- 1Laboratory of Natural Resources, Sochava Institute of Geography Siberian Branch Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk, Russia

- 2Department of Politology, History and Region Studies, Irkutsk State University, Irkutsk, Russia

Since 2022, the concept of unfriendly countries has emerged in the political discourse due to the publication of the corresponding list by the Russian government. Concurrently, the countries and regions included in this list possess a de facto distinct position in relation to Russia, exhibiting varied levels of engagement with Russia. Despite the longstanding conceptualization of states as either friendly or hostile in political science, dating back to the seminal works of Klingberg and Wolfers, contemporary discourse in the field continues to explore the development of novel methodologies for the identification of international coalitions. This article offers a novel interpretation of the scale of friendliness-hostility from the perspective of political geography. It presents an algorithm developed by the author to assess the degree of friendliness or hostility among geopolitical subjects. This algorithm is based on a set of data, including diplomatic status, level of integration, military exercises, sanctions regimes, visa policy, coherence of votes in the United Nation General Assembly, and image in the media. A comprehensive evaluation was conducted, encompassing a 5-year period from 1990 to 2024, to ascertain the political disposition of the surrounding subjects toward Russia. The study’s findings indicate that the emergence of the two “flanks of unfriendliness” from the west and east of Russia occurred in a gradual fashion throughout the post-Soviet period. Concurrently, there was a parallel strengthening of the consolidation of the intra-Eurasian space. However, this consolidation does not occur with a sufficient degree of symmetry and tension. The consolidation of the intra-Eurasian space is illustrated cartographically. The focus of this study is Siberia, which, due to the aforementioned changes, is now considered the geographical heart of Greater Eurasia. The conclusion summarizes the results, emphasizing the dynamism of the geopolitical situation and the need for further study of interactions in the sphere of international relations in precise and quantitative categories and measurements. It also outlines further research using the presented algorithm for identifying the degree of international friendliness-hostility.

1 Introduction

The contemporary geopolitical landscape is characterized by significant instability, precipitated by the emergence of major conflicts that have profoundly altered the geopolitical landscape. This shift has led to the dissolution of established international coalitions and the formation of new ones, thereby reshaping the global order. The Russian–Ukrainian conflict, which commenced with the Maidan revolution in 2014 and teared in 2022 with the Russian special military operation, was a primary catalyst for this shift. In the contemporary geopolitical landscape, numerous dormant conflicts are resurfacing, prominently exemplified by the ongoing tensions in the Middle East, Jammu and Kashmir, and other regions worldwide and the rise of the Sino-Russian partnership (Morgado and Hosoda, 2024). These changes are having a profound impact on the geopolitical landscape, leading to significant shifts in the global position of each nation.

The geopolitical position of countries and regions constitutes a fundamental category in official strategic planning documents and within the context of Russian socio-political discourse. However, a significant proportion of these publications is characterized by speculative argumentation and a superficial understanding of geographical space. The multidimensional concept of geopolitical position is expressed in three parameters of geopolitical entities (states, integration associations, regions, etc.): geographical influence, expressed in the level of connectivity of entities with each other and the attraction of their main demographic and economic centers; geopolitical power (or aggregate power), expressed in gross indicators of hard, economic, soft power; and political relation between them (Fartyshev, 2017). The political attitude between geopolitical subjects can be expressed as a parameter on the scale of friendliness-hostility. This parameter is used in political science for the assessment of bilateral relations, trilateral relations, and specific international events.

In 2022, the Russian government promulgated the List of Unfriendly Countries and Territories (Order of the Russian Government No. 430-r of March 5, 2022 “On Approval of the List of Foreign States and Territories Committing Unfriendly Acts against the Russian Federation, Russian Legal Entities and Individuals”). This legislation, in essence, perpetuates the dichotomization of “ours” and “them” in the realm of foreign policy, a practice that finds its origins in the establishment of “Captive Nations Week” and the cataloging of “rogue states.” This convention has been a hallmark of American foreign policy since the administration of President Dwight Eisenhower in 1959. In 2002, Condoleezza Rice similarly designated four countries the so-called “axis of evil” (Iraq, Iran, and North Korea), expanding this list in 2005 to 10 countries (Libya, Syria, Cuba, Belarus, Zimbabwe, and Myanmar). These actions led to the institutionalization of a significant component of the geopolitical landscape: political relations between nations. The essence of this phenomenon is a subject of ongoing discourse. While the allocation of “strangers” has been relatively straightforward (notwithstanding the continuous supplementation of the aforementioned decree), the allocation of subjects exhibiting optimal amiability remains a more contentious subject. In the context of international relations, the degree of friendliness or hostility between nations is determined by the extent of their integration or, conversely, the application of sanctions pressure. It is imperative to understand the nature of these levels. The subsequent discussion will address the question of how these phenomena can be identified. The present study seeks to ascertain the properties, parameters, and significance for Russia of subjects exhibiting varying degrees of friendliness or hostility. It is evident that while Belarus and Abkhazia are regarded as highly cooperative allies by Russia, Kazakhstan and Armenia maintain a more cautious stance in aligning with Russia’s international stance, despite their substantial integration with Russia. The same gradation is observed on the opposite side—hostility—which means that these parameters are measurable by integral assessments.

The purpose of this article is to present the concept of an integrated assessment of friendliness and hostility and to show the dynamics of its change in the surrounding geopolitical entities in relation to Russia from the 1990s to the present.

2 Theoretical background

The issue of gradation of relations between states on the scale of “friendliness-hostility” has been a subject of discussion in scientific research for an extended period. A multitude of authors have proposed various approaches to measuring this “psychological distance” between nations. In the early 20th century, the prevailing sentiment was that tensions in relations could be measured as an indicator of the relationship’s dynamics (Klingberg, 1941).

Subsequently, interstate tensions began to be regarded as a dynamic element within the multidimensional political space, situated at the intersection of stability and conflict (Wright, 1955). Consequently, it became imperative to consider the subjective perception of the situation by political decision-makers, not only objective factors (Holsti, 1963). Researchers have focused on identifying the causes and factors influencing the level of tension, including such parameters as threat perceptions and assessments of opponents’ capabilities and intentions (Holsti, 1962; Leifer, 1974). Consequently, the notion of tension has been rendered more lucid and precisely delineated, signifying a constellation of dispositions and sentiments, including distrust and suspicion. Tension is also used as a similar term (Pestsov and Volynchuk, 2020). In mathematical models, political relations are frequently characterized as an unmeasurable quantity. To illustrate, Richardson’s arms race model incorporates the “magnitude of past grievances,” which can assume both positive and negative values yet is regarded as a constant (Richardson, 1960).

A notable illustration of this phenomenon is Balassa’s concept of stadiality in integration processes, which offers a systematic approach to understanding the progression of friendly relations (Balassa, 1961). Balassa’s seminal concept of stadiality of integration processes, as outlined in his 1961 publication, offers a foundational framework for understanding the dynamics of integration processes. In the economic sphere, this stadiality is manifested in the transition from a preferential trade zone to an economic union through various intermediate stages. A similar gradation exists in the military-political sphere, ranging from non-aggression treaties to a unified military command. In essence, the degree of interstate friendliness is contingent upon the interplay of numerous factors.

In addition to quantitative indicators, a set of qualitative scales measuring friendliness and hostility is employed. For instance, in the work of the international relations theorist A. Wolfers, titled “Discord and Collaboration,” the following gradation is presented:

• Irreconcilable enmity (state of war).

• Demonstration of hostility.

• Termination of friendly relations.

• Minimal relations.

• Cool relations or non-aligned relations.

• Active intra-directional cooperation.

• External-directional cooperation.

• Extreme manifestation of friendship (Wolfers, 1962).

