- 1Department of Government and Politics, Diponegoro University, Semarang, Indonesia

- 2Research Center for Politics, National Research and Innovation Agency of the Republic of Indonesia (BRIN Indonesia), Jakarta, Indonesia

In terms of ideology, contemporary political parties in Indonesia can no longer be easily categorized as either Islamic or secular nationalist parties. Political parties are currently aligned with the Pancasila ideology. Using a qualitative approach that includes interviews with party elites at both the central and provincial levels— and applying variables that differ from those used in traditional dichotomous classifications of political party ideologies—this study demonstrates that there has been a convergence of Islamic and national values within political parties in Indonesia. This convergence is evident in two aspects: value infusion, reflected in the content of cadre training materials, and political behavior, which can be seen from implementation or articulation of an ideology, including those related to the party’s vision or mission. Therefore, it can be concluded that, at present, no political party exclusively prioritizes either the national or the religious dimension. However, this does not mean that all political parties occupy the same ideological position. Gradations among them can still be observed, although not in a dichotomous manner, with parties distributed along a continuum from the extreme left to the extreme right.

1 Introduction

Scholars have long debated the issue of how to construct the convergences and typologies of political parties since the beginning of Indonesia’s independence, which has been characterized by a dichotomy between Islamic and nationalist parties (Feith and Castles, 1970; Geertz, 1960). In the New Order era and afterward, several studies updated these works, adding variables that differ from their predecessors (Aspinall et al., 2018; Baswedan, 2004; Dhakidae, 1999; Evans, 2003; Lanti, 2004; Noer, 1988; Ufen, 2006). These additional variables actually suggest that the typology constructed by Geertz or Feith and Castles (1970) is no longer adequate to capture the ideology of political parties. However, the conclusions of the new studies still tend to clearly separate the ideological tendencies of the political parties by contrasting the Islamic and nationalist parties. Even the recent survey-based study conducted by Aspinall et al. (2018) still indicated the positioning of parties as either “right-wing” or “left-wing” and whether they are based on Islamic principles or non-Islamic ones, which they defined as Pancasila.

In addition, the term “nationalist parties” sometimes refers to Pancasialist parties with a secular tendency. This includes parties such as the National Democrat Party (Nasdem), the Indonesia Democratic Party-Struggle (PDIP), the Greater Indonesia Movement (Gerindra), the Functional Group Party (Partai Golkar), and the Democratic Party (Demokrat). In reality, they do not avoid religious values; they recognize, respect, and value the existence and role of religion in political life. On the other hand, the term “Islamist parties” refers to the National Mandate Party (PAN), the National Awakening Party (PKB), the United Development Party (PPP), and the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), which are also problematic because they do not reject values outside Islam and respect pluralism.

Challenging previous studies, this article argues that, at the ideological level, Indonesia’s political parties exhibit broad convergence in their recognition of Pancasila as the nation’s philosophical foundation. Pancasila consists of five pillars or principles, namely (1) Belief in One Almighty God, (2) Just and Civilized Humanity, (3) The Unity of Indonesia, (4) Democracy, and (5) Social Justice for all Indonesians. However, divergent interpretations of Pancasila, along with varying emphases on particular values or ideological tenets, have produced distinct orientations that reflect enduring ideological differentiation within a shared Pancasila framework. Against this background, the study aims to develop a new understanding of the convergence of Indonesian political party ideologies toward Pancasila and to map the varying degrees of alignment among them.

The authors do not classify Pancasila as a secular or non-Islamic principle; instead, they emphasize its composite nature, which encompasses both religious and nationalist values. Moreover, Pancasila is also related to the belief in pluralism, which has its foundation in the second and third pillars. Pluralism has a strong foundation in a pluralistic country such as Indonesia, which comprises hundreds of ethnic groups and six major religions. The Pancasila orientation was systematically examined by the BRIN political party research team in a study conducted in 2022. Employing a neo-institutionalist approach, the team analyzed the statutes (AD/ART) of the nine political parties that participated in the 2019 elections and concluded that both parties, those conventionally categorized as nationalist and those identified as Islamic, are uniformly oriented toward Pancasila.

In this article, the authors emphasize that Pancasila is not only codified as a party principle—a legal prerequisite for the establishment of political parties in Indonesia—but also that its principles have been translated into the values, objectives, rationales for party formation, and the broader direction of political struggle. Accordingly, contemporary political parties may be more precisely categorized as “Pancasila-Oriented Nationalist Parties” (Nasdem, PDIP, Gerindra, Golkar, and Demokrat) and “Pancasila-Oriented Islamist Parties” (PAN, PKB, PKS, and PPP).

The former category does not entirely exclude religious values from its political orientation but acknowledges them in a more limited manner than the latter. These parties thus demonstrate a strong commitment to the concept of nationality, emphasizing and reinforcing national values without positioning themselves as secular, let alone anti-religious. They also cultivate amicable relationships with religious organizations. Within this framework, a nuanced spectrum of ideological perspectives emerges concerning the role of religion in the political sphere.

The “Pancasila-Oriented Islamist Parties” advance a substantive conception of Islamic politics, whereby Islamic values are articulated within the framework of the nation-state. While affirming the significance of national values and the enduring relevance of Pancasila, these parties position Islam as the central foundation of their political ideology, drawing support primarily from Islamic communities and mass organizations. Their orientation underscores the necessity of grounding politics in Islam without promoting either the formalization of Islamic teachings or the establishment of an Islamic state. At the same time, they embrace nationalism and Pancasila while opposing efforts to institutionalize Pancasila through state mechanisms, which they regard as a potential source of ideological standardization. This stance reflects a dual commitment: acknowledging the political role of Islam while resisting its reduction to a rigid ideological doctrine.

To test the argument, the authors used two variables: (1) value infusion and (2) political behavior. These variables are derived from studies on the institutionalization of political parties (Randall and Svåsand, 2002) and on the relationship between ideology and political behavior (Minar, 1961).

Value infusion is defined as the process of instilling and disseminating the values or ideologies upheld by a party to its cadres, comprising a set of principles considered ideal for shaping the political and social order of the state. It is closely linked to efforts aimed at fostering awareness of the party’s adopted ideology (Randall and Svåsand, 2002). In the Indonesian context, political parties conduct specific activities designed to shape cadres so that they embody the party’s identity both in appearance and, more importantly, in ideology. In practice, value infusion is most evident in cadre formation programs, which encompass orientation, education, socialization, and evaluation processes centered on the party’s values and ideology (Noor, 2015).

Regarding cadre formation activities, the authors focus on how cadre formation material for each political party—especially that related to the position and interpretation of Pancasila and each party’s beliefs in the values, perspectives, or ideologies it adheres to—is infused into all cadres. Thus, the indicator of the value infusion variable is the substance of the cadre formation material delivered to the cadres. The ideological spectrum built is based on the weight of national and religious material in the cadre formation material provided. Parties with a large weight of national material in their cadre formation will be placed in a diametrically different position from parties that prioritize religious material. Meanwhile, middle parties tend to combine the two in a relatively balanced manner.

In the second variable, the tendency of the political behavior variable can be seen as a form of implementation or articulation of an ideology, including those related to the party’s vision or mission. According to Minar (1961), political behavior serves as a more expressive and frequently direct form of explanation of the party’s ideology, which is more empirical than normative. This political behavioral aspect can be observed in several ways, for example, through party manifestos, behavior in the electoral context, or attitudes expressed during the policy-making process. Therefore, studies on these matters are often conducted to record and measure the ideological positions or distances of political parties (Abduljaber, 2018; Andrews, 2003; Budge and Laver, 1986; Evans et al., 1996; Jackle and Timmis, 2023).

