- Center for Economic Education, Columbus State University, Columbus, GA, United States

This study examines the market for Hunter Biden’s art, with an eye toward the art’s value as a rent seeking device that benefitted Hunter and the wider Biden family. More specifically, this study asserts that the usefulness of Hunter Biden’s art sales as a rent- or transfer-seeking tool can be established in any one of three ways. First, Hunter Biden’s paintings have not generally been judged positively. In fact, the quality of his artwork has been widely panned by esteemed art critics from around the globe, particularly in relation to transaction prices. Second, although information on the buyers of Hunter Biden’s art has, by design, been hidden from the public, one of the two known buyers received a prestigious presidential appointment from then-U.S. President Joseph Biden shortly after making a purchase, clearly giving the sale a privilege seeking appearance. Third, although data on Hunter Biden’s art sales are relatively scant, some quantitative evidence is provided in this study indicating that sale prices of the art and U.S. President Joseph Biden’s monthly approval ratings are positively and significantly correlated, a result that is consistent with the public choice theory of rent seeking.

1 Introduction

In the fall of 2020, just as his father, former U.S. Senator and Vice President of the U.S. Joseph R. Biden, was ascending to the Presidency of the United States, Robert Hunter Biden was being introduced to the art world as its latest phenom. Having been formally trained in law, not art, Hunter Biden’s life had, up to this point, taken many twists and turns and was not without controversy. In the years leading up to the 2020 election, bi-coastal Hunter Biden—an admitted alcoholic and drug addict—frequently purchased crack cocaine on the streets of Washington, DC and cooked his own inside his Los Angeles hotel room (Biden, 2021). During this period, his marriage fell apart, and he effectively disappeared from the lives of his loved ones while moving between low budget motels, often accompanied by prostitutes. Hunter Biden’s life at this point had become so reckless that on multiple occasions he faced the barrel of a gun (Biden, 2021).

By his own account, Hunter Biden has been in addiction recovery since early 2019. Penning his memoir helped that process (Biden, 2021). Other accounts describe Hunter Biden’s painting, a hobby that became known to the wider public while writing his memoir, as having an urgent purpose—that of saving his soul from his prior torment (Kuspit, 2021). According to Kuspit (2021), Biden’s “art therapy – his therapeutic use of art – has served him well” as a creative outlet for dealing with his suffering by making him more introspective than he had been in the past. That art also served another purpose, that of earning him almost $1.5 million from sales of it that occurred from 2020 to 2024, a period including much of his father’s single term as U.S. President.

This study examines the market for Hunter Biden’s art, with an eye toward its value as a rent seeking device that benefitted Hunter and the wider Biden family.1 More specifically, this study asserts that the usefulness of Hunter Biden’s art sales as a rent- or transfer-seeking tool can be established in any one of three ways. First, Hunter Biden’s paintings did not hit the art world to critical acclaim. In fact, the quality of his artwork has been widely panned by esteemed art critics from around the globe, many of whom described their dismay at both the asking and transaction prices. Second, although information on the buyers of Hunter Biden’s art has, by design, been hidden from the public, the two known buyers are supporters of both Joseph Biden and the Democratic Party. One of these buyers received a prestigious presidential appointment shortly after making a purchase, clearly giving the sale a privilege seeking appearance. Third, although data on Hunter Biden’s art sales are relatively scant, some quantitative evidence is provided in this study indicating that sale prices of the art and U.S. President Joseph Biden’s monthly approval ratings are positively and significantly correlated. This result is consistent with the public choice theory of rent seeking.

Before turning to the public choice explanation of Hunter Biden’s art sales, the second section of this study provides a primer on his life and controversies, followed by a description, in section three, of the style and quality of his art. The fourth section of this study discusses the market for Hunter Biden’s art, after which, in section five, the public choice analysis summarized above is presented. The sixth section offers some concluding comments.

2 Hunter Biden’s life and times: a primer

Robert Hunter Biden was born on 4 September 1970 to Joseph R. Biden and Neilia Hunter Biden. Since birth, Hunter’s life has been defined by tragedy and controversy extending to the present day. In 1972, while traveling with his mother, older brother Beau and younger sister Naomi, he was involved in a crash that killed his mother and Naomi, and that left Hunter and Beau seriously injured and facing months-long hospital stay.2 During their hospital recovery, Hunter’s father was sworn in as U.S. Senator representing their home state of Delaware. This would begin a more than 40-year Senate career for the elder Biden, who would famously commute by train between Delaware and Washington, D.C. each day, departing in the early morning and returning late in the evening, leaving little time for his Delaware-based family.

In terms of educational training, Hunter Biden attended Archmere Academy in Delaware and later graduated from Georgetown University with a degree in history. One year after graduation, in 1993, he married Kathleen Buhle. From there he entered Georgetown University’s law school, but after 1 year he transferred to Yale Law School. He graduated from Yale in 1996 and began his professional career as a consultant for the banking concern MBNA, rising to executive vice president by 1998 (Entous, 2019). After leaving MBNA and serving a brief stint at the United States Department of Commerce (Peligri, 2014), in 2001 Hunter Biden co-founded the lobbying firm of Oldaker, Biden and Belair (Schreckinger, 2019).3

After 5 years with the lobbying firm Hunter Biden and his uncle James Biden utilized an $8 million promissory note to buy Paradigm Global Advisors, an international hedge fund that was tied to the controversial Stanford Financial Group (Kamalakaran and Daga, 2009; Schreckinger, 2019). In 2008, just 2 years before this enterprise ended operation, Hunter Biden founded Seneca Global Advisors, a consultancy firm that 1 year later was folded into the similarly named Rosemont Seneca Partners (Schreckinger, 2019; Yu et al., 2019; Kessler, 2022).4 Between 2013 and 2018, Rosemont Seneca Partners was paid $11 million, $3.8 million of which was paid by CEFC China Energy, an oil and gas company with close ties to the Chinese Communist Party, with another block of money coming from Burisma Holdings in Ukraine (Chen and Lopatka, 2017; Viser, 2022; Winter et al., 2022).

