- 1School of Law and Public Policy, Narxoz University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 2Faculty of International Relations, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

Introduction: This study examines how the government of Kazakhstan uses national surveys and real-time sentiment analysis through social media monitoring to better understand public opinion and incorporate it into political decision-making. The increasing use of digital tools for governance creates new opportunities for responsiveness but also raises concerns about transparency and democratic accountability.

Methods: A mixed-methods approach was employed, analyzing data from 2020 to 2024 using descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation to assess the relationship between technology adoption and policy responsiveness. In total, 72 policy decisions and 27 expert survey responses were examined to determine how digital technologies affect the timeliness and adaptability of state responses. The analysis covered 72 policy episodes with an average participation rate of 42 percent among relevant officials.

Results: The findings indicate that traditional polling remains institutionally dominant; however, newer tools such as social media analytics and SMS polling are increasingly used for rapid feedback at the executive level. A strong positive relationship was identified between the use of sentiment analysis and the reduction of policy lag time, showing that digital technologies enhance governmental responsiveness.

Discussion: The study contributes to the body of knowledge on data-informed governance by empirically linking technological adoption with the timing of political action. While digital opinion tools improve policy responsiveness, they also present a double-edged challenge, serving both as instruments of administrative innovation and as potential tools of political control.

1 Introduction

In the last twenty years, digital technology has transformed the relationship between citizens and the state (Xiong et al., 2024). Recent developments in data science, artificial intelligence (AI), and information and communication technologies (ICTs) are allowing governments to systematically monitor, analyze and sometimes predict public opinion on unprecedented scales and at historically unprecedented speeds (Verma, 2022). At present, public opinion monitoring technologies (POMTs) widely extend across various instruments, ranging from traditional tools like household surveys and public opinion polls to more recent innovations such as web-scraping bots, real-time sentiment analysis of social media and natural language processing (NLP) of online comments, e-petitions and forums (Brauner, 2024). The incorporation of these technologies into the processes of governmental decision-making would constitute the transition at governmental level from reactive to anticipatory governance, where the policies can be appropriately designed in advance under specific public analogy and socio-political emotion (Zhang et al., 2023).

Implementation of state governance is always a priority (Jafarova, 2025) and every nation is trying to adopt innovative technologies and techniques to attain its objectives (Kalmykov, 2023). On the global level, employment and management of POMTs are part of the wider patterns of digital governance (Vigoda-Gadot and Mizrahi, 2024). In liberal democracies, such technologies are normally used to foster participatory democracy, greater transparency and accountability, as well as evidence-based decision making (Asimakopoulos et al., 2025). For example, in the UK, platforms like “GOV.UK Verify” have allowed citizens to interact with public services, while contributing data that is used to inform policy (Stalla-Bourdillon et al., 2018). Similarly, the European Union is financing a range of digital governance projects which draw on input from members of the public, gathered through digital consultations and social listening tools. In the U. S., systems such as “We the People” and the inclusion of sentiment analysis into the dashboards of local governments illustrate how digital data is harnessed to measure citizen grievances and simplify bureaucratic response (Galston and Galston, 1994). POMTs are part of the monolithic state architectures of states such as China, Russia, Turkey and increasingly also the central Asian countries including Kazakhstan (Knox and Kurmanov, 2024; Roberts and Oosterom, 2024). Instead of just serving participatory purposes, these tools download dissent, control the narrative, manage political legitimacy, and fine-tune the instruments of soft repression (Gurol, 2023). They also allow governments to responsive to the public and not lose completely their top-down control, helping maintain a “networked authoritarianism” (Xu, 2021; Hoffman, 2022). Kazakhstan is best understood as a soft-authoritarian/hybrid regime that combines formal democratic institutions with extensive executive control and managed political competition. This characterization is normally framed as competitive or soft authoritarianism in the literature. It captures the country’s emphasis on elite stability, controlled plurality and image-making alongside selective institutional reform (Leviczkij and Vej, 2018). Since the beginning of the 2010s, Kazakhstan has heavily invested in e-government infrastructure as part of the “Digital Kazakhstan” program which works towards the modernization of state governance through digital technologies, data science and ICTs. Since 2019 the Tokayev administration has advanced a rhetoric and program of becoming a “Listening State.” The focus is to promote digital feedback mechanisms and formal public dialogue as part of governance reforms. Scholarship caution that these reforms are double-edged. They can institutionalize citizen feedback while simultaneously producing managed participation that preserves elite control (scholarly discussions of Kazakhstan’s listening-state reforms and critical assessments are emerging). For a compact conceptualization of the Listening State and recent critical appraisals, see official program documents and analyses (Tokayev’s addresses and government roadmaps) and critical assessments in the academic and policy literature (Tokayev, 2023). These initiatives have improved service delivery while constructing extensive feedback-tracking systems. But how these technologies work in practice and what their political effects are, however, remain less known or at least less known than the corresponding cases of China and Russia. Unlike those countries, Kazakhstan maintains a veneer of pluralism and frequently invokes the rhetoric of citizen-centered policy. It is well worth asking then: is it really public opinion technologies that drive political decisions in Kazakhstan or are they simply tools of legitimacy management in a restricted political environment?

The term Policy simulation refers to the symbolic enactment of responsiveness without substantive change in the digital whitewash describes the use of transparency rhetoric to obscure centralized control. And the Networked authoritarianism (MacKinnon, 2011) captures how regimes integrate digital participation tools into authoritarian governance without relinquishing control. But these do not necessarily result in a deepening of democracy. A public opinion monitoring exercise that is not transparent and open to citizens runs the risk of turning into a means for ‘policy simulation’ rather than for authentic responsiveness (Asimakopoulos et al., 2025). In other words, governments can always simulate the effect of acting on data while still employing centralized decision-making. In Kazakhstan, which has restricted political opposition and a constrained press, the centralization of digital monitoring systems is causing questions over who has control over data, which can see it and how it is used. Even more problematically, if these bases of data appear to be selectively made open, manipulated or read through political lenses, such an approach may deepen, rather than ameliorate problems of public trust, estrangement and the legitimacy of governance. As such, unpacking the practices of POMTs in Kazakhstan is necessary to understand if large scale movement towards data driven governance a genuine transition from bureaucracy to participatory policy process or a digital whitewash of centralized power is.

The relevance of this study is multi-dimensional. Exploring that how Kazakhstani state employs public opinion data in the policy process is important for evaluating the effectiveness, openness and inclusiveness of the policy process. Many cases in Kazakhstan are seen in which digital feedback channels have resulted in tangible changes. Those are urban infrastructure revisions based on public surveys or the redesign of public transportation routes following social media complaints (Atakhanova and Baigaliyeva, 2025). During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital dashboards and public feedback mechanisms were reportedly used by the Ministry of Healthcare to adjust quarantine rules and manage resource allocation (Tang et al., 2024).

