- Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands

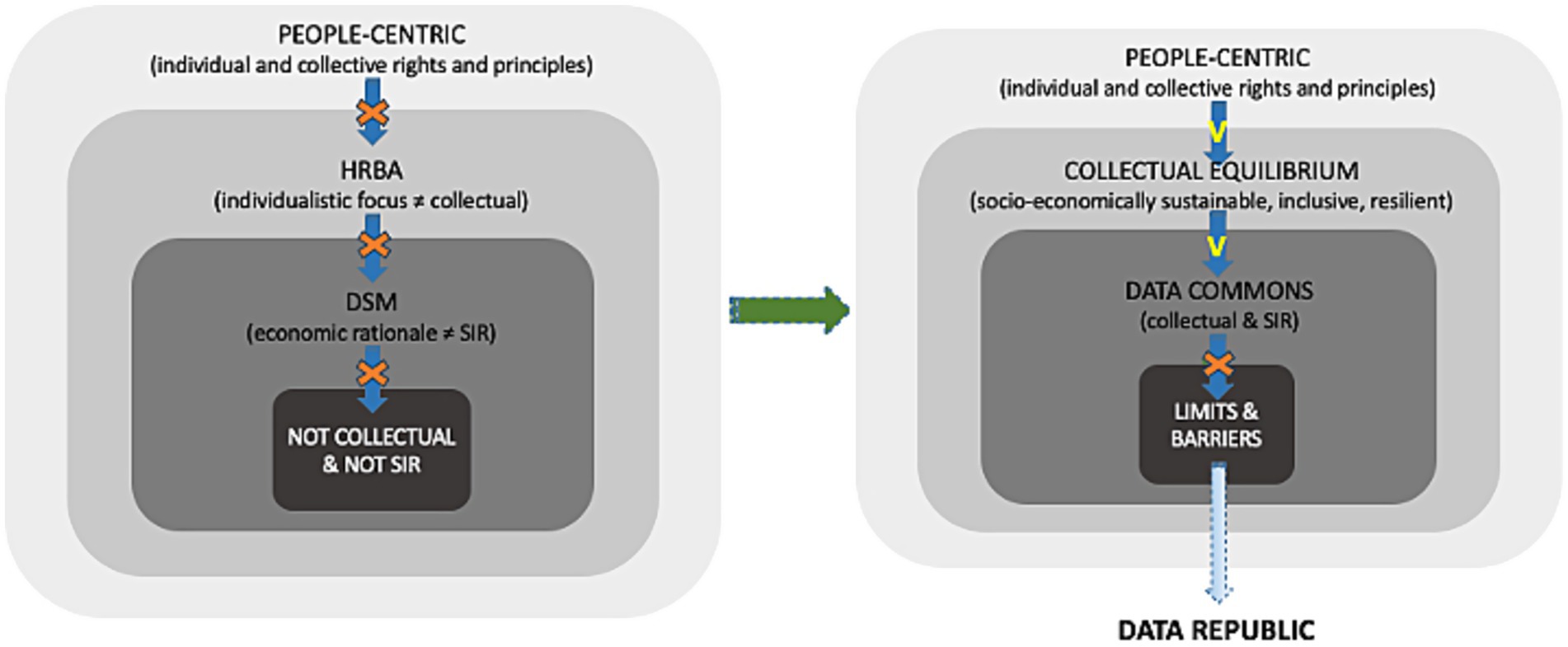

In various official documents, the European Union has declared its goal to pursue a “people-centric” digital transformation. While fuzzy in its formulation, this generally entails the defense of individual rights alongside principles such as economic competitiveness, social inclusiveness, digital sovereignty, and environmental sustainability. Hence—we claim—“people-centric” embeds and demands a “collectual” (collective + individual) equilibrium between individual and collective rights and principles. Concretely, we draw on literature to operationalize such an equilibrium in terms of socio-economic sustainability, inclusiveness, and resilience (SIR). From here, we show that the EU’s current human rights-based approach (HRBA) and its emerging digital single market (DSM) maintain an individualistic focus and economic rationale which fail to be collectual and SIR. We identify data commons as a promising collectual and SIR regime for governing the digital transformation. By addressing current barriers and limitations of data common initiatives, we conceptualize the Data Republic as a theoretical setup that can systemically tackle these limitations and barriers to provide a new way for pursuing a “people-centric” digital transformation in the EU.

1 Introduction

When it comes to governing the digital transformation, the European Union’s (EU) digital strategy aims to pursue a “people-centric” approach. This approach remains quite fuzzy in its characterization across documents, but in principle, it aims to safeguard human and data subjects’ rights while balancing economic competitiveness with social inclusiveness, digital sovereignty, and environmental sustainability (European Parliament and Council, 2016, 2019, 2020a,b, 2022a,b; cf. also European Commission, 2022b). As such, the EU’s “people-centric” approach emphasizes both the individual and collective dimensions of the digital transformation—or what we call a “collectual” (collective + individual) equilibrium—insofar as “people-centric” is concerned as much with the rights of the individual as with principles pertaining to society as a whole.

Currently, however, the EU’s digital strategy—based on a human rights approach (HRBA; European Parliament and Council, 2012a) and realized through its emerging Digital Single Market (DSM; European Commission, 2022a)—maintains de facto an individualistic focus and economic rationale only that cannot enact a “people-centric” digital transformation. Indeed, such focus and rationale fail to properly enable the achievement of those collective principles, such as social inclusiveness, digital sovereignty, and environmental sustainability, which cannot be reduced to individuals’ rights or economic value.

Beyond that, “people-centric” and/or its “collectual equilibrium” lack a proper conceptualization and operationalization. Therefore, in this article, we first provide such conceptualization and operationalization. Notably, we draw on literature (Pope et al., 2004; Bond et al., 2012; Purvis et al., 2019; Troullaki et al., 2021) to advance that, in order to be collectual, the digital transformation shall be socio-economically sustainable (S), inclusive (I), and resilient (R), i.e., “SIR.” Second, we delve into the data commons as a regime—alternative to the market and the state—which does configure a collectual SIR management of digital initiatives,1 i.e., suitable for a “people-centric” digital transformation. However, literature also shows that current data commons initiatives still face shortcomings in terms of structural limits and substantial barriers (Balestrini et al., 2017; Mulder and Kun, 2019; Calzada and Almirall, 2020). Therefore, we will make the case for the Data Republic as a theoretical setup that can systemically tackle these shortcomings and realize a proper “people-centric” digital transformation for the EU (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Data Republic as a theoretical setup enacting a sustainable, inclusive, and resilient (SIR) digital transformation. Left: the current EU implementation; right: our proposal. The concentric squares go from the abstract to the concrete, i.e., from principles, and approaches to regimes and their identified limits and barriers.

The article is organized as follows: Section 2 unpacks the notion of “people-centric” by conceptualizing its underpinning collectual equilibrium and operationalizing it in terms of socio-economic sustainability, inclusiveness, and resilience (SIR); Section 3 explores the EU’s digital strategy with regard to its HRBA and the emerging DSM, highlighting their individualistic focus and economic rationale which make the whole strategy not people-centric; Section 4 introduces the data commons as a collectual SIR regime for managing digital initiatives, while also highlighting current structural limits and substantial barriers; Section 5 builds on this analysis by outlining the features of the Data Republic as a theoretical setup that can help systemically overcome data commons’ limits and barriers and enact a people-centric (i.e., collectual SIR) digital transformation; Section 6 concludes pointing out limitations of the present discussion and identifying further research.

2 Laying the ground: defining concepts, unpacking tensions

2.1 Pursuing a “people-centric” digital transformation

In various official documents, the European Union has declared its goal to pursue a “people-centric” digital transformation (European Parliament and Council, 2016, 2019, 2022a,b, 2020a,b). The most relevant document in this regard is the Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles (DDRP) released by the European Commission (2022b) at the end of 2022. Notably, the DDRP defends “a European way for the digital transition, putting people at the center.” While under the notion “people-centric” falls a broad and somewhat fuzzy understanding of how data-driven technologies and services should be regulated, de facto “people-centric” refers to the attempt to strike a balance between, on the one hand, the safeguard of individuals and data subjects’ rights and, on the other hand, the realization of principles such as economic competitiveness, social inclusiveness, digital sovereignty, and environmental sustainability. More specifically, what the DDRP does is to pin down six principles: (1) preserve people’s rights; (2) support solidarity and inclusion; (3) ensure freedom of choice; (4) foster democratic participation; (5) increase safety, security, and empowerment of individuals; and (6) promote sustainability. For the present discussion, it is noteworthy that these principles are equally split between a half (1, 3, 5) focusing on the individual and the other half (2, 4, 6) pertaining to society as a whole. In this regard, the DDRP seeks a balance between the individual and collective dimensions affected by the digital transformation, focusing as much on the fundamental rights of the single person as on population-level principles irreducible to the former nor to their sum. In other words, as a compass for the EU’s digital strategy, the DDRP indicates that the digital transformation should keep in sight what we call a “collectual” equilibrium (cf. also Calzati and van Loenen, 2023b). Yet, a proper conceptualization and further operationalization of such an equilibrium remain two open issues.