In May of 2013, after being granted an age-related waiver and a waiver for a past drug-related incident, Hunter Biden’s application to join the U.S. Navy Reserve was accepted and he was placed in a program allowing a limited number of applicants with desirable skills to receive commissions and serve in staff positions (Nelson and Barnes, 2014; Ziezulewicz, 2019). However, routine urinalysis conducted on his first weekend of duty revealed cocaine use, and he was discharged administratively in February of 2014 (Ziezulewicz, 2019; Homan, 2020). Hunter Biden then joined the board of Burisma Holdings in April of 2014, putting him in the sphere of Mykola Zlochevsky, the owner of the company who faced charges of money laundering (Risen, 2015; Bullough, 2017; Sonne et al., 2019). Hunter Biden was compensated up to $50,000 per month for his board service (Vogel, 2019; Vogel and Mendel, 2019), meaning that he collected $3 million over his five-year service despite not having any prior experience in the energy sector. The company’s location in Ukraine, which was in Vice President Joseph Biden’s portfolio during the Barack Obama Administration (2009–2015), only added to the controversy created by Hunter Biden’s placement on the company’s board (Braun and Berry, 2019; Cullison, 2019; Entous, 2019; Sonne et al., 2019).5

At the end of 2018, Hunter Biden came under federal criminal investigation related to alleged tax violations and money laundering laws in his dealings in China and other countries (Perez and Brown, 2020). Unable to establish enough evidence for a money laundering prosecution, the FBI chose to focus solely on the tax law issues (Mangan, 2020; Wise, 2020).6 As the investigation into Hunter Biden progressed, he was indicted in Delaware on three federal firearms-related charges in mid-September of 2023 (Whitehurst, 2023), with a trial set for June of 2024 (Hawkinson, 2024), while in early December of 2023, he was indicted in California on nine tax charges (Pitas and Whitcomb, 2023), with a trial ultimately set for September of 2024 (Hawkinson, 2024). In the middle of June of 2024, Hunter Biden was found guilty on three felony charges for federal gun violations (Stein et al., 2024).7 Two months later he pled guilty to the nine tax charges (Brown and Yilek, 2024). Hunter Biden was scheduled for sentencing on two separate court dates, one for each case, both in the middle of December of 2024. However, on the first day of December of 2024, his father, U.S. President Joseph Biden, controversially issued a full and unconditional pardon of his son.

3 Hunter Biden’s art: its style and critiques

Hunter Biden selected the New York-based Georges Bergès Gallery to display and manage the sale of his art. Calling the exhibition The Journey Home (Angeleti, 2021), the Bergès Gallery categorized his paintings as photographic, mixed-media and abstract works on canvas, yupo paper, wood and metal, while in terms of style it noted that his work integrates oil, acrylic, ink and prose to create unique experiences (Sfondeles and Thompson, 2021). The collection ranges from more abstract paintings laid over images Hunter Biden photographed around Los Angeles to pieces that consist of 1,000 meticulously painted dots or blocks of solid color (Fox, 2021). According to Fox (2021), Hunter Biden usually starts a piece by tinkering with the colors, which in some cases come from alcohol ink that can be forever manipulated. He allows the ink to develop before layering on more on top, a process that takes hours (Fox, 2021). On some occasions he pours the ink directly onto the paper, then uses sponge brushes to mix it around, while on other occasions he sprays or manipulates it by blowing through a straw. Hunter Biden claims his art is influenced by American writer Joseph Campbell, which is why it often repeats symbols like snakes, birds and solo silhouettes (Fox, 2021). Fox (2021) adds that many pieces are saturated with color, such as Malibu blues, rich rust, aquas and greens, and a common thread of gold leaf throughout. According to well-known critic Donald Kuspit, Hunter Biden plays a keyboard of colors in creating his art, while artist Shepard Fairey describes Hunter Biden’s work as graphic and painterly (Kuspit, 2021; Fox, 2021). Most, if not all, of the qualities described above can be seen in the samples of Hunter Biden’s art.

When news of Hunter Biden’s entry into the art world became public, media outlets sought advice from well-known art critics as to the quality of the work. Sfondeles and Thompson (2021) reached out New York art critic Geoffrey Young, national art critic Ben Davis, London art critic Tabish Khan and Jon Ploff, an art professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, for their opinions of the art. A contemporaneous report by Cillizza (2021) based its information on the opinions of Sebastian Smee, the Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic for The Washington Post. Although New York-based art critic Geoffrey Young explained that it exceeded his expectations, he added that the posted price range—$75,000–$500,000 per piece—was exceedingly high, particularly given The New York Times’ description of Hunter Biden as an undiscovered artist (Sfondeles and Thompson, 2021). National art critic Ben Davis echoed Young’s assessment, pointing out that the price points for Hunter Biden’s art place it among the top tier for emerging artists (e.g., Dana Schutz, Alice Neel and Stanley Whitney) who have sold work for around $500,000 (Sfondeles and Thompson, 2021). The critics joined John Ploff, an art professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and London art critic Tabish Khan in concluding that most of the price of Hunter Biden’s art owed to the connection his last name accompanies (Sfondeles and Thompson, 2021).

Cillizza (2021) reached out to Sebastian Smee, the Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic for The Washington Post. When asked by Cillizza (2021) whether Hunter Biden’s art is any good, Smee flatly responded “not really,” before adding that some of the work looks technically impressive but its eclectic style leaves its viewers feeling very little, if anything, making the art seem mostly like an afterthought. According to Smee, Hunter Biden’s art is not compelling enough to be shown in a professional gallery (Cillizza, 2021). As a portfolio, Smee summarized Hunter Biden’s art as eclectic, and that in some individual cases it is pretty and well-made, while for the most part it is also overloaded with ideas that are not well integrated into the work itself (Cillizza, 2021). Put differently, although the colors are pretty and the patterns are nice, Hunter Biden’s art offers no real urgency or underlying poetry, and there is no sense of a powerful personality being concentrated and funneled through the painting (Cillizza, 2021).

4 The market for Hunter Biden’s art, 2020–2024

According to testimony provided by art gallerist Georges Bergès to the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, Bergès was introduced to Hunter Biden by Lanette Phillips, a Hollywood video producer who had previously hosted fundraisers for Hunter Biden’s father, former U.S. President Joseph Biden (Comer, 2024). At some point after their meeting, Hunter Biden entered into an arrangement with Bergès for the delivery and sale of the former’s artwork through Bergès’ art gallery in New York City. Upon delivery, Bergès would price Hunter Biden’s art pieces up to $500,000, although the average price settled at around $85,000 (Vincent, 2025).

