Abstract

Introduction:

The German party system has become increasingly unstable as the “politics of centrality” that was associated with the old Federal Republic has succumbed to a new “politics of fluidity”. The subsequent process of political fragmentation has seen the emergence of populist challenger parties of right and left. The article focuses on the more significant strand of right-wing populism represented by the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) but also considers the persistence of left populism in elements of the Linke and the recent breakaway Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW).

Methods:

The article uses mixed methods to explain modern German populism in comparative and historical perspective, and looking at demand and supply side factors, with a focus on party-based populism.

Results:

The article demonstrates that Germany's populist challengers have a strong impact on party competition but face significant systemic biases that limit their impact on government formation at the state level and certainly at the Federal level.

Discussion:

The article concludes that ceteris paribus the possibility of a right-wing populist government at the national level in Germany is smaller than in European democracies with more majoritarian electoral and party systems such as France. Nevertheless, the emergence of Germany's populist disruptors presents a systemic challenge, not least because of the dangers of over-reaction from Germany's political and legal establishment to the rise of the AfD in particular.

1 Introduction

Scholars argue that the cumulative impact of global capitalism (Reich, 1991; O'Brien, 1992; Ohmae, 1995), the global financial crisis (Arestis and Singh, 2010), accelerated social change (Blühdorn, 2013) and the “delayed crisis of democratic capitalism” (Streeck, 2014) have broken the ties between a self-referential political class (Crouch, 2005) and a significant proportion of the electorate. They conclude that the resulting “populist negativity against politics” (Stoker et al., 2016), combined with lower opportunity costs of party formation (Tormey and Feenstra, 2015), contributed to the emergence of new, populist parties across Europe.

Germany is no exception to this phenomenon. However, compared to some of Germany's European neighbors such as France—where the right-wing populist National Front (Front National, or FN—now the Rassemblement National or RN) emerged as a political force more than 40 years ago—the arrival of significant populist disruptors in the Federal Republic's party system is relatively recent. Nevertheless, the emergence of the right populist Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD) in particular has shaken the German, European and wider political classes (for a review of radical right and/or populist antecedents in Germany, see Havertz, 2021). Domestically, the AfD's sustained successes in the 2017, 2021 and 2025 elections have had a mixed impact so far. On the one hand, they have, first, provided further evidence of increased party system fragmentation (Lees, 2018a) and, second, led to greater levels of polarization within parliament (Lees, 2018b). On the other, while there is some evidence that the AfD's rhetoric had a role in hardening Germany's stance on, for example, border controls with Poland (Germann, 2024), other studies have argued that the SPD in particular has responded by strongly distancing itself from AfD talking points and actively avoiding salient issues such as immigration (Umansky et al., 2025). Nevertheless, taken in the round, the emergence and persistence of the AfD has been a profound shock to Germany's political class, whose modus operandi has been based on norms of consensus and cooperation.

For Germany's European neighbors, the emergence of a right-wing populist party in the economic motor and political anchor of the European Union (EU) is a cause for concern. Internationally, the AfD's strongly pacifist position on the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the interest in a “Eurasian” (read Russia- and China- dominated) security architecture amongst some quarters of the party means that its electoral performance and subsequent impact on German domestic politics are watched closely by security analysts around the world (Böller, 2024; Guerra, 2024). In a similar vein, albeit with lesser salience to date, the new left-populist Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht, or BSW)—led by the eponymous and highly charismatic former Left politician—has the (as yet unrealised) potential to disrupt the established political order from the left of the political spectrum (Mudde, 2024; Thomeczek, 2024a).

1.1 The 2025 German Federal election as an inflection point

The German Federal elections of February 22 2025 saw the existing political settlement in Germany placed under unprecedented pressure. Election results reflected the increasing volatility of a German party system that was historically known as an exemplar of stability. Once characterized by the notion of what the British political scientist Gordon Smith memorably described as the “politics of centrality” (Smith, 1986), German party politics has become significantly less stable in recent years with the emergence of the AfD in particular. This emergent “politics of fluidity” (Lees, 2023), characterized by fragmentation and polarization across the electorate, has impacted on the composition of both the Federal and in particular the state parliaments in Germany.

The 2025 Federal election saw German political parties compete for 630 seats in the Bundestag, Germany's equivalent of the US House of Representatives or UK House of Commons. This was significantly smaller than the outgoing Bundestag's 736 seats, due to highly contested reforms in seat distribution enacted in 2023 that effectively changed the taxonomical classification of the German electoral system from a “Mixed Member Proportional” system to a moderately localized “Party-List Proportional” system. Ongoing legal challenges to these reforms mean that we cannot rule out more changes in the coming years.

Regardless of its classification, Germany's electoral system gives each voter two votes, the first of which is for the constituency candidate and the second vote for candidates on party lists. Counter-intuitively, the second vote is the more significant in determining the composition of the Bundestag, as the Federal Election Commission determines the number of seats allocated to each party through the Sainte Laguë/Schepers method in proportion to the total number of second votes polled nationally. Only parties with three or more directly elected seats from first votes or five per cent or more of second votes nation-wide are eligible for entry into the Bundestag. Moreover, a controversial impact of the effective cap on the size of Bundestag and the imposition of strict proportionality determined by the party list vote is that not all of the successful candidates in constituency contests have been permitted to assume their seats in the Bundestag.

The 2025 Federal election produced a less fragmented but more polarized Bundestag than its predecessor. The “catch-all” center-right Christian Democratic Union (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschland, or CDU) and its sister party the Bavarian Christian-Social Union (Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern, or CSU) won a combined 28.5 per cent of the vote and were allocated 208 seats, up 11 on the previous Bundestag and making them the largest party group in the new parliament. The other catch-all party, the center left Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, or SPD) won 16.4 per cent and 120 seats, down 86. Of what are still generally referred to as the “smaller parties”—despite the ongoing relative decline of the CDU/CSU and particularly the SPD—the Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen) won 11.6 per cent and 85 seats, the Left (Die Linke) won 8.8 per cent and 64 seats, and the liberal Free Democrat Party (Freie Demokratische Partei, or FDP) won 4.3 per cent and therefore was awarded no seats in the new Bundestag. However, the headline result of the election was the result for the AfD, which won 20.8 per cent of the votes and 152 seats, making it the second largest party in the Bundestag. By contrast, the left populist BSW polled 4.98 per cent and narrowly missed out on representation in the new Bundestag.

It is highly likely that Germany's mainstream political class felt relieved when they learned of the BSW's failure, although the party does have representation in a number of state parliaments in the eastern states of the former East Germany. However, the AfD's continued success has significantly changed the dynamics of German party politics and means that Germany's second largest parliamentary party is profoundly anti-system and opposed to key aspects of Germany's established political-economic and geo-strategic postures. As already noted, this does not just present a set of domestic challenges for any German government that continues to exclude them through the accepted principle of the “Firewall” (Brandmauer) but also has strong externalities at the EU and international levels, given Germany's size, location, and economic power.

The most immediate impact of the AfD's success, however, was the impact of the Firewall on the coalition options available to the CDU/CSU as the largest party grouping in the Bundestag. The CDU/CSU and their Chancellor candidate Friedrich Merz ran in the 2025 election on a strongly conservative message and, if we include the vote share of the AfD as well, this means that nearly half of the German electorate voted for a strongly conservative or radical right-wing electoral offer. However, the exclusion of the AfD as a potential coalition partner meant that the key party that could help the CDU/CSU secure a majority government was the SPD. Not surprisingly, the SPD was able to negotiate a coalition agreement for the subsequent Grand Coalition government that was significantly to the left of where the plurality of German voters appeared to be located in the 2025 Federal election. The practical and normative problems associated with this outcome are obvious, in particular around notions of representative or responsible government.

