- 1Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany

- 2School of Arts and Sciences, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia

As political actors, Orthodox Churches (OCs) attempt to define national identity and promote religious nationalism. This paper explores new forms of religious engagement in Greek and Georgian Orthodoxy, with a focus on the use of social media. In both countries, the church employs cultural capital to advance its discursive struggle for national identity while utilizes its veto power. These online discursive dynamics are more intense in Georgia, where the church’s political influence is greater. In Greece, the church is more cautious and limits its authority online to religious matters, avoiding high-stakes political debates. The interplay between national identity, religion, and digital space continues to shape political landscapes in Orthodox societies, with church-driven nationalism remaining a potent force.

Introduction

Revising the secularization thesis and considering new forms of religiosity is an established scientific discussion within the social sciences (Bronk, 2012); however, when examining Orthodoxy and desecularized national space, the prime empirical case is Russia, leaving other Orthodox countries in Europe understudied. The uniqueness of the Russian case is not an exception within the Orthodox world (Baar et al., 2022); the Georgian and Greek cases are also compelling prerequisites for studying the intersection between religiosity and national identity (Guglielmi and Piacentini, 2023). These countries represent unique occurrences where the intertwining of ethnic nationalism and Orthodoxy has not been thoroughly explored in the digital realm. Hence, it is essential to discuss desecularization tendencies in Orthodoxy and how they correspond to trends in the rest of the Christian world.

The ways Orthodox Churches (OCs) communicate with the public have changed over the years; in the 21st century, digitalization is increasing, and mass mobilization and the sharing of opinions and statements are now taking place solely in the digital space (Garaschuk and Sokolovskyi, 2025). Social Networks like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter (X), along with the official webpages of religious organizations, are extensively used to communicate with the parish and wider public at the national or international level. Hereafter, examining how desecularization is materialized in digital space can contribute to the body of knowledge on religion and digitalization. By analysing how OCs communicate and mobilize via digital platforms, we demonstrate that digitalization is transforming not only the methods of engagement but also the narratives of national belonging. Moreover, by focusing on the digital space, the article advances our understanding of how religious actors contribute to desecularization in the Orthodox context.

Orthodox Christianity is historically rooted in the Byzantine Empire, and it has always had a strong tradition of state-church ties (Meyendorff, 1982), which were embodied by the concept of Symphonia or Consonatia in Latin, illustrating accord between the Orthodox Church and the Emperor/King and later reincarnations of it in the face of representative government or a state (Leustean, 2011). Before discussing Symphonia, it is essential to distinguish between ethnic, civic, and religious nationalism. Ethnic nationalism focuses on shared ancestry and cultural identity, civic nationalism emphasizes shared citizenship and political rights, while religious nationalism binds national identity to a particular religious tradition (Smith, 2000).

To understand Eastern Christianity, the nationalistic character of OCs must be discussed in detail: how they interact with the state and society, and how they use their cultural capital as institutions, binding themselves to national identity. This outstanding characteristic could indirectly affect the consolidation of the state and stateness in Orthodox countries, as churches create an alternative narrative that relegates the nation’s secular characteristics (Linz and Stepan, 1996). It leads to the condition where right-wing political parties or movements, in their conservative nature, highly value affiliation with the church and often try to tangle their symbols and ideology with OCs. However, it is crucial to acknowledge liberal or secular counter-narratives that challenge this affiliation. For instance, in Georgia, secular actors also use digital platforms to promote a national identity that embraces diversity and modernity, often criticizing the Orthodox Church’s dominant role. In Greece, liberal voices frequently engage on social media to question the church’s influence in political and social matters, advocating for a separation between church and state.

Orthodox countries are diverse; however, Georgia and Greece, amongst them, share the distinctive role of religion in national identity and a strong OCs presence in everyday political life. Greece is a member of the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), while Georgia struggles to secure its EU and NATO future despite its current EU candidate status. Nevertheless, characteristics of Orthodox political thinking and widespread ethno-religious nationalism make them strong comparative cases. By comparing those two cases, we will observe the sources of differences and similarities between these countries. Hence, the contribution of this article is both empirical and theoretical, encompassing a comparison that provides new data to build future research on. The research timeline outlined in the article spans several key phases of the current history of chosen case studies, spanning from nineties until 2025. 2024–2025 is the timeframe for the collection and analysis of digital data from various platforms, including social media networks and official church websites, to assess how OCs engage with their congregants and the broader public. In-depth interviewing occurred in 2021–2022, and it covered the aforementioned main phases of Greek and Georgian history, respectively. This article makes a significant contribution to the literature on Orthodox Christianity by offering both theoretical and empirical insights into the relationship between religious engagement and national identity within the context of Georgia and Greece. Theoretically, it revises the prevalent secularization thesis by proposing a nuanced understanding of desecularization, particularly in Orthodox societies, thereby broadening the discussion to include countries often overlooked in contemporary studies. Empirically, the research provides a comparative analysis of the OCs’ use of social media and digital platforms, revealing how these institutions navigate and shape national identity narratives in the digital age. By examining the role of religious nationalism and the church’s strategic use of cultural capital in this dynamic environment, the study enhances our understanding of the intricate interplay between religion, nationalism, and digitalization, filling a crucial gap in the existing scholarship on religious studies and national identity in the Orthodox world.

The first part of the article discusses the Georgian case and how organized actions by right-wing populist parties and Russian influence attract the electorate and mobilze them around specific causes through digital spaces. The second part of the article will elaborate on the Greek experience with right-wing movements and their links to the church, subsequently reflected in digital religious discourse. The article uses qualitative data from in-depth interviews with political and clerical elites in Georgia and Greece, as well as from social media discourse analysis. Discourse analysis techniques will be used to code and systematize the data and to show the discursive struggle over the understanding of belonging to the nation: Greekness and Georgianness, respectively. The main questions of the article are as follows: how the clerical and political elite understand national belonging, and what conflicting narratives and discursive chains the agents capitalize on? And how is digital space utilized by religious actors?

Theoretical framework and methodology

Discursive struggle in the contested national (digital) space

The increasing role of religion in public space (Casanova, 1992, 2006) and the emergence of different forms of religiosity during the last few decades have led Berger (1999) to call the process desecularization and, furthermore, to define it, as Habermas (2008), Habermas (2006) does, as post-secular. Inglehart and Welzel (2005) tried to link increasing religiosity to several factors; economic development and existential threat were the main explanatory variables for the rise of religiosity in society. However, a detailed look, especially at Christian denominations, shows the differences and magnitudes in how countries vary on the scale from secular to non-secular. The literature shows that there are different trends in Catholic/Protestant Europe versus Orthodox Europe, and the leading factor is the post-communist historical-political experience of OCs (Northmore-Ball and Evans, 2016; Need and Evans, 2001). Within Orthodox Europe, Greece stands out as the only Orthodox country outside of the Iron Curtain, making it a distinctive and critical case to examine beyond the historical variable of post-communism and to assess the importance of religion in shaping national identity.

The symphonic ideal conceived in Byzantium seems to be a blueprint for most Orthodox countries; however, the varying degree of consolidation of state institutions in transitional Eastern Europe leads to varying degrees of church interference in political matters (V-Dem, 2023). This is especially pertinent for Greece, where the symphonic ideal operates within a longstanding framework of established state institutions, unlike in many post-communist Orthodox states. The symphonic ideal is a mere theoretical concept that imagines church-state relations, and the real difference lies within the state’s political environment. The degree of religion ingrained in national identity, and unholy alliances formed between the dominant religious institution, nationalistic groups, and political parties—often the ruling party—shape the boundaries of public influence.

