- DESP (Department Economics Society Politics), University of Urbino Carlo Bo, Urbino, Italy

Introduction: Women’s political representation in Italy has increased in recent decades, yet significant gender gaps persist across elected and appointed offices. The Municipality of Rome represents a distinctive case, as it is the only Italian city subdivided into directly elected Municipi. Differently, other large cities such as Milan, Turin, Bologna, and Naples are organised into zones, districts, or municipalità without elected bodies, limiting local political autonomy. This institutional uniqueness makes Rome an important site for investigating how gender, profession, and political alignment shape women’s political visibility and participation.

Methods: The study employs a mixed-method approach. It combines quantitative data (2016–2021) on elected and appointed offices, disaggregated by sex, with qualitative analysis of the professional backgrounds and political alignments of elected representatives in Rome. Furthermore, the agendas of Equal Opportunities Commissions across the Municipi are examined to assess how gender equality is operationalised at the local level.

Results: The findings reveal persistent inequalities. Women are more concentrated in education, social services, and intellectual professions, whereas men dominate entrepreneurial, managerial, and technical roles. Political alignment also influences gender balance: the left and the Five Star Movement (M5S) exhibit higher female participation, particularly from academic and social sectors, while the centre and right remain strongly tied to business and legal professions. Despite quota laws and equality regulations, women continue to be underrepresented in appointed roles and mayoral offices. The Equal Opportunities Commissions display heterogeneous agendas, combining advances in gender mainstreaming with the persistence of structural barriers.

Discussion: The Roman case illustrates the ambivalence of gender equality policies. While decentralised institutions and local commissions provide meaningful spaces for women’s participation, entrenched power structures still hinder substantive transformation. Compared with other Italian cities, Rome’s political decentralisation amplifies these dynamics, offering broader insights into both the limits and the potential of equality measures in local politics.

Introduction

Viewed through a gender perspective, local political participation is crucial, shaping how individuals access institutional representative roles. Over the past 30 years, formal political representation has gradually become more gender inclusive. Socio-political, cultural, and relational shifts, alongside gender-balancing legislation, have fostered a nuanced understanding of representation. Crucially, this long-term transformation stems not from political or institutional structures themselves, but from a broader cultural shift, onto which supranational directives—particularly European—have been subsequently overlaid and integrated into national legislation (Carbone et al., 2019).

While significant, this movement has largely resulted in procedural adjustments within institutional frameworks, effectively subordinating gender policies to a form of “State Feminism” (Krook and Mackay 2023) driven by strong external pressures (Donà, 2020). As a result, it has fallen short of producing a genuine cultural transformation that recognises gender equality as both a political value and a substantive objective. Equality has come to be implemented more as a procedural requirement or evaluation criterion, becoming part of administrative action increasingly oriented toward performance and consensus, without addressing the structural roots of gender inequality, whether in society, institutions, or political parties (Piccio, 2019).

Beginning in the early 1990s, the implementation of regulatory frameworks to enhance gender balance in representation has played a key role in broadening access to the public sphere. During the same period, the collapse of the bipolar world order (Cotta and Isernia, 1996) and, nationally, the “Mani Pulite” investigation of 19921, which exposed pervasive political corruption, led to a deep crisis in traditional political system and parties (Carbone and Farina, 2016). Consequently, parties sought new sources of legitimacy and electoral appeal. The increased participation of women enabled parties to reshape their public image and explore new avenues of legitimacy. The 1993 reform2, which introduced the direct election of mayors alongside the first gender quota provisions, marked a turning point, making local government more receptive to a gender-mixed political landscape within a broader European trend toward the democratisation of the public sphere, including in Mediterranean countries. Yet, traditional gender divides remain deeply entrenched in these contexts, and women’s political representation continues to be both numerically limited and more vulnerable to fluctuations in gender quota regulations (Dahlerup, 2022).

Moreover, gender disparity remains a structural feature. The extent to which Italy’s residual, familistic welfare state relies on women’s availability for reproductive rather than productive labour is significant (Del Re, 2012), effectively relegating their public participation to a secondary or optional status. Therefore, while gender equality policies do make a difference, it is precisely their presence or absence and implementation that determines women’s visibility and anchorage within institutional political arenas. Despite the consolidation of formal equality frameworks, a significant gap persists between formal and substantive equality. Although women’s political participation has increased, it continues to be limited by persistent role-based segregation. According to the United Nations (2015),3 women continue to constitute a minority among elected representatives across all countries with available data. This underrepresentation persists despite the implementation of gender quotas (Piscopo 2021) and reserved seats in 88 countries, pointing to the enduring presence of discriminatory practices within political parties and institutions at every level (Antonini and Vincenti, 2018). Literature has frequently highlighted this sphere as particularly receptive to female candidacies and appointments, partly due to the earlier introduction of gender quotas. This reinforces a centre–periphery dynamic in which the political core remains male-dominated, while the margins appear more accessible to women (Farina and Carbone, 2016)—yet it still falls short of true egalitarianism. As such, it represents a crucial site for analysing politics that, despite growing pluralism, continues to be shaped by male dominance (Barnett and Shalaby, 2024). By combining the formal rules of representation with the substantive modalities of access and appointment to positions of power, it becomes evident—more than 30 years after the initial reforms—that gender balance objectives remain far from achieved. The composition of municipal councils, executives, and mayoral offices continues to be gender-skewed. The relative accessibility of local institutions (Farina and Carbone, 2016) reflects a model of politics “close to home” (Ortbals et al., 2011), one in which women participate more frequently but remain constrained by care responsibilities, reproductive duties, and related limits on territorial mobility (Coffé and Bolzendahl, 2011). Unsurprisingly, the political centre remains a predominantly male domain.

However, contemporary political dynamics complicate this picture, as women’s institutional presence remains uneven. Increased representation within national and international institutions has not led to the emergence of alternative political agendas; rather, it often reflects processes of assimilation into dominant male-centred models. The co-optation of women as a minority presence frequently entails conformity to existing power (Towns and Krook 2023) structures, thereby reinforcing the continuity of prevailing agendas. Consequently, gender inequality must be understood not solely in quantitative terms, but also through the lens of enacted politics—that is, the capacity to disrupt entrenched continuities, instigate transformation, and redefine political agendas by incorporating diverse gendered perspectives and lived experiences.

Building on these considerations, this paper focuses on the Municipality of Rome, examining developments from 2013 to the present. The selected time frame is analytically motivated, aiming to assess the current configuration of gender representation through its territorial distribution. The study seeks to understand whether, and to what extent, the local political agenda has been informed, shaped, or transformed by gender equality policies and the relative pluralisation of political representation. A second objective is to investigate how political action at the local level addresses gender and equality-related issues.

The case of the Municipality of Rome, which is the focus of this study, is analytically significant not only because it is the national capital, but also because, as one of the country’s largest cities, its political developments often have national repercussions. The relevance of this case lies in Rome’s central geopolitical role, providing a critical vantage point for examining how gender dynamics have evolved within political structures that formally endorse equality, yet continue to marginalise women and sideline gender policies in practice. This analysis is organised into three sections: the first offers a descriptive account of gendered representation in mayoral offices across Italian municipalities between 1993 and 2025; the second examines elective offices resulting from the 2013, 2016, and 2023 local elections, including the composition of municipal executives and councils across Rome’s territorial subdivisions; and the third focuses on the political agenda, with particular attention to the extent to which it is informed by gender. This final section explores the content of political action and gender policies at the municipal level, especially through the work of the Equal Opportunities Commissions.

Issues of participation and representation

Politics, in all its forms of institutional representation, is persistently characterised by male dominance. This phenomenon, however, has only belatedly been acknowledged within the social sciences (Farina and Carbone, 2016), with empirical evidence observable in the modes of access to and exercise of representation across contexts. The historical and ongoing marginalisation of this issue, together with the limited scholarly attention it receives, tends to reinforce its perceived lesser significance. Nonetheless, the prevalence and impact of gender-based segregation remain defining features of political representation (Ryan and Haslam, 2005). This chapter aims to examine both the specificity and the extent of such gendered segregation within the institutional framework of the Municipality of Rome.

Rome provides a particularly compelling case study, given its central role in Italy’s political, social, and cultural landscape, as well as its historically vibrant female and feminist participation, which has contributed substantially to the history of women’s movements in Italy (Agosti and Tobagi, 2024). As home to one of the most prominent feminist movements in Europe and the wider Western context, Italy presents a distinctive case due to the delayed institutional adoption of the movement’s legacy. The transition from activist demands to institutional action (Rossi Doria, 2007) still leaves ample room for reflection on the genuine recognition of rights, autonomy, and equality (Pezzini and Lorenzetti, 2019).

The analysis of political representation in the Municipality of Rome pursues a dual objective: to map participation by sex and to examine whether, and what kind of, gender agenda has been established within municipal governing bodies. Simple counts of elected and appointed women cannot serve as the sole metric for analysing changes and barriers to achieving genuine representational parity. Rather, it is necessary to understand how women’s actions—or actions taken on behalf of women—are embodied, how they interact with, influence, and coexist alongside historically entrenched male dominance, how collective agency is exercised, and how opportunities for transformation emerge.