This article discusses how we arrived at this point. We will look at populism in Germany in the round but, given the strength of the AfD and failure of the BSW to break through in the 2025 Federal election, there will be more emphasis on the AfD.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. First, we will examine the development of the German party system, with an emphasis on the transition from a politics of centrality to a politics of fluidity and the emergence of the AfD as a right populist challenger party. Second, the article examines demand side explanations of the rise of populist politics and then looks at how these explanations stack up in Germany compared with other European democracies such as France or the UK. We consider the evidence that the populist turn in Germany is either contingent and driven by the anger of the so-called losers of socio-economic change (Bonnetain, 2004)—what the political commentator Peggy Noonan has called the “unprotected”—or alternatively is a more embedded political phenomenon that is “a constitutive … feature of a new era” (Blühdorn and Butzlaff, 2018, p. 14). The third section moves on to the supply side of party-based populism, including Bolleyer (2013) work on the challenges of party institutionalization and older but related debates around the origin of parties (Panebianco, 1988; Duverger, 1964), the pressures they face (Harmel and Svåsand, 1993), and the political opportunity structures (Tarrow, 1998; Kitschelt, 1986) in which they operate. In particular, the article considers the extent to which the relative permissiveness (or lack of it) of the German electoral system (Magnan and Veugelers, 2005) has constrained or facilitated the emergence and consolidation of the two populist parties. Finally, the article concludes with a summary of these discussions and argues that analysis of the different structural attributes of the German party system goes a long way to explaining the relative fortunes of populist parties within Germany's new “politics of fluidity.”

2 The new “politics of fluidity” in Germany

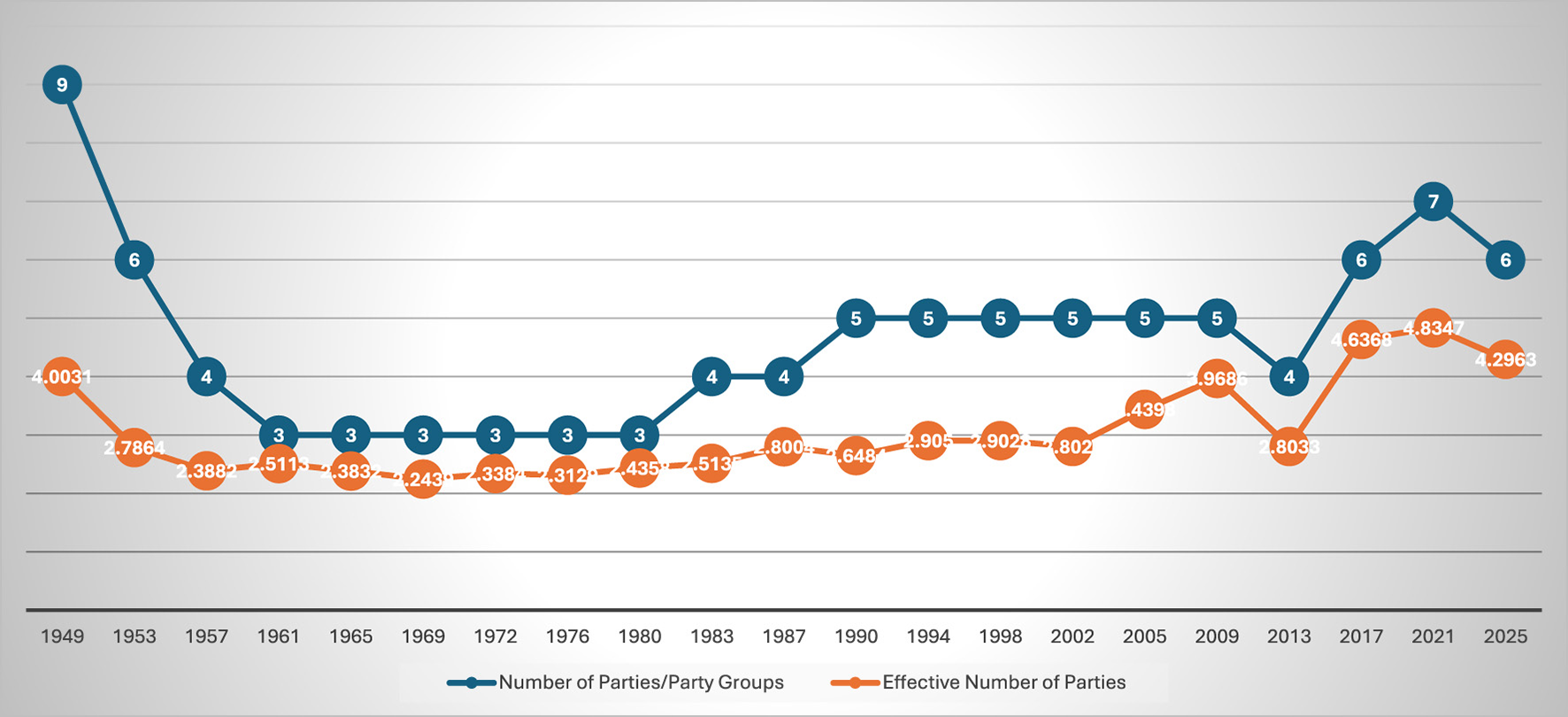

This section of the article examines how the German party system has become increasingly unstable as the politics of centrality (Smith, 1986) that was associated with the old Federal Republic has succumbed to a new politics of fluidity (Lees, 2023; Figure 1).

Figure 1

Fragmentation in the West German/German party system, 1949–2025. Source: http://www.wahlrecht.de.

The Figure plots the development of the (West) German party system from the foundation of the Federal Republic in 1949 until the present, plotting the actual number of parliamentary parties or groups and also political parties able to enter the parliament and have an impact on government formation—in other words, the “effective number” of parties (Laakso and Taagepera, 1979). The figure demonstrates three phases of the party system development.

First, we see a rapid process of consolidation over the course of three parliamentary cycles from 1949 onwards that results in the establishment of a three-party system in the Bundestag following the 1961 Federal election. This three-party system consisted of the right-of-center “catch-all” CDU/CSU, which at that time was the dominant party grouping in the Federal Republic, the left-of-center catch-all SPD, and the smaller liberal FDP. The three-party system would become one of the features of the politics of centrality and was itself sustained through the centripetal impact of many features of the old West German political settlement. This process of consolidation also coincided with the so-called “economic miracle”—an unprecedented period of economic growth in which Germany became the dominant economic power in Europe.

The second phase of party system development lasts from 1961 until 1983 and is the high point of the politics of centrality. The three-party system allowed for changes of government, and we see three configurations over the period. First, a so-called “bourgeois coalition,” made up of the CDU/CS and FDP, which lasted until 1966. Second, a “grand coalition” of CDU/CSU and SPD, from 1966 until 1969. Third, a “social-liberal” coalition from 1969 until 1982, when the FDP withdrew from the coalition in favor of a re-constitution of the bourgeois coalition with the CDU/CSU. With the FDP acting as coalition “kingmaker” for most of the period, this was a highly stable period for the German party system, despite the growing economic and social turmoil of the 1970s and early 1980s. However, it was during this period that the habit of “split ticket” voting developed, as Germany's MMP electoral system allowed voters to “lend” their second vote to the FDP party list in particular, whilst continuing to give their first vote to one of the two big catch-all parties.

The third period of party system development runs from 1983 until the present day and is marked by increasing instability, a significant increase in split ticket voting and an erosion of the share of second votes given to the two catch-all parties, and the resulting emergence of new political competitors to the left and eventually the right flanks of the German party system. This period of party system de-concentration began in the 1980s, following the entry of the ecologist Greens (Die Grünen, later Bündnis 90′/Die Grünen, or Alliance'90/Greens) into the Bundestag in 1983. However, after German unification in 1990 this process accelerated and we see the entry of the post-communist Party of Democratic Socialism (Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus or PDS, later Die Linke or the Left party) into the Bundestag after the 1990 Federal election and the AfD following the 2017 Federal election. Of course, these processes of de-concentration at the Federal level are preceded by and are often a mirror of similar processes taking place at the level of the individual states. The role of the state level in the emergence of populist politics in Germany and elsewhere is discussed later in the article.

Table 1 charts the percentage vote shares and seats gained by political parties in the Bundestag in the unified German party system since 1990. As the table demonstrates, up until the 2009 Federal election the two catch-all parties continued to win at least 70 per cent of the popular votes and thus the clear majority of seats in the Bundestag. After 2009, however, the trend is toward a more profound de-concentration of the federal party system, with the catch-all parties struggling to maintain their dominance. Thus, in the 2025 Federal election, the catch-all parties share of the votes amounted to only 45 per cent of votes/seats and the SPD's vote share of 16.4 per cent made it only the third largest party, behind the CDU/CSU (28.6 per cent) and, crucially, the AfD (20.8 per cent).

