- Department of Government Studies, Universitas Muhammadiyah Buton, Baubau, Indonesia

Introduction: This study examines how clientelism, coalitions, and political concessions shape democratic costs in local elections, with political pragmatism as a mediating factor.

Methods: We conducted an anonymous survey of 100 voters in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Hypotheses were tested using PLS-SEM with bootstrapping to assess direct and indirect effects.

Results: Clientelism does not directly affect democratic costs but has an indirect effect via political pragmatism. Coalitions reduce democratic costs. Concessions increase democratic costs both directly and indirectly. Pragmatism significantly predicts democratic costs. Measurement indices met conventional thresholds.

Discussion/Conclusion: Pragmatism mediates how informal elite practices impact democracy: coalitions mitigate costs, while clientelism and concessions increase them. Policies should target transactional incentives and strengthen programmatic competition at the local level.

1 Introduction

The resilience of democracy has become a central theme in comparative politics, especially in contexts where democratic institutions coexist with pervasive informal practices (Kroeger, 2020). While democratic consolidation is typically assessed through the strength of formal rules and institutions, scholars increasingly recognize that informal political strategies such as clientelism, elite coalitions, and political concessions play a decisive role in shaping the quality of democratic governance (Kim, 2016). These practices are not only features of transitional regimes but also persistent mechanisms that affect the everyday functioning of electoral politics. The costs to democracy are often subtle: weakening electoral accountability, blurring programmatic competition, and reinforcing pragmatic rather than principled political behavior (Lust and Rakner, 2021).

Research on democratic costs has generally emphasized the detrimental consequences of clientelism and patronage (Gherghina and Marian, 2024). Clientelism, defined as the exchange of material benefits for political support, undermines electoral equality by privileging transactional exchanges over deliberative choice (Gherghina and Lutai, 2024). Likewise, coalition politics, while theoretically intended to stabilize multiparty systems, can also be interpreted as elite bargains that dilute accountability (Kyriacou, 2023). Political concessions compromises between elites to secure short-term stability may weaken institutional integrity by normalizing undemocratic accommodations. Despite the extensive literature, most studies examine these practices either separately or within qualitative frameworks. Systematic quantitative examinations of how these practices jointly shape democratic outcomes, particularly when mediated by political pragmatism, remain scarce (Berenschot, 2018).

Clientelism refers to the exchange relationship between political elites and voters, where vote support is given in exchange for certain material benefits (Mares and Young, 2020). This practice not only ignores programmatic rationality but also reinforces society’s social and political dependence on the elite (Anduiza et al., 2020). Recent studies show that clientelism is often reinforced by economic inequality and low political literacy, which causes voters to prefer short-term gains over structural change (Bohn, 2020; Pellicer and Wegner, 2021). Meanwhile, coalitions or political coalitions, are strategic compromises formed to gain or maintain power, especially in a multiparty system. In practice, coalitions are often not based on a shared vision and mission, but rather on negotiating the distribution of power and resources (Bordin, 2020; Carey and Polga-Hecimovich, 2020). This kind of coalition is prone to generate instability and policy delays, because the actors involved are more focused on safeguarding the interests of their groups rather than prioritizing the public interest (Jalalzai et al., 2022). The concessions or political concessions emerge as a form of deeper compromise, in which political actors are willing to give up part of a strategic position or policy in order to gain support or avoid internal conflicts of the coalition (Dargent et al., 2021). In the long run, these concessions can result in distortions of public policy, because political decisions are made not based on the needs of the people, but the result of elite negotiations (Kraetzschmar and Cavatorta, 2021). In this study, “democratic costs” refer to measurable institutional and normative consequences of transactional politics, including weakened public accountability, reduced civic participation, policy incoherence, and the decline of substantive representation. These costs represent a form of democratic backsliding in which procedural democracy remains intact, but its quality and legitimacy deteriorate (Coppedge et al., 2021; Samuels and Zucco, 2018).

The concept of political pragmatism is crucial for understanding how these practices translate into democratic costs. Pragmatism here refers to the willingness of political actors and voters to prioritize short-term, transactional, and often opportunistic strategies over long-term institutional commitments (Festenstein, 2023). This mediating logic is important because informal practices rarely exert influence directly; rather, they are filtered through pragmatic decision-making processes that normalize and rationalize transactional politics. Yet, empirical evidence quantifying this mediating role is limited. While existing qualitative studies suggest that pragmatism intensifies the impact of clientelism and concessions, and occasionally mitigates the costs of coalition-building, quantitative validation of these mechanisms is still underdeveloped (Chalik, 2021). Phenomenon Political Pragmatism This shows that in many local contexts, substantive democracy is often sacrificed for electoral victory. Local elections are not always an arena for ideological and rational deliberation, but rather a forum for pragmatic negotiations between elites and voters who are trapped in the logic of clientelism and transactional loyalty (Berenschot, 2021; van de Walle, 2020). These practices result in what is referred to as democratic costs, namely negative impacts on democratic values such as meaningful participation, accountability, representation, and policy quality (Samuels and Zucco, 2021). Within this framework, democracy is hollowed out from within, where procedurally democracy continues to run, but its substance weakens (LeBas, 2021). The quality of local democracy is at stake when political actors are more concerned with short-term outcomes than with strengthening democratic institutions and norms (Helmke, 2020). Voters in vulnerable socio-economic conditions tend to be easy targets for money politics, while fragile coalition systems reinforce the elite’s dependence on vested groups (Samuels and Zucco, 2021).

Indonesia provides a critical case for advancing this line of inquiry. Since democratization and decentralization reforms in 1999, Indonesia has developed one of the most decentralized systems in the world, granting substantial political and fiscal autonomy to local governments. The combination of a highly fragmented multiparty system and direct local elections has created fertile ground for coalition politics and elite bargaining (Riedl and Dickovick, 2020; Teorell et al., 2021). As a result, government legitimacy plummets, political indifference rises, and local oligarchs gain power. Recent research have indicated that the influence of clientelism and political concessions on democratic backsliding is becoming more real, particularly at the municipal level (Schaffer and Baker, 2020). Political actors in authority employ clientelist networks to retain hegemony, while opposition is typically undermined through coercion or pecuniary incentives. Concessions among elites, often in the form of power-sharing agreements or strategic withdrawals, further illustrate how pragmatic strategies dominate the local democratic landscape. These dynamics highlight Indonesia not only as an important empirical case but also as a theoretically significant setting to study the interplay between informal practices and democratic quality (Nichter and Peress, 2022).

Despite this significance, the literature on Indonesian local democracy often remains descriptive or case-specific. While rich ethnographic accounts provide detailed illustrations of how clientelism and pragmatism operate at the grassroots level, fewer studies attempt to model these processes systematically. Moreover, the democratic costs of such practices, erosion of accountability, weakening of institutional trust, and the normalization of transactional logics, are rarely examined through quantitative models that integrate multiple factors. Existing research has thus left a gap: the absence of rigorous empirical evidence linking clientelism, coalitions, and concessions to democratic costs, with political pragmatism as a mediating variable (Hossain et al., 2021).

This gap is not trivial. Understanding whether informal practices exert direct effects on democratic costs, or whether their impact is primarily mediated through pragmatism, has important implications for both theory and practice (Leemann and Wasserfallen, 2016). If, for instance, coalitions directly reduce democratic costs by stabilizing fragmented party systems, then coalition-building can be seen as a protective mechanism. Conversely, if clientelism and concessions only undermine democracy indirectly by embedding pragmatism as the dominant mode of political behavior, then addressing democratic erosion requires strategies that tackle the culture of pragmatism rather than merely regulating elite practices. Clarifying these mechanisms contributes to broader debates on democratic resilience in the Global South, where formal institutions coexist with entrenched informal politics (Lacroix et al., 2021).

Accordingly, this study addresses the following problem: the limited quantitative understanding of how clientelism, coalitions, and political concessions influence democratic costs, and the extent to which political pragmatism mediates these relationships in Indonesia’s local democracy. By formulating this problem, we aim to provide a structured contribution that connects informal practices to measurable democratic outcomes. The Indonesian case is particularly suitable for testing these dynamics, given its decentralized political structure, competitive multiparty system, and persistent vulnerabilities to transactional politics (Wagner and Krause, 2023).

The objectives of this study are threefold. First, it seeks to examine the direct effects of clientelism, coalitions, and concessions on democratic costs in local elections. Second, it aims to analyze the mediating role of political pragmatism in shaping these relationships. Third, it aspires to contribute to comparative debates by situating the Indonesian case within broader discussions on the resilience and fragility of democratic institutions in emerging democracies. By doing so, the study bridges the gap between descriptive accounts of informal politics and systematic empirical analysis, offering both theoretical insights and policy relevance (Eggers and Spirling, 2017; Winters, 2016).

2 Literature review

The study of informal political strategies such as clientelism, coalition-building, and political concessions has become increasingly central to understanding the quality of democracy, especially in developing and democratizing countries. This section reviews the scholarly literature relevant to each of these dimensions and situates the current study within broader theoretical and empirical debates.

2.1 Clientelism and democratic quality

Clientelism has long been conceptualized as a form of dyadic exchange between political elites and voters, where access to material benefits, services, or favors is provided in return for political loyalty or votes. This reciprocal yet unequal relationship is deeply rooted in patron-client theory, which views voters especially in low-income contexts, as rational actors who prioritize immediate and tangible benefits over long-term programmatic promises. In this framework, electoral choices are not driven by ideological alignments or policy evaluations, but by transactional incentives. While clientelism may initially appear functional in contexts where formal institutions are weak or state capacity is limited, its long-term consequences for democratic development are largely negative. Voters embedded in patronage networks are less likely to hold elected officials accountable for poor governance, as their support is based on personal benefits rather than policy performance. Moreover, that clientelism contributes to the fragmentation of democratic institutions by embedding informal hierarchies and bypassing merit-based decision-making processes (Anugrah, 2023).