As discussed, at both micro and mezzo levels, there is a set of variables interacting with the form and shape of religiosity and with how Orthodoxy is taking national spaces. By national spaces, we mean public spaces for demonstration, for defining what society strives for and what the state consists of. This national space is contested, as the church seeks to control all or some spaces in Orthodox countries, from mobilizing the parish and taking up physical space to defining national signifiers and the main characteristics of national identity. Religious engagement encompasses both behavioral and belief aspects of religiosity among the public, religious institutions, and the state.

The religious element in social mobilization could be exacerbated by the use of theological worldviews and religious spaces; however, how clerics interpret values, dogmas, and norms is the decisive factor in the nature of mobilization (Devine et al., 2015). Church is often used as a peace promoter and mediator; however, the organizational and political space provided by the dominant religion could be used to halt or nudge opportunities in divided societies. Therefore, historical political context is important for understanding how, why, and when the church’s mobilization potential is used. Sacralizing political and politicizing the sacral were the main trends observed under the Orthodox Church’s communion with right-wing political movements and ideas. Durkheim defines the sacred as something superior and absolute; the nation and political processes are sacralized in the post-secular context, where religion is taking public spaces, and the sacred is politicized to serve institutional purposes (Smith, 2000). Churches’ moralizing power and conservative declination make them ideal allies to the above-mentioned groups; however, taking into consideration the Orthodox Church’s mobilization power and its role as a veto player in society (Fink, 2009) makes those unholy alliances a hindrance to political transformation, as they directly affect stateness, which is particularly salient in the Georgian context.

Methodology

Social phenomena are never finished, and meaning can never be fixed. Hence, social struggle over the definition of identity is ongoing (Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002). A discourse is formed by the partial fixation of meaning around certain nodal points. A nodal point is a privileged sign around which the other signs are ordered; the other signs acquire their meaning from their relationship to the nodal point. In the national discourse, “the people” and, hence, the search for the meaning and identity of “the people” is the nodal point. However, certain elements of the discourse can be “floating signifiers” due to the different meanings ascribed to them (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985). Any attempt to define characteristics of the nation or the national identity leads to the understanding that it could be labeled as an “essentially contested concept” (Gallie, 1956; Collier et al., 2006; Boromisza-Habashi, 2010).

Fairclough’s (1995), Fairclough (2003) Critical Discourse Analysis will be utilized as a qualitative analytical approach to critically describe, interpret, and explain how discourses construct, maintain, and legitimize social inequalities. This approach asserts that discourses can be employed to resist power, challenge, and assert power, as well as to express knowledge and identity. Three-dimensional model (text analysis), mezzo (interpretation or linking production and consumption of text), and macro (explanation through social analysis) will be utilized to interpret how OCs are reproducing narratives in the digital space, with particular focus on Greece. This framework of critical discourse analysis will be used in the following chapters to analyse digital discourses around Georgianness and Greekness in the contested national space. To clarify the analytical framework for the discursive struggle, relevant indicators will be provided to demonstrate how discursive chains are identified, coded, and compared across the two cases. Both OCs possess cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1986), and all three forms of it (embodied, objectified, and institutionalized) are translated into their power to mobilize the masses and generate narratives. In the process of “discursive struggle” for hegemony (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985; Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002), the church wins over the right-wing conservative electorate while creating particular meanings for concepts that redefine national identity.

Religion and nation are the main nodal points and discursive signifiers; however, Georgianness and Greekness are empty signifiers that can be used and transformed by various discursive chains simultaneously. Two competing narratives on national identity are in a struggle in Greece and Georgia. In Greece, the narrative in which OCs are particularly active is exclusionary or ethnic nationalism, relying on ius sanguinis (acquisition of citizenship by descent) and a religious identifier, while the alternative is civil nationalism, leaning more on ius soli (acquisition by birth on the territory) and an inclusive characterization of national identity. None of the OCs is heterogeneous; however, we will code and observe their public output to demonstrate how Georgianness and Greekness are interpreted by OCs. The prevailing narrative of national identity is the one promoted by the actors with concentrated power. Given the state’s status as an actor, this narrative is reflected in public addresses, editorial sections of prominent national newspapers, social media discourse, and the state-sanctioned textbooks. We concentrate on the social media and elite discourse in this article; however, the analytical framework can be further expanded and reproduced by analysing other sources of the narrative.

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with political and religious elites and field experts. Elite interviewing poses a significant challenge, particularly given the sensitivity of topics such as the role of religious institutions in politics, the influence of the church on voters, and national identity. Interviewees may simply reflect their explicitly stated opinions on these subjects. To address this issue, elite interviewing was just one component of the research design; discourse analysis of the elite’s public statements was also employed. The target group included members of parliament (MPs), members of political parties, active politicians, and clerics of varying ranks, such as archbishops and bishops. In total, 28 interviews were conducted using the snowball sampling method, followed by transcription, coding, and analysis (see Supplementary material). Traditional outreach methods, such as emails or phone calls, often prove ineffective, particularly in challenging research environments (Bakkalbasioglu, 2020). Elite interviewing poses unique challenges in terms of sampling and access, particularly when using purposive sampling methods; hence, respondents might not fully represent the diversity of the political and clerical elites in Greece and Georgia. Given the tightness of the fieldwork timeframe and the difficulty of finding respondents willing to share their opinions, the sample is balanced. Four of the respondents are women (field experts and politicians, obviously, as there are no women allowed amongst the clergy in the Orthodox Countries). Respondents from the political elite represent both the ruling party and the opposition; however, they exclude far-right and ultra-nationalist parties. The rate of decline was exceedingly high, given the difficulty of the topic; approximately 100 interactions, only 28 were successful.

All social media accounts of the Greek and Georgian OCs were reviewed. The timeframe for analyzed posts is 2024–2025, focusing on major political and societal events. Facebook posts and comments were analyzed to examine how the church shapes the narrative of national identity and how society engages with and mimics it. The article will focus on the most-liked and commented posts and will choose a medium where the churches have greater public engagement. In both cases, this is their official Facebook page. The methodology has limitations, as only one medium is chosen for the analyses and only specific accounts are included. However, the assumption is that discourses represented by those pages can be generalized.

The coding process for this research involved a systematic approach to analyzing the discourse of OCs on national identity, especially how it is channel on social media platforms and official websites. Initially, qualitative data were collected from elite in-depth interviews and secondary sources, as well as various social media channels. The data were then organized into thematic categories based on key indicators such as expressions of nationalism, religious messaging, and community mobilization efforts. A grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) was utilized to identify patterns and recurring themes, ensuring that the coding process remained open to emergent concepts. This iterative coding entailed both open and axial coding phases, where initial categories were refined and interconnected to build a comprehensive understanding of how OCs navigate and shape narratives of national identity in the digital space. The findings were then cross-referenced to enhance validity and reliability, allowing for a nuanced analysis of the interplay between religion and national discourse in Georgia and Greece.