The problem with Wolfers’ scale is the author’s subjectivity. His work was done during the Cold War, when military power influenced politics more than it does now. At that time, political science neglected the role of economics in politics.

The issue of creating quantitative scales became particularly relevant when databases of world events were created. These databases automatically collected events and classified them by tone. I. Goldstein presented a scale that quantified the degree of friendliness or hostility of each event (the Goldstein scale), forming the basis of the World Event/Interaction Survey (WEIS) events database (Goldstein, 1992). The sum of assessments of events occurring in one country in relation to another represents the current degree of attitude.

The development of extensive databases in conflict studies, which accumulate data on potential hostile events, has resulted in the creation of hostility scales (Maoz, 1982; Palmer et al., 2015). Subsequent to this, a more accurate and detailed measure of hostility has been created, based on Bayesian methods (Terechshenko, 2020). The general purpose of such scales is similar to that of Richardson’s models in that they are designed to predict the escalation of armed conflict between countries and to identify ways to de-escalate contentious international situations.

A critical geopolitical approach is instrumental in elucidating the nature of international relations, particularly with regard to the discernment of states’ friendliness or hostility. The critical geopolitical paradigm encompasses the examination of discourse, perceptions, and geographical representations of global nations. Within this framework, the notion of friendliness-hostility operates at the socio-psychological level (Koopman et al., 2021). These representations are encapsulated in symbols, images, and national stereotypes, which are identified through normative documents of strategic planning, official briefings, educational programs and textbooks, mass media, etc. (Fartyshev, 2022).

Furthermore, quantitative approaches to understanding friendliness-hostility as an integral characteristic are based on expert surveys (Nesmashnyi et al., 2022), principal component identification, etc. Consequently, this indicator introduces a significant geopolitical dimension to the analysis of geopolitical dynamics.

In the contemporary era, the most prominent index of global peacefulness is the Global Peace Index, which was developed by the Institute for Economics & Peace (Sydney, Australia). However, it should be noted that this indicator is composite in nature, evaluating not relative states, but rather the overall security of each nation worldwide, with this assessment informed by both its foreign and domestic policies (Morgan, 2021). The Militarization Index, as developed by the Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies, employs a comparable methodology (Bayer and Hauk, 2023).

Quantitative approaches to understanding relative friendliness and hostility as an integral characteristic of bilateral relations were based on expert surveys (Nesmashnyi et al., 2022; Wike et al., 2022), on point estimates (Pototskaya, 2018), and on the identification of main components (Safranchuk et al., 2023). Integral assessments of attitudes toward Russia and China were created on the basis of research conducted by Foa et al. (2022).

This indicator is therefore of significant value in terms of geopolitical analysis, as it brings an important geopolitical aspect to the fore.

3 Methods and data

The fundamental theoretical framework employed for the analysis is the theory of geopolitical position, a synthesis of traditional geopolitical and critical geopolitical approaches. This theoretical framework portrays the geopolitical landscape as a network of interwoven relations among geopolitical actors, with consideration for their geopolitical power, spatial distance, and political disposition. These variables are expressed on a scale ranging from amiability to animosity.

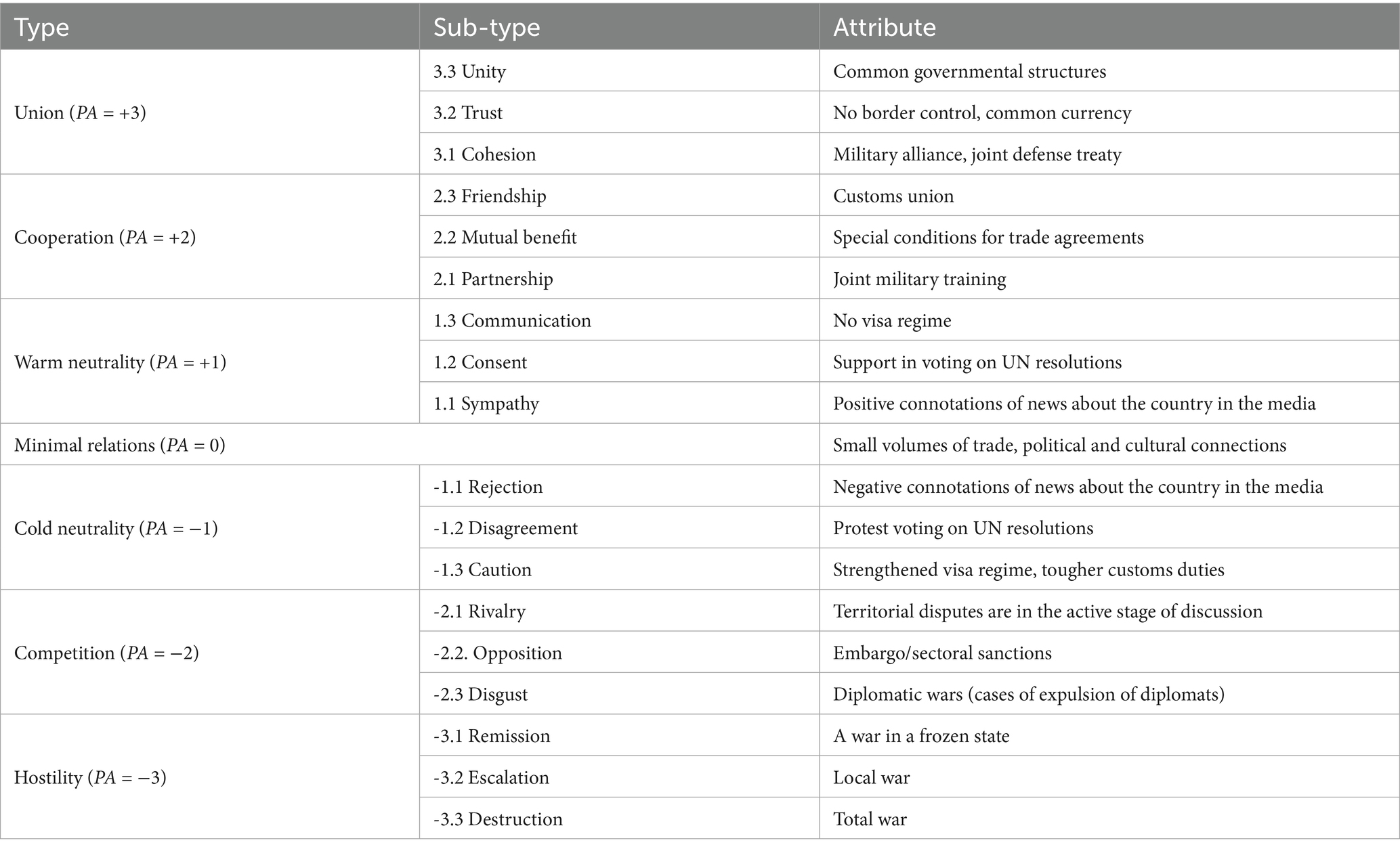

In earlier works, the typology of political attitude on a linear scale, “friendliness-hostility,” was proposed. This typology is characterized by clear criteria for the stages of the parameter PO (political attitude), starting from PO = 0, which represents the minimum of mutual relations, both in the direction of friendliness and in the direction of hostility. The typology is further divided into nine categories on the positive side and nine on the negative side (see Table 1). The assignment of one or another degree of gradation is based on clear criteria, which are improved in this article (Fartyshev and Pisarenko, 2024).