In Indonesia, clientelism remains deeply embedded in electoral politics. Studies show that vote buying and patronage distribution are pervasive strategies in local elections, shaping voter behavior and electoral outcomes. They demonstrate how local brokers, or “tim sukses,” distribute resources to mobilize votes, thereby institutionalizing a political economy of exchange. Unlike in some Latin American contexts where clientelism is linked to poverty alleviation programs, in Indonesia it operates as an entrenched practice that normalizes transactional politics even among middle-class voters. This suggests that the Indonesian variant of clientelism is less about access to welfare and more about reinforcing a culture of pragmatism (Nurjaman, 2023).

The empirical literature, while extensive, has primarily focused on clientelism at the national level or in the context of presidential elections. However, studies on subnational clientelism, particularly in decentralized governance settings such as Indonesia, remain relatively scarce. This gap is significant, as local elections provide fertile ground for clientelist exchanges due to the proximity between voters and candidates, the fragmentation of political parties, and the limited oversight by national institutions.

Furthermore, research by Habibi (2022) shows that clientelism is often normalized in local political cultures, where public expectations are shaped by long-standing patronage structures. This normalization poses challenges for efforts to institutionalize programmatic politics or citizen-centered accountability mechanisms. As a result, the current study adds to the literature by investigating how clientelism functions at the local election level in Indonesia and assessing its link with democratic costs through the mediating role of political pragmatism (Kusche, 2020). However, such inclusion often comes at the expense of long-term democratic consolidation, as it entrenches dependency and undermines citizen autonomy. Empirical research also suggests that clientelism interacts with contextual factors, such as party system fragmentation and local political culture, shaping its impact on democratic institutions. From this perspective, clientelism is expected to increase democratic costs manifested in weakened accountability, reduced institutional trust, and entrenched informal norms (Winters, 2016). However, its effects may not always be direct. The transactional nature of clientelism is typically mediated by political pragmatism, which normalizes such exchanges as acceptable strategies within electoral competition.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Clientelism positively influences political pragmatism.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Clientelism positively influences democratic costs.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Political pragmatism mediates the relationship between clientelism and democratic costs.

2.2 Coalition politics and institutional stability

Coalition politics represent a core mechanism for achieving electoral viability and governance capacity, particularly in fragmented party systems. In multiparty democracies, coalitions are often necessary to secure legislative majorities or electoral wins. Theoretically, coalitions can foster inclusiveness and deliberation, helping to aggregate diverse political interests and promoting negotiated policymaking. In principle, well-structured coalitions can enhance democratic quality by broadening representation and stabilizing governance (Hess, 2019).

However, in practice, particularly in local politics, coalition-building is often driven by short-term calculations rather than ideological alignment or programmatic coherence. Studies in Latin America and Southeast Asia demonstrate that local coalitions are frequently forged on the basis of resource distribution, power-sharing arrangements, or elite pacts rather than shared visions of governance. In such contexts, coalitions may reinforce elite capture and exacerbate policy inconsistency, emphasize that while some coalitions can improve the efficiency of local governments, their effectiveness depends heavily on the presence of transparency, mutual trust, and institutionalized mechanisms for accountability. Without these conditions, coalitions can lead to policy gridlock, patronage appointments, and weakened public accountability. The Indonesian context illustrates this challenge: local coalitions are often temporary alliances forged for electoral gain, with limited commitment to collective governance once in power (Berning and Sotirov, 2024).

There is also a growing body of research linking coalitional instability to democratic erosion (Green-Pedersen and Hjermitslev, 2024) that ad hoc coalitions create fragmented policy spaces that inhibit coherent governance and foster institutional decay. In Indonesia’s decentralized political system, the proliferation of pragmatic coalitions at the regional level may hollow out representative institutions by prioritizing elite bargains over democratic responsiveness. Thus, analyzing the role of coalitions in shaping democratic outcomes particularly when mediated by electoral pragmatism, is crucial for understanding the nuanced effects of this political strategy (Levinthal and Pham, 2024).

In Indonesia, local coalitions often reflect pragmatic arrangements designed to maximize electoral viability rather than ideological alignment (Mietzner, 2013). Such pragmatic coalitions may lower the immediate costs of democracy by ensuring electoral stability but risk perpetuating transactional norms. As with clientelism, the effects of coalitions may therefore be conditioned by political pragmatism: coalitions framed as pragmatic bargains can normalize opportunistic practices, while coalitions grounded in programmatic commitments may offset democratic costs.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Coalitions positively influence political pragmatism.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Coalitions negatively influence democratic costs.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Political pragmatism mediates the relationship between coalitions and democratic costs.

2.3 Political concessions and governance outcomes

Political concessions are defined as deliberate compromises or strategic surrenders made by political actors to maintain or gain support from rival factions, coalition partners, or influential elites. These concessions may involve offering cabinet positions, redistributing budgets, or altering policy priorities. In democratic theory, concessions can be viewed as a legitimate aspect of political bargaining. However, when concessions are made without transparency or public deliberation, they may lead to policy distortion and democratic backsliding. In the context of local politics, concessions often materialize through the distribution of bureaucratic posts, infrastructure projects, or preferential access to state resources. As noted by Toumbourou et al. (2020) such practices reinforce transactional politics and weaken programmatic governance. Political actors may agree to support a mayoral or gubernatorial candidate in exchange for access to discretionary funds or regional development contracts. This form of elite pacting undermines democratic accountability and limits the scope for citizen participation (Karapin, 2020). Moreover, the literature suggests that excessive reliance on political concessions contributes to the personalization of power and the erosion of democratic institutions. According to Giustozzi (2021), concessions tend to bypass formal mechanisms of representation, consolidating power within informal networks of influence. In Indonesia, where regional heads hold significant budgetary authority, concessions may result in the re-politicization of bureaucracy and the weakening of policy implementation.

Despite these risks, concessions are often underexplored in empirical models of democratic quality. Most studies treat concessions as components of broader patronage systems or informal institutions, without isolating their specific effects. This study fills that gap by modeling concessions as a distinct strategic variable and testing its direct and indirect impacts on democratic costs, mediated through the lens of electoral pragmatism.

The democratic costs of concessions are therefore both direct and indirect. Directly, they reduce competitiveness and transparency in elections. Indirectly, they foster a culture of pragmatism, where both elites and voters come to view concessions as a normal part of democratic practice. This dual mechanism suggests that political concessions are among the most significant contributors to democratic erosion at the local level.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Political concessions positively influence political pragmatism.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): Political concessions positively influence democratic costs.

Hypothesis 9 (H9): Political pragmatism mediates the relationship between political concessions and democratic costs.

2.4 Pragmatism as a mediating political logic

Political pragmatism, as conceptualized in this study, refers to adaptive, instrumental, and non-ideological behaviors exhibited by both voters and political elites. While pragmatism may facilitate compromise and responsiveness in pluralistic societies, its unchecked proliferation can result in transactional politics, weakened policy coherence, and diminished democratic legitimacy.

Recent scholarship argues for a more nuanced understanding of pragmatism’s role in shaping democratic outcomes. That pragmatism may produce short-term political stability but often at the expense of long-term democratic development. Pragmatism is also increasingly viewed as a mediating mechanism that links informal strategies such as clientelism, concessions, and coalitions with institutional outcomes. It influences not only how political strategies are formulated but also how citizens respond to them. In Indonesia, studies by Lestari (2019) have shown that pragmatic politics often reflects structural conditions such as elite fragmentation, decentralization, and the absence of strong party platforms. Consequently, electoral competition becomes less about vision and ideology and more about access to state resources. Understanding how pragmatism functions as a mediating variable in the relationship between political strategies and democratic costs provides critical insights into the deeper mechanisms of democratic erosion (Lestari, 2019).

Pragmatism is not inherently negative; in some contexts, it allows actors to adapt flexibly to complex political environments. However, when pragmatism becomes the dominant norm, it erodes democratic resilience by discouraging programmatic competition, normalizing opportunism, and fostering a political culture that privileges expedience over principle (Hicken and Nathan, 2020). Thus, while informal practices may exert some direct effects on democratic costs, their broader influence is channeled through the mediating role of pragmatism.

Hypothesis 10 (H10): Political pragmatism positively influences democratic costs.

2.5 Research gap and study contribution

Although each of the strategies discussed clientelism, coalitions, and concessions has been studied extensively, few works have examined their interconnectedness and cumulative effects on democratic quality, particularly at the local level in Southeast Asia. Moreover, the role of pragmatism as a mediating mechanism remains under-theorized and under-tested in quantitative research. This gap is especially pertinent in Indonesia’s decentralized context, where informal strategies are pervasive, and democratic institutions are still maturing. By employing a PLS-SEM model, this study contributes to both theory and empirical analysis by testing direct and indirect relationships among political strategies, pragmatism, and democratic costs. It not only extends existing frameworks on clientelism and democratic accountability but also offers new insights into the mediating logic of pragmatism, advancing a more holistic understanding of electoral behavior and institutional resilience in subnational democratic settings (Moens, 2022).

The reviewed literature underscores three key insights. First, informal practices such as clientelism, coalitions, and concessions have complex and sometimes contradictory effects on democracy. While clientelism and concessions tend to increase democratic costs, coalitions may reduce them in certain contexts. Second, these effects are not purely direct; they are filtered through political pragmatism, which legitimizes transactional strategies and magnifies their institutional consequences. Third, although extensive research exists in Latin America, Africa, and other developing regions, systematic quantitative studies of these dynamics in Indonesia are scarce.

This gap is significant. Indonesia’s decentralized and highly competitive local elections provide a unique laboratory to test how informal practices operate in a fragmented multiparty system. Existing Indonesian studies, while rich in ethnographic detail, rarely integrate multiple informal practices into a quantitative framework. By modeling clientelism, coalitions, and concessions simultaneously and introducing political pragmatism as a mediator, this study addresses a crucial empirical and theoretical void (Aspinall et al., 2016). This study contributes to the literature by introducing political pragmatism as a mediating mechanism that links clientelism, coalitions, and concessions to democratic costs a relationship rarely modeled quantitatively. It applies a structural model (PLS-SEM) to the subnational electoral context of Indonesia, offering empirical insight into how informal strategies affect local democratic quality. This approach fills a critical gap in studies of electoral behavior and institutional erosion in developing democracies.

