- Faculty of Political Sciences, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

In May 2023, Serbia witnessed two unprecedented crimes. First, a 13-year-old boy killed nine of his classmates and a school security guard in central Belgrade. The following day, in what appeared to be a copycat act, a 12-year-old man randomly shot and killed nine young people and seriously injured 12 others. These tragedies triggered a wave of protests, initially sparked by shock and grief, but which soon took on a political dimension, accompanied by a set of media-related demands and calls for the resignation of government officials. This paper seeks to explore how media frames were constructed during the protests that followed these tragedies, from early May until November, when snap parliamentary elections were announced. The analysis focuses on seven frames employed by the pro-government tabloid Informer and the opposition-leaning newspaper Danas, each of which shaped the portrayal of the protests in accordance with their respective political alignments-within the context of Serbia’s deeply polarized media, political, and social landscape. Findings indicate that the media played a significant role in the emergence, maintenance, and eventual dissolution of the protests. Both newspapers actively shaped the character of the protests and the portrayal of protest participants in ways deemed suitable for their readerships—that is, for voters aligned with either side of the media-political divide. Both outlets relied heavily on conflict framing; however, Informer also prominently featured a national security threat frame. Additionally, a morality frame was present in both newspapers, though approached from entirely different perspectives.

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, Serbia has experienced numerous protests, which, when considered collectively, can be characterized as mass movements. “This is not the first time, but the ninth time we had a crisis. And every time it has been a serious political crisis. But I do not I believe we had bigger crisis than mass murder in Ribnikar, Dubona, and Orašje,” said the President of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, in interview for Insider TV, commenting the current mass protests in Serbia, in 2025.

In May 2023, Serbia experienced two unprecedented tragedies. The first incident involved a mass shooting at the prominent Vladislav Ribnikar school in Belgrade, where a 13-year-old used his father’s gun to tragically kill nine children and a school guard. The following day, amidst national shock, a 20-year-old man, inspired by the previous incident, randomly targeted young people in one of Belgrade’s peripheral districts, resulting in nine fatalities and serious injuries to at least 12 individuals. These events induced shock, panic, and trauma within the community, garnering significant attention from both domestic and international media. Citizens began gathering in front of the Belgrade school, subsequently engaging in organized mass protests against violence. Initially, the protests had a civil character, with people gathering to light candles and pay respects to the victims in downtown Belgrade. However, within a few days, the gatherings evolved into mass protests involving tens of thousands of people, who began delivering demands to the government, media, and society.

The protests gradually adopted political characteristics, with several opposition parties presenting themselves as informal organizers by issuing demands to the authorities. The opposition did not immediately publicly present itself as the organizer of the protests due to its damaged public reputation. Firstly, most political parties had already been in power and had an unfavorable political reputation (Vukomanović and Marković, 2024). Secondly, the opposition had been demonized over the years during the decade-long rule of the Serbian Progressive Party, publicly disgraced in the media sympathetic to the ruling party, which dominate the media space in Serbia (Dragojlov, 2025). Thirdly, President Vučić had successfully framed all previous civil protests, through the strategic use of media to ascribe a political character to the protests, ultimately minimizing their societal impact (Vranić and Jevtić, 2024). The peak of the protests occurred in late May when the government and President Vučić organized a state rally titled Serbia of Hope, mobilizing participants from across the country. The following day marked the peak of the Serbia Against Violence rally, which began after the mass murders.

These events were covered by deeply polarized media (Fletcher and Jenkins, 2019), with two ideological poles: media supported by the ruling party and critically oriented opposition media linked to cable operators. Their well-established media frameworks turned the media landscape into a battlefield, with both sides appealing to the public interest and defending themselves from the “enemy.” In this context, the contingency of pain (Ahmed, 2014), or more accurately, the economy of pain, ideologically framed emotions within the political battleground. The protests culminated in the parliamentary elections in December 2023, where the Serbian Progressive Party emerged victorious.

The demands of the protesting citizens, articulated by the opposition, were primarily media-related. These included the dismissal of the Council of the Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media, the shutdown of print media and tabloid outlets that disseminate false information and violate journalistic ethics, and the revocation of national broadcasting licenses for television stations Pink and Happy, which were accused of promoting government propaganda and violent content. Additional demands called for the immediate cancelation of television programs that promote violence, immorality, and aggression—such as reality shows—on nationally broadcast channels. Political demands followed, including the dismissal of the Minister of the Interior, the head of the Security Intelligence Agency, and the Minister of Education. Immediately after the first demands were made public, the Minister of Education Branko Ružić submitted his resignation (on May 7).

At the peak of the protests, President Vučić publicly requested the owner of the pro-government television station Pink, Željko Mitrović, to cancel the reality show Zadruga, a program that, without any censorship and in real time, promotes vulgarity, verbal and physical violence, and features participants with controversial backgrounds, including convicted criminals. Mitrović promptly complied, stating that “the unity of Serbia and the judgment of the President of the Republic are more important than any interest of TV Pink or his own personal interests.” Shortly thereafter, however, he launched a new reality show.

The protests, within their political and international context, did bring about certain changes, although the sustainability of these changes remained uncertain. The government adopted a new Law on Public Information and Media, while Ursula von der Leyen, during her visit to Belgrade, congratulated President Vučić, noting that Serbia is “one of the most advanced countries in the accession process,” (Radio Television of Serbia, 2024) which is why efforts are underway to open Cluster 3. At the same time, the European Commission’s 2024 Progress Report on Serbia continued to state that “no progress was made in the area of freedom of expression and the media” (European Council, 2024, p. 7).

The aim of this paper is to establish the media matrices used in the coverage of protests from both ends of the ideological spectrum. These findings will help illuminate how narratives were constructed and framed in the transformation of civic and political discourse, and to what extent such reporting led to changes on both ends of the political spectrum. The paper focuses on analyzing articles in the pro-government tabloid Informer and the opposition-oriented newspaper Danas, from May 8, when the protests started, until November 1, when the protests subsided and were replaced by the election campaign. The newspaper Informer is a traditional propaganda outlet of the Serbian Progressive Party, serving to promote and announce the party’s policies and those of its leader. The outlet is known for its continual violations of the Journalists’ Code of Ethics and for frequent legal cases related to its content. Unlike Informer, the daily Danas adopts a civic-oriented, pro-European editorial stance, historically critical of the government and since 2021 under the ownership of United Media—making it a de facto opposition outlet. Its format is more serious and less tabloid-driven, though clearly aligned with the civic, liberal opposition.

These findings should point to the established media matrices employed by both the ruling majority and the opposition to implement their policies, regardless of the nature of the protests or their underlying causes. The study is theoretically grounded in framing theory, particularly in its correlation with social movements, as well as in current theoretical debates surrounding the protest paradigm in the media. In this regard, the paper aims to contribute by offering a perspective on protests within a hybrid media system such as that of Serbia, while also addressing the use of pain as a component in a highly polarized and politicized media and social environment.

The text is divided into seven sections: following the introduction, the theoretical framework is presented, focusing on media framing and the protest paradigm. This is followed by an overview of the political context in Serbia, the research methodology, and then a separate analysis of seven selected frames—first in the newspaper Informer, and then in Danas. The analysis concludes with a discussion and final summary and interpretation.

2 Theoretical framework

For a social or political movement to be successful, it must be communicative and culturally aligned with the goals of its followers and the political context (Rennick et al., 2024). Exploring a social movement involves inquiring into how “various players interpret what the problem is, what must be done, who the opponents are, and what opportunities are present” (Noakes and Johnson, 2005, p. 24). Walgrave and Manssens (2000) point out that participants “must not only be convinced of the rightness of the cause but also be encouraged to take action” (p. 218). This paper takes framing theory as its theoretical ground for analyzing protests (Garg and Rai, 2021; Snow and Benfrod, 2000; Entman, 1993; Goffman, 1986; Gitlin, 1980). For Snow and Benfrod (2000), framing plays a crucial role in shaping the meaning and direction of movements by “assigning meaning to and interpreting relevant events and conditions in ways that are intended to mobilize potential adherents and constituents, garner bystander support, and demobilize antagonists” (p. 198). Additionally, they highlight that “movements can thus be seen as functioning in part as signifying agents and, as such, are deeply entangled, alongside the media and the state,” resembling Stuart Hall’s ‘politics of signification’ (Ibid, 198).

