- 1Undergraduate Program in Government Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

- 2Master of Public Policy & Management, Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3Program Sarjana Ilmu Pemerintahan, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Universitas Pancasakti Tegal, Tegal, Indonesia

Introduction: This study investigates the complex decision-making processes of voters in Indonesia’s 2024 general election, focusing on Bandung Regency. As a cornerstone of democracy, electoral outcomes are shaped by behaviors extending beyond simple rational choice. This research aims to map these behaviors to understand the quality of democratic engagement within Indonesia’s evolving political landscape.

Methods: The study employed a qualitative methodology guided by Behavioral Decision Theory (BDT). Data were collected through verbal protocol interviews, where sampled participants articulated their thoughts, emotions, and actions during their decision-making process. The transcribed verbal data were then analyzed using thematic analysis to identify patterns and classify decision-making typologies.

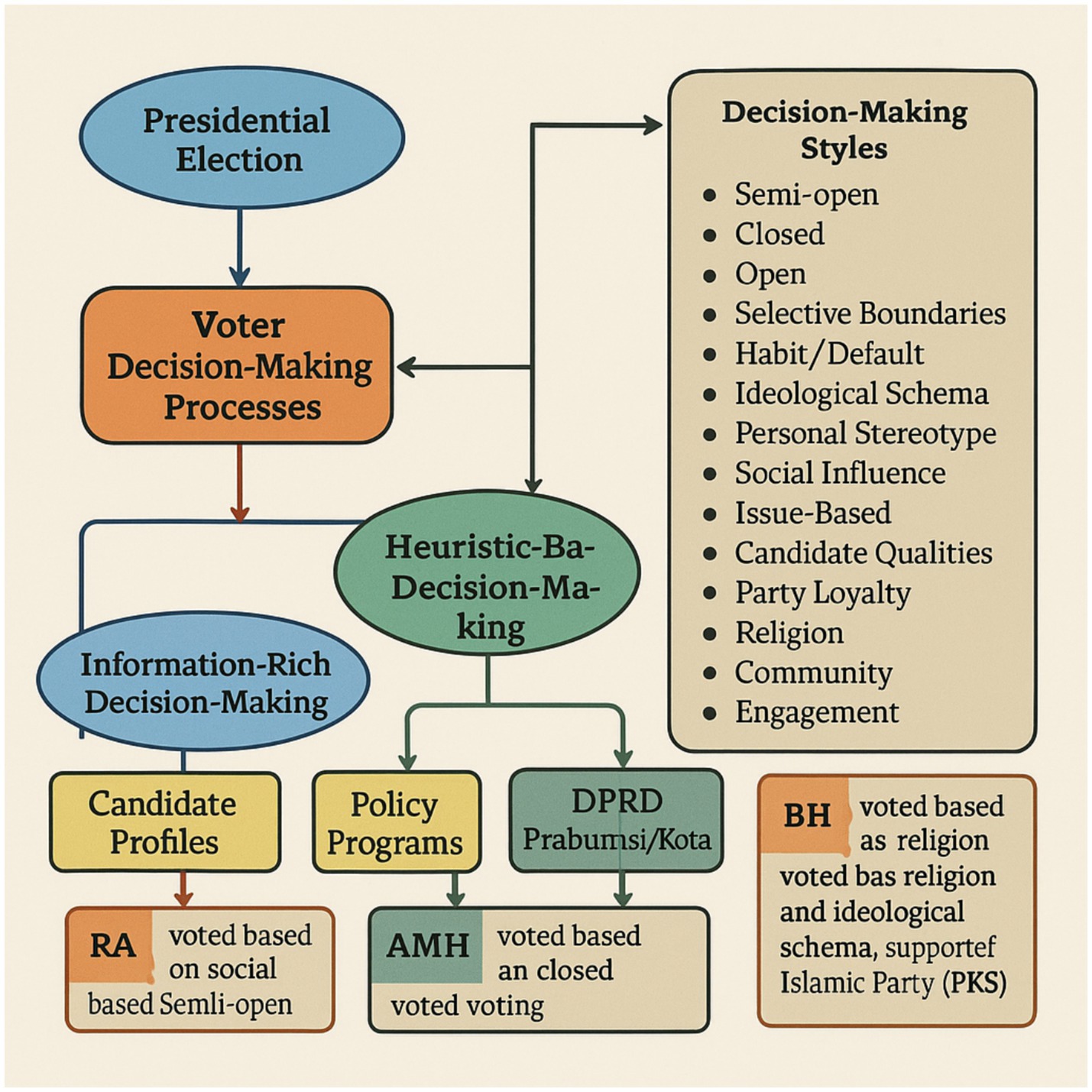

Result: The analysis revealed five distinct models of voter decision-making, Closed: Automatic, heuristic-based choices relying on social norms, family loyalty, or habitual party affiliation. Semi-open: A selective process where voters use filters like religious affiliation (e.g., Nahdlatul Ulama) or political party ties to limit and evaluate candidates. Open: Deliberative and comprehensive evaluation of candidate profiles, leadership qualities, and policy programs. Mixed: Voters employ different strategies (closed, semi-open, open) for different electoral levels (e.g., presidential vs. legislative) based on perceived importance and cognitive load. Coattail-driven: Voting for legislative candidates based on support for a specific presidential candidate, though this effect was not always consistent.

Discussion: The findings demonstrate that voter rationality is dynamic and context-dependent, heavily influenced by technology (e.g., digital media algorithms), socio-cultural identity, emotional trust, and political heuristics. The prevalence of closed and semi-open processes highlights vulnerabilities to disinformation and identity politics. Enhancing the quality of Indonesian democracy requires targeted political education, electoral reforms addressing informational asymmetries, and a deeper understanding of these multifaceted decision-making processes.

1 Introduction

Elections are widely regarded as a cornerstone of democratic systems, serving as the procedural embodiment of citizens’ political rights (Dahl, 2008). In liberal democracies, their role extends beyond the selection of leaders to the translation of public preferences into policy outcomes (Belt, 2007; Suyatno, 2016). Elections also enable the peaceful transfer of power, institutionalize political competition, and legitimize authority, thereby reinforcing the stability of democratic institutions (Ferdian et al., 2019). Yet their ability to produce effective leadership and align political outcomes with societal expectations remains contested, particularly in contexts marked by patronage networks, dynastic politics, and limited voter engagement (Younus et al., 2025).

In Indonesia, the democratic system is formally grounded in liberal principles, yet its practice often falls short of normative expectations. Local elections (pilkada) highlight this paradox, where democratic procedures coexist with oligarchic and clientelistic dynamics. These conditions underscore the critical role of voters in determining electoral outcomes and, by extension, the direction of public policy (Guntermann and Lachat, 2023). Nevertheless, empirical studies indicate that voter participation is not always rational or substantive. Many citizens cast their ballots based on social identity, partisan loyalty, or limited access to information, rather than on systematic evaluation of policy alternatives (Becker, 2023).

Assessing democratic quality requires a clear understanding of how voters make decisions. Previous research has classified voting behavior into several perspectives, most prominently sociological, psychological, and rational-choice approaches (Lilleker et al., 2024; Zwicker, 2016). The sociological perspective highlights the influence of social factors such as religion, gender, education, and occupation. The psychological perspective emphasizes voters’ identification with parties or candidates, while the rational-choice approach focuses on cost–benefit calculations aimed at maximizing individual utility.

Beyond these traditional perspectives, increasing attention has been directed toward the decision-making process itself, which examines how voters acquire, interpret, and apply political information (Belt, 2007). Redlawsk’s typology identifies a spectrum of decision-making styles—rational, confirmatory, intuitive, and heuristic—demonstrating that voter behavior is shaped by both cognitive mechanisms and contextual conditions (Lau and Redlawsk, 2001). His model encompasses approaches such as rational calculation, early socialization, heuristic shortcuts, and bounded rationality. These frameworks underscore the importance of analyzing not only electoral outcomes but also the internal cognitive processes that precede a voter’s choice.

Building on these perspectives, Dede Sri Kartini et al. (2010) developed a context-specific model of voter decision-making in Indonesia. The model distinguishes three categories: closed, semi-open, and open decision-making. Closed decision-making involves minimal information processing and reliance on party loyalty or external influence. Semi-open decision-making entails selective consideration of political programs, typically filtered through partisan lenses. Open decision-making reflects active engagement, with voters seeking extensive information in line with the ideals of deliberative democracy. Differentiating among these categories is essential for capturing the diversity of democratic engagement across individuals and electoral settings.

This study builds on and extends Kartini’s model to analyze voter decision-making in Indonesia’s 2024 general election. The election was held concurrently for the presidency, vice presidency, and legislative bodies (DPR, provincial DPRD, and district/city DPRD), creating a rich context for investigation. This setting provides a unique opportunity to assess whether voters apply consistent decision-making strategies across different levels of contest or adapt their approaches depending on the perceived significance and clarity of available options (Bigby, 2022).

The 2024 election also offers an important opportunity to examine the coattail effect—a phenomenon in which voters who support a presidential candidate are more likely to back legislative candidates from the same party or coalition. This dynamic was particularly visible in the case of the Prabowo–Gibran ticket, supported by a coalition including Gerindra, Golkar, PAN, PSI, and other parties. Although the ticket secured the presidency with 58.58 percent of the vote (Sanur et al., 2024), this advantage did not uniformly translate into legislative dominance. For instance, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP) obtained the largest share of legislative votes with 16.72 percent.

