- 1Department of International Relations, Universitas Hasanuddin, Makassar, Indonesia

- 2School of Sociology, Politics, and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

Past studies have emphasized the significance of reclamations, oil and gas drilling operations, and the deployment of coast guards, as symbols of effective occupancy in grey zone areas of the South China Sea. Unfortunately, the rising number of Chinese research ships infiltrating Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) seems to be disregarded in its significance, as scholars interpret the actions as taken-for-granted events. This qualitative, multiple empirical case study aims to elucidate the maritime events, situated within the analytical framework of maritime diplomacy’s persuasive and coercive maritime conduct. Utilizing data attained from AIS and reported by Marine Traffic, Sea Vision, SeaLight, and Windward between 2019 and 2025, this study concludes the following: (1) the deliberate deployment of Chinese research ships as means to project the state’s maritime power despite the lack of understanding as whether the operations fall within the spectrum of scientific, military, or commercial research; (2) the function of compelling Vietnam to abandon or cancel the oil and gas drilling operations undertaken within its EEZ; and (3) populating the seas as means to display effective occupation and weaken the adversary’s claim by establishing a landscape of latent threats at sea.

1 Introduction

For Vietnam, the overlapping maritime zones with China in the South China Sea remain a significant concern for its foreign policy. Vietnam was hit hard in 1974 and 1988, following clashes with China over the Paracels and Spratly Islands (Blazevic, 2012; Chubb, 2022). Unfortunately, despite not being as confrontational as the past, instances of China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea would continue to undermine Vietnam’s EEZ. Among the most significant crises was the placement of a drilling rig in the Paracel Islands back in 2014, which was only 119 nautical miles away from Vietnam’s baselines (Brummit, 2014; Storey, 2014; Torode and Zhu, 2014). Displaying decisiveness in challenging China has been challenging for Vietnam, considering its foreign policy doctrine prioritizes avoiding military alliances, not hosting foreign bases, and not aligning with a country to counter another (Putra, 2024b).

For China, actions undertaken in the South China Sea have now become the new normal in its tactics to claim sovereignty in grey zone areas. The claims are based on historic rights (Fravel, 2011; Yahuda, 2013; Stubbs and Stephens, 2017), visually marked with 10 dashed lines that span across the South China Sea and overlap the EEZ of several Southeast Asian states: Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, Vietnam, and the Philippines. As mentioned in Xi Jinping’s ‘China Dream’ speech back in 2013, Xi envisioned China to rise as a maritime power and the need to recover lost territories. Therefore, China’s grey zone tactics in the South China Sea by populating the disputed waters with Chinese Coast Guards (CCG), fisheries surveillance vessels, fisheries militia, and research vessels, have been regular occurrences observed in those waters (Thayer, 2011; Sinaga, 2016; Zhang and Bateman, 2017; Jennings, 2021; Guilfoyle and Chan, 2022). Unlike the tensions with Vietnam in 1974 and 1978, China perceives no need for the use of lethal military force, as its current strategies of pressure have been able to compel other claimant states in Southeast Asia (Poling, 2025).

Nevertheless, one area that remains relatively less explored within academia is the utilization of China’s research vessels as a means of signaling sovereignty in the South China Sea. As reported by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI), the terms’ research vessel’ and ‘survey vessel’ have been interchangeable. Still, they would typically undertake the following functions: marine scientific research, oil and gas commercial surveys, and naval surveillance (AMTI, 2020a). Within the past decade, China has intensified the presence of its civilian research vessels conducting research across the Indo-Pacific region. Typically, oceanographic research programs serve both scientific and commercial objectives, including climate change research, the distribution of natural resources, and the study of the dynamic undersea environment. However, in the case of China, there is a tendency for its research to be connected to the country’s strategic ambitions due to its massive scale and blurred line between civilian and military research (Funaiole et al., 2024a; Funaiole et al., 2024b).

The problem with these operations is the location of the research vessels. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) outlines that the operation of research vessels within a state’s EEZ or continental shelf requires the approval of a government at least 6 months prior to an operation (AMTI, 2020a; Lan, 2025). However, as China’s research vessels primarily operate in their presumed sovereign waters of the 10 Dash Line, such forms of consent have never been attained. Consequently, similar to the deployment of the CCGs in the South China Sea, China’s research vessels for the most part have freely roamed the disputed waters under the presumption that the waters being operated in are owned by China. As reported by various think tanks and news agencies, the presence of these research ships has raised significant concerns among the claimant states of Southeast Asia, as they perceive the vessel to have dual functions, serving both scientific and military purposes (AMTI, 2020c, 2022; Funaiole et al., 2024a).

A more concerning development is that the South China Sea is not the only waterway where the survey ships operate. In the 2024 China People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Defense White Paper, there is a mention of the Indian Ocean as a region of importance for the PLA, which would then lead to an extension of China’s strategic perimeter (Funaiole et al., 2024a). As seen in the following figure, China’s survey ship, the Xiang Yang Hong 01, was observed operating in the Eastern Indian Ocean, the Western Pacific Ocean, and near Australia’s Christmas Island between 2019 and 2020. In the 2020 case near the Christmas Islands, Australian officials speculated that the survey vessels were looking closely at the routes of Australia’s submarines travelling to the South China Sea (AMTI, 2020a). The lack of permission secured from the coast states also indicates the difficulty of truly knowing what the survey vessels were undertaking between commercial surveys, marine scientific research, or legal military surveillance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Surveys conducted by China’s Xiang Yang Hong 01 (2019–2020). Source: AMTI (2020a).

This qualitative, multiple empirical case study, problematizes the use of survey ships in the disputed waters of the South China Sea. Regarding Chinese research vessels operating within Vietnam’s maritime zones, it acknowledges that it is challenging to discern the true nature of the survey vessel’s operations, and that unreported survey operations can fall within either the scientific research or military surveillance spectrum. Therefore, this study bridges the maritime diplomacy literature, aiming to provide a better understanding of the developments occurring in the disputed waters. In past studies of maritime diplomacy, primarily from the works of Le Mière (2014), the bridging of the literature enables a better understanding of why specific actions occur in the seas. Situated within the typologies of coercive, persuasive, or co-operative maritime diplomacy, this study offers a unique interpretation of the use of survey vessels in the South China Sea, highlighting their similar sovereignty signaling functions to China’s past maritime strategies through the CCGs and fisheries surveillance vessels. Looking into cases of Chinese survey vessels operating in Vietnam’s maritime zones between 2019 and 2025, this study utilizes data of Chinese oceanographic missions to track the presence of its research and survey vessels from Marine Traffic, Sea Vision, Sea Light, and Windward, which reveals the unique trajectory of the ships in each given case.

2 China’s maritime strategies in the South China Sea: a literature review

How have existing studies interpreted the use of research and survey vessels in the disputed waters of the South China Sea? For one, there is an acknowledgment that the methods deployed have varied, ranging from coast guards and fishing militia to fisheries surveillance vessels that have the dual functions of safeguarding China’s sovereign waters and displaying sovereignty. Unfortunately, the use of survey vessels has, in large part, been taken for granted, as there have been few scholarly inquiries into their actions. Nevertheless, to truly grasp China’s maritime diplomatic intentions in utilizing those vessels, this literature review will discuss several interpretations of China’s maritime strategies related to the inquiry made in this study.

A large body of literature has explored the question of maritime tactics in the grey zone areas of the South China Sea, with some studies terming the issue as ‘hybrid warfare’. There is acknowledgement that the South China Sea constitutes one of the most strategic shipping lanes in the world (Chen et al., 2017; Reeves, 2019; Nguyễn et al., 2024). With the South China Sea covering a large portion of the Pacific Ocean, the investigations made by past studies have agreed that the grey zone areas have seen different maritime strategies as means to display effective occupancy over the disputed waters (McLaughlin, 2022; Ormsbee, 2022; Arif et al., 2024; Sarjito, 2024). The primary focus of this discourse looks at the differences of opinions in how China symbolizes its sovereignty in the South China Sea, which eventually leads to cases of reclamations, utilizing maritime constabulary forces, and safeguarding illegal fishing operations in other maritime zones (Kelly, 2014; Stubbs and Stephens, 2017; Parameswaran, 2019; Tarriela, 2022; Putra, 2023a; Zhang, 2023). Meanwhile, the term hybrid warfare also represent a similar dynamic, with the use of different hard power assets to assert rule and control over disputed waters (Joshi and Tara Singh, 2021; Mumford and Carlucci, 2023; Patalano, 2018).

