- Political Science, Mogadishu University, Mogadishu, Somalia

Introduction: This study examines the role of peace education in promoting social justice and sustainable peace in post-conflict societies, with a specific focus on Somalia. Although Somalia lacks a formal peace education subject within its national curriculum, themes such as peace, tolerance, reconciliation, and civic responsibility are interwoven into existing subjects like Social Studies, History, Islamic Education, and Conflict Resolution at the university level. The study draws on the 4Rs framework, Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation, to assess how education can address the root causes of conflict and social division.

Methods: The study employed a qualitative comparative case study approach, drawing on secondary data from Somalia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone to assess how different post-conflict countries have integrated peace education into their national systems.

Results: Findings indicate that while Somalia has made efforts to integrate peace-related themes into education, its approach remains fragmented and lacks a unified strategy. Key challenges include disparities in access to education, limited inclusion of marginalized voices in curriculum development, and inadequate engagement with historical grievances. By contrast, Rwanda and Sierra Leone have implemented more structured and coordinated peace education initiatives that have contributed to national reconciliation and civic rebuilding.

Discussion: The study highlights the transformative potential of peace education in post-conflict contexts when anchored in a justice-oriented framework. Somalia’s current efforts, though commendable, require stronger policy coordination, broader stakeholder participation, and comprehensive curriculum reform to fully harness the role of education in sustaining peace.

Introduction

In post-conflict societies, education emerges as an essential vehicle for healing and reconstruction, fostering social justice, and laying the foundational stones for sustainable peace. The Somali education system, marred by years of civil strife and institutional breakdown, attempts to harness the power of education as a catalyst for societal rejuvenation. While the potential for education to rebuild social fabrics is well-documented, the implementation of peace education within Somali curricula has been sluggish and inconsistent. As noted by Morales, effective peace education is fundamentally designed to equip students with the necessary knowledge and tools to foster peaceful coexistence and engage in constructive dialog, which is particularly crucial in the context of nations recovering from violent conflict (Morales, 2021).

The 4Rs framework, Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation, advanced by Pherali offers a comprehensive lens through which to examine the integration of peace education into national curricula, particularly in fragile contexts like Somalia (Pherali, 2021). Each component of the 4Rs reflects essential principles for justice and peacebuilding: Redistribution emphasizes the need for equitable access to resources, Recognition acknowledges diverse identities and experiences, Representation ensures that all voices are included within the educational narratives, and Reconciliation facilitates processes of healing and understanding among conflicting parties (Pherali, 2021). Despite the significance of these concepts, the absence of a dedicated peace education program within Somalia’s national curriculum poses a significant barrier to the actualization of these principles.

Comparatively, countries such as Rwanda and Sierra Leone exhibit more structured approaches to peace education in their post-conflict recovery efforts. These nations have integrated peace education systematically within educational frameworks, recognizing its pivotal role in fostering social justice and sustainable peace. Historically, Rwanda has transformed its education system to emphasize peace and reconciliation, effectively utilizing the lessons of the past to promote a culture of understanding among its youth (Mohamed, 2024). Similarly, Sierra Leone’s commitment to integrating peace education has shown promising results in building social cohesion and resilience against conflict re-emergence (Saikia, 2023). This disparity highlights a critical area for improvement in Somalia’s educational strategy, where the potential for peace education to heal societal wounds remains largely untapped.

Integral to the discussion on peace education in Somalia is an acknowledgment of cultural context and community involvement. Kester et al. argue that educational systems must actively engage with and incorporate local community values to cultivate an effective peace education framework (Kester et al., 2022). This engagement fosters a sense of ownership and relevance among community members, thereby becoming a crucial underpinning for enduring changes in societal attitudes toward conflict and violence. For Somalia, aligning peace education with local traditions and norms could not only enhance its acceptance but also enrich its content, making it more applicable to the realities faced by students (Chege, 2020).

Moreover, an equitable education system is fundamental for peacebuilding, as emphasized by Uddin, who suggests that addressing educational disparities is essential for fostering inclusivity and preventing societal disintegration in conflict-affected societies (Uddin, 2015). In Somalia, creating equal access to quality education for all, particularly marginalized groups, must be prioritized to address historical grievances and foster a shared national identity. Such measures, underpinned by the 4Rs framework, would not only help in addressing immediate educational inequalities but would also contribute to developing a more just society capable of sustaining peace in the long term.

Evaluating these themes through the lens of the 4Rs framework reveals substantial gaps in Somalia’s current educational approach. For instance, while there may be efforts toward representation in educational settings, the lack of curriculum that actively teaches conflict resolution and reconciliation indicates a missed opportunity to equip youth with essential skills and frameworks needed for navigating post-conflict realities. Nihayati discusses that empathy, communication skills, and the ability to analyze and resolve conflicts are basic values that peace education should impart, yet these competencies are underemphasized in the Somali context (Nihayati, 2023). The development of structured peace education initiatives that weave these skills into the curriculum could transform Somali education into a powerful tool for future generations.

The necessity of re-evaluating educational policies to incorporate comprehensive peace education is underscored by the challenges faced by youth in conflict-prone environments. Students often emerge from conflict environments carrying deep-seated trauma and societal divisions, making equitable access to peace education vital (Esmailzadeh, 2023). In this context, a dedicated peace education program that incorporates psychosocial support, as emphasized by Harber, can alleviate tensions and promote healing among fragmented communities through education (Harber, 2018).

Furthermore, insights from other post-conflict regions illustrate varying degrees of success in implementing peace education. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, an integrated approach to peace education has been largely successful, wherein students acknowledge the importance of education in fostering mutual respect and understanding among diverse ethnic groups (Mulalic, 2023). This experience serves as a potential blueprint for Somalia, encouraging the adoption of inclusive pedagogical practices that align with local values while fostering social justice and reconciliation.

It is pivotal for Somalia’s educational reforms to include broader discussions about citizenship and social responsibility, as highlighted by scholars like Amin et al. (2020). Incorporating an understanding of rights, civic duties, and peaceful cohabitation not only empowers individuals but fortifies societal structures required to maintain peace. Such initiatives can lead to an engaged citizenry capable of critically assessing societal issues and contributing positively toward national unity.

Inclusive peace curricula must also leverage technology and innovative pedagogical methods to reach and engage all segments of society effectively. As outlined by Hardiyansyah et al., integrating technology into peace education can enhance learning experiences and reach younger populations (Hardiyansyah et al., 2023). The potential for interactive learning environments can facilitate deeper engagement with peace concepts, making them more accessible and relevant to students from various backgrounds.

The aim of this study is to assess how Somalia’s educational system contributes to the promotion of social justice and sustainable peace through the lens of the 4Rs framework. Specifically, the paper seeks to explore how peace-related themes are currently integrated into the Somali curriculum, identify key gaps, and offer lessons from other post-conflict countries that have taken a more structured approach to peace education.

The purpose is to provide evidence-based insights and practical recommendations that can inform curriculum reform, policy development, and community engagement strategies aimed at strengthening Somalia’s education system as a tool for peacebuilding.

Somalia’s path toward integrating peace education into its national curriculum is fraught with challenges, but the potential for transforming its educational landscape remains vast. By utilizing the 4Rs framework, stakeholders can strategically identify areas of improvement and implement comprehensive peace education initiatives that resonate with local values and aspirations. Subsequently, effective peace education not only promises to enhance social justice and reconciliation efforts but also establishes a firmer groundwork for lasting peace in Somalia.