Notwithstanding enhanced scholarly curiosity in digital governance and authoritarian stability, there are significant lacunae in the empirical and theoretical understanding in relation to the workings of public opinion monitoring technologies in hybrid political systems such as Kazakhstan. The existing literature remains fragmented. One line of research concentrates on technical affordances of e-government systems such as technical infrastructure, service delivery models and provision of access (Umbach and Tkalec, 2022). One, rather political, is focused on digital authoritarianism, often via a set of more detailed examples like China, Russia or Iran (Bashirov et al., 2025). Yet these two literatures rarely connect. Additionally, very few works offer an in-depth analysis of how exactly public opinion data impacts political decision-making. Little is known, however, about the specific bureaucratic mechanisms by which such data is gathered, processed, interpreted and utilized by policymakers. Even less is known about how specific technologies (e.g., online surveys or social media metrics) differ in their political utility or symbolic value. In the case of Kazakhstan, a great deal of the academic literature has naturally taken as its subject matter broader governance challenges, elite persistence, state-society relations and the repression of civil society, without engaging in the systematic study of how technologies are mediating these processes. This study aims to fill this gap by presenting an integrated analysis of the technological aspects of public opinion monitoring as well as of the political relevance of it. The purpose of this study is to provide a critical analysis of the nexus between the application of public opinion tracking technologies and the quality of political decisions in Kazakhstan. This study provides a way to identify what technologies are, in fact used, how their introduction is affecting decision-making within states, and whether their use affects more responsive or efficient or legitimate government.

The current work adds in the related theory in three ways. First, it bridges technical and political strands of digital governance via showing how data infrastructures become instruments of both administrative efficiency and political control. Second, it refines the concept of networked authoritarianism by illustrating how hybrid regimes use POMTs to simulate responsiveness while preserving centralized authority. Third, it contributes to the literature on data politics by revealing how algorithmic feedback mechanisms mediate legitimacy in constrained political environments. So the main objective of this stud is to explore the role of POMTs. It mainly considers the social media sentiment analysis with relation to the timing of executive policy responses in Kazakhstan between 2020 and 2024. Focusing the objective of the study on timing (policy lag) and the role of sentiment analytics narrows the empirical scope and allows a tighter methodological fit between the data and inference.

This study focuses on one central question:

RQ: How does the intensity of POMTs use affect the speed of government decision-making in Kazakhstan?

To support this inquiry, two sub-questions guide the analysis:

RQa: Which types of POMTs, surveys, SMS polls, or social media analytics, are most frequently used across policy domains?

RQb: To what extent do these technologies contribute to data-responsive governance within a hybrid political system?

This work goes beyond just descriptive accounts of digital governance and explores how data, technology and political behavior intersect within state institutions. It is intended to examine that how public opinion technologies are used also why and by whom they are deployed, and to what political purpose. For the purpose this study uses government documents, ministerial reports, digital projects and open data sources and analyzes Kazakhstan’s system of opinion monitoring and situates it within global patterns of digital governance. The research contributes to debates on data politics, digital control and transparency in hybrid regimes for the time from 2020 to 2024.

The article is organized as follows: A review of the literature is presented in Section 2 where the research gap is identified. Section 3 describes the methodology, specifically research design, data sources, and empirical analysis. Section 4 presents descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results. Discussions are given in Section 5. Then, the study is concluded in Section 6 by presenting the policy implications and areas for future research. Finally, the Appendix details the data collection information and expert survey instrument of the study.

2 Literature review

2.1 Global applications of public opinion monitoring technologies

POMTs have become pervasive tools in contemporary governance. They have applications spanning traditional surveys, sentiment analysis from social media and real-time big-data systems driven by machine learning (ML). Works by Abitbol and Morales (2021) and Sittar et al. (2022) demonstrated how Twitter sentiment correlates with socio-economic phenomena that include public health and election outcomes. Subsequent large-scale studies showed that Twitter-based sentiment analysis can predict presidential approval ratings and consumer sentiment ahead of conventional polling (Alvi et al., 2023). Comprehensive reviews of ‘social opinion mining’ emphasize the shift from structured querying to capturing vast, unsolicited public discourse online (Biswas and Poornalatha, 2023; Lock et al., 2025). In democratic contexts, these technologies facilitate citizen engagement and evidence-based policy. For instance, the UK’s Gov.uk Verify and EU online consultations integrate input from surveys and social listening to tailor policy interventions (Jarvie and Renaud, 2024). Also large-scale initiatives in the US have similarly used sentiment analysis for improving local governance dashboards (Lee and Dourish, 2024; Khmara and Touchton, 2024). POMTs take on distinct political roles with respect to the authoritarian or hybrid systems. In China, centralized monitoring of social media is used to preempt dissent, steer public narratives and reinforce regime legitimacy (Gallagher and Miller, 2021; Gardner, 2024). Russia operates Internet Monitoring Centers to supervise online discourse through government-contracted platforms (Jansen et al., 2023). Kazakhstan has also built digital systems to monitor public sentiment (Sairambay et al., 2024). Comparative studies noted how these systems blur the line between governance and state control (Verma, 2022). In this regard comparisons with China and Russia are instructive but approach regarding Kazakhstan must also be understood within the broader post-Soviet and Central Asian digital governance context. Studies by Knox and Kurmanov (2024) and Makulbayeva and Sharipova (2024) show that Central Asian states are developing digital infrastructures that blend modernization goals with regime preservation. This is clearly illustrating regionally specific trajectories of “controlled innovation.

2.2 Public opinion technologies in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan’s e-government portal named as eGov.kz, was launched in 2012. It now delivers over 580 electronic services to around 70% of the population and showing early adoption success1. Beyond service delivery, monitoring tools like OMSystem and Alem Media Monitoring have specifically targeted political and socio-economic discourse by applying ML algorithms to sentiment analysis of Kazakh and Russian language data. A study on OMSystem reported high model accuracy (95–99%) and its ability to track vaccination debates in Almaty and Nur-Sultan, demonstrating real-time utility during the COVID-19 crisis (Karyukin et al., 2022). Furthermore, academic research on Kazakhstani digital and public engagement is emerging. Makulbayeva and Sharipova (2024) critique the efficacy of public councils in Kazakhstan, emphasizing the limited autonomy of citizen engagement mechanisms. Ceron et al. (2024) explored crisis-driven polarization on social media, showed that the platform’s role in shaping public trust during emergencies. Meanwhile, research on electoral sentiment mining during the 2019 and 2022 presidential elections by Sairambay (2023) indicated increasing use of online comments to gauge and influence public opinion by the governments. Research in Central Asia like Knox and Kurmanov (2024) and Sairambay (2023) show that the digital monitoring in the region reflects a dual imperative. It can improve administrative responsiveness and can also reinforce elite stability.

