- Hong Kong Metropolitan University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Introduction: The evolving relationship between the European Union (EU) and China has become a defining feature of global geopolitical dynamics in the post-COVID-19 era. This paper examines shifts in EU-China relations since 2013, focusing on the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the context of broader international developments, including the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical crises, and shifting strategic priorities.

Methods: A multi-method qualitative approach is employed, incorporating comparative case studies of four countries (Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Serbia) alongside descriptive analysis of trade, investment, and participation data from 2013 to 2024. Statistical data from Eurostat and other sources are used to complement qualitative insights on economic and political trends shaping EU-China interactions.

Results: Findings reveal a significant transformation in the trajectory of EU-China relations. The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a critical juncture, accelerating a shift from pragmatic economic cooperation toward heightened strategic caution and risk aversion. While China’s BRI facilitated development opportunities, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, divergent political and economic interests across EU member states led to varied engagement levels. Germany and Italy adopted cautious, economic-first approaches, while Hungary and Serbia pursued deeper ties with China amid democratic backsliding and strategic ambiguity. Trade between the EU and China expanded during the BRI era, with imports from China increasing notably during the pandemic, although trade imbalances persist. The EU’s internal divisions and the intensifying US-China rivalry complicate cohesive EU strategies toward China.

Discussion: The complex interplay of ideological divergence, security concerns, and domestic political factors result in a fragmented and ambivalent EU-China relationship. The BRI’s uneven uptake across Europe reflects both China’s targeted geopolitical strategy and the EU’s multi-level governance challenges. The emerging post-pandemic world order is marked by strategic competition intertwined with economic interdependence, requiring nuanced diplomatic balancing by European actors. This analysis underscores the need for differentiated policy responses within the EU and highlights ongoing shifts in global power structures influenced by China’s expanding global role.

1 Introduction

In the 21st century, China continues to expand its global influence, particularly in both political and economic spheres. Under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, China has pursued the enhancement of its “comprehensive national power” while advocating for the establishment of a “community of common destiny” (Tobin, 2018). Among its strategic initiatives, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, stands out as a cornerstone of China’s global engagement. The BRI promotes extensive cooperation across various domains, including economic development and infrastructure construction projects (see Jones, 2021; Wong and Downes, 2024). Alongside the BRI, other initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) further underscore China’s growing influence, with over 100 member countries spanning both the Global South and the Global North alike. These initiatives challenge the existing international order, including US-led frameworks such as the World Bank (see Lin, 2022; Ong, 2017; Qian et al., 2023). China’s rise is reflected in its economic trajectory, having been the world’s second-largest economy after the United States since 2010.

In response, the European Union (EU) has sought to deepen its engagement with China, establishing a “strategic framework for the enhanced partnership” to access new markets and foster cooperation (see Qingjiang, 2012). Telò (2021) highlights the EU’s comprehensive agreement on investment with China, which sparked controversy due to its implications for diplomatic relations and the EU’s supranational governance framework, as embodied in the Lisbon Treaty. As a political and economic entity with shared sovereignty, the EU has positioned itself as a key actor in navigating the complexities of its relationship with China. While China-led initiatives such as the BRI have fostered positive cooperation, they have also introduced a sense of competition, particularly in areas such as markets, technology, and cybersecurity.

This competitive dynamic has extended to security concerns, as reflected in the EU’s adoption of a “de-risking” strategy under the leadership of President Ursula von der Leyen (Politi, 2023). These tensions underscore the broader struggle for global leadership and influence, which is further complicated by the EU’s engagement in an increasingly complex global order. First, the evolving US-China relationship continues to shape global approaches to key issues (see Ross et al., 2010).

Second, ongoing crises such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict reveal divergent positions between the EU (and its member states) and China in addressing international challenges (see Ding and Ekman, 2024). Third, the EU has frequently clashed with China on issues such as human rights, intellectual property protection, and domestic governance, often voicing criticism of China’s policies (see Men, 2011). The COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) profoundly impacted societies worldwide, exposing stark differences in how China and Western countries responded to the crisis. The pandemic, coupled with shifting geopolitical dynamics such as the Russia-Ukraine war, has catalyzed the emergence of a new global order.

Against this backdrop, this paper investigates EU-China relations in the “post-COVID-19 world order,” with a focus on the evolving diplomatic strategies of both actors.

The main original argument of our paper is that the COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally transformed the trajectory of EU-China relations, marking a decisive shift from a period of pragmatic economic cooperation—exemplified by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—to an era defined by heightened strategic caution, risk management, and ideological divergence.

While China’s BRI project initially fostered opportunities for partnership and development across Europe, the combined effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising geopolitical tensions (including the Russia-Ukraine conflict and US-China rivalry) and persistent concerns over security, human rights, and technological competition have prompted the EU to recalibrate its approach towards China. As a result, EU-China relations are now characterized by a more complex, ambivalent, and sometimes adversarial dynamic, with individual European countries adopting divergent strategies in response to China’s growing global influence. This evolution not only reflects the changing balance of power in the international system but also signals the emergence of a more fragmented, polarized and contested post-pandemic world order.

Therefore, there are five main features of our original argument. Firstly, the COVID-19 pandemic is identified as the turning point (critical juncture) that has accelerated the transformation of EU-China relations. Secondly, the relationship has shifted from co-operation to caution (risk aversion). The wider EU-China relationship has shifted from mutual economic benefit (via the BRI and international trade) to increased skepticism and strategic “de-risking.” Thirdly, drivers of change have included unexpected geopolitical crises, such as the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War, alongside ideological differences, and security concerns that have deepened the divide.

Fourthly, there exists widespread divergence across EU member states. Several EU member states have now pursued varied approaches to China, reflecting differing (a) national interests and (b) risk perceptions. Fifth and finally, there are widespread global implications resulting from the declining EU-China relationship in the post-pandemic era. These developments illustrate broader shifts in the global order, with EU-China relations serving as a microcosm of wider systemic change globally.

2 Literature review

This paper examines the post-COVID-19 world order for two main reasons. First, the COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the most significant global public health crises in modern history, profoundly influencing politics, economics, and various other domains. As a result, the post-pandemic international order is likely to be reshaped by the far-reaching effects of the pandemic (see Downes, 2023). Second, this research focuses on EU-China relations within the context of evolving global dynamics, including Brexit and the US-China trade war. Given the economic interests and strategic capabilities of both actors, EU-China relations occupy a central role in the broader framework of major global powers. Furthermore, these geopolitical tensions have introduced both potential and tangible obstacles to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its associated projects. By analyzing the impacts of these challenges—ranging from pandemic-related disruptions to economic uncertainties—this paper aims to explore how they influence the BRI and, more broadly, the trajectory of EU-China diplomatic relations.

2.1 The impact of the BRI project since 2013 on the EU-China relations

Cooperation between China and the European Union (EU) is of significant importance both economically and politically. For China, the EU represents a potential alternative partner, while China simultaneously seeks to reduce its reliance on the EU (Mrozowska, 2022). However, the relationship between the two entities involves inherent trade-offs. For example, while China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) emphasizes investment and economic activities, the EU’s approach extends beyond economic considerations, incorporating political factors such as human rights. Although the BRI presents numerous opportunities, it also raises concerns among EU member states (Jones, 2021; Wong and Downes, 2024). The differing political systems and ideologies of China and the EU fundamentally shape their respective decision-making processes.

Wong and Downes (2024) describe the Belt and Road Initiative, which was launched in 2013 and now involves over 100 countries in the development of “economic corridors.” The BRI is widely recognized as a China-led effort to expand its power and influence in geoeconomic spheres (Beeson and Crawford, 2023). Proactive narratives such as the “China Model” and the “Great Game” reflect China’s confidence in spearheading major projects like the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative (Blanchard, 2017, p. 249). Łasak and van der Linden (2019) analyze the broader implications of the BRI, comparing it to the Marshall Plan—a U.S.-led economic assistance program for European countries. They argue that the BRI serves as a strategic tool for China to: (a) address domestic overcapacity by promoting its products; (b) advance the internationalization of the RMB; and (c) counterbalance U.S. influence in both economic and regional spheres, particularly in the Asia-Pacific and Europe.

Overall, the BRI can be viewed as a comprehensive initiative encompassing business, trade, energy, and infrastructure development, while fostering foreign capital exchange between regions (Bhuiyan and Beraha, 2022, p. 50; Huang, 2016). In examining the participation of EU member states in the BRI, it is also important to consider the role of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the second-largest Chinese-led multilateral development institution headquartered in Beijing (Zhao, 2022). The AIIB provides financing to support regional development in the Asia-Pacific and aims to facilitate economic growth by “opening up for business” (Ong, 2017). Ong (2017) further explores whether the AIIB embodies “Asian Values” and the “China Approach” through its innovative multilateral framework in Asia.

2.2 Dynamics between China & the European Union under the BRI project

Since the 2000s, economic trade between the European Union (EU) and China has steadily increased. Between 2008 and 2017, EU foreign direct investment (FDI) in China surged by an impressive 225% (Telò, 2021). However, recent years have seen a decline in EU investments in China, accompanied by a rise in Chinese FDI in Europe (Telò, 2021). This shift reflects a proportional decrease in the EU’s economic involvement in China. European investors have expressed concerns about market access, regulatory barriers, discrimination, investor protection, and intellectual property rights, which may explain the downward trend in EU business investments in China (Telò, 2021). Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated public health policies have impacted China’s economic development and growth strategies, prompting scholars to consider factors beyond the pandemic’s immediate effects in their analyses of China’s political economy (Šebeňa, 2023).

Scholars examining China’s political economy often highlight the government’s self-perception, which operates under a “dual identity” framework. China views itself as both a global power and a developing nation, a status that carries significant implications for its role in international affairs and its economic ambitions (Zhang, 2009). Meanwhile, the Brexit Referendum in 2016 has subtly altered the dynamics between the EU and the UK, creating new diplomatic opportunities and challenges for China. The future of UK-China relations will depend on successful negotiations between London and Brussels, with trade, market competition, and regulatory measures emerging as key areas of focus (Yu, 2017).

These discussions also reflect broader EU concerns about trade imbalances and technological competition, particularly in sectors such as electric vehicles (Yu, 2017; Scicluna, 2024).