This latter dimension is the most complex to explore and the most critical in terms of methodological approach, as it implicates entrenched power relations, mechanisms of selection and co-optation grounded in these relations, and requires distancing from a causal assumption linking women’s presence directly to substantive change. It also necessitates avoiding the imposition of a mandate upon women to represent the entire female constituency, thereby burdening them with the challenge of transformation (Farina and Carbone, 2015). Treating women separately from men risks replicating existing inequalities and obscuring the complex relational dynamics through which both men and women navigate party-imposed rules historically structured around male norms.

Contemporary accounts portray male political leadership as asserting itself across public spaces—from local to international arenas—within a comfortably male-dominated sphere, resistant to change unless it is assimilated into prevailing masculine paradigms, or “patrix,” as one might playfully term it. Literature continues to reveal party co-optation mechanisms in which male rule prevails, and norms endorse a framework of equality that risks normalising gender roles, draining original activist impetus, and reducing gender equality to the mere assimilation of women into a male-dominated political world. Yet recent phenomena challenge even optimistic assumptions about the permanence of such normalisation.

A landmark shift is epitomised by the “sex of terror” Faludi (1991, 2008) identifies as emerging immediately after the 2001 attacks on key U. S. institutional sites—including the Pentagon and the Twin Towers of New York. The resurgence of the Alpha Male, described as central to a new public discourse emerging from institutional politics, is now transnationally observable and consistently aimed at restoring masculine privilege in power relations. Several studies document a pronounced authoritarian turn hostile to women (Beinart, 2019), accelerated during the Covid-19 pandemic, a period in which masculine power was strengthened in an exclusionary, punitive, and even regressive manner regarding women’s acquired rights—even in democracies previously more receptive to inclusivity (Farina, 2021). There is growing reflection on a de-democratisation process, questioning women’s place in society (Weeks et al., 2024), with negative consequences for social justice (Farina, 2024; Kuhar and Paternotte, 2017; Verloo and Paternotte, 2018; Krizsán and Roggeband, 2021; Lombardo et al., 2021; Graff and Korolczuk, 2021) and efforts to achieve gender equality. As Fraser (2013, 2023) asserts, the struggle for equality is complex, encompassing tensions in the redistribution of material and symbolic resources as well as visibility defined by status recognition and political representation.

Power in relations, as Scott (1986) discusses, is embedded in sexed arrangements and serves the objective of reproduction. Within this complexity, discerning both change and the persistence of male-dominated monopolies—through mechanisms such as “blue quotas” (Saraceno, 2008), the opening of public space, and the widespread absence of gender equity—remains challenging.

Focusing on political representation, the growing presence of women across institutions and party groups constitutes a significant new dynamic that cannot be overlooked. The expansion of public space, facilitated by existing rules, marks a discontinuity in political practices. Recently, right-wing parties in Italy have benefited most from this expansion, electing an increasing number of women, while left-wing parties have exhibited a cultural and political retreat (Carbone and Farina, 2019), evident both numerically and in political programme content, which has increasingly distanced itself from historically grounded women’s issues.

Presence and visibility: women in mayoral office

Amid a paradoxical national trend, the city of Rome stands out as a notable exception among Italy’s major urban centres, having elected and inaugurated a woman as mayor. Notably, this occurred under the banner of a party-movement—the Five Star Movement4—which, as previously noted, elected the highest number of female parliamentarians in the 2018 general elections. The institutional reform introduced by Law No. 81/1993, which established the direct election of mayors, undeniably expanded the formal access of women to the political-institutional arena. Nonetheless, it is the presence of gender equality measures that exerts a more substantive influence in fostering gender-balanced representation. Empirical evidence indicates that the presence—or conversely, the absence—of legal instruments aimed at gender rebalancing directly impacts the numerical presence of women in local executive office (Carbone and Farina, 2016).

These dynamics underscore the structural fragility of gender parity provisions within the Italian institutional and political context, where normative frameworks often fail to translate into consistent and widespread institutional practices. The disjunction between formal equality and the persistence of gendered social norms represents a key barrier to substantive representational equity. Despite the increasing pluralisation and complexity of contemporary Italian society, political leadership (Celis et al., 2023) at the local level continues to be characterised by a male-dominated singularity.

Statistical data reinforce this view: since the 1993, with the introduction of direct mayoral elections, the number of women elected as mayors remains significantly low, with an even greater underrepresentation in provincial and regional capitals (Associazione Nazionale Comuni Italiani (ANCI), 2025). The first woman to hold the mayoralty of a major city was elected in Naples5. In 2016, two further landmark elections occurred: Virginia Raggi in Rome and Chiara Appendino in Turin, both affiliated with the Five Star Movement.

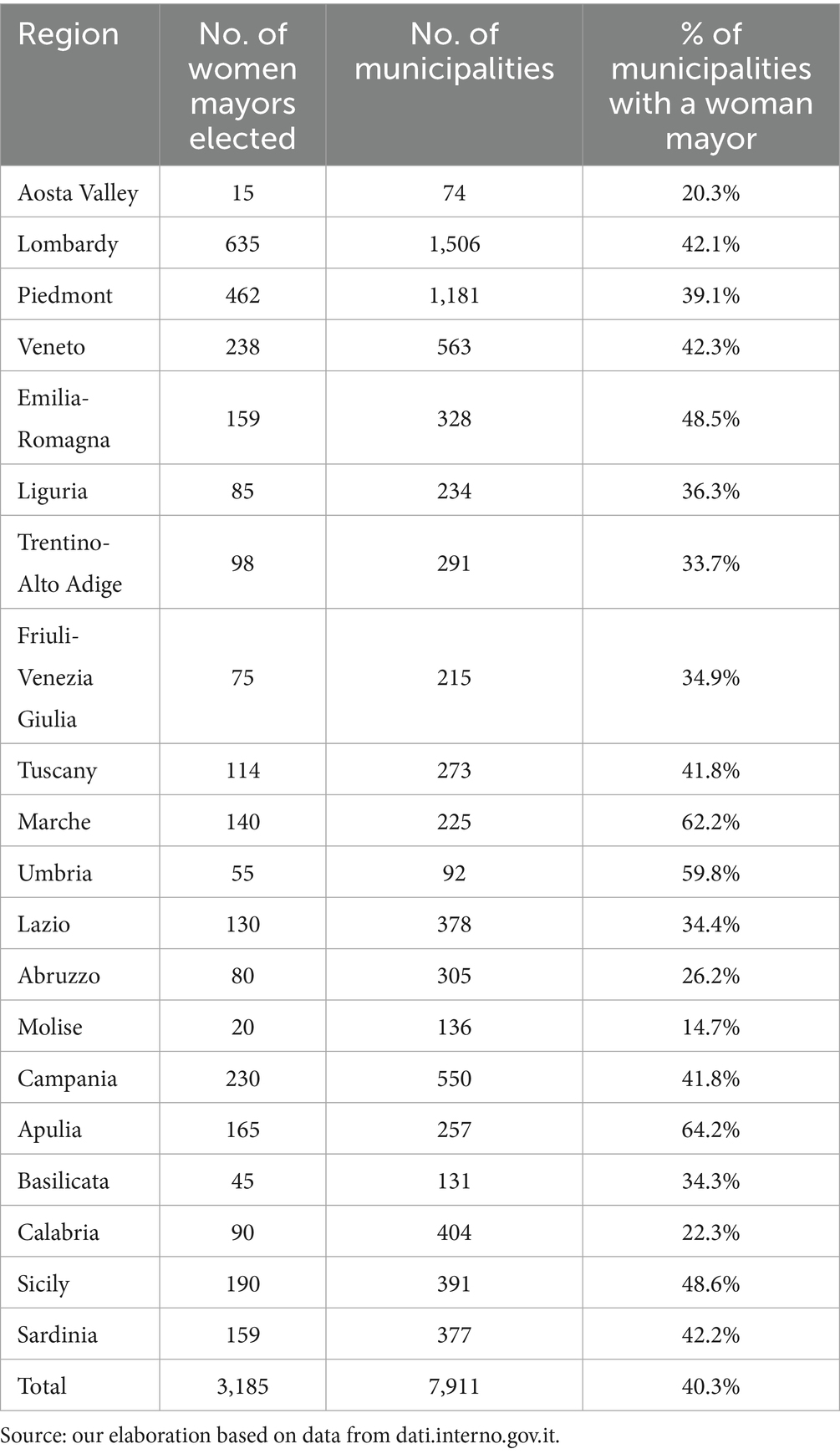

A regional analysis reveals further asymmetries (Table 1). In absolute terms, the highest numbers of women mayors have been elected in Lombardy and, subsequently, in Piedmont. However, when these figures are adjusted for the total number of municipalities in each region, the proportional representation of women mayors declines markedly. In contrast, Apulia and Marche exhibit the highest relative rates, with 64 and 62% of municipalities, respectively, having elected a woman mayor at least once. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Molise shows the lowest proportion, while the Aosta Valley, despite having the fewest municipalities overall, records the lowest absolute number of women mayors.