2.3 Theoretical approaches to data-driven governance and public opinion

The current study is based on synthesis of public opinion theory, data-driven governance and concepts of authoritarian resilience. It can be related to the traditional public opinion theory of Page and Shapiro (1983) and Stimson (2018). Those were of views opinion tracking as essential for responsive policymaking in democratic contexts. However, in hybrid or authoritarian systems in which institutional channels for accountability are weak, public opinion technologies often serve a different function, shaping discourse boundaries rather than enabling participatory governance. Classical public opinion scholars see opinion tracking as a mechanism of democratic responsiveness. They consider it as a mean by which policy aligns with public preferences (Page and Shapiro, 1983; Stimson, 2018). But these democratic assumptions cannot be transferred uncritically to hybrid regimes where feedback may be selectively used or instrumentalized (MacKinnon, 2011). Theories of data-driven governance conceptualized data not as a democratic input but as a strategic resource. That allows the state to manage complexity and consolidate technocratic control.

There are further theoretical bases related to the stated theme. Anticipatory governance denotes the use of predictive analytics to proactively manage emerging social or political risks (Zhang et al., 2023). Digital authoritarianism describes the use of digital tools for surveillance, control, and regime legitimation (Roberts and Oosterom, 2024). POMTs encompass any state-employed digital or traditional instruments used to collect, analyze, or simulate citizen sentiment. Networked authoritarianism describes a strategy by which authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes co-opt digital networks and platform infrastructures to monitor, shape, and limit public discourse while preserving the appearance of connectivity and participation. The concept introduced and developed in the literature on China and subsequently applied comparatively. It highlights techniques such as social listening, platform regulation, algorithmic amplification/suppression, and state-contracted analytics firms. This paper uses networked authoritarianism as an analytic lens to examine how POMTs can be instruments of both responsiveness and control. The state uses digital feedback tools not to democratize decision-making but to reinforce regime stability in authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes like Kazakhstan. Also theories of MacKinnon and Robert, help explain how public opinion monitoring can be instrumentalized for narrative control.

This study is intended to provide an integrative view to link technical affordances of POMTs with their political functions. This allows examination the role of technological infrastructures in constrain governance dynamics and in hybrid regimes like Kazakhstan.

2.4 Research gaps identified

Recent research is very much inclined towards the role of digitization and POMTs in influenicnh public opinion. But the same is scarcely explored for the economy of Kazakhstan. Limited reserch is available that consider the circumstances these technologies influence substantive policy outcomes. In the hybrid regimes with limited accountability, studies seldom trace the links between public sentiment and political action or examine the institutional processes through which opinion data is managed and applied. The platforms like OMSystem are described in official sources but little is known about how the collected data circulates within state institutions or informs decisions. This study is intended to address these gaps and put forward a comprehensive examination regarding the use of POMTs in policy process of Kazakhstan.

Moreover, this study contributes to theories of digital and networked authoritarianism via introducing the notion of data-responsive authoritarianism. This is taken as a sub-type of governance where digital monitoring tools create an appearance of responsiveness without redistributing power. The framework via synthesizing insights from political science and information systems connects technical mechanisms of data processing with political objectives of control and legitimacy. This integration moves beyond descriptive accounts to explain how hybrid regimes use digital feedback to calibrate, rather than democratize, state responsiveness.

Addressing these gaps contributes to debates on authoritarian resilience by revealing how responsiveness is operationalized in hybrid regimes through data infrastructures, thus challenging the assumption that digital participation mechanisms inherently democratize governance.

3 Methodology

The current study uses a mixed method research design combining the descriptive and correlational methods with a purpose to explore how POMTs contribute to the political decision-making in Kazakhstan. The descriptive portion is intended to identify what types and to what extent of POMTs the state uses to make policy while the correlational portion explores the relationship between the use of such technologies and the type and velocity of policy decision-making from 2020 to 2024 time period.

3.1 Research design

This study uses a mixed-methods sequential design. First, a descriptive mapping of POMTs (qualitative/document review + expert survey) establishes institutional actors and technologies in use. Second, to examine the relationship between digital monitoring and policy timing, the study uses quantitative time-to-event measures (policy lag, in days) and event counts (numbers of sentiment monitoring deployments, surveys, SMS polling instances) aggregated at the policy-episode level. Correlational analysis is used as an exploratory test of association; given the time-to-event nature of the primary dependent variable (policy lag), the manuscript recommends supplementary survival-analysis models (e.g., Cox proportional hazards) or regression models (logistic / linear depending on outcome) in future revisions to examine robustness and handle censored observations.

3.2 Data details

Two major types of data are utilized in the study. First descriptive data is used. These figures are obtained from official Kazakhstani government websites (including the Ministry of Information and Social Development and the Astana Civil Service Hub). Use of the technology is reported in the public record, policy briefings and annual governance summaries. Additional information is taken from institutions such as the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies (KazISS), which regularly carries out and releases public opinion polls and their analysis. Information about social media analytics tools in use, such as Brand Analytics or Crimson Hexagon, is examined via government procurement databases and news articles. Also this study utilizes correlational data. This data is taken from data sets available publicly and accessible, consisting of national laws, presidential decrees and ministerial regulations that passed from 2020 to 2024, obtained from the government’s legislative tracking portals and official bulletins. Sampling of policy documents followed purposive criteria, selecting decisions that (i) were issued between 2020–2024, (ii) addressed socio-political concerns visible in public monitoring datasets, and (iii) were traceable to official public feedback mechanisms. Coding was performed using a binary classification (0 = no POMT reference; 1 = POMT referenced) to quantify technology presence in policy texts.

3.3 Operational definitions and coding

• Policy lag (dependent variable): number of days between the first identifiable public signal of concern (date of social media spike, SMS poll, or publication of a relevant survey) and the date of a government response (official decree, amendment, executive order, or public statement).

• Response type (dependent variable): coded as 0 = symbolic (minor announcements, statements, or nonbinding measures) or 1 = substantive (legally binding measures, budgetary allocations, or operational reforms). Coding rules and examples are provided in Table A2.

• Independent variables: quarterly counts of (a) sentiment analysis deployments, (b) social media monitoring events, (c) SMS polling events, and (d) number of national surveys cited.

• Control variables: issue area (health, infrastructure, security, economic), crisis flag (1 if the episode occurs during a major crisis such as COVID-19 or January 2022 unrest), and institutional owner (local vs. central).

• Data provenance: all datasets, platforms, and expert sampling procedures are summarized in Table A1, while the complete list of 72 coded policy episodes is presented in Table A2 to ensure reproducibility.

3.4 Data sources and expert selection

Table 1 summarizes the main data sources used in the study for both descriptive and correlational analyses. Expert participants were purposively selected based on (i) direct involvement in public opinion monitoring or policy analytics within ministries, (ii) authorship of at least one policy report on digital governance, or (iii) employment in state-affiliated research centers. Of the 35 experts invited, 27 completed the survey (response rate = 77%). This ensured institutional diversity and practical familiarity with opinion-data utilization. All government data sources were publicly available through official portals (e.g., egov.kz, legalacts.egov.kz). Pearson’s correlation was used as an initial measure of linear association across aggregated. It is normally distributed event counts and policy lag measures. The present exploratory study therefore reports Pearson’s r but flags the need for multivariate and time-to-event models as next steps. Detailed information on all data sources, access methods, and sampling procedures is provided in Table A1, while the complete list of the 72 policy episodes included in the correlation analysis is presented in Table A2.