The competitive landscape between the EU and China is especially pronounced in the technology sector, including the electric vehicle industry. While some EU member states oppose tariff measures targeting China’s electric vehicle exports, they simultaneously benefit from exporting luxury cars to China (Lahiri, 2024; Scicluna, 2024). Beyond economic competition, EU-China relations are shaped by political and ideological differences. China emphasizes sovereignty and a strong state in its governance model, whereas the EU prioritizes transparency and democratic principles (Gurol, 2022).

Human rights concerns remain a central point of contention in EU-China relations. EU member states have consistently criticized China’s human rights record at the United Nations (Men, 2011), creating significant obstacles to the development of common ground (Politi, 2023; Men, 2011). For instance, the EU Parliament’s 2005 decision to uphold an arms embargo against China in response to human rights violations underscores these ideological divides (Men, 2011).

The evolving security landscape and the EU’s “de-risking” strategy, articulated by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, are expected to further influence EU-China relations (Politi, 2023). This cautious approach reflects growing concerns about China’s geopolitical influence, particularly in light of recent global developments. Ding and Ekman (2024) observe a tendency to frame China and Russia as authoritarian allies since the inauguration of U.S. President Joe Biden, highlighting broader ideological conflicts in the global order. The EU has sought to exert economic pressure on China to clarify its position on the Russia-Ukraine conflict (Ding and Ekman, 2024).

In contrast, China defends its stance by invoking principles of non-interference and emphasizing its commitment to preventing nuclear conflict (Yu, 2024). This approach positions China as less confrontational compared to Russia and North Korea. Contin Trillo-Figueroa and Downes (2023) outline two potential strategies for the EU in navigating its relationship with China: (a) pragmatic engagement or (b) alignment with the United States.

2.3 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Trauner (2022) examines the repercussions of COVID-19, highlighting China’s zero-tolerance strategy, which was characterized by strict lockdowns, border controls, and rigorous quarantine measures. In contrast, the European Union (EU) adopted a more targeted approach, focusing on health services and vaccination programs. Both China and EU member states experienced significant disruptions due to the pandemic, including trade barriers stemming from cargo and travel regulations. Despite these challenges, Mrozowska (2022) noted an increase in EU-China trade turnover during the pandemic, underscoring the resilience of economic ties between the two regions.

The pandemic’s impact extended beyond trade, severely affecting global tourism—one of the sectors hardest hit by prolonged quarantine measures and travel restrictions. Prior to COVID-19, the number of tourists traveling between the EU and China had been steadily rising since 2015. However, the pandemic forced China to prioritize virus prevention, implementing strict visa restrictions and quarantine protocols (Trauner, 2022). These measures led to bans on tourists, foreign workers, and business travelers, prompting many to leave China (Trauner, 2022).

The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic are far-reaching, influencing both domestic politics and transnational relations. Studies examining EU member states’ perceptions of China in the post-pandemic era reveal shifting attitudes. For instance, the polarization of Czech politics in light of the evolving relationship with China during the pandemic, highlighting tensions between both nationalist and globalist perspectives.

2.4 China’s alternative in the context of the new global order & tensions

The firm friendship between China and Russia, coupled with the expansion of BRICS (BRICS+) underscores a shift in global power dynamics. BRICS, an alliance aimed at amplifying the influence of emerging economies on the international stage, currently represents 45% of the world’s population and 28% of the global economy (BBC, 2024a, 2024b). While BRICS has become increasingly significant in China’s foreign cooperation efforts, this suggests that China does not place the European Union (EU) in the same strategic category, as no EU member state is part of BRICS.

No EU member state is part of the BRICS, which reflects both the self-definition of BRICS as a counterweight to Western influence and the EU’s alignment with established Western-led institutions (Downes, 2023; Wong and Downes, 2024). China’s foreign policy, especially through the BRI and BRICS, has prioritized partnerships with countries in the Global South, often characterized by less stringent governance standards and greater openness to Chinese investment (Jones, 2021).

The EU’s normative frameworks (liberal democracy, human rights and the rule of law) and its close ties to the US and NATO fundamentally differentiate it from the BRICS coalition, which is explicitly positioned as an alternative to Western hegemony (Gurol, 2022; Ding and Ekman, 2024). China’s diplomatic rhetoric and investment patterns underscore a deliberate strategy to deepen ties with BRICS and Global South partners, while EU-China relations remain cautious, competitive, and often contentious (Wong and Downes, 2024).

The expansion of BRICS has continued post-pandemic, with Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the UAE joining the bloc in 2024. Other countries, such as Thailand, are also approaching membership (The Kyiv Independent, 2024). Malaysia has expressed interest in joining BRICS, and projections indicate that by 2030, the bloc could collectively account for 40% of global GDP and represent 3.5 billion people, or 45% of the world’s population (Eurasia Business News, 2024).

As of early 2025, nine additional nations, including Thailand and Malaysia, have officially joined BRICS. This expansion now includes Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia—the three largest economies within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This trend highlights the growing cooperation among countries in the Global South, as all BRICS nations are recognized as part of the Global South. The potential synergy between BRICS and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) further underscores the bloc’s focus on South–South cooperation. The BRI serves as a framework to enhance development across the Global South while emphasizing China’s leadership and responsibility in fostering economic growth and connectivity (Zhao, 2024, p. 171). By promoting South–South cooperation, BRICS and the BRI collectively aim to reshape global development paradigms and challenge traditional Western-dominated frameworks.

3 Methodology

The paper adopts a multi-method qualitative approach centered on comparative case studies. The primary focus of the paper is on the evolving relationship between the European Union (EU) and China, particularly under the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and in the context of the post-COVID-19 world order. Firstly, the methodology combines comparative qualitative case studies in examining four countries (Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Serbia) are examined in depth to illustrate the diversity of European responses to China and the BRI. These cases are selected to represent a broad spectrum of political, economic, and geographical contexts within and outside the EU.

Secondly, the methodology draws on a descriptive analysis, in tracking the evolution of EU-China relations over time. Furthermore, the paper tracks the evolution of EU-China relations over time, focusing on key turning points (critical junctures) such as the launch of the BRI (2013), the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022) and recent geopolitical developments (2022–2024). Thirdly, statistical data is drawn on from Eurostat and other sources for trade flows and investment figures. This provides a more objective perspective overall and complements the main qualitative focus of our paper.

The empirical analysis in this paper covers the period from the early 2010’s to the end of 2024, with particular emphasis on two main phases:

(1) The BRI launch and expansion (2013–2019): To assess the initial impact and response to China’s strategic outreach, vis-à-vis EU-China relations.

(2) The COVID-19 pandemic & the post-pandemic era (2020–2024): To analyze how the pandemic and subsequent geopolitical developments have reshaped the dynamics of engagement.

There are two main justifications for why we focus on the selected timeframes in our paper. Firstly, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a major external shock, profoundly affecting trade, diplomacy, and perceptions on both sides, vis-à-vis EU-China relations. Secondly, the period up to the end of 2024 allows inclusion of the latest developments, such as Italy’s withdrawal from the BRI in late 2023 and the expansion of China-led initiatives.

4 Analysis

This paper aims to explore the evolving EU-China relationship in the post-COVID-19 era, focusing on the pivotal changes occurring under the overarching theme of China’s BRI project. Our analysis will examine how EU countries have engaged with China’s BRI framework, both formally and informally, providing an in-depth assessment of China-EU relations within the context of the BRI.

Specifically, we will describe the current state of affairs and analyze the participation of European countries in China-led organizations and frameworks, such as the BRI, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the China-Central and Eastern European Cooperation (CEEC/14 + 1). For comparative purposes, we will also consider the involvement of non-EU countries in these initiatives.

The paper will be structured around three key areas of analysis.

4.1 Participation of EU countries in the BRI & other China-led organizations and projects

This section will explore the extent and nature of EU member states’ involvement in China’s BRI and other China-led initiatives. It will assess formal agreements, informal collaborations, and the strategic motivations behind such participation.

4.2 Examination of trade, cooperation & investment in the BRI era

We will analyze the trajectory of economic cooperation and trade between China and the EU, particularly since the launch of the BRI in 2013. This section will focus on investment flows, the number of joint projects, and the overall economic impact of the BRI on EU-China relations.

4.3 Case study analysis

To provide a nuanced understanding of the BRI’s impact and the shifting global order, we will conduct case studies of four European countries. These case studies will highlight the varying levels of engagement, benefits, and challenges associated with the BRI.

Through this multi-faceted approach, the paper aims to shed light on the complexities of EU-China relations in the context of the BRI and the broader changes in the global order. By analyzing both EU and non-EU countries’ participation, we seek to provide a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics shaping China’s influence in Europe and beyond.

The German case study will elucidate the nation’s strategic approach towards its economic collaboration and competition with China. As a central player among European countries, Germany’s stance towards China encompasses not only economic dimensions but also extends to global strategic considerations and security domains. This narrative will offer insights into how Germany navigates its multifaceted relationship with China while playing a pivotal role within the European landscape.

The Hungarian case exemplifies Hungary’s active participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) within Europe, despite facing external criticism for democratic backsliding. Despite these challenges, Hungary maintains positive relations with China. In contrast, the Italian case illustrates the evolving dynamics between Rome and Beijing, culminating in Italy’s withdrawal from the BRI in late 2023. Moving beyond the EU, Serbia’s case highlights non-EU nations’ efforts to enhance collaboration and ties with China. Additionally, the Serbian case study sheds light on China’s strategic positioning in the broader Balkans region.