During 2020, Bergès made multiple attempts, all unsuccessful, to convince Elizabeth Hirsh Naftali, owner of a commercial real estate company in Los Angeles, to be the first to purchase a piece of Hunter Biden’s artwork. It was not until December of 2020, about 1 month after Joseph Biden defeated incumbent U.S. President Donald J. Trump to become the 46th President of the United States, that the first sale of Hunter Biden’s artwork (to an unnamed buyer and at an unspecified price) occurred (Comer, 2024; Solomon, 2024). In February of 2021, about 1 month after Joseph Biden’s inauguration as the 46th U.S. President, Naftali purchased her first piece of Hunter Biden’s art at a price of $42,000 (Comer, 2024; Solomon, 2024). About 22 months later, in December of 2022, Naftali spent another $52,000 in purchasing more of Hunter Biden’s art (Comer, 2024; Solomon, 2024).

An artist-gallery contract dated 1 September 2021 that was eventually released to the public revealed that Bergès assisted in the sale of 11 of Hunter Biden’s paintings to a single buyer for the sum of $875,000. Although the buyer’s name was not revealed in the contract, it later became public that the buyer was Hollywood attorney and Democratic donor Kevin Morris (Vincent, 2025; Comer, 2024; Solomon, 2024). At some point during 2023, Hunter Biden’s art sales had reached a total of $1.379 million, and Morris’ purchase still accounted for more than 50% of total sales revenue (Schwartz, 2023). By the time Hunter Biden made his 27th and final sale of art in 2024, which was the only sale that occurred during 2024, for $36,000, he had accumulated about $1.5 million in sales yet still had an inventory of almost 200 unsold pieces (Crane Christenson, 2025; Vincent, 2025). These inventory pieces were kept in a Pacific Palisades storage facility that was destroyed by the December 2024 wildfires in Los Angeles (Vincent, 2025). One month later, his father, Joseph Biden, exited the White House for the final time as the 46th U.S. President.

5 Hunter Biden’s art sales as rent seeking

The professional critics who assessed Hunter Biden’s art negatively also suggested that sales of his art would succeed (or fail) because of his surname. Thus, without formally stating such, the critics were taking a public choice view on the prospective sales of Hunter Biden’s art with an eye toward their usefulness as a rent seeking device. The remaining subsections of this portion of the study formalize their instinctive view, with particular attention to (1) the lack of quality of the paintings, (2) the privilege seeking nature of the sales, and (3) the relationship between the transaction prices and President Joseph Biden’s job approval ratings. Before turning to this three-pronged public choice approach, a brief review of the public choice theory of rent seeking is provided.

5.1 Public choice theory of rent seeking

The now well-known theory of rent seeking has, beginning with Tullock (1967), Krueger (1974), and Posner (1975), augmented the traditional notion of deadweight losses due to monopoly in economic theory. The important series of papers expanded the notion of a monopoly loss to include competing resource investments within the political process to obtain monopoly rents. The basic idea of rent seeking has since expanded to include competitive lobbying for any number of privileges and resources that can be conferred or transferred by government (Tullock, 1989), which as an activity is expected to vacillate whenever government functions and funding are shifted between the various levels of government (Mixon Jr et al., 1994; Mixon and Ladner, 1998).8 Moreover, wherever rent-seeking activity occurs, it is expected to include both overt monetary forms, such as campaign contributions, and more subtle in-kind payments related to fancy restaurant dining, golfing excursions, limousine services, preferential employment and/or real estate transactions, massage services, sporting event suites and much more (Mixon Jr et al., 1994; Mixon, 1995; Laband and McClintock, 2001).

Although most inquiry into rent seeking in the political process focuses on lobbying of legislators, U.S. Presidents have many constitutional and other powers that place them at the center of lobbying activity. These include, but are not limited to, the presidential veto power and the constitutional authority of appointment (e.g., presidential cabinet members, U.S. ambassadors, Federal Reserve governors). Having these constitutional powers, however, might not be sufficient for a sitting president to confer privileges to individuals or groups. A president’s authority to effectively deploy them, particularly in a way that might be perceived as controversial, depends upon his or her political authority or capital. As Schier (2011) explains, the concept of political capital, whose components in the presidential context include congressional support, public approval of the president’s job conduct and electoral margin, captures many of the aspects of a president’s political authority.9 Empirical analyses support the notion that a president’s stock of political capital and his or her ability to effectively utilize it are boosted by his or her job approval ratings (e.g., Gelpi and Grieco, 2015; Christenson and Kriner, 2019).

5.2 The quality of Hunter Biden’s art

As discussed above, news of Hunter Biden’s entry into the art world prompted national media to query well-known art critics about the quality of his art. Those whose assessments were sought include New York art critic Geoffrey Young, national art critic Ben Davis, London art critic Tabish Khan and Jon Ploff, an art professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. After viewing the art, Young explained that the price points selected by the Bergès Gallery were exceedingly high, an opinion that was echoed by national art critic Ben Davis, who, as Lubin (2025) notes, branded Hunter Biden’s paintings as mostly bluff and bluster. Davis also added that he was certain that the Biden name was being sold, and not quality artwork (Lubin, 2025). This conclusion was supported by additional assessments of the art’s quality by Ploff and Khan. Neither Davis, Ploff nor Khan are public choice scholars or political scientists, yet they recognize the basic elements of rent- or transfer-seeking when presented with images of Hunter Biden’s painting. Thus, the foundation for a public choice approach to Hunter Biden’s attempt to sell his paintings and other artwork is laid with evidence of the art’s lack of professional acumen and polish.

5.3 The privilege seeking nature of Hunter Biden’s art sales

During the 2020 election cycle, Elizabeth Hirsh Naftali donated $13,414 to Joseph Biden’s presidential campaign and another $29,700 to the Democratic National Campaign Committee (Walker, 2023) In July of 2022, 17 months after her first purchase of Hunter Biden’s art for $42,000, Naftali was appointed by then-U.S. President Joseph Biden to the U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad (Chow, 2024; Comer, 2024; Solomon, 2024). The U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad (1) identifies and reports on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Eastern and Central Europe that are associated with the heritage of U.S. citizens, and (2) obtains, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of State, assurances from the governments of the region that the properties will be protected and preserved.10 An appointment to the U.S. Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is considered prestigious and typically leads to even higher positions, such as a U.S. Ambassadorship (Walker, 2023). Given that Natfali made a second purchase of Hunter Biden’s art at $52,000 in December of 2022, whatever privileges Naftali sought from the Commission appointment and beyond (if any) were, from a rent seeking (public choice) perspective, valued by her at $137,000 or more.11 Put differently, Naftali’s decision to purchase pieces of Hunter Biden’s art, and the Joseph Biden Administration’s subsequent action, are consistent with the public choice theory of rent (transfer) seeking12. These events also appear to validate the concerns of professional critics of Hunter Biden’s art that are discussed in the preceding subsection of this study.