This study analyzes the cognitive stages through which voters progress, namely the absorption of information, the evaluation of political alternatives, and the act of final choice. Drawing on Dunn and Kingdon’s frameworks of decision-making in public policy (Cristofaro et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2024), it conceptualizes voting as a multi-stage deliberative process that reveals voters’ underlying motivations and varying levels of political engagement.

In this model, automaticity characterizes closed decision-making. Voters process minimal information, rely on familiar cues such as party symbols or community leaders, and make choices with limited reflection. By contrast, open decision-making reflects higher cognitive engagement: voters systematically consider multiple options, weigh candidate programs and leadership qualities, and deliberate before reaching a decision. Semi-open processes occupy an intermediate position, with voters actively seeking information but restricting their attention to candidates from particular parties. These categories represent varying levels of political knowledge and engagement.

This typology is not only theoretical but also has significant implications for understanding democratic quality. Open voters are more likely to demand accountability, support effective policy, and enhance the legitimacy of democratic institutions. Conversely, closed and semi-open decision-making can reinforce elite dominance, sustain clientelistic networks, or empower candidates whose platforms are poorly aligned with public interests. Mapping the prevalence and variation of these processes provides insight into both the resilience and the vulnerabilities of Indonesia’s democracy.

The research employs a qualitative case study design focusing on Bandung Regency. It juxtaposes Kartini’s earlier findings from 2010 and 2015 with current data, thereby capturing both voter classification and the evolution of the electoral landscape. Particular attention is given to how campaign dynamics and the growing accessibility of digital media—especially through social platforms—shape voter decision-making.

This study makes four contributions to ongoing debates. First, it advances conceptual understanding of voter behavior by integrating decision-making models with contextual insights from an emerging democracy. Second, it provides empirical evidence for theories of political cognition and democratic engagement. Third, it highlights the implications of voter decision-making styles for political education, electoral reform, and democratic consolidation in Indonesia. Finally, it situates Indonesia’s experience within broader discussions of democratic resilience in transitional contexts.

The central research question guiding this analysis is: How are closed, semi-open, and open decision-making processes manifested in the 2024 Indonesian general election, and how do they vary across different electoral levels? By addressing this question, the study seeks to provide a diagnostic perspective on voter behavior, electoral participation, and democratic quality, with broader ramifications for political development and policy responsiveness in Indonesia’s evolving democratic context.

2 Methodology

2.1 Research design and approach

This study employs a qualitative methodology, in contrast to the predominantly quantitative approaches commonly used in voting behavior research. While prior studies often emphasize statistical correlations between demographic variables and political choices, the present research focuses on the cognitive, emotional, and social processes that shape individual voting decisions. Qualitative inquiry is particularly well suited to examining subjective experiences and complex psychological dynamics that cannot be readily captured through variable-based surveys or experimental designs (Berg and Ternullo, 2025).

Although voting behavior is frequently conceptualized as a rational and linear process, recent scholarship highlights its dynamic, affective, and context-dependent dimensions. Accordingly, this study adopts a reconstructive and interpretive framework to analyze how voters absorb political information, form preferences, and ultimately reach decisions in Indonesia’s 2024 general election. The emphasis extends beyond identifying electoral outcomes to exploring the reasoning and processes through which those outcomes are produced.

2.2 Method of data collection: verbal protocol

This study employs the verbal protocol method, originally developed by Cox et al. (2025) to investigate information processing in voter decision-making. Within the framework of Behavioral Decision Theory (BDT), verbal protocols allow respondents to articulate their thoughts, emotions, and actions as they reflect on their candidate selection processes for the presidential, legislative, and Regional Representative Council (DPD) elections.

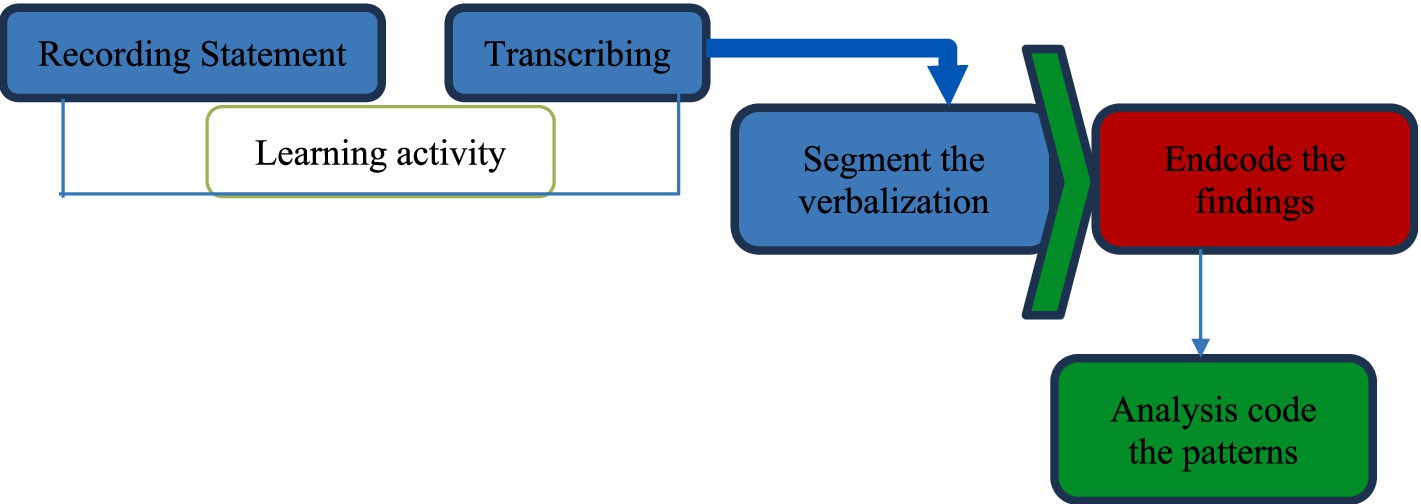

Participants were asked to describe in detail how their decisions evolved, beginning with their initial exposure to political information and extending to the act of voting. Particular attention was given to external influences such as peer pressure, religious or community endorsements as well as internal conflicts and instances in which voters’ final decisions diverged from their initial preferences or beliefs. These verbal reconstructions provide in-depth insights into the subjective and contextual dynamics shaping voter behavior (Figure 1).

A total of 19 participants were recruited through purposive sampling to capture a diverse cross-section of Indonesian voters. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 43 years. Younger voters included university students and first-time voters (ages 18–22), while older participants (ages 35–43) had accumulated broader life experience and longer electoral histories. The sample was also balanced by gender, comprising both male and female participants.

In terms of education, the participants represented a wide spectrum: one had completed elementary school, five had junior high school education, seven had senior high school education, three held bachelor’s degrees, and one held a master’s degree. This diversity in formal education was important for analyzing how varying levels of knowledge and training shaped the ways in which voters accessed, interpreted, and evaluated political information.

Electoral experience also varied considerably. Several younger participants were preparing to cast their first or second ballots, whereas older participants had taken part in multiple national and local elections. This demographic spread across age, gender, education, and electoral involvement provided a basis for exploring both emerging and established patterns of voter cognition. Such variation was essential for uncovering the nuanced, experience-based decision-making processes analyzed through the Behavioral Decision Theory (BDT) framework.

2.3 Sampling and participant selection

Participants were selected through purposive sampling to ensure diversity in electoral experiences, including age, gender, educational background, geographic location, and prior voting history. This diversity was intended to capture the range of decision-making processes across different voter demographics, while retaining the depth of qualitative insights afforded by this methodology.

2.4 Data analysis procedure

The verbal data obtained from participant interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis (Evans and Lewis, 2018). Coding was applied to identify patterns and recurring narratives that reflect the decision-making logic of voters (Simiyu, 2008). The analysis was anchored in the principles of Behavioral Decision Theory (BDT) while incorporating inductive coding to allow emergent themes to surface from the data (Schlinger, 1996).

Through this process, voters’ decision-making was classified into distinct typologies according to how individuals engaged with political information, managed cognitive dissonance, and reached their final choices. These typologies illuminated variations in decisional strategies, including intuitive selection, strategic compromise, emotional voting, and norm-based decision-making (Visser, 1996).

3 Discussion

3.1 The party system and elections in Indonesia

The 2024 election represents the sixth national electoral event since the inaugural democratic contest in 1999. Subsequent elections were held in 2004, 2009, 2014, and 2019. All six have employed a proportional electoral system (Agustino, 2007) within the framework of a multi-party system (Duverger, 1956). Each election has included both a presidential election (Pilpres), to select the president and vice president, and a legislative election (Pileg), to appoint members of the national legislature (DPR) as well as provincial and district/city legislatures (DPRD).

In the 2024 election, three candidate pairs contested the presidency. Candidate pair number one was Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar (Anies–Muhaimin, commonly referred to as AMIN), supported by the National Awakening Party (PKB), the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), and the National Democratic Party (Nasdem). Candidate pair number two was Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabuming Raka, endorsed by seven parties: Gerindra, Golkar, the Democratic Party, the National Mandate Party (PAN), the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI), the Crescent Star Party (PBB), and Garuda. The third pair consisted of Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud MD, supported by the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP), the United Development Party (PPP), the Perindo Party, and the People’s Conscience Party (Hanura).