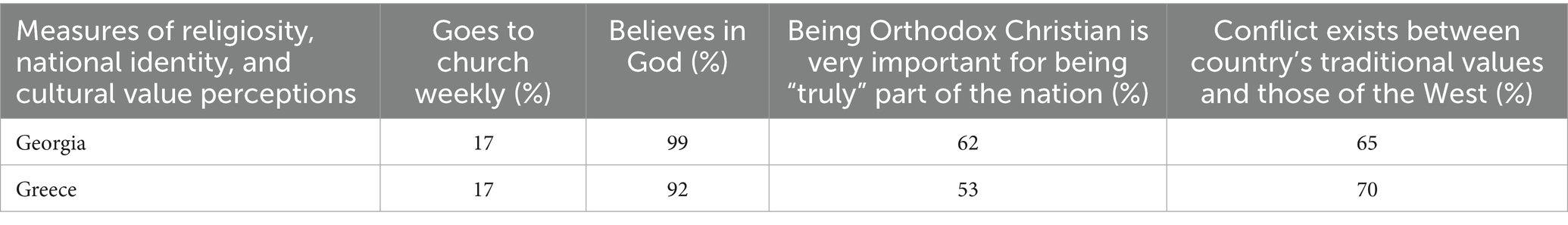

Claiming national digital space-Georgia

The central question we are posing is to what extent new mediating technologies, especially social media, change the ways in which people communicate about religious belief and practice especially in Orthodox societies, were believing without behaving is the dominant trend (Margvelashvili, 2016) versus to the original term “Believing without belonging” coined by Davie (1994), describing the UK case. Vekovic (2025) describes the Serbian (Orthodox Christian) case as believing without attending, and the same applies to Georgia as well. Church attendance is consistently low 38% report that they pray daily; 17% report that they attend church services weekly, while the most of the Orthodox countries report high numbers on the belief side, 99% of Georgians believe in God and additionally being Orthodox is believed to be the most important marker of the national identity—81% (Pew Research Center data, 2017). The data below show us that Georgia has the highest percentage of people identifying religion as the most important signifier. Where 62% of respondents said that, for being “truly” Georgian, being part of the dominant religious group (Orthodoxy) is particularly important. To compare, Serbia has a similar 59% and in Greece, 53% think that Greekness is linked with Orthodoxy. However, we have to mention that in Georgia, the highest percentage was given for family background and language. Hence, somehow materializing the famous motto by Ilia Chavchavadze: “Language, Homeland, Faith.” This is the sacred trinity of both secular and religious narratives on nationalism. GOC by canonizing the famous publicists and writers as saints, hegemonized discourse on nationalism (Table 1).

Table 1. Civil versus ethno-religious nationalism in orthodox versus catholic post-soviet space (Pew Research Center data, 2017).

The Georgian population is 3,704,500 people, of whom roughly 95% have a Facebook account,1 where the most important discussions, mobilizing, and organizing take place. “I love my Patriarch” is one of the biggest community groups in Georgian social media dedicated to the religious belief. It was created in 2009 and currently counts 363 thousand followers and claims to be the number one group in terms of activity on Georgian Facebook. However, the page has been inactive recently, and most religious discourse is concentrated on the official Facebook page of the Patriarchate of Georgia and on particular high-ranking clerics with social capital and, hence, influence. Zviadadze (2014) argued in her article that religion has become a key part of both offline and online spaces, with digital media affecting how religion is practiced, identified, and influencing the behavior and perspectives of internet users. The author also argued that Facebook acts as a powerful platform that allows users to express their religious identity. Simultaneously, it serves as a channel for spreading extremist religious ideologies, enabling fundamentalist groups and leaders to distribute their messages and rally large numbers of people without institutional backing. New media have amplified traditional religious expression, promoted popular religion, and demystified the world. Religion has become increasingly public, digital, and visible, and institutional religion (the GOC) is more powerful.

The digital presence of the GOC was slowly building. The official page of the Patriarchate of Georgia was created in 2016,2 and the public relations office of the Patriarchate of Georgia launched a Facebook page in 2019.3 These are the two main outlets of public discourse where citizens and parish members receive information, opinions, and announcements about the GOC. In 2021, the official Twitter (X) page of Patriarch Ilia the Second was created and mostly shares information in English; engagement on this platform is exceptionally low, so discussions are scarce. Twitter (X) has an exceedingly small share of the social media market in Georgia (3.49%), so this article will mostly focus on discourses on Facebook. Two additional sources of religious information and discourse are reproduced and recreated on the official webpage of the Patriarchate of Georgia4 and the TV Channel “Ertsulovneba,”5 created in 2009 alongside the radio channel.6 The YouTube page of the Patriarchate of Georgia7 was created in 2015 and mostly posts videos for people with hearing impairment, using Georgian sign language. Videos are thematical or just Sunday sermons of the Patriarch Ilia the Second and Patriarchal See Metropolitan Shio.

Social capital of the church

The Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC) is the most trusted institution in Georgia, and the data indicate higher confidence than for any other political institution; the trend is similar in the case of Patriarch Ilia II (CRRC, 2021). This cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1986) that GOC possesses, in all three forms (embodied, objectified, and institutionalized), is translated into its power to mobilize the masses and generate narratives. In the process of “discursive struggle” for hegemony (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985; Jørgensen and Phillips, 2002), the church wins over the right-wing conservative electorate while creating particular meanings for concepts that redefine national identity. Religion and nation are the main nodal points and discursive signifiers; however, Georgianness is an empty signifier that can be used and transformed by various discursive chains simultaneously. The GOC’s ascribed meaning of the Georgiannes is rooted in religion and its role in shaping national identity. However, using Christianity as a dominant signifier is a two-edged sword; it, on the one hand, links Georgia with European civilization and, on the other hand, creates loyalties to Russia as the standing bastion of Orthodoxy. This duality clashes with the state’s foreign policy choices.

Pew Research Center data (2017) showed that religion is perceived by Georgian society as an inherent part of national identity, and more secular characteristics are less appropriated. Since the independence of the Georgian state in 1991, the GOC has been at the forefront of the political process, and religiosity in society has continued to grow, with religion taking a greater share of public space both physically, through the construction of churches, and virtually, on a discursive level (Zedania, 2011). In 2003, the Rose Revolution brought civic nationalism, and it was not very well received by the church and consequently led to tensions with the state, in the end when in 2012 the important national election was held, Georgians saw the unprecedented activity of clerics in an electoral campaign, mostly supporting at that time opposition party and now ruling party “Georgian Dream” (GD) (Serrano, 2014). 2012 also marks the activation of various right-wing movements and political parties. Alliance of Patriots was the first among them, linking itself to the GOC for legitimization among the target group; it held four seats in parliament (during the 2016–2020 term) and was the only parliamentary far-right conservative group. Georgian Marsh, which was a movement from the beginning but became a political party; however, they could not win the parliament seats (only got 0.25 votes). In between was Levan Vasadze, the intriguing figure and leader of most of the rallies against holding LGBTQ demonstrations in Georgia (Kiparoidze, 2021). And finally, there is the latest group called “Alt-info,” they are the fastest growing network with their own television already and party offices all over Georgia, and the author of 2021, 5th of June havoc in Tbilisi, when once again church representatives, right-wing groups and Alt-info were defending the main avenue of Tbilisi not to let demonstrates protesting LGBTQ rights violations. The church officially opposed the demonstration organized by the NGO “Tbilisi Pride” and urged the state not to allow it; however, post-factum, they condemned the violence that occurred that day. By observing those three groups, the ruling party, and their relationship with GOC, we hypothesize that the church is creating discourse around Georgian identity to mobilize forces and the electorate and to hold leverage against the ruling party if it later decides to threaten its power and privileges. On the other hand, GD, as a rational institution, chooses to build on the narrative provided by the church, as during the electoral campaign, it needs to tap into the cultural capital accumulated by the GOC. This is a vicious circle, where the Georgian “imagined community” can and will not “imagine” themselves without religious identity.