5.4 President Biden’s job approval and the prices of Hunter Biden’s art

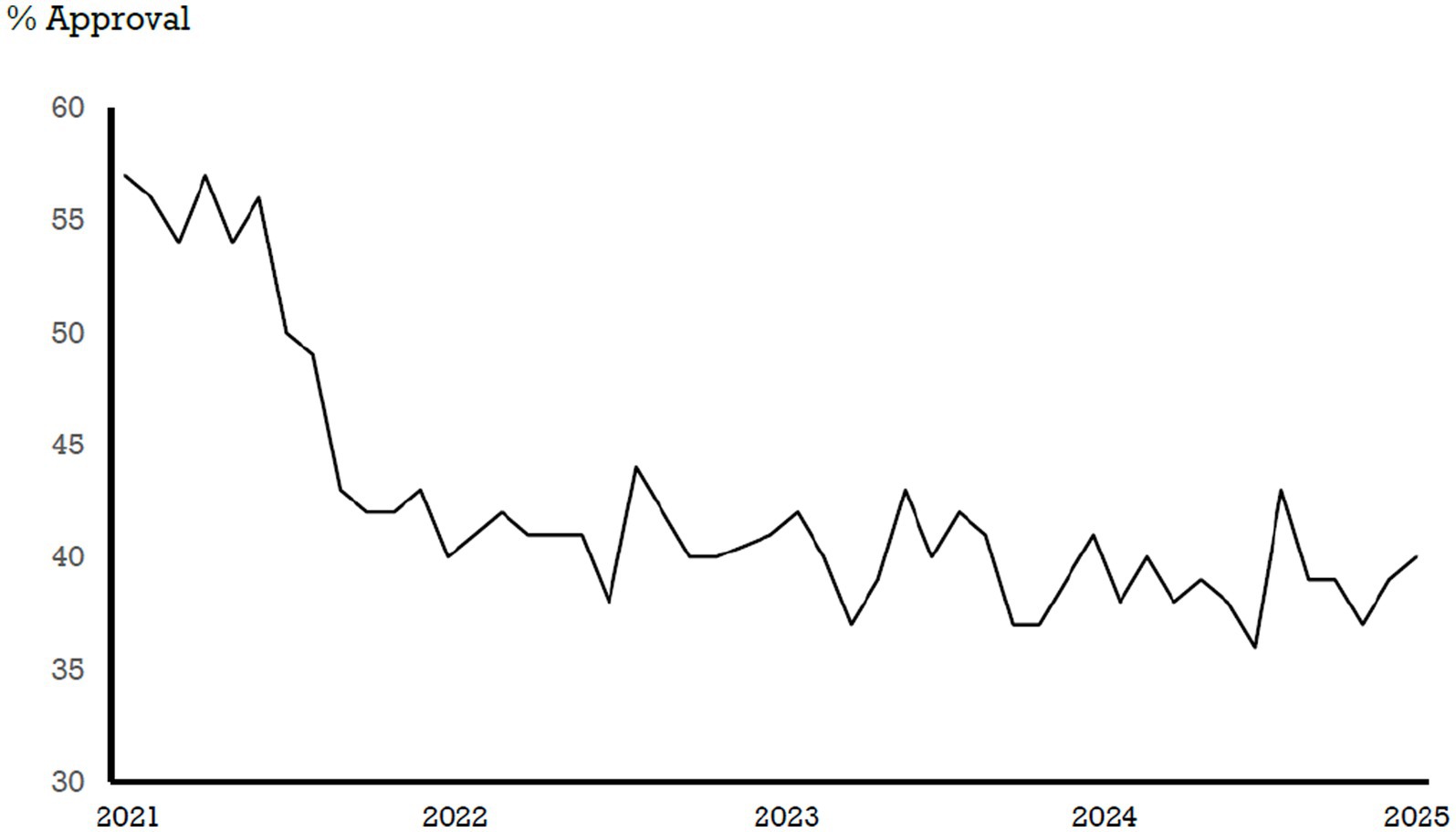

The first two pillars of the public choice approach to Hunter Biden’s art sales—the quality of the art and the privilege-seeking nature of the sales—are qualitative in nature. The third—that there is a positive association between sales prices and President Joseph Biden’s job approval ratings—is amenable to a more quantitative focus. In this regard, Figure 1 presents President Biden’s monthly job approval ratings (Gallup polling) throughout his single term, spanning from January of 2021 through January of 2025. As indicated there, although there are short-term peaks and valleys in President Biden’s monthly job approval with the American electorate between 2021 and 2025, the long-term trend in his monthly job approval is negatively sloped during his presidency, falling from 56% job approval in the first month to 40% job approval in the final month, and peaking at 57% in April of 2021 while reaching its lowest point at 36% in July 2024, the month following his disastrous presidential debate.

