- City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

Introduction: A significant amount of effort and attention has been provided to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) strategy. Frequently, the existing analyses focus on the political or economic implications of China’s engagement with its BRI partners. Only recently have these state-centric analyses broadened their focus to include the roles played by subnational actors. However, even though the analytical focus of research works on China’s BRI strategy has expanded, the thematic foci on political/economic relations remains dominant. This study attempts to fill a gap in the literature by exploring social perceptions of Chinese subnational relations.

Methods: Combining interviews and an original survey, this study represents an initial foray into understanding Chinese perceptions of subnational relations with countries on and off the BRI.

Results: The findings suggest that there is a difference between how such relations are perceived, depending on the normative alignment provided by the BRI. They also indicate that shared economic interests were the most important aspect in creating a subnational partnership.

Discussion: By discussing the findings in the context of China’s strategy toward its Asian neighbors, this study strives to offer an initial evaluation of the impact of the BRI on China’s subnational relations with the neighboring countries.

“Friendship, which derives from close contacts between peoples, holds the key to sound state-to-state relations.” (Xi, 2017).

1 Introduction

China has long been a proponent of people-to-people exchanges. During the opening decades of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the country regularly engaged in the types of communication efforts which are now referred to as public diplomacy: sending individuals and groups overseas (normally to countries with whom China normatively and politically aligned) to signal good intentions toward the recipient state and its people. Since the 1970s, the growth in municipal and provincial capacities allowed subnational actors to directly embark on such activities with their overseas counterparts. In the intervening decades, the capacity of both the state and these local actors has grown significantly to the parallel emergence of locally driven relationships, co-opted relationships, and centrally directed relationships.

This situation is comparable with the characteristics of subnational relationships in other countries. While the idea of sister cities as nodes for cooperative exchanges dates back over a millennium (Sister Cities International, 2019), more recently US President Eisenhower’s vision for people-to-people exchanges was the essential element of a peaceful world order that spurred the development of sister cities and sister-province relationships (Fett, 2021, p. 714–742). Eisenhower believed that the “truest path to peace” was for “people to get together and to leap governments--if necessary to evade governments--to work out not one method but thousands of methods by which people can gradually learn a little bit more of each other” (Eisenhower, 1956). In doing so, the US subnational actors began to seek international partnerships with their counterparts worldwide. Although the subnational actors were usually dyads in states normatively aligned with the US during the Cold War, they also forged cooperation with their counterparts in the Soviet Union and China (for instance, Seattle and Tashkent in 1973, and Ohio-Hubei and St. Louis-Nanjing in 1979).

This behavior raises the linked questions regarding the extent to which such subnational linkages are simply an adjunct to national foreign policy and the extent to which they exemplify the emergence of an alternate sphere of international engagement. If the former was true, then it would be expected that the behavior of subnational actors would mirror national policymaking at the local level. Soldatos (1990, p. 34–53) suggested that when non-central governments engaged in foreign activities, their paradiplomatic efforts were an extension of those of the state. Duchacek (1990, p. 1–33) clarified that paradiplomacy parallels, complements, and acts in coordination with national policies. Alternatively, if subnational actors can manage their own affairs, then the situation is closer to what Nye and Keohane (1971) conceived, wherein such actors are on an effectively equal footing with national foreign policymaking. To answer these questions, it is essential to review the behavior of Chinese subnational actors.

Over the last two decades, China has become increasingly active in creating new international institutions (such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank [AIIB and the Belt and Road Initiative [BRI)). These institutions underscore an ongoing effort by the national government to broaden out China’s foreign policy partnerships by drawing upon a range of non-central government actors (such as private sector organizations and subnational governments) into policy processes (Chang et al., 2022, p. 152–171). To realize institutional objectives, these actors extend organizational capacities. However, the inclusion of these actors (considering this study focuses on subnational governments) has its challenges. The primary challenge with which this study engages is that subnational actors are more exposed to grassroot attitudes and policy needs (Yu, 2018, p. 180–195; He, 2019, p. 223–236). Therefore, compared with national actors, they have less scope to downplay or diminish social resistance to unpopular decisions, as their programs directly engage with local communities (Zhuang, 2020, p. 15), even as they remain answerable to the national government. This makes the creation of subnational dyads increasingly problematic, as local governments in China must demonstrate that the partnerships are beneficial to the community. To paraphrase Zhuang, for the creation of subnational dyads, Chinese local governments need to establish a social basis, provide elite backing, and identify “an authentic opening” for the partnership (Zhuang, 2020, p. 15). Li and Yang (2024, p. 354) noted that the local liberalism evinced by Chinese subnational authorities “plays a pivotal role in steering BRI projects towards their envisioned outcomes.”1 Within this literature, the extent of the social basis for engagement and the impact such opinions have on the agency of subnational actors to enact policies remain underexplored.

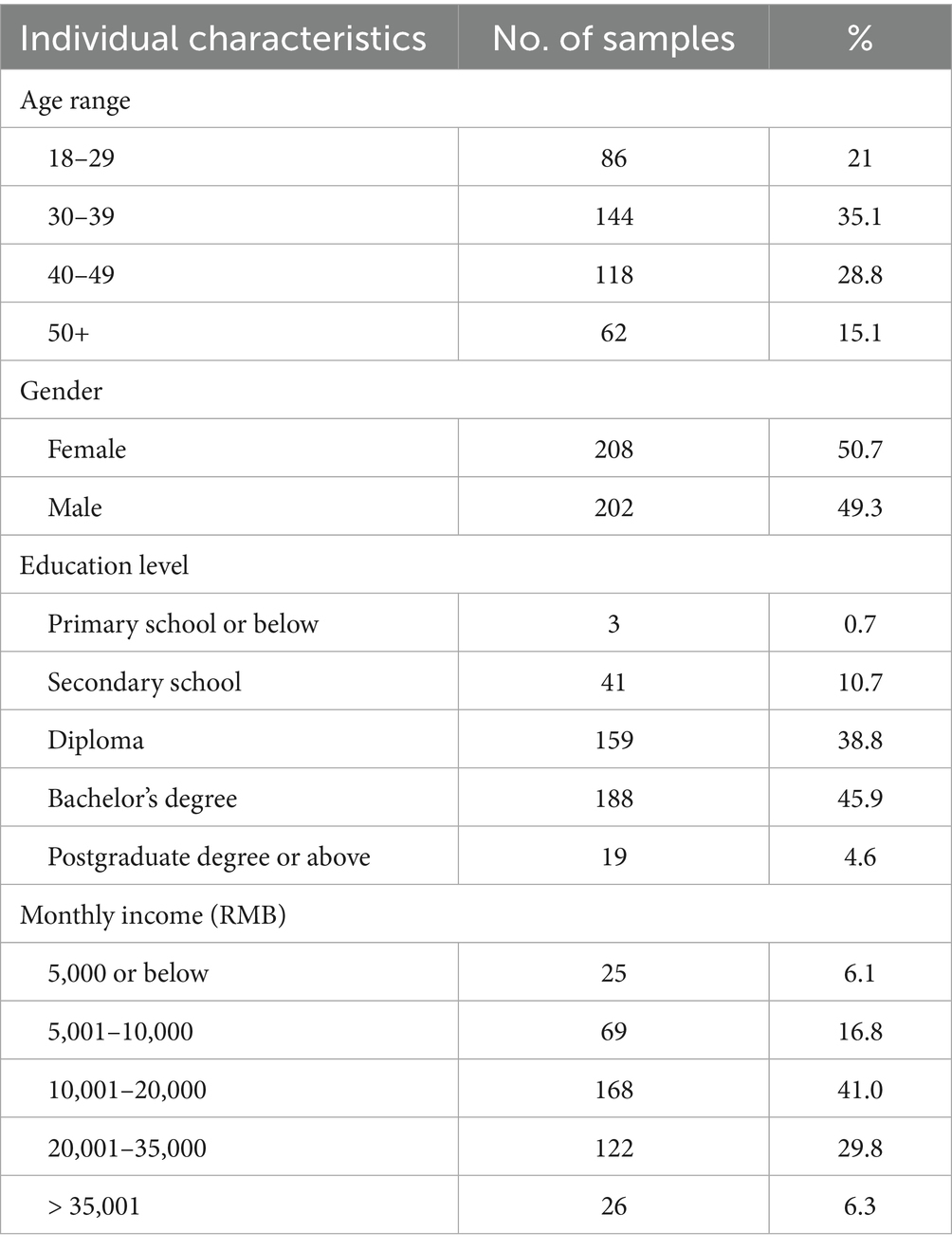

However, if subnational actors play a role in the BRI and if they are more sensitive to grassroots perceptions of the value of overseas partnerships, then the attitudes of the Chinese people need to be more fully understood in order to be factored into any evaluation of the BRI. In particular, it needs to be ascertained to what extent such subnational relations are constrained by institutional structures and public attitudes. To address this issue, we conducted a series of interviews in China and neighboring countries, which were accompanied by an original survey conducted in China in late 2024.2 The interviewees were drawn from public officials, academics, and representatives of the private sector who were involved in the practice or review of these ties; although due to space limitations only a subset has been explicitly drawn upon for this article. The interviews were conducted under Chatham House rules, with an anonymized list provided in the references. The findings from the interviews generally shaped the structure of the survey, which was run in the final quarter of 2024 (n = 410). This mixed-method approach allowed for the interview materials to be combined – for the first-time – with public opinions, which allows this research to address the underexplored issues identified above. The demographic profile of the respondents is included at the end of the paper. Dynata administered the survey and drew upon an existing national panel. The survey included closed- and open-ended questions in a questionnaire format. The responses have been qualitatively used in this analysis. Although the survey was small, it allowed for preliminary observations to be made of local attitudes toward subnational partnerships on and off the BRI.