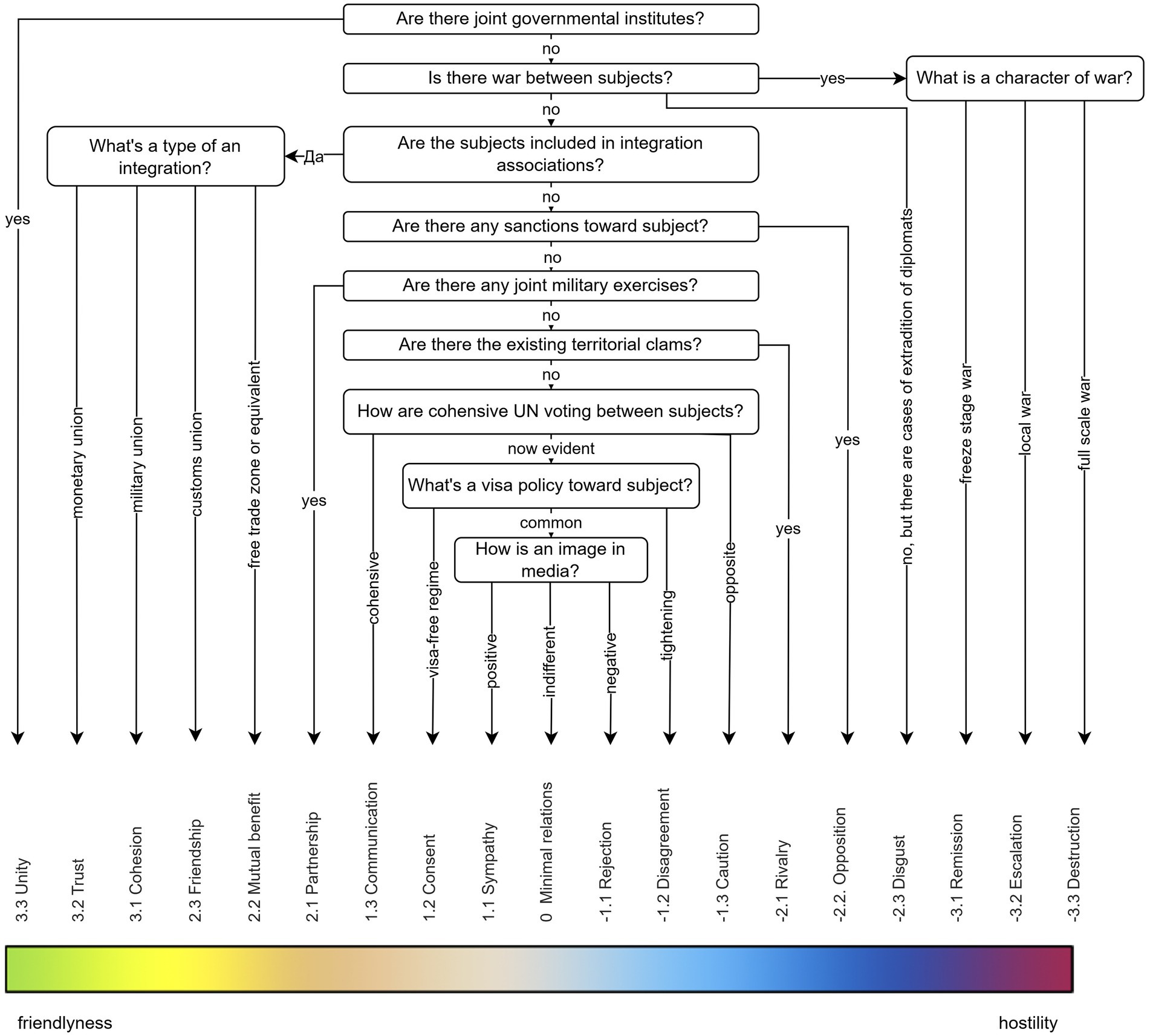

The conceptual scheme-algorithm for assigning categories to the integral assessment of friendliness-hostility of bilateral relations between geopolitical actors is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Algorithm for the integral assessment of the friendliness and hostility of bilateral relations between geopolitical actors (geopolitical relations).

In order to facilitate a comprehensive and systematized comprehension of the algorithm underlying the integral assessment of political relations, it is imperative to delineate the methodology employed in determining the degree of friendliness or hostility between political entities. This exposition will be meticulously articulated through a series of responses to nine pivotal inquiries.

First, the inquiry focuses on the existence of common governing bodies. This parameter enables the assessment of various geopolitical entities. For instance, it can be utilized to determine whether a geopolitical entity is part of another state (e.g., assessing Alaska as a sub-regional unit in relation to the United States), whether it is under external governance (e.g., assessing Greenland in relation to Denmark), or whether it is an autonomy of federal or confederal type (e.g., between Republic Srpska and Bosnia and Herzegovina), where a part of governance functions is transferred to one level of political space above. The formation of such relations can be observed in instances of maximum integration processes, wherein specific functions are delegated to the supranational level (a notable example being the European Union’s economic policy determination). While this issue assesses the extreme expression of geopolitical affinity, it does not negate the potential for adverse societal perceptions among subjects under shared governance (e.g., separatist regions) or other manifestations of enmity.

Second, the subjects’ status in regard to armed conflict must be ascertained. This phenomenon can be conceptualized as the diametrical opposite of the aforementioned state of hostility. In this case, it is imperative to delineate the state of war by its inherent nature: A war characterized by its openness, full scope, and intent to destroy the opposing entity or overthrow its leadership. This dynamic is exemplified by the historical confrontation between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the Republic of Korea (ROK) during the Korean War (1950–1953). A war that occurs within a specific territorial context or to achieve a particular objective. This type of conflict is illustrated by the ongoing tensions between Syria and Israel concerning the Golan Heights. A war that has reached a state of stagnation or impasse, as evidenced by the current state of affairs between Venezuela and Guyana. The ongoing dispute over the Essequibo region, which began in 2023, exemplifies this category of warfare, as it did not escalate into a direct military confrontation. A particular, milder case of this condition is the use of retorsions and reprisals. For instance, when diplomats or representatives of one entity are declared persona non grata and/or expelled from the territory, a state of diplomatic war may be declared. In accordance with recognized international diplomatic protocol, the utilization of retaliatory measures constitutes the final diplomatic maneuver prior to the formal declaration of war.

Third, it is imperative to ascertain whether the actors in question are affiliated with integration alliances. This inquiry enables the classification of amiability as a distinct attribute, distinguishing it from the various states of warfare that are considered incompatible. A currency union is defined as a degree of economic interdependence between two or more countries, wherein one country issues the legal tender for another, such as the Russian ruble for Abkhazia. A military union is a political alliance between two or more countries, where the principle of collective defense is operationalized, as evidenced by the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). A customs union is a trade agreement between two or more countries that aims to streamline trade by eliminating border controls, as exemplified by the Mercosur customs union. A common market or free trade area refers to a lower degree of economic integration between two or more countries, as evidenced by the free trade agreement between Russia and Vietnam since 2015.

Fourth, the existence of territorial disputes is a matter of concern. In addressing this inquiry, it is imperative to encapsulate a discursive form of warfare that does not escalate to tangible unfriendly actions of a political nature (e.g., between China and India over Arunachal Pradesh). The existence of a territorial dispute portends the potential for a more antagonistic stage. To a greater extent, this stage of unfriendliness applies to neighboring countries. However, other equivalent situations at the discursive level may also have conflictogenic potential. It is important that this discourse is formed at the official level (for example, declaring a country a sponsor of terrorism in strategic documents on foreign policy).