This article explores political behavior by examining the internal policies of political parties that support the implementation of Pancasila values, the parties’ stances on specific issues or public policies, and their organizational structures, including wing organizations. A party’s alignment with a certain behavior, based more on national values or perspectives, places it in a diametrically opposite position to parties whose alignments are based more on religious values or perspectives. Middle or intermediate positions are held by parties that combine values and perspectives, a mixture of nationality and religion, with various gradations.

This article is structured as follows. The first section presents the arguments and variables, followed by the data and methods. The third section discusses parties’ convergence on Pancasila values, while the fourth maps Indonesian political party ideologies in relation to Pancasila. The conclusion argues that, although no party emphasizes solely the national or religious dimension, they do not occupy the same position; rather, their differences form identifiable gradations short of a strict left–right dichotomy.

2 Materials and methods

This study employs a qualitative-explanatory research methodology to develop a new understanding of the convergence of Indonesian political party ideologies toward Pancasila and to map the degrees of variation among them. The primary data for this study were obtained through interviews with five members of the party’s Central Committee in Jakarta, seven members of the Regional Committee in Padang (West Sumatra), and nine members of the Regional Committee in Yogyakarta.

The secondary data were also obtained through a comprehensive examination of each party’s Anggaran Dasar/Anggaran Rumah Tangga (Party Statutes/AD/ART) and derivative regulations, documents, syllabuses, curricula, and guidebooks related to political education for cadres.

To further enrich the analysis and situate the findings within a broader scholarly and sociopolitical context, the study also incorporated a comprehensive review of relevant literature, prior studies, and media sources. This included both written publications and audio content, such as podcasts, which were analyzed to deepen the understanding of the political parties’ ideological convergences toward Pancasila, as seen from the two variables tested.

The qualitative data analysis technique proposed by Miles and Huberan (2014) was employed in this study, consisting of three main steps. First, data reduction involved systematically sorting and focusing on relevant information derived from the review of party regulations concerning political education for cadres, the party’s structure, interview transcripts, and other supplementary data from relevant literature, prior studies, and media sources. The integrated dataset was then subjected to thematic coding, resulting in three major initial codes: nationalist and religious values in political education for cadres, the role of religious wing organizations, and political parties’ statements regarding Pancasila values. These codes informed the development of the final themes and an interpretive framework that links formal regulatory provisions with the lived realities of party politics, ensuring both conceptual robustness and empirical grounding. This step ensured that only the data pertinent to the study’s objectives were retained.

Second, data presentation, where the data were organized, categorized, and described systematically to facilitate comprehensive analysis. Finally, drawing conclusions involved identifying the key factors that contributed to the shortcomings of the convergence of Pancasila values within Indonesian political parties today. These conclusions were framed within the broader theoretical context of value infusion and the political behavior of political parties, allowing for a mapping of the ideological convergence towards Pancasila.

This study has received approval from the Social Humanities Research Ethics Commission of BRIN. The study was granted ethics clearance under decision number: 082/KE.01/SK/04/2023. Furthermore, both written and verbal informed consent have been obtained from all participants for the publication of this study. We confirm that this article complies with national laws regarding consent and privacy.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Pancasila-oriented nationalist parties

3.1.1 Ideological values as party characteristics

The category of Pancasila-oriented nationalist parties includes Nasdem, PDIP, Gerindra, Golkar, and Demokrat. While united by their orientation toward Pancasila, each party demonstrates distinctive emphases in its statutes, cadre formation processes, and political education institutions.

In the case of Nasdem, its strong nationalist spirit is reflected in the cadre formation system, which is carried out through political education at the Akademi Bela Negara (ABN, State Defence Academy). Established in 2017, ABN functions as a political school aimed at preparing party cadres who are patriotic, committed to protecting the integrity of the Republic of Indonesia, upholding Pancasila as the state ideology, and embracing Indonesia’s diversity (YouTube Channel ABN Nasdem, 2018).

The ABN curriculum emphasizes three core dimensions. The first, the personality dimension, provides the foundation for shaping cadres’ psychological orientations and individual dispositions. It seeks to enhance cadres’ cognitive understanding of the party’s role in national political dynamics, encompassing knowledge of party history, party ideology, and the broader political, electoral, and party systems. The focus on national values aims to instill confidence in cadres to advance the ideals of the Indonesian nation through the movement for change (Akademi Bela Negara Nasdem, n.d.). Instruction on patriotism, Pancasila ideology, the Constitution, and pluralism exemplify this dimension.

In addition, ABN offers short-course programs, including a legislative school, political education for policy experts, and training for party administrators at various levels. These programs cover topics such as nationalism, the history and values of Nasdem, and the practice and formulation of political policies (ABK, 2023). They also reinforce the party’s commitment to revitalizing Pancasila as the nation’s ideology, realizing the aspirations of independence articulated in the Preamble to the 1945 Constitution, and advancing economic sovereignty and self-reliance in energy and natural resources (Partai Nasdem, 2012).

PDIP, which explicitly designates Pancasila as its foundational principle, identifies itself as a national, populist, and social justice-oriented party (PDIP, 2019). This orientation is reflected in its cadre formation materials, which emphasize national and party ideology, incorporating both core and supplementary teachings. Much of the party’s ideological foundation derives from Soekarno’s thought, including Indonesia Menggugat (Indonesia Contested, 1930), Mencapai Indonesia Merdeka (Achieving Independent Indonesia, 1933), and The Birth of Pancasila (June 1, 1945) (PDIP, 2019).

The inclusion of ideological content in cadre formation reflects the party’s commitment to the values once articulated by Soekarno, Indonesia’s first president, through his writings as well as secondary sources documenting his ideas (AHP, 2023). Notably, PDIP does not provide specific religious teachings or materials within its cadre training. However, the party allows each cadre the freedom to worship according to their respective faiths (AHP, 2023; NYD, 2023).

The Gerindra Party, which originally emerged as a “faction” of Golkar, Fionna (2016) defines its identity and character as a Pancasila-based nationalist party. Its cadre education materials strongly emphasize nationalism, reinforced by a cadre oath. Gerindra considers cadres’ comprehension of nationalist values a key prerequisite for advancing their political careers. To qualify as party officials, cadres must demonstrate their loyalty and understanding of national values through active participation in the party’s wing organizations (RSD, 2023).

Gerindra’s cadre formation materials place Pancasila at the core of instruction, as stipulated in the party’s statutes (AD/ART) and platforms. Alongside Pancasila, the curriculum highlights the party’s nationalist identity, articulated in the Gerindra Struggle Manifesto (Partai Gerindra, 2008), and further elaborated in Prabowo Subianto (2017), which outlines perspectives on the economic system and the Democracy-Pancasila concept. Three central themes in cadre education reinforce national values: (1) Pancasila, the 1945 Constitution, and the ideals of the Proclamation of Independence; (2) Indonesia’s archipelagic vision; and (3) national and state defense.

The party’s emphasis on nationalism also extends to practical training activities designed to foster patriotic attitudes. For example, cadres sing the national anthem, “Indonesia Raya,” before meals (GTR, 2023). Cadres who become members of parliament continue to receive nationalist-oriented materials through discussion forums that address themes such as patriotism, the history of Indonesia’s founding fathers, the struggle for independence, and the 1998 reforms (HDY, 2023).

In Golkar, cadre formation materials are closely tied to the party’s ideology, as regulated in its statutes (AD/ART), with Pancasila positioned as the central principle. Pancasila not only serves as the foundation for cadre training but also underpins the party’s broader national concepts and values. According to informants, the goal of cadre formation is to produce “national cadres”—individuals who demonstrate achievement, dedication, loyalty, and integrity in service to the nation and the state, rather than merely to the party. In this regard, Golkar presents itself as an institutionalized party operating within a system, rather than relying on charismatic figures or personal networks (NZR, 2023).

