- 1Center for Analytical Research and Evaluation, Supreme Audit Chamber, Astana, Kazakhstan

- 2Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, United States

The research is aimed at in-depth study of the perception of conflict of interest among public servants of Kazakhstan and finding out how they tend to view this phenomenon as a manifestation of corruption. The objective is to understand how the level of awareness, and education affects the perception of conflicts of interest, and to propose approaches that will help improve regulatory measures. The study employs a mixed methodology, including quantitative, and qualitative data analysis. The research was based on a sociological survey of 10,255 public servants of Kazakhstan, the data of which were analyzed using regression models. According to the study, 82.8% of respondents indicated that difficulties in ensuring compliance with ethical standards contribute to conflicts of interest. At the same time, most respondents associate such conflicts with potential corruption threats. Moreover, regression analysis shows that perceptions of conflict-of-interest policies depend on respondents' understanding and education level. More education leads to critical views on measures, while insufficient understanding impairs perception. The study contributes to the discussion of conflict of interest regulation in the public sector, emphasizing the importance of the educational level and awareness of public servants for effective regulation. The findings are useful for developing more effective anti-corruption and regulatory strategies. Practical implications of the research include updating regulatory policies to address conflict of interest perceptions, enhancing public service ethics through targeted training, and strengthening management and monitoring mechanisms. These measures will improve transparency and thereby increase public trust in government institutions.

Introduction

The global economy loses over $2.6 trillion annually to corruption, which is equivalent to 5% of global GDP, according to a widely accepted estimate (Fleming, 2019). Considering the global GDP for 2022 is estimated at US$ 101 trillion, this would correspond to a global theft of $5 trillion annually (Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre, 2024). Corruption in the EU, for instance, results in losses that exceed the officially reported figures, totaling 323 billion euros annually (News.az, 2021).

In this context it's worth mentioning that conflicts of interest remain one of the most prevalent manifestations of corruption worldwide. Thus, a significant part of society holds the belief that a conflict of interest carries a substantial likelihood of resulting in corruption.

As evidenced by the norms and regulations of international organizations, while a conflict of interest may not be considered corruption in itself, it does contribute to its emergence. This is a scenario in which personal interests, whether they be related to family, business, or other matters, enable an individual to act in a way that goes against their official responsibilities or the best interests of the public.

Transparent International defines a conflict of interest as a situation where an individual or the organization they serve must choose between their job duties and personal interests (Transparency International, 2009).

The OECD divides conflicts into apparent and potential. An apparent conflict of interest arises when a public official's personal interests seem to unduly impact their duties, whereas they do not. A potential conflict arises when an official possesses private interests that collide with their future official duties (OECD, 2005).

The UN also recognizes conflict of interest as an urgent issue in Article 7, Paragraph 4 of the Convention against Corruption, by confirming the obligation of each State Party to take all appropriate measures to promote transparency and prevent conflicts of interest (United Nations, 2003).

Any conflict of interest or the very realization of it in any case raises doubts on the part of society about the integrity of public servants.

According to researchers there are mainly two strategies for effectively managing conflicts of interest (Demmke et al., 2020; Huberts and Van Montfort, 2020; Heywood and Rose, 2015; Treviño et al., 1999). One of the approaches is a regulatory method known as compliance-based, which relies on established rules and regulatory norms. The second approach is an integrity-based strategy, which is founded on the principles of values and common sense (integrity-based) (Demmke et al., 2020).

Huberts and Van Montfort (2020) suggest that the optimal and preferable outcomes can only be achieved by integrating these two approaches.

The OECD document outlines a set of measures that include both formal instruments—such as rules, procedures, and declarations—and organizational efforts aimed at promoting integrity and a culture of trust (OECD, 2024a).

In Kazakhstan, conflicts of interest are formally acknowledged as a pressing issue at the governmental level.

Thus, the Anti-Corruption Policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2022–2026, approved by Presidential Decree No. 802, includes the prevention and regulation of conflicts of interest as important aspects of the anti-corruption strategy (Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2022).

Based on Kazakhstan's practical experience, it is evident that the issue of conflict of interest in the public service has not been thoroughly examined. Merely providing analytical resources is insufficient in addressing the need for effective methods to prevent and regulate conflicts of interest in the public service. Thus, the issue of addressing conflicts of interest is of utmost importance.

In this context, the primary research questions of this study are as follows:

1. What is the perception of public servants on the subject of conflict of interest in the public service?

2. What are the factors that shape the public servants' perceptions regarding the conflict-of-interest regulation policy?

3. What is the most effective approach for addressing conflict of interest in light of the findings?

This article examines the limited number of conflict-of-interest studies in public administration and the lack of theoretical research in this area. It focuses on the analysis of a sociological survey to identify what does a conflict of interest mean to public servants and what are the factors that contribute to understand how the degree of regulation is perceived.

To address the research questions, quantitative and qualitative research methodologies are implemented, utilizing primary data from the survey analysis among the 10,255 public servants. This research is of significant importance and relevance, as it is expected to provide policymakers and other stakeholders with valuable insights into the effective conflict of interest regulation in the public service.

Literature review

While some researchers (Bergstrom, 1970; Davids, 1998; Carson, 1994; Davis and Stark, 2001; Di Carlo, 2013; Schindler, 2013; Kennedy, 2013) consider inter alia the significance of the conflict-of-interest concept, others focus on its essence and view it as a matter of ethics (Walter, 1981; Werhane and Doering, 1995; McMunigal, 1998; Argandoña, 2004; Boyce and Davids, 2009; Doig, 2014; Di Carlo, 2013; Mital, 2019; Suk Kim and Yun, 2017). Yet another group of researchers suggest that a conflict-of-interest issues could be examined in conjunction with corruption (Gong and Ren, 2013; Chapman, 2014; Doig, 2014; Cerrillo-i-Martinez, 2017; Hue, 2020; Demmke et al., 2023; Strelcenoks, 2023).

In addition to this, the conflict of interest in public administration is often examined through two main ethical frameworks: the compliance-based and values-based approaches (Anderson, 1997; Kaptein, 1998; Weaver and Treviño, 1999; Maesschalck, 2004; Roberts, 2009; Huberts, 2014). The first one focuses on rules, penalties, and ways to make sure they are followed. The second one, on the other hand, is more about organizational culture, moral motivation, and encouraging people to act in an ethical way. While both theories try to reduce ethical risks, some critics say that compliance-based systems might lead to a culture of minimalism and checking off the right boxes. In its turn values-based models need strong moral leadership and well-developed institutions, which might not be present in transitional states. Because of this, a balanced hybrid method is often the best choice.

Bergstrom (1970) asserts that a precise definition of conflict of interest is unattainable due to the fact that this notion varies in meaning across different contexts and circumstances.

Davids (1998) acknowledges that the OECD provides the most precise description of the term of conflict of interest. This document presents several crucial mechanisms for identifying potential and specific conflicts of interest, including: a statement of interest, disclosure of assets and other financial interests, a declaration validated by an oath, and statements submitted to supervisory or relevant authorities regarding specific conflicts.

Notably, Carson (1994) highlights that conflict arises solely when personal interests contradict official responsibilities.