2.2 Outlining a collectual equilibrium

A proper conceptualization of the collectual equilibrium is based on three interdependent ideas: (1) a systemic standpoint; (2) the co-dependency between individual and collective dimensions; (3) their balance as an ongoing process. Concerning the first idea, to speak of collectual equilibrium entails avoiding prioritizing a priori either the individual or the collective and rather regarding the part-whole dichotomy as systemic. This means that, while there might be policies and programs targeting either side, the part-whole dichotomy shall be conceived and tackled in an integrated manner.

This links to the second idea. To claim that the notion of “collectual” entails the co-dependency between individual and collective dimensions implies to regard these dimensions as not only connected but mutually implicated. Concretely, at stake is the need to approach the digital transformation as a complex sociotechnical process of actors and factors constantly reshaping their own internal power relations. This means, in other words, to consider the digital transformation as a self-organizing process (cf. Bettencourt, 2015) that thrives through ongoing adjustment to contingent conditions and interventions.

Here, then, comes the third idea. The collectual equilibrium is never given once and for all; instead, it demands to be repeatedly finetuned. Put differently, the collectual equilibrium is an exercise of balance to be realized on a rolling and contextual basis. While from an individualistic perspective this exercise might reflect the composite diversity of all actors’ rights, interests, and principles, from a collective perspective this same exercise might demand the synthesis and hierarchization (not necessarily the sum) among actors’ rights, interests, and principles. As we will expand in Section 5, these ideas of systemic codependency and ongoing balance are best reflected in the theoretical setup of the (Data) Republic, which draws upon the origins of the res publica as the management of the public good by citizens and for the citizenry, as well as on current work on “radical republicanism” (Hoeksema, 2023) as a structural approach to sociotechnical inequalities. Next, we will explore how such an exercise of balance can be operationalized.

2.3 The collectual equilibrium as socio-economically sustainable, inclusive, resilient

To achieve a collectual equilibrium it is necessary to move away from prioritizing a priori either certain actors (e.g., private or public, and their rights), principles (oftentimes, economic competitiveness over social inclusion or environmental sustainability), or factors (mostly legal and technical specifics over other skills and competences) to rather enact a systemically balanced arena (cf. Rochel, 2021 on fairness as a principle “linked to procedural dimensions of a balancing exercise involving rights and interests”) whereby actors, factors, as well as rights and principles, are tackled as co-dependent aspects of a whole emerging sociotechnical process. A good starting point to operationalize such a collectual equilibrium is the work done on sustainability.

Literature (Purvis et al., 2019) shows that the concept of sustainability lacks a shared scientific conceptualization and, mostly through gray documents, the concept has come to include three dimensions: economic, social, environmental. While it is easier to assess economic sustainability, much less so is to assess social and environmental sustainability. This is because these two latter dimensions escape a clear-cut econometric framing, involving non-quantifiable values, externalities, and rebound effects which are not easy to model. Yet, over the last 20 years, the field of sustainability science and sustainability assessment have emerged to compensate for the theoretically thin and economic-centric understanding of sustainability (Pope et al., 2004; Bond et al., 2012; Troullaki et al., 2021) with the goal to rethink sustainability in more holistic terms and explore ways toward its balanced pursuit.

It is especially the possibility of resorting to a transdisciplinary approach (Nicolescu, 2005; Troullaki et al., 2021) that resonates well with the idea of collectual equilibrium. According to Troullaki et al. (2021), transdisciplinarity can supply “a systemic approach for understanding dynamic interactions of complex social-ecological systems; normative sustainability principles, visions, and values; the integration of interdisciplinary and non-scientific knowledge, creating strong links with the social context and engaging stakeholders throughout the process for knowledge co-production.” This quote is relevant in at least two respects. First, it points out the importance of maintaining a systemic standpoint and regarding social and environmental dimensions in an integrated manner. This implies that no proper sustainability can be achieved by either isolating its three dimensions or by prioritizing economic performance over the others. For our discussion, it means that digital initiatives can be collectual only to the extent they are socio-economically sustainable.

Second, the passage above calls for the integration and synergy between different stances of institutional and non-institutional stakeholders. In this respect, literature on the governance of tech innovation (Schneider, 2020; Calzati and van Loenen, 2023a) has already supplied evidence that both market-centric, corporate-driven approaches (Kummitha, 2020; Kalpokas, 2022) and state-centric, top-down approaches (Sun, 2007; Fu et al., 2016; Zeng, 2017) hinder the fostering of such integration and synergy. On the one hand, while a market-centric, corporate-driven approach might favor a competitive landscape where innovation and economic success go hand in hand, it also shows drawbacks especially due to the lack of contextual adaptability of the developed technologies (Kummitha, 2020), as well as their limited social inclusiveness (Kalpokas, 2022). On the other hand, a state-led, top-down approach might help achieve mid- to long-term techno-economic targets while maintaining social stability (Au and Kuuskemaa, 2019). Yet, this approach too shows drawbacks, with bureaucracy stiffing innovation (Sun, 2007) by creating a bottleneck for small and medium enterprises compared to big state-owned firms (Fu et al., 2016; Zeng, 2017).

To achieve integration and synergy, collectual digital initiatives shall be inclusive. With this term, we refer, on the one hand, to cultural and sociodemographic factors that might be discriminated against by focusing on (data) subjects as individuals (Theilen et al., 2021). In this respect, inclusion entails the fostering of mechanisms to make the digital transformation as representative as possible of the diverse subjects in the population. On the other hand, inclusion refers to the heterogeneous galaxy, as a collective, of institutional (both public and private) and non-institutional stakeholders (e.g., NGOs, data intermediaries, data altruism organizations, local communities) informing any digital initiative.

Last, as a complex sociotechnical process, a collectual digital transformation requires as much technical infrastructures and legal frameworks as non-technical competencies and skills. While technical and legal specifics remain fundamental, they need to be embedded into a broader sociotechnical frame able to account for and value an array of non-technical factors. In this respect, digital initiatives shall be resilient. A system is resilient to the extent it can withstand major disruptions while keeping running and/or when it can recover within an acceptable time. More precisely, resilience (cf. Ponti et al., 2024) refers here to issues including, but not limited to (a) the exploration of the links between top-down and bottom-up stances; (b) the establishment of checks and balances among actors and their interests; (c) the favoring of organizational change especially in the public sector (including data literacies and tech-legal capabilities).

Translating this in the context of the EU’s digital strategy, this entails that (i) the creation of economic value shall be pursued by maintaining a societal outlook (Purtova and van Maanen, 2023); (ii) the interests and rights of all involved actors are accounted for on equal footage and negotiated, based on collective principles, on a rolling contextual basis (Ansell and Torfing, 2021); (iii) technical barriers are tackled together with/through the unlocking of non-technical enablers (Kapoor et al., 2015). In this respect, a collectual equilibrium is the conditio sine qua non for realizing sustainable, inclusive, and resilient (SIR) digital initiatives. The extent to which the EU’s current digital strategy can realize that is contentious.

3 The European Union’s current digital strategy

3.1 The individualistic focus of the EU’s approach

In December 2012, the European Parliament and Council (2012a), released the Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR). The CFR contains six chapters for a total of 50 rights. While the “solidarity” chapter includes rights such as “social assistance,” and “environmental protection,” which do maintain a collective-by-default outlook, most of the rights enlisted are individual rights, meaning that they relate to the single individual.