The emphasis on nationalist values permeates all types and stages of Golkar’s cadre formation, from programs implemented by party wings and affiliated organizations to territorially based training such as Karakterdes (village/sub-district), structural cadres (district/city, provincial, national), and functional cadres (Karsinal), which include teachers, workers, and farmers (Fitriyah, 2020; NZR, 2023). Training begins with foundational materials, including Pancasila, the 1945 Constitution, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity), and national insight, before moving on to party-specific content, such as Golkar’s ideological commitment to Pancasila (NZR, 2023). The overall curriculum emphasizes nationalist values through discussions and activities designed to cultivate an understanding of the welfare state, which Golkar interprets as a key expression of Pancasila (NZR, 2023).

Unlike other nationalist parties, the Demokrat Party officially enshrines a nationalist-religious ideology—comprising nationalist and religious moral insights—along with humanist and pluralist values in its AD/ART. However, its interpretation of religiosity differs from that of explicitly religious parties, which are based on a particular faith (e.g., Islam) and are often assumed to pursue the formal implementation of religious values. Instead, the Demokrat Party emphasizes the substantive spirit of practicing religious teachings. This written affirmation of a nationalist-religious ideology positions Demokrat at the ideological center among nationalist parties, as reflected in its statutes.

The Demokrat Party also established a specialized political education institution, the Demokrat Academy. Its first cohort was trained as campaign teams for legislative candidates in the 2018 simultaneous regional elections. The materials provided during cadre formation primarily consist of general knowledge, focusing on an understanding of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia, Pancasila, national insight, party principles, and universal religious values (DN, 2023). Similar training is also conducted at the regional level, typically through meetings or dialog (DN, 2023). From this, it can be inferred that the Demokrat Party’s cadre formation curriculum is relatively fluid and pragmatic, adapting to political developments while seeking to instill a universal religious nuance. Importantly, religious values are emphasized less as doctrinal content than as principles to be applied within political practice (IM, 2023).

Taken together, these parties demonstrate a shared orientation toward Pancasila, but their cadre formation practices highlight distinctive emphases: Nasdem’s structured civic-patriotic training, PDIP’s reliance on Soekarno’s ideological legacy, Gerindra’s patriotic-nationalist oath and practices, Golkar’s systematized national cadre strategy with localized religious outreach, and Demokrat’s integration of universal religious values within a nationalist framework. These differences reveal important nuances in how nationalism and religiosity are operationalized within Indonesia’s Pancasila-oriented nationalist parties.

3.1.2 Not secular parties: respecting religious norms as part of Pancasila

Although the value infusion variable—reflected in the cadre training materials of the five parties discussed above—emphasizes national values over religious values, these Pancasila-oriented nationalist parties do not entirely abandon religion in their political behavior. From the behavioral variable—reflected in internal party policies, programs, organizational wings, and positions toward public policy or political situations—all five parties continue to take religious values into account. This suggests that the Pancasila orientation, which embodies the convergence of national and religious values, is also present in parties often labeled as strictly nationalist.

In the case of NasDem, although the nationalist nuance is more pronounced, the party maintains close ties with Muslim communities. Aspinall and Mietzner (2019) note that NasDem and other nationalist parties are accommodating toward Muslim aspirations to preserve political consensus. Such accommodating attitudes correspond to the needs of constituents. Party Chair Surya Paloh once stated that NasDem accepts the implementation of perda syariah (Islamic bylaws) in Aceh but considers them unnecessary elsewhere (Nasdem, 2018). This reflects that NasDem’s support remains consistent with its nationalist identity while recognizing Aceh’s special status and Islamic norms.

NasDem’s Islamic orientation is not formalized through religious organizational wings. Instead, the party portrays itself as inclusive of Islamic values, for instance, through the slogan “politik tanpa mahar” (“politics without dowry”) (Aditya, 2016), which resonates with Islamic ethics. Surya Paloh frequently employs religious moral narratives to reinforce political messages, such as “grounding Islam as rahmatan lil ‘alamin’” (Partainasdem.id, 2018). He has also repeatedly affirmed that NasDem embraces a “nationalist-religious” ideology (Nasdemdprri.id, 2018).

Similarly, PDIP—though strongly nationalist—has also supported perda syariah in several regions, particularly as Islamic political discourse strengthened after the New Order. Buehler (2013) found that PDIP and Golkar were among the strongest advocates of perda syariah. PDIP’s central leadership emphasized that the implementation of Islamic law should not undermine the foundations of the state (Tempo.co, 2003).

At the national level, the PDIP has supported several Islamic-oriented laws, including the Law on Zakat (Law 23/2011), the Law on Islamic Banking (Law 23/2008), and the Law on Waqf (Law 41/2004) (Hukumonline.com, 2021). Moreover, PDIP maintains an official religious wing, Baitul Muslimin Indonesia (the Indonesian Muslimin Home). Thus, especially in the post-New Order period, ideological contestation in Indonesia has shifted toward “religious nationalism.” PDIP also projects itself as both nationalist and religious (Bourchier, 2019; Pdiperjuangan-jatim.com, 2017). While formally a nationalist party (Aspinall et al., 2020; Ufen, 2008), its political behavior is accommodating toward Muslim aspirations (Aspinall et al., 2015; Bourchier, 2019).

Golkar, often analyzed through a secular-nationalist paradigm (Tomsa, 2010; Ufen, 2008), has in practice developed an institutionalized framework to accommodate religious values. This is pursued not merely through ceremonial programs but through the formal establishment of religious organizational wings. Research indicates that these internal policies play a crucial role in strengthening organizational identity, fostering internal cohesion, and gaining electoral legitimacy in Indonesia’s religiously oriented society (NZR, 2023). This challenges the secularist view of Golkar and provides new insights into how Pancasila-based parties structurally incorporate religion.

In Golkar’s internal policies, the teaching of national values is not treated as antithetical to religiosity. Instead, the party officially accommodates religious expression as part of Pancasila, particularly the first principle: belief in One Almighty God. The clearest example of this is the recognition of religious wings within the party. Golkar not only has a Bureau of Religious Affairs but also formally affiliates organizations, such as Majelis Dakwah Islamiah, at both the central (Deni, 2022) and regional levels (DPD Partai Golkar Provinsi Riau, 2025). These religious wings are not loosely affiliated entities but are integral to Golkar’s organizational ecosystem, bound by its AD/ART. This formal institutionalization reflects a structural policy designed to channel religious capital into organizational consolidation (Hamayotsu, 2011).

Gerindra also integrates religious values into its nationalist platform. Regarding religion, Gerindra considers it a matter of personal belief rather than an element of cadre training. Religious instruction is not formally included; instead, religion is acknowledged as complementary, with Islam viewed as rahmatan lil-‘alamin (a mercy to the universe) (GTR, 2023). Its official vision emphasizes national welfare, social justice, and political order rooted in both nationalism and religiosity (Partai Gerindra, 2020). This is operationalized through religious wings, such as Gerakan Muslim Indonesia Raya (GEMIRA), which advances Muslim aspirations through educational, economic, and socio-religious programs (Fraksigerindra.id, 2024). GEMIRA emphasizes that politics and religion should always coexist, as religion guides political ethics (Khalida, 2024).