In order to provide an analytical structure between countries that were committed to the BRI and those that were not, three countries (Kyrgyzstan, India, and Japan) that represent a spectrum of BRI engagement were chosen. The China–Kyrgyz case is an example of a BRI member with subnational ties to Chinese partners. In both South and Northeast Asia, India and Japan have rebuffed Chinese overtures to join the BRI; however, both countries have an array of bilateral ties with provincial and municipal actors. India is also a member of the AIIB, which is within the policy ecosystem of the BRI. Although Japan is not an AIIB member, it shares more subnational ties with China than any other state. Hence, these countries provide a spectrum of BRI engagement, ranging from fully committed to policy-adjacent to the outside. Although the Chinese views of these countries and the role of subnational ties need to be benchmarked against those of other regional states, this spectrum provides a backdrop to evaluate the degree of subnational alignment between the BRI and non-BRI states. Within the survey, Chinese respondents were asked about their views on those countries as well as those on the development and administration of subnational activities. Combining these qualitative data with interviews and secondary literature provides a more comprehensive review of China’s subnational partnerships and their role in Chinese foreign policy initiatives.

This study first explores Chinese scholarship on subnational partnerships, which enable this research to conceptualize how such activities are viewed within the Chinese context and provides a theoretical foundation to answer the key questions. Next, it briefly reviews the policy environment that has enabled Chinese subnational actors to develop their capacity for international cooperation, focusing on BRI-related issues. These sections provide a macro-empirical lens for charting the evolution of these ties with respect to the three case studies and the context in which the survey data can be subsequently reviewed. This study concludes by analyzing the key findings and provides an initial attempt at answer the questions raised above.

2 A Chinese school of paradiplomacy

Although Eisenhower was the most prominent framer of subnational relations during the Cold War, toward the end of this period the concept of paradiplomacy (where subnational actors engage in diplomatic or quasi-diplomatic activities) started being more theoretically developed. Duchacek (1986), who coined the term, claims that paradiplomacy is a feature of more federal and decentralized states. Soldatos (1990, p. 34–53) specifically focused on the conduct of external relations by local governments based on their own recognizance without relying on the authorization of central government authorities, wherein these local actors exhibit greater political autonomy. Cornago (2010, p. 11–36) highlighted the parallel characteristics of both local and central actors in this domain, arguing that such parallel actions by local governments may challenge the traditional diplomatic monopoly of the national government. Although global in scope, these theorists frequently drew upon examples from Western cases to ground their arguments, thereby aligning the practice of paradiplomacy with liberal democratic models of government. This bias creates a challenge when applying the terminology to China. Although China is an active player in paradiplomatic endeavors, domestic interpretations and applications of the issue are necessary to understand how, or to what extent, the Chinese case aligns with international perceptions of subnational actors engaging in paradiplomacy.

The development of modern China is characterized by a constant ebb and flow of power between the center and its subnational tiers. As China has modernized, a policy dynamic has emerged wherein local officials, driven by performance metrics and economic incentives, pursue aggressive growth strategies that may diverge from central directives. This form of “adaptive authoritarianism” suggests “an entrenched process of policy generation,” where both central and subnational authorities are constantly negotiating and renegotiating policy outcomes (Heilmann, 2008, p.29–30). Such divergence has led to phenomena such as ‘localism’, where local interests sometimes supersede national priorities, creating challenges for policy coherence. This leads to foreign policy outcomes that, as Hameiri and Jones (2016, p. 91) observed, are the end product of a series of “internal conflicts among disaggregated state and semi-private actors.” For Chinese paradiplomacy with both BRI and non-BRI partners, this means that there is a wide array of policy agendas being pursued by provinces, municipalities, counties, and townships – all of whom seek to maximize their local gain within national policies. As reviewing all of these agendas would require a much longer treatment of the subject, for the purposes of this paper, we are confining ourselves to only provinces and municipalities that have ties with the three case study countries.

In many ways, the Chinese understanding of subnational behavior mirrors that of other countries. Su (2010, p. 4) identified China’s opening up in the late 1970s and the decentralization of power in the 1980s as the two catalysts for subnational activism. Wang (2011, p. 26–29) saw the process of policy decentralization as a critical way for transnational capital to become locally embedded, empowering local governments’ international activities. With respect to this point, a provincial official in Jiangxi stated, “owing to the increase in revenue, it enabled Jiangxi to actively ‘go out’ and develop friendship ties (interview 1).” However, Cheng (2012, p. 111–115) and Ou (1988, p. 25–27) both noted that, at least in the case of Tianjin and Kobe (China’s first sister city relationship), mutual interests resulted in the forging of a subnational dyad before China opened its doors.

Structurally, as local governments develop agreements with their overseas counterparts, the resulting policy framework is that of a multi-level operation where “local and global international contacts reflect the interdependence between China and the world and strengthens the fact that there is an important basis for a cooperative strategic relationship between China and the international system” (Su, 2008, p. 32). Consequently, Yang (2013, p. 296) suggested that subnational actors should be located within a foreign policy hierarchy, arguing that “with the deepening of globalization, the role of international friendship cities in China’s foreign relations is increasing.” In contrast, Wei (2021, p. 277) proposed that such activities are outside of official foreign relations but, equally, sees cities as “important agents in managing domestic and international situations, developed their communication channels by contributing in shaping China’s neighboring diplomacy and global partnerships, and developed their negotiation techniques by participating in reform of global governance system.” Even within the Chinese context of paradiplomacy, the key question of whether such activities occur inside or outside of national foreign policymaking processes remains debatable.

To resolve this positionality, Chinese scholarship frequently uses other discursive labels to describe what would otherwise be called paradiplomatic activities. In Chinese narratives, “external affairs of subnational governments” or “local foreign affairs” are more commonly used alternative nomenclatures. Chen (2001, p. 5) put forward the former term, defining it as “a general term for activities carried out by the subnational governments concerned with the aim of affecting various international actors, including individuals, organizations, governments, and companies that are/are not subject to the jurisdiction of the country, as well as their international interactions.” Qi (2010, p. 67) claims that these are equivalent to the external affairs of subnational governments in unitary systems, such as China. Zhao (1995, p. 23) and Zhang (2015, p. 8) highlighted local governments’ compliance with national policies. Local foreign affairs must ensure that local actions follow the central government’s policies unconditionally. However, by reviewing the development of China’s opening-up at the subnational level, Ren (2017, p. 105) specified their increasingly independent role and suggested that they have the potential for cross-border cooperation and can influence Chinese foreign policymaking at the national level.

Although the Chinese national government has not made official statements in support of paradiplomacy per se, in 2014, Chinese President Xi delivered a key speech at the China International Friendship Conference emphasizing the necessity of promoting city diplomacy and local exchanges between China and foreign countries, importance of resource sharing, the development of complementary advantages, and nurture win-win cooperation. President Xi’s speech highlighted the way the practice of paradiplomacy has expanded within the Chinese context and has become a de facto affirmation of paradiplomatic practices. More recently, these practices have been supplemented through the promulgation of other policies, such as the Global Civilization Initiative, which emphasizes the types of people-to-people exchanges and public diplomacy that President Eisenhower once championed (Chao, 2024, p. 32–34).

Along with the “external affairs” and “local foreign affairs” descriptors, public diplomacy and city diplomacy are frequently examined from a paradiplomatic perspective. Yang (2013, p. 296) positioned sister cities within the hierarchy of public diplomacy and concluded that to fully leverage the role of these cities in public diplomacy, it is necessary to deeply understand their “flexible” and “semi-official” relationships, as it enhances their utility for the central government (Yang, 2013, p. 300). Jia (2011, p. 52) highlights that sister cities are vital platforms for fostering international relations by local governments and are essential for collaboration among cities across various nations. They also represent the principal methods of city and local governmental diplomacy. Jia (2011, p. 46) concurs with Yang in acknowledging that these diplomatic efforts are semi-official and secondary to the country’s overarching diplomatic goals. These conclusions represent the main Chinese understanding of paradiplomacy where the emphasis is more grounded on the practice of subnational ties.

As part of this, Chinese scholarship identifies shifts in power and authority between the central and local governments as the core drivers of the country’s paradiplomatic efforts. Yang (2007, p. 43–47) argued that the decentralization of the central government (especially in financial matters) provided local governments with the capacity to pursue their own interests. These have developed, as subnational governments have gained increased resources and policy freedoms. Consequently, local governments can identify opportunities for external opportunities based on their own efforts. Such behavior is not prohibited by the central authorities, provided that national security and sovereignty are not threatened (Su, 2010, p. 8–9). A good example is the acquisition of foreign direct investment (FDI), which meets local investment needs but is promoted by the central authorities (Li, 2014, p. 4). In 2023, for instance, just ten provinces (Guangdong, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong, Beijing, Fujian, Sichuan, Hainan, and Tianjin) received more than 86% of all FDI in China, whereas two super-city clusters (the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region) attracted more than 63 percent of the total FDI (Interesse, 2024). The actions of these cities and provinces are designed to benefit their local populations but also support national agendas.

To explore the foreign policy implications of the shifts in centralized and decentralized policy structures, Chen (2001, p. 161–163) put forward four basic modes of interaction between central government diplomacy and local government external relations—agency, collaboration, complementarity, and conflict. The first two models are more common in unitary systems, whereas the latter two fall under the umbrella of paradiplomacy. Wang (2003, p. 176) later coined the term of “sub-central diplomacy” and argued that these sub-central units have an impact on China’s diplomacy. Zhang (2015, p. 97–98) outlined two models of local participation in external relations—the central–local collaboration and the central–local coopetition. In the central-local collaboration model, the central government delegates a certain authority to local governments regarding foreign affairs, which allows local governments to function more efficiently by clearly defining the scope of their international activities and reducing constant bargaining with the central authority. In the central–local coopetition model, the central and local governments negotiate and address foreign affairs in parallel. However, this approach involves constant bargaining, which can complicate the decision-making processes. These approaches highlight the domestic driving forces of China’s paradiplomacy. Although divergent policy strategies emerge due to these approaches between central and local policymakers, the final decision-making power rests with Beijing. Such disagreements are resolved at the negotiating/bargaining phase of both models, with the public strategy being a consensus.