Di Carlo's analysis (2013) revealed that public servants either lack a precise understanding of the conflict of interest or hold entirely divergent opinions. Consequently, this concept is interpreted differently by each individual. Therefore, the author underscores the significance of recognizing the conflict of interest and providing examples assisting in its resolution, as well as paying particular attention to the concept of conflict of interest in the codes of behavior and ethics.

The conflict of interest is contingent upon the specific nature of the work or activity. Conflicts of interest in the profession can come from the multitude of roles involved, but the underlying objective of the activity remains the same. Alternatively, conflicts may arise from the presence of many purposes in the work, irrespective of the number of roles. While certain conflicts pertain to the internal dynamics of the profession, others arise from external factors such as family or commercial connections (Davis and Stark, 2001).

The most critical responsibility is to promptly identify a conflict of interest and differentiate it contingent upon the specifics of a given situation. A conflict of interest is a difficult endeavor to identify. The introduction of legal measures to combat a conflict of interest is contingent upon the recognition of the conflict. As a result, a clear definition of a conflict of interest and the items that do not fall under its scope improves its comprehension. Although there have been numerous studies conducted on the conflict of interest, there is no universally accepted definition of this phenomenon in both the literature and practice (Di Carlo, 2013).

Noteworthy, Schindler (2013) states that a clear definition of a conflict of interest and methods of dealing with it are possible only within the framework of the national legal system.

A conflict of interest does not necessarily have to be a personal one, which is another feature of the contemporary view of what constitutes a conflict of interest of interest. There is also the possibility of conflict arising from the self-interest of an institution or group (Kennedy, 2013).

Demmke et al. (2023) found that member states of the European Union are making concerted efforts to improve their systems for dealing with conflicts of interest in the context of professional integrity. An expanded definition of a conflict of interest, including personal, spouse, and family interests, stricter disclosure requirements, and more restrictions are all part of this package.

It is important to put conflict of interest in the context of a number of larger theoretical theories in order to make this research's ideas more solid. Principal-Agent Theory (Ross, 1973; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Moe, 1984; Eisenhardt, 1989; Thatcher and Sweet, 2002) underscores the difference between the interests of public officials (agents) and citizens (principals) and underscores the potential for ethical violations to arise as a result of information asymmetry and a lack of oversight. In this regard, conflicts of interest are perceived as predictable risks in agency relationships where incentives are not perfectly aligned.

Second, formal rules may be separated from practice, as explained by Neo-Institutionalism (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; March and Olsen, 1989; Scott, 2013). Conflict-of-interest policies don't always work when informal rules are in place or when official compliance is seen as more important than real change. In transitional nations, this viewpoint is particularly helpful in explaining the disconnect between stated anti-corruption initiatives and actual administrative culture.

The Public Value Theory is a complementary lens that looks at governance results other than following the rules. It asks whether institutions provide services and policies that improve public trust and societal wellbeing (Moore, 1995; Bozeman, 2007; Bryson et al., 2014). As part of reforms to public administration, this point of view pushes for more than just formal compliance. Instead, it stresses the importance of co-creating public value through ethical leadership, citizen involvement, and institutional responsiveness.

In Kazakhstan, official integrity mechanisms don't always have the support of the public. Focusing on public values may help change the way anti-corruption efforts are seen as legal exercises and instead as ways to build trust. This point of view is in line with the ideal of a values-based bureaucracy that encourages moral behavior not just through regulation but also through a shared purpose and principles.

New critical studies question the limits of rule-based reforms in public administration. For instance, Saputra et al. (2025) examine Indonesia's digitalization efforts and argue that, without strategic alignment and cross-sector collaboration, even ambitious initiatives may result in fragmented systems and limited impact. Their concept of a “digital service bubble” illustrates how rapid but uncoordinated technological adoption can lead to inefficiencies and erode public trust. Similar risks exist in Kazakhstan, where relying only on formal rules does not work well without broader coordination.

Simultaneously, some researchers concentrate on the conflict-of-interest nature and perceive it as an ethical concern.

According to Walter (1981) the only parts of the ethics legislation that must be considered are the requirements pertaining to financial disclosure, the blind trust restrictions, and “the revolving bar” doors.

McMunigal (1998) believes that the primary distinction between conflict of interest and corruption is that conflict of interest is a threat situation, whereas corruption is a behavior that causes harm.

Furthermore, Doig (2014) highlights that corruption involves either taking action or refraining from taking action in order to benefit the person providing an offer or incentive. Engaging in corrupt practices when making contracts can also result in negative consequences such as financial losses or a decline in the quality of services. Both are commonly linked to a conflict of interest, which occurs when officials or council members exploit their position to obtain an advantage in pursuing either financial or non-financial objectives. It is also assumed that this conflict of interest influences their official behavior.

According to Argandoña (2004), there are numerous situations where a conflict of interest arises, which might jeopardize the agent's fiduciary responsibilities and potentially harm someone, even if the law does not explicitly prohibit such conduct. In this scenario, it might be asserted that activity resulting from a conflict of interest is morally wrong.

Boyce and Davids (2009) also examine how conflict of interest affects society and emphasize the importance of fostering an ethical and organizational culture as one of the three primary regulatory approaches to conflict of interest.

In the same vein, Werhane and Doering (1995) earlier highlighted the moral dimension of the conflict of interest. Therefore, the authors have identified three distinct criteria for evaluating the ethical wrongdoing in the activities of individuals who disregard conflicts of interest. According to the authors, one way to analyze an activity is to consider it independently, without considering any conflicts of interest, and determine if it broke a moral rule.

Some researchers emphasize the importance of ethics codes in the effective public service and conflict of interest management (Di Carlo, 2013; Androniceanu, 2013; Mital, 2019; Suk Kim and Yun, 2017).

However, on two fronts, attempts to outlaw even the appearance of a conflict of interest are misguided. To begin, the inclusion of the appearance criteria in this way expands the prohibition in an unjustified way. Since the very definition of a conflict of interest incorporates an appearance standard, expansion is needless. An apparent conflict of interest is already included in the definition of a conflict, which is a collection of conditions that could lead to the appearance of improper influence. Secondly, a lot more situations will probably be prohibited if “appearance of” and “potential” conflicts are considered as separate from actual ones (Fung and Thompson, 2025).

Notably, many nations have been concerned about the corruption that might arise from conflicts of interest in public service. One school of thought holds that there are three distinct varieties of corruption: white corruption, which is obvious but sometimes overlooked; gray corruption, which is more difficult to spot in actual situations; and black corruption, which is widely known and punished. Conflicts of interest are one type of gray corruption among these three (Hue, 2020).

Materials and methods

The respondents in this survey included public servants from central state bodies in Kazakhstan, as well as local executive bodies from all regions. The research sample for the entire republic included 10255 public servants in managerial and executive roles, representing slightly over 10% of the general population of 90,000 individuals (self-sampling).