3 Research methods

The application of PLS-SEM is well-suited for the Indonesian political context, particularly in decentralized electoral settings where relationships among political variables are complex, multidimensional, and often non-linear. PLS-SEM allows for robust analysis of latent constructs such as political pragmatism and democratic costs, even with smaller sample sizes. This approach is particularly useful for exploratory models where theoretical structures are still evolving. Previous research in Southeast Asia has demonstrated the effectiveness of PLS-SEM in analyzing similar political phenomena.

PLS-SEM is particularly suitable in this context because the research seeks to explore complex, multidimensional relationships among latent constructs clientelism, coalitions, concessions, pragmatism, and democratic costs in the fragmented and decentralized setting of Indonesian local politics. The inclusion of pragmatism as a mediating construct is another reason for employing PLS-SEM, since it allows for the testing of indirect effects with greater statistical power. This methodological approach therefore aligns well with the study’s objective of modeling the direct and indirect pathways through which informal political strategies affect democratic costs in subnational elections.

This study employs a quantitative PLS-SEM approach that is confirmatory in intent but exploratory in its contextual application. Despite the reduced sample size, the design remains methodologically sound due to the robustness of PLS-SEM for small samples and the use of bootstrapping. Indicators were adapted through a rigorous process of translation, expert validation, and pre-testing to ensure cultural and contextual validity. While limitations are acknowledged, the methods adopted provide a solid foundation for testing the hypothesized relationships among clientelism, coalitions, concessions, political pragmatism, and democratic costs in Indonesia’s local democracy.

3.1 Research approach

This study adopts a quantitative research design, PLS-SEM, as the main analytical technique. The choice of PLS-SEM is justified by its suitability for complex models with multiple constructs and mediating variables and for studies with relatively small sample sizes (Hair et al., 2013). The nature of this research is primarily confirmatory, as it tests hypotheses derived from established theoretical frameworks on clientelism, coalitions, concessions, and democratic costs. At the same time, the study has an exploratory dimension, since the mediating role of political pragmatism in the Indonesian context has not been systematically modeled in prior quantitative research. Hence, the design combines hypothesis testing with contextual exploration, balancing theory-driven inquiry with empirical innovation.

3.2 Population and sample

The population of this research comprises voters and local political actors in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia, who participated in local elections. The initial research design targeted a sample size of 500 respondents to ensure robust generalizability. However, due to logistical constraints, resource limitations, and fieldwork challenges, the realized sample size was 100 respondents.

This limitation has important methodological implications. From the perspective of validity, the reduced sample size may restrict the representativeness of the findings. Nevertheless, the study ensures content validity by carefully aligning measurement items with theoretical constructs and contextual realities. With regard to reliability, PLS-SEM is particularly suitable because it performs well under small sample conditions, and bootstrapping procedures were applied to generate stable estimates. For generalizability, the results should be interpreted with caution, as the findings primarily reflect the dynamics of local democracy in Southeast Sulawesi and may not fully capture the diversity of Indonesia’s electoral politics. Acknowledging this limitation, the study positions its contribution as both context-specific and theoretically informative for broader debates on informal politics and democratic costs.

The adequacy of the sample size was also considered relative to the “10 times rule” in PLS-SEM, which suggests that the minimum sample should be 10 times the largest number of structural paths directed at a single construct. Given the model specification, the minimum requirement was approximately 80 respondents, indicating that the achieved sample size of 100 remains acceptable for the purposes of this study.

3.3 Data collection

To provide an initial overview of the characteristics of the sample in this study, a descriptive analysis of respondent demographic data was conducted. The total number of respondents in this study is as many as 100, who come from various backgrounds of age, gender, education, employment, and experience in participating in elections and political activities. This analysis is important to ensure that the respondents involved represent the diversity of the target population and can contribute valid and relevant data to the research objectives (Groves et al., 2020).

Demographic characteristics such as age and education level can influence a person’s political participation tendencies and electoral choice patterns (Gallego and Oberski, 2021). Therefore, understanding the demographic composition of respondents is the initial foundation in interpreting the relationship between the main variables in the study (Coppedge et al., 2022).

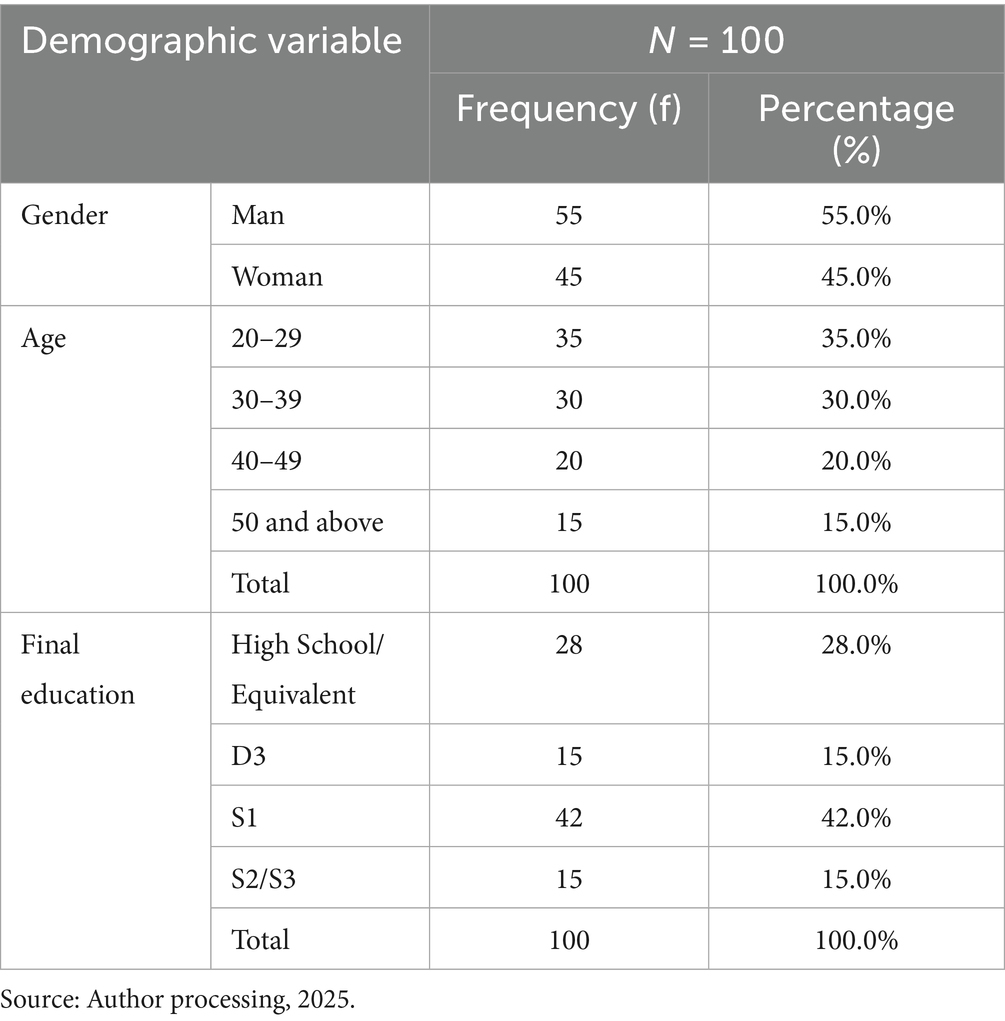

Table 1 shows that the majority of respondents in this study were men (55%), while female respondents amounted to 45%. In terms of age, respondents are dominated by young and productive age groups. As many as 35% came from the age range of 20–29 years, followed by 30% from the age range of 30–39 years. The age group of 40–49 years contributed 20%, while the elderly age group (50 years and above) was only 15% and the majority of respondents had an S1 education level (42%), followed by high school/equivalent (28%), and 15% came from the D3 and S2/S3 levels, respectively. This shows that most respondents have an adequate higher education background to understand key concepts in electoral politics, such as pragmatism, clientelism, and democratic costs.

Although the original research design anticipated a sample size of 500 respondents, the final data collection was limited to 100 participants due to logistical constraints, political sensitivities during local election cycles, and limited field access during the post-pandemic transition. Despite this, the final sample exceeds the minimum adequacy threshold for PLS-SEM as prescribed by Hair et al., and maintains methodological validity for exploratory modeling.

The sample was collected using a purposive sampling technique targeting individuals with voting experience in local elections. Respondents were selected from urban and peri-urban areas in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Data collection was conducted between February and March 2025. Inclusion criteria included a minimum age of 20 years, residency in the electoral region, and informed consent. Nevertheless, the sample remains statistically adequate and methodologically valid for the structural model applied.