Since the announcement of the BRI, Chinese scholars have highlighted the way China’s subnational relations facilitate the implementation of the grand strategy (He, 2021; Zhu, 2019; Wu and Li, 2018; Yang, 2018). Liu (2015, p. 102–118) and Summers (2016, p. 1628–1643) underscored that the BRI implementation relied heavily on local governments. Chen and Wei (2016, p. 34–35) argued that the economic focus of the BRI brought local policy agendas to the fore of subnational governments’ external interactions, reducing policy pressure to safeguard security and sovereignty. From this perspective, subnational relations in the BRI context are a logical product of the socialization of diplomacy and an inevitable result of the central government’s policy. Empirically, Gao (2023, p. 84–85) focused on the China-Russian Yangtze-Volga River Regional Economic Cooperation Initiative. In March 2015, this cooperation mechanism, operated by subnational governments, was incorporated into the Vision and Action for Promoting the Construction of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, marking the first time when a subnational mechanism became an officially part of the BRI strategy.

Considering the previous discussion, it is evident that the diplomatic practices by China’s subnational governments under the BRI framework are not independent actors who can develop their own international ties. However, at the same time, the central government relies on the subnational governments to be at the forefront of BRI engagement, thereby implicitly requiring these local actors to have a high degree of leeway in the way they operationalize their engagement strategies. Local governments are not actors representing the sovereignty of the state. The permission, authorization, or acquiescence of the central government is the most fundamental prerequisite for China’s local governments to engage in external activities (Chen, 2001, p. 24–25). This reinforces Su’s argument that subnational actors play complementary, supplementary, and supportive roles in overall diplomacy (2010, p. 4). These practices and the empowerment by the central government regarding economic and cultural cooperation suggest a bridgehead-type role for local governments along the BRI. Cheung and Tang (2001, p. 106–107) highlighted the role played by Guangdong in improving relations between China and Southeast Asia across various regional and subregional forums. In recent years, other provinces have played similar roles in developing economic and cultural relations with their overseas counterparts (Li, 2014, p. 275–293; Ye, 2025, p.43–60).

By reviewing the Chinese approach to paradiplomacy, this section argues that there is greater acknowledgement and utilization of such practices in foreign policymaking. Although China remains a highly centralized state, both the theoretical arguments and applied aspects of paradiplomacy highlight that, in practice, Chinese subnational actors evince a degree of local initiative in advancing both their own agendas alongside those of the central government. Therefore, subnational actors are imbued with a degree of trust by the central government based on local governments’ understanding of China’s domestic policy. However, to meet BRI goals, local governments must have the support of people. This reinforces the need to incorporate social attitudes into China’s subnational BRI engagement. The rest of the article briefly reviews the policy evolution of the BRI and its utilization by subnational actors before moving forward with the survey findings and case studies.

3 Paradiplomatic policy environments and the BRI

Despite being a centralized state, China has encouraged its subnational actors to be at the forefront of major policy initiatives since the 1970s. Initiatives, such as the Open Door policy, the Go West strategy, the Going Out policy, and the BRI, have attempted to infuse China’s subnational authorities with the economic capacity and policy experience necessary to manage and develop partnerships with their overseas counterparts. This section examines the role of subnational actors in Chinese policymaking, emphasizing their contributions to the BRI. In doing so, it will first explore the key role of subnational actors in Chinese policymaking. Then, the evolution of the BRI, one of contemporary China’s most significant international commitments, is analyzed. The role of supporting institutions within the BRI policy ecosystem, namely, the AIIB, the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), are also reviewed. The final section focuses on the roles of subnational actors in the BRI context.

Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door policy devolved power and authority to local governments, empowering them to carry out modernization reforms, particularly by attracting foreign capital and technologies. In the early 1980s, further reforms were made to the tax system, which allowed local governments to generate more revenue. This, in turn, provided them with a greater capacity to develop international connections and partnerships. Provincial governments were quick to use these new freedoms to establish trade representation in more advanced economies. Critically, these representatives were “directly responsible to the provincial authorities but not to the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade in Beijing” (Huan, 1986, p. 5).

In parallel with the provinces emerging as international actors, Chinese cities also began developing their respective international identities. As a part of these reforms, four Special Economic Zones (SEZs) were established in Shenzhen, Shantou, Zhuhai, and Xiamen. These cities had greater freedom in attracting foreign investments and technologies. Over the next two decades, more SEZs were developed in coastal regions, facilitating free trade, industrial development, and other types of zones, all designed to maximize China’s ability to economically engage with the outside world. In the process, more cities and regions were empowered to become active on the international stage. Zweig (1991, p. 717) reported that, even at the township and village enterprise level, international trade ties provided increasingly significant revenue streams, which increased from US$2.38 billion in 1984/85 to $12.5 billion in 1990. Owing to these decentralization policies, not only the subnational actors were able to develop ties with their overseas counterparts (Segal, 1995, p. 345) but also due to their increased income, they gained political and economic powers to influence policies (Herrschel and Newman, 2017, p. 13). By the end of the 1990s, Chinese provincial and municipal governments had become highly active as independent economic actors on the international stage, building trusted partnerships with their subnational counterparts around the world.

At the beginning of the new century, China’s subnational focus shifted from coastal to inland provinces. The Western Development strategy (aka the “Go West” policy) sought to redistribute—as well as attract—wealth and capacity to less-developed inland regions, which had been falling behind their coastal counterparts since the Open Door policy was initiated. Even before the new strategy was announced, the central government pushed more developed subnational governments to provide aid and expertise to the Western region. Tian (2004, p. 621) noted, that “In May 1996, the central government called for city-to-city and province-to-province aid programs between rich coastal and poor interior regions. Shanghai, Beijing, Jiangsu, Guangdong and other eastern provinces [all) launched their assistance programs.”3 However, the growing disparities among the provinces indicated that a more systematic approach was required.

President Jiang announced the Go West strategy in 1999 during the National Party Congress (Lai, 2002, p. 436). However, rather than promoting development for the sake of development, this strategy focused on the positive externalities, such as increased investments, environment, and resource development, that could be introduced to this region (Lai 2022, p. 436.). To achieve these objectives, the central government relied on both co-opted and voluntary support from provinces and cities as key drivers (as well as recipients) of the Go West policy (Goodman, 2004, p. 333). The Hand-in-Hand Aid (HHA) program and the Counterpart Support (CS) policy exemplify such support. Under the HHA, subnational actors proposed aid strategies, which were approved and directed by the central government, whereas the CS policy was a market-driven aid approach, which encouraged subnational authorities and companies to set their respective criteria and conditions for investing in the Western region (Lu and Deng, 2011, p. 8–9). These two policies not only helped China modernize but also empowered provincial and municipal authorities to develop their own programs for operationalization beyond their immediate policy environs. Wong (2018, p. 737) concluded, that “the broad scope and diffuse implementation of the “open up the west” development campaign facilitated center–local bargaining and inter-provincial competition for benefits.” This subsequently encouraged the formation of locally oriented policy communities at the subnational level with the capacity to engage with their domestic counterparts and international interlocutors. Hence, even before President Jiang promoted the “Going Out” policy, an array of provinces and cities in China were already used to doing so.

The “Going Out” strategy was announced in March 2000 as a new phase in China’s internationalization. Although initially focused on economic and investment opportunities, this strategy discursively expanded to encompass political and social agendas centered on the theme of global engagement (Yang and Ocón, 2024, p. 445–468). As with the earlier strategies, subnational actors not only drove the “Going Out” agenda but also shaped it according to their local priorities. From the perspective of international economic engagement, Yelery (2014, p. 3) observed that provincial approaches reflected “the aspirations of local industries; although the broad policy directives came from the Central Committee via MOFCOM, the local bodies comprising local business elites decided the final shape of these decisions…CCPIT Councils have been set up at the municipal and provincial levels. These local councils follow their own suborbital trajectories while keeping their policies in line with the larger ‘going out’ principles.” The development of these economic and social agendas at the provincial level directly opened the Chinese provinces to the world, which “together with greater provincial discretion in the acquisition of foreign capital, helps to boost their influence over that of business lobbies in many foreign capitals” (Cheung and Tang, 2001, p. 120).

3.1 The BRI

The BRI, originally the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, was launched in 2013 by President Xi (2014, 2017), building on the “Going Out Policy” (Banach and Gunter, 2023). The initiative was (initially) a controversial announcement, with questions raised regarding China’s underlying intentions in undertaking such a significant shift away from its previous, more low-key, foreign-policy engagements. Nevertheless, this initiative was formalized in March 2015 by the State Council in the Vision and Actions document (The State Council, 2017). Domestically, the BRI aimed to provide a more conducive environment for development, particularly by creating more opportunities for investment (Yu, 2017, p. 353–368). Internationally, the initiative’s policy goals are centered on enhancing regional and international connectivity through infrastructure development, financial and trade interdependence, and sociocultural exchanges. Currently, the BRI prioritizes five key fields, with approximately 150 partner countries as of May 2025 (Nedopil, 2025). The Office of Leading Group for the BRI (2017, p. 18) identified a series of areas for bilateral and multilateral cooperation with a focus on economic and cultural development, including “policy coordination, connectivity of infrastructure and facilities, unimpeded trade, financial integration and closer people-to-people ties.” As noted in the previous section, both the foci of the BRI and local-level policy concentration align well with the types of activities that Chinese subnational actors actively pursue.

