- 1Department of Political Science, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan City, Indonesia

- 2Department of Public Administration, Universitas Sriwijaya, Ogan Ilir, Indonesia

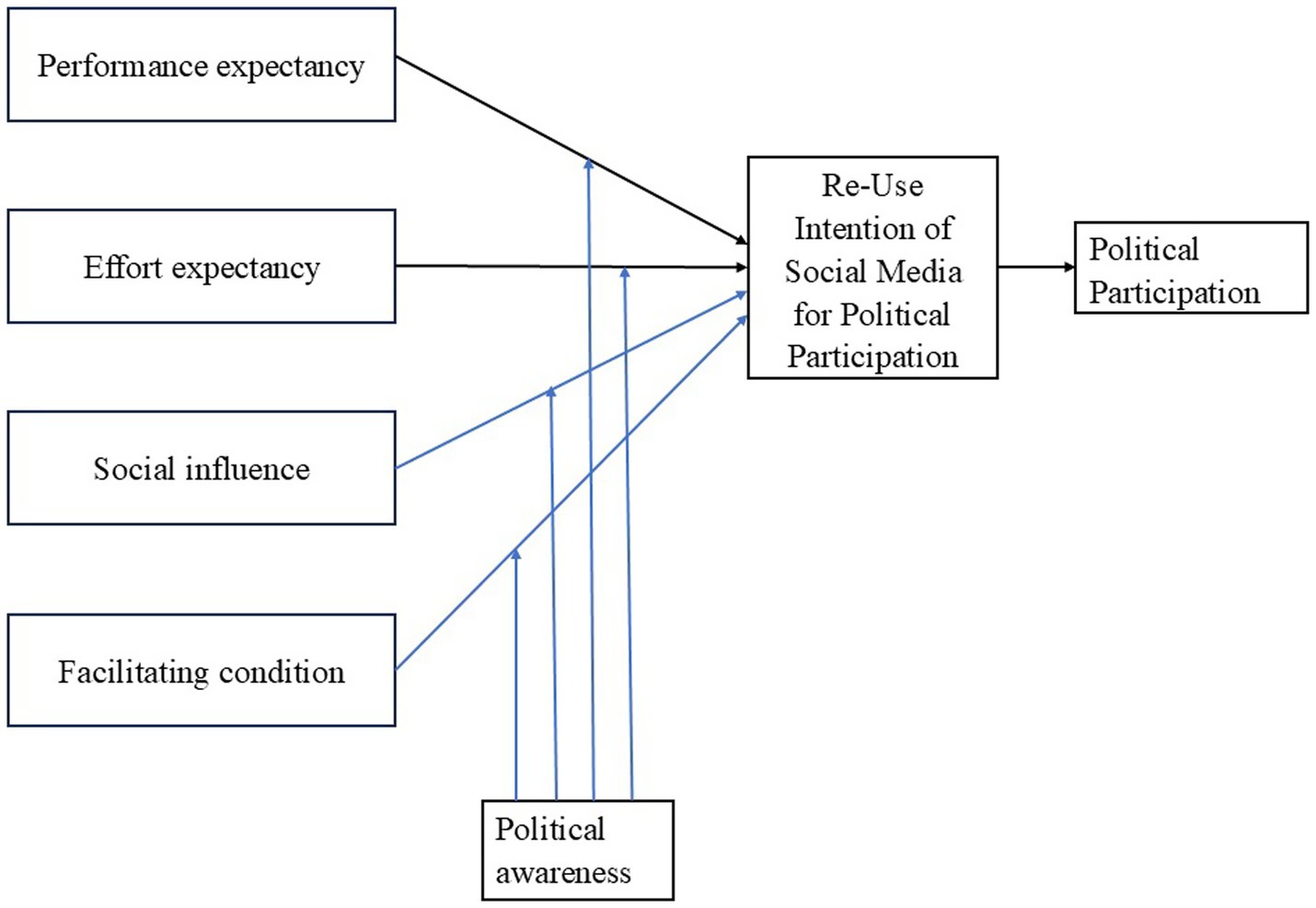

Introduction: This study investigates social media–based political participation among Generation Z in North Sumatra, a multicultural region representing Indonesia’s sociocultural diversity. The research integrates a modified UTAUT model with connective action theory to explain how technological factors shape political engagement in digital environments.

Methods: Data were collected from 500 university students and analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The model assesses the effects of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions on behavioral intention and actual political participation, with political awareness tested as a moderating variable.

Results: The findings show that behavioral intention significantly mediates the relationship between technological determinants and political participation. Political awareness strengthens or weakens these relationships, and higher levels of political awareness are associated with lower intention to use platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, and Facebook for political activities. The results also reveal the emergence of third spaces or hybrid activism that blend online and offline participation.

Discussion: These results demonstrate that social media enables flexible and decentralized political engagement while highlighting the complex role of civic awareness in shaping digital political behavior. The integrated framework advances the literature on digital politics by explaining how personalized political expression, technology use, and civic awareness interact to influence democratic participation in multicultural contexts.

