- 1Government Modernization and Social Change Research Group, Department of Government Science, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

- 2Department of Public Administration, State University of Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia

- 3Department of Gender and Development Studies, Begum Rokeya University, Rangpur, Bangladesh

Political participation is a key indicator of democratic quality, yet in many developing countries, it remains unevenly distributed across social classes. While existing studies have explored government performance and political participation separately, few have examined how social class moderates the relationship between the two. This study addresses this gap by analyzing Indonesia and Bangladesh, two emerging democracies with comparable postcolonial legacies and agrarian class structures but distinct political trajectories. Using data from the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), regression models with 780 respondents in Indonesia and 1,025 in Bangladesh are employed. Findings show that citizens from higher social classes tend to report more positive perceptions of government performance and participate more in institutional forms of politics, while lower social classes are more likely to engage in non-institutional participation driven by distrust or exclusion. These results demonstrate that social class significantly moderates the relationship between governance perception and participation type, advancing debates in comparative government and democratization by revealing how class-based inequalities shape democratic engagement in the Global South. Policy implications suggest that inclusive participation strategies must be context-specific. In Bangladesh, community-based consultation mechanisms could empower marginalized rural groups, while in Indonesia, targeted digital outreach may reduce barriers for rural lower classes. Despite these contributions, the study is limited by reliance on secondary data and the challenge of fully capturing multidimensional aspects of class beyond agrarian indicators.

1 Introduction

Public participation and perceptions of government performance are key components of democratic governance, influencing both the legitimacy and accountability of political systems (Norris, 1999; Zakhour, 2020). While these phenomena are widely studied, their relationship is moderated by several socio-economic factors, with social class playing a particularly critical role. Social class shapes access to resources, political influence, and civic engagement, thereby affecting how individuals perceive government performance and engage with governance institutions (Bornschier et al., 2021; Muntaner et al., 2020). This study examines the moderating role of social class in influencing perceived government institutional performance and public participation, using Indonesia and Bangladesh as comparative case studies. By doing so, it not only provides empirical cross-national evidence but also refines theories of democratic participation and inequality by showing how class-based differences structure engagement in emerging democracies.

Government performance refers to how well the government meets the needs of its citizens through the provision of services, policy implementation, and overall governance effectiveness (Kim and Im, 2019; Radin, 1998; Yan et al., 2023). Citizens’ perceptions of government performance have been shown to significantly influence their willingness to participate in public affairs (Zhan and You, 2024). Positive perceptions of government performance can lead to higher levels of institutional trust and increased civic engagement in formal governance processes, such as voting and attending community meetings (Wang, 2016). Conversely, negative perceptions often result in political disillusionment, leading to disengagement from formal institutional participation and, in some cases, a shift toward more confrontational forms of participation, such as protests and civil disobedience (Dalton, 2008; Lee, 1992; Swart et al., 2020).

Public participation is a multifaceted concept, encompassing both institutional and non-institutional forms. Institutional participation refers to engagement through formal channels, such as electoral processes or involvement in political parties (Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Wang, 2016). Non-institutional participation, on the other hand, includes more informal activities, such as demonstrations, petitions, or strikes (Marien et al., 2010; Swart et al., 2020; Waeterloos et al., 2024). Both forms of participation are essential for the functioning of a healthy democracy, allowing citizens to express their interests and influence government decision-making. However, access to and engagement in these different forms of participation are often shaped by broader social structures, with social class serving as a critical determinant.

Social class, which can be defined as a grouping of people based on their socio-economic status, including income, education, and occupation, profoundly influences political behavior (Bourdieu, 2023; Lipset, 1981; Van Hamme, 2012). Higher social classes typically have greater access to resources, education, and political networks, which enable them to engage more actively in institutional participation. Lower social classes, on the other hand, often face barriers such as limited education, economic insecurity, and exclusion from political elites, making institutional participation more difficult (Van Hamme, 2012).

Studies on the relationship between social class and public participation suggest that wealthier, more educated individuals are more likely to engage in institutional political activities, while those in lower social strata may turn to non-institutional methods of participation when they perceive institutional channels as unresponsive or inaccessible (Swart et al., 2020). These differences are further compounded by varying perceptions of government performance across social classes. Wealthier individuals may perceive government policies, especially those concerning economic development and investment, more favorably, whereas marginalized groups may view the same policies as exclusionary or detrimental to their well-being (Scott, 1985).

The relationship between social class, government performance, and public participation manifests differently across countries due to variations in political institutions, economic structures, and historical experiences. Both Indonesia and Bangladesh are emerging democracies with complex social class hierarchies shaped by their histories of colonialism, agrarian economies, and transitions to more market-oriented policies. This study adopts a most-similar-systems (MSS) design, both countries share legacies of colonialism and agrarian-based class structures, yet they diverge in institutional configurations and regime trajectories. This makes them analytically significant cases for examining how similar socio-economic foundations produce different dynamics of class-based participation under distinct political institutions.

Although the influence of social class on public participation and perceptions of government performance is well-documented, there remains a need for comparative research that examines how these relationships vary across different political and socio-economic contexts (Gugushvili, 2021). Against this backdrop, the main research question guiding this study is: “How does social class moderate the relationship between government performance and political participation in Indonesia and Bangladesh?” This study aims to fill this gap by focusing on two emerging democracies, Indonesia and Bangladesh, which share similar agrarian-based economies but differ in their political institutions and governance structures. Beyond that, this study advances current debates on democracy and political participation by moving beyond descriptive accounts to show how social class moderates the relationship between citizens’ perceptions of government performance and their participatory choices. In addition to its theoretical contribution, the study also foreshadows its practical relevance: insights on class-based participation offer guidance for designing inclusive governance strategies, such as community consultation mechanisms for marginalized groups or digital outreach to rural lower classes, in emerging democracies of the Global South.

2 Theoretical framework

The theoretical model integrates various theoretical perspectives to understand the multifaceted interactions between social class, government performance, and modes of participation, particularly in the distinct political contexts of Indonesia and Bangladesh (Figure 1).

2.1 Anchoring

Understanding how class shapes political participation and perceptions of government requires engagement with broader theoretical debates. Modernization theory suggests that socioeconomic development fosters democratic participation and stronger trust in government institutions (Inglehart and Welzel, 2012). However, experiences in Indonesia and Bangladesh show that while economic growth and urbanization have expanded opportunities, entrenched inequalities continue to limit lower-class access to institutional politics. This indicates that modernization alone cannot explain the persistence of uneven participation and skepticism toward government performance.

A complementary perspective is class-based mobilization theory, which emphasizes that structural inequalities generate grievances and collective action (Moore, 1969; Tarrow, 2012). In Bangladesh, landless farmers often resort to protests when excluded from formal channels, while in Indonesia, urban informal workers and marginalized communities mobilize against labor precarity and rising inequality. This perspective highlights how class position not only influences whether people participate, but also determines the mode of participation—formal versus contentious. Institutionalist approaches add another layer by showing how political rules and state structures mediate class-based participation (Heras, 2018). Indonesia’s decentralization opened local venues for participation but also enabled elite capture, while Bangladesh’s centralized patronage networks continue to restrict lower-class influence. These differences underscore how institutional design and state capacity shape the ways in which class interests are expressed and how government performance is perceived.

By integrating modernization theory, class-based mobilization, and institutionalism, this study situates its analysis within wider debates on democratization, inequality, and governance. Modernization highlights development-driven opportunities, mobilization explains grievances and contentious politics, and institutionalism reveals the role of political structures in shaping outcomes. These perspectives provide a multidimensional framework for interpreting the relationship between class, participation, and government perceptions in Indonesia and Bangladesh.