Table 1

| BSW | PDS/left party | Alliance “90/ greens” | SPD | CDU/CSU | FDP | AfD | (Other) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | −−−− | 2.4/17 | 5.0/8 | 33.5/239 | 43.8/319 | 11.0/79 | — | (4.3/00) | 100/662 |

| 1994 | −−−− | 4.4/30 | 7.3/49 | 36.4/252 | 41.4/294 | 6.9/47 | −−−− | (3.6/00) | 100/672 |

| 1998 | −−−− | 5.1/36 | 6.7/47 | 40.9/298 | 35.1/245 | 6.2/43 | −−−− | (6/00) | 100/669 |

| 2002 | −−−− | 4.0/2 | 8.6/55 | 38.5/251 | 38.5/248 | 7.4/47 | −−−− | (3/00) | 100/603 |

| 2005 | −−−− | 8.7/54 | 8.1/51 | 34.2/222 | 35.2/226 | 9.8/61 | −−−− | (4/00) | 100/614 |

| 2009 | −−−− | 11.9/76 | 10.7/68 | 23/146 | 33.8/239 | 14.6/93 | −−−− | (6/00) | 100/622 |

| 2013 | −−−− | 8.6/64 | 8.4/63 | 25.7/193 | 41.5/311 | 4.8/00 | 4.7/00 | (6.3/00) | 100/631 |

| 2017 | −−−− | 9.2/69 | 8.9/67 | 20.5/153 | 32.9/246 | 10.7/80 | 12.6/94 | (5.0/00) | 100/709 |

| 2021 | −−−− | 4.9/39 | 14.8/118 | 25.7/206 | 24.1/197 | 11.5/92 | 10.3/83 | [8.7/1(SSW)] | 100/736 |

| 2025 | 4.9/0 | 8.8/64 | 11.6/85 | 16.4/120 | 28.6/208 | 4.3/00 | 20.8/152 | [4.6/1(SSW)] | 100/630 |

Percentage vote shares/seats in the German Bundestag since 1990.

Source: http://www.wahlrecht.de.

This increasing system fragmentation has inevitably changed the dynamics of party politics within the Bundestag and, with it, the potentialities for government formation. Table 2 charts system fragmentation, voting power (VP), and coalitions with swing in the German Bundestag over the same period from 1990 to 2025. Table 2 uses the standardized Banzhaf index to measure potential voting power (McLean et al., 2005, p. 466).

Table 2

| Election | N of parties/party groups | VP BSW | VP left | VP alliance “90/greens” | VP SPD | VP CDU/CSU | VP FDP | VP AfD | VP SSW | Coalitions with swing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 5 | −−−− | 0.1667 | 0 | 0.1667 | 0.5 | 0.1667 | −−−− | −−−− | 14 |

| 1994 | 5 | −−−− | 0 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | 0.5 | 0.1667 | −−−− | −−−− | 14 |

| 1998 | 5 | −−−− | 0 | 0.1667 | 0.5 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | −−−− | −−−− | 14 |

| 2002 | 5 | −−−− | 0 | 0.3333 | 0.3333 | 0.3333 | 0 | −−−− | −−−− | 12 |

| 2005 | 5 | −−−− | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | −−−− | −−−− | 12 |

| 2009 | 5 | −−−− | 0.1667 | 0 | 0.1667 | 0.5 | 0.1667 | −−−− | −−−− | 14 |

| 2013 | 4 | −−−− | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | 0.5 | −−−− | −−−− | −−−− | 7 |

| 2017 | 6 | −−−− | 0.1071 | 0.1071 | 0.1786 | 0.3929 | 0.1071 | 0.1071 | 0 | 27 |

| 2021 | 7 (incl. SSW) | −−−− | 0.0000 | 0.1429 | 0.2857 | 0.2857 | 0.1429 | 0.1429 | 0 | 48 |

| 2025 | 6 (incl. SSW) | −−−− | 0.0769 | 0.0769 | 0.2308 | 0.3846 | −−−− | 0.2308 | 0 | 13 |

| Mean | 5.3 | −−−− | 0.0934 | 0.1410 | 0.2695 | 0.4063 | 0.1296 | 0.1603 | 0 | 17.5 |

System fragmentation, Voting Power (VP), and coalitions with swing in the German Bundestag, 1990–2025.

Source: data from http://www.wahlrecht.de; coalitions calculated using the Voting Power and Power Index Website, Antti Pajala, University of Turku, Finland: http://powerslave.val.utu.fi/.

Table 2 demonstrates a gradual accretion of voting power to the smaller parties in the Bundestag but that this process is not linear and is subject to their fluctuating fortunes in particular electoral cycles. Thus, the Left's predecessor the PDS had no voting power until 2002. Similarly, Alliance 90/the Greens' poor showing in the 2009 meant they had no voting power, and the FDP effectively had no voting power following the 2002 Federal election.

In Germany there is a strong norm in expectation of majority rule and this erratic, but relentless, diffusion of voting power has had an impact on the ability of majority governments to form. Let us look at the problem briefly in abstract terms. If we assume that the decision rule in the Bundestag is a simple majority, a party's voting power determines the extent to which they can transform a winning into a losing coalition (or vice-versa). This decisiveness is called “swing” and can be “negative” (where a party's withdrawal of support turns a winning coalition into a losing coalition) or “positive” (where a party's support turns a losing coalition into a winning coalition). Parties that cannot affect the outcome of coalition bargaining are considered “dummy” players, irrespective of the number of seats they hold. The higher the number of coalitions with swing, the more coalition options are potentially available and the more potentially unstable any winning coalition may be. After the 2025 Federal election, there were 13 coalitions with swing, which is lower than in recent years and below the historical mean since 1990.

Nevertheless, in practical terms the exclusion of the AfD from the coalition process and the distribution of voting power amongst the other parties meant that the SPD became an essential partner for the CDU/CSU in forming a majority government, despite its historically bad electoral performance. As already touched upon, this has some troubling implications for the norms of representative and responsible government.

This growing diffusion of voting power does not necessarily mean that the rise of populist politics in Germany was inevitable. As Pippa Norris points out, whilst “the effective number of electoral parties …. has generally grown in each country across Western democracies. This does not imply, however, that party systems are necessarily more polarized ideologically” (Norris, 2024, p. 546). Indeed, if we look back through the history of the Federal Republic, it is striking how much of a consensus has existed across the German political class about the broad parameters of the Federal Republic's political economy—particularly the social market economy, NATO/Atlanticism, the Franco-German alliance and the wider European integration project (Lees, 2002). This consensus survived intact until recently, despite the processes of party system fragmentation already described. There have been exceptional circumstances where political parties have had fundamental objections to certain aspects of this consensus, including the CDU right's misgivings around Ostpolitik in the early 1970s or Alliance 90/the Greens' initially anti-NATO stance in the 1980s and 1990s. However, these initial positions have shifted over time and, where aspects of political parties' ideological profile remain outside this consensus, they have been subject to a full or partial “Firewall” imposed by the other mainstream parties. For instance, the Left—which has occasionally used left populist tropes in its campaigning—has enjoyed a degree of voting power in recent Bundestags, but the party has not been seriously courted as potential coalition partners at the national level. This is despite the fact that the Left has taken part in many coalition governments in the states of eastern Germany.

It is important to note that the German party system did see populist challengers before the AfD emerged. For instance, the Party for a Rule of Law Offensive (Partei Rechtsstaatliche Offensiv or PRO, better known as the Schill Party) ran on a right populist ticket in the state of Hamburg in the early years of this century and gained 25 seats in the 2001 elections to the state parliament (Faas and Wüst, 2002). The state of Bavaria has also seen the emergence of quasi-populist challengers in the shape of the Party of Bavaria (Bayernpartei, or BP), which has enjoyed very limited electoral success over the post-war period (Mintzel, 1986) and the Bavarian Free Voters in Bavaria (Frei Wähler, or FW; Walther and Angenendt, 2018), who are currently a junior partner in the Bavarian state government.