Table 1. Women mayors elected by region (1993–2025) (Number and percentage of municipalities with a woman mayor).

Table 2 presents data on women mayors currently in office, disaggregated by region and grouped by macro-geographical area, revealing marked territorial disparities. While Lombardy has the highest absolute number of female mayors, Tuscany (33.0%) and Emilia-Romagna (30.5%) lead proportionally. In contrast, Molise (7.4%) and Calabria (12.4%) report the lowest percentages. The Aosta Valley, with 11 women mayors out of 74 municipalities, has a proportion of 14.9%. Although Central Italy exhibits the highest relative proportion of women mayors among its municipalities, it paradoxically has a lower absolute number compared with the North and the South.

When comparing macro-regions, Central Italy has the highest proportion of municipalities governed by women (22.2%), followed by the North (16.8%), the Aosta Valley (14.9%), and the South (12.7%). These patterns reflect regional civic traditions influencing women’s participation in politics and the labour market. Tuscany stands out with the highest share of municipalities led by a woman mayor, followed by Emilia-Romagna and Veneto, which also exceed the national average. By contrast, Molise and Calabria confirm the persistence of a gender gap in Southern Italy. Previous studies have shown that local representation is closely linked to the redistribution of both material and symbolic resources that facilitate women’s participation (Carbone and Farina, 2016).

Municipal size is another key factor. In towns with fewer than 15,000 inhabitants—where gender quotas do not apply to candidate lists—female underrepresentation is partly attributable to the absence of regulatory pressure. In larger municipalities, where quotas are enforced (no gender may account for more than 60% of any candidate list), women’s representation is somewhat higher. Nonetheless, structural barriers persist even in these contexts, particularly in access to top positions such as mayor, which remain dominated by male-led networks (Enloe, 2014). Quotas tend to produce more balanced outcomes at central levels of government, whereas local candidacies remain shaped by informal dynamics and are more exposed to inequalities in campaign funding and party support (Verge and Claveria, 2022; Krook, 2020).

The 2025 data confirm this imbalance: the percentage of female mayors does not exceed 33% in any region and remains below 25% in most cases. This challenges the notion that “politics close to home” is inherently more accessible to women, demonstrating instead that executive positions—even at the municipal level—remain predominantly male. The equalising effect of current measures appears limited, indicating the persistence of a cultural impasse obstructing the development of a more equitable political landscape. The greater the symbolic stakes and political competition, the more women and other minorities are disadvantaged, particularly in large urban centres. Existing legal provisions, while necessary, remain insufficient on their own to redress these imbalances.

In conclusion, the analysis of current female mayoral incumbency reveals a fragmented and inconsistent pattern. Legal reforms have thus far failed to produce a lasting equalising effect on women’s access to local executive office. The election of women to mayoralties in Naples, Turin, and Rome remains exceptional within a broader structural trend. As of 2025, women account for only 17% of serving mayors, compared to 83% men—1,380 women out of 6,531 municipalities. Mayoral leadership continues to be overwhelmingly male.

Regional patterns further highlight persistent disparities. Northern Italy exhibits the highest proportion of municipalities governed by women (17.5%), while the Centre and South record 15.9 and 12.7%, respectively. The Aosta Valley, with 14.9% of municipalities led by women, illustrates that small size alone does not ensure greater female representation. Even regions with strong civic traditions, such as Tuscany (33%) and Emilia-Romagna (30.5%), remain exceptions rather than the norm. These figures confirm that structural and cultural barriers continue to shape women’s participation, and that legal provisions alone are insufficient to achieve equitable representation across the country.

Women’s institutional and political representation remains constrained by a range of contextual and systemic factors. Their presence is still hindered by structural barriers and the inertia of a political system largely resistant to gender transformation.

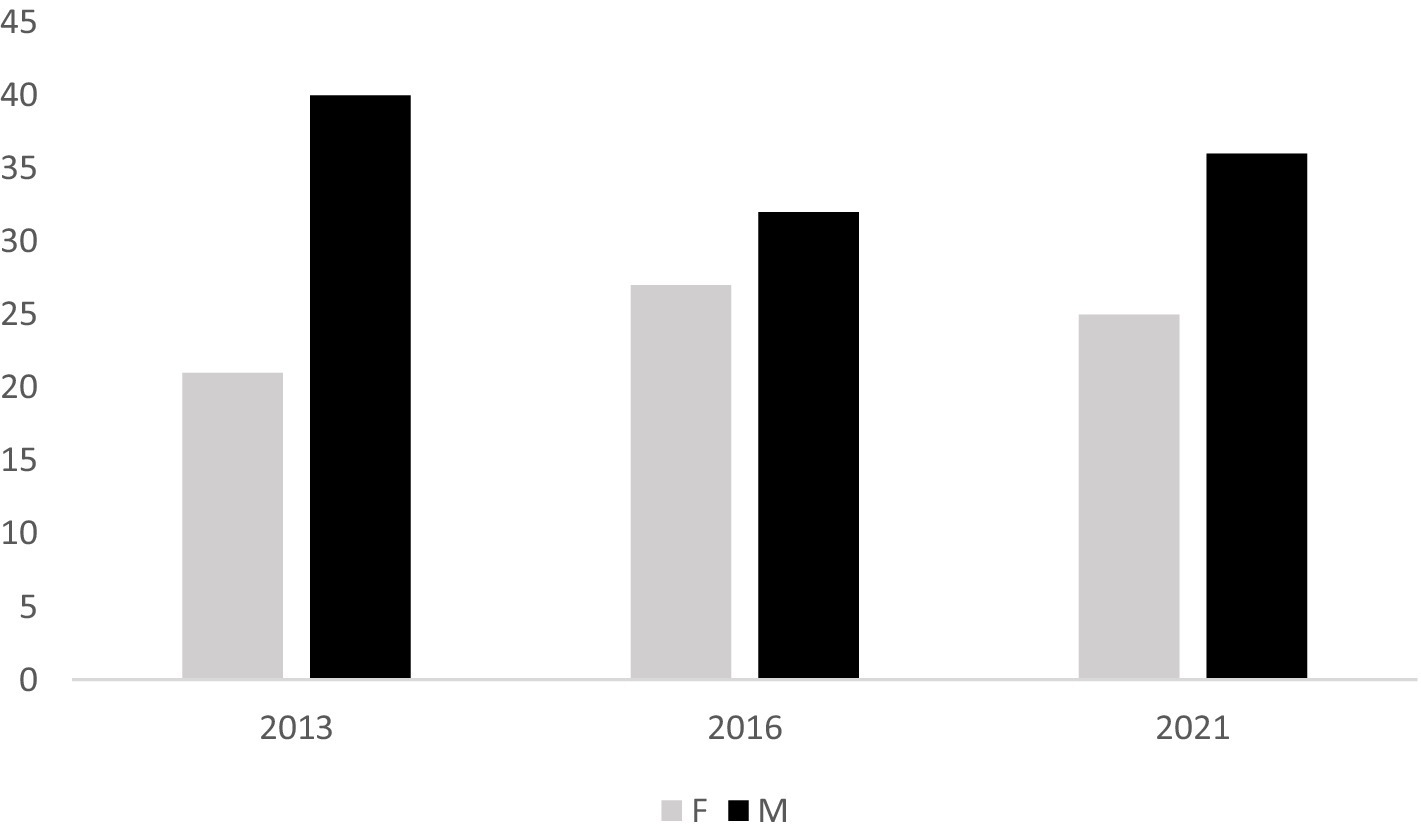

Women in the municipality of Rome

Having analysed the national and regional context and the distribution of women’s representation across elected and appointed offices, the focus now shifts to the case study that constitutes the core of this research. This section analyses the presence of elected and appointed women across various roles within the municipal administration of Rome, focusing on the last three electoral cycles—2013, 2016, and 20216. As illustrated in Figure 1, a persistent gender gap exists throughout the entire period, widening particularly between 2016 and 2021. The observed trend does not indicate a progressive movement towards gender balance. Notably, the most recent cycle saw a decline in the number of women, both elected and appointed, while the number of men increased.

Figure 1. Elected and appointed officials by sex, 2016–2021. Source: our elaboration from dati.interno.gov.it.

