- 1Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, Malang, Indonesia

- 2Universidade Nacional Timor Lorasa'e, Díli, Timor-Leste

This study investigates the implementation of deliberative democracy at the local level in Indonesia, focusing on how community participation shapes democratic development in a developing-country context. Although the concept of deliberative democracy has been widely discussed in Western scholarship, empirical research in Global South settings remains limited. A qualitative research approach—comprising in-depth interviews, field observations, and document analysis—was employed to explore how public forums, participatory planning, and citizen panels contribute to local policymaking in Malang City. Findings show that these participatory mechanisms enhance inclusiveness, responsiveness, and citizen empowerment. However, their effectiveness is constrained by persistent structural limitations, including elite dominance, low political literacy, and fragmented institutional support. These dynamics have produced a hybrid form of deliberation that bridges informal community networks, formal participatory institutions, and local political practices. The study demonstrates that deliberative democracy in the Global South is best understood as a context-dependent process shaped by cultural norms and institutional arrangements rather than a purely normative ideal. The results highlight the need for comparative analyses that incorporate socio-political diversity across developing democracies. Overall, this research contributes to global debates on deliberative democracy and offers practical insights for enhancing participatory governance in transitional political environments.

1 Introduction

Deliberative democracy established itself as a theoretical concept in the late 20th century, primarily in the 1990s (Sass and Dryzek, 2024), although academic interest intensified only at that time. Jürgen Habermas and Joshua Cohen stress the form of decision-making as collective learning, mutual justification or responsive deliberation among co-equal participants over an aggregation of only preferences (Cohen, 2019; Durrant and Cohen, 2023; Habermas, 1999). However, such a model is less of an expression of social reality in the West than other forms, as Iris Marion Young and Jane Mansbridge have argued (Young, 2000; Mansbridge, 1999); it represents mostly varieties of ages-old ways of thinking about democracy.

In reality, however, deliberation often falls short as a result of social and political inequality — suggesting pitfalls in the theories advanced by Habermas (1962) or Cohen and Rogers (2003) for transitional and inclusive democracies more broadly (Fung, 2006; Parkinson and Mansbridge, 2012). This situation prompts greater interest in alternative pathways as a connective tissue between ideals and empirical realities of postcolonial countries forced to cope with aspects of tradition, patronage, and democratic hopes (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Baiocchi and Ganuza, 2016). This context provides a well of inquiry, as is indicated by research on the hybrid model, which seeks to blend formal institutions with informal practices in order for deliberative principles to be translated into different local contexts (Setiawan, 2021; Avritzer, 2002). Nevertheless, the practice of deliberative democracy (Dryzek, 2010) in developing countries tends to create a significant integrity gap between normative ideals and reality on the ground (Mansbridge et al., 2012). The very idea of the device implies a dialogue between equals, based on freedom and reason; however, what actually occurs is ensnared in age-old power imbalances, patron-client relationships (which I discuss below), “identity politics,” and low political knowledge among the servers themselves (Heller, 2001; Chandhoke, 2009). Formal participatory mechanisms, such as public forums or citizens’ panels, can fall into the symbolic category and be controlled by elites for largely legitimizing predetermined outcomes, like many transitional democracies (Antlöv et al., 2010; Widianingsih and McCourt, 2012), including Malang City in Indonesia.

Hybridity therefore defines not an ideal or a failing, but instead a form of adaptation that reshapes deliberative norms within their local institutions and power relations (Smith, 2009; Parkinson, 2006). Nonetheless, both in theory and empirically, we are only at an early stage of understanding hybridity: there has been a comparative absence of systematic analysis on (a) what hybrids exactly look like (‘institutional-procedural forms vs. cultural practices’), (b) how this affects the quality outcome in terms of discursive output or discourse change processes and policy uptake, as well as on determining parameters related to which ‘contextual variables’ may predict more deliberative outcomes [e.g., state capacity, civil society strength, political incentives, among others] (Baiocchi and Ganuza, 2016). In closing this gap, the study presents an empirical analysis of a process of hybrid deliberation implementation in the Indonesian context at Malang City, benefiting from a relatively permissive legal-reformist political environment and vibrant civil society with active engagement to direct formal participation reforms within its own city-political landscape. This research shows that normative theories of deliberation require local modification and empirical grounding. To shed greater light on the hybrid model in Malang, we paint a picture of reciprocal relational matrices among arenas, norms and actors (see Figure 1).

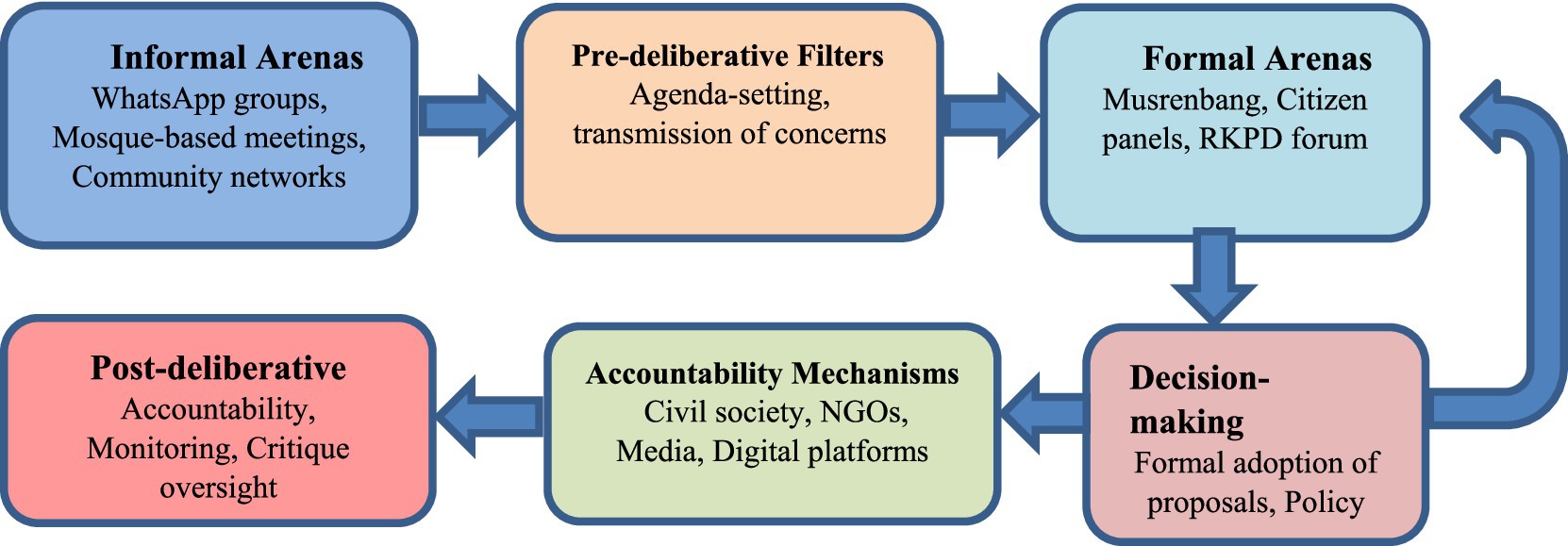

Hybridity in the Deliberative System of Malang: Conceptualizing hybridity Figure 1 illustrates how arenas, norms and actors relate to each other in three intersecting dimensions. Hybridity was defined as how the issues are routed by way of sufferer association between the formal arena (the RKPD and Musrenbang) and the informal. Normatively, we argue that hybridity stems from the coexistence of local cultural logics—those that promote hierarchy, patronage, and deferential authority—with deliberative ideals such as reciprocity and reason-giving. Intermediaries, such as religious leaders, community brokers, and civil society activists, embody this hybridity at the actor level by situating themselves between state institutions and grassroots communities. Combined, these factors allow us to move beyond the descriptive definition of “hybridity” and toward a more systematic architecture that outlines how relational, discursive and institutional mixes shape deliberative conclusions in Malang.