Nevertheless, the emergence and consolidation of the AfD, presents a more profound challenge to the German political consensus—not just it has been able to establish itself as national rather than a merely regional force but more significantly because of its increasingly sharp-edged ideological stance. As is discussed later in this article, the AfD's positioning within German party politics is as an explicitly anti-system party and this is reflected in the party's 2025 election manifesto, which stressed distinctive positions on questions of national sovereignty, traditional values, and skepticism about immigration and climate policy (Alternative für Deutschland, 2025). However, the party is quite a broad church and, whilst most elements of the AfD's program would not look out of place in a manifesto produced by the RN in France or Reform in the UK, the shadow cast by Germany's troubled political past adds a level of unease and contentiousness to some of the statements and activities of leading AfD figures. Over the years, this has included attempts by prominent party members to question touchstone issues of the Federal Republic, such as Holocaust remembrance, as well as the activities of more extreme elements such as “the Wing” (Der Flugel)—a now defunct inner party grouping based in the eastern state of Thuringia that many observers believed to be unequivocally fascist in nature (Funke, 2024).

Not surprisingly, mainstream German politicians continue to shun the AfD, and the party has also attracted the attention of Germany's security services. Nevertheless, the ongoing isolation of the AfD presents three immediate problems for the Federal Republic's political settlement. First, it provides a powerful and ongoing narrative of martyrdom and grievance for the AfD's leadership: one that is tailor-made to sustain the now familiar populist trope of the “elites” shunning “the people.” Second, in an increasingly fragmented party system, the permanent exclusion of what is currently the second-largest party from the government formation process threatens to embed instability into it and undermines the notions of both responsible and representative government—as already discussed. Finally, and related to the previous point, given the ongoing socio-political divide between the states of the former “west” and “east” Germany, the permanent exclusion of the largest party in the eastern states is normatively difficult to defend.

These points are returned to in the discussion and conclusions to this article. But first we turn to the wealth of demand-side and supply-side explanations for the emergence of populism in advanced democracies and assess the extent to which these are explanatory in the German context or if the specific context of post-unification German politics makes the application of these approaches somewhat problematic.

3 Demand-side explanations

It is now orthodox to regard populist politics as being ascendant in contemporary party systems (Luengo-Cabrera, 2018) and Germany is no exception. Populism is less an ideology and more a concept or signifier, possessing “a distinctive set of formal discursive qualities” (De Cleen et al., 2018, p. 3). However, in as far as populism can be described as an ideology, it is a “thin” one (Stanley, 2008) that over-writes more substantive and grounded ideological positions of political parties—be they of the left or right of the political spectrum. The core idea of an antagonistic relationship between a righteous “people” and a morally suspect “elite” (Mudde, 2004) is a contingent and fungible one and we see this in the differential framing of populist tropes between the right populist AfD and the left populist BSW. At the conceptual level, both parties strongly identify with “the German people” as an idea, but the AfD's frame for this is strongly ethno-nationalist in nature whilst the BSW relies on a more focused class-based conception. This is consistent with Stanley's analysis touched on above. This differential framing is based on the two parties' respective right-and left-wing ideological placements and remains noticeable even when the two parties' actual policy propositions—for instance in opposing sanctions on Russian oil exports or wanting to restrict immigration into Germany—are almost identical in substantive terms.

These observations raise some interesting empirical and theoretical questions around comparisons between the AfD and the BSW and party classifications more broadly. Given that the AfD is now more than a decade old, the party's development over time has been comprehensively tracked in the academic literature (see Arzheimer, 2015; Berning, 2017; Klikauer, 2018; Atzpodien, 2022; Reuband, 2025 for instance). The BSW, by contrast, is a more recent phenomenon but has nevertheless begun to generate significant academic interest in a short period of time (see Herold and Otteni, 2025; Hoffmann, 2025; Thomeczek, 2024b,c; Jankowski, 2024; Bitschnau, 2024). There is also a less prolific but emerging literature that explicitly compares the AfD and BSW (Höhne et al., 2025; Sahin, 2025; Fratzscher, 2024; Scherer, 2024), to which we might usefully add studies that have drawn comparisons between the AFD and more populist elements of the Left, from which most of the party cadre around Sara Wagenknecht originated (Siefken, 2025; Olsen, 2018).

The literature points to some interesting empirical puzzles, the answers to which will become more apparent over time and with more applied research. These include questions around the BSW's electoral potential, the nature of its electoral base, and the potential for voter exchange between AfD, the Left and BSW voters. The evidence so far is mixed, with the BSW's failure to the scale the five per cent electoral barrier to the Bundestag being a significant setback. At the same time, although levels of support for the BSW in the western states of the Federal Republic are questionable, there is evidence of a deeper pool of potential voter support in the states of the former East Germany that could be contested with the AfD in particular and to a lesser extent the Left. These voters are described as a “migration-skeptical, politically disillusioned milieu” (Herold and Otteni, 2025, p. 1–2).

Points of difference remain between the BSW and the AfD, of course—not least the former's strong commitment to economic and social justice, compared with the AfD's broadly neo-liberal approach. However, given this concentration of support in the eastern states and a narrowed focus on key issues of immigration, political trust, and the war in Ukraine means that the two parties increasingly find themselves on the same side of key points of public concern and political debate in Germany. In such circumstances, it is perhaps no surprise that in July 2025 it was announced that the two parties' leaderships in the eastern state of Thuringia were in talks about political cooperation, with rumors that these were taking place at the Federal level as well (Kottász, 2025), whilst at the same time BSW leader Wagenknecht argued for the breaking down of the Firewall around the AfD (Rippert, 2025).

These developments are potentially destabilizing for the German party system, but they also raise some theoretical questions, not least about our classificatory schemes for political parties in increasingly fluid and fragmented party systems with often profoundly disaffected and dealigned electoral bases. For many years, there has been a lively academic debate around the “missing quadrant,” as it where, on the supply side of politics, characterized by the relative of absence of left-authoritarian parties in western Europe (Hakhverdian and Schakel, 2022; Hillen and Steiner, 2020; Lefkofridi et al., 2014). More recently, this has changed somewhat with the emergence of left-authoritarian factions in some established social democratic parties, such as “Blue Labour” in the UK Labor Party. The BSW is unusual, at least in the German context, in being a party rather than a faction and explicitly addressing this erstwhile failure of political supply in its party program. As Steiner and Hillen point out, there is significant political space for emerging competitors offering new policy mixes and some evidence that a stronger emphasis on nationalist positions can attract voters who previously supported left-leaning parties and a greater focus on social justice could attract voters from right-leaning parties (Steiner and Hillen, 2025).

These are interesting findings and raise questions about left-right classifications in particular and will doubtless be the subject of further research and debate. We return to questions of political supply later in this article. But now we move on to an examination of demand side explanations for the emergence of populism in Germany.

3.1 The demand-side: contingent vs. constitutive explanations

Demand-side explanations of populism focus on processes of socio-economic change and their impact on individuals as voters and members of the social and cultural groups that political parties mobilize. However, scholars are divided as to whether this impact is contingent on medium-term changes in economic or social conditions or whether populism is a more long-term and constitutive phenomenon. These are more than dry arguments about populism's positional relationship between immediate causal factors and the long durée (Dosse, 1994). The contingent interpretation often presents populism as a symptom of democratic crisis (Eatwell and Goodwin, 2018; Ford and Goodwin, 2014) whilst the constitutive interpretation draws upon theoretical insights (Blühdorn, 2013; Rancière, 2007) and focuses at least as much on the cultural and even the emancipatory (Laclau, 2005) dimensions of populist politics. The two approaches have different implications for how we interpret the available data and what they might tell us about the future development of populist politics in Germany.

I would argue that contingent explanations of demand-side populism are the dominant frame in the popular understanding of populist politics. These explanations often frame the global financial crisis of 2008 as a kind of event horizon (Algan et al., 2017; Thirkell-White, 2009), the consequences of which are still playing out after nearly 20 years of difficult and often damaging “austerity” policies (Blyth, 2013) across Europe.