There is a separate subject regarding Russia and its ties with the GOC or those right-wing groups. Foremost, we have to note that when regime change occurred, it directly brought about an altered political landscape toward the northern neighbor, colloquially known as the normalization process. Economic ties began to strengthen as inflows of Russian investment and tourists grew. GD often took cautious politics vis-à-vis Russia, especially on the Ukrainian issue, first about the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and lately on the Russian invasion of Ukraine. GOC itself holds strong ties with Russia, the majority of high-ranking church officials are Russian-educated, and the Patriarch met with the Russian president on several occasions. Their messages regarding liberalism and immorality coming to Georgia from outside replicated Russian propaganda messages. GOC opposed ratification of the anti-discrimination law, which served as a major benchmark for signing the Association Agreement with the EU (Civil.Ge, 2014). Church representatives organized a 2013 rally against the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia (IDAHOBIT) demonstration, which turned into violence from clerics toward demonstrators. Finally, the Georgian Marsh, Alliance of Patriots, and Alt-info all have ties and sympathies with Russia, and their discourse understands the West as a corrupt power, therefore proposing neutrality and normalization of relations with Russia as an outcome. The situation is somewhat different but similar on many levels in Greece; the main distinction lies in the strength of state institutions and institutional memory, which the Hellenic Republic has built over the years. The next chapter discusses the Greek case; however, first, we will discuss the study’s results in the Georgian case.

Results and discussion

The main discourse regarding national identity is who is “true” Georgian and if religion is the essential factor for true Georgianness. While GOC attempted to define religion as an inherent marker of the national identity, there is an opinion that it was an artificial process:

“When in reality the church never stood against the Soviet Union, it turned out after national movement (in the 90s) that it is the bastion of Georgian national identity. afterwards inertia brough this, next period Shevardnadze, Saakashvili and even today we have a kind of status quo that church is a protector of national identity” (#13, Georgian Expert, Theologian).

National Movement and in the early nineties, and the period of the first president of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, brought crystallization of the discourse around national identity, where diversity suffered:

“Certain slogans were created in the past, which did not bring good results for Georgia and its religious or ethnic diversity” (#12, Georgian Expert, Professor).

GOC is a big institution; it has a clear hierarchy; however, opinions by its representatives in public discourse vary. The official position is the one expressed through the public relations office of the Patriarchate of Georgia. There is a minority in Synod and in the clergy who are more liberal and open with the understanding of Orthodoxy; however, the discourse they are creating cannot afford to be hegemonic.

“I think the most important thing is who is Orthodox for the church because we already know who the Georgians are. As we already know, people sacrificed for Orthodox Christianity, Abo Tbileli, Shushanik was not an ethnic Georgian, but they are the flesh and blood of our church. So, the church is more interested in Orthodoxy than in Georgianness, thus in correct worship and in following God’s path. Because you can be Georgian, and we know many Georgians who have never done anything good for the country. And we also know a lot of personalities with other religions and homeland who sacrificed themselves for the unity and spirituality of Georgia” (#10, Priest, Georgian Orthodox Church).

The official Facebook group of the Patriarchate of Georgia is mostly used to communicate official announcements; however, the public relations page is more engaging in expressing opinions on certain topics. On the day of Georgia’s independence (26th of May), the GOC also joins the celebration with prayer, then visits the historical site of the battle where a memorial to national heroes is erected. Comments on such posts are usually positive; however, sometimes they take an antagonistic stance toward the church. Usually, there is no in-depth discussion of the post’s topic. Hence, the parish serves only as an active recipient of information. In posts about this very secular celebration, there is a constant emphasis on Georgia’s designation as a country under the patronage of the Virgin Mary. And “Peace, Strength, and Prosperity” are the main wishes the church materializes. On the day of “Family Purity,” which is celebrated on the 17th of May and was established by the Patriarchate of Georgia to hold a space both physical and national and push the IDAHOBIT away from the public discourse, GOC only shared photos of the celebration on the main street of the capital of Georgia. However, discussion in the comments revealed polarization among the public over this celebration.

“Mamuli, Ena, Sartsmunoeba” (მამული, ენა, სარწმუნოება—Homeland, Language, Faith) is a well-known triad that symbolizes Georgian national identity. This concept was articulated by the 19th-century publicist, politician, and writer Ilia Chavchavadze in a letter discussing the Georgian language and its status under Russian Empire rule. The triad highlights the significant role of language in modern nation-states, and, after Georgia gained independence from the Soviet Union in the late 20th century, it became a cornerstone of Georgian national identity. In addition to territoriality and language, religion serves as another key identity marker for Georgia, deeply rooted in its historical context of defining itself against Muslim neighbors and political adversaries. Meanwhile, Christianity has connected Georgia to Europe, which, despite its geographic distance, has remained culturally close to the Georgian people. During the nationalist movements of the early 1990s, this triad faced challenges; however, its significance diminished during the state’s democratic transformation, particularly among the younger generation.

A new interpretation of the sacral trinity emerged during the Spring 2024 demonstrations against the repressive “Russian Law” initiated by the Government of Georgia. Young protesters reshaped the slogan into “Homeland, Language, Unity” during a ceremonious and patriotic oath. This reinterpretation sparked extensive public discussion and drew criticism from state officials and the GOC. Both entities reaffirmed the importance of religion in defining national identity and rejected any changes to the established triad. This situation exemplifies the tension between secular and non-secular ideas regarding the nature of statehood in Georgia, highlighting the conflict between societal values and those of the church and state. The interplay of the sacred and the secular characterizes Georgia’s development from a failed state to a functioning hybrid regime. Notably, in 1987, as Georgia approached independence from the Soviet Union and the question of national identity became more pronounced, the GOC canonized Ilia Chavchavadze, bestowing upon him the title “Ilia the Righteous.” The appropriation of secular nationalist figures by the Orthodox Church is a recognized tactic, as seen in the canonization of kings and other significant historical figures important to the nation, not only in Georgia but also in other Orthodox countries.

In conclusion, the Orthodox Church of Georgia uses digital space to amplify its narrative on Orthodoxy as an integral part of national identity; however, the GOC remains skeptical of technology, and there is no direct engagement with the public; rather, discussions are closed, and narratives are official and set. This authoritarian tendency of a closed society is an embodiment of the current anti-democratic, anti-secular political atmosphere of Georgia.

Greek Orthodox Church and the politics of nationalism

There are two major attitudes in Orthodoxy toward the digitalization of religiosity: one in which the church benefits from the internet influencing large numbers of “digitally educated” non-religious people, and the second, a distrust of new digital technologies (Volkova, 2021). Both of these attitudes are present in two comparative cases, namely Greece and Georgia. Greece presents a unique perspective due to its high church attendance and status as an Orthodox country with a state religion, influencing both political and societal structures. Georgia, on the other hand, offers insight through its widespread social media usage and its journey of religious digitalization, providing a contrast in how Orthodoxy interacts with digital spaces. Both countries have seen their OCs increasingly adopt digital platforms over the past 5 years, highlighting diverse and significant engagements with modern technology.