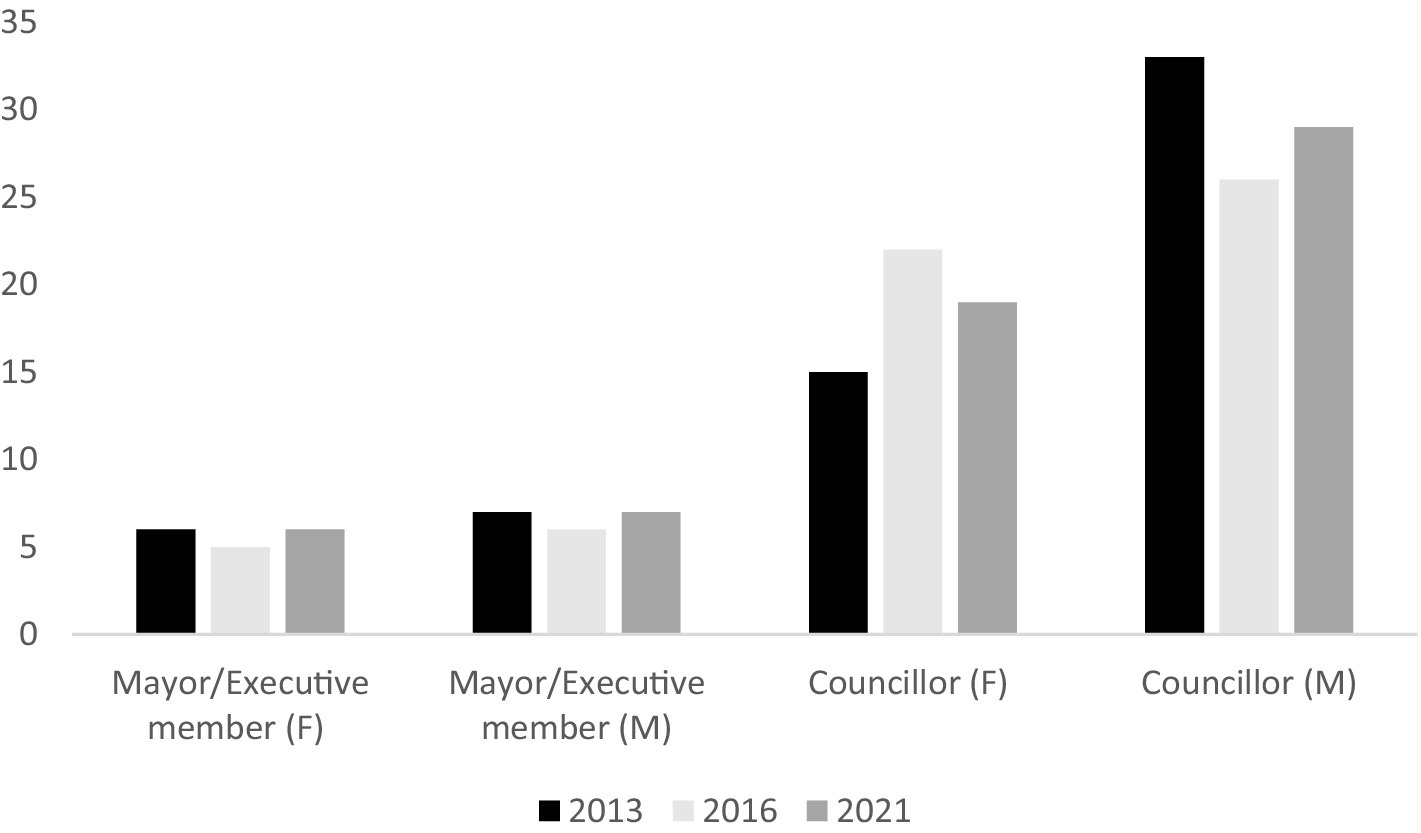

Disaggregating the data by role and sex (Figure 2), a relatively balanced distribution appears, especially among elected councillors. Nevertheless, this is also the area where the most pronounced gender gap persists across all three electoral cycles. Women remain underrepresented in appointed roles and mayoral positions, and the elective office still reflects the most significant inequality. These results run counter to the expected redistributive effect of gender quotas and equality regulations or at least its administration. The enduring gap highlights a departure from intended objectives: despite progress in normative frameworks and increased female participation, entrenched power structures continue to hinder full transformation. This may reflect a form of “boomerang effect,” whereby formal commitments to equality paradoxically stabilise the status quo missing the goal of gender parity.

Figure 2. Role by sex and year of election/appointment. Source: our elaboration based on data from dati.interno.gov.it.

Analysing the age distribution of political office holders (Table 3), the gender gap is narrower among those under 40. It widens in the middle-age categories, where the intersection of professional demands and caregiving responsibilities disproportionately affects women’s political trajectories. A generational shift in values and behaviour may be underway. Among those over 60, both the total number of representatives and the gender gap diminish.

Although this is a case study analysis, the data appears consistent with broader trends observed nationwide. Regarding the level of education (Table 4) of men and women currently in office, it is particularly noteworthy that the proportion of university graduates is high for both sexes, though significantly higher among women. Nearly all women officeholders hold a university degree (68 out of 73), with only 5 holding an upper secondary diploma. In contrast, 32 of the 108 men hold only a diploma, while 76 are university graduates. This indicates that men are more often represented among those who did not pursue higher education, whereas women demonstrate higher levels of educational attainment despite holding the same positions. This, in turn, suggests an indirect measure of structural imbalance linked to selection mechanisms: to compete with men for the same roles, women appear to be required to offer more valuable credentials.

It can also be hypothesised that men tend to access political engagement and appointments more frequently and at an earlier stage than women7. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to complete their university education, obtaining a degree before entering political roles. This hypothesis is partially supported by data on occupational status but better evident in the analysis of the published curricula.

Women are predominantly concentrated in intellectual and social professions (Table 5), particularly law and the judiciary (13 women out of 24), journalism and writing (6 out of 10), and university teaching and education/social work (6 out of 12 in each case). Certain sectors, such as architecture, are exclusively female.

Men prevail in entrepreneurial, managerial, and technical professions, including political and union leadership positions. The categories less represented, such as military personnel, pensioners, students, interns, music, and stage work are grouped under “Other.”

Some sectors show gender balance, notably university teaching and education/social work. Overall, the pattern confirms that women tend to enter local politics primarily from intellectual and social professions, while men are over-represented in managerial, entrepreneurial, and technical fields. This distribution reflects the gendered segmentation of the labour market and demonstrates how structural inequalities are reproduced in the composition of the political élite.

The professional backgrounds in civic lists, although numerically less significant, and within the Five Star Movement (M5S), do not markedly differ. Broadly speaking, while no major structural contrasts are found across political alignments, some specific patterns emerge. On one side, the left and M5S show a higher presence of professionals working in education, intellectual production, and social services. On the other, the centre and right feature more frequent profiles such as entrepreneurs, managers, and legal professionals.

Women are predominantly concentrated in professions traditionally considered female-dominated, including law and the judiciary, university teaching and research, journalism and writing, and teaching, education, and social work. Certain sectors, such as architecture, are entirely female, whereas technical professions are more evenly distributed or slightly male-dominated. Men are more prevalent in entrepreneurial, managerial, and technical professions, as well as in administrative and union leadership roles.

When examined by political coalition (Table 6), the left (SX) shows a slight female advantage in offices held, reflecting a stronger female presence in progressive political spaces. In contrast, the centre-left (CSX) and the right-leaning coalitions—centre (CX), right (DX), and centre-right (CDX)—display a clear male predominance, particularly in entrepreneurial, managerial, and technical sectors. The Five Star Movement (M5S) exhibits near gender parity, with women and men almost equally represented across education, research, and administrative roles. Civic lists and non-reported cases form a small but balanced group, encompassing professions that do not fit the major categories, such as interns or music and stage professionals.

This integrated analysis highlights the intersection of gender, professional background, and political affiliation in shaping representation within the municipal council. Female representation is concentrated in intellectual and social fields, while male representation dominates business, management, and technical sectors. The data indicate that, despite some variation across coalitions, gender inequalities remain a persistent feature of political representation in Rome.

Focusing on the coalitions (Table 7), the left (SX) is the only coalition where women slightly outnumber men (+2), reflecting a stronger female presence in progressive political spaces. In contrast, centre-left (CSX) and other right-leaning coalitions—centre (CX), right (DX), and centre-right (CDX)—show a clear male predominance, with the largest imbalance observed in the centre-left (−17).

The Five Star Movement (M5S) is close to gender parity (−1), highlighting a more balanced approach in candidate selection, whereas civic lists and non-reported cases (LC/NR) are perfectly balanced (0 difference).

These data suggest that gender representation is not evenly distributed across political coalitions: progressive and activist-oriented spaces tend to have higher female representation, while centrist and conservative coalitions are dominated by men. Table 6 underscores the enduring intersection between gender and political alignment, showing that women are still underrepresented in most political groupings, despite some variation.

The current municipal administration and the equality challenge

At present, assessor roles on the executive board are evenly distributed between men and women. The position of Deputy Mayor is held by a woman, while the mayoralty has once again been assigned to a man. The Social Policies portfolio is entrusted to a woman affiliated with a civic list that supported the elected mayor, whereas the Finance portfolio—including responsibility for overseeing the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)—is held by a woman appointed externally, outside the traditional party structures.

The greater gender balance observed in appointed positions is largely attributable to regulatory provisions and an increasing institutional emphasis on equality. In the last two administrations, gender equality has been formalised as a key commitment throughout the institutional framework, as established in the 2013 municipal statute. This statute explicitly mandates the promotion of equal opportunities, gender balance in appointments, and parity in the allocation of managerial roles8.

Currently, the number of male and female assessors is evenly balanced. However, an examination of individual career trajectories reveals that all appointed men have previously held political office, whereas this applies only to the majority—not all—of the women (Table 8).

