- 1Rural Sociology Study Program, Faculty of Human Ecology, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

- 2Division of Rural Sociology and Community Development, Department of Communication Science and Community Development, Faculty of Human Ecology, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

- 3Department of Economics, Faculty of Economics and Management, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

Rural youth movements in Indonesia have long been marginalized within national narratives, despite their deep historical roots in local struggles that shaped collective consciousness and community resilience. This study reinterprets the history of rural youth activism in Cigombong, Bogor Regency, Indonesia, as a form of resistance rooted in collective memory, community values, and symbolic practices in response to the expansion of corporate capitalism in rural areas. Utilizing an ethnographic and historical-tracing approach combined with quantitative data from 151 rural youth activists, the research explores the transformation of youth agency from the colonial era to the digital age and examines how local history is reactivated as both a symbolic and political resource. The findings reveal that local patriotism, manifested through collective action, cultural expression, and net-activism, has generated new forms of community-based resistance. By integrating the theory of social fields and the framework of collective memory, this article underscores the importance of reinterpreting local history as a strategy to strengthen the resilience and autonomy of rural youth in shaping their own futures, contributing to sociological discourse on rural youth activism, lived space, and grassroots nationalism in the platform era.

1 Introduction

Studies on youth movements in rural Indonesia have long overlooked the significance of local historical contexts as the foundation for collective consciousness and the resilience of younger generations. These local histories often carry traces of resistance equally important as the national narratives, which tend to be dominated by urban elites and metropolitan perspectives. In villages such as those in the Cigombong region, Bogor Regency, histories of resistance are not merely preserved in formal documentation but are also embedded in collective memory, symbolic sites, and oral narratives passed down through generations.

Cigombong plays a pivotal role in the historical landscape of resistance in Bogor and its surroundings. Interviews with local history teachers reveal that the region was home to early nationalist organizations such as the Sarekat Dagang Islam (SDI) and Medan Priyayi, as well as sites of physical revolutionary struggle against colonial forces, including the Maseng Incident and the activities of guerrilla groups like Laskar Hitam. These narratives, however, are often marginalized within the state’s official historiography, reducing local history to mere anecdotes rather than recognizing it as a reservoir of social consciousness.

Contemporary rural youth are caught in a dual bind: on the one hand, they live under the structural pressure of expanding capitalism that commodifies and constrains rural life (Wertheim, 1974; Li, 2014); on the other hand, they have been estranged from the historical struggles of their own communities. This disjuncture fosters a void in identity and weakens the foundations of collective grassroots movements (Bourdieu, 1984; Tsing, 2005). The phenomenon is exacerbated by development paradigms that ignore the cultural and political dimensions of village life, resulting in the depoliticization of youth in rural areas (Scott, 1985; Kumar, 2025). Comparative studies have shown similar trends elsewhere, where young people’s confidence in democracy is eroding, especially in countries undergoing political transition or social upheaval (Baizhumakyzy et al., 2025; Lorente and Jiménez-Bravo, 2025).

Nevertheless, new forms of youth activism have begun to emerge, particularly around issues of ecological justice, land rights, and alternative economies. These movements are less anchored in grand ideologies and more embedded in micro-resistances—everyday lived experiences, cultural expressions, and digital engagements (Marimón Llorca and Roche Cárcel, 2025; Kumar, 2025; Ponton and Raimo, 2024). Within this landscape, digital platforms no longer function merely as communication tools but operate as socio-technical ecosystems, facilitating identity production, symbolic resistance, and political participation through forms of net-activism (Surrenti and Di Felice, 2025). These are networked and trans-organic practices that intertwine human actors with data, environments, and algorithmic agents in emerging info-ecological terrains.

This is evident not only in Southeast Asia but also in other global contexts. Movements rooted in ecofeminism and land rights in India (Kumar, 2025), or digital literacy and virtual public spheres among Gen Z populations in Indonesia (Venus et al., 2025), reflect this new mode of civic expression. Globally, youth activism is increasingly shifting from traditional organization-based mobilizations to hybrid repertoires of action that include visual campaigns, murals, short videos, and localized community interventions as new modes of political mediation (Pan, 2024; Venus et al., 2025). In Cigombong, such activism is manifest in youth-led resistance to land dispossession, exclusive economic zoning, and the ecological degradation of village spaces—mobilizations that symbolically and materially reaffirm local patriotic narratives.

This article seeks to revive and reconstruct the patriotic history of rural youth in Cigombong as a strategic and symbolic resource. By employing ethnographic methods and oral history approaches, the research traces the trajectories of rural youth resistance from colonial times to the present. Using the theoretical lens of social fields (Bourdieu, 1986), complemented by the framework of collective memory (Halbwachs, 1992; Connerton, 1989), this study demonstrates that rural youth are not merely passive subjects of development but can emerge as active political agents by reclaiming their historical narratives.

In doing so, the article contributes to broader sociological debates on youth movements and rural resistance while offering a renewed theoretical perspective on the importance of revitalizing local history as a compass for contemporary activism. Cigombong stands as a living testament to how patriotic histories can serve as bridges between older generations and present-day aspirations for transformation, an enduring form of resistance grounded not in noise, but in memory, place, and collective consciousness.

2 Research methodology

2.1 Research approach and design

This study employs a socio-historical qualitative approach with a critical-narrative design. This approach was selected to understand the dynamics of history and the transformation of youth activism in Cigombong not merely as historical facts, but as social constructions embedded in collective memory, local narratives, and cultural practices. As emphasized by Tsing (2005) and Connerton (1989), history must be read through the tensions between the local and the global, between memory and institution, and between dominant narratives and marginalized experiences.

The narrative design was chosen to document the lived experiences of youth and villagers as symbolic articulations of history, resistance, and patriotism. The study also incorporates elements of historical ethnography, wherein the researcher not only gathers stories but actively engages in social interactions with subjects who possess either firsthand historical experiences or inherited narratives of significant events.

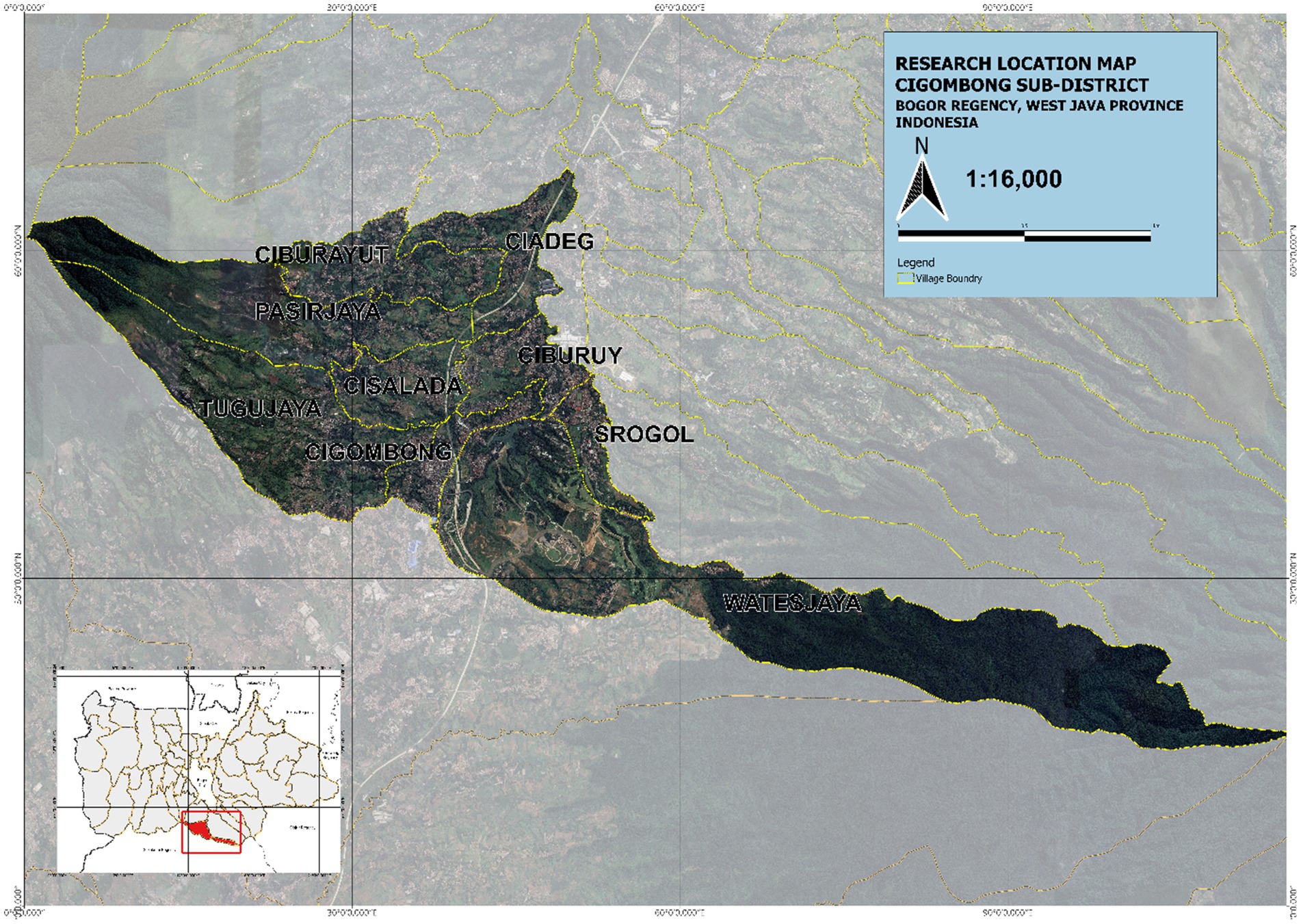

2.2 Research site and subjects

The research was conducted in Cigombong Subdistrict, Bogor Regency, West Java Province, Indonesia. This area was selected due to its historically significant role in the anti-colonial resistance and its relevance in the post-independence struggles against capitalist expansion, as well as its position as a key site in the emergence of contemporary environmental and cultural youth activism.