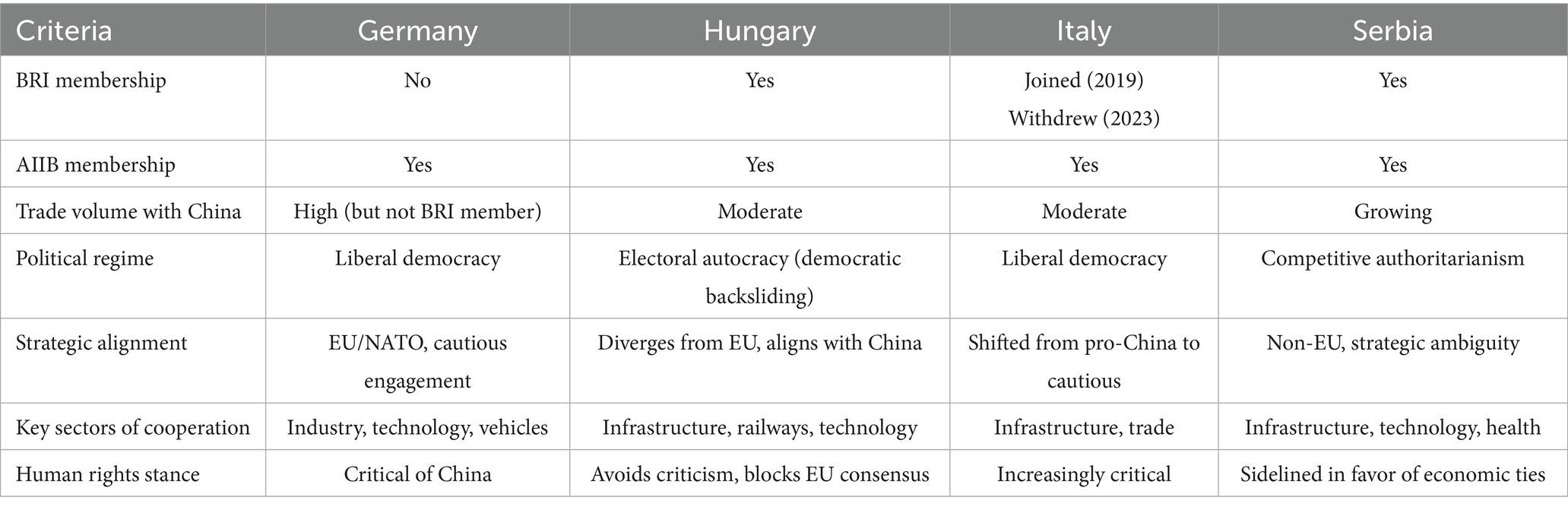

Methodological rigor is ensured in the paper. The comparative case selection ensures diversity in regime type, EU membership status, alongside levels of engagement with China. In addition, the descriptive analysis allows us to identify specific mechanisms and turning points in the wider evolution of EU-China relations. The case studies explanatory power is now enhanced by a more systematic, analytical comparison alongside key criteria such as (a) BRI/AIIB membership, (b) trade volume, (c) political regime type, and (d) strategic alignment (see Wong and Downes, 2024; Telò, 2021).

For example, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Serbia each display distinct patterns of engagement with China, shaped by their domestic political systems and economic interests (Gurol, 2022; Wong and Downes, 2024). This comparative table below underscores the diversity of motivations and outcomes, from Germany’s risk-averse, economically pragmatic approach to Hungary and Serbia’s transactional, regime-compatible engagement, alongside Italy’s unique political volatility that is shaped by domestic politics (Gurol, 2022; Wong and Downes, 2024). Table 1 outlines the core background information of four cases in our research.

4.4 Participation of EU countries in the BRI & other China-led organizations and projects

Several agreements between the EU and other countries illustrate that certain aspects of sovereignty are derived from the EU level (supranationalism). The Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) grants the EU Commission exclusive competence over foreign direct investment, replacing previous bilateral investment treaties (Telò, 2021). Thus, the EU’s focus is not on traditional bilateral agreements but on a comprehensive regulatory framework (Telò, 2021). This perspective allows for the examination of interactions between EU member states and other nations as a unified entity. Nevertheless, we have collected the membership of BRI and AAIB in Europe and found the phenomenon of “overlapping membership” in (1) the European Union; (2) the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); (3) the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

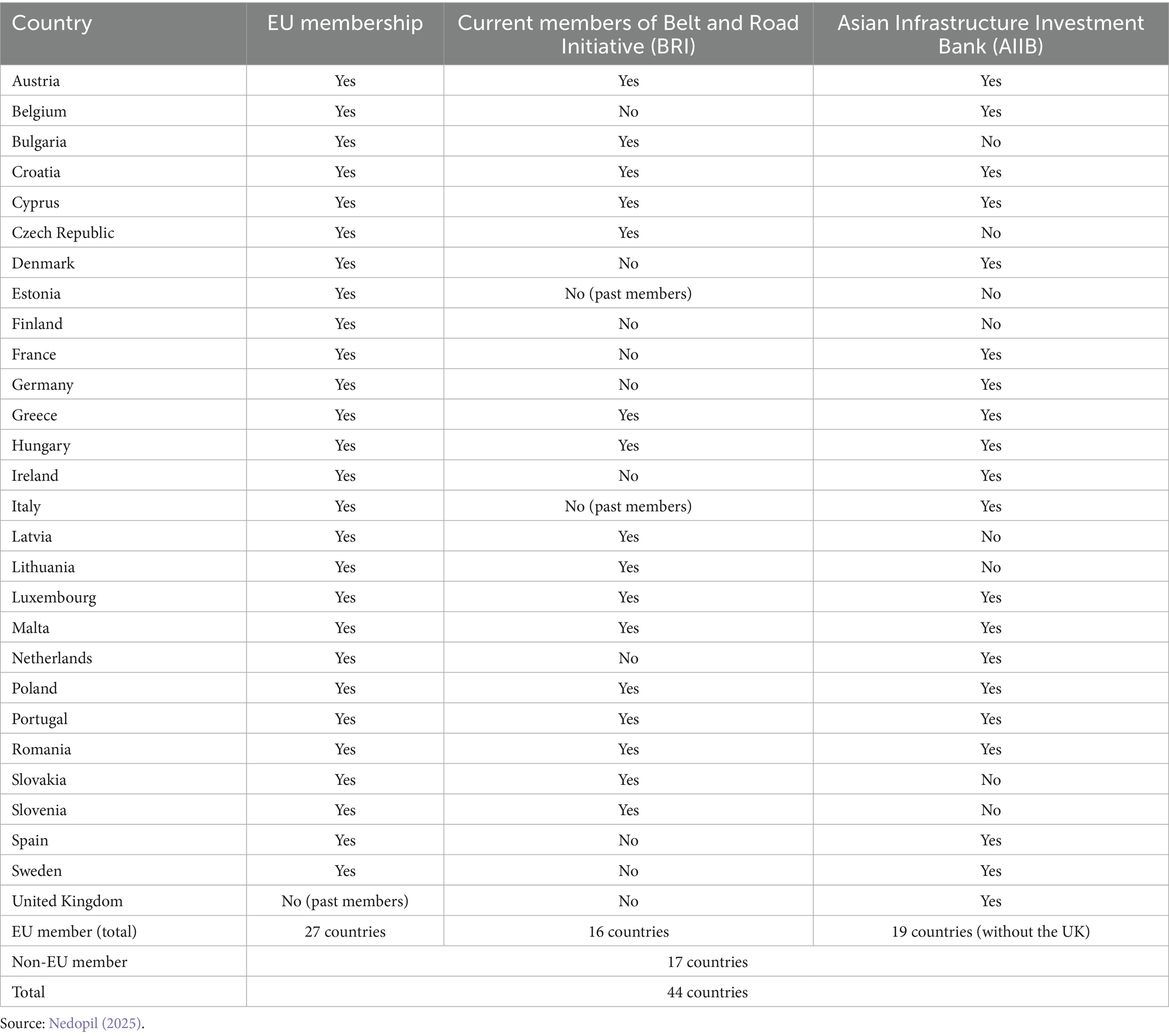

To examine the popularity of such Chinese-led initiatives and organizations, Lin (2022) outlines 147 countries that have signed the agreement with China (as of January 2022). The AIIB, for example, has been joined by 104 countries, includes countries from different continents and covers most developed countries except the US and Japan. Table 1 outlines the membership of such an organization and two major China-led programs, focusing mainly on the participation of EU members in BRI and AIIB until the end of 2024.

From the data presented in Table 2, we have analyzed the participation of the 27 EU member states (as of the end of 2024) in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Among these, 16 EU countries are current members of the BRI, while 19 EU member states hold varying voting and subscription rights within the AIIB. Upon examining “overlapping membership,” we identified 10 EU countries that are members of both the BRI and the AIIB: Austria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Portugal, and Romania. Conversely, Estonia and Finland are the only EU members that have not joined either initiative. Notably, Estonia, like Italy, has withdrawn from the BRI.

Regarding the United Kingdom, which formally exited the European Union in 2020, its relationship with China has undergone significant shifts. Historically, the UK-China relationship was described positively, with terms such as the “golden era” (Turner, 2018). Anderlini et al. (2015) argue that the UK’s decision to join the AIIB was pragmatic, despite strong opposition from the United States. This move signaled the UK’s willingness to diverge from US policy and indirectly influenced other European countries to join the AIIB. As of now, only the US and Japan, among major developed economies, have refrained from applying for AIIB membership.

However, the UK’s stance towards China has evolved, particularly after 2019, with skepticism surrounding the BRI and a broader view of China as a “systemic challenge” (Ashbee, 2024, pp. 9–10). Brexit marked a turning point in UK foreign policy (cf. Hearne and de Ruyter, 2019), and Summers (2022) highlights increasing contestation in UK-China relations due to issues such as Hong Kong and tensions in areas such as 5G networks and technological risks.

