- College of Humanities and Social Sciences, American University of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia

In 2018, a mass uprising, known as the Velvet Revolution, ousted an unpopular semi-authoritarian government in Armenia. The new government vowed rapid democratization through ambitious reforms. Key civil society actors enthusiastically supported the shift in the political atmosphere, embracing the post-uprising window of opportunity to engage with the new government and push for democratic consolidation in their respective areas of expertise. This paper examines anti-corruption and judicial reforms in post-revolutionary Armenia, focusing on the role of civil society actors in maintaining the pro-democratic momentum. The paper investigates the following research question: “What was the role of civil society organizations in anti-corruption and judicial reforms in Armenia after the 2018 Velvet Revolution?” We rely on document analysis and qualitative interviews with civil society representatives, policy experts and government officials to argue that the strength of civil society and availability of allies partially explain the differences in anti-corruption and judicial reform processes and outcomes. In the anti-corruption case, the main actors (the government, prominent civil society organizations, and the EU) were more or less “on the same page.” In the case of the judicial reform, there were strong divisions of opinion among civil society organizations, local and international experts. The findings contribute to broader understanding of the role of civil society in the early years of democratic transition.

1 Introduction

Post-2018 Armenia is an interesting case of an attempted shift to democracy after a peaceful uprising, followed by serious challenges, such as COVID-19, defeat in a war, influx of refugees, caused by an ethnic cleansing in the neighboring Azerbaijan, and constant security threats. The outcome of the Armenian bid for democracy remains uncertain in the face of economic and security challenges, regional instability, world democratic backsliding and Russia's unwillingness to let Armenia out of its orbit of influence.

Before 2018, Armenia was a competitive authoritarian state (Levitsky and Way, 2010) with weak political opposition, semi-meaningful elections (Ordukhanyan, 2019) and high levels of corruption (Paturyan and Stefes, 2017; Policy Forum Armenia, 2013; Stefes, 2006). Armenian civil society was relatively well-developed (Aghekyan, 2018). It combined a fairly institutionalized organizational sector with a more recently developed grassroots activism and experience with issue-specific campaigns, known as “civic initiatives” (Ishkanian, 2016, 2015; Paturyan and Gevorgyan, 2021). Some studies highlight the role of civil society in the lead-up to (Zolyan, 2020) and during the 2018 uprising (Feldman and Alibašić, 2019). Few studies and reports address the role of civil society after the 2018 transition (Gevorgyan, 2024; Margaryan et al., 2022). This paper aims to contribute to this growing body of literature, by focusing on the role of civil society organizations (CSOs) in specific policy reforms, crucial for democratic consolidation.

The 2018 Velvet Revolution was a watershed event in contemporary Armenian history, considered a major democratic breakthrough by some and an unfortunate precursor to the tragic loss of Artsakh1 by others. Armenia continues to remain in an uncertain situation of high fluidity, where the democratic project could go either way. Combating entrenched corruption and strengthening the rule of law through judicial reform are two intertwined policy areas that could greatly improve the chances of democratic consolidation. Moreover, if these reforms are not just a top-down government project, but are implemented in collaboration with, and under a watchful eye of, engaged civil society, the democratization project is further safeguarded against potential backsliding.

This paper discusses two intertwined areas of post-2018 democratic reforms: the anti-corruption efforts and the attempts to reform the judiciary, aiming to contribute to academic literature on democratic consolidation. The narrow focus of the paper is on the role of CSOs in advancing democratic reforms. We use Armenia as a test case for the broader theory of the importance of civil society for democracy (Ackerman and DuVall, 2000; Diamond, 1999; Putnam et al., 1994; de Tocqueville, 2007 [1864]; Tusalem, 2007; Warren, 2001). We combine document and media analysis with qualitative interviews of key stakeholders to address the following Research Question: What was the role of civil society organizations in anti-corruption and judicial reforms in Armenia after the 2018 Velvet Revolution?

The next section presents the theoretical framework of the paper, followed by the discussion of the methodology and a background section that explains the 2018 Velvet Revolution and key political events of its immediate aftermath. We then shortly present the anti-corruption reform and the reform of the judiciary, focusing on vetting as its most contentious element. After that we present our analysis of the role of CSOs, divided by functions they attempted to perform. We argue that the difference in the levels of CSO expertise and the varied availability of allies partially explain the ability of CSOs to influence the anti-corruption reform while having less impact on judiciary reform.

2 Literature review

What enables democratic consolidation after an initial democratic breakthrough? The question can be addressed from a multitude of perspectives: from institutional engineering to congruent political culture, from sustained efforts by key players to overall conducive international and economic environment. This paper aims to contribute to the body of literature on democratic consolidation with a specific focus on interactions between the government and the reform-promoting CSOs, placing our work at an intersection of civil society, governance and policy studies.

Following (Diamond 1999, p. 221), we define civil society as “… the realm of organized social life that is open, voluntary, self-generating, at least partially self-supporting, autonomous from the state, and bound by a legal order or set of shared rules.” While civil society consists of both formal and informal entities aimed at advancing shaded interests (Anheier, 2004; Edwards, 2013), in this paper we focus on formal CSOs as the most visible players in policy processes.

Scholars of civil society have long argued that CSOs are important partners in promoting democratic reforms. The non-exhaustive list of civil society contributions to democratic consolidation includes interest representation, advocacy, reform expertise, recruiting political leaders, watchdog, and accountability functions (Diamond, 1999; Fung, 2003; Warren, 2001). Civil society actors can elevate the quality of public discourse, leading to better policy-making (Cohen and Arato, 1994; Habermas, 1996; Clemens, 1999; Berry, 1999). This study aims to test the extent to which Armenian CSOs were capable of performing some of these functions in the two policy cases under consideration.

All the great ideas of CSOs are worthless if the government is not inclined to listen. To explore the power balance between the government and the civil society we borrow the idea of political opportunities from social movement literature (Tarrow, 1994; Tilly and Tarrow, 2015; Giugni et al., 1999; Kriesi, 1995).

Political opportunities or political processes approach explains success or failure of social actors attempting to influence the government by focusing on broader political environment, such as openness of political system, nature of political cleavages, overall economic conditions, availability of allies, unity or division of elites, among many other factors (Meyer, 2004). To avoid overly broad application and concept-stretching of political opportunities (Rootes, 1999), we focus on the “opportunities for influence” approach (Meyer, 2004). More specifically, we focus on two distinct elements of political opportunity theory as predictors of policy impact: the window of opportunity, created by a specific event (the 2018 Velvet Revolution), and availability of key allies.

While it is hard to empirically estimate how long the window of opportunity lasts, we hypothesize that the likelihood of CSOs influencing policies diminishes with time, signaling the gradual closing of the window of opportunity. Having powerful allies increases the likelihood of policy influence. Policy champions in the new government, allies within civil society, and the EU are the three types of allies we focus on in this paper. The role of the EU as democracy promoter in the South Caucasus region is debated. While the EU explicitly promotes democracy through its normative commitments and specific projects, critics point to low efficiency of EU pro-democratic projects and potentially harmful neo-colonial tendencies (Luciani, 2021; Smith, 2011).

The focus of the paper on anti-corruption and judicial reforms stems from theoretical, methodological and applied policy considerations. From the theoretical point of view, corruption and complacent judiciary are two pillars of state capture (Hellman et al., 2000; Marandici, 2024). Dismantling systemic corruption and strengthening judicial independence is necessary for restoring democratic accountability and “leveling the playing field” for healthy democratic competition (Diamond, 1999; Levitsky and Way, 2010). Shedding light on this process in Armenia can contribute to more informed policies and processes in the country and elsewhere. From the methodological point of view, the two reform areas were selected to offer a contrast between more and less successful cases of CSO influence on policy.