Today, the CFR constitutes the polar star of the human rights-based approach (HRBA) pioneered by the EU when it comes to governing the digital transformation. The rationale behind such an approach is to tackle the adversary effects of data-driven technologies by protecting citizens from the potential infringement of their fundamental rights (Brown, 2019; Davis, 2020). For instance, human rights can be either used as a normative framework (Yeung et al., 2020) or inscribed by design into the development of data-driven technologies (Aizenberg and Van Den Hoven, 2020). While such an approach is certainly pivotal for preserving individuals’ integrity before the digital transformation, recent studies have shown the limits of a rights-based only approach to the digital transformation (Smuha, 2021; Viljoen, 2021). This is so because the underpinning focus on the individual of the HRBA risks overlooking population-level effects of the digital transformation (Viljoen, 2021) and potential societal harm (Smuha, 2021) which cannot be reduced to the sum of individuals and their rights. For instance, Viljoen (2021) notes that the individualistic focus behind the HRBA does not account for the relational nature of data and the consequent trade-off effects that data re-use involving two subjects might have on unaware third parties. Similarly, Smuha (2021) suggests taking inspiration from environmental law for tackling potential societal harms caused by the digital transformation—such as the erosion of the legitimacy and functioning of the rule of law—which can be neither accounted for nor mitigated by the current individualistic focus. Hence, to the extent to which the HRBA constitutes the fundamental baseline to citizens’ autonomy, it might not be sufficient to protect Europeans as a whole.

3.2 Data subjects as consumers

The same individualistic focus is also at the basis of the legal understanding of data protection, data subject, and their rights, as encapsulated in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (European Parliament and Council, 2016). Almost 10 years into its implementation, a growing number of studies (Woulters, 2018; Finck and Pallas, 2020; Valli Buttow and Weerts, 2022) have explored the strengths and weaknesses of the GDPR, especially with concern to the tensions arising at the intersection of the protection of personal data and data subjects’ rights. The GDPR identifies a data subject as “an identified or identifiable natural person” and the law applies to personal data only, defined as “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person.” From here, the GDPR, on the one hand, requires that forms of anonymization are set in place to guarantee that the processing of personal data does not infringe on data subjects’ privacy, while, on the other hand, it does strengthen data subjects’ rights—e.g., right to access to personal data; right to rectification; right to erasure; right to portability—enabling more control over the processing of their personal data.

Notwithstanding, respectively, the effective difficulty of anonymizing data (Finck and Pallas, 2020) and the concrete limited empowerment of data subjects before third-party data processors (Woulters, 2018), for the present discussion it is worth emphasizing the individualistic focus on which the GDPR rests. The goal and scope of the GDPR is to protect individual rights, chiefly regarding data subjects as consumers and/or producers of data (Valli Buttow and Weerts, 2022). In fact, the EU’s legislation on data processing formalizes the HRBA’s individualistic focus to be subservient to the economic rationale of the DSM.

Research that signals the limitations of this individualistic focus, as well as ways to rebalance it with more attention to the collective, is already present. Lane et al. (2014), for instance, map the epistemological, ethical-legal, and practical boundaries to do public good with and through big data, while preserving data protection. Taylor et al. (2016), instead, discuss the idea of “group privacy” and the need to redesign current legal frameworks, starting from the acknowledgment that data-driven technologies address and impinge on groups as collectives to be tokenized beside and beyond individuals. It is the tension between an individual and a collective dimension of the digital transformation that is at stake, with the consequent need to define more clearly when data shall be processed in the public interest, that is, above and beyond individual rights (Bell et al., 2019; cf. Calzati and van Loenen, 2023a).

3.3 The European digital single market’s (DSM) economic rationale

Meanwhile, recent EU documents (European Commission, 2021, 2022a,c) have laid the ground for the establishment of an EU’s digital single market (DSM), as the arena where its digital strategy will play out. Elsewhere (Calzati and van Loenen, 2023c), we have already unpacked the criticalities of the envisioned DSM, on the one hand, identifying the bundling between technology, (proprietary) law, and economic value and, on the other hand, denouncing the lack of designed mechanisms to ensure shared accountability and trust in/through the DSM. Below, it suffices to summarize that, by enacting the HRBA individualistic focus, the DSM is envisioned as a technically secure and legally compliant system revolving around an economic rationale for the profitable sharing of data.

For instance, the Digital Market Act (European Parliament and Council, 2022b), as part of the DSM, states the aim to “create a safer digital space in which the fundamental rights of all users are protected” as well as “to establish a level playing field to foster innovation, growth, and competitiveness.” In a similar vein, the 2021 Digital Europe Programme (European Commission, 2021) speaks of “the importance of building a thriving ecosystem of private actors to generate economic and societal value from data, while preserving high privacy, security, safety and ethical standards.” Beyond that, the same document specifies how the DSM is understood as a set of necessary-sufficient infrastructures in the form of a “vendor-neutral technical architecture and reference framework” with the goal to promote an “agile and future-proof revenue model to cement long-term commercial viability, while ensuring unbiased competition.” Overall, from these path-laying documents, emerges neatly the extent to which the enactment of a European DSM is conceived as a corporate-driven (rather than revolving around collective interest), consumer-oriented (rather than focused on citizens), and competition-based arena (rather than enticing collaborative synergies).

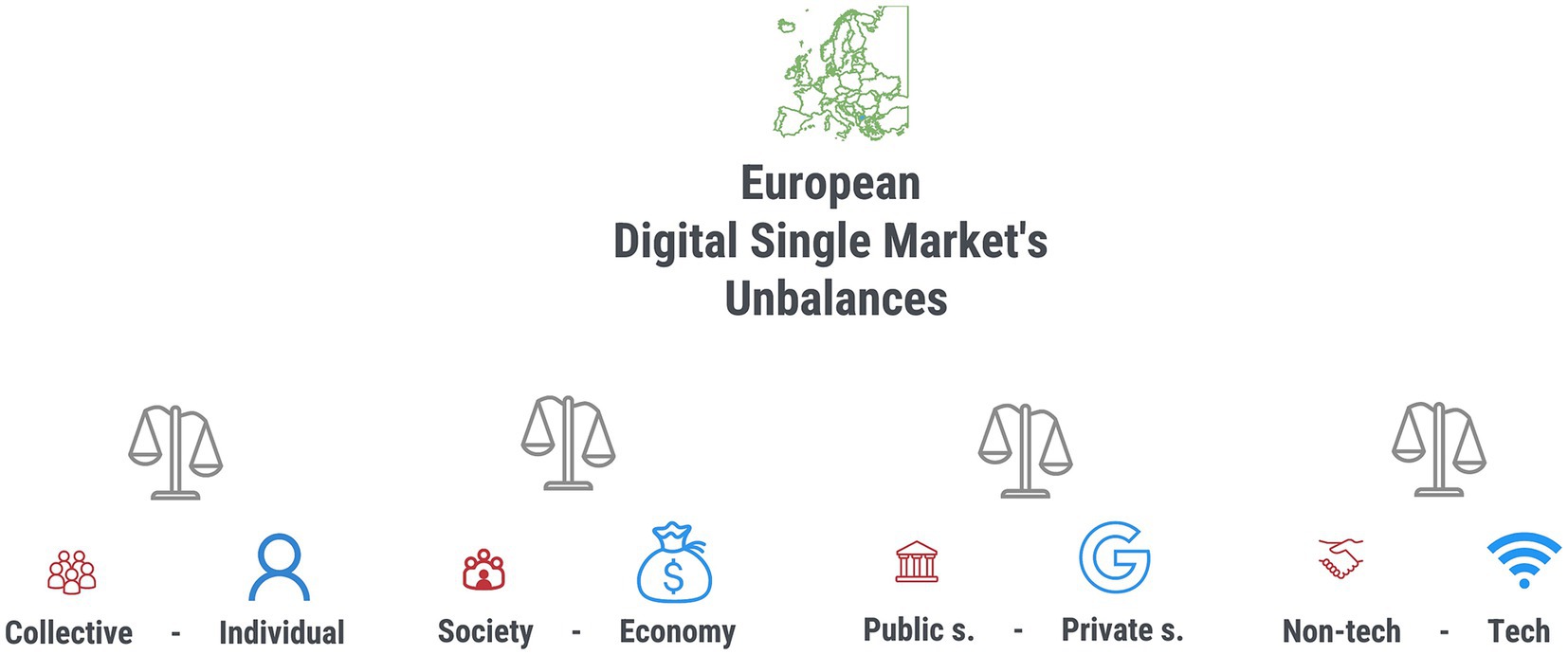

As such, the DSM concretizes an unbalanced arena (Figure 2) insofar as it tends to privilege: (1) individual subjects (e.g., consumers) over the collective (e.g., citizenry) as well as economic over social value; (2) private actors (e.g., companies) over the public sector (e.g., municipalities, governmental bodies) and non-institutional actors (e.g., grassroots initiatives); (3) technical-legal aspects (e.g., secure data sharing and GDPR-compliance) over non-technical aspects (e.g., literacies, trust, governance).