1 Introduction

Digital technology has opened up a broader space for the study of digital politics, even evolving into a fundamental basis in political communication (Chadwick and Howard, 2009). Digital politics refers to the use of digital technology, particularly the Internet, for various political purposes, ranging from communication with voters to political campaigns and interactions with constituents (Berghel, 2016). This phenomenon has drawn attention from both academics and practitioners in politics, particularly digital politics in the realm of social media (Karatzogianni et al., 2023; Situmorang and Ritonga, 2025). In digital politics, digital technology serves not merely to support predetermined political goals but also creates new spaces for action that can alter structures and patterns of power (Coleman and Freelon, 2015). Digital politics enables greater transparency and interaction between politicians and the public but also brings challenges such as the potential misuse of information, privacy violations, and data manipulation.

One of the critical topics in digital politics is participation. Research on digital politics since the 1990s has shown that digital technology, especially social interaction platforms, creates opportunities for political participation (Koc-Michalska and Lillker, 2019). Political participation encompasses all activities of citizens aimed at influencing the selection of government and/or its actions (Finch, 1974). According to Milbrath and Goel (1977), political participation refers to citizens’ actions intended to influence or support the government and politics. Conversely, an increasing number of studies have conceptualized political participation by emphasizing activities that are exclusive to the digital realm, such as hashtag activism (Berg, 2017; Earl et al., 2013; Micó and Casero-Ripollés, 2013).

However, alongside the development of digital technology, the concept of participation in politics faces challenges. The development of newer and non-conventional forms of participation is necessary (Lu et al., 2023; Ohme et al., 2018). Previously, Van Deth (2014) highlighted the conceptual ambiguity in defining political participation. Some researchers adopt stricter definitions, leading to conclusions that political engagement is declining, while others use more inclusive definitions and observe a shift in forms of participation. This gap underscores the need for updated definitions and operationalization of political participation in digital spaces that systematically accommodate newer forms of engagement without excessively diverging from the fundamental concept of political participation. Citizen participation in politics has always been a hallmark of democracy (Hooghe, 2014).

On the other hand, political participation requires rational political awareness, as seen in Indonesia. Studies show an increase in the involvement of Generation Z in political participation within digital spaces. Gen Z, representing the largest demographic cohort, constitutes a strategically important group that requires a comprehensive understanding, particularly regarding their political learning processes, influencing factors, and engagement patterns that differ significantly from previous generations (Parmelee et al., 2022). As digital natives, Generation Z represents an emerging political force with a distinct perspective on power structures (McCargo, 2021). Gen Z is recognized for their active participation and concern for political issues, as well as their role as catalysts for collective action through digital technology (Deckman, 2024).

Data indicates that interactions in digital spaces are often filled with political discussions. However, these discussions can sometimes lead to hate speech, hoaxes, or forms of participation that threaten political engagement, such as intimidation, violence, or even attempts to silence dissenting voices in the digital public sphere. It is essential to cultivate awareness of participating in every political process as citizens with responsibilities toward their country. Political awareness must be fostered based on rationality, involving knowledge and informed decision-making. Political awareness, in the context of election campaigns, refers to the extent to which an individual pays attention to politics and understands the political information they receive (Claassen, 2011). Political awareness influences intentions and political participation.

However, awareness and participation in the public sphere are highly complex. A deeper understanding is required of how technology influences individual behavior in digital spaces for political participation. Individuals, shaped by unique backgrounds and experiences, often hold biases toward technology (Venkatesh, 2022). One conceptual framework that can be used to understand and predict behavior is the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). UTAUT serves as a conceptual framework for understanding technology adoption (Alam et al., 2020; Williams, 2021). However, studies on integrating the UTAUT model into digital spaces to understand individual behavior remain scarce. Contextual nuances and varying influences affect technology acceptance (Rouidi et al., 2022). Additionally, political participation is multidimensional, encompassing various activities within the digital public sphere or “digital agora,” where citizens can share opinions, build alliances, and collectively influence political processes (Koc-Michalska and Lillker, 2019). Although digital technology has become an integral part of political participation, research on understanding individual behavior, particularly among Generation Z, is still limited. Venkatesh (2022) emphasizes that research agendas related to technology should address diversity and individual characteristics across various contexts.

Generation Z, known as “Digital Natives” or the “iGeneration,” born between 1997 and 2012 (Turner, 2015), has grown up and interacted in a highly connected and digitized environment that shapes their behavior, preferences, and interactions (Szymkowiak et al., 2021). They possess high digital literacy and are more efficient in analyzing and evaluating information from various online sources (Livingstone and Third, 2017), including political information. They tend to use social media to share political views, stay informed about political developments, and engage in political discussions (Andersen et al., 2020; Amin and Ritonga, 2024). Generation Z holds significant potential for active participation through social media and other online platforms. However, they are also vulnerable to negative political information.

The UTAUT model can explain how individuals behave with technology. UTAUT, developed from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), is a widely used theoretical framework for understanding and predicting individual acceptance and adoption of new technology (Davis, 1985; Venkatesh et al., 2003). UTAUT includes several key constructs that influence the intention and behavior of technology use (Jain and Jain, 2022; Venkatesh, 2022). Although UTAUT is one of the most commonly used theories to explain adoption and use at the individual level (Tseng et al., 2022; Venkatesh, 2022). Its versatility allows researchers to explore various factors that can impact technology adoption, including individual differences, cultural influences, and system characteristics. Individual differences in technology adoption are a key factor enabling researchers to explore intention behavior in technological adoption.