This positioning is closely linked to Prabowo Subianto’s influence. His leadership has enabled Gerindra to navigate national politics more effectively (Suryaningtyas, 2025). After its victory in the 2024 presidential election, Gerindra adopted a centrist stance, seeking alliances with diverse political actors (Suryaningtyas, 2025). Between 2009 and 2019, Gerindra’s politics leaned toward the “center-left” with a socialistic orientation (Suryaningtyas, 2025). At the same time, Gerindra has formed an alliance with Islamist parties in parliament while maintaining a nationalist rhetoric (Bourchier, 2019).

Similarly, the Demokrat Party also combines nationalism and religion. From its inception, the party’s doctrine promoted nationalism, humanism, and pluralism (Honna, 2012). However, it also explicitly embraces a nationalist-religious ideology in its AD/ART (Partai Demokrat, 2020). This ideology seeks to reconcile nationalism with religion in a constructive way, rejecting any dichotomy between the two (Partai Demokrat, 2020).

Demokrat thus adopts a “middle path”—neither a religious party nor a secular one (Mentari, 2018). This allows it to appeal to both religious and nationalist voters (Mentari, 2018). While it lacks formal religious wings, the party engages in religious outreach such as Ramadan Safari events in 2021, where leaders met with ulama and cadres (Jemali, 2021). Demokrat elites also frequently attend Islamic study circles (Demokrat.or.id, 2025).

In summary, in their political behavior, nationalist parties present themselves as religiously accommodating, particularly toward Islam. They increasingly align with religious agendas to secure broader public support (Nurjaman, 2023). This approach reflects a global trend among catch-all parties in religious societies, which establish religious wings to consolidate support from pious voters without altering their core platforms (Künkler and Lerner, 2016). This illustrates the intricate dynamics of religion and politics in Indonesia, where the incorporation of religion has become a strategic organizational approach for nationalist parties based on the Pancasila ideology.

3.2 Pancasila-oriented Islamic parties

3.2.1 Ideological value tendencies

After identifying the convergence of nationalist and religious values within parties traditionally regarded as strictly nationalist—both in terms of value infusion and political behavior—it becomes evident that such convergence is not limited to nationalist parties alone. A similar pattern is also discernible among Pancasila-oriented Islamic parties, namely PAN, PKB, PPP, and PKS. While these parties retain Islamic values with greater emphasis than those in the first category, they nonetheless accommodate and affirm nationalist values through Pancasila. This dual orientation highlights the extent to which Pancasila operates as a shared ideological framework, within which both nationalist and Islamic parties negotiate and articulate their respective political identities.

In the case of PAN, it is categorized as a religious-nationalist party because its mass base consists largely of Muslim voters; however, it does not seek to formally implement Islamic religious values. PAN is informally linked to one of the largest Islamic mass organizations in Southeast Asia, with approximately 30 billion members, Muhammadiyah, primarily through Amien Rais—former chairman of Muhammadiyah and the key figure in PAN’s establishment—as well as Muhammadiyah members who form PAN’s mass base (Buehler, 2009; Mayrudin and Akbar, 2019). PAN has consistently presented itself as an open party that promotes the ideologies of pluralism, nationalism, and religion.

The cadre formation system in PAN resembles that of other parties and is implemented in stages. According to PAN’s regulations, cadre formation is conducted formally, informally, and specifically. The DPP prepares a syllabus for training materials that emphasizes the spirit of nationalism. This includes topics such as party history, ideology, platform, and the direction of political struggle; the reformist spirit that gave birth to PAN; political and governance skills; policy formulation processes; election-winning strategies; and strategies for navigating contemporary political dynamics (ASW, 2023). From its inception, PAN has carried the identity of an open party committed to pluralism, nationalism, and religion, aligning closely with the spirit of Pancasila. Despite its close affiliation with Muhammadiyah, PAN does not have a dedicated section for religious content; rather, religious principles are embedded directly within various cadre formation materials (VYG, 2023).

As the largest Pancasila-oriented Islamic party, PKB conceives of Pancasila as a philosophy rooted in nationalist and moderate principles, while grounding its struggle in Islamic values—particularly ahlusunnah wal jamaah (those who adhere to the Prophet’s teachings and remain with the united Muslim community) teachings (Dhakhiri and Djafar, 2015; PKB, 2019). Since its establishment, PKB has advocated an inclusive view of the Indonesian state and a moderate form of traditionalist Islam.

Although founded on elements of Nahdlatul Ulama (Islamic Scholars Awakening/NU), PKB’s political philosophy is not limited to serving the interests of NU or Islam alone but extends to the broader interests of the nation (Tim Kajian Lanskap Indonesia, no date). PKB promotes a pluralistic philosophy, presenting itself as an open party devoted to the national ideology of Pancasila while recognizing the realities of Indonesia’s multicultural society (Hamayotsu, 2011). In this sense, PKB demonstrates inclusivity, as it draws on Islamic principles while maintaining a broader agenda (Baswedan, 2004).

PKB conducts cadre education through the Academy for National Politics, which operates exclusively at the central level. This academy provides political training for prospective leaders, candidates for public office, members of the legislature at various levels, and executive officials (ASL, 2023; PKB, 2019). The pluralist and inclusive character of PKB influences its cadre training materials, which incorporate both religious and national values. Party ideology and national values form the core of PKB’s cadre education (ASL, 2023). This integration exemplifies the party’s character as a religiously based organization that regards national and religious values as inseparable and mutually reinforcing.

In PPP, Islam is explicitly stated as the party’s foundation. However, the party does not position itself as a political vehicle for the establishment of an Islamic state. Instead, it acknowledges Indonesia’s pluralistic reality and promotes moderation in interpreting Islam (PPP, 2020). This spirit resonates with the essence of Pancasila as an open ideology that fosters moderation. PPP requires all members to participate in cadre training programs. Five main subjects are typically taught: Islamic teachings, the principles of PPP’s struggle, party organization and leadership, election-winning strategies, and cadre self-image (PPP, 2020). Through this process, the party aims to produce cadres with a strong connection to the people, moderate characteristics, and the skills necessary to collaborate with international networks (PPP, 2020).

PKS is popularly known as a cadre party, maintaining the belief that Islam has relevance in the political realm and should guide Muslims in political engagement. Its cadre formation includes five core components: (1) religion—emphasizing personal piety, anti-corruption attitudes, honesty, and striving for divine approval; (2) nationalism—strengthening national identity and affirming unifying values such as the Republic of Indonesia and Pancasila; (3) community—promoting human values, peaceful coexistence, and celebrating diversity under the motto ‘Unity in Diversity’; (4) party system—encouraging loyalty to the party and commitment to democracy with honesty, maturity, and civility; and (5) leadership and entrepreneurship—developing skills to contribute to the welfare of the Indonesian people (Aripin, 2020).

The Party Cadre Education Curriculum (KKP) further specifies achievement indicators for each cadre level. At the junior level, cadres are introduced to democracy, the history of the 1945 Constitution, and Pancasila as the state foundation (PKS, n.d.). At the primary level, the focus shifts to the role of members in defending the country (PKS, n.d.). At the intermediate level, cadres study basic theories of geopolitics and national disintegration. At the adult level, they explore the relevance of Pancasila in the context of globalization and its application in advancing justice, democracy, and welfare (PKS, n.d.). These materials demonstrate PKS’s strong commitment to integrating nationalism into its political doctrine, marking a progressive shift for an Islamic party, as it requires cadres to engage deeply with national issues.