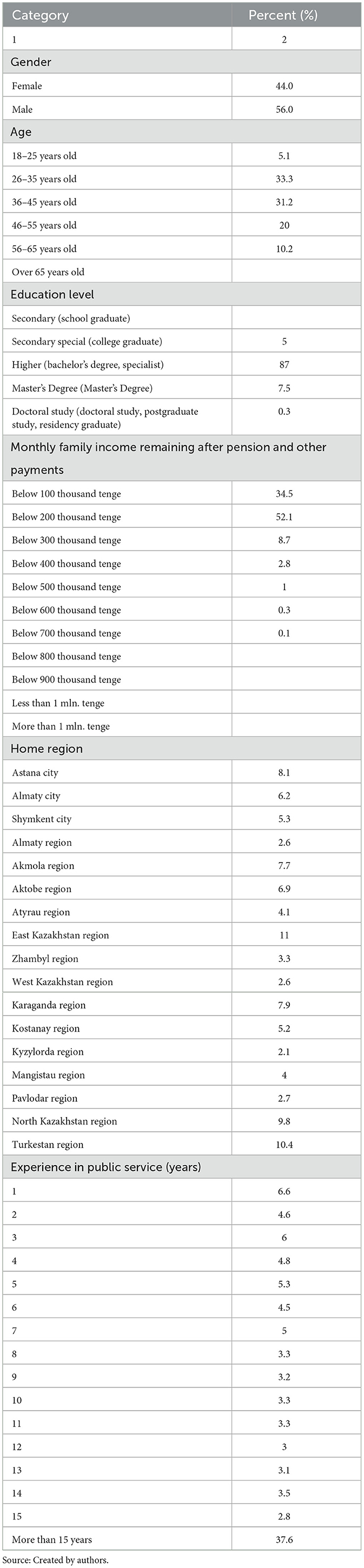

An online survey was administered in Kazakh and Russian through Google from November 2021 until February 2022. The participants came from diverse educational and socio-economic backgrounds. Table 1 displays the attributes of the complete sample. These socio-demographic characteristics offer important context for interpreting the empirical results presented in the following sections (Table 1).

Table 1 indicates that males constitute the majority of respondents, with a 56% share. Out of the total, 44% were female. The survey generally encompasses the respondents aged 18 to 65 and older. There are six primary age categories, with respondents aged 26 to 35 accounting for the largest percentage at 33.3%. The cohorts of 35 to 45 years and 46 to 55 years occupied the second and third positions, with 31.2% and 20%, respectively. The respondents aged 18 to 25 comprise the smallest cohort, accounting for 5.1%.

The vast majority of respondents possess a higher education, as evidenced by their Bachelor's degree (87%), Master's degree (7.5%), and Doctoral degree (0.3%). Meanwhile, 5% of respondents possess a college degree. It is noteworthy that the majority of the respondents has more than fifteen years of professional experience.

The questionnaire was divided into four main sections with respective questions regarding:

- The socio-demographic data of the respondents;

- The conceptual apparatus and key issues surrounding policy formation;

- The challenges related to policy formation and implementation, particularly in preventing conflicts of interest;

- Personal experiences to provide a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

This survey questionnaire was approved by Committee of Ethics at National School of Public Policy of the Academy of Public Administration under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

The obtained data were analyzed using R-studio software. This made it possible to create several regression models that take into account the correlation of variables to determine the factors that influence the perception of conflicts of interest by respondents, as well as to assess the current situation in the field of prevention and regulation of conflicts of interest.

All models were run using multiple linear regression. A stepwise methodology was used to select variables for each model. Output data for each model include the distribution of residuals, model coefficients, and measures of model reliability (F-test, degrees of freedom, and r-squared).

Results

The OECD attaches particular importance to issues of perception and regulation of conflicts of interest in the public service.

In many OECD countries, a broader framework is in place for all public authorities to follow when it comes to managing conflicts of interest in infrastructure projects. 64% percent of OECD countries (18 out of 28) have a policy or institutional framework addressing conflicts of interest solely for individuals tasked with infrastructure management (OECD, 2023).

In this context, it is essential to ascertain the precise nature of public servants' associations and their comprehension of the conflict of interests in order to effectively prevent a conflict of interest.

Below the finding results according to research questions are analyzed.

1. Regarding the perception of public servants on the subject of conflict of interest in the public service

Based on the findings of the research conducted, a sufficient number of respondents (22.8%) regard the conflict of interest as either outright corruption or a threat to corruption.

Moreover, 61.9% of respondents believe that the reason for the assumption of a conflict of interest on the part of public servants is the low level of wage.

It is evident that respondents view a conflict of interest as a corruption phenomenon since they point to low wages as the cause of such conflicts in the public service. In other words, the responses suggest that a public servant has a conflict of interest because, as a result of poor salary, they seek tangible benefits. While it may lead to corruption, a conflict of interest itself is not corrupt per se. This is the reason the declaration of interests was implemented as a measure to prevent corruption.

As an illustration Scherf (2024) states that online personal financial disclosures as a conflict-of-interest disclosure reduces disclosure acquisition costs for enforcement agents, thereby supporting local corruption enforcement.

Meanwhile, Demmke et al. (2023) argues that there are the tendencies toward politicizing ethical policies, ministers toleration of conflict of interest, and the unwillingness to oversee and penalize ministers' conflict of interest. In this regard, the researchers stress that less democratic and less rule of law performing states are more likely to embrace conflict of interest than more democratic and more rule of law performing systems.

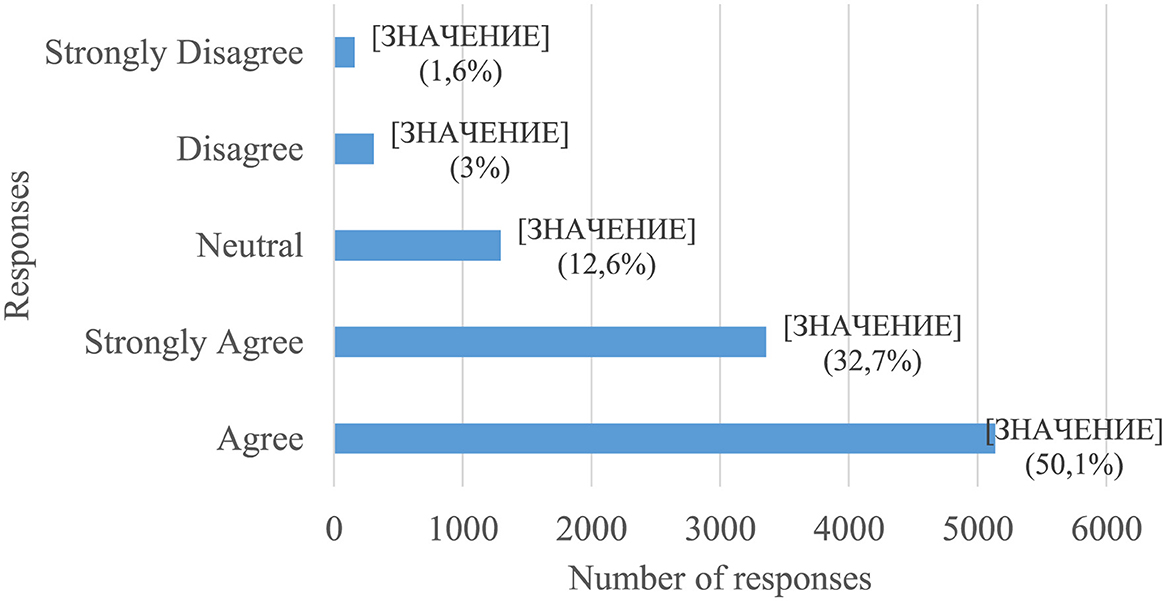

Meanwhile, the weakness of ethical values and self-awareness among public servants was indicated by 28.2% of respondents as a reason for conflicts of interest. This suggests that beyond formal rules, the ethical climate within public institutions plays a critical role in shaping behavior. At the same time, according to a Likert scale, 82.8% (8490) of public servants advocate for the development of ethical values in order to prevent conflicts of interest in the public service (Figure 1). These findings highlight a shared recognition among employees of the need to strengthen ethical foundations as part of conflict-of-interest regulation.