The BRI is supported by several institutions that provide additional financial and diplomatic resources, with the AIIB being the main adjacent institution. Xiao suggested that the AIIB, along with the BRI, represents the latest institutional stage in China’s development in a lineage, going back to the Open Door policy (Xiao, 2016, p. 440). Haga (2021, p. 395–396) observed that China initiated AIIB in the same year as the BRI to send a message that the country was “ready to utilize its full economic power to steer regional development.” Although the memberships of the AIIB and BRI overlap, they are not identical. For example, Kyrgyzstan is both a BRI and AIIB member, but India is only an AIIB member, with Japan joining neither institution. The BRICS NDB is another financial institution that supports BRI members including India. Cooper (2017, p. 275, 281) argues that, despite China’s de facto veto in the AIIB and that it retained its outsized influence on bond issuances and credit ratings, the initial capital of the NDB was shared among its five members, which weakened Beijing’s leadership position. The FOCAC, established in 2000, was co-opted into the BRI in 2018. Both the FOCAC and NDB provide institutional mechanisms for the operationalization of BRI programs in areas removed from China’s immediate periphery.

In addition to state actors, Summers (2016, p. 1628–1643) and Blanchard and Flint (2017, p. 223–245) noted the involvement of subnational actors in the BRI. Their involvement suggests that China’s complex central–local relations followed a “fragmented authoritarian” model, in which a dynamic balance exists between central control and subnational autonomy, providing subnational actors with the capacity to translate national directives into local actions (Lieberthal, 1992, p. 1–30; Donaldson, 2016, p. 15–32). Provinces such as Guangdong and Yunnan leverage their economic and geographic advantages to influence policy from the bottom-up. For instance, Summers (2021, p. 206) found that Yunnan is more of an “influencer” and “interpreter,” rather than simply a passive follower in responding to the BRI. This policy dynamism has created an ongoing set of negotiations between local governments and Beijing, ensuring subnational commitment while advancing national goals. Jones and Zou (2017, p. 743–760) highlighted the role of state-owned enterprises in this process, arguing that they are often coordinated by provincial authorities, further amplifying their influence, especially in the BRI’s larger-scale projects.

To advance these policy agendas, the other arms of China’s diplomatic structure actively draw upon subnational actors. For example, the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) organizes exchanges with foreign subnational actors to develop Chinese foreign policymaking, such as collaborating with California’s leadership to develop smart cities and resolve climate issues (Bruyere and Picarsic, 2024). Similarly, President Xi has actively promoted the Belt and Road Sustainable Cities Alliance and people-to-people connectivity (Belt and Road Forum, 2017; MFA, 2019). In addition, the 13th and 14th Five-Year Plans mention the role of subnational actors in China’s development initiatives. For example, the 2016–2020 Plan encouraged cultural exchange along the BRI, such as the Silk Road (Dunhuang) International Cultural EXPO, whilst the 2021–2025 Plan promoted the construction of BRI core areas in Fujian and Xinjiang (The State Council, 2016, 2021). These statements reflect a decentralized approach, through which subnational actors adapt the BRI goals to local conditions. Hence, Chinese subnational actors gain the capacity to engage with their overseas counterparts through policy and capacity decentralization processes, and directly co-opt into foreign policymaking frameworks to advance specific agendas. However, to what extent Chinese people support these activities remains unexplored.

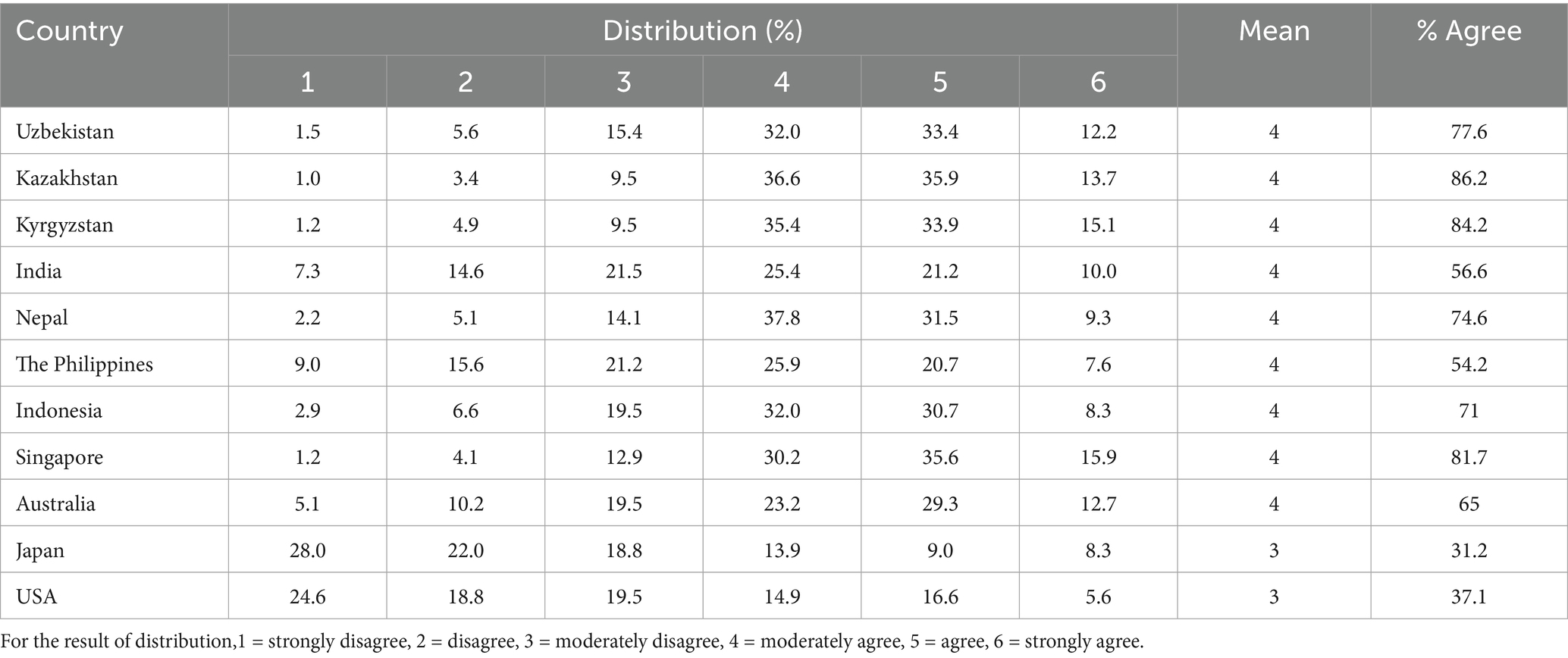

At a foundational level, popular support can be seen in levels of belief that the surrounding countries have friendly intentions towards China. However, as Table 1 shows Chinese respondents did not perceive surrounding countries as particularly friendly. When asked whether they agreed or disagreed that a country was friendly toward China, the respondents only moderately agreed that the surrounding region was composed of friendly countries. However, when comparing BRI and non-BRI countries, there was a clear distinction in perceptions of friendliness. Overall, 79.21% of respondents agreed that BRI countries were friendly towards China compared with only 48.82% of respondents who agreed with the same regarding non-BRI countries. These findings echo the results of a 2024 Asia Society survey, which also found that BRI countries had a more positive view of China than non-BRI countries (Asia Society, 2024). Given that the survey findings indicate a positive normative orientation toward BRI states, the question remains regarding the extent to which this distinction is present in BRI and non-BRI sets of subnational relations.

4 Public views of subnational relations

Although the exact number of subnational dyads between Chinese actors and their international counterparts remains elusive, Custer et al. (2018, p. 12) estimated that China has forged more than 2,500 of such partnerships since 1973 (when the first agreement between Tianjin and Kobe was signed). More than one-third of these partnerships are with countries in the East Asia-Pacific region (Custer 2018, p. 12.), with China having more subnational ties with Japan than any other country. By 2024, 500 more sister cities and provincial partnerships were concluded (Wang, 2024), despite the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the interdependent penetration of local governments and networks across China’s borders, we must first explore the perspectives of Chinese people on such arrangements in terms of their focus and structure, before considering these issues with reference to the target countries.

A key rationale for subnational actors seeking international partners is to attract foreign direct investment to develop the local economy. The ties between Tianjin and Kobe ports and cities are the earliest examples of institutionalizing such motivations (Vyas, 2011, p. 114–123). Common sociocultural interests also drive subnational ties. One such example is the 2015 sister city agreement between Dunhuang and Aurangabad, which aimed to advance cultural and heritage tourism in both places (Business Standard, 2015). Shared social or recreational interests are other significant motivations for creating ties, such as those between China and Japan, in the subnational promotion of youth exchanges, the creation of sister schools, sports, and cultural exchanges (Global Times, 2024). Sister city and province ties may also be formed because of commonly held norms or personal ties. China’s subnational engagement with the Central Asia has consistently stressed the alignment of interests (Ge, 2023). Several early dyads were formed via subnational partnerships because of personal ties and shared experiences. This rationale remains valid to date. For example, Davao City formed ties with an array of Chinese cities (Nanning, Jinjiang, Tai’an, and Chongqing) owing to the presence of a large local Chinese population (Alama, 2025).