In this account, voters are angered by the more or less explicit hollowing out of the democratic process associated with what the German political economist Streeck (2014) described as the “delayed crisis of capitalism,” going back to the neo-liberal turn of the 1970s. For 30 years or more, Western democracies failed to reconcile the demands of the financial markets with the needs of the wider economy and therefore fell short in pursuing the best interests of citizens. For Streeck, the global financial crisis marked the moment when the neo-liberal economic model ran out of road. In the acute stage of the crisis, nation states spent hand over fist to bail out the financial sector and stabilize the economy; a gesture for which they received no thanks from the markets and for which populations continue to pay through increased taxation, reduced spending, and lower economic growth. For many voters, the financial crisis was the point at which democratic control over the economy was revealed to be a chimera and the efficacy of parliamentary democracy itself brought into doubt.

A second dimension to the hollowing out of European democracies was the spatial shift in power relations associated with the emergence of multi-level governance, including the growth of the supranational tier via the EU and other organizations (Eick et al., 2024; Taylor et al., 2013). As Kübler et al. describe it, this was “a process of de-nationalization [that] entailed a shift of policy-making power away from the national government in three directions: upwards (to supra-national institutions, such as the EU), sideways (to independent regulatory agencies and private governors), as well as downwards toward sub-national authorities” in a process in which “statehood has become more and more de-nationalized, and the distance between the state (elites) and the nation has grown” (Kübler et al., 2024, p. 433; see also Kübler, 2015). This insight has been reflected in a recent focus on the spatial dimension of populist politics in Europe (Chou et al., 2022).

We might expect that the cumulative impact of the neo-liberal turn, a perceived capitulation to the markets, and the diffusion of political accountability would drive a third dimension of the hollowing out process in European democracies—a decline in levels of trust in political institutions amongst some segments of European electorates. However, the data on political trust are not at all clear. Studies of levels of political trust over decades note a number of methodological problems around issues such as the inherent problems of cross-national comparison, volatility, and trendless fluctuation, and how to identify the underlying causes of declining trust when it can be measured (Kołczyńska et al., 2024). This ambiguity persists today, with only Spain and France demonstrating a persistent and obviously structural decline in political trust over the last two decades (Van der Meer and Van Erkel, 2024).

In other European countries, levels of trust fell markedly in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis but had broadly speaking recovered to their historical levels before the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 to 2022. What exactly those historical levels are vary from country to country and the only area of consensus across multiple studies seems to be around the impact of levels of education on the reported amounts of trust amongst poll respondents in various European countries (Van der Meer and Van Erkel, 2024; Grande and Saldivia Gonzatti, 2025). Lower levels of educational attainment as measured by respondents' highest formal qualifications appear to be associated with higher levels of political distrust. This trend is stronger than trends amongst specific age groups or other descriptive characteristics such as sex and/or gender, but its significance varies across European democracies, with “education gaps” in trust amongst respondents notably higher in northern and western Europe than in central and southern Europe (Kołczyńska et al., 2024, p. 13).

So, contingent explanations for the rise of populist politics argue that we have seen a 2-fold process in which governments across Europe capitulated to the markets and multi-level governance has diffused political accountability and further distanced political elites from European voters. As a result, we see some evidence of a subsequent erosion of trust amongst some segments of European electorates. These accounts argue that European voters subsequently punished mainstream parties and began to vote for populist parties in greater numbers than before. In northern Europe, including Germany, these parties were mainly located on the right of the political spectrum. For German voters, therefore, the AfD was not just a vehicle for popular anger but also filled the political or even moral void that mainstream parties had created. As Noonan points out when explaining why Donald Trump's 2016 Presidential campaign so successfully cut through with many working-class voters in the United States; “the unprotected came to think they owed the establishment—another word for the protected—nothing, no particular loyalty, no old allegiance” (Noonan, 2016). This observation could easily be applied to sentiment amongst some elements of the German electorate.

In contrast to this dominant contingent or crisis-driven version of the demand-side explanation, there is also a body of scholarship, working from both empirical and theoretical perspectives, which posits populism as a more constitutive element of late modernity. In this often-contested literature we find references to concepts such as “post-democracy” (Crouch, 2005), “liquid modernity” (Bauman, 2000), “simulative” (Blühdorn, 2013) or even post-“peak” (Blühdorn and Butzlaff, 2018) democracy. For these scholars, the notion of a contingent economically-driven democratic crisis is often highly problematic or even a category error.

In this body of literature, democratic development, in as far as this is even an appropriate description, is not linear. For Crouch, who works in a space between contingent and constitutive explanations, the developmental process is skewed by neo-liberalism and the form it takes is that of a parabola or bell-curve. But Crouch, coming from quite an orthodox Marxist tradition, also conceives of conditions where this skew can be mediated or even reversed. Other scholars, however, see the emergence of populist politics as an inevitable feature of the contradictions of late capitalism and the alienation it generates amongst an increasingly critical population. If one accepts these explanations, any evidence of declining political trust discussed above can be seen as either confirmation of the growing epiphenomenality of those institutions or as evidence of more informed and socially untethered citizens holding them to greater account. Either way, the implication is that populist politics should not be regarded as an aberration or disfunction of politics because any reversal to some (real or imagined) political status quo ante is impossible.

Nevertheless, to paraphrase Gramsci, this account presents a world in which the old politics is dying, and the new politics struggles to be born. Such an impasse does not necessarily produce monsters, but it does present contradictions. As Grande and Gonzatti observe, “distrustful citizens combine demands for an extension of participatory democracy, restrictive views on immigration and minority issues, and political preferences for radical right populist parties” (Grande and Saldivia Gonzatti, 2025, p. 3). If this is correct, the German political settlement would find it difficult to accommodate these demands. Thus, for Blühdorn and Butzlaff, both scholars familiar with Germany, the current instability within the German party system is the manifestation of profound change. In other words, they are morbid symptoms that indicate that “liberal democracy is set to metamorphose into something categorically new” (Blühdorn and Butzlaff, 2018, p. 10).

3.2 Demand side explanations and Germany

So how well do these competing demand-side explanations of populist politics capture events in Germany? Let us start with contingent explanations. Academic research demonstrates the extent to which the period after the global financial crisis saw the AfD emerge and take votes off the mainstream parties as well as mobilize erstwhile non-voters (Lees, 2018a). But, at the same time, Germany's experience of the global financial crisis was different to some other European democracies. Given its high dependence on exports, Germany saw its economy contract by almost 6 per cent in the immediate aftermath of the crisis but it was the quickest of the major economies to begin to recover from the immediate shock and, by 2014, Germany's public finances were back in surplus. This quick recovery meant that Germany escaped the sustained and socially damaging rises in unemployment—particularly amongst younger age cohorts—seen elsewhere in Europe. For instance, in 2009 the unemployment rates in Germany and France were 7.2. and 9.1 per cent of the two countries' respective workforces. By contrast, 10 years later German unemployment was just 3 per cent whereas French unemployment stood at 8.4 per cent of the workforce (OECD.stat, 2025). Thus, whilst the contingent explanation and the focus on the global financial crisis might create a plausible explanation for the decline in political trust and the strength of party populism in France; in Germany it requires more nuance and contextualization.

As discussed above, scholars have argued that the global financial crisis had a profound impact on the attitudes of voters, but the data do not necessarily demonstrate this. If we look at voters as consumers, the OECD's consumer confidence index showed a sharp drop below trend in Germany and France (to 97.5 and 97.3 of 100 respectively) in the immediate post-crisis period but German consumer confidence soon returned to trend and, by 2019, confidence in both countries had returned to trend. Interestingly, the COVID-19 pandemic that began in the following year had a much more profound impact on consumer confidence than the global financial crisis in both countries and consumer confidence across all European democracies is still struggling to return to trend (OECD.stat, 2025). To sum up, the data show that—in Germany at least—the global financial crisis did not bring about the systems-level shift in levels of optimism and/or pessimism about personal economic prospects that would follow from explanations of populist sentiment in the electorate that place the global financial crisis as the heart of the narrative.