2.2 Social class as a moderating variable

Social class is one of the most controversial concepts in the social sciences (Ansar, 2024; Huszár and Füzér, 2023) and there is no fixed number of classes and no predetermined way to apply the class concept in concrete analysis (Pratschke, 2017). However, social class is a fundamental determinant in shaping citizens’ perceptions and interactions with the state. Drawing on Bourdieu’s theory of social distinction (Bourdieu, 2023), social class influences not only economic capital but also social and cultural capital, which together shape individual worldviews, interests, and political behavior.

The diagram illustrates a hierarchical classification of social class, ranging from landlords and capitalist farmers at the top, through petty commodity producers and semi-proletariat farmers, to fully proletariat farmers at the bottom. In this study, the operationalization of class draws on indicators available in the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), particularly education, occupation, and household income, while agrarian ownership and livelihoods are used as contextual anchors for interpreting class stratification in Indonesia and Bangladesh. This dual approach allows us to bridge the survey-based classification with agrarian class theories, ensuring consistency between conceptual debates and empirical measurement.

The social class position refers to Goldthorpe’s Class Theory, which asserts that social class emerges from employment relations in industrial societies (Zou, 2015). Furthermore, in the context of agrarian class – as in the two study area cases – the amount of private land ownership and cultivated land, the amount of agricultural output sold, and the means of production are determinants of social class (Habibi, 2021; Misra, 2017; Wood, 1978). Bourdieu’s multidimensional approach is particularly useful here because it allows the analysis to incorporate not only agrarian land ownership but also cultural and social capital, which are increasingly relevant in urbanizing economies (Bourdieu, 2023). This integration refines the understanding of how class operates across both rural and urban settings. This stratification suggests that individuals from different social classes possess distinct capacities and opportunities to participate in governance and political processes, which affects how they perceive government performance.

The moderating role of social class posits that people’s positions within the economic hierarchy influence their lived experiences and, consequently, their assessments of government performance (Brown-Iannuzzi et al., 2015; Manstead, 2018; Scott, 1985). For example, landlords and capitalist farmers, who benefit from greater land ownership and wealth, may have a more favorable view of government policies that protect property rights and provide agricultural subsidies. Conversely, fully proletariat farmers, who rely solely on labor and lack access to land or capital, may perceive government performance negatively if they feel marginalized or excluded from policymaking processes (Barrington, 2009). In the Indonesian case, this may include rural landless workers excluded from decentralization benefits, while in Bangladesh, it often refers to tenant farmers marginalized by centralized patronage networks. Clarifying these distinctions ensures that the class model is not applied universally but tailored to each national context.

At the same time, the agrarian class hierarchy is not assumed to represent the entirety of society in either country. Rather, it provides a conceptual foundation primarily for rural contexts, while acknowledging that urban classes—such as industrial workers, service sector employees, and informal economy participants—intersect with and complicate these agrarian categories. This clarification highlights the framework’s scope while recognizing its limitations in capturing urban-specific dynamics.

2.3 Perceived government performance

Within this framework, perceived government performance is interpreted through the lens of class-based stratification, meaning that citizens’ evaluations are conditioned by their relative access to resources, institutions, and representation. This class-sensitive view ensures that the theoretical framework remains consistent with the study’s empirical design. Perceived government performance is a subjective evaluation of the effectiveness and responsiveness of government institutions (Yang and Holzer, 2006; Zhang et al., 2022). It is typically influenced by a variety of factors, including the quality of public services, the transparency of decision-making, and the government’s ability to address social and economic inequalities (Grimmelikhuijsen, 2010; Kampen et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2021; Porumbescu, 2017; Van de Walle and Bouckaert, 2003). In other words, it encompasses the public’s assessment of how well the government fulfills its role in delivering services, ensuring public welfare, maintaining law and order, and implementing policy (Holzer and Kloby, 2005). These perceptions are influenced by both tangible outcomes, such as the provision of public goods and economic stability, as well as intangible factors, such as trust in government officials, transparency, and the perceived legitimacy of government actions (Kalsum et al., 2024; Van de Walle and Bouckaert, 2003).

In the context of democratic governance, perceived government performance plays a critical role in shaping political attitudes and behavior. Positive evaluations of government performance are often associated with higher levels of trust in political institutions, greater civic engagement, and support for the current political order (Aitalieva and Morelock, 2019; Wang, 2016; Zhang et al., 2022). On the other hand, negative perceptions can lead to political disillusionment, alienation, and even participation in anti-government protests or other forms of non-institutional public participation (Marien et al., 2010; Waeterloos et al., 2024). We categorize perceived government performance into two broad categories: positive and negative perceptions. Positive perceptions arise when government actions are viewed as beneficial and inclusive, whereas negative perceptions result from perceived failures or biased policies that favor certain social classes over others.

Social class position acts as a filter through which individuals interpret government actions (Kraus et al., 2012; Manstead, 2018). The relationship between social class and perceived government performance is particularly relevant in understanding political dynamics in developing countries like Indonesia and Bangladesh, where socio-economic inequalities are pronounced. Higher social classes, such as wealthy landowners and capitalist farmers, often perceive government performance positively, as state policies may favor their economic interests through land ownership protections, subsidies, and business-friendly regulations (Rigg, 2007). In contrast, lower social classes, such as small farmers or the urban poor, may view government performance more negatively, especially if they feel marginalized by policies that do not address their needs or if they experience barriers to accessing government services (Habibi, 2021; Hadiz, 2004). This divergence in perceptions is critical in understanding how social class moderates the relationship between government performance and public participation in varying political contexts.

2.4 Public participation: institutional vs. non-institutional forms

Public participation in political and governance processes is critical to democratic governance and reflects citizens’ engagement with the state. It can take two primary forms: institutional and non-institutional participation. Institutional participation includes formal activities such as voting, attending community meetings, or joining political parties (Dalton, 2022; Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Sairambay, 2020). In contrast, non-institutional participation encompasses informal, often more confrontational activities such as protests, boycotts, and other forms of civil disobedience (ElSayed, 2022; Ma and Cao, 2023).

The study posits that social class shapes not only perceptions of government performance but also preferences for modes of participation. Higher social classes, such as landlords and capitalist farmers, with more access to economic and political resources, are more likely to participate in institutional forms (Yoder, 2020). This is because they often have more to gain from maintaining the status quo and influencing policy through formal channels. Conversely, lower social classes, such as fully proletariat farmers, may find institutional participation less effective or accessible due to barriers such as low literacy, limited social networks, or mistrust in formal institutions (Muntaner et al., 2020). As a result, they may be more inclined toward non-institutional forms of participation to voice their discontent and demand change (Kestner, 2022).

This class-based divergence in participation modes is particularly pronounced in developing democracies like Indonesia and Bangladesh, where socio-economic inequalities are stark, and political power is often concentrated in the hands of a small elite. In both countries, institutional participation is typically dominated by wealthier citizens, while lower-class individuals are more likely to engage in non-institutional participation, particularly when they perceive the government as unresponsive or corrupt (Hossain, 2022; Lewis and Hossain, 2022; Hadiz and Robison, 2013; Warburton et al., 2021). This divergence underscores the importance of considering social class as a moderating factor in the relationship between government performance and public participation.

This study contributes theoretically by extending class-participation debates into agrarian democracies of the Global South. It shows how social class not only differentiates participation modes but also moderates the perception–participation link in ways that are sensitive to institutional design and agrarian legacies. This novelty lies in integrating established class theories with the empirical realities of Indonesia and Bangladesh, thereby refining comparative understandings of democracy and inequality.

3 Methods

3.1 Study areas

Indonesia and Bangladesh provide important comparative cases for examining how social class shapes government performance perceptions and modes of political participation. Both countries share legacies of colonialism, agrarian-based economies, and contested democratization trajectories, yet they differ in institutional design and political outcomes. This makes them suitable cases for comparative inquiry, as the combination of similarities and contrasts offers analytical leverage in exploring class–state relations (Aspinall and Berenschot, 2019; DeVotta et al., 2024). In methodological terms, these contrasts enable a most-similar-systems logic: both are agrarian, postcolonial democracies, yet their divergent institutional trajectories provide leverage to test how class moderates the relationship between government performance and participation.