As a means to display sovereignty, among the first of China’s maritime strategies in the South China Sea was to transform the rocks and reefs into actual islands. Studies have investigated the question of why such reclamations occurred, primarily examining the variables of rationality, capability, and opportunity (Stubbs and Stephens, 2017; Zhang et al., 2022). Scholars perceive that in order to have a stronger footing over the South China Sea, the actual construction of islands would need to take place through a series of dredging and reclamation efforts, which would eventually lead to China being able to display their sovereignty over the disputed waters and islands (Stubbs and Stephens, 2017; Koga, 2022). Other studies have also examined the benefits of utilizing reclaimed islands in accelerating the exploration of the South China Sea’s oil and gas resources (Meierding, 2017; Mi et al., 2022; Mukherjee, 2022; Luo, 2023).

Nevertheless, the main guards to demonstrate sovereignty in disputed waters. On the former, Martinson, 2021 study mentioned how the Chinese Government played a decisive role in enabling fishing vessels to operate within the EEZ of other nations in the South China Sea by providing protection and financial incentives (Martinson, 2021). Meanwhile, others have looked at the role of subnational governments, such as in Hainan, as having significant roles in pushing fisheries actors to undertake outward expansion operations and securitize the fishing fleets, leading to an increased presence of the typically used term of ‘fishing militia’ in the South China Sea (Zhang and Bateman, 2017; Zhang, 2023). One of the reasons why such a problem persists is due to the heavy presence of CCGs operating across the South China Sea and in close proximity to China’s fishing boats.

Coast guards typically have a positive image associated with them, as the institution tends to assume roles that protect a state’s seas from vast non-traditional security threats. However, in the case of China, the negative image of being a tool for China’s grey zone areas (displaying sovereignty) is a notion often attached to the CCGs (Guilfoyle and Chan, 2022). Others have examined the role of the CCGs in projecting China’s maritime power image through regular patrols aimed at demonstrating the state’s true maritime capabilities (Chao, 2024). Examining the dual functions of the CCGs, a considerable number of studies have also explored the connections between the extensive domestic law reforms and the increasing presence of the CCGs in disputed waters, highlighting their links to military operations (Kim, 2022; Liu and Hu, 2024).

Unfortunately, the use of survey ships has not attracted as much attention among scholars. Several notable mentions of the use of research ships were made by Raymond and Welch in 2022, stating that China has deployed different maritime strategies that utilize methods such as oil drilling rig placements and survey ships to assert its maritime claims decisively (Raymond and Welch, 2022). Martinson and Dutton (2018) interpreted that China’s oceanographic research fleets tend to operate beyond Chinese jurisdictional waters. Interestingly, they make a claim similar to one made for this study, in which the dramatic developments and actions of these scientific research vessels are “largely go unnoticed” (Martinson and Dutton, 2018, p. 1). Meanwhile, other inquiries have focused on the legality of these marine scientific research efforts, which are interpreted as complicating the situation between China and other coastal states (Hong, 2021).

From the literature review above, it is clear that the utilization of research vessels has been taken for granted in the case of the South China Sea. The lack of scholarly interpretation regarding why those fleets are operated in risky waters, as well as the true intentions behind their use, has led to media speculation and think tanks’ opinions dominating the interpretation of survey fleets. As reported by AMTI and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the interpretation that tends to be offered is that the research ships used are to display sovereignty, and as a means for effective occupancy (AMTI, 2020a, 2022; Funaiole et al., 2024a; Funaiole et al., 2024b).

This study argues that, through the lens of the maritime diplomacy framework, a more nuanced understanding of the use of research vessels in disputed waters can be obtained. In the past, the literature contributed immensely to the knowledge of maritime constabulary forces (fisheries surveillance vessels and coast guards) utilized as a sovereignty-displaying tool for state actors (Le Mière, 2011b, 2011a; Chang, 2018; Putra, 2023a, 2023b). Therefore, civilian vessels, despite not being categorized as military hard power assets, have the same diplomatic functions as navies, in which their presence in particular waters is a display of de facto sovereignty to a state’s adversaries. By bridging the analytical framework of maritime diplomacy, this study will be the first to interpret China’s use of research vessels within the context of managing international relations through the maritime domain. It argues that the survey ships’ presence conveys much more diplomatic significance than a simple conduct of marine scientific research.

3 The analytical framework of maritime diplomacy

Prior to the introduction of maritime diplomacy, scholars refer to the use of coercion via the seas as ‘gunboat diplomacy’ (Cable, 1994; Le Mière, 2011b; Tarriela, 2018). The term, however, has started to fade with the decreasing occasions in which warships are used to bombard ports or stand by within a state’s coasts. Therefore, as an attempt to conceptualize the use of different forms of maritime strategies outside of wartime, and with the involvement of actors beyond navies, the term maritime diplomacy was introduced. In doing so, there is acknowledgment within the existing literature that maritime diplomacy captures, “[…] a variety of non-military agencies that can have similar diplomatic effects to those traditionally reserved for navies” (Le Mière, 2014, p. 2). The framework of maritime diplomacy, therefore, effectively captures the diplomatic signaling of the use of non-military assets of a state, which is described as an “[…] intent of one’s policies and capabilities of one’s security forces” (Le Mière, 2014, p. 3).

Therefore, as the analytical framework for this study, several definitions require clarification. First, the definition of maritime diplomacy follows Le Mière’s 2014 conception as a “[…] management of international relations through the maritime domain” (Le Mière, 2014, p. 7). Regarding the actors that can undertake maritime diplomatic functions, this also aligns with the maritime diplomatic literature, which suggests that other civilian actors can act as diplomatic signaling agents for a country (therefore, a role not confined to a state’s navy). Hence, the use of research vessels falls under the category of ‘maritime constabulary forces,’ which are civilian vessels used during peacetime, intending to signal to allies or adversaries of a state’s intent through actions at sea (Le Mière, 2014; Putra, 2023a, 2023b). Although the South China Sea is fraught with tensions, it falls far short of the traditional definition of active warfare. Therefore, to interpret the actions taken by the other maritime vessels within the spatial space, it agrees with the maritime diplomacy’s assertion that, “[…] maritime forces, when acting in peacetime, are involved in diplomatic activities almost all of the time” (Le Mière, 2014, p. 7), and that different maritime agencies can undertake diplomatic functions.

For this study, recent actions using research vessels in disputed waters will be framed within the context of maritime diplomacy’s three diplomatic typologies: co-operative, persuasive, and coercive. Before elaborating further on which typology suits the empirical case of this research most, a brief overview is provided as to what differentiates these three diplomatic typologies. The one thing, however, that unites the typologies is that they all are attempts to signal one’s intent and capabilities in the maritime domain (Le Mière, 2014).

Co-operative maritime diplomacy encompasses various forms of diplomacy that navies or other civilian maritime constabulary forces can undertake. They include humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, goodwill visit, joint maritime security operations, and joint training (Le Mière, 2014). As demonstrated in the arguments of past studies, co-operative maritime diplomacy is employed by state actors for peaceful activities, with the actors involved united by common political goals (Le Mière, 2014; Nugraha and Sudirman, 2016; Rijal, 2019; Noferius et al., 2020; Putra, 2024a). Consequently, the expected diplomatic goals would be within the realms of building soft power, advancing confidence measures, and fostering coalitions.

The second and third typologies are concerned with what the literature mentions as persuasive and coercive maritime diplomacy. In the case of persuasive maritime diplomacy, the goal is best defined as to “[…] increase recognition of one’s maritime or national power, and build prestige for the nation on the international stage” (Le Mière, 2014, p. 12). Therefore, it is not expected that states have the intentions to deter, nor to compel an adversary. In contrast, coercive maritime diplomacy aims to compel adversaries and shape their policy preferences. The term “maritime diplomacy” refers to the use of coercive power, which mostly follows the logic of gunboat diplomacy. The differentiating point, however, in coercive maritime diplomacy, is that the actions considered are not confined to the policies undertaken by navies, but also include the maritime constabulary forces that are non-military. As Le Mière defined the action, it is “[…] an activity that can be undertaken by states and non-state actors […] it is the threat or use of limited maritime force to display or utilize military capabilities and/or intent” (Le Mière, 2014, pp. 20–21).