In a similar fashion, Eurostat data do not pick up a substantive change in attitudes to democracy in Germany and, where we can see a change since 2007/08, it is in the opposite direction to what we might expect. A degree of popular disaffection with liberal democracy across Europe can be tracked back in the polling data for decades (see Mair, 2013, for instance). Eurostat polling data dating back to 1973 on “satisfaction with democracy” in Germany demonstrates a significant minority of around 31 per cent who were “not very” or “not at all” satisfied with democracy (but also clear majorities of an average of 67 per cent of respondents who were “very” or “fairly” satisfied).

Following on from this observation, harmonized data compiled by the TRUEDEM project allow us to compare “trust in government” between German and French citizens over the period 2015 to 2022. Previous research has established that the impact of the “education gap” on level of trust has been historically lower in Germany and France than it in other northern or western European democracies (Kołczyńska et al., 2024). Nevertheless, the TRUEDEM data reveals significant differences between the two countries. Levels of trust in government in Germany are consistently buoyant, with an average of 53.6 per cent of respondents reporting a positive evaluation of government. By contrast, attitudes in France are consistently more negative with an average of only 25.4 per cent of respondents holding a positive view (TRUEDEM, 2025).

As Grande and Gonzatti argue, “Germany is among the North-West European countries whose political systems have benefitted from high levels of trust and political satisfaction” (Grande and Saldivia Gonzatti, 2025: 7) over a sustained period of time. This embedded legacy of political trust has been one demand side factor that has to some extent countered the impact of the increased fluidity in German party politics. As already discussed, electoral turnout has trended downwards considerably on the 90.7 per cent that voted in the 1976 Federal election, the high point of Gordon Smith's politics of centrality (Smith, 1976). Nevertheless, recent Bundestag elections have seen electoral turnout rise again, from 70.8 per cent in the 2009 elections to 76.2 per cent in 2017, 76.4 per cent in 2021 and 82.5 per cent in 2025 (Bundeswahlleiterin, 2025). This upward trend comes after historic lows associated with periods of centrist technocratic government under Chancellor Angela Merkel's successful strategy of “asymmetric demobilization” (Schmidt, 2014) in which the CDU/CSU moved on to political terrain that had previously been associated with the center-left. From 2017 onwards, however, Merkelism was in retreat and the higher electoral turnout that we have seen in subsequent elections reflects the increased polarization and subsequent re-invigoration of political debate in Germany that has accompanied the AfD's emergence and consolidation within the German party system. The implications of this insight are discussed later in the article.

Taken in the round, therefore, the data discussed above indicate that there is a significant proportion of the electorate in Germany—around a third perhaps—that are dissatisfied with or even reject democracy and have often not bothered to turn out and vote. Consistent with previous observations about the impact of spatial changes on the growth of populist politics (Kübler et al., 2024; Chou et al., 2022), this electorate is by no means exclusive to the former eastern states of Germany but is nevertheless strongly concentrated in them. Thus, whilst not explicitly a regional party like the Bavarian CSU, the AfD's “identitarian roots in former East Germany” (Kübler et al., 2024; Op Cit: 434) are distinctive and often mobilized to critique the wider political settlement that underpins the Federal Republic. As already noted, this also appears to be the political space that offers the most potential for the BSW.

The persistence and apparent electoral viability for AfD, BSW and indeed the Left of a kind of regional, anti-system exceptionalism in the states of the former East Germany reflects the ongoing socio-economic and attitudinal differences between the states of the former Federal Republic and German Democratic Republic that still persist 35 years after German unification. Some of these differences are down to structural disadvantages still suffered by the region, in terms of levels of economic density, trends in productivity, demographics and so on, despite the estimated 2 trillion Euros nominally transferred from west to east since 1990. Others, such as more negative attitudes to democracy and lower levels of trust in democratic institutions (Decker et al., 2019), could be interpreted in the early years after unification as cohort effects based on different lived experiences of West and East Germans after 1945, but as these cohorts die out and are replaced, these explanations are less useful today (Kura and Rentzsch, 2025). What seems to still drive a sense of difference in the eastern states is the feeling of a lack of representation, including amongst economic and political elites (Reiser and Reiter, 2023), and a strong sense of not being recognized, of not being sufficiently “seen” in political terms (Arzheimer and Bernemann, 2024).

In order to be seen, these disaffected voters need to be taken seriously. AfD voters are more likely to be young, male, located in the lower middle or working classes (Widfelt and Brandenburg, 2018; also, Mondon, 2017) and concerned about immigration (Stockemer, 2016) but that doesn't mean that they are all racists or that the relatively comfortable middle classes are not also represented in their ranks (Rydgren, 2008; Mondon, 2017, Op Cit.). In other words, these voters are not marginal, and they are still engaged, just not in the manner in which German elites are comfortable or to which they have been able to respond effectively. And this is where the AfD and, potentially the BSW, are ahead of the mainstream parties.

To sum up this section, the data does suggest that the persistence of this substantial anti-system minority provides a practical challenge to the German political settlement but, to date at least, it does not validate Blühdorn and Butzlaff's notion of a “profound” de-legitimation of democracy (Blühdorn and Butzlaff, 2018 Op Cit.: 11). On the contrary, one could argue that the emergence of populist politics in Germany has re-energized the electorate, many of whom have voted again for the first time in years. But to explain how populist politics made this breakthrough, we have to turn to supply-side explanations of populist politics.

4 Supply-side explanations

Supply-side accounts of politics focus on issues such as the origin of parties, the nature of political leadership, and the political opportunity structures in which political entrepreneurs operate.

The emergence or revival of populist right wing or extreme right-wing parties across Europe in recent decades is well documented in the academic literature (see Art, 2011; Mudde, 2007; Carter, 2005; Ignazi, 2003). One of the more enduring questions in the literature is why some of these parties emerged and consolidated themselves within party systems whilst others enjoyed limited success but failed to carve a more permanent niche within national party systems? So, for instance, why have the AfD in Germany, the RN in France, Reform in the UK or the Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid, or PVV) in the Netherlands established themselves in their respective countries whilst the Schill Party, the Populist Party (Parti populist, or PP), the Referendum Party or Pim Fortuyn List (Lijst Pim Fortuyn, or PLF) failed to do so in the same respective countries? Some of this is down to the slings and arrows of good fortune as well as the shrewd political management of figures like Marine Le Pen, Nigel Farage or Geert Wilders. But, as De Lange and Art point out, “to explain instances of breakthrough without persistence and instances of breakthrough with persistence, agency is a necessary (but not sufficient) factor” (De Lange and Art, 2011, p. 1229). We need also to talk about structural attributes.

The article now assesses three key issues involved in explaining the AfD's and—to a lesser extent—the BSW relative success to date and predicting future prospects. These are, first, Germany's electoral and party systems, second, the party building process, leadership stability and renewal, and finally, electoral and/or legislative performance and/or government participation.

4.1 Electoral and party systems

The key features of the long-established concept of the “political opportunity structure” (Kitschelt, 1986) are described as “consistent—but not necessarily formal or permanent—dimensions of the political struggle” (Tarrow, 1998, p. 19–20). Applying the concept in the context of political parties, the consistent dimensions that matter range from the impact of formal or even legal constraints, such as the nature of the electoral system, rules on party funding and so on, through to more informal configurations of social power, changing socio-economic conditions or demographic shifts.

The most consistent institutional variables in shaping the context within which parties emerge are the electoral system and associated electoral rules, such as the size of the electoral threshold (Golder, 2003), the degree of decentralization (Arzheimer, 2009), and relative district magnitudes (Magnan and Veugelers, 2005). Taken together, these have a profound impact on the degree of openness party systems present to emergent parties.

As we are looking at the impact of Germany's electoral system over many years, we need to look back beyond the recent electoral reforms discussed earlier, when the German electoral system could still be described as an MMP system. As measured by the Gallagher Index (Gallagher, 1991), Germany's former MMP system was not a “pure” proportional system, but it was significantly more proportional than, say, France's two-round run-off (2RS) plurality system or the UK's first-past-the-post (FPTP) plurality system.