Framing is inseparable from social movements. It refers to the “presentation on judgment and choice” (Iyengar, 1996, p. 61) and represents the media’s selection of certain aspects of reality, making them visible, communicative, and prominent in messages, in order to “promote a particular definition of the situation, a certain causal interpretation, a certain moral evaluation and a proposal for some remedies” (Cruel, 2018, p. 7).

This process is not fixed, especially in the case of dynamic or transformative political events, or specific occurrences that “actors know will take place, but of whose outcome they are uncertain” (Basta, 2018, p. 1243). However, there are certainly frameworks and techniques through which these messages are made more visible and clearly presented in the media. In the media context, theorists refer to the “protest paradigm” (Papaioannou, 2020; Mourão, 2019; McLeod, 2007). The protest paradigm shows that protests and protesters are portrayed negatively in the media in most cases, using a “set of strategies for framing protests, focusing on limited features of protestors and portraying them as the ‘Other’” (Papaioannou, 2020, p. 3290). The protest paradigm has been recognized as a media framework for many mass events, initiated by various “triggers,” as a “routinized pattern of media coverage” or “normative role of mainstream media within the contemporary political process” (Tomanić Trivundža and Slaček Brlek, 2017, p. 134). The protest paradigm is predominantly a negative and well-established framework employed by mainstream media to either legitimize or delegitimize various forms of dissent, depending on the nature of the protest and the stance adopted by the media outlet.

However, there are several techniques through which this concept is operationalized within the media sphere. The protest paradigm portrays demonstrators as a uniform group, overlooking the diversity within modern protests, which often involve multiple organizers or factions with varying levels of militancy, routinely framing protestors as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Hence, the frames of “‘the people’ and ‘the masses’ represent the binary potential of democracy in which ‘masses’ (crowd) represents ‘the other’ nature of ‘the people’ (demos or public): the violent and animalistic Mr. Hyde to the civilized and enlightened Dr. Jekyll” (Tomanić Trivundža and Slaček Brlek, 2017, p. 136). Even though it is mostly negative, some triggers, such as the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014, may promote a sympathetic frame in the media (Elmasry and El-Nawawy, 2017).

The protest paradigm, or media framing of events according to a specific model, uses established frameworks and clearly defined contexts in polarized media. This paradigm may serve to subjectively determine protests episodically, rather than thematically, while there are strategies for framing these protests. Recent research on the framing of protests shows that, in some cases, the media have revised this paradigm and framing strategy, resulting in less predictable media responses to street events (Papaioannou, 2020). Frames can reveal the nature of a regime, the structure of the political order, and the type of support that media extend to particular regimes—whether they are “hybrid regimes” or liberal democracies. For instance, a comparison of reporting on the Euromaidan protest in Ukraine in 2013 by British and Russian media shows the shared nature of one-dimensional reporting—while the Russian media framed the events through the “lenses of economic consequences and morality, aligning with the country’s political rhetoric on Ukraine, British media predominantly employed a human-interest frame, offering largely one-sided coverage” (Liu, 2020, p. 1).

In this analysis, the author seeks to identify the presence of seven specific frames in two newspapers and examine their application through the lens of the protest paradigm, with the aim of uncovering underlying media matrices. This study uses a deductive framing approach but, it will combine frames from appropriate research (Muncie, 2020; Papaioannou, 2020; Mourão, 2019; Tomanić Trivundža and Slaček Brlek, 2017; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). Drawing on Entman’s (1993) conceptualization, framing is understood as the process of selecting and emphasizing certain aspects of a perceived reality to promote specific problem definitions, causal interpretations, moral evaluations, and treatment recommendations. In addition to Entman’s model, the study incorporates insights from complementary research to underscore the significance of protester perception as a key indicator of media polarization. The analysis applies a range of broad, generic frames listed in five frames—attribution of responsibility, conflict, human interest, economic consequences, and morality—derived from Semetko and Valkenburg (2000). According to these authors, the frames are explained as: conflict frame—emphasizes conflict between individuals, groups, or institutions as a means of capturing audience interest; human interest frame—brings a human face or an emotional angle to the presentation of an event, issue, or problem; economic consequences frame—reports an event, problem, or issue in terms of the consequences it will have economically on an individual, group, institution, region, or country; morality frame—puts the event, problem, or issue in the context of religious tenets or moral prescriptions; responsibility frame—presents an issue or problem in such a way as to attribute responsibility for its cause or solution to either the government or to an individual or group (Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000, pp. 94–95).

Furthermore, the study incorporates two more frames derived from theory—the national sovereignty frame and the good vs. bad protestors frame. The frame of national sovereignty, as outlined by Papaioannou (2020), is contextualized within narratives concerning foreign mercenaries. This dimension is explored in relation to its potential to affect the national habitus and catalyze political change. These are combined with frames that distinguish between good vs. bad protesters, where violence functions as a framing device that influences perceptions of political legitimacy (Muncie, 2020; Mourão, 2019; Tomanić Trivundža and Slaček Brlek, 2017).

3 Political context and media landscape in Serbia

Serbia is experiencing a continued erosion of democracy (Vladisavljević, 2019) and a decline in media freedom, with authorities “putting legal and extralegal pressure on media” (Freedom House, 2023) and promoting political clientelism within the media sphere (Dragojlov, 2025). Although the country remains formally on its path toward European Union membership, it is simultaneously undergoing democratic backsliding (Kakarnias, 2025). President Vučić has “exploited his popularity as a self-proclaimed defender of the Serbian nation to gain full control of the party and initiate democratic backsliding through ‘legislative capture’” (Milačić, 2025). Vučić has been intrinsically linked to the media, especially dailies that have, for years, framed him as both a type of Übermensch—extremely competent, strong, and efficient—while simultaneously developing a victimhood narrative (Mladenov Jovanović, 2018, p. 22). Although engaged in a constant digital campaign through his Instagram account—which has become “an important source of information for mainstream media in Serbia” (Krstić, 2022, p. 7)—and despite commanding a strong army of internet activists (Freedom House, 2023), Vučić remains primarily focused on traditional media, particularly television, followed by daily newspapers. This is largely because nearly all weekly publications in Serbia are opposition-oriented and generally do not reach the audience he aims to address.

The Serbian media market has experienced similar challenges to those faced by other post-communist countries in Central Europe that have undergone transitions and, in some cases, wars. It is a fragile media market that may formally comply with European legislation, yet the implementation of such laws remains highly questionable. Serbia is among the European countries where the political independence of the media is at high risk (Bleyer-Simon et al., 2023, p. 70). The media market is small, underdeveloped, and heavily influenced by the government (Kisić, 2015). Comparisons are often drawn with Hungary due to the erosion of institutions and the development of electoral (competitive) authoritarianism following a period of democratic transition and partial consolidation—despite Hungary being an EU member state, whereas Serbia is not (Milutinović, 2022). The media landscape is deeply polarized and instrumentalized, blurring the line between pro-government and independent outlets. Although these two media blocs are vastly unequal in terms of power and influence, they coexist and shape a highly divided media environment (Kulić, 2021).

The daily newspapers Informer and Danas, which are the subject of this analysis, represent two opposing poles within a deeply divided social, political, and media landscape. Informer is a pro-government tabloid that often functions as the communicative arm of the Serbian Progressive Party, despite being one of the newspapers with the highest number of violations of the Serbian Journalists’ Code of Ethics (Press Council, 2023). It openly promotes, announces, and explains the policies of Aleksandar Vučić, while the paper’s owner, Dragan J. Vučićević, publicly endorses his close personal relationship and friendship with President Vučić. Informer has a vivid history of protest coverage and protest framing over the past decade, from the anti-government protest in 2016 (Vranić and Jevtić, 2024), the “One out of Five Million” protest in 2018–2019 (Mladenov Jovanović, 2019), the protest in 2023, up to the current protest in 2024–2025.