Overall, it is possible to advance that, due to the individualistic focus and economic rationale underpinning the HRBA and the DSM, the EU’s current digital strategy fails to strike a collectual equilibrium so that its realization is currently not SIR: (1a) not socio-economically sustainable; (2a) not inclusive; (3a) not resilient. Next, we will explore how to counterbalance the present situation, by looking at data commons as a regime for managing digital initiatives which is—we argue—collectual and SIR.

4 Data commons

4.1 A collectual sustainable inclusive and resilient (SIR) regime

Today, data commons initiatives (Dulong de Rosnay and Stalder, 2020; Calzati and van Loenen, 2023a) aim to counteract and/or repurpose the centralized ownership and use of data—either by tech companies or states—to foster sustainable collective data practices (Morozov and Bria, 2018). According to Bloom et al. (2021), “data commons is a system of stewardship through which data resources are sustainably governed through collaboration among stakeholders.” In principle, then, the data commons identifies a regime for managing resources that: (1) maintains a focus on the system, striving toward socio-economical (and environmental) sustainability; (2) considers all nodes and edges of the system as integral and necessary to the commoning flourishing (i.e., inclusive), either on a peer-to-peer or structured basis; (3) is based upon forms of self-organization open to change and adaptation (i.e., resilient), which are inherent to the system. The data commons, then, configures a kind of management of digital initiatives that is non-appropriative by default, collaborative by design, and collective in its outlook (Calzati, 2022).

Scholars (Zygmuntowski et al., 2021) have also hinted at the promise of designing an EU-comprehensive commons-based digital governance. Bloom et al. (2021), for instance, designed commons’ principles for digital initiatives in terms of access, management, and adjudication of resources. However, their standpoint remains anchored to an economic rationale of data-as-resource which prevents an effective collectual equilibrium (cf. Sanfilippo and Frischmann, 2023). Decisive, in this regard, becomes the establishment of the boundaries of data commoning as a complex sociotechnical process—and it is on this point that data commons initiatives still present structural limitations and substantial barriers.

4.2 Exploring data commons initiatives in Europe

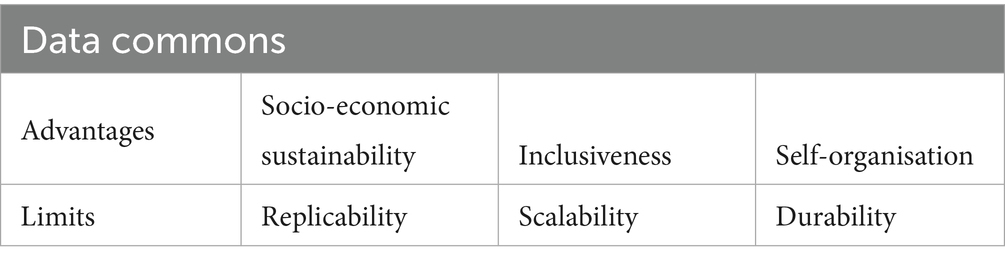

Over the last decade, various initiatives (cf. Morozov and Bria, 2018; de Lange and de Waal, 2019; The New Hanse Project, 2023) have emerged around Europe enacting a commons-inspired approach to data and digital infrastructures. These initiatives do provide evidence of successful data-commoning practices that tackle the creation of social and economic value conjointly while promoting inclusiveness and self-organization. At the same time, however, these initiatives betray three major structural limits (Table 1 below summarizes the advantages and limits of data commons initiatives):

1. Replicability (cf. Balestrini et al., 2017). Currently, data commons initiatives lack an operational systematization of the organizational and cultural factors that can favor the transposition of commons-inspired initiatives across different contexts.

2. Scalability (cf. Calzada and Almirall, 2020). As they tend to have a local dimension by default, these initiatives lack clear mechanisms to scale up and wide.

3. Durability (cf. Mulder and Kun, 2019). Based on the previous two points, commons-inspired initiatives also lack consolidation over time.

Note that these limits are structural precisely because they are currently inherent to the commons as a SIR regime. In other words, they emerge (to various degrees) across the literature discussing the commons as an alternative regime to state and market control of resources. At the same time, however, these structural limits shall not be regarded prescriptively. Indeed, these limits do not identify necessary-sufficient preconditions to achieve collectual SIR digital initiatives. As a matter of fact, non-prescriptiveness is key for maintaining a transdisciplinary standpoint, as discussed above. Instead, these limits shall be regarded as descriptive in nature, meaning that (1) they warrant heuristic flexibility; and (2) the very exploration of their suitability is under scrutiny when applied to digital initiatives.

4.2.1 Structural limits

Overall, when it comes to tech innovation, the quadruple helix—public sector, private sector, academia, and citizens—is usually regarded as the necessary-sufficient setup for fostering inclusive initiatives. Yet, such a setup does not account for a whole galaxy of non-institutionalized actors who do contribute to inform digital initiatives, among others: NGOs, non-profit organizations, data intermediaries, data stewards, data altruism organizations, data collaboratives, data cooperatives, grassroots practices. This heterogeneous galaxy is increasingly acknowledged—yet, not operationalized—by the EU (cf. European Parliament and Council, 2020b). As far as scalability is concerned, according to de Lange and de Waal (2019), there is an enduring mismatch between top-down and bottom-up stances, meaning that the logic of institutions and the fluid assemblages of civic initiatives are difficult to reconcile. In fact, in terms of their durability, commons-inspired initiatives usually emerge at the felicitous convergence of various conditions including political support, tech-legal expertise in public organizations, funding, and engaged communities. This felicitous convergence can fade away at any time, as soon as one of these conditions disappears (Mulder and Kun, 2019; Wolff et al., 2019; Balestrini et al., 2017). This defection also applies to the replicability of commons initiatives, which have been so far negatively impacted by the lack of what Ludwig et al. (2018) call “infrastructuring” (Ludwig et al., 2018), that is, the meta-level process enabling the collective to take over the shaping of their own infrastructures and services once they have been initiated.

However, we do not navigate in the void. One of the most consistent examples of data commons initiatives comes from Barcelona (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2019). In 2016, the Catalan municipality launched a “new social pact on data” composed of various initiatives, among which the establishment of data commons regimes allowing citizens to own and keep control over their data. In the words of Morozov and Bria (2018), the goal was to make good use of the power of data through “an ethical and responsible innovation strategy, preserving citizens’ fundamental rights and information self-determination.” Concretely, the experiment in Barcelona rested on a double-sided rationale: on the one hand, the idea that technology should be at the service of democratic participation; on the other hand, the principle that technology itself should be democratized, for instance via the adoption of open source standards and privacy-sensitive tools and platforms for direct democracy (e.g., the platform Decidim enabled the co-production of the Municipal Action Plan). More granularly, the initiative established a chief technology and digital innovation officer as an executive role, endowed with the task of implementing the new digital plan based on a series of projects aimed at: (1) the digitalization of the city council’s operations; (2) the support of social innovation; (3) the digital literacy of citizens. Although still presenting organizational hindrances, as the initiators of the initiatives amply discuss (Monge et al., 2022), Barcelona’s case teaches that the commons can be applied to data and digital infrastructures, provided that this regime is inscribed into a broader sociotechnical picture. It is in this regard that, in the next section, we will map the preconditions for such a sociotechnical picture onto social and technical barriers.

Learning from and expanding upon the experience in Barcelona, most recently the city of Hamburg was the stage for experimenting with commons-inspired governance of urban data in the public interest, with a focus on micro-mobility. The initiative aimed to tackle the barriers that currently prevent the sharing of data collected through public infrastructures—e.g., roads—among diverse stakeholders, especially private companies. The authors of the final report (The New Hanse Project, 2023) note that “the legislator might even create a universal data sharing law that gives anybody access to all types of data, given that the data holder does not have to bear any costs and their further interests are respected (especially in keeping their business secrets).” These words configure a systemic reworking of the current data-sharing paradigm. While today private companies have near-exclusive ownership of the (users’) data collected and generated through their services, an urban data commons regime entails the sharing by default of the data in the public interest, to the extent to which these data make use of public spaces and infrastructures, and unless special justifications apply. In so doing, this approach pushes the sharing of data well beyond recent EU legislation, which recognizes the need for the public sector to get public access to data owned by private companies in emergency situations.