Studies utilizing the UTAUT framework to understand political behavior in cyberspace are still limited, especially in explaining how technological factors specifically influence the political participation of Generation Z. Various social media platforms enable political participation as articulated by Lee et al. (2022), Theocharis et al. (2023), and Saud and Margono (2021). However, each social media platform possesses distinct functions and effects within the context of political participation, including TikTok as an “asymmetric” medium that allows users to follow accounts unilaterally (Durotoye et al., 2025). Digital platforms extend individual connections to actual participatory behavior in various interconnected and collaborative forms (Hansson et al., 2024; Showden et al., 2025). Kim and Kim (2025) affirm that social media fosters democratic connectivity and freedom of expression.

However, in the context of the digital realm in politics, it remains underexplored. Psychological aspects in UTAUT studies on social media remain underexplored (Lai and Beh, 2025; Naranjo-Zolotov et al., 2019), more specifically, political-psychological aspects (Huda and Amin, 2023). Theories about digital politics are often formed in response to social events that defy expectations or even appear contrary to traditional social patterns. Social events or phenomena that challenge existing assumptions or predictions (counter-intuitive social events) prompt researchers to reconsider or revise existing theories about how digital technology interacts with politics (Karpf, 2017). Although digital technology has opened new opportunities for political participation, understanding its long-term effects on political behavior in digital spaces requires further study, particularly regarding its influence on Generation Z and how digital technology can be positively utilized to enhance healthy and inclusive political engagement. There is a need to update the concept of political participation to encompass newer and more unconventional forms of participation. Additionally, the UTAUT and UTAUT2 models, which are widely used to understand technology adoption and usage, are still rarely integrated into research on political participation in digital spaces.

The research contribution expands the theory of digital politics, which often evolves through reflection on events that appear to challenge the logic of collective action or established political norms, as observed in the phenomenon of connective action within social media networks (Karatzogianni et al., 2023). This study contributes by explaining how Generation Z’s political participation through social media, supported by political awareness, can be understood within a theoretical framework. The researchers integrate the UTAUT model and the theory of connective action to explain political participation, where political expression increasingly becomes personal and is intensively mediated by digital technology (Bennett and Segerberg, 2009).

UTAUT is employed to explain technology acceptance at the individual level for political participation. However, to understand how the aggregation of individual participation can become flexibly coordinated digital political movements, connective action theory (CAT) is required. CAT theory is capable of explaining digital mobilization without formal organizational structures yet remains effective and sustainable, particularly in the context of online network utilization (Kasimov, 2025). CAT elucidates how online and offline elements interweave to form a third space termed hybrid activism (Showden et al., 2025). Online platforms expand reach, while offline interactions strengthen affective experiences and community proximity.

These two theories, each with its strengths in explaining individual behavior, when combined, provide a more comprehensive understanding of how technology, particularly social media, influences Generation Z’s engagement in political processes.

The research objectives are formulated based on the following research problems.

RQ1: How is the change in Generation Z's participation in politics based on behavioral according to A Modified UTAUT Model.

RQ2: Does political awareness moderate the determinants of behavioral intention for Generation Z.

2 Literature review and hypothesis

2.1 Connective action theory as a foundation

The theory of connective action was developed by social scientists to understand how technology has transformed the way we perceive and analyze social movements (Bennett and Segerberg, 2015);. This theory seeks to revise the traditional logic of collective action within the context of a digital era characterized by personal political expression and hyper-mediation. Lower costs enable the formation of action networks with ease, facilitated through action frames, which can be disseminated as media, symbols, or objects via communication technologies (Bennett and Segerberg, 2012). Connective action explains the movement from fluid digital participation toward offline collectivity (Bernroider et al., 2022; Showden et al., 2025). However, connective action pays less attention to the distinctions between various internet technologies, limiting its ability to account for how interactions between specific technologies and human users can shape political action (Pond and Lewis, 2017). Furthermore, although connective action can strengthen political participation, it also poses significant risks to democracy (Bennett and Livingston, 2025).

2.1.1 The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology in digital politic

“Performance expectancy (PE)” reflects an individual’s belief in the capability of a system to deliver benefits in achieving performance objectives (Venkatesh et al., 2016; Venkatesh et al., 2012; Jain and Jain, 2022; Tseng et al., 2022). Performance expectancy plays a crucial role in shaping individuals’ intentions to participate in politics. It is one of the key constructs considered in the UTAUT2 model to predict intentions and behaviors, including the intention to engage in political participation. In various contexts, the acceptance of the UTAUT2 model in predicting intentions is relatively high, with PE representing a form of confidence in the use of technology that will contribute to goal achievement (Kabra et al., 2017). Individuals who believe that technology will enhance their performance in the political context are more likely to be motivated to participate, ultimately influencing the dynamics of political participation within society.