The fifth inquiry pertains to the imposition of sanctions. The policy of sanctions is, in essence, antithetical to the concept of integration as an expression of the fencing policy. While it may be regarded as the closest to the state of economic (trade) war, it is not inherently so, as it differs in terms of targeting (Timofeev, 2019). Sanctions can be expressed in various forms, including trade restrictions (full or partial embargoes), sectoral bans on cooperation, and financial freezes on assets. It is imperative to acknowledge that a subset of sanctions is characterized by their limited or illusory nature, serving merely as a signal of disagreement. This attribute of sanctions can be observed not only in the application of sanctions by external actors but also in the use of sanctions by allies, a phenomenon that merits attention (Timofeev, 2023). For instance, the restriction on the entry of persons belonging to the economic elite does not play a significant role in determining the level of friendliness or hostility of states.

Sixth, it is pertinent to inquire whether there are any ongoing joint military exercises. The factor of joint military exercises is an important criterion of friendliness, which is incompatible with the sanctions policy. Despite the declarative objectives of anti-terrorist defense or rescue operations, such actions suggest a political stance of friendly cooperation among nations and a signal for the formation of more robust international coalitions in multilateral exercises. Conversely, the refusal to engage in joint military exercises can be an instrumental factor in deterring the escalation of friendly relations. This is exemplified by the case of DPRK–Russia relations, where this issue is pivotal to the relationship with a third party, the ROK.

The present inquiry seeks to ascertain the visa policy between countries. In typical circumstances, visas established by political elites are utilized to ensure the barrier function of the border in the movement of individuals (Kolossov and Scott, 2013). In the context of friendly relations, countries enter into accords that involve the mutual abrogation of visa restrictions for specified periods or indefinitely. Alternatively, they may permit entry with the country’s internal passport. These arrangements are indicative of a fundamental level of trust between the nations involved. In instances where there is a pervasive sense of animosity, there is an escalation in visa restrictions, which can be interpreted as an initial manifestation of a policy of resistance. The tightening of visa requirements does not necessarily indicate a hostile attitude on the part of the issuing country. In some cases, the tightening of visa requirements may be due to sanitary and anti-epidemic reasons, although these reasons may be used as a pretext. It is also imperative to acknowledge that visa policies are not invariably reciprocal.

The eighth inquiry pertains to the question of whether votes on resolutions at the United Nations (UN) exhibit similar characteristics (Binder and Lockwood Payton, 2022). This parameter is a prevalent method for evaluating coalitions using the index of voting cohesion (IVC) (Lijphart, 1963) or the Euclidean distance according to the Signorino and Ritter (1999) formula. It is important to note that this criterion is not applicable to non-members of the UN, but rather exhibits a pronounced geopolitical subjectivity (Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Palestine, Northern Cyprus, etc.) (O’Loughlin and Kolosov, 2017).

Finally, it is an inquiry into the manner in which the media disseminates a particular image of a nation. The lowest level of this phenomenon, though not insignificant for relations between states, is the dissemination of geopolitical perceptions through media outlets. This is the level that is referred to as “low geopolitics” (Kolossov, 2003; Dittmer and Dodds, 2008; Okunev, 2021).

The presented methodology is intentionally designed as universally as possible, that is, not only to assess the interaction of actors at the state level but also suprastate and sub-state. However, it should be recognized that it is impossible to assess the similarity of votes on United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolutions at a level other than the state level.

The following dates are considered pivotal for the geopolitical analysis of political attitudes toward Russia:

• 1990 marked the final year before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

• 1995 is widely regarded as the pinnacle of the post-Soviet crisis, marking a significant turning point in the region’s history.

• 2000 marked a significant political transition, with V. V. Putin’s rise to the presidency coinciding with a period of substantial post-Soviet economic and social crisis.

• 2016 is widely regarded as a critical juncture in Russia’s relationship with Europe, marking a significant shift in the geopolitical landscape.

• 2024 is the final relevant year cited in this publication.

The assessment was carried out on the basis of Russia’s closest environment, that is, countries within a distance of 1,000 km from Russia’s borders, as the belt of closest influence. This approach diverges from the common principle of neighboring countries. Some exceptions to this rule include Great Britain, France, and Tajikistan, which are located at a greater distance.

The objective of this study is not to provide a comprehensive account of the intricacies of bilateral relations with each nation. While these relations undoubtedly hold significance in specific domains, our analysis will prioritize a macro-level perspective. To that end, we will adhere to a general overview of international relations, focusing on the dates and select narratives that have been previously outlined.