As debates grow about the prospects for deliberative democracy in Indonesia and Southeast Asia more broadly, Malang offers an intriguing (and understudied) case with respect to its evolving intra-state sociopolitical dynamics alongside recent participatory governance innovations by Pratikno (2005) and Mietzner (2015). Malang, with a highly dynamic landed property market and substantial mixture of population pressure in its urban areas, is striving to embed reforms like the Musrenbang (Development Planning Forums), thematic development forums, and citizen panels aimed at improving community participation in public governance practices (Widianingsih and McCourt, 2012; Nurshafira and Alvian, 2019). Religious organizations such as Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah, play a niche role as vibrant civil society entities that advocate for marginalized groups and serve as powerful mediators in political discussions, heavily dictating the governance framework (Buehler, 2016; Regus, 2020). The coincidence of a dynamic civil society network and a relatively responsive municipal government has created room for hybrid kinds of deliberative and participatory procedures to experiment with (Setiawan, 2021). Yet, the experience of Malang highlights challenges common for a transitional democracy, such as elite capture, unequal access to political education, and entrenched patronage that prevent actualization of deliberative principles (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Mietzner, 2015).

We also point out the phenomena of formal and informal arenas with different systemic functions. Rather, informal arenas—WhatsApp groups, mosque-based meetings and community networks—are generally pre-deliberative filters that set agendas while transmitting citizen concerns to formal forums. They also essentially serve as parallel public spheres, in which voices from the margins can more freely hash out their deliberation without sullying themselves with all of bureaucracy’s vulgar grace. On the other hand, formal spaces (e.g., Musrenbang, citizen panels and RKPD forums) are institutional arenas in which decisions can be adopted after a proposal has been evaluated. In addition, civil society groups and digital networks perform a key function of ex post responsibility by shadowing the implementation process for agreed proposals and reproaching publicly with delay or elite capture. We will elaborate on these functions and map the dimensions of transmission, accountability, and decision-making, thereby illustrating more precisely where the system fails to perform effectively due to elite dominance, despite the presence of broad participation (Figure 2).

Governance success, according to this study, is taken to mean the capacity of local institutions, in terms of their policy procedures and outcomes, to be inclusive, responsive, and transparent enough to conform with normative requirements for deliberative democracy (Smith, 2009; Nabatchi et al., 2012). The meaningful participation of diverse social groups in decision-making, making sense of the method through mutual justification mechanisms leading toward an inclusive political culture and not by simple blanket measures (Cornwall, 2008); see also Gaventa (2006). Responsiveness is the degree to which citizen input makes it into final policy decisions, operationalized in public administration studies as government data on the proportion of community proposals approved and corroborated by interview accounts of those officials who acted upon resident suggestions (Fung, 2006; Nabatchi et al., 2012). Transparency was determined by the ability of residents and business owners to examine minutes, reasons for decisions, and budget lines from open-access municipal documents (and verified through interviews), increasing their trust in government when such information is made timely available locally (Fox, 2007; McGee and Gaventa, 2011). In terms of deliberative democracy theory, these standards reflect procedural legitimacy and aim to improve the substance of decision-making by ensuring rational public justification leading to high levels of acceptance (Habermas, 1996; Mansbridge et al., 2012).

2 Mini-publics and deliberative quality

One important model of this kind is the deliberative democracy, which makes decision-making more democratic through intensifying dialogues, inclusivity, and rationalization (Cohen, 1997). Habermas (1996), Cohen (1997), and Cohen (1989), for example, have argued for one such legitimacy based on normative foundations: when decisions are made via reason-giving processes with reciprocal equal moral participation or standing up. The empirical application of mini-publics shows how structured arenas can improve the quality of deliberation by moderating participation to be balanced and rational (Dryzek, 2000; Mansbridge et al. 2012). Others such as Young (2000) and Sanders (1997) have criticized such models for neglecting the nature of discrimination, cultural hierarchies or a general lack of power in which certain sectors face difficulties since their conception. This puzzle is even more acute in transitional democracies, where political literacy is low, deference to figureheads (nearly all male) and authority greater, and resources far scarcer— raising the question of whether these ideals can be achieved at scale outside Western contexts.

2.1 Participatory budgeting and elite capture

The adoption of participatory innovations, such as participatory budgeting and development planning forums (Musrenbang), has been advocated globally to mainstream citizen voices in governance processes. Classics, such as Avritzer (2002) and Baiocchi and Ganuza (2016). In practice, however, evidence is abundant that entrenched elites are often able to co-opt these mechanisms and ensure they simply reproduce the status quo (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; Fung, 2006). In Indonesia, research demonstrates that elite interests and limited bureaucratic capacity, coupled with procedural rigidities, have meant that what is supposed to be a formal vehicle for participatory representation effectively functions as an elaborate charade (Antlöv et al., 2010; Widianingsih and McCourt, 2012). It gives under-represented communities the scope to participate, but their proposals and ideas are more likely to be sidelined, suggesting that institutionalized participation may reinforce existing power instead of opening governance.

2.2 Deliberative systems in post-authoritarian contexts

Current views have shifted toward a more systemic stance whereby deliberation is considered to take place at an interconnected network level between state institutions, civil society and media (Dryzek 2010; Mansbridge et al., 2012) discuss their potential to redistribute power and enhance civic empowerment. In this view, the success of deliberation is conditioned not merely on well-functioning forums but by larger communication of reasons to accountability mechanisms and incorporation of citizen input into policy-making. Systemic analyses enable us to identify new opportunities and challenges in post-authoritarian contexts such as Indonesia. Decentralization Reforms: Although decentralization reforms have institutionalized participatory spaces at the local level, their operations are mediated by socio-cultural norms, patron–client networks, and uneven state capacity (Fitrani et al., 2005; Nurshafira and Alvian, 2019). In cities such as Malang, strong civil society organizations through Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah play a double role: defending the rights of marginalized groups while mediating between citizens and state officials, thereby shaping the local deliberative system.

2.3 Positioning hybridity

Hybridity is primarily outlined in relation to three dimensions identified within these streams of scholarship. Hybridity is imagined as more than a mere descriptive label—it represents an effortful and multidimensional accommodation: institutional hybridization (Musrenbang bureaucracies intersect with religious meetings or WhatsApp consultations, etc.), discursive distancing/rapprochement dynamics between rational argumentation and norms of deference to authority and cultural respect, and actor-network mediations between civil society figures, political brokers, and community organizations that stitch the state-citizen divide. This framing of hybridity emphasizes how deliberative democracy is mediated by local sociopolitical structures in transitional democracies. This application further articulates what the study adds to systemic deliberative theory since it shows how institutional, cultural, and networked hybridity can expand a context-sensitive lens.