Ha2: Performance expectancy has an influence on Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

Effort expectancy refers to the level of ease or comfort associated with using a particular technology system (Venkatesh et al., 2012; Kabakus et al., 2023; Tseng et al., 2022). Effort expectancy significantly influences the intention to participate in politics. When individuals perceive that using technology for political activities is easy and requires minimal effort, they are more likely to engage. EE is associated with how easily or difficultly users can interact effectively with technology, including ease of navigation, understanding functions, and clear interaction with the system. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Ha3: Effort expectancy has a significant influence on Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

Social influence also significantly impacts the intention to participate in politics (Harris et al., 2023; Dekoninck, 2022). Social pressure or support from surrounding individuals, the effort to align behavior with social norms within a group, and access to information from trusted sources shape political opinions and beliefs, thereby influencing the intention to engage in politics. Individuals tend to adopt political views that align with their social environment to feel accepted and become part of specific social groups, supporting actions and political views that resonate with their group’s identity. SI is reflected by the presence of influencers who enhance individual confidence in following the behavior of significant others in technology adoption for political participation (Harff and Schmuck, 2024). Based on this perspective, the hypothesis proposed is:

Ha4: Social influence has a significant influence on Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

Facilitating condition refers to the extent to which an individual believes that the necessary resources and technological support are available to enable usage (He and Li, 2019; Venkatesh, 2022; Venkatesh et al., 2012). Facilitating conditions can encourage political participation, encompassing access to information, political education, and necessary resources for effective engagement, such as transportation to polling stations or access to online platforms for participating in political discussions. Camilleri and Camilleri (2023) suggest that facilitating conditions reflect the extent to which individuals believe that technological resources are readily available to support their use.

Ha5: Facilitating conditions have an influence on Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

2.1.2 Political participation in the digital world

The concept of political participation has evolved with changing times. In traditional circles, political participation was often associated with active actions aimed at influencing government decisions. However, many scholars now agree that political participation does not necessarily have to manifest in overtly political acts such as protests. As previously stated, a substantial amount of research has utilized the notion of political participation to encompass non-traditional political activities, such as protests, and even various forms of civic engagement that may not be overtly political (Theocharis and Van Deth, 2017). Moreover, the concept of political participation has broadened with the emergence of the digital era (Carlisle and Patton, 2013; Fox, 2014). Gibson and Cantijoch (2013) contend that the Internet ‘expands the repertoire of participatory actions.

According to Ruess et al. (2021), some academics argue that online and offline forms of participation should be viewed as interchangeable. This perspective is common among those who adhere to the concepts of political participation from the pre-Internet era and those who are skeptical about the novelty and political quality of digital participation. As e-voting is not widely implemented in many countries, online political participation, in the strict sense of participating in political representative elections, is not feasible for practical reasons. Therefore, online and offline political participation are distinct (Ruess et al., 2021). Conversely, an increasing number of studies have conceptualized political participation by emphasizing activities that are exclusive to the digital realm, such as hashtag activism (Berg, 2017; Earl et al., 2013; Micó and Casero-Ripollés, 2013). Consequently, arguments are attempting to differentiate online and offline political participation conceptually (Gibson and Cantijoch, 2013). Social media has emerged as a political tool that enables individuals to actively participate in the political process and exert influence on political decisions (Chinedu-Okeke and Obi, 2016; Lawrence, 2023; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan, 2012).

Ha6: Political participation in the digital space is influenced by Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

The intention to participate in politics may not necessarily reflect political participation. Intention requires reinforcement through persuasive strategies and knowledge built through individual interaction with internet technologies such as social media (Kanagavel and Chandrasekaran, 2014). However, intention is an important predictor of behavior. Intention is generally defined as the tendency to perform a particular behavior. Intention serves as an input for potential behaviors that arise from positive affective responses. Acceptance of the role of technology, based on the specific differences between various platforms and digital tools, as well as generational factors, influences how users interact, form intentions, and engage in participation.

Ha7: Re-Use Intention of Social Media mediates the influence of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions on political participation.

2.1.3 Political awareness in digital politics

Political awareness refers to a genuine interest in the political domain and to following and understanding political events, respectively (Zagidullin et al., 2021). In the context of digital politics, political awareness refers to an individual’s understanding and attention to political issues related to digital technology, social media, and online information. Political awareness encourages individuals to feel that they must participate in politics. Political awareness is linked to electoral campaigns, where political awareness is defined as “the extent to which an individual pays attention to politics and understands what he or she has encountered” (Claassen, 2011). Political awareness influences how campaigns and strategies are conducted. This indicates that an individual’s political awareness is crucial in elections.

Political awareness determines the extent to which individuals accept political campaign messages and encourages more intensive interaction through social media, leading to the intention to participate. Political awareness can be specifically categorized into knowledge of electoral fraud (Reuter and Szakonyi, 2015), which encourages individuals to become more deeply involved through existing social media. Online social media can be an especially powerful tool for spreading information about electoral fraud. Social media serves as a platform for expressing political aspirations or viewpoints. Political awareness drives users’ engagement in expressing political opinions and their intention to participate in politics. Political awareness determines attitudes and intentions to use technology for political participation (Zagidullin et al., 2021; Figure 1).