The data show that, in appointed positions, gender parity regulations are most effectively implemented. This is not the case, however, for the elective office of councillor. Indeed, the current municipal council of Rome comprises a majority of men, with 27 male councillors compared to 21 female councillors. The disparity is even more pronounced when examining career trajectories. An analysis of the curricula of those holding assessor roles shows that, although appointments are numerically balanced, all men appointed have prior political experience, whereas two of the female assessors have no previous political background. Similarly, prior political experience is more prevalent among male councillors, with 19 out of 27 having such backgrounds, compared to only 8 out of 21 women (Table 9).

These patterns reveal the persistent influence of homosocial networks, which increasingly favour men due to their closer proximity to established entry points into political representation at all levels. The data suggest that, despite formal parity in appointments, underlying structural and relational factors continue to advantage men, highlighting that numerical equality alone does not translate into equitable access to political power. In this context, women remain more likely to face barriers related to career progression and the accumulation of political capital, indicating that substantive gender equality requires not only regulatory measures but also transformative changes in institutional practices and informal networks.

Although limited to a single case, these findings are revealing. They arise in a context where proximity to the local level—particularly municipal politics—might be expected to favour gender plurality. Previous researches (Carbone and Farina, 2016; Carbone, 2016) have shown that local institutions are generally more responsive to women’s aspirations for political engagement and career advancement.

Nevertheless, significant disparities persist even at the local level. While these are not always apparent in terms of numerical representation, they become evident when examining the distribution of institutional roles. The highest-ranking positions remain predominantly male.

An analysis of Rome’s territorial administration—the Municipi—confirms this trend. Currently, 11 out of 15 Presidents of Municipi are men, with only 4 women occupying this role. Similarly, 9 Vice Presidents are men, compared to just 6 women (Table 10). Notably, all Presidents of Municipal Councils are men, indicating a consistent narrowing of female presence at the top levels of local governance.

A comparable compression is observed among Municipal Councillors: men number 229, while women total 131. By contrast, the distribution of assessors is more balanced, with 48 men and 41 women in office. This more equitable allocation reflects recent efforts to promote gender-balanced appointments, underpinned by both political commitment and formal regulatory frameworks9.

Nevertheless, it remains evident that top positions continue to be dominated by men, with little sign of disruption or discontinuity. The resulting geography of political representation in Rome reflects a tension between incremental change and deeply entrenched continuity, ultimately sustaining a gendered and unequal status quo. This disaggregated analysis of the Capitoline administration highlights the persistence of structural barriers and symbolic exclusion, underscoring that formal rules alone are insufficient to achieve substantive gender equality. The findings point to the need for transformative interventions that address not only numerical representation but also the informal networks, institutional cultures, and career trajectories that continue to privilege men over women in positions of political authority.

A final point concerns the division between political and administrative roles within the Capital. Within the mayor’s office and its supporting structures (Table 11), only 1 out of 6 key roles is occupied by a woman. Across the broader administrative apparatus, just 3 of 10 key support positions are held by women. The heads of strategic offices—including the Central Procurement Department and the Legal, Assembly, and Human Resources offices—remain predominantly male. Only the Public Library system and the Department for Participated Entities are led by women.

Overall, the landscape of Rome’s political-administrative system continues to exhibit the hallmarks of male dominance. This underscores the limited impact of rebalancing regulations and highlights the persistent structural inertia of a system that has yet to fully integrate gender equality as a foundational political and institutional value.

The agenda of and for elected women

Subsequent to the examination of the composition and distribution of political representation across both elected and appointed roles within the municipal and administrative apparatus of Rome, it becomes essential to interrogate the nexus between formal representation and its substantive realisation. The central analytical concern is whether the presence of gender diversity among elected officials has been translated into effective and meaningful political action over the course of the current legislative term.

As previously noted, in 2013 the City of Rome promulgated a revised municipal statute incorporating provisions explicitly aimed at fostering equal opportunities and dismantling structural barriers to women’s participation in public and political life. Article 5 of this statute enjoins gender balance in appointments across public institutions, publicly owned enterprises, and associated bodies. A principal instrument for operationalising this commitment has been the establishment of Equal Opportunities Commissions (EOCs) within each of the city’s 15 Municipi.

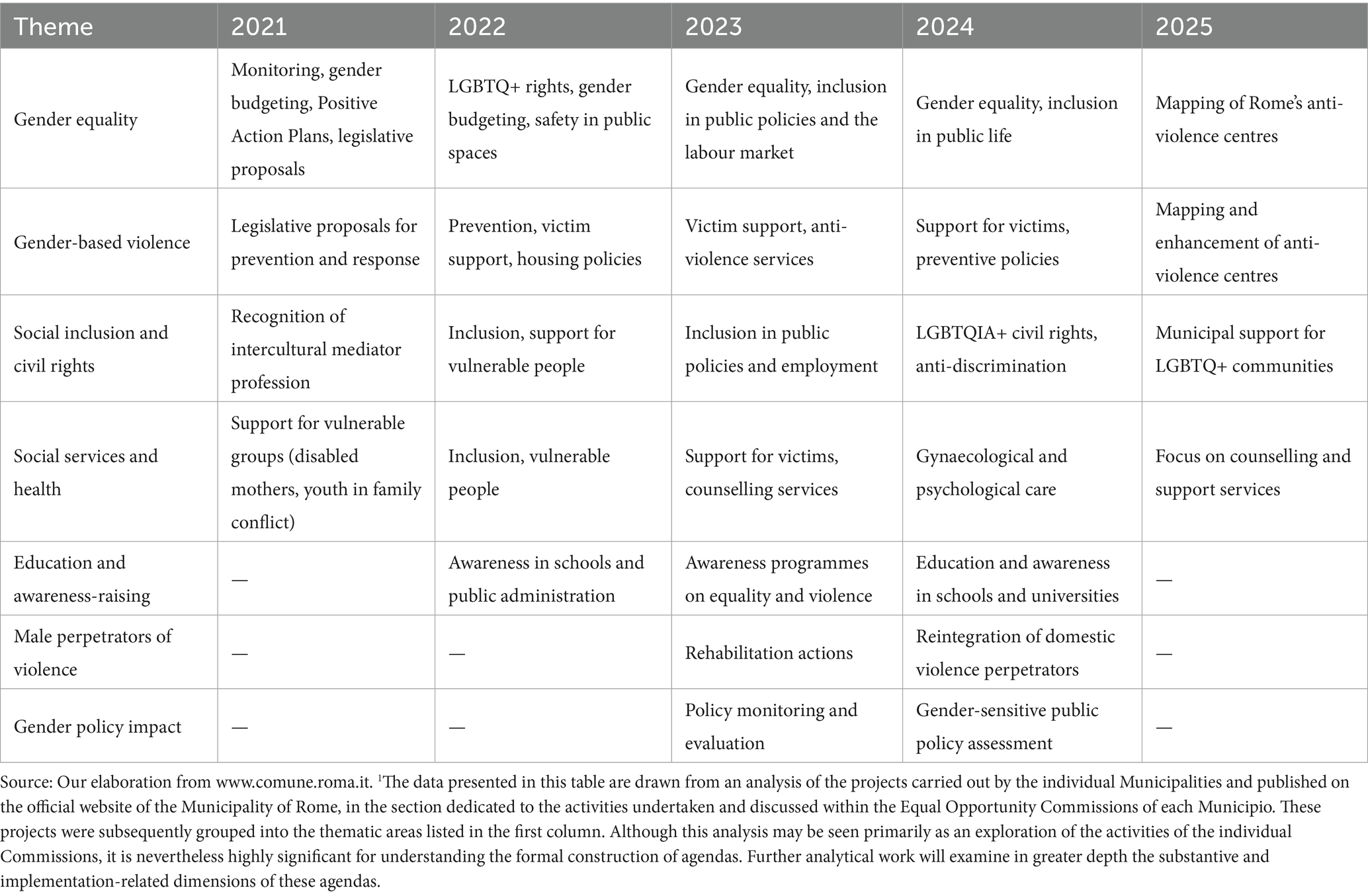

While the regulatory framework is unequivocally delineated, significant questions persist regarding the efficacy of its implementation. To this end, the minutes of the Equal Opportunities Commission of the central municipal administration were systematically analysed for the period 2021–2025, corresponding to the current electoral cycle. It is notable that Commission activity reached its zenith in the early years—likely reflecting responses to the socio-institutional disruptions engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic—before stabilising or exhibiting a modest attenuation in subsequent years.

The Commission’s resolutions over this period may be categorised both temporally and thematically (Table 12). The first and most consistently addressed theme pertains to gender equality, encompassing initiatives such as gender-responsive budgeting, legislative proposals, and the promotion of positive action plans. Over time, this thematic domain has expanded to incorporate broader dimensions of inclusion, particularly with reference to public policy and equitable access to the labour market. In 2025, a systemic approach was further institutionalised through the comprehensive mapping of anti-violence centres, thereby fostering more integrated, coordinated, and empirically measurable interventions.

Table 12. Analysis of the agendas of the equal opportunities commission of the city of Rome (2021–2025).1

The second thematic focus concerns gender-based violence, initially addressed through legislative proposals and subsequently through the development of support services and institutional mechanisms tailored to local exigencies.