In addition, we synthesize the discussion into three main thematic streams (Figure 3). The first is minipublics and deliberative quality (Habermas, 1996; Cohen, 1997), drawing upon a wider set of issues regarding inclusivity, reciprocity and reason-giving. The next subfield, participatory budgeting and elite capture literature, is part of the second research stream (Baiocchi and Ganuza, 2016; Avritzer, 2002; Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019), which highlights how participatory mechanisms are often constrained by entrenched power relations. The third stream addresses deliberative systems in post-authoritarian contexts, drawing on Dryzek (2010), Mansbridge et al. (2012), and scholarship focused on Indonesia (e.g., Antlöv et al., 2010; Widianingsih and McCourt, 2012; Nurshafira and Alvian, 2019) to illustrate how systemic perspectives reveal both opportunities and limitations in transitional democracies. Within this framework, we explicitly position “hybridity” as the analytical bridge across these streams—encompassing institutional blending, discursive adaptation, and actor-network mediation. This approach eliminates conceptual repetition, sharpens theoretical claims, and situates our framework within existing scholarly debates while highlighting its original contribution.

3 Research method

We methodologically grounded our research in the theories of deliberative and participatory democracy. People actively and deliberately participate in the formulation, evolution, and application of political policies, according to these theories. Participatory models and representational institutions do not allow citizens to influence politics (Mendonça et al., 2024; Nurmi, 2023; Plans et al., 2024). Nonetheless, everyone has the right to participate in significant decision-making since we are all reasonable human beings. The public can control political concerns in this type of democracy (Curato and Calamba, 2024). Theorists of the deliberative democracy model contend that democracy allows people to discuss political matters and decisions that are binding them (Engelmann et al., 2024; Sass and Dryzek, 2024). This study applied both general and specific scientific procedures. Among the particular techniques were focus groups, case studies, interview materials, secondary study of sociological data, and document analysis.

Moreover, purposive sampling was implemented with 22 participants (5 government officials, 6 community leaders, 6 civil society activists, and 5 citizen panel members), and their demographics (age, gender, and role) were included. The data collection process included specifics like the duration of interviews (60–90 min), the contexts of observations, and the selection criteria for documents. Moreover, data analysis was done through thematic coding, conducted manually, integrating deductive and inductive categories, and triangulation across data sources. Meanwhile, ethical protocols came from verbal informed consent and confidentiality measures sanctioned by the University of Muhammadiyah Malang.

Data were collected through in-depth interviews (Pandey and Pandey, 2015), document analysis, and participant observation. For the current study, we used empirical data that includes an expense statement from the Malang city government for 2008–2012 regarding a deliberative democracy program. We looked through the findings of discussion papers to recognize key issues and trends concerning the approach and its results, which demanded a systematic, categorizing inspection, citing based on 50 min. In addition, interviews with the Malang City government officials and key stakeholders (community leaders, civil society actors) were also conducted, as well as deliberation participants. Paired interviews with people implementing deliberative democracy were designed to capture a view of the practice from multiple angles, incorporating both wisdom and work-in-progress. On the other hand, collecting data through participatory observation by attending different deliberative democracy-related events in Malang City (public talks and governmental-friendly forums after work) was conducted as well. The category to which it belongs is the dynamics of deliberative democracy that we also call participant interactions, facilitation techniques and decision-making systems. In order to collect data on the indicators, we compiled some operationalization of each indicator in Table 1.

4 Hybrid deliberative democracy in practice

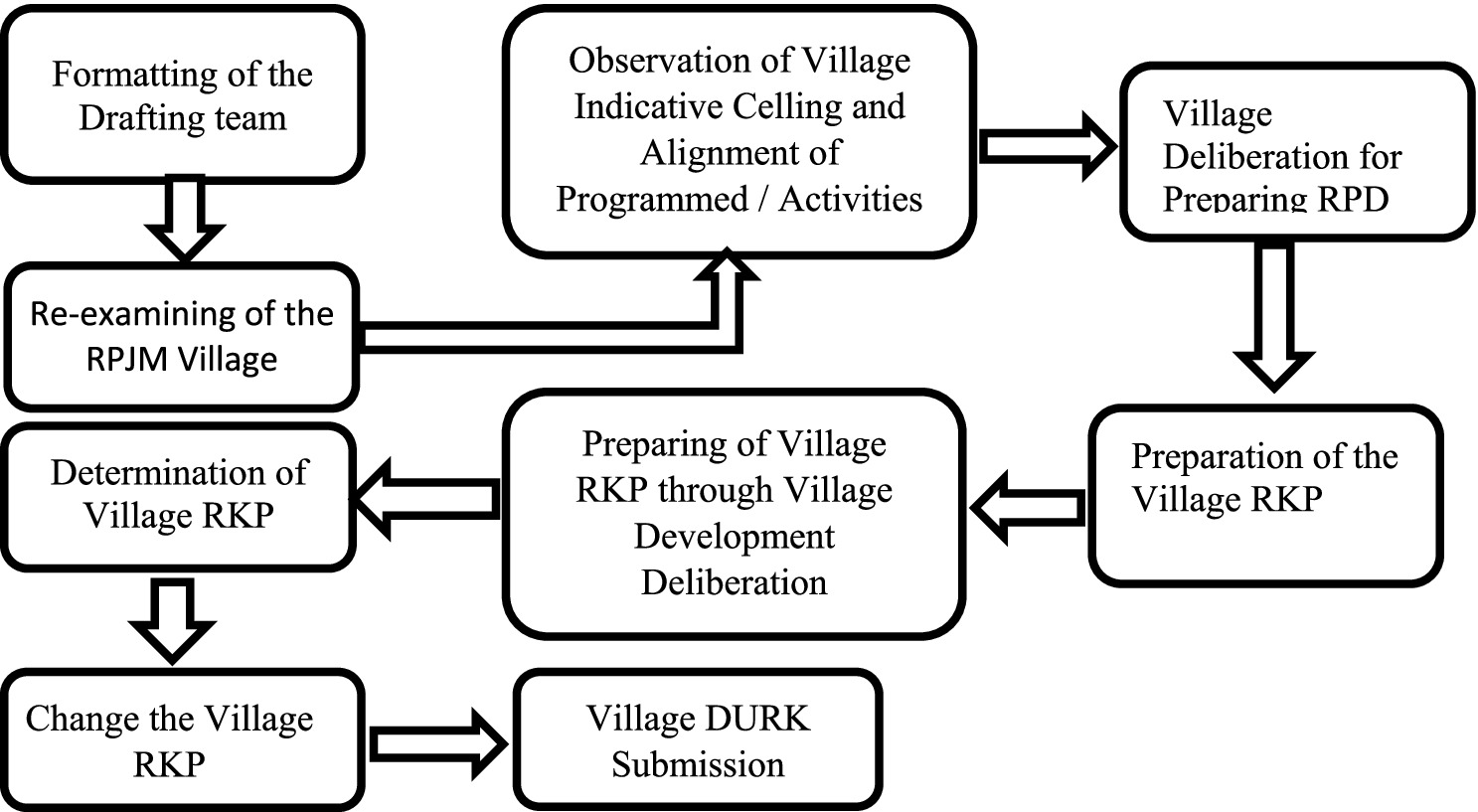

The number of projects based on citizen input demonstrates the success of Musrenbang in Malang City. Traditional budgeting processes may have overlooked specific community needs that these projects often address. However, the long-term sustainability of Musrenbang depends on continued financial support and political commitment from local governments. Participatory budgeting was implemented through the Development Meeting (Musrenbang, Musyawarah Pembangunan) mechanism in stages, starting at the lowest level of government organization in Malang City, namely the village/sub-district (see Figure 4). The aim was to increase community participation at all levels, including marginalized groups. We carried out the implementation of Musrenbang in stages, beginning at the village/sub-district level and progressing to the sub-district and district/city levels. The sub-district Musrenbang is an annual meeting of sub-district stakeholders to agree on activity plans for the following year.