4 Results

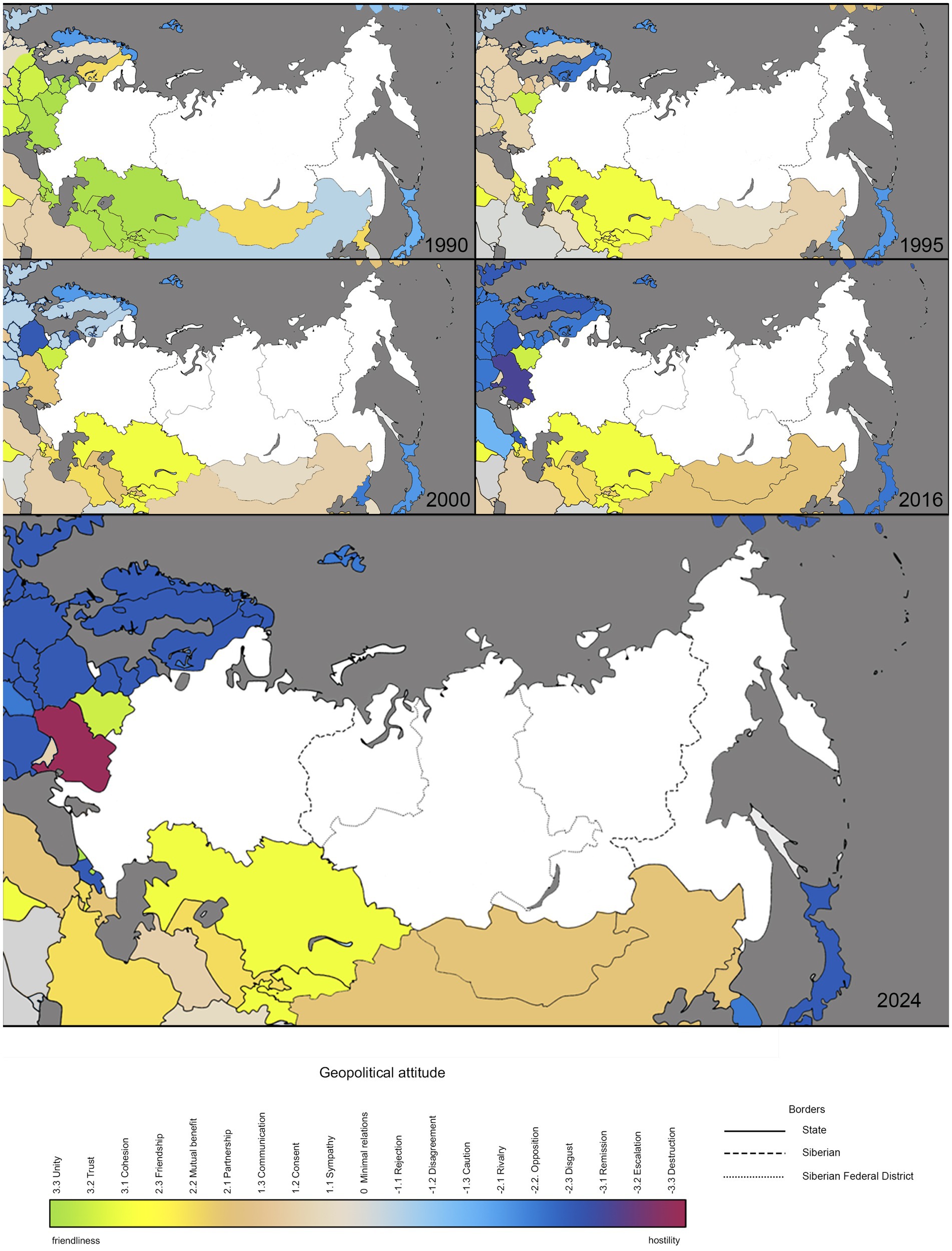

In 1990, the vast majority of the immediate neighborhood surrounding the perimeter of Russia’s contemporary borders exhibited a high degree of amicability. This was due to the presence of Soviet governing bodies that had united a number of formerly independent republics into a unified state entity. The Warsaw Pact Organization, a military alliance, was present in Eastern Europe. This allows for the organization to be evaluated with a rating of “3.1 Cohesion.” The establishment of a cohesive relationship with Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria was of paramount importance. The German Democratic Republic (GDR) would effectively cease to exist in 1990, and the border of friendliness on the western side would shift closer to Russia. Concurrently, the subjects in question were situated at a considerable distance from the territory of the hostiles. The most problematic geopolitical point for The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was China. After the split of the 1960s and the almost complete cessation of diplomatic relations, only the first cautious steps toward normalization of relations were taken. These consisted of the first mutual visits and meetings at the intergovernmental level. During the Soviet era, Mongolia’s relationship with the Soviet Union was marked by a significant degree of dependency, largely attributable to the military presence established under the provisions outlined in the “On Provision of Gratuitous Military Assistance to the Mongolian People’s Republic” treaty. However, by the year 1990, this period of Soviet influence was beginning to show signs of gradual weakening, ultimately leading to the complete withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country by 1993 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The geopolitical attitude of the surrounding countries toward Russia on a friendliness-hostility scale from 1990 to 2024.

The relationship between the two countries is also evaluated at a “2.2 Mutually Benefit“rating, a classification attributed to the unique conditions that govern their trade relations. Trade turnover between the USSR and the DPRK constituted more than 50% of the DPRK’s total foreign trade. The Soviet Union supplied raw materials to the DPRK’s enterprises, receiving up to 80% of manufactured products in return (Zabrovskaya, 2016). The establishment of official relations between the Soviet Union and the ROK did not occur until September 1990, which is categorized by the degree of “0 Minimum Relations.” By 1990, the practice of sanctions pressure, which had been employed in earlier periods of relations with the USSR, was no longer applied by the countries of Western Europe and the United States. In some countries (e.g., Austria), a consolidated vote was cast in the UNGA, and a positive information background prevailed in the media. The image of the USSR as a partner was broadcast (Kotelenets, 2013), which eventually resulted in the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to M. S. Gorbachev. An exception to this pattern was observed in the relationship between the USSR and Finland, where a system of clearing payments was implemented, analogous to special trade conditions (Sutyrin and Shlamin, 2015).

By 1995, a shift in political attitude became evident. The dissolution of the Warsaw Pact bloc and the escalation of anti-Russian sentiment among European nations have led to the emergence of a pronounced cluster of hostility. In the context of diplomatic relations with Poland, there was a precipitous decline, leading to a state of diplomatic warfare. This shift in the relationship was exemplified by the expulsion of the Russian military attaché, Vladimir Lomakin, from Poland in October 1993. A similar dynamic is observed in the case of Asian countries. The dissolution of the USSR prompts a transition in all Central Asian republics from the “3.3 Unity” stage to the “3.1 Cohesion” stage. Despite the stagnant state of bilateral relations between Mongolia and the United States, there has been a persistence in the preference for railroad transportation and copper smelting (Orlova, 2022). Conversely, there has been a marked warming of relations with the United States, as evidenced by Russia’s consistent participation in joint military exercises, designated “Peacemaker,” since 1993. A comparable warming is also occurring with the PRC, though it is only evident in the coherence of UNGA votes, which will intensify in subsequent periods. In the East Asian context, Japan emerges as a contentious issue, particularly with the escalation of tensions surrounding the Kuril Islands during the 1990s. This development significantly impacted Russian-Japanese relations, which, according to the classification system, is evaluated as “-2.1 Rivalry.” In essence, the political ties between the Russian Federation and the DPRK were suspended. A new treaty on friendship, good-neighborliness, and cooperation was concluded in 2000. Additionally, the strengthened visa regime in relation to democratic Russia results in an assessment of unfriendly relations. Therefore, warming of relations with the ROK is necessary.

Following the election of V. V. Putin as President of the Russian Federation in 2000, the initial period was characterized by an intensified visa regime toward the democratic Russian Federation. Initially, there was an effort toward rapprochement between Russia and European countries; however, this movement was rather unidirectional from Russia. A notable aspect of the 2000 election was the striking similarity in voting patterns observed among the UN, several Middle Eastern countries, and a number of European nations, including Bulgaria and Austria. Concurrently, the practice of expelling diplomats as an indication of enmity became more prevalent, particularly in the cases of Poland and Estonia. At that time, the Eurasian space was in the process of developing formats for international interaction, such as the Shanghai Five, which in 2001 transformed into the largest association in Eurasia, known as the SCO. The mechanisms of economic integration in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) had not yet been widely implemented, yet the practice of military exercises as a manifestation of the countries’ amicability had increased in comparison to previous years, as evidenced by the involvement of Moldova, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and others.

During the 2000s, the cluster of unfriendliness became more clearly delineated. The seminal events that transpired during this period included the terrorist attack in Beslan (2004) and the subsequent international reaction, Vladimir Putin’s Munich speech (2007), and the 5-day war (2008). Putin’s Munich speech (2007), the 5-day war (2008), and the coup in Ukraine (2014) are significant events that altered the international situation. The coup in Ukraine significantly changed the geopolitical position of Russia, resulting in the announcement of the policy of “turn to the East” (Oleynikov, 2021). However, this policy should more accurately be referred to after the APEC summit in 2012. It is imperative that we deliberate on more substantial, sustainable changes in the geopolitical position by 2016. Consequently, Russia is currently facing sanctions pressure due to its annexation of the Crimean peninsula, which has led to a deterioration in its political relations with European countries, reaching a point of “-2.2 Opposition,” and diplomats are expelled. Concurrently, integration processes in Eurasia are escalating. In 2015, the formation of the Eurasian Economic Union occurred, which, according to B. Ballassa’s typology, is structured as a common market. Ballassa’s typology has been demonstrated to significantly increase consolidation. Mongolia has historically maintained a commitment to the principles of international neutrality. However, since 2008, there has been a persistent pattern of military exercises in the Selenga region (formerly known as Darhan until 2010). These exercises have continued uninterrupted, despite the exertion of pressure by the international community on Mongolia following the escalation of international tensions in 2022. A similar policy of joint military exercises has been pursued with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since 2005, enabling the assessment of the stage “2.1 Partnership.” A notable exception is the ROK, where in 2014, the establishment of a visa-free regime occurred concurrently with the initiation of anti-Russian sanctions in 2015. Since then, the country has undergone a consistent expansion of the lists of prohibited goods and companies, which, according to the “-2.2 Counteraction,” should be regarded as a more substantial factor contributing to the country’s unfriendliness. The integration of countries within Greater Eurasia has become particularly robust. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), established in 2001, has evolved from a consultative platform to a full-fledged security integration association. Since 2005 and continuing to the present, regular military exercises, designated “Peace Mission,” have been conducted within the SCO, uniting even those nations engaged in territorial disputes: China, India, and Pakistan are the primary countries of concern (Yenikeyeff et al., 2024).