Figure 1. Likert scale. To prevent conflicts of interest in public service, it is necessary to develop ethical values among public servants. Source: Created by authors.

Odeh (2024) stresses that several profession-specific codes of ethics that are accessible to government employees at the local level reveals a harmony of public service principles, including the importance of building trust and working to advance the public interest. Though, there is a lack of consistency in the explanations of these values.

It follows from the above that most public servants perceive a conflict of interest in two aspects: both as a fact of corruption and an ethical violation.

2. Regarding the factors that shape the public servants' perceptions in relation the conflict-of-interest regulation policy

Kazakhstan has taken a number of steps in recent years to establish a framework of public service and anti-corruption laws, which encompasses the regulations regarding conflict of interest. Concerning that, public servants have been queried to assess in general the level of the conflict-of-interest policy.

It is noteworthy that the legislative level of regulation is rated as low by the majority of public servants (61.5%) (below 6 points out of 10).

The effectiveness of the policy measures implementation is also underestimated by 61.8% of respondents (below 6 points out of 10).

2.1 The factor of respondents' grasp of the concept

The subject of conflict of interest is addressed in several regulatory legal texts in Kazakhstan, including the Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Combating Corruption (2015), Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Public Service (2015), and Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on State Property (2011).

The conceptual framework of the mentioned normative legal actions varies in terms of both subject affiliation and the typical composition of circumstances.

Unlike the customary approach followed internationally, especially by international organizations, the conflict of interest in Kazakhstan is framed as a confrontation between private interests and official powers.

In turn, official powers refer to the rights and responsibilities that are defined by a particular public post. These powers are designed to help state entities achieve their aims and objectives, and are exercised by public officials in the course of their duties (Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on State Property, 2011).

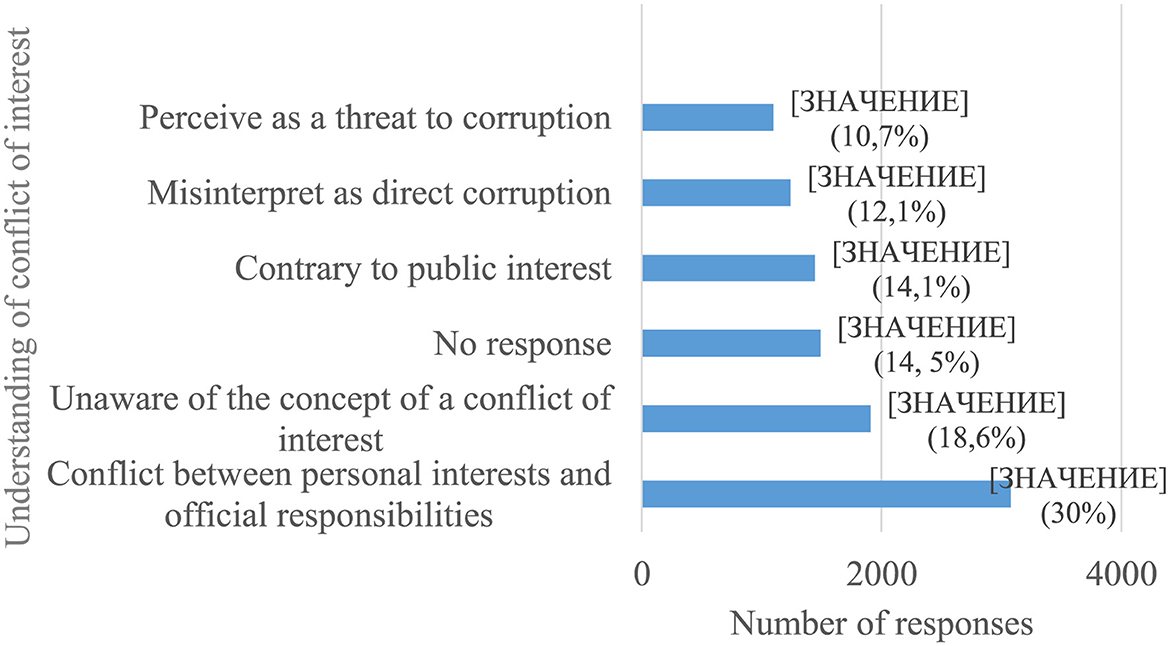

Figure 2 illustrates the wide range of public servants' interpretations of conflict of interest. While 30% of respondents correctly identify it as a conflict between personal interests and official responsibilities, a significant share demonstrates confusion or misunderstanding: 18.6% are unaware of the concept, 12.1% equate it with direct corruption, 10.7% see it as a threat to corruption, and 14.1% perceive it as contrary to the public interest. These discrepancies highlight the lack of conceptual clarity and unified understanding, which can significantly undermine the effectiveness of regulatory and ethical measures aimed at preventing conflicts of interest.

In reality, the proper perception and assessment of the current situation, as well as the effective prevention of conflicts of interest, are impeded by a lack of comprehension or a complete lack of understanding. These conclusions are derived from a regression analysis of the survey data.