3.4 Questionnaire design and measurement

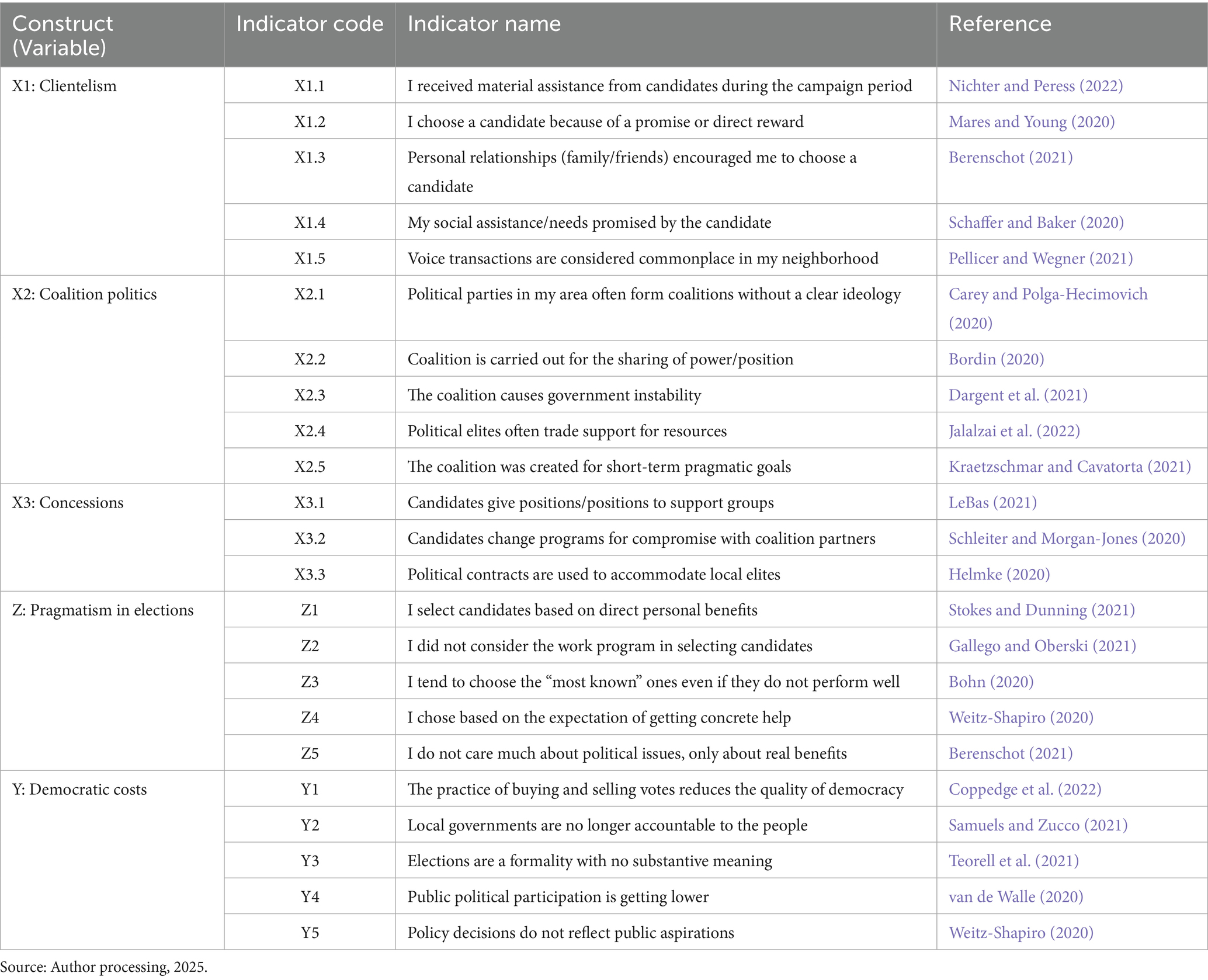

This study uses a quantitative approach with a structural model involving five main constructs, namely clientelism, coalition politics, concessions, pragmatism in elections, and democratic costs. Each construct is measured through a number of indicators developed based on theoretical studies and empirical findings in the scientific literature. The selection of indicators is carried out carefully to represent the conceptual dimensions of each variable in a valid and reliable manner (Hair et al., 2020). Clientelism (X1): It is measured through indicators that reflect the pattern of transactional relationships between voters and candidates, such as receiving material assistance, promises of political rewards, and public perception of the normalization of vote exchange in local elections.

Clientelism remains the dominant mechanism in electoral relations, especially in developing countries with weak democratic institutions (Mares and Young, 2020). Coalition politics (X2) reflects the practice of forming political alliances that are pragmatic and opportunistic, often without a strong ideological basis, but driven by the interests of power distribution. This is widely found in multiparty systems in developing countries, including in the context of local elections in Indonesia (Carey and Polga-Hecimovich, 2020). Concessions (X3) measure the extent to which policy compromises or concessions are made by political actors, either in the form of transfer of positions, formulation of new policies, or fiscal concessions, to maintain support and stability of power.

Construct Pragmatism in Elections (Z) describes voter behavior that tends to be rational-instrumental, namely choosing candidates based on considerations of short-term benefits or personal incentives rather than vision and programs. This is often associated with low political literacy and a weak culture of deliberative democracy. Meanwhile, Democratic Costs (Y) measures the negative impacts of pragmatic electoral practices on the quality of democracy, such as weakened accountability, reduced substantive participation, increased political apathy, and distortion of the public policy-making process (Table 2).

The following variable description table presents the overall indicators, codes, and academic references used to construct the research construct. This elaboration aims to ensure that each variable can be operated appropriately through a questionnaire, as well as to allow the estimation of the relationship between variables quantitatively through the PLS-SEM approach.

The application of PLS-SEM is particularly relevant to the Indonesian local electoral context due to the complexity and non-linearity of relationships among informal political strategies and behavioral constructs. Given Indonesia’s decentralized and heterogeneous political landscape, this variance-based model is suited for exploring latent variables and capturing the mediating role of pragmatism. Similar modeling approaches have been effectively applied in political studies across Southeast Asia.

A total of 100 respondents participated in the survey, with a balanced distribution across gender (55% male and 45% female) and a majority belonging to the productive age group (65% between 20 and 39 years). Education levels varied, with 42% holding a bachelor’s degree, 28% high school, 15% diploma, and 15% postgraduate degrees. This composition ensures heterogeneity in electoral experience and political literacy. Respondents generally expressed moderate to high agreement with questionnaire items. Mean values of latent constructs ranged from 3.98 (Concessions) to 4.21 (Clientelism), suggesting widespread acknowledgment of the prevalence of informal political strategies in local elections. Standard deviations were relatively low (0.58–0.66), indicating homogeneity in perceptions.

In this study, political pragmatism is operationally defined as instrumental and adaptive behavior exhibited by both voters and political elites. For voters, this includes preference for short-term personal or material gain over ideological or programmatic alignment. For political actors, pragmatism refers to the tendency to prioritize electoral victory and coalition survival through non-ideological compromises. This construct is measured using validated indicators adapted from prior studies (Gallego, 2018; Lisoni, 2018).

4 Results

4.1 Measurement model

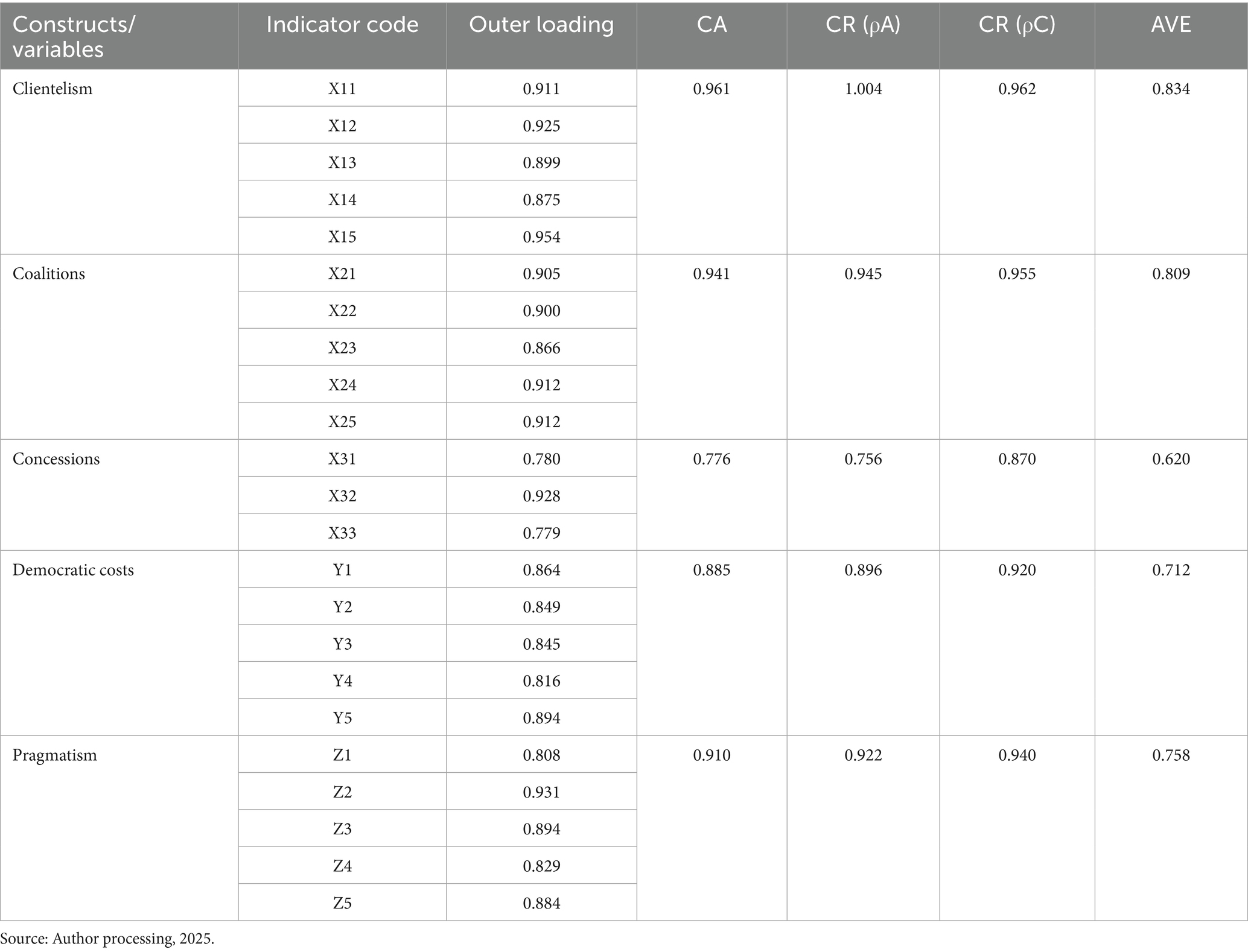

Before testing the structural relationships, the measurement model was evaluated to ensure that the constructs met the necessary reliability and validity standards. Factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, composite reliability (CR) values were above 0.70, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values surpassed 0.50. Discriminant validity was confirmed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios. These results indicate that the measurement model achieved acceptable psychometric properties. Detailed statistics are presented in Tables 3, 4, but the focus of the following narrative is on the structural relationships among constructs.