Ha8: Political awareness moderates the influence of performance expectancy on Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

Ha9: Political awareness moderates the influence of effort expectancy on Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

Ha10: Political awareness moderates the influence of social influence on Re-Use Intention of Social Media for Political Participation.

Ha11: Political awareness moderates the influence of facilitating conditions on the intention to participate in politics.

3 Case and methodology

3.1 Research approach

This study adopts a quantitative causal approach to test hypotheses derived from integrating UTAUT2 and connective action theory. Following Sekaran and Bougie (2016), causal research aims to examine cause-and-effect relationships. The approach is suitable for analyzing how technological factors influence political participation, with intention as a mediator and political awareness as a moderator.

The hypothetico-deductive model develops and tests theory-driven hypotheses through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). SEM enables the simultaneous analysis of multiple latent variables and their interrelations. This design is appropriate for validating a modified UTAUT2 model in the context of digital political participation among Generation Z in North Sumatra.

3.2 Population and research sample

The research population consists of social media users from Generation Z students pursuing higher education in North Sumatra Province, Indonesia. The chosen design is appropriate for the homogeneous population base and research context. The sample selection is in accordance with the research objectives and conducted through simple random sampling, with a sample size in line with (Hair et al., 2019), which suggests a range between 200 and 500 samples for the maximum likelihood estimation method. The sample size for this study is 500. After determining the sample size, the author established the representation quota for universities, including both public and private institutions’ students, based on proportional student enrollment (Quota sampling). Additional criteria included students who had not yet begun their final thesis and were at least in their third semester. Inclusion criteria were determined based on proportional university origin. Subsequently, the researcher collected data using non-probability sampling where the researcher selected the most accessible or nearest subjects or units to participate in the research (Convenience Sampling). To reduce subjective bias in data collection, the researcher provided explanations to data collectors regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria, including the importance of collecting data at different times and different locations within each campus.

3.3 Measurement

The measurement of variables is adapted to the context. Performance Expectancy (PE) is developed based on (Venkatesh et al., 2003) and consists of four statements, including: “Using social media will help me participate in politics more quickly,” and “Using social media will increase my efficiency in political participation.” The Goodness of Fit (GOF) values, which indicate the correspondence between data and model, were satisfied with GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.99, and CFI = 0.994. The PNFI value > 0.6 was 0.642.

Effort Expectancy (EE) is developed based on (Venkatesh et al., 2003) according to the context, with statements like: “My interaction with social media for political participation will be clear and easy to understand,” and “It will be easy for me to become skilled in using social media for political participation.” The results of individual model testing demonstrated that GOF values were satisfied, for example GFI = 0.987, RMR = 0.16, IFI = 0.99, and CFI = 0.991. The PNFI value was 0.682.

Social Influence is measured based on Venkatesh et al. (2003) with three indicators: “People whose opinions I value would prefer me to use social media,” “People who are important to me think that I should use social media,” and “People who influence my behavior think that I should use social media.” The model testing results demonstrated that GOF values were also adequate, namely RR = 0.00, GFI = 1, CFI = 1, and PNFI = 0.72.

Facilitating Conditions are adopted by Venkatesh et al. (2003) with four indicators: “I have the necessary resources to use social media (FC-1),” “I have the necessary knowledge to use social media,” “I can get help from others when I have difficulties using social media-based IT,” and “I can consult the Government Help Centre if I have difficulty using social media.” The testing results demonstrated that the original UTAUT instrument had adequate GOF values. GFI was 0.99, AGFI was 0.924 with TLI value of 0.968 and CFI of 0.995.

To measure the intention to adopt social media according to context, intention is operationalized as the degree to which an individual formulates conscious plans to adopt technology that functions as a facilitator for Generation Z’s political aspirations in the future. The author integrates the perspectives of Venkatesh et al. (2003) and Venkatesh and Davis (2000) regarding intention with political participation intention developed based on Kabra et al. (2017) with statements such as: “I intend to use social media systems in the future for participation in politics,” and “I predict I would use social media-based IT in the future.” Individual testing results demonstrated adequate GOF values. GFI was 0.98, NFI was 0.993, IFI was 0.99, TLI was 0.96, and CFI was 0.994.

Political awareness refers to Bartle (2000), consisting of dimensions like factual political knowledge, perceived level of interest in politics, and policy knowledge. Political participation measurement is based on Kanagavel and Chandrasekaran (2014), with a focus on online participation (6 statements) and offline participation (5 statements). Individual testing results demonstrated adequate GOF values. CMIN/DF was 2.949, GFI was 0.978, NFI was 0.99, IFI was 0.993, TLI was 0.985, and CFI was 0.993.

This comprehensive questionnaire is structured into three principal sections. The first section is dedicated to collecting demographic data from respondents, encompassing information such as their university of origin, hometown, field of study, organizational involvement, and monthly living expenses. The second section focuses on evaluating the online political participation of students, delving into their preferred social media platforms, frequency of usage, and the utilization of social media as a political tool. Lastly, the third section investigates behavior and political participation through social media channels. Each question within the survey is measured using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The survey was conducted directly at each campus by enumerators, utilizing the Google Form platform instead of traditional paper questionnaires. The data collection process started in July 2024 and ended in August 2024. During the field data collection process, enumerators successfully gathered data from a total of 504 respondents distributed across various campuses. Once the data were collected through Google Forms, the research proceeded to the subsequent phase, involving coding and analysis.