Danas is a newspaper with a civic, pro-European orientation and a significantly smaller circulation compared to Informer. It is an opposition media outlet, founded in 1997, maintaining its oppositional stance since the era of Slobodan Milošević’s rule, with a strong history of protest coverage (from the ‘90s). In 2021, it became part of the United Media group, which was established in Luxembourg and operates across the region. The television channels owned by this media group are recognized as fierce critics of Aleksandar Vučić’s regime, and the orientation of Danas has been further reinforced by its transition from a joint-stock company to corporate ownership under a strong ideological framework.

Although these newspapers represent two opposing poles, they are not equivalent—neither in terms of reach, influence, nor available resources. While Informer is a tabloid privately owned by Dragan J. Vučićević and Danas is part of a media corporation, Informer’s circulation is several times higher than that of Danas. Informer benefits from a strong political backing originating from the state, which grants it a disproportionately advantageous position both in the media market and in relation to state institutions. Danas, on the other hand, is a newspaper with a longer publishing history, but due to the nature of its distribution and its editorial orientation, it maintains a more limited readership within Serbia.

4 Methodology

Given the established theoretical framework, this paper aims to address the central research question:

RQ1: In what ways were media matrices framed during the protests following the mass shootings in Belgrade and the vicinity of Mladenovac?

This primary question will be followed by several subsidiary inquiries:

RQ2: How have these media matrices influenced media and societal polarization? What are the differences in the framing of events across both ends of the media spectrum?

RQ3: To what extent does the representation of the protests align with the protest paradigm?

The analysis uses the deductive frame approach with seven frames derived from the theoretical framework. Five frames were taken from Semetko and Valkenburg’s approach: responsibility, conflict, human interest, economic consequences, and morality. The national sovereignty frame was taken from Papaioannou (2020), while the last frame of good vs. bad protestors was derived from a group of authors (Muncie, 2020; Mourão, 2019; Tomanić Trivundža and Slaček Brlek, 2017). All frames were identified and systematically explained within the theoretical framework. The coding process was operationalized by the author, marking the presence of each frame in every individual text within the sample.

The paper focuses on analyzing articles in the pro-government tabloid Informer and the opposition-oriented newspaper Danas, from May 8, when the protests started, until November 1, when the protests subsided and were replaced by the election campaign. Although the sample covers a 6-month period, extending until early November—after which the pre-election campaign begins—the majority of the articles pertain to the first wave of protests (May–July), when the demonstrations were at their peak. This concentration serves as an indicator of the frequency of the protests and their media resonance, as well as the discursive framework applied during that period.

Since these are articles from the daily press, texts were selected from the day before, the day of, and the day after the protests, which were mostly held on Fridays at first, and later less frequently. The day after the protest was often a double issue due to the weekend, which is indicated in parentheses. The sample includes front pages and articles related to the protests—specifically news reports, coverage, and interviews directly connected to the events. Columns and opinion pieces by regular or guest contributors were not included in the sample. The sample comprises 51 articles from Informer and 68 articles from Danas, taking into account that some issues contained multiple texts on the topic, each counted individually.

The mass shooting occurred on May 3 and 4, 2023. After memorials were held in front of schools and 3 days of national mourning, the gatherings quickly turned into mass marches, beginning on May 8. The government responded immediately through televised appearances, framing the protests as a “misuse of grief,” while the demonstrations continued on a weekly basis. The peak of these events came with two major rallies: the Serbia of Hope rally on May 26 and the Serbia Against Violence rally on May 27, held on consecutive days, each aiming to showcase the size and strength of their respective sides. Over the course of 2023, more than 25 Serbia Against Violence protests were held, until President Aleksandar Vučić called parliamentary elections on November 1, 2023. This analysis focuses on media coverage during May and June, while the subsequent 3 months, up to October 30, serve to illustrate the tactic of ignoring the events and allowing them to fade from public discourse.

The analysis will present each frame individually for each newspaper, following the same order, after which the key findings will be compared.

5 Analysis

5.1 Frame analysis—informer

5.1.1 The conflict frame

The media’s approach to the protests intensified across all frames, particularly within the conflict frame, up until the pro-governmental Serbia of Hope (“Srbija nade”) rally, at which point Vučić gave the protests a more defined narrative. It was then, for the first time, that he characterized them as a movement of dissatisfied citizens and an opposition exploiting a national tragedy; prior to that, they had been portrayed solely as an opposition initiative. Media monitoring of the protests was clearly present until mid-June, but the quality of the frames shifted, and interest gradually declined thereafter.

The analysis revealed that the frame examined first—the conflict frame—was present in nearly every article published by this daily newspaper. From the outset of the analyzed period, the articles clearly delineate “sides in the war,” most prominently in a piece where an anonymous source conveys decisions made by the President of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, which he communicated to his party members. Vučić thus announces “far-reaching political decisions” against the “blackmail and lies” of the opposing side, which he labels as “political scum”:

“As long as I live, I will fight against the worst scum who see their only political chance in tragedy. You must always fight against these hyenas, for the salvation and future of our country.” (Informer, May 8).

From the very beginning of the protests, the conflict frame was presented as the opposition’s desire to cause chaos in the streets by calling for “protests against violence” in front of the National Assembly, exploiting two major tragedies, engaging in “political scavenging of national tragedy,” because they “do not care about the children and the victims” (Informer, May 8). In this context, all subsequent articles were framed around the intention of the opposition (rather than that of the citizens), called as “haters” and “so-called patriots,” to incite disorder, achieve a violent overthrow of the government, and initiate a color revolution—drawing direct comparisons to the Maidan protests in Ukraine.

The newspaper introduces conflict and paradoxes in all narratives around the protests. For example, the fact that a speech at a non-political protest was given by Marina Vidojević, an activist and teacher affiliated with the movement Do not Let Belgrade Drown, is presented as hypocrisy. Simultaneously, the same issue of the newspaper gives extensive coverage to Vučić’s appearance on Happy TV, reiterating and emphasizing every point he made, in alignment with the newspaper’s editorial stance.

The scale of the Serbia Against Violence protest is downplayed, with the newspaper contrasting manipulated figures: “10,000 haters blocked a bridge in Belgrade, while 30,000 gathered at Vučić’s rally in Pančevo” (Informer, May 20/21). At the same time, the Public Meetings Archive (Arhiv javnih skupova), recorded that the third Serbia Against Violence protest gathered between 55,000 and 60,000 participants. This juxtaposition serves to delegitimize the opposition while presenting the president as a competent leader—someone who “opens factories” and “welcomes protesters arriving by trains and railways he built” (Informer, May 20/21).

Within this frame, the opposition was reduced to a few central figures, effectively narrowing the entire protest to those individuals. The opposition is labeled as a group of opportunists rejecting institutional channels of debate. Its leaders, such as Radomir Lazović and Nebojša Zelenović, are portrayed as dishonest and disruptive—either refusing to debate or misusing media appearances to promote protest (Informer, May 19). Protest participants are stigmatized as intoxicated individuals or suspects of violence (Informer, June 10/11).

Sporadically, Informer offers “evidence” to support the claim that the protests are, in fact, a color revolution. This evidence is presented either through articles alleging ties between the opposition and foreign capital, through statements by political analysts, or more commonly through statements made by politicians—most frequently President Vučić—thereby intensifying the conflict and deepening antagonism. Only at the end of May, at the peak of the protests, Vučić and Informer distinguish between “humble and decent citizens” protesting legitimately and “politicians who exploited national tragedy.” Yet, Vučić firmly declares: “There will be no transitional government. You will have to kill me—I will never allow it!” (Informer, May 29). The president’s rhetoric escalates to martyrdom, with hyperbolic declarations of generational resistance, in stark contrast, the opposition’s rally is barely covered and dismissed as driven by “hatred of Vučić,” led by “traitors, right-wingers, and gay guardians of family values” (Informer, May 29). All subsequent major protests are similarly framed as provocations by “opposition scavengers” seeking power through violence (Informer, June 3/4).

From mid-June onward, the intensity of media coverage declined, leading to a shift in the quality of the conflict framing. Events were reduced to claims of public disturbance and immorality: “Opposition supporters who blocked Belgrade got drunk and partied while exploiting the tragedy of Serbian children” (Informer, June 19). Later, protests are portrayed as meaningless disruptions.