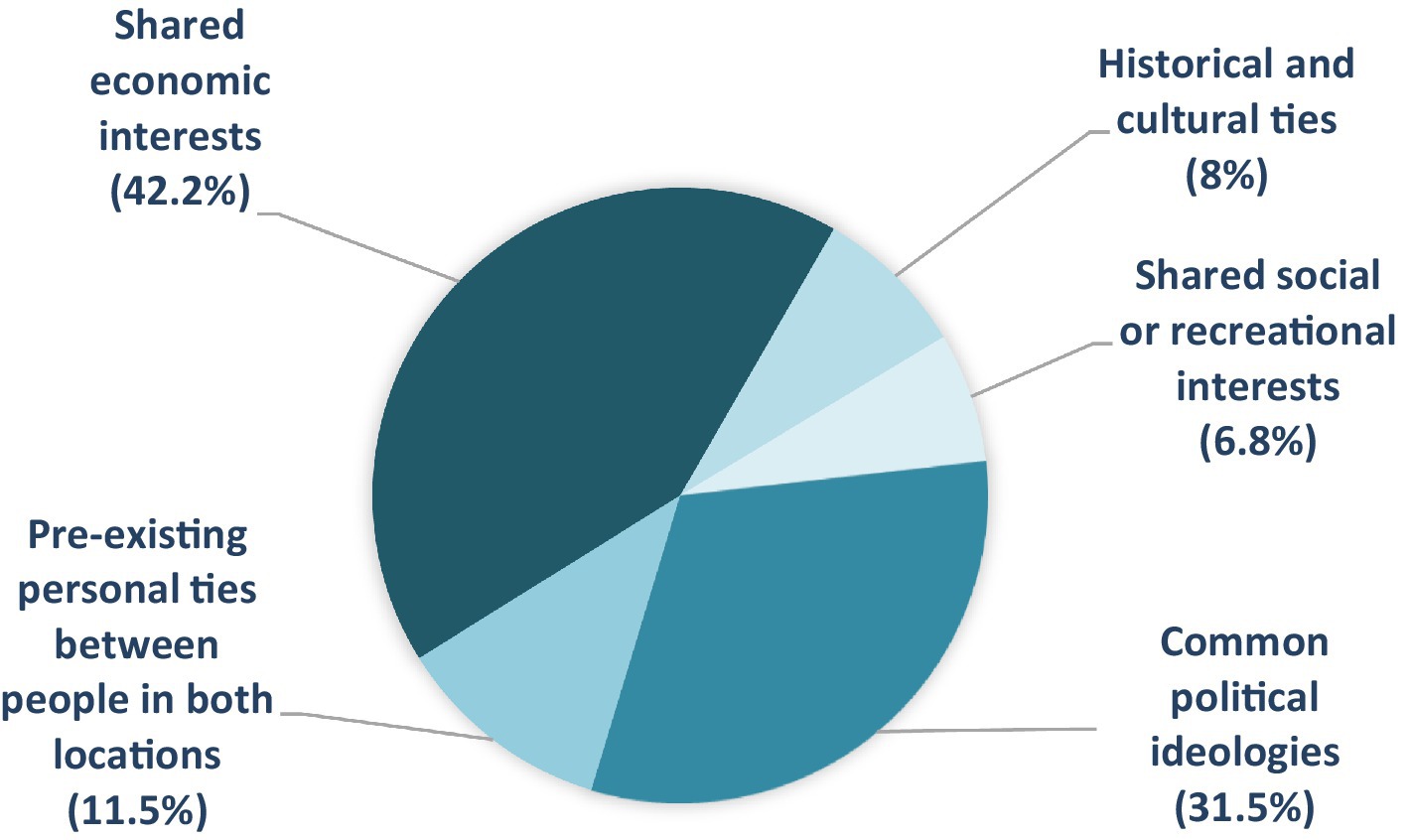

It is rare that only one of these interests a catalyst in forging subnational ties. Even at the local level, political authorities seek wider outcomes. The Tianjin-Kobe economic ties have, for example, led to social and cultural interactions (Vyas, 2011, p. 116–118), while the tourism ties between Dunhuang and Aurangabad naturally led to economic benefits from increased visitors. The largest cohort of respondents in this study selected economic reasons followed by shared political ideologies (see Figure 1) as the most important reason for choosing a subnational partner. This suggests a highly functional view of subnational relations, in which such ties are directly associated with the developmental agenda of the state and local society, rather than an Eisenhower-style agenda, in which pre-existing historical, personal, or social ties are leveraged to create spaces for mutual understanding and peace.

Figure 1. Which one of these aspects of subnational relations do you think should be the most important when it comes to choosing overseas partners?

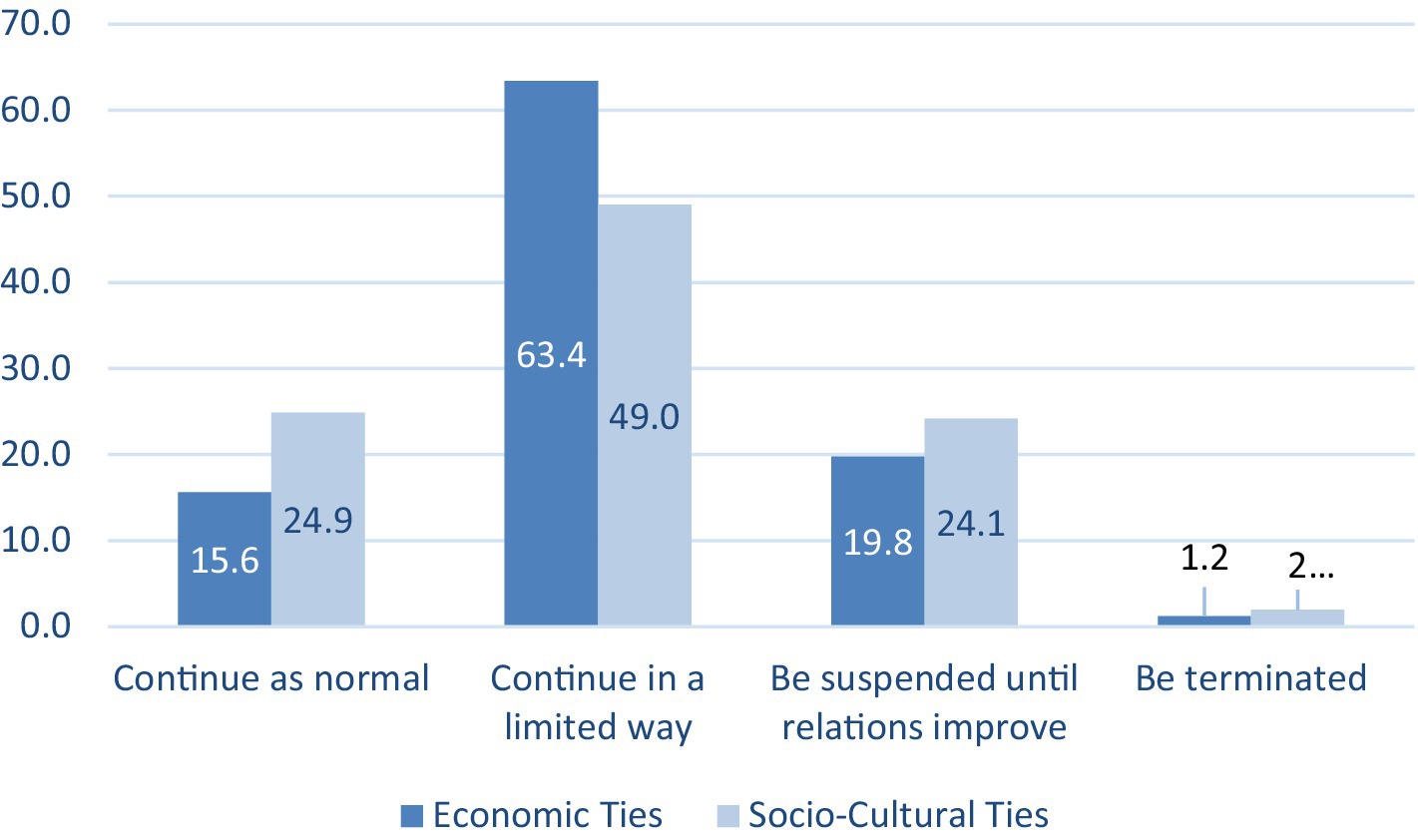

However, in terms of the importance of such issues for developing China’s international relations, respondents observed that diplomatic and subnational ties were relatively equal in status—97 and 96% of the respondents agreed that diplomatic relations and subnational relations, respectively, were important. However, economic ties were noted to be more important than sociocultural relations. More respondents (79.0%) believed that economic ties should be encouraged to continue, although in a limited manner, relative to sociocultural ties (73.9%) (Figure 2). The respondents noted that sociocultural relations were more vulnerable to bilateral tensions, with a greater proportion of those suggesting that they should be suspended or terminated during this period. Although the difference in these figures is not significant, it indicates a preference for safeguarding economic relationships. This, in turn, supports the previous observation that Chinese people may hold a more functional developmental view of subnational relations than the original Eisenhower construct.

Figure 2. If the diplomatic relationship between China and another country became confrontational, should existing economic/socio-cultural ties.

The successive waves of decentralization characterizing the Chinese political system since the Open Door policy empowered subnational actors to create external relations with their counterparts in other countries. The demographic profile of respondents in this study demonstrates that approximately 85% of them have grown up witnessing formation of economic and sociocultural dyads between provinces and cities. However, it remains unclear whether the general population supports such activities. To understand whether such support existed and whether there was support for the policy structure within which these activities took place, respondents were asked of the following questions: (1) should subnational actors be empowered to develop their own foreign economic and sociocultural relations, (2) if so, how should the relations be operationalized, and (3) what role should public opinion play in these relationships?