Greece and the Greek Orthodox Church (GrOC) are unique subjects to study for numerous reasons. It is the only Orthodox Church in Europe left on the other side of the Iron Curtain and without Soviet rule or allies. Church attendance in Greece is among the highest in South-Eastern Europe. Notably, Greece is the only Orthodox country with a state religion. This distinct status significantly enhances the GrOC’s influence on policymaking by intertwining religious and political dynamics. This close relationship ties the knot between the GrOC and the state; it is not on the surface and may take an informal form in some instances, although the church’s involvement in the political process is apparent (Fokas, 2009). So, what is the relationship between the ruling party, Nea Demokratia, GroC and Greek Solution (Ethniki Lysi), which currently holds 12 parliamentary seats and two seats in the European Parliament, is interesting to discuss and see how those political parties are utilizing church support, and in response, how the church’s motives are.

Facebook usage in Greece is lower than in Georgia, where only 65% of the population has an account. Moreover, Twitter has an even lower share of the social media market, amounting to only 1.91%. Church attendance is consistently 29% in Greece; 16% in Greece report that they attend church services weekly, while most of the Orthodox countries report high numbers on the belief side 92% of Greeks believe in God, and additionally, being Orthodox is believed to be the most important marker of the national identity −76% (Pew Research Center data, 2017). The table below shows the two sides of religiosity: Georgia and Greece dominate the list, where the majority of the population believes in God; however, only a fraction practices religion, especially in its institutionalized form. This suggests that while digital platforms like Facebook and Twitter are not widely used for religious purposes, a significant segment of the population may express their beliefs digitally or through ethno-religious nationalism. This highlights a complex relationship between digital religiosity and national identity, where digital engagement is not merely a reflection of religious activity but also a nuanced expression of national consciousness within Helleno-Christianism. As Chrysoloras (2013) argued, throughout the era of nation-building and the shaping of national identity, various competing nationalist ideas aimed to secure the loyalty of both the populace and the state while defining what it means to be “Greek.” From these ideological conflicts, Helleno-Christianism emerged as the dominant form of Greek nationalism, solidifying Orthodoxy’s role as a fundamental aspect of Greek identity. Today, Helleno-Christianism remains the primary lens through which Greek national identity is understood. Quantitative data and qualitative observations support the same (Table 2).

Table 2. Belief versus behavioral patterns, markers of national identity and cultural conservatism in Greece and Georgia (Pew Research Center data, 2017).

The main active digital outlet for the Orthodox Church of Greece is its official webpage, which features a well-developed English version that is highly informative and interactive.8 They also own a Radio station,9 with a long history, which also broadcasts on YouTube. There is no official TV channel; however, there is a private TV channel, 4E, founded in Thessaloniki, which is solely devoted to Greek Orthodoxy.10 The Church of Greece does not have an official presence on YouTube; however, it does have an account on X (Twitter) created in 2014.11 Their X account has been inactive since the last post in 2024; however, the Facebook account is fairly active. The activity on their Facebook page, albeit limited, continues to facilitate community engagement and ensure the church’s presence in digital discourse. Despite these efforts, the overall impact of digital platforms on enhancing the church’s authority remains less prominent than in Georgia, where the church’s digital engagement appears more robust.

Social capital of the church

Despite the legal presupposition, following the Symphonic tradition, both the church and the state in Greece tend to control the situation or to cooperate (Georgiadou, 1995). Thus, there were several crises related to the Orthodox Church, which defined its stance in Greek society. Primarily, there was an ID card issue when religious affiliation was removed; Nea Demokratia, at the time, was on the GrOC side (Chrysoloras, 2004). The religious oath is an interesting feature of the political process in parliament. New Democracy party members took a religious oath, while the previous government and prime minister from Syriza (leftist party) leaned toward the civil oath. In recent years, Tsirpas (Syriza) has tried to negotiate a deal with GrOC to transform the model of the relationship between church and state, especially regarding finances. Where the status of the clerics as public officials was supposed to be abolished, however, Archbishop Ieronymos endorsed the Synod that rejected it, and the status quo remains.

The institutional grip the church has on the government is reflected in the conjoining of the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, which gives GrOC direct access to the educational system. Religious classes are obligatory and, in some cases, if parents wanted to be exempted, they had to swear that they were not Orthodox Christians, which, as European Court of Human Rights (EHCR) ruled, breached EU laws (Ekathimerini, 2019). Hence, Nea Demokratia is part of the religious nationalism discourse, in which Greekness is equated with Orthodoxy. Their close ties with the church certainly helped them win the election. As far as the Greek Solution is concerned, they hold far-right views on migration and LGBTQI rights, and are strong advocates of Orthodox Christianity, together with promoting ties with Russia. Such politics as they envision will enforce trade and cultural relations and help Greece overcome its economic problems. As Georgiadou (2019) described, the Greek Solution is just trying to capitalize on the pro-Russian sentiment already existent in large parts of Greek society. The party’s populist agenda and denunciation of the Prespa Agreement created a party stronghold in Northern Greece. Another interesting phenomenon is the Holy Mountain of Athos, which Putin famously visited in 2016. It is an autonomous entity, and, as discourse analysis shows, it is perceived as one of the entities associated with pro-Russian sympathies.

Another example of collaboration with far-right groups is the relationship between Golden Dawn and GrOC. The upheaval of this ultranationalist party occurred during the Greek debt crisis, and in 2015, they were the third most popular party in parliament; however, their popularity has since plunged, and in 2020, their leadership was charged and sent into detention. Papastathis (2015) argued that the GrOC’s engagement in political discourse, which mediates between nationalist, populist, and authoritarian value systems, has significantly contributed to the growth of the Golden Dawn. Rather than acting as a primary driving force, it has served as a fertile ground for the social legitimization of ideas that are key components of the party’s ideology. On the one hand, the church’s monopoly over religious influence, combined with strong anti-immigrant sentiment within Greek society, can be seen as a potent “cultural factor” in this development.

A survey conducted in the late 2010s indicated that regions with greater clerical engagement with Golden Dawn saw higher voter turnout for the party. On the other hand, the clergy’s ambiguous position toward the party may have inadvertently encouraged voting for it. Interviews with local leaders suggested that, instead of actively working to dissuade the religious community from supporting the Golden Dawn, religious leaders have tended to express their opposition abstractly and diplomatically, opting not to engage in a social alliance against it. This church strategy appears to stem from the concern that an open confrontation with the Golden Dawn could jeopardize the Orthodox Church of Greece’s crafted myths and ideological foundations, given the party’s strategic appropriation of Orthodoxy as part of national identity and its role in shaping traditional values (Papastathis, 2015).

Two cases from the current history of church-state relations in Greece can be discussed in full length to demonstrate the church’s veto-player status and its mobilizing power. One is an identity card crisis, and the other is an issue with the name of Greece’s northern neighbor state. In both cases, the state prevailed; however, GrOC fully exercised its bargaining power, in addition to winning the discursive struggle. To assert its stance, the Church of Greece held public rallies in Athens and other locations across the country, attracting large crowds who protested against perceived threats to the nation’s Christian identity. For added impact, the sacred banner of the Greek Revolution was brought from the Monastery of Agia Lavra near Kalavryta in the Peloponnese and raised by the archbishop, symbolizing the church’s claimed role in national affairs. Such instances illustrate how the GrOC’s mobilizing strategies and symbolic actions reinforce its position as a significant veto player in Greek politics, capable of swaying public opinion and influencing governmental decisions.