The sample is limited to the Republic of Kazakhstan and covers a five-year period (2020–2024). This is a timeframe marked by considerable digital transformation in governance, political transition and heightened civil engagement via online platforms. The focus on government agencies, state-affiliated research bodies and ministries ensures that the findings remain policy-relevant and institutionally grounded. Detail is provided in Supplementary Material. Possible biases include selective publication of state data and algorithmic opacity of sentiment tools. To mitigate these, cross-verification was conducted using independent datasets and expert triangulation from non-governmental analysts.

3.5 Empirical analysis

Analysis employs a two-mode analysis strategy. The input data was first analyzed descriptively. All descriptive findings were coded and processed in Microsoft Excel and Python. The rates of technology use were described and quantified in frequencies and percentages. For example, the quantities of government policies that include to survey results or sentiment dashboards were counted and the proportion of ministries using each type of technology was calculated. It is worthwhile for its conciseness, simplicity, clarity and easy to understand and the visualization of the results. Correlation analysis was also carried out. As for analysis to explore the correlation between monitoring tools and decision-making patterns, Pearson correlation coefficient in SPSS, and scipy in Python were used. Regression or multivariate models were not employed because the available sample (72 policy cases × 5 years) and categorical outcome structure did not satisfy model-assumption requirements, and the aim of this work was exploratory correlation rather than causal inference. Covariates for public opinion monitoring were applied in all countries as the number of surveys in a quarter and the number of reports for sentiment analysis for social media monitoring or content of social media during a specified period. Dependent variables were time to adopt a policy (in the number of days from emergence of public concern to official action) and kind of policy (symbolic vs. substantive). Pearson’s method was selected because it is insensitive to non-linear associations, even in moderately-sized samples with normally distributed variables. Independent variables included the number of surveys, sentiment analyses and social media monitoring events per quarter. Dependent variables were policy lag time (days between public concern and government action) and response type (symbolic vs. substantive). Pearson’s correlation was used due to continuous, normally distributed data.

This mixed-method design combines descriptive and correlational analysis to link contextual understanding with inferential insight. Excel is used to present the data. SPSS is used for Pearson’s correlation and significance tests calculations. Python tools (pandas and scipy) are also utilized for additional data handling and visualization. This work also considers ethical standards. The survey responses were anonymized with informed consent and data from government portals and APIs were used in compliance with official policies. No personal information was collected. The purpose was to ensure both ethical integrity and methodological reliability in studying a politically sensitive setting. All social-media data were anonymized at the user-ID level before analysis. Only aggregate metrics (frequency of keywords or sentiment scores) were retained and no personally identifiable information was stored or reported. Data handling was fully complied with the institutional ethical review standards related to the theme of this study.

The study acknowledges potential biases that can arise from selective disclosure in government data and limited access to proprietary sentiment-analysis algorithms. For the reduction of these effects, multiple public portals were cross-checked and triangulation between documentary, statistical and expert data was applied. The correlation results are interpreted cautiously to reflect these structural constraints.

4 Results

The results of the current work are divided into parts. First the descriptive statistics summarize the types, frequency and extent of POMTs used by the Kazakhstani government during study period. The correlational analysis was conducted that assesses the statistical relationships between the use of these technologies and political decision-making outcomes. Of the 35 experts contacted for the semi-structured survey, 27 completed the questionnaire that yield a response rate of approximately 77%. The participants represented a diverse cross-section of institutions including ministries, policy research centers and digital monitoring agencies. This is done to ensure functional and institutional representativeness. The Shapiro–Wilk test was performed to assess normality brfore condcuting Pearson’s correlation analysis. The results indicated no significant deviation from normality so justifying the use of Pearson’s r. All correlation results were interpreted at a 95% confidence level with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Compared to Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan shows higher institutionalization of feedback mechanisms but less transparency regarding data interpretation. So this is reflecting its distinct hybrid model of digital governance.

4.1 Descriptive outcomes

The data collected indicate that the Kazakhstani government employed various technologies for monitoring public opinion. These include traditional opinion surveys, AI-powered sentiment analysis and social media monitoring tools.

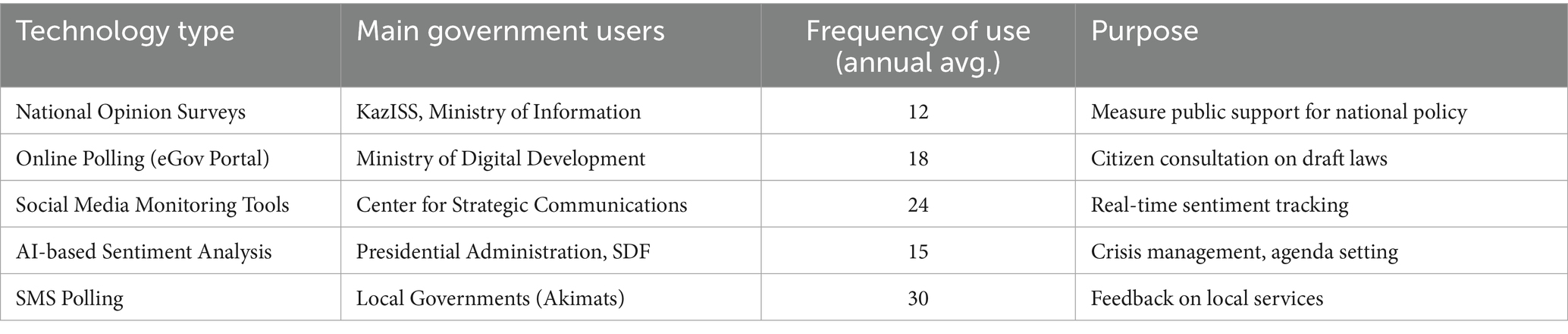

Table 2 reveals that SMS polling and social media monitoring were the most frequently used tools, largely due to their real-time and cost-effective nature. In contrast, traditional surveys remained important for nationally representative data collection, albeit less frequent.