Examining the three different maritime diplomacy typologies, this study aims to interpret the recent deployment of China’s research and survey vessels in the South China Sea as examples of persuasive and coercive maritime diplomacy. Based on the definitions provided by the maritime diplomacy literature, it is difficult to situate the actions taken at sea within the spectrum of co-operative maritime diplomacy. For one, the actions are not based on the goal of collaboration, nor coalition building. As seen in several of the case studies presented in the next section, these research vessels tend to be present in the hotspots of disputed waters, and are oftentimes accompanied by CCGs (AMTI, 2020a, 2020b, 2022, 2024b). The form of action undertaken does not fall into the traditional forms of co-operative maritime diplomacy, suggesting the relevance of other diplomatic typologies.

Therefore, two typologies hold relevance in explaining the case of research and survey vessels used in the South China Sea. First is persuasive maritime diplomacy. Although the element of displaying one’s maritime capabilities does not suit the context of China’s use of survey fleets, China’s intentions to demonstrate its presence to adversaries through the research fleets are well-documented in the discussed empirical cases. Furthermore, this study also situates the actions as a form of coercive maritime diplomacy. The intent is evident in the active efforts to compel adversaries at sea by taking dangerous maneuvers that could easily escalate tensions. By doing so, this study demonstrates that coerciveness can be employed outside of wartime as a form of diplomatic signaling of a country’s intent. In the case of the South China Sea, the aim is to compel adversaries to abandon their oil and gas explorations in the South China Sea as a form of claiming sovereignty.

4 China’s marine research vessels in troubled waters: cases between 2019 and 2025

A series of confrontations between Vietnam and China’s maritime law enforcement forces occurred between 2019 and 2025. Perhaps one of the most concerning developments involved China’s research vessel, the Haiyang Dizhi 8, which was stationed within Vietnam’s EEZ for 4 months in 2019 (ending in October). The crisis started in June 2019, with the deployment of CCGs near the operations of Hakuryu 5 (a drilling rig) from Vietnam’s oil and gas Block 06–01 (AMTI, 2020a). Besides the CCGs operating in those waters, the Haiyang Dizhi 8’s trajectory provoked Vietnamese officials, as the travelled paths were drawing closer to Vietnam’s oil and gas operations.

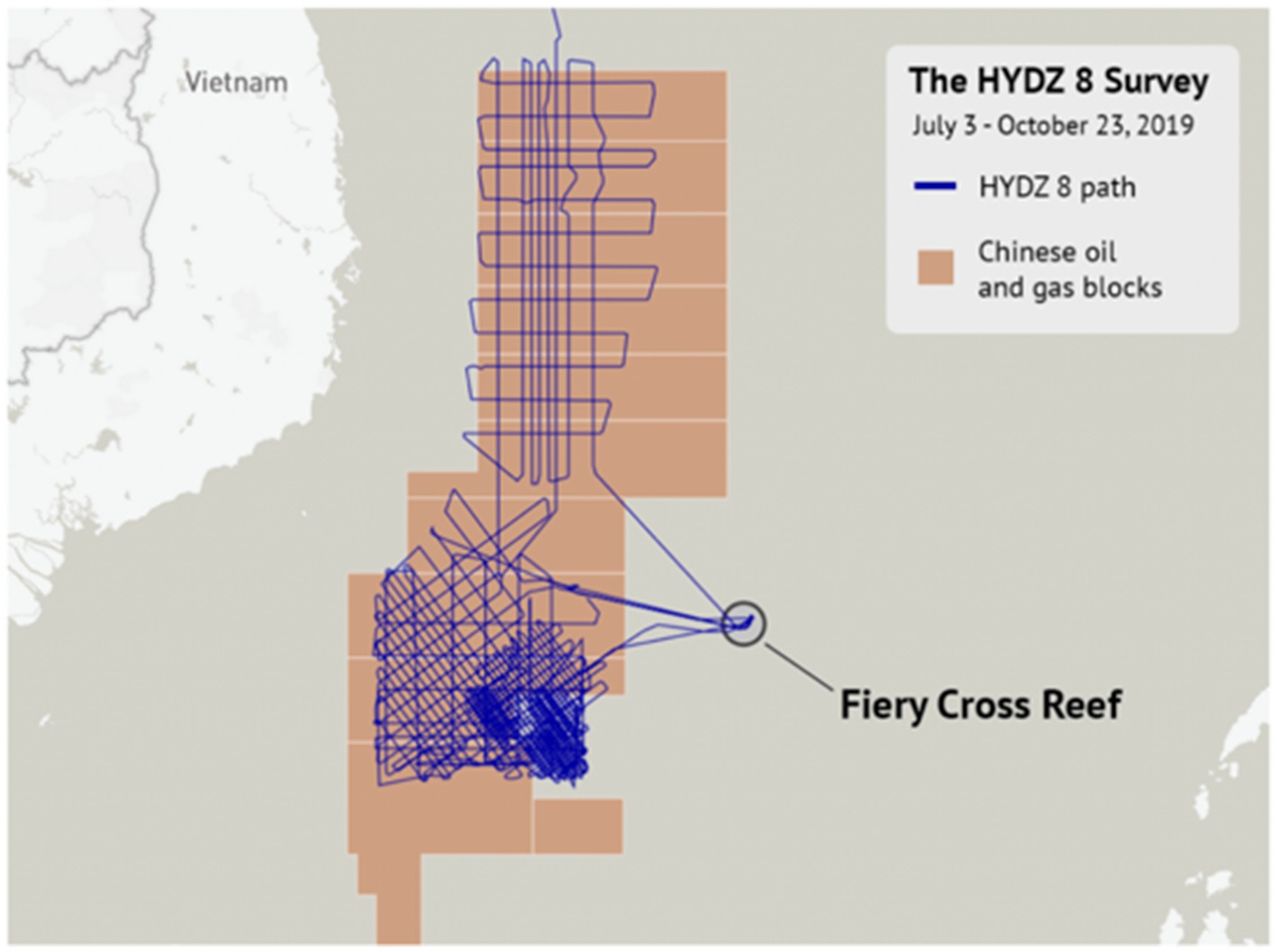

As shown in Figure 2 below, between July and October 2019, the path of the Haiyang Dizhi 8 was close to China’s oil and gas blocks that were offered for foreign bidding in 2012 (AMTI, 2019). Interestingly, the oil and gas blocks fall under Vietnam’s continental shelf, which ultimately led to a series of confrontations between the constabulary forces of Vietnam and China. Furthermore, what made the situation intense was that the Haiyang Dizhi 8 was oftentimes accompanied by the presence of a CCG ship operating close to the research vessel.

Figure 2. The trajectory of the Haiyang Dizhi 8 between July 3 and October 23, 2019. Source: AMTI (2019).