In Indonesia, the legacy of Dutch colonial land policies and Suharto’s New Order regime has left enduring imprints on class structures and patterns of governance (Chandra, 2017; Hadiz and Robison, 2004). Agrarian reforms were uneven, and the decentralization process after 1998 created both opportunities for participation and new forms of elite capture at the local level (Buehler, 2010). Social class divisions in rural Indonesia thus remain pronounced, with wealthy landlords and capitalist farmers often dominating formal politics, while smallholders and landless farmers face barriers to meaningful participation (Habibi, 2021, 2023; Nurlinah et al., 2024). The focus on rural populations is methodologically relevant because class distinctions are sharper and more enduring in agrarian settings, making them particularly useful for testing theories of inequality and participation.

In Bangladesh, class and politics are deeply intertwined with the colonial zamindari system and its post-independence transformations. Land concentration and clientelist politics have enabled rural elites to maintain strong control over state institutions, often at the expense of poorer farmers and the urban working class (Jahan, 2015). While the Awami League (AL) has historically positioned itself as a populist force, its recent trajectory has combined authoritarian consolidation with pro-market economic policies and co-optation of religious groups (DeVotta et al., 2024). This has reinforced inequalities in access to institutional channels, pushing marginalized groups to rely more on non-institutional participation such as protests and grassroots mobilization (Jackman, 2021).

Recent political developments further strengthen the rationale for studying Bangladesh. The resignation of Sheikh Hasina in August 2024 after mass protests marked a turning point, with the interim government led by Muhammad Yunus launching constitutional and electoral reforms aimed at restoring accountability and participation (Hossain, 2025). These changes provide a unique window into how shifts in political regimes recalibrate class dynamics, participation modes, and perceptions of government performance. While the time gap between Indonesia’s ABS Wave 6 (2025) and Bangladesh’s ABS Wave 2 (2017) introduces potential comparability challenges, the focus on structural class–participation linkages (which evolve more slowly than short-term political conditions) provides justification for cross-national analysis. Nonetheless, this limitation is acknowledged and interpreted cautiously.

3.2 Variables and measures

Table 1 outlines the variables and indicators used in this study, along with the corresponding measurement scales. The independent variable, perceived government performance, captures citizens’ subjective evaluations of how well their government performs in terms of economic management, democratic governance, and democratic satisfaction. Economic and democratic performance were assessed using a 5-point scale ranging from very bad (1) to very good (5), while satisfaction with democracy was measured on a similar 5-point scale from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (5). These measures were adapted from cross-national governance studies and have demonstrated reliability in capturing public perception of institutional effectiveness (Norris, 2011; Sørensen and Torfing, 2021).

The moderating variable, class position, was conceptualized differently in each country to reflect contextual nuances. In Bangladesh, class position was categorized based on occupational hierarchy: Sub-ordinate, Middle, and Dominant. In contrast, the Indonesian context employed the terms Elite and Mass, reflecting broader socio-political divisions in occupational and power structures. This classification builds upon contextualized interpretations of class in Global South societies (Habibi, 2021; Moore, 2018). Although asymmetrical, both classifications map onto the theoretical framework: “Elite/Dominant” reflect ownership of economic and cultural capital, “Mass/Sub-ordinate” capture limited access to such resources, and “Middle” denotes intermediate groups. This alignment allows for theoretically consistent cross-national comparison, despite contextual variation.

The dependent variables focus on two dimensions of political engagement: institutional and non-institutional participation. Institutional participation was measured through five indicators, including voting behavior, attendance at campaign meetings, efforts to persuade others during elections, interest in politics, and frequency of following political news. Items used both binary responses (e.g., yes or no for voting and campaign attendance) and ordinal scales (e.g., a 5-point scale for political interest ranging from not at all interested to very interested). These items capture core aspects of democratic engagement as outlined by participation theories (Åström, 2019; Ekman and Amnå, 2012).

Non-institutional participation was measured by assessing individuals’ involvement in informal and often grassroots forms of activism. Respondents were asked whether they had contacted influential individuals, the media, signed petitions, attended protests, or participated in other political actions. All five indicators were measured using binary responses (yes or no), capturing whether the respondent had engaged in each activity. These indicators reflect unconventional yet increasingly prevalent forms of civic participation, particularly in emerging democracies (Dalton, 2017; Rodan, 2018).

To mitigate potential confounding effects, the study incorporated control variables that are well-established predictors of political behavior: age (measured continuously in years), gender (female or male), and educational attainment (measured continuously in years of schooling). These demographic factors are consistently associated with variations in political trust and participation, particularly in diverse socio-political environments of the Global South (Ansar, 2024; Marien et al., 2010).

3.3 Data source and sampling

This study utilized cross-national survey data from the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) were drawn from the Sixth Wave (Wave 6) of the ABS for Indonesia, released in March 2025, and the Second Wave (Wave 2) for Bangladesh, which became publicly available in May 2017 (accessible).1 The ABS adopts a national probability sampling design to ensure that every adult citizen has an equal chance of selection. The sampling framework relies on either census household lists or multistage area probability approaches, with stratification and weighting used to guarantee coverage of rural areas and minority populations (Chu et al., 2020; Dalton and Shin, 2014). As a result, ABS samples are widely recognized as representative of the adult, voting-age population in each participating country.

From these nationally representative datasets, this study focuses only on rural respondents. The resulting analytic sample consists of 1,028 respondents in Bangladesh and 780 in Indonesia. Although smaller than the original national samples (approximately 1,200 respondents per country), these sub-samples remain statistically adequate for robust analysis. According to survey methodology standards, a sample size of around 400 is typically sufficient to achieve a 95% confidence level with a margin of error of ±5% (Creswell and Creswell, 2017; Krejcie and Morgan, 1970). Thus, the rural subsamples in this study exceed the minimum threshold and allow valid inferential comparisons across the two countries. The methodological rigor of ABS further strengthens the validity of the data. ABS employs standardized questionnaires tested for construct validity, intensive interviewer training, careful translation procedures, and strict fieldwork supervision to maintain data quality (Miao et al., 2024). Consequently, even when filtered for rural populations, the datasets used in this study retain representativeness and comparability across national contexts.

This focus is justified methodologically, as rural areas remain central to both countries’ demographic profiles (e.g., around 43% of Indonesians and 62% of Bangladeshis reside in rural areas according to BPS 2023 and BBS 2023). Hence, rural samples capture the social contexts where class dynamics and agrarian inequality are most visible.

3.4 Data analysis

The analysis used an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model to quantify the impact of perceived government performance on public participation, focusing on class position as a moderating factor (Brambor et al., 2006). Although several dependent variables are binary, we employed the linear probability model for interpretability and comparability across models. This approach provides coefficients that can be directly interpreted as percentage-point changes in participation likelihood. While logistic regression is often preferred, linear probability models remain widely used in political science when clarity of interpretation is prioritized (Angrist and Pischke, 2009).

The analysis was performed to explore the moderating effects of social class position on government performance and institutional political participation as well as non-institutional political participation in Indonesia (Equation 1) and Bangladesh (Equation 2). Perceived government performance was operationalized through three indicators: economic performance, democratic governance, and satisfaction with democracy. These dimensions were selected because they are the only consistently available and comparable items across both ABS waves, and they correspond directly to the theoretical framework’s emphasis on economic outcomes and institutional legitimacy. Other dimensions such as service delivery or corruption, while important, were unavailable in both datasets; hence, our measures capture the most robust cross-nationally comparable indicators.