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest Islamic mass organization in Indonesia, has historically played a central role in electoral politics. Its influence is rooted in a framework comprising three elements: the kiai (religious leaders), pesantren (Islamic boarding schools), and affiliated political parties (Chalik, 2011). Within NU’s political tradition, kiai are regarded as elites who not only mobilize votes but also frequently serve as party administrators, legislative candidates, and government officials. As the country’s largest traditionalist Muslim organization with a strong base among lower socioeconomic groups, NU continues to shape voter preferences across presidential, legislative, and regional elections (Chalik, 2011).

Indonesia’s legislative electoral system allocates seats at the national, provincial, and district/city levels according to the proportion of votes received (Kartini, 2017). Since 2004, this has combined proportional and district-based elements. Voters may cast ballots for parties, thereby delegating candidate selection to party leadership, or directly for individual candidates, reflecting district representation (Dede Sri Kartini et al., 2010).

3.2 The decision-making process is influenced by several factors

The 2024 general election in Indonesia presented a critical opportunity to examine the interaction of psychological, technological, and social dynamics in shaping voter decision-making. As the largest democratic exercise in Southeast Asia, with more than 204 million eligible voters, Indonesia provides a particularly important case for analyzing emerging patterns of political engagement. Recent scholarship has emphasized the micro-foundations of electoral behavior, highlighting the interplay of rational calculation, emotional resonance, digital media, and identity politics (Dong, 2022).

Technology played a central role in 2024, particularly through the influence of digital platforms on political communication and preference formation. Nugroho and Sihotang (2024), drawing on mixed methods, found that 62 percent of Generation Z respondents relied on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube as their primary sources of political information. As Younus et al. (2025) observe, “digital platforms are not merely channels of political messaging but active agents in constructing political realities.” These findings underscore the importance of agenda-setting and framing theories, which suggest that media influence extends beyond issue salience to the interpretive frameworks employed by voters (Highton, 2010).

Voter rationality emerged as another central theme. Lilleker et al. (2024) showed that while some voters engaged in deliberate policy evaluation, many others relied on heuristics such as party affiliation, candidate appearance, or religious identification. Their study also revealed that high levels of internal political efficacy were associated with more reflective decision-making, whereas low external efficacy particularly in rural areas often produced strategic apathy. As Fournier et al. (2003) argue, apathy among rural voters is often a rational response to a history of political marginalization, not ignorance or disinterest. These findings complicate traditional rational-choice assumptions, illustrating how structural disenfranchisement reshapes behavioral strategies.

Behavioral Decision Theory (BDT) further illuminates how voters process political information. Fournier et al. (2003), analyzing 1,200 voter interviews from Java and Sumatra, found that electoral decisions were frequently shaped by emotional trust and perceptions of authenticity rather than programmatic alignment. As one respondent explained, “I believe this candidate is sincere not because of their program, but because of how they talk and listen to the people” (Mende and Müller, 2023). Such evidence highlights the integration of emotional cognition and bounded rationality in the voter decision-making process.

The media environment of 2024 also reinforced the dynamic nature of voter preferences. Falasca and Grandien (2017), in a longitudinal panel study, demonstrated that debates, scandals, and endorsements generated cumulative impressions that shifted voter choices week by week. This aligns with Lau and Redlawsk’s (2006) theory of online processing, which holds that voters maintain a “running tally” of impressions that is continuously updated as new information becomes available.

First-time voters added further complexity. Risnanto et al. (2023) found that although younger voters displayed considerable enthusiasm, algorithmically curated information bubbles often reinforced pre-existing preferences and limited exposure to alternative perspectives. As Risnanto et al. (2023) note, “young voters are very interested, but their information bubbles are often set up to reinforce their current preferences instead of expanding them.” These findings point to the urgent need for initiatives in digital literacy and civic education.

At the same time, local socio-political structures retained significant influence, particularly in areas with limited digital penetration. Ethnographic research in Eastern Indonesia revealed that patron–client networks and communal ties continued to guide electoral choices. As one respondent explained, “we vote according to our traditional leaders’ advice because they know who can be trusted” (Halimatusa'diyah and Jannah, 2025). In urban centers, by contrast, Marcinkiewicz (2018) found that issue-based concerns such as inflation and employment often shaped voter priorities, but where party platforms lacked clarity, identity factors such as ethnicity and religion became decisive. As Marcinkiewicz (2018) concludes, identity politics does not supplant rational policy analysis; it enhances it when distinctions are obscured.

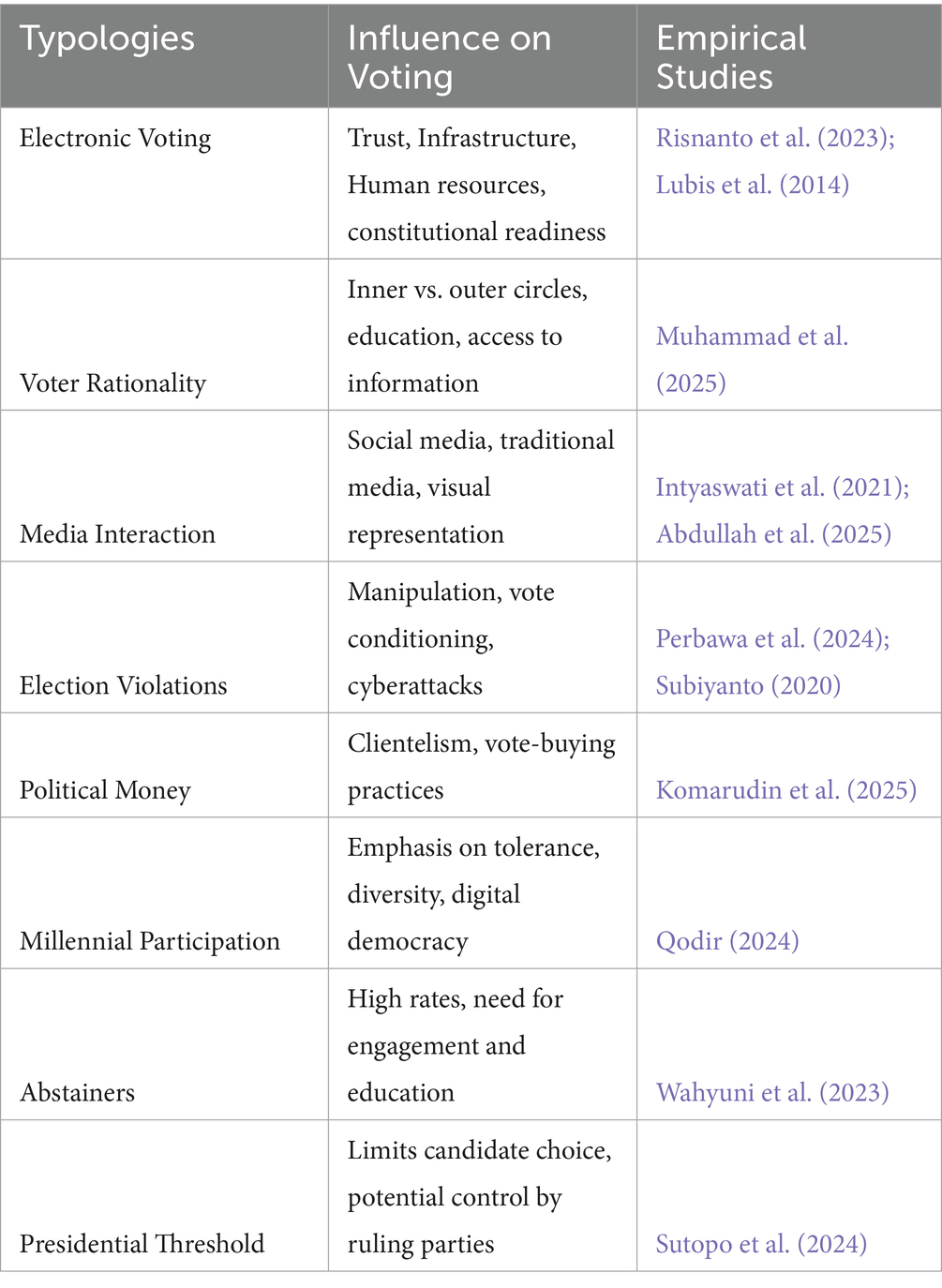

Taken together, these studies demonstrate the profound complexity of voter decision-making in Indonesia’s 2024 general election. Electoral behavior was shaped simultaneously by technological innovation, bounded rationality, evolving media environments, and enduring socio-cultural traditions. Future research must continue to develop integrative frameworks that account for both digital modernity and traditional social capital in order to more fully explain patterns of democratic participation (Table 1).

The rationality of voter behavior varied significantly across demographic contexts. For instance, voters in East Luwu’s inner mining communities tended to adopt performance-based evaluations, assessing candidates according to past achievements and policy proposals. By contrast, voters in surrounding areas were more heavily influenced by kinship ties, clientelistic exchanges, and enduring partisan loyalties (Muhammad et al., 2025). These contrasts highlight the importance of tailored campaign strategies and targeted political education initiatives.

The interaction between traditional media and digital platforms also emerged as a central factor shaping electoral choices. Social media platforms—particularly X, TikTok, and Instagram played an increasingly influential role in shaping political discourse and guiding voter preferences. At times, however, the interaction of digital content with traditional outlets such as newspapers risked distorting voter judgments (Intyaswati et al., 2021). Visual representations in campaign media, including images and videos, further reinforced affective evaluations by enhancing candidates’ personal appeal and shaping emotional responses (Abdullah et al., 2025).