In summary, the cases of PAN, PKB, PPP, and PKS demonstrate that Pancasila-oriented Islamic parties do not position themselves in opposition to nationalist principles but rather integrate them into their organizational identity and cadre formation. While these parties maintain distinct Islamic orientations—whether through Muhammadiyah in PAN, NU in PKB, or more programmatic approaches in PPP and PKS—they simultaneously affirm Pancasila as the foundation of national unity and political legitimacy. This dual orientation reflects a broader trend of convergence between religious and nationalist values in Indonesian party politics, where Pancasila functions as a unifying ideological framework that both nationalist and Islamic parties use to negotiate their identities, appeal to a plural society, and legitimize their political roles.

3.2.2 Putting forward Islamic substance: respecting pluralism as part of Pancasila

Beyond the cadre training materials that incorporate nationalist values, the political behavior of Pancasila-oriented Islamic parties also reflects a similar convergence of values, further reinforcing the argument that contemporary Indonesian political parties are oriented toward Pancasila.

Since its establishment, PAN has upheld Islam as the moral and ethical foundation of its struggle while still grounding the party itself in Pancasila. Several of PAN’s founders, including A. M. Fatwa, emphasized that Islam as a moral force should not be separated from the party while simultaneously ensuring that PAN remains an open party that values religiosity (Soeparno, 2024). The party’s struggle focuses on advancing national life based on Pancasila and the interests of all citizens, a vision initiated by pro-democracy activists and intellectuals from diverse backgrounds, including Faisal Basri, Toety Herati, Arif Aryyman, Goenawan Muhammad, and Bara Hasibuan.

Although PAN once had an Islamic faction—historically even its largest faction—this did not turn the party into one that pursued Islamic sharia or an Islamic state. PAN has consistently remained an open party with a platform that respects pluralism (Soeparno, 2024). In current times, the dominant faction within PAN is in fact the pragmatic group (Sugiarto, 2006), composed mainly of business figures who emphasize pluralism and a strong commitment to PAN’s identity as an inclusive party. This group successfully counters the Islamist faction and draws inspiration from PAN’s original pluralist platform (Soeparno, 2024). Their reasoning is pragmatic: relying solely on Muhammadiyah has proven electorally limiting, with PAN consistently earning only approximately 7% of the vote.

This orientation toward openness has become more visible over the past decade, as PAN increasingly attracts members from diverse backgrounds, becoming less Islamist and less dependent on Muhammadiyah. Celebrities have also become active within the party, culminating in the appointment of comedian Eko Patrio as Secretary-General, representing the pluralist faction. Electorally, PAN’s strategies have shifted away from Islamist alignments, instead cooperating with nationalist parties. For instance, PAN supported President Joko Widodo’s administration and later joined the Koalisi Indonesia Maju with Gerindra, Demokrat, and Golkar to back Prabowo-Gibran (Ekawati, 2019). While some observers view these alliances as opportunistic, PAN frames them as consistent with its pluralist platform, namely a party open to cooperation with all groups, not only Muhammadiyah or Islamic circles.

Similarly, since its founding in 1998, PKB has emphasized Pancasila as the ultimate basis of the state and a national consensus. This stems from its historical roots in Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), which, at the 1984 Situbondo Congress, accepted Pancasila as the sole foundation, declaring it compatible with Islam. This principle became PKB’s ideological foundation: Pancasila is the party’s basis, while Ahlussunnah wal Jama’ah serves as the source of moral and ethical inspiration (PKB, 2019). PKB sees Pancasila as the unifying umbrella of the nation, orienting its political agenda toward preserving unity in diversity. Its vision and mission documents emphasize implementing Pancasila through public policy, particularly in building a just democracy, promoting social justice, and respecting human rights.

PKB has also taken inclusive steps in leadership structures and legislative candidacy in areas where non-Muslims are the majority. In Samosir (North Sumatra), for example, PKB won legislative seats entirely with non-Muslim candidates (Detik.com, 2024). In Papua, PKB explicitly prioritizes the representation of indigenous Papuans, who are predominantly Christian (Kejoranews.com, 2021). In Bali, its wing organization DPP Berani (Badan Persaudaraan Antar Iman) highlights interfaith engagement (Detiknews.com, 2024). These practices demonstrate PKB’s commitment not only to traditional Islam but also to recognizing and embracing religious diversity as part of national politics.

For PPP, Pancasila is firmly established as the state foundation and final consensus, while Islam remains the primary source of moral and spiritual motivation (PPP.or.id, 2021). In its Khitthah and official platform, PPP commits to safeguarding NKRI under Pancasila and the 1945 Constitution while integrating Islamic values into its political identity. Historically, PPP restricted non-Muslims from candidacy or leadership under its statutes. However, a significant shift occurred in 2013, when party chairman Suryadharma Ali announced openness to nominating non-Muslim candidates (Kompas.com, 2013). Since then, PPP branches have included non-Muslims in leadership and candidacy, such as in NTT, Maluku Utara, and Maluku (Aman.or.id, 2019; Detiknews.com, 2011; Timesindonesia.co.id, 2024). This reflects PPP’s gradual pluralist adaptation while retaining its Islamic moral base.

Finally, PKS emphasizes safeguarding NKRI as a legacy of the nation’s founders, affirming that Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity) is not subject to debate (Syaikhu, 2021). This stance rejects perceptions of PKS as fixated on establishing an Islamic caliphate and affirms its commitment to the nation-state and pluralism (Noor, 2025). PKS emphasizes the substance of Islam—its ethical and moral values—over formalistic aspirations. Party president Syaikhu (Syaikhu, 2021) declared that Islam, Pancasila, and NKRI are inseparable. For PKS, the principle of Ketuhanan Yang Maha Esa (Belief in One God), as outlined in Pancasila, corresponds to tauhid, the core of Islamic faith (MPP PKS, 2021).

In recent years, PKS has repositioned itself as a “Partai Rahmatan lil Alamin” (a mercy-for-all party), distancing itself from the label of “Partai Dakwah.” This rebranding emphasizes inclusivity, collaboration, and service to all citizens, not only Muslims (Noor, 2025; Sulistiyono, 2000). PKS has actively built ties with Nahdliyin, nationalists, former military officers, and even CSIS (a think tank often linked to Catholic-nationalist circles) (Noor, 2025; Syaikhu, 2022). At the regional level, its branches in Christian-majority provinces such as NTT and Papua include Christian and Catholic leaders, including a son of a pastor serving as a local chair (PKSTV, 2023).

At the national level, PKS has appointed several non-Muslims to its Dewan Pakar (Advisory Council), recruiting them for their professional expertise (Noor, 2025). The current DPP office even displays a large Garuda Pancasila statue, symbolizing the party’s respect for Pancasila as the foundation of Indonesian nationhood (Noor, 2025).

The trajectories of PAN, PKB, PPP, and PKS illustrate that Islamic parties in Indonesia, while retaining Islamic moral and ethical references, have increasingly articulated their political struggle within the framework of Pancasila. This development highlights Pancasila’s dual role as both an integrative national ideology and a strategic resource for political legitimacy. By emphasizing pluralism and inclusivity, these parties not only reaffirm their commitment to the state ideology but also ensure their relevance in a heterogeneous society where political support cannot be secured solely through religious or other primordial identities. In this sense, the convergence observed in Pancasila-oriented Islamic parties mirrors that of nationalist parties, revealing a shared logic of adaptation: the necessity of positioning within the Pancasila consensus to avoid marginalization and to broaden electoral appeal. Consequently, Pancasila emerges not merely as a constitutional settlement but as a hegemonic framework shaping the ideological orientation and political practice of both nationalist and Islamic parties in contemporary Indonesia.