In addition to the rallies and the official statements from the Holy Synod, which emphasized the importance of preserving the “unique national character” of the Greek people, the church initiated a national referendum by collecting signatures in parishes across its dioceses. Over 3 million individuals signed in support of making the declaration of religion on ID cards optional. This demonstrated the Church of Greece’s significant strength. However, the government remained resolute, stating that the matter was settled and that the law would be enforced.

When the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia gained independence in 1992 following the dissolution of Yugoslavia and adopted the name “Republic of Macedonia,” it sparked strong reactions in Greece, fuelled by concerns over potential territorial claims on Greek Macedonia. The Holy Synod addressed these fears in a June 5, 1992 statement. Large public demonstrations in places like Athens and Thessaloniki provided a platform for church leaders to express their opposition to the inclusion of the term “Macedonia” in the new country’s name, viewing it as a threat to Greece’s heritage. This issue has remained particularly sensitive in northern Greece. The topic resurfaced urgently in early 2018 during negotiations between the two nations regarding the name, prompting the Holy Synod to reiterate the church’s objections to granting the name “Macedonia” to their northern neighbor. Following the signing of the Prespa agreement in June 2018, there were symbolic protests and rallies in Athens, Thessaloniki, and other northern regions, where bishops and clergy spoke out (Kitromilides, 2020).

The autocephalous Greek Church has played a dual role in recent Greek history, functioning not only as a state-supported institution but also as an ideological tool that legitimizes the state’s authority. The church has often “blessed” government decisions, securing its privileged position within the Greek legal framework (Hellenic Parliament, 2008). It perceives itself as the guardian of tradition and national identity, embodying what it defines as the “true” Greek spirit (Chrysoloras, 2013). The close ties between the church, political parties, and society have persisted. Both the church and the political parties seem disinclined to change this status quo. Since the late 1980s, even the center-left PASOK party appears to have abandoned efforts to modify or mitigate the situation. The church’s political adaptability and its tendency for unsolicited, non-partisan involvement have effectively transformed it into an extension of state authority (Georgiadou, 1995). This populist narrative resonates with the wider public and, hence, GrOC dominates the discursive struggle to define “Greekness.”

Results and discussion

The GrOC has been a pivotal custodian of Greek identity, particularly during the centuries of Ottoman rule when the survival of Greek cultural and national consciousness was intricately linked to religious affiliation (Chrysoloras, 2013) The deep-rooted connection between religion and national identity, along with the lack of robust religious pluralism, remains a fundamental aspect of the Greek political system, further solidifying the dominant role of the Church of Greece in society. “By embracing the logic of nationalist ideology, the GrOC presents itself as the sole authentic defender of cultural heritage, of traditional values, and of national interests, most notably in periods of crisis, and legitimates itself as a public authority parallel to the state”—denote Kaltsas et al. (2022).

Orthodoxy transcended linguistic and regional divisions among Greeks, serving as one of the few cohesive forces that sustained a sense of collective belonging amid political subjugation. In this historical setting, the church functioned not only as a spiritual institution but also as a cultural and social nucleus that preserved Hellenic traditions, fostering an ethnic cohesion which was sometimes more potent than linguistic commonality itself. This role of Orthodoxy as a foundational cultural marker provided the substrate for the eventual emergence of a Greek national consciousness. In contemporary times, the church extends this custodian role into the digital realm, where it stewards online narratives that echo its historic task of preserving cultural identity. Discourse around national identity is more complex in Greece and somewhat crystallized; hence, the discursive struggle is less intense than in Georgia.

“For historical reasons, of course, there is no way to deny the role of the Orthodox church… in the Greek language, you have two different words, the first word is ethnos, and it is disconnected from the word national. Ethnos in Greek comes from the word ethos and means “habits”. It is not connected with race or with the blood; it is connected with everyday life in reality. The second word you have is Yenos. There is no word in the English language that I know for Yenos, and when we talk in English, we use “nation” for ethnos and “Yenos,” but there is a significant difference: Yenos is associated with religion. In Greek, Yenos is associated with birth” (#18, Greek Public Official, religious affairs).

This dynamic is illuminated by studies emphasizing that the church’s religious identity was inseparable from ethnic affiliation, creating a proto-national identity that conflated belonging to the Orthodox faith with Greekness (Roudometof, 2011). The ethno-religious identity served as a critical element within the fragmented Ottoman social order, where political and national identities were nascent. The Orthodox Church’s capacity to preserve Greek culture and collective identity, even in a multilingual and multicultural context such as Ottoman Cilicia, underlined its role as a resilient bastion of community cohesion and cultural continuity (Seifried, 2020). However, there is a difference between state and church discourse: the state seeks to fit within the civic nationalism framework, while the church attributes ethno-religious markers to national identity.

“So, Herodotus, the ancient author, writes somewhere in his work Historia. Greekness has to do with blood, yes, with language, with religion, and with ethics or morals. The way of life, so to speak” (#21, Greek cleric, Synod).

Since the Greek Church declared its autocephaly in 1833, its relationship with the state has generally been harmonious. However, this cooperative dynamic began to erode in the early 1980s when the center-left Pan-Hellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) came to power. From the outset, PASOK sought to implement a series of secularizing reforms, such as civil marriage and divorce, which the church viewed as a direct challenge to its dominant role in Greek society. Tensions escalated when the charismatic Archbishop Christodoulos succeeded Archbishop Seraphim as the head of the church in 1998. The period following Christodoulos’s enthronement in 1998 marked a significant transformation in the church-state dynamic. In this context, Helleno-Christian nationalism emerges as the overarching political ideology, asserting that Greek national identity rests on two primary foundations: the legacy of ancient Hellenic culture and Orthodox Christianity. Depending on historical circumstances, language and geography have been included as a third pillar alternatively. Nonetheless, the themes of ancient Greece and Orthodoxy have consistently served as pivotal reference points.

Leadership within the GrOC has been instrumental in shaping the national discourse around identity. Prominent figures, most notably Archbishop Christodoulos (1998–2008), actively crafted and promoted narratives linking Orthodoxy to Greek cultural and political identity. His tenure marked a period of heightened public visibility for the church, during which religious authority was mobilized to advance a collective Greek consciousness that connected historical legacy, religion, and national pride (Roudometof, 2011; Roudometof and Markides, 2010). These church leaders deliberately constructed narratives that intertwined faith with cultural nationalism, presenting Orthodoxy as the spiritual and civilizational core of Hellenism. Archbishop Christodoulos’ vision extended to framing Greece’s place within a broader civilization linked to Orthodox Russia, positing a pan-Orthodox cultural bloc as a counterweight to Western European influences (Trantas, 2020). Such efforts demonstrate how religious leadership can influence not only cultural discourse but also aspirations for geopolitical identity.

However, the church’s engagement in public debates is calibrated, with its authority being more pronounced in ecclesiastical or religious matters and comparatively constrained in broader political or geopolitical issues. This selective involvement reflects the church’s strategic positioning to maintain influence in national identity debates while avoiding overreach into political spheres where its authority may be contested (Asproulis, 2019). This is the key difference from Georgia, which Greece experiences.