Interaction terms (e.g., government performance × class position) are interpreted as conditional effects, indicating whether the influence of government performance on participation is amplified or attenuated by class. For instance, we expect higher classes to show stronger responsiveness to positive performance evaluations, while lower classes may react more critically or resort to non-institutional modes. This aligns the methodological design with the study’s research question.

Where is public participation, is an indicator of digital transformation, are social class positions for the Indonesian case, and are dummy social classes for the Bangladesh case. and are the intercept terms, and are the slope coefficients for institutional and non-institutional public participation, are the covariates, and is the random error term.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Profile of respondents

Table 2 shows the socio-demographic profile of respondents from Indonesia (n = 780) and Bangladesh (n = 1,028). While the samples are broadly comparable in gender composition, Indonesia’s respondents tend to be older and possess somewhat higher levels of formal education compared to Bangladesh. These differences are important contextual factors that may shape variations in perceptions of government performance and patterns of political participation examined in subsequent sections. In terms of age, the average age of Indonesian respondents is 43.99 years (SD = 14.17), ranging from 17 to 84 years. By contrast, respondents in Bangladesh are slightly younger on average, with a mean age of 40.74 years (SD = 15.17), and a broader range between 18 and 95 years. This suggests that the Bangladeshi sample captures a relatively younger population segment compared to Indonesia, while also including respondents at the higher end of the age spectrum.

Education levels reveal further differences between the two countries. In Indonesia, the mean years of schooling is 8.03 (SD = 3.94), with values ranging from no formal education (0 years) to a maximum of 18 years. In Bangladesh, the average educational attainment is lower at 7.04 years (SD = 6.76), though the range is similarly wide (0–18 years). This indicates that, while both samples include respondents across the full spectrum of educational backgrounds, Indonesian respondents on average have slightly higher levels of formal education. Gender distribution in both countries is relatively balanced, though with minor variations. In Indonesia, the sample is evenly split between male (50%) and female respondents (50%). In Bangladesh, males make up a slightly higher proportion (50.97%) compared to females (49.03%). The near gender parity in both samples underscores the representativeness of the survey in capturing perspectives across genders.

4.2 Descriptive analysis

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of class configuration and public participation indicators in Indonesia and Bangladesh. In terms of perceived government economic performance, the data reveal a notable contrast between Indonesia and Bangladesh. The mean score in Indonesia stands at 2.35 with a median of 3.00, while in Bangladesh the mean is significantly higher at 3.11, also with a median of 3.00. Although both countries report similar central tendencies, the higher standard deviation in Bangladesh (1.52) compared to Indonesia (1.22) suggests greater variability in citizen satisfaction. The broader range in Bangladesh (from 1.00 to 9.00) further emphasizes this disparity, indicating the presence of both highly dissatisfied and extremely satisfied individuals. In contrast, Indonesia’s narrower range (1.00–5.00) reflects a more consistent and bounded perception, potentially pointing to a more stable but less optimistic view of economic governance.

When assessing democratic performance, a reversed pattern emerges. Indonesia records a substantially higher mean score of 3.64 (median 4.00), indicating strong approval of the democratic system among its citizens. In Bangladesh, however, the mean drops to 2.76 with a median of 3.00, suggesting a more critical or cautious public sentiment. The standard deviation in Bangladesh (1.21) again points to wider opinion dispersion compared to Indonesia (0.62), where responses appear more consolidated and positive. This suggests that, while economic performance is viewed more favorably in Bangladesh, the democratic system garners greater support in Indonesia.

This trend is further reflected in citizens’ satisfaction with democracy, where the mean score in Bangladesh rises to 3.75 (median 4.00), contrasting with a lower mean of 2.65 in Indonesia (median 3.00). Despite this apparent paradox, it is important to consider the broader interpretation: while Indonesians may rate democratic processes highly in terms of functioning, their personal satisfaction may be tempered by factors such as inequality, inefficiency, or perceived lack of responsiveness. Conversely, Bangladeshi citizens may be more critical of democratic mechanisms but still express satisfaction, potentially due to recent reforms or improvements in governance.

Cumulative government performance consolidates these perspectives. Indonesia scores an average of 2.88 with a relatively low standard deviation (0.57), reflecting consistent moderate views. Bangladesh scores higher at 3.21, but with greater variability (SD = 0.89) and a wider value range (1.66–6.33), suggesting a more polarized public opinion. These results indicate that while perceptions of government are generally higher in Bangladesh, they are also more fragmented, whereas Indonesian views are more centered and homogeneous.

Turning to indicators of political participation, Indonesia again exhibits slightly higher participation. The Institutional Participation (IPP) index in Indonesia is 1.91 with a standard deviation of 0.30, compared to Bangladesh’s mean of 1.83 (SD = 0.41). While both countries demonstrate relatively high levels of participation, Indonesia shows a more uniform participation across respondents, indicated by the narrower spread of values. This suggests that political activism may be more evenly distributed within Indonesian society. In contrast, the Non-Institutional Political Participation (NIPP) index reveals a stark difference. Indonesia scores significantly higher with a mean of 1.61 (median 1.00), whereas Bangladesh’s mean is only 0.34 (median 0.00). This discrepancy highlights a stronger inclination among Indonesians to engage in non-traditional forms of political activity, such as protests, petitions, or online activism. The higher maximum value (2.00 in both cases) juxtaposed with Bangladesh’s much lower mean and higher standard deviation (0.73) indicates that such activities are more sporadic and less normalized in Bangladesh.

The data on class position configuration also revealed key socio-political patterns. In Indonesia, the population is overwhelmingly classified as mass (85%), with a minority (15%) identified as elite. This distribution underscores the predominance of a broad-based citizenry with limited access to elite political or economic power. In Bangladesh, however, the classification shows a more differentiated structure: a dominant sub-ordinate class (79%), a small middle class (6%), and a notable dominant class (15%). This suggests a sharper class division in Bangladesh, with a more pronounced presence of both marginalized and elite groups, which may reflect deeper systemic inequalities in access to resources and political representation.

It is important to note that the binary classification used in Indonesia (elite vs. mass) may conflate heterogeneous groups. For instance, the “mass” category could encompass both relatively secure middle-class citizens and more precarious lower-class groups. This aggregation may obscure internal variations in participation patterns, such as the middle class being more inclined toward non-institutional activism while poorer citizens remain disengaged. By contrast, the three-tier classification in Bangladesh allows for a more fine-grained observation of such dynamics. Thus, while the Indonesian data reveal useful contrasts between elite and non-elite groups, the broader category may mask intra-group differences that could partly explain the weaker statistical associations observed in Indonesia.