A literature review

Peace education is essential in equipping learners with competencies that allow them to navigate and resolve conflicts non-violently. Its multifaceted nature is underscored in literature, illustrating its role in cultivating not merely awareness of conflict resolution techniques but also empathy and ethical responsibility toward others. Lepianka describe how programs centered on conflict resolution, mediation, and restorative justice enhance individuals’ understanding of the relationship between conflict and injustice, fostering moral inclusion and developing insights necessary for forgiveness and reconciliation (Lepianka, 2022).

The urgency for implementing peace education is heightened in post-conflict areas, where educational frameworks must not only address the repercussions of violence but also facilitate the development of peaceful coexistence among diverse ethnic and cultural groups. Moreover, Irawan et al.’s exploration of Al-Ghazali’s philosophies encourages embedding peace-oriented values in educational paradigms, reinforcing harmony within institutional frameworks while respecting differences among individuals (Irawan et al., 2023).

Social justice education, as a complementary effort to peace education, seeks to promote equal opportunities and representation within educational discourse. Just as peace education addresses the mechanics of conflict, social justice education interrogates systemic barriers to equity and inclusion. This examination reveals that educational settings must emphasize a curriculum that recognizes and advocates for marginalized voices, empowering them within the narrative of learning (Rodríguez et al., 2010; Tracy-Bronson, 2024).

Furthermore, research illustrates that social justice-oriented educational systems can potentially mitigate the recurrence of violence. For instance, the integration of justice-oriented pedagogies into teacher preparation reveals that equity-focused training in teacher education leads to enhanced capabilities for addressing societal issues inherent to educational practice, thus fostering environments where social justice flourishes (Duncan, 2021).

The relationship between peace education and social justice is both symbiotic and critical. Educational reforms that prioritize social justice can significantly contribute to conflict prevention by addressing the root causes of inequalities and promoting inclusivity (Ben-Shahar, 2015; Koza et al., 2024). In their analysis, Rodríguez et al. articulate that educational programs designed with a focus on justice assumptions help cultivate future leaders equipped to confront systemic injustices while fostering peaceful interrelations (Rodríguez et al., 2010).

Research reinforces the assertion that peace education grounded in justice-oriented principles offers a sustainable path toward long-term social stability. For example, Pherali’s investigation elucidates that equitable access to quality education catalyzes peace in conflict-affected areas, reinforcing the significance of curricula tailored to address both social justice and peace education imperatives (Pherali, 2021). This nexus enhances the moral fabric of educational institutions and aligns them with broader societal objectives aimed at harmony and social cohesion.

Effectively managing conflict remains a critical dimension within both peace and social justice education. The literature indicates that various conflict resolution strategies have gained traction in educational settings, emphasizing negotiation and mediation as pivotal to fostering understanding and cooperation among students (Rinker and Jonason, 2014; Begić, 2024). High-context resolution strategies, such as collaborative problem-solving and restorative practices, engage parties in dialog, ensuring that all voices are heard, which directly enables maximizing the equity inherent in social justice frameworks (Dover, 2015).

Moreover, initiatives focusing on systemic narratives of justice through education can significantly affect students’ perceptions of conflict and their approaches toward resolution. For instance, findings from studies on conflict resolution education suggest that students trained in empathetic negotiation techniques are better equipped to handle disagreements, ultimately contributing to a culture of peace within their communities (Pugh and Ross, 2019).

The actionable frameworks for implementing peace and social justice education are vital for translating theory into practice. Various scholars propose models that emphasize culturally responsive pedagogies as a means of integrating peace education within the social justice paradigm. Such frameworks prioritize inclusive practices that recognize cultural nuances and the historical contexts of marginalized communities (Taff et al., 2024; Beachum and Gullo, 2020).

Engaging educators in these frameworks is essential. Literature indicates that when teachers receive adequate training in social justice and conflict resolution strategies, they become more effective in discussing sensitive topics around equity and diversity. Therefore, comprehensive professional development programs are crucial in empowering educators to enact justice-oriented reforms (Shultz, 2010; Nanayakkara, 2020; Tikly, 2024). Research conducted by Forde and Torrance further postulates how social justice dimensions in leadership development can significantly influence educators’ capacity to transform classrooms into spaces where peace flourishes (Forde and Torrance, 2016).

Despite the theoretical and methodological advancements in peace and social justice education, several challenges persist. Institutional resistances, coupled with inadequate training for educators, can thwart the implementation of inclusive and equitable educational practices. For instance, emergent policies reflecting conservative biases may curtail progressive educational approaches that emphasize social equity and justice (Rodríguez et al., 2024; Agosto and Karanxha, 2012; Boan et al., 2018).

Moreover, societal stigma surrounding marginalized identities continues to influence students’ engagement with educational content, perpetuating cycles of exclusion and conflict. As such, educational policymakers must grapple with the sociopolitical realities that these frameworks operate within, ensuring that educational reforms are robust yet flexible enough to navigate fluctuating cultural landscapes (Mansur et al., 2024; Masterson, 2019).

Theoretical framework

The 4Rs framework for analyzing educational practices in post-conflict societies, as posited by (Pherali, 2021), offers a comprehensive strategy to assess the multifaceted roles of education in the aftermath of conflict. In particular, this framework’s elements—Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation—are crucial in understanding how education can foster healing and unity in nations struggling with the aftermath of violence. Viewed through these lenses, the situation in Somalia can be evaluated not merely in terms of educational access but also in the broader cultural, political, and social contexts that have shaped its educational landscape.

As noted in the literature, Redistribution entails ensuring equitable access to quality education, especially in post-conflict contexts. In Somalia, various groups—including internally displaced persons (IDPs), rural communities, and marginalized clans—remain disadvantaged due to historical and ongoing systemic inequalities (Hudson, 2019). Strategies aimed at addressing these disparities should focus on enhancing resource allocation in education, as laid out by Mohamad and Nasir, who stress that educational development is pivotal for poverty alleviation in Mogadishu (Morrison and Malik, 2023). Their findings suggest that education is not just an individual right but a societal prerequisite for progress, underscoring that policies for equitable access must transcend mere enrollment figures.

Recognition, the second dimension of the 4Rs, emphasizes acknowledging and valuing cultural diversity within educational curricula. In Somalia, the integration of diverse cultural identities into the educational content can enhance social cohesion and foster a sense of belonging among different clans (Ahmed and Ali, 2024). An inclusive curriculum that resonates with various cultural narratives can enhance student engagement and promote peacebuilding. Scholars such as Ahmed and Ali underscore the significance of culturally relevant educational content as a means to mitigate conflict and promote mutual respect among diverse groups within Somali society (Iwu et al., 2024; Ahmed and Ali, 2024). This cultural recognition is key to rebuilding trust in fractured social landscapes.

Representation, which focuses on inclusive decision-making practices within education governance, is particularly salient in the context of Somalia’s complicated political landscape. The integration of stakeholder voices from all societal segments, especially marginalized groups, into policy discussions and curricular decisions is critical (Schwartz and Aden, 2017). Schwartz and Aden argue that the inclusion of diverse perspectives can significantly impact the effectiveness of educational leadership in post-conflict societies such as Somalia, highlighting that equitable governance in educational policy can strengthen community relations and foster political stability (Alawa et al., 2021).

The dimension of Reconciliation in the 4Rs framework is urgently relevant in Somalia, given its turbulent history of conflict. Education has the potential to serve as a platform for addressing past grievances and promoting healing through collective memory initiatives, dialog, and shared goals. Addressing historical injustices through education can facilitate an environment conducive to reconciliation and dialog among communities (Gele et al., 2017). The emphasis on teaching shared histories could help dismantle the cycles of mistrust and violence that have plagued Somali society, ultimately contributing to a more peaceful nation.