Eventually, the initiative in Hamburg was deemed successful, although the final report does acknowledge enduring bottlenecks. On the one hand, “the process of finding a functioning legal setup for the transfer of data was fairly complex.” This signals the difficulty of operationalizing a data commons regime beyond the current legal framework—which self-reinforces an individualistic focus in terms of rights and business models—toward a collectual legal frame. This difficulty is mapped below onto the identified legal barriers.

On the other hand, the report notes that out of the 13 (mostly private) organizations invited to participate in the project, only two agreed to do so, with the others pointing at “lack of resources, lack of interest in the broader topic of B2G data sharing, existing involvement in other initiatives, as well as poor experiences of working with cities” as reasons for not participating. These findings point to organizational and cultural resistances by, within, and across institutional actors which demand integrated strategies to be tackled (mapped onto institutional barriers below).

Overall, the authors of the report conclude that:

Engaging in an innovative data project proved to be challenging. (…) A key reason for this was that data governance is a cross-departmental issue that requires mediation among various city stakeholders with sometimes divergent perspectives. A common vision, clear roles and responsibilities among the different stakeholders and regular check-ins at the working level were essential to navigate this complexity and propel the project forward.

This passage encapsulates well one of the key tenets of the present article, notably the need to inform and guide digital initiatives with/through a collectual equilibrium that identifies roles and rules to systemically represent the interests and rights of the actors involved, as well as mechanisms to adjudicate, on a rolling case-by-case basis, situations where conflicts among actors and/or principles might arise (issues that are mapped on to the governance barrier below).

4.2.2 From structural limits to substantial barriers

By integrating the lessons coming from these initiatives and related literature, it is possible to map the current three structural limitations of data commons onto five substantial barriers:

a. Legal

b. Technical

c. Social

d. Institutional

e. Governance

Concerning the legal barrier, the complexity of defining a commonly shared framework suggests translating best practices into replicable and scalable formats. This means working toward a templatization of the shared legal framework(s), intended as a process that is codified enough to be transposed across different European contexts and able to harmonize local, national, and European levels, as well as flexible enough to accommodate new pieces of legislations and contingent needs. This, in turn, might allow for a consolidation of data commons initiatives over time, as the legal templatization would be more easily adopted at the institutional level. As noted in The New Hanse Project’s (2023) report, “the reasons why processes are not scaled are not technological but lie in the difficulty to properly define them, so they can (later) be supported by technology, evaluated and enhanced.” Therefore, in order to enable regulatory harmonization across scales and easier replicability across contexts, at stake is a value-laden prioritization of jurisdictional roles and clear mechanisms of responsibility adjudication among actors.

Concerning the technical barrier, literature highlighted the need to enhance infrastructural interoperability, which is the precondition for smooth(er) data sharing among diverse stakeholders and for any initiative aimed at collectivizing data in the public interest. The Interoperable Europe Act (European Parliament and Council, 2024) envisions an EU-scale framework to promote the secure exchange of data based on shared digital solutions to support trusted data flows. From here, it is advisable to favor open source as the key not only for greater transparency and accountability but also for ensuring a virtuous feedback loop between public funding and public data and infrastructures. More broadly, this links to the fostering of a proper European digital polity, based on the establishment of a technical backbone that can favor the smooth sharing of data internally to the EU, as well as symmetric and adequacy-based legal rules with external geopolitical actors (Calzati, 2023; Voss and Pernot-Leplay, 2023).

The social barrier has to do with the fostering of inclusive digital initiatives that gravitate around the needs (as well as benefits from the contributions) of a cognizant citizenry as a collective. Concretely, this means not only increasing awareness in citizens about what can be done with and through data but also enhancing data literacies in the whole citizenry, as a fundamental enabler to the very possibility of fueling grassroots digital initiatives (Mergel et al., 2018). Indeed, research (Wolff et al., 2019) shows that digital means can help communities gather around shared concerns and proactively advance data-centered solutions. However, data literacies are still limited in the population, requiring initiatives to systemically tackle such scarcity. On this point, already in 2019, the document on Trustworthy AI (European Commission, 2019) of the EU mentioned the need to “encourage Member States to increase digital literacy through courses across Europe.” This desideratum, however, has not found yet a concrete systematization nor an effective implementation, as it remains up to member states to do so. In this respect, data literacies represent a long-term goal for any digital initiative that aims to finetune with the concrete instances of citizens, as well as to empower the whole citizenry. More concretely, this entails the exploration of up-to-date data literacy curricula that blend technical and ethical dimensions related to the collection, sharing, and (re)use of data, as well as cater to different audiences, both across all stages of school education and involving lifelong learning groups.

The institutional barrier concretizes in (a) the limited operationalization of the heterogeneous galaxy of actors informing digital initiatives; and (b) the current lack of a consolidated process of stewardship able to facilitate the link between institutionalized and non-institutionalized actors and citizens (Calzati and van Loenen, 2023a). To tackle these points would facilitate the transition to a system that is socio-economically sustainable. Concerning (a), the Data Governance Act (European Parliament and Council, 2020b) identifies data altruism organizations, data cooperatives, and data intermediaries as emerging actors. Yet not only does such identification lack concrete operationalization, but these actors do not exhaust the diversity informing the digital galaxy, leaving out, for instance, non-institutional stakeholders. In connection to that comes point (b), notably the need to foster figures and processes that can finetune between different stances. The Data Governance Act (European Parliament and Council, 2020b) already speaks of the need—currently unmet—“to put structures in place to support public sector bodies with technical means and legal assistance.” Along the same line, Verhulst (2021) considers data stewards as experts “identifying opportunities for productive cross-sector collaboration and responding pro-actively to external requests for functional access to data, insights or expertise.” Beyond such framing, data stewards (and stewardship processes) can be established with the task of advising any relevant data actor part of any digital initiative on aspects related, but not limited to, data quality, data provision, data access, data (re)use, and data management. More concretely, the key points are, on the one hand, how to properly design data stewardship processes to effectively link diverse arrays of actors across scales and belonging to different sectors, especially when they mobilize different interests and principles at individual and collective levels; and, on the other hand, the kind of competences data stewards should be equipped with to deliver their function as systemic facilitators, which also implies to design interdisciplinary inter-sectorial curricula for consolidating the emergence of these figures.

Concerning governance, the issue at stake is the design of a resilient sociotechnical process, which can be streamlined across scales as well as transposed in different contexts. Failure to do so will always result in the limited lifespan of digital initiatives. More concretely, this translates into the need to systematize the data commoning through a framework that defines (a) agreed forms of in/exclusion in each initiative (e.g., scale and actors involved) on a rolling basis; (b) how to synthesize and/or disentangle between individual and collective dimensions. For instance, the Data Act (European Parliament and Council, 2022a) mentions the requirement for member states to set up “settlement bodies” to ensure “alternative ways of resolving domestic and cross-border disputes in connection with making data available.” Yet, it is still unclear how to properly design such settlement bodies so that they harmonize legal frameworks across scales and in different contexts. Overall, points (a) and (b) shall be designed by keeping flexibility in mind, insofar as it is the very concept of collectual equilibrium which requires so. As a consequence, to be at stake is a three-fold issue: (1) a value-laden exploration of what public (data) interest means and how it is informed by and beyond individual data interests; (2) the exploration of how public (data) interest gets re-articulated across scales and contexts; (3) the design of regulatory mechanisms to disentangle and adjudicate rights and duties based on point (1) and (2).