Concerns about electoral integrity persisted. Reports of violations—including rule manipulation, vote conditioning, cyberattacks, and money politics raised doubts about procedural fairness and democratic accountability (Perbawa et al., 2024; Subiyanto, 2020). Addressing these vulnerabilities remains a critical priority for sustaining democratic legitimacy.

Money politics and clientelism continued to undermine performance-based evaluation of candidates. In several regional elections, financial inducements were found to significantly influence voter decisions, reinforcing transactional rather than programmatic politics (Komarudin et al., 2025).

Finally, generational dynamics shaped participation in distinctive ways. Millennials, in particular, are expected to play an increasingly prominent role in political communication and civic engagement. Qodir (2024) emphasizes that this generation’s openness to diversity and inclusivity constitutes a valuable resource for strengthening democratic practices.

3.3 Closed decision-making process

Closed decision-making can be understood as a heuristic strategy designed to minimize cognitive effort, commonly referred to as endorsement (Lau and Redlawsk, 2006). Endorsement involves “following the advice of close friends, trusted political leaders, or social groups” rather than independently evaluating alternatives (Belt, 2007). Informants in this category demonstrated strong reliance on family, acquaintances, and immediate social environments when casting their votes. Rather than actively seeking information, they absorbed only limited cues often unrelated to policy and translated these into electoral choices. Such voters frequently repeated past behaviors, such as consistently supporting the same party, or deferred to recommendations from peers and relatives.

For instance, one informant consistently supported Golkar candidates for the presidency, DPR, and provincial DPRD, citing family tradition. However, in the regency-level DPRD election she switched to a candidate who provided direct financial inducements, reflecting the influence of money politics. This pattern underscores how material incentives can override partisan loyalty and weaken long-standing identifications, a trend also documented in Tabalong Regency, South Kalimantan, where low educational attainment increased susceptibility to clientelism. In such cases, the coattail effect was absent: rather than aligning legislative choices with presidential preferences, voters prioritized immediate, tangible benefits (Ionescu, 2018).

Other informants revealed similar patterns. Voters with only elementary education selected presidential candidates such as Prabowo Subianto on the basis of repeated candidacy and media exposure, particularly television coverage. Candidate familiarity, perceived speaking style, and visibility in local visits shaped preferences more than programmatic detail. One respondent who previously supported Golkar shifted to the Democratic Party in legislative contests, describing the party as “well known” and “established.” Another, a religious organization activist, chose Prabowo–Gibran after hearing endorsements from friends, while relying on parental guidance in selecting legislative candidates.

These cases illustrate the defining traits of closed decision-making: limited information search, reliance on heuristics, and deference to trusted networks. Such voters avoid complex evaluation, simplifying choices through cues such as party symbols, community advice, or financial inducements (Garvin, 2003; Huddy et al., 2023). Fitzpatrick and von Nostitz (2024) characterize them as “pragmatic cognitive misers,” who infer political alignments from minimal knowledge rather than deliberating on policy. Although they occasionally absorb candidate information passively, they do not use it as the basis for systematic evaluation. Electoral participation is thus reduced to minimal engagement casting a ballot largely in reaction to prevailing social conversations while multidimensional contests are perceived through a single, simplified lens (Hossain Faruk et al., 2024).

3.4 Open decision-making process

For voters who engage in open decision-making (hereafter referred to as open-process voters), candidate background and policy programs constitute the primary considerations in determining electoral choices. These voters place significant weight on leadership qualities, professional track records, and the substance of proposed policies. In this framework, candidates play a decisive role in shaping voter preferences, as their credibility, programmatic vision, and ability to address pressing public issues are carefully scrutinized before support is given.

In any election, the personalities of candidates and their perception by the voters play an important role in pulling votes or turning votes away from parties. As such, a voter may identify with a party but many particularly dislike the candidate on the ballot paper at a certain election (Zwicker, 2016).

Meanwhile, the issues or programs that can influence an individual’s choice have the following criteria:

1. The issue must be recognized by the voter.

2. The issue must evoke some degree of preference for one policy solution over another.

3. The voter must believe that one candidate is more likely to work for the voter’s preferred policy solution (Zwicker, 2016).

Open-process voters do not approach political parties through the lens of loyalty or long-standing identification. Instead, parties serve primarily as indicators that help situate candidates within the broader political landscape. These voters actively absorb information about both candidates and programs, assessing them in a varied and in-depth manner. Their electoral choices are driven by the aspiration to make accurate and well-considered decisions. During the decision-making stage, they gather information about candidates’ personal backgrounds, policy positions, and partisan affiliations. By consulting diverse sources, they construct complex and detailed insights that serve as the foundation for their final choices.

This behavior closely resembles Model 1: Rational Choice Dispassionate Decision Making. However, in the present study, open-process voters evaluate candidates not with the aim of maximizing personal utility, but through a broader social motivation. From this perspective, decision-making is grounded in a desire to select leaders deemed capable of addressing collective needs rather than fulfilling individual interests (Muhammad et al., 2025).

The social motivation perspective also resonates with the concept of expressive voting, whereby citizens cast ballots not to secure direct personal gain but to express values, principles, or visions for the public good. Within this framework, respondents demonstrated thoughtful and comprehensive evaluation of candidate programs and leadership qualities, underscoring the role of civic responsibility as a central driver of electoral choice:

The theory of expressive voting offers a believable resolution to the paradox. Rational, self-interested individuals sometimes, perhaps often, engage in behavior that is not motivated directly by a benefit-cost calculation. With respect to voting, the application is straightforward: individuals vote because they are expressing themselves about the candidate(s) and/or issues, not because they expect to alter the outcome of the election (Komarudin et al., 2025).

For voters who engage in expressive voting, elections function primarily as a means of expressing preferences regarding candidates or issues rather than as mechanisms for directly influencing electoral outcomes. Their motivation lies in articulating values and convictions, even if the act of voting does not alter the final result. After gathering information, these voters evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the candidates who command their attention, consider proposed policy programs, and ultimately arrive at a decision. In this process, party affiliation, candidate qualities, and programmatic content are all weighed as integral components of their decision-making.

Informant IR selected presidential candidate pair number three after examining Ganjar Pranowo’s professional background and leadership record as Governor of Central Java, particularly his initiatives in the fields of arts and technology. She viewed his leadership style as consistent with her expectations of effective governance. In addition, she monitored his campaign through Instagram, where she followed his activities and policy messaging. Among his proposals, the promise of free internet access was particularly appealing, as she believed it aligned with the demands of the Industry 4.0 era.

In legislative contests, IR applied the coattail effect, reasoning that her support for Ganjar as a presidential candidate should be extended to PDIP’s legislative representatives. For her, the qualities of PDIP’s leadership were embodied in Ganjar himself, making party loyalty in this instance a reflection of confidence in the presidential candidate’s vision and credibility.

At one campaign event, IR observed that several attendees altered their voting preferences after receiving small cash inducements. This experience heightened her concerns about electoral integrity and motivated her to seek more reliable information through the official KPU website, which she believed should provide comprehensive data on legislative candidates in order to reduce the burden on individual voters. Ultimately, she conducted her own searches and followed the social media accounts of both presidential and legislative candidates, using these sources to inform her decisions.

For open-process voters, the KPU website often serves as a primary source of information on both presidential/vice-presidential candidates and legislative contenders for the DPR, provincial DPRD, and district/city DPRD. This was evident in the case of Raisa Adisti, who applied the coattail effect by consistently supporting the NasDem Party, endorsing Anies Baswedan in the presidential race and extending her vote to NasDem’s legislative candidates. Her decision was grounded in her assessment of Anies’s record as Governor of Jakarta (2017–2022), which she regarded as evidence of effective leadership.

Raisa emphasized that televised presidential debates played a central role in shaping her evaluation of the candidates. At the same time, she expressed concern about limited transparency in election management, particularly with respect to dispute resolution. In selecting legislative candidates, she relied on their social media presence, paying close attention to their vision and mission statements as well as their public activities. These factors collectively informed her choices and reinforced her support for NasDem’s broader political platform.

M. Kurniawan exemplifies an open-process voter who actively sought information from multiple sources, including social media, news outlets, and interpersonal discussions. Initially inclined toward Prabowo Subianto, he reconsidered his choice after Gibran Rakabuming Raka was announced as Prabowo’s running mate. He interpreted Gibran’s candidacy as a form of dynastic politics and viewed the Jokowi administration’s support as a manipulation of constitutional norms. This perception ultimately led him to shift his support to candidate pair number one. His decision was reinforced by campaign observations, where he noted that this pair refrained from distributing material inducements, unlike other candidates who provided food or envelopes of cash.

In legislative contests, Kurniawan evaluated candidates individually. He voted for Rashid Rajiv from the Democratic Party, citing his programmatic proposals, leadership vision, and personal integrity qualities that convinced him to join Rajiv’s campaign team. He emphasized that Rajiv’s professional background as a businessman suggested a lower likelihood of engaging in corrupt practices. For the provincial DPRD, however, Kurniawan expressed uncertainty and ultimately supported a PKS candidate, reasoning that the party’s role in parliamentary opposition reflected accountability and oversight. He also acknowledged Bandung Regency’s reputation as a PKS stronghold. At the regency level, he voted for Adjat Sudrajat from PKB, his university lecturer, whose critical stance toward government policies convinced him of his competence and suitability for legislative office.