In exploring these dimensions within the Somali context, it becomes evident that education must not only aim to provide knowledge but also to serve as a tool for social transformation. Addressing these 4Rs in Somali education necessitates a multifaceted approach that combines socio-political engagement with educational reform. Research indicates that various Puntland and Somaliland initiatives exemplify efforts toward redistributing educational resources and addressing disparities that arise from geographic and socio-economic divides (Rage et al., 2022). However, sustained efforts are required to align educational policies with the principles of the 4Rs framework to create a more equitable and inclusive educational environment in Somalia.

Moreover, the contextual disparity among federal member states can lead to significant variations in educational outcomes. This divergence highlights the necessity for a coherent national policy that embraces the 4Rs as an overarching guideline for educational reform across different regions (Mohamed et al., 2024). Such a policy would ensure that various stakeholders, including local communities and international partners, collaborate on education issues, fostering inclusivity and shared ownership of the educational reform process.

The intersection of education and health in Somalia further illustrates the intertwined nature of these domains, especially in the quest for social equity. Poor health infrastructure and access to education are mutually reinforcing challenges, as exemplified by Morrison and Malik’s study indicating how inadequate health facilities contribute to educational challenges (Morrison and Malik, 2023). Enhancing access to both quality education and health resources within the framework of the 4Rs can lead to comprehensive improvements in individual and community well-being.

Incorporating technology into the educational sector presents another avenue for promoting equity and improving educational access. As explored in recent literature, digital resources and online learning can serve as effective tools in bridging educational gaps, especially in marginalized areas (Joshi and Koirala, 2023). However, the implementation of such digital solutions must be undertaken with careful consideration of the unique infrastructural and cultural circumstances within Somalia. The potential for education technology to empower students must be leveraged to include all communities, particularly those historically underserved.

Further, the role of civil society organizations in Somalia should not be underestimated. Civil society can significantly contribute to reconciliation efforts by facilitating dialog and encouraging collaborative efforts among various community stakeholders (Dasgupta et al., 2017). Their active involvement in educational reforms and community-building initiatives can help institutionalize the principles of the 4Rs, ensuring that marginalized voices are represented and recognized within the educational discourse and policy framework.

Therefore, while the 4Rs framework provides a robust lens for analyzing education in Somalia, it also necessitates a comprehensive engagement with broader societal issues such as health disparities, technological integration, and civil participation. Holistic education reforms must be attentive to these interconnections to promote sustainable and lasting peace as Somalia continues its journey toward recovery and national stability.

This study underlines the critical need for an integrated approach within the educational sector in Somalia, rooted deeply in the principles of the 4Rs framework. The interplay between Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation in education can no longer be viewed in isolation from the wider socio-cultural and political contexts. Emphasizing these dimensions through targeted policies, community engagement, and inclusive practices has the potential to transform the educational landscape in Somalia, ultimately contributing to the nation’s healing process and fostering a united society.

This study adopts a qualitative comparative case-study design using secondary data from 2012 to 2024. We selected peer-reviewed articles, UN/NGO reports, and official documents in English or Somali that focus on peace education in Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Somalia. Following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis (2006), The researcher independently coded each source for the four Rs, Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation—using an agreed codebook. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, and themes were then organized under the 4Rs framework. This process ensures a transparent, systematic, and reproducible analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Guest et al., 2011).

Data sources include curriculum policy documents from Somalia’s Ministry of Education, program evaluations (e.g., UNICEF PBEA), and academic literature on peace education. Thematic analysis is guided by the 4Rs framework.

This study relies exclusively on secondary data, which limits the depth and immediacy of our findings. Without primary fieldwork, such as interviews or focus groups with teachers, students, or policymakers, we cannot capture firsthand perspectives on peace-education implementation. Additionally.

Case studies: peace education in practice

Peace education in Somalia manifests through an integration of peace themes across various educational curricula, including History, Social Studies, Islamic Studies, and Civic Education. In higher education universities have introduced Conflict Resolution as a formal subject. However, challenges persist in effectively executing and exploring peace education within the curriculum.

A critical examination reveals that while peace and social justice topics are included in the curricula, their integration often remains superficial. Issues related to identity-based conflicts are frequently inadequately addressed, which can lead to a lack of deeper engagement with the historical grievances underpinning these conflicts. This shortcoming reflects broader trends observed in various educational frameworks, where peace education, although theoretically present, fails to have significant transformative effects in fostering understanding and resolving conflicts. Scholars have noted inconsistencies in delivering peace education and the need for a more robust curriculum that not only addresses conflict resolution in theory but also provides practical applications and deeper insights into the root causes of discord (Mohamed, 2024).

The integration of peace themes into Somalia’s national curriculum aims to promote universal educational access, yet inequities persist. Disparities regarding gender, geography, and socio-economic status significantly hinder equal educational opportunities. These inequities have been extensively documented, indicating that while initiatives may aim to promote inclusivity, the realization of such goals often falls short due to systemic barriers (Torres-Madroñero et al., 2021).

The representation within the curriculum warrants scrutiny, as the development process is often centralized with limited participation from community members and youth. This top-down approach can result in curricula that do not resonate with the lived realities or needs of the students. Collectively engaging various stakeholders is essential to ensure that the curriculum is contextually relevant and impactful. The lack of local community engagement in curriculum development is a concern echoed in educational systems worldwide, underscoring the importance of localization and community collaboration in peace education to foster a meaningful connection between educational content and student experiences (Vélez, 2021).

Furthermore, while themes of reconciliation, harmony, and forgiveness are incorporated into peace education curricula, there is a need for a more nuanced treatment of historical grievances. Superficial engagement with the past can inhibit students from fully understanding the complexities of present social tensions. Peace education is intended to cultivate a profound understanding among students of the mechanisms of conflict and how reparative justice can be achieved. A thorough examination of historical contexts and grievances is crucial, as initiatives aimed at reconciliation can become mere rhetoric without the substance necessary for true societal transformation (Yastibaş, 2020).

In evaluating the curriculum landscape in Somalia, there is an urgent need to enrich discussions surrounding identity and conflict. A substantive educational approach must address the narratives shaping students’ understandings of peace and conflict and facilitate open dialog that allow for the expression of multiple perspectives. Shifting toward more participatory models in curriculum development could lead to significant advancements in framing and teaching peace education, enabling students to engage meaningfully with the issues affecting their lives and societies (Torres-Madroñero et al., 2021).

Overall, while the integration of peace themes within Somalia’s educational curricula signifies a foundational commitment to fostering a culture of peace, much work remains to ensure that these efforts translate into effective, relevant, and transformative educational experiences. Engaging various stakeholders and addressing the complexities of conflict with the depth and nuance they demand will be pivotal in advancing peace education as a tool for societal healing and development (Mohamed, 2024; Vélez, 2021).

UNICEF PBEA program in Somalia

The Peacebuilding, Education and Advocacy (PBEA) program, implemented by UNICEF in Somalia between 2012 and 2016, aimed to promote peace through education in a context where access to quality education was severely restricted due to ongoing conflict and civil unrest. In this challenging landscape, the PBEA program sought to enhance community capacities by introducing peace education components, particularly targeting vulnerable groups such as conflict-affected children and internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Nyadera and Mohamed, 2020).

A primary goal of the PBEA program was to redistribute educational opportunities in a context of systemic inequalities entrenched by decades of conflict, prioritizing children from conflict-affected backgrounds, including IDPs. Educational initiatives have been linked to restoring normalcy and fostering resilience in these communities (Williams and Cummings, 2015). By providing targeted educational resources and facilities, the PBEA aimed to deliver not only academic instruction but also promote social reintegration and stability, which are critical for long-term peacebuilding efforts (Williams and Cummings, 2015).