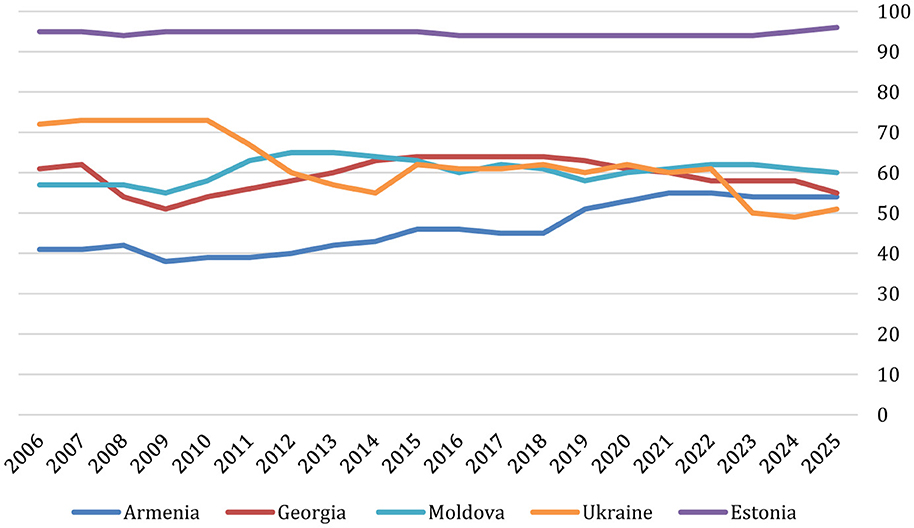

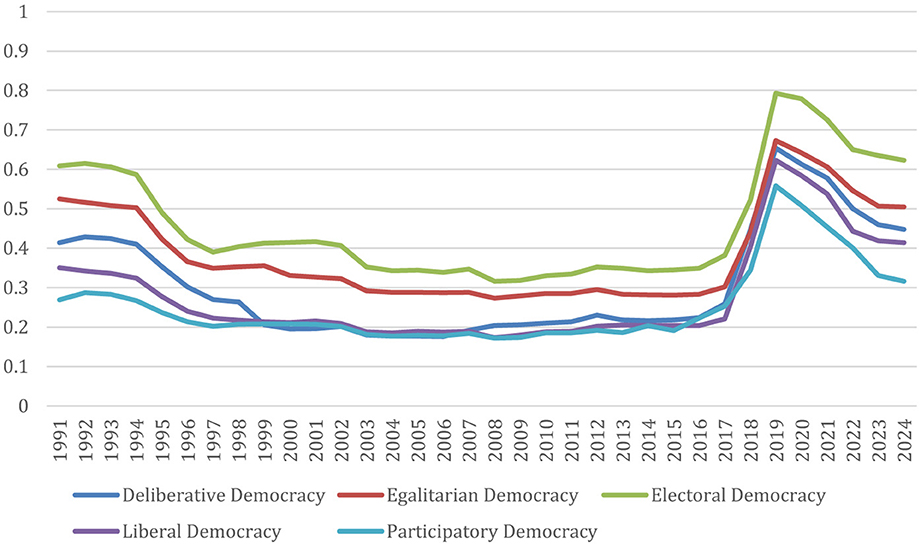

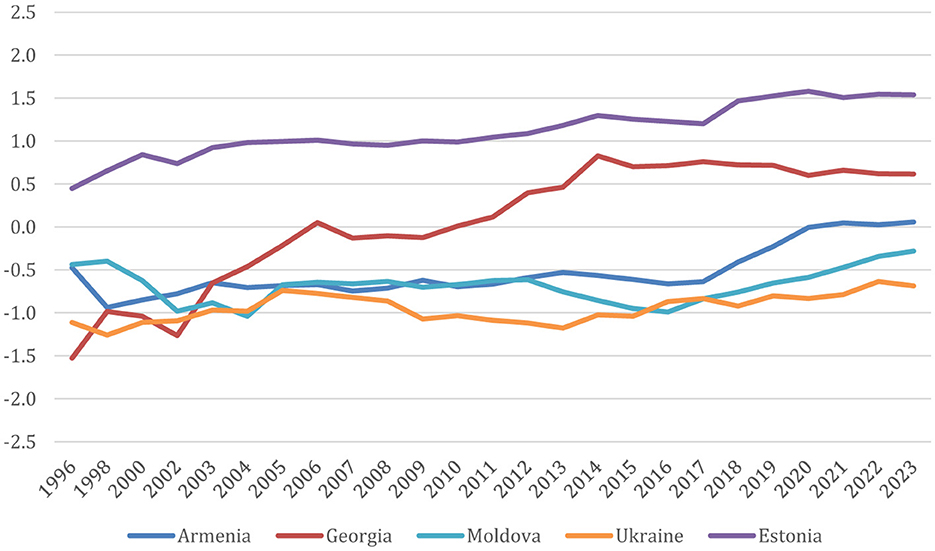

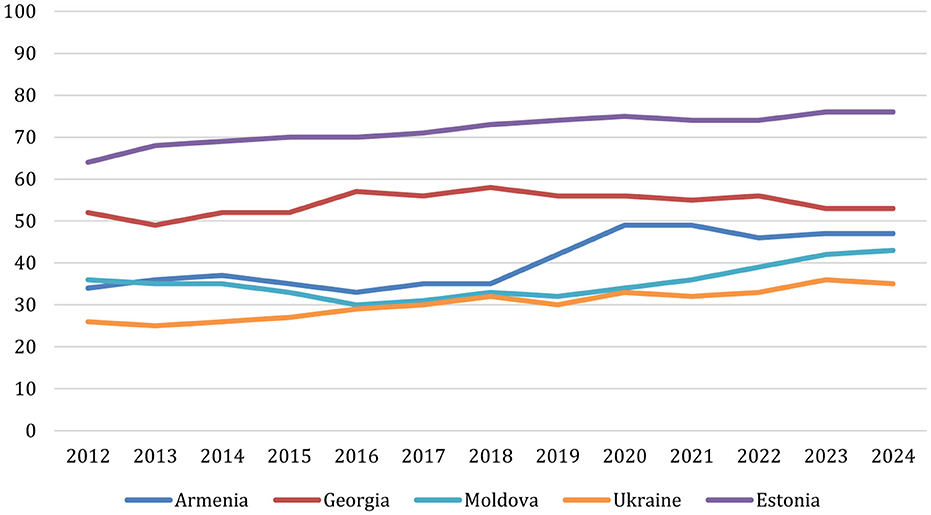

Armenian case fits into the broader context of post-Soviet (troubled and frequently derailed) democratization. Corruption and dependent judiciary are common features of post-Soviet space, except the Baltic states. Periodic attempts at re-starting the democratic project, often in the form of so-called color revolutions have, so-far, led to mixed and/or temporary results. Ukraine's Orange Revolution in 2005 is a poignant case of a failed democratic transition (Khodunov, 2022; Beissinger, 2013). Georgia's Rose Revolution of 2003 was long hailed as a successful case of democratic consolidation but recent developments in Georgia show democratic backsliding (Shyrokykh and Winzen, 2025). Moldova had at least two episodes of democratic backsliding and recovery; public resentment of corrupt Moldovan elite played a major role in episodes of contention (Marandici, 2024). Similarly to Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, Armenia experienced a popular uprising against state capture that resulted in democratic gains (see Figure 1). V-Dem data shows early signs of democratic backsliding (see Figure 2). Understanding factors that enable or block democratic consolidation is crucial for preventing further setbacks and improving Armenia's, and other similar countries', chances for a democratic future. The role of civil society in this complex process is one piece of a puzzle this paper tries to illuminate.

Figure 1. Freedom House freedom in the world scores (0–100 most free). Source: https://freedomhouse.org/country/scores.

Figure 2. V-Dem democracy indexes (0–1 hight). Source: https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/.

3 Methodology

The paper investigates the following Research Question: What was the role of civil society organizations in anti-corruption and judicial reforms in Armenia after the 2018 Velvet Revolution? More specifically, based on literature discussed above, we attempt at tracing and describing the empirical manifestations of the following functions: (1) interest representation, advocacy and accountability; (2) reform expertise; (3) recruiting political leaders. Based on insights from political opportunity literature, we formulated the following hypothesis:

H1. CSOs had more policy impact when their policy proposals were supported by powerful allies, such as influential government officials, other CSOs or civil society coalitions and/or the EU.