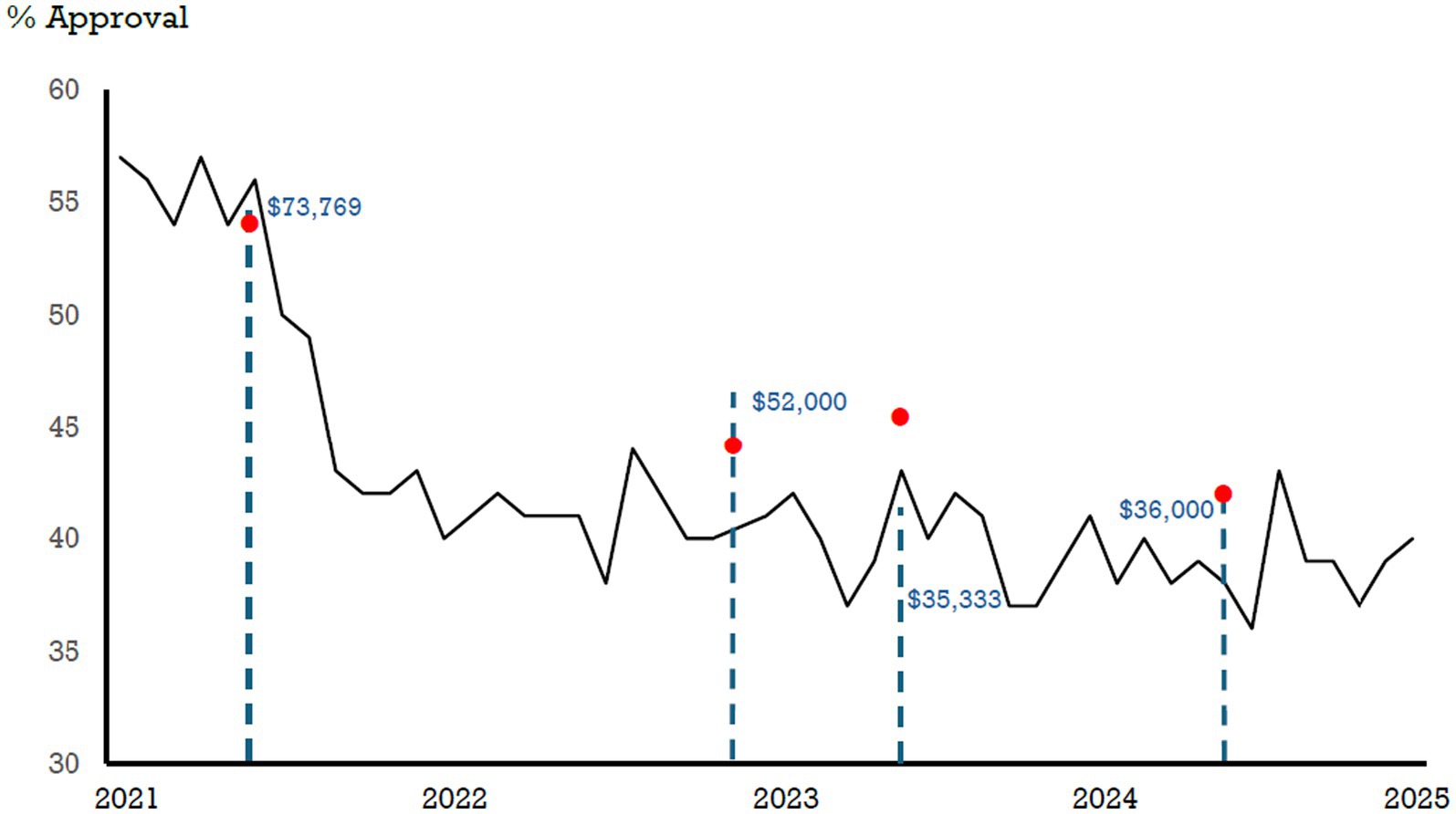

As indicated in the previous section of this study, the details regarding Hunter Biden’s art sales are, by design, relatively scant. What is now known is that Naftali made a purchase of $42,000 in February of 2021, and that there was a contract between Biden and Bergès for the sale of 11 other pieces that year for $875,000. It is also known that Bergès sold a separate piece in late 2020 to an unnamed buyer and for an unspecified price. If one assumes that piece to have been sold for $42,000, which is the amount Naftali paid 2 months later, then the first 13 sales of Hunter Biden’s paintings earned $0.959 million, for an average of $73,769 per piece. Next, it is also now known that Naftali purchased more of Hunter Biden’s art in late 2022 for $52,000, and that in 2024 the final piece sold garnered $36,000. This means that the remaining 12 pieces sold generated $0.424 million, for an average of $35,333 per piece.

Figure 2 is a reproduction of Figure 1 that also includes the four price points for Hunter Biden’s art that are discussed above. These price points are $73,769 for June of 2021, $52,000 for December of 2022, $35,333 for June of 2023 and $36,000 for June of 2024, and they are represented in Figure 2 by the lengths of the dotted blue lines. The first and third of these are computed as the averages of the two sales blocks described above, one containing 13 pieces and the other containing 12 pieces. The other price points are derived from Naftali’s second purchase in 2022 and the anonymous purchase in 2024.

Although limited, the data above are amenable to a straightforward test of the notion that the transaction prices involved in Hunter Biden’s art sales are a function of the political capital of his father, U.S. President Joseph Biden, which can be proxied by the latter’s job approval ratings. More specifically,

where is the transaction price of Hunter Biden’s art at time t, is U.S. President Joseph Biden’s job approval rating at time t, ε is a stochastic error term, and α and β are parameters to be estimated (and referred to as and ).

According to results from a linear regression, the estimate of β, or , from Equation 1 above, is about 1,962, meaning that each percentage point decline in U.S. President Joseph Biden’s monthly job approval rating leads to a $1,962 drop in the realized price of Hunter Biden’s art, a result that is significant at 0.065 level.13 This simple model predicts realized price points of $72,079 in June of 2021, $41,674 in December of 2022, $46,578 in June of 2023, and $36,770 in June of 2024. These estimates are depicted as the red points in Figure 2 and they relate to the lengths of the blue dotted lines representing the transactions prices of Hunter Biden’s art. Lastly, the Pearson r describing the relationship between the realized prices of Hunter Biden’s art and U.S. President Joseph Biden’s monthly job approval ratings is a robust +0.871. These results are all consistent with the third prong of the public choice approach to the sale of Hunter Biden’s art that is developed in this study.

5.5 Critiques of the rent seeking argument

One potential conceptual critique of the singularly focused rent seeking approach to sales of Hunter Biden’s art that is described above is its lack of connection to the cultural economic determinants of the realized prices of art, one of which is the celebrity status of the artist. Celebrity artists (i.e., cross-domain celebrities), including those not associated with any potential for rent seeking, have been known to secure relatively high realized prices for their works of art. A good example is that of famed actor Dennis Hopper, whose notable photographic works include portraits of Martin Luther King Jr., Jane Fonda and Andy Warhol, as well as images taken during the Civil Rights era of the 1960s.1415 A related critique of the rent seeking approach to sales of Hunter Biden’s art that is described above is that the price point trend depicted in Figure 2 is also consistent with the notion that the appeal of Hunter Biden’s name and thus the value of his art declined as he became more entangled in sordid financial arrangements in China and Ukraine.16

Hopper’s example appears to neatly fit the framework for valuing art developed by Marshall and Forrest (2011) that includes the concept of brand strength to describe the celebrity status of the artist, which is the awareness of the artist as a person of note outside of the immediate community of artists. As they explain, such awareness broadens the general market interest in the artist’s works and so may increase demand outside of the artistic community more narrowly defined (Marshall and Forrest, 2011).17 However, in this case there is no indication that Hunter Biden is a cross-domain celebrity who exudes brand strength, having not compiled any notable achievements during his professional life leading up to 2020, when he began selling his paintings. On the contrary, what little the public knew about Hunter Biden’s professional life leading up to 2020 was generally negative. A good example is the exposé by Risen (2015) in The New York Times, which pre-dates the initial sale of Hunter Biden’s art by 5 years. This notion is consistent with Marshall and Forrest (2011), who argue that, in addition to brand strength, celebrity status also includes brand associations, or the value symbols the artist represents. As in other marketing realms, brand associations can be positive or negative, depending on the market segment to which the artist’s work is directed (Marshall and Forrest, 2011). It is likely that any brand associations regarding Hunter Biden’s art were (and are) negative and thus would lead to much lower price points than those realized in 2020 and later.