3.4 Common biased method

To reduce Common Method Bias (CMB) in this study, several important steps were taken by the researcher. First, data collection for exogenous and endogenous variables was separated over three weeks: the first week for exogenous variables, the second week for mediating variables, and the third week for endogenous variables. Additionally, the researcher provided clear instructions in the questionnaire and ensured that respondent identities remained anonymous to reduce social desirability bias. Statistical techniques such as Harman’s Single Factor Test or Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were used to identify the presence of CMB. The researcher also avoided using both positively and negatively worded statements in the questionnaire to prevent response patterns and acquiescence bias (the tendency to agree with statements). Respondents were informed that their answers would only be used for research purposes and were not directly related to the study, ensuring that no risks were associated with their participation in this study.

3.5 Research data analysis

The steps in data analysis using covariance-based SEM according to Hair et al. (2019) are: (1) Defining individual constructs, (2) Developing the overall measurement model, (3) Designing a study to produce empirical results, (4) Assessing the measurement model validity, (5) Specifying the structural model, (6) Assessing structural model validity, (7) Hypothesis testing. For moderation hypothesis testing, the researcher used the SPSS 23 Proceed program.

4 Findings

4.1 Defining individual constructs

The number of items and dimensions have been based on references that have been proven valid (with a validity value > 0.30) and reliable (with a reliability value > 0.70). With these results, the instrument is considered appropriate and can be used in the main research. The individual GOF test results indicate that the variable constructs align with the field data. Each construct has a GOF value that shows acceptance as a concept that can be used in the research.

4.2 Developing the overall measurement model

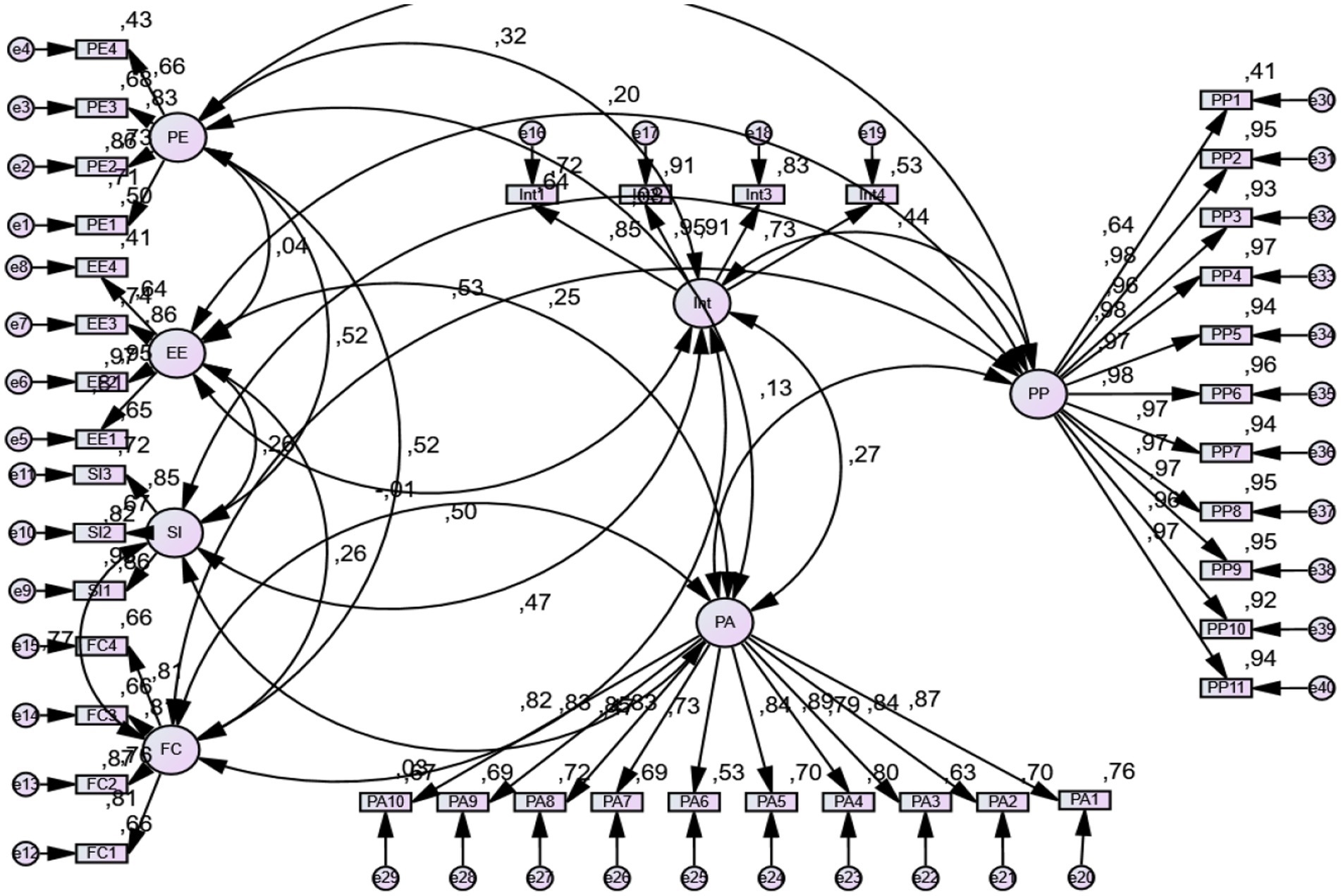

The test results of each indicator are related to its latent variables with varying levels of correlation (Figure 2).