The primary research subjects are rural youth involved in various forms of local activism (environmental, cultural, digital, symbolic, economic); historical and educational figures; and community elders knowledgeable about local socio-historical dynamics. Participants were selected through purposive sampling, based on their capacity to represent historical experiences and generational perspectives on rural youth struggles.

2.3 Sources and data collection techniques

Data sources and collection techniques included:

In-depth interviews, conducted to explore key informants’ reflections, life histories, and narratives concerning the history of Cigombong’s youth from the colonial era to the present. Informants provided extensive accounts of generational experiences and activist trajectories.

Participant observation, employed over six months through reflective field journals and direct engagement in cultural, social, and digital spaces of youth activity. Daily field notes recorded youth interactions in community forums, cultural events, digital dialogues, symbolic expressions, and collective responses to economic-political conditions.

Document analysis, this research examined Dutch colonial archives (1880–1938) accessed through Leiden University Libraries, Nationaalarchief.nl, and Delpher.nl. These archives include newspapers, academic articles, books, and photographs related to Cigombong (historically “Tjigombong”). The documents were used to: (1) trace Cigombong’s historical trajectory as a plantation site and locus of peasant resistance; (2) understand colonial narratives around youth mobilization and forced labor (koeli kontrak); (3) identify the agrarian and exploitative roots of contemporary youth consciousness; and (4) treat these documents as discourse material in critical discourse analysis, interpreted in dialogue with present-day digital activism and symbolic resistance.

Survey, a supplementary survey was administered to 151 rural youth activists in Cigombong to identify participation patterns, issue perception, and preferred activism strategies. This quantitative element served to enhance the narrative findings and strengthen data validity through a simple quantitative approach. The survey was distributed purposively through local community networks and digital platforms.

Prior to each interview, verbal and/or written informed consent was obtained from participants. Participants were assured of confidentiality and had the right to refuse or withdraw at any time without consequences.

2.4 Data analysis techniques

Data analysis was conducted using thematic narrative analysis and socio-historical interpretation. The stages included:

1. Data analysis was conducted through a process of narrative coding applied to in-depth interview transcripts and field notes. This process entailed open coding to identify emerging themes, axial coding to connect categories, and selective coding to construct broader narratives of rural youth activism. Each selected narrative excerpt represents recurring patterns within the data, thereby reinforcing the credibility and robustness of the findings.

2. Historical contextualization, situating informant narratives within broader local and national historical frameworks (Tsing, 2005; Anderson, 2006).

3. Critical reading of dominant and counter-narratives, examining how history is constructed, erased, or reactivated within shifting social contexts.

4. Descriptive-quantitative analysis of the survey data to capture general trends in youth activism preferences and strategies. These results were then integrated into the thematic narrative to reinforce or contrast the qualitative findings. A limited-scale mixed-method approach was thus applied to enrich the understanding of rural youth activism complexity.

5. Source triangulation was conducted by cross-verifying narratives across various data types (interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and visual data) to ensure narrative validity.

The final interpretation is presented as an academic narrative that illustrates the historical dynamics, identity formations, and transformations in village youth patriotism in response to capitalist expansion and environmental crises.

3 Result

3.1 Cigombong: from colonial capitalist enclave to corporate oligarchic space

Since the 18th century, Cigombong (historically spelled Tjigombong) has served as a critical node in the colonial political economy of the Dutch East Indies. This period can be classified as a phase of extractive colonial capitalism, an economic system centered on the exploitation of natural resources and indigenous labor for the accumulation of surplus at the colonial core (Booth, 1998). Cigombong was integrated into the Prianganstelsel, a forced agricultural system oriented toward the export of commodities such as coffee and tea. Through both European private concessions and state-run enterprises, vast plantations were established in the area. Among the most prominent was Onderneming Tjigombong, which emerged as a major tea production site in southern Bogor. These plantations operated using forced indigenous labor (koeli), including youth, under grueling conditions and with minimal rights (Middelburgsch Nieuws, 1904).

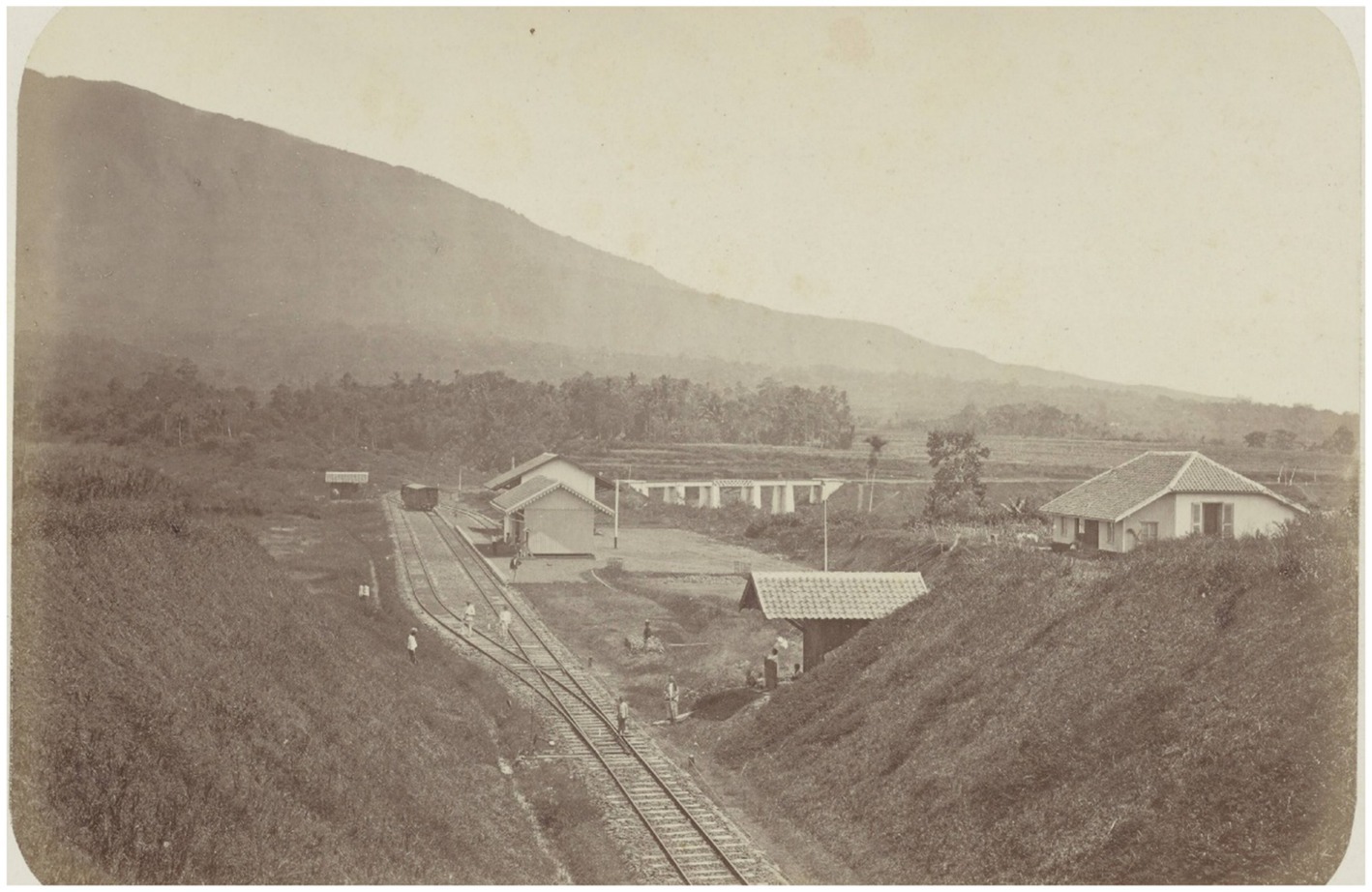

Cigombong’s integration into the colonial logistics network was further consolidated with the inauguration of Tjigombong Railway Station on 5 October 1881, as part of the Batavia–Buitenzorg–Sukabumi corridor. This railway enabled the efficient transport of agricultural commodities to export harbors in Batavia. As Subijanto (2016) notes, the Priangan railway served not only as the logistical backbone of the colonial economy but also as a channel for the circulation of subversive ideas among railway workers and native students.

In addition to its role as a productive and distributive hub, Cigombong was also constructed as an exclusive recreational enclave for colonial elites. By 1898, Lake Lido (then called Lidomeer or Het Meer van Tjigombong) had been developed as a leisure site, complete with swimming facilities and luxury lodging. Lido became a popular weekend destination for Batavia’s urban elite, featuring dance performances, convenient automobile access, and express train services that stopped directly in Tjigombong (Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 1937). A 1938 newspaper advertisement announced upcoming “wedstrijden” (entertainment contests) at the lake with low entry fees and a promise of “a delightful day,” underscoring the lake’s symbolic role as both a spatial aesthetic and a site of social segregation (Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 1938). Cigombong thus epitomized the spatial logic of colonial capitalist segregation, where forced labor and elite leisure were juxtaposed within a fragmented landscape. It underscored the classical dichotomy between exploitation and aesthetics, between the oppressed and the ruling class.

Cigombong also featured in the realm of colonial scientific experimentation. In a report from the Tea Research Station by Siahaja and van Vloten. (1919), systematic pest control trials were conducted against Helopeltis theivora on the Leuwimanggoe plantation, adjacent to Cigombong. Thousands of plants were sprayed using new methods as part of colonial scientific projects aimed at maximizing yields. This positioned Cigombong as a colonial agrarian laboratory, where science and technology served as instruments of power to optimize surplus production within the framework of capitalist control over tropical agriculture.