4 Mapping Indonesian political parties in the reform era

Generally, political parties in Indonesia are founded on or oriented toward the principles of Pancasila. Within the global discourse on political party ideology, the values of Pancasila encompass not only nationalism but also religion (the first pillar). Consequently, Pancasila-oriented parties are typically positioned at the center of the ideological spectrum. On the left are secular parties, while on the right are religious or Islamic parties. These positions closely resemble Feith and Castle’s typology, which placed the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) as an example of a secular party and Masyumi, which had the primary purpose of establishing Indonesia based on Islamic norms, as an Islamist one.

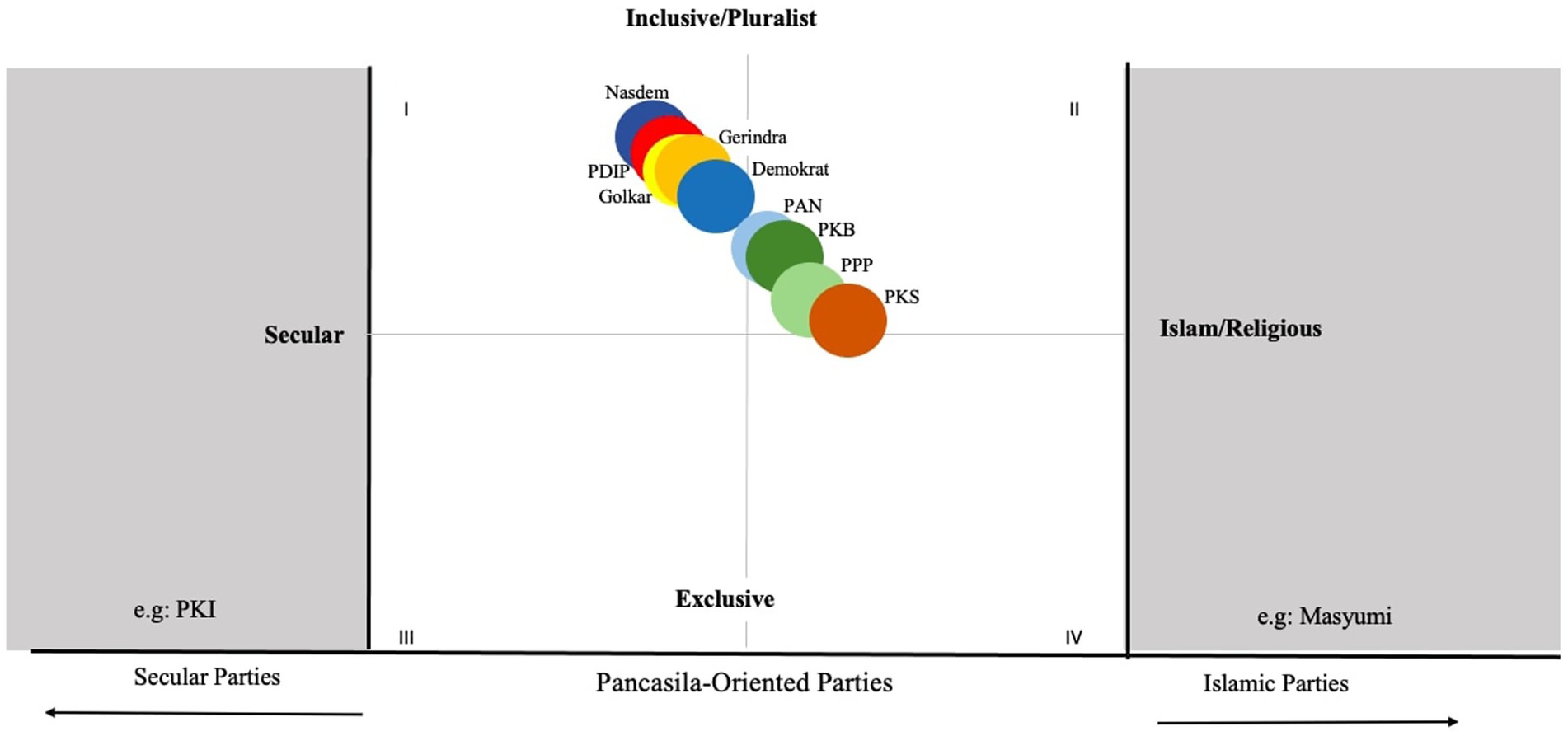

However, based on a study of value infusion and political behavior, gradations between parties are still visible. From the figure below, four quadrants can be identified. The horizontal axis reflects ideological orientation, ranging from secular on the left to Islamic/religious on the right, with parties oriented toward Pancasila occupying the center. The vertical axis, meanwhile, represents the degree of inclusiveness: parties at the top emphasize pluralism and openness, whereas those at the bottom lean toward exclusivity (Figure 1).

This mapping illustrates how most Indonesian political parties cluster around the Pancasila center, yet differ in their degree of inclusiveness and religious commitment. NasDem is located in Quadrant I, showing a strong orientation towards high inclusiveness in both value infusion and political behavior. PDI-P occupies the same quadrant but shifts slightly to the right, as it incorporates more religious value adjustments into its political behavior compared to NasDem. Meanwhile, Golkar and Gerindra display similar levels of inclusiveness, though Gerindra leans more toward Islamic orientations. Consequently, Gerindra is positioned further to the right than Golkar. Demokrat Party lies in Quadrant I and has a greater emphasis on religious values compared to the four previous parties.

Among the Pancasila–Islamic-oriented parties, PAN and PKB fall in Quadrant II, sharing almost the same degree of pluralism, with PKB placing greater emphasis on religious values than PAN. PPP also lies in Quadrant II but is positioned closer to the religious side, as reflected in both its cadre formation materials and its political behavior. PKS, though still within Quadrant II, is situated nearer to the religious continuum than PPP, given its stronger emphasis on Islamic identity in both values and behavior. Therefore, it can be inferred that the parties categorized as Pancasila-oriented nationalist parties—ranging from those that place a stronger emphasis on nationalist values to those that incorporate more Islamic elements—are the following: NasDem, PDIP, Golkar, Gerindra, and Demokrat. On the other hand, the Pancasila-oriented Islamic parties, which range from those that stress Islamic values more strongly to those leaning toward nationalist values, are PKS, PPP, PKB, and PAN. This mapping illustrates that contemporary Indonesian political parties tend to cluster in the centrist zone while still reflecting gradations between nationalist and religious orientations.

5 Conclusion

The development of ideology and its implementation by political parties in the reform era has led scholars to re-examine the characteristics of Indonesian political parties. Moving beyond the earlier dichotomous classification of party ideologies, this study demonstrates a convergence of Islamic and nationalist values in Indonesian politics. This convergence is particularly evident in two dimensions: value infusion, as reflected in the substance of cadre formation materials, and political behavior, as expressed in practice.

Currently, no political party places exclusive emphasis on either the nationalist or the religious dimension. Instead, both values are blended within the Pancasila-oriented framework, which positions itself at the center of the global ideological spectrum. However, this centrist orientation does not mean that all parties occupy the same position. Variations persist, particularly in terms of their degree of inclusiveness and pluralism. Among the Pancasila-oriented parties, NasDem exemplifies a party with strong nationalist values and a high commitment to pluralism, while PKS occupies a more exclusive, religion-oriented position on the center-right. Overall, Indonesian party politics is increasingly centrist, though differentiated by distinct gradations of nationalist and religious weight.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Dr. Agustina Situmorang, MA, of the Ethical Committee on Social Studies and Humanities at NRIA (IPSH BRIN). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The study was granted Ethics Clearance under Decision Number: 082/KE.01/SK/04/2023. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

FF: Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology, Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft. MS: Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis, Methodology. FN: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Resources, Data curation. LR: Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. RH: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. SS: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Research Organisation of Social Sciences and Humanities, National Research and Innovation Agency of the Republic of Indonesia (BRIN). While this publication was funded by Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abduljaber, M. (2018). The dimensionality, type, and structure of political ideology on the political party level in the Arab world. China Political Sci. Rev. 3, 464–494. doi: 10.1007/s41111-018-0101-7

Akademi Bela Negara Nasdem. (n.d.). Tentang Akademi Bela Negara Nasdem. Available online at: https://abn-nasdem.com/About/Index.