In 2022, the situation underwent a significant shift with the declaration of the Special Military Operation in Ukraine and the subsequent deepening of the rift between the collective West and Russia. The ongoing series of diplomatic disputes between Russia and other global powers, particularly the European Union and the United States, signifies a notable shift in the political climate toward Russia. This shift is characterized by a decline in the severity of sanctions imposed by these nations, as evidenced by the ROK’s decision to discontinue the expulsion of diplomats in its bilateral relations with Russia. The Mongolian–Chinese relationship has remained relatively stable, with a few notable exceptions (Bezrukov and Fartyshev, 2022; Bezrukov et al., 2022). While negotiations are underway with China to establish a free trade zone from 2022, which would raise the status of relations to “2.2 Mutual Benefit,” Mongolia has more actively pursued a policy of searching for a “third neighbor.” This implies a shift away from its immediate neighbors (Bedeski, 2006). Notably, Finland stands out as a particularly salient case study. Since Finland’s accession to the European Union in 1995, the bilateral relationship has undergone a gradual deterioration, culminating in the closure of the border, Finland’s integration into the NATO alliance, and the onset of diplomatic tensions by 2024.

The foundation for Russia and Syria’s bilateral relations is the 1980 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation. However, there has been no tangible progress in the direction of integration, as Syria’s aspirations to establish a free trade zone agreement with Russia, initially expressed in 2012, have yet to be realized. The 2016 agreement concerning the deployment of a Russian Federation aviation group on Syrian territory can be regarded as a military alliance. The present geopolitical climate is characterized by a pervasive sense of instability, particularly in relation to the countries of the Korean Peninsula and the Middle East. Despite the fact that the DPRK is one of the few countries that recognized the accession of new regions to Russia in September 2023, the parties remain cautious about joint military exercises. It is imperative to acknowledge that the political disposition exhibited by Russia is not reciprocal, as evidenced by the imposition of stringent sanctions by the UN against the DPRK.

Of the nations in question, Belarus is the most stable in relation to Russia because its geopolitical attitude has not experienced critical shifts in comparison to the attitude of other states. Since 1995, Belarus has gradually integrated with Russia, as evidenced by its involvement in numerous integration associations and the establishment of a union state in 1999.

5 Discussion

5.1 What does it mean for world?

Over the past three decades, there has been a marked increase in the level of confrontation on the Eurasian continent, accompanied by a shift in Russia’s role and involvement in geopolitical processes. During the 1990s, tensions were primarily confined to local actors (namely the Balkans, the Middle East, Iran, and Afghanistan), but contemporary geopolitical developments have led to Russia becoming a source of tension in Eurasia. This is primarily attributable to Russia’s internal consolidation during Vladimir Putin’s presidency, which commenced in the 2000s. Consequently, Russia once again assumed a significant role in international relations, thereby superseding its withdrawal from global politics during the 1990s.

The most stable system of international relations could be a situation where all countries are as friendly as possible. However, according to the neorealistic theory of international relations, this is not achievable. In other words, relations between all actors would be assessed as “3.3 Unity,” but this is rather a hypothetical situation (Lee et al., 1994). Contemporary dynamics in relation to Russia indicate an antithetical trend, suggesting a process of disintegration in the world system.

5.2 What does it mean for Russia?

A substantial shift in the political disposition of the immediate neighborhood is evident during the period under scrutiny, consequently precipitating a transformation in Russia’s geopolitical posture. A review of the geopolitical landscape reveals a notable shift in the distribution of friendly states between 1990 and 1995. In 1990, there was a significant presence of states that exhibited a friendly bloc, distributed in a westerly and southern direction. However, by 1995, this distribution had undergone a fragmentation due to variations in levels of friendliness. By 2000, this fragmentation had intensified, with rare exceptions of institutionalized forms of unfriendliness. In 2016, this dynamic shifted to a more hostile stage, marked by the imposition of sanctions of economic and political nature. This shift was further exacerbated by the announcement of the Special Military Operation in 2022, leading to the expulsion of diplomats, a measure previously only observed in the case of Russia.

The most significant shift in political stance was observed in the context of Ukraine, where there was a transition from a moderate level of unity to a state of extreme animosity. Concurrently, in Central Asia, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (“Tashkent Pact”), a military alliance, plays a pivotal role in consolidating the region. In the 1990s, the consolidation of the CIS countries on this issue disintegrated. However, following 2000, with its expansion, it strengthened on the contrary.

Consequently, during the period under scrutiny, a pivotal shift in political attitudes toward Russia emerged. However, in the interest of national interests, the escalation in the amicability of intra-continental states should be commensurate with the decline in sentiments observed among Western bloc countries. Presently, a symmetrical process of this nature is not underway. The foreign policy shift toward the East, characterized as a “long turn to the East,” primarily affects the “de-westernization” of Russia (Savchenko and Zuenko, 2020). Concurrently, the formation of a stable coalition in the Eurasian space is progressing at a gradual pace. The strengthening of integration processes in Eurasia during the described period is indicative of the revival of the geopolitical concept of “Heartland.” A significant advancement in the direction of deepening integration processes within the SCO could be the formalization of an agreement establishing a comprehensive military alliance, or the initiation of a more pronounced movement toward economic integration, which might include the establishment of a fully operational free trade zone among all SCO member states.

5.3 Geopolitical position of Siberia

A pivotal aspect of Russia’s foreign policy agenda pertains to the geopolitical positioning of Siberia and the Far East. These regions have assumed heightened significance in the context of escalating international tensions. In the context of Soviet geopolitics, Siberia and the Far East were strategically positioned in close proximity to China, a nation regarded as hostile by the Soviet regime. However, in the post-Soviet era, a notable shift has emerged, marked by the formation of a Greater Eurasia concept. This geopolitical vision, which places significant emphasis on the integration of Siberia as its central element, underscores the strategic importance of the region in the contemporary geopolitical landscape (Fartyshev, 2021). The concept of “Siberianization” has garnered significant interest, with proponents advocating for the relocation of the Russian capital to the country’s interior, a proposal that is underpinned by substantial geostrategic rationale (Karaganov and Kozylov, 2025). Concurrently, the strategic relocation of capital inland, driven by concerns over security, may induce a phenomenon of “self-caging” (Boedeltje and van Houtum, 2020). This dynamic can engender not only political distance but also physical and social distance from numerous nations, including those that are not overtly hostile. Concurrently, the accelerated emergence of robust economic hubs in Siberia, along with the fortification of cross-border connections through the establishment of transportation corridors in the southern direction, holds immediate practical relevance in the consolidation of the Eurasian partnership (Bezrukov, 2018; Urantamir et al., 2024).

It is imperative to acknowledge the highly dynamic nature of political attitudes, which are predominantly influenced by power decisions and domestic political events. This dynamic nature renders the presented structure highly flexible. A case in point is the shift in Argentine power in 2023, which led to a radical realignment of the nation’s foreign policy. The country’s strategic shift, characterized by a notable transition from aspirations of joining the BRICS alliance to a pronounced strengthening of its foreign policy reliance on the United States and a notable “dollarization” of the economy, exemplifies the complex interplay between domestic political dynamics and international economic factors. The most vulnerable points are the countries in the immediate vicinity of both Russia and Siberia, which have the potential to abruptly change their foreign policy course in a revolutionary way, for example, in Kazakhstan, or in an evolutionary way, for example, in Mongolia. These two neighboring countries are located at the core of the continent, and the consolidation dynamics in the Eurasian space are contingent on the policies of these countries. The geopolitical implications of the Greater Eurasia project, as interpreted through the lens of Russian policy toward these two countries, are of particular significance. The project’s implications, when analyzed through the framework of geopolitical dynamics, suggest a potential escalation in the level of Russo-Western confrontation, as previously outlined.