During the Indonesian Revolution (1945–1950), Cigombong underwent a transition toward bureaucratic-nationalist capitalism, in which the post-colonial state sought to reclaim colonial assets and reorient the economy under centralized control (Dick et al., 2002). The economy during this period was shaped not by market dynamics but by state intervention. Cigombong became not only an economic space but also a strategic military zone. Events such as the Battle of Bojongkokosan in December 1945 involved youth militias sabotaging railways and blocking NICA military convoys. Former koeli youth emerged as republican fighters under banners such as TKR, Hizbullah, and other resistance units (Nasution, 1979; Wiryono, 2010).

A significant transformation occurred during the New Order period (1970–1998), when the dominant form of capitalism in Cigombong shifted toward clientelistic and ersatz capitalism (Bocek, 2022; Robison, 1989). Under Suharto’s regime, national development was implemented in a centralized and top-down manner. In Cigombong, this was reflected in the revitalization of Lake Lido as a tourism destination, the expansion of smallholder plantations, and the establishment of the Mount Gede Pangrango National Park (TNGGP), formalized by Minister of Agriculture Decree No. 811/Kpts/Um/II/1980 in 1980. This conservation policy was not merely an ecological regulation, it also served as a spatial instrument of state control over rural areas. Within this clientelistic system, access to resources and development projects was monopolized by military elites and businessmen affiliated with the regime, rather than through open market competition.

In the post-Reformasi period (1999–2015), local political-economic space expanded as a result of decentralization. However, as critiqued by Robison & Hadiz (2004), decentralization in Indonesia did not dismantle the old power structures; instead, it reproduced them in new forms, what they term transitional-oligarchic capitalism. In this phase, local elites and emerging corporations entered arenas that were previously dominated by the centralized state. The establishment of Mount Halimun Salak National Park (TNGHS), based on Minister of Forestry Decree No. 175/Kpts-II/2003 in 2003, opened up opportunities for ecotourism and conservation initiatives, yet simultaneously triggered boundary disputes and land claims by local farmers. Conservation, in this context, became a paradox: a symbol of sustainability and a mechanism of spatial exclusion.

Since 2016, Cigombong has been swept into the currents of corporate oligarchic capitalism. The establishment of Lido SEZ through Government Regulation No. 69/2021 marks the culmination of this trajectory. The SEZ has transformed agrarian landscapes into elite tourism and real estate zones, reinforcing state-corporate alliances in the enclosure of rural space. According to the PT MNC Land Tbk (2020), Cigombong is envisioned as an integrated luxury tourism complex, comprising a theme park, resorts, creative city zones, and expansive elite residential areas. This reflects the logic of contemporary capitalism: spatial commodification, aestheticized development, and the legalized exclusion of subaltern classes.

This transformation has been accelerated by large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Bocimi Toll Road and the Bogor–Sukabumi double-track railway. Republik News (2023) and Yusuf (2013) describes this process as a territorial expansion of capital, generating socio-ecological pressure on local communities, including farmers and youth. Access becomes selective, living spaces are commodified, and rural social relations are replaced by market logic.

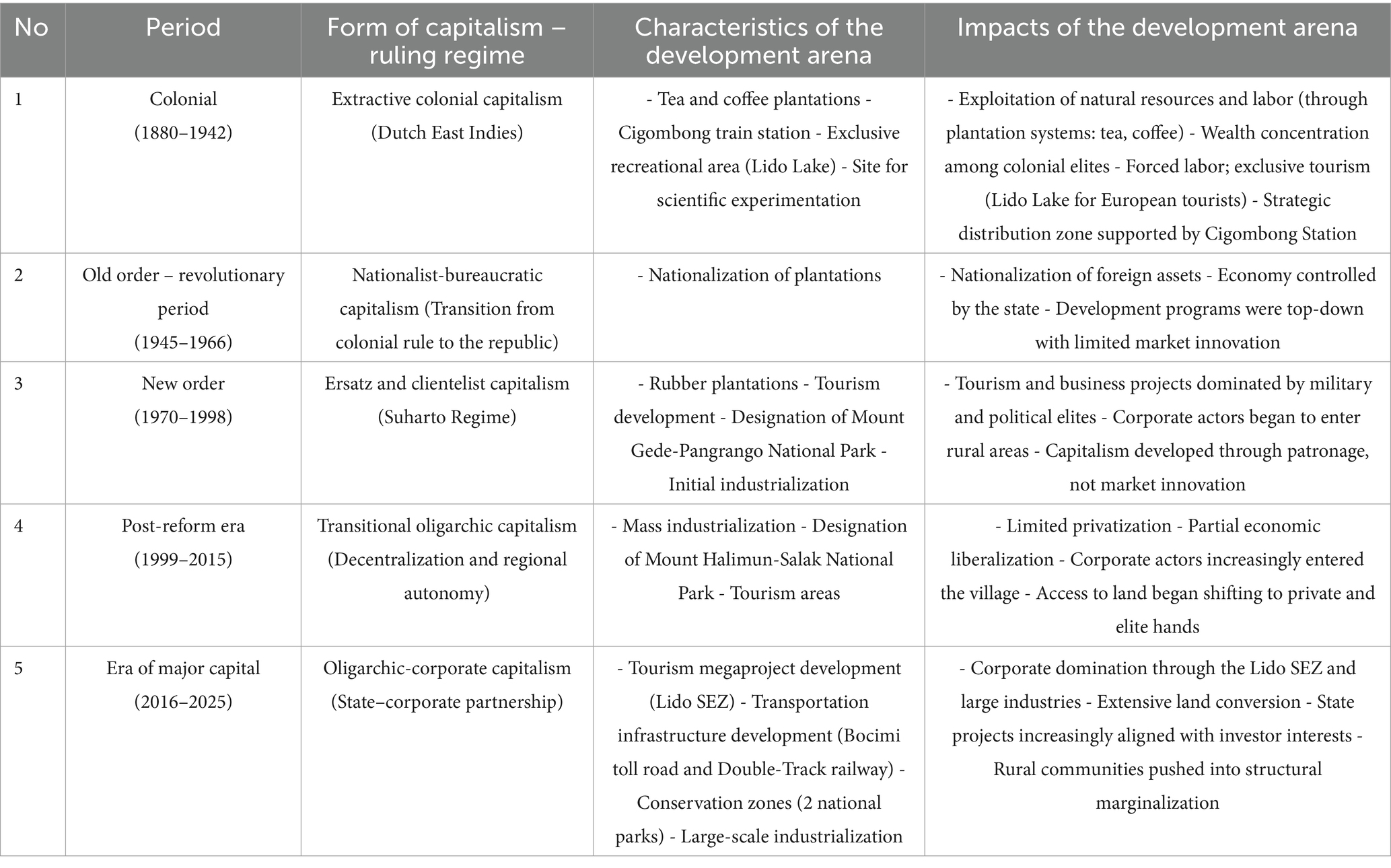

The complexity deepens given Cigombong’s location between two national conservation zones (TNGGP and TNGHS). A contradiction emerges: on one hand, the area is designated as an ecological buffer; on the other, it is reclaimed as an investment frontier. Massive development projects around Lido have threatened water catchment areas, the environment and wildlife habitats in the national park’s buffer zone (Syawie et al., 2023; Djakapermana, 2021). This is the face of rent-seeking corporate capitalism, wherein development projects operate amid legal ambiguity, sustainability rhetoric, and systemic marginalization. Within this context, Cigombong’s rural youth confront a structural dilemma: either assimilate into the developmentalist agenda or cultivate counter-spaces rooted in community and lived spatial histories. It is within this tension that multi-arena youth activism emerges (Table 1).