4.3 Regression analysis

4.3.1 Institutional public participation

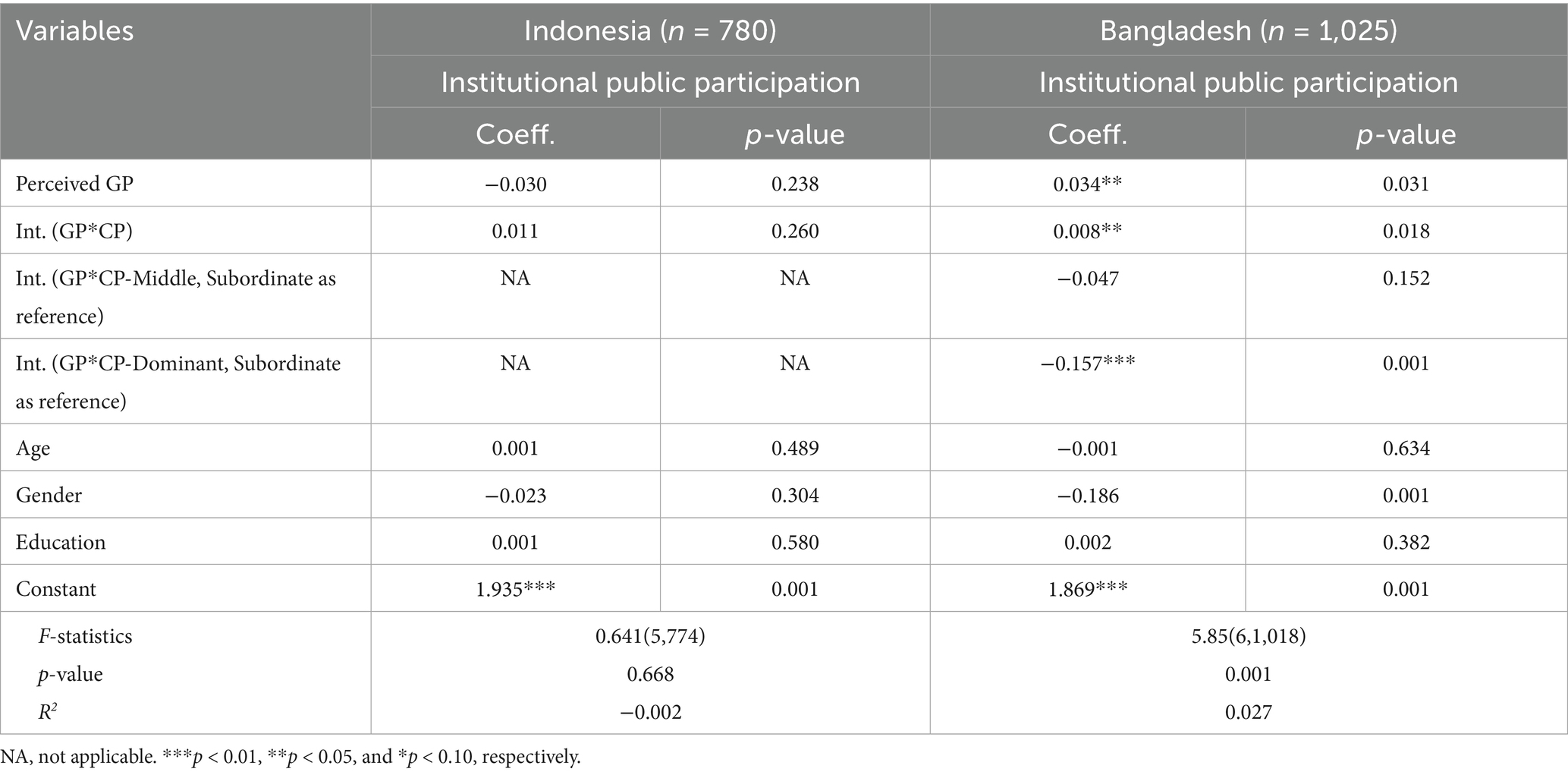

Table 4 presents the results of an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis. In Indonesia, the coefficient for GP is −0.030 and is not statistically significant. This suggests that how people perceive government performance does not have a meaningful impact on their participation in formal institutions. One possible explanation is that in Indonesia, even when citizens view institutions positively, this perception does not necessarily lead to higher engagement or involvement. This aligns with previous studies showing that in some contexts, public trust or positive views of government institutions do not automatically translate into active participation (Dalton, 2017; Megawati et al., 2025; Rusli et al., 2023).

Table 4. The effects of perceived government institutional performance on institutional public participation, moderated by class position: ordinary least squares (OLS).

In contrast, in Bangladesh, the coefficient for GP is 0.034 and is statistically significant (p = 0.031). This means that people who perceive government institutions more positively are slightly more likely to participate in formal political or civic activities. Although the effect is small, it highlights that in Bangladesh, institutional trust may encourage greater involvement in institutional forms of participation, possibly reflecting a more responsive or mobilized civil society (Jamil and Baniamin, 2021; Sarker and Islam, 2017).

The study also showed important differences when looking at class position as a moderating variable. In Indonesia, the interaction between GP and class position is not significant (p = 0.260), suggesting that whether someone belongs to a mass or elite class does not change the effect of perceived institutional performance on their participation. However, in Bangladesh, the interaction between GP and class is significant (p = 0.018), indicating that class plays a role in shaping how people respond to institutional performance. Specifically, for people in the dominant class, the effect of GP on participation is negative and significant (coefficient = −0.157, p = 0.001). This means that when dominant class individuals perceive institutions as functioning well, they are less likely to participate. This may be because they already benefit from the system and feel no need to engage further, or they may use different, informal channels to influence decisions (Qayums, 2021; Sarker and Islam, 2017). On the other hand, this relationship is not significant for the middle class (p = 0.152), meaning their participation is not clearly affected by institutional performance.

Other demographic variables show mixed results. In both countries, age and education have no significant impact on institutional participation. However, gender has a significant negative effect in Bangladesh (p = 0.001), suggesting that women are less likely to participate in institutional settings compared to men. In Indonesia, gender is not a significant factor (p = 0.304). Looking at the model fit, the results are much stronger in Bangladesh. The model explains a small but meaningful portion of the variance in participation (R2 = 0.027), and the overall model is statistically significant (F = 5.85, p = 0.001). In contrast, the model for Indonesia is weak (R2 = −0.002), and the F-statistic is not significant (F = 0.641, p = 0.668), indicating that the model does not explain participation behavior well in the Indonesian case.

4.3.2 Non-institutional public participation

The study revealed important differences between the two countries. In Indonesia, higher perceived institutional performance discourages non-institutional participation, especially among the upper classes. This suggests that institutional trust may reduce the perceived need for protest or informal political action, particularly among those with more social capital. In Bangladesh, however, perceptions of government institutions and class position do not significantly influence non-institutional participation, suggesting that other factors may be more influential in shaping public activism in that context.

Table 5 explores non-institutional public participation terms, In Indonesia, the coefficient for perceived GP is negative and statistically significant (coefficient = −0.039, p = 0.038). This indicates that individuals who view government institutions more favorably are less likely to engage in non-institutional forms of participation. This is a noteworthy finding and suggests that when people trust institutions or perceive them as effective, they may feel less need to express their demands or dissatisfaction through informal or disruptive means. This relationship is reinforced by a significant negative interaction between GP and class position (coefficient = −0.016, p = 0.035), implying that the discouraging effect of positive institutional perception on non-institutional participation is stronger among higher classes. In other words, as people in more advantaged positions gain trust in government, they are even less likely to engage in non-institutional political behavior (Al Izzati et al., 2024; Mahmud, 2021; Syamsu et al., 2025).

Table 5. The effects of perceived government institutional performance on non-institutional public participation, moderated by class position: ordinary least squares (OLS).

In contrast, in Bangladesh, the relationship between perceived GP and non-institutional participation is not significant (coefficient = 0.003, p = 0.781). This suggests that in Bangladesh, citizens’ views of government performance do not substantially influence their likelihood of engaging in non-institutional forms of political participation. Similarly, the interaction terms for class position in Bangladesh (both middle and dominant classes compared to the subordinate class) are also statistically insignificant (p = 0.880 and p = 0.781, respectively). This indicates that class position does not significantly alter the impact of GP on non-institutional participation in the Bangladeshi context (Jamil and Baniamin, 2021; Mahmud, 2021; Waheduzzaman et al., 2018).

Looking at demographic variables, some patterns are consistent across both countries. Education is positively and significantly associated with non-institutional participation in both Indonesia (p = 0.037) and Bangladesh (p = 0.027), meaning more educated individuals are more likely to take part in such activities. This finding aligns with the broader literature suggesting that education enhances political awareness and the capacity to organize or participate in collective action (Ahlskog, 2021; Le and Nguyen, 2021).

Gender shows a significant effect only in Bangladesh, where women are significantly less likely to engage in non-institutional participation compared to men (coefficient = −0.193, p = 0.001). This may reflect broader gender disparities in civic engagement and access to public spaces (Dalton, 2017). In Indonesia, gender and age have no significant effects on non-institutional participation.

