1353/jod.2020.0047

Templeman, K. (2022). How democratic is Taiwan? Evaluating twenty years of political change. Taiwan Journal of Democracy 18, 1–24.

Templeman, K. (2025a) Taiwan after the great recalls: toward a new political equilibrium? Brookings, August 15 Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/taiwan-after-the-great-recalls-toward-a-new-political-equilibrium/

Templeman, K. (2025b). Taiwan is on the brink of a constitutional crisis. Kharis Templeman (祁凱立), January 19. http://www.KharisTempleman.com/1/post/2025/01/taiwan-is-on-the-verge-of-a-constitutional-crisis.html.

Thompson. (2024). Whole-of-society resilience: a new deterrence concept in Taipei. Brookings, December 6. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/whole-of-society-resilience-a-new-deterrence-concept-in-taipei/.

Tien, H.-M. (1996). Taiwan in 1995: electoral politics and cross-strait relations. Asian Surv. 36, 33–40. doi: 10.2307/2645553

Treisman, D. (2015). Income, democracy, and leader turnover. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 927–942. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12135

Tsai, I.-W. (2021). Taiwan and the fight for democracy: a force for good in the changing international order. Foreign Aff. 100, 74–84.

Tsui, Y. (2012) ‘Wild Strawberries’ are the future. Taipei Times, December 14. Available online at: https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2012/12/14/2003550093

Vogt, M., Bormann, N.-C., Rüegger, S., Cederman, L.-E., Hunziker, P., and Girardin, L. (2015). Integrating data on ethnicity, geography, and conflict: the Ethnic Power Relations data set family. J. Confl. Resolut. 59, 1327–1342. doi: 10.1177/0022002715591215

Wang, A. H.-E. (2017). The waning effect of China’s carrot and stick policies on Taiwanese people: clamping down on growing national identity? Asian Surv. 57, 475–503. doi: 10.1525/as.2017.57.3.475

Whiton, C. (2025). How taiwan lost trump. Domino Theory. Available online at: https://dominotheory.com/how-taiwan-lost-trump/.

Wiebrecht, F. (2022) Dissemination of false information abroad. Varieties of Democracy. Available online at: https://v-dem.net/weekly_graph/dissemination-of-false-information-abroad

Wike, R. (2025). Why the world is down on democracy. J. Democr. 36, 93–108. doi: 10.1353/jod.2025.a947886

Wilson, K. L. (2022). Strategic responses to Chinese election interference in Taiwan’s presidential elections. Asian Perspect. 46, 255–277. doi: 10.1353/apr.2022.0011

World Values Survey. (2025) WVS Database. Available online at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp.

Wright, J. (2021). The latent characteristics that structure autocratic rule. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 9, 1–19. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2019.50

Wu, Y. (2019). Recognizing and resisting China’s evolving sharp power. Am. J. Chin. Stud. 26, 129–153. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45216268

Wu, D. (2025). Assessing China’s Cognitive Warfare against Taiwan on TikTok. SPF China Observer. Available online at: https://www.spf.org/spf-china-observer/en/document-detail064.html.

Yan, I. (2025) How to control what you cannot have: China’s strategic use of disinformation to undermine taiwanese democracy. Featured. Democratic Erosion Consortium. Available online at: https://democratic-erosion.org/2025/05/06/how-to-control-what-you-cannot-have-chinas-strategic-use-of-disinformation-to-undermine-taiwanese-democracy-by-isabella-yan/

Yarhi-Milo, K., Lanoszka, A., and Cooper, Z. (2016). To arm or to ally? The patron’s dilemma and the strategic logic of arms transfers and alliances. Int. Secur. 41, 90–139. doi: 10.1162/ISEC_a_00250

Keywords: Taiwan, democratic David, sharp power, east Asian democracy, Asian values

Citation: Chin JJ and Rector S (2025) Taiwan: democratic David in 21st century east Asia. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1631545. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1631545

Edited by:

Christo Karabadjakov, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, GermanyReviewed by:

Brian Christopher Jones, University of Liverpool, United KingdomKharis Templeman, Stanford University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Chin and Rector. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John J. Chin, ampjaGluQGFuZHJldy5jbXUuZWR1

John J. Chin

John J. Chin Staten Rector

Staten Rector