3.2 The historical trajectory of youth activism in Cigombong: from colonial subjugation to digital resistance

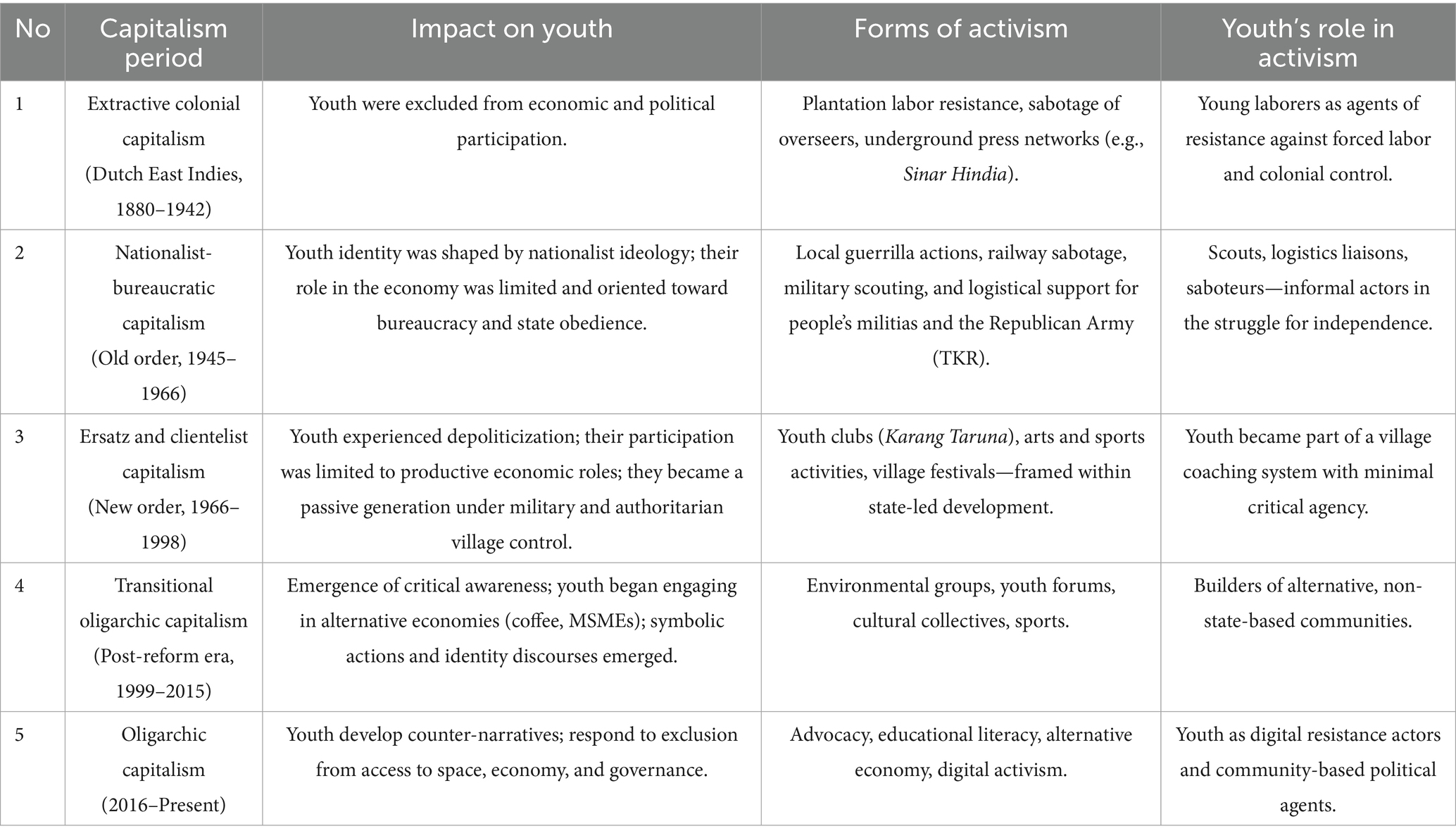

Following the examination of the political-economic transformation of Cigombong from the colonial era to the present, it is imperative to understand how evolving capitalist structures across regimes have historically shaped the consciousness, social positioning, and resistance strategies of rural youth. Youth activism in Cigombong did not emerge in a vacuum; rather, it is the cumulative product of long-standing historical processes, from colonial forced labor and militant roles in the national revolution, to ideological repression under the New Order, and finally to symbolic and digital forms of resistance under corporate-oligarchic capitalism (see Table 2).

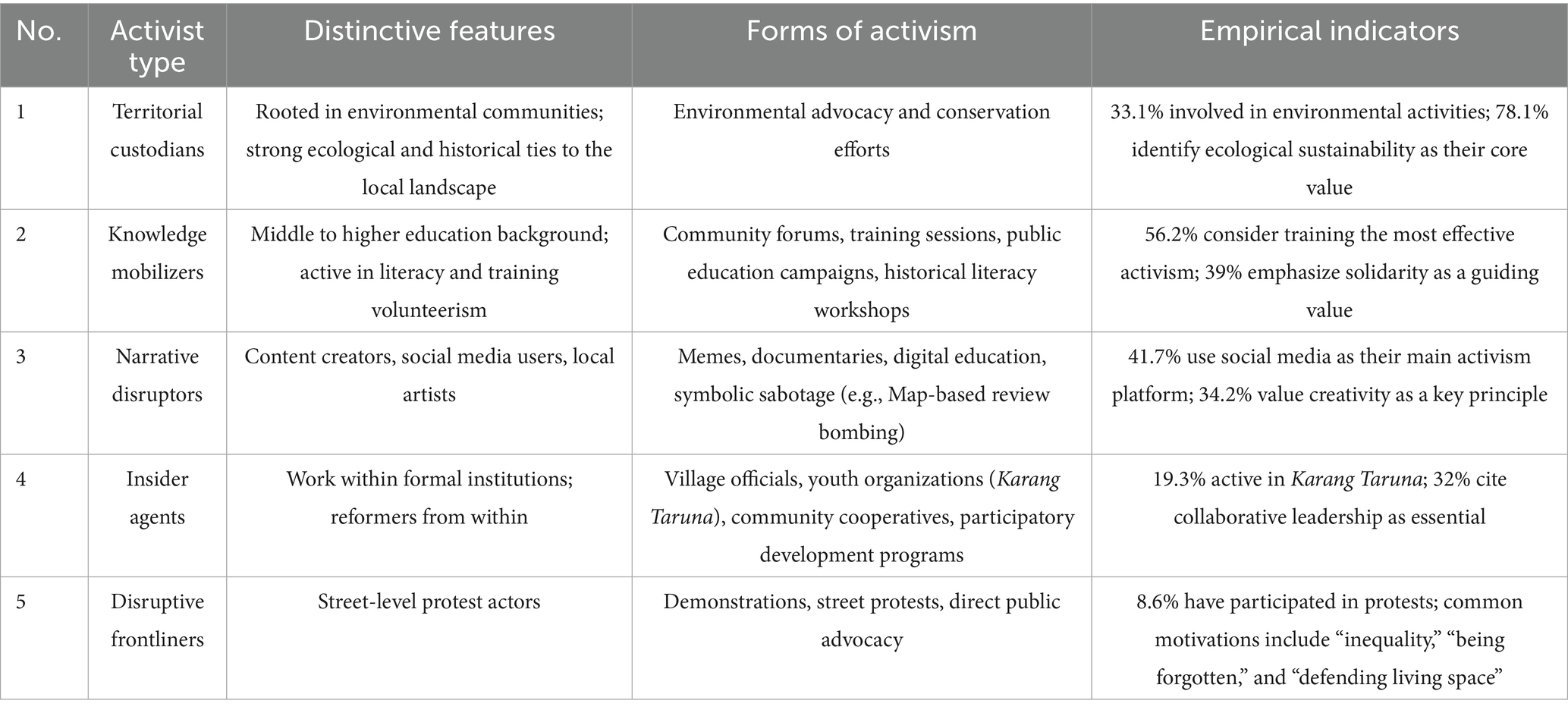

During the spatial consolidation of colonial capitalism between 1880 and 1942, the seeds of rural youth resistance began to emerge. Within the system of extractive colonial capitalism, where, as Booth (1998) notes, village spaces were subordinated entirely to the logic of export commodity production, local residents were excluded from equitable participation in the economy. One of the earliest documented acts of resistance occurred in the early 1930s when koeli laborers at the Onderneming Tjigombong plantation tied up the administrator and six foremen to rubber trees in protest of delayed wages. This event, recorded in Misstanden op een thee-onderneming Tjigombong (Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 1938), was not merely an expression of rage but an embryonic form of class consciousness. It reflected a nascent bottom-up resistance to power asymmetries in colonial capitalist relations, likely led by local youth who refused to remain passive laboring subjects and instead began to assert themselves as political actors (Table 3).

Hence, colonial Cigombong should not be seen as a peripheral rural space, but rather as a strategic node within the machinery of colonial capitalism, a space produced, exploited, and contested simultaneously. In this context, rural youth were not merely labor inputs; they embodied the early political subjectivity that would later shape historical consciousness and resistance (Table 4).

During the same period, anti-colonial and leftist movements began to infiltrate West Priangan, particularly Bogor and Sukabumi, via networks of newspapers and transport workers. Subijanto (2016) notes that outlets like Sinar Hindia played a key role in disseminating labor consciousness and revolutionary ideas among plantation workers. The rail corridor linking Batavia–Bogor–Cigombong–Sukabumi served as an underground communication route, connecting working youth, local activists, and bumiputra students. Although there is no direct archival evidence of Cigombong youth’s participation in these leftist networks, the structural connectivity to sites of agitation suggests that ideological dissemination likely contributed to the early development of political awareness among rural youth and laborers.

The role of Cigombong youth became more pronounced during the Indonesian Revolution (1945–1950), marking a shift from subordinated laborers under colonial capitalism to active agents of the republic. In the Battle of Bojongkokosan (December 9–12, 1945), part of the broader Convoy War, youth in Cigombong joined resistance units such as TKR, Hizbullah, Pesindo, TRIP, and Sabilillah. They sabotaged railway lines, served as scouts and logistical messengers, and directly confronted Allied-NICA convoys (Nasution, 1979; Wiryono, 2010; Mulyasari, 2010). This marked a critical transformation, from co-opted plantation workers to revolutionary militias advocating national sovereignty.

Oral histories with local historian BDW (age 45) further reinforce the narrative of youth resistance, particularly during the Maseng Incident, when the area of Maseng (in Cigombong) became a demarcation line of Republican defense against Dutch patrols between 1946–1949. BDW recounted that, on a clear afternoon, two military convoy vehicles carrying eight Allied soldiers were ambushed by locals: two soldiers were killed, two captured, and four fled. “The sound of gunfire could be heard all the way to the village,” he recalled, underscoring the vivid collective memory of the Maseng resistance. The Maseng Monument was later erected not merely as a symbol but as a territorial marker of the Van Mook Line of 1946. “Maseng is not just a place, it’s a boundary of struggle,” BDW affirmed.