The degree of proportionality in any electoral system can be expected to have consequences for the number of political parties able to enter the parliament and have an impact on government formation—in other words, the “effective number” of parties (Laakso and Taagepera, 1979) that was discussed earlier in this article. We know that it is possible for countries with proportional systems to generate low numbers of effective parties through two party dominance and the best example of this is Malta, where the country's Single Transferable Vote (STV) system continues to generate a two-party dominant system (National vs. Labor) that has been the norm since the 1950s. Nevertheless, all things being equal there is a broad correlation between the level of disproportionality of the electoral system in a given country and the number of effective parties. Moreover, in heavily disproportional systems it is rare to find a high effective number of parties in the parliament even if, as is the case in the UK, the actual number of parties in the parliament is quite high. By comparison, Germany's former MMP system tended to generate coalition governments, but the effective number of parties was quite low compared with other national systems with similar levels of proportionality. It will be interesting to model how this will change over time, following the recent reforms in Germany discussed earlier.

Nevertheless, the historical picture is of an electoral system that erects significant but not insurmountable barriers to entry to new parties like the AfD and BSW. At the Federal level, German MMP has not rewarded geographical concentrations of support to the same extent as FPTP systems and while the Bavarian CSU, as noted above, is the exception rather than the rule this can be accounted for by Bavarian exceptionalism and historical contingency at the foundation of the Federal Republic. Unlike most other electoral systems, however, the existence of the two votes in MMP allows vote splitting, whereby voters vote for a smaller party with their list vote and for one of the bigger parties for the directly elected seat in which they reside. Much of the AfD's vote in Federal elections has come from CDU and- to a lesser extent—SPD voters who “lent” their list vote to the AfD (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, 2017). This has undoubtedly been an advantage in allowing the AfD to gain a foothold in the German party system but did not seem to help the BSW to the same extent in the 2025 Federal elections.

Consistent with the observations of Kübler et al. and Chou discussed earlier in this article, the key institutional feature that has traditionally acted as a platform for new political parties in the Federal Republic is Germany's system of multi-level governance, including the EU tier and the German federal system (Kübler et al., 2024, p. 433; Chou et al., 2022). The EU elections of 2014 provided the first foothold for the AfD, in which they came fifth with just over 7 per cent of the vote, after falling just short of the 5 per cent electoral hurdle in the Federal election of the previous year (Lees, 2018a). Since this breakthrough, the AfD has been a continuous presence in the European Parliament and currently have 15 seats in the chamber. Similarly, the BSW has 6 members of the European Parliament following the 2024 elections. Moving on to Germany's federal system, with its system of distinct and sometimes competing powers between the different levels of government, including exclusive powers for the constituent states, we see a constellation of 16 partly sovereign and often quite parochial party systems, in which parties can emerge and consolidate under conditions that—for various reasons, including the limited set of policy areas under consideration—are more conducive to new political actors. This was certainly the case with the Greens in the 1980s and 1990s (Lees, 2000) and subsequently the Left (Hough et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, therefore, the AfD also made its breakthrough at this level—particularly in the eastern states of the Federal Republic, such as Brandenburg (2014; 12.2 per cent of the vote), Saxony (2014; 9.7 per cent), and Saxony-Anhalt (2016; 24.3 per cent). At the time of writing, the AfD are represented in all but two (Bremen and Schleswig-Holstein) German states. To date, the state level is also the key domestic arena in which the BSW has been able to break through, with a presence in the state parliaments of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia.

To sum up, therefore, the political opportunity structure provided by Germany's electoral and party systems is a moderately benign one for Germany's populist parties of the right and left. Germany's MMP electoral system has provided opportunities for new political challengers, and it remains to be seen what the long-term impact of the recent reforms will have. In particular, Germany's embeddedness in structures of multi-level governance has provided significant platforms outside the Bundestag for the AfD and to a far lesser extent the BSW to emerge and consolidate. It is to this process of consolidation that article now turns.

4.2 The party building process, leadership stability and renewal

The process of party building is both a dependent and independent variable. As the previous section demonstrates, much depends on the political context in which a political party emerges and develops but party structure and the resilience of its internal processes also matter and may determine a party's prospects in the medium to long term. Drawing on Bolleyer's (2013) and Bolleyer and Bytzek's (2013) work on the challenges of party institutionalization and discussions around the origin of parties (Panebianco, 1988; Duverger, 1964), it is possible to make two major observations about the development of the AfD that also cast light on the development to date and the future trajectory of the BSW.

First, the development of the AfD challenges much accepted wisdom about the party building process and the importance of leadership stability in facilitating party consolidation. Bolleyer and Bytzek (2013) distinguish between, first, parties that emerge from already organized social groups and, second, so-called entrepreneur parties, founded by individuals that have no long-established ties to existing groups. Political parties that emerge from existing groups confront a strategic dilemma. On the one hand, in order successfully to institutionalize themselves and to achieve credibility with undecided voters, emergent political parties need to emancipate themselves from the social milieus from which they arise (Panebianco, 1988). On the other, new parties that maintain close ties with a social organization or movement are less likely to suffer defections (Bolleyer and Bytzek, 2013: 773) because of the higher degree of “value infusion” that arises from members' emotional attachment to the party (Levitsky, 1998). By contrast, entrepreneur parties do not face the same pressures to emancipate themselves from the groups from which they emerge but also lack the organizational base to survive political setbacks.

When applying these models to Germany, we see that the BSW neatly maps onto the model of the entrepreneur party (indeed, the clue is in the name!). However, the AfD does not map so neatly onto either of these models of party organization. The AfD emerged from a small intellectual milieu in 2013 but has gone on to mobilize a broader and more inclusive social base. One of the founding members and former leader, Alexander Gauland, was previously a high-flying member of the CDU and Department Head of the Federal Ministry of the Environment who left the party in protest at the centrist political course charted by Angela Merkel (Franzman, 2016). Gauland and his supporters left the CDU to form the organizational backbone of the AfD. At the same time, however, the AfD did not maintain tacit links with the CDU/CSU but rather effectively declared an open state of hostilities with them. For instance, Gauland marked the AfD's entry into the Bundestag in 2017 by promising a gathering of party faithful that “We will hunt Mrs. Merkel … and we will return our land to our people” (Hanke, 2017).

In effect, the AfD chose to walk a narrow political path in which the party provided sufficient pressure from the right flank to force the CDU/CSU, now under the leadership of Friedrich Merz, to distance itself from Merkel's liberal approach to immigration but, at the same time, maintain sufficient political distance from the CDU/CSU to appeal to disenchanted working class voters who would not normally support the Christian Democrats (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, 2017). In other words, the party has to date struck a successful balance between social groundedness and successful political entrepreneurship.

In the early years of its existence, the AfD also defied conventional wisdom on the resilience of political leadership and its ability to control the party organization and discipline its members. In the literature, scholars identify a negative correlation between leadership crises and party success (Bynander and t'Hart, 2008), but the AfD underwent two comprehensive changes of leadership in a short space of time and another more orthodox change of leadership more recently. The first major change, in 2015, resulted in the national-conservative Frauke Petry ousting the economically liberal academic Berndt Lucke as the party's principal speaker. The second upheaval, in early 2017, saw Petry step down after trying to persuade her party conference to take a more ideologically moderate line, to be replaced by a dual leadership including the belligerent Gauland. During this period, the AfD's political posture became increasingly right-wing as it sought to mobilize around voters' anxieties about immigration and in particular about the increasing visibility of Islam in German society. In the 2021 Federal elections, the AfD's relatively disappointing electoral performance prompted another change of leadership, with a joint team of Tino Chrupulla and the high-profile Alice Weidel, who was subsequently the AfD's Chancellor-Candidate in the 2025 Federal election.

Under other circumstances, these rapid and often highly disrupted changes of leadership might have put off undecided voters—but the opposite happened, with a run of good performances in state elections in 2015 and early 2016 after the first change, the extraordinary electoral breakthrough in the 2017 Federal election after the second, and the AfD's recent electoral performance following the third in the 2025 Federal election. Moreover, these changes coincided with and further drove the radicalization of the party as it moved toward an orthodox right wing populist policy profile (Lees, 2018a). The clarity of the AfD's political message and its strong electoral performance is evidence that the AfD has carved out a distinctive niche in the German party system and will survive into the long term.