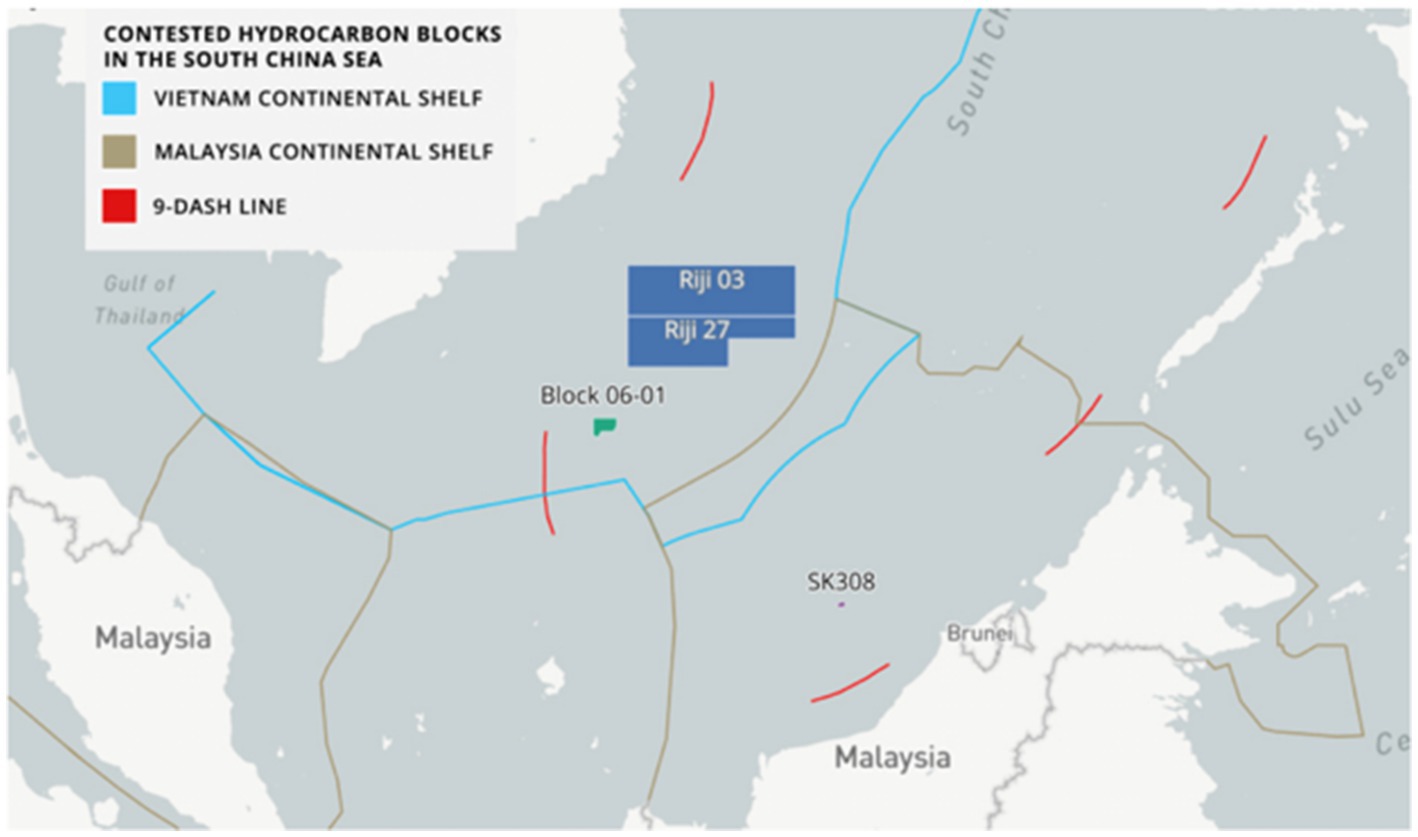

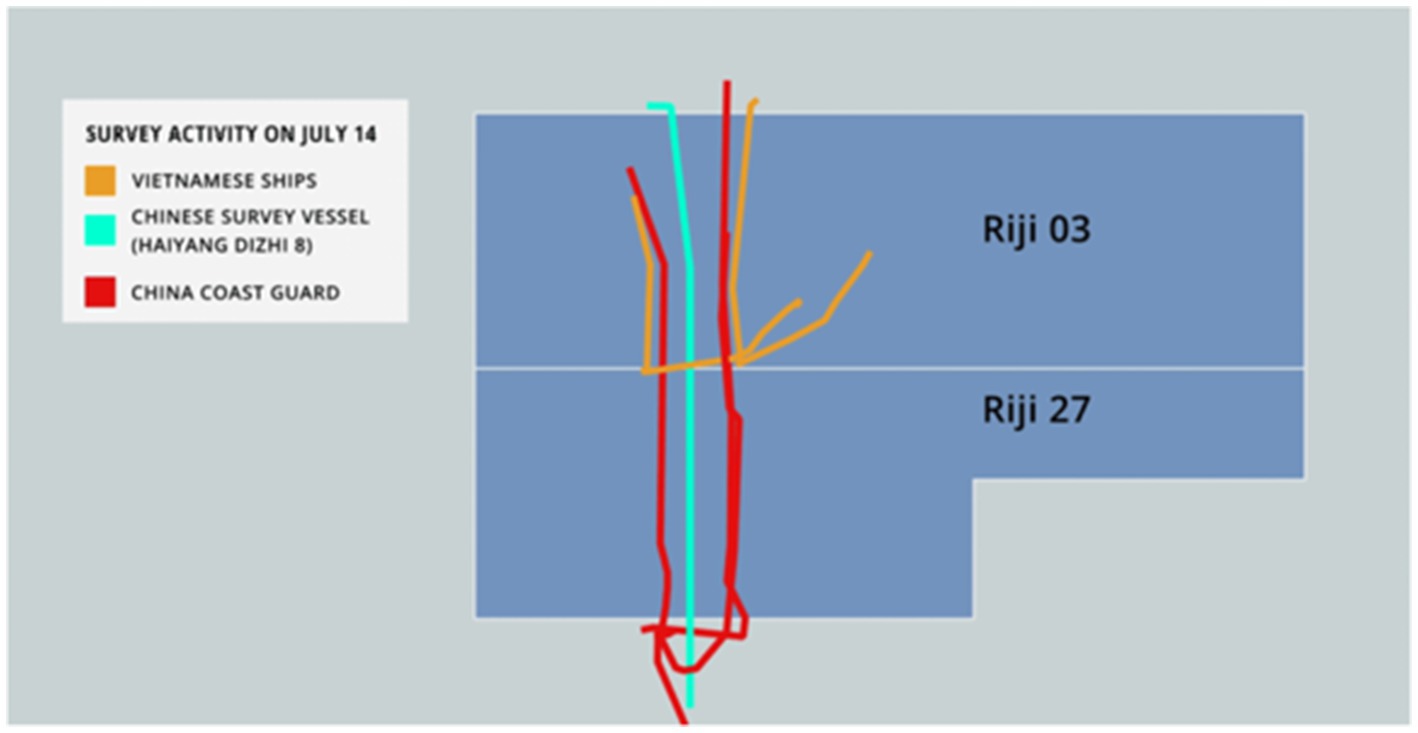

Consequently, the situation became dangerous over the potential escalation of tensions among the maritime constabulary forces. As seen in Figure 3, the location of China’s oil and gas blocks falls within China’s claimed Ten-Dash Line, but also falls under Vietnam’s UNCLOS-recognized continental shelf. Therefore, despite the Haiyang Dizhi 8 primarily operating in Chinese-occupied areas (Figure 4), its proximity to Vietnamese-occupied maritime features indicates a concerning development in the South China Sea. Vietnam’s Block 06-01was then safeguarded by Vietnamese Fisheries Surveillance Vessels, as a means to safeguard Rosneft’s drilling in Block 06–01 (AMTI, 2019). Therefore, as seen in Figure 4 below, the Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8, CCGs, and Vietnamese ships were involved in close encounters as Chinese vessels aimed to disrupt Vietnam’s oil and gas drilling in Block 06–01. Worthy to point out that a total of four CCGs escorted China’s survey ship, showing that the conduct of surveys and research is directly connected to the increasing presence of the CCGs within a claimant state’s waters.

Figure 3. Map of the contested hydrocarbon blocks in the South China Sea (dark blue: China’s claimed maritime features). Source: AMTI (2019).

Figure 4. Haiyang Dizhi survey activity on 14 July 2019, along with the trajectory of Vietnam and Chinese ships. Source: AMTI (2019).

For context, this was not the first occasion in which China’s vessels compelled Vietnam to halt or stop oil and gas drilling operations. Back in 2017 and 2018, China’s maritime constabulary forces successfully placed pressure on Vietnamese policymakers and led to the cancellation of drilling in Vietnam’s oil and gas block (operated by Repsol) (Panda, 2018; Sutton, 2021). Data from the Automatic Identification System (AIS) in 2019, therefore, shows a similar pattern, in which China’s research vessels are intentionally placed in high-risk areas, with the hope of disrupting certain operations. The chances of collision, even escalation, were the main fear for Vietnamese policymakers. Not to mention the economic repercussions due to the provocations made in the state’s oil and gas block.

In the following years (2020 and 2021), reports have shown a return to normality in the deployment of research vessels in the contested waters of the South China Sea. As shown in the AIS data provided by Marine Traffic, China’s research vessels have been identified operating in overlapping EEZs of China and the claimant states of the South China Sea (AMTI, 2022). Similar to the Haiyang Dizhi 8 crisis in 2019, in all of these instances, China’s research vessels were accompanied by a heavy presence of maritime law enforcement and militia vessels, which further complicated the situation at hand. As reported by AMTI, China’s survey fleets are among the largest in the Indo-Pacific (AMTI, 2022). Therefore, their capacity to be present in different parts of the expansive South China Sea speaks volumes about their intention to populate the seas, if not, to compel its smaller Southeast Asian adversaries to cease their oil and gas drilling operations, which have become a common occurrence as of late (AMTI, 2023b).