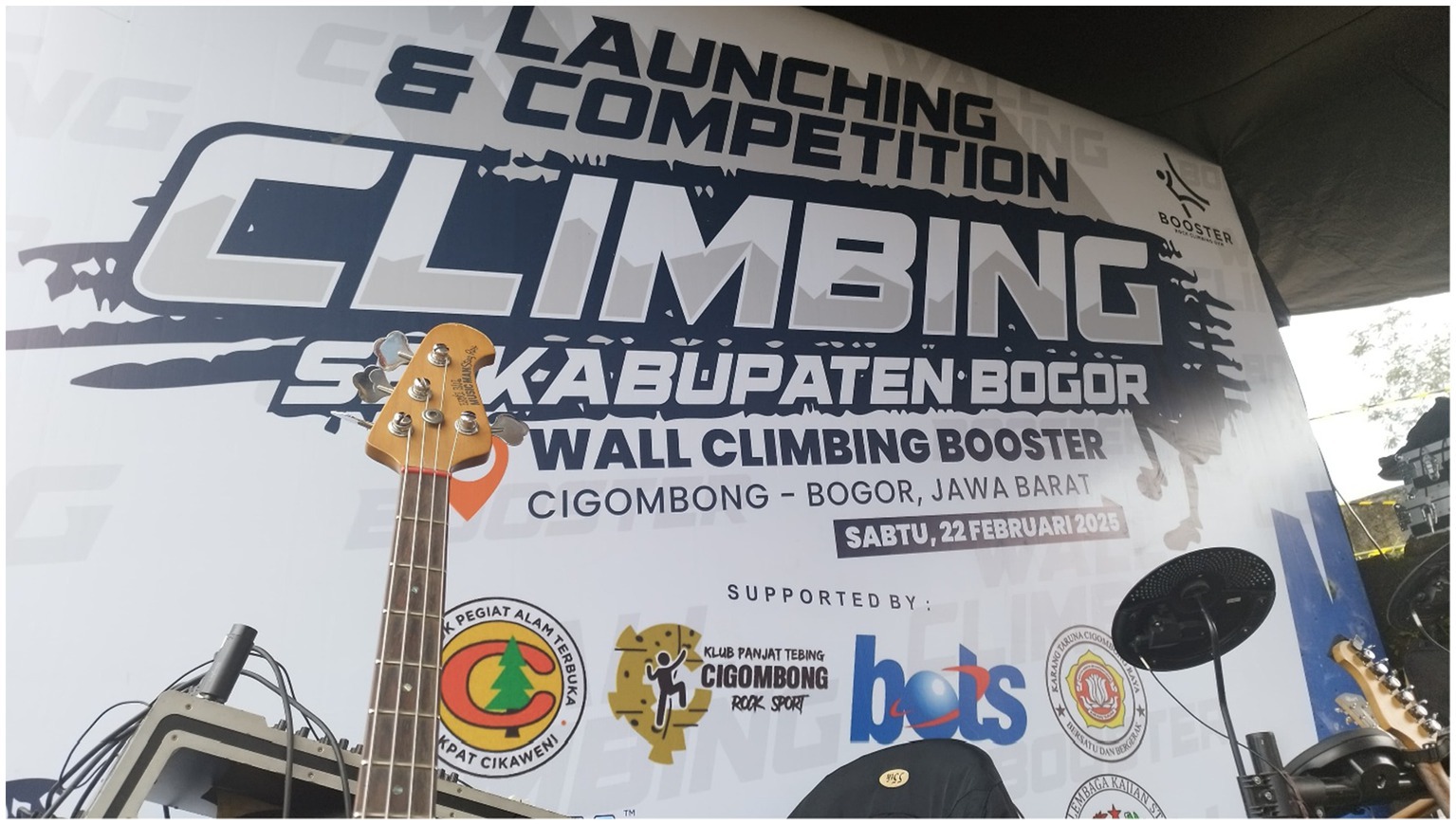

Under Suharto’s New Order, political space for rural youth was significantly curtailed. Youth activism was redirected toward “neutral” activities such as arts, sports, and karang taruna (state-sponsored youth organizations), tightly managed through processes of depoliticization and cultural normalization. Here, clientelist capitalism operated through the production of dominant symbolic dispositions (Bourdieu, 1996): youth were incorporated into development narratives but stripped of their political agency. Social and economic spaces were regulated by the state and military elites, implementing a form of ersatz capitalism in which participation was substituted by cultural control and bureaucratic assimilation (Figures 1–8).

Figure 2. Tjigombong Railway Station on the Buitenzorg to Soekaboemi line with Mount Salak in the background in1900 (source: digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl).

Figure 3. Canoeing sports activities during the Dutch colonial era at Lake Lido, 1930 (Source: digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl).

Figure 4. Group of Europeans and Javanese in front of the Tjigombong train station, 1930 (Source: digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl).

Figure 8. Two examples of graffiti murals regarding issues in Cigombong (Source: @mural_is_me dan researcher documentation).

Following the fall of the New Order in 1998, particularly from 2015 onward, new forms of youth activism began to surface, cultural, ecological, and digital in nature. Emerging collectives, including environmental groups, spatial literacy forums, and arts communities, became platforms for expressing contemporary resistance. In these spaces, youth activism moved beyond direct protest to adopt narrative, reflective, and memory-based approaches rooted in the collective historical consciousness of lived space. They revisited the narratives of agrarian violence, corporate control over Lake Lido, and spatial exploitation under elite tourism. As Said (1993) and Stoler (2008) remind us, colonial memory is not a relic of the past but an active source of political legitimacy in the present. Youth activism in Cigombong demonstrates that memory can function as political agency, that suppressed histories can be resurrected through murals, documentary films, digital sabotage, and informal discussion circles. This reflects a broader transformation of rural youth from passive subjects of capitalism to reflective actors in local political-economic arenas.

In sum, the historical trajectory of youth activism in Cigombong reveals a persistent continuity of resistance that has adapted to the shifting modalities of capitalism, extractive, bureaucratic, clientelist, and corporate-oligarchic. These youth do not merely reject exclusive development paradigms; they actively reconstruct inclusive and meaningful social spaces amid the increasing complexity of power regimes.

The history of rural youth activism in Cigombong is not a recent phenomenon born solely out of contemporary conditions. As narrated by BDW (45 years old), traces of activism can already be discerned from the colonial era, when Cigombong youth—who were part of Bogor’s youth movement—established one of the early nationalist organizations. ‘The significance of Bogor in the early history of the national movement is often forgotten. Many overlook that the first organization in Indonesia was founded in Bogor, not elsewhere,’ emphasized BDW. This historical trajectory serves as a symbolic legacy that provides moral legitimacy for the present generation. In other words, contemporary activism constitutes a continuation of the collective memory of local struggles, demonstrating the continuity between past resistance and the critical practices of today’s youth.

3.3 Contemporary youth activism: patterns, strategies, and value

Youth activism in Cigombong in the contemporary era is inseparable from the increasingly complex transformations of capitalism, where the village is no longer merely an agrarian production space, but has been commodified into an arena for elite tourism, property speculation, and corporate investment. Within this context, youth resistance has emerged in a social landscape marked by ambiguity, tension, and hybridity, as theorized within the frameworks of oligarchic capitalism (Robison and Hadiz, 2004) and rentier corporate capitalism (Winters, 2011).

Rather than forming centralized, structurally organized movements, the activism observed reflects the logics of new social movements (Touraine, 1985; Melucci, 1996), rooted in identity, cultural values, and symbolic expressions that are fluid, reflective, and situated in everyday life. Contemporary rural youth movements are not always overtly confrontational but manifest in dispersed forms of social articulation through daily practices, digital platforms, and alternative economic strategies. These actors operate within spaces heavily shaped by corporate-oligarchic capitalism, while simultaneously seeking to produce counter-spaces of resistance.

3.3.1 Patterns and characteristics of activism: fragmented arenas and tactical dispersion

Youth activism in Cigombong operates across five overlapping arenas, each reflecting efforts to reclaim spaces colonized by capital:

1. Living space activism, focused on forests, gardens, and hiking trails, where youth engage in ecological advocacy and social conservation efforts to protect areas threatened by the Lido SEZ and infrastructural expansion. These practices constitute a resistance to the commodification of nature characteristic of corporate environmental capitalism.

2. Cultural arenas, where youth articulate resistance through music, murals, theater, and local festivals. These expressions are reflective and rooted in shared identity.

3. Digital space, where activism unfolds through social media, online education, and symbolic sabotage such as review bombing. These acts exemplify the “disruption narrative,” utilizing memes, visual content, and digital storytelling as tools for critique.

4. Alternative economic arenas, including village cafés, eco-tourism, cooperatives, and small enterprises (UMKM). These initiatives seek to construct parallel economies that defy the logic of large-scale capitalist accumulation.

5. Symbolic protest arenas, including demonstrations at Lake Lido, direct actions, and the occupation of public space for visual-political expression.

These five arenas form a loosely connected yet resonant network of youth activism grounded in shared narratives and collective memory. While often temporary, such actions possess strong moral and political resonance. Survey data confirm these patterns: 72% of respondents engage in social and environmental activities, while 56.2% identify training and awareness programs as the most impactful forms of activism. Only 8.6% report participating in direct protests. This suggests that under oligarchic capitalist conditions, where formal political channels are captured by elites, youth tend to adopt narrative-driven, flexible, and participatory strategies, albeit still deeply political.

Based on qualitative observations and questionnaire findings, youth activists in Cigombong can be categorized into several overlapping typologies:

1. Environmental stewards, who focus on ecological preservation and forest conservation. These youth are often community-based, unaffiliated with formal organizations, and deeply connected to the local landscape.

2. Educator-activists, who disseminate critical knowledge through literacy forums, training programs, and the production of educational materials. This type is commonly found among youth with secondary or tertiary education. 56.2% of respondents view educational approaches as the most effective pathway for change.

3. Symbolic-digital activists, who utilize social media, visual arts, and digital content to construct counter-narratives. These individuals create alternative interpretations of development projects through visuals, stories, and digital interventions such as review bombing. 41.7% use social media as their main platform for expression, and 34.2% value creativity as a core element of their activism. Within this digital ecosystem, activism takes new forms: review bombing is deployed to damage the image of exclusive projects; memes and short videos serve as ‘soft weapons’ to deconstruct development claims; while digital documentation—photos, murals, or oral histories transformed into online formats—revives local history as symbolic capital. In doing so, digital platforms generate an algorithmic habitus in which creativity, speed, and technical skill become new forms of capital convertible into socio-political legitimacy. Through this space, Cigombong youth demonstrate that, despite the overwhelming economic and political power of corporate capitalism, local narratives preserved and disseminated through digital ecosystems can effectively counter, and even cultivate, new solidarities across spaces.