In answering these questions, an overwhelming majority of the respondents agreed that provinces should be able to develop their own foreign economic and socio-cultural relations (91 and 92%, respectively). There was a similarly high degree of support for cities pursuing their own foreign economic and sociocultural relations, with 91% of the respondents agreeing with both propositions. However, although there was strong support for such activities, 50% the respondents felt that these types of subnational foreign relations should be strongly regulated by central authorities via direct or daily monitoring. An additional 41% of the respondents saw a role for the central authorities in the initial phase of the relationship, but under their own purview, only 9% believed in the autonomy of provinces in this domain. In terms of cities forging subnational economic and sociocultural links, the respondents similarly saw a role for the central authorities, although these responses were slightly attenuated toward local agencies. Here, 48.5% of the respondents felt that the central authorities should regulate municipal activities, with 39.3% suggesting that the central authorities should be involved in the initial phase of the relationship and 12.2% supporting the autonomous agency of cities.

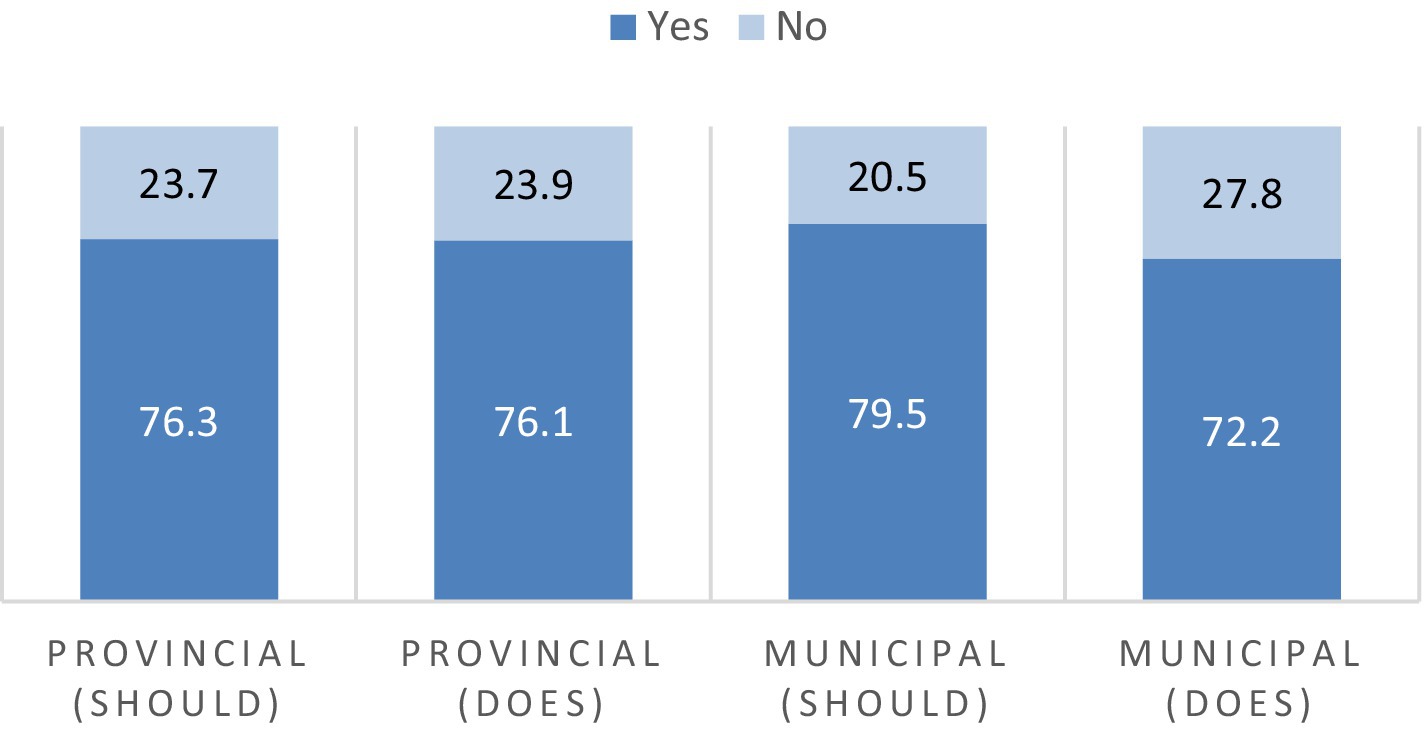

Given these findings, a secondary issue is whether people feel that their subnational governments listen to the public opinion when creating overseas partnerships. A significant majority of the respondents felt that both provincial and municipal governments sought the public’s opinion when developing links with their overseas counterparts (Figure 3). Similarly high responses were received when they were asked whether the central authorities should seek public opinion when formulating foreign policy. A total of 71% indicated that the central government should seek public opinion, and 72.4% indicated that they do seek public opinion when formulating foreign policy.

Figure 3. Should/does the (provincial/municipal) government seek public opinion in establishing subnational relations with overseas partners?

These responses also validate the findings of Chinese scholars of paradiplomacy reviewed above. The distinction between the usual role of the central authorities and that in the early stages of the relationship further echoes the outcomes of interviews conducted with Chinese officials at the provincial and municipal levels. Although the central authorities initially screen the proposed dyad, their subsequent involvement is usually limited to approving annual reports on the activities of the relationship. A more substantive central presence is observed only when the dyad is of strategic significance, for example, being co-opted into a national policy initiative.

Interestingly, a high level of alignment was noted in public opinion questions relating to the way subnational and national authorities consider popular sentiment. Although these responses do not automatically imply that public opinion is factored into the decision-making process, it is perceived that policymakers listen to such sentiments. This suggests a high degree of trust towards the government policymaking process. In this case, it further suggests that there is a pre-existing social basis that supports the creation and operation of these dyads (Zhuang, 2020, p. 3–23). However, rather than the “local liberalism” proposed by Li (2013, p. 275–293), our findings suggest that Chinese paradiplomacy would best be characterized as “constrained liberalism,” as it is constrained by both policy structures and public opinion. The next section explores the way these policy and opinion structures shape China’s subnational relationships with the three case study countries.

5 Paradiplomatic case studies

Two policy impetuses become intertwined when exploring subnational relations on and off the BRI. Since the 1970s, China has actively sought economic and social development by fostering the capacity of subnational actors to attract foreign investment. From the Open Door policy to the Going Out strategy, this policy of building China from the bottom-up has encouraged the development of possibly the largest array of subnational agreements (3,000 agreements as of 2024). These agreements were designed to provide opportunities for knowledge transfer, investment, and sociocultural exchange. In these respects, the agreements were highly functional and more concerned with domestic outcomes than geopolitics.

The BRI is a more recent policy construct that considers the developmental aspects of earlier policies and elevates them to a global level. Unlike the locally driven nature of subnational development, the BRI has a centrally coordinated foreign policy mechanism supported by an array of international institutions. Although the BRI has approximately half of all countries as members, there is still a strong normative/ideological component to its activities (Comerma, 2024). Han et al. (2022, p. 3418), for example, found a complementary link between the BRI and sister city dyads with respect to the outward flows of Chinese investment. Vlad (2024, p. 13–25) also observed the impact of social norms on the directionality of foreign direct investment. Hence, as the inherent Chinese values of the BRI are disseminated along institutional lines, those countries along the BRI will be seen more positively by the Chinese people and that; consequently, those subnational relations will be valued more significantly. To demonstrate this, the Chinese views of subnational relations with three countries that have differing degrees of engagement with the BRI —Kyrgyzstan, India, and Japan—have been explored.

5.1 China–Kyrgyzstan subnational relations

Steady bilateral relations have existed between China and Kyrgyzstan since January 1992; although these were initially focus on political and security matters. As Beijing became more focused on Central Asia’s market prospects, it subsequently commenced a program of regular high-level visits with a focus on economic and sociocultural cooperation. Subnational interactions between China and Kyrgyzstan started one year after the commencement of diplomatic relations. As of June 2025, 28 sister dyads exist between Kyrgyzstan and China, and 22 of these were formed after the BRI was initiated (CPAFFC, 2025a). Geographic proximity and ethnic homogeneity enabled Urumqi to establish its first sister-city relationship with Bishkek in 1993. In the following years, the Xinjiang Autonomous Region government also promoted provincial-level ties with Kyrgyzstan and other local Central Asian governments (Xinjiang Government, 2016).

Cultural and top-down promotions have driven the interaction among local administrations of Hubei, Henan, and Kyrgyzstan (FAO of Hubei, 1997; FAO of Henan, 2023), whereas other partnerships have emerged via economic interactions. The interviewees in Kyrgyzstan noted that subnational ties were a novel policy development for the Kyrgyz government, requiring Chinese partners to lead their operation (Interviews 2, 3, 4). Owing to this, Sino–Kyrgyzstan subnational engagement naturally aligned with Chinese approaches to paradiplomacy where functional or developmental forms of cooperation were prioritized, rather than the people-to-people engagement. As most of these ties were forged post-BRI, they can either be viewed as an opportunistic behavior on the part of Chinese provinces and cities or as a result of central-level encouragement or co-option of subnational actors’ external capacities to advance a major foreign policy endeavor.

Given Kyrgyzstan’s BRI membership and its subnational ties with China, it is useful to consider the way Chinese people perceive the country and the importance they give to the various national and subnational aspects of this relationship. The respondents were overwhelmingly positive in their assessments of the Kyrgyz government and people. Of the respondents, 96.5% agreed that the Kyrgyzstan government had an overall friendly approach toward China. Similarly, 95.1% of the respondents felt the same about the Kyrgyz people. Although other survey data from Central Asia indicate that the Kyrgyz people are generally positive toward China (approximately 74.0%), these sentiments are more likely to be tempered by concerns related to the impact of Chinese projects and presence of Chinese workers (Neafie et al., 2024, p. 11, 13–14). These figures are comparable with those of other studies, which found that 76.3% of the Kyrgyz people held favorable views of China (Yau, 2024). The presence of China in Kyrgyzstan is significantly higher than that of Kyrgyzstan in China, which may explain the difference in the responses.