5.1.2 The human interest frame

The human interest frame is rarely present in the content of Informer, yet it appears in the form of personalized narratives, where specific, symbolically charged public figures articulate views aligned with the newspaper’s ideological stance. The broader protest narrative is also shaped around the controversial statements of opposition politician Srđan Milivojević, who allegedly declared that President Vučić would “end up like Gaddafi” (Informer, May 13/14). Disproportionate attention is paid to extremist voices within the opposition. For example, the statement by writer Marko Vidojković—an outspoken public figure known for radical views—criticizing the Patriarch and leadership of the Serbian Orthodox Church (a traditionally acclaimed institution), is presented as symbolically transgressive (Informer, May 20/21).

Traditional human interest stories, focusing on ordinary citizens’ experiences and emotions, are virtually absent. In Informer’s coverage, citizens as autonomous social actors are effaced; only opposition politicians and alleged extremists are depicted as participants in the protests. The only instance where citizens are portrayed positively is in the context of the Serbia of Hope rally, where the paper focuses on Serbs from Kosovo who walked to the event, labeling them as “Serbian heroes” (Informer, May 25). Toward the end of protest coverage—when demonstrations are treated merely as spatial disruptions—an isolated example of human interest reemerges: a report on a pregnant Slovenian woman in her 8th month, allegedly caught in a roadblock after a six-hour drive (Informer, July 1/2).

5.1.3 The economic consequences frame

The economic consequences frame is not dominant in the selected sample. It appears sporadically in the form of corruption scandals involving opposition figures (Informer, May 12), or in statements contrasting the government’s economic achievements with the purportedly destructive agenda of the opposition, described as “blockers” (Informer, May 19) 1. This frame is further constructed through references to the “sale of land for a handful of dollars,” suggesting that such sell-offs occurred during the opposition’s time in power (post-2000) and would no longer be tolerated under the current leadership. Such rhetoric is used to reinforce the frame of “protecting Serbia from destruction” (Informer, May 29).

5.1.4 The morality frame

The morality frame is deeply embedded in nearly every article analyzed. The narrative is structured around a dichotomy between a morally upright and responsible government, embodied by Vučić, and an immoral opposition allegedly seeking to destabilize Serbia by exploiting public grief following recent tragedies to seize power through violent means. The Informer frequently refers to the Serbia Against Violence protests as “so-called,” implying that their true purpose is the unconstitutional and immoral overthrow of government.

This perceived immorality is expressed symbolically and rhetorically. For instance, the newspaper criticizes the timing of opposition rallies, noting that they occur “the day after a three-day mourning period,” while depicting opposition MP Đorđe Miketić as “laughing as though he were at a concert with friends” (Informer, May 9). In contrast, the Serbia of Hope rally is portrayed as both morally and historically righteous—the largest public gathering in Serbian history (Informer, May 25).

The morality frame is also ethicized and internationalized by associating the opposition with historical or perceived enemies of Serbia. For example, opposition leaders are described as “traitors,” “tycoons who betrayed their friends,” “false nationalists,” or “LGBT activists protesting with their spouses and children” (Informer, May 29). These symbolic associations link political dissent to foreign influence and moral deviance.

5.1.5 The responsibility frame

The responsibility frame is closely tied to the morality frame and centers on the role of the president as the ultimate guarantor of national stability and security. This is particularly evident in coverage surrounding the Serbia of Hope rally on May 26, framed as a historical event and a platform for Vučić’s reaffirmation of leadership (Informer, May 27/28). From the earliest to the final articles in the corpus, the coverage presents a clear asymmetry: the government is portrayed as responsible and protective, while the opposition is presented as reckless and destructive.

When protestor responsibility is mentioned, it is never individualized or portrayed in terms of ordinary citizens, but always as the responsibility of opposition leaders—either through their statements (Informer, May 9), or through collective labels such as “hateful and destructive opposition” (Informer, May 19). Additionally, responsibility is attributed to foreign intelligence services and NGOs, accused of orchestrating a “witch-hunt against the president and Serbia” (Informer, May 20/21). This attribution of responsibility is inseparable from the morality frame and often accompanied by severe normative judgments, such as accusations that the opposition “exploits tragedy for political gain” (Informer, May 8), or engages in “shameful behavior” (Informer, May 19).

5.1.6 The national sovereignty frame

The national sovereignty frame is one of the dominant narrative structures in Informer’s coverage, closely tied to the responsibility of the head of state to protect the integrity of the nation. It started from the very beginning of the protest coverage, with Vučić stating that he “does not give up the fight for Serbia and the Serbian people” (Informer, May 8). This narrative suggests that the nation is under threat, linking to frames of national security. Notably, in his first speech after the mass murders, Vučić referenced the population in the southern province of Kosovo, suggesting that this “struggle” is waged simultaneously on two fronts: against internal and external enemies jeopardizing Serbia’s territorial integrity.

The protests are not depicted as internal civic unrest, but as both internal and external threats aimed at undermining the state order and achieving regime change—that is, at “destroying Serbia” (Informer, May 8). This threat is allegedly orchestrated by a “criminal opposition” working to “bring Serbia down” (Informer, May 20/21), in collaboration with “enemies from nearly every dark corner” (Informer, May 8). These include NGOs and regional actors—particularly Bosniak and Albanian lobbies—as well as Croatian journalists and experts (Informer, May 20/21; May 26; June 10), and local NATO sympathizers who “recognize the false state of Kosovo” and seek to instigate a “Maidan-style war in Serbia” (Informer, June 9). Significant symbolic weight is given to Hungarian politician Péter Szijjártó, who appeared at the rally in support of Vučić: “We once saw each other as enemies, but now we are friendly nations. We are under attack because we oppose the war in Ukraine, because we stand for family values, and because we refuse to let outsiders dictate our choices. They do not hesitate to exploit tragedies to ignite a colored revolution, like Kyiv’s Maidan” (Informer, May 27/28).

This frame constructs a dual external-internal conspiracy, often personalized through easily recognizable, symbolically simplified figures—typically associated with historical or ethnic adversaries. Protests are repeatedly depicted as “foreign-financed” (Informer, May 12; May 19). Many articles featuring President Vučić focus on defending national sovereignty against perceived enemies “from within and without.” Even the call for the Serbia of Hope rally is framed as a call to “defend Serbia against those who would destroy it at any cost” (Informer, May 25). Within this sovereignty frame, the Kosovo issue is frequently invoked. In one of his first public addresses following the mass shooting, Vučić simultaneously addressed the tragedy and the situation in Kosovo. Informer echoed this dual focus by quoting an anonymous party official who relayed Vučić’s commitment: “I will fight for Serbia, for our southern province, for the homeland and the Serbian people until my last breath, against the worst scum who see tragedy as their only political opportunity” (Informer, May 8).

5.1.7 The good vs. bad protesters frame

The good vs. bad protesters frame is highly prevalent, aggressive, and morally dichotomous. It labels opposition figures as planners of violence, including attempts to assassinate the president and carry out a violent overthrow of the government. This frame reinforces the portrayal of President Vučić and the state leadership as the only morally upright actors. Notably, Informer fails to recognize ordinary citizens as legitimate protest participants, describing demonstrations as “so-called civic protests.” Even when unknown speakers address the crowd, the paper traces their political affiliations, thereby suggesting that all protests are ultimately partisan acts (Informer, May 9). The citizenry appears only in Vučić’s rhetoric, where he distinguishes between “decent, honest citizens who attend protests” and “politicians who exploit tragedy” (Informer, May 27/28). Outside of this context, citizens are almost entirely absent, especially at local-level protests, which Informer tends to ignore.

Opposition protesters are regularly dehumanized and vilified: referred to as “vultures from the opposition,” “arrogant opposition members,” and accused of having “not a shred of empathy” while they engage in “pure terrorism against citizens” during times of mourning (Informer, May 13/14). The paper also relays incendiary statements, such as the claim that a protester said Vučić should be “slaughtered and sent back to Čipuljići” (his parents’ birthplace) (Informer, May 13/14).

5.2 Frame analysis—Danas

5.2.1 The conflict frame

In covering the protests, Danas’ reporting falls into two phases: from the mass shooting until mid-June, and from mid-June until the protests ended (or until the elections). Initially, while insisting on the protests’ civic nature, the paper nonetheless focuses heavily on opposition politicians—most notably Democratic Party MP Srđan Milivojević and Radomir Lazović—whose statements are heavily featured. Even when they deny formally organizing the protests, Danas refers to them as informal organizers, effectively undermining the protests’ grassroots characterization. In the second phase, the focus shifts toward amplifying the voices of students, professionals, and ordinary citizens, signaling a move toward depoliticization, although protest momentum appears to wane as summer approaches.