4. Integrative activists, who engage from within official structures such as Karang Taruna or village councils. Although only 19.3% are involved in such bodies, some attempt to push sustainability and social economy issues into official deliberations and programs.

5. Confrontational-symbolic activists, who participate in mass protests and direct confrontations with authorities. Though a minority (8.6%), they serve as crucial disruptors of structural silence and as symbolic challengers to spatial exclusion.

These typologies are not rigid, individuals often operate across multiple categories depending on the arena and context. Viewed through a rural sociology lens, these youth are not merely operating within pre-existing structures but are actively producing new social spaces through the narratives, networks, and symbols they construct. The arena of youth activism is no longer confined to physical demonstrations but has expanded into spaces of literacy, discussion forums, and digital media. A young Cigombong activist engaged in literature observed: ‘I see discussion and literature as a way to cultivate the critical reasoning of youth, through social and cultural literacy, we reflectively engage with village and political issues’ (CMA, 25 years old). This arena is further extended through symbolic production on social media—memes, posters, and digital reviews—that operate as forms of symbolic protest without necessitating street mobilization. Informal spaces, such as coffee shops and WhatsApp groups, also serve as effective forums for fostering collective consciousness. In this way, today’s rural youth activism underscores a shift from physical confrontation to discursive, literary, and digital arenas.

3.3.2 The dynamics of activism: hybrid strategies and social adaptation

Youth activism in Cigombong unfolds in a dynamic and contested landscape, between the expansion of capitalist space and conservationist regulation, between demands for inclusion and political exclusion, between developmentalist discourse and repressed historical memory. In this complex terrain, youth activism assumes hybrid forms, not always confrontational, yet fundamentally political.

Drawing on ethnographic fieldnotes and survey data, three interlinked strategies emerge:

1. Structural adaptation, where youth navigate institutional constraints at the village level. Village bureaucracy often excludes youth from meaningful participation, reducing them to ceremonial roles. In response, activism emerges through informal structures, environmental communities, coffee shop discussions, and literacy-based educational initiatives. Only 19.3% engage in formal organizations, whereas 41.7% express their voices through community spaces and social media, indicating a retreat from rigid institutions in favor of horizontal, trust-based networks.

2. Symbolic resistance, where youth adopt digital and symbolic interventions when local political structures fail to represent them. This includes protests at Lake Lido and digital sabotage of SEZ-related content. These actions, while low in physical confrontation, gain visibility and resonance through digital amplification. Youth transform the meaning of space through memes, documentaries, murals, and other cultural forms. Survey data support this: only 8.6% have participated in direct protests, while over 56% consider training, media, and creative work as the most effective tools for change. This indicates a shift from confrontational to representational strategies.

3. Survival in the gray zone, seen among youth balancing pressures from corporate expansion and conservation regulation. For example, youth in Ciwaluh Village—engaged in farming and ecotourism, operate on lands caught between the SEZ and national park boundaries. Rather than direct opposition, they pursue limited collaborations: developing community-based tourism, creating environmental education programs, and building social capital through inclusive economic practices.

This strategy reflects a form of reflective agency, in which youth adjust to structural constraints while retaining a sense of political engagement. These three strategies, structural adaptation, symbolic resistance, and survival, demonstrate that rural youth activism in Cigombong does not follow a singular logic. Instead, it forms a polyphonic tactical landscape, mobilizing old and new repertoires across overlapping arenas. Activism here is not only born of anger, but of care; not always loud, but persistently protective of living space, narrative, and values. In this light, Cigombong’s rural youth are not mere objects of structural transformation, but active subjects reshaping the local sociopolitical terrain, navigating an ever-shifting constellation of power, ambiguity, and resistance.

3.3.3 Rural youth values underpinning activism for sustainability and economic-political inclusion

Amid the structural pressures of oligarchic-corporate capitalism—manifested through Special Economic Zone (SEZ) projects, land privatization, and the co-optation of public spaces—youth activism in Cigombong is not solely expressed through collective mobilizations, but also through a set of ethical values that guide their political orientations. These values are not merely personal motivations, but rather the product of collective experiences shaped by direct encounters with spatial injustice, historical oppression, and economic-political exclusion.

In the sociology of social movements, values can be understood as moral-practical frameworks that structure collective articulations and direct strategic choices (Polletta and Jasper, 2001). These values distinguish between activism as an expression of identity and activism as a strategy for transformative change. In the case of Cigombong, these values are not imported from external institutions or ideological doctrines; instead, they emerge organically from below, rooted in everyday interaction, historical memory, and the lived experience of dispossession under capitalist logic.

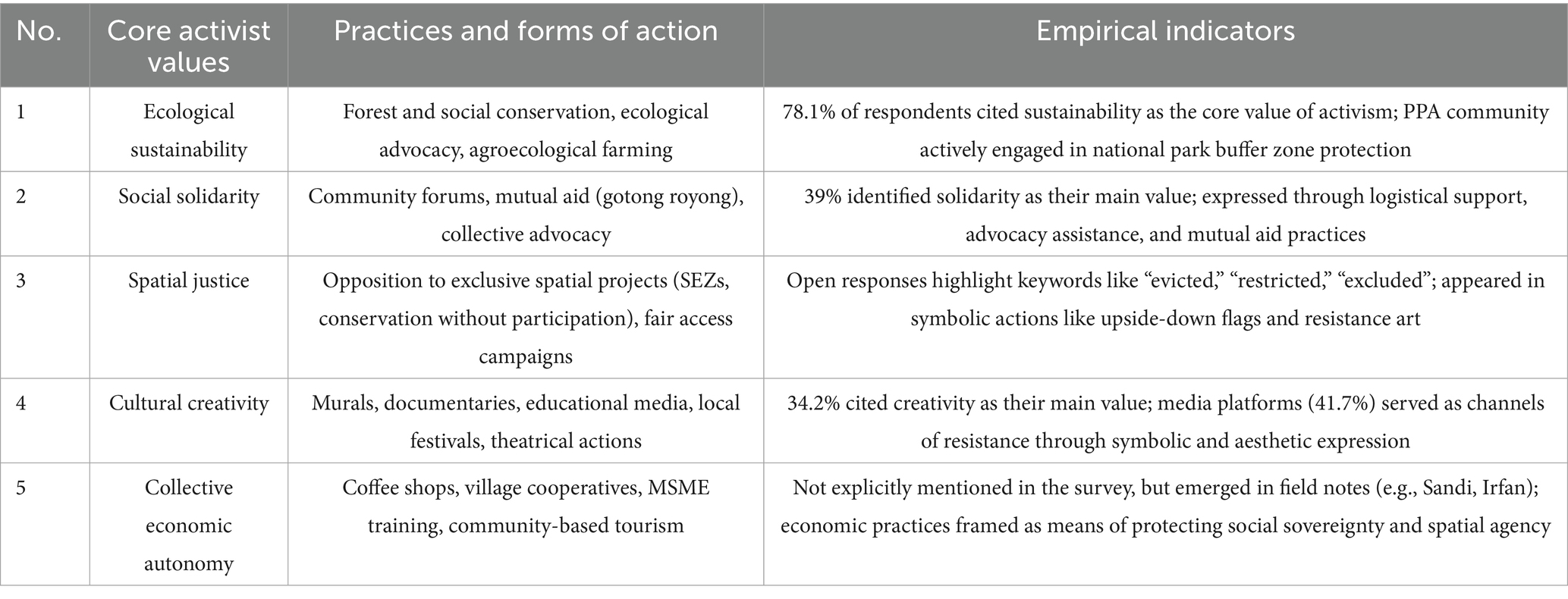

At least five core values constitute the moral foundation of rural youth activism in Cigombong: ecological sustainability, social solidarity, spatial justice, cultural creativity, and collective economic self-reliance. These values shape a vision of activism that is not only political, but also ethical and long-term in scope.

3.3.3.1 Ecological sustainability: living space as inheritance and social right

Youth engaged in environmental and organic farming communities often express their actions as grounded in the value of sustainability. This is not merely a modern ecological awareness but a lived understanding of space as a social body. From forest preservation efforts to resistance against lake privatization, their defense of the environment is rooted in a collective continuity of life, not in abstract ideals. According to survey data, 78.1% of respondents identified environmental sustainability as a core value of their activism. For them, nature is not just a resource—it is a place of learning, dwelling, and building solidarity.

3.3.3.2 Social solidarity: moving together, surviving together

Solidarity is enacted through collective labor, mutual aid among communities, and cross-issue discussion forums. Cigombong youth activism rejects individualism and is instead rooted in communal values and informal networks. Field notes document how youth communities share resources, knowledge, and even risk in facing development threats. 39% of respondents identified solidarity as their most fundamental value. This solidarity does not derive from formal organizational affiliation but from shared experiences of crisis and injustice.

3.3.3.3 Spatial justice: resisting inequality, demanding access

This value is particularly salient in activism related to land conflicts, SEZ development, and conservation zones. Youth demand fair access to spaces they have long stewarded and inhabited. Their notion of justice is not limited to resource redistribution, but includes recognition of their moral rights as villagers with historical and social ties to the land. In open-ended survey responses, terms like “evicted,” “restricted,” and “excluded” appear frequently, pointing to a collective trauma tied to spatial exclusion. Justice, in this context, functions as counter-hegemony to top-down, non-participatory development logics.

3.3.3.4 Cultural creativity: expression as resistance

Cigombong youth resist not only through argumentation but also through art, symbols, and narrative. Music, murals, documentaries, memes, and theatrical performances are not mere communication tools, they are expressions of the value that creativity is empowerment. Cultural activism becomes a space to expand political imagination and circumvent the stagnation of closed formal structures. 34.2% of respondents consider creativity to be a key value in their activism. They reject the need to replicate the styles of past movements and instead forge new forms aligned with the specificities of their generation and place.