While reflecting on the importance of Kyrgyzstan for China, 89.8 and 84.9% of the respondents felt that Kyrgyzstan was important for China’s international diplomacy and economic development, respectively. Given the significance of Kyrgyzstan as a founding member of both the BRI and SCO, the country could be perceived as playing an outsized role in China’s diplomatic affairs. This perception has been reinforced by the frequency of leadership meetings, with five state visits since 2021 (Mo, 2025). Economically, China is Kyrgyzstan’s largest trading partner. Alejandro and Ekstrom (2024) stated, “In 2023, China was Kyrgyzstan’s top trade partner, comprising approximately $5.5 billion, or a 35 percent share of Kyrgyzstan’s annual trade turnover total of $15.7 billion. Furthermore, China is integrating itself into Kyrgyz affairs through transport and logistics projects.” Although concerns exist about Kyrgyzstan’s ability to meet its financial commitments to China (VoA, 2024), these are external concerns that are not significant in domestic narratives on bilateral relationships. Social and cultural relations between these two countries were highly regarded, with 85.9% of the respondents asserting these important for China. Although the sample size is limited, outbound tourism data convey that Kyrgyzstan is favored as a tourist destination by Chinese people. In 2024, approximately 128,000 Chinese tourists visited the country, indicating a 56% growth compared with that of the previous year (Kabar, 2025).

These highly positive perceptions explain why 90% of the respondents indicated that subnational relations were important for overall bilateral relationships. In addition, comments representative of this perception focused on the bilateral significance of local relations between China and Kyrgyzstan, the impact of BRI on bilateral relations between China and Kyrgyzstan, and growing emphasis on strengthening local relations between China and Kyrgyzstan. Although respondents who were less positive stated that “It will not affect the rapid development of the two places,” and “This relationship is not that important,” several others suggested that the subnational relationship should be continued if it contributed to China’s benefit.

Despite its small size, Kyrgyzstan has an outsized presence in China’s regional engagements; one where the BRI has played a central role in the evolution of this partnership. It has deepened bilateral relations, which were characterized as a “strategic partnership” in 2013 and later elevated to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” in 2023 (Belt and Road Portal, 2018; MFA, 2023). Two interviewees (Interviews 5 and 6) noted that infrastructure projects and education exchanges rose under the BRI – both of which support development at the local levels. Although some dyads started prior to the announcement of the BRI, most subnational dyads were created post-BRI. One interviewee showed the remarkable trend of Chinese companies, especially those from West China, expanding their business to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan with incentives, followed by the BRI (Interview 9). The findings clearly indicate a high support from public for the formation and expansion of subnational ties with Kyrgyzstan, with numerous survey comments calling for China to “continue to strengthen local cooperation.”

Although the respondents expressed diverse opinions on the association between China and Kyrgyzstan with respect to diplomatic relations, the emphasis on deepening local and diplomatic engagements between the two countries received the highest prominence. One respondent wrote, for example, subnational ties “are not in conflict with diplomatic relations but complement each other. Diplomatic relations are more about national-level strategic mutual trust and policy coordination, [subnational ties) focus more on the implementation of specific projects and deepening of people-to-people exchanges.” However, some statements identified subnational dyads as secondary to diplomatic ties. While responding to this aspect, one respondent argued, “diplomatic relations are more critical due to their influence on interactions between the two countries.” Similarly, some felt that local relations were more important than diplomatic ties, and that local relations between China and Kyrgyzstan should be expanded as these were more important than diplomatic relations. Taken together, these findings suggest a high degree of social support for paradiplomatic behavior by Chinese subnational governments in China–Kazakhstan subnational relations. Whether or not these attitudes hold for other countries will next be tested in the case of India.

5.2 China–India subnational relations

In the beginning, the Sino–Indian relationship was one of the most cordial relationships in Asia, with personal connections between leaders and normative alignments in their geopolitical perspectives. Despite this positive start, territorial disputes and regional tensions resulted in the 1962 Sino-Indian War (Madan, 2021, p. 3–4). Thereafter, the relationship between these two countries has been episodically disrupted by significant border clashes (ANI, 2020; Ali, 2024). Although plagued by diplomatic and military tensions, both China and India have expanded their bilateral trade, with China becoming India’s second largest trading partner. In 2024–2025, the overall trade was valued at US$127.7 billion (Kumar, 2025). This economic interconnection has helped to reduce tensions, emerging as a key diplomatic plank in normalizing relations at both national and subnational levels.

China’s subnational ties with India are the most recent extension of Chinese paradiplomacy, commencing in 2013. These ties are seen as mechanisms to improve relations beyond the more tense diplomatic realm. Initially, three dyads were created—Kunming and Kolkata, Beijing–Delhi, and Chengdu–Bangladesh. In 2014, another set of subnational ties was formed at the sister-city level (Guangzhou–Ahmedabad and Shanghai–Mumbai) and the provincial level (Guangdong–Gujarat). In 2015, relations at both levels were deepened by a new sister-province relationship between Sichuan and Karnataka and three more sister-city ties, including Chongqing–Chennai, Qingdao–Hyderabad, and Dunhuang–Aurangabad. Although these were championed by President Xi and Prime Minister Modi, the institutionalization of several of these ties was an outgrowth of pre-existing partnerships. Kunming and Kolkata had been operating the Kolkata to Kunming (K2K) forum for a decade before the dyad was created as well were the key subnational actors in the “proposed Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar (BCIM) Economic corridor” (Rajan, 2013). Chengdu and Bangalore also had municipal relations that extended back to 2005 (Chengdu Government, 2013).

As these ties have been either deliberately co-opted by the central authorities of both states or were created to improve diplomatic and economic relations, it is implied that they are more aligned with the national strategies than those that naturally emerged from local interests. One interviewee (Interview 10) claimed “fake friendship not only works for the bilateral relations between China and India, but also can be an implication for their subnational ties – they do this only for interest.” As Thomas (2024, p. 412) found, “In an interview in Kunming in 2014, this level of central involvement was confirmed with the interviewee stating that ‘without the support of the two leaders, Kunming and Kolkata could not sign the friendship agreement.” The central focus of these agreements was to increase economic development and investment opportunities. One interviewee noted that local governments have very limited autonomy to develop sister ties, and their motivation to do so varies across states. Geographic location and local interests were crucial (Interview 8). For example, the Chongqing–Chennai, Qingdao–Hyderabad, and Dunhuang–Aurangabad dyads have been designed to attract Chinese investment and knowledge transfer (Divya, 2015; Sudhir, 2015). Similarly, the Guangzhou–Ahmedabad and Guangdong–Gujarat dyads were focused on cooperation “in economy and trade, environmental protection, public policy education, health, science and technology, tourism, and culture” (Desh, 2014). Therefore, for China–India relations, there is a more explicit incorporation of subnational agreements into the diplomatic relationship.

Although India is a founding member of the AIIB, it has not joined the BRI and is unlikely to do so without a significant shift in its internal politics. As such, when it comes to Sino–India subnational relations, there are more structural legacies impeding bilateral ties compared with those with Kyrgyzstan. It is not surprising, therefore, that a significantly lower proportion of respondents (65.1%) found the Indian government to be friendly. These national perceptions are comparable to those toward the Indian people, with only 69.5% seeing Indians as friendly towards China. These findings are slightly more optimistic than those of other surveys. The 2024 Chinese Outlook on International Security (CIOS) found that most Chinese had a “somewhat unfavorable” view of India (CISS, 2024, p. 10).

Despite these challenges, most respondents felt that India was important for China’s diplomacy (85.9%) and economic development (80.2%). As India is the dominant nuclear power in South Asia, a region where China also has significant diplomatic and strategic interests, this perception can be considered valid. India is, however, economically less developed than China with the value of bilateral trade increasingly tilting in favor of China (Khan, 2025; Kumar, 2025). Reflecting the wider challenges within the relationship, social and cultural relations were seen as less important than diplomatic or economic ties, with only 76.6% of the respondents perceiving them as important. While a 2024 Global Times survey indicated that Chinese people were interested in learning about Indian culture and planned to visit India (Shan et al., 2024), this did not result in actual visits. Prior to the pandemic, India issued more than 200,000 visas to Chinese visitors. As of 2024, that number had dropped to 2,000 (Chu, 2024); although the thawing of relations in early 2025 led to China issuing more visas for Indians (Business Today, 2025), it is unclear (as of mid-2025) if the changing diplomatic circumstances will lead to reciprocal Chinese engagement. Until then, the potential contribution of social and cultural connections to the relationship remains unrealized.

These tensions and imbalances in the diplomatic relationship affected respondents’ views on the importance of subnational ties between China and India. However, a higher percentage of respondents was in favor of institutionalized ties at the subnational level than social and cultural relations, with 80.2% of the respondents agreeing that such ties were important to the overall relationship. Those who suggested that subnational relations were either partially or holistically important for the relationship between China and India frequently identified a need to increase sociocultural and economic ties between the two countries. These ties are related to other aspects of the overall relationship. One respondent remarked, “China and India should strengthen local relations, enhance exchanges between the people, reduce misunderstandings, and build mutual trust.” This view was supported by another respondent who suggested, “Local relations between China and India have potential and should continue to expand, with coordinated development in all aspects to jointly promote the progress of bilateral relations.” Those who viewed subnational ties more negatively focused on national-level impediments, such as the impact of the border issue: “Sino-Indian relations have not always been friendly…However, improving relations is difficult, mainly due to border issues” or the general state of the relationship “I do not have much confidence in the relationship between the two countries.”