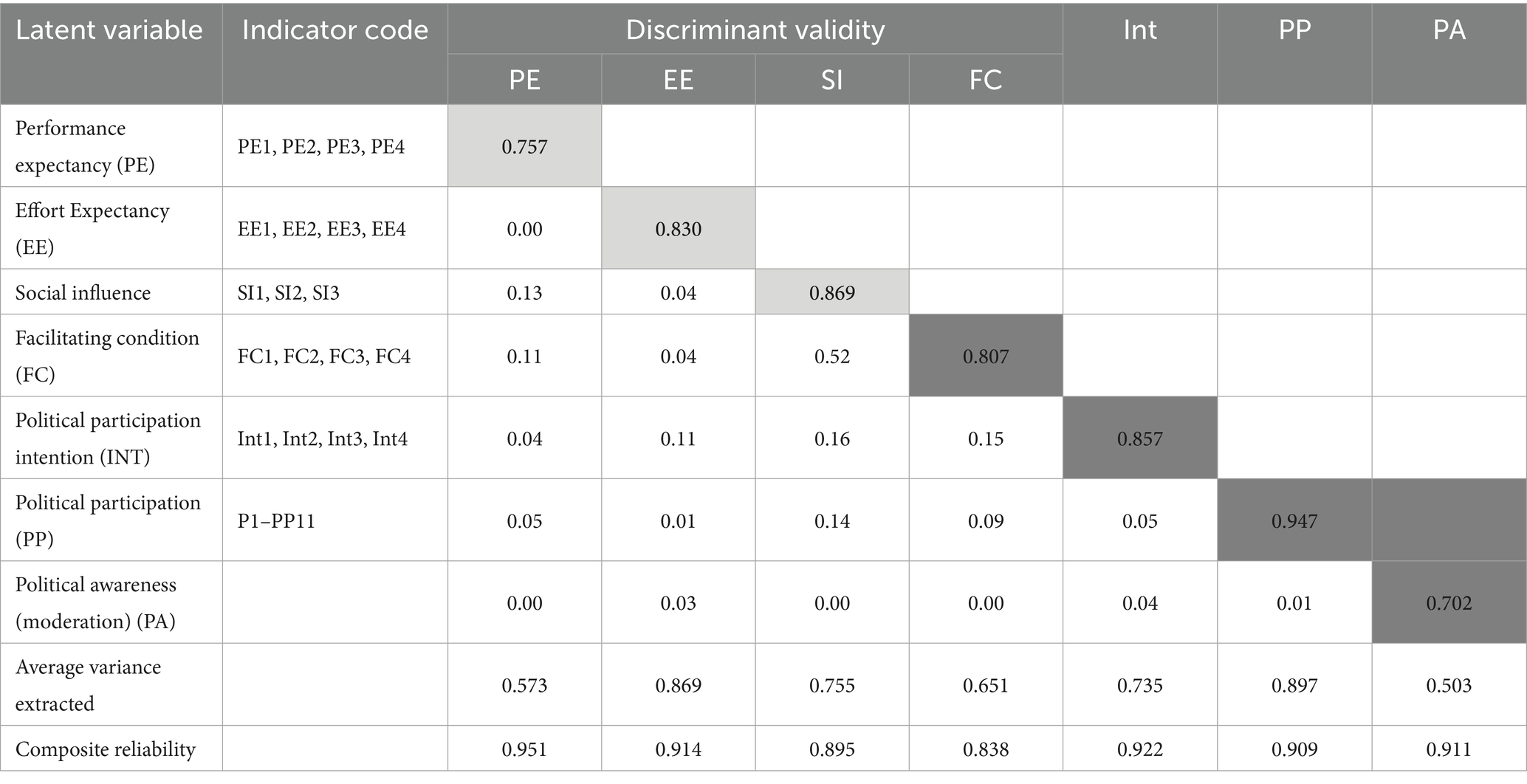

The results of the CFA model testing indicate that the observed data align with the hypothesized relationship model. The relationship between observed variables and latent variables is consistent with expectations based on theory. The observed variables adequately represent the theoretical constructs (PE, EE, SI, FC, Int, PA, PP). Performance Expectancy (PE) has an impact on Intention (Int) with a path coefficient of 0.32. This coefficient reflects the direct influence of one latent variable on another. The factor loadings show that most indicators strongly correlate with their respective constructs, indicating a valid measurement structure. The correlations between constructs suggest that the concepts are interrelated, potentially supporting a larger theoretical framework. The results of the construct validity tests(Convergent Validity, Discriminant Validity, Nomological Validity) are acceptable.