3.3.3.5 Collective economic self-reliance: acting without waiting for state programs

Amid widespread distrust of government and state-led development programs, some youth build independent economic capacities. Coffee cooperatives, microenterprise trainings, and social tourism collectives exemplify activism grounded in autonomy yet rooted in collective labor. These youth do not wait for the state, they produce their own solutions through flexible and inclusive organizing. Economic activities here are not only about livelihood, but also about preserving political agency as rural citizens.

These values are not merely normative ideals but constitute a collective ethics emerging from the structural and relational experiences of youth struggling against exclusionary and silencing capitalist forces. As Polletta and Jasper (2001) argue, such values play a crucial role in shaping the collective identity of social movements, bridging personal reflection with collective political action. In this light, youth activism in Cigombong is not simply aimed at political goals; it embodies an ethical vision of a rural space that is just, sustainable, and inclusive, a form of grassroots politics that reclaims the village not as an object of capital, but as a lived and contested social space.

4 Discussion: from a broken history to a new patriotism (memory, identity, and the challenges of Cigombong’s rural youth)

History is not merely about the past, it is about how a community remembers, articulates, and reconfigures its collective identity in confronting the present. In the village of Cigombong, the history of youth resistance was once vividly etched in events such as railway sabotage, assaults on Allied troops during the Maseng Incident, and the bravery of people’s militias in challenging colonial and post-colonial dominance. Today, that history has nearly become a cold archive, no longer alive in the social consciousness of rural youth. This aligns with findings by Sjaf et al. (2024), who argue that the rupture of local narratives weakens community agency in responding to external development interventions detached from cultural contexts.

A local history teacher (BDW, 45) described Cigombong as a “transitional zone,” a place where modernity has arrived without fully replacing tradition, and tradition has faded without passing on its core values. In this liminal setting, youth grow up as social actors not only adrift in the current of digital information but also vulnerable to being uprooted from the symbolic foundations that once shaped their community’s courage.

4.1 Village capitalism and the identity crisis of youth

Halbwachs (1992) reminds us that collective memory is not a relic of the past, but a social practice shaped by relationships, institutions, and symbols. When Cigombong’s youth no longer know their local history, unaware of figures like Kiai Alit, or the meaning of the Maseng Monument, the issue is not mere ignorance but a structural rupture in the symbolic reproduction of history. As Connerton (1989) notes, a society that loses the practice of remembering also loses its capacity to act collectively.

The absence of unifying figures today also signals a void of capital symbolique (Bourdieu, 1986), the symbolic capital capable of binding social affiliation and loyalty. Without a respected local leader as the axis of movement, the youth lack political and moral orientation. In this context, history does not merely function as a narrative, it becomes a lost source of legitimation for collective action.

As Tsing (2005) writes, capitalism does not arrive as a singular, homogeneous force, it emerges through friction, between the local and the global, between tradition and market logic. In Cigombong, these frictions are palpable. Youth live in the shadow of mega-projects like the Lido Special Economic Zone (KEK), large-scale infrastructure development, and corporate expansion that steadily erode their land, water, and the symbolic spaces of their everyday lives. Ironically, amid such pressures, they lack structural tools to make sense of their situation, as the history of local resistance has been severed from daily discourse. Kolopaking et al. (2022) argues that such crises often arise when participatory spaces are not accompanied by the reinforcement of the community’s historical and symbolic meaning of place.

This condition places youth in a liminal space (Turner, 1969), neither fully rooted in tradition nor fully grounded in modern identity. As a result, they become reactive, easily provoked by populist issues but unable to sustain long-term consolidation. As Shiraishi (1997) observed, post-New Order Indonesian youth are a generation living amidst the fragmentation of political identity, often acting in sporadic, unorganized forms of expression.

4.2 Local history as the symbolic capital of Cigombong youth

From Bourdieu (1986) perspective, local history can be understood as cultural capital, not merely knowledge of the past, but also symbolic legitimacy that grants moral authority to collective action. In Cigombong, historical traces such as the Maseng Incident, the Battle of Bojongkokosan, and the resistance against the Onderneming Tjigombong constitute a reservoir of values that should serve as capital symbolique for the younger generation. Yet, as field observations reveal, the rupture of historical narratives has rendered history frozen as an archive, no longer functioning as symbolic capital that can be mobilized for the consolidation of movements.

The absence of transmission of local history has deprived youth of a habitus rooted in collective experiences of resistance. Habitus, in Bourdieu’s terms, is a system of dispositions that guides action without conscious reflection. When this historical habitus is severed, Cigombong youth confront a crisis of orientation: they respond reactively to issues but lack a deeper narrative of legitimacy. Murals depicting Maseng or digital campaigns on local history initiated by literacy groups and art communities exemplify attempts to reclaim history as symbolic capital. These practices demonstrate how youth endeavor to reconvert local history into new forms of cultural capital to be invested in contemporary arenas of activism, whether in environmental advocacy, resistance against the Lido Special Economic Zone, or the construction of a sovereign village identity.

In this context, local history is not only memory but also a strategic resource convertible into moral legitimacy. As Halbwachs (1992) reminds us, collective memory loses its force if it is not enacted. Cigombong youth who re-archive the history of Maseng through digital documentaries or rewrite local narratives in literacy forums are actively working to reverse this rupture. They animate history as embodied cultural capital, knowledge, skills, and sensibilities inscribed in their social being.

Furthermore, local history can be read as a counter-capital against the logic of corporate capitalism. While capitalism relies on economic and political capital to dominate rural spaces, Cigombong youth deploy history as cultural capital to assert rights over land, water, and livelihood. The Maseng monument, murals of resistance, and oral accounts of the Black Troops function as symbolic resources capable of binding solidarity even in contexts of scarce material resources.

At the same time, this symbolic capital does not stand alone. It is translated into local patriotism, a collective attachment to land, ancestors, and community that simultaneously serves as a form of social capital. This patriotism nurtures trust, networks, and norms of reciprocity that reinforce youth alliances across groups and generations. When Cigombong youth safeguard sacred graves, develop community-based ecotourism, or archive resistance narratives, they are not merely preserving history but also strengthening social ties that expand their capacity for collective action. In this sense, local patriotism functions doubly—as both a symbolic and social resource—binding youth to their community while enabling them to forge solidarities capable of countering the asymmetrical power of corporate and state actors.

Within the social arena (Bourdieu, 1984), the interweaving of cultural and social capital derived from history and patriotism becomes a weapon for negotiating youth’s position. They are no longer merely “village children” reacting to events, but rightful heirs of a tradition of resistance and custodians of communal solidarity. Put differently, local history serves as a “card of legitimacy,” while local patriotism becomes the connective tissue sustaining collective agency. Together, they enable Cigombong youth to speak, demand, and even resist development projects that displace communities. Here, history is not nostalgia, and patriotism is not blind loyalty; rather, both are living capitals that can be mobilized to construct a new rural citizenship, rooted in local experience yet responsive to global challenges.

4.3 Bottom-up nationalism and a new patriotism

Benedict Anderson (2006), in Imagined Communities, emphasized that nationalism is not merely a state-led project, it is a social and imaginative practice shaped by language, narrative, and symbols. In Cigombong, bottom-up nationalism once thrived, seen in colonial resistance, railway sabotage, and community defense against foreign intervention. Today, this nationalism no longer takes the form of militias, but is expressed symbolically through murals, environmental communities, and digital documentation of local history by youth.

Rural youth patriotism is embodied in everyday practices of defending community livelihoods and identities. As one young villager explained, ‘If people can earn an income from tourism, they will not sell their land. This is our form of struggle. Rather than staging protests, we keep Ciwaluh alive’ (WSA, 34). Such forms of everyday resistance illustrate how youth sustain the village through community-based ecotourism. Another youth emphasized the generational dimension: ‘The key is not to let them struggle alone. Give them space, give them education, and give them a stage’ (XSS, 36). Meanwhile, narratives surrounding disputes over sacred graves highlight a culturally grounded patriotism, where sacred spaces are preserved as symbols of village identity and continuity. In this sense, rural youth patriotism is not merely symbolic loyalty but a set of socio-economic, cultural, and generational practices aimed at safeguarding village sustainability.

These expressions reflect what Tsing (2005) calls engaged localism, resistance that does not depend on the logic of state power or elite actors, but emerges through ethnographic engagement with place and experience. Murals depicting drying springs, digital campaigns about the Maseng history, and community tourism groups (Pokdarwis) creating new narratives of local identity, all represent a form of new patriotism rooted from below, from the village body itself. This is in line with the Nusantaranomics paradigm proposed by Damanhuri et al. (2023), which stresses the importance of resistance ethics grounded in local values and community spirituality as foundations for sustainable and non-co-opted struggle.

Scott (1985), in Weapons of the Weak, has long emphasized that resistance does not always appear as mass mobilization, it can manifest as “quiet weapons” in everyday life. In Cigombong, this new patriotism does not march in parades, but lives in the care of narratives, the defense of space, and the archiving of local history. A living history is not just written, it is enacted. It appears in practice, in space, and in language. Thus, the challenge for Cigombong’s youth is not to create a new history, but to rediscover one that has been buried by time and dominant systems of knowledge. The future direction of rural youth will not be shaped by empty development discourse or superficial participatory projects. It must begin with the excavation of history, not as nostalgia, but as a symbolic resource and strategy of action. The legacy of resistance in Cigombong—from the SDI, Maseng, and Laskar Hitam, to murals and environmental communities, must be returned to the youth. Not to be memorialized, but to be lived and reinterpreted within the context of their times. As stated in a field reflection, “What is lost is not the history itself, but the way we care for it.” (BDW, 43, local historian).