5.4 Limits of approach

The presented overview of international relations and geopolitical power as key geopolitical factors enables the quantitative assessment of the complex and multifaceted concept of geopolitical position, in addition to demonstrating the situation in dynamic terms. Simultaneously, the geopolitical analysis methodology that has been presented has its limitations, which are as follows:

The issue of political attitudes that are not reciprocal has been a subject of considerable debate. The presented methodology demonstrates bilateral relations between nations in a symmetrical manner. However, in practice, instances of asymmetry can frequently be observed, particularly at the levels that approximate the category of “Minimum Relations.” For instance, the image of Russia in the media of some African countries may be significantly more favourable, while Russia’s attitude toward them is indifferent, as in the case of Zimbabwe (Gadzikwa et al., 2023), or, conversely, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. In the context of the present study, it is observed that states which have previously experienced military coups and are now cooperating with Russian private military organizations, due to the weakness of the state apparatus, have been found to give Russia only positive coverage in the media (Issaev et al., 2022). However, it is also noted that these states do not always support Russia in votes on UNGA resolutions. Furthermore, it should be noted that sanctions, as a component of international relations, do not invariably exhibit symmetry.

The issue of linearity in scale assessments is a subject that has been the subject of much debate and research. As with other friendliness-hostility scales previously described, non-linear mutual relations between countries can, in fact, occur. This phenomenon can emerge in the context of internal divisions within deep integration associations, which concurrently give rise to antagonistic actions in bilateral relations.

The issue of evaluating the relative importance of various factors, which can be characterized as both friendly and hostile, remains a subject of ongoing research and analysis. In reality, it is difficult to ascertain which factor—economic, military, cultural, or any other—exerts the greatest influence. This phenomenon is exemplified by the potential for sanctions or trade wars against political and military allies, as demonstrated in the aforementioned example (Pape, 1998). Political attitudes are de facto multidirectional, suggesting the need to identify potential non-linear scales for their measurement.

The issue of informal manifestations of amiability and antagonism. A variety of institutions do not align with the established framework for evaluating friendliness and hostility, rendering them challenging to assess. The most salient instances of this phenomenon pertain to cultural activities, such as student exchanges, official visits, and telephone communications, as well as language policy and educational initiatives (including the prohibition of the use of Russian, the establishment of language police, or the expansion of Russian-language schools). These activities may not be formally institutionalized within the context of bilateral relations, as evidenced by the implementation of “language patrols” in Kazakhstan (Topchiev and Khrapov, 2023).

6 Conclusion

A synthesis of the extant research reveals four fundamental conclusions.

The political-geographical approach to the analysis of international coalitions provides a generalized understanding of the global or regional landscape, facilitating the integration of regional and sectoral international studies into a unified systematic structure of political space. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the existence of numerous unique instances of international relations, which are examined through the lens of specialized academic research.

The most salient, albeit not exhaustive, markers of unfriendliness, apart from direct military actions, are currently expulsions of diplomats and declarations of “persona non grata,” the narrative of contested territories, sanctions policy, dissimilarity of votes in the UN, and negative image in the media. Markers of friendliness include the presence of joint governing bodies, an agreement on economic or military-political integration, joint military exercises, support in UN votes, and positive connotations in the media. The presence or absence of this or that marker engenders a multivariant gradation of the essence of friendliness—unfriendliness of states.

Over the period under consideration, Russia’s geopolitical position has undergone significant shifts and fluctuations, attributable to the volatility of Russia’s foreign policy course and the policy of Western states toward Russia itself. These states have repeatedly demonstrated an escalating degree of unfriendliness in their signals and actions. The primary outcome of the 30-year span was the emergence of two “flanks of unfriendliness” from the western and eastern regions of Russia, accompanied by the parallel strengthening of consolidation within the intra-Eurasian space. However, this consolidation lacks sufficient symmetry to match the escalating tensions.

Siberia is located in the center of a cluster of friendly countries. This geographic position connects the political space of Greater Eurasia, yet it also creates a “gaping hole” of underdevelopment and abandonment, with the exception of a few specific locations.

The present approach enables a comprehensive examination of the interrelationships among subjects, encompassing a range of political dimensions, economic parameters, political aspects, and geographical data. The political dimensions encompass the focus, representativeness, and status of foreign visits by the political elite, the activities of foreign NGOs, and the representation of countries and regions in foreign policy, regulatory legal acts, and strategic planning documents. The economic parameters include the volume of foreign trade, the level of foreign investment, the level of international cooperation, and the external dependence of production chains. The geographical data encompass the remoteness of countries from each other, economic distance, and the degree of infrastructural and natural barriers along borders.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Research funded by Russian Science Foundation Grant No. 23-77-10048, https://rscf.ru/project/23-77-10048/.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bayer, M., and Hauk, S.. (2023). Global militarisation index 2023. Bonn: Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (BICC). Available online at: https://bicc.de/Publications/Report/Global-Militarisation-Index-2023/pu/14293 (accessed July 30, 2025).

Bedeski, R. (2006). Mongolia as a modern sovereign nation-state. Mongol. J. Int. Aff. 13, 77–87. doi: 10.5564/MJIA.V0I13.10

Bezrukov, L. A. (2018). The geographical implications of the creation of “Greater Eurasia.”. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 39, 287–295. doi: 10.1134/S1875372818040017/METRICS

Bezrukov, L. A., and Fartyshev, A. N. (2022). Features of Mongolian foreign trade: risks for Russia. World Econ. Int. Relat. 66, 101–109. doi: 10.20542/0131-2227-2022-66-3-101-109

Bezrukov, L. A., Fartyshev, A. N., and Altanbagana, M. (2022). Economic and geographical problems in interactions between Mongolia and eastern Russia in foreign commodity markets. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 43, S9–S14. doi: 10.1134/S1875372822050055

Binder, M., and Lockwood Payton, A. (2022). With frenemies like these: rising power voting behavior in the UN general assembly. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 381–398. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000538

Boedeltje, F., and Houtum, H.van. (2020). The lie of the wall. Peace Rev. 32, 134–139. doi: 10.1080/10402659.2020.1836303

Dittmer, J., and Dodds, K. (2008). Popular geopolitics past and future: fandom, identities and audiences. Geopolitics 13, 437–457. doi: 10.1080/14650040802203687

Fartyshev, A. N. (2017). Geopolitical and geoeconomical position of Siberia: modelling and estimation. Vestn. Saint Petersburg Univ. Earth Sci. 62, 300–310. doi: 10.21638/11701/spbu07.2017.306

Fartyshev, A. N. (2021). Siberia in conception of Greater Eurasia. Bull. Irkutsk State Univ. Ser. Polit. Sci. Rel. Stud. 37, 40–49. doi: 10.26516/2073-3380.2021.37.40

Fartyshev, A. N. (2022). Quantitative methods in Russian geopolitical researches. Polit. Sci., 4:18–40. doi: 10.31249/poln/2022.04.01

Fartyshev, A. N., and Pisarenko, S. V. (2024). “Measuring unfriendliness and remoteness: dynamics of geopolitical processes in Eurasia” in Geography, identity, and politics: concepts, theories, and cases in geopolitical analysis, international workshop on geopolitics and political geography. eds. N. Morgado and M. Kopanja (Belgrade: University of Belgrade), 203–220.

Foa, R. S., Mollat, M., Isha, H., Romero-Vidal, X., Evans, D., and Klassen, A. J. (2022). A world divided: Russia, China and the west. Cambridge: Bennett Insitute for Public Policy, University of Cambridge.

Gadzikwa, W., Mukaripe, T., and Sauti, L. (2023). “Depictions of the Ukraine–Russia conflict in the Zimbabwean press” in The Russia-Ukraine War from an African Perspective (Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG), 269–292.