Digital engagement with the GrOC is less prominent than in Georgia. The discussions or comments on their Facebook page are scarce, and it is mostly used to share information from the official site. The Church of Greece has established a significant online presence through official websites and digital portals to disseminate religious information, doctrinal teachings, and institutional communications. These platforms are carefully curated to reflect theological continuity and uphold tradition, emphasizing the church’s role as a custodian of Greek Orthodox heritage. The content typically includes liturgical calendars, official statements, doctrinal clarifications, and news related to ecclesiastical activities, thus projecting an authoritative voice in the digital domain (Karyotakis et al., 2019; Sakorrafou, 2024). Discursively, the church’s websites articulate a narrative that connects religious tradition with national identity, reinforcing the idea of Orthodoxy as integral to Greek culture and history. These communications often emphasize themes of continuity, divine providence, and moral guidance, framing the church as both a spiritual and cultural pillar that sustains national coherence.

Conclusion

Research shows that in desecularized societies, where the church is dominant in the physical or digital national space, the church’s role significantly shapes public and political discourse. This provides a backdrop for understanding the dynamics explored in both Greece and Georgia. To summarize, the same discursive struggle is apparent in both countries; however, it emerges from different starting points for the participating actors. Discursive chains are less in conflict in Greece, whereas in Georgia they are represented by two poles, with the GOC in between trying to balance. In the Georgian case, the church’s involvement in political affairs further polarizes society due to still-fragile state institutions. Meanwhile, in Greece, institutional memory is long-standing, with religion being so ingrained in every aspect that it does not pose any immediate challenge to the stateness. This institutional memory contributes to lower discursive conflict by underpinning stable norms of debate. Additionally, in both Greece and Georgia, the church uses the cultural capital it has accumulated through its extensive role in nation formation to mobilize the masses and generate narratives. This mobilization feeds into the religious nationalism discursive chain and is utilized in the “discursive struggle” for hegemony.

This discursive struggle is mirrored in social media, however, to a lesser extent in Greece than in Georgia. The main explanatory variables could be institutional memory in building democracy and a wide variety of outlets for exchanging opinions and mobilizing the electorate/parishioners. In Greece, the church engages in public digital debates with care. Its authority is more prominent in ecclesiastical or religious matters, while it is more limited in broader political or geopolitical issues. This selective digital involvement shows the church’s strategic aim to maintain influence in discussions about national identity while steering clear of political areas where its authority could be challenged. In Georgia, however, the Orthodox Church is, in the majority of cases, not challenged in political issues; hence, the church-state barrier is weaker, and the GOC exerts some influence on the political transformation process and election results. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that other factors could also play a role in these dynamics. The varying levels of media freedom, government regulations, and civic engagement in both countries might further shape these interactions. Ultimately, this underscores how the interplay between national identity and religion continues to shape political landscapes, leaving us with a profound realization: church-driven nationalism remains a critical force in shaping the course of history in Orthodox Societies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the study did not aim to collect individual identifiable data on humans, it observed discourses. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The author acknowledges financial support from the Lehman Haupt International Doctoral program at Ilia State University and the University of Göttingen during the preparation of this article. Volkswagen Foundation and Shota Rustaveli National Scientific Foundation of Georgia funded this program (No. PhD-18/0573). Additionally, a doctoral grant (PHDF-22-1956) from the Shota Rustaveli National Scientific Foundation of Georgia also contributed to the completion of this article. Financial support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University is also acknowledged.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Eva-Maria Euchner and Simon Fink for their support during the article development.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. To aid the literature review process and find new sources. Also to proofread the article and correct grammar and stylistical mistakes.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1659335/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1 ^Facebook users in Georgiahttps://stats.napoleoncat.com/facebook-users-in-georgia/2024/05/#:~:text=There%20were%203%20709%20900,women%20lead%20by%20,103%20,500.

2 ^https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100064771030174#Official Page of the Georgian Orthodox Church on Facebook.

3 ^https://www.facebook.com/sazupatriarchateOfficial Page of the Public Relations office of the Patriarchate of Georgia on Facebook.

4 ^https://patriarchate.ge/Official webpage of the Patriarchate of Georgia.

5 ^https://sstv.ge/Ertsulovneba-TV channel of the Patriarchate of Georgia.

6 ^https://radioiveria.ge/geo/Radio of the Patriarchate of Georgia.

7 ^https://www.youtube.com/@patriarchateofgeorgia797Official Youtube page of the Patriarchate of Georgia.

8 ^https://www.ecclesiagreece.gr/English/EnIndex.htmlOfficial webpage of the Church of Greece.

9 ^https://ecclesiaradio.gr/Official Radio of the Church of Greece.

10 ^https://tv4e.gr/TV4E, Private TV channel on Orthodoxy.

11 ^https://x.com/Ecclesia_grOfficial account of the Church of Greece on X (Twitter).

References

Asproulis, N. (2019). “Orthodoxy or Death”: Religious Fundamentalism during the Twentieth and Twenty- first Centuries. In Fundamentalism or Tradition: Christianity after Secularism. Ed. A. Papanikolaou and G. Demacopoulos. (pp. 180-203). New York, USA: Fordham University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780823285815-011,

Baar, V., Solík, M., Baarová, B., and Graf, J. (2022). Theopolitics of the orthodox world—autocephaly of the orthodox churches as a political, not theological problem. Religion 13:116. doi: 10.3390/rel13020116

Bakkalbasioglu, E. (2020). How to access elites when textbook methods fail? Challenges of purposive sampling and advantages of using interviewees as “fixers”. Qual. Rep. 25, 688–699. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2020.3976,

Berger, P. L. (1999). The Desecularization of the world: Resurgent religion and world politics. Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Boromisza-Habashi, D. (2010). How political concepts are ‘essentially’ contested?. Language & Communication. 30, 276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.langcom.2010.04.002

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital” in Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. ed. J. Richardson (Westport, CT: Greenwood), 241–258.

Bronk, A. (2012). Secular, secularization, and secularism: a review article. Anthropos 107, 578–583. doi: 10.5771/0257-9774-2012-2-578

Casanova, J. (2006). Rethinking secularization: a global comparative perspective. The Hedgehog Review, 8,7–22.

Chrysoloras, N. (2004). Why orthodoxy? Religion and nationalism in Greek political culture. Stud. Ethnicity Nat. 4, 40–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9469.2004.tb00057.x,

Chrysoloras, N. (2013). Orthodoxy and the formation of Greek national identity. Chronos 27, 7–48. doi: 10.31377/chr.v27i0.403

Civil.Ge (2014). Georgian Church speaks out against anti-discrimination bill. Available online at: https://old.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=27175 (Accessed March 15, 2024).

Collier, D., Daniel Hidalgo, F., and Olivia Maciuceanu, A. (2006). Essentially contested concepts: Debates and applications. Journal of Political Ideologies, 11, 211–246. doi: 10.1080/13569310600923782

CRRC (2021). Trust toward religious institutions. Caucasus barometer 2021 Georgia. Available online at: https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb2021ge/codebook/ (Accessed April 1, 2024).

Davie, G. (1994). Religion in Britain since 1945: believing without belonging. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Devine, J., Brown, G., and Deneulin, S. (2015). Contesting the boundaries of religion in social mobilization. J. South Asian Dev. 10, 22–47. doi: 10.1177/0973174115569035

Ekathimerini (2019). Greece brakes EU rules on religious education classes. Available online at: https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/245997/greece-breaks-eu-rules-on-religious-education-classes/ (Accessed April 1, 2024).