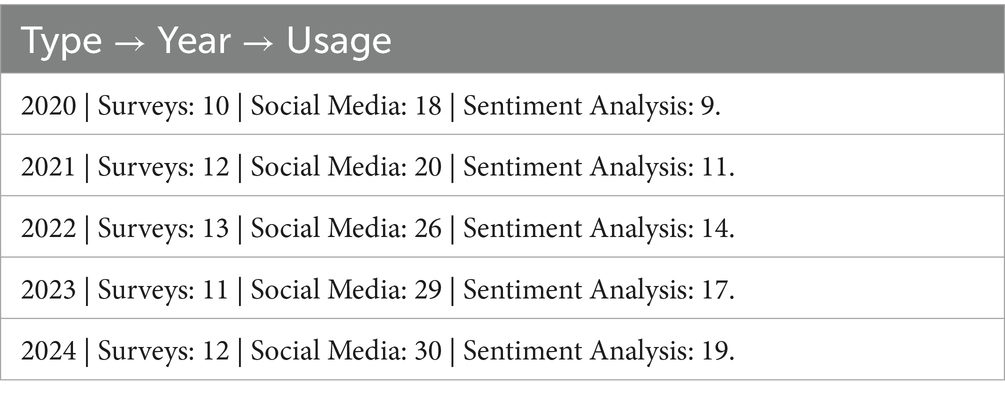

Table 3 documents a total of 189 recorded instances of public opinion monitoring over the five-year period.

Table 4 shows the chart that depicts that a consistent upward trend is visible in the use of social media monitoring and AI-based sentiment tools, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2022 political protests.

Figure 1 shows the annual frequency of public opinion monitoring technologies used by the government.

Figure 1. Frequency of public opinion monitoring technologies used by the government of Kazakhstan. This figure shows the use of four POMTs like surveys, SMS polls, social media tracking and sentiment analysis, over time. The data reveal steady growth in digital methods, especially sentiment analysis and social media monitoring, doubled between 2022 and 2024. Traditional surveys remain steady but are gradually being overtaken by faster, real-time digital platforms. Author’s compilation based on collected research data.

5 Correlational results

The second part of the analysis explored the relationship between the frequency of public opinion monitoring technology use and the speed and type of political decisions. Data on 72 policy decisions (laws passed, executive orders or regulatory changes) between 2020 and 2024 were analyzed against technology deployment timelines. Each policy episode involved between 18 and 46 participants across government departments. This gives average of 31 participants per episode (approximately 42% of the invited officials responded or contributed data).