The factor loadings are acceptable (> 0.5). The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values are acceptable, for example, Performance Expectancy (PE) has an AVE of 0.573, which means that changes in Performance Expectancy (PE) as a latent variable can be explained by its observed variables (indicators) by 57.3%, indicating adequate explanatory power. The Composite Reliability (CR) values are greater than 0.7, with Performance Expectancy (PE) having a Composite Reliability of 0.951. The results of the Discriminant Validity test show that each observed variable constructed in the study measures a unique construct and does not overlap with other latent variables. The Nomological Validity is acceptable because the model demonstrates relationships between constructs that are consistent with existing theory. According to the testing results in Table 1, the Fornell-Larcker criterion results demonstrate that the square root of AVE is higher than the inter-construct correlations. For example, the square root of EE is 0.757, which is greater than the correlations between constructs in the study. As an illustration, the correlation between FC (Facilitating Conditions) and SI (Social Influence) is 0.52. The square root of AVE for SI is 0.869 and for FC is 0.807. Both values (0.869 and 0.807) are greater than 0.52. The Fornell-Larcker criterion is satisfied.

Table 1. Standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted, composite reliability s, discriminant validity.

4.3 Designing a study to produce empirical results (sample size, estimation model, i.e., MLE, missing data; identification problems)

The Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) estimation model is used with a sample size greater than 200, by the requirements of this method. The data are normally distributed with a p-value of 0.4021 (p > 0.05), indicating normal distribution. There is no missing data, and no identification issues hinder the testing process using Covariance-Based SEM. The test results also show that the data are normally distributed and exhibit linearity. Additionally, no outliers were found, allowing the analysis to proceed without any data-related constraints.

4.4 Model evaluation

4.4.1 Assessing the measurement model validity

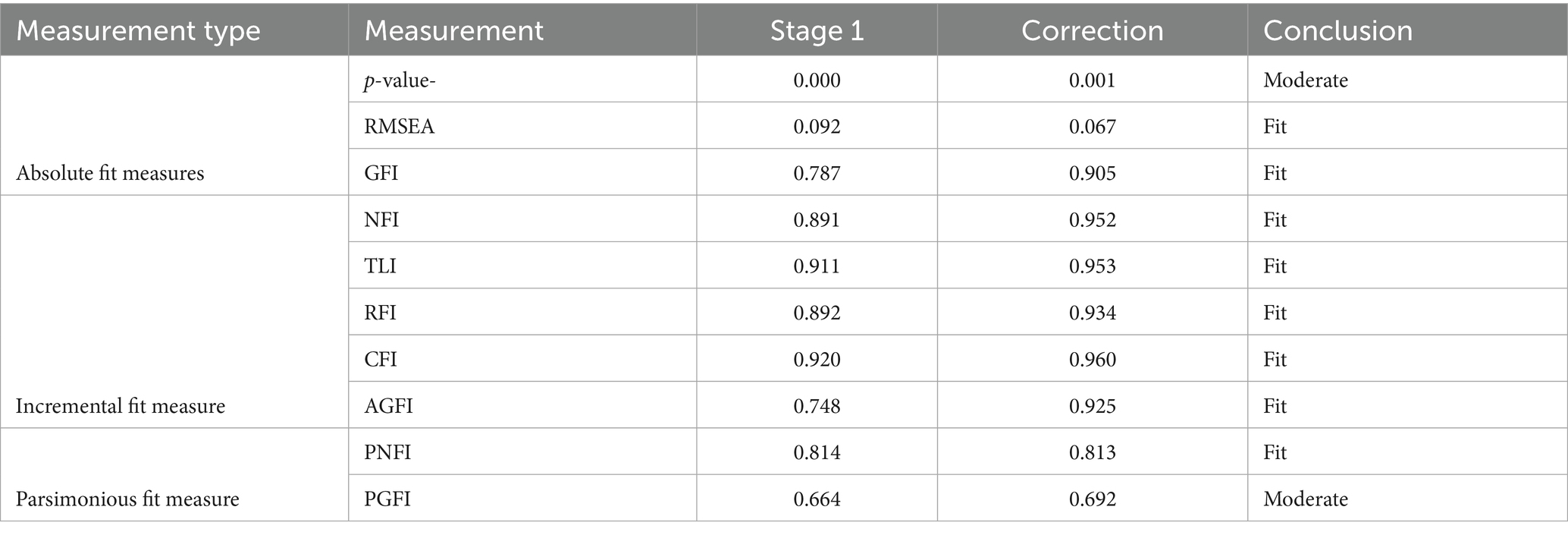

The test results for overall fit show that each GOF criterion is met as can be seen in Table 2. As follows:

The results of the first-stage test indicate that the model is not yet fit. Improvements were made following Hair et al. (2019), and the model showed significant improvement in almost all fit indices. In the final stage, the model achieved a good fit, meaning the data aligns with the model constructed in the research. The overall improved model is now fit and suitable for use, with most fit metrics reaching ideal values. Only a few metrics remain moderate, but this does not diminish the overall quality of the model fit (Table 3).

4.5 Hypothesis testing