Regarding model fit, both models explain a small but statistically significant portion of the variance in non-institutional participation. In Indonesia, the model reaches significance (p = 0.031), though the R2 value is quite low (0.008), indicating limited explanatory power. Similarly, in Bangladesh, the model is statistically significant (p = 0.001) with a slightly higher R2 value of 0.019.

4.3.3 Theoretical integration

The empirical patterns not only reveal important differences between Indonesia and Bangladesh but also invite reflection on how well existing theories account for the dynamics of class, participation, and governance in these two contexts. From the perspective of modernization theory, the expectation is that socioeconomic development and institutional trust should stimulate greater citizen involvement (Inglehart and Welzel, 2012). Yet the Indonesian case challenges this assumption. Despite relatively higher levels of democratic consolidation and economic development, perceptions of government performance do not significantly influence institutional participation. This suggests that modernization alone cannot explain participation dynamics, and that entrenched inequality and political disengagement may limit the translation of development gains into citizen action. In contrast, Bangladesh shows a modest but positive effect of government performance on institutional participation, supporting modernization claims that institutional trust can mobilize citizens toward engagement.

Class-based mobilization theory further clarifies these patterns. In Indonesia, individuals from higher classes who perceive government performance positively are less inclined to participate in non-institutional activities. This aligns with the idea that elites, already benefiting from the system, have fewer incentives to engage in contentious forms of politics (Moore, 1969; Tarrow, 2012). By contrast, mass-class citizens in Indonesia continue to rely on non-institutional channels such as protests or online activism, reflecting mobilization driven by structural inequalities and unmet grievances. In Bangladesh, however, class position does not significantly moderate the relationship between perceptions and participation, underscoring the constraints of mobilization in a highly centralized and patronage-driven system where class grievances may not easily translate into collective political action.

Institutionalism provides an additional lens to interpret these findings. Indonesia’s post-decentralization political order has opened up more avenues for citizen participation, even if elite capture persists (Heras, 2018). This institutional context helps explain why participation is more evenly distributed and why non-institutional activities are relatively more common. In Bangladesh, the persistence of centralized patronage networks restricts lower-class influence and results in narrower channels for civic engagement, which may account for the weaker associations between government performance, class, and participation. These institutional differences highlight how political structures shape the ways class-based interests are expressed and mediated.

The findings contribute to broader debates by demonstrating that theories of modernization, class-based mobilization, and institutionalism each explain parts of the participation puzzle but fall short when applied in isolation. Modernization explains trust-driven engagement in Bangladesh but not in Indonesia; mobilization clarifies why elites disengage from contentious politics in Indonesia, yet fails to account for the limited class effect in Bangladesh; and institutionalism reveals how structural opportunities and constraints mediate both. By integrating these perspectives, the study shows that political participation is contingent on the intersection of class structure, institutional design, and government performance, thereby extending existing theories of class politics and participatory democracy to the contexts of Indonesia and Bangladesh.

At the same time, the cross-national comparison is shaped by differences in how class positions were operationalized. Indonesia’s binary categorization highlights the broad distinction between elites and the general population but may understate the role of the middle class as a potential driver of protest or informal participation. Bangladesh’s three-tier structure provides more nuance, capturing the layered nature of class influence. Acknowledging this limitation helps clarify that part of the divergence in results may stem from measurement choices rather than solely from substantive contextual differences.

5 Limitations and contributions

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, the focus on Indonesia and Bangladesh limits generalizability, though both represent illustrative cases of Global South democracies where agrarian-based class structures remain important. Second, reliance on ABS self-reports raises risks of bias: in Bangladesh due to political sensitivity and in Indonesia due to cultural norms of over reporting participation. Third, the class classification differs across cases (binary in Indonesia, three-tier in Bangladesh), which may obscure intra-group variation in Indonesia’s “Mass” category. Fourth, the time gap between ABS Wave 6 (Indonesia 2025) and Wave 2 (Bangladesh 2017) may reduce comparability, and the relatively low explanatory power of models (low R2) suggests unmeasured factors also shape participation.

Despite these limitations, the study makes important analytical, theoretical, and practical contributions. Analytically, it demonstrates that social class is not simply a background variable but operates as a moderating mechanism that shapes how citizens’ perceptions of government performance translate into political participation. This adds nuance to existing scholarship by showing that institutional trust and engagement with the state are not uniformly experienced across society but are mediated by structural inequalities. In this sense, the study advances a more refined understanding of the linkages between class position, evaluative judgments of government, and participatory choices in democratizing contexts.

Comparatively, the research enriches the discourse in political science by juxtaposing Indonesia and Bangladesh as strategic cases of emerging democracies in the Global South. Indonesia represents a decentralized system with strong subnational variation yet persistent elite capture, while Bangladesh embodies a more centralized patronage-based system. By analyzing how class dynamics operate within these distinct institutional environments, the study highlights the interplay between social hierarchies and institutional design in shaping political behavior. This comparative perspective contributes to broader debates on democracy and governance by illustrating that the effects of class on participation are contingent on institutional contexts and modes of state–society interaction. Practically, it offers strategies for more inclusive participation. For example, in Indonesia through village deliberation forums (musyawarah desa), and in Bangladesh through informal associations, complemented by civic education, rural outreach, and digital platforms to amplify marginalized voices.

6 Conclusion

This study explores the relationship between social class, government performance, and citizen participation in Indonesia and Bangladesh. It reveals distinct cross-country patterns: in Indonesia, perceptions of government performance do not significantly affect institutional participation but are associated with reduced non-institutional participation, while in Bangladesh positive perceptions strengthen institutional participation but show no clear effect on non-institutional modes. It reveals that social class significantly influences how citizens perceive government performance and how they engage in political participation. The interpretation of these findings must be read with caution, as class was categorized differently across contexts (Elite vs. Mass in Indonesia and three-tier in Bangladesh), which may partly shape the observed variations. The comparative approach provides insights into the ways different social classes in these countries interact with government institutions and participate in civic activities. By linking social class theories with perceptions of governance and political engagement, the research demonstrates both the continued relevance of agrarian-based class models and the need to adapt them to account for emerging rural–urban hybrid dynamics, showing how elites and non-elites respond differently to state performance.

Despite its limitations, including the narrow focus on two countries and potential biases in the self-reported data, such as social desirability in politically sensitive contexts and fear of reprisal in semi-authoritarian environments, the study makes valuable contributions. It helps expand the understanding of how citizens’ trust in government is shaped not only by government actions but also by their socio-economic position. The findings emphasize that a one-size-fits-all approach to fostering citizen participation is inadequate, as lower social classes often face structural barriers to involvement in political processes. In Indonesia, for example, village deliberation meetings (musyawarah desa) offer a formal arena where class-based differences influence citizen input into development planning, while in Bangladesh grassroots mobilizations and civil society networks represent important non-institutional strategies for participation. This calls for more tailored strategies that address the specific needs of various social groups.