Despite these tensions, approximately 70% of the respondents felt that the Indians were friendly toward China. There was also strong recognition (over 80%) that India was important to China’s diplomatic and economic development. These findings suggest that, despite the legacy of mistrust between the governments, Chinese engagement with India has a social foundation. This, in turn, suggests that a distinction can be made between the way the Chinese view diplomatic relations at the state level and their support for subnational ties at the municipal and provincial levels. This foundation underpins China’s subnational engagement with India, which began simultaneously with the OBOR initiative (the forerunner to the BRI). Although subnational cooperation predates the BRI, the existing and new dyads were co-opted by the two governments as a mechanism for increasing economic opportunities and sociocultural ties. There is a high degree of social support for subnational dyads. As one survey respondent wrote, “China and India have the same disputes, but India states have strong autonomy and not all states have conflicts with China. Establishing friendly city-to-city relations are still very important.” This view was supported by another response which stated that “the local relations been China India are crucial for the overall development of bilateral relations.”

As to how these relationships should be managed, the overwhelming majority of comments on this point located subnational relations under diplomatic activities. For example, one person wrote that “Compared to [subnational) diplomacy, diplomatic relations are obviously more important, as they relate to the comprehensive relationship between the two countries.” A more nuanced view “Diplomatic relations involve national-level strategic interests and foreign policy, while local relations focus more on specific projects and grassroots exchanges. Therefore, it is not appropriate to simply compare the two.” Hence, even though these responses to our survey indicate there is a socially-located distinction between national and subnational relations with India, respondents saw these ties as falling more under the remit of the state and less generated by local interest and agendas. Whether this holds true for states beyond the BRI and its institutional ecosystem will next be explored in the case of Japan.

5.3 China–Japan subnational relations

China’s relationship with Japan has experienced frequent downturns, although not as long-running as those with India. Although the normalization of ties in 1972 marked a significant turning point, contemporary relations have often been strained due to territorial disputes over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, differing historical narratives regarding World War II, concerns over regional security dynamics, and China’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and Ukraine’s crisis (Qiu, 2006, p. 25–53; Kawashima, 2025). Although the relationship was officially reset in 2025 (East Asia Forum, 2025), the legacy of these problems creates a backdrop against which new developments can be measured. Despite these tensions, the economic relationships remain robust and highly interdependent. In 2007, China surpassed the United States to become Japan’s largest trading partner (Xing, 2017, p. 51); further underscoring a paradox where economic interests thrive alongside political frictions (Trading Economics, 2025a, 2025b). Socially, Japan was the third largest destination market for Chinese people (China Trading Desk, 2025), who were the second largest tourist cohort to visit Japan in 2024 (JTB Tourism Research, 2025). As Su et al. (2022, p. 344) observed, Chinese tourists are more sensitized to diplomatic relationships than their Japanese counterparts. Thus, in addition to returning to pre-pandemic levels of social interaction, the Chinese presence may also signal a more positive view of Japan and its people.

At the subnational level, formal subnational ties between China and Japan commenced within a year after diplomatic relations were established. Japan was the first country with which China partnered to develop subnational relations. The first dyad was between Tianjin and Kobe in 1973 as well as the ties between the two cities’ respective ports, focusing on knowledge transfer and economic development. Although the exact numbers vary, as of 2017, there were up to 381 subnational agreements between China and Japan (CLAIR, 2017).4 As Jain (2004, p. 25) found, “although cultural exchange and confidence-building measures at the grassroots level were the guiding aims of these sister-city programs, commercial opportunities were then, and are still, the other major motivation for these official couplings.” In the first two decades of the relationship, these economic ties were channeled through local governments. As the relationship matured, corporations began to involve as brokers in dyad formation. Beihai’s (Guangxi) relationship with Yatsushiro began when a delegation from Itochu Corporation visited the city and suggested that a sister-city partnership could be mutually beneficial. After a series of bilateral exchanges, the dyad was formed in 1991, with twinned foci on knowledge transfer between government departments and organizing “economic exchange delegations for local entrepreneurs to visit each other’s city.”5

All relations were not directed at economic ties. Dunhuang’s ties with Usuki in 1994 were based on their local interests in cultural (especially Buddhist) history. These cultural ties later became the basis for cooperation in city administration and agriculture, with municipal officials being sent to each other’s offices for training and proposals being developed for agricultural exchanges and working holidays. However, even in this instance, the cultural links were also tied back to the development of the local tourism industry (Interview 7). In Changchun, the local FAO was strongly supportive of bilateral educational ties. The FAO suggested that municipal authorities approach local schools interested in forming ties with foreign schools as a vehicle for building more institutionalized subnational relations (Thomas, 2024). These types of relationships suggest a high degree of variety in the motivations of Chinese actors to engage in paradiplomatic activities. Hence, although Lin and Hu concluded “that economic development is often deemed the most important task for Chinese city governments and officials” (Liu and Hu, 2018, p. 474), in the case of Japan Chinese subnational actors must also be responsive to grassroots interests.

Japan is neither a member of the BRI nor is involved in the institutional ecosystem surrounding the initiative. Despite bilateral tensions, China has more subnational ties with Japan than with any other neighboring country. Although this incongruity may suggest an operational distinction between diplomatic tensions and paradiplomatic practices, the survey respondents suggest that there remains a degree of overlap between the two. Of the three countries, Japan was the only country where the majority of respondents (63.2%) considered its partner government unfriendly toward China. Although the Japanese people were viewed in a more positive light than their government, 50.2% of the Chinese respondents still viewed them as unfriendly. These findings accord with those from the 2024 CIOS survey, which found that Chinese people held a “very unfavorable” view of Japan (CISS, 2024, p. 10). Similarly, the Genron NPO (2024, p. 11–12) 2024 Joint Public Opinion Survey found that 87.7% of Chinese held a relatively poor impression of Japan, whereas 76.0% viewed the bilateral relationship as poor or relatively poor. 75.0% of the Chinese respondents also felt that the relationship was likely to deteriorate or somewhat deteriorate in the future. Given this high degree of negative sentiment, it is reasonable to ask what perceptions Chinese people have regarding diplomatic or paradiplomatic efforts to maintain or improve their relationships.

Diplomatically and economically, our respondents indicated that Japan remained important to China, but far less so than for any other country surveyed. Only 56.8% felt that Japan was diplomatically important to China, with a similar number (59.8%) agreeing that Japan was economically important for China’s development. These responses are at odds with China’s bilateral diplomatic engagement with Japan, trilateral relationship with South Korea, regional relationship via ASEAN+ and other forums, and international relationship with the United Nations and other bodies. These responses do not match the economic realities of the bilateral relationship. Economically, Japan is China’s second-largest trading partner, with two-way trade estimated at US$300 billion. Both countries are the third largest overseas sources of foreign investment (MOFA, 2024). In 2025, both countries held the seventh high-level economic dialogue, agreeing to deepen economic relations across a range of supply and investment areas (Fan and Xing, 2025). This disjuncture between public opinion of ties and the reality of bilateral ties is further reflected in the perceived importance of social and cultural exchanges in the overall relationship, with only 55.1% agreeing that such exchanges are important. Despite this lukewarm perception, 2.4 million Chinese visited Japan, making mainland China the third-largest source of tourists, although this was down from nearly 9.6 million who visited in 2019 before the pandemic (MOFA, 2024). Further, in December 2024, the two countries signed ten new agreements to deepen youth exchanges, education cooperation, tourism, and sports, as well as increase opportunities for subnational government cooperation (Xinhua, 2024).

Given the negative overall sentiment and the lackluster recognition of the importance of diplomatic, economic, and socio-cultural ties, it is unsurprising that subnational ties were not seen as being particularly important to the relationship. Despite the array of sister city, province, and other dyads between the two countries, only 55.9 percent of respondents believed that such ties were important. On the one hand, sentiments such as “Do not expand the bilateral relations of both countries. Do not need to develop cultural exchange and economy, Japan will always be an enemy of China,” “The local relationship between China and Japan is not important in the first place and should be reduced” and “Sino-Japanese relations should not continue, nor should the economic and cultural aspects.” On the other hand, exemplars of more positive assessments included: “The local relations between China and Japan should continue to expand. Economic cooperation, political interaction, cultural exchange, and historical issues all are beneficial,” “The friendly and dynamic local relations between China and Japan should continue and expand. Complementing diplomatic relations, local exchanges are of great significance in enhancing people’s well-being and promoting cooperation in various fields,” and “China-Japan local relations are of great significance and should continue to expand.” A number of respondents also firmly placed the subnational ties with Japan as subordinate to diplomatic endeavors: “Compared to diplomatic relations, local relations are not important,” “The local relations between China and Japan continue to expand and improve, with diplomatic relations being more important,” and “Economic, social, cultural, and diplomatic relations are more important in local relations.”

Japan is unlikely to pursue ties with the BRI institutions at any point in the future. Since the two countries recognized each other in the early 1970s, Japan’s relationship with China has shifted from being a strong supporter of China’s development to one characterized by a heightened sensitivity to territorial and other issues. The contradiction between the state of diplomatic ties and the extent of subnational partnerships may suggest that a surface-level distinction can be drawn between the two modes of engagement, although the longer history of China–Japan subnational ties implies that this dyad will contain far more legacy ties compared with the other two cases. With respect to the views held by the respondents of the Japanese government and people, the majority viewed them as unfriendly. Nonetheless, data show that Japan is still regarded as an important diplomatic, economic, and sociocultural partner to China. Although the levels of support were lower for Japan than those for the other two cases, they were still more positive than the general view of Japan. This may suggest that even though our respondents regarded Japan as an unfriendly country toward China, they observed value in engagement. This conclusion is supported by the fact that 55.9% of the respondents viewed subnational ties as important. Generally, the difference between perceptions of the Japanese government and the perceived importance of subnational ties may also imply a socially held distinction between the two levels.