One of the Musrenbang principles was establishing community participation in the development process to ensure that it runs dialogically and participatively and meets the needs and desires of the community. Sub-district governments emphasize that the implementation of development planning must come from the community by prioritizing democracy and participation without taking sides. If development increases people’s welfare, it is considered successful. Therefore, the development planning process, or Musrenbang, is a bargaining process between the government’s desires and the community’s needs.

The public forum is a key part of Malang’s efforts to promote deliberative democracy. It gives residents a structured place to voice their concerns, suggest policy changes, and talk to local government officials. Historically held in less-integrated neighborhoods, these forums have gradually gained more attendance as awareness of their purpose has grown. Expert addresses and plenary sessions, both of which are believed to be successful in promoting an open dialogue, comprise the forum formats. However, promoting participation in these forums poses a challenge due to the under-representation of certain groups, such as women and low-income individuals. This optimizes the targeted outreach and support strategies required to drive participation.

This helps the municipal government to reach out and engage the public also through local media, especially radio channels (Lauk and Berglez, 2024). The broadcast format allows for the real-time discussion of relevant events and issues such as infrastructure development, disaster response, and municipal services. During this session, the government representative needed to explain the problem, the settlement plan related to it, and the current developments. Community targets worked well, and activity was high with responses to every ask or feedback. Congestion: A forum for developing community feedback through radio station debates, traffic engineering, and alternate road branches in the government.

However, despite these promising outcomes, the impact of public forums on actual policymaking is far-reaching. Changes in political will and shifts in public pressure can often decide if recommendations move beyond the page. Drawing from observations, the result is a process that, not surprisingly given the aforementioned elite capture of these spaces, has an elitist tenor as well, with deliberations being attended by influential community leaders who are known to municipal staff and minor actors with no negotiated outcomes. High-ranking officials, such as the Secretary of the Region (Sekretaris Daerah) and the Head of the Local Planning Agency (Bappeda), normally chair those sessions. The programme opens with words of welcome and goes on to formal presentations about the programs, and “open” discussions consist largely in seeking public support for decisions already taken. While many offer reasonable, evidence-supported arguments in good faith, officials often respond with a variant of ‘we have already looked at that’, and the debate ends forever. A young participatory budgeting participant added, “We have already talked about the necessity of repairing drainage systems to avoid flooding cities and were replied with, ‘You cry for allocated money.’ This kind of exchange is an indicator that most official responses only go through the formalities, and there are few real chances for rational deliberation.

Despite these positive outcomes, the impact of public forums on actual policymaking varies considerably. The implementation of recommendations often depends on shifts in political will and fluctuations in public pressure. Observations indicate that deliberations often adopt an elitist character, with attendance dominated by well-known community figures who maintain established relationships with municipal leaders. High-ranking officials – such as the Regional Secretary (Sekretaris Daerah) and the Head of the Regional Planning Agency (Bappeda)—typically preside over these sessions. Proceedings begin with formal speeches, followed by structured program presentations, after which “open” discussions largely serve to secure the community’s endorsement of pre-formulated plans. Although many participants present logical and evidence-based arguments, officials frequently counter these with claims that proposals have already been considered, effectively closing off reciprocal debate. As one youth participant noted, “We’ve already explained the importance of improving drainage to prevent flooding, but the response was that this funding has already been allocated.” Such exchanges suggest that official responses often serve procedural formalities rather than genuine opportunities for reasoned deliberation.

While overall participation levels in development planning remain high, active engagement—particularly in shaping agenda priorities—is constrained by limited public understanding of technical and procedural issues. To close this gap, the city government has set up community facilitation teams to help people in the area explain their ideas. Recommendations have also been made to integrate digital platforms into participatory planning processes, thereby strengthening democratic transparency and accountability. Lucas et al. (2019) argue that the introduction of an e-development forum system transforms community participation from a passive, recipient-orientated role into an active, co-productive one. Similarly, Norton and Elson (2002) emphasize the value of information systems that allow timely feedback, enabling policymakers to respond more effectively to complex local challenges.

Planners from the Malang City Regional Development Planning Agency (Bappeda, Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Daerah) held a Malang City Regional Government Work Plan Development Forum (RKPD, Rencana Kerja Pemerintah Daerah) to demonstrate their commitment to achieving sustainable development in Malang City. This Malang City RKPD development forum involves all stakeholders related to development in Malang City to obtain input suggestions to improve the RKPD design. The head of Bappeda mentioned that before the main RKPD development forum, there were several earlier meetings, including village and sub-district forums, public consultations, and discussions with regional agencies, leading up to this final forum. The Malang City Development Forum received a total of 6,046 proposals in 2024, and it accommodated 3,173 of them, representing approximately 52.48%.

Despite increased community involvement in public budgeting, there are issues with the budget’s effectiveness and representation of all societal segments. Field data shows that this Musrenbang was very effective in designing community-driven projects such as improving public infrastructure and social services. However, the challenge faced was the inability to accommodate all projects due to the limited budget. The solution involved implementing a priority mechanism based on the urgency of projects and the number of users affected; for instance, drainage projects are frequently utilized to address flooding during the rainy season (Moeis et al., 2020).

This pattern in Malang’s public forums exemplifies Habermas (1996) assertion that reciprocity and reason-giving are fundamental to legitimate deliberation, although these principles are frequently hindered by structural and procedural constraints. While citizens in some instances articulated well-reasoned proposals grounded in local needs, the bureaucratic framing of priorities and elite dominance restricted the dialogical exchange that Cohen (1997) identifies as essential for mutual justification among free and equal participants. The limited opportunities for citizens to challenge official positions, coupled with predetermined policy agendas, suggest that reciprocity is more procedural than substantive. In effect, Malang’s deliberative spaces reveal a partial realization of the deliberative ideal: formal mechanisms exist to facilitate dialogue, but entrenched power asymmetries, selective responsiveness, and budgetary constraints undermine the quality of reasoning and the equality of participation envisioned in normative theory.

4.1 Inclusivity: expanding and restricting access to deliberation

Participatory forums and Musrenbang (Development Planning Forums) in Malang City are open to various community groups, such as people with disabilities, the elderly, youth, and women. Despite this inclusivity in principle, the empirical data presented above (Table 2) illustrates that acceptance rates of proposals vary significantly across groups, demonstrating both the promise and limits to diversity in practice. For example, the children’s group submitted 33 proposals in total, of which 22 (66.7%) were accepted and one-third rejected -- demonstrating soft institutional responsiveness but systemic or structural obstacles to child rights mainstreaming. In fact, proposals from the elderly group were equal parts accepted and rejected by city officials (47 approvals versus 47 rejections, or about 50 percent success), suggesting a somewhat selective acquiescence of their needs in terms of development planning. On the contrary, it was women’s groups that showed high approval rates: of 90 proposals made by these agents, 61 (67.8%) were approved and a much lower percentage—29 (32.2%)—rejected; this is evidence of specific recognition of municipal planning processes on gender matters as discussed in section eight above (predictability).