4.3 Electoral and/or legislative performance and/or government participation

This leads to the second major observation to be made when examining the developmental trajectory of the AfD. In order to survive, new political parties must maintain electoral momentum and, where appropriate, be able to demonstrate effectiveness in the legislative environment (Bolleyer and Bytzek, 2013). In the end, this must also potentially mean participation in (or at least tolerance or confidence and supply support of) government.

Scholars make a number of predictions about the impact of electoral and/or legislative performance and/or government participation on the survival of breakthrough parties. First, and most obviously, electoral success helps emergent parties consolidate their positions within a party system. Success builds loyalty amongst the membership, raises the party's profile with voters and in many cases secures access to state resources that can be used to further institutionalize and professionalize the party (Lees, 2000). Because of this need to establish and consolidate their presence, emergent political parties often pursue a distinct ‘vote seeking' strategy rather than that of “policy seeking” or “office seeking” (Müller and Strøm, 1999). Having entered parliament, however, emergent parties are under a new set of pressures to make an impact within the legislature. Making such an impact will often have a beneficial effect on emergent parties' longer-term electoral performance so it is important that they are ready for the new challenge. In their statistical analyses of new party survival across 17 democracies, Bolleyer and Bytzek found that, first, the successful re-election of emergent parties is an indicator that they have adapted to the pressures of public office and, second, that the length of time between an emergent party's formation and its first entry into parliament correlates positively against the size of parties' vote share in subsequent elections (Bolleyer and Bytzek, 2013; see also Sartori, 1976).

It is easy to forget that the AfD came second in the 2025 Federal election only 12 years after its foundation. As already discussed, the party narrowly missed scaling the five per cent electoral hurdle in the 2013 Federal elections and, in the intervening 4 years before its successful 2017 Federal election performance, the party built a presence in the European Parliament and across most of the German states. As a result, the AfD entered the 2017 Federal election campaign with a quite developed organizational structure and have taken advantage of millions of Euros of state support since then—amounting to almost half of the party's total income (DPA, 2004). Such sums must inevitably drive forward the institutionalization of the party.

Nevertheless, despite its demands to be considered by the CDU/CSU as a potential collation partner following the 2025 Federal election, there is no evidence yet that the AfD is evolving beyond what remains a straightforward vote-seeking strategy. The AfD's behavior inside the Bundestag remains disruptive and deliberately confrontational, deploying what has been described elsewhere as a “strategy of provocation” in order to maintain a strong media profile and to double-down on the party's anti-system credentials with its core supporters (Lees, 2018b). As the German political scientist Michael Koß argues, this insurgent strategy comes with risks: “'anti' parties engaging in extended obstruction eventually strengthen the procedural bargaining power of establishment parties and provide them with a justification for the centralization of agenda control” (Koß, 2015, p. 1063). At present, this appears to be the case, with the so-called “Firewall” still intact and plans afoot in some quarters to ban the party. In the next section, we discuss why this would be a mistake.

5 Discussion and conclusions

This article describes the impact that populist disruptor parties, particularly the right populist AfD, have made on the German party system. It argues that the AfD has had a truly disruptive impact on the tenor of German political discourse and on the dynamics of government formation. The implications of these changes have been noted and monitored by political analysts around the world.

The article charts how the German party system has developed over time, through periods of consolidation and subsequent stability, before undergoing a slow process of fragmentation and, more recently, increasing polarization. In this new politics of fluidity, the most obvious symptom of the breakdown of Germany's former consensual political settlement has been the emergence and consolidation of the AfD as an explicitly anti-system party that challenges key aspects of the Federal Republic's political economy and geo-political posture.

The article explores demand and supply-side explanations for the emergence of the AfD and other populist challengers, including on the left of the political spectrum. The article breaks down demand side explanations into those that are contingent, based on the assumption that the emergence of populism is in some way a suboptimal outcome driven by crises, and those that argue that populism is more a constitutive symptom of late modernity and may even be an emancipatory development. Without essaying these arguments again, the article concludes that both sets of explanations have their merits but fail to fully account for the upsurge in populism in Germany and, in particular, for the emergence of the AfD at this point in the political development of the Federal Republic. In particular, when compared with other European countries such as France, the UK, and so on, some of the antecedent conditions—such as persistent economic crisis or under-performance and declining trust in institutions—are not as obviously present in Germany.

The article then went on to consider supply-side explanations, in particular formal and informal structural attributes. These were, first, Germany's electoral and party systems, second, the party building process, leadership stability and renewal, and finally, electoral and/or legislative performance and/or government participation. Here, again, the AfD appears to be a critical case that often defies some of our assumptions about the (negative) impact of leadership instability or a failure to adopt an increasingly pro-system or co-operative stance once in parliament. Nevertheless, for the AfD—and potentially for left populists like the BSW—there remains strong systemic bias that limits their impact on government formation at the state level and certainly at the Federal level. As a result, it is reasonable to conclude that the AfD's chances of participating in or even leading a government at the national level in Germany is smaller than in European democracies with more majoritarian systems such as France.

So where does this leave Germany's populist challengers? The Left has increasingly become a tacitly pro-system party and the failure of the BSW in the 2025 Federal election introduced an element of doubt about their future prospects. By contrast, the AfD has become an established and formidable electoral competitor within the German party system whilst if anything steadily radicalizing over the course of its development.

This presents the German political system with a problem that has no cost-free solution. As touched upon earlier, the AfD's political positioning is not dissimilar to that of the FN in France or Reform in the UK. At the same time, the party is not a unitary actor. There is no doubt that there are elements of the AfD that are Fascist or proto-Fascist in nature but there is also a strong right-conservative strand that would not be out of place in, say, the US Republicans or the UK Conservative Party. Is it possible for a political system like Germany to co-opt this latter element or does the Federal Republic's norm of “militant democracy” (Wehrhaft Demokratie; Salzborn, 2024; Fuhrmann, 2019) require a maintenance of the Firewall and the exclusion of the AfD in perpetuity? One the one hand, political science tells us that attempts by mainstream parties to co-opt or neutralize far right competitors often only serve to mainstream or legitimize far right policies and rhetoric (Brown et al., 2023; Akkerman et al., 2016). On the other, however, the further exclusion of the AfD only serves to amplify the party's claim to speak on behalf of a people that is being excluded by the elites—particularly, for the reasons discussed earlier, when a lot of those people are in the eastern states. Under such circumstances, the process of government formation not only becomes increasingly inefficient but also the norms of representative and/or responsible government are further undermined.

The most militant manifestation of the norm of militant democracy would be to ban the party altogether—a possibility that is actively being discussed amongst the political establishment and the security services in Germany. This would be a rational extension of the thinking behind the Firewall and could be supported in the Courts by intelligence sources. However, I would argue that this course of action would be a disaster for Germany's democracy in the long term. Thirty-five years after German unification, the AfD is the most popular party in the states of the former East Germany and the exclusion of the AfD—like that of the PDS in the 1990s—only serves to illustrate the fundamental asymmetry in the post-1990 German settlement and further expose the socio-economic and attitudinal divides between west and east. Moreover, in its militant defense of liberal democracy, such a move would be fundamentally illiberal and self-defeating—revealing logical flaws in the German constitution's approach to democracy that have existed since the foundation of the Federal Republic in 1949. It remains to be seen how Germany will solve its “problem” with its populist disruptors.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CL: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Akkerman T. De Lange S. L. Rooduijn M. (2016). “Inclusion and mainstreaming?: radical right-wing populist parties in the new millennium,” in Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe (Routledge: London), 1–28. doi: 10.4324/9781315687988

2

Algan Y. Guriev S. Papaioannou E. Passari E. (2017). The European trust crisis and the rise of populism. Brookings Pap. Econ. Act.2017, 309–383. doi: 10.1353/eca.2017.0015

3

Alternative für Deutschland . (2025). Zeit für Deutschland: Programm der Alternative für Deutschland für die Wahl zum 20. Deutschen Bundestag: Berlin.

4

Arestis P. Singh A. (2010). Financial globalisation and crisis, institutional transformation and equity. Cambridge J. Econ.34, 225–238. doi: 10.1093/cje/bep085

5

Art D. (2011). Inside the Radical Right: The Development of Anti-Immigrant Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511976254

6