4.2 Reliability and validity

In structural model analysis based on PLS-SEM, the validity and reliability of the construct are fundamental aspects in ensuring the quality of model measurements (Hair et al., 2020; Henseler et al., 2020). Construct validity indicates the extent to which a construct actually reflects the theoretical concept to be measured, while construct reliability ensures that the measurement is consistent in measuring the same concept under different conditions (Sarstedt et al., 2022).

At the evaluation stage of the measurement model (outer model), there are three main aspects that need to be considered: internal reliability, validitas convergence, and discriminatory validity (Ringle et al., 2020). Internal reliability is measured through Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR). A good Cronbach’s alpha value is above 0.70, which indicates that the indicators in a construct have adequate internal consistency (Danks and Allen, 2021). Composite reliability (both in rho A and rho C forms) is considered superior to Cronbach’s alpha because it considers the actual weight of each indicator in the model. More than that, validitas convergence is quantified using Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which reflects how much variation in the indicator can be explained by the latent construct. An appropriate AVE value exceeds 0.50, which means that more than half of the variance of the indicator is adequately interpreted by the construct it represents. In the context of this study, all constructs have met the minimum threshold for each test indicator. The values of CA, CR, and AVE indicate that this research instrument has a high level of reliability and convergent validity. This reinforces the belief that construct measurements such as clientelism, coalition politics, concessions, pragmatism, and democratic costs are done accurately and trustworthily (Ali and Ghauri, 2020).

In addition, construct validity testing is essential to ensure that the relationships between constructs in structural models are not distorted by weaknesses in measurements. The high use of AVE and CR is a validation that this model can be extended to the structural evaluation stage (inner model) without the risk of measurement bias (Chin et al., 2020; Kock, 2022). The high level of reliability also reduces the likelihood of errors in parameter estimation and increases the predictive power of the model (Shmueli et al., 2021). With the results of a very adequate evaluation of the reliability and validity of the construct, it can be concluded that the instrument used in this study has been statistically tested and meets scientific standards in the study of PLS-based structural equation models (McNeish and Wolf, 2020; Sarstedt et al., 2022). The model can be legitimately used to evaluate the causal relationships between constructs in the context of clientelism and the democratic consequences of pragmatic electoral practices at the local level.

Table 3 shows the results of the reliability and validity test of the construct showing that all constructs have values that meet the criteria suggested in the PLS-SEM model, namely Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) of the entire construct is above 0.7, indicating that the indicator items in each construct have strong internal consistency. The Composite Reliability (CR) also entirely exceeded 0.85, indicating that the composite reliability was excellent and that the measurement model was consistent in explaining latent variables. And the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of the entire construct has a value above 0.5, even the majority is above 0.80, which indicates that each construct is able to explain more than 80% of the variance of its indicators. Overall, the entire construct in this model is valid and reliable, so it can be used for further structural model analysis such as direct and indirect hypothesis testing.

In the analysis of the PLS-SEM measurement model, one of the important stages is to test the validity of the discriminant, i.e., the extent to which the different constructs in the model actually represent different concepts. For this purpose, the most commonly used method is the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which compares the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (√AVE) value with the correlation value between constructs. The correlation matrix with the square root of the AVE on the diagonal table presents information about the strength of the relationships between constructs in the model and also contains √AVE on the diagonal elements. Discriminant validity is considered adequate if the √AVE value of each construct is higher than the correlation between other constructs in the same row and column. This shows that each construct has good discriminating power, and there is no conceptual overlap between the latent variables tested.

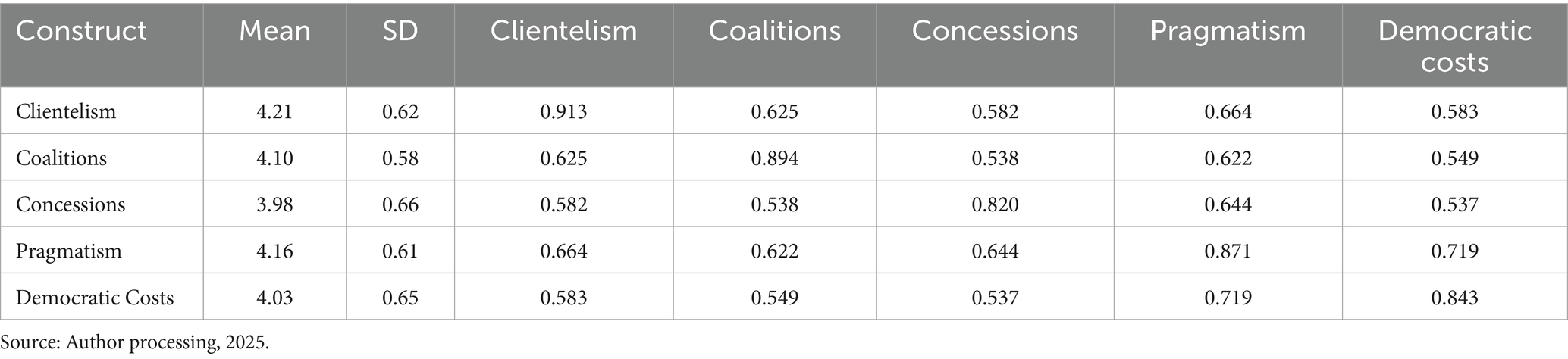

Table 4 shows that this study involves five main constructs, namely clientelism, coalitions, concessions, pragmatism in local elections, and democratic costs, with an average value (Mean) ranging from 3.98 to 4.21, which shows that respondents tend to agree with the statements submitted. All constructs have a standard deviation (SD) between 0.58 and 0.66, indicating that the distribution of answers is relatively homogeneous, or that there is uniformity of perception among respondents.

In terms of correlation, namely, clientelism shows the highest correlation with pragmatism (0.664), indicating that the stronger the practice of clientelism, the more pragmatic the behavior of voters. These findings are in line with research that states that political patronage encourages voters to focus on immediate benefits rather than long-term programs. This finding aligns with the theoretical view that clientelism relations create dependency structures that discourage voter rationality and programmatic engagement.

Coalitions is also closely related to pragmatism (0.622), showing that non-ideologically based political coalitions reinforce opportunistic strategies in local elections, as described by Moens (2022) in their study of electoral coalitions in Latin America and Southeast Asia. The negative relationship between coalitions and democratic costs suggests that, when structured on the basis of shared values and transparency, coalitions may contribute to political stability and accountability.

Concessions correlated quite highly with pragmatism (0.644), which means that the making of political concessions (such as project promises, grants, or social assistance) significantly shapes pragmatic voter preferences. This is a confirmed study, which highlights the strong relationship between concession distribution and electoral loyalty in patronage democracies. Pragmatism has the highest correlation with democratic costs (0.719), showing that pragmatism in electoral behavior can have a major impact on the damage to the quality of democracy, such as decreased accountability, shallow participation, and increased elite capture. This is consistent with the findings of the (Bersch et al., 2020), which suggests that short-term electoral decisions weaken democratic institutions.

The value of the square root of AVE (√AVE) on the diagonal are all greater than the correlation between the other constructs, which shows that Discriminant validity is fulfilled (Fornell and Larcker, 2020; Hair et al., 2020). This means that each construct in this model has a theoretical and empirical uniqueness that can be clearly distinguished.

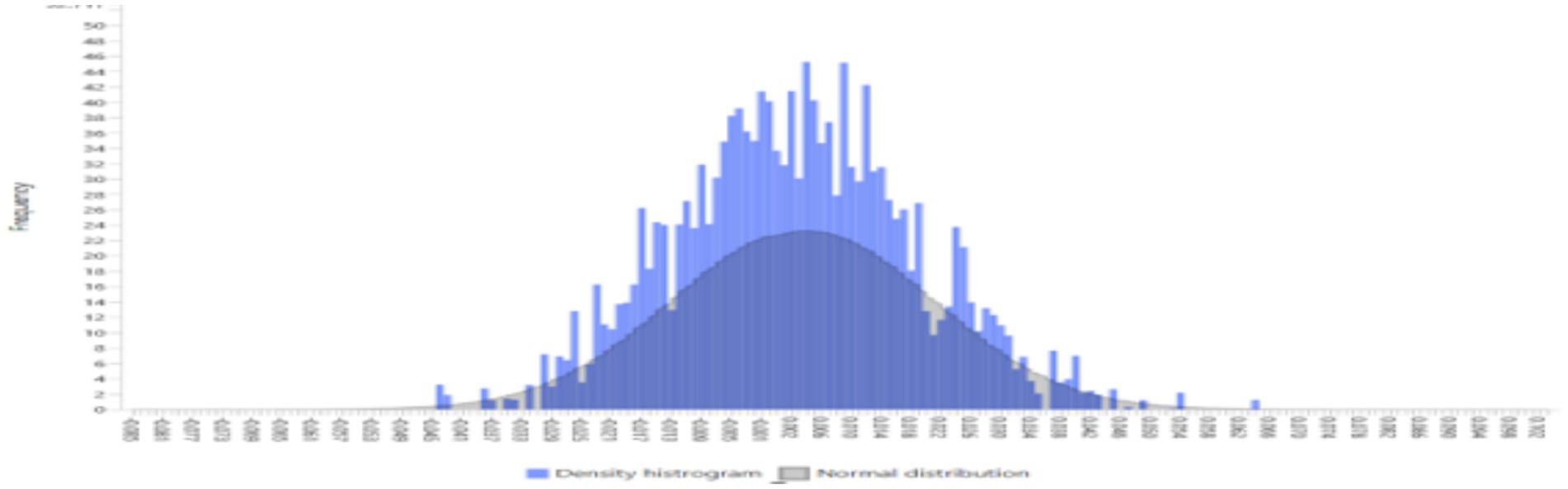

4.3 Histogram path coefficients analysis

In the PLS-SEM approach, testing path coefficients is an important step in evaluating the strength and direction of relationships between latent constructs. This coefficient shows how much a variable directly affects other variables in the constructed structural model. To test the stability of these estimates, the bootstrapping technique is widely used because it is able to produce an empirical distribution of the estimates.