By contrast, the youth group had a much more comprehensive set of experiences: 260 proposals were sent in and only 17 accepted; another 243 were conditionally approved out of sheer exhaustion by decision-makers (the status of most other intended curricular changes is unknown), causing both transparency and procedural accountability concerns. These disparities indicate that while the thematic development forum may have created formal access points for participation from downstream and upscale groups, it does not ensure equitable substantive inclusivity across all demographics. Low youth and disability research responsiveness particularly exposes poor technical support for community proposal writing competencies, as well as inherent biases in evaluation screening mechanisms disadvantaging certain demographic groups.

Although significantly fewer women and youth participate in the discussion (50.9% vs. 25%), the acceptance rate of women’s proposals is much higher (67.8%) compared to those made by youngsters, which only have a 6.5% chance at being taken onboard for future funding opportunities. One woman leader said, “Our proposals have been better received due to our good relations with government officials who could help explain them. The government officials were our friends for interacting with them in several Malang City Government activities. However, it appears that more youths attend village-level musrenbang/forums than women. The data also imply that being officially affiliated with SE does not always signpost how well one is personally included, which accounts for the difference between attendance and having a true presence. If you are a person with disabilities or have flexibility of timings and need to physically attend despite open invitations, these conditions should be removed as well.

4.2 Quality of reasoning and power dynamics

While the forums in Malang may be thought of as deliberative, they suffer from inequalities that thwart reciprocity and reason-giving. These dynamics can be analytically separated into communicative and structural inequalities. Generally, the uneven levels of political literacy and information asymmetry heavily influence communicative inequalities. Political literacy has been measured at the national level in Indonesia and found alarmingly low (Mellinda Fatimah et al., 2020), with implications for participation. Citizens who are uninformed and unable to find factual information passively stand on the sidelines while a few vocal people drive debate (Stoddard and Chen, 2018). As noted above, deliberative democracy implies that citizens must support their claims through rational premises (Geyikçi, 2004), but the absence of effective information flows in Malang poses an obstacle to such exchanges. This further disinclines citizens to engage them; in addition, ever-repeating corruption scandals (Lightbody, 2024; Schmitt-Beck and Schnaudt, 2023) contribute to widespread disenchantment. These communicative failures attenuate reciprocity, since the relative distributed nature of dispute and response to official arguments varies across social divisions.

Among the main obstacles to a democratic Malang is that there are some people who have more information and political education than others. The Indonesian Central Statistics Ministry (BPS) conducted a survey in 2020 and found that 2,000 respondents still have low political literacy. This informational asymmetry underscores the unequal opportunities for participation in political deliberation, a crucial aspect of democratic practice. The underlying principle of deliberative democracies is to get the public convinced in decision-making through open debate and reasoned communication (Geyikçi, 2004). The lack of effective communication pathways undermines these ideals in practice, despite their existence in theory.

Effective channels of action are nearly non-existent because few people understand how political mechanisms work and almost no one has access to reliable information. Extant empirical work reveals that in a setting with low stakes of political competence, public discourse disproportionately influences a select few contributing voices, while silencing many others (Stoddard and Chen, 2018). Media coverage of corrupt state officials over the years has reinforced a commonly held perception, further influencing this reluctance to come forward. Research has indicated that corruption in Indonesia has been widespread; for example, after autonomy is implemented, it takes place not only at the national level but also at the regional level (Lightbody, 2024; Schmitt-Beck and Schnaudt, 2023).

The next point is that structural inequality arises from entwined power hierarchies, which manifest in client-patronage systems, religious governance, and elite control. The sociopolitical field in Malang is heavily influenced by its dominant organization (Nahdatul Ulama/NU), which both attracts a wide range of political supporters and promotes majority domination at the expense of minorities’ voices (Regus, 2020; Schramme, 2021). The wider structure of clientelism and patronage politics in Indonesia relates to this phenomenon (Alfada, 2019; Mietzner, 2015). This trend is seen especially in Musrenbang, the formal planning forum where religious and long-standing leaders often back local officials. However, the term ‘an elected official who knows everything about every topic’ was not always clearly defined outside of parliament. An activist responded by stating that elites decide on important matters before they reach a public forum. However, this elliptical pre-selection, based on the Habermasian ideal of equal reason-giving, reveals an elite’s procedural control over deliberation. This problem is magnified by gender, as structural inequalities cut across the genders, and women who do make submissions are still marginalized in leadership positions; hence, they have little control over ordering business on the agenda or arguing for female-friendly rules of procedure. Consequently, despite some visible contributions from women, their impact on the final policy outcomes may be minimal.

Examples such as Malang serve to show that both the communicative and structural inequalities in political debates lead to a distortion of deliberation. Whereas the ideal normative vision promotes a process of inclusive and reciprocal deliberations, grounded in reason, that form the crux of democratic values held for reasoned exchange to prevail over conflictual interaction, its loose coupling with understanding participation is shown through unequal access to information, which reinforces established patronage networks while maintaining gendered exclusions. These systems systematically interfere with the quality of discursive deliberation.

From a political-culture perspective, Indonesian society has shown its persistency in doing identity politics since it was often excluding minority groups (Regus, 2020; Schramme, 2021). Long-standing patron-client relations, which encourage citizens to entrust political decisions to a charismatic leader, support this phenomenon. The dominance of a traditional Islamic movement, namely Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), marks the socio-political landscape in Malang. This leads to public decisions that cater to the interests of the majority group, primarily because political support bases and potential patronage possibilities could tempt local leaders into committing corrupt practices (Alfada, 2019; Donovan and Karp, 2017; Mietzner, 2015). According to official data, Indonesia’s Corruption Behaviour Index (IPAK) in 2023 was 3.92 on a scale of 0–5 (where the higher the value, the greater the corruption), showing no improvement from the 2022 score of 3.92.

These imbalances persist through formal channels such as Musrenbang. Instead, it is homegrown community leaders and religious figures with access to local government officials that often dominate these forums for dialogue. Formal meetings typically establish these relationships. About consulting Civil society activists observe that elites often decide on key projects in informal meetings, avoiding the public arena. The dynamic frustrates Habermasian equality reason, and in this vein repeats an institutional pattern of structural power asymmetry seen internationally among participatory politics, one which is particularly pronounced throughout Southeast Asia.

In addition to this, the imprint of gender inequality stays in Malang’s deliberative space. While women provide suggestions and support community projects, they frequently lack recognition as leaders or overseers of procedural rules that impact final decision-making. It is this limited procedural muscle that limits their control over whether they can obtain a hearing and ultimately be listened to, further undermining the inclusivity of representation in that deliberative process.

4.3 Hybrid practices: formal-informal interaction

The citizen panel findings demonstrated that many agreed-upon decisions had been accepted officially, but there were delays, and the implementation may be overruled by political or bureaucratic power (Barnhill and Bonotti, 2023; Nurjaman, 2020). In the city of Malang, citizen panels have been employed by the government to help in implementing certain projects or policies that were stalled due to objections from rent seekers. The panels were relatively active, largely thanks to the initiative of community group Malang’s Democracy Concern (MPD). The membership of MPD is composed of a diverse cross-section of individuals who care deeply about political and governmental issues, including academics, politicians, public officials (active or retired), artists, and others in the community. This diversity of backgrounds and experiences enables the group to make demands and conduct scrutiny. Significantly, it has always been MPD’s intention to be an organization inclusive of the broad range of communities in Malang— religious and ethnic backgrounds, different socio-economic statuses, etc. Therefore, various community leaders, skilled in convening neutral and impartial discussion panels, traditionally moderate all forums when they hold them.