Similar to the crisis in 2019, the tensions involving China’s survey vessel Xiang Yang Hong 10 in 2023 also attracted considerable criticisms from Vietnamese officials. The Xian Yang Hong, accompanied by Chinese fishing militia boats, CCGs and unknown ships with Chinese flags, approached the Blocks 04–03, 05-1B, and 05-1C, which are Vietnam’s oil and gas blocs operated by Vietsovpetro, Zarubezhneft, PetroVietnam, and Idematsu Kosan (Guarascio, 2023; Guarascio and Chen, 2023). Another concern was that the operation of the Xiang Yang Hong 10 extended only 47 nautical miles from Vietnam’s baseline (Lan, 2023; Nguyen, 2023; TST, 2023), causing considerable concern among Vietnamese policymakers.

Meanwhile, the responses from the China and Vietnam Foreign Ministries are interesting to cover. For China, the presence of its survey and research ships should not cause tensions as China claims rights over the relevant waters. Mao Ning, the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s Spokesperson, stated, “It is legitimate and lawful for relevant Chinese vessels to carry out normal activities in waters under China’s jurisdiction. There is no such thing as entering in other countries’ exclusive economic zones” (Lan, 2023). In contrast, the Deputy Spokesperson of Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs provided a different response, “Vietnam requests that Chinese relevant authorities observe the consensus between the two countries’ high-level leaders, to cease immediately any acts of violation, withdraw the Xiang Yang Hong 10 and other vessels from Vietnamese waters” (Lan, 2023). Clearly, China’s approach to utilizing its research and survey vessels differs from that of Vietnam, potentially disrupting bilateral relations due to tensions at sea.

Unfortunately, the perspective of normality adopted by Chinese officials is expected to continue in 2025. The use of its research ships is continuously used in order to display sovereignty over waters that Vietnam claims as its EEZ. As seen in Figure 5 below, data from SeaLight showed the pursuit made by Vietnam’s Kiem Ngu 471 (A: starting point; B: ending point) in June and July of 2025, in response to the deployment of China’s survey vessel Bei Diao 996 (1: starting point; 2: ending point) (McCartney, 2025). The survey ship appeared to conduct a hydrographic survey, undertaking a ‘lawnmower pattern’ as it usually does in past cases, a typical method in seafloor mapping (Kajee, 2025). Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded that any research and survey operations within the state’s EEZ are violations of the UNCLOS (McCartney, 2025).

Figure 5. Confrontation involving Bei Diao 996 (red) and Kiem Ngu 471 (yellow) between June–July 2025. Source: McCartney (2025).

Examining the multiple empirical case studies conducted between 2019 and 2025, several essential patterns of action require highlighting. First, China’s research vessels tend to be accompanied by a larger number of Chinese ships, ranging from fishing militia to CCGs. Second, the presence of the survey ships is always situated in the overlapping maritime claims between Vietnam and China, with China entering Vietnam waters with full understanding of the illegal narrative oftentimes mentioned by Vietnamese policymakers. And third, the deployment of adversaries in several oil and gas blocs with research vessels, presumably to disrupt the operations of natural resource exploitation in the South China Sea. Having acknowledged these key patterns of actions, the following section will explore the maritime diplomacy interpretation of events involving China’s research and survey vessels.

5 Research and survey ships: a maritime diplomacy interpretation

Situated within the typologies of maritime diplomacy, this section will explore the relevance of persuasive and coercive maritime diplomacy to the empirical cases examined in this study. First, in the case of persuasive maritime diplomacy, the focus is the presence of the vessels itself, as a means to display a state’s national power (Le Mière, 2014). Nevertheless, there is no connection to the affecting of others’ policies, as the focus is on signaling the capabilities (maritime) of a state.

In the case of China’s use of survey and research ships. There is, however, a specific dilemma encountered. The true nature of these survey ships cannot be known, as their actions may be within the realms of scientific purposes or military operations. This presents a problem, as the purpose of the survey (commercial, scientific, or military) determines the legality of the operations undertaken at sea (AMTI, 2022). Therefore, between 2019 and 2025, China could serve both civilian and military purposes. Unlike other countries, China does not distinguish between ships operating for naval survey, scientific research, or commercial purposes (Funaiole et al., 2024a). The PLAN has research ships and other survey ships from China’s Ministry of Natural Resources and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, for example, which have strong formal ties with the PLAN in terms of data sharing (AMTI, 2020a). This situation is mentioned in a report as the “hallmarks of Beijing’s military-civil fusion” (Funaiole et al., 2024a).

Therefore, within the context of persuasive maritime diplomacy, the focus is on showcasing China’s maritime power towards Vietnam. Having been involved in a series of bloody clashes in the 20th century and encountering the oil drilling rig standoff of the Hai Yang Shi You 981 in 2014, Vietnam is one of China’s most significant challengers to the South China Sea. Similar to China, Vietnam has also enhanced its maritime capacities to match the challenges posed by China’s maritime presence. This is marked by an increase of Vietnam’s Fisheries Surveillance vessels and Vietnam Coast Guards, which act as the maritime constabulary forces of Vietnam to counter grey zone maritime tactics in the South China Sea (Blazevic, 2012; Chubb, 2022; De Gurung, 2018; Sangtam, 2021). Therefore, Vietnam also acknowledges that there needs to be a sidelining of the presence of navies, with the dominant display of other maritime agencies as a means to display sovereignty in disputed waters.

With China, its utilization of research vessels is an extension of already existing efforts to display its maritime might. By deploying research vessels accompanied by other law enforcement forces, China has benefited from demonstrating its capabilities without necessarily seeking to influence Vietnam’s policies. This interpretation, therefore, is centered on populating the seas of disputed waters, to ensure that China’s maritime presence continues to be perceived as being present (and increasing) across the overlapping maritime zones between China and Vietnam.

However, the interpretation that China does not aim to affect Vietnam’s policies comes quite contrary to the actual empirical cases examined in this study. Reviewing the cases of Haiyang Dizhi 8 and Bei Diao 996, it is clear that China has discreet messages it aims to convey. By sending messages, there is also the intention to shape a state’s policies to align with Beijing’s preferences in the context of the South China Sea. Therefore, the relevance of coercive maritime diplomacy’s arguments can be used to make sense of China’s intentions with its use of research and survey vessels.

As the maritime diplomacy literature emphasizes, there is a remarkable resemblance between coercive maritime diplomacy and gunboat diplomacy. Perhaps the only differentiation in this case is the hard power assets used. Gunboat diplomacy only considers navies as capable of emitting coercive signals to their adversaries; meanwhile, coercive maritime diplomacy considers different maritime constabulary forces as being capable of assuming such a role (Le Mière, 2011b; Le Mière, 2014; Tarriela, 2018). Besides the actors undertaking maritime diplomatic actions, another essential issue to highlight is the intention behind them. Unlike persuasive maritime diplomacy, which aims to display a state’s maritime power, coercive maritime diplomacy seeks to compel an adversary through the use of limited maritime force (Le Mière, 2014). Therefore, a thick element of coercive maritime diplomacy is the intention to affect the policies of other actors.

Bridged to the empirical cases examined in this study, many of the crisis then makes sense. First, based on the actors operating in the South China Sea, the dominant force would comprise China’s maritime constabulary forces rather than its navy. By utilizing research ships, China benefits from showing that it is willing to be present in overlapping maritime zones in a way that international law acknowledges as legitimate actions at sea (albeit, with the secured permission of the coastal state). The blurring of the purposes of China’s survey ships, which can fall within the spectrums of commercial, scientific, or military, is acceptable to China, as the state tends to obscure its intentions when undertaking actions that contravene existing international laws. For example, the use of the CCGs across the South China Sea can arguably be categorized as illegal, considering that the actions involve entering a coastal state’s EEZ without prior notifications provided. However, considering that survey ships and CCGs are more ‘civilian’ compared to navies, their use immediately conveys a signal of non-coerciveness and decreases the potential for escalating tensions.