Aman.or.id. (2019). Caleg AMAN: Pendeta Kristen, Tapi Caleg Partai Berlambang Ka’bah. Available online at: https://aman.or.id/news/read/69

Aripin, Z. (2020). Kurikulum Kepemimpinan Kaderisasi PKS, Pancasila dan UUD NRI 1945. Available online at: https://radarbekasi.id/2020/09/15/kurikulum-kepemimpinan-kaderisasi-pks-pancasila-dan-uud-nkri-1945/.

Aspinall, E., Fossati, D., Muhtadi, B., and Warburton, E. (2018). Mapping the Indonesian political spectrum. In new mandala. Available online at: https://www.newmandala.org/mapping-indonesian-political-spectrum/

Aspinall, E., Fossati, D., Muhtadi, B., and Warburton, E. (2020). Elites, masses, and democratic decline in Indonesia. Democratization 27, 505–526. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1680971

Aspinall, E., and Mietzner, M. (2019). Indonesia’s democratic paradox: competitive elections amidst rising illiberalism. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 55, 295–317. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2019.1690412

Aspinall, E., Mietzner, M., and Tomsa, D. (2015). The Yudhoyono presidency: Indonesia’s decade of stability and stagnation. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

Baswedan, A. (2004). Political Islam in Indonesia: present and future trajectory. Asian Surv. 44, 669–690. doi: 10.1525/as.2004.44.5.669

Bourchier, D. M. (2019). Two decades of ideological contestation in Indonesia: from democratic cosmopolitanism to religious nationalism. J. Contemp. Asia 1–21, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2019.1590620

Budge, I., and Laver, M. (1986). Policy, ideology, and party distance: analysis of election Programmes in 19 democracies. Legis. Stud. Q. 11:607. doi: 10.2307/439936

Buehler, M. (2009). Islam and democracy in Indonesia. Insight Turkey 11, 51–63. doi: 10.1080/14683840500119494

Buehler, M. (2013). Subnational Islamization through secular parties: comparing I shari’a/I politics in two Indonesian provinces. Comp. Polit. 46, 63–82. doi: 10.5129/001041513807709347

Demokrat.or.id. (2025). Hadiri Simaan Al-Qur’an dan Dizkrul di Ponorogo, Ibas: Sampaikan Doa untuk Masyarakat dan Bangsa. Available online at: https://www.demokrat.or.id/hadiri-simaan-al-quran-dan-dizkrul-di-ponorogo-ibas-sampaikan-doa-untuk-masyarakat-dan-bangsa/

Deni, R. (2022). Majelis Dakwah Islamiyah Dinilai Bakal Jadi Garda Terdepan Sudahi Politik Identitas. Available online at: https://www.tribunnews.com/nasional/2022/06/06/majelis-dakwah-islamiyah-dinilai-bakal-jadi-garda-terdepan-sudahi-politik-identitas

Detik.com. (2024). Daftar 25 Anggota DPRD Samosir Terpilih: PKB Geser PDIP dari Kursi Ketua. Available online at: https://www.detik.com/sumut/berita/d-7259700/daftar-25-anggota-dprd-samosir-terpilih-pkb-geser-pdip-dari-kursi-ketua

Detiknews.com. (2011). Muqowam: Non Muslim Tak Bisa Jadi Caleg PPP. Available online at: https://news.detik.com/berita/d-1661680/muqowam-non-muslim-tak-bisa-jadi-caleg-ppp

Detiknews.com. (2024). Organisasi Sayap PKB Tegaskan Muktamar yang Sah Hanya di Bali. Available online at: https://news.detik.com/berita/d-7497440/organisasi-sayap-pkb-tegaskan-muktamar-yang-sah-hanya-di-bali

Dhakhiri, H., and Djafar, T. B. M. (2015). Struktur Politik Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa the Political Structure of Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa. Jurnal Kajian Politik Dan Masalah Pembangunan 11, 1601–1612.

Dhakidae, D. (1999). “Partai-partai politik Indonesia: Kisah pergerakan dan organisasi dalam patahan-patahan sejarah” in Partai-Partai Politik Indonesia, Ideolog, Startegi dan Program. ed. T. L. Kompas (Jakarta: Gramedia).

DPD Partai Golkar Provinsi Riau (2025) DPD Majelis Dakwah Islamiyah Provinsi Riau. Available online at: https://golkarriau.com/web/site/ormas-sayap/majelis-dakwah-islamiah-mdi.html

Ekawati, E. (2019). Peta Koalisi Partai-Partai Politik di Indonesia pada Pemilihan Presiden dan Wakil Presiden Pasca Orde Baru. JPPUMA: Jurnal Ilmu Pemerintahan Dan Sosial Politik UMA (Journal of Governance and Political Social UMA) 7, 160–172. doi: 10.31289/jppuma.v7i2.2680

Evans, G., Heath, A., and Lalljjee, M. (1996). Measuring left-right and libertarian-authoritarian values in British electorate. Br. J. Sociol. 47, 93–112. doi: 10.2307/591118

Evans, K. (2003). The history of political parties and general elections in Indonesia. Arise Consultanies. pp. 1–162.

Feith, H., and Castles, L. (1970). Indonesian political thinking, 1945–1965 : Cornell University Press.

Fionna, U. (2016). Indonesian parties in a deep dilemma: The case of Golkar. Singapore: Perspective.

Fitriyah, F. (2020). Partai Politik, Rekrutmen Politik dan Pembentukan Dinasti Politik pada Pemilihan Kepala Daerah (Pilkada). Politika: Jurnal Ilmu Politik, 11, 1–17. doi: 10.14710/politika.11.1.2020.1-17

Fraksigerindra.id. (2024). Gelar Rapimnas ke-I, GEMIRA Siap Memperjuangkan Aspirasi Umat Islam. Available online at: https://www.fraksigerindra.id/gelar-rapimnas-ke-i-gemira-siap-memperjuangkan-aspirasi-umat-islam/

Hamayotsu, K. (2011). The end of political Islam? A comparative analysis of religious parties in the Muslim democracy of Indonesia. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Affairs 30, 133–159. doi: 10.1177/186810341103000305

Honna, J. (2012). Inside the democrat party: power, politics and conflict in Indonesia’s presidential party. South East Asia Res. 20, 473–489. doi: 10.5367/sear.2012.0125

Hukumonline.com. (2021). 4 Fakta Transformasi Hukum Islam dalam Hukum Nasional. Available online at: https://www.hukumonline.com/berita/a/4-fakta-transformasi-hukum-islam-dalam-hukum-nasional-lt60c877974a475/

Jackle, S., and Timmis, J. K. (2023). Left–right-position, party affiliation and regional differences explain low COVID-19 vaccination rates in Germany. Microb. Biotechnol. 16, 662–677. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.14210

Jemali, V. (2021). AHY, Ulama, dan “Yang Ini Pun Akan Berlalu”. Available online at: https://www.Kompas.Id/Artikel/Ahy-Ulama-Dan-Yang-Ini-Pun-Akan-Berlalu

Kejoranews.com. (2021). Pengurus DPC PKB se Papua Diharapkan dari Orang Asli Papua dan Adanya Keterwakilan Perempuan. Available online at: https://www.kejoranews.com/2021/03/pengurus-dpc-pkb-se-papua

Khalida, M. S. (2024). Ketum GEMIRA ingatkan politik dan agama harus selalu bersandingan. Available online at: https://www.Antaranews.Com/Berita/4349283/Ketum-Gemira-Ingatkan-Politik-Dan-Agama-Harus-Selalu-Bersandingan

Kompas.com. (2013). PPP Membuka Diri untuk Caleg Non-Muslim. Available online at: https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2013/01/07/02331965/ppp-membuka-diri-untuk-caleg-non-muslim

Künkler, M., and Lerner, H. (2016). A private matter? Religious education and democracy in Indonesia and Israel. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 38, 279–307. doi: 10.1080/01416200.2015.1113933

Lanti, I. G. (2004). The elusive quest for statehood: Fundamental issues of the state, political cultures and aliran politics in Indonesia [PhD Thesis] : University of British Columbia.