The program emphasized the importance of inclusive identities within its school activities, designed to instill a sense of belonging and community by reflecting Somalia’s diverse cultural perspectives. Activities such as peace clubs encouraged dialog and understanding among students from different backgrounds (Ahmed, 2024). This approach aimed to restore social cohesion and cultural identity among youth, fostering an environment conducive to inclusivity amidst ongoing discord (Ahmed, 2024).

Representation was another crucial aspect of the PBEA’s framework, encouraging youth participation in school governance structures. Empowering young people to express their concerns and engage in decision-making enhances civic engagement and instills a sense of agency among students (Ahmed, 2024). Involving youth in governance is believed to foster accountability and boost their investment in peacebuilding efforts within educational institutions (Williams and Cummings, 2015; Ahmed, 2024).

The reconciliation component of the PBEA program included teacher training in conflict resolution strategies, equipping educators with skills essential for managing classroom dynamics effectively. Establishing peace clubs provided platforms for dialog and peer mediation among students, contributing to mutual respect and understanding—critical for fostering peaceful coexistence in a historically conflicted environment (Nyadera and Mohamed, 2020; Ahmed, 2024).

Furthermore, emphasizing teacher training within the PBEA program underscored the need for skilled educators capable of navigating the complexities of a post-conflict educational landscape. Trained teachers employing conflict-sensitive pedagogies play a transformative role in shaping students’ attitudes toward peace and conflict, serving as crucial guides within Somalia’s educational system (Ahmed, 2024).

In conclusion, the PBEA program implemented by UNICEF in Somalia from 2012 to 2016 represented a comprehensive approach to peace education. By addressing key elements of Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation, the program aimed to foster a more peaceful and inclusive society. Focusing on community engagement, youth empowerment, and teacher training established a framework to meet immediate educational needs while laying the groundwork for sustainable peace initiatives critical for Somalia’s long-term resilience and recovery.

Sierra Leone: post-war peace education

The role of peace education in promoting social justice and sustainable peace in post-conflict societies encompasses multiple dimensions and frameworks. In analyzing Sierra Leone’s post-war peace education, it is imperative to explore the 4Rs framework, which includes Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation. This framework provides a multidimensional approach to understanding how educational initiatives can contribute to national healing, inclusivity, and long-term stability.

In the context of Sierra Leone, the introduction of peace education was deeply rooted in the desire to address the legacies of its protracted civil war. One of the critical aspects was the redistribution of educational resources, which aimed at creating an inclusive framework for all societal groups. The policy initiatives focused on ensuring free and equitable access to education, particularly for marginalized communities affected by the civil conflict. This aligns with findings that suggest inclusive education is a foundational component in post-conflict recovery as it provides equal opportunities to regain stability and fosters a sense of belonging within a community (Tarasenko et al., 2024). Scholars emphasize that creating a barrier-free learning environment is essential for enabling access to education for all demographics, including diverse ethnicities and socio-economic statuses (Tarasenko et al., 2024).

Further, recognition played a vital role in peace education curricula developed in post-war Sierra Leone, which acknowledged and celebrated the diverse ethnic and regional identities of its population. Recognizing these identities in educational frameworks not only fosters a sense of belonging but also cultivates mutual respect among different communities (Quaynor, 2012). This recognition is crucial in countering the narratives that perpetuate division and violence in post-conflict settings. Research demonstrates that educational curricula that incorporate diverse cultural histories serve to bridge divides and promote unity (Quaynor, 2012).

Representation of youth in educational reform initiatives in Sierra Leone is another significant aspect of the 4Rs framework. The involvement of young people in shaping peace education curricula ensures that their voices are heard and their experiences are represented. This representation is essential because youth are often the most affected by conflict yet remain critical drivers of peacebuilding initiatives (Shuayb, 2015). Their engagement in educational processes facilitates a sense of agency and ownership over their futures, empowering them to challenge the cycles of violence and contribute positively to their communities (Shuayb, 2015). Studies suggest that education reforms, which incorporate youth perspectives, have proven effective in fostering civic responsibility and active citizenship (Shuayb, 2015).

Lastly, the element of reconciliation within peace education focuses on the healing of trauma and the promotion of narratives of peace. In the aftermath of conflict, individuals and communities often experience significant psychological scars; peace education thus emphasizes trauma healing as a fundamental component of the curriculum (Doran et al., 2012). Research has highlighted that educational programs incorporating trauma-sensitive approaches not only aid in emotional recovery but also create shared narratives aimed at fostering forgiveness and understanding (Doran et al., 2012). Such initiatives work toward breaking down the barriers of mistrust and animosity that have historically divided communities (Doran et al., 2012).

Together, these components of the 4Rs framework—Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation—demonstrate the multifaceted role of peace education in post-conflict societies, particularly in Sierra Leone. They not only aim to build resilience and agency among individuals but also create a blueprint for sustainable peace by addressing the foundational issues that led to conflict. The intersection of education with social justice and peacebuilding offers a paradigm in which collective healing can flourish, driven by the lived experiences and active contributions of all community members.

The ongoing process of integrating peace education into the national curriculum illustrates a broader commitment to achieving long-term peace and social justice in Sierra Leone. By fostering a culture of inclusion, respect, and shared responsibility among all societal stakeholders, the post-war educational landscape presents an opportunity to redefine the narrative of a nation once marred by violence into one of hope and collaboration. The lessons learned from Sierra Leone’s experiences may serve as a valuable guide for other post-conflict societies seeking to rebuild their educational systems in ways that promote peace and justice.

In conclusion, as we examine the implementation of the 4Rs framework in Sierra Leone’s educational reforms, it is evident that peace education is a critical tool for achieving sustainable social justice and lasting peace in post-conflict contexts. This framework not only addresses immediate educational challenges but also lays the groundwork for a more inclusive and cohesive society capable of overcoming the entrenched divisions of the past.

Rwanda: peace and unity education

The integration of peace and unity education into Rwanda’s national curriculum following the 1994 genocide serves as a transformative approach aimed at fostering social cohesion and national healing. This curriculum is structured around several core components of the 4Rs framework: Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation. Through this lens, it becomes evident how peace education not only addresses the immediate aftermath of conflict but also lays the groundwork for a more inclusive and peaceful society.

Redistribution in the Rwandan context primarily refers to the commitment to providing universal access to civic education. Following the genocide, Rwanda’s government recognized the importance of education in building a unified nation. Ensuring equitable access to education is instrumental in breaking down the discriminatory practices that fueled ethnic divisions before the genocide (Buhigiro et al., 2024). For instance, the provision of universal civic education facilitates the dissemination of values and norms conducive to social harmony and understanding. The Rwandan government has aimed to eliminate barriers that previously restricted educational access, thus prioritizing civic education as a tool for rebuilding trust and promoting peace (Dickson, 2023).

Recognition within the peace and unity education framework emphasizes the shift from ethnic identity to a collective national identity. The deliberate promotion of national identity over ethnic divisions plays a significant role in the reconciliation process in Rwanda (Buhigiro et al., 2024). Educational curricula have been redesigned to highlight stories of unity and cooperation rather than reinforce ethnic distinctions. This shift fosters a sense of shared identity among Rwandans, encouraging students to view themselves as members of a single nation rather than representatives of distinct ethnic groups (Hilker, 2011). Research indicates that educational strategies emphasizing national identity help nurture harmonious relations across formerly divided communities (Buhigiro et al., 2024).