Kurniawan’s case illustrates the complexity of open-process voting: while he applied rational evaluation to presidential and legislative candidates, he also weighed broader ethical concerns, personal experiences, and local political dynamics. His choices demonstrate both independence from partisan loyalty and the nuanced ways in which programmatic, moral, and contextual factors converge in open decision-making.

3.5 Semi open decision making process

Semi-open decision-making refers to a process in which voters establish subjective criteria or boundaries in advance and then evaluate candidates within these limits. Unlike closed-process voters, who rely heavily on heuristics and avoid active information-seeking, semi-open voters deliberately gather information but restrict their consideration to candidates affiliated with preferred parties, organizations, or social groups. At the same time, unlike open-process voters, they do not evaluate the full range of available alternatives. Instead, they use a cognitive map a framework aligning facts with personal preferences that guides their decision-making and shapes perceptions of candidate compatibility (Razak et al., 2025).

With this set of criteria, semi-open voters will seek out information and weigh the positive and negative aspects of the candidates based on their subjective expectations that is, the criteria that also serve as boundaries they have set from the beginning. This is the general profile of voters who fall under the semi-open decision-making process category. On the other hand, voters in the open decision-making process will consider all available information without being limited by factors such as political party affiliation, social group membership, or candidate status. In contrast, voters in the closed decision-making process do not establish clear criteria or boundaries beforehand; instead, any information they encounter is immediately considered as a potential basis for their choice.

Voters who make decisions through a semi-open process absorb information about candidates or their supporting parties in a limited way. In one case, for example, they only gathered information about candidates representing PKB. These respondents evaluated candidates within narrow parameters, meaning they had only minimal knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of each candidate, and then proceeded to the decision-making stage based on that limited evaluation.

From the outset, respondents narrowed their choices based on a perceived alignment between party identity and candidate characteristics. Their final decisions were shaped by personal, though not exclusively material, considerations. These boundaries functioned as guiding criteria in candidate selection, often encompassing shared religious affiliations, denominational ties, or the candidate’s social standing within a religious community (Fauzan, 2022).

The status attached to a candidate can influence semi-open decision-making in two principal ways. It may serve as a reference point when voters attribute positive values to traits already associated with the candidate, such as a professional track record or public service history. Decision-makers in this category are willing to engage in complex evaluation, but only within clearly defined boundaries (Turska-Kawa, 2013). In practice, this complexity is limited to candidates who share the voter’s party affiliation, religious organization, or denominational identity (Gallhofer and Saris, 1988). Candidates outside these criteria are excluded from consideration at the outset.

In this study, organizations such as Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) functioned as decisive boundaries. For many informants, NU was not only regarded as a religious organization but also as a representation of denominational identity, guiding their preferences for both presidential and legislative candidates.

An informant named Septian exemplified semi-open decision-making. He supported Anies Baswedan for the presidency, citing Anies’s tenure as Minister of Education and Culture where he abolished the National Examination as well as his record as Governor of Jakarta, where he was perceived as effective in addressing infrastructure, flooding, and traffic congestion. Septian also valued the candidacy of Anies’s running mate, Muhaimin Iskandar, who had served both as a member of parliament and as chairman of PKB. Consistent with these boundaries, Septian extended his support to DPR, provincial DPRD, and district/city DPRD candidates affiliated with PKB and Nahdlatul Ulama (NU). He actively followed campaign activities and consulted the Bijak Memilih (“Vote Wisely”) platform as part of his decision-making process.

The reliance on NU as a decisive boundary reconfirms findings from the author’s earlier 2015 study, in which organizational affiliation functioned as a critical determinant of voter choice in Bandung Regency. However, this study also identifies an emerging variation beyond the semi-open model: the mixed decision-making process, where voters combine identity-based boundaries with evaluations of candidate performance and track record. The following section provides an illustration of this hybrid approach.

The persistence of religious identity actors most notably affiliation with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) remains a significant determinant of political preferences in Bandung Regency, as earlier research in 2015 also demonstrated. At the same time, this study reveals the emergence of a mixed decision-making model, in which voters combine identity-based boundaries with evaluations of candidate performance and track record. This hybrid approach highlights the gradual shift from exclusive reliance on organizational affiliation toward more complex, multidimensional criteria in electoral choice.

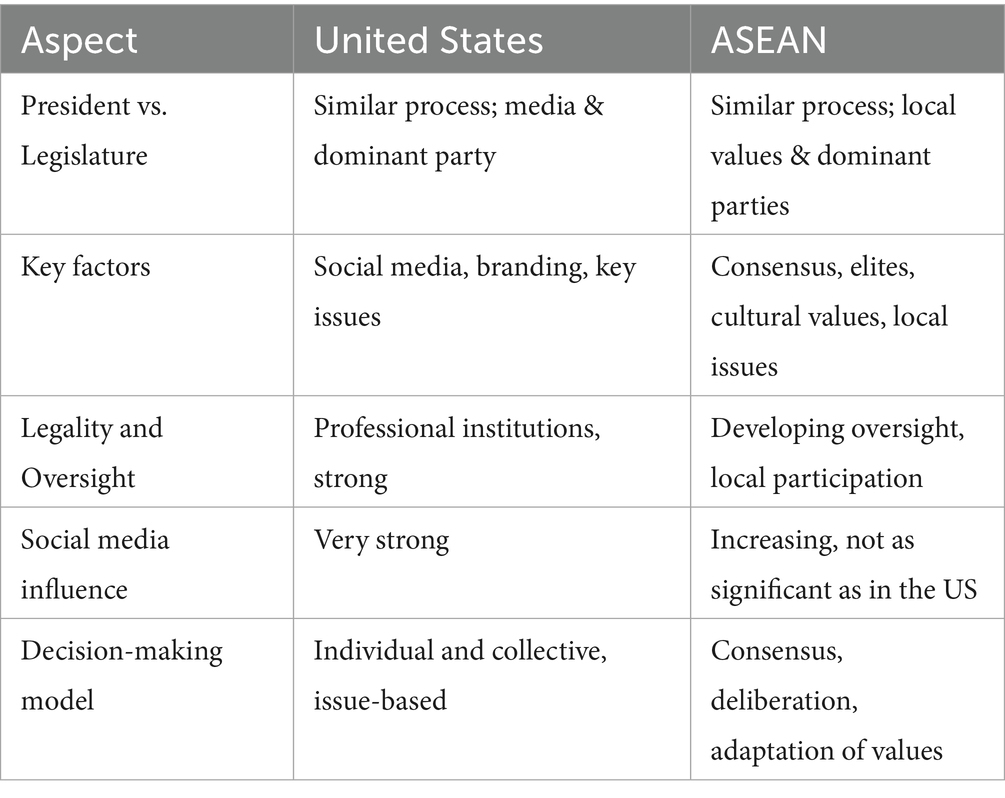

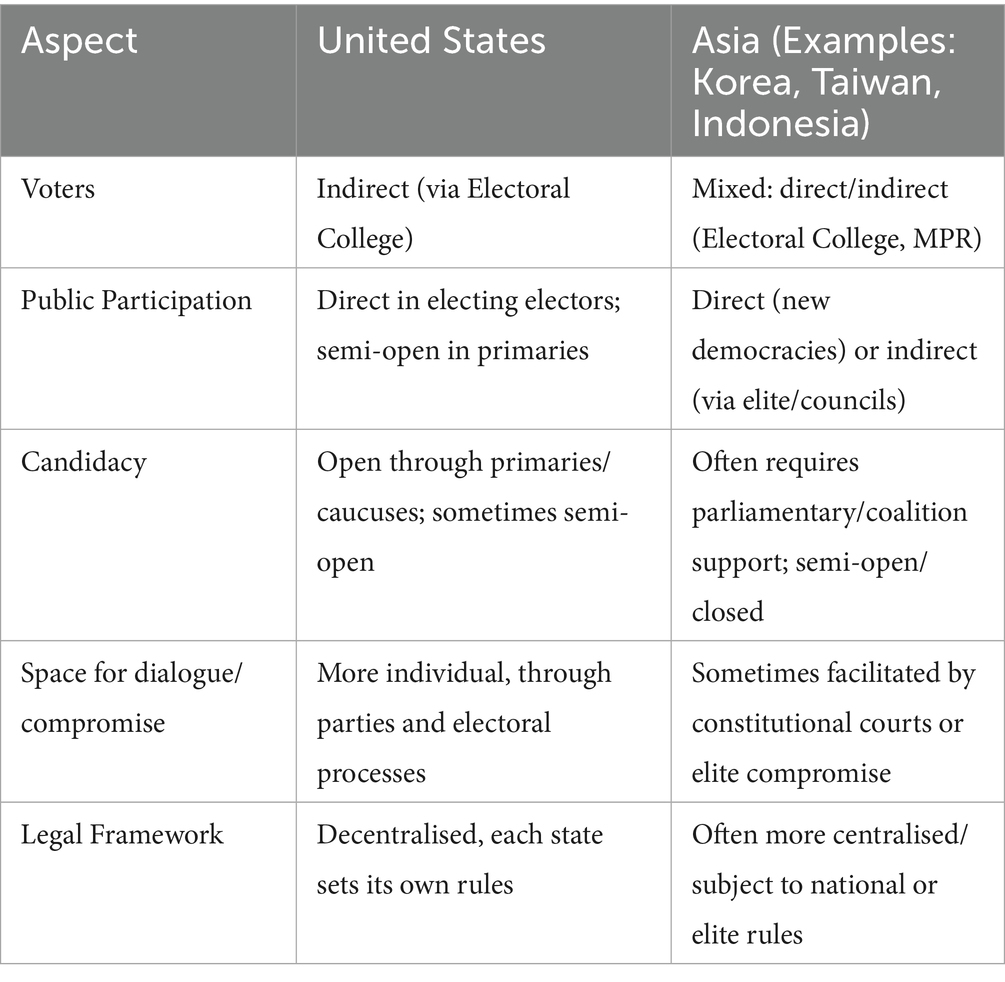

In comparative perspective, Indonesia’s voter behavior reflects distinctive characteristics within the ASEAN region. Unlike patterns observed in advanced democracies such as the United States where party identification and ideology typically provide stable anchors Indonesian voters often blend identity-based orientations with context-dependent assessments of candidates and policies. The identification of semi-open and mixed decision-making processes therefore carries broader implications for understanding how social identity and performance evaluation interact in transitional democracies (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison between ASEAN countries and the United States in the use of semi open decision making processes.