The question of protest organization is central to legitimizing the movement. Initially, on May 8, there was no explicit party sponsorship. However, all quotes from that period in Danas feature Milivojević and Lazović, with Milivojević stating: “Neither I, nor my friend and comrade Radomir Lazović are the leaders of these protests. These are citizens’ protests” (Danas, May 26). Although the opposition had presented these same demands during the parliamentary session on May 17, having previously adopted them as its own on May 10. Claims by the ruling party that the protests exploit tragedy for political ends are rarely mentioned, nor are they critically examined. Instead, Danas includes remarks such as that from screenwriter and MP Siniša Kovačević: “The opposition does not organize the protests—it coordinates them. Someone has to inform the police. Someone has to handle the logistics” (Danas, May 20/21).

While Danas maintains a largely factual tone, it includes a significant number of personal columns and commentaries—particularly by celebrities (mostly actors) whose views resonate with the public. A “we vs. they” distinction pervades the paper, even when not explicitly articulated by journalists, as the views of contributors reinforce the editorial orientation. This dichotomy is most visible in protest speeches by prominent cultural figures—e.g., Svetlana Bojković, Dragan Bjelogrlić (June 5), or Jelisaveta Seka Sablić (June 10).

The issue of conflict is not presented explicitly, as it is in the tabloid press, but an antagonism is depicted, whose axis of division is markedly deep. This antagonism is framed as a struggle between decent, awakened citizens and a corrupt government, i.e., an opposition fighting against “the rotten and mafia-like regime of Aleksandar Vučić” (Danas, May 26). This frame in Danas does not correspond to a direct conflict in the sense of anti-systemic action, as it is portrayed in the daily Informer. However, between May and mid-June, the conflict is represented through the struggle of citizens and opposition representatives “to fulfil the demands of the protests,” with resolution implied in political messages calling for a change of government: “Unlike the previous two gatherings, this one featured political slogans calling on the President of Serbia to resign and chanting: ‘Resign, Vučić’” (Danas, May 20/21). Later, Danas published analytical content with headlines such as: “Would a transitional government be a good opposition demand?” and “It is still unclear how Vučić will ‘fall’” (Danas, May 26). This line of reporting, though absent from protester demands, aligns with government claims that the ultimate goal is regime change.

The newspaper underscores the non-violent nature of the protests, shifting the focus to provoked violence potentially inspired by government representatives, that is, to repression carried out by the regime. As early as the second protest, with a striking image and clear headline “A Silent March and the Blockade of Gazela Bridge,” journalists noted that significantly more people attended compared to the first protest, where organizers estimated 50,000 participants, adding that “the protest passed without incidents, and ambulances were let through on three occasions” (Danas, May 13/14). The violence referenced by the paper is described as orchestrated incidents, while “the police remain silent,” and the regime is said to inspire and control it because “their role is precisely that—to attack citizens during peaceful mass demonstrations in order to cause the protests to fail due to threats to participants’ physical safety” (Danas, June 5). In this sense, the conflict portrayed in this daily is not physical but rather a symbolic antagonism between “us” and “them,” with all violence attributed to the regime and its agents.

The conflict frame presented in the newspaper Danas operates on two levels. Firstly, it reflects the ongoing antagonism between this oppositional newspaper—whose orientation is, by its very nature, in opposition to the regime—and the ruling authorities. Secondly, the conflict is articulated through specific case studies, in which rebellion against the “corrupt regime” is framed as a fundamental moral imperative of the citizens. From this standpoint, both protesters and political figures position themselves in moral opposition.

This form of dissent or conflict is not conveyed through the journalist’s own expressions, as is typical in tabloid reporting, but rather through the strong language used by interviewees and their labeling of the regime (e.g., as mafia-like, corrupt, authoritarian), as well as its leader (through protest imagery, derogatory terms for the president—see section 5.2.7). In this context, the rebellion is presented as a basic civic right, and a narrative is constructed that legitimizes all forms of disobedience as a moral principle.

For instance, cartoonist Dušan Petričić, in an interview, argues that it is the government that desires violence. At the same time, he comments on the character of the ruling authorities, thereby legitimizing the method of their removal: “It never occurs to them to step down peacefully from power, which shamelessly and irresponsibly sends a message to the people—We rule you through violence, and it is clear that this is how you will have to remove us” (Danas, May 25).

The readership of Danas—which tends to be civic-minded, oppositional, and often highly educated—does not expect the kind of language promoted by tabloid outlets, such as simplified mapping or editorial remarks reinforcing the state narrative. This audience actively distances itself from the archetypal consumer of state-controlled media (as evidenced by protest demands explicitly calling for the shutdown of such outlets). Thus, Danas employs a more sophisticated strategy to amplify the conflict, portraying it as a legitimate uprising against a “decaying regime.”

In this regard, the paper heightens emotional resonance and reinforces political positions through a form of “elite enumeration,” dividing the public into “us versus them”—on the one side, the educated civic Serbia (actors, writers, professors) that supports the protests, and on the other, those who either support the regime or are compelled to do so.

5.2.2 Human interest frame

Most of the texts do not feature traditional human interest stories. However, Danas does personalize the protests through individuals with a certain social status and role—most often actors, writers, and cartoonists. Their views are overtly political, often radicalized, and align with the newspaper’s editorial stance, thus reinforcing its orientation. This strengthens the discourse of an elite civic Serbia, symbolized by prominent actors, as opposed to the “other” Serbia, which may also have actors but who are perceived as partisan and of lower caliber. Accordingly, many texts during the first period (May/mid-June) rely on statements or speeches from prominent community members, rather than classic human interest narratives.

In some cases, Danas interviews actors who articulate a binary between “decent Serbia” and the “other.” Actress Tamara Dragićević, for instance, claims that “the government sees actors as a threat” (Danas, May 29). Actor Marko Janketić declares: “I will go to the protest even on crutches” (Danas, May 19). In response, government figures accused these actors of hypocrisy, questioning their participation in state-funded media while protesting the state. When SNS Executive Board President Darko Glišić stated that “actors who do not support the regime can go act somewhere else,” actor Nikola Kojo replied to Glišić via social media, as quoted by Danas: “Sweety, how about you change the country?” (Danas, May 26).

Conversely, the coverage of the government-organized rally on May 26 was framed in terms of the logistical difficulties faced by citizens and students, even though the earlier city blockades caused by the Serbia Against Violence protests were never reported as disruptions to urban functioning. The paper reported that “in a large number of Belgrade elementary and particularly high schools, classes were shortened, in some cases held online, or entire shifts rescheduled” (Danas, May 27/28). Without clear evidence, journalists suggested that “many previously scheduled excursions and student trips were canceled because buses were redirected to transport citizens to the rally in Belgrade,” citing testimonies from school principals who were allegedly asked to attend the rally and bring five other people with them (Danas, May 27/28).

From mid-June onward, speakers at the protests were increasingly not established media figures but symbolic representatives of specific societal groups or experts in their fields—retired military personnel, university professors, and actress Seka Sablić (Danas, June 10/11) or individuals portrayed as “victims of a failing system” (Danas, June 17/18). From the third week of June, the focus expanded to protests in towns across Serbia, where local community figures typically served as speakers, thereby personalizing the protest narrative. While Informer dehumanizes protesters and marginalizes ordinary citizens, Danas initially highlights prominent social figures and only later includes regular citizens, reflecting each paper’s distinct political alignment and contributing to the deepening of societal divides.

5.2.3 The economic consequences frame

The economic consequences frame is almost entirely absent as a theme and rarely explicitly addressed (noted only in two protest-related articles). When protests shift to the local level in early July, the economic consequences frame emerges more clearly, describing cities hosting protests—such as Jagodina—as “one of the most indebted cities,” with an “empty municipal treasury.” In response, local authorities, led by Dragan Marković Palma, claim that “protests over the last 20 years have caused more damage than floods,” noting that the protesters are not local but from surrounding areas (Danas, July 4).