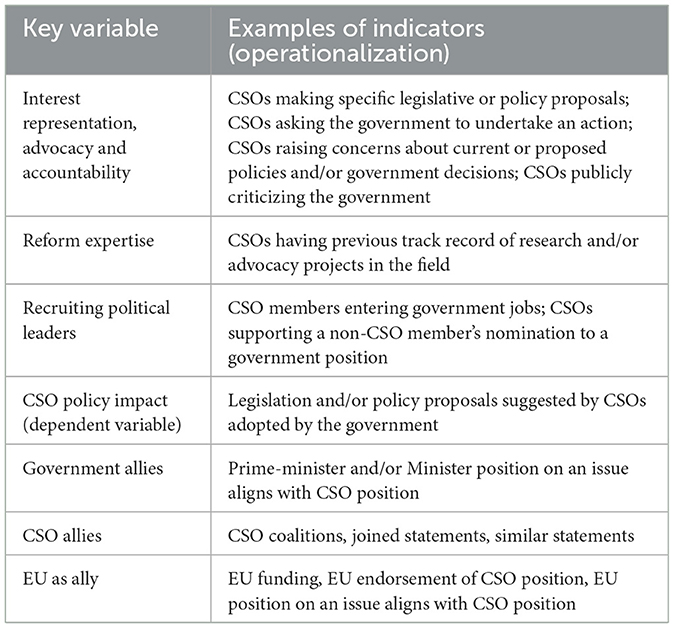

We rely on document analysis, media analysis, and eight qualitative interviews with government officials, civil society representatives and policy experts in an attempt to unpack the role of CSOs in pushing for anti-corruption and judiciary reform in the aftermath of 2018 Velvet Revolution,2 relying on indicators listed in Table 1. We also rely on quantitative scores from reputable institutions (V-Dem, Freedom House, and Transparency International) to situate our cases in a broader picture of overall progress, stagnation or backsliding of reforms under consideration.

Eight semi-structured interviews with key informants were conducted from April 12th to June 12th, 2024, four of them in person and four online. Participants were selected following an evaluation of policy documents and media reports on anti-corruption and judiciary reform, based on their involvement or recognized expertise. Additional names were solicited through snowballing. Several unsuccessful attempts were made to contact representatives of the EU in Armenia.

The fieldwork was part of a larger project (EMBRACE)3; we used the questionnaire provided by our consortium partners, adapting it to suit the Armenian reality and the two reform areas we focused on. The average interview duration was 32 min. All interviews followed a standard ethical protocol of informed consent and were transcribed with assurance of data confidentiality. The transcription was followed by thematic qualitative data analysis.

In addition to reviewing key policy documents and conducting qualitative interviews, we attempted a review of key statements about vetting of judges, delivered by either the Prime Minister or the Minister of Justice. Most relevant media pieces were found by searching archives of news agencies in Armenia. Major news organizations such as Armen press, Hetq, News.am were searched for the term “vetting.” Identified articles were taken for analysis. Generally, all news agencies reported in varying detail about the same events. The approximate number of unique articles used to build the chronology was around 30.

Our inability to secure an interview with an EU representative is a major limitation of this research. The position and the influence of the EU—one of the key allies in our theoretical framework—is captured indirectly through interviews with other stakeholders and analysis of reform-related documents. Conducting only eight interviews is a limitation as well. We miss some potentially important perspectives of those who did not respond to our multiple interview requests. Moreover, our operationalization of key variables is far from comprehensive. Much of it was derived inductively from the data in the process of analyzing the cases, as an open endeavor of trying to make sense of a complex and messy policy process. A more rigorous and detailed conceptualization and operationalization of variables, and inclusion of other key variables we probably overlooked, would certainly result in a deeper and more accurate understanding of CSO influence on post-revolutionary policy processes. Our work remains largely exploratory and descriptive. We hope the themes we explore and the questions we leave unanswered would lead to further, more informed analysis.

4 Background: the Armenian Velvet Revolution 2018

In 2015, the governing Republican Party initiated a constitutional referendum that would transition Armenia from a semi-presidential to a parliamentary system. The opposition criticized the move as an attempt by the governing party, and specifically President Serzh Sargsyan, to remain in power after his two presidential terms would lapse. The President publicly announced that he would not attempt to become the prime minister after the transition. In the spring of 2018, he broke that promise and accepted the nomination by the Republican Party to become the first prime minister of the newly created parliamentary republic. A call for him to honor his promise and step down was the spark of the Velvet Revolution.

A loose coalition of political opposition figures and civic activists led mass protests in Yerevan (the capital) and elsewhere in the country. An opposition MP Nikol Pashinyan was the most visible leader of the protest. His platform was mostly centered around populist sentiments such as long-standing distrust in elected leaders, as well as playing on existing narratives of widespread and entrenched corruption. The movement started resonating with broader segments of society and growing in numbers when civic activists joined (Paturyan, 2020). In 2 weeks, mass peaceful protests brought the capital to a standstill. On April 23rd, Serzh Sargsyan resigned. Pashinyan became the Prime Minister. The power transition was completed in December through snap parliamentary elections. Pashinyan's “My Step” alliance won 70% of the votes (Muradian, 2018).

The new Armenian government announced an ambitious democratic reform agenda, including fight against corruption and reform of the judiciary. The future seemed bright. The excitement and the optimism, however, were short-lived. COVID-19 presented a serious challenge to the new government's ability to move forward with reforms. While its impact on anti-corruption reform was likely minimal, the pandemic forced the government to halt and eventually cancel a referendum to end powers of seven out of nine Constitutional Court judges. Pashinyan's government saw these judges as the representatives of the previous corrupt regime. The standoff between the government and the Constitutional Court was partially resolved through a parliamentary bill that removed three judges (Mejlumyan, 2020b). In the long run COVID-19 undermined public trust in government (Paturyan and Melkonyan, 2024), reducing its ability to implement reforms. Sadly, COVID-related problems were almost completely driven out of public mind by the next calamity of the 2020.

In September 2020, Azerbaijan launched a full-scale military offensive against the self-proclaimed Artsakh Republic. Armenia was indirectly involved in the conflict. After 44 days of heavy fighting, half of the Artsakh was overrun. The human losses were significant. Armenia and Azerbaijan signed a Russian-brokered ceasefire, perceived as a decisive loss for the Armenian side, sparking outrage against Pashinyan's government among large segments of the population. Many were disillusioned or numb with grief. The country went into a downward spiral of anger and fear. Autocratic Azerbaijan's war rhetoric, further attacks on the Armenian border and claims for Armenian territory did not help the matter.

Many political and social actors called for Pashinyan's resignation. Protests against the government gathered moderate support. Pashinyan called for snap elections in June 2021 and secured another victory with 54% of the votes (Manougian, 2021), and the mandate to continue democratic reforms and peace negotiations with Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, Armenia's traditional security provider—Russia—invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The Russian-Ukrainian war dragged on, distracting Russia from the South Caucasus.

In September 2023, Azerbaijan launched another attack against what remained of Artsakh. The presence of Russian peacekeepers did nothing to deter the complete collapse of Artsakh; 100,000 people fled the region, leaving it depopulated. These tragic events led to another round of disappointment and anger toward Pashinyan's government. The post-revolutionary government failed in the security of the Artsakh and, fears are, might fail in providing security for the Republic of Armenia proper. In the face of such serious drawbacks, it bases its claim for legitimacy on commitment to democracy.

At a time of global democratic retreat, Armenia is among the few countries that registered some democratic progress after 2018. Figure 1 depicts Freedom House Freedom in the World Scores for Armenia and three other post-Soviet countries that experienced similar popular uprisings: Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Estonia is also plotted on this and subsequent graphs as an example of a successful post-Soviet democratiser. Figure 1 shows an increase in freedom in Armenia after 2018 (from 41 to 51 and later to 55 in 2022), which afterwards slightly decreases (from 55 to 54 in 2023–2025). In the Freedom House Nations in Transit 2024 Report Armenia's National Democratic Governance rating fell from 2.50 to 2.25, reflecting “the executive's consolidation of power, the multiyear trend of central authorities overreaching …, and the lack of transparency in ruling party finances” (Freedom House, 2024). V-Dem five types of democracy indexes, depicted in Figure 2, increase in the aftermath of the 2018 Velvet Revolution but start declining after that.