Nevertheless, a coercive maritime diplomacy interpretation would show that the cases are united by the intention to compel oil and gas drilling operations in Vietnam’s EEZ. The instances of Haiyang Dizhi 8 in 2019, Xiang Yang Hong 10 in 2023, and Bei Diao 996 in 2025 are representative of the tens of similar cases in the South China Sea, in which China’s constabulary forces were deployed to disrupt natural resource exploitation in the disputed waters. With the Haiyang Dizhi 8, for example, the intentional positioning of the survey vessel close to Vietnam’s oil and gas blocks aimed to imitate the success that the CCGs had with the eventual cancellation of Repsol’s drilling operations in 2017 and 2018. In all three cases, the presence of the CCGs was also heavily observed, indicating that the intentions of the research ships’ presence are dual function. The first is obviously within the realms of scientific research. However, the second function is to display that they are active in those waters, and any actions related to oil and gas exploration will not be acceptable to Chinese authorities.

The aim to compel oil and gas operations is a significant one. Over the past decade, a trend has emerged among Southeast Asian states to explore the natural oil and gas resources in the South China Sea (AMTI, 2023b). This is especially true in the case of Vietnam, which has accelerated its oil and gas drilling operations within its EEZ by contracting foreign companies to conduct those operations (AEDS, 2025; Ha and Tien, 2024; OBG, 2017; Searancke, 2022). In the case of the South China Sea, emerging trends often begin with China’s actions, which are then followed by those of Southeast Asian states. First, the conduct of reclamation began with Chinese officials building islands from rocks and small maritime features, a policy subsequently followed by other claimant states to the South China Sea (Stubbs and Stephens, 2017; Zhang, 2023). Second, the increasing presence of the CCGs was met by Southeast Asian states with the purchase of multi-functional vessels and the establishment of maritime law enforcement laws, enabling them to establish their own coast guards (Morris, 2017; Parameswaran, 2019; Tarriela, 2022). Somewhere in between those developments is China’s exploration of oil and gas blocks, which eventually is developed similarly by other claimant states. Therefore, as Southeast Asian states start to explore ways to exploit the natural resources in areas that overlap in the South China Sea, China has been in a rush to compel those operations, under the thought that the operations remain illegal.

However, another argument can be made for the display of sovereignty. In grey zone areas, such as the South China Sea, the typical argument for maritime zones based on UNCLOS is difficult to uphold. China has demonstrated that these laws do not apply within the context of the South China Sea, and that anything is up for grabs. Therefore, increasing the presence of its maritime forces, including the additional research and survey ships in the South China Sea, reflects a normality in utilizing China’s (perceived) seas for both military and civilian purposes. Vietnam is demonstrating that it will not be bullied at sea and has responded decisively in all emerging cases. However, this does not close the fact that by openly operating just several hundred nautical miles from Vietnam’s coastline. Within Vietnam’s EEZ, China is aiming to solidify its claims in the South China Sea.

The argument of solidifying maritime zone claims also aligns with maritime diplomacy’s arguments on ‘paragunboat diplomacy.’ Paragunboat, as maritime constabulary forces, has discreet diplomatic signals that can be emitted. For one, the maritime diplomacy literature mentions this as reinforcing the state’s claim of sovereignty (Le Mière, 2014). Therefore, by deploying research vessels, CCGs, fishing militia, and other Chinese-flagged vessels within Vietnam’s EEZ, China benefits from displaying that “[…] de facto sovereignty exists over the area” (Le Mière, 2014, p. 40). Through the use of the CCGs, China is portraying itself as taking the trouble to police its waters against vast traditional and non-traditional security threats. Meanwhile, the deployment of its research ships indicates that it is conducting normal scientific operations in areas that it presumes fall within China’s jurisdiction. The lack of consent secured from Vietnam suggests that, from China’s perspective, those waters fall under its sovereignty, and permission to undertake research operations is not required.

However, what speaks volumes in the empirical cases examined is the presence of CCGs accompanying the research vessels. By CCGs safeguarding the research vessels, China is showing that it is policing a territory, with the aim of effective occupancy to support China’s de jure claim. In the past, the presence of CCGs harassing smaller Southeast Asian fishing boats was seen as a significant crisis, generating massive media coverage. However, as time passed, the presence of CCGs never faded away; instead, there seems to be an acknowledgement that this is how China conducts its operations in grey zone areas, and that nothing is new. By doing so, it has normalized the discourse of coast guards defending presumed maritime zones, which, although still contested by other claimant states, suggests that there is little that can be done. What started with smaller numbers eventually evolved into near-daily presence of CCGs across different parts of the disputed waters (AMTI, 2020c, 2023a, 2024a, 2025). The increasing use of research ships in the South China Sea appears to be heading in the same direction, as China seeks to normalize the practice by consistently deploying its maritime fleets in contested waters.

Two other benefits are observed. The maritime diplomacy literature also argues that constabulary forces are used to weaken the state’s claims, as well as to provide a latent threat to other states. In the case of research ships in Vietnam’s EEZ, it is clear that by increasing China’s vessels in those waters, China is aiming to undermine Vietnam’s claims over its maritime zones. But the latent threat element is also considerably significant. As the empirical cases show, whenever a Chinese survey ship is present in Vietnam’s EEZ, there tends to be small skirmishes and limited confrontations between CCGs (as accompanying the research ships) and Vietnamese vessels. The situation could easily escalate, making the presence of research ships complicate the South China Sea crisis to levels that are difficult to manage.

6 Conclusion

Tensions in the South China Sea have escalated with the introduction of other maritime constabulary forces aimed at demonstrating China’s de facto sovereignty over its claimed Ten-Dash Line. In recent years, the increasing number of research and survey ships operating within the EEZ of Southeast Asian states is a concerning development. The use of survey ships, taking on the form of either commercial, military, or scientific purposes, tends to disregard their significance. Past studies have highlighted various forms of development as holding significant importance to the dynamics of the South China Sea, including reclamations, natural resource exploitation, fishing militias, and coast guards. However, this study perceives that there is more to the presence of research ships than simply undertaking the function of ‘researching.’ With the vast number of deployed survey ships in the South China Sea, this study problematizes such developments and aims to provide a maritime diplomatic interpretation of these events.

Primarily based on AIS data from numerous sources, this study perceives that the use of survey ships is China’s deliberately deployed and strategically utilized method to assert and display China’s maritime prestige. Several of the cases explored in this study include the Haiyang Dizhi 8 in 2019, Xiang Yang Hong 10 in 2023, and Bei Diao 996 in 2025. Several important dynamics unite these empirical cases. First, there is no proper way to determine whether the research vessels conduct scientific, military, or commercial survey operations, which affects the legality of their operations. Second, in all cases, Chinese research ships would be accompanied by a heavy presence of China’s maritime militia, primarily by the CCGs. Third, the operations tend to be undertaken in times when Vietnam is undertaking oil and gas drilling operations within its EEZ.

The highlights of the empirical cases are then interpreted within the analytical framework of maritime diplomacy. In the first level, it is argued that China’s maritime presence through research ships is an attempt to display that its maritime constabulary forces are present in overlapping EEZ borders. In this interpretation, it is not argued that China’s actions have any attempt to affect others’ policies. However, by showing the flag, China aims to normalize its presence alongside the diverse vessels present.

Second is the interpretation that the use of research and survey vessels constitutes China’s coercive maritime diplomacy. In contrast to the interpretation under the persuasive maritime diplomacy framework, coercive actions at sea aim to elicit a change in behavior or policy from the adversary, as specific actions are deliberately orchestrated to compel a change. In the empirical cases examined in this article, it is clear that the point of compelling adversaries can be seen with the research vessels operating in close proximity to Vietnam’s oil and gas drilling operations. In 2017 and 2018, the CCGs successfully compelled Vietnam to cancel its operations (managed by Repsol) due to the heavy presence of its coast guards. China, in more contemporary contexts, aims to replicate the past success, albeit using different forms of fleets.

Ultimately, several intentions can be highlighted in this regard. First, with the presence of research ships accompanied by other maritime constabulary forces, China benefits from the effective display of its occupancy in disputed waters through policing the areas. The effective occupation, therefore, leads to the direct weakening of Vietnam’s claims of its own maritime borders, as the fear of latent threats continues to surface with the increasing number of Chinese vessels populating the disputed waters. Therefore, the bridging of maritime diplomacy within this context shows that research and survey ships deployed in the South China Sea are merely an extension of China’s existing maritime strategies to occupy grey zone areas.