The practical implications of this study are significant for policymakers in both Indonesia and Bangladesh. It underscores the need for inclusive and responsive policies that encourage citizen participation across all social classes. Future studies should expand to more diverse regions to see whether similar class-based patterns of political participation are found elsewhere. Priority should be given to addressing the time gap between ABS datasets (2017 vs. 2025), refining class operationalization to better capture middle-class dynamics, and incorporating urban–rural comparisons. A comparative approach between countries with different political systems or levels of decentralization could offer deeper insights into how institutional settings influence the relationship between social class, perceptions of government, and citizen engagement. In addition, future research could examine how other factors, such as urban–rural status, interact with class to shape participation. Longitudinal and experimental designs are also needed to trace how these dynamics evolve over time and to test tailored interventions, including digital platforms or gender-sensitive civic education, that can reduce class-based gaps in participation.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.asianbarometer.org/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Min-hua Huang, Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

N: Project administration, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MA: Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. SM: Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. KC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research was funded by the Institute for Research and Community Service (LPPM) Universitas Hasanuddin (Grant no. 02124/UN4.22/PT.01.03/2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of data from the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS), a collaborative research project conducted by academics from across Asia. The ABS provided valuable data that served as a critical foundation for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Ahlskog, R. (2021). Education and voter turnout revisited: evidence from a Swedish twin sample with validated turnout data. Elect. Stud. 69:102186. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102186

Aitalieva, N. R., and Morelock, A. L. (2019). Citizens’ perceptions of government policy success: a cross-national study. J. Public Nonprofit Aff. 5, 198–216. doi: 10.20899/jpna.5.2.198-216

Al Izzati, R., Dartanto, T., Suryadarma, D., and Suryahadi, A. (2024). Direct elections and trust in state and political institutions: evidence from Indonesia’s election reform. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 85:102572. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2024.102572

Angrist, J. D., and Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton university press.

Ansar, M. C. (2024). Marxism and class-based analysis in the body of knowledge: the scientometric analysis and research agenda. Glocal Society J 1, 14–30. doi: 10.31947/gs.v1i1.35414

Aspinall, E., and Berenschot, W. (2019). Democracy for Sale: elections, Clientelism, and the state in Indonesia. 1st Edn. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. 330.

Åström, J. (2019). “Citizen Participation” in The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of urban and regional studies. ed. A. M. Orum (Amsterdam: Wiley), 1–4.

Barrington, L. (2009). Comparative politics: structures and choices 2nd Edn. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. 592.

Bornschier, S., Häusermann, S., Zollinger, D., and Colombo, C. (2021). How “us” and “them” relates to voting behavior—social structure, social identities, and electoral choice. Comp. Pol. Stud. 54, 2087–2122. doi: 10.1177/0010414021997504

Bourdieu, P. (2023). “Distinction” in Social theory re-wired. eds. W. Longhofer and D. Winchester (London: Routledge), 177–192.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., and Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: improving empirical analyses. Polit. Anal. 14, 63–82. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpi014

Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., Lundberg, K. B., Kay, A. C., and Payne, B. K. (2015). Subjective status shapes political preferences. Psychol. Sci. 26, 15–26. doi: 10.1177/0956797614553947

Buehler, M. (2010). “Decentralisation and local democracy in Indonesia: the marginalisation of the public sphere” in Problems of democratisation in Indonesia: Elections, institutions and society. eds. E. Aspinall and M. Mietzner (New York, NY: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute), 267–285.

Chandra, S. (2017). Economic change in modern Indonesia: colonial and post-colonial comparisons. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 53, 95–97. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2016.1235493

Chu, Z., Rathbun, S. L., and Li, S. (2020). Matching in Selective and Balanced Representation Space for Treatment Effects Estimation. Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management. 205–214. doi: 10.1145/3340531.3412037

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edn. London: Sage Publications. 270.

Dalton, R. J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Polit. Stud. 56, 76–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

Dalton, R. J. (2017). The participation gap: Social status and political inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dalton, R. J. (2022). Political action, protest, and the functioning of democratic governance. Am. Behav. Sci. 66, 533–550. doi: 10.1177/00027642211021624

Dalton, R., and Shin, D. (2014). Growing up Democratic: Generational Change in East Asian Democracies. Jpn. J. Political Sci., 15, 345–372. doi: 10.1017/S1468109914000140

DeVotta, N., Kirk, J., Malik, A., Riaz, A., Adhikari, P., Lawoti, M., et al. (2024). An introduction to south Asian politics. 2nd Edn. London: Routledge. 234.

Ekman, J., and Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: towards a new typology. Hum. Aff. 22, 283–300. doi: 10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

ElSayed, M. (2022). Why people protest: Explaining participation in collective action. Colchester: University of Essex.

Grimmelikhuijsen, S. G. (2010). Transparency of public decision-making: towards trust in local government? Policy Internet 2, 5–35. doi: 10.2202/1944-2866.1024

Gugushvili, A. (2021). Which socio-economic comparison groups do individuals choose and why? Eur. Soc. 23, 437–463. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1793214

Habibi, M. (2021). Masters of the countryside and their enemies: class dynamics of agrarian change in rural Java. J. Agrar. Change 21, 720–746. doi: 10.1111/joac.12433

Hadiz, V. R. (2004). Decentralization and democracy in Indonesia: a critique of neo-institutionalist perspectives. Dev. Change 35, 697–718. doi: 10.1111/j.0012-155X.2004.00376.x

Hadiz, V., and Robison, R. (2004). Reorganising power in Indonesia (1st Edition). London: Routledge. 303

Hadiz, V. R., and Robison, R. (2013). The political economy of oligarchy and the reorganization of power in Indonesia. Indonesia 96:35. doi: 10.5728/indonesia.96.0033

Heras, J. L. (2018). Politics of power: engaging with the structure-agency debate from a class-based perspective. Politics 38, 165–181. doi: 10.1177/0263395717692346

Holzer, M., and Kloby, K. (2005). Public performance measurement. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 54, 517–532. doi: 10.1108/17410400510622205

Hossain, M. (2022). Dispossession, environmental degradation and protest: Contested development in Bangladesh. Bonn: Universität Bonn.

Hossain, M. A. (2025). Roots and resilience: understanding the rise and persistence of authoritarianism in Bangladesh. Asian J. Comp. Polit. 22:6097. doi: 10.1177/20578911251366097

Huszár, Á., and Füzér, K. (2023). Improving living conditions, deepening class divisions: Hungarian class structure in international comparison, 2002–2018. East European Politics Soc Cult 37, 740–763. doi: 10.1177/08883254211060872

Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2012). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy 1st Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 333.

Jackman, D. (2021). Students, movements, and the threat to authoritarianism in Bangladesh. Contemp. South Asia 29, 181–197. doi: 10.1080/09584935.2020.1855113

Jamil, I., and Baniamin, H. M. (2021). How culture may nurture institutional trust: insights from Bangladesh and Nepal. Dev. Policy Rev. 39, 419–434. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12520

Kalsum, U., Nurlinah, N., and Irwan, A. L. (2024). The role of village-owned enterprises in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Wajo regency. Tamalanrea JGD 1, 29–35. doi: 10.69816/jgd.v1i1.34467

Kampen, J. K., De Walle, S., and Bouckaert, G. (2006). Assessing the relation between satisfaction with public service delivery and Trust in Government. The impact of the predisposition of citizens toward government on Evalutations of its performance. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 29, 387–404. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2006.11051881

Kim, P., and Im, T. (2019). Comparing government performance indicators: a fuzzy-set analysis. Korean J. Policy Stud. 34, 1–28. doi: 10.52372/kjps34201

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., and Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: how the rich are different from the poor. Psychol. Rev. 119, 546–572. doi: 10.1037/a0028756

Krejcie, R. V., and Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 30, 607–610. doi: 10.1177/001316447003000308

Le, K., and Nguyen, M. (2021). Education and political engagement. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 85:102441. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102441

Lee, A.-R. (1992). Values, government performance, and protest in South Korea. Asian Aff. Am. Rev. 18, 240–253. doi: 10.1080/00927678.1992.10553555

Lee, D., Chang, C. Y., and Hur, H. (2021). Political consequences of income inequality: assessing the relationship between perceived distributive fairness and political efficacy in Asia. Soc. Justice Res 34, 342–372. doi: 10.1007/s11211-021-00371-2

Lewis, D., and Hossain, A. (2022). Local political consolidation in Bangladesh: power, informality and patronage. Dev. Change 53, 356–375. doi: 10.1111/dech.12534

Lipset, S. M. (1981). Political man: the social bases of politics. 1st Edn. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. 440.