Given the democratic gains, the double challenge of COVID-19 and war, the recent signs of possible backsliding, and the trends in other post-communist countries with similar experiences, it is important to understand the specifics of key reforms, aimed at preventing re-capture of the state through corruption and regime-loyal judiciary. CSOs can play an integral role pushing for democratic consolidation against serious odds. The rest of the paper discusses the two reforms and the level of CSO involvement in each.

5 Anti-corruption reforms: visible progress

After assuming power, Pashinyan formed a government of relatively young individuals with experience in CSOs or international organizations but minimal prior public office exposure (Nikoghosyan and Ter-Matevosyan, 2023). Post-Velvet Armenian government embarked on an ambitious anti-corruption reform, declaring complete eradication of corruption as one of its goals (Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Armenia, 2023).

With advice from civil society, the government embarked on creating several new institutions and legal acts aimed at strengthening both the prevention and the punishment sides of the anti-corruption policy framework (Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Armenia, 2023, p. 4). The Corruption Prevention Commission (established in 2019) is mostly responsible for integrity checks, including asset declarations, conflicts of interest and party finance. The Anti-Corruption Committee (established in 2021) is an investigative body with special powers to examine suspected corruption cases. The Anti-Corruption court (established in 2022) “handles cases that fit under the country's legal definition of corruption” (Hallock and Ghahramanyan, 2024). The Anti-Corruption Chamber (established in 2019) and the Anti-Corruption Court of Appeals (established in 2023) handle appeals on final corruption-related court decisions. Anti-Corruption Policy Council (established in 2019) is headed by the Prime Minister and includes civil society representatives. It deliberates on broad anti-corruption policies and future course of action. The Ministry of Justice has an Anti-Corruption Policy Development and Monitoring Department (established in 2020), charged with developing, implementing and monitoring anti-corruption strategies, policies and processes, including fulfillment of international commitments. According to Hallock and Ghahramanyan (2024), post-2018 Armenia has a “well-developed anti-corruption infrastructure.”

In addition to upgrading the anti-corruption institutional framework, Pashinyan's government initiated a series of trials targeting former senior officials, including ex-presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, as well as other high-ranking figures. The most recent case is the arrest of Russian-Armenian billionaire Samvel Karapetyan in June 2025. Current charges against him are both political (public calls to seize power) and economic (money laundering) (Pracht, 2025). However, these arrests and investigations have so far not resulted in court verdicts. It is still uncertain whether these efforts will extend beyond selective prosecutions to consistently enforce a “zero tolerance for corruption” policy (Terzyan, 2020). Critics of Pashinyan regime voice concerns about the legality of these arrests and proceedings, seeing them as warning signs of democratic backsliding.

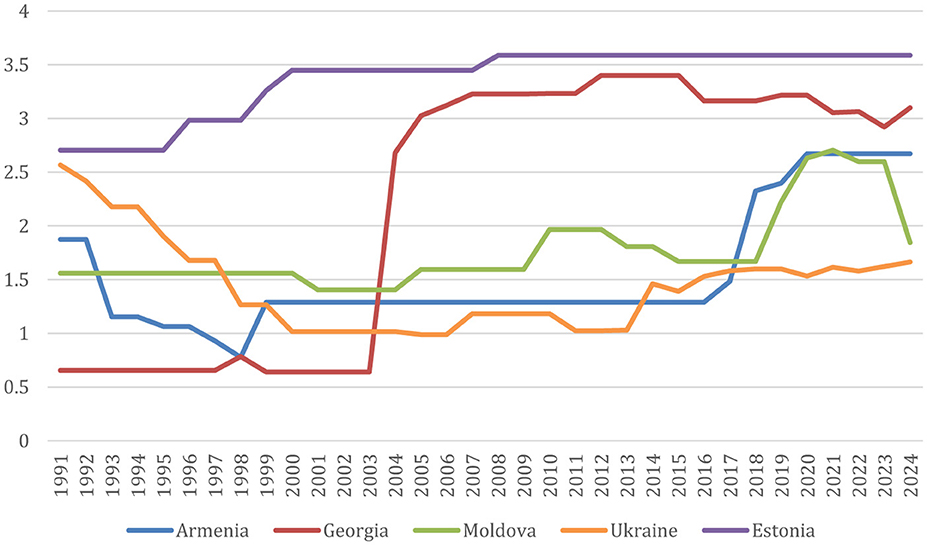

Overall, Armenia saw substantial improvements in its international anti-corruption rankings. World Bank Control of Corruption in Armenia improved from −0.64 in 2017 to −0.41 in 2018 and 0.06 in 2023 (see Figure 3). Transparency International Corruption Perception Index improved from 35 in 2018 to 42 in 2019 and 49 (highest score so far) in 2020 (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. World Bank world governance indicators control of corruption (−2.5 to 2.5 no corruption). Source: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators#.

Figure 4. Transparency International corruption perception index (0–100 no corruption). Source: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024.

6 The attempts to reform the judiciary: announcing and abandoning vetting of judges

Before the Velvet Revolution, the Armenian judiciary branch was weak and dependent on the executive, with common and systemic occurrences of bribery and leveraging political influence (Aghekyan, 2018). The reform of the judiciary was high on the new government's agenda. Civil society offered its expertise. One issue that became a clear focus of contention was the vetting of judges. Since the judicial reform is a very broad topic, we focus on vetting as both a narrower and a more interesting case of controversy, disagreement between key players and partial success, as described below.

Vetting involves assessing current officeholders to ensure they meet the highest standards of conduct and integrity. It includes both integrity checks and criminal investigations. Integrity checks assess potential future misconduct with evidence based on the balance of probability. Criminal investigations aim to determine if a crime has occurred, requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt, with the state bearing the burden [European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission), 2022].

In 2019, Prime Minister Pashinyan presented his vision for judicial reform during a meeting with legislative, executive, and judicial representatives. Pashinyan highlighted the long-standing distrust of the judiciary by the Armenian people, viewing it as a continuation of the old, corrupt system. Pashinyan advocated for a critical reform: vetting all Armenian judges. This vetting process would provide comprehensive insights into judges' political affiliations, genealogy, property status, and personal and professional conduct, ensuring transparency and accountability within the judiciary (Pashinyan, 2019). As discussed below, during the year following this announcement, the Armenian government gradually backtracked from this idea.

Following Prime Minister's announcement, parliamentary hearings were convened under the theme “Prospects of Applying Transitional Justice Tools in Armenia.” However, these hearings failed to yield significant results. The Justice Minister was replaced shortly afterwards. The new Justice Minister worked on an extensive 2019–2023 Strategy for Judicial and Legal Reforms in collaboration with CSOs and international bodies, including the Venice Commission (Mejlumyan, 2020a).

In May 2020, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Justice Minister Rustam Badasyan explained the challenges of implementing vetting processes in Armenia. During a live broadcast, Minister Badasyan highlighted that conducting a comprehensive, immediate review of all judges could lead to adverse effects. He advocated for a “gradual rehabilitation of the judicial system.” The Ministry proposed establishing a commission to assess judges' performance. This five-member commission evaluated judicial activities, supported the advancement of promising candidates through the service promotion list, and identified strategies for enhancing judicial effectiveness (Karapetyan, 2022).

In 2021 the Armenian Parliament passed a new Judicial Code, aiming to incrementally reform the judicial system while avoiding the pitfalls of a rapid wholesale vetting process (Karapetyan, 2022). This document shows that the government moved away from the more radical idea of vetting, advocated by some CSOs and legal experts, toward a more gradual process. In July 2022, the government adopted the Judicial and Legal Reforms 2022–2026 strategy, where vetting was absent (Karapetyan, 2022).