Author contributions

BP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AEDS. (2025). Vietnam digs in on South China Sea oil and gas projects amid Chinese pressure. ASEAN Centre for Energy. Available online at: https://aseanenergy.org/news-clipping/vietnam-digs-in-on-south-china-sea-oil-and-gas-projects-amid-chinese-pressure/ (Accessed June 12, 2025).

AMTI. (2019). UPDATE: China risks flare-up over Malaysian, Vietnamese Gas Resources. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/china-risks-flare-up-over-malaysian-vietnamese-gas-resources/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2020a). A survey of marine research vessels in the Indo-Pacific. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/a-survey-of-marine-research-vessels-in-the-indo-pacific/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2020b). Update: Chinese survey ship escalates three-way standoff. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/chinese-survey-ship-escalates-three-way-standoff/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2020c). Still on the beat: China coast guard patrols in 2020. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/still-on-the-beat-china-coast-guard-patrols-in-2020/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2022). What lies beneath: Chinese surveys in the South China Sea. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/what-lies-beneath-chinese-surveys-in-the-south-china-sea/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2023a). Flooding the zone: China coast guard patrols in 2022. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/flooding-the-zone-china-coast-guard-patrols-in-2022/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2023b). (Almost) everyone is drilling inside the nine-dash line. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/almost-everyone-is-drilling-inside-the-nine-dash-line/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2024a). Control by patrol: the China coast guard in 2023. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/control-by-patrol-the-china-coast-guard-in-2023/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2024b). Seismic strife: China and Indonesia clash over Natuna survey. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/seismic-strife-china-and-indonesia-clash-over-natuna-survey/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

AMTI. (2025). China coast guard patrols in 2024: an exercise in futility? Available online at: https://amti.csis.org/china-coast-guard-patrols-in-2024-an-exercise-in-futility/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Arif, M., Afriansyah, A., Chairil, T., and Lestari, G. A. (2024). Grey zone conflict in the South China Sea. Contemp. Southeast Asia 46, 407–434. doi: 10.1355/cs46-3c

Blazevic, J. J. (2012). Navigating the security dilemma: China, Vietnam, and the South China Sea. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 31, 79–108. doi: 10.1177/186810341203100404

Brummit, C. (2014). Vietnam tries to stop China oil rig deployment : USA Today News. Available online at: https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2014/05/07/vietnam-china-oil-rig/8797007/

Cable, J. (1994). Gunboat diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan Publishers. Available online at: https://link.springer.com/book/9780312353469 (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Chang, Y. C. (2018). The ‘21st century maritime silk road initiative’ and naval diplomacy in China. Ocean Coast. Manage. 153, 148–156. doi: 10.1016/J.OCECOAMAN.2017.12.015

Chao, J. (2024). The impact of the China coast guard on Indo-Pacific and Southeast Asia security from the perspective of a maritime power. IKAT 7, 13–29. doi: 10.22146/IKAT.V7I1.100387

Chen, J. M., Tan, P. H., Liu, J. S., and Shiau, Y. J. (2017). Shipping routes in the South China Sea and northern Indian Ocean and associated monsoonal influences. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 28, 303–313. doi: 10.3319/TAO.2016.09.08.01

Chubb, A. (2022) Dynamics of assertiveness in the South China Sea: China, the Philippines, and Vietnam, 1970-2015 Available online at: https://www.nbr.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/publications/sr99_dynamicsofassertiveness_may2022.pdf (Accessed May 25, 2025).

De Gurung, A. S. B. (2018). China, Vietnam, and the South China Sea an analysis of the “three Nos” and the hedging strategy. Indian J. Asian Aff. 31:8. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26608820

Fravel, M. T. (2011). China’s strategy in the South China Sea. Contemp. Southeast Asia 33, 292–319. doi: 10.1355/cs33-3b

Funaiole, M. P., Hart, B., and Powers-Riggs, A. (2024a). Surveying the seas: China’s dual-use research operations in the Indian Ocean. CSIS. Available online at: https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/china-indian-ocean-research-vessels/ (Accessed May 25, 2025).

Funaiole, M. P., Powers-Riggs, A., and Hart, B. (2024b) Skirting the shores: China’s new high-tech research ship probes the waters around Taiwan. CSIS. Available online at: https://features.csis.org/snapshots/china-research-vessel-taiwan/ (Accessed May 25, 2025).

Guarascio, F. (2023). Vietnam sends ship to track Chinese vessel patrolling Russian gas field in EEZ. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/vietnam-sends-ship-track-chinese-vessel-patrolling-russian-gas-field-eez-data-2023-03-27/ (Accessed June 05, 2025).

Guarascio, F., and Chen, L. (2023). Chinese ships leave Vietnam waters after Hanoi protest. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinese-ships-leave-vietnam-waters-after-us-china-talks-2023-06-06/ (Accessed June 05, 2025).

Guilfoyle, D., and Chan, E. S. Y. (2022). Lawships or warships? Coast guards as agents of (in)stability in the Pacific and south and East China Sea. Mar. Policy 140:105048. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOL.2022.105048

Ha, D. T., and Tien, T. N. (2024). Vietnam - India oil and gas cooperation: from “strategic partnership” to “comprehensive strategic partnership.”. Int. J. Relig. 5, 212–225. doi: 10.61707/MK4K8805

Hong, N. (2021). China’s approach to marine scientific research: legislation, policy and practice. Korean J. Int. Comp. Law 9, 294–310. doi: 10.1163/22134484-12340159

Jennings, R. (2021) Analysts: Vietnam expanding fishing militia in South China Sea. VOA. Available online at: https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_analysts-vietnam-expanding-fishing-militia-south-china-sea/6205729.html (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Joshi, S., and Tara Singh, I. S. (2021). China’s hybrid warfare in the South China Sea. J. Defence Manag. Soc. Sci. Hum. 4:12. doi: 10.58247/JDMSSH-2021-0401-12

Kajee, J. (2025). SeaLight | Gray zone tactics playbook: intrusive surveying. Sea light. Available online at: https://www.sealight.live/posts/gray-zone-tactics-playbook-intrusive-surveys (Accessed June 20, 2025).

Kelly, J. (2014). Coast guards and regional security cooperation. Maritime Stud. 2002, 10–16. doi: 10.1080/07266472.2002.10878689

Kim, S. K. (2022). An international law perspective on the China coast guard law and its implications for maritime security in East Asia. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 37, 241–255. doi: 10.1163/15718085-BJA10089

Koga, K. (2022) Four phases of South China Sea disputes 1990–2020. I. A. Hussain and L. C. Sebastian (I. A. Hussain and L. C. Sebastian Eds.), Global political transitions (pp. 43–160). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lan, H. (2023). Chinese survey vessel Xiang Yang Hong 10’s encroachment on Vietnam s waters: Intention and consequences. Hanoi: Nghien Cuu Bien Dong.

Lan, D. (2025) Chinese ship conducts survey off Vietnam but Hanoi’s state media stays silent. Radio free Asia. Available online at: https://www.rfa.org/english/southchinasea/2025/06/26/vietnam-china-survey-ship/ (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Le Mière, C. (2011a). Policing the waves: maritime paramilitaries in the Asia-Pacific. Survival 53, 133–146. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2011.555607

Le Mière, C. (2011b). The return of gunboat diplomacy. Survival 53, 53–68. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2011.621634

Liu, R., and Hu, Z. (2024). Controversies and amendment proposals on the China coast guard law. Mar. Policy 163:106115. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOL.2024.106115

Luo, S. (2023). From joint development to independent development. Contemp. Southeast Asia. 45, 465–493. doi: 10.1355/cs45-3l

Martinson, R. (2021). Catching sovereignty fish: Chinese fishers in the southern Spratlys. Mar. Policy 125:104372. doi: 10.1016/J.MARPOL.2020.104372

Martinson, R. D., and Dutton, P. A. (2018). China maritime report no. 3: China’s Distant-Ocean survey China maritime report no. 3: China’s Distant-Ocean survey activities: Implications for U.S. national security. Available online at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports (Accessed June 05, 2025).