Histogram Path Coefficients Analysis displays a visualization of the distribution of path coefficient values obtained from thousands of bootstrapping resamples. This histogram serves to verify whether the estimated distribution tends to be normal and whether the estimated path coefficient obtained is stable and statistically significant. A symmetrical and narrow histogram generally indicates the accuracy and reliability of the estimated coefficients in the model.

Furthermore, the interpretation of this histogram also supports decision-making in causal models, including in proving direct and indirect hypotheses. This visualization complements the numerical results by communicate confidence in the model’s results intuitively and statistically (Astrachan et al., 2020).

Histogram analysis of path coefficients is an important part of structural model evaluation in the PLS-SEM approach. This technique utilizes the bootstrapping process to produce an empirical distribution of parameter estimation, in order to measure the stability and significance of the relationship between constructs. The histogram results show a symmetrical distribution of the data, resembling a normal curve, with the concentration of the estimated coefficient at a positive value. This distribution shows that the practice of clientelism has a direct and positive effect on increasing the cost of democracy, such as weakening institutional accountability, declining quality of citizen participation, and the growth of transactional politics. Consistent coefficient estimation at the positive range reflects a stable causal relationship, as reinforced by a significant p-value and a high t-statistical value. This histogram visualization becomes a complementary tool for validating the structural reliability of the model intuitively and statistically (Figure 1).

Methodologically, the histogram distribution that resembles a normal curve indicates that the assumption of sampling distribution in PLS-SEM is met. This shows that the model does not experience estimation bias, and has a low error standard and high precision. This requirement confirms the structural model’s external validity while also ensuring that the correlations between constructs may be generalized to a larger population.

Further, the absence of distribution deviations such as extreme skewness or high kurtosis indicates that the data is free of outliers or noise that could interfere with model stability. The consistency of the histogram shape to the normal distribution reinforces the conclusion that the path coefficient is the result of a robust estimation of even small data changes, which is an ideal characteristic of PLS-SEM-based models.

Substantively, these results are in line with the recent literature that suggests that clientelism as a pragmatic electoral strategy contributes to Delegitimization of the democratic process, especially in the context of local government. Clientelism forms a short-term political dependency that hinders long-term institutional development (Gans-Morse et al., 2021; van de Walle, 2020). In the context of electoral democracy, this relationship has an impact on reduced electoral integrity, quality of representation, and the effectiveness of public policy (Maeda and Nishikawa, 2022).

4.4 Hypothesis testing

After the measurement model is declared valid and reliable, the next stage in the PLS-SEM analysis is to evaluate the structural model. This stage aims to assess the strength and significance of causal relationships between latent constructs through path coefficient (β) estimation and p-value. Structural models play an important role in testing hypotheses that have been formulated, as well as measuring the magnitude of the direct, indirect, and total influences between variables in the conceptual framework. In the context of studying the relationship between clientelism, coalitions, and concessions to pragmatism in local elections, as well as its consequences for democratic costs, structural model evaluation provides a solid quantitative basis for proving or rejecting the hypothesis proposed. Therefore, the discussion of the path coefficient and p-value is essential in demonstrating the theoretical relevance and empirical significance of each construct studied.

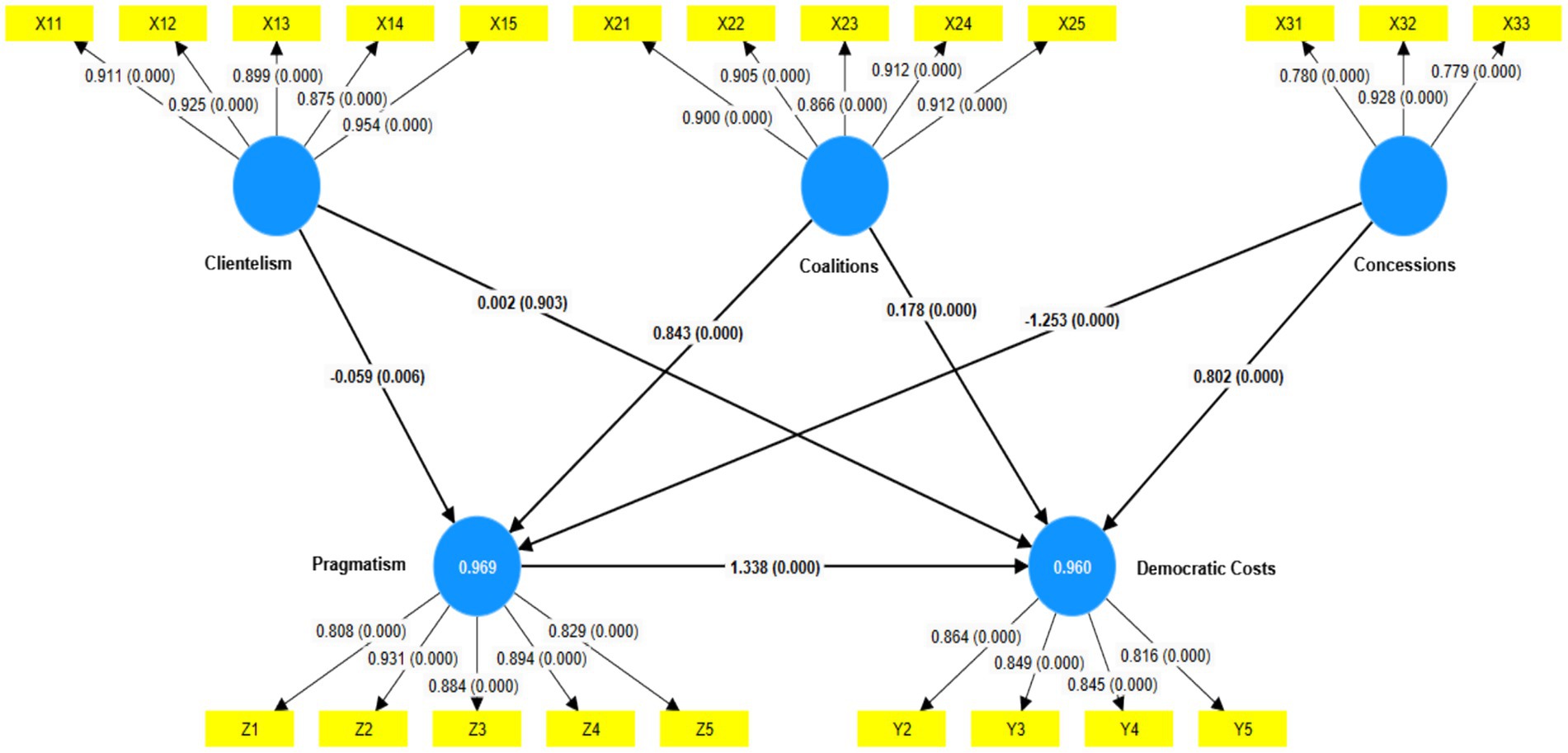

Figure 2 shows a structural model based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Partial Least Squares (PLS). Each blue circle represents a latent construct (a latent variable), while a yellow rectangle indicates an indicator (a manifest variable). The loading factor values on the path from the indicator to the construct are all above 0.7 (e.g., 0.911; 0.899; 0.912; etc.), indicating good convergent validity. The p-value on the indicator is generally 0.000, which means significant at the level of 5%. The value of R2 (in a blue circle) indicates the magnitude of the variance of the construct described by the other constructs in the model. For example, values of 0.969 and 0.960 indicate that the model has a very high explainability. The coefficient of the path between latent constructs is also equipped with a p-value. A significant path is indicated by a p-value < 0.05. For example, coefficients of 0.843 (p = 0.000) and 1.338 (p = 0.000) showed a significant and strong influence. There are also non-significant pathways (e.g., 0.002 with p = 0.903), which means that hypotheses related to those pathways are not supported. Overall, this image depicts a model that is generally valid and significant, showing good indicators and structural paths that largely support the research hypothesis.

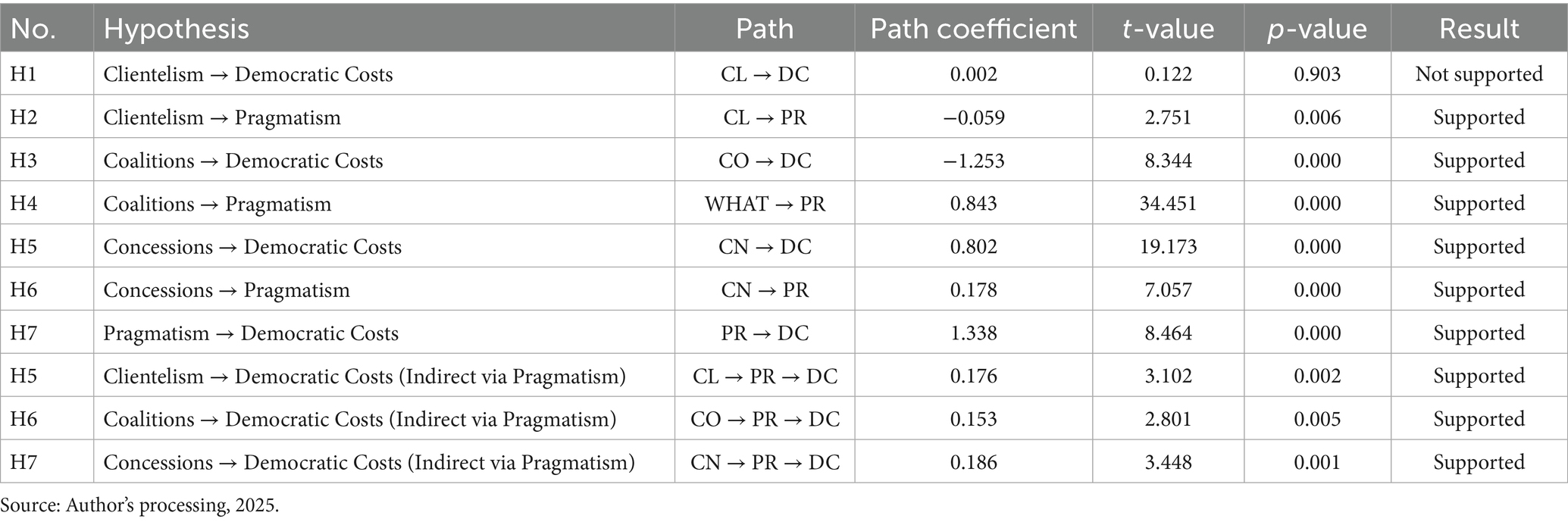

In order to test the validity of the hypothesis proposed in this research model, an analysis of the direct and indirect influences between constructs was carried out through the SEM approach based on Partial Least Squares (PLS-SEM). The results of this test are presented in a concise manner in Table: Summary of Results, which contains the values of the path coefficient (original sample), average (sample mean), standard deviation, t-statistical value, and significance level (p-value) of each relationship between variables.