In this light, history becomes not only memory but also strategic capital for building movements. When young people know that others before them have resisted, they understand that resistance is not new—it is an inherited legacy that must be nurtured. Therefore, constructing rural youth identity today requires two things: first, a reconstruction of living and grounded local history; and second, the creation of social spaces that allow youth to build organization, leadership, and new forms of political expression. Only then will village patriotism cease to be a relic of the past and become a compass for the future. Village patriotism is the courage to defend everyday life: land, water, memory, and dignity.

5 Conclusion

Youth activism in Cigombong should not be understood merely as a reactive response to exclusionary development projects, but as the outcome of a long historical process that has shaped collective memory, ethical values, and political agency under the pressure of oligarchic-corporate capitalism. From colonial forced labor and revolutionary struggle, to ideological repression under the New Order, and now to digital resistance and symbolic activism, the trajectory of rural youth resistance demonstrates a dynamic and historically grounded continuity.

Capitalism does not operate in a vacuum, it penetrates the social fabric, everyday life, and spatial identity of the village. Yet, as this study has shown, rural youth are not passive subjects. They have created counter-spaces through symbolic practices, alternative economies, digital narratives, and collective values. Their act of reclaiming history is not nostalgia, it is a political strategy for confronting present injustices.

The local patriotism embodied by Cigombong’s youth is not about blind allegiance to the state or its elites. It is about the courage to defend everyday life, land, water, memory, and dignity. This is a form of grassroots nationalism rooted not in flags or slogans, but in community and survival. These young people are not rejecting modernity; they are negotiating it critically and communally.

By reconstructing history as a political resource and upholding values of ecological sustainability, spatial justice, solidarity, creativity, and collective autonomy, Cigombong’s youth have shown that the village is not a passive site of development. It is a living arena of struggle, imagination, and resistance. The future of rural youth will not be defined by top-down development agendas, but by their ability to reinterpret the past and chart new pathways from below. History is not merely to be remembered, it must be carried forward, through forms of resistance that continue to adapt and endure.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Due to confidentiality agreements and ethical considerations, the raw data are not included in the manuscript or supplementary material. However, de-identified data may be made available by the author upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Rajib Gandi, cmFqaWJfZ2FuZGlAYXBwcy5pcGIuYWMuaWQ=.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because this study did not require formal ethical approval, as it involved only non-invasive social research methods with voluntary participation and anonymized data, and was conducted in accordance with international ethical standards for social sciences. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RG: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology. LK: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. DD: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SS: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was conducted with self-funding by the authors.

Acknowledgments

This research was independently funded and emerges from a deep engagement with the lived experiences of rural youth and communities in Cigombong. The author extends sincere gratitude to all informants whose generosity, narratives, and acts of resistance gave life to this study. This work is respectfully dedicated to the rural youth who, amidst the overlapping pressures of mega-development, industrial intrusion, and conservation regimes, continue to defend their spaces and envision alternative futures. Their agency, dignity, and perseverance are the spirit that animates this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT by OpenAI) was used to assist in language polishing, restructuring academic paragraphs, and translating sections from Indonesian to English. All content was subsequently reviewed, edited, and approved by the author.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baizhumakyzy, Z., Tangkish, N., Mazhinbekov, S., Sarsenbekov, Z., and Korganova, S. (2025). Fostering democratic engagement: factors shaping youth political participation in Kazakhstan. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1561187. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1561187

Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad. (1938). “Wedstrijden op het meer van Tjigombong ”. Batavia: Delpher Digital Library.

Bocek, F. (2022). Ersatz capitalism and industrial policy in Southeast Asia: a comparative institutional analysis of Indonesia and Malaysia : Routledge.

Booth, A. (1998). The Indonesian economy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. London: Macmillan.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) in Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. ed. R. Nice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital” in Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. ed. J. G. Richardson (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 241–258.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Damanhuri, D. S., Yustika, A. E., Darmawan, A. H., Prasetyantoko, A., Ishak, A., Suyanto, B., et al. (2023). Nusantaranomics: Paradigma Teori dan Pengalaman Empiris (Pendekatan Heterodoks). Bogor: IPB Press.

Dick, H., Vincent, J. H., Houben, J. T., and Lindblad, d. K. W. T. (2002). The emergence of a national Economy: An Economic History of Indonesia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1800-2000.

Djakapermana, R. D. (2021). “Penguatan Pengendalian Pemanfaatan Ruang di Kawasan Jabodetabekpunjur Secara Konsisten.” Prosiding ASPI. Available online at: https://e-journal.unmas.ac.id/index.php/semnaspi2021/article/download/3047/2392

Halbwachs, M. (1992) in On collective memory. ed. L. A. Coser (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië. (1937). “Het Lido onder nieuw beheer.” Batavia: Delpher Digital Library.

Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië. (1938). “Tocht near Tjigombong-Meer.” Batavia: Delpher Digital Library.

Kolopaking, L. M., Wahyono, E., Irmayani, N. R., Habibullah, H., and Erwinsyah, R. G. (2022). Re-adaptation of COVID-19 impact for sustainable improvement of Indonesian villages' social resilience in the digital era. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plann. 17, 2131–2140. doi: 10.18280/ijsdp.170713

Kumar, U. (2025). Exploring the roles of agrarian working class women in agrarian struggles: participation, mobilization, and organizations in postcolonial Bihar, India. Cogent Arts Humanit. 12:2524580. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2025.2524580

Li, T. M. (2014). Land’s end: Capitalist relations on an indigenous frontier. Durham: Duke University Press.

Lorente, J., and Jiménez-Bravo, I. (2025). A future of authoritarian citizens? Explaining why Spanish youth are losing faith in democracy. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1553307. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1553307

Marimón Llorca, C., and Roche Cárcel, J. A. (2025). From the war in youth to the trauma of defeat, repression and exile: images and discourses of Spanish republican aviation. Cogent Arts Humanit. 12:2442806. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2024.2442806

Melucci, A. (1996). Challenging codes: collective action in the information age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mulyasari, S. (2010). “Sejarah Perkembangan Museum Perjoangan Bogor.” Jakarta: UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta.

Pan, L. (2024). Repertoire of youth activism in 1970s Hong Kong: the 70s biweekly and experimental cinema. Cogent Arts Humanit. 11:2357885. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2024.2357885

Polletta, F., and Jasper, J. M. (2001). Collective identity and social movements. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 27, 283–305.

Ponton, D. M., and Raimo, A. (2024). Framing environmental discourse: Greta Thunberg, metaphors, blah blah blah! Cogent Arts Humanit. 11:2339577. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2024.2339577

PT MNC Land Tbk. (2020). Lido SEZ Masterplan: MNC Lido City – A New City Concept. Jakarta: PT MNC Land Tbk. Available at: https://www.mncland.com

Republik News. (2023). Pembangunan Tol Bocimi serta dampaknya terhadap wilayah sekitar. Republik News. Available at: https://republiknews.com/penbangunan-tol-bocimi-serta-dampaknya-terhadap-wilayah-sekitar/

Robison, R. (1989). Book review: the rise of ersatz capitalism in Southeast Asia by Yoshihara Kunio. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 25, 119–123. doi: 10.1080/00074918912331335539

Robison, R., and Hadiz, D. V. R. (2004). Reorganising power in Indonesia: The politics of oligarchy in an age of markets. London: Routledge.

Scott, J. C. (1985). Weapons of the weak: Everyday forms of peasant resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Shiraishi, T. (1997). Young heroes: The Indonesian family in politics. Ithaca: Cornell Modern Indonesia Project.

Siahaja, E. L., and van Vloten, D. O. (1919). Helopeltis-Bestrijding op de Onderneming Leuwimanggoe. Proefstation voor Thee. Batavia: Ruygrok & Co.

Sjaf, S., Fitri, M. A., Lestari, A., Rachman, A., and Nugroho, D. R. S. (2024). The role of local Agency in Precision Village Data and Sustainability Development. IOP Conf. Ser. 1359:012061. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1359/1/012061

Stoler, A. L. (2008). Along the archival grain: Epistemic anxieties and colonial common sense. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Subijanto, B. (2016). Media of Resistance: Control and subversion in colonial Java. Leiden: Leiden University.

Surrenti, S., and Di Felice, M. (2025). Rethinking social action through the info-ecological dimensions of two collaborative public health platforms: the people’s health movement and the citizen sense project platforms as examples of health-net-activism. Front. Sociol. 10:1602858. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2025.1602858

Syawie, M. H., Arifin, H. S., and Suharnoto, D. Y. (2023). Strategi Pengelolaan Lanskap Berkelanjutan di Danau Lido Cigombong, Bogor. Jurnal Lanskap Indonesia 15, 12–26. doi: 10.29244/jli.v15i2.42782

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Venus, A., Intyaswati, D., Ayuningtyas, F., and Lestari, P. (2025). Political participation in the digital age: impact of influencers and advertising on generation Z. Cogent Arts Humanit. 12:2520063. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2025.2520063

Wertheim, W. F. (1974). Sociology in Indonesia: A textbook in theory, problems, and history. Jakarta: Pustaka Jaya.

Wiryono, D. (2010). Jejak Perjuangan Pemuda dalam Perang Konvoi Sukabumi. Sukabumi: Balai Kajian Sejarah Sukabumi.

Keywords: local history, local patriotism, collective memory, rural youth activism, rural capitalism, Cigombong

Citation: Gandi R, Kolopaking LM, Damanhuri DS and Sjaf S (2025) Reimagined history and local patriotism: rural youth activism in Cigombong, Indonesia. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1678305. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1678305

Edited by:

Obasesam Okoi, University of St. Thomas, United StatesReviewed by:

Puspita Wulandari, Indonesia University of Education, IndonesiaTamara Soukotta, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2025 Gandi, Kolopaking, Damanhuri and Sjaf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sofyan Sjaf, c29meWFuc2phZkBhcHBzLmlwYi5hYy5pZA==

Rajib Gandi

Rajib Gandi Lala M. Kolopaking2

Lala M. Kolopaking2 Sofyan Sjaf

Sofyan Sjaf