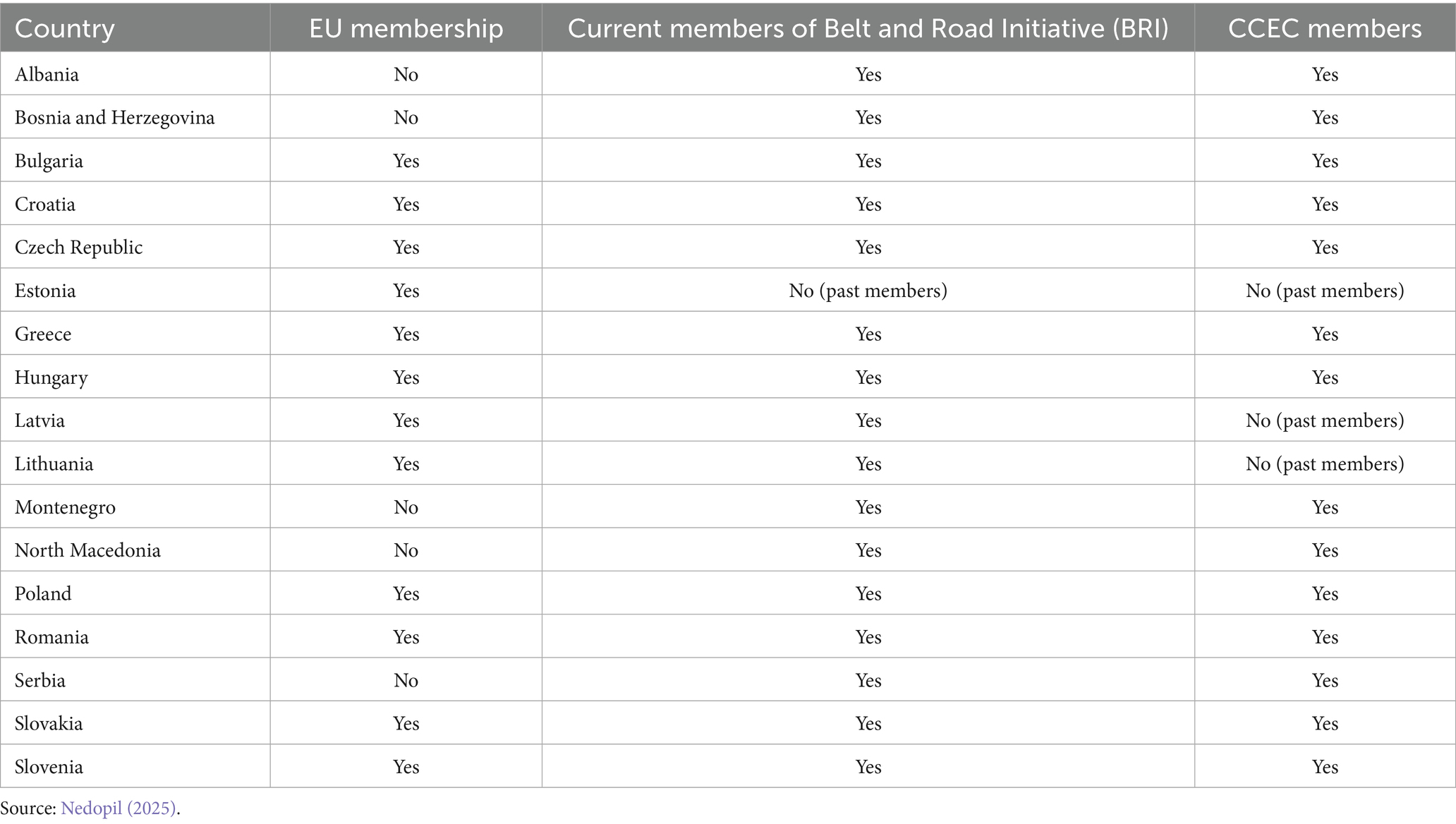

In the context of the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries (CECC) notes that Greece was officially invited to join the CECC following the Dubrovnik Summit in 2019, bringing the membership to its peak of 17 + 1. However, Lau (2022) outlines the withdrawal of Baltic states—Estonia and Latvia—from the CECC, following Lithuania’s earlier withdrawal in 2021. This reduced the framework to 14 + 1, excluding the Baltic states. Table 2 provides a detailed overview of CECC membership, indicating whether countries are EU members and their participation in the BRI.

In comparison to the European Union, “pan-European” countries participate in the “14 + 1” framework, which serves as a centralized platform for cooperation between China and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). As shown in Table 3, 11 of the CEE countries are EU member states. Notably, all 17 countries listed in Table 2 have signed Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), demonstrating strong alignment between their participation in the BRI and their membership in the CECC framework. However, Estonia withdrew from the BRI in 2022. Additionally, the three Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—have also chosen to withdraw from the CECC framework, despite being EU members.

Table 3. EU member states’ participation in the BRI project & the China-Central & Eastern European Cooperation (CECC).

Lau (2022) attributes their withdrawal to China’s declaration of maintaining an “unlimited partnership” with Russia and its leader, Vladimir Putin. This stance has raised significant concerns among the Baltic states, particularly in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Baltic states view China’s continued alignment with Russia as a troubling development, further straining their willingness to engage in China-led initiatives.

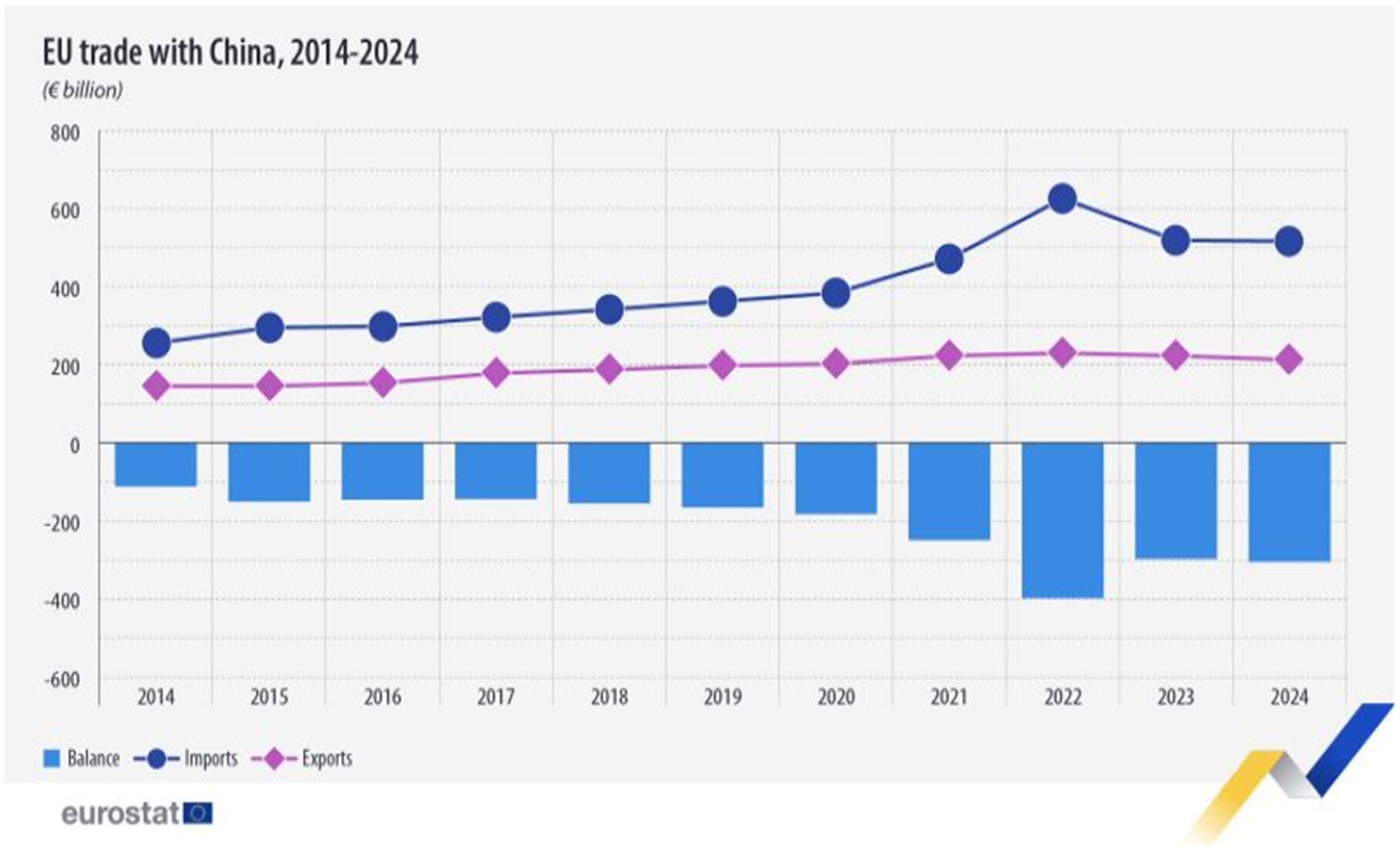

4.5 Examination of trade, cooperation & investment in the BRI era

The level of EU-China cooperation is a central focus of this paper, particularly in the context of the 3 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. In terms of trade, we have observed a gradual increase in EU imports from China between 2014 and 2024, with a notable surge during the pandemic years, especially from 2020 to 2021. This trend reflects heightened demand and actual imports of goods from China to the EU during the pandemic, culminating in a peak in 2022. In contrast, the level of EU exports to China has remained relatively constant over the same period, resulting in a clear trade imbalance, where EU imports from China consistently exceed EU exports to China.

Overall, the EU-China trade relationship has expanded during the BRI era (post-2013), particularly as more EU countries have signed Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) to join the Belt and Road Initiative (see Nedopil, 2025). Figure 1 illustrates the trajectory of EU-China trade between 2014 and 2024, highlighting the growing trade volume and the persistent imbalance between imports and exports.

Figure 1. EU trade with China, 2014–2024. Source: Eurostat (2025).

According to the European Commission (2025), electrical products dominate trade between the EU and China, accounting for 52% of imports from China to the EU and 34.1% of exports from the EU to China. In contrast, the vehicle and aircraft industry represents 16.7% of EU exports to China but only 5.5% of imports from China to the EU (Euronews, 2025). These figures highlight the EU’s continued reliance on imports from China, particularly in the electrical products sector, underscoring the asymmetry in trade dynamics between the two regions.