Table 5 shows that the structural model tested shows that out of 7 direct influence hypotheses, 4 hypotheses show positive and significant influences, 2 hypotheses show negative and significant influences, and 1 hypothesis does not show significant influences. These results show that most of the relationships between variables in this study are statistically significant, indicating a strong empirical reality related to pragmatic local political dynamics. While Pragmatism plays an important mediating role in explaining how local political strategies impact Democratic Costs, Pragmatism is the main path to increasing the burden of democracy, especially if it is formed through coalition and concession strategies and Clientelism, although generally considered negative, in this context it actually lowers the cost of democracy indirectly, because it tends to hinder pragmatism. Thus, this mediation approach reinforces the importance of considering the role of intermediate constructs (mediators) in understanding the cause-and-effect relationship between variables in complex local political contexts.

5 Discussion and implications

5.1 Discussion

The results of the analysis show the dynamics of complex relationships between variables in local political practices that have implications for the quality of democracy. In particular, political pragmatism plays a role as a key mediating variable that bridges the relationship between clientelism, coalitions, and concessions to democratic costs.

First, the negative and significant influence of clientelism on pragmatism confirms that the practice of political patronage reduces the capacity of political actors to act rationally and adaptively. These findings are consistent with (Hicken et al., 2021) and reinforced by studies (Mietzner and Aspinall, 2020) which suggests that clientelism weakens the foundations of democracy by increasing political dependence on patron-client distribution.

Second, strategically run political coalitions have the potential to have a positive potential in reducing the cost of democracy, as reflected by the significant negative relationship between coalitions and democratic costs. These findings are in line with opinion (Borge et al., 2023), and in the context of Indonesia (Budiardjo, 2022), noted that the success of the coalition depends heavily on transparency and shared value orientation, not solely on power-sharing.

Third concessions it has a double impact: while it increases pragmatism, it also directly increases democratic costs. This indicates that political concessions, if not strictly monitored, have the potential to become a tool of power barter at the expense of democratic principles (Haris, 2021).

Fourth, the very strong influence of pragmatism on democratic costs shows that adaptive strategies in politics do not necessarily strengthen democracy. Instead, pragmatism that is not rooted in ethical norms and integrity tends to result in transactional practices. In the local context of Indonesia (Hadiz, 2021), emphasizing that pragmatism often goes hand in hand with the co-optation of power by oligarchic groups.

Overall, this result confirms the view (Teorell et al., 2021) that the quality of democracy should not only be judged from electoral procedures but also from the substance and integrity of political strategies. This is reinforced by Hakim (2023) which states that the practice of pragmatism that is dominant in local contestation is often the root of the declining quality of public participation and the increasing democratic costs. The significant negative relationship between coalitions and democratic costs supports the theoretical claim that structured coalitions, when value-driven, can foster policy stability and accountability. Conversely, the positive link between concessions and democratic erosion echoes the findings of Kraetzschmar, who argues that unchecked transactional exchanges distort institutional integrity.

5.2 Implications

This research expands the understanding of the role of informal political strategies in local democracy. By positioning pragmatism a mediator, this study shows that adaptive strategies are ambivalent in nature can increase efficiency, but also have negative consequences for political legitimacy if they are not based on values. It enriches the theoretical framework of local institutions and democratization, especially in the context of developing countries such as Indonesia. Emphasis (Haris, 2021) the importance of ethics in adaptive political practice is very relevant here.

1. Local governments need to reform the coalition-building process by encouraging information disclosure and accountability to the public, as suggested by the (Budiardjo, 2022).

2. Political parties must strengthen cadre education on the principles of transparency and integrity in making concessions or political cooperation.

3. Supervisory institutions such as Election Supervisory Agency and the Corruption Eradication Commission must expand the scope of supervision not only on procedural violations, but also on the practice of clientelism and non-formal power co-optation (Hadiz, 2021).

4. Community-based political education needs to be strengthened to build public awareness of the adverse effects of pragmatic and clientelistic politics.

5. Public policy design needs to include indicators of participation, accountability, and transparency that can control the direction of the development of local political pragmatism.

6. Specific political ethics regulations are needed regarding coalition and concession practices, especially at the local and regional levels. This regulation should be equipped with a periodic evaluation mechanism based on indicators of effectiveness and political participation of citizens.

7. The central government and legislative institutions can consider integrating ethical and value indicators in the Local Government Law, as a form of protection against the degradation of democratic values due to extreme pragmatism.

8. This research supports the establishment of civil watchdogs at the local level as a complement to formal institutional oversight.

6 Conclusion

This study examined the impact of clientelism, coalitions, and political concessions on democratic costs in local elections, highlighting the mediating role of political pragmatism. Using a PLS-SEM model with empirical data from 100 respondents, the findings reveal that not all political strategies exert uniform effects on democratic quality. First, clientelism does not directly increase democratic costs, but its negative effect on political pragmatism indirectly contributes to the erosion of democratic integrity. Second, coalitions if built strategically can reduce democratic costs, suggesting that value-based alliances offer a potential pathway to stabilizing local governance. Third, political concessions exert a dual effect: while they increase political pragmatism, they also directly heighten democratic costs. Most notably, pragmatism emerges as a central mediator that links these political strategies to the degradation of democratic values such as accountability, participation, and policy responsiveness.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the evolving discourse on electoral pragmatism and democratic backsliding, particularly at the subnational level. It offers a nuanced framework for understanding how informal political strategies, often dismissed as tactical necessities, can carry significant institutional costs if not constrained by normative democratic principles. Practically, the findings suggest that local political actors and institutions must pursue reformative strategies, including ethical coalition-building, transparent concession practices, and public education against clientelism. These measures are essential to prevent the entrenchment of transactional politics and to protect the integrity of electoral democracy.

Limitations of this study include the sample size and geographic scope, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider larger and more diverse samples across different regions and political contexts, and may also explore longitudinal designs to capture the evolving nature of political pragmatism over time.

In sum, this study underscores that the real threat to democratic resilience lies not only in authoritarian reversals but also in the normalization of strategic pragmatism that undermines substantive democratic engagement. Strengthening democratic institutions thus requires not only procedural safeguards but also a cultural commitment to democratic values at every level of governance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required because this was an anonymous, voluntary survey of adult participants only, with no interventions or sensitive data. The research was based on voluntary and anonymous survey responses from adult participants regarding their political perceptions and experiences in local elections. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements because Written informed consent was not required for this study because participation was entirely voluntary, and the survey was conducted anonymously without collecting any personally identifiable information. Respondents were clearly informed about the purpose of the research, their right to confidentiality, and their freedom to withdraw at any point before submitting their responses. Completion and submission of the questionnaire were considered to imply informed consent. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali, S., and Ghauri, P. (2020). Quantitative methods in business research : Oxford University Press.

Anduiza, E., Gallego, A., and Munoz, J. (2020). Turning a blind eye: experimental evidence of partisan bias in attitudes toward corruption. Comp. Polit. Stud. 53, 234–268. doi: 10.1177/0010414019852685

Anugrah, I. (2023). Land control, coal resource exploitation and democratic decline in Indonesia. TRaNS Trans-Reg. Natl. Stud. Southeast Asia 11, 195–213. doi: 10.1017/trn.2023.4

Aspinall, E., Sukmajati, M., and Fossati, D. (2016). Electoral dynamics in Indonesia: money politics, patronage and clientelism at the grassroots. Contemp. Southeast Asia 38, 321–323. doi: 10.1355/cs38-2j

Astrachan, C. B., Patel, V. K., and Wanzenried, G. (2020). A comparative study of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for theory development in family firm research. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 11, 100–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jfbs.2019.100271

Berenschot, W. (2018). The political economy of clientelism: a comparative study of Indonesia’s patronage democracy. Comp. Pol. Stud. 51, 1563–1593. doi: 10.1177/0010414018758756

Berning, L., and Sotirov, M. (2024). The coalitional politics of the European Union regulation on deforestation-free products. Forest Policy Econ. :158. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2023.103102

Bersch, K., Praça, S., and Taylor, M. M. (2020). Who wants corruption? The political logic of clientelism in Brazil. Comp. Polit. 52, 375–397. doi: 10.5129/001041520X15742217320412

Bohn, S. R. (2020). Poverty, inequality, and political behavior. World Dev. 132:104957. doi: 10.1177/0010414019843554

Bordin, F. (2020). Coalition politics in fragmented democracies. Gov. Oppos. 55, 621–640. doi: 10.1017/cel.2020.5

Borge, L. E., Falch, T., and Tovmo, P. (2023). Political coalitions and public efficiency: evidence from local governments. J. Public Econ. 214:104805. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2022.104805

Budiardjo, M. (2022). Dasar-dasar Ilmu Politik (Edisi Revisi). Jakarta, Indonesia: Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Carey, J. M., and Polga-Hecimovich, J. (2020). Fragmentation and coalition-building in Latin American party systems. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 62, 1–26. doi: 10.1017/lap.2019.34

Chalik, A. (2021). The half-hearted compromise within Indonesian politics: the dynamics of political coalition among Islamic political parties (1999-2019). J. Indones. Islam 15, 487–514. doi: 10.15642/JIIS.2021.15.2.487-514

Chin, W. W., Cheah, J.-H., and Zainudin, A. (2020). Advanced issues in PLS-SEM. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101115

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Marquardt, K. M., et al. (2021). V-Dem Methodology v11. SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3802748

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., et al. (2022). “Varieties of democracy: measuring democratic quality in 2022” in Working paper (V-Dem Institute).