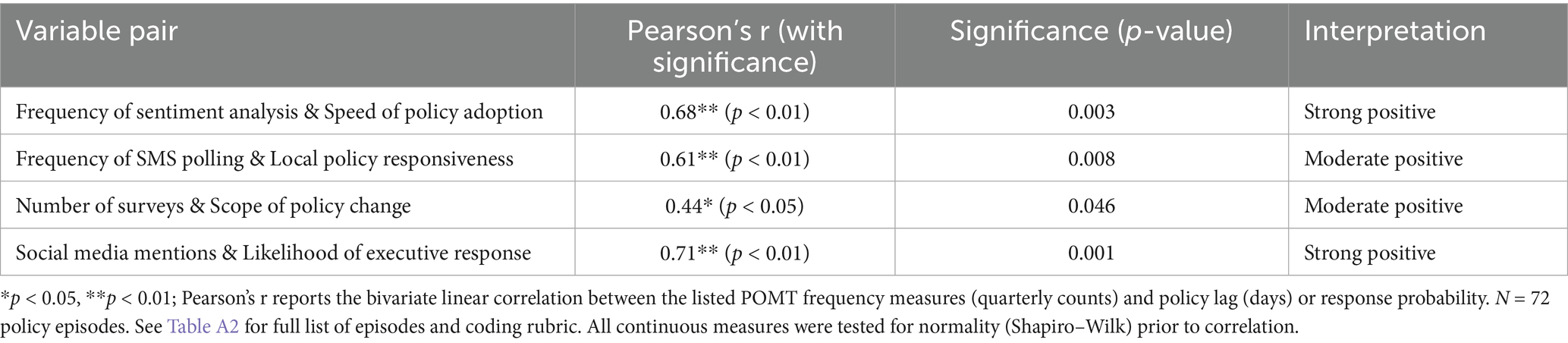

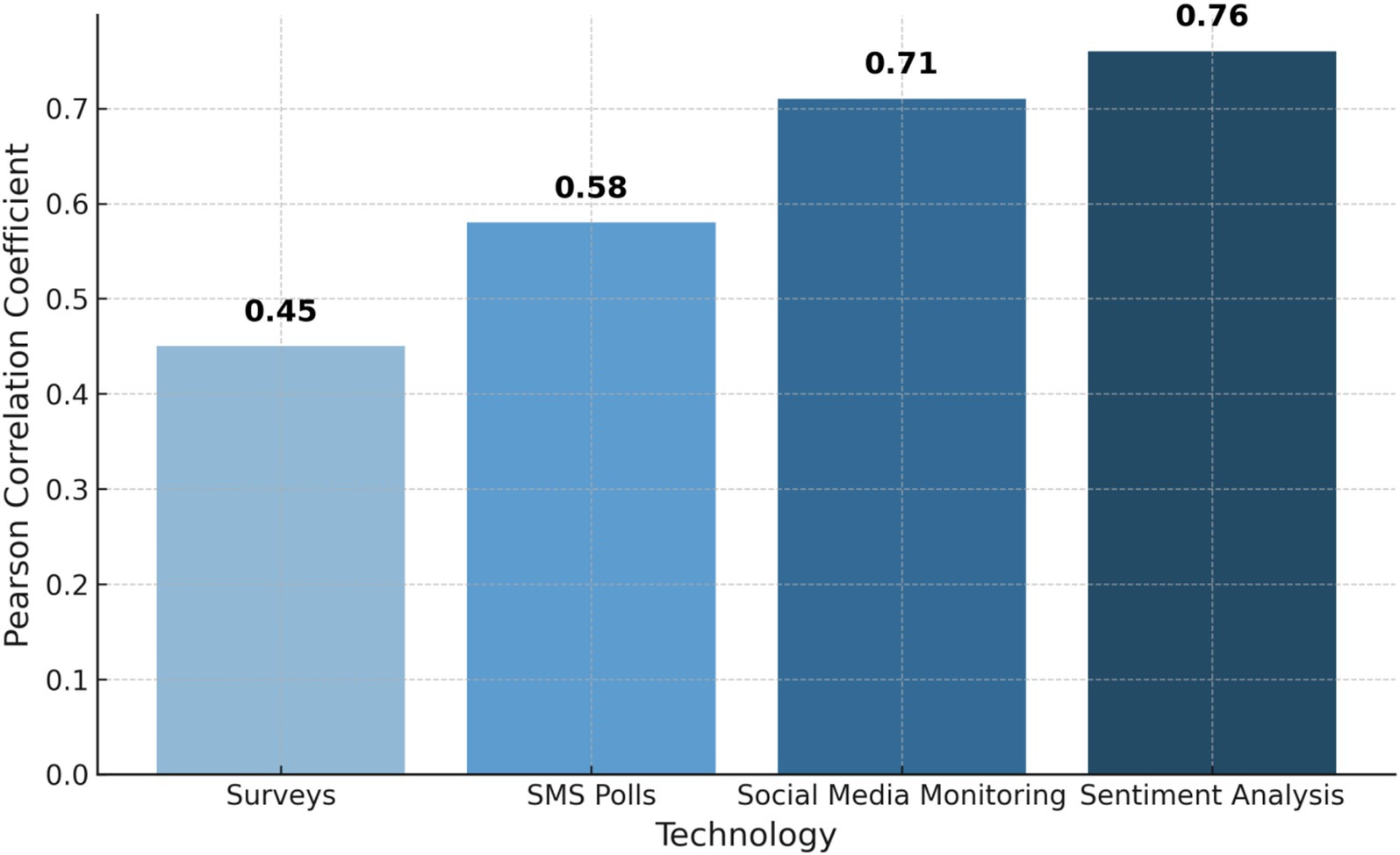

Table 5 presents the strength and direction of the correlations. The strongest relationship was found between the volume of social media monitoring and the likelihood of executive response (r = 0.71, p < 0.01). This suggests a high degree of policy responsiveness to online public discourse. A similarly strong positive correlation was identified between the use of sentiment analysis tools and reduced policy lag—defined as the time between public concern and official decision. The correlations suggest that digital sentiment data significantly inform executive responsiveness, especially in politically sensitive periods. But correlation does not imply causation so these results should be read as indicative of co-movement between digital engagement and governmental activity rather than direct influence.

The strength of correlations between digital tools and shorter decision lags suggests that real-time feedback mechanisms have begun to influence bureaucratic routines. This aligns with the hypothesis that technological affordances reinforce data-driven responsiveness within a managed political framework.

Table 6 reports bivariate associations only. Values indicate the direction and strength of linear association; they do not control for confounders. Table A2 lists the 72 policy episodes included in this analysis, together with justification for inclusion (policy relevance to public concern and traceable public feedback signals).

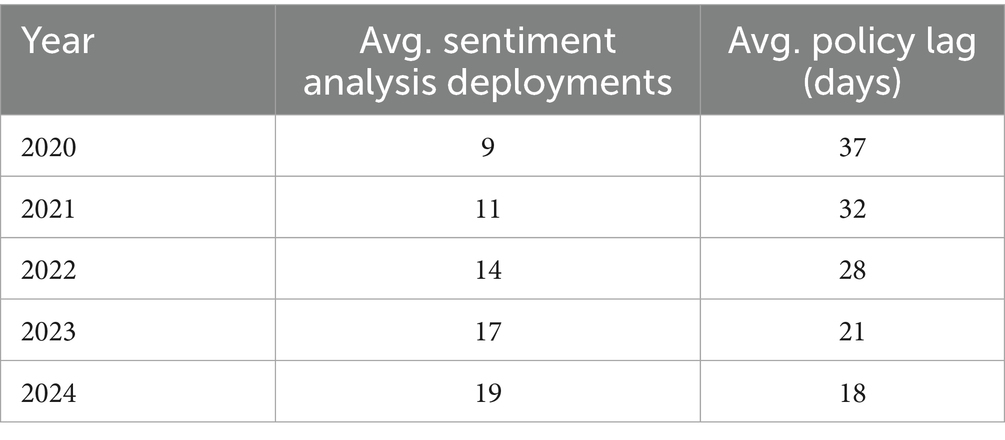

Table 6 indicates that a downward trend in policy lag time corresponds closely with increased use of sentiment analysis. This suggests a possible relationship between real-time opinion monitoring and policy agility.

Figure 2 shows the correlation between the use of monitoring technologies and policy responsiveness indicators.

Figure 2. Correlation between specific public opinion technologies and policy responsiveness in Kazakhstan. This figure presents the relationship between monitoring tools and policy responsiveness, measured via shorter decision-making times. Sentiment analysis and social media monitoring show strong positive correlations and surveys and SMS polling have moderate links. The results suggest that real-time digital tools play a key role in speeding up policy responses. Source: Author’s computation using Pearson correlation coefficients.

6 Discussion

The findings of the study provide much illumination into both the reciprocal dynamics of monitoring and technologized public opinion and political decision making in Kazakhstan. In the light of the descriptive and correlational results and within the methodological constraints, the findings are discussed in relation to the literature and positioned within general academic and practical perspectives. Both the traditional and digital monitoring tools show a pragmatic adjustment to changing political and technological realities in Kazakhstan. Survey data remain the most reliable source for informing policy, yet the growing use of SMS polls and social media monitoring indicates a shift toward faster and cheaper feedback methods. At the local level, Akimats increasingly rely on SMS polling to gather quick responses on public services, valuing its accessibility and ease of implementation. These findings define role of POMTs and also indicate how digital responsiveness functions as a mechanism of strategic adaptation within governance model of Kazakhstan. It suggested balancing legitimacy-seeking and controlling. The results refine networked authoritarianism by demonstrating that digital monitoring does not merely extend control. It also institutionalizes conditional responsiveness. Experience of Kazakhstan suggests a model of calibrated responsiveness in which digital tools allow the regime to adjust policy signals without broad political liberalization. Integrating the technical and political dimensions of digital governance, Kazakhstan exemplifies how infrastructural modernization (data collection, AI analytics) can coexist with restrictive information regimes. This shows that technological sophistication does not inherently lead to democratic accountability.

Also, the importance of AI-based sentiment analysis tools and of social media monitoring via public APIs is identified, with a noticeable growth for example, the COVID pandemic and the 2022 civil unrest. The outcomes indicate a dramatic growth in the use of sentiment analysis tools from year to year, and the trend being described corresponds with increasing political attention to popular sentiment, evidenced after expressions of political disaffection and policy pushback. The relationship between social media-based sentiment analysis and probability of executive action is particularly strong, thus digital sentiment has genuine influence on rapid executive actions. The same was found by Xu et al. (2022). The study demonstrated that for framing policy, as well as to responses to emergencies. In Kazakhstan’s instance, this responsiveness may be a reflection of building digital surveillance capacity and of policy makers learning that public discontent easily diffuses across the internet.

Likewise, the use of AI-powered sentiment analysis was closely related to shorter policy lag periods. Sentiment analysis has been utilized by other regimes (China, Singapore) to create feedback loops in real time that enable the bureaucratic response to be agile (Lian et al., 2024; Islam et al., 2024). In Kazakhstan, such tools seem to have double job descriptors, signaling political risk early and helping to shape policies that meet with consensual views. While less immediate, traditional surveys remain relevant for shaping long-term policy priorities. These results confirm prior findings that big data enhances responsiveness but consolidates executive control (Chen and Greitens, 2022; Zhongyuan et al., 2024). Relatedly, the country-specific data on Kazakhstan indicate the same. The tools most directly associated with quick decisions making are those controlled by central authorities, which is to say those employed by the Presidential Administration. Kazakhstan also showed commitment toward digital government reform, however, tend to ignore the crucial nexus between the use of technology and the realization of policy outcomes. Also this present study does not directly assess how freely citizens feel they can express their opinions or how satisfied they are with policy outcomes following government decisions. This can be considered in the future works. That can include attitudinal or survey-based measures to determine whether participation in digital feedback systems reflects genuine civic engagement or merely perceived compliance under constrained expressive conditions.