3.6 Mixed decision-making process

The mixed decision-making category captures voters who employ multiple strategies simultaneously across different electoral levels. For instance, a voter may adopt a semi-open process in the presidential and DPR elections by considering candidate profiles, party affiliations, and policy programs, while relying on a closed process in the provincial DPRD election and an open process in the district/city DPRD election (Golder, 2006). In presidential contests, such voters engage with information actively, weighing party platforms and candidate performance. In contrast, their legislative choices—particularly at the provincial or regency levels—are shaped more by heuristics and endorsements than by systematic evaluation (Belt, 2007).

This pattern confirms a broader tendency: as the number of choices increases, voters become more likely to rely on cognitive shortcuts. The phenomenon mirrors findings from the United States, where primary elections with multiple candidates often encourage heuristic-based decision-making to a greater extent than general elections. In the Indonesian context, mixed decision-making thus illustrates the interaction between information-processing limits and the structural complexity of concurrent elections.

The case of RA illustrates the dynamics of mixed decision-making, in which different strategies are applied across electoral levels. In the presidential election, RA supported Anies Baswedan on the basis of both party affiliation and personal evaluation. He emphasized Anies’s endorsement by PKB, as well as his perceived qualities of good character, strong educational background, and credible track record. Given the importance he attributed to the presidential contest, this decision was made through careful consideration, reflecting a semi-open process.

For the DPR election, RA again chose a PKB candidate, partly because the party supported the AMIN pair (Anies–Muhaimin), but also due to the candidate’s status as a senior PKB figure who had chaired Commission II in the DPR and was active in the AMIN campaign. Here, RA restricted his evaluation exclusively to PKB candidates, demonstrating the bounded reasoning characteristic of semi-open decision-making.

In contrast, his decision for the provincial DPRD election reflected a closed process. He regarded the race as less significant and therefore cast his vote primarily to avoid abstention. He selected the child of the DPR candidate he had already supported, without comparing candidates from other parties or engaging with their programs. This choice was made on the basis of family association and convenience rather than systematic evaluation.

At the regency level (district/city DPRD), RA employed a more open approach. He selected a Golkar candidate, describing the candidate as youthful, active in visiting the electoral district, and representing Indonesia’s oldest and most established political party. While both the Golkar candidate and another competitor shared the advantage of frequent local visits and affiliation with parties supporting the AMIN pair, RA perceived Golkar’s longer history of national development including in Bandung Regency as decisive. His choice in this contest therefore combined considerations of candidate characteristics with party reputation, aligning more closely with open-process decision-making.

RA’s case demonstrates how mixed decision-making unfolds in practice. Voters may carefully deliberate in high-salience contests such as the presidency, adopt bounded reasoning in national legislative elections, fall back on heuristics in provincial contests, and engage in broader evaluation at the regency level. This hybrid strategy highlights the interaction of voter priorities, perceptions of electoral significance, and contextual factors in shaping decision-making across Indonesia’s multi-level elections.

The case of Alham Muhammad Haidar further illustrates the dynamics of mixed decision-making, in which different strategies are applied across electoral tiers. For the presidential election, he relied on a closed process. He supported Prabowo Subianto, citing admiration for his long-standing reputation and familiarity with the “Free Lunch Program.” His decision reflected continuity of prior impressions rather than active evaluation of alternative candidates.

At the national legislative level (DPR), however, Haidar employed a more selective, semi-open process. He considered Atalia, a Golkar candidate with whom he had previously collaborated through an NGO she led. Her campaign’s emphasis on social activities reinforced his positive impression, and he further evaluated her through social media, which he used to follow her campaign initiatives. He described Atalia as capable and inspiring, affirming his decision to support her. This choice demonstrated selective information-seeking bounded by party and personal association.

For the provincial and regency-level DPRD elections, Haidar reverted to a closed strategy, basing his decisions largely on prevailing preferences in his immediate social environment. Here, his voting behavior reflected deference to local cues rather than systematic evaluation.

Voters frequently rely on heuristics—mental shortcuts that simplify political decision-making in both legislative and presidential elections (Colombo and Steenbergen, 2020). In one case, an informant initially supported Prabowo Subianto but later shifted to Anies Baswedan. This decision was driven by disapproval of Gibran Rakabuming Raka’s candidacy, which he perceived as premature, and by skepticism about the feasibility of Prabowo’s proposed free meal program. His eventual choice of Anies reflected the application of ideological schemata, as he associated the Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (PKS) with trusted Islamic boarding school alumni and thus prioritized ideological conformity in presidential voting.

In legislative contests, however, different heuristics came into play. The informant was strongly influenced by his father’s recommendation, rooted in long-standing admiration for Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) based on shared military backgrounds. This reliance illustrates the use of personal stereotype heuristics, whereby trust in a prominent figure is extended to candidates affiliated with their party in this case, the Democratic Party. His legislative choices included Dede Yusuf, selected for his reputation in education, and Saeful Bahri, chosen for his efforts to promote fair elections.

This case highlights the flexible use of heuristics across electoral contexts. Voters may apply ideological cues in presidential races, while in legislative contests they draw on personal stereotypes, emotional attachments, or reputational considerations. The findings demonstrate that heuristics are not employed uniformly but vary according to the level of available information, emotional involvement, and the complexity of electoral choices, even in simultaneous presidential and legislative elections.

Religion continues to function as a powerful frame shaping voter preferences across presidential, DPR, and DPRD contests. According to Voting Behavior theory (Bianco, 1984), electoral choices are not driven solely by rational instrumental factors such as policy or performance but are also influenced by socio-psychological considerations, including religious identity. This was evident in voters who supported Anies Baswedan because of his association with Islamic values and endorsement by religiously oriented parties such as PKB. Social Identity theory (Abrams, 2001) further explains this pattern, as voters often gravitate toward candidates and parties perceived to embody their group identity in this case, Islamic identity.

At the same time, the findings demonstrate that identity politics operates in interaction with other considerations. In legislative races, some voters supported the Democratic Party based on emotional ties and perceptions of candidate morality, while at the provincial level others selected PKS due to its engagement with youth and religious activities. This suggests that while religion acts as a primary filter, factors such as social networks (friends, talk shows, social media) and candidate track records also influence decision-making.

These dynamics underscore the effectiveness of personalized political strategies, such as interactive forums (Desak Anies) or religious gatherings, in cultivating emotional closeness with voters. Yet such approaches also carry the risk of confirmation bias, as voters may neglect substantive policy evaluation in favor of reaffirming religious identity. If widespread, this trend could exacerbate religiously based political fragmentation and weaken programmatic competition. Conversely, parties and candidates who integrate religious values with broader social concerns for instance, linking Islamic identity with equitable development in West Java demonstrate strong appeal to religious constituencies.

Overall, these findings reinforce earlier research (Aspinall, 2019) showing that religion and collective identity remain decisive in Indonesian voter behavior. However, they also highlight that religious framing interacts with media exposure, interpersonal networks, and performance-based evaluations. The persistence of identity politics therefore presents both a challenge and an opportunity: it may constrain substantive deliberation, but it also offers pathways for candidates and parties to bridge values-based appeals with programmatic agendas, thereby shaping the trajectory of democratic consolidation in Indonesia.

In elections characterized by mixed decision-making, the coattail effect is often visible in legislative contests. For instance, Anies Baswedan’s popularity as a presidential candidate translated into increased support for PKS candidates at both the DPR and provincial DPRD. However, this effect diminished at the district level, where voters prioritized tangible local performance such as Riki Ganesha’s contributions to road improvements over national-level affiliations. This pattern aligns with Issue Voting Theory (Converse et al., 1966), which suggests that when elections occur at levels of government closer to citizens, pragmatic and performance-oriented considerations tend to outweigh broader ideological or identity-based cues (Naurin and Oscarsson, 2017).

These findings also resonate with Redlawsk’s (2006) insights on the use of heuristics in electoral decision-making. He shows that voters rely more heavily on heuristics in primary elections, where the number of candidates is higher and the complexity of choices greater, than in general elections, where only two candidates remain and much of the relevant information such as party affiliation, ideology, or candidate reputation is already familiar. In the Indonesian case, the simultaneous presidential and legislative elections generated similar dynamics. At the national level, the large number of candidates and overlapping coalitions encouraged the use of heuristics such as coattail voting and group endorsements. At the district level, by contrast, where contests involved fewer candidates and more direct familiarity with their records, voters shifted toward pragmatic evaluations of local performance (Figure 2).