5.2.4 The morality frame

The morality frame is pronounced throughout the analysed sample and centers on the notion that citizens have a responsibility and obligation to resist, whereas those attending rallies supporting the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) are portrayed as coerced and manipulated. This is reflected in the headline: “Can mandatory attendance for the SNS rally on May 26 backfire? – The coerced decide at the elections” (Danas, May 19). Moral questions also dominate statements from actors active in protests, such as actress Seka Sablić’s comment: “How can the government not be ashamed in front of its own children” (Danas, May 19). This moral discourse gains an “over-moral” or elitist character, establishing a dichotomy between “true” citizens and “the others,” often manifesting as a problematic divide between “Belgraders” as agents of change and others.

According to this narrative, the opposition and citizens collectively bear responsibility for change; their protests are framed as nonviolent and ideologically pure. The opposition-led blockades and demonstrations do not disturb the collective because they are morally justified and the only rightful actions. Hence, opposition MP Aleksandar Jovanović Ćuta declares the Gazela Bridge blockade “the only free institution” (Danas, May 17), despite such a blockade being legally prohibited as it is part of a highway.

5.2.5 The responsibility frame

The morality frame in Danas is directly linked to the responsibility frame, where accountability for the current situation lies solely with government officials. While the government accuses the opposition of exploiting tragedy to overthrow the regime, the opposition claims the government has created an atmosphere in which such tragedies become possible. Nevertheless, the paper quotes opposition politicians stating that “they do not protest only against verbal violence but against violence against common sense” (Danas, May 26). Protest organizers attribute accountability for the tragedy to the government, demanding the cancelation of reality shows on the commercial Pink TV, a propaganda tool of the regime accepted by its owner at the president’s request (Danas, June 5). Thus, the morality and responsibility frames are almost inseparable, present in nearly every article, and serve as the foundation for the newspaper’s social policy stance and media orientation.

5.2.6 The national sovereignty frame

The national sovereignty frame is virtually absent. In Danas, state issues are viewed primarily from the perspective of its citizens, while government perspectives appear early in the protests through statements like that of the Minister of Labour Darija Kisić Tepavčević, who labeled the event a “political protest” and described the opposition as “opposition to Serbia” (Danas, May 9). While Informer frames the protests as a national security threat orchestrated by enemies and portrays opposition protesters as violent and illegitimate, Danas presents the protests as a citizen-led, morally justified rebellion against government repression, highlighting elite opposition figures as leaders.

5.2.7 The good vs. bad protesters frame

The division between “good” and “bad” demonstrators is clear and persistent in this paper. However, this division becomes analytically ambiguous early in the protests since it remains unclear who organizes them. Official narratives claim citizens are the organizers, yet opposition leaders are treated as “informal protest leaders.” These leaders are presented positively, as fighters and comrades of the people, while the citizens are represented through their most prominent social figures—famous actors. During the first, most massive wave of protests, ordinary citizens were almost marginalized and entirely personalized through recognizable personalities. Simultaneously, all actions—ringing the Presidential building, blocking international roads, and blocking the public broadcaster—were depicted as peaceful and legitimate activities supported by all citizens except those in power, described as “unobtrusive” actions aimed at improving society (with the implicit question: will road blockades force the government to meet citizens’ demands?) (Danas, May 26).

Danas also features tempered positions from prominent individuals like writers and professors (Marko Vidojković, Jovo Bakić), who personally insult regime figures (the president is publicly referred to as “Nepomenik”—similar to Lord Voldemort from Harry Potter—He who must not be named) (Danas, May 24/25), and statements concerning potential physical reprisals against regime supporters after a political change, though these are treated as reasonable criticism backed by international writers’ associations or academic groups. As the protests moved to the local level, the framing maintained that “decent” citizens suffered regime repression, citing, for example, a professor taken to court for supporting protests—even though the political activity was expressed within classroom settings, which is legally prohibited (Danas, May 4). While Informer dehumanizes protesters and marginalizes ordinary citizens, Danas initially highlights prominent social figures and only later includes regular citizens, reflecting each paper’s distinct political alignment and contributing to the deepening of societal divides.