Ma, Z., and Cao, Y. (2023). Political participation in China: towards a new definition and typology. Soc. Sci. 12:531. doi: 10.3390/socsci12100531

Mahmud, R. (2021). What explains citizen trust in public institutions? Quality of government, performance, social capital, or demography. Asia Pac. J. Public Adm. 43, 106–124. doi: 10.1080/23276665.2021.1893197

Manstead, A. S. R. (2018). The psychology of social class: how socioeconomic status impacts thought, feelings, and behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 57, 267–291. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12251

Marien, S., Hooghe, M., and Quintelier, E. (2010). Inequalities in non-institutionalised forms of political participation: a multi-level analysis of 25 countries. Polit. Stud. 58, 187–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x

Megawati, S., Alfarizi, M., Syamsul, M. R., and Pradana, G. W. (2025). Behavioral model integration in studying money politics in the 2024 election: perspectives of young Indonesian voters. Public Adm. Policy 28, 202–214. doi: 10.1108/PAP-01-2024-0009

Miao, H., Wu, H.-C., and Huang, O. (2024). The influence of media use on different modes of political participation in China: political trust as the mediating factor. J. Asian Public Policy 17, 21–43. doi: 10.1080/17516234.2021.2022851

Misra, M. (2017). Is peasantry dead? Neoliberal reforms, the state and agrarian change in Bangladesh. J. Agrarian Change 17, 594–611. doi: 10.1111/joac.12172

Moore, B. (1969). Social origins of dictatorship and democracy: Lord and peasant in the making of the modern world. Tijdschrift Voor Filosofie 31, 793–796.

Moore, C. (2018). Internationalism in the global south: the evolution of a concept. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 53, 852–865. doi: 10.1177/0021909617744584

Muntaner, C., Lynch, J., and Oates, G. L. (2020). “The social class determinants of income inequality and social cohesion” in The political economy of social inequalities. eds. V. Navarro and L. Shi (New York, United States: Springer), 367–399.

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic deficit: Critical citizens revisited. Cambridge City: Cambridge University Press.

Nurlinah, H., Haryanto, P., and Chaeroel Ansar, M. (2024). Comparative study of social welfare programme effectiveness perception in peri-urban and rural in Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work Dev. 22, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/29949769.2024.2342794

Porumbescu, G. A. (2017). Does transparency improve citizens’ perceptions of government performance? Evidence from Seoul, South Korea. Admin. Soc. 49, 443–468. doi: 10.1177/0095399715593314

Pratschke, J. (2017). “Marxist class theory: competition, contingency and intermediate class positions” in Considering class: Theory, culture and the media in the 21st century. eds. D. O'Neill and M. Wayne (London: BRILL), 51–67.

Qayums, N. (2021). Beyond institutions: patronage and informal participation in Bangladesh’s hybrid regime. New Polit. Sci. 43, 67–85. doi: 10.1080/07393148.2020.1868246

Radin, B. A. (1998). Searching for government performance: the government performance and results act. PS Polit. Sci. Polit. 31, 553–555. doi: 10.2307/420615

Rodan, G. (2018). Participation without democracy: Containing conflict in Southeast Asia. New York: Cornell University Press.

Rusli, A. M., Syamsu, S., and Ansar, C. M. (2023). The effects of governance and multidimensional poverty at the grassroots level in Indonesia. Public Policy Admin. 23, 259–273. doi: 10.13165/VPA-24-23-2-10

Sairambay, Y. (2020). Reconceptualising political participation. Hum. Aff. 30, 120–127. doi: 10.1515/humaff-2020-0011

Sarker, M. M., and Islam, M. S. (2017). Social capital and political participation: a case study from rural Bangladesh. Eur. Rev. Appl. Sociol. 10, 54–64. doi: 10.1515/eras-2017-0009

Scott, J. C. (1985). Weapons of the weak: Everyday forms of peasant resistance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sørensen, E., and Torfing, J. (2021). Accountable government through collaborative governance? Adm. Sci. 11:127. doi: 10.3390/admsci11040127

Swart, L.-A., Day, S., Govender, R., and Seedat, M. (2020). Participation in (non)violent protests and associated psychosocial factors: sociodemographic status, civic engagement, and perceptions of government’s performance. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 50, 480–492. doi: 10.1177/0081246320912669

Syamsu, S., Ansar, M. C., and Nurlinah, N. (2025). Impact of class configuration on political participation: evidence from Gowa regency, Indonesia. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1544614. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1544614

Tarrow, S. (2012). Power in movement: Social movements and contentious politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van de Walle, S., and Bouckaert, G. (2003). Public service performance and Trust in Government: the problem of causality. Int. J. Public Adm. 26, 891–913. doi: 10.1081/PAD-120019352

Van Hamme, G. (2012). Social classes and political behaviours: directions for a geographical analysis. Geoforum 43, 772–783. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.01.003

Waeterloos, C., Walrave, M., and Ponnet, K. (2024). Social media as an exit strategy? The role of attitudes of discontent in explaining non-electoral political participation among Belgian young adults. Acta Politica 59, 364–393. doi: 10.1057/s41269-023-00297-4

Waheduzzaman, W., As-Saber, S., and Hamid, M. B. (2018). Elite capture of local participatory governance. Policy Polit. 46, 645–662. doi: 10.1332/030557318X15296526896531

Wang, C. (2016). Government performance, corruption, and political trust in East Asia. Soc. Sci. Q. 97, 211–231. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12223

Warburton, E., Muhtadi, B., Aspinall, E., and Fossati, D. (2021). When does class matter? Unequal representation in Indonesian legislatures. Third World Q. 42, 1252–1275. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2021.1882297

Wood, G. (1978). Class formation and ‘antediluvian’ Capital in Bangladesh *. IDS Bull. 9, 39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.1978.mp9003009.x

Yan, H., Shang, H., and Liu, H. (2023). The role and influencing factors of government performance evaluation: a test of Chinese public officials’ perceptions in Gaoming district. Chin. Public Adm. Rev. 14, 199–223. doi: 10.1177/15396754231195575

Yang, K., and Holzer, M. (2006). The performance-trust link: implications for performance measurement. Public Adm. Rev. 66, 114–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00560.x

Yoder, J. (2020). Does property ownership lead to participation in local politics? Evidence from property records and meeting minutes. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 1213–1229. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000556

Zakhour, S. (2020). The democratic legitimacy of public participation in planning: contrasting optimistic, critical, and agnostic understandings. Plan. Theory 19, 349–370. doi: 10.1177/1473095219897404

Zhan, W., and You, Z. (2024). Factors influencing villagers’ willingness to participate in grassroots governance: evidence from the Chinese social survey. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:1051. doi: 10.1057/s41599-024-03574-5

Zhang, J., Li, H., and Yang, K. (2022). A meta-analysis of the government performance—trust link: taking cultural and methodological factors into account. Public Adm. Rev. 82, 39–58. doi: 10.1111/puar.13439

Keywords: social class, government performance, public participation, moderation model, comparative study, Indonesia, Bangladesh

Citation: Nurlinah, Ansar MC, Megawati S and Chowdhury K (2025) Divided by class: Government perception and political participation in Indonesia and Bangladesh. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1673531. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1673531

Edited by:

Yusa Djuyandi, Padjadjaran University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Lukman Hakim, IPB University, IndonesiaPranab Kumar Panday, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh

Copyright © 2025 Nurlinah, Ansar, Megawati and Chowdhury. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muhammad Chaeroel Ansar, bWNoYWVyb2VsQHVuaGFzLmFjLmlk

Nurlinah

Nurlinah Muhammad Chaeroel Ansar

Muhammad Chaeroel Ansar Suci Megawati

Suci Megawati Kuntala Chowdhury

Kuntala Chowdhury