In some instances, open decision-making was observed only in the presidential contest. Novita Sari, for example, selected Prabowo Subianto in 2024, as she had in 2019, believing it would be his final opportunity to contest the presidency. She was attracted to his proposed social programs, particularly the free lunch initiative, and valued his military background as evidence of leadership. Gibran Rakabuming Raka’s candidacy further appealed to her, as she interpreted his youth as a symbol of generational renewal in Indonesian politics. By contrast, her legislative choices reflected less engagement. She voted for Golkar candidates in the DPR and DPRD elections without deliberate consideration, primarily to fulfill her sense of electoral participation. At the regency level, she supported a PDIP candidate after being offered material goods, underscoring the persistence of clientelistic inducements in shaping legislative voting behavior.

Other cases exemplified semi-open decision-making. Imas Tuti supported Prabowo–Gibran in the presidential election because of Prabowo’s perceived decisiveness and Gibran’s role in the campaign she attended locally. Human rights allegations against Prabowo did not influence her choice, as she focused instead on leadership style and perceived alignment with her values. This selective evaluation of a favored candidate, without comparison to alternatives, reflects a semi-open process. For the DPR, she similarly selected a candidate based on personal attributes, emphasizing community engagement and visibility in local activities. Her votes for Gerindra at the provincial and regency levels, however, were made without further deliberation, illustrating a closed process driven by habit rather than active evaluation.

Heuristic-based decision-making also played a role in several cases. Atang supported the Prabowo–Gibran ticket largely because of his perception that President Joko Widodo endorsed the pair. This demonstrates the influence of elite endorsements as a heuristic cue, enabling voters to form preferences without close scrutiny of policy details. Such reliance on endorsements underscores the broader role of trust in influential figures in shaping electoral choices.

Finally, habitual voting was also evident. Some voters consistently supported Golkar candidates, citing the party’s long-standing strength in their region and its historical reputation for stability. These patterns align with research demonstrating that partisan loyalty and repeated voting behavior often persist due to emotional attachment and established routines rather than programmatic evaluation.

Collectively, these cases highlight the diversity of voter decision-making in Indonesia’s 2024 elections. Open, semi-open, closed, and heuristic strategies frequently intersected, depending on the salience of the contest, the availability of information, and the perceived importance of the office. The findings suggest that while rational evaluation occurs in high-profile races, clientelism, habit, and heuristic shortcuts continue to structure much of voter behavior in legislative elections, reinforcing the complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and socio-cultural factors in Indonesian democracy.

Social media platforms such as TikTok have become central to the dissemination of political information, particularly among younger voters, who increasingly evaluate candidates on the basis of digital content related to programs and image (Lima et al., 2023). Yet, the absence of strong motivation to seek detailed information often results in reliance on simple heuristics, such as personal proximity or ideological affinity, especially in legislative contests. These dynamics suggest that future campaign strategies must not only strengthen candidates’ personal branding and utilize digital platforms effectively, but also cultivate loyal voter networks through issue-based and personalized engagement. At the same time, expanded political education is essential to enhance citizens’ capacity to evaluate candidates critically, thereby reducing dependence on emotional appeals or limited cues.

The findings of this study also resonate with broader patterns of mixed decision-making observed in other contexts. In Indonesia, presidential elections often encourage more deliberative evaluation, while legislative contests at the provincial or district level remain shaped by heuristics and identity filters. This divergence parallels comparative insights: within ASEAN, identity-based and clientelistic factors remain influential, whereas in the United States, mixed decision-making is most evident in primary elections with multiple candidates, where voters rely on heuristics due to the complexity of choice. Such comparisons highlight both the distinctive features of Indonesian electoral behavior and its contribution to broader understandings of how information, identity, and institutional design interact in shaping democratic decision-making (Table 3).

4 Conclusion

This study provides an in-depth examination of the decision-making processes that shaped voter behavior in Bandung Regency during Indonesia’s 2024 general election. Drawing on Behavioral Decision Theory (BDT) and qualitative verbal protocol data, five distinct typologies of decision-making were identified: closed, semi-open, open, mixed, and coattail-driven. These categories illustrate a continuum of cognitive engagement, ranging from automatic, heuristic-based responses to reflective and expressive evaluations grounded in candidate profiles, policy programs, and broader sociopolitical considerations.

The empirical findings highlight the complex interplay of technological change, emotional trust, religious affiliation, media dynamics, and perceptions of political efficacy in shaping electoral decisions. Younger voters relied heavily on platforms such as TikTok and Instagram, where candidate branding and digital messaging influenced preferences. Endorsements from influential figures, enduring partisan loyalties, and identity markers rooted in religion or organizational membership further shaped outcomes. The emergence of the mixed decision-making model underscores the contextual nature of rationality, as voters adjusted strategies according to the salience of contests and the cognitive demands of multi-level elections.

These findings contribute to broader debates about democratic participation in transitional contexts. In Indonesia, electoral behavior is revealed to be less a matter of linear rational calculation than of adaptive strategies shaped by cognitive asymmetries and social embeddedness. This underscores the importance of political education initiatives aimed at strengthening critical information analysis, countering disinformation, and fostering multidimensional evaluation of candidates. Moreover, the variation in decision-making styles across electoral levels suggests that reforms must address not only institutional and legal frameworks but also the behavioral and informational environments in which citizens make choices.

Ultimately, this research expands traditional theories of voting behavior by advancing a decision-centric framework that emphasizes process over outcome. Voter rationality emerges here as dynamic, relational, and deeply rooted in social context. Recognizing electoral behavior as a multifaceted expression of political consciousness—mediated by institutional design and everyday experience—offers a more nuanced understanding of how citizens in transitional democracies navigate complex political environments.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DK: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The writing of this manuscript and research was supported by Universitas Pajdadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdullah, I., Afriadi, D., Yusuf, M., Susanto, M., and Fawaid, A. (2025). The visual representation in the 2024 Indonesian presidential campaign. revVISUAL 17, 133–145. doi: 10.62161/revvisual.v17.5273

Abrams, D. (2001). “Social identity, Psychology of” in International encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. eds. N. J. Smelser and P. B. Baltes (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Pergamon), 14306–14309.

Agustino, L. (2007). On Political Science: An Explanation of Understanding Political Science. Yogyakarta: Graha Ilmu.

Aspinall, E., and Berenschot, W. (2019). Democracy for sale: Elections, clientelism, and the state in Indonesia. Cornell University Press.

Becker, R. (2023). Voting behavior as social action: habits, norms, values, and rationality in electoral participation. Ration. Soc. 35, 81–109. doi: 10.1177/10434631221142733

Belt, T. L. (2007). How voters decide: information processing during election campaigns – by Richard R. Lau and David P. Redlawsk. Polit. Psychol. 28, 641–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2007.00596.x

Berg, A., and Ternullo, S. (2025). Toward a qualitative study of the American voter. Perspect. Polit., 1–17. doi: 10.1017/S1537592724002718

Bianco, W. T. (1984). Strategic decisions on candidacy in U. S. Congressional districts. Legis. Stud. Q. 9, 351–364. doi: 10.2307/439396

Bigby, C. (2022). “Programs and practices to support community participation of people with intellectual disabilities” in Handbook of social inclusion: Research and practices in health and social sciences ed. P. Liamputtong (Springer International Publishing), 695–727.

Chalik, A. (2011). Nahdlatul ulama dan geopolitik: perubahan dan kesinambungan. Surabaya, Indonesia: Impulse.

Colombo, C., and Steenbergen, M. R. (2020). Heuristics and biases in political decision making. United Kingdom, England: Oxford University Press.

Converse, P. E., Key, V. O., and Cummings, M. C. (1966). Review of the responsible electorate: rationality in presidential voting, 1936-1960. Polit. Sci. Q. 81, 628–633. doi: 10.2307/2146909

Cox, S., Kadlubsky, A., Svarverud, E., Adams, J., Baraas, R. C., and Bernabe, R. D. L. C. (2025). A scoping review of the ethics frameworks describing issues related to the use of extended reality. Open Res. Eur. 4:Article 74. doi: 10.12688/openreseurope.17283.2

Cristofaro, M., Giardino, P. L., Malizia, A. P., and Mastrogiorgio, A. (2022). Affect and cognition in managerial decision making: a systematic literature review of neuroscience evidence. Front. Psychol. 13:762993. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.762993

Dede Sri Kartini, D., Pratikno, M., and Kuskridho Ambardi, M. A. (2010). Proses Pengambilan Keputusan Memilih Pada Pemilihan Bupati/Wakil Bupati Tahun 2010 (Keputusan Heuristik Pada Pemilih di Kecamatan Cicalengka Kabupaten Bandung). Yogyakarta, Indonesia: UGM.

Dong, W. (2022). The cultural politics of affect and emotion. Berlin, Germany: Verlag.doi: 10.14361/9783839462843

Duverger, M. (1956). Political Parties, Their Organisation and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen and Co.

Evans, C., and Lewis, J. (2018). Analysing semi-structured interviews using thematic analysis: Exploring voluntary civic participation among adults. New York, United States: SAGE Publications, Ltd.