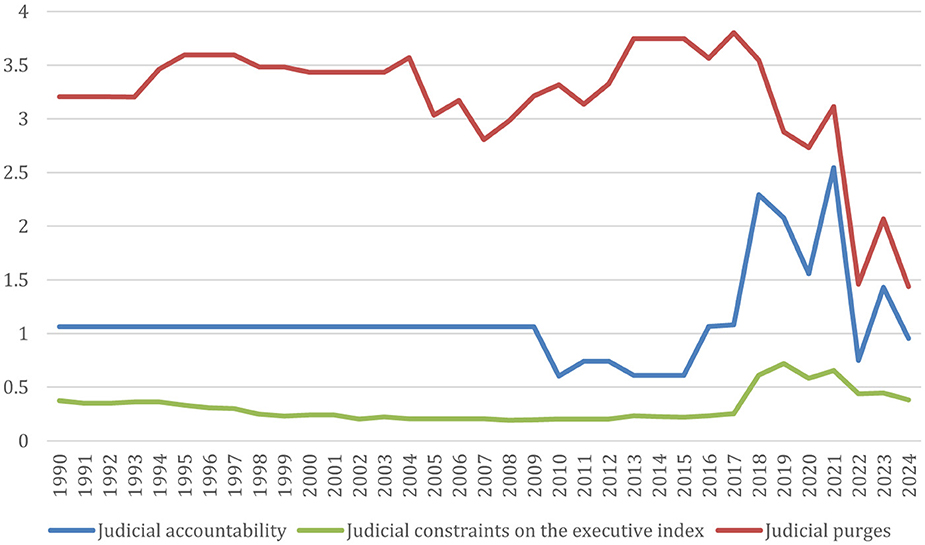

Nonetheless, some changes in the judicial system are underway. The head of the Supreme Judicial Council4 notes: “Within the framework of the much-discussed and demanded judicial vetting, huge dismissals and appointments of judges took place. Thus, 200 of the 309 currently serving judges were appointed after the 2018 revolution” (Shant News, 2023). Expert-based V-Dem data seems to suggest many of these removals were arbitrary, especially between years 2020 and 2022. The responses to the Judiciary purges variable, plotted in Figure 5 vary from 0 (there was a massive, arbitrary purge of the judiciary) to 4 (judges were not removed from their posts). The index of Judicial accountability, aimed at measuring “When judges are found responsible for serious misconduct, how often are they removed from their posts or otherwise disciplined?” assessed by experts on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always) follows a similar pattern. We see an increase in judicial accountability right after the Velvet Revolution and then a plunge, coinciding with arbitrary judicial purges. The judiciary constraints on the executive (“To what extent does the executive respect the constitution and comply with court rulings, and to what extent is the judiciary able to act in an independent fashion? From low to high” in V-Dem's terminology) were low before 2018. The graph below shows a steep increase (corresponding to improved judiciary's ability to constrain the executive) after the Velvet Revolution with a jittery decline afterwards.

Figure 5. V-Dem judicial accountability-, power- and independence-related scores for Armenia. Source: https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/.

Despite setbacks in the judiciary reform, the overall anti-corruption efforts seemed to have a positive impact on the judiciary branch. V-Dem Judicial corruption decision variable that asks experts to assess “How often do individuals or businesses make undocumented extra payments or bribes in order to speed up or delay the process or to obtain a favorable judicial decision?” on a scale from 0 (always) to 4 (never) shows improvements in Armenia since 2018, as evident from Figure 6.

Figure 6. V-Dem judicial corruption decision (0–4 never making corruption-induced decisions). Source: https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/VariableGraph/.

7 Analysis: the role of civil society in post-velvet reforms

7.1 Interest representation, advocacy and accountability

Between the Velvet Revolution and the 2020 war, the pro-democratic Armenian civil society actors found themselves in an interesting situation. They had a relatively sympathetic government, committed to democratic reforms. New government members adopted a more open and engaging approach toward CSOs (Margaryan et al., 2022). Yet it was unclear how much and how fast the government is willing (or able) to move on specific issues advocated by civil society. Moreover, there was a question of internal feedback vs. open criticism. Would criticizing a young, inexperienced pro-democratic government play into the hands of an undemocratic opposition waiting for its chance to return to power and reverse the democratic gains? CSOs initially appeared to withhold sharp criticisms, allowing the new government space to adapt. That, however, changed with time. One of the most critical CSO leaders we interviewed remarks:

This government at first was thinking that it was democratic… Due to our serious efforts, these reports [Amnesty International, Transparency International, Freedom House] show decline [of democracy]. And this had a bit of a disciplining effect on the current government. Because that manipulative thing that we are democratic and we don't have anything to do in that direction anymore, that tendency has evaporated… This trick won't work anymore (Interviewee 3, CSO leader).

Similarly, our interlocutor from the government noted the increasingly demanding attitude of CSOs that shifted from a milder early post-2018 position to a more assertive position.

After 2018, it [civil society] had more, like, trust in the government. This was visible. Because it's no secret that from the civil society ranks many transitioned to executive and legislative bodies. But now we see that the civil society has sharpened its demands, and became more demanding. It probably comes from that they really see both the political will and the possibilities to carry forward, to push forward their suggestions (Interviewee 8, government employee).

Some prominent Armenian CSOs actively collaborated with the government on formulating the post-velvet Anticorruption Strategy and its Implementation Action Plan in November 2018–October 2019. According to the Armenian Lawyers Association website, during this period, a total of 133 recommendations were made by CSOs; 101 of these were accepted fully, accepted partially or at least considered. The collaboration took place within the EU-funded “Commitment to Constructive Dialog” project (Armenian Lawyers' Association, 2019). This is a visible case of successful advocacy with EU as an ally. In another traceable case of advocacy, at least two CSOs were involved in the process of formation of the Anti-Corruption Court by monitoring the process and publishing a report (Protection of Rights Without Borders, 2023).

In the case of vetting some of the more prominent CSOs developed their own suggestion package calling for an urgent, comprehensive, effective, and genuine vetting. This document was developed by independent specialists, considering the country's needs, and the experience of several countries that had implemented transitional justice mechanisms. CSOs asserted that impartial vetting must be conducted by an independent, multi-stakeholder entity, utilizing transparent criteria. However, they warned that the vetting process could become an occasion for partisan or political abuse (Helsinki Citizens' Assembly - Vanadzor, 2020). In May 2020, CSOs presented their suggestions to the government (Karapetyan, 2022).

The CSO advocacy function was visible in both anti-corruption and vetting reforms. CSOs developed policy proposals and, in the case of vetting, urged the government to proceed with more speed while also warning it against abusing its power. However, as the next section demonstrates, there were differences in (perceived or actual) expertise behind the policy proposals in two respective cases.

7.2 Reform expertise

As discussed above, CSOs have more institutional access to anti-corruption reform policies, through participation in various high-level policy forums. According to our respondent from the government, civil society representatives are engaged in both the Anti-Corruption Policy Council chaired by the Prime Minister and a broader Anti-Corruption Programs Working Group, which work within the Ministry of Justice. A quick check of meeting records of the former shows some very prominent CSOs with track record of anti-corruption research and/or advocacy. This is not surprising, because anti-corruption is a well-established and well-funded field of CSO activities. Some of the oldest Armenian CSOs specialize in this area. The same cannot be said about vetting. While some CSOs have developed expertise in a broader field of human rights, judicial reform and, more specifically, vetting was not high on anyone's agenda prior to 2018. Understandably, CSOs lacked expertise. Our government interlocutor observes:

…I see a very big difference in the potential of civil society in the field of anti-corruption and the judicial sphere. In the judicial sphere, mostly lawyers and advocates are involved and maybe that's right, but civil society is not that specialized, there is one-two organizations. We have that difference between anti-corruption and judicial [sphere] (Interviewee 8, government employee).

A legal expert working for a politician (Interviewee 5) echoes this sentiment, stating that, in their opinion, there is not a single CSO in Armenia that could develop as much as a solid concept note on vetting. Another independent legal expert (Interviewee 7) was skeptical as well, noting the lack of specialization of CSOs. Looking at CSOs that proposed the vetting suggestion package, mentioned above, some of these concerns about lack of narrow policy expertise seem warranted.

In terms of reform expertise, our analysis shows that CSOs had stronger prior track record in anti-corruption field. They had early access to the decision-making through their input to Anticorruption Strategy and its Implementation Action Plan as early as November 2018 and through the Anti-Corruption Policy Council established in 2019. In the case of vetting, they reacted to government proposal but their expertise was questioned.