These mechanisms include both the formal (Musrenbang, thematic development forums) and informal (environmental networks or WhatsApp groups). Serving within a communal entity, such as a religious organization, these informal networks have been remarkably successful in articulating and elevating the interests of minority communities in public policy. But the same networks can also unintentionally strengthen patterns of patronage between citizens and officials. Politicians, community leaders, and sponsors are members of these groups, where they discuss a variety of issues beyond just Muslim matters; they are also actively involved in the government sector by sharing their views on policies. For example, the WhatsApp groups of MPD’s correspondents can also result in face-to-face meetings between group members and government representatives. A member of the MPD group stated that in the past, they had discussed many suggestions within their WhatsApp group, which were later presented to the government. A current Region 1 MPD participant reported that these virtual forums had already informally debated several proposals submitted to the government.

The Citizen Panel worked via a few procedures: (1) discussion with the executive and legislative sectors, (2) formal appeal by citizens (Grecu and Chiriac, 2021; Nurmi, 2023; Verhasselt, 2024). In this space, the participants can present their proposals for new development projects, as well as how to improve ongoing programs and public service provision. Outcomes are usually in the form of commendations, advice on strategies, and recommendations for modifications to programs, as well as other authorities’ actions. While some recommendations have been implemented, others have been outstanding for years because of political interest or bureaucratic inertia (Nurshafira and Alvian, 2019). This case points to the wider problem faced in mainstreaming citizen input through formal decision-making processes that are hampered by institutional resistance or lack of political will.

Community participation in this dialogue is high; the residents readily identify where they have shared needs, and these translate into development program proposals (Houser et al., 2012; Savaget et al., 2019). Questions about the absence of proper public facilities, long-standing traffic jams, and periodic flooding were top of mind. The reaction of the government to proposals, on a general level, is positive, even though it is incremental in implementation, as it focusses first on responding immediately—most emergency needs are met—and tailors plans for individual neighborhoods depending upon their socio-spatial dynamics.

A large part of the deliberative process is also attended by local religious leaders, heads of “tahlil” (Islamic religious activity) congregations (Fossati, 2019; Harahap, 2019), political party officials, and members of youth organisations. Political party representativeness is a powerful interest because these parties are closest to the decision-makers, which often results in proposals being accepted immediately. The structure of the political party serves to aggregate this collective aspiration through the Lembaga Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Keluarahan (LPMK), which exists in all sub-district governments. The collaborative ecosystem, which includes sub-district governments, community heads, traditional leaders and various other institutions such as political party officials, religious figures or even young people of different networks, showcases that both formal (local government) and informal (tradition-based authority in the form of indigenous spiritual leaders) institutions are capable of mobilizing on the ground level across various strata. What matters in these exchanges is the desire to work together toward common goals and the mutual determination to solve local problems.

This interaction between formal and informal mechanisms has created a hybrid deliberative institutional structure in Malang City, which is likely to develop cumulatively as an indigenous form of democratization. However, this hybridity raises significant normative questions regarding transparency and accountability, specifically whether these off-the-record deliberations genuinely enhance the democratic legitimacy of decisions or simply reproduce elite-driven patronage networks that disguise themselves as participation. The hybrid structure design is viewed as a result of this random meeting, which aims to facilitate multicultural adaptation in Malang City. But it does question transparency and whether such informal deliberation reinforces democratic legitimacy or not.

4.4 Connecting empirical patterns with the conceptual framework

The empirical result shows that deliberative democratic ideas have not been well implemented in Malang. Inclusivity is contingent; reciprocity is constrained by institutional lassitude; reason is often fallacious, and discourse quality is compromised by prevailing elite hegemony. While there is considerable variation in participatory practices across governance levels, also the hybrid institutional framework operating within subnational governments (i.e., strategic arenas as well as reactive mechanisms)—which combines formalized processes (e.g., Musrenbang) and informal network-prone situations (e.g., community-based groups, citizen panels)—represents deeply structural inequalities. In practice, Malang’s deliberative system operates as a contested arena where procedural transparency is combined with entrenched conditions of power asymmetry. If we are to move forward with democratic consolidation, addressing these designs and ameliorating socio-political disparities is essential.

The decentralization reforms after the fall of Suharto made new institutional spaces possible for public engagement, which was not present during the authoritarian era in Indonesia when decision-making was centralized and led by the government at the national level. Local governance in Malang wants to be more transparent, accountable, responsive and inclusive than what is included in the deliberative democracy framework today. Dialogue between citizens and local officials is facilitated by public forums, Musrenbangs (village-level development deliberation), and citizen panels that have started to form across regions, providing an avenue for more equitable outcome-centered decision-making. These mechanisms coincide with fundamental signs of good governance, such as transparency and accountability, neutrality in approach to problems caused by non-profit organizations, and active cooperation between government institutions and community figures. Ultimately, though, challenges remain in terms of administrative capacity — political turnover and a lack lustre focus on public interest have hamstrung the efficacy and longevity of participatory governance initiatives.

This is largely done within the broader context of Indonesia, which has been trying to embed democratic practices since 1998, and thus, avoiding any signs of democratization requires bolstering deliberative institutions. In other words, deliberative democracy is the ideal that citizens be afforded an open seat at a figurative table of government — or empowered by institutional procedures to partake in dialogues and debates followed by votes. In practice, however, these ideals are circumscribed by structural, cultural and political obstacles that appear even more salient in transitional democracies (Table 3).

Participation patterns (Table 2): pointing to further challenges Even at the village level, people do not have access to information, which is why most villagers will remain uninformed about deliberative events. Higher attendance rates (73%) [removed] Common reasons for less active participation: Most Commonly Cited Obstacle Speaking slot filled by someone who is closely connected to village officials Gainful employment Long travel distance or cost — In most cases, the speaking role is given to individuals closely tied with local power interests, leaving very little room and opportunity for ordinary citizens. This leads to a situation in which the decision-making process is a top-down affirmation of established agendas rather than true deliberation.

Participation mechanisms are more inclusive at the sub-district level. At the begining, making use of both so-called RT/RW (neighborhood) level honesty boxes in problem identification and data collection; hence, an effective direct involvement from various parts among community representatives. Conversations at this level also forge a stronger ground for your physical infrastructure, economic development, socio-cultural issues and governance discussions. Despite that, involvement of common people in budget-related deliberations is scant, suggesting some areas still sway to elite decision-making.

In the city contexts, and generally related to the dissemination of discussion outcomes in deliberative forums, they are more transparent; participation reaches well beyond those officially invited. That said, inclusivity is still far from being achieved, and crucially the women’s movement is rarely seen around those rectangular tables. Also, despite a desire to find bottom-up perspectives in group discussions on strategic priorities and shape development goals/policies at the city level, much of it has been largely top–down.

Sub-district forums, by comparison, represent an intermediate between participatory dialogue and decision-making. Honesty increases in city-level forums but remains top-down or vertical, without much democratic policy development for the village level, as it is very bureaucratic and gets undue influence from local elites. Thus, strengthening participatory governance in Malang would benefit from a more programmatic intervention: improving village-level transparency and accessibility; ensuring marginalized group participation; developing institutional mechanisms at the city level for such anticipation; and resourcing budget decision power to citizens across all levels of governing.