The second, and related, critique of the rent seeking approach to sales of Hunter Biden’s art is that the declining price point trend depicted in Figure 2 is also consistent with the notion that the appeal of Hunter Biden’s name and thus the value of his art declined as he became more entangled in questionable financial arrangements abroad. As indicated above, there has always been a negative brand association involving Hunter Biden. As such, one could argue that there was never any general appeal associated with Hunter Biden’s name that might erode over time with additional evidence of untoward behavior. Secondarily, the U.S. media have faced criticism, even from within (Tapper and Thompson, 2025), for not appropriately covering controversies involving President Joseph Biden, such as his cognitive decline and the decision by various news and social media outlets to ignore reporting by The New York Post about the discovery of Hunter Biden’s now infamous laptop e.g., (see Zilber, 2025; Steigrad, 2024; Christenson, 2025; Romero, 2023), presumably in an effort to assist Joseph Biden in his 2020 and 2024 election campaigns. Given these actions, the American public was shielded to a large degree from news coverage of Hunter Biden’s controversial activities that, if covered, might have eroded (if even possible) its perception of him.

Lastly, additional evidence against this second critique, and in favor of the rent seeking approach detailed above, is the fact that only 27 paintings by Hunter Biden were sold in the 5 years between 2020 and 2024, half of which were purchased by only two politically connected buyers. Again, this evidence suggests that Hunter Biden’s art was never intended for a wide audience of art lovers, only a small segment of politically motivated associates. The political motivations of these associates were to have Joseph Biden elected U.S. President, and to keep him in that position for two terms. The success of these efforts depended on Joseph Biden’s favor with the American electorate, and not Hunter Biden’s appeal among the wider public.

6 Conclusion

Was the confluence of Joseph Biden’s ascendancy to the U.S. Presidency and his son Hunter Biden’s introduction as a professional artist simply serendipitous? This study asserts that it was not, and in doing so offers a competing hypothesis that establishes the core contribution of this study—namely, that Hunter Biden’s art sales illustrate how cultural markets can function as a novel form of rent-seeking tied to political capital. Partial support for the rent seeking hypothesis is the fact that Hunter Biden’s art was generally panned by respected art critics yet priced by a New York gallerist between $75,000 and $500,000 per painting. The additional fact that one of the sales of Hunter Biden’s paintings occurred just prior to a prestigious commission appointment of the buyer that was conferred by President Joseph Biden lends further support to the rent seeking explanation of Hunter Biden’s new art career. Lastly, statistical evidence that transaction prices of Hunter Biden’s art were sensitive to President Biden’s job approval ratings—with a $1,962 drop in price for every one percentage point decline in job approval—is also consistent with the public choice or rent seeking explanation for this episode in U.S. Political history.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

FM: Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Douglas Noonan and two reviewers of this journal for helpful comments on a prior version. The usual caveat applies.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer HB declared a past co-authorship with the author to the handling editor.

Generative AI statement

The author declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Involvement in rent seeking activities by the family members of U.S. presidents and other politicians is not a new phenomenon. For example, controversy surrounded U.S. President Jimmy Carter when he was accused of using American intelligence information to support his brother Billy Carter’s assistance of an American crude oil company’s dealings with the Libyan government (PresidentProfiles.com). Similar controversy surrounded Hillary and Chelsea Clinton, the wife and daughter, respectively, of former U.S. President Bill Clinton, when concerns arose that foreign donors were using their donations to the family’s Clinton Foundation to influence Hillary Clinton’s decisions as Secretary of State during the Obama Administration (Gaouette, 2016). Lastly, controversy recently surrounded U.S. President Donald Trump again after shares of a cryptocurrency concern tied to his two oldest sons, Donald Trump Jr. and Eric Trump, more than doubled in value in their stock market debut (Qing and Vinn, 2025; Berwick, 2025).

2. ^Hunter suffered a fractured skull and traumatic brain injury while Beau was left with multiple broken bones.

3. ^Interestingly, in 2001 he was controversially rehired by MBNA as a consultant, an agreement that paid him a yearly $100,000 retainer until 2005 (Craven, 2024). In 2006, Biden was appointed to a five-year term on the board of directors of Amtrak by President George W. Bush (Glass, 2007).

4. ^Biden’s partners in this venture were Devon Archer and Christopher Heinz (Schreckinger, 2019).

5. ^Hunter Biden sought assistance from the U.S. State Department on behalf of Burisma in securing an energy project in Italy while his father was Vice President (Tait, 2024). As President, Joseph Biden released records confirming his son’s lobbying effort, although the elder Biden denied ever being aware of his son’s Burisma-related activities (Vogel, 2024).

6. ^According to Herridge and Kaplan (2024) and Swan and Gibson (2024), Hollywood entertainment attorney and Democratic donor Kevin Morris had, since late 2021, loaned Hunter Biden more than $6.5 million to pay owed taxes and fund legal expenses.

7. ^The conviction meant that Hunter Biden was the first child of a sitting U.S. president to be convicted in a criminal trial (Swan and Gerstein, 2024).

8. ^This expansion of the idea of rent seeking led to several studies attempting to estimate its costs to society (e.g., Laband and Sophocleus, 1988 and 1992; Sobel and Garrett, 2002; Hall and Ross, 2009; Del Rosal, 2011).

9. ^Bennister et al. (2015) extend the notion of political capital in describing the related concept of leadership capital as aggregate authority composed of a leader’s skills, relations and reputation.

10. ^ HeritageAbroad.gov

11. ^This total, $137,000, is approximately equal to the sum of $13,314, $29,700, $42,000 and $52,000, with $43,014 representing direct campaign contributions and $94,000 representing purchases of Hunter Biden’s art.

12. ^The public choice theory to which the notion of rent seeking is affiliated is linked to other subfields of economics, such as law and economics, new-institutional economics and Austrian economics (Sánchez-Bayón et al., 2022).