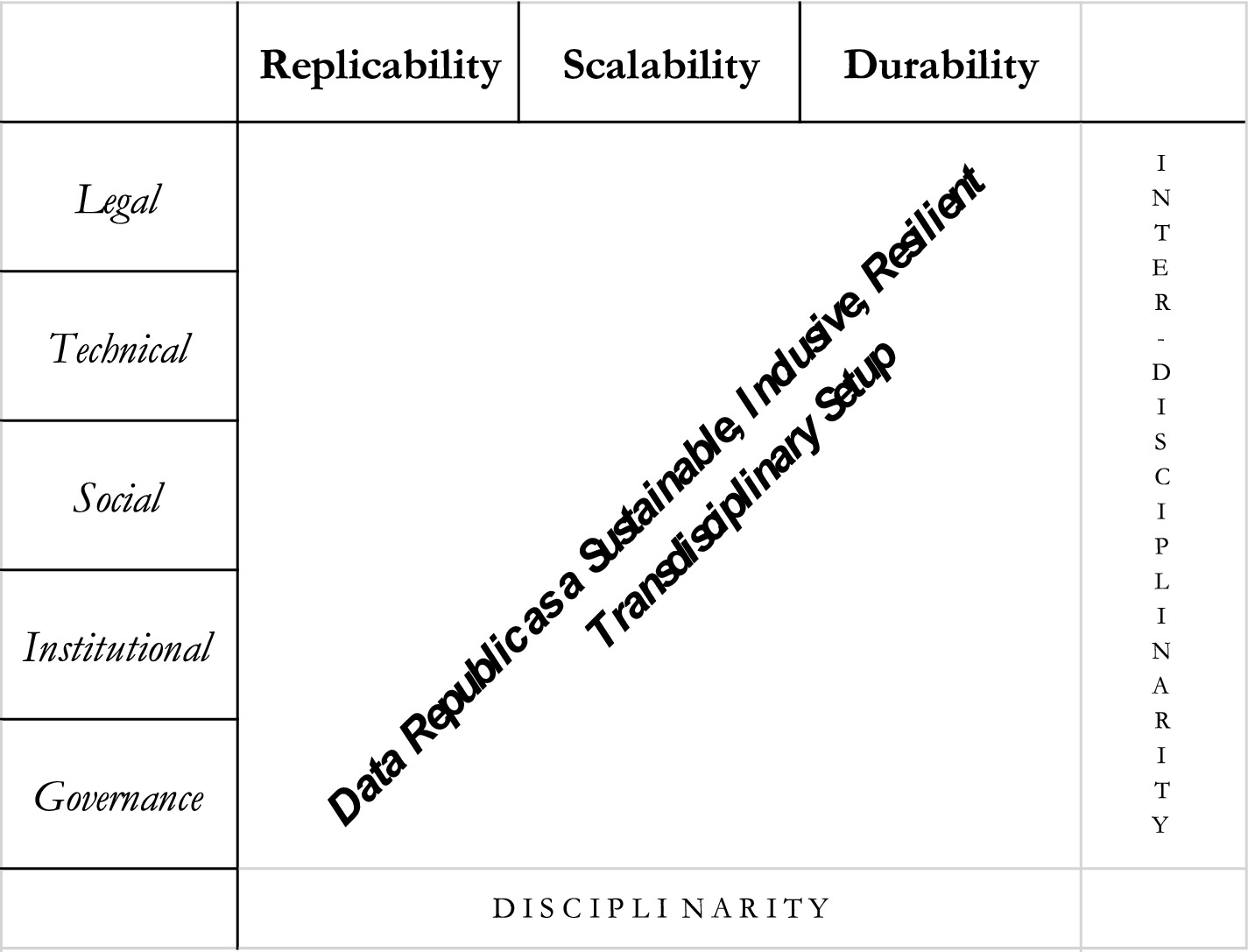

5 Toward the Data Republic

By combining structural limits and substantial barriers, we obtain a Figure 3 that can be explored both disciplinarily—i.e., following the rows—and interdisciplinary—i.e., following the columns. By crossing the two axes, it becomes possible to transdisciplinarily explore the enactment of socio-economically sustainable, inclusive, and resilient digital initiatives. Just as an example, governance row might concretize in the exploration of issues, such as (1) the design of a public single contact point to which citizens can relate for data-related enquiries (as far as replicability is concerned); (2) stewardship processes to link top-down and bottom-up actors and data initiatives (as far as scalability is concerned); (3) the sustainable conditions enabling a public-private synergy for the pooling and sharing of data beyond emergency situations only (as far as durability is concerned). Each of these issues, then, shall be explored conjointly from different disciplinary angles—i.e., institutional, social, technical, and legal—along the replicable, scalable and durable columns, so that, in the end, the sustainability, inclusiveness and resilience of each issue addressed (each box) emerges out of the analysis, rather than being imposed upfront.

Building on recent work (Calzati and van Loenen, 2023a), one possible theoretical setup for Figure 3 is a Data Republic: “to be a republican” Susskind (2022) writes, “is to regard the central problem of politics as the concentration of unaccountable power.” In this vein, we acknowledge current contributions framed within democratic political theory (e.g., “constitutionalism,” cf. de Gregorio, 2020) which aim to explore the specific features of a republican setup in connection with the digital landscape. However, our goal here is to conceptualize the Data Republic in broader terms as a systemic governance model for transdisciplinarily tackling the digital transformation, that is, a model that counteracts the individualistic focus of the EU’s digital strategy in the direction of a collectual equilibrium. On this, we align with the idea of “radical republicanism” (Hoeksema, 2023) which considers the application of a republican approach to the digital realm as a structural issue, not simply one of agency of this or that actor: as Hoeksema (2023) writes, radical republicanism is especially concerned with “the economic rationales and the socio-technical infrastructures that underlie and support digital platforms.” Along this line, the Data Republic model we propose below is concerned with establishing the framework within which the digital transformation can play out fairly, i.e., in a balanced way (cf. Rochel, 2021), thus thinking about European citizens (individuals) and citizenry (collective) as a polity (cf. Calzati, 2023). Before singling out the specifics of the Data Republic, some preliminary clarifications are needed.

First, why a republic? The res publica (from the Greek politeia, referring to the conditions of existence of the polis and its citizens) identifies the management of the public good by citizens and for the citizenry. Moreover, since the time of the Roman republic, such a form of government implied the division of powers among different bodies. These two are the main tenets on which our idea of Data Republic—translated into the scenario of today’s digital transformation—rests.2

If we speak of theoretical setup, it is because, at present, the Data Republic remains a model at a high level of abstraction that requires further testing and validation; yet, as a theoretical setup, the Data Republic does have a rationale, and this is rooted in the evidence coming from literature on data commons. As seen, this literature highlighted the extent to which data commons initiatives are a viable path toward a sustainable, inclusive, and resilient management of the digital transformation, insofar as they do strive for a collectual balance. However, literature also highlighted barriers (here thematically clustered) to the replicable, scalable, and durable success of such initiatives (even though, as noted, these structural limits are themselves under scrutiny through the enactment of a Data Republic).

From here, the Data Republic is meant to tackle these barriers, notably as a systemic model where sociotechnical factors and non/institutional actors are pulled together toward orchestrated collaboration, enabled by the definition of roles, rules, and mechanisms that can guarantee power distribution, mutual accountability, and collegial control. This is why, then, the Data Republic is systemic, insofar as it does not prioritize a priori any actor, factor, or principle over others, but seeks ongoing balance among all these, so that equilibrium—and the possible disentanglement between individual and collective dimensions—is de facto the meta-principle grounding the model.

In this sense, the setup of the Data Republic outlined above is transdisciplinary in that it aims to facilitate synergic convergence across factors, actors, and processes beyond silos. It is the codependency between factors, actors, and processes—i.e., the need to approach them simultaneously, discerning on a case-by-case scenario how to balance them—that can help counteract the current European individualistic focus and economic rationale, regarding the digital transformation as a complex systemic process.

In our previous work (Calzati and van Loenen, 2023a), we discussed how the institutionalization of open data initiatives and spatial data infrastructures can complement the structural limits of data commons initiatives. Such a complementarity, in turn, constitutes the basis for the Data Republic, on which we expand at length. While we redirect to our previous work for such a discussion, here we limit ourselves to recall and synthetize the data Republic’s key tenets:

1. A two-tier articulation, combining institutional Public-led Data Trusts (PDT), currently identified as a robust model for participatory data governance (van der Sloot and Keymolen, 2022), with the design of non-institutional “data communes” led voluntarily by communities of citizens. This is meant to consolidate top-down (institutional) and bottom-up (non-institutional) stances and their pooling around a techno-legal framework that can guarantee representation and cooperation on a principle basis and in view of shared socio-economic goals.

2. The establishment of key figures and processes of public data stewards/ship, with the goal to mediate between the PDT and data communes and facilitate the formation of digital initiatives, also through the provision of literacies and techno-legal support. Through ongoing data steward/ship, then, both the inclusion of diverse arrays of non/institutional actors and the organizational resilience of digital initiatives can be enhanced, by flexibly linking local-(supra) national scales, as well as finetuning to contextual issues.

3. A board of arbitration, which is responsible for counseling and/or adjudicating among contentious issues occurring at various scales, based on cases of conflicting rights and principles, and/or among various actors. The board, formed by representatives of the data communes, the PDT, and data stewards, is meant to constitute a tertiary body that complies with and operationalizes EU legislation on a case-by-case rolling basis, by disentangling individual rights and interests and collective principles.