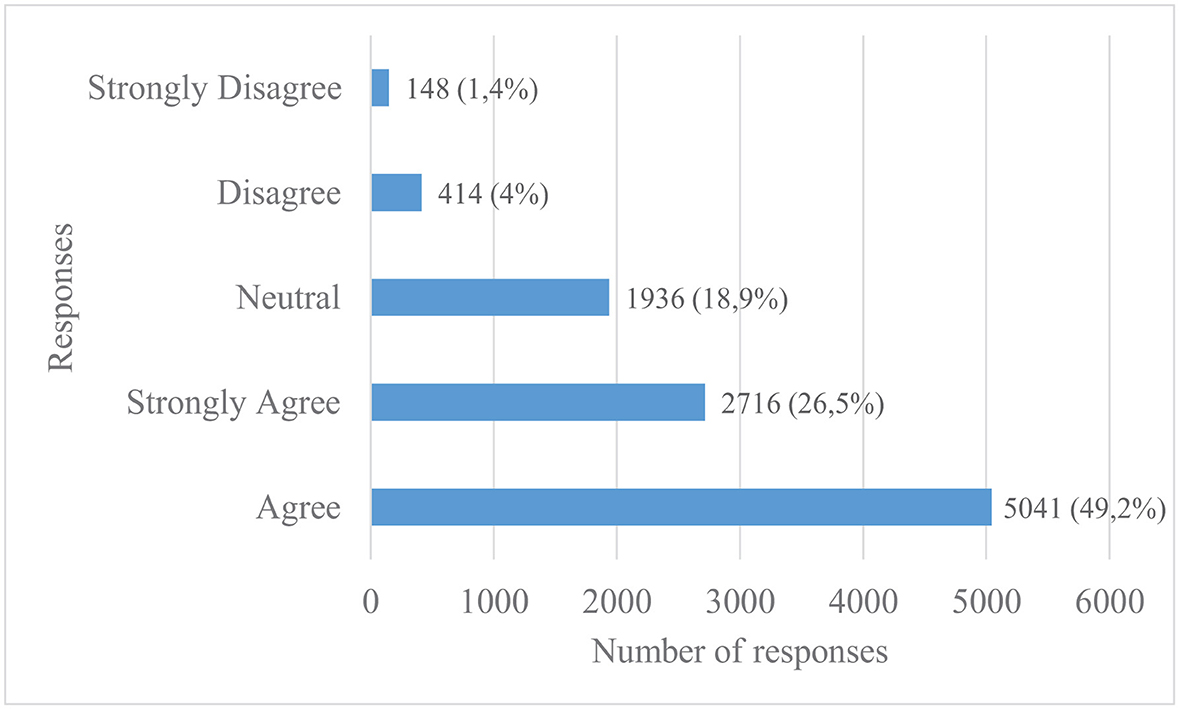

In addition, according to the Likert scale results, 75.6% (7757) of public servants consider it necessary to clarify or modify the conceptual framework of the “conflict of interest”. 18.9% of respondents are neutral, and 5.5% of respondents do not support clarifying or changing the conceptual framework (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Likert scale. It is necessary to clarify or modify the conceptual framework of the “conflict of interest”. Source: Created by authors.

These findings collectively point to a widespread recognition among public servants of the need for conceptual clarity in the regulation of conflicts of interest. The fact that over 75% of respondents support changes to the existing framework suggests not only gaps in legal and institutional definitions, but also a demand for more accessible and actionable guidance. Taken together with the results from Figures 1, 2 this underscores the importance of strengthening both the normative understanding and the ethical foundations of public service.

The influence of the independent variable on the dependent is observed by examining the regression-correlation relationship with respondents' assessment of on conflict-of-interest issues.

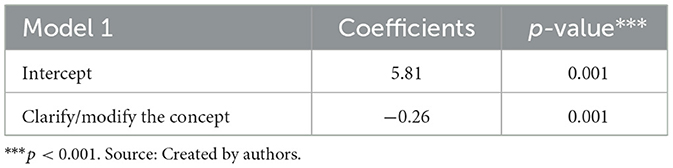

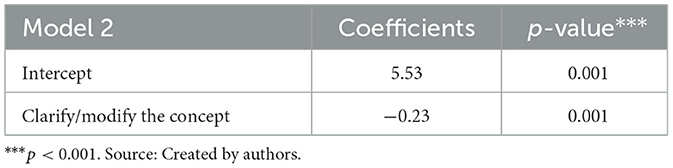

It is presumed that a 0.26 decrease in the evaluation of the regulation level will result from each increase in agreement with the statement of the need to clarify or modify the conceptual apparatus, while maintaining constant all forecast values (Table 2).

This finding reflects a broader pattern: respondents who support the revision of the conceptual framework tend to be more critical of existing regulation. Thus, the lack of clarity around the term “conflict of interest” may reduce perceived legitimacy and trust in regulatory mechanisms.

Table 3 shows that perceptions of policy implementation are also sensitive to conceptual clarity. Specifically, for each increase in agreement with the need to revise the definition of conflict of interest, the assessment of implementation decreases by 0.23 points (p < 0.001). This supports the conclusion that when the basic concept remains unclear, it undermines not only the regulation itself, but also how effectively it is carried out (Table 3).

Table 3. The result of the regression analysis (regarding the assessment of the policy implementation degree).

The main conclusion is predicated on the findings of regression analysis as follows:

Respondents who believe that the concept of conflict of interest needs to be clarified or revised tend to evaluate both the quality of regulation and the effectiveness of policy implementation more negatively. This suggests that insufficient or inaccurate understanding of the concept directly undermines trust in current policy.

2.2 The factor of respondents” education level

Another crucial aspect that needs attention is insufficient level of knowledge and competencies of public servants.

It is notably that the absence of pertinent knowledge and competencies was cited as the cause for weak regulation policy by 42.5% of public servants.

On top of that, a Likert scale was utilized to inquire how strongly people felt about the necessity of providing public servants with comprehensive training on how to avoid and handle conflicts of interest. Regarding this question, a significant majority, specifically 79% of respondents (8095) voted in favor.

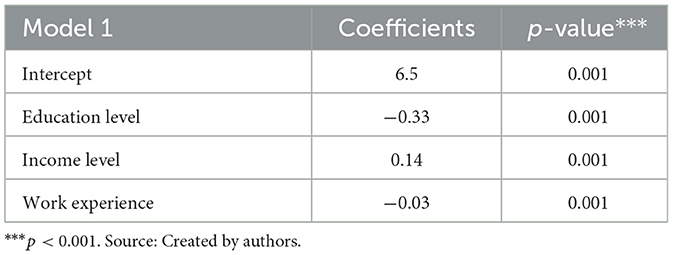

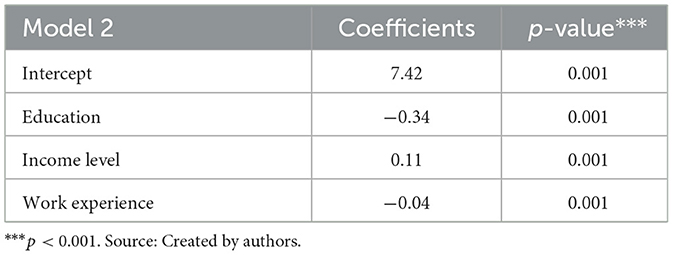

Moreover, findings from the regression analysis revealed the following outcomes. The respondents' knowledge, as proxied by education level, appears to have a negative impact on the assessment of policy formation regarding conflict-of-interest issues. It also negatively affects the evaluation of the effectiveness of current policy implementation in Kazakhstan.

As shown in Table 4, each incremental increase in education level is associated with a decrease in the assessment score of policy formation by 0.33 points (p < 0.001). While this might initially appear counterintuitive, the finding reflects a deeper, more critical perspective among more highly educated public servants. When public servants are better educated or receive more training, they may become more aware of high standards in governance — and more demanding of policy quality and integrity.

This relationship can be interpreted in several ways. For example, Principal–Agent Theory suggests that better-informed public servants may be more aware of the gap between official goals and what actually happens in practice, especially when the rules and motivations don't match. Similarly, if they've seen how things work in other countries or through ethics training, they may become more critical of local policies — especially when these seem more formal than effective.