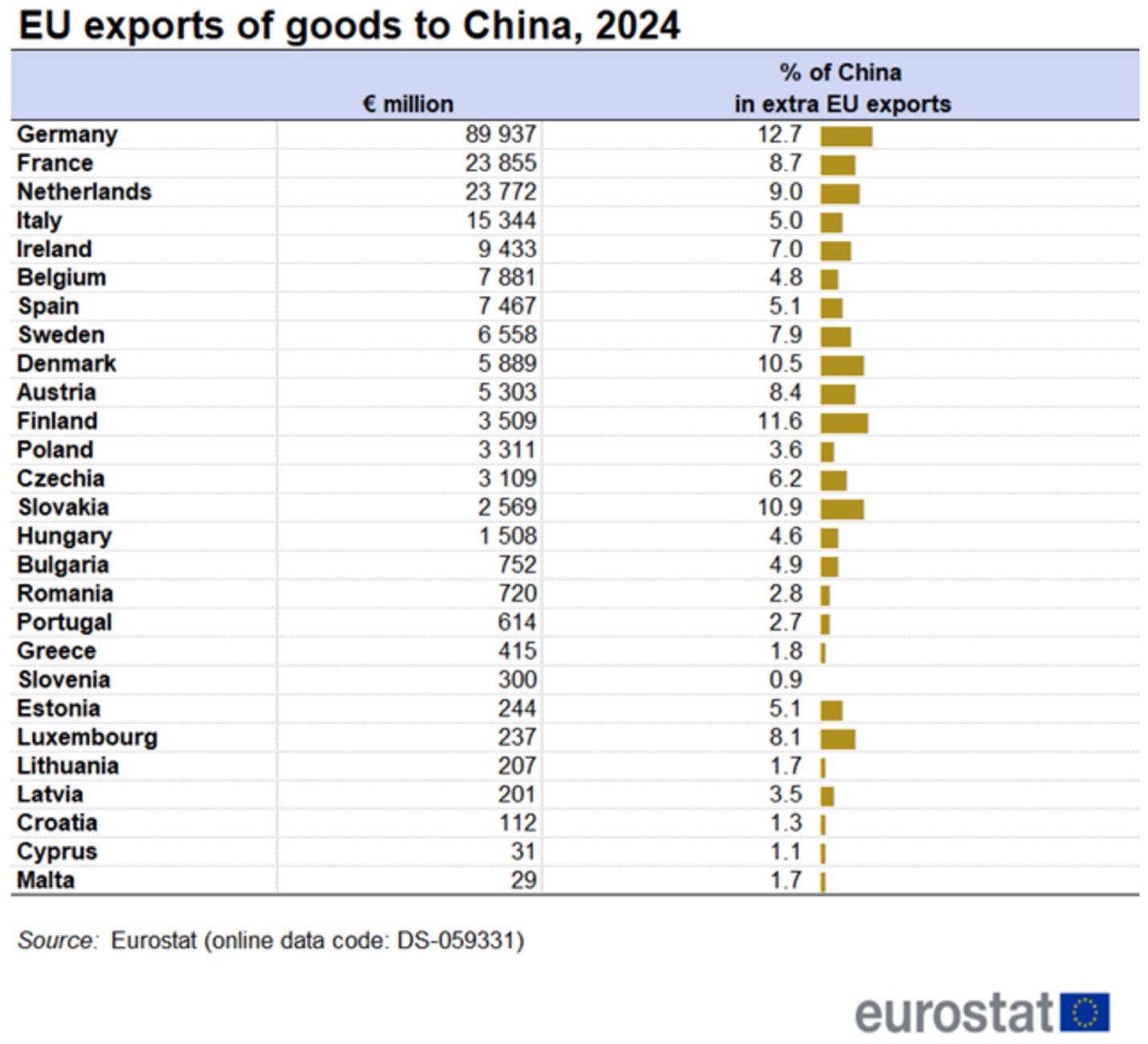

Our empirical analysis of trade relations between China and individual EU member states (state-level) reveals significant variations in the strength and scope of these partnerships. According to data from the European Commission (2025), Germany stands out as having particularly robust trade relations with China, both in terms of trade value and as a percentage of its extra-EU exports. Additionally, Denmark, Finland, and Slovakia are among China’s key export destinations within the EU, with over 10% of China’s exports directed to these countries.

Despite their strong trade ties with China, Denmark, Finland, and Germany have not joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project. This highlights a divergence between trade engagement and formal participation in China’s flagship initiative. Figure 2 illustrates the significance of China as an export market for various EU countries, emphasizing its critical role in their external trade dynamics.

Figure 2. EU exports of goods to China, 2024. Source: Eurostat (2025).

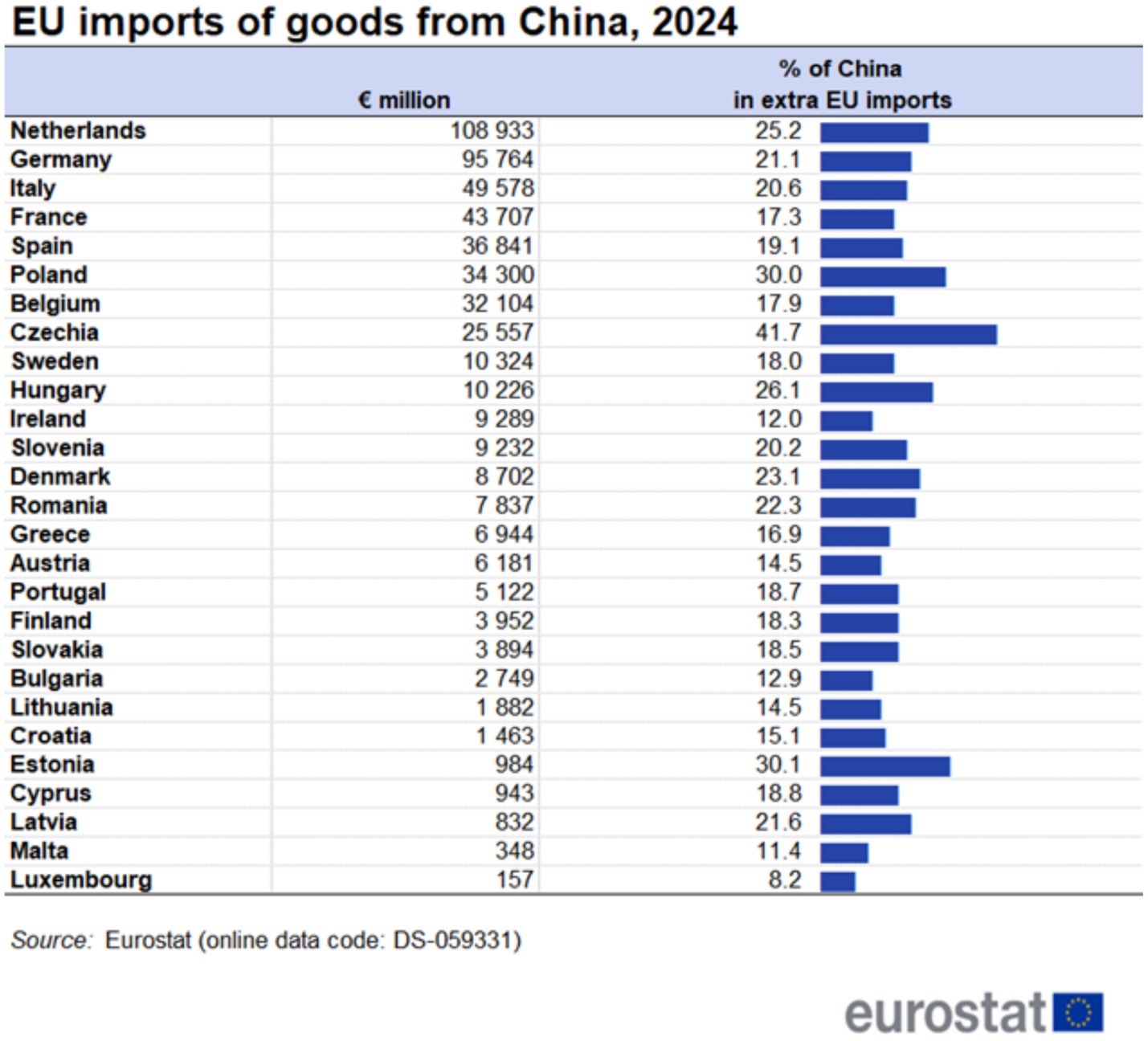

Figure 3 illustrates the level of imports from China across EU member states. According to the European Commission (2025), Germany and the Netherlands have the highest levels of goods imported from China compared to other EU countries. Interestingly, neither Germany nor the Netherlands are formal members of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In terms of China’s share in imports, the Czech Republic stands out, with 41.7% of its imported goods originating from China. Notably, the Czech Republic is both a member of the BRI and the China-Central and Eastern European Cooperation (CECC) framework (14 + 1).

Figure 3. EU imports of goods to China, 2024. Source: Eurostat (2025).

This data suggests that there is no clear correlation between trade volume and BRI membership, as non-BRI members can exhibit higher trade levels with China than some BRI members. To further explore the complex dynamics of EU-China relations, this paper will focus on three key areas: (a) the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; (b) infrastructure projects related to the BRI in Europe; and (c) new connectivity initiatives under the BRI framework, such as the China-Europe Railway Express (cargo).

4.5.1 Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on EU-China relations

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected human life and the global economy overall. As shown in Figure 1, trade levels between the EU and China increased from 2020 to 2022, indicating that the pandemic did not significantly disrupt trade volumes. However, Kowalski (2021) highlights China’s “crisis diplomacy” during the early stages of the pandemic, when it provided masks and other medical aid to European countries. This “mask diplomacy” was part of China’s effort to bolster its image as a global leader under Xi Jinping’s leadership, while simultaneously deflecting criticism of its domestic handling of the pandemic in late 2019 and 2020.

Kowalski (2021) also found varying perceptions of China’s aid effectiveness across Europe. For example, Czech citizens expressed a belief that China was more effective than the EU in helping them combat the pandemic. In Serbia, this sentiment was even stronger, with 39.3% of citizens favoring China’s aid compared to only 17.6% favoring the EU, despite the EU contributing significantly more assistance. This suggests a unique relationship between China and Serbia, which is deeply engaged in the BRI framework. China’s influence in Serbia appears to extend beyond economic cooperation, shaping public perceptions and fostering stronger bilateral ties. However, cross-border tourism between China and Europe remained slow until the Chinese government lifted strict lockdown measures in the second half of 2022.

4.5.2 Infrastructure & connectivity under the BRI framework

The Belt and Road Initiative has significant implications for economic connectivity, with the “Belt” symbolizing the Silk Road linking China and Europe. The subsection on “Infrastructure & Connectivity Under the BRI Framework” (p. 15) would benefit from more examples beyond the China-Europe Railway Express. Notable BRI projects in Europe include:

(1) Piraeus Port (Greece): COSCO’s investment transformed Piraeus into a major entry point for Chinese goods into Europe, boosting Greek logistics and creating jobs (Wong and Downes, 2024).

(2) Budapest-Belgrade Railway (Hungary-Serbia): A flagship BRI project improving regional connectivity and trade, co-financed by Chinese banks and constructed by Chinese firms (Wong and Downes, 2024).