There are no people-centric digital initiatives without the sustained inclusion of diverse actors. This entails the recognition of and cooperation between institutional (cf. PDT) and non-institutional actors in their capacity as non-institutional actors (cf. data communes).

There are no people-centric digital initiatives without balanced socio-economic sustainability. This entails the complementary co-creation (and its accountability) of economic and social value, which, in turn, requires weighing individual (e.g., companies and consumers) and collective (societal) rights and principles (i.e., board of arbitration).

There are no people-centric digital initiatives without the establishment and consolidation of long-term digital literacies and techno-legal capabilities. This entails unlocking organizational change, as well as know-how transfer across sectors and actors, through enabling systemic resilience (cf. data steward/ship).

As such, the Data Republic foregrounds a systemic-procedural management of digital initiatives which is contextual and contingent in the fostering of a virtuous complex sociotechnical process. In this regard, the Data Republic also aligns with ongoing discussions on digital public infrastructures (Eaves et al., 2024) and Eurostack (Bria et al., 2025) and it might work as a compass for the design of European data spaces beyond their current techno-legal framing aligned with the DSM (Calzati and van Loenen, 2023c).

Concretizing further the enactment and testing of the Data Republic setup, we envision, based on the literature and the cases surveyed in the previous sections, that such enactment and testing might occur, at first, at the city level, as a middle ground between (supra)national and local levels. As the Barcelona and Hamburg initiatives attest, indeed, the city is a locus of thriving technological innovation, and it is also the target of increasing tech-based digitalization, which entails an ongoing “translation” from the physical to the digital and vice versa. In this respect, urban data are part and parcel of a sociotechnical infrastructure around which citizens can be directly involved and from which they can also directly benefit, making the feasibility of the Data Republic more likely.

6 Conclusion

This article made the case for the need to rebalance the individualistic focus underpinning, de facto, the EU’s digital strategy with a collective dimension that, while being declared and acknowledged, is not enacted through the envisioned DSM. To do so, we first anchored the fuzzy notion of “people-centric,” adopted in various documents by the EU, to the concept of “collectual equilibrium.” Then we operationalized such a concept in terms of socio-economic sustainability, inclusiveness, and resilience (SIR), and we showed that the EU’s digital strategy fails to be collectual and SIR, i.e., people-centric.

From here, we explored the data commons as a collectual SIR regime for managing digital initiatives, although still affected by limits and barriers. Based on the lessons learned from recent data commons initiatives, we outlined a transdisciplinary theoretical setup that concretizes into the idea of a Data Republic as a systemic governance model for pursuing a collectual digital transformation. As outlined here, the Data Republic has the goal of identifying a path forward for tackling data commons’ limits and barriers; hence, the setup remains at a high level of abstraction which needs further testing and validation.

It is also important to note that from this picture is excluded the exploration of the green sustainability of digital initiatives, i.e., the footprint these have on the environment. While the collective dimension referred to here includes, in principle, green sustainability, the impact of data and digital infrastructures on the environment remains the blind spot of much research on their governance (Hasselbalch, 2022), even when research aims precisely to favor the EU’s green transition. Hence, the green sustainability of digital initiatives requires to be tackled by further research.

Author contributions

SC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The term “digital initiative” is preferred to “data initiative” because the former encompasses a broad sociotechnical understanding of digital transformation including, for instance, beyond technical and legal aspects, social and non-institutional factors and actors.

2. ^One might also ask why a data republic (instead of, for instance, a digital republic). We opted for “data” because we wanted to keep the focus on the resource that the republic, as a governance model, is meant to manage, instead of using an adjective that would qualify the republic rather than what it refers to.

References

Aizenberg, E., and Van Den Hoven, J. (2020). Designing for human rights in AI. Big Data Soc. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/2053951720949566

Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2019). Digital transformation: City data commons. Barcelona City Council. Available online at: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/digital/ca (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Ansell, C., and Torfing, J. (2021). Co-creation: the new kid on the block in public governance. Policy Polit. 49, 211–230. doi: 10.1332/030557321X16115951196045

Au, L., and Kuuskemaa, M.. (2019). Social control or a fix for a non-law-abiding society? Mercator Institute for China Studies. Available online at: https://www.merics.org/en/blog/social-control-or-fix-non-law-abiding-society (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Balestrini, M., Rogers, Y., Hassan, C., Creus, J., and King Mand Marshall, P. (2017). “Activity in common: a framework to orchestrate large-scale citizen engagement around urban issues” in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (New York: Association for Computing Machinery), 2282–2294.

Bell, J., Aidinlis, S., Smith, H., Mourby, M., Gowans, H., Wallace, S. E., et al. (2019). Balancing data subjects’ rights and public interest research: examining the interplay between UK law, EU human rights law and the GDPR. Eur. Data Prot. Law Rev. 5:43. doi: 10.21552/edpl/2019/1/8

Bettencourt, L. M. (2015). “Cities as complex systems” in Modelling complex systems for public policies. eds. B. A. Furtado, P. A. M. E. Sakowski, and M. H. E. Tóvolli (Brasilia: Ipea), 217–236.

Bloom, G., Raymond, A., Tavernier, W., Siddarth, D., Motz, G., and de Rosnay, M. D.. (2021). A practical framework for applying Ostrom’s principles to data commons governance. Mozilla foundation. Available online at: https://www.mozillafoundation.org/en/blog/a-practical-framework-for-applying-ostroms-principles-to-data-commons-governance/ (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Bond, A., Morrison-Saunders, A., and Pope, J. (2012). Sustainability assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 30, 53–62. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2012.661974

Bria, F., Timmers, P, and Gernone, F. (2025) EuroStack – a European alternative for digital sovereignty. Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/publications/2025/feb/eurostack-european-alternative-digital-sovereignty (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Brown, T. (2019). “Human rights in the smart city: regulating emerging technologies in city places” in Regulating new Technologies in Uncertain Times. ed. L. Reins (Berlin: Asser Press), 47–65.

Calzada, I., and Almirall, A. (2020). Data ecosystems for protecting European citizens’ digital rights. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 14, 133–147. doi: 10.1108/TG-03-2020-0047

Calzati, S. (2022). Federated data as a commons: a third way to subject-centric and collective-centric approaches to data epistemology and politics. J. Inf. Commun. Ethics Soc. 21, 16–29. doi: 10.1108/JICES-09-2021-0097

Calzati, S. (2023). “Shaping a data commoning polity: prospects and challenges of a European digital sovereignty” in Electronic participation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. eds. N. Edelmann, L. Danneels, A. S. Novak, P. Panagiotopoulos, and I. Susha, vol. 14153 (Berlin: Springer), 162–177. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-41617-0_10

Calzati, S., and van Loenen, B. (2023a). A fourth way to the digital transformation: the data republic as a fair data ecosystem. Data Policy 5:e21. doi: 10.1017/dap.2023.18

Calzati, S., and van Loenen, B. (2023b). Towards a citizen- and citizenry-centric digitalization of the urban environment: urban digital twinning as commoning. Digit. Soc. 2:38. doi: 10.1007/s44206-023-00064-0

Calzati, S., and van Loenen, B. (2023c). Beyond federated data: a data commoning proposition for the EU’S citizen-centric digital strategy. AI & Soc. 40, 945–957. doi: 10.1007/s00146-023-01743-9

Davis, M. (2020). Get smart: human rights and urban intelligence. Fordham Urb. Law J. 47, 971–991. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol47/iss4/6 (last accessed 1 September 2025)

de Gregorio, G. (2020). The rise of digital constitutionalism in the European Union. Int. J. Const. Law 19, 41–70. doi: 10.1093/icon/moab001

de Lange, M., and de Waal, M. (2019). The hackable city: Digital media and collaborative city-making in the network society. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Dulong de Rosnay, M., and Stalder, F. (2020). Digital commons. Internet Policy Rev 9, 1–22. doi: 10.14763/2020.4.1530

Eaves, D., Mazzucato, M., and Vasconcellos, B. (2024) Digital public infrastructure and public value: what is “public” about DPI? Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/publications/2024/mar/digital-public-infrastructure-and-public-value-what-public-about-dpi (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Commission (2019) Policy and investment recommendations for trustworthy AI. Available online at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/policy-and-investment-recommendations-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Commission (2021) Digital Europe programme (DIGITAL). Available online at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/first-calls-proposals-under-digital-europe-programme-are-launched-digital-tech-and-european-digital (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Commission (2022a) Commission staff working document on common European data spaces. Available online at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/staff-working-document-data-spaces (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Commission (2022b) European declaration on digital rights and principles for the digital decade. Available online at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/declaration-european-digital-rights-and-principles (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Commission (2022c) Digital Europe programme (DIGITAL). Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/digital/wp-call/2022/call-fiche_digital-2022-cloud-ai-03_en.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Parliament and Council (2012a) Charter of fundamental rights of the European Union. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012P/TXT (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Parliament and Council. (2016). Regulation on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data (general data protection regulation). https://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Parliament and Council. (2019). Directive on open data and the re-use of public sector information (open data directive). Available online at: https://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/1024/oj (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Parliament and Council (2020a) A European strategy for data. Available online at: https://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0066 (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Parliament and Council (2020b) Regulation on European data governance (data governance act). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022R0868 (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Parliament and Council (2022a) Proposal for a regulation on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (data act). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A68%3AFIN (Accessed September 1, 2025).