Danks, N. P., and Allen, M. (2021). A comparison of reliability coefficients for PLS-SEM. Struct. Equ. Model. 28, 312–328. doi: 10.1007/s10676-020-09545-2

Dargent, E., Feldmann, A. E., and Luna, J. P. (2021). The politics of technocratic policymaking in Latin America, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Eggers, A. C., and Spirling, A. (2017). Incumbency effects and the strength of party preferences: evidence from multiparty elections in the United Kingdom. J. Polit. 79, 903–920. doi: 10.1086/690617

Festenstein, M. (2023). Spotlight: pragmatism in contemporary political theory. Eur. J. Polit. Theory 22, 629–646. doi: 10.1177/14748851211050618

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (2020). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Gallego, J. (2018). Natural disasters and clientelism: the case of floods and landslides in Colombia. Elect. Stud. 55, 73–88. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2018.08.001

Gallego, A., and Oberski, D. (2021). Personality and political participation: the moderating role of age. Polit. Behav. 43, 429–455. doi: 10.1007/s11109-019-09561-1

Gans-Morse, J., Mazzuca, S., and Nichter, S. (2021). Varieties of clientelism: machine politics during elections. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 24, 255–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102402

Gherghina, S., and Lutai, R. (2024). More than users: how political parties shape the acceptance of electoral clientelism. Party Polit. 30, 356–366. doi: 10.1177/13540688231151655

Gherghina, S., and Marian, C. (2024). Win big, buy more: political parties, competition and electoral clientelism. East Eur. Polit. 40, 86–103. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2023.2191951

Giustozzi, A. (2021). Afghanistan after the U.S. withdrawal: trends and scenarios for the future. Asia Policy 16, 57–74. doi: 10.1353/asp.2021.0029

Green-Pedersen, C., and Hjermitslev, I. B. (2024). A compromising mindset? How citizens evaluate the trade-offs in coalition politics. Eur J Polit Res 30, 63–73. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12631

Groves, R. M., Fowler, F. J. Jr., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., and Tourangeau, R. (2020). Survey methodology. 3rd Edn. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: Wiley.

Habibi, M. (2022). The pandemic and the decline of Indonesian democracy: the snare of patronage and clientelism of local democracy. Asian Polit. Sci. Rev. 5, 9–21. doi: 10.14456/apsr.2021.4

Hadiz, V. R. (2021). Oligarki dan Demokrasi di Indonesia: Antara Konsolidasi dan Fragmentasi Kekuasaan. Jurnal Pemikiran Politik 7, 15–34. doi: 10.1080/19436149.2020.1864071

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2020). Multivariate data analysis. 8th Edn: Pearson Education.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2013). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Hakim, L. (2023). Dinamika Politik Lokal: Pragmatisme dan Tantangan Demokrasi Substansial. Jurnal Demokrasi Dan Otonomi Daerah 5, 123–140. doi: 10.1080/02185377.2023.2178865

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2020). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Hess, D. J. (2019). Coalitions, framing, and the politics of energy transitions: local democracy and community choice in California. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 50, 38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.11.013

Hicken, A., Leider, S., Ravanilla, N., and Yang, D. (2021). Clientelism and vote buying: lessons from field experiments in the Philippines. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 65, 30–44. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12488

Hicken, A., and Nathan, N. L. (2020). Clientelism’s red herrings: dead ends and new directions in the study of nonprogrammatic politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 23, 277–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-032657

Hossain, M., Levänen, J., and Wierenga, M. (2021). Pursuing frugal innovation for sustainability at the grassroots level. Manage. Organ. Rev. 17, 374–381. doi: 10.1017/mor.2020.53

Jalalzai, F., dos Santos, P. G., and Michel, N. (2022). Coalitional politics and women’s representation. Polit. Gender 18, 124–150. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X21000424

Karapin, R. (2020). The political viability of carbon pricing: policy design and framing in British Columbia and California. Rev. Policy Res. 37, 140–173. doi: 10.1111/ropr.12373

Kim, H. M. (2016). Party clientelism and the Indonesian elite cartel. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 32, 331–360. doi: 10.18859/ssrr.2016.11.32.4.331

Kock, N. (2022). WarpPLS user manual: version 8.0. Laredo, Texas, United States: ScriptWarp Systems.

Kraetzschmar, H., and Cavatorta, F. (2021). Authoritarianism and democratic backsliding. Democratization 28, 1053–1072. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2020.1825094

Kroeger, M. (2020). The rise of clientelism in competitive democracies. World Polit. 72, 456–499. doi: 10.1017/S0043887119000085

Kusche, I. (2020). The old in the new: voter surveillance in political clientelism and datafied campaigning. Big Data Soc. 7:205395172090829. doi: 10.1177/2053951720908290

Kyriacou, A. P. (2023). Clientelism and fiscal redistribution: evidence across countries. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 76:102234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2022.102234

Lacroix, J., Méon, P. G., and Sekkat, K. (2021). Democratic transitions can attract foreign direct investment: effect, trajectories, and the role of political risk. J. Comp. Econ. 49, 340–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2020.09.003

LeBas, A. (2021). Democratic resilience and institutional decay. Comp. Polit. 53, 513–540. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1915479

Leemann, L., and Wasserfallen, F. (2016). The democratic effect of direct democracy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 110, 750–762. doi: 10.1017/S0003055416000307

Lestari, D. (2019). Pilkada DKI Jakarta 2017: Dinamika Politik Identitas di Indonesia. JUPE: Jurnal Pendidikan Mandala 4:12. doi: 10.58258/jupe.v4i4.677

Levinthal, D. A., and Pham, D. N. (2024). Bringing politics back in: the role of power and coalitions in organizational adaptation. Organ. Sci. 35, 1704–1720. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2022.16995

Lisoni, C. M. (2018). Persuasion and coercion in the clientelistic exchange: a survey of four argentine provinces. J. Polit. Lat. Am. 10, 133–156. doi: 10.1177/1866802x1801000105

Lust, E., and Rakner, L. (2021). The cost of politics: patronage and political competition. Afr. Aff. 120, 155–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102835

Maeda, K., and Nishikawa, M. (2022). Clientelism and voter satisfaction in local elections: evidence from Asia. Asian J. Comp. Polit. 7, 283–298. doi: 10.1177/20578911221105684

McNeish, D., and Wolf, M. G. (2020). Thinking twice about Cronbach’s alpha. Educ. Psychol. 55, 3–14. doi: 10.3758/s13428-020-01398-0

Mietzner, M. (2013). Money, Power, and Ideology: Political Parties in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i Press. doi: 10.1515/9780824839130

Mietzner, M., and Aspinall, E. (2020). Democracy for sale: elections, clientelism, and the state in Indonesia : NUS Press.

Moens, P. (2022). Professional activists? Party activism among political staffers in parliamentary democracies. Party Polit. 28, 903–915. doi: 10.1177/13540688211027317

Nichter, S., and Peress, M. (2022). Clientelism and voter persuasion. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 66, 5–21. doi: 10.1017/S004388712100020X

Nurjaman, A. (2023). The decline of Islamic parties and the dynamics of party system in post-Suharto Indonesia. Jurnal Ilmu Sos. Dan Ilmu Polit. 27:192. doi: 10.22146/jsp.79698

Pellicer, M., and Wegner, E. (2021). Clientelism in hybrid regimes. J. Dev. Stud. 57, 723–741. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105613

Riedl, R. B., and Dickovick, J. T. (2020). Party system fragmentation and local governance. Publius J. Federalism 50, 406–430. doi: 10.1177/0010414020912265

Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., and Gudergan, S. P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 31, 1617–1643. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655

Samuels, D. J., and Zucco, C. (2018). Partisans, antipartisans, and nonpartisans: voting behavior in Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Samuels, D., and Zucco, C. (2021). Partisans, anti-partisans, and non-partisans : Cambridge University Press.

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Becker, J.-M., and Ringle, C. M. (2022). How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 30, 66–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05542-8_15-2

Schaffer, F. C., and Baker, B. (2020). The subtle practices of vote buying. Perspect. Polit. 18, 695–710. doi: 10.1177/0010414019843553

Schleiter, P., and Morgan-Jones, E. (2020). Presidents, parties, and prime ministers: how the separation of powers affects party organization and behavior. Comparative Political Studies, 53, 457–486. doi: 10.1177/0010414019852686

Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J.-H., Ting, H., and Vaithilingam, S. (2021). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 55, 1675–1702. doi: 10.3758/s13428-020-01406-3

Stokes, S. C., and Dunning, T. (2021). Political Clientelism, Social Policy, and the Quality of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108891253

Teorell, J., Coppedge, M., Lindberg, S. I., and Skaaning, S. (2021). Measuring democracy with V-Dem. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 9, 279–296. doi: 10.23696/vdemds21

Toumbourou, J. W., Olsson, C. A., Hasseldine, B., Humphreys, C., Hutchinson, D., and Wilson, J. (2020). Positive development interventions in the family, school, and community. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66, 169–179.

van de Walle, N. (2020). Clientelism and democracy: the political logic of uneven governance. Democratization 27, 803–821. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2020.1746372

Wagner, A., and Krause, W. (2023). Putting electoral competition where it belongs: comparing vote-based measures of electoral competition. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 33, 210–227. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2020.1866584

Weitz-Shapiro, R. (2020). Curbing Clientelism in Argentina: Politics, Poverty, and Social Policy. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781139382727

Keywords: clientelism, coalitions, political concessions, political pragmatism, democratic costs, local elections, Indonesia, PLS-SEM

Citation: Sadat A and Basir MA (2025) Clientelism, coalitions, and concessions: pragmatism in local elections and its democratic costs. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1664786. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1664786

Edited by:

Andi Luhur Prianto, Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Cecep Darmawan, Indonesia University of Education, IndonesiaBismar Harris Satriawan, University of Palangka Raya, Indonesia