(3) Pelješac Bridge (Croatia): Built by a Chinese consortium, this bridge connects southern Croatia and enhances regional transport infrastructure (Jones, 2021).

(4) Highway Projects (Montenegro, Serbia): Chinese-financed highways, such as the Bar-Boljare motorway in Montenegro, have improved regional connectivity, though they also raise concerns about debt sustainability (Bhuiyan and Beraha, 2022).

(5) Energy Projects: Investments in power plants and renewable energy infrastructure in countries like Romania and Serbia (Wong and Downes, 2024).

These projects illustrate the range and scale of BRI-driven connectivity and their role in deepening China-Europe economic ties (Wong and Downes, 2024). The China-Europe Railway Express, a freight train network that facilitates trade between the two regions. Yang et al. (2020) analyzed the railway network connecting Chongqing (China) to Europe, highlighting its role in improving trade transport accessibility and increasing total cargo volumes, particularly for key industries such as food and materials. Additionally, the railway network offers environmental benefits, such as reduced emissions compared to traditional shipping methods (see BBC, 2017).

Su et al. (2024) further examined the impact of the China-Europe Railway Express on enhancing “agricultural value chains” under the BRI framework. Their findings provide strong evidence that the railway network fosters mutually beneficial linkages between China and Europe, enabling European countries to gain new advantages in their trade relations with China. This demonstrates how the BRI’s infrastructure projects can create opportunities for deeper economic integration and collaboration across industries.

For example, the China Railway Express, which operates under the BRI, is playing an important role in freight transport at a lower cost, and it could potentially attract 5% of the total cargo transported (see Jiang et al., 2018). Furthermore, the China Railway Express could provide additional benefits to specific industries and products, such as electric vehicles and lithium batteries (Lin et al., 2025). Therefore, China Railway Express is a measure of reciprocity in connecting China and European countries, fostering trade development for all participants. Furthermore, China Railway Express connects important ports such as Shanghai (China), Hamburg (Germany) and Rotterdam (the Netherlands), providing greater synergy with the maritime sector.

The Maritime Silk Road is another key element of the BRI, through which China aims to develop a maritime network for cargo transportation (shipping with containers). Therefore, China’s goal is to establish routes to different regions with the support of ports and other facilities. We examined two notable BRI port projects in European countries. Since 2016, a state-owned enterprise, China Ocean Shipping Company, has controlled the Port of Piraeus in Greece. According to Koenig et al. (2024), COSCO’s use of the Port of Piraeus as their Mediterranean loading centre has not resulted in a significant decrease in business for other ports (there is no sole loser). Moreover, COSCO’s ships can use the Port of Piraeus as a hub and use smaller ships for travel to Western Europe rather than arriving there directly (higher efficiency).

A further noteworthy consequence of BRI on the railway project is the manner in which China exports technology and invests in high-speed railways. For instance, the Indonesian high-speed railway between Jakarta and Bandung demonstrates China’s involvement in new infrastructure projects in developing countries, as well as those of its partners. China was successful in obtaining construction proposals (bidding against Japan) (see The Japan Times, 2015; Wu and Chong, 2018). The present study returns to the subject of Europe.

The high-speed railway project between Belgrade and Budapest, which connects the two capitals (Hungary and Serbia), has demonstrated its impact on infrastructure development and the establishment of connections (see Bickerton, 2024). Railways offer more convenient, cheaper and faster ways to conduct trade and business operations. Moreover, the project involves the BRI acting as a platform that (1) provides techniques, finance and support, and (2) establishes cross-country infrastructure and transportation. This means that the BRI project can fulfil its goal of building a belt to link countries with China’s participation.

The Belt and Road Initiative also provides greater potential to China’s engagement on the infrastructure projects in the BRI’s member states domestically. For instance, China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) involved in the project of the Pelješac Bridge in Croatia that China’s company provided a cost effective method in looking for financial returns (Baričević et al., 2022). Therefore, BRI demonstrates strong economic potential through projects and investments (or loan provision) by the Chinese government or Chinese enterprises (including state-owned enterprises). Turcsanyi and Kachlikova (2020) describe how the BRI has successfully created a positive image in the media due to economic opportunities based on the economic reciprocity overall.

4.6 Case study analysis

The complexity of EU-China relations is explored through four case studies that include Germany, Hungary, Italy, and Serbia. These four case studies offer insights into specific target countries surrounding EU-China relations. Four countries have been selected as key examples to analyze the diversity (diverse stances) among EU member states and their collective approach towards dealing with China. Moreover, the case studies shed light on the evolving post-COVID-19 global landscape alongside China’s rising global engagement since the 2010s.

The German case study delves into economic competition, cooperation, and strategic trade-offs influenced by its important EU leadership role. Hungary’s case focuses on recent economic collaborations with China and Hungary’s distinctive stance under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán towards China. The Italian case study provides a more complex view, particularly considering Italy’s shifting position towards China, following recent personnel changes in government, from 2022 onwards. Lastly, the Serbian case study, as the sole non-EU member state case, demonstrates how non-EU accession countries maintain a strong economic cooperation with China, notably within frameworks such as the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC 14 + 1).

4.6.1 Case I: Germany: navigating “dual competition” in economic & security domains

4.6.1.1 Background—government transitions in Germany

From 2005 to 2021, Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of Germany, held a prominent leadership role in both Germany and the European Union. Merkel’s long tenure as Chancellor of Germany witnessed significant challenges, including the global economic crisis and the subsequent European debt crisis. Notably, Merkel’s adoption of a “Pro-humanitarian” asylum policy during the European refugee crisis reshaped German society and led to a surge in asylum applications (The Guardian, 2020). Following Merkel, the new Chancellor, Olaf Scholz (2021–2025), has faced considerable questions about Germany’s wider role in both the EU and NATO as Europe’s largest economy. Therefore, Germany is a significant country within the European Union. At the same time, the 2021 German federal election ended the governance of Union parties (CDU) and was replaced by the Social Democratic Party—a socialist party in moderation. It will bring new implications to German policy alongside the discussion on the legacy of Merkel (The Economist, 2024).

4.6.1.2 Economic relations—“risk averse rhetoric” & economic consideration of Germany

The “de-risking” strategy, introduced by the EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in 2023 underscores Germany’s approach towards China as a strategic challenge to its global interests. German authorities have implemented a comprehensive strategy to mitigate China’s influence across various sectors, including technology and trade, in aiming to reduce dependencies on Chinese investments and technologies.

Despite concerns, Germany has been cautious in taking aggressive economic measures against China, often prioritizing its economic interests. For instance, Germany recently opposed the EU Commission’s proposal to levy higher tariffs on Chinese battery electric vehicles, aligning with its commitment to free trade and economic considerations. While Germany remains vigilant against China’s rising influence, it also seeks to balance economic interests with strategic objectives.

4.6.1.3 Key challenges—navigating strategic rivalry & tensions

From a German perspective, the realization that their flagship industry—car manufacturing—heavily relies on China is widely acknowledged within the German business community. This understanding led Germany to adopt a balanced stance among its EU counterparts, prioritizing its economic interests. Consequently, Germany has devised robust strategies to mitigate China’s influence and ascendancy (see Poggetti, 2018; Fischer and Neudecker, 2024). Concurrently, German policymakers are deliberating on maintaining this equilibrium.

Furthermore, Bartsch and Wessling (2024) noted the German government’s comprehensive strategy to reduce China’s influence in several areas, including technology, trade, and fundamental factors (e.g., 5G networks and the Hamburg port, where China and Chinese investments are involved, are seen as risks). In other words, Germany expects Germans and their companies to consider how to reduce the impact of China and end the current dependence on China.

4.6.1.4 Political dynamics & future outlook—Germany & EU-China relations

Nonetheless, Germany remains reluctant to take negative economic and trade measures against China. For example, the EU Commission’s agenda is to impose higher tariffs (45%) on Chinese battery electric vehicles (BEVs) (see The New York Times, 2024). Germany voted to oppose it even though it was also passed by the EU Commission which includes strong support from France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Poland (see BBC, 2024a, 2024b).

In conclusion, Germany’s stance on engaging with China reflects a nuanced approach that considers economic interests alongside broader strategic concerns. Overall, Germany is not an active actor in attracting Chinese cooperation. For example, Germany’s BRI participation can be attributed to the proactive attitude of Merkel’s Government, especially towards Chinese investment. While Germany aligns with EU partners such as France and NATO allies in addressing human rights issues and strategic rivalries with China, Germany’s policies are influenced by its economic interdependence with China. The German government continues to navigate these complex dynamics to safeguard its interests while responding to evolving global challenges.

4.6.2 Case II: Hungary: a distinctive & diverse policy choice in EU-China relations

4.6.2.1 Background—Viktor Orbán & the changing political landscape

Hungary’s diplomatic trajectory since the fall of the Hungarian communist regime in 1989 has been marked by a transition towards democracy, characterized by the adoption of democratic institutions and free elections. Noteworthy milestones include Hungary’s successful negotiations for EU accession starting in 1998 and its subsequent entry into the EU in 2004, showcasing a relatively successful transition to political reform and a market economy compared to other Central and Eastern European nations with similar historical backgrounds (Vaida, 2018).

However, the governance of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who came into power in 2010 and has led the country with his party Fidesz, has faced criticism for its impact on Hungary’s democratic institutions. Furthermore, Orbán’s government has acquired ‘super-majorities’ in the Hungarian National Assembly in consecutive national parliamentary elections since 2010, consolidating power and influencing media narratives to a significant extent (Scheppele, 2022).

4.6.2.2 Economic relations—strategic engagement with China via the BRI

Hungary has also been cultivating closer ties with China, particularly in global trade, exemplified by its involvement in global value chains and participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (see Timmer et al., 2014; Gáspár et al., 2023). This shift towards China comes after Hungary’s rejection of IMF involvement during the global financial crisis, signaling an effort to enhance economic opportunities with China and engage more actively in the China-Central and Eastern European Countries Cooperation (CEEC) framework (Song, 2018; Song and Li, 2024).