The element of representation is also central in peace and unity education, specifically through the incorporation of civic participation within educational frameworks. Engaging individuals, particularly the youth, in discussions about governance and civic responsibilities promotes a culture of active citizenship (Buhigiro et al., 2024). This involvement ensures that diverse voices contribute to discussions surrounding national identity and community rebuilding. It is crucial that youth learn about their rights and responsibilities while also contributing to the content of the civic education curriculum, thereby reinforcing their sense of belonging and participation (Buhigiro et al., 2024).

Equally important is the reconciliation aspect of the curriculum, aligned with national reconciliation efforts. Rwanda’s peace education specifically emphasizes healing and understanding among citizens who experienced the atrocities of the genocide. The curriculum incorporates trauma-informed approaches, educating students about the past while facilitating dialog on forgiveness and healing (Buhigiro et al., 2024). Moreover, peace education curricula often include cooperative learning activities, discussions about historical injustices, and shared narratives of resilience, essential for fostering forgiveness and communal healing (Dickson, 2023). By framing reconciliation as a collective responsibility within the educational narrative, Rwanda’s educational policies aim to address the psychological aftermath of the genocide and facilitate social cohesion.

Furthermore, the teaching of peace and unity within the Rwandan curriculum extends beyond traditional educational methods. The inclusion of experiential learning opportunities allows students to engage in community service and collaborative projects that address current societal issues, further embedding the values of unity and reconciliation into their daily lives (Buhigiro et al., 2024). This approach enriches the educational experience and provides practical avenues for students to contribute positively to societal rebuilding, reinforcing the tenets of peace and reconciliation in their communities.

In conclusion, Rwanda’s commitment to embedding peace and unity education into its national curriculum exemplifies the efficacy of the 4Rs framework in post-conflict societies. The strategic focus on the redistribution of educational resources, recognition of a unified national identity, representation of diverse youth voices, and alignment of educational content with reconciliation initiatives presents a holistic approach to building sustainable peace. As Rwanda continues to heal from the scars of its past, such educational reforms are vital for fostering a culture of peace, understanding, and coexistence, thus ensuring that future generations are equipped to uphold these values in a diverse society.

Drivers of divergence

A comparative analysis of Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Somalia reveals three interlocking factors, political centralization, cultural mobilization, and resource capacity, that explain why each country’s peace-education trajectory diverges so markedly.

Rwanda’s post-genocide government exercised strong, centralized control over curriculum development, embedding reconciliation themes uniformly across all subjects. This top-down approach, reinforced by Gacaca court narratives, ensured that peace education formed part of a coherent national strategy (Hilker, 2011; Buhigiro et al., 2024). In Sierra Leone, decentralization after the civil war delegated substantial authority to district education offices and local NGOs, enabling more inclusive, but regionally variable, programs designed in collaboration with community peace-clubs (Quaynor, 2012; Hardiyansyah et al., 2023). Somalia’s fragile federal structure and enduring clan-based power dynamics have precluded a unified curriculum, producing multiple, uncoordinated initiatives (Jama, 2025; Mohamed, 2024).

In Rwanda, a deliberate shift from ethnic to national identity through education fostered collective memory and unity, with curricula emphasizing shared stories of resilience (Buhigiro et al., 2024). Sierra Leone’s peace-clubs, often led by youth and women’s groups, leveraged indigenous dialog traditions to build local ownership of peace-education content (Doran et al., 2012). By contrast, Somalia’s strong clan loyalties and absence of formal civic-education platforms have hindered any single narrative from gaining traction (Mohamed, 2024).

Substantial donor investment in Rwanda supported nationwide teacher training, high-quality materials, and robust monitoring systems, which helped scale a unified program efficiently. Sierra Leone relied on a patchwork of NGO projects that achieved notable local successes but struggled with nationwide coverage (Williams and Cummings, 2015). In Somalia, chronic underfunding and weak institutional coordination have limited both depth and breadth of peace-education efforts, leaving programs under-resourced and unevenly implemented (Aden et al., 2023; Abdi and Madut, 2019).

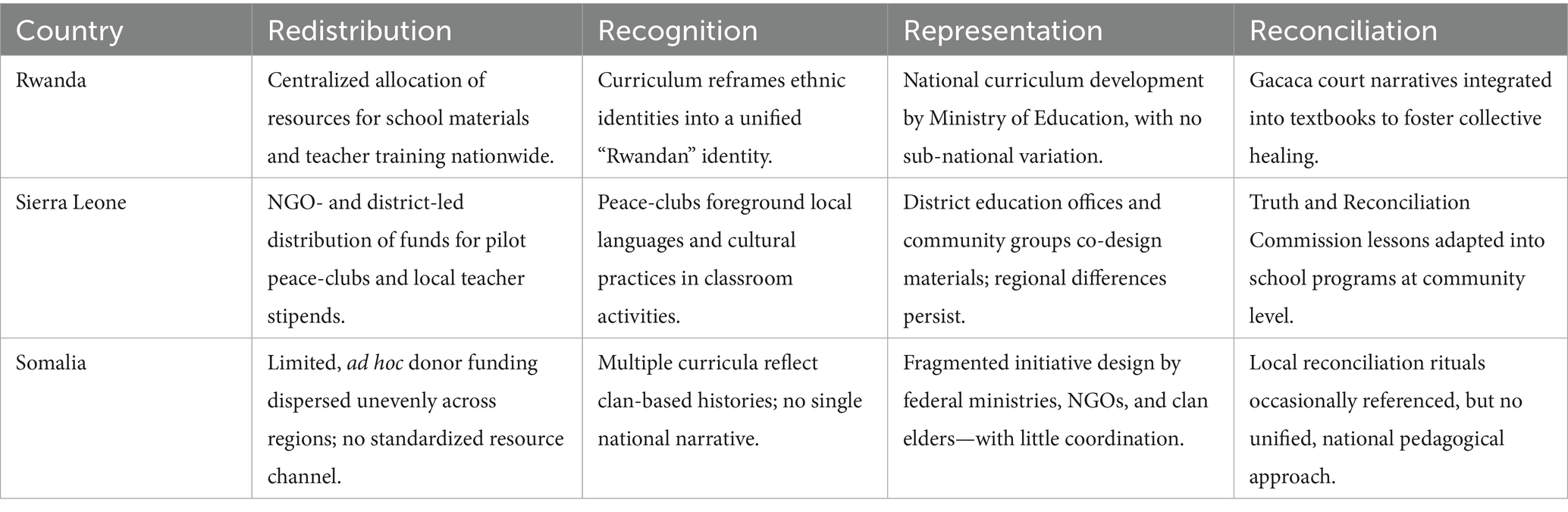

By examining how centralized policymaking, grassroots engagement, and funding streams interact in each context, we can see why Rwanda’s approach appears highly unified, Sierra Leone’s broadly inclusive, and Somalia’s largely fragmented, each pattern reflecting how the four Rs (Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation) are enabled or constrained in post-conflict education systems (Table 1). Table 1 summarizes the comparative application of the 4Rs framework across Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Somalia, highlighting the key differences in redistribution, recognition, representation, and reconciliation within their peace education systems.

Discussion

Somalia’s current approach to peace education is both significant yet markedly fractured, especially when compared to countries like Rwanda and Sierra Leone that have established formal peace education policies and frameworks. Unlike these nations, Somalia lacks a coherent and centralized strategy dedicated to educating its students about peace and conflict resolution. However, the Somali educational curriculum does incorporate themes related to peace within existing subjects, notably through the introduction of Conflict Resolution in higher education (Jama, 2025). Despite these strengths, the absence of a unified peace education strategy contributes to a fragmented approach that may inhibit the holistic development of peace-related competencies among students.