This study contributes to this gap by showing empirically how technologies correspond to intervention response and decision-making speed. However, the study does have some limitations. One limitation is the scarce availability of internal government data sets, such as the precise algorithms and models for sentiment analysis. This limits the comprehension of how raw public opinion is interpreted and turned into action. Moreover, survey data from policymakers may be subject to desirability bias, questions about surveillance and responsiveness is politically sensitive. Second, the assumption the present study makes that the more the technology is used, the more likely that decision making is based on it, can only be verified with correlation, and thus it does not confirm causality. This could be rectified in future research by making use of qualitative methods, such as interviews of policy staff that can show what internal logic might explain such decisions. The practical significance of the above findings is important for policy making, governance and public trust in the Republic of Kazakhstan as follows:

• Public opinion technologies should be institutionalized with clear rules on data transparency and ethical use.

• Local governments (Akimats) should be supported in using SMS and digital tools for citizen feedback with proper safeguards.

• National strategies must clarify how public sentiment data are interpreted and how they influence decisions.

• Policy-making should distinguish between tools used for feedback and those prone to surveillance misuse.

• Independent oversight bodies are needed to audit digital opinion-monitoring practices in hybrid regimes.

Normatively, current work raises critical questions about data ethics and participatory illusion in hybrid systems. As digital monitoring expands, distinguishing between genuine responsiveness and algorithmic manipulation becomes essential for sustaining public trust.

7 Conclusion

This study explored how Kazakhstan incorporates public opinion monitoring technologies—such as national surveys, SMS polling, and digital sentiment analysis—into its policy process. The results show that frequent use of these tools corresponds with shorter policy delays and a higher rate of executive response. This pattern indicates both improved bureaucratic responsiveness and a tightening of informational control.

From a theoretical standpoint, the research extends current debates on digital and networked authoritarianism by proposing the notion of data-responsive authoritarianism. In this mode of governance, technological feedback systems imitate democratic responsiveness while reinforcing regime legitimacy and stability. The Kazakhstani case illustrates how data analytics can serve administrative coordination and political containment at the same time, blending managerial efficiency with selective transparency.

Empirically, the findings suggest that digital feedback tools are now embedded in policy routines. Social media tracking and sentiment analysis are linked to faster governmental reactions, while conventional surveys remain important for long-term planning. Together, these trends mark a gradual move from rigid command structures toward a more calibrated, data-steered form of decision-making.

Public opinion monitoring has become an essential feature of Kazakhstan’s governance landscape. Although such instruments can promote transparency and improve service delivery, they also risk entrenching centralized authority if not balanced by independent oversight. Kazakhstan’s experience mirrors a broader regional pattern—seen also in Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan—where governments adopt digital participation mechanisms to project openness while maintaining firm political control.

Future inquiries could build on this work through longer-term and comparative designs that capture how data-based governance evolves within hybrid regimes. A longitudinal approach would help determine whether policies guided by online sentiment tools lead to durable social improvements or simply react to short-lived shifts in public mood. Legal and institutional studies are also needed to assess how Kazakhstan’s emerging regulatory frameworks address privacy, data ownership, and citizens’ rights as monitoring systems become more sophisticated. In addition, comparative analysis with states such as Uzbekistan, Georgia, and Singapore could clarify how different political and administrative settings shape the use and consequences of digital feedback mechanisms. This would clarify how political context shapes the use and effects of public opinion technologies. Also, qualitative research, including interviews with policymakers, technologists, and civil society actors, should explore how public sentiment data are interpreted, politicized, or instrumentalized during policymaking. Finally, future studies could address current limitations regarding restricted access to tone-classification algorithms and decision-making protocols by interviewing OMSystem developers and Presidential Administration officials to map data processing within the state apparatus.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by School of Law and Public Policy, Narxoz University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RU: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. KB: Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1680172/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Abitbol, J. L., and Morales, A. J. (2021). Socioeconomic patterns of twitter user activity. Entropy 23:780. doi: 10.3390/e23060780

Alvi, Q., Ali, S. F., Ahmed, S. B., Khan, N. A., Javed, M., and Nobanee, H. (2023). On the frontiers of twitter data and sentiment analysis in election prediction: a review. PeerJ Comput. Sci 9:e1517. doi: 10.7717/peerj-cs.1517

Asimakopoulos, G., Antonopoulou, H., Giotopoulos, K., and Halkiopoulos, C. (2025). Impact of information and communication technologies on democratic processes and citizen participation. Societies 15:40. doi: 10.3390/soc15020040

Atakhanova, Z., and Baigaliyeva, M. (2025). Kazakhstan’s infrastructure programs and urban sustainability analysis of Astana. Urban Sci. 9:100. doi: 10.3390/urbansci9040100

Bashirov, G., Akbarzadeh, S., Yilmaz, I., and Ahmed, Z. S. (2025). Diffusion of digital authoritarian practices in China’s neighbourhood: the cases of Iran and Pakistan. Democratization 22, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2025.2504588

Biswas, S., and Poornalatha, G. (2023). Opinion mining using multi-dimensional analysis. IEEE Access 11, 25906–25916. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3256521

Brauner, P. (2024). Mapping acceptance: micro scenarios as a dual-perspective approach for assessing public opinion and individual differences in technology perception. Front. Psychol. 15:1419564. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1419564

Ceron, A., Berloto, S., and Rosco, J. (2024). What are crises for? The effects on users’ engagement in the 2022 Italian election. PaG 12:8111. doi: 10.17645/pag.8111

Chen, H., and Greitens, S. C. (2022). Information capacity and social order: the local politics of information integration in China. Governance 35, 497–523. doi: 10.1111/gove.12592

Gallagher, M., and Miller, B. (2021). Who not what: the logic of China’s information control strategy. China Q. 248, 1011–1036. doi: 10.1017/S0305741021000345

Galston, M., and Galston, W. A. (1994). Reason, consent, and the U.S. constitution: Bruce Ackerman’s “we the people.”. Ethics 104, 446–466. doi: 10.1086/293624

Gardner, P. (2024). Information control and Communist Party legitimacy in China. Glasgow: University of Glasgow.