In addition, Neo-Institutional theory points out that in transitional governance systems, official rules about conflict of interest often exist alongside informal practices that weaken how those rules work in reality. Public servants with higher education, who better understand both the formal policies and how things actually happen on the ground, may be more aware of this gap. That can make them more critical or doubtful about the system's effectiveness.

The positive correlation with income level (β = 0.14, p < 0.001) may indicate that those in higher-level or better-paid positions perceive greater involvement, or satisfaction with policy processes, perhaps due to greater access or proximity to decision-making. Work experience, meanwhile, has a small but significant negative effect (β = −0.03, p < 0.001), potentially reflecting disillusionment over time among those who have witnessed multiple cycles of reform with limited long-term impact.

Table 5 also shows a negative relationship between education and how respondents rate the effectiveness of policy implementation. With each higher level of education, the average score decreases by 0.34 points (p < 0.001). This suggests that more educated public servants tend to evaluate the system more critically when it comes to how conflict-of-interest rules are put into practice.

Table 5. Regression analysis results (regarding the assessment of the effectiveness of policy implementation).

This result may be explained by several factors. First, cognitive dissonance may arise when well-educated public servants observe a mismatch between official commitments and what is actually implemented. Second, in systems where routine bureaucratic practices emphasize rule-following over meaningful improvement, individuals with higher education may see policy measures as inconsistent or insufficient. Third, education can increase ethical awareness, making such individuals more likely to recognize subtle risks or indirect conflicts of interest that may go unnoticed by others.

The level of education plays a significant role in how public servants perceive conflict-of-interest policies in Kazakhstan. In both regression models, higher education is linked to lower satisfaction, more likely because educated officials tend to ask deeper questions and notice when real practice falls short of declared goals. This reflects Public Value Theory, which emphasizes that people inside the system care not only about rules, but about whether those rules work and whether they serve the public in a meaningful way.

It is important to recognize that education and conceptual understanding are not strictly separable. How people interpret what they've learned often depends on the organizational environment they work in—including what's expected of them, how leaders behave, and how ethics are taught in practice. So even if someone has a strong educational background, whether they become engaged or disillusioned with the system often depends on how their workplace supports ethical behavior day to day.

These findings suggest the need to go beyond technical compliance and foster an ethically responsive public administration. Reform efforts should focus not only on rules and procedures but also on building institutional trust, and embedding integrity into the broader organizational culture.

Discussion

The findings of this study shed light on how institutional settings influence the perception and effectiveness of conflict-of-interest regulation in Kazakhstan's public service. A conflict of interest in public service is a situation that can lead to an offense. This is a risk of corruption, but it is not a corruption per se. If a public servant makes a decision in favor of his or her personal interests due to a conflict of interest, corruption has occurred. Additionally, the conflict of interest persists if the public servant opts to fulfill his obligations and moral responsibilities.

According to the results of the analysis, the responses to the research questions as follows:

1. What is the perception of public servants on the subject of conflict of interest in the public service?

The analysis shows that public servants with higher levels of education are generally more critical of how conflict-of-interest rules are written and applied. This supports the logic of Principal–Agent Theory, which suggests that when people are better informed, they are more likely to notice the gap between formal policies and how things actually work. These results also highlight the limits of relying only on rule-based approaches in settings where informal practices, weak oversight, and strong top-down control are still common.

From the perspective of neo-institutional theory, this is not surprising. In countries like Kazakhstan, which are still going through institutional transition, formal rules often exist alongside informal habits and expectations. As a result, there can be a disconnect between what the rules say and how decisions are really made. In such systems, just having rules is not enough to build trust or ensure fair behavior.

To start, there are two levels of perceived conflict of interest among public servants, according to the poll results. First, as unethical; second, as corrupt or conducive to corruption.

Thus, the OECD recently has established public integrity indicators, which offer indicators in the following areas: strategy (8 indicators), accountability of public policy making (17 indicators) and effectiveness of internal control and risk management (11 indicators) (OECD, 2024b). Conflict of interest safeguards in practice are one of the indicators that point to accountability of public policy making (OECD, 2024c).

The above implies that the conflict of interest always relates to the issue of public integrity and ethics. As stated by Boyce and Davids (2009), one of the main three elements of regulatory approaches for conflict of interest is development of the ethical culture.

Demmke et al. (2020) emphasizes that the variety of codes demonstrates the importance of ethical systems and the need to fight and avoid corruption. This can be achieved not only by emphasizing strict legal punishments, but also by increasing awareness and providing ethical guidance.

Concurrently, public servants, recognizing the ethical aspect of a conflict of interest, believe that this is directly related to corruption. The majority of public servants point to low wages as the reason for the conflict of interests. This implies that a conflict of interest can become an additional income for a public servant. A variety of approaches are being considered as a solution to this problem.

As an example, Strelcenoks (2023) considers the artificial intelligence for the prevention of corruption and conflict of interest situations in the public service.

Many countries use anticorruption measures such as disclosing interests in order to prevent conflicts of interests.

Thus, Demmke et al. (2023) stress that EU member states are actively working to build more robust systems of professional integrity through the introduction of new regulations, stronger disclosure requirements, and broader definitions of conflict of interest (such as personal/spouse/family interest and revolving door).

2. What are the factors that shape the public servants' perceptions regarding the conflict-of-interest regulation policy?

Our analysis highlights two main factors that influence how public servants perceive the regulation of conflicts of interest: how well they understand the concept itself, and their level of education.

First, the survey shows that there is no common understanding of what a conflict of interest means. Respondents interpret it differently — some as a normal situation where duties overlap with personal interest, others as an ethical or even corrupt practice. This lack of conceptual clarity also appears in the national legal framework, where different laws and regulations define the term in inconsistent ways.

The results of our regression analysis support this observation. They show that a poor understanding of the concept is linked to more favorable evaluations of the existing system, whereas those with a clearer grasp of the issue tend to be more critical. In other words, the more precisely a public servant understands what a conflict of interest is, the more likely they are to see gaps and limitations in how it is currently regulated.

Second, the data indicate that higher levels of education are associated with more critical views of the policy. For each increase in education level, the evaluation of both the design and implementation of current regulations becomes more negative. This may reflect not only formal education but also broader exposure to ethical standards, and professional expectations.

This supports the logic of Principal–Agent Theory, which suggests that when people are better informed, they are more likely to notice the gap between formal policies and how things actually work. These results also highlight the limits of relying only on rule-based approaches in settings where informal practices, weak oversight, and strong top-down control are still common.

From the perspective of neo-institutional theory, this is not surprising. In countries like Kazakhstan, which are still going through institutional transition, formal rules often exist alongside informal habits and expectations. As a result, there can be a disconnect between what the rules say and how decisions are really made. In such systems, just having rules is not enough to build trust or ensure fair behavior.

Even when public servants know the rules, they may not feel encouraged or supported to follow them in practice. As Maesschalck (2004) notes, an integrity-based approach focuses on developing ethical judgment through ethics codes, training, discussions, and shared values. Our findings resonate with the view that although many public servants are aware of formal standards, the lack of educational measures and supportive ethical trainings often limits the practical effectiveness of values-based measures.