The third thematic domain encompasses social inclusion and civil rights, with particular attention to vulnerable populations, intercultural mediation, and the protection of LGBTQIA+ rights, thus reflecting an expansion of the equality agenda toward intersectionality and pluralistic recognition.

The fourth theme relates to social and health services, particularly those directed toward victims of violence. From 2024 onwards, the focus has broadened to include continuity of care and the quality of psychological and gynaecological services, extending protection and support to women and other vulnerable groups.

Education and awareness-raising initiatives, particularly within schools and higher education institutions, constitute the fifth principal domain, aiming to cultivate a culture grounded in civil rights, gender equality, and violence prevention. In 2024, a related dimension emerged concerning the rehabilitation of male perpetrators of violence, indicative of a conceptual shift from an exclusive emphasis on victim support to a more holistic approach incorporating offender re-education.

Finally, in 2024, the Commission introduced a novel thematic area: the gender impact assessment of public policies, underscoring the imperative of systematically evaluating policy outcomes to inform evidence-based planning and the strategic orientation of future interventions.

As this analysis elucidates, the deployment of gender as a foundation for a politically informed agenda necessitates engagement with a heterogeneous spectrum of issues, which do not invariably converge into a fully coherent or systematic framework. While gender considerations are indeed present, the agenda manifests the greatest continuity and institutional consolidation in two principal domains: gender-based violence and LGBTQIA+ rights. Within these spheres, the Department for Equal Opportunities evidences a sustained and unequivocal institutional commitment.

An examination of initiatives catalogued under the rubric of gender equality, as documented on the official website of the City of Rome, substantiates this observation. The preponderance of activities is directed toward addressing gender-based violence, followed by interventions focused on LGBTQIA+ rights. Other measures, pursued less systematically, encompass broader equal opportunity concerns, including equitable access to employment, support for victims of mafia-related crimes, relational distress among adolescents, dissemination of information on recovery fund opportunities, and the operational continuity of anti-violence centres during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A further salient development in the formal consolidation of the local gender agenda is the City of Rome’s engagement with the Stati Generali delle Donne network and its participation in the Città delle Donne initiative, first inaugurated in Matera in 2019. These undertakings exemplify the institutionalisation of gender-sensitive policymaking and underscore the ongoing effort to embed considerations of equality and inclusion within the strategic orientation of municipal governance10.

This affiliation was followed the next year by the approval and adoption of the project’s Guidelines11, which declared Rome the first European capital to be recognised as a “City of Women.” The document outlined a commitment to implementing cross-cutting actions across various spheres of life—employment, education, public safety, transport, the fight against gender-based violence, quality of life, and more—acknowledging the gender-unequal structure of society and its detrimental economic and social consequences12.

The commitment thus entailed the adoption of territorial measures aimed at reducing the gender gap in the social, occupational, educational, and safety domains, as well as in transport, with a view to Counteracting and Preventing Gender-Based Violence and improving the quality of life for all citizens. The endorsement of this initiative was formalised through a unanimous and cross-party vote by all political forces represented in the municipal administration.

This process of advancing gender equality also includes the City of Rome’s pursuit of Gender Certification. This initiative began in 2022 by seizing the opportunity offered by a specific measure within the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), and culminated in its approval in January 2025. The strategic objectives are set out in the 2025–2027 Strategic Plan, entitled Gender Policy Document of Roma Capitale. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. The plan aims to promote gender equality by involving not only the internal structure of the municipal administration but also all external stakeholders engaged in various forms of interaction with it13.

Equal opportunities commissions

The role of the Equal Opportunities Commission and its local branches thus continues to constitute the cornerstone of territorial action within what has been defined in this study as a gender-oriented local agenda. This section examines the agendas of the Equal Opportunities Commissions across the Municipi that constitute the administrative area of the Municipality of Rome. Rome’s division into Municipi represents a distinctive feature in the Italian context, combining administrative decentralisation with significant political and decision-making autonomy, as each Municipio directly elects its President and Municipal Board. This institutional arrangement is particularly relevant for the present analysis, as it enables a nuanced exploration of how the Commissions’ activities are implemented and differentiated across the municipal territories.

As shown in Table 13, Equal Opportunities Commissions are present in all fifteen Municipi. A mapping of these commissions reveals noteworthy patterns in their composition. Despite some territorial variation, the female presence within these bodies is overwhelmingly dominant—a finding that is unsurprising given the original mandate and mission of such institutions.

However, it is timely to reflect critically on this characteristic, which continues to assign women the primary responsibility for advancing gender equality within a mandate that is largely intra-gender rather than inter-gender. This structural configuration risks overlooking the relational dimension—the material and symbolic space in which gender disparities are produced and reproduced. Equal Opportunities Commissions remain a predominantly female domain in both function and composition. Nonetheless, male representation accounts for approximately one third of total members, a proportion that exceeds male representation in the traditionally male-dominated institutional-political sphere.

Quantitatively, across all municipal commissions, there are 107 members in total: 75 women and 32 men. Considering territorial variation, the First Municipio’s commission is entirely female, while the Fourth and Tenth are almost entirely female, each with a single male member. Three Municipi demonstrate near gender parity, and only in the Fourteenth does male membership exceed female membership.

It is also noteworthy that the web pages dedicated to each Municipio systematically present institutional roles, including those within the Equal Opportunities Commissions, in the masculine grammatical form. This tendency is reinforced by the fact that all but one Commission President is male, one of whom is actively engaged in LGBTQIA* rights advocacy. Among the vice-presidents, 12 are women, and 10 occupy the specific post of Deputy Vice-President across the 15 Municipi. Accordingly, women hold the majority of leadership roles, whereas men are more frequently represented among general commission members (23 men versus 40 women).

This observation raises a persistent question: why do women constitute the majority within Equal Opportunities Commissions—and only in this institutional setting? Beyond the historical fact that the demand for equality originated from and was primarily advanced by women, the institutionalisation of this mandate has rendered these commissions a unique space within the political-institutional landscape, both in terms of gender composition and the issues addressed. Simultaneously, this process has formalised a gendered division of political labour and, by extension, a hierarchy in which the domain of equal opportunities remains largely a female sphere—significant in terms of influence on equality matters, yet perceived as less prestigious politically. Consequently, these roles are less competitive and less sought after, precisely because they are more accessible to women and implicitly delegated to them.

This aspect—while often assumed or overlooked within the inertia of formalised structures—proves to be highly significant when examining its correlations and effects on the political agenda, on policies enacted at the local level, and, more broadly, on the concept of substantive representation, wherein political engagement is guided by a transformative commitment to gender equality.

Municipal agendas

We now turn to the orientation of activities undertaken by the Equal Opportunities Commissions within the individual Municipi. To better capture the complexity of local agendas, we analyzed the minutes of Commission meetings from the current legislative term, covering the period from 2021 to the present. Overall, the number of minutes available on the webpages of the City of Rome’s official site dedicated to the Municipi is limited and varies considerably between Municipi. In two of the fifteen Municipi, no minutes of the respective Commissions are available.