Goldstein, J. S. (1992). A conflict-cooperation scale for WEIS events data. J. Confl. Resolut. 36, 369–385. doi: 10.1177/0022002792036002007

Holsti, O. R. (1962). The belief system and national images: a case study. J. Confl. Resolut. 6, 244–252. doi: 10.1177/002200276200600306

Holsti, K. J. (1963). The use of objective criteria for the measurement of international tension levels. Background 7, 77–95. doi: 10.2307/3013638

Issaev, L., Shishkina, A., and Liokumovich, Y. (2022). Perceptions of Russia’s ‘return’ to Africa: views from West Africa. S. Afr. J. Int. Aff. 29, 425–444. doi: 10.1080/10220461.2022.2139289

Karaganov, S. A., and Kozylov, I. S. (2025). Eastward turn 2.0, or “Sibiriazation” of Russia. Rossiya v globalnoi politike 23, 221–229. doi: 10.31278/1810-6439-2025-23-1-221-229

Klingberg, F. L. (1941). Studies in measurement of the relations among sovereign states. Psychometrika 6, 335–352. doi: 10.1007/BF02288590

Kolossov, V. (2003). “High” and “low” geopolitics: images of foreign countries in the eyes of Russian citizens. Geopolitics 8, 121–148. doi: 10.1080/714001015

Kolossov, V., and Scott, J. (2013). Selected conceptual issues in border studies. Belgeo 1. doi: 10.4000/BELGEO.10532

Koopman, S., Dalby, S., Megoran, N., Sharp, J., Kearns, G., Squire, R., et al. (2021). Critical geopolitics. Polit. Geogr. 90:102421. doi: 10.1016/J.POLGEO.2021.102421

Kotelenets, E. A. (2013). Image of Soviet Union in the world: factors and dynamics of perception. RUDN J. Russ. Hist. 3, 76–90.

Lee, S. C., Muncaster, R. G., and Zinnes, D. A. (1994). “The friend of my enemy is my enemy”: modeling triadic internation relationships. Synthese 100, 333–358. doi: 10.1007/BF01063907

Lijphart, A. (1963). The analysis of bloc voting in the general assembly: a critique and a proposal. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 57, 902–917. doi: 10.2307/1952608

Maoz, Z. (1982). Paths to conflict: international dispute initiation, 1816-1976. Westview Press. Available online at: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1971149384861932713 (accessed August 1, 2025).

Morgado, N., and Hosoda, T. (2024). A pact of iron? China’s deepening of the Sino-Russian partnership. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1446054. doi: 10.3389/FPOS.2024.1446054

Morgan, T. (2021). Peace as a composite indicator: the goals and future of the global peace index. Pathways Peace Secur. 2, 43–56. doi: 10.20542/2307-1494-2021-2-43-56

Nesmashnyi, A. D., Zhornist, V. M., and Safranchuk, I. A. (2022). International hierarchy and functional differentiation of states: results of an expert survey. MGIMO Rev. Int. Relat. 15, 7–38. doi: 10.24833/2071-8160-2022-OLF2

O’Loughlin, J., and Kolosov, V. (2017). Building identities in post-soviet “de facto states”: cultural and political icons in Nagorno-Karabakh, South Ossetia, Transdniestria, and Abkhazia. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 58, 691–715. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2018.1468793

Oleynikov, I. V. (2021). Designing contacts: the past and the present in international cooperation between the regions of Siberia and the Republic of Korea. Bull. Irkutsk State Univ. Ser. Polit. Sci. Rel. Stud. 38, 51–57. doi: 10.26516/2073-3380.2021.38.51

Orlova, K. V. (2022). Russia—Mongolia: a century of friendship and cooperation. Orient. Stud. 14, 888–899. doi: 10.22162/2619-0990-2021-57-5-888-899

Palmer, G., D’Orazio, V., Kenwick, M., and Lane, M. (2015). The MID4 dataset, 2002–2010: procedures, coding rules and description. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 32, 222–242. doi: 10.1177/0738894214559680

Pape, R. A. (1998). Why economic sanctions still do not work. Int. Secur. 23:66. doi: 10.2307/2539263

Pestsov, S. K., and Volynchuk, A. B. (2020). Tensions in international relations: conceptual basis for comparative research. Comp. Polit. Russ. 11, 12–24. doi: 10.24411/2221-3279-2020-10033

Pototskaya, T. I. (2018). Geopolitics of Russia in the post-soviet space. Smolensk, Russia: IPR Media.

Richardson, L. F. (1960). Arms and insecurity: a mathematical study of the causes andOrigins of war. Pittsburgh: Boxwood.

Safranchuk, I. A., Nesmashnyi, A. D., and Chernov, D. N. (2023). Africa and the Ukraine crisis: exploring attitudes. Russ. Glob. Aff. 21, 159–180. doi: 10.31278/1810-6374-2023-21-3-159-180

Savchenko, A. E., and Zuenko, I. Y. (2020). The driving forces of Russia’s pivot to east. Comp. Polit. Russ. 11, 111–125. doi: 10.24411/2221-3279-2020-10009

Signorino, C. S., and Ritter, J. M. (1999). Tau-b or not tau-b: measuring the similarity of foreign policy positions. Int. Stud. Q. 43, 115–144. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00113

Sutyrin, S. F., and Shlamin, V. A. (2015). Russia–Finland economic cooperation: the past, the present, and the future. St Petersburg Univ. J. Econ. Stud., 1:122–129.

Terechshenko, Z. (2020). Hot under the collar: a latent measure of interstate hostility. J. Peace Res. 57, 764–776. doi: 10.1177/0022343320962546

Timofeev, I. (2019). Sanctions’ policy: unipolar or multipolar world? Int. Organ. Res. J. 14, 9–26. doi: 10.17323/1996-7845-2019-03-01

Timofeev, I. N. (2023). Policy of sanctions in a changing world: theoretical reflection. Polis. Polit. Stud. 2, 103–119. doi: 10.17976/JPPS/2023.02.08

Topchiev, M. S., and Khrapov, S. A. (2023). The media’s portrayal of the “the own–other/other–other–alien–enemy” opposition as a political and sociocultural tool for establishing the emerging ethnic identity of the Republic of Kazakhstan. South Russ. J. Soc. Sci. 24, 21–34. doi: 10.31429/26190567-24-2-21-34

Urantamir, G., Altanbagana, M., Tseyenkhand, P., and Nandin-Erdene, A. (2024). Regional SWOT analysis along the Krasnoyarsk—Uliastai—Lanzhou vertical axis. Mongol. J. Geogr. Geoecol. 61, 31–44. doi: 10.5564/MJGG.V61I45.3353

Wike, R., Fetterolf, J., Fagan, M., and Gubbala, S. (2022). International attitudes toward the U.S., NATO and Russia in a time of crisis|pew research center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2022/06/22/international-attitudes-toward-the-u-s-nato-and-russia-in-a-time-of-crisis/ (accessed July 30, 2025).

Wolfers, A. (1962). Discord and collaboration. Essays on international politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Wright, Q. (1955). The peaceful adjustment of international relations: problems and research approaches. Soc. Iss. 11, 2–12. doi: 10.1111/J.1540-4560.1955.TB00300.X

Yenikeyeff, S., Lukin, A., and Novikov, D. (2024). The Shanghai cooperation organisation in new geopolitical realities. Int. Organ. Res. J. 19, 1–29. doi: 10.17323/1996-7845-2024-01-06

Keywords: Russia, Siberia, geopolitical attitudes, Greater Eurasia, political geography, geopolitical landscape, geopolitics

Citation: Fartyshev AN (2025) The geopolitical landscape and Russia’s position in multidimensional political space. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1651223. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1651223

Edited by:

Carlos Leone, Open University, PortugalCopyright © 2025 Fartyshev. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arseniy Nikolaevich Fartyshev, RmFydHlzaGV2LmFuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Arseniy Nikolaevich Fartyshev

Arseniy Nikolaevich Fartyshev