7.3 Recruiting political leaders

Pro-democratic civil society actors embraced the Velvet Revolution and supported Pashinyan's democratic reform agenda. The movement's victory allowed civil society to assume a significant consultative role in the transitional government, resulting in many civil society members entering government positions (Freedom House, 2019). Several of our interviewees also confirmed that after the revolution, many representatives from non-governmental organizations became a part of the government.

Unlike neighboring Georgia after its 2003 Rose Revolution, however, there was less brain drain from civil society to the newly formed government, allowing Armenian civil society to maintain some distance from the government and to continue its watchdog function (Stefes and Paturyan, 2021). Moreover, according to our interviewees, some individuals who initially joined the executive or legislative branch later resigned and returned to civil society.

After the revolution, a number of our former colleagues got government positions. But we tried to find a border between us and our former colleague government officials so that we don't get confused, yes, and that we would not be associated [with them] and so that the division is clear because that was important for us so that we ourselves can be more objective and not restricted in our approaches (Interviewee 4, CSO leader).

Interestingly, the human capital impact of civil society on the newly formed government was not only in terms of supplying officeholders, but occasionally, CSOs were able to block appointments with which they disagreed. According to our interviewees, a coalition of CSOs “made noise” and prevented a judge with a questionable reputation from being appointed to a newly created Anti-Corruption Court.5

7.4 Allies and alliances

The more cordial relationship between the government and the civil society, partially facilitated by personal connections, created additional avenues for CSO advocacy. Our interlocutors acknowledge that there are now more opportunities “for constructive dialogue” through direct policy input. “What we say is being listened to more often.” (Interviewee 4, CSO leader). However, there are also disappointments and a learning curve on both sides of the proverbial “table,” as evident from the quote below:

At some point, there were certain disappointments because there were expectations; they [government officials who were CSO members before] used to be our colleagues, and then they went to the government, and we had quite high expectations that changes would be made. So maybe there are also some objective factors here because the reforms in the bureaucratic system are one thing; another thing is how the operation is done in non-governmental organizations (Interviewee 2, key CSO staff member).

While the government is more open to CSOs in general, it seems to be more open and “on the same page” in case of anti-corruption reform. As already discussed above, the government demonstrates political will to fight corruption through a number of newly created institutions, and invites the CSOs to participate at various levels. In the case of vetting, the government backtracked from its original position. It is hard to classify it as an “ally” of CSOs, because CSOs themselves were divided on the issue. While some CSOs advocated for transitional justice and thorough vetting, others expressed caution. Some were concerned that vetting could paralyze the judicial system. Others were worried about the revolutionary government's lack of expertise or questioned their impartiality. By contrast, our analysis does not reveal strong divisions among CSOs in anti-corruption policy, which highlights another difference between the two policy reforms studied.

The role of the EU in anti-corruption and vetting reforms differs substantially. The EU was a clear ally in the case of anti-corruption policy reforms. As mentioned above, it funded “Commitment to Constructive Dialog” project, which empowered CSOs to propose recommendations to the Anticorruption Strategy and its Implementation Action Plan. Many of these recommendations were accepted. Overall, the EU consistently and openly advocates for clean government. With vetting, however, the EU involvement is harder to describe. We have indirect evidence of various EU institutions cautioning against vetting. One such indirect mention is evident in the quote below:

We did a lot of research at the time, Bosnian example, Ukrainian example, and so on, Albanian example if I recall correctly. And it was concluded that, and the colleagues from the Council of Europe also emphasized that constantly, that vetting should not be done in Armenia… (Interviewee 7, legal expert).

News reports reviewed as part of the study also point to criticism of the original vetting reform by the Venice Commission. In general, the EU's approach seemed to be much more cautious.

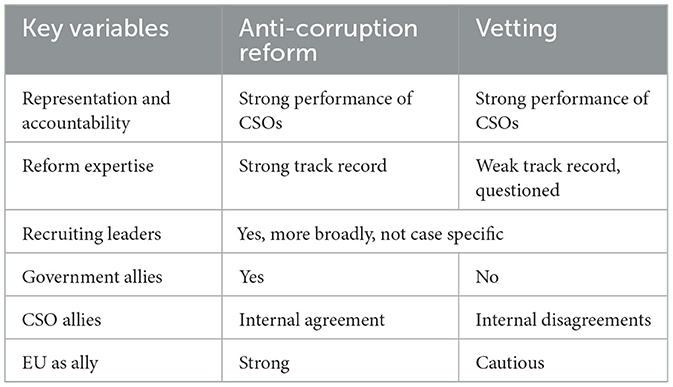

Comparing the two cases, we can see the differences in some of the elements analyzed, as depicted in Table 2. It seems that CSOs were better positioned to influence the anti-corruption reform, as compared to the vetting reform, given their stronger reform expertise track record, alignment with government priorities, internal coordination and support from the EU. While we cannot claim that these exact factors fully explain the relative success of the anti-corruption reform, these findings align with the actual reform outcomes. We have clear evidence of CSO proposals being accepted and an overall quantitative indications of anti-corruption progress in the country, as discussed above.

To answer our Research Question, Armenian CSOs contributed substantially to post-Velvet anti-corruption reforms by participating in government-led institutionalized discussion forums, collaborating with the government on key documents, and providing implementable suggestions. Some of this involvement was facilitated by EU funding. The government demonstrated political will to reduce corruption by creating new institutions and strengthening the legislative framework with the tangible input from the CSOs. Contrasting anti-corruption and vetting, we find support for our Hypothesis. In the case of anti-corruption reform CSOs had powerful allies in the government, spoke with one voice and had the support of the EU. As a result, they had clearly documented policy impact. In the case of vetting, CSOs lacked such powerful allies and disagreed amongst themselves, resulting in negligible policy impact.

Our research also shows that the window of opportunity, created by the Velvet Revolution, did not last. According to one of our interviewees, “There was an intermediate period after 2018: 6 months to 1 year where there were more opportunities but then closed and now there are fewer than before” (Interviewee 1, CSO head). “It's becoming even more and more difficult to cooperate, to tell the truth. If we compare the situation with several years ago, now it is becoming more and more difficult to cooperate” (Interviewee 2, key CSO staff).

8 Conclusion

Our study of anti-corruption and judicial reforms in post-2018 Armenia aligns well with Karatnycky and Ackerman's (2005) findings that most democratic gains occur during the first few years of transition. It shows active attempts by CSOs to engage with the new self-proclaimed democratic government to push for democratic consolidation by strengthening institutions and legislative frameworks during the short window of opportunity created by the critical juncture of regime transformation. Our findings demonstrate that CSOs became much more active in direct policy proposals, while continuing to perform their advocacy and watchdog functions (the latter being initially somewhat muted).

The post-Velvet period in Armenia can be divided into two stages: the initial, more “trusting,” stage and the second stage where civil society became more demanding. The explanations differ. For the most critical CSOs, it was a change from high hopes to dashed hopes. Some of our respondents said they initially held back criticism, wanting to give the government the time to do things and also not wanting to undermine them but after a while they understood they needed to get back to their watchdogging as rigorously as before. Our interlocutor from the government has the opposite explanation: civil society became more demanding because they saw they can be more demanding.

This raises an important question of importance of trust vs. importance of healthy skepticism for democratic consolidation. Many studies focus on trust as an asset and a positive factor that allows democracies to function (Almond and Verba, 1963; Putnam et al., 1994; Putnam, 2000). Other scholars caution against unwarranted trust (Norris, 1999; Hardin, 2002; Krishnamurthy, 2015). This scholarly debate resonates with the current political discussions in Armenia about the unprecedented extent of public trust placed in Pashinyan's government right after the 2018 and whether that trust was warranted.