The characteristics of Somalia’s peace education landscape reveal both opportunities and challenges. One of the strengths is the recognition of peace values embedded within various subjects, which may provide a foundation from which to build a more targeted peace education initiative (Mohamed, 2024). Furthermore, the introduction of Conflict Resolution as a component of higher education is a stepping stone toward more comprehensive peace education. However, this effort lacks coordination with earlier educational stages, which dilutes its potential impact (Mohamed, 2024). The existing fragmentation can be understood through the comparative lens provided by countries that have successfully embedded peace and justice into their national educational policies, such as Rwanda, where political commitment to peace education has visibly reduced societal tensions post-genocide (Torres-Madroñero et al., 2021).

The key themes that emerge from the comparative analysis with Rwanda and Sierra Leone include the importance of political commitment, which has played a vital role in shaping educational curriculums focused on peace, as observed in Rwanda’s transitional justice and reconciliation efforts (Torres-Madroñero et al., 2021). Similarly, in Sierra Leone, the state’s investment in educational reforms aimed at embedding a culture of peace has facilitated the long-term social reconstitution necessary for healing after conflict (Hardiyansyah et al., 2023). For Somalia, an essential opportunity exists to develop a unified peace education framework that could serve to train teachers and engage communities effectively in curricular reform (Mohamed, 2024). The lack of such engagement with community stakeholders means that the educational interventions may not fully resonate with the socio-cultural realities in Somalia, weakening their effectiveness (Mohamed, 2024).

Moreover, Somali education systems could benefit from the experiences of civil society in other post-conflict nations, where grassroots involvement has proven critical in shaping policies that reflect the needs and aspirations of communities (Abdi and Madut, 2019). Given that Somalia has a history of civil turmoil and societal fragmentation, it is crucial that educational reforms involve local communities to foster a sense of ownership (Abdi and Madut, 2019). Such participatory approaches have been vital in peace education contexts, as evidenced in various international settings where community voices have shaped effective curriculum reforms for peace (Adem et al., 2024).

Part of building this grassroots engagement involves addressing the existing barriers to quality education in Somalia, including the need for adequate teacher training that focuses on peacebuilding strategies (Aden et al., 2023). A lack of trained educators inhibits the integration of peace education into existing curricula, which otherwise has the potential to promote peaceful coexistence among students (McGregor, 2011). Training educators not only provides them with the necessary pedagogical skills but also aligns classroom practices with overall peacebuilding goals (Jamshaid et al., 2024). This aligns with research findings that emphasize the transformative role of adequately trained teacher educators in shaping future generations’ attitudes toward peace (Jamshaid et al., 2024).

Additionally, developing a clear policy framework for peace education in Somalia would require a multi-stakeholder approach involving partners from government, non-governmental organizations, and community leaders (Çinar et al., 2024). Stakeholder engagement ensures that peace education policies are culturally relevant and address the specific needs of Somali society (Ibrahim et al., 2024). Long-term investments in education for peace, akin to approaches taken in El Salvador and Colombia post-conflict—where comprehensive educational policies have emerged as key drivers for societal peace—illustrate the potential impact of strategic governmental planning and community collaboration (Khairuddin et al., 2023).

An effective peace education strategy in Somalia must also consider the socio-political context of the region, including the historical factors contributing to ongoing conflict (Bickmore, 2010). The entrenched social divides and historical grievances necessitate a tailored curriculum that can address the unique peacebuilding challenges faced on the ground. This might take the form of collaborative educational initiatives with neighboring regions or similarly affected nations to facilitate reciprocal learning and peacebuilding efficacy (Lewis and Winn, 2018).

In conclusion, while Somalia has initiated some meaningful elements of peace education within its educational framework, a substantive shift toward a coordinated, comprehensive peace education strategy is urgently required. By drawing from the successful experiences of other nation-states and involving local communities in the designing and implementing of educational reforms, Somalia has the opportunity to foster a resilient culture of peace. Transformative educational policies can serve not merely as instruments for conflict resolution, but as foundational elements for holistic societal development and lasting peace.

Conclusion

This study explored the role of peace education in promoting social justice and sustainable peace in post-conflict societies, with a specific focus on Somalia. Grounded in the 4Rs framework—Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation—the analysis examined how elements of peace education are integrated into Somalia’s national curriculum and broader educational practices. Despite the absence of a formal, standalone peace education subject, the study found that themes of peace and justice are partially embedded in subjects such as Social Studies, History, Islamic Education, and at the university level in Conflict Resolution courses. These thematic inclusions reflect an acknowledgment among Somali educators and policymakers of the importance of education in shaping peaceful coexistence and civic responsibility.

However, the study also revealed significant limitations in the Somali education system’s approach to peace education. The integration of peace themes is fragmented and lacks a unified national strategy or curriculum framework. Disparities in access to quality education persist, particularly among marginalized groups, including internally displaced persons and rural communities. Additionally, the curriculum does not comprehensively address past violence, identity-based tensions, or the historical roots of conflict, limiting its potential to promote deep reconciliation. The centralized and top-down nature of curriculum development also restricts representation and local ownership in educational reform processes.

Comparative insights from Rwanda and Sierra Leone demonstrate how post-conflict countries have systematically embedded peace education into national curricula to support reconciliation, civic engagement, and national healing. These cases provide valuable lessons for Somalia, particularly the importance of integrating peace education at multiple levels of the education system, from policy and curriculum to teacher training and community engagement. Therefore, the study concludes that while Somalia has made commendable strides in incorporating peace-related concepts into education, there remains a critical need for a more coherent, inclusive, and context-sensitive peace education framework to contribute meaningfully to sustainable peace and social justice.

Recommendations

Building on our analysis of the 4Rs framework and proven models from Sierra Leone, we recommend that the Federal Ministry of Education, Culture, and Higher Education convene a national curriculum workshop that brings together regional education directors, teachers’ unions, parents, clan elders, youth representatives, civil-society organizations, and diaspora scholars. In this workshop, participants will co-draft a peace-education policy anchored in Redistribution, Recognition, Representation, and Reconciliation. The workshop should produce clearly defined learning outcomes for each “R,” model lesson plans, and a detailed implementation roadmap that specifies stakeholder roles, resource requirements, and milestones for piloting and scale-up. To overcome logistical hurdles—such as venue coordination and ensuring participation from remote regions—the ministry can partner with established NGOs for local facilitation and offer virtual attendance options.

Following the workshop, the ministry should pilot a master-trainer program to certify a cohort of fifty educators drawn from university teacher-training programs, regional education offices, and partner NGOs. This intensive training will cover conflict-sensitive pedagogy, practical methods for embedding the four Rs into everyday lessons, and techniques for fostering inclusive classroom dialog. Trainers will be evaluated through a combination of pre- and post-training assessments, peer observations, and reflective practice sessions, with feedback loops built into the program to refine materials and delivery. In parallel, regional offices and NGOs should launch community peace-clubs—each led by youth and women facilitators—using seed grants and standardized facilitator guides to run participatory workshops on storytelling, conflict mapping, and collaborative problem-solving. These clubs will serve as living laboratories for testing curriculum components in local contexts, and their lessons learned will feed back into curriculum revisions. Finally, the ministry should develop a web-based Monitoring & Learning Platform to collect real-time data on curriculum uptake, trainer performance, and community-club activities. This platform will feature user-friendly dashboards displaying key indicators—such as number of schools adopting revised lesson plans, improvement in trainer competency scores, and community-club retention rates—and support data-driven decision-making through periodic analytical reports and stakeholder review sessions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdi, F., and Madut, K. (2019). How can civil society support reconciliations and civil engagement in Somalia? Human Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Human Geogr. 13, 139–151. doi: 10.5719/hgeo.2019.132.2