5 Discussion

In Malang City the evidence of this is incomplete fulfillment, especially of normative principles of deliberation democracy, which reached varying degrees of success in terms of inclusion, reciprocity and reason-giving. The principle of inclusivity is shown in the formal participation of women, youth groups, older people and persons with disabilities in Musrenbang forums, although it has not been consistent. In 2023, for example, government records show that 62% of the sworn job apps by women were successful compared to only a mere 27% across youth submitting them; however, temp staff described an assortment of institutional roadblocks. A member of youth said, “Because we do not have as many political connections as the older community leaders… We see our suggestions being looked at as more unrealistic.” This case demonstrates broader trends identified in previous studies from Southeast Asia (e.g., Bebbington et al., 2021), where institutional inclusion does not immediately lead to outcomes.

Reciprocity, defined as the willingness to engage with and address others’ arguments, was highest in smaller forums related to concentrated moderators who were active. Conversely, the bigger city-level discussions often degraded into elite-dominated monologs. One local leader of an NGO said, “If the district head speaks in a room, everyone freezes or at least tries to go along with him, and no one will argue. These dynamics are consistent with the findings from Baiocchi and Ganuza’s (2016) work on elite capture in participatory budgeting processes, which suggests that while formal access is necessary, it must be paired with institutional safeguards in order to allow for real dialogic engagement.

The case of Malang demonstrates that hybrid deliberative democracy operates in a vertical interaction between sociopolitical hierarchies, formal institutions and entrenched informal networks. These findings draw on Habermas’s theories about the public sphere and focus on reasoned justification between free and equal citizens by Cohen: more generally, a normative objective that can only be met when moved out of its broader context of sociocultural norms, cultural bonds, patron-client relationships, and asymmetric power relations with elites in public spheres. Therefore, the Malang case gives us local powerful evidence of how power asymmetries operate in the discursive/procedural dimensions even if various Western models of deliberation are based on arguments such as ‘civil servants must be autonomous’ and ‘there should exist an impartial institutional mediator’.

There is an echo here from the Porto Alegre example in Brazil (Avritzer, 2002) and when village assemblies are refined for participatory budgeting in Kerala, India — each where a prominent role was played by local elites such as environmental activists, political brokers on one occasion, or entrenched religious leaders. The hybrid deliberative democracy model in Malang, combining civil society advocacy, WhatsApp group consultations and meetings at mosques with musrenbang (local development planning forums), shares similarities to the Tampon Council of Thailand or Barangay Councils of the Philippines, where formality restrictions are confused with sociocultural practices. In contrast to situations in Latin America where hybridization seems only too vertical down to the grassroots, this informal sphere instead serves as a springboard for hierarchical power consolidation — at the expense of what might actually constitute deliberative democracy.

This empirically confirms the counterintuitive view that people nowhere are on board with the assumption of the universality of institutional control and guarantee or mutualism. The case illustrates the necessity of deliberative theory that takes into account how different historical contexts, local political economies and religious authority structures all enable but also condition policy outcomes (i.e., substantive representation) as well as discursive quality (references for both are necessarily left to be decided or determined by possible future research). Effectiveness should not be assessed exclusively on more abstract aims but rather by considering how the deliberative process is mindful of its place in a socially dense environment. That consensus-building process additionally entails the form of stealth patronage, tradeoffs and horsetrading necessary in any informal system. The Malang case thus offers a useful counterpoint to this prevalent Western version, demonstrating that in neoliberal transitional societies, furthering democracy necessitates confronting the politics and cultural logics of public deliberation rather than moving beyond or through it.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Institute of Muhammadiyah University of Malang. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the activities carried out in this research involve researchers for each activity, participant research. In this study, all participants were informed of the research purpose, the voluntary nature of their participation, and their right to anonymity. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical norms governing social science research in Indonesia.

Author contributions

AN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JP: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was made possible by funding from the university research fund for the project “Deliberative Democracy Model in Malang City: Citizen Participation and Public Decision-Making Process.” The project was funded under grant agreement no. E.6.1/95.09/RPK-UMM/IV/2024.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Artificial intelligence technology was utilized to enhance grammatical accuracy and improve sentence clarity in language refinement.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1658901/full#supplementary-material

References

Alfada, A. (2019). Does fiscal decentralization encourage corruption in local governments? Evidence from Indonesia. J. Risk Financial Manag. 12:118. doi: 10.3390/jrfm12030118

Antlöv, H., Brinkerhoff, D. W., and Rapp, E. (2010). Civil society capacity building for democratic reform: experience and lessons from Indonesia. Voluntas 21, 417–439. doi: 10.1007/s11266-010-9140-x

Aspinall, E., and Berenschot, W. (2019). Democracy for Sale: Elections, clientelism and the state in Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Avritzer, L. (2002). Democracy and the public space in Latin America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Baiocchi, G., and Ganuza, E. (2016). Participatory budgeting as if emancipation mattered. Polit. Soc. 44, 29–50. doi: 10.1177/0032329215620659

Barnhill, A., and Bonotti, M. (2023). Healthy eating policy and public reason in a complex world: normative and empirical issues. Food Ethics 8, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s41055-023-00131-9

Bebbington, A., McCourt, W., and Williams, G. (2021). Governing Extractive Industries: Politics, Histories, Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buehler, M. (2016). The politics of shari'a law: Islamist activists and the state in democratizing Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chandhoke, N. (2009). Participation, representation and democracy in contemporary India. Democratization 16, 20–43. doi: 10.1080/13510340802575707

Cohen, J. (1997). “Deliberative and democratic legitimacy” in Deliberative democracy: Essays on reason and politics. eds. J. Bohman and W. Rehg (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press), 67.

Cohen, J. (1989). “Deliberation and democratic legitimacy.” In The Good Polity: Normative Analysis of the State, Ed. Alan Hamlin and Philip Pettit, pp. 17–34. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Cohen, A. (2019). Judicial politics and sentencing decisions. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 11, 160–191. doi: 10.1257/pol.20170329

Cohen, J., and Rogers, J. (2003). Power and Reason. In Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance, Eds. A. Fung and E. O. Wright. London: Verso, pp. 237–255.

Cornwall, A. (2008). Unpacking ‘participation’: models, meanings and practices. Community Dev. J. 43, 269–283. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsn010

Curato, N., and Calamba, S. (2024). Deliberative forums in fragile contexts: challenges from the field. Politics. 1–14. doi: 10.1177/02633957241259090

Donovan, T., and Karp, J. (2017). Electoral rules, corruption, inequality and evaluations of democracy. Eur J Polit Res 56, 469–486. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12188

Dryzek, J. S. (2000). Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. Oxford University Press.

Dryzek, J. S. (2010). Foundations and Frontiers of Deliberative Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Durrant, D., and Cohen, T. (2023). Mini-publics as an innovation in spatial governance. Environ. Plann. C. Polit. Space 41, 1183–1199. doi: 10.1177/23996544231176392

Engelmann, I., Marzinkowski, H., and Langmann, K. (2024). Salient deliberative norm types in comment sections on news sites. New Media Soc. 26, 921–940. doi: 10.1177/14614448211068104

Fitrani, F., Hofman, B., and Kaiser, K. (2005). Unity in diversity? The creation of new local governments in a decentralizing Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 41, 57–79. doi: 10.1080/00074910500072690

Fossati, D. (2019). The resurgence of ideology in Indonesia: political Islam, Aliran and political behaviour. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 38, 119–148. doi: 10.1177/1868103419868400

Fox, J. (2007). The uncertain relationship between transparency and accountability. Dev. Pract. 17, 663–671. doi: 10.1080/09614520701469955

Fung, A. (2006). Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Adm. Rev. 66, 66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

Gaventa, J. (2006). “Triumph, deficit or contestation? Deepening the ‘deepening democracy’ debate.” IDS working paper 264. Institute of Development Studies.