Gurol, J. (2023). The authoritarian narrator: China’s power projection and its reception in the Gulf. Int. Aff. 99, 687–705. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiac266

Hoffman, S. (2022). China’s tech-enhanced authoritarianism. J. Democr. 33, 76–89. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0019

Islam, M. M., Shahbaz, M., and Ahmed, F. (2024). Robot race in geopolitically risky environment: exploring the nexus between AI-powered tech industrial outputs and energy consumption in Singapore. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 205:123523. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123523

Jafarova, R. F. K. (2025). Implementation of state governance in the liberated territories as one of the manifestations of Azerbaijani constitutionalism. Futurity Economics & Law 5, 69–81. doi: 10.57125/FEL.2025.03.25.04

Jansen, B., Kadenko, N., Broeders, D., Van Eeten, M., Borgolte, K., and Fiebig, T. (2023). Pushing boundaries: an empirical view on the digital sovereignty of six governments in the midst of geopolitical tensions. Gov. Inf. Q. 40:101862. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2023.101862

Jarvie, C., and Renaud, K. (2024). Online age verification: government legislation, supplier Responsibilization, and public perceptions. Children 11:1068. doi: 10.3390/children11091068

Kalmykov, A. (2023). Innovative technologies for creating multilingual audio content in the publishing industry. Law, Bus. Sust. Herald 3, 72–87. Available online at: https://lbsherald.org/index.php/journal/article/view/70

Karyukin, V., Mutanov, G., Mamykova, Z., Nassimova, G., Torekul, S., Sundetova, Z., et al. (2022). On the development of an information system for monitoring user opinion and its role for the public. J. Big Data 9:110. doi: 10.1186/s40537-022-00660-w

Khmara, L., and Touchton, M. (2024). Institutional fragmentation in United States protected area agencies and its impact on budget processes. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 36, 490–513. doi: 10.1108/JPBAFM-08-2023-0147

Knox, C., and Kurmanov, B. (2024). Variegated digital state repression in Central Asia. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 31:12644. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12644

Lee, S., and Dourish, P. (2024). Reconfiguring data relations: institutional dynamics around data in local governance. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Int. 8, 1–28. doi: 10.1145/3686959

Leviczkij, S., and Vej, L. A. (2018). The rise of competitive authoritarianism. Emergency Store 21, 29–47.

Lian, Y., Tang, H., Xiang, M., and Dong, X. (2024). Public attitudes and sentiments toward ChatGPT in China: a text mining analysis based on social media. Technol. Soc. 76:102442. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102442

Lock, I., Hoffmann, L. B., Burgers, C., and Araujo, T. (2025). Types, methods, and evaluations of artificial intelligence (AI) in public communication research in the early phases of adoption: a systematic review. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 49, 122–145. doi: 10.1093/anncom/wlaf005

MacKinnon, R. (2011). Liberation technology: China’s “networked authoritarianism.”. J. Democr. 22, 32–46. doi: 10.1353/jod.2011.0033

Makulbayeva, G., and Sharipova, D. (2024). Social capital and performance of public councils in Kazakhstan. J. Eurasian Stud. 16:18793665241266260. doi: 10.1177/18793665241266260

Page, B. I., and Shapiro, R. Y. (1983). Effects of public opinion on policy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 77, 175–190. doi: 10.2307/1956018

Roberts, T., and Oosterom, M. (2024). Digital authoritarianism: a systematic literature review. Inf. Technol. Dev. 22, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/02681102.2024.2425352

Sairambay, Y. (2023). New media and political participation in Russia and Kazakhstan: Exploring the lived experiences of young people in Eurasia. London: Lexington Books.

Sairambay, Y., Kamza, A., Kap, Y., and Nurumov, B. (2024). Monitoring public electoral sentiment through online comments in the news media: a comparative study of the 2019 and 2022 presidential elections in Kazakhstan. Media Asia 51, 33–61. doi: 10.1080/01296612.2023.2229162

Sittar, A., Major, D., Mello, C., Mladenic, D., and Grobelnik, M. (2022). Political and economic patterns in COVID-19 news: from lockdown to vaccination. IEEE Access 10, 40036–40050. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3164692

Stalla-Bourdillon, S., Pearce, H., and Tsakalakis, N. (2018). The GDPR: a game changer for electronic identification schemes? The case study of gov.UK verify. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 34, 784–805. doi: 10.1016/j.clsr.2018.05.012

Stimson, J. A. (2018). Public opinion in America: Moods, cycles, and swings. 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Tang, F., Yang, W., Wu, W., Yao, Y., Yang, Y., Zheng, Q., et al. (2024). Comparative analysis of state-level policy responses in global health governance: a scoping review using COVID-19 as a case. PLoS One 19:e0313430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313430

Tokayev, K. J. (2023). State of the nation address to the people of Kazakhstan: Kazakhstan in the era of artificial intelligence—Current challenges and solutions through digital transformation. Akorda.Kz. Astana: Akorda (Office of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan). Available online at: https://www.akorda.kz/en/president-kassym-jomart-tokayevs-state-of-the-nation-address-to-the-people-of-kazakhstan-kazakhstan-in-the-era-of-artificial-intelligence-current-challenges-and-solutions-through-digital-transformation-1083029 (Accessed November 10, 2025).

Umbach, G., and Tkalec, I. (2022). Evaluating e-governance through e-government: practices and challenges of assessing the digitalisation of public governmental services. Eval. Program Plann. 93:102118. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2022.102118

Verma, S. (2022). Sentiment analysis of public services for smart society: literature review and future research directions. Gov. Inf. Q. 39:101708. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2022.101708

Vigoda-Gadot, E., and Mizrahi, S. (2024). The digital governance puzzle: towards integrative theory of humans, machines, and organizations in public management. Technol. Soc. 77:102530. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102530

Xiong, D., Khaddage-Soboh, N., Umar, M., Safi, A., and Norena-Chavez, D. (2024). Redefining entrepreneurship in the digital age: exploring the impact of technology and collaboration on ventures. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 20, 3255–3281. doi: 10.1007/s11365-024-00996-0

Xu, X. (2021). To repress or to co-opt? Authoritarian control in the age of digital surveillance. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 65, 309–325. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12514

Xu, Q. A., Chang, V., and Jayne, C. (2022). A systematic review of social media-based sentiment analysis: emerging trends and challenges. Decision Analytics J. 3:100073. doi: 10.1016/j.dajour.2022.100073

Zhang, Z., Lin, X., and Shan, S. (2023). Big data-assisted urban governance: an intelligent real-time monitoring and early warning system for public opinion in government hotline. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 144, 90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2023.03.004

Keywords: public opinion monitoring, Kazakhstan, data-driven governance, sentiment analysis, political decision-making, social media, policy responsiveness

Citation: Smailova A, Kuzembayeva A, Utkelbay R, Kukeyeva F and Baizakova K (2025) Public opinion monitoring technologies: how the state uses data to make political decisions. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1680172. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1680172

Edited by:

Charalampos Alexopoulos, University of the Aegean, GreeceReviewed by:

Isnaini Muallidin, Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta, IndonesiaBrooke Ackerly, Vanderbilt University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Smailova, Kuzembayeva, Utkelbay, Kukeyeva and Baizakova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Assiya Kuzembayeva, YXNpeWEua3V6ZW1iYXlldmFAZ21haWwuY29t; Rysbek Utkelbay, cnlzYmVrLnV0a2VsYmF5QG5hcnhvei5reg==

Aizhan Smailova

Aizhan Smailova Assiya Kuzembayeva

Assiya Kuzembayeva Rysbek Utkelbay

Rysbek Utkelbay Fatima Kukeyeva

Fatima Kukeyeva Kuralay Baizakova

Kuralay Baizakova