Adem, R., Nor, H., Fuje, M., Mohamed, A., Alfvén, T., Wanyenze, R., et al. (2024). Linkages between the sustainable development goals and health in Somalia. BMC Public Health 24:904. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18319-x

Aden, M., Majani, F., Aden, J., Bile, K., Lundmark, B., and Wall, S. (2023). Empowering vulnerable Somali girls and women - a narrative on the role of education for health and development. Somali Health Action J 3:413. doi: 10.36368/shaj.v3i1.413

Agosto, V., and Karanxha, Z. (2012). Searching for a needle in a haystack: indications of social justice among aspiring leaders. J. Sch Leadersh. 22, 819–852. doi: 10.1177/105268461202200501

Ahmed, A. (2024). Youth participation in peacebuilding in Somalia: challenges and opportunities. MJHIU 2, 126–151. doi: 10.59336/e9b1z095

Ahmed, H., and Ali, D. (2024). Prevalence and determinants of household access to improved latrine utilization in Somalia: health demographic survey (SHDS) 2020. Environ. Health Insights 18:4148. doi: 10.1177/11786302241284148

Alawa, J., Al-Ali, S., Walz, L., Wiles, E., Harle, N., Awale, M., et al. (2021). Knowledge and perceptions of covid-19, prevalence of pre-existing conditions and access to essential resources in Somali idp camps: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 11:e044411. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044411

Amin, S., Malik, S., and Jumani, N. (2020). E-14 evaluation of Islamic studies textbook with respect to peace education at higher secondary school level in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. Al-Aijaz Res. J. Islamic Stud. Human. 4, 154–160. doi: 10.53575/e14.v4.01.154-160

Beachum, F., and Gullo, G. (2020). “School leadership: implicit bias and social justice” in Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 429–454. Available at: https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/978-3-319-74078-2_66-1

Begić, A. (2024). Ethnic conflict resolution in post-conflict societies in Bosnia. J. Conflict Manage. 4, 49–51. doi: 10.47604/jcm.2626

Ben-Shahar, T. (2015). Distributive justice in education and conflicting interests: not (remotely) as bad as you think. J. Philos. Educ. 49, 491–509. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.12122

Bickmore, K. (2010). Policies and programming for safer schools: are “anti-bullying” approaches impeding education for peacebuilding? Educ. Policy 25, 648–687. doi: 10.1177/0895904810374849

Boan, D., Andrews, B., Sanders, K., Martinson, D., Loewer, E., and Aten, J. (2018). A qualitative study of an indigenous faith-based distributive justice program in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. Christ. J. Glob. Health 5, 3–20. doi: 10.15566/cjgh.v5i2.215

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buhigiro, J., Sibomana, E., Ngabonziza, J., Mukingambeho, D., and Ntawiha, P. (2024). Peace and values education as a cross-cutting issue in Rwandan schools: teachers and classroom-based perspective. Afr. J. Empir. Res. 5, 13–23. doi: 10.51867/ajernet.5.1.7

Chege, J. (2020). African women’s journey towards gender equality and social transformation. RJIBM 2, 11–21. doi: 10.61426/business.v2i1.10

Çinar, H., Boztaş, A., and Türkmen, C. (2024). Evaluating Türkiye’s influence in the Somali peace process: positive or negative peace? Güvenlik Stratejileri Dergisi 20, 397–412. doi: 10.17752/guvenlikstrtj.1515501

Dasgupta, P., Youl, P., Pyke, C., Aitken, J., and Baade, P. (2017). Sentinel node biopsy for early breast cancer in Queensland, Australia, during 2008–2012. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 88, E400–E405. doi: 10.1111/ans.14047

Dickson, B. (2023). Reconstruction and resilience in rwandan education programming: a news media review. J. Peacebuild. Dev. 18, 177–194. doi: 10.1177/15423166231179235

Doran, J., Kalayjian, A., Toussaint, L., and DeMucci, J. (2012). The relationship between trauma and forgiveness in post-conflict Sierra Leone. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 4, 614–623. doi: 10.1037/a0025470

Dover, A. (2015). Teaching for social justice and the common core. J. Adolesc. Adult. Lit. 59, 517–527. doi: 10.1002/jaal.488

Duncan, K. (2021). “They act like they went to hell!”: black teachers, racial justice, and teacher education. J. Multicult. Educ. 15, 201–212. doi: 10.1108/jme-10-2020-0104

Esmailzadeh, Y. (2023). The role of education in promoting peace and countering terrorism. Am. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Innov. 5, 38–45. doi: 10.37547/tajssei/volume05issue04-06

Forde, C., and Torrance, D. (2016). Social justice and leadership development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 43, 106–120. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2015.1131733

Gele, A., Ahmed, M., Kour, P., Moallim, S., Salad, A., and Kumar, B. (2017). Beneficiaries of conflict: a qualitative study of people’s trust in the private health care system in Mogadishu, Somalia. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy 10, 127–135. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.s136170

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E. (2011) Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications, Incorporated, Thousand Oaks.

Harber, C. (2018). Building back better? Peace education in post-conflict Africa. Asian J. Peacebuild. 6, 7–27. doi: 10.18588/201805.00a045

Hardiyansyah, M., Darma, A., and Nugraha, M. (2023). Peace education in history learning at man Medan. East Asian J. Multidiscip. Res. 2, 1289–1298. doi: 10.55927/eajmr.v2i3.3619

Hilker, L. (2011). The role of education in driving conflict and building peace: the case of Rwanda. Prospects 41, 267–282. doi: 10.1007/s11125-011-9193-7

Hudson, B. (2019). Epistemic quality for equitable access to quality education in school mathematics. J. Curric. Stud. 51, 437–456. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2019.1618917

Ibrahim, M., Malik, M. R. R., Noor, Z., Ndithia, J., and Salad, A. (2024). Mental health and psychosocial support in the context of peacebuilding: lessons learned from Somalia [Preprint]. Res Sq. 1–13. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4685327/v1

Irawan, A., Solehuddin, M., Ilfiandra, I., and Yulindrasari, H. (2023). Building a culture of peace in education: an exploration of al-ghazali's thoughts on inner and social peace. Southeast Asian J. Islamic Educ. 5, 221–230. doi: 10.21093/sajie.v5i2.6346

Iwu, E., Elnakib, S., Abdullahi, H., Abimiku, R., Maina, C., Mohamed, A., et al. (2024). Rapid assessment of pre-service midwifery education in conflict settings: findings from a cross-sectional study in Nigeria and Somalia. London, UK: BioMed Central Springer Science and Business Media LLC. Available at: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-025-00977-6

Jama, A. (2025). The role of higher education in Somalia's socioeconomic development: a focus on the post-collapse era of the central government. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 8, 97–108. doi: 10.47814/ijssrr.v8i4.2570

Jamshaid, A., Akram, T., and Baber, S. (2024). Unveiling the transformative potential of teacher education in promoting peacebuilding: a phenomenological study. J. Soc. Res. Dev. 5, 74–86. doi: 10.53664/jsrd/05-01-2024-07-74-86

Joshi, B., and Koirala, P. (2023). Enhancing economics education through digital resources and online learning. Pragyaratna 5, 183–195. doi: 10.3126/pragyaratna.v5i1.59287

Kester, K., Abura, M., Sohn, C., and Rho, E. (2022). Higher education peacebuilding in conflict-affected societies: beyond the good/bad binary. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 24, 160–176. doi: 10.1108/ijced-04-2022-0027

Khairuddin, A., Idrus, F., Razak, A., and Ismail, N. (2023). Interpolating peace in the curriculum: how peace education is feasible through art among Malaysian Pre-schoolers. Am. J. Qual. Res. 7, 191–203. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/12956

Koza, M., Kokkalera, S., and Navarro, J. (2024). The promise of alternatives for youths: an analysis of restorative justice practices in the United States. Juv. Fam. Court. J. 75, 23–36. doi: 10.1111/jfcj.12268

Lepianka, D. (2022). What is just and unjust in education? Role of inter-ethnic tensions in defining justice in education through the prism of media debates. Curr. Sociol. 71, 1330–1347. doi: 10.1177/00113921221093093

Lewis, A., and Winn, N. (2018). Understanding the connections between the eu global strategy and Somali peacebuilding education needs and priorities. Global Pol. 9, 501–512. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12573

Mansur, M., Fitriani, I., and Yusuf, Y. (2024). Stakeholders in building conflict resolution networks in islamic educational institutions. Int. J. Educ. Narrat. 2:1336. doi: 10.70177/ijen.v2i5.1336

Masterson, J. (2019). “Doing the Binder”: Shifting perspectives of educational justice in an era of accountability. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Toronto, Canada.