Geyikçi, Ş. Y. (2004). The impact of parties and party systems on democratic consolidation: The Case of Turkey. Colchester, UK: University of Essex, 1–21.

Grecu, S.-P., and Chiriac, H. C. (2021). Challenges for deliberative democracy in the digital era. Technium Soc. Sc. J. 26, 1–11. doi: 10.47577/tssj.v26i1.5386

Habermas, J. (1996). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Translate by Rehg, W. Cambridge: Polity.

Habermas, J. (1962). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Translate by Rehg, W. Cambridge: Polity1989).

Habermas, J. (1999). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harahap, H. I. (2019). Islamic political parties in Southeast Asia: the origin and political problems. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 7, 481–489. doi: 10.18510/hssr.2019.7555

Heller, P. (2001). Moving the state: the politics of democratic decentralization in Kerala, South Africa, and Porto Alegre. Polit. Soc. 29, 131–163. doi: 10.1177/0032329201029001006

Houser, D., Ludwig, S., and Stratmann, T. (2012). Does deceptive advertising reduce political participation? Theory and evidence. Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2087096

Lauk, E., and Berglez, P. (2024). “Hybrid Media Logics in Democratic Communication.” Journalism Studies, 25, 245–262.

Lightbody, R. (2024). Evaluating the role of public hearings within deliberative democracy: operationalizing the democratic standards as a framework. J. Deliber. Democ. 20, 1–14. doi: 10.16997/jdd.1454

Lucas, N., Biotelemetry, A., Lucas, N. N., Dewar, H., Nishizaki, O. S., Wilson, C., et al. (2019). Movements of electronically tagged shortfin mako sharks (Isurus oxyrinchus) in the eastern North Pacific Ocean. Anim. Biotelemetry, 7:1–26. doi: 10.1186/s40317-019-0174-6

Mansbridge, J. (1999). “Every day talk in the deliberative system” in Deliberative politics: Essays on democracy and disagreement. ed. S. Macedo (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 211–239.

Mansbridge, J., Bohman, J., Chambers, S., Estlund, D., Føllesdal, A., Fung, A., et al. (2012). “A systemic approach to deliberative democracy” in Deliberative systems: Deliberative democracy at the large scale. eds. J. Parkinson and J. Mansbridge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–26.

McGee, R., and Gaventa, J. (2011). “Shifting power? Assessing the impact of transparency and accountability initiatives.” IDS work. Pap, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. 383.

Mellinda Fatimah, M., Abdulkarim, A., and Iswandi, D. (2020). Increasing students' understanding of National Insights through digital literacy in civic education learning. Jurnal Civicus 20, 31–39.

Mendonça, R. F., Veloso, L. H. N., Magalhães, B. D., and Motta, F. M. (2024). Deliberative ecologies: a relational critique of deliberative systems. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 16, 333–350. doi: 10.1017/S1755773923000358

Mietzner, M. (2015). Dysfunction by design: political finance and corruption in Indonesia. Crit. Asian Stud. 47, 587–610. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2015.1079991

Moeis, F. R., Rudiarto, I., and Hadi, S. P. (2020). “Community participation in local governance and environmental management in Indonesia.” Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 11, pp. 877–886. doi: 10.14505/jemt.v11.4(44).16

Nabatchi, T., Gastil, J., Weiksner, G., and Leighninger, M. (2012). Democracy in motion: Evaluating the practice and impact of deliberative civic engagement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norton, A., and Elson, D. (2002). What’s Behind the Budget? Politics, Rights and Accountability in the Budget Process. London: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Nurjaman, A. (2020). The decline of Islamic parties and the dynamics of party system in post-Suharto Indonesia’, Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik (JSP, 27, 192–205. doi: 10.22146/jsp.79698

Nurmi, H. (2023). Deliberative democracy and incompatibilities of choice norms. Behav. Sci. 13:1035. doi: 10.3390/bs13120985

Nurshafira, T., and Alvian, R. A. (2019). Political economy of social entrepreneurship in Indonesia: a Polanyian approach. Jurnal Ilmu Sos. Dan Ilmu Polit. 22, 144–159. doi: 10.22146/jsp.27942

Pandey, P., and Pandey, M. M. (2015). “Research methodology” in Springer briefs in applied sciences and technology. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

Parkinson, J. (2006). Deliberating in the real world: Problems of legitimacy in deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parkinson, J., and Mansbridge, J. (2012). Deliberative systems: Deliberative democracy at the large scale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Plans, D., Case, T., Kırcami, A., and Erku, H. (2024). “Deliberative democracy and making sustainable and legitimate. ” Land. 13, 1–28.

Pratikno, (2005). Political parties in local governance in Indonesia: the case of Bantul. J. Soc. Issues Southeast Asia 20, 69–90. doi: 10.1355/SJ20-1D

Regus, M. (2020). The victimization of the Ahmadiyya minority group in Indonesia: explaining the justifications and involved actors. Religius J. Stud. Agama-Agama Dan Lintas Budaya 4, 227–238. doi: 10.15575/rjsalb.v4i4.10256

Sanders, L. M. (1997). Against deliberation. Polit. Theory 25, 347–376. doi: 10.1177/0090591797025003002

Sass, J., and Dryzek, J. S. (2024). Symbols and reasons in democratization: cultural sociology meets deliberative democracy. Theory Soc. 53, 883–904. doi: 10.1007/s11186-024-09551-w

Savaget, P., Chiarini, T., and Evans, S. (2019). Empowering political participation through artificial intelligence. Sci. Public Policy 46, 369–380. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scy064

Schmitt-Beck, R., and Schnaudt, C. (2023). Every day political talk with strangers: evidence on a neglected arena of the deliberative system. Polit. Vierteljahresschr. 64, 499–523. doi: 10.1007/s11615-023-00462-6

Schramme, T. (2021). Capable deliberators: towards inclusion of minority minds in discourse practices. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Polit. Philos. 27, 835–858. doi: 10.1080/13698230.2021.2020550

Setiawan, K. (2021). Women and politics in contemporary Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, G. (2009). Democratic innovations: Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stoddard, J., and Chen, J. (2018). The impact of political identity, grouping, and discussion on young people’s views of political documentaries. Learn. Media Technol. 43, 428–443. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2018.1504790

Verhasselt, L. (2024). Towards multilingual deliberative democracy: navigating challenges and opportunities. Representation 61, 57–74. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2024.2317781

Widianingsih, I., and McCourt, W. (2012). Understanding local governance reform in Indonesia: an examination of the Musrenbang process in Bandung. Public Adm. Dev. 32, 104–121. doi: 10.1002/pad.623

Keywords: deliberative democracy, urban policy, participatory governance, global south, Indonesia

Citation: Nurjaman A and Pinto JT (2025) Hybrid deliberative democracy in practice: a case study of community engagement and public decision-making in Malang City, Indonesia. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1658901. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1658901

Edited by:

Andrea De Angelis, Università degli Studi di Milano, ItalyReviewed by:

Wichuda Satidporn, Srinakharinwirot University, ThailandMochamad Iqbal Jatmiko, University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Nurjaman and Pinto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asep Nurjaman, YXNlcG51cmphbWFuNjhAZ21haWwuY29t

Asep Nurjaman

Asep Nurjaman Julio Tomas Pinto2

Julio Tomas Pinto2