Mayrudin, Y. M., and Akbar, M. C. (2019). Pergulatan Politik Identitas Partai-partai Politik Islam: Studi tentang PAN, PKB dan PKS. Madani: Jurnal Politik Dan Kemasyarakatan 11, 169–186.

Mentari, D. S. (2018). Harga Sebuah Pilihan: Strategi PKS dan Partai Demokrat Menata Raut Wajah (Cetakan I). Yogyakarta: Penerbit PolGov.

Minar, D. (1961). Ideology and political behavior. Midwest J. Political Sci. 5, 317–331. doi: 10.2307/2108991

MPP PKS. (2021). Falsafah Dasar Perjuangan Partai Keadilan Sejahtera. Majelis Pertimbangan Pusat, Partai Keadilan Sejahtera.

Nasdemdprri.id. (2018). Surya Paloh: Nasdem Menganut Prinsip Nasionalis – Religius. Available online at: https://nasdemdprri.id/berita/surya-paloh-nasdem-menganut-prinsip-nasionalis-religius

Nasdem, P. (2018). Kewajiban Dasar Kader NasDem Menjaga Pluralisme. Available online at: https://nasdem.id/2018/11/22/kewajiban-dasar-kader-nasdem-menjaga-pluralisme/

Noor, F. (2015). Perpecahan dan Soliditas Partai Islam di Indonesia: Kasus PKB dan PKS di dekade awal reformasi. Jakarta: LIPI Press.

Noor, F. (2025). Transformasi Partai Keadilan Sejahtera: Menuju Penguatan Politik Islam Substansialis dan Pemantapan Orientasi Kebangsaan. Jakarta: Penerbit Buku Kompas.

Nurjaman, A. (2023). The decline of Islamic parties and the dynamics of party system in post-Suharto Indonesia. Jurnal Ilmu Sos. Dan Ilmu Polit. 27:192. doi: 10.22146/jsp.79698

Partai Demokrat (2020). Anggaran Dasar dan Anggaran Rumah Tangga Partai Demokrat : Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Demokrat.

Partai Gerindra. (2020). Anggaran Dasar dan Anggaran Rumah Tangga Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya. Available online at: https://partainasdem.id/2018/04/06/nasdem-al-khairaat-sepakat-bumikan-islam-rahmatan-lil-alamin/

Partainasdem.id (2018). NasDem-Al Khairaat Sepakat Bumikan Islam Rahmatan Lil Alamin. Available online at: https://partainasdem.id/2018/04/06/nasdem-al-khairaat-sepakat-bumikan-islam-rahmatan-lil-alamin/

PDIP. (2019). Anggaran Dasar dan Anggaran Rumah Tangga Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan 2019–2024.

Pdiperjuangan-jatim.com. (2017). Hamka Haq Tegaskan PDIP Adalah Partai Nasionalis-Religius. Available online at: https://pdiperjuangan-jatim.com/hamka-haq-tegaskan-pdip-adalah-partai-nasionalis-religius/

PKSTV. (2023). Gabung PKS Tidak Harus Pindah Agama [Broadcast]. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLuoDTOjhnM

PPP.or.id. (2021). Lima Khidmat dan Enam Prinsip Perjuangan PPP. Available online at: https://ppp.or.id/2021/12/06/lima-khidmat-dan-enam-prinsip-perjuangan-ppp/

Randall, V., and Svåsand, L. (2002). Party institutionalization in new democracies. Party Politics, 8, 5–26. doi: 10.1177/1354068802008001001

Soeparno, M. E. (2024). Transformasi Perubahan Partai di Indonesia: Studi Kasus Partai Amanat Nasional Periode 2016–2022 [PhD Thesis]. Depok: University of Indonesia.

Sugiarto, B. A. (2006). Beyond formal politics: Party factionalism and leadership in post-authoritarian Indonesia. Canberra: RSPAS-Australian National University.

Sulistiyono, S. T. (2000). Ketua Majelis Syura Habib Salim Segaf Al-Jufri Sebut PKS Partai Islam Ramatan lil Alamin. Available online at: https://www.tribunnews.com/nasional/2020/11/29/ketua-majelis-syura-habib-salim-segaf-al-jufri-sebut-pks-partai-islam-rahmatan-lil-alamin

Suryaningtyas, M. T. (2025). Memaknai Posisi Politik Partai Gerindra di Usia 17 Tahun. Available online at: https://Www.Kompas.Id/Artikel/Memaknai-Posisi-Politik-Partai-Gerindra-Di-Usia-17-Tahun

Syaikhu, A. (2022). Catatan Harian Ahmad Syaikhu Edisi 12 (Desember 2021-Februari 2022) DPP Partai Keadilan Sejahtera

Tempo.co. (2003). PDIP Bantah Tolak Pemberlakuan Syariat Islam. Available online at: https://www.tempo.co/arsip/pdip-bantah-tolak-pemberlakuan-syariat-islam-2021662

Timesindonesia.co.id. (2024). DPC PPP Pulau Taliabu Berhasil Menghantarkan Caleg Non Muslim ke Kursi DPRD Kabupaten. Available online at: https://timesindonesia.co.id/politik/488845/dpc-ppp-pulau-taliabu-berhasil-menghantarkan-caleg-non-muslim-ke-kursi-dprd-kabupaten

Tomsa, D. (2010). Indonesian politics in 2010: the perils of stagnation. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 46, 309–328. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2010.522501

Ufen, A. (2006). Political parties in post-Suharto Indonesia: Between politik aliran and ‘Philippinisatio. Hamburg: GIGA Working Papers.

Ufen, A. (2008). Political party and party system institutionalization in Southeast Asia: lessons for democratic consolidation in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand. The Pasific Review 21, 327–350. doi: 10.1080/09512740802134174

YouTube Channel ABN Nasdem. (2018). 1 Tahun Akademi Bela Negara. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aFtL_XLkqbg

Keywords: Pancasila-oriented parties, nationalist parties, Islamic parties, party ideology, party spectrum, party typology

Citation: Fitriyah F, Sweinstani MKD, Noor F, Romli L, Hanafi RI and Siregar SN (2025) The convergence of contemporary Indonesian political parties. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1640022. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1640022

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Andi Luhur Prianto, Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, IndonesiaMochamad Iqbal Jatmiko, University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Rofhani Rofhani, Uin Sunan Ampel Surabaya, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Fitriyah, Sweinstani, Noor, Romli, Hanafi and Siregar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fitriyah Fitriyah, Zml0cml5YWh1bmRpcEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Fitriyah Fitriyah

Fitriyah Fitriyah Mouliza K. D. Sweinstani

Mouliza K. D. Sweinstani Firman Noor

Firman Noor Lili Romli2

Lili Romli2 Sarah Nuraini Siregar

Sarah Nuraini Siregar