McGregor, S. (2011). Peace through consumer education: a discussion paper. Nurture 5, 8–17. doi: 10.55951/nurture.v5i1.53

Mohamed, A. (2024). Peace education and conflict prevention in Somalia. MJHIU 2, 51–77. doi: 10.59336/vr58vq21

Mohamed, A. A., Akın, A., Mihciokur, S., Aden, M. Y., and Akil, A. I. (2024). Where and why mothers discontinue healthcare services: A qualitative study exploring the maternity continuum of care gaps in Somalia [Preprint]. Research Square. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4523035/v1

Morales, E. (2021). Peace education and Colombia’s efforts against violence: a literature review of cátedra de la Paz. Revista Latinoamericana De Estudios Educativos 51, 13–42. doi: 10.48102/rlee.2021.51.2.384

Morrison, J., and Malik, S. (2023). Population health trends and disease profile in Somalia 1990–2019, and projection to 2030: will the country achieve sustainable development goals 2 and 3? BMC Public Health 23:66. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14960-6

Mulalic, A. (2023). Students’ awareness and participation in the education for peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Intellectual. Discourse 31:1948. doi: 10.31436/id.v31i2.1948

Nanayakkara, S. (2020). Educating youth through sport: understanding Pierre de coubertin’s legacy today. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 16:95. doi: 10.19044/esj.2020.v16n39p95

Nihayati, L. (2023). 12 basic values of peace generation for the young generation in preventing social conflicts. Edunity Kajian Ilmu Sosial Dan Pendidikan 2, 612–620. doi: 10.57096/edunity.v2i5.93

Nyadera, İ., and Mohamed, M. (2020). The Somali civil war: integrating traditional and modern peacebuilding approaches. Asian J. Peacebuild. 8, 153–172. doi: 10.18588/202005.00a081

Pherali, T. (2021). Social justice, education and peacebuilding: conflict transformation in southern Thailand. Comp. J. Comparat. Int. Educ. 53, 710–727. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2021.1951666

Pugh, J., and Ross, K. (2019). Mapping the field of international peace education programs and exploring their networked impact on peacebuilding. Conflict Resolut. Quart. 37, 49–66. doi: 10.1002/crq.21256

Quaynor, L. (2012). Citizenship education in post-conflict contexts: a review of the literature. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Just. 7, 33–57. doi: 10.1177/1746197911432593

Rage, H., Jha, P., Kahin, A., Hersi, S., Mohamed, A., and Elmi, M. (2022). Causes of end stage renal disease among patients undergoing hemodialysis in Somalia: a multi-center study. Res Sq 1:1076. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2231076/v1

Rinker, J., and Jonason, C. (2014). Restorative justice as reflective practice and applied pedagogy on college campuses. J. Peace Educ. 11, 162–180. doi: 10.1080/17400201.2014.898628

Rodríguez, M., Chambers, T., González, M., and Scheurich, J. (2010). A cross-case analysis of three social justice-oriented education programs. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 5, 138–153. doi: 10.1177/194277511000500305

Rodríguez, G., Chase, S., Tanchuk, N., and Gebhart, N. (2024). “Divisive” education legislation in the Midwest: a critical epistemic policy analysis. Educ. Policy 39, 727–759. doi: 10.1177/08959048241263844

Saikia, A. (2023). Women and resistance in the conflict-affected Bodoland territorial council region of Assam. Indian J. Gend. Stud. 30, 188–208. doi: 10.1177/09715215231158127

Schwartz, L., and Aden, S. (2017). Educational leadership during times of armed conflict: Thailand’s lessons for Somalia. Int. J. Educ. 9:37. doi: 10.5296/ije.v9i4.11566

Shuayb, M. (2015). Human rights and peace education in the Lebanese civics textbooks. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 10, 135–150. doi: 10.1177/1745499914567823

Shultz, L. (2010). Conflict, dialogue and justice: exploring global citizenship education as a generative social justice project. Journal of contemporary. Issues Educ. 4:5001. doi: 10.20355/c5001p

Taff, S., Clifton, M., Smith, C., Lipsey, K., and Hoyt, C. (2024). Exploring professional theories, models, and frameworks for justice-oriented constructs: a scoping review. Cadernos Brasileiros De Terapia Ocupacional 32:3638. doi: 10.1590/2526-8910.ctoar27953638

Tarasenko, O., Lysenko, S., Tarlopov, I., Pidkaminnyi, I., and Verhun, M. (2024). Analysis of the competitiveness of higher education institutions in Ukraine in the context of recovery and development after the war. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 6:210. doi: 10.31893/multiscience.2024ss0210

Tikly, L. (2024). Realising systemic justice-oriented reform in education in postcolonial contexts. Glob. Soc. Chall. J. 3, 142–152. doi: 10.1332/27523349y2024d000000021

Torres-Madroñero, E., Botero, L., Rua, C., and Torres-Madroñero, M. (2021). Peace education in contexts of transition from armed conflict in Latin America: El Salvador, Guatemala, and Colombia. Peace Conflict J. Peace Psychol. 27, 203–211. doi: 10.1037/pac0000563

Tracy-Bronson, C. (2024). Leaders’ social and disability justice drive to cultivate inclusive schooling. Educ. Sci. 14:424. doi: 10.3390/educsci14040424

Uddin, A. (2015). Education in peace-building: the case of post-conflict Chittagong hill tracts in Bangladesh. Orient. Anthropol. Bi-Annual Int. J. Sci. Man 15, 59–76. doi: 10.1177/0972558x1501500105

Vélez, G. (2021). Learning peace: adolescent Colombians’ interpretations of and responses to peace education curriculum. Peace Conflict J. Peace Psychol. 27, 146–159. doi: 10.1037/pac0000519

Williams, J., and Cummings, W. (2015). Education from the bottom up: unicef’s education programme in Somalia. Int. Peacekeep. 22, 419–434. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2015.1059284

Keywords: peace education, social justice, post-conflict societies, sustainable peace, 4Rs framework, curriculum reform, civic engagement, Somalia

Citation: Adan MY (2025) The role of peace education in promoting social justice and sustainable peace in post-conflict societies: a 4Rs framework analysis. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1650027. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1650027

Edited by:

Titus Alexander, Democracy Matters, United KingdomReviewed by:

Geneva Blackmer, University of Bonn, GermanySiti Ikramatoun, Syiah Kuala University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Adan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohamed Yusuf Adan, bXk0c29tQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Mohamed Yusuf Adan

Mohamed Yusuf Adan