Falasca, K., and Grandien, C. (2017). Where you lead we will follow: a longitudinal study of strategic political communication in election campaigning. J. Public Aff. 17:e1625. doi: 10.1002/pa.1625

Fauzan, I. (2022). Voter behaviour and the campaign pattern of candidates during pandemics in regional head election in Medan City, North Sumatra [campaign; election; communication tools; pandemic; media campaign]. Politika 13:16. doi: 10.14710/politika.13.2.2022.305-320

Ferdian, F., Asrinaldi, A., and Syahrizal, S. (2019). Perilaku Memilih Masyarakat, Malpraktik Pemilu Dan Pelanggaran Pemilu. NUSANTARA: Jurnal Ilmu Pengetahuan Sosial 6, 20–31. doi: 10.31604/jips.v6i1.2019.20-31

Fitzpatrick, J., and von Nostitz, F. C. (2024). Reaching the voters: parties’ use of Google ads in the 2021 German federal election. Media Commun. 12:8543. doi: 10.17645/mac.8543

Fournier, P., Blais, A., Nadeau, R., Gidengil, E., and Nevitte, N. (2003). Issue importance and performance voting. Polit. Behav. 25, 51–67. doi: 10.1023/A:1022952311518

Gallhofer, I. N., and Saris, W. E. (1988). “A coding procedure for empirical research of political decision-making” in Sociometric research: Volume 1 data collection and scaling. eds. W. E. Saris and I. N. Gallhofer (New York, United States: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 51–68.

Garvin, D. A. (2003). What you don't know about making decisions. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 31:33. doi: 10.1109/emr.2003.1207056

Golder, M. (2006). Presidential coattails and legislative fragmentation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 34–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00168.x

Guntermann, E., and Lachat, R. (2023). Policy preferences influence vote choice when a new party emerges: evidence from the 2017 French presidential election. Polit. Stud. 71, 795–814. doi: 10.1177/00323217211046329

Halimatusa'diyah, I., and Jannah, A. N. (2025). Understanding hidden layers in political participation: women's representation in Indonesia's election management bodies. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 112:Article 103141. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2025.103141

Highton, B. (2010). The contextual causes of issue and party voting in American presidential elections. Polit. Behav. 32, 453–471. doi: 10.1007/s11109-009-9104-2

Hossain Faruk, M. J., Alam, F., Islam, M., and Rahman, A. (2024). Transforming online voting: a novel system utilizing blockchain and biometric verification for enhanced security, privacy, and transparency. Clust. Comput. 27, 4015–4034. doi: 10.1007/s10586-023-04261-x

Huddy, L., Sears, D. O., Levy, J. S., and Jerit, J. (2023). The Oxford handbook of political psychology, third edition. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Intyaswati, D., Maryani, E., Sugiana, D., and Venus, A. (2021). Using media for voting decision among first-time voter college students in West Java, Indonesia. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 10, 327–339. doi: 10.36941/ajis-2021-0028

Ionescu, L. (2018). Political power, local government, and firm performance: evidence from the current anti-corruption enforcement in China. J. Self-Govern. Manag. Econ. 6, 119–124. doi: 10.22381/JSME6220185

Kartini, D. S. (2017). Demokrasi dan Pengawas Pemilu. J. Gov. 2, 146–162. doi: 10.31506/jog.v2i2.2671

Komarudin, U., Handoko, W., and Hussain, F. (2025). Money politics and voter behavior: factors behind incumbent defeat in Subang regency’s 2024 regional election. Jurnal Hukum Unissula 41, 216–235. doi: 10.26532/jh.v41i2.44163

Lau, R. R., and Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). An Experimental Study of Information Search, Memory, and Decision Making During a Political Campaign. J. H. Kuklinski (). Citizens and politics: Perspectives from political Psychology (136–159). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Lau, R. R., and Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). How voters decide: Information processing in election campaigns. ed. D. P. Redlawsk. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Lilleker, D. G., Jackson, D., Kalsnes, B., Mellado, C., Trevisan, F., and Veneti, A. (2024). The routledge handbook of political campaigning. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis.

Lima, J., Santana, M., Correa, A., and Brito, K. (2023). “The use and impact of TikTok” in the 2022 Brazilian Presidential Election Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Gda?sk, Poland.

Liu, H., Zhang, H., Xu, Y., and Xue, Y. (2024). Decision-making mechanism of farmers in land transfer processes based on sustainable livelihood analysis framework: a study in rural China. Land 13:640. doi: 10.3390/land13050640

Lubis, M., Kartiwi, M., and Zulhuda, S. (2014). “Decision to casting a vote: an ordinal regression statistical analysis.” in 2014 the 5th international conference on information and communication Technology for the Muslim World, ICT4M 2014.

Marcinkiewicz, K. (2018). The economy or an urban–rural divide? Explaining spatial patterns of voting behaviour in Poland. East. Eur. Polit. Soc. 32, 693–719. doi: 10.1177/0888325417739955

Mende, J., and Müller, T. (2023). Publics in global politics: a framing paper. Polit. Gov. 11, 91–97. doi: 10.17645/pag.v11i3.7417

Muhammad, R., Syam, R., Yahya, I., and Asis, P. H. (2025). Rational choice and political imaging in mining areas: a case study of legislative elections in east Luwu. Front. Sociol. 10:1564925. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2025.1564925

Naurin, E., and Oscarsson, H. E. (2017). When and why are voters correct in their evaluations of specific government performance? Polit. Stud. 65, 860–876. doi: 10.1177/0032321716688359

Nugroho, R., and Sihotang, L. B. (2024). Analysis of the effect of work motivation and work discipline on employee performance at the North Jakarta Immigration Office. Jurnal Ekonomi, 13, 1928–1937. doi: 10.47153/jeko13.2.895

Perbawa, K. S. L. P., Hanum, W. N., and Atabekov, A. K. (2024). Industrialization of election infringement in simultaneous elections: lessons from Sweden. J. Hum. Rights Cult. Legal Syst. 4, 477–509. doi: 10.53955/jhcls.v4i2.170

Qodir, Z. (2024). Millennial generation and political communication tolerance in Indonesian election 2024. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems,

Razak, R. A., Alias, N. F., and Idris, A. Y. (2025). Qualitative insights through applied cognitive task analysis. London, England: IGI Global.

Risnanto, S., Mohd, O., Hafeizah, N., and Mardiana, N. (2023). Constructing and optimizing an evaluation model for the implementation of electronic voting: an Indonesian case study. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 10, 1401–1408. doi: 10.18280/mmep.100435

Schlinger, H. D. (1996). What’s wrong with evolutionary explanations of human behavior. Behav. Soc. Issues 6, 35–54. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v6i1.279

Simiyu, R. (2008). Contextual influences on voting decision: mapping the neighbourhood effect in a multi-ethnic rural setting in Kenya. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 90, 106–121. doi: 10.1080/03736245.2008.9725318

Sanur, S., Sahrir, S., and Putra, A. D. A. (2024). The Influence Of Income Financial Literacy, And Attitudes Towards Money On Family Financial Management. In International Conference of Business, Education, Health, and Scien-Tech (Vol. 1, pp. 2108–2117).

Subiyanto, A. E. (2020). General elections with integrity as an update of Indonesian democracy. Jurnal Konstitusi 17, 355–371. doi: 10.31078/jk1726

Sutopo, U., Basri, A. H., and Rosyidi, H. (2024). Presidential threshold in the 2024 presidential elections: implications for the benefits of democracy in Indonesia. Justicia Islamica 21, 155–178. doi: 10.21154/justicia.v21i1.7577

Suyatno, S. (2016). Pemilihan Kepala Daerah (Pilkada) dan Tantangan Demokrasi Lokal di Indonesia. Indones. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1:212. doi: 10.15294/jpi.v1i2.6586

Turska-Kawa, A. (2013). Big five personality traits model in electoral behaviour studies. Rom. J. Polit. Sci. 13, 69–105. Available online at: https://www.sar.org.ro/polsci/?p=1046

Visser, M. (1996). Voting: a behavioral analysis. Behav. Soc. Issues 6, 23–34. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v6i1.278

Wahyuni, S. N., Khanom, N. N., and Astuti, Y. (2023). K-means algorithm analysis for election cluster prediction. Int. J. Inf. Vis. 7, 1–6. doi: 10.30630/joiv.7.1.1107

Younus, M., Mutiarin, D., Abdul Manaf, H., Nurmandi, A., and Luhur Prianto, A. (2025). Conceptualizing smart citizen as smart voter and its relationships with smart election process. Discov. Glob. Soc. 3:10. doi: 10.1007/s44282-025-00148-x

Keywords: voting behavior, decision-making process, Indonesian election, political heuristics, behavioral decision theory, electoral participation

Citation: Kartini DS, Adinadya Putra MD and Zainudin A (2025) Decision-making process in voting during the 2024 election in Indonesia (A Study in Bandung Regency). Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1647672. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1647672

Edited by:

Bálint Mikola, Central European University, HungaryReviewed by:

Marno Wance, University of Pattimura, IndonesiaEvie Ariadne, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Kartini, Adinadya Putra and Zainudin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dede Sri Kartini, ZGVkZS5zcmkua2FydGluaUB1bnBhZC5hYy5pZA==

Dede Sri Kartini

Dede Sri Kartini Mohammad Desgia Adinadya Putra

Mohammad Desgia Adinadya Putra Arif Zainudin

Arif Zainudin