Hungary’s participation in the BRI and collaboration with Chinese-led initiatives indicates a willingness to deepen economic cooperation with China. Chinese investments in Hungary, such as the high-speed railway project between Belgrade and Budapest, offer expanded economic prospects (see Bickerton, 2024). However, the previous study shows that the direct impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on Hungary’s domestic politics is limited. Wong and Downes (2024) clarify that the BRI has not exported authoritarianism and there is no explicit evidence of worsening corruption levels. While the direct impact of China’s BRI on Hungary’s domestic politics appears limited, Hungary’s alignment with China has implications for its relations with the EU and other Western allies.

4.6.2.3 Key challenges—the tendency towards de-Europeanization & democratic backsilding

Orbán’s leadership has been associated with a right-wing populist brand. Following Fidesz’s dominant electoral victories, rapid amendments to the Hungarian constitution, electoral law, and constitutional court were made without public consultation, further cementing Orbán’s and Fidesz’s grip on power (Rydliński, 2018). Moreover, the media landscape in Hungary has also undergone significant changes, with institutions such as the Council of National Media exerting control over national media outlets, allowing Fidesz loyalists to influence narratives (see Wong and Downes, 2024; Sadecki, 2014; Rydliński, 2018; Spence, 2016).

Ágh’s analysis underscores trends of de-Europeanization and de-democratization under Orbán’s governance, with Hungary veering towards electoral autocracy and straining its relations with the EU. These developments have raised concerns about Hungary’s commitment to liberal democracy and its alignment with core EU values, ultimately deepening the divide between Hungary and its European counterparts. For instance, Hungary has repeatedly blocked or diluted joint EU statements critical of China on issues such as human rights and Hong Kong (see von der Burchard and Barigazzi, 2021). This behavior fragments the EU’s approach to China, undermining efforts to present a unified stance and weakening the effectiveness of EU leverage in negotiations with Beijing. It enables China to exploit divisions within Europe, selectively engaging with states most open to its influence and bypassing EU-level oversight. Therefore, while Hungary moves away from EU democratic standards, they often seek alternative sources of political and economic support to reduce their dependence on Brussels.

4.6.2.4 Political dynamics & future outlook—Hungary & EU-China relations

Hungary’s increasingly amicable stance towards China contrasts with the EU’s more critical approach, particularly evident in disagreements over issues such as tariffs and human rights. Hungary’s divergence from EU stances, such as opposing higher taxes on Chinese electric vehicles, underscores a shift towards prioritizing economic ties with China over alignment with EU policies (The New York Times, 2024).

Furthermore, Hungary’s growing security cooperation with China, coupled with its distancing from EU and NATO allies, raises questions about its commitment to shared liberal democratic values and human rights standards (The Guardian, 2024). Criticism from EU partners, such as Germany, over Hungary’s reluctance to support EU actions against China’s human rights violations in Hong Kong, exemplifies the diplomatic challenges Hungary faces in balancing its relationships with both China and the EU (von der Burchard and Barigazzi, 2021).

Therefore, Hungary’s strategic engagement with China under Orbán’s leadership underscores a nuanced diplomatic balancing act between economic cooperation with China and relations with Western alliances. The country’s evolving stance reflects a deliberate choice to prioritize economic opportunities with China, potentially at the expense of closer ties with the EU and NATO. This shifting dynamic highlights the complexities of Hungary’s foreign policy decisions and their implications within the broader EU-China context.

4.6.3 Case III: Italy’s complex political landscape & shifting foreign policy dynamics

4.6.3.1 Background—Italy’s membership in the AIIB & the BRI project

Until recent years, Italy has maintained dual membership in both the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project led by China. This dual affiliation has facilitated enhanced economic collaboration with China and other participating countries, particularly in infrastructure development, trade, and economic partnerships. However, Italy’s involvement in these initiatives has stirred debates and deliberations regarding the potential economic, political, and strategic implications for the country and its international relations (see Wong and Downes, 2024).

The Italian political scene has witnessed significant fluctuations in foreign policy, largely influenced by governmental transitions. The replacement of the Euro-Atlanticist government (2014–2018) by the M5S-Lega Coalition Government in 2018 marked a pivotal shift. Under the Conte Government, efforts to attract Chinese capital aimed at bolstering financial markets was accompanied by an anti-EU stance and a push towards de-Europeanization to underscore nationalist identity (see Pugliese et al., 2022). Populist rhetoric, as elucidated by Müller et al. (2021), has played a substantial role in reshaping national narratives and agendas, contributing to the weakening of the EU framework and its domestic repercussions (see Monteleone, 2021). These policy shifts underscore a significant reorientation in foreign policy positions in Italy in recent years.

4.6.3.2 Economic relations—economic partnerships with China

Economic considerations have played a central role in Italy’s growing partnership with China, evidenced by various agreements and collaborations. Italy’s signing of the Memorandum of Understanding with China in 2019 further solidified this relationship, in recognizing China as both an economic competitor and as an economic co-operation partner. The BRI represents a complex and broad spectrum of mutual agreements and projects spanning multiple sectors, including the economy, infrastructure, and culture (Wong and Downes, 2024).

Concerns have been raised within Italy’s domestic economy regarding the progressive BRI project, particularly fears of China’s escalating influence (Coratella, 2019). The endorsement of the BRI and collaboration with China have sparked widespread political debates and public apprehension, elevating China to a critical national issue, overshadowing concerns such as immigration and the European Union’s policies and attitudes.

4.6.3.3 Key challenges—political landscape & government transitions

The ever-changing political landscape in Italy has seen a series of short-lived Coalition Governments between 2018 and 2023, reflecting the fragmented nature of the country’s politics. Oscillations between the radical left and right, alongside eclectic technocratic-populist ideologies, exemplify the complexities of Italian politics (see Bruno et al., 2024; Wong and Downes, 2024; Donà, 2022;). The collapse of the Draghi Coalition Government in 2022 paved the way for Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia party to assume power, leading to Italy’s withdrawal from the BRI under Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing government in late 2023 (Kazmin, 2023). Subsequently, Italy also demonstrated its position towards China and made decisions unfavourable to China at the EU level [e.g., battery electric vehicle (BEV) tariffs].

4.6.3.4 Political dynamics & future outlook—shifting stances towards China

Italy’s shifting stances towards China reflect the broader volatile and fragmented nature of its political landscape, influencing the country’s strategic foreign policy decisions (Bruno et al., 2024). The dynamic nature of Italian politics underscores the nuanced approach taken by different political parties in their strategies towards dealing with China. Recent years have seen Meloni’s Government shift away from its predecessor’s pro-China stance, opting for a more cautious approach in both political and economic engagements with China.

In summary, Italy’s evolving relationship with China underscores the intricate interplay between economic interests, political ideologies, and foreign policy considerations. The country’s strategic positioning between the West and East reflects the delicate balancing act it must maintain. The shifting dynamics in Italy’s approach to China highlight the intricate nature of international relations and the impact of domestic politics on foreign policy decisions.

4.6.4 Case IV: Strategic partnerships: China-Serbia economic relations

4.6.4.1 Background—geopolitical legacy & historical context

Strategically positioned in the Balkans, Serbia remains a pivotal actor in Central and Eastern Europe despite its landlocked geography and post-Yugoslav fragmentation. Historically, Socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1992) balanced Cold War tensions through Tito’s Non-Aligned Movement, avoiding Soviet dominance while engaging globally (Rajak, 2014).

During the Yugoslav conflicts of the 1990’s, China opposed NATO’s military intervention to depose Slobodan Milošević (Cohen, 2010). Tensions escalated in May 1999 when U.S. airstrikes accidentally bombed China’s Belgrade embassy, killing three Chinese nationals. This tragedy cemented Beijing’s diplomatic solidarity with Serbia, exemplified by its ongoing refusal to recognize Kosovo’s independence—a stance contrasting sharply with Western positions.

Therefore, the fourth and final case study will therefore briefly analyze: (1) Serbia’s geopolitical significance in China-Serbia bilateral relations since 2000s, (2) Key challenges on both domestic governance and crisis (COVID-19) and (3) post-COVID-19 Pandemic developments and future prospects.

4.6.4.2 Economic relations—bilateral ties, economic pragmatism & the future trajectory

Since 2009, China and Serbia have institutionalized cooperation via a “strategic partnership” with trade expanding steadily since 2000 (see Jovičić and Marjanović, 2024). Serbia now participates actively in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the China-CEE Cooperation framework (“17 + 1”). Despite EU candidacy, Serbia maintains strategic ambiguity—criticizing Russia’s Ukraine invasion while rejecting Western sanctions (Mayer, 2024)—a balancing act reflecting its economic reliance on China.

China is now Serbia’s second-largest trade partner, with post-2018 growth skewed by imports of Chinese machinery and infrastructure investments (Ivanovic and Zakic, 2023). This growth is evident in bilateral trade volume and a sharp rise in imports from China, which have widened the trade deficit (Jovičić et al., 2020; Ivanovic and Zakic, 2023; Jovičić and Marjanović, 2024). China and Serbia have intensified development-focused collaboration under multilateral frameworks, particularly through infrastructure upgrades (e.g., railway networks) and technology transfers, which now form pillars of their economic partnership.

4.6.4.3 Key challenges—liberal democratic erosion & the COVID-19 pandemic

Post-Milošević Serbia transitioned towards electoral democracy, yet Levitsky and Way’s (2010) “competitive authoritarianism” aptly describes Serbia’s current political regime. Under President Aleksandar Vučić (2017–present), media censorship, judicial politicization, and electoral irregularities have drawn repeated criticism at the EU level (see Castaldo, 2020; European Commission, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016). Like Hungary, Serbia’s liberal democratic retreat creates fertile ground for transactional Sino-Serbian ties that sidestep normative frameworks.

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified bilateral cooperation, with China providing Serbia vaccines and medical assistance—a cornerstone of its ‘Health Silk Road’ initiative to extend global health influence (Vuksanovic, 2022). Major large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Budapest-Belgrade railway upgrade have also highlighted Serbia’s role as a BRI gateway into Europe.