Overall, our results show that both conceptual understanding and education level influence how public servants assess conflict-of-interest regulation. When combined, these two factors shape a more demanding perspective. Respondents who both understand the idea clearly and have a higher level of education are more likely to notice shortcomings in current policies. As a result, they expect more effective and consistent approaches. This highlights the need to strengthen not only awareness, but also the quality of ethics education and the clarity of official definitions.

3. What is the most effective approach for addressing conflict of interest in light of the findings?

The entire world is divided into two conditional camps: those who adhere to the normative approach and policy of resolving conflicts of interest (restrictions, rules, sanctions) and those who adhere to a values-based approach (training, education, declaration). In general, modern trends imply as much decency (rules and standards) as possible (Demmke et al., 2020).

Heywood and Rose (2015) also observe that ethical issues in the public service are regulated in a variety of approaches. The first is based on values, the second is based on ensuring compliance with requirements. The authors conclude that formal rules are not a mature mechanism for common sense in the public sector. It is necessary to have a set of measures.

Similarly, Treviño et al. (1999) much earlier state that the combination of the two approaches is a decisive factor in effective activity.

Our findings confirm that compliance-based approaches may not work well in settings where informal practices, weak enforcement, and top-down control still shape how institutions function. In Kazakhstan, formal reforms often exist alongside long-standing informal arrangements, which leads to a gap between what the policies say and how they actually work in practice. When rules are enforced selectively or inconsistently, they lose their meaning and become more symbolic than effective.

This highlights the importance of understanding the broader institutional setting in which conflict-of-interest policies operate. Organizational culture, leadership, and the design of control mechanisms all influence how such policies are perceived and whether they lead to real change. Without a culture that supports ethical behavior, and leadership that models integrity, even well-crafted policies can fail to produce results on the ground.

In this regard, there needs to be a transparent code of conduct for public servants that spells out the public's expectations for how a public worker should act and makes it a disciplinary offense to declare and engage in a mismanaged conflict crisis (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2008).

Moreover, effective conflict-of-interest management depends not only on clear rules but also on strengthening ethical capacity within institutions. This includes sustained efforts to build ethical awareness, promote internal accountability, and create learning systems that help public servants handle difficult situations.

The findings of the analysis unequivocally suggest following measures:

- To apply combined approaches to the regulation of conflicts of interest at the state level, both on the basis of value- and compliance-based approaches;

- To conduct explanatory activities on the subject of fundamental nature and concept of the conflict of interest;

- To train and educate public servants on the ways to effectively prevent and regulate conflicts of interests.

Altogether, a hybrid strategy that integrates both formal legal mechanisms and values-based elements appears to be the most realistic and effective path forward for transitional systems like Kazakhstan's.

Conclusion

To summarize, this study examined how public servants in Kazakhstan perceive and respond to conflict-of-interest regulation in a system where formal requirements are in place, but where ethical values and practical understanding are not yet fully embedded. The findings show that while basic awareness of standards exists, perceptions of policy quality and fairness vary widely depending on education, conceptual understanding, and working conditions.

Although formal rules are in place, their implementation is often inconsistent. When there is uncertainty about how rules are applied or when ethical expectations are not reinforced in daily work, these measures may lose their practical value. In such cases, the gap between written policies and real experience becomes a barrier to effective regulation.

The findings also show that the effectiveness of conflict-of-interest regulation depends not only on the existence of formal rules and procedures, but also on how public servants understand and relate to them. When ethical concepts are poorly understood, or when there is a lack of awareness and training, rules may remain formal requirements without practical meaning. In such cases, even well-developed policies have limited influence. This underlines the importance of building a professional environment that supports ethical thinking, and promotes shared standards of behavior.

Managing conflicts of interest, therefore, requires not only formal procedures, but also a professional environment that supports integrity in everyday practice. This includes practical training, and an ethical culture that is consistently supported across different levels of the system. For Kazakhstan, a balanced approach that brings together legal tools and internal values appears to be the most promising direction for strengthening ethical behavior in the public service.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

In compliance with all applicable ethical guidelines and institutional policies, the Research Committee of the Academy of Public Administration under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan has examined and authorized this study (Protocol No. 2). Every precaution has been made to ensure the security and well-being of the study participants. The data has been collected and retained in compliance with privacy and confidentiality regulations, and all participants have provided their informed consent.

Author contributions

MN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Visualization. BB: Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant no. AP22787371).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, C. (1997). Values-based management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 11, 25–46. doi: 10.5465/ame.1997.9712024837

Androniceanu, A. (2013). Ethical values and the human resources behaviour in public management. Rev. Admin. Manage. Public 20, 49–61.

Argandoña, A. (2004). Conflicts of Interest: The Ethical Viewpoint. IESE Business School Working Paper No. 552. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=683784 or (Acessed April, 6 2005).

Bergstrom, L. (1970). What is a conflict of interest? J. Peace Res. 7, 197–217. doi: 10.1177/002234337000700302

Boyce, G., and Davids, C. (2009). Conflict of interest in policing and the public sector: ethics integrity and social accountability. Public Manag. Rev. 11, 601–640. doi: 10.1080/14719030902798255

Bozeman, B. (2007). Public Values and Public Interest: Counterbalancing Economic Individualism. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., and Bloomberg, L. (2014). Public value governance: moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Administr. Rev. 74, 445–456. doi: 10.1111/puar.12238

Cerrillo-i-Martinez, A. (2017). Beyond revolving doors: the prevention of conflicts of interests through regulation. Public Integr. 19, 357–373. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2016.1225479

Chapman, B. C. (2014). Conflict of interest and corruption in the states (Doctoral dissertation). Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

Commonwealth Secretariat (2008). Commonwealth anti-corruption project: conflict of interest. Commonw. Law Bull. 34, 347–351. doi: 10.1080/03050710802038452

Davids, C. (1998). Shaping public perceptions of police integrity: conflict of interest scenarios in fictional interpretations of policing. Curr. Issues Crime. Justice 9, 241–261. doi: 10.1080/10345329.1998.12036773

Davis, M., and Stark, A. (eds.), (2001). Conflict of Interest in the Professions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Demmke, C., Autioniemi, J., and Lenner, F. (2023). Explaining the popularity of integrity policies in times of critical governance—The case of conflicts of interest policies for ministers in the EU-member states. Public Integr. 25, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2021.1987056

Demmke, C., Paulini, M., Autioniemi, J., and Lenner, F. (2020). The Effectiveness of Conflict of Interest Policies in the EU-Member States. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Di Carlo, E. (2013). How much is really known about the meaning of the term “conflict of interest”? Int. J. Public Administr. 36, 884–896. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2013.794429

Doig, A. (2014). Roadworks ahead? Addressing fraud, corruption and conflict of interest in English local government. Local Gov. Stud. 40, 670–686. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2013.859140

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 57–74. doi: 10.2307/258191

Fleming, S. (2019). Corruption Costs Developing Countries $1.26 Trillion Every Year – Yet Half of EMEA Think It's Acceptable? World Economic Forum. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2019/12/corruption-global-problem-statistics-cost/ (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Fung, A., and Thompson, D. (2025). Conflict of interest in government: avoiding ethical and conceptual mistakes. Governance 38, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/gove.12870

Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre (2024). The Cost of Corruption. Giaccentre.org. Available online at: https://giaccentre.org/the-cost-of-corruption/#:~:text=The%20United%20Nations%20and%20World (Accessed August 18, 2025)

Gong, T., and Ren, J. (2013). Hard rules and soft constraints: regulating conflict of interest in China. J. Contemp. China 22, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2012.716941

Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan (2022). Anti-Corruption Policy of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2022–2026. (Presidential Decree No. 802), 2 February.