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. New York, London: Routledge.

Fink, S. (2009). Churches as societal veto players: religious influence in actor-centred theories of policy-making. West Eur. Polit. 32, 77–96. doi: 10.1080/01402380802509826

Fokas, E. (2009). Religion in the Greek public sphere: nuancing the account. J. Mod. Greek Stud. 27, 349–374. doi: 10.1353/mgs.0.0059

Gallie, W. B. (1956). Essentially Contested Concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 56, 167–198. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4544562

Garaschuk, D., and Sokolovskyi, O. (2025). Digital orthodoxy and political populism in Eastern Europe: how orthodox media facilitate political mobilization. Occas. Pap. Relig. East. Eur. 45:6. doi: 10.55221/2693-2229.2650

Georgiadou, V. (1995). Greek orthodoxy and the politics of nationalism. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 9, 295–315. doi: 10.1007/BF02904337

Georgiadou, V. (2019). The state of the far right in Greece. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Available online at: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/athen/15846.pdf (Accessed January 25, 2025).

Glaser, G., and Strauss, L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research, vol. 17. (New Brunswick, U.S.A. and London, U.K: AldineTransaction, A Division of Transaction Publishers), 364.

Guglielmi, S., and Piacentini, A. (2023). Religion and National Identity in central and eastern European countries: persisting and evolving links. East Eur. Polit. Societies Cult. 38, 455–485. doi: 10.1177/08883254231203331,

Habermas, J. (2006). Religion in the public sphere. Eur. J. Philos. 14, 1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0378.2006.00241.x

Habermas, J. (2008). Notes on post-secular society. New Perspect. Q. 25, 17–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5842.2008.01017.x

Hellenic Parliament (2008). The constitution of Greece. Available online at: https://www.hellenicparliament.gr/UserFiles/f3c70a23-7696-49db-9148-f24dce6a27c8/001-156%20aggliko.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2024).

Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change and democracy: The human development sequence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jørgensen, M., and Phillips, L. J. 2002. Discourse analysis as theory and method. London: SAG Publications Ltd (Accessed February 26, 2025).

Kaltsas, S., Karoulas, G., Karayiannis, Y., and Kountouri, F. (2022). The political discourse of the Church of Greece during the crisis: an empirical approach. Religion 13:273. doi: 10.3390/rel13040273

Karyotakis, M.-A, Antonopoulos, N., and Saridou, T. (2019). A case study in news articles, users comments and a Facebook group for Article 3 of the Greek Constitution. KOME−An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry. 7, 37–56. doi: 10.17646/KOME.75672.31

Kiparoidze, M. (2021) Georgian far right launches disinformation campaign following death of journalist beaten in anti-LGBTQ attack. Coda. Available online at: https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/far-right-lgbtq-georgia/ (Accessed April 1, 2024).

Kitromilides, P. (2020). “Church, State and Hellenism” in The Oxford handbook of modern Greek politics. eds. K. Featherstone and D. Sotiropoulos (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Laclau, E., and Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. London: Verso Books.

Leustean, N. L. (2011). The concept of symphonia in contemporary European orthodoxy. Int. J. Study Christ. Church 11, 188–202. doi: 10.1080/1474225X.2011.575573

Linz, J., and Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of democratic transition and consolidation. Southern Europe, South America, and post-communist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Margvelashvili, K. (2016). “Influence of church: political processes and election in Georgia” in Religion, society and politics in Georgia. ed. N. Gambashidze (Tbilisi: The Caucasus Institute for Peace and Development), 4–14. (In Georgian)

Meyendorff, J. (1982). The byzantine legacy in the orthodox church. Crestwood, N.Y: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Need, A., and Evans, G. (2001). Analysing patterns of religious participation in post-communist Eastern Europe. Br. J. Sociol. 52, 229–248. doi: 10.1080/00071310120044962,

Northmore-Ball, K., and Evans, G. (2016). Secularization versus religious revival in Eastern Europe: church institutional resilience, state repression and divergent paths. Soc. Sci. Res. 57, 31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.11.001,

Papastathis, K. (2015). Religious discourse and radical right politics in contemporary Greece, 2010–2014. Polit. Relig. Ideol. 16, 218–247. doi: 10.1080/21567689.2015.107770

Pew Research Center data (2017). “Religious belief and National Belonging in central and Eastern Europe”. Available online at: https://www.pewforum.org/2017/05/10/religious-belief-and-national-belonging-in-central-and-eastern-europe/ (Accessed March 20, 2024).

Roudometof, V. (2011). Eastern orthodox Christianity and the uses of the past in contemporary Greece. Religion 2, 95–113. doi: 10.3390/rel2020095

Roudometof, V., and Markides, N. (Eds.) (2010). Orthodox Christianity in the 21st century Greece. The role of religion in culture, ethnicity, and politics. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

Sakorrafou, S. (2024). Greek orthodox perception of communication technology: past and present. Christ. Perspect. Sci. Technol. New Series 3, 27–60. doi: 10.58913/IXKG8073

Seifried, R.M 2020. The legacy of byzantine Christianity in the southern Mani peninsula, Greece, after imperial collaps. Chapter in the bookby: J.M.A. Murphy (Ed.). Rituals, collapse, and radical transformation in archaic states (1). New York: Routledge.

Serrano, S. (2014). The Georgian Church. Russ. Polit. Law 52, 74–92. doi: 10.2753/RUP1061-1940520404

Smith, A. (2000). The ‘sacred’ dimension of nationalism. J. Int. Stud. 29, 791–814. doi: 10.1177/03058298000290030301,

Trantas, G. (2020). “Shifting the Centre of Gravity of Greek orthodox EU policies: a matter of leadership?” in Coping with change: Orthodox Christian dynamics between tradition, Innovation, and realpolitik. eds. V. N. Makrides and S. Rimestad (Berlin: Peter Lang), 127–146.

V-Dem (2023). Variable - Religious Organization Consultation. Available online at: https://www.v-dem.net

Vekovic, M. 2025. Belonging without attending? National Identity and contemporary religious patterns in Serbia. In: M Tolvan der, S Johnson, P Kratochvíl, and Z Grozdanov (eds) The many faces of Christianism. Leiden/Boston: The ‘Russian world’ in Europe, 210–229.

Volkova, Y. A. (2021). Transformations of eastern orthodox religious discourse in digital society. Religion 12:143. doi: 10.3390/rel12020143

Zedania, G. 2011. The rise of religious nationalism in Georgia. Identity Studies in the Caucasus and Black Sea Region. Vol. 3 (Accessed March 20, 2024).

Keywords: Orthodox Christianity, religious nationalism, religious engagement, contested national space, digital religion

Citation: Margvelashvili K (2025) Contested national and digital space, the Orthodox Church, and the new forms of religious engagement: comparative insights from Georgia and Greece. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1659335. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1659335

Edited by:

Eva-Maria Euchner, Fliedner Fachhochschule Düsseldorf, GermanyReviewed by:

Marko Vekovic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaSandrina Antunes, Universit of Minho, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Margvelashvili. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristine Margvelashvili, ay5tYXJndmVsYXNodmlsaUBzdHVkLnVuaS1nb2V0dGluZ2VuLmRl

Kristine Margvelashvili

Kristine Margvelashvili