6 Discussion

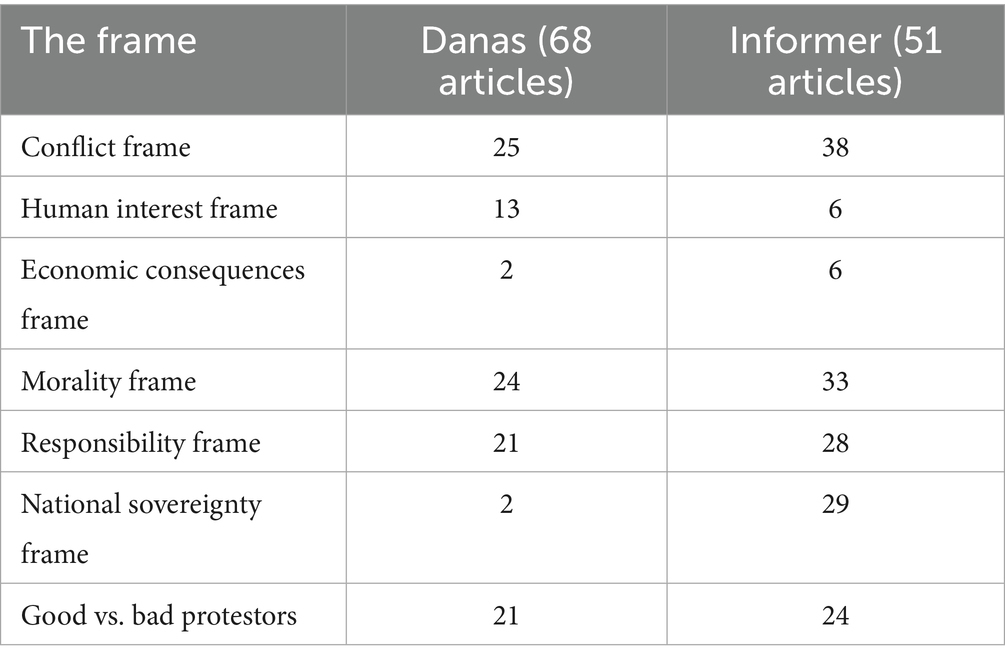

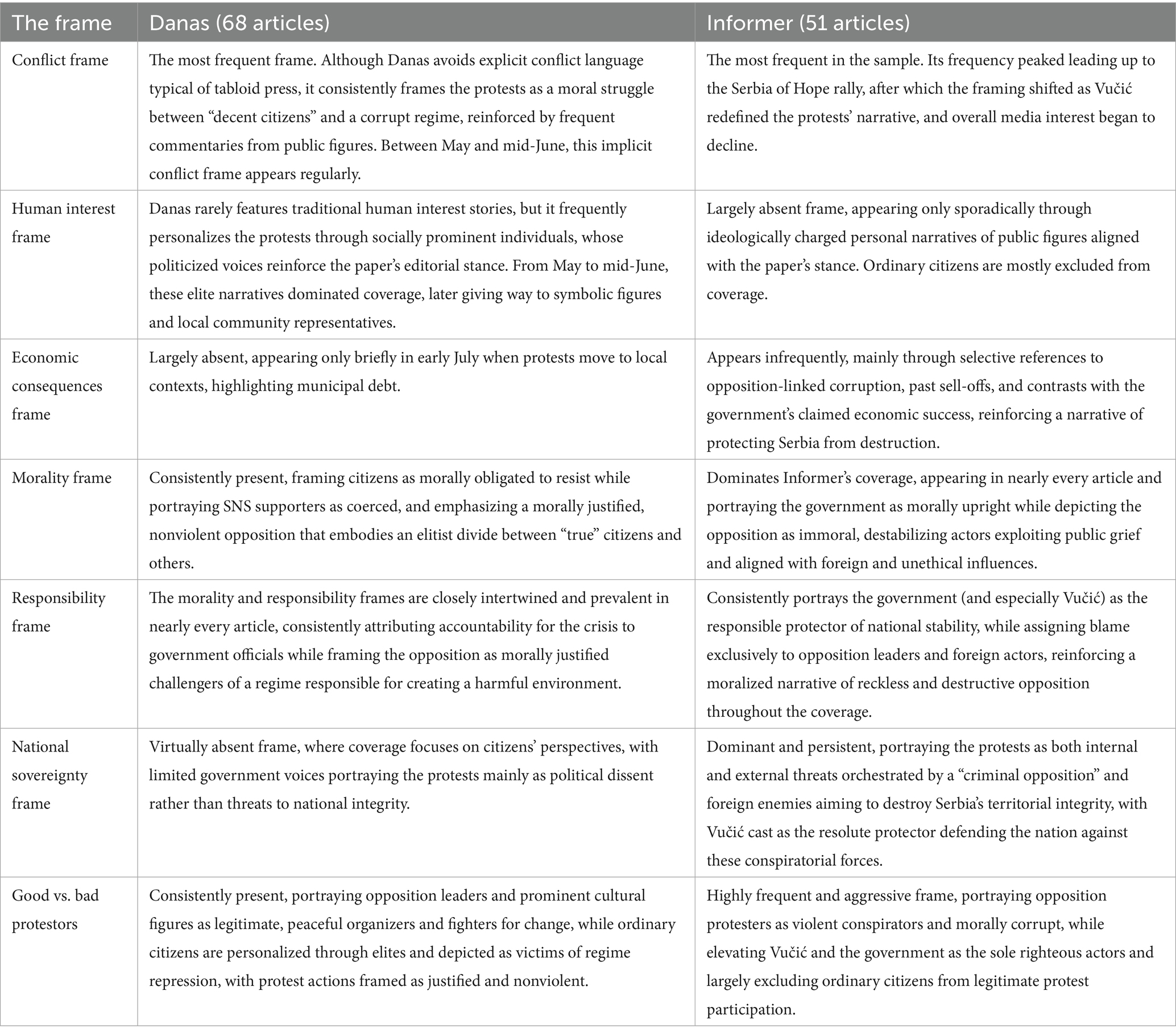

Research has shown that both newspapers employed specific and well-established media frames to encourage activism on both sides of the political spectrum, aligning with their respective political orientations—both promoting conflict as the primary basis for framing content. In the pro-government media outlet, a particularly prominent frame was that of national security being under threat. Furthermore, this analysis demonstrated that the media played a dominant role in the emergence, maintenance, and eventual dissolution of civic and opposition protests—both in terms of the demands protest participants directed at the authorities and in shaping the nature and character of the protests (Table 1).

In this capacity, the media contributed to the construction of narratives that were useful and instrumental either to the government or the opposition, depending on which side they supported. However, in doing so, they significantly deviated from journalistic codes of ethics, manifestly or latently violating them, and directly contributed to deepening the divide in an already highly polarized media, social, and political landscape. By promoting constant conflict—whether through classic confrontation or the continuous emphasis on divisions such as “us” and “them”—both newspapers, regardless of their orientation, deepen the media and social divide, continually reinforcing the protest paradigm. For the pro-government media, protesters are inherently a disruptive force, and the protests are not seen as involving ordinary citizens, but rather violent opposition members. For the critically oriented media, however, the participants are portrayed exclusively as citizens, pushing party elements into the background, while simultaneously portraying supporters of the ruling party who attend rallies as coerced or misled.

Each newspaper, in its own method and domain, clearly aligned with a political stance by selecting event elements that served its interests and matched its ideological orientation. The protest paradigm is aligned with the editorial orientation of each newspaper—in one case, protesters are portrayed exclusively negatively, in the other, exclusively positively, while the actual citizens participating in the protests receive the least attention.

Danas, as a paper of the “civic Serbia” and explicitly opposition-oriented, pursued this more subtly, through political messages sometimes interpreted as calls for the violent overthrow of the government, voiced by representatives of the social elite (actors, singers, directors, writers, professors). In contrast, Informer framed the entire event as an opposition attempt to undermine the state, simplifying the struggle into a conflict between the government and enemies, accompanied by defamation, labeling, and discrediting of political opponents, media, and the so-called “elite” Serbia. Informer emphasized conflict—opposition versus state—shaping the entire narrative accordingly. Conversely, Danas presented the protests as a citizens’ rebellion against a repressive government continuously producing violence, ultimately linking this violence to mass murders.

Both newspapers used prominent individuals to reinforce their editorial policies, though Informer also sought to discredit these “political symbols of elite Serbia” promoted by Danas. Personal stories of ordinary citizens were nearly negligible—Danas only focused on them later, when protests moved to the local level and gradually faded. Meanwhile, Informer addressed citizens primarily through those supporting the president or extreme cases of individuals caught in opposition blockades.

Economics did not emerge as a prominent frame in either paper, while the morality frame was present in both: in Danas, through the opposition’s struggle representing citizens against repressive authorities; and in Informer, conversely, through the government’s responsibility to protect the state and citizens from a violent and irresponsible opposition. Consequently, responsibility is divided oppositely in the two papers—Danas assigns sole responsibility for violence and citizen dissatisfaction to the government, while Informer credits the government for peace and stability and blames the opposition for violence and destabilization. The national security frame is addressed exclusively by Informer, portraying protests as a “colored revolution” aimed at destabilizing the country and overthrowing the constitutional order. Danas almost entirely avoids this frame.

Regarding the good/bad protester frame, it represents the culmination of these antagonisms and is based, admittedly, on the exclusion of citizens from the protests. Danas foregrounds the opposition as protest leaders, calling them “informal leaders” even when members hesitate to self-identify as such, clearly positioning citizens secondarily. Informer, however, exclusively focuses on the opposition as the sole protest participants, fully politicizing and dehumanizing them. When Danas begins to address citizens directly, the protests lose significance, and Informer largely ceases coverage except in cases of excesses. In these cases, politics of pain are used instrumentally, leveraging emotional distress for political articulation Table 2.

7 Conclusion

The paper seeks to analyze how media frames were constructed during the protests that followed the mass shootings in Belgrade and the vicinity of Mladenovac, how these frames contributed to media and societal polarization, and what differences emerged across the media spectrum. The research reveals that media outlets on both sides of the political spectrum employed distinct framing strategies to represent the protests, mobilize their respective audiences (voters)—and align their media narratives with their political affiliations, whether government-aligned or opposition-oriented.

This research once again demonstrates that the media do not merely report on events or protests—they actively construct them. Such a media environment creates fertile ground for instrumentalized political mobilization, as well as for political and content manipulation, the shaping of public opinion, and the amplification or suppression of popular will by various interest and political groups. At the same time, it represents a space where journalistic codes of ethics are increasingly eroded, giving way to the classic application of populist frameworks. Within these frameworks, media outlets (on the both sides of political spectrum)—divided into “us” versus “them”—advance the particular interests of both sides under the guise of pursuing a “higher goal” or adhering to a singular “moral principle,” often driven by fear of the other.

The media framing matrix during these protests largely mirrors that observed during earlier protests in Hercegovačka Street1 (Vranić and Jevtić, 2024), intensified by the event’s demand for greater emotional engagement due to unprecedented mass murders of children and young people in a school. Just as then, the government, through its media, quickly politicized civic protests, framing them as part of a planned hostile strategy to overthrow power before their stated goals were achieved—categories the government has long successfully employed. This narrative rapidly diminished protest intensity and ultimately extinguished them through elections. The opposition’s ambiguous and somewhat clumsy approach to organizing the protests—initially denying, then admitting and coordinating leadership—facilitated this narrative’s endurance. By linking the protest clearly to a colored revolution and political figures, the protest was relatively easily suppressed despite the emotional weight and commitment motivating it.

In comparison with previous research, it is evident that both sides employ distinct templates in framing protests. Pro-government media tend to assign a political character to every civic action—regardless of whether it is genuinely civic in nature—often followed by claims of foreign funding. This framing serves to position such actions clearly within the political landscape, where President Vučić holds dominant authority. Opposition-oriented media, on the other hand, emphasize the civic dimension of the protests—particularly given the opposition’s unfavorable public image—and promote a form of political depersonalization. In this case, such framing was feasible only in the early stages of the protests and was used strategically to enable broader mobilization.