Comparing the two policy cases, we find differences in the process and the outcomes of the anti-corruption and the judiciary reforms. That can be explained by a number of factors. Anti-corruption effort was much more uniting, seen as noble and easy to rally key players around. It also registered clear progress with a plethora of new institutions and legal acts resulting in visible improvement in scores (see Figures 3, 4). Vetting, on the other hand, was controversial; some wanted it and saw it as absolutely necessary, others had misgivings about how it should and could be done in Armenia. Some of our interview participants described it as a “dirty” and “thankless” task. While the role of international experts and donor organizations in Armenian anti-corruption and judiciary reforms needs further analysis, our interlocutors suggest that the EU, in particular, played a moderating role on a judicial reform proposal that was potentially too radical. Whether this is helping or hindering the reform is to some extent in the eye of the beholder.

Armenian civil society involved in anti-corruption activities is stronger, with years of accumulated expertise and ability to speak with one voice; the judicial reform sees more participation from within-the-field professionals, lawyers, and advocates; there is much less civil society expertise there. That might be another explanatory factor of why anti-corruption reform was more successful.

In the anti-corruption reform, there is a good alignment between, political will, strong and competent civil society, steady attention and technical support of international organizations, including the EU. In the vetting reform, civil society was divided at the desired scope of the reform and was less capable professionally. The government made a bold announcement of vetting and then back-tracked while the EU had a moderating, cautious position. That would explain the difference in the outcomes.

Overall, Armenia is a case of critical juncture (the 2018 Velvet Revolution) followed by a window of opportunities for reform. CSOs attempted to push for democratic reforms to seal the regime transition. A united front of credible and experienced CSOs, encouraged by political will and international support allowed the CSOs to make a substantial contribution to the anti-corruption reforms. In contrast to that, divisions over the extent and the speed of the desired judicial reform, the moderating role of international experts, and government backtracking combined with perceptions of weak CSO expertise in the judicial field, limited CSOs abilities to push for judicial reforms. These findings contribute to our broader understanding of the role of civil society in the early years of democratic transition. Civil society does not just mobilize people in the streets. It provides expertise and much needed criticism. Its success, however, is contingent on a number of factors. This paper tried to unpack some of them and found that the difference in CSO expertise mattered, as did the availability of allies.

Our study leaves a number of unanswered questions. The exact meaning and scope of vetting that was initially proposed and gradually modified could be tracked more accurately through comparing consecutive relevant policy documents. While it is somewhat outside the scope of this paper, it would provide valuable insights into the dynamics of a complex and controversial reform. Further research could also include a more detailed analysis and comparison of Armenian pre- and post-Velvet anti-corruption institutions, their power, staff and appointment procedures, including the non-trivial role of the Prosecutor's Office in anti-corruption.

As Armenia, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine and many other countries grapple with day-to-day challenges of strengthening democracy, we look to civil society as a source of democratic renewal. As scholars, we hope to advance our understanding of factors and processes, leading to stronger civil society voices resulting in more comprehensive democratic reforms, potentially improving our chances for a better future.

Data availability statement

The anonymous raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the corresponding component of our study was a replication of broader EU-funded research. The broader research went through rigorous ethics checks and approvals by Sarah Anne Rennick and Dr David Aprasidze. Our part (interviews with local stakeholders) was conducted and supervised by scholars regularly re-trained in ethical social science research who were careful to observe both EU-mandated regulations and specificities of local fieldwork. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YP: Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. LS: Data curation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GP: Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research project was funded by the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation program: grant agreement ID: 101060809.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the opportunity to be part of the EMBRACE scholarly consortium that contributed to our professional grow. We are very grateful to our research participants for dedicating time and providing their insights. Mariam Galstyan and Irena Grigoryan of the American University of Armenia BA in Politics and Governance program also supported us during research and writeup of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Artsakh is the indigenous Armenian name for the territory internationally known as Nagorno Karabakh. It was part of Soviet Azerbaijan, mostly populated by Armenians. In 1988 a movement for unification of Artsakh and Armenia started. It resulted in several wars, 30 years of de-facto independence of Artsakh republic and a complete collapse of it, followed by an ethnic cleansing in 2023.

2. ^The two reform areas, which this paper focuses on, are intertwined to a large extent because the Ministry of Justice is the main government stakeholder in the case of vetting of judges and is also highly involved in anti-corruption strategy and implementation, making it the main state actor in both cases. Also, many of the key CSOs are equally involved in both. The vetting case is often discussed in the broader context of anti-corruption.

3. ^The project aims to advance democracy in the European neighborhood and overcome the obstacles to democratization. It is funded by the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation program: grant agreement ID: 101060809. https://embrace-democracy.eu/.

4. ^The Supreme Judicial Council is an independent state body that, according to the Armenian Constitution, guarantees the independence of courts and judges. It suggests appointments and promotions of judges, makes disciplinary decisions and can terminate the powers of a judge.

5. ^The judge, Mnatsakan Martirosyan, did receive another promotion later (https://www.azatutyun.am/a/32248096.html).

References

Ackerman, P., and DuVall, J. (2000). A Force More Powerful: A Century of Non-Violent Conflict. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Aghekyan, E. (2018). Armenia: Nations in Transit 2018 Country Report [WWW Document]. Freedom House. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/armenia/nations-transit/2018 (Accessed March 6, 2024).

Almond, G. A., and Verba, S. (1963). The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes in Five Western Democracies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400874569

Anheier, H. K. (2004). Civil Society: Measurement, Evaluation, Policy. Oxford: Earthscan Publications.

Armenian Lawyers' Association (2019). The Armenian Lawyers' Association and the CSO Anti-Corruption Coalition of Armenia have had huge involvement and impact on the process of adopting the anti-corruption strategy [WWW Document]. Available online at: https://armla.am/en/5206.html (Accessed July 6, 2024).

Beissinger, M. R. (2013). The semblance of democratic revolution: coalitions in ukraine's orange revolution. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 574–592. doi: 10.1017/S0003055413000294

Berry, J. M. (1999). “The rise of citizen group,” in Civic Engagement in American Democracy, eds. T. Skocpol and M. P. Florina (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press), 367–393

Clemens, E. S. (1999). “Organizational repertories and institutional change: women's groups and the transformation of American politics, 1890-1920,” in Civic Engagement in American Democracy, eds. T. Skocpol and M. P. Florina (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press), 81–110.

Diamond, L. (1999). Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. doi: 10.56021/9780801860140

European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) (2022). Compilation of Venice Commission Opinions and Reports Concerning Vetting of Judges and Prosecutors. Strasbourg.

Feldman, D. L., and Alibašić, H. (2019). The remarkable 2018 “Velvet Revolution”: Armenia's experiment against government corruption. Public Integr. 21, 420–432. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2019.1581042

Freedom House (2019). Armenia: Nations in Transit 2019 Country Report [WWW Document]. Freedom House. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/armenia/nations-transit/2019 (Accessed March 6, 2024).

Freedom House (2024). Armenia: Nations in Transit 2024 Country Report [WWW Document]. Freedom House. URL Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/armenia/nations-transit/2024 (Accessed June 19, 2025).

Fung, A. (2003). Associations and democracy: between theories, hopes, and realities. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 29, 515–539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100134

Gevorgyan, V. (2024). Civil Society and Government Institutions in Armenia: Leaving Behind the Post-Soviet Title. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781032669465

Giugni, M., McAdam, D., and Tilly, C. H. (1999). How Social Movements Matter. University of Minnesota Press.

Habermas, J. (1996). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. New York: The MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/1564.001.0001

Hallock, J., and Ghahramanyan, K. (2024). Guest Post: From Revolution to Reform — Tracing Armenia's Anti-Corruption Landscape. GAB | The Global Anticorruption Blog. Available online at: https://globalanticorruptionblog.com/2024/06/21/guest-post-from-revolution-to-reform-tracing-armenias-anti-corruption-landscape/ (accessed August 6, 2024).

Hellman, J. S., Jones, G., and Kaufmann, D. (2000). Seize the State, Seize the Day: State Capture, Corruption and Influence in Transition. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (September 2000). Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=240555 (Accessed August 20, 2025).

Helsinki Citizens' Assembly - Vanadzor (2020). Քաղհհսարակության ﬕխումբ կազմակերպություններ մշակել են դատական համակարգումարդյունավետ վեթինգ իրականացնելու առաջարկությWւններիփաթեթ |ՀՔԱՎ [WWW Document]. Available online at: https://hcav.am/vetting/ (Accessed June 9, 2024).