4.6.4.4 Political dynamics & future outlook—strategic horizons: the future of China-Serbia economic collaboration

Critically, Serbia’s non-EU status allows unrestricted economic engagement with China, contrasting Brussels’ regulatory oversight. While there is no empirical evidence to prove that China actively exports authoritarianism via the BRI project (Wong and Downes, 2024), Serbia’s governance flaws facilitate deal-centric cooperation. As EU accession stagnates, Belgrade has increasingly prioritized Chinese capital over democratic governance, thereby mirroring regional trends in the Western Balkans. The EU central authority examines the standard of democratic governance of European countries that want to become EU member states based on the Copenhagen criteria. This includes the rule of law, democracy, human rights and good governance (Janse, 2019). Therefore, the stagnation of EU accession implies that the above “condition” will be less prioritized, while Belgrade increasingly engages with Beijing (there is no evidence that Chinese capital and democratic governance are mutually exclusive).

Serbia exemplifies a possible alternative geopolitical pathway for non-EU European states. Under President Aleksandar Vučić, Belgrade has prioritized alignment with China, actively participating in reciprocal development initiatives—such as infrastructure projects and technology transfers—under Beijing’s Belt and Road (BRI) framework.

In recent years, Serbia has deepened its partnership with China while distancing itself from Western integration efforts. This shift underscores Belgrade’s strategic calculus: as a non-EU state, Serbia prioritizes alignment with Beijing over adherence to Brussels’ normative frameworks, pursuing closer Sino-Serbian ties without the constraints of EU membership.

4.7 EU-China relations: economic cooperation vs. strategic competition: China’s BRI Project & the EU’S global gateway project

A central tension in EU-China relations is the interplay between economic cooperation and strategic competition. The BRI Project has facilitated significant infrastructure investment and trade linkages between China and several European countries, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (Wong and Downes, 2024; Bhuiyan and Beraha, 2022). For many EU member states, participation in the BRI has offered access to new markets, capital, and development opportunities (Jones, 2021; Łasak and van der Linden, 2019).

However, as China’s influence in Europe has grown, so too have concerns about strategic dependencies, transparency, and the geopolitical implications of Chinese investment (Gurol, 2022; Telò, 2021). In response, the EU has launched its own connectivity strategy—the Global Gateway in December 2021 under EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen—which explicitly aims to provide an alternative to the BRI by promoting high standards of sustainability, transparency, and democratic values (Wong and Downes, 2024). This initiative reflects the EU’s desire to maintain strategic autonomy and reduce vulnerabilities in critical sectors such as digital infrastructure, energy, and transport (Politi, 2023).

However, this duality is further complicated by the EU’s internal divisions. While some member states, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, continue to welcome Chinese investment, others—primarily in Western Europe—have become more cautious, emphasizing the need for “de-risking” and greater scrutiny of foreign investments (Wong and Downes, 2024; Gurol, 2022). The Russia-Ukraine conflict and the broader context of US-China rivalry have only intensified these concerns, pushing the EU to balance economic interests with security and normative considerations (Ding and Ekman, 2024).

The European Union’s response to China is shaped by its supranational institutions, which both enable and limit collective action overall. The European Commission has emerged as the primary actor in advancing the EU’s “de-risking” agenda under current Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, in seeking to reduce strategic dependencies on China in critical sectors such as technology, infrastructure, and supply chains (Politi, 2023).

This proactive stance reflects the Commission’s mandate to defend the EU’s collective interests, often pushing member states towards greater coherence in external economic and security policy. Meanwhile, the European External Action Service (EEAS) created in 2011 plays an important role in formulating and coordinating a unified diplomatic approach to China, balancing divergent national positions and fostering dialogue among member states.

However, the EU’s multi-level governance system where authority is shared between supranational bodies and national governments—creates persistent tensions between collective ambition and national sovereignty. Intergovernmental dynamics, with member states retaining significant control over foreign and security policy, frequently lead to policy paralysis or diluted outcomes, especially when national interests diverge sharply.

This institutional challenge, rooted in the supranational nature of the EU, highlights the wider problem of achieving a truly unified China policy. While institutions such as the Commission and EEAS provide leadership and vision, the need for consensus among 27 member states often results in slow, incremental, or fragmented responses overall (see Downes, 2023). Therefore, the EU’s institutional framework contributes to the overall lack of a unified China policy.

5 Discussion

This paper has explored the evolving dynamics of EU-China relations within the framework of China’s initiatives, particularly the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the shifting global order, including the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The development and expansion of membership in the BRI and other China-led programs, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), underscore China’s growing influence and its ability to shape diplomatic relations through the density and diversity of participation. While the BRI’s development and EU-China relations exhibit nuanced dynamics across political, economic, trade, and cultural domains, this investigation has identified patterns and trajectories over the past decade, while also highlighting the diversity stemming from the heterogeneity of the European Union and Europe as a whole.

The analysis offers a thorough exploration of the political, economic, and international dimensions of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its implications for European countries. By examining the dynamic interplay between China’s strategic initiatives and the diverse responses of European nations, this paper illuminates the complexities of EU-China relations in an era of rapid geopolitical transformation. Notably, the study reveals that 17 EU member states have joined the BRI. However, two of the EU’s economic powerhouses—Germany and France—have opted not to participate. Furthermore, Italy, the only G7 country in Europe to have joined the BRI, officially withdrew from the initiative in 2021. This underscores the absence of overlapping membership between the BRI and the G7, highlighting a lack of significant economic power within the BRI framework.

In contrast, there is considerable overlap between the BRI and the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries (CECC), suggesting that China’s influence is more pronounced in Central and Eastern Europe (excluding the Baltic states). However, an analysis of BRI membership in relation to trade levels reveals that neither the share nor the percentage of trade appears to be strongly correlated with a country’s participation in the BRI (see Eurostat, 2025; Nedopil, 2025).

Circumstances leading to a weak correlation between BRI’s membership and trade levels. First, high trade volumes with China do not necessarily translate into BRI membership. For example, Germany and the Netherlands are among China’s top EU trading partners but have not joined the BRI, reflecting their preference for established EU frameworks and skepticism about China’s strategic intentions (see Wong and Downes, 2024; Telò, 2021). Second, BRI MoUs are often symbolic, with varying degrees of actual project implementation. Some countries join for diplomatic signaling or to attract investment, regardless of existing trade volumes (Wong and Downes, 2024). Moreover, EU member states face supranational oversight (with the complex web of multi-level governance) from EU institutions on investment, competition, and procurement, limiting the scope for bilateral deals with China outside EU policy (Telò, 2021).

This finding raises critical questions about the economic motivations and strategic considerations shaping European countries’ engagement—or lack thereof—with the BRI. The COVID-19 pandemic has further complicated these dynamics, sparking extensive discussions around the differing approaches adopted by European countries and China to address the crisis, particularly in areas such as vaccine distribution and medical assistance. Despite these challenges, the level of EU imports from China increased during the pandemic, particularly in the period from 2021 to 2022. This trend indicates that trade relations—specifically EU imports from China—have remained stable and even grown over the past decade (since 2014), with a significant surge during the pandemic (see Eurostat, 2025). These developments highlight the resilience of EU-China trade ties, even amidst broader geopolitical and economic uncertainties.

Our research on Germany and Italy reveals that both countries exhibit a limited level of cooperation with China, particularly in their stance towards the BRI and its associated projects. Despite their shared cautious attitude towards China, Germany and Italy approach the issue from distinct perspectives shaped by their unique political, economic, and strategic contexts.

Germany’s position is heavily influenced by its “de-risking” strategy, which reflects a “risk-averse” approach to China’s growing influence and power. This strategy involves a careful assessment of risks across various domains, including economic, technological, and geopolitical considerations (see Bartsch and Wessling, 2024). However, Germany’s approach is inherently broader and more complex, as it must account for a wide range of factors. These include economic interests and competition, diplomatic relations—not only with China but also with key partners such as the EU, the United States, and Russia—core values like human rights, and the dynamics of domestic politics. Germany’s multifaceted considerations underscore the intricate balancing act required to navigate its relationship with China while safeguarding its broader strategic interests.

Italy, on the other hand, demonstrates a different trajectory shaped by domestic political shifts. Changes in government have led to a reevaluation of diplomatic priorities, with the new Italian administration placing less emphasis on potential economic benefits from cooperation with China. This shift highlights the central role of domestic politics in shaping Italy’s foreign policy decisions. The Italian case underscores the importance of political factors—both domestic and global—in determining the outcomes of international cooperation. Together, these examples illustrate how the interplay of domestic politics, economic interests, and broader geopolitical considerations shapes the varying approaches of European countries towards China and the BRI.

In our case studies of Hungary and Serbia, we analyzed recent political developments to better understand the nature of their regimes and the applicability of the term “flawed democracy” to their governance (see Castaldo, 2020; Scheppele, 2022). Both countries demonstrate rapidly growing ties and cooperation with China, reflecting a notable divergence from traditional Western alliances.

Hungary, despite being an EU member state, has adopted a distinct approach that often diverges from its EU partners. This stance has drawn criticism, particularly regarding its democratic quality and its inability to align with broader EU consensus on key issues. Hungary’s increasing engagement with China highlights its willingness to pursue independent diplomatic and economic strategies, even at the expense of cohesion within the EU.

Serbia, meanwhile, has cultivated harmonious relations with China under the framework of a “strategic partnership.” This partnership is marked by Serbia’s growing dependence on China, particularly through its involvement in the BRI. Serbia’s alignment with China underscores its strategic pivot towards deeper cooperation with Beijing, further distancing itself from traditional Western alliances.

These case studies highlight a broader trend among certain Central and Eastern European countries, which appear increasingly inclined to embrace China-led initiatives. This shift reflects a diplomatic strategy that prioritizes closer ties with China while creating greater distance from traditional Western partners, including the EU and the United States. Furthermore, this trend underscores the evolving geopolitical dynamics, particularly the intensifying U.S.-China competition and China’s ability to foster alienation from Western frameworks (see Zhao, 2024). Hungary and Serbia’s approaches exemplify the growing diversity in diplomatic policies within the region and the rising appeal of China’s influence in reshaping global alliances.

The analysis also underscores the diversity of European countries’ attitudes towards China, shaped by their varying considerations across political, economic, and strategic interests. While escalating tensions in EU-China relations may not be evident, there is a clear lack of common consensus and coordinated action among EU member states. Each European country adopts its own approach to relations with China, reflecting differing priorities and perspectives. The BRI project serves as a case in point: while some countries share a strong belief in fostering cooperation with China through the initiative, others remain skeptical, questioning its merits and even adopting negative or hostile attitudes towards China, often framed through risk rhetoric.