Protests in Hercegovačka Street and those following the mass killings at Vladislav Ribnikar school, and later in villages around Mladenovac, represented significant political blows to Aleksandar Vučić’s government. Media framing of these events was notably similar and contributed to their suppression. Future analyses should consider student blockades of universities and institutions during 2024/2025, also initiated by tragedy—the collapse of a platform at the Novi Sad railway station that killed 16 people. These protests, at least in the first 6 months, were depersonalized, lacking prominent student representatives or opposition involvement. Such analysis could provide important insights into the nature of the regime and the role of media in Serbia’s highly polarized society. Such an analysis could also reveal the genesis of the political depersonalization of the protests and the mobilizing effect of this approach.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The paper is part of the Horizon research project “Embracing Change: Overcoming obstacles and advancing democracy in European Neighbourhood” (EMBRACE), founded by the EU (Grant agreement: 101060809).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Footnotes

1. ^The protests emerged in response to the unannounced demolition of an old quarter in Hercegovačka Street (Savamala)—an area known for its urban and artistic gatherings—to clear space for the Belgrade Waterfront development, a project widely criticized as a form of state-driven gentrification.

References

Ahmed, S. (2014). The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g09x4q.

Basta, K. (2018). The social construction of transformative political events. Comp. Polit. Stud. 51, 1243–1278. doi: 10.1177/0010414017740601

Bleyer-Simon, K., Brogi, E., Carlini, R., Da Costa, D., Borges, K., Nenadić, I., et al. (2023). Monitoring media pluralism in the digital era: application of the media pluralism monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the year 2022. EUI, RSC Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF), Research Project Report, 2023. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/1814/75753

Cruel, D. (2018). The framing of protest. Professional Communication and Translation Studies 11, 7–15.

Dragojlov, A. (2025). Influence of political clientelism on media freedom under Vucic and the progressive party. Natl. Pap. 1-17, 1–17. doi: 10.1017/nps.2025.25

Elmasry, M. H., and El-Nawawy, M. (2017). Do black lives matter? A content analysis of New York Times and St. Louis post-dispatch coverage of Michael Brown protests. Journal. Pract. 11:7, 857–875.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

European Council (2024). Serbia report. Communication from the commission to the European parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of Regions. Available online at: https://enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/3c8c2d7f-bff7-44eb-b868-414730cc5902_en?filename=Serbia%20Report%202024.pdf (Accessed September 18, 2025)

Fletcher, R., and Jenkins, J. (2019). Polarisation and the news Media in Europe. European Parliament: Publications Office of the EU.

Freedom House. (2023) Serbia Country Report. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/serbia/freedom-world/2023 (Accessed September 6, 2025)

Freedom House. (2025). Serbia, Country Report. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/serbia (Accessed September 6, 2025)

Garg, G., and Rai, S. (2021). Framing analysis of media coverage of protest movements: a systematic review of literature. Int. J. Commun. Dev. 12, 10–33.

Gitlin, T. (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making & unmaking of the new left. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Goffman, E. (1986). Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Iyengar, S. (1996). Framing responsibility for political issues. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 546, 59–70. doi: 10.1177/0002716296546001006

Kakarnias, T. (2025). Decoding Serbia’s democratic backsliding: EU conditionality meets domestic realities. Eur. Polit. Sci. 24, 293–312. doi: 10.1057/s41304-025-00518-8

Kisić, I. (2015). The media and politics: the case of Serbia. Southeastern Eur. 39, 62–96. doi: 10.1163/18763332-03901004

Krstić, A. (2022). Pogled odozgo: Vizuelno predstavljanje građana na Instagram profilu predsednika Aleksandra Vučića. Političke Perspective 11, 7–33.

Kulić, M. (2021). “Dezinformacije u polarizovanom okruženju: medijska slika Srbije” in Građani u doba dezinformacija. ed. A. Krstić (Beograd: Udruženje za političke nauke, Fakultet političkih nauka), 7–26.

Liu, Z. (2020). News framing of the Euromaidan protests in the hybrid regime and the liberal democracy: comparison of Russian and UK news media. Media War Conflict, 15, 1–20.

McLeod, D. M. (2007). News coverage and social protest: how the media’s protect paradigm exacerbates social conflict. J. Disp. Resol. 2007, 1–10.

Milačić, F. (2025). Democratic backsliding through legislative capture in Serbia: a one-man show. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 712, 47–60.

Milutinović, I. (2022). Medijski pluralizam u kompetitivnim autoritarnim režimima – komparativna studija Srbija I Mađarska. Sociologija, 64, 272–294.

Mladenov Jovanović, S. (2018). You’re simply the best: communicating power and victimhood in support of president Aleksandar Vučić in the Serbian dailies Alo! And informer. J. Media Res. Revista de Studii Media 31, 22–42.

Mladenov Jovanović, S. (2019). One out of five million: Serbia’s 2018-19 protests against dictatorship, the media, and the government’s response. Open Polit. Sci. 2, 1–8.

Mourão, R. R. (2019). From mass to elite protests: news coverage and the evolution of antigovernment demonstrations in Brazil. Mass Commun. Soc. 22, 49–71. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2018.1498899

Muncie, E. (2020). ‘Peaceful protesters’ and ‘dangerous criminals’: the framing and reframing of anti-fracking activists in the UK. Soc. Mov. Stud. 19, 464–481. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2019.1708309

Noakes, J. A., and Johnson, H. (2005). Frames of protest: social movements and the framing perspective. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Papaioannou, T. (2020). Dominant and emerging news frames in protest coverage: the 2013 Cypriot anti-austerity protests in national media. Int. J. Commun. 14, 3289–3308.

Press Council. (2023). Izveštaj o radu Saveta za štampu u 2023. godini. Available online at: https://savetzastampu.rs/lat/izvestaji/izvestaj-o-radu-saveta-za-stampu-u-2023-godini-2/

Radio Television of Serbia. (2024). Vučić: Nadam se da ćemo do kraja godine otvoriti klister 3 u pregovorima sa EU. Fon Der Lajen: Partnerstvo između Srbije I EU jača. Available online at: https://www.rts.rs/lat/vesti/politika/5563651/vucic-nadam-se-da-cemo-do-kraja-godine-otvoriti-klaster-3-u-pregovorima-sa-eu-fon-der-lajen-partnerstvo-izmedju-srbije-i-eu-jaca.html (Accessed September 6, 2025)

Rennick, S. A., Jmal, N., Vladisavljević, N., Vranić, B., Žilović, M., Bosse, G., et al. (2024). EMBRACE working paper 1. Contentious politics after popular uprising: Assessing how EU democracy promotion can help bottom-up actors achieve small-scale democratic gains : EMBRACE Project Publications.

Semetko, H. A., and Valkenburg, P. M. V. (2000). Framing European politics: a content analysis of and television news. J. Commun. 50, 93–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02843.x

Snow, D. A., and Benfrod, R. D. (2000). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilisation, international social movement research 1, 197–217.

Tomanić Trivundža, I., and Slaček Brlek, S. (2017). Looking for Mr Hyde: the protest paradigm, violence and (de)legitimation of mass political protest. Int. J. Media Cult. Polit. 13, 131–148. doi: 10.1386/macp.13.1-2.131_1

Vranić, B., and Jevtić, M. (2024). One tabloid to rule them all: structuring populist media response–the case of Belgrade waterfront protests in 2016. Politička misao 61, 7–29.

Vukomanović, D., and Marković, K. (2024). “Conceptualization of violence in the parliamentary debate in the National Assembly of Serbia” in Конференција Друштво и структурно насиље. Univerzitet Filozofski fakultet, Institut društvenih nauka (Beograd), 57. ISBN 978-86-6427-336-7.

Keywords: mass-murder, pain, protest, opposition, Serbia

Citation: Jevtić M (2025) The pain on the political battlefield—structuring the role of the media in protests triggered by mass murders in Serbia. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1654950. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1654950

Edited by:

Sarah Anne Rennick, Arab Reform Initiative, FranceReviewed by:

Amel Boubekeur, The American University of Paris, FranceDejan Bursać, University of Belgrade, Serbia

Miloš Milenković, University of Defence in Belgrade, Serbia

Copyright © 2025 Jevtić. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Milica Jevtić, bWlsaWNhLmpldnRpY0BmcG4uYmcuYWMucnM=

Milica Jevtić

Milica Jevtić