Ishkanian, A. (2015). Self-determined citizens? New forms of civic activism and citizenship in Armenia. Eur. Asia Stud. 67, 1203–1227. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2015.1074981

Ishkanian, A. (2016). “Challenging the gospel of neoliberalism? Civil society opposition to mining in Armenia,” in Protest, Social Movements and Global Democracy Since 2011, Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change, eds T. Davies, E. H. Ryan, A. Milcíades Peña, (Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 107–136. doi: 10.1108/S0163-786X20160000039005

Karapetyan, M. (2022). Վեթ5նգ. ո՞ւր հասավ 5րականացումը. CIVILNET, 18 October. Available online at: https://www.civilnet.am/news/679417/ (Accessed June 9, 2025).

Karatnycky, A., and Ackerman, P. (2005). How freedom is won: from civic resistance to durable democracy. Int. J. Not-for-Profit Law 7, 47–59.

Khodunov, A. (2022). “The orange revolution in Ukraine,” in Handbook of revolutions in the 21st century: The new waves of revolutions, and the causes and effects of disruptive political change (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 501–515. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_19

Kriesi, H. (1995). “The political opportunity structure of new social movements: its impact on their mobilization.” in The Politics of Social Protest: Comparative Perspectives on States and Social Movements, ed. J. C. Jenkins and B. Klandermans (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press), 167–198

Krishnamurthy, M. (2015). (White) tyranny and the democratic value of distrust. Monist 98, 391–406. doi: 10.1093/monist/onv020

Levitsky, S., and Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511781353

Luciani, L. (2021). The EU's hegemonic interventions in the south caucasus: constructing “civil' society, depoliticising human rights? Coop. Confl. 56, 101–120. doi: 10.1177/0010836720954478

Marandici, I. (2024). Legislative capture and oligarchic collusion: two pathways of democratic backsliding and recovery in moldova. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 712, 93–108. doi: 10.1177/00027162241307749

Margaryan, T., Hovakimyan, G., and Galstyan, M. (2022). Քաղաքաց5ան հասարայության ներկա վ5ճակը և փոփոխվող դերը հանրայ5ն քաղաքականության գործընթացներում․ հետազոտության զեկույց. Center for Educational Research and Consulting, Yerevan, Armenia.

Mejlumyan, A. (2020a). Armenia: Nations in Transit 2020 Country Report [WWW Document]. Freedom House. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/armenia/nations-transit/2020 (Accessed June 9, 2024).

Mejlumyan, A. (2020b). “Armenia's Pashinyan Compromises on Court Reform.” Eurasianet, September 23. Available online at: https://eurasianet.org/armenias-pashinyan-compromises-on-court-reform (Accessed August 18, 2025).

Meyer, D. S. (2004). Protest and political opportunities. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 30, 125–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110545

Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Armenia (2023). Anti-Corruption Strategy for 2023–2026. Yerevan: Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Armenia. Available online at: https://www.moj.am/en/page/583 (Accessed July 6, 2024).

Muradian, A. (2018). Pashinian's Bloc Declared Winner of Armenian Snap Elections. Azatutyun Radiokayan (Radio Liberty Armenia).

Nikoghosyan, H., and Ter-Matevosyan, V. (2023). From ‘revolution' to war: deciphering Armenia's populist foreign policy-making process. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 23, 207–227. doi: 10.1080/14683857.2022.2111111

Norris, P. (1999). Critical Citizen - Global Support for Democratic Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/0198295685.001.0001

Ordukhanyan, E. (2019). The impact of voter turnout and peculiarities of elections in post-Soviet Armenia. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 8, 1502–1509.

Pashinyan, N. (2019). Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan's Statement on Judiciary System [WWW Document]. The Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia. URL Available online at: https://www.primeminister.am/en/statements-and-messages/item/2019/05/20/Nikol-Pashinyan-Speech/ (Accessed September 6, 2024).

Paturyan, Y. (2020). “Armenian civil society: growing pains, honing skills and possible pitfalls,” in Armenia's Velvet Revolution: Authoritarian Decline and Civil Resistance in a Multipolar World, eds L. Broers and A. Ohanyan (I.B. Tauris), 101–118. doi: 10.5040/9781788317214.0011

Paturyan, Y., and Gevorgyan, V. (2021). Armenian Civil Society: Old Problems, New Energy After Two Decades of Independence, Societies and Political Orders in Transition. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-63226-7

Paturyan, Y., and Melkonyan, S. (2024). Revolution, Covid-19, and war in Armenia: impacts on various forms of trust. Caucasus Surv. 13, 1–28. doi: 10.30965/23761202-bja10036

Paturyan, Y., and Stefes, C. H. (2017). “Doing business in Armenia: the art of manoeuvring a system of corruption,” in State Capture, Political Risks and International Business: Cases from Black Sea Region Countries, eds J. Leitner, H. Meissner (London: Routledge), 43–56.

Policy Forum Armenia (2013). Corruption in Armenia, State of the Nation. Available online at: http://www.pf-armenia.org/sites/default/files/documents/files/PFA_Corruption_Report.pdf (Accessed January 5, 2014).

Pracht, A. (2025). Prosecutors, Appeals Court Clash over Ruling on Samvel Karapetyan's Arrest. CIVILNET, August 13. Available online at: https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/968618/prosecutors-appeals-court-clash-over-ruling-on-samvel-karapetyans-arrest/ (Accessed May 9, 2025)

Protection of Rights Without Borders (2023). Formation of Anti-Corruption Court in the Republic of Armenia: Legislation and Practice: Executive Summary.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuste. doi: 10.1145/358916.361990

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., and Nanetti, R. (1994). Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400820740

Rootes, C. H. (1999). Political opportunity structures-promise, problems and prospects. La Lettre de La Maison Française d'Oxford 10, 71–93.

Shant News (2023). 2Վեթ5նգ2-ը ոչ այլ 5նչ է, քան դատավորներ5 բարեվարքության ստուգում և դատավորներ5 կազմ5 նորացում. Կարեն Անդրեասյան. Shant News.

Shyrokykh, K., and Winzen, T. (2025). International actors and democracy protection: preventing the spread of illiberal legislation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Democratization 32, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2025.2461463

Smith, N. R. (2011). Europeanization through socialization? The EU's interaction with civil society organizations in Armenia. Demokratizatsiya 19:385.

Stefes, C. H. (2006). Understanding Post-Soviet Transitions: Corruption, Collusion and Clientelism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230287464

Stefes, C. H., and Paturyan, Y. (2021). After the revolution: state, civil society, and democratization in armenia and georgia. Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.719478

Tarrow, S. (1994). Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Terzyan, A. (2020). Change or continuity? Exploring post-revolution state - building in Ukraine and Armenia. CES Working Papers 12, 20–41.

Tusalem, R. F. (2007). A boon or a bane? The role of civil society in third-and fourth-wave democracies. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 28, 361–386. doi: 10.1177/0192512107077097

Warren, M. E. (2001). Democracy and Association. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400823925

Zolyan, M. (2020). “Thirty years of protest: how armenia's legacy of political and civic protests prepared the velvet revolution,” in Armenia's Velvet Revolution: Authoritarian Decline and Civil Resistance in a Multipolar World, eds. L. Broers and A. Ohanyan (London: Bloomsbury Publishing), 51–71. doi: 10.5040/9781788317214.0009

Keywords: civil society, anti-corruption, vetting, Armenia, Velvet Revolution

Citation: Paturyan YJ, Simonyan L and Papikyan G (2025) People won, now what? The role of civil society organizations in anti-corruption and judicial reform in post-uprising Armenia (2018–2025). Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1656829. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1656829

Received: 30 June 2025; Accepted: 29 September 2025;

Published: 03 November 2025.

Edited by:

Sarah Anne Rennick, Arab Reform Initiative, FranceReviewed by:

David Aprasidze, Ilia State University, GeorgiaIon Marandici, Université de Fribourg, Switzerland

Copyright © 2025 Paturyan, Simonyan and Papikyan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan, eXBhdHVyeWFuQGF1YS5hbQ==

Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan

Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan Liana Simonyan

Liana Simonyan Gor Papikyan

Gor Papikyan