Heywood, P. M., and Rose, J. (2015). “The limits of rule governance,” in Ethics in Public Policy and Management, eds. A. Lawton, Z. van der Wal, and L. Huberts (London Routledge), 181–196. doi: 10.4324/9781315856865-11

Huberts, L. (2014). The Integrity of Governance: What It Is, What We Know, What Is Done and Where to go. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Huberts, L., and Van Montfort, A. (2020). “Integrity of governance: towards a system approach,” in Global Corruption and Ethics Management: Translating Theory into Action, ed. C. L. Jurkiewicz (London: Rowan and Littlefield), 184–193.

Hue, L. T. (2020). Improving public service culture with reduction of interest conflicts in State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) task enforcement in emerging markets – case in Vietnam. Management 24, 49–68. doi: 10.2478/manment-2019-0046

Jensen, M. C., and Meckling, W. H. (1976). Agency costs and the theory of the firm. J. Fin. Econ. 3, 305–360. doi: 10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Kaptein, M. (1998). “Ethics management,” in Ethics Management: Auditing and Developing the Ethical Content of Organizations (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 31–45.

Kennedy, S. S. (2013). Civic literacy and ethical public service: an underappreciated nexus. Public Integr. 15, 403–414. doi: 10.2753/PIN1099-9922150405

Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Combating Corruption (2015). On Combating Corruption (In Kazakh). Available online at: https://adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/Z1500000410 (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Public Service (2015). On Public Service (in Kazakh). Available online at: https://adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/Z1500000416 (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on State Property (2011). On State Property (In Kazakh). Available online at: https://adilet.zan.kz/kaz/docs/Z1100000413 (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Maesschalck, J. (2004). Approaches to ethics management in the public sector: a proposed extension of the compliance-integrity continuum. Public Integr. 7, 20–41. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2497549

March, J. G., and Olsen, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics. New York, NY: Free Press.

McMunigal, K. C. (1998). Distinguishing risk from harm in conflict of interest. Bus. Soc. Rev. 104, 519–529. doi: 10.1111/0045-3609.00019

Meyer, J. W., and Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 340–363. doi: 10.1086/226550

Mital, O. (2019). Conflict of interest: legal and ethical aspects in local self-government in Slovakia. Cent. Eur. Public Adm. Rev. 17, 69–87. doi: 10.17573/cepar.2019.1.04

Moe, T. M. (1984). The new economics of organization. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 28, 739–777. doi: 10.2307/2110997

Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

News.az (2021). Corruption in the European Union: Everything Is Under Control? Available online at: https://news.az/news/-corruption-in-the-european-union-everything-is-under-control (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Odeh, D. L. (2024). Professional codes of ethics for public administrators: what are they really telling us? Public Integr. 26, 143–155. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2023.2177042

OECD (2024a). Recommendation of the Council on OECD Legal Instruments: OECD Guidelines for Managing Conflict of Interest in The Public Service. Available online at: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/public/doc/130/130.en.pdf (Accessed August 18, 2025).

OECD (2024b). OECD Public Integrity Indicators. Available online at: https://oecd-public-integrity-indicators.org/ (Accessed August 18, 2025).

OECD (2024c). OECD Public Integrity Indicators: Indicator 1000097. Available online at: https://oecd-public-integrity-indicators.org/indicators/1000097 (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Roberts, R. (2009). The rise of compliance-based ethics management: implications for organizational ethics. Public Integr. 11, 261–278. doi: 10.2753/PIN1099-9922110305

Ross, S. A. (1973). The economic theory of agency: the principal's problem. Am. Econ. Rev. 63, 134–139.

Saputra, O. A., Nugroho, A., Tholibon, D. A., and Salam, R. (2025). Cross-institutional digitalisation and the digi-service bubble pitfalls in public sector transformation in Indonesia. J. Contemp. Gov. Public Policy 6, 81–96. doi: 10.46507/jcgpp.v6i1.682

Scherf, A. A. (2024). How do online conflict disclosures support enforcement? Evidence from personal financial disclosures and public corruption. Acc. Rev. 99, 455–487. doi: 10.2308/TAR-2021-0402

Schindler, B. (2013). “Conflict of interest and the administration of public affairs—a Swiss perspective,” in Conflict of Interest in Global Public and Corporate Governance, eds. J. B. Auby, E. Breen and T. Perroud (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 159–176. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139248945.013

Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Strelcenoks, J. (2023). Concept of implementation of artificial intelligence for the prevention of conflict of interest situations in the public sector, Acta Prosperitatis 14, 87–95. doi: 10.37804/1691-6077-2023-14-87-95

Suk Kim, P., and Yun, T. (2017). Strengthening public service ethics in government: the South Korean experience, Public Integr. 19, 607–623. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2017.1302278

Thatcher, M., and Sweet, A. S. (2002). Theory and practice of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions. West Eur. Polit. 25, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/713601583

Transparency International (2009). The Anti-Corruption Plain Language Guide. Available online at: https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/wps/ti/0018979/f_0018979_16239.pdf (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., Gibson, D. G., and Toffler, B. L. (1999). Managing ethics and legal compliance: what works and what hurts. Calif. Manag. Rev. 41, 131–151. doi: 10.2307/41165990

United Nations (2003). United Nations Convention Against Corruption. Available online at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/CAC/ (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Walter, J. J. (1981). The Ethics in Government Act conflict of interest laws and presidential recruiting. Public Administr. Rev. 41, 659–665. doi: 10.2307/975742

Weaver, G. R., and Treviño, L. K. (1999). Compliance and values oriented ethics programs: influences on employees' attitudes and behavior. Bus. Ethics Q. 9, 315–335. doi: 10.2307/3857477

Keywords: public administration, public service, conflict of interest, anti-corruption policy, ethics, public integrity

Citation: Nauryzbek M and Bokayev B (2025) Navigating conflict of interest in public service: lessons from Kazakhstan. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1640250. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1640250

Received: 03 June 2025; Accepted: 08 August 2025;

Published: 03 September 2025.

Edited by:

Andi Luhur Prianto, Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Mergen Dyussenov, Astana IT University, KazakhstanSaddam Rassanjani, Syiah Kuala University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Nauryzbek and Bokayev. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baurzhan Bokayev, YmJva2F5ZXZAc3lyLmVkdQ==

‡ORCID: Madina Nauryzbek orcid.org/0009-0002-1576-1913

Baurzhan Bokayev orcid.org/0000-0002-1037-7085

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Madina Nauryzbek

Madina Nauryzbek Baurzhan Bokayev2*†‡

Baurzhan Bokayev2*†‡