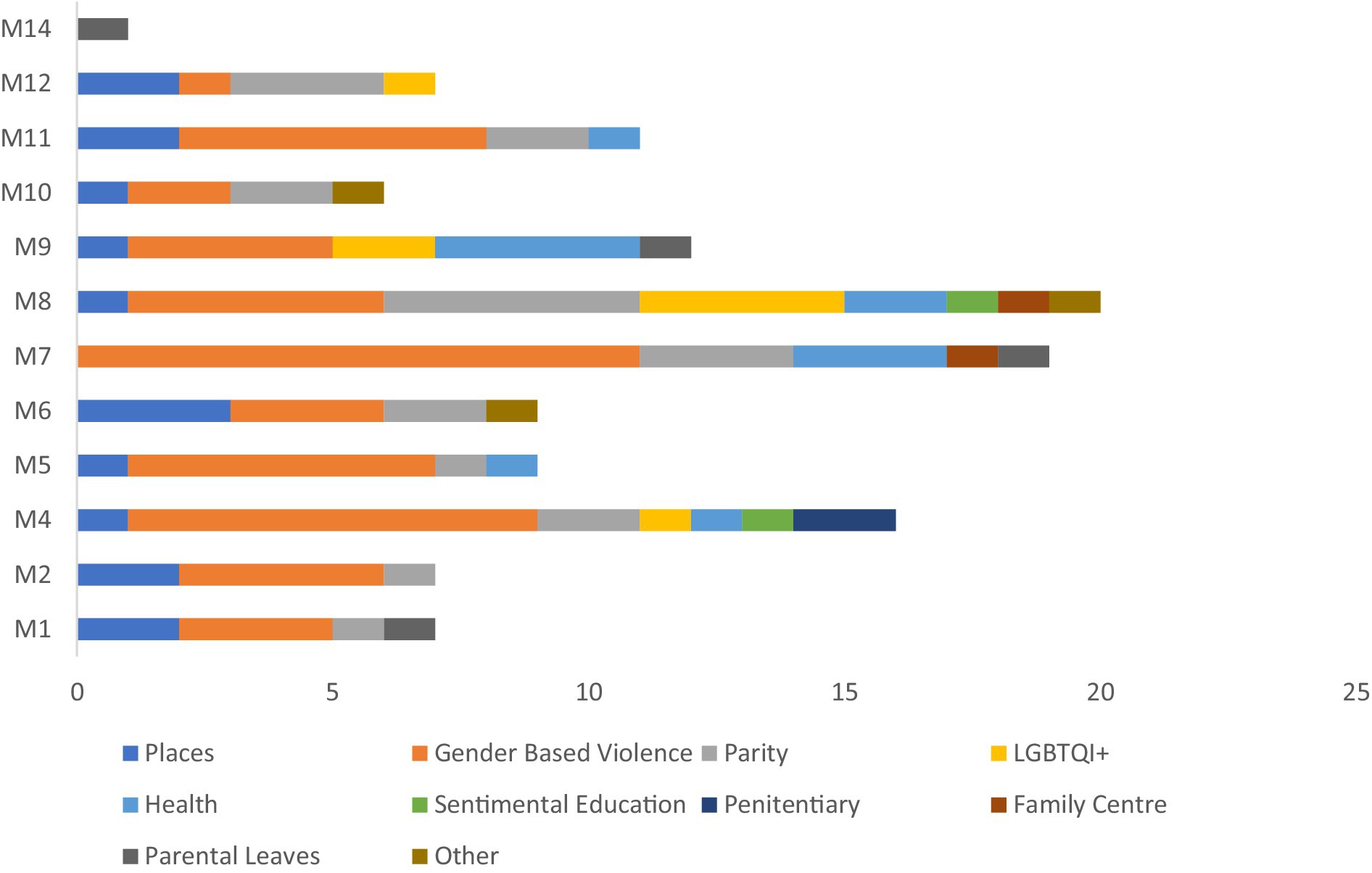

The first salient finding (Figure 3) concerns the level of activity, measurable through the available minutes and the meetings they document. In terms of content, however, there is less variation. Across all Municipi, the dominant issue is gender-based violence, encompassing both prevention and response measures. This theme occupies a central place in the Commissions’ work, including discussions of prevention projects, awareness campaigns, support measures, and the strengthening of local services. The centrality of this topic undoubtedly reflects the urban context and its associated challenges.

Figure 3. Areas of intervention of equal opportunities commissions by Municipio. Source: Our elaboration from www.comune.roma.it

The second most prominent area of concern pertains to public spaces and their various interpretations: the safety of public spaces, the creation of areas reserved for women (such as designated parking), and symbolic territorial interventions, including the naming of streets after women to counterbalance a male-dominated toponymy.

The theme of equality in its strict sense follows in prominence but is addressed with varying emphasis across the Commissions. One notable initiative in this domain is a gender mapping project, developed collaboratively by multiple Municipi, aimed at providing a comprehensive overview of implemented measures. More frequently, however, such actions are isolated, including initiatives such as the introduction of gender budgeting or public discussions on female empowerment and entrepreneurship.

The theme of women’s health is addressed only by a subset of Municipi, which have promoted initiatives to raise awareness of “invisible” illnesses affecting women—conditions that are under-recognised and under-communicated—and to engage local health and social care services. Only a few Municipi address issues relating to the rights of LGBTQIA+ individuals and families.

Less frequently considered are topics such as parental leave, particularly for fathers, and support for separated fathers.

Overall, the mandate of the Commissions appears to be interpreted in diverse ways, both in terms of the intensity of activity and the range of issues addressed. The strong female majority within these bodies does not translate into a uniform local agenda, nor into a consistent conceptualisation of gender equality, as suggested by the very name of the Commission. One notable convergence occurs around the themes of gender-based violence and spatial safety. Whether this reflects a shared understanding of gender relations within the local socio-urban context remains a significant question, implicating both the characteristics of the context and prevailing approaches to gender relations. Interventions thus focus not only on structural imbalances but also on the victimisation of women in the city.

This observation becomes even more pertinent when considered alongside another key finding: gender equality appears only intermittently and does not constitute an overarching framework guiding the actions of the municipal Commissions. Even within individual Commissions, the agenda is neither systematic nor grounded in a comprehensive vision. Topics relating to women’s participation in the public sphere—whether political or occupational—are notably absent.

In conclusion, the emerging picture is that of a fragmented territorial “agenda,” wherein the work of the Equal Opportunities Commissions is concentrated primarily on women as victims of violence or those at risk. The available data do not suggest the existence of a gender agenda in the strict sense, but rather a targeted intervention in response to specific critical issues. Political action at the local level appears embedded within the particularities of specific contexts, yet remains largely disconnected from any broader, guiding vision.

Conclusion

Within the inherent limitations of a single case study, the analyses presented herein allow for several salient reflections on women’s political representation, particularly in relation to the discrepancies and transformations characterising the post-party political landscape and its composition. Gender emerges as a crucial analytical lens through which to examine the broader challenges arising from the expansion of the public sphere in participatory terms, alongside a persistent gendered revisionism that constrains progress towards substantive and equitable representation. The case of the Municipality of Rome offers valuable insights, meriting further investigation, including through comparative analyses across cities, regions, and national contexts14.

The realm of political representation, alongside participation in the labour market, continues to constitute one of the most critical domains in relation to the achievement of gender equality. This objective—central to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015)—remains undermined by enduring disparities, with institutional political representation ranking among the weakest indicators globally (Paxton et al., 2020), and particularly so within the Italian context (WEF, 2024)15.

The first key issue pertains to women’s presence and entrenchment within power structures—structures which, to date, have only minimally facilitated transformative change (EIGE, 2024). Gender quotas implemented over time have demonstrated greater efficacy in corporate governance than in political institutions, where only Spain and Slovenia presently surpass the legally mandated thresholds for parliamentary representation.16

Within the Italian setting, pressing concerns manifest across both central and local political arenas. Despite a social landscape marked by persistent gender inequalities across all spheres of life—as once again confirmed by the latest BES report (ISTAT, 2024)—what stands out is the mirrored gap in women’s underrepresentation in both leadership positions and local institutions. This is particularly striking given that women’s presence is currently more substantial in the national parliament.17

Although numerical representation has increased, the ability to exert substantive influence within the political-institutional system remains limited.18 This phenomenon can be attributed, on the one hand, to the persistent gap between electoral success and actual appointment to positions of substantive power, and, on the other, to the tendency to normalise women’s presence in the public political sphere as a procedural formality rather than as a genuine mandate to transform and redefine power relations. The “paradoxical change” observed following the 2018 general elections (Farina and Carbone, 2016) further underscored the growing disconnect between women’s political presence and the advancement of a gender-oriented agenda. This was evident both in political programmes and in the allocation of female candidates, who were disproportionately positioned in parties and electoral lists detached from gender claims and the feminist movements that had originally introduced such claims into the public sphere.

Far from constituting merely an “unfinished revolution” (Walby, 1997), this development represents a long-term constraint on women’s political agency, undermined more substantively than formally. In this respect, the case of the City of Rome is particularly illustrative. Although elected women have consistently exceeded representational thresholds, their marginalisation within actual decision-making structures persists. Despite the introduction of gender-equal regulations and formal rules, patterns of segregative partitioning remain pervasive. The effectiveness of such measures ultimately depends on the political will to enforce them and the degree of alignment among actors in supporting their implementation.

Within this context, gender equality occupies an ambiguous and often contradictory position, increasingly subsumed under broader identity-based claims that risk diluting its transformative potential and weakening the impact of political action in fragmented and uncertain settings. Women’s agendas, moreover, remain largely confined to initiatives specifically targeting women, predominantly focused on issues such as violence and personal safety, with little expansion into broader structural reforms.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

FF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding was received for the publication from Department of Economics Society Politics, University of Urbino Carlo Bo.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Translation review; Bibliography check.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The 1992 ‘Mani Pulite’ (Clean Hands) investigation was a wide-ranging judicial inquiry into systemic political corruption in Italy. Led by Milanese magistrates, it revealed extensive bribery networks involving politicians, entrepreneurs, and public officials, ultimately contributing to the collapse of the so-called ‘First Republic’ and triggering a profound reconfiguration of the Italian political system (Della Porta and Vannucci, 1999).

2. ^In the 1993 Italy introduced a major reform of local government by establishing the direct election of mayors (Law No. 81/1993). This shift from indirect to direct election was aimed at enhancing political accountability, governance stability, and citizen participation at the municipal level (Bobbio, 1999).

3. ^https://localgov.unwomen.org/.

4. ^The Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle, M5S) is a populist political party in Italy, founded in 2009 by comedian Beppe Grillo and web strategist Gianroberto Casaleggio. It emerged as a protest movement against traditional political elites, advocating for direct democracy, environmental sustainability, and anti-corruption measures. The M5S has played a significant role in reshaping Italy’s political landscape, particularly through its unconventional approach to politics and emphasis on digital participation (Bordignon and Ceccarini, 2013).

5. ^This refers to Rosa Russo Iervolino, who held office from 2001 to 2011.