13. ^See Leamer (1978) and Attfield (1982) for advice regarding significance levels using small samples, and Leamer (1988) and Kennedy (2008) for more on the idea the genuinely interesting hypotheses are neighborhoods, not points.

14. ^ ArtNet.com

15. ^Some of Hopper’s images that were sold by Phillips Auction garnered as much as £66,250. The Hopper photograph described here is titled “Double Standard.”

16. ^I am grateful to the reviewers for suggesting that I provide some critiques.

17. ^Other entries in the cultural economics literature describe a more complex relationship between the artist’s name and the value of his or her work. For example, Oosterlinck and Radermecker (2019) focus on the prices of art by anonymous artists labeled with so-called provisional names (e.g., “Master of …”). Based on comparative price indexes and hedonic regressions, they show that masters with provisional names outperformed named artists between 1955 and 2015 (Oosterlinck and Radermecker, 2019). Additionally, Radermecker (2020) tests whether multi-authored attribution affects buyers’ willingness to pay differently from single-authored works in the auction market. Based on a data set comprising 11,630 single-authored and collaborative paintings auctioned between 1946 and 2015, hedonic regression results suggest that the average price of collaborative paintings is statistically lower than that of single-authored paintings (Radermecker, 2020).

References

Angeleti, G. (2021). US president Joseph R. Biden will be remembered as the father of the great artist hunter Biden, his art dealer says. The Art Newspaper, November, 3.

Attfield, C. L. F. (1982). An adjustment to the likelihood ratio statistic when testing hypotheses in the multivariate linear model using large samples. Econ. Lett. 9, 345–348. doi: 10.1016/0165-1765(82)90041-6

Bennister, M., Hart, P., and Worthy, B. (2015). Assessing the authority of political office-holders: the leadership capital index. West Eur. Polit. 38, 417–440. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.954778

Berwick, A. (2025). Trump family amasses $5 billion fortune after crypto launch. The Wall Street Journal, September, 1.

Braun, S., and Berry, L. (2019). The story behind Biden’s son, Ukraine and Trump’s claims. Associated Press, September, 23.

Brown, E., and Yilek, C. (2024). Hunter Biden pleads guilty to all 9 charges in tax evasion case before trial in Los Angeles. CBS News, September, 5.

Bullough, O. (2017). The money machine: how a high-profile corruption investigation fell apart. The Guardian, April, 12.

Chen, A., and Lopatka, J. (2017). China’s CEFC has big ambitions, but little known about ownership, funding. Reuters, January, 13.

Chow, V. (2024). Turns out Hunter Biden did actually know who bought his art. ArtNet.com, January, 15.

Christenson, J. (2025). Ex-Politico reporters reveal ‘cowardly editors’ buried bombshell Hunter Biden laptop stories – fueled ‘misinformation’ narrative involving ex-prez. The New York Post, January, 23.

Christenson, D. P., and Kriner, D. L. (2019). Does public opinion constrain presidential unilateralism? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 1071–1077. doi: 10.1017/S0003055419000327

Comer, J. (2024). Comer statement on interview with Hunter Biden’s art gallerist. U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Responsibility Press Release, January, 9.

Crane, E., and Christenson, J. (2025). Hunter Biden says his art sales plunged since data left White House, bemoans LA wildfires – as he claims he’s broke in bombshell legal filing. The New York Post, March, 6.

Craven, J. (2024). Hunter Biden snagged a cushy bank job after law school. He's been trading on his name ever since. Politico, January, 26.

Cullison, A. (2019). Biden’s anticorruption effort in Ukraine overlapped with son’s work in country. The Wall Street Journal, September, 22.

Del Rosal, I. (2011). The empirical measurement of rent-seeking costs. J. Econ. Surv. 25, 298–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00621.x

Fox, E. J. (2021). I just wanted people to see that not only was I okay, I was great:’ Hunter Biden is painting his truth. Vanity Fair, December, 9.

Gaouette, N. (2016). What is the Clinton Foundation and why is it so controversial? CNN, August, 24.

Gelpi, C., and Grieco, J. M. (2015). Competency costs in foreign affairs: presidential performance in international conflicts and domestic legislative success, 1953–2001. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 440–456. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12169

Hall, J. C., and Ross, J. M. (2009). New empirical estimates of rent seeking: an update of Sobel-Garrett [2002]. J. Public Finance Public Choice 27, 125–136. doi: 10.1332/251569209X15665367046615

Hawkinson, K. (2024). Hunter Biden’s trial on felony tax charges delayed until September. The Independent, May, 22.

Herridge, C., and Kaplan, M. (2024). Kevin Morris’ loans to Hunter Biden totaled $6.5 million, $1.6 million more than previous estimate. CBS News, January, 23.

Homan, T. R. (2020). Biden hits Trump over military ‘losers’ remark, defends son. The Hill, September, 29.

Kamalakaran, A., and Daga, A. (2009). Stanford had links to fund run by Bidens: Report. Reuters, February, 24.

Kessler, G. (2022). Unraveling the tale of Hunter Biden and $3.5 million from Russia. The Washington Post, April, 8.

Krueger, A. O. (1974). The political economy of the rent seeking society. Am. Econ. Rev. 64, 291–303.

Kuspit, D. (2021). Self-healing through art: Hunter Biden’s abstract paintings. Whitehot Magazine, August, 15.

Laband, D. N., and McClintock, G. (2001). The transfer society: economic expenditures on transfer activity. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Laband, D. N., and Sophocleus, J. P. (1988). The social cost of rent seeking: first estimates. Pub. Cho. 58, 269–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00155672

Laband, D. N., and Sophocleus, J. P. (1992). An estimate of resource expenditures on transfer activity in the United States. Q. J. Econ. 107, 959–983. doi: 10.2307/2118370

Leamer, E. E. (1978). Specification searches: Ad hoc inference with nonexperimental data. New York: John Wiley.

Leamer, E. E. (1988). 3 things that bother me. Econ. Rec. 64, 331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4932.1988.tb02072.x

Lubin, R. (2025). Hunter Biden reveals his dire financial situation after selling one piece of art this year and lackluster book buys. The Independent, March, 6.

Mangan, D. (2020). Joe Biden's son Hunter Biden under federal investigation for tax case. CNBC, December, 9.

Marshall, K. P., and Forrest, P. J. (2011). A framework for identifying factors that influence fin art valuations from artist to consumers. Mark. Manag. J. 21, 111–123.

Mixon, F. G. Jr. (1995). To the capitol, driver: limousine services as a rent seeking device in state capital cities. Int. Rev. Econ. 42, 663–670.