European Parliament and Council (2022b) Regulation on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (digital markets act). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R1925

European Parliament and Council (2024) Interoperable Europe act. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/903/oj (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Finck, M., and Pallas, F. (2020). They who must not be identified: distinguishing personal from non-personal data under the GDPR. Int. Data Privacy Law 10, 11–36. doi: 10.1093/idpl/ipz026

Fu, X., Woo, W. T., and Hou, J. (2016). Technological innovation policy in China: the lessons, and the necessary changes ahead. Econ. Change Restruct. 49, 139–157. doi: 10.1007/s10644-016-9186-x

Hasselbalch, G. (2022) Data pollution & power. Available online at: https://uni-bonn.sciebo.de/s/bYOsFyNiZ9sPlY4/download (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Hoeksema, B. (2023). Digital domination and the promise of radical republicanism. Philos. Technol. 36:17. doi: 10.1007/s13347-023-00618-7

Kalpokas, I. (2022). “Posthuman urbanism: Datafication, algorithmic governance and Covid-19” in The Routledge handbook of architecture, urban space and politics. eds. N. Bobic and F. Haghighi (London: Routledge), 496–508.

Kapoor, S., Mojsilovic, A., Strattner, J. N., and Varshney, K. R.. (2015). From open data ecosystems to systems of innovation: a journey to realize the promise of open data. In Bloomberg data for good exchange conference (pp. 1–8). Bloomberg.

Kummitha, R. K. R. (2020). Why distance matters: the relatedness between technology development and its appropriation in smart cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 157:120087. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120087

Lane, J., Stodden, V., Bender, S., and Nissenbaum, H. (Eds.) (2014). Privacy, big data, and the public good: Frameworks for engagement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ludwig, T., Pipek, V., and Tolmie, P. (2018). Designing for collaborative infrastructuring: supporting resonance activities. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2:Article 113. doi: 10.1145/3274382

Mergel, I., Kleibrink, A., and Srvik, J. (2018). Open data outcomes: U.S. cities between product and process innovation. Gov. Inf. Q. 35, 622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.09.004

Monge, F., Barns, S., Kattel, R., and Bria, F. (2022) A new data deal: the case of Barcelona. Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/sites/bartlett_public_purpose/files/new_data_deal_barcelona_fernando_barns_kattel_and_bria_18_feb.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Morozov, E., and Bria, F.. (2018). Rethinking the smart city: democratizing urban technology. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. Available online at: https://rosalux.nyc/rethinking-the-smart-city-democratizing-urban-technology (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Mulder, I., and Kun, P. (2019). Hacking, making, and prototyping for social change. In M. Langede and M. Waalde M (Eds.), The hackable city (pp. 225–238). Berlin: Springer

Nicolescu, B. (2005). Towards transdisciplinary education. J. Transd. Res. Southern Africa 1, 11–16. doi: 10.4102/td.v1i1.300

Ponti, M., Portela, M., Pierri, P., Daly, A., Milan, S., Kaukonen Lindholm, R., et al. (2024). Unlocking green deal data: innovative approaches for data governance and sharing in Europe. Available online at: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC139026 (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Pope, J., Annandale, D., and Morrison-Saunders, A. (2004). Conceptualising sustainability assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 24, 595–616. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2004.03.001

Purtova, N., and van Maanen, G. (2023). Data as an economic good, data as a commons, and data governance. Law Innov. Technol. 16, 1–42. doi: 10.1080/17579961.2023.2265270

Purvis, B., Mao, Y., and Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 14, 681–695. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

Rochel, J. (2021). Ethics in the GDPR: a blueprint for applied legal theory. Int. Data Privacy Law 11, 209–223. doi: 10.1093/idpl/ipab007

Sanfilippo, M., and Frischmann, B. (2023). “A proposal for principled decision-making: beyond design principles” in Governing smart cities as knowledge commons. eds. B. Frischmann, M. Madison, and M. Sanfilippo (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 295–308.

Schneider, I. (2020). Democratic governance of digital platforms and artificial intelligence? Exploring governance models of China, the US, the EU and Mexico. JeDEM 12, 1–24. doi: 10.29379/jedem.v12i1.604

Smuha, N. A. (2021). Beyond the individual: governing AI’S societal harm. Internet Policy Rev. 10, 1–32. doi: 10.14763/2021.3.1574

Sun, P. (2007). Is the state-led industrial restructuring effective in transitioning China? Evidence from the steel sector. Camb. J. Econ. 31, 601–624. doi: 10.1093/cje/bem002

Susskind, J. (2022). The digital republic: On freedom and democracy in the 21st century. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Taylor, L., Floridi, L., and van der Sloot, B. (2016). “Introduction: a new perspective on privacy” in Group privacy. Philosophical studies series, vol. 126 (Berlin: Springer), 1–12.

The New Hanse Project (2023) Governing urban data for the public interest. Available online at: https://thenewhanse.eu/en/blueprint (Accessed September 1, 2023).

Theilen, J. T., Baur-Ahrens, A., Bieker, F., Ammicht Quinn, R., Hansen, M., and González Fuster, G. (2021). Feminist data protection: an introduction. Internet Policy Rev. 10, 1–26. doi: 10.14763/2021.4.1609

Troullaki, K., Rozakis, S., and Kostakis, V. (2021). Bridging barriers in sustainability research: a review from sustainability science to life cycle sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 184:107007. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107007

Valli Buttow, C., and Weerts, S. (2022). Public sector information in the European Union policy: the misbalance between economy and individuals. Big Data Soc. 9, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/20539517221124587

van der Sloot, B., and Keymolen, E. (2022). Can we trust trust-based data governance models? Data & Policy 4:e45. doi: 10.1017/dap.2022.36

Verhulst, S. (2021). Reimagining data responsibility: 10 new approaches toward a culture of trust in re-using data to address critical public needs. Data Policy 3:e6. doi: 10.1017/dap.2021.4

Viljoen, S. (2021). A relational theory of data governance. Yale Law J. 131:573. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45400961

Voss, G., and Pernot-Leplay, E. (2023). China data flows and power in the era of Chinese big tech. Northwest. J. Int. Law Bus. 44:4393008. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4393008

Wolff, A., Gooch, D., Cavero, J., Rashid, U., and Kortuem, G. (2019). Removing barriers for citizen participation to urban innovation. In M. Langede M & M. Waalde (Eds.), The hackable city (pp. 153–168). Berlin: Springer

Woulters, P. T. J. (2018). The control by and rights of the data subject under the GDPR. J. Internet Law 22. https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/194516/194516pub.pdf (Accessed 1 of September).

Yeung, K., Howes, A., and Pogrebna, G. (2020). “AI governance by human rights–centred design, deliberation, and oversight: an end to ethics washing” in The Oxford handbook of ethics of AI. eds. M. Dubber, F. Pasquale, and S. Das (Oxford University Press), 77–104.

Zeng, D. Z. (2017). Measuring the effectiveness of the Chinese innovation system: a global value chain approach. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 1, 57–71. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1440.101005

Keywords: data commons, republic, sustainability, inclusiveness, resilience, data governance, EU, transdisciplinarity

Citation: Calzati S and van Loenen B (2025) The Data Republic: fostering a sustainable, inclusive and resilient digital transformation for the European Union. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1670152. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1670152

Edited by:

Masaru Yarime, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Federico Tomasello, University of Messina, ItalyAnne Marte Gardenier, Eindhoven University of Technology, Netherlands

Copyright © 2025 Calzati and van Loenen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bastiaan van Loenen, Yi52YW5sb2VuZW5AdHVkZWxmdC5ubA==

Stefano Calzati

Stefano Calzati Bastiaan van Loenen*

Bastiaan van Loenen*