6. ^This period coincides with the introduction of legislative measures on gender quotas. Law 215/2012, which established the obligation of gender quotas, aimed to promote greater gender equality within local institutions by seeking to reduce the gap between men and women in politics. The subsequent Law 56/2014 (the Delrio Law), which reformed local governance, reinforced this principle by extending its application to the councils of metropolitan cities.

7. ^This hypothesis is further substantiated by an examination of the published curricula vitae of the elected officials.

8. ^The current Statute of Rome Capital was approved by the Capitoline Assembly with Resolution No. 8 on 7 March 2013. It was published in the Official Gazette No. 75 on 29 March 2013 and came into force on 30 March 2013.

9. ^It should be noted that, within the geographical mapping of political representation, women remain in the minority across all roles considered within the Municipalities’ political bodies. It is also necessary to reflect on the availability and quality of the data, including its accuracy and transparency. In this case, the data were obtained from individual Municipal webpages, which provide lists of officeholders by position. The absence of data itself serves as an indicator of both the accessibility of information and its overall quality.

10. ^Resolution No. 253 of the Capitoline Assembly, dated 16 November 2022, which approved the “Positive Action Plan” for the three-year period 2019–2021, available at https://portalecug.gov.it.

11. ^https://www.statigeneralidelledonne.com/chi_siamo_stati_generali:delle_donne/le-citta-delle-donne/.

12. ^https://static.cittametropolitanaroma.it/uploads/P3-24-Le-citta-delle-Donne.pdf.

13. ^https://www.comune.roma.it/web-resources/cms/documents/Documento_politica_di_genere.pdf.

14. ^It should be emphasised here that the weakness of the available data, both in terms of accessibility and transparency, represents a significant limitation to knowledge, which becomes even more problematic in the context of a comparative analytical framework.

15. ^The most recent 2024 Gender Gap Report not only highlights a decline for Italy, which has fallen eight positions compared to the previous year, but also places the country near the bottom of the European gender equality rankings, ranking only above Hungary and the Czech Republic—both countries where gender issues are strongly shaped by revisionist denial of equality.

16. ^https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/publications/gender-balance-politics-november-2023.

17. ^It is noteworthy that lower levels of representation tend to be associated with reduced women’s confidence in institutions and in their anticipated future prospects.

18. ^Openpolis refers to a strength index that is lower for women than their numerical presence, reflecting the disparity of power measured by the positions assigned to and held by women and men.

References

Agosti, P., and Tobagi, B. (2024). Covando un mondo nuovo. Viaggio tra le donne degli anni Settanta. Turin: Einaudi.

Antonini, E., and Vincenti, A. (2018). “SeXto and the City: dal sessismo ordinario al hate speech” in La partecipazione politica femminile tra rappresentanza formale e sostanziale. ed. D. Carbone (Cham: Franco Angeli), 127–148.

Associazione Nazionale Comuni Italiani (ANCI) (2025). Donne in Comune. Rome: Ufficio Banche Dati e Ricerche.

Barnett, C., and Shalaby, M. (2024). All politics is local: studying women’s representation in local politics in authoritarian regimes. Polit. Gender 20, 235–240. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X22000502

Bobbio, L. (1999). Le arene deliberative. Cosa succede quando i cittadini decidono. Firenze: Le Monnier.

Bordignon, F., and Ceccarini, L. (2013). Five star movement: organisation, communication and ideology. Contemp. Ital. Polit. 5, 1–16.

Carbone, D. (2016). Donne in politica: Percorsi e ambizioni delle elette nei comuni italiani. Rass. Ital. Sociol. 57, 369–389.

Carbone, D., and Farina, F. (2016). Le donne nel ceto politico locale in Italia: un’analisi territoriale. Meridian 87, 245–270.

Carbone, D., and Farina, F. (2019). La partecipazione politica femminile tra rappresentanza formale e sostanziale. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Celis, K., Childs, S., and Kantola, J. (2023). Resisting women’s political leadership: The politics of backlash. London: Routledge.

Coffé, H., and Bolzendahl, C. (2011). Gender gaps in political participation across sub-Saharan African nations. Soc. Indic. Res. 102, 245–264. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9676-6

Cotta, M., and Isernia, P. (1996). The Italian political system: Between crisis and transformation. Oxford: Westview Press.

Del Re, A. (2012). Questioni di genere: alcune riflessioni sul rapporto produzione/riproduzione nella definizione del comune. About Gender 1, 151–170.

Della Porta, D., and Vannucci, A. (1999). Corrupt exchanges: Actors, resources, and mechanisms of political corruption. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Donà, A. (2020). “Le politiche di genere e il femminismo di Stato: tra pressioni esterne e resistenze domestiche” in Le politiche pubbliche in Italia. eds. G. Capano and A. Natalini (New York, NY: Il Mulino), 211–224.

Enloe, C. H. (2014). Bananas, beaches and bases: Making feminist sense of international politics. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Faludi, S. (1991). Backlash: The undeclared war against American women. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group.

Faludi, S. (2008). Il sesso del terrore. Il nuovo maschilismo americano (E. Nifosi, Trad.). Milano: Isbn Edizioni.

Farina, F. (2021). Siamo in guerra. L’anno che per poterci curare non andammo da nessuna parte. Milano: Mimesis Edizioni.

Farina, F. (2024). Come tutto è diventato guerra. Uno sguardo longitudinale dal femminile al militare e ritorno. Milano: Mimesis Edizioni.

Farina, F., and Carbone, D. (2015). Pari o dispari? Le pari opportunità secondo le consigliere comunali in Italia. Polis 29, 221–249.

Fraser, N. (2013). Fortunes of feminism: From state-managed capitalism to neoliberal crisis. London: Verso.

Fraser, N. (2023). Capitalismo cannibale: Come il sistema sta divorando la democrazia, il nostro senso di comunità e il pianeta. Laterza: Gius. Laterza & Figli Spa.

Graff, A., and Korolczuk, E. (2021). Anti-gender politics in the populist moment. London: Routledge.

Krizsán, A., and Roggeband, C. (2021). Politicizing gender and democracy in the context of the Istanbul convention. New York, NY: Palgrave Pivot.

Krook, M. L., and Mackay, F. (2023). Gender, politics, and institutions: Towards a feminist institutionalism. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kuhar, R., and Paternotte, D. (Eds.) (2017). Anti-gender campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing against equality. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Lombardo, E., Kantola, J., and Rubio-Marin, R. (2021). De-democratization and opposition to gender equality politics in Europe. Soc. Polit. 28, 521–531. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxab030

Ortbals, C. D., Rincker, M., and Montoya, C. (2011). Politics close to home: the impact of meso-level institutions on women's political representation. Politics Gender 7, 481–509. doi: 10.1093/publius/pjr029

Paxton, P., Hughes, M. M., and Barnes, T. D. (2020). Women, politics, and power: A global perspective. 4th Edn. New York, NY: CQ Press.

Pezzini, B., and Lorenzetti, A. (2019). 70 anni dopo tra uguaglianza e differenza: Una riflessione sull'impatto del genere nella Costituzione e nel costituzionalismo. Torino: Giappichelli.

Piccio, D. R. (2019). ““Prendi i soldi e…” Un’analisi sull’efficacia degli incentivi economici per la promozione della rappresentanza di genere” in La partecipazione politica femminile tra rappresentanza formale e sostanziale. eds. D. Carbone and F. Farina (Milano: FrancoAngeli), 85–106.

Piscopo, J. M. (2021). The impact of gender quotas on political representation: Evidence from Latin America and Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rossi Doria, A. (2007). Dare forma al silenzio. Scritti di storia politica delle donne. London: Viella.

Ryan, M. K., and Haslam, S. A. (2005). The glass cliff: evidence that women are over-represented in precarious leadership positions. Br. J. Manage. 16, 81–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2005.00433.x

Saraceno, C. (2008). Tra uguaglianza e differenza: Il dilemma irrisolto della cittadinanza delle donne. Modena: Fondazione Ermanno Gorrieri per gli studi sociali.

Scott, J. W. (1986). Gender: a useful category of historical analysis. Am. Hist. Rev. 91, 1053–1075. doi: 10.1086/ahr/91.5.1053

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. London: United Nations.

Verge, T., and Claveria, S. (2022). Power-seeking, networking and competition: why women do not rise in political parties. Party Polit. 28, 897–927. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2097442

Verloo, M., and Paternotte, D. (2018). The feminist project under threat in Europe. Polit. Governance 6, 1–5. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i3.1736

Weeks, A. C., Caravantes, P., Espírito Santo, A., Lombardo, E., Stratigaki, M., and Gul, S. (2024). When is gender on party agendas? Manifestos and (de)democratisation in Greece, Portugal, and Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 22, 1–33. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2024.2412746

Keywords: gender gap, political representation, local government, equal opportunity, Rome

Citation: Farina F (2025) What agenda of and for women? Gender, politics, and institutional transformation in Rome. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1674925. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1674925

Edited by:

Dario Quattromani, Università Link Campus, ItalyReviewed by:

Domenico Carbone, University of Eastern Piedmont, ItalyMaria Grazia Galantino, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Farina. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fatima Farina, ZmF0aW1hLmZhcmluYUB1bml1cmIuaXQ=

Fatima Farina

Fatima Farina