Mixon, F. G. Jr., Laband, D. N., and Ekelund, R. B. Jr. (1994). Rent seeking and hidden in-kind resource distortion: some empirical evidence. Pub. Choice 78, 171–185. doi: 10.1007/BF01050393

Mixon, F. G. Jr., and Ladner, J. A. (1998). Sending federal fiscal power back to the states: federal block grants and the value of state legislative offices. J. Public Finance Public Choice 16, 27–41.

Nelson, C. M., and Barnes, J. E. (2014). Biden's son Hunter discharged from Navy Reserve after failing cocaine test. The Wall Street Journal, October, 16.

Oosterlinck, K., and Radermecker, A.-S. (2019). The master of: Creating names for art history and the art market. J. Cult. Econ. 43, 57–95. doi: 10.1007/s10824-018-9329-1

Perez, E., and Brown, P. (2020). Federal criminal investigation into Hunter Biden focuses on his business dealings in China. CNN, December, 10.

Pitas, C., and Whitcomb, D. (2023). DOJ files new criminal charges against Hunter Biden. Reuters, December, 7.

Posner, R. A. (1975). The social costs of monopoly and regulation. J. Polit. Econ. 83, 807–827. doi: 10.1086/260357

Qing, K. G., and Vinn, M. (2025). Trump’s oldest sons’ American Bitcoin state worth $1.5 billion in stock debut. Reuters, September, 3.

Radermecker, A.-S. V. (2020). Buy one painting, get two names: on the valuation of artist collaborations in the art market. Arts. Mark. 10, 99–121. doi: 10.1108/AAM-10-2019-0030

Risen, J. (2015). Joe Biden, His Son and the Case Against a Ukrainian Oligarch. The New York Times, December, 8.

Romero, L. (2023). Former Twitter execs tell House committee that removal of Hunter Biden laptop story was a ‘mistake.’ ABC News, February, 8.

Sánchez-Bayón, A., González-Arnedo, E., and Andreu-Escario, Á. (2022). Spanish healthcare sector management in the COVID-19 crisis under the perspective of Austrian economics and new-institutional economics. Frontiers in Public Health. 10, 801525.

Schier, S. E. (2011). The contemporary presidency: the presidential authority problem and the political power trap. President. Stud. Q. 41, 793–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5705.2011.03918.x

Schreckinger, B. (2019). Biden, Inc.: How ‘middle class’ Joe’s family cashed in on the family name. Politico, August, 2.

Schwartz, M. (2023). Hunter Biden’s gallery sold his art to a Democratic donor ‘friend’ whom Joe Biden named to a prestigious position. Business Insider, July 24.

Sfondeles, T., and Thompson, A. (2021). We asked art critics about Hunter’s paintings. Politico, July, 27.

Sobel, R. S., and Garrett, T. A. (2002). On the measurement of rent seeking and its social opportunity cost. Public Choice 112, 115–136. doi: 10.1023/A:1015666307423

Solomon, J. (2024). Art dealer told Congress that Joe Biden called and met him while he sold Hunter Biden’s paintings. JustTheNews.com, January, 16.

Sonne, P., Kranish, M., and Viser, M. (2019). The gas tycoon and the vice president's son: The story of Hunter Biden's foray into Ukraine. The Washington Post, September, 28.

Steigrad, A. (2024). Ex-CBA News reporter accuses network of ‘defying’ orders from Shari Redstone, CBS CEO to probe Hunter Biden laptop scandal. The New York Post, November, 26.

Stein, P., Barrett, D., and Viser, M. (2024). Hunter Biden found guilty in gun trial. What it means and what's next. The Washington Post, June, 11.

Swan, B. W., and Gerstein, J. (2024). Hunter Biden found guilty on federal gun charges. Politico, June, 11.

Swan, B. W., and Gibson, B. (2024). Hunter Biden’s legal defense has a problem: The patron paying the bills is running out of cash. Politico, May, 15.

Tait, R. (2024). Hunter Biden sought U.S. government help for Ukrainian company Burisma. The Guardian, August, 14.

Tapper, J., and Thompson, A. (2025). Original sin: President Biden’s declined, its cover-up, and his disastrous choice to run again. New York, NY: Random House.

Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Western Econ. J 5, 224–232.

Tullock, G. (1989). The economics of special privilege and rent seeking. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Vincent, I. (2025). Hunter Biden artworks worth ‘millions of dollars’ destroyed in LA fires: Source. The New York Post, January, 15.

Viser, M. (2022). Inside Hunter Biden's multimillion-dollar deals with a Chinese energy company. The Washington Post, March, 30.

Vogel, K. P. (2019). Trump, Biden and Ukraine: Sorting out the accusations. The New York Times, September, 22.

Vogel, K. P. (2024). Hunter Biden sought State Department help for Ukrainian company. The New York Times. August, 13.

Vogel, K. P., and Mendel, I. (2019). Biden faces conflict of interest questions that are being promoted by Trump and allies. The New York Times, May, 1.

Walker, J. (2023). Democratic donor who bought Hunter Biden’s art was named to prestigious commission, report says. CBS News, July, 25.

Whitehurst, L. (2023). Hunter Biden indicted on federal firearms charges in long-running probe weeks after plea deal failed. AP News, September, 14.

Winter, T., Fitzpatrick, S., Atkins, C., and Strickler, L. (2022). Analysis of Hunter Biden's hard drive shows he, his firm took in about $11 million from 2013 to 2018, spent it fast. NBC News, May, 19.

Wise, A. (2020). Hunter Biden says he is under federal investigation for tax matter: Report. National Public Radio, December, 9.

Yu, S., Williams, A., and Olearchyk, R. (2019). Hunter Biden’s web of interests. Financial Times, October, 9.

Ziezulewicz, G. (2019). The people Priebus beat out to become an ensign. Military Times, October, 25.

Keywords: cultural economics, public choice, rent seeking, lobbying, political economy

Citation: Mixon FG Jr. (2025) The price of power: a public choice approach to Hunter Biden’s art sales. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1654700. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1654700

Edited by:

Antonio Sanchez-Bayon, Rey Juan Carlos University, SpainReviewed by:

Armando Rodriguez, University of New Haven, United StatesHem Basnet, Methodist University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Mixon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Franklin G. Mixon Jr., bWl4b25fZnJhbmtsaW5AY29sdW1idXNzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

Franklin G. Mixon Jr.

Franklin G. Mixon Jr.