McCartney, M. (2025). Vietnam intercepts China research ship near coast : Newsweek. Available online at: https://www.newsweek.com/vietnam-protests-china-ocean-research-ship-survey-eez-2096040

McLaughlin, R. (2022). The law of the sea and PRC gray-zone operations in the South China Sea. Am. J. Int. Law 116, 821–835. doi: 10.1017/AJIL.2022.49

Meierding, E. (2017). Joint development in the South China Sea: exploring the prospects of oil and gas cooperation between rivals. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 24, 65–70. doi: 10.1016/J.ERSS.2016.12.014

Mi, L., Zhou, S., Xie, Y., Zhang, G., and Yang, H. (2022). Deep-water oil and gas exploration in northern South China Sea: progress and outlook. Strat. Study Chinese Acad. Eng. 24, 58–65. doi: 10.15302/J-SSCAE-2022.03.007

Morris, L. J. (2017). Blunt defenders of sovereignty: the rise of coast guards of east and Southeast Asia. Nav. War Coll. Rev. 70, 75–112. Available online at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol70/iss2/5/

Mukherjee, B. N. (2022). China’s unilateral claim in the South China and East China Sea: an analytical study. J. Liberty Int. Aff. 8, 399–417. doi: 10.47305/JLIA2283399M

Mumford, A., and Carlucci, P. (2023). Hybrid warfare: the continuation of ambiguity by other means. Eur. J. Int. Secur. 8, 192–206. doi: 10.1017/EIS.2022.19

Nguyen, S. (2023). Chinese ships in territorial waters: Vietnamese government reiterates position : Hanoi Times. Available online at: https://hanoitimes.vn/vietnam-restates-its-stance-towards-chinese-ships-323853.html

Nguyễn, A. C., Phạm, M. T., Nguyễn, V. H., and Tran, B. H. (2024). Explaining the increase of China’s power in the South China Sea through international relation theories. Cogent Arts Humanit. 11:2383107. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2024.2383107

Noferius, A. L., Isnarti, R., and Moenir, H. D. (2020). India’s maritime diplomacy in the Southeast Asia. Dauliyah J. Islamic Int. Affairs 5, 185–219. doi: 10.21111/DAULIYAH.V5I2.4645

Nugraha, M. H. R., and Sudirman, A. (2016). Maritime diplomacy sebagai strategi pembangunan keamanan maritim indonesia. J. Wacana Polit. 1, 175–182. doi: 10.24198/jwp.v1i2.11059

OBG (2017). Vietnam increasingly focused on unexplored oil and gas fields - Vietnam 2017. Oxford: Oxford Business Group.

Ormsbee, M. H. Gray dismay: a strategy to identify and counter gray-zone threats in the South China Sea. (2022) Available online at: https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/gray-dismay-strategy-identify-and-counter-gray-zone-threats-south-china-sea (Accessed May 25, 2025).

Panda, A. (2018). Vietnam requests Spain’s Repsol suspend work in disputed South China Sea oil block. The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2018/03/vietnam-requests-spains-repsol-suspend-work-in-disputed-south-china-sea-oil-block/ (Accessed June 20, 2025).

Patalano, A. (2018). When strategy is ‘hybrid’ and not ‘grey’: reviewing Chinese military and constabulary coercion at sea. Pac. Rev. 31, 811–839. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2018.1513546

Poling, G. B. (2025). Crossroads of competition: China in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. New York: CSIS.

Putra, B. A. (2023a). Rise of constabulary maritime agencies in Southeast Asia: Vietnam’s paragunboat diplomacy in the north Natuna seas. Soc. Sci. 12:241. doi: 10.3390/SOCSCI12040241

Putra, B. A. (2023b). The rise of paragunboat diplomacy as a maritime diplomatic instrument: Indonesia’s constabulary forces and tensions in the north Natuna seas. Asian J. Polit. Sci. 31, 106–124. doi: 10.1080/02185377.2023.2226879

Putra, B. A. (2024a). Malaysia’s “triadic maritime diplomacy” strategy in the South China Sea. All Azimuth 13, 166–192. doi: 10.20991/ALLAZIMUTH.1455442

Putra, B. A. (2024b). Tread with caution: Vietnam’s retaliatory and deference measures Vis-à-Vis assertiveness at sea. Asian J. Polit. Sci. 32, 57–76. doi: 10.1080/02185377.2024.2351390

Raymond, M., and Welch, D. A. (2022). What’s really going on in the South China Sea? J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 41, 214–239. doi: 10.1177/18681034221086291

Reeves, L. (2019). The South China Sea disputes: territorial and maritime differences between the Philippines and China. J. Global Fault. 6, 39–61. doi: 10.13169/JGLOBFAUL.6.1.0039

Rijal, N. K. (2019). Smart maritime diplomacy: diplomasi maritim indonesia menuju poros maritim dunia. J. Glob. Strat. 13, 63–78. doi: 10.20473/jgs.13.1.2019.63-78

Sangtam, A. (2021). Vietnam’s strategic engagement in the South China Sea. Maritime Affairs 17, 41–57. doi: 10.1080/09733159.2021.1939868

Sarjito, A. (2024). China’s gray zone strategy in the South China Sea: tactics, objectives, and regional implications. Indones. J. Multidiscipl. Sci. 3, 113–135. doi: 10.59066/IJOMS.V3I2.559

Searancke, R. (2022). Vietnam: infill drilling to prolong life of field in the Nam con son basin. Upstream. Available online at: https://www.upstreamonline.com/production/vietnam-infill-drilling-to-prolong-life-of-field-in-the-nam-con-son-basin/2-1-1321695 (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Sinaga, L. C. (2016). China’s assertive foreign policy in South China Sea under xi Jinping: its impact on United States and Australian foreign policy. JAS 3:133. doi: 10.21512/jas.v3i2.770

Storey, I. (2014) The Sino-Vietnamese oil rig crisis: Implications for the South China Sea dispute. In ISEAS perspective. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Stubbs, M. T., and Stephens, D. (2017). Dredge your way to China? The legal significance of Chinese reclamation and construction in the South China Sea. Asia Pac. J. Ocean Law Policy 2, 25–51. doi: 10.1163/24519391-00201004

Sutton, H. I. (2021). Illegal strategy: China suspected of Unauthorized Sea floor survey in Pacific : Naval News. Available online at: https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/12/illegal-strategy-china-suspected-of-another-unauthorized-sea-floor-survey/#:~:text=A%20Chinese%20government%20survey%20ship,Sea%20and%20the%20North%20Pacific.

Tarriela, J. T. (2018). Japan: from gunboat diplomacy to coast guard diplomacy. The Diplomat. Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/japan-from-gunboat-diplomacy-to-coast-guard-diplomacy/ (Accessed June 05, 2025).

Tarriela, J. T. (2022). The maritime security roles of coast guards in Southeast Asia. RSIS. Available online at: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/idss/ip22076-the-maritime-security-roles-of-coast-guards-in-southeast-asia/?doing_wp_cron=1676564274.2634689807891845703125#.Y-5XNOzP22o (Accessed June 20, 2025).

Thayer, C. A. (2011). Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea and southeast Asian responses. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 30, 77–104. doi: 10.1177/186810341103000205

Torode, G., and Zhu, C. (2014). China’s oil rig move leaves Vietnam, others looking vulnerable. Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-seas-tensions-idUSBREA4710120140508/ (Accessed May 25, 2025).

TST (2023). Chinese ships leave Vietnam waters after US-China talks : The Straits Times. Available online at: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/chinese-ships-leave-vietnam-waters-after-us-china-talks

Yahuda, M. (2013). China’s new assertiveness in the South China Sea. J. Contemp. China 22, 446–459. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2012.748964

Zhang, K. (2023). Explaining China’s large-scale land reclamation in the South China Sea: timing and rationale. J. Strateg. Stud. 46, 1185–1214. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2022.2040486

Zhang, H., and Bateman, S. (2017). Fishing militia, the securitization of fishery and the South China Sea dispute. Contemp. Southeast Asia 39, 288–314. doi: 10.1355/cs39-2b

Keywords: South China Sea, research ships, maritime diplomacy, grey zone area, Vietnam

Citation: Putra BA (2025) Making waves: marine research vessels in China and Vietnam’s overlapping maritime zones. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1670797. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1670797

Edited by:

Mehran Idris Khan, University of International Business and Economics, ChinaReviewed by:

Nelly Atlan, University of St Andrews, United KingdomZi Yang, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Copyright © 2025 Putra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bama Andika Putra, YmFtYUB1bmhhcy5hYy5pZA==; YmFtYS5wdXRyYUBicmlzdG9sLmFjLnVr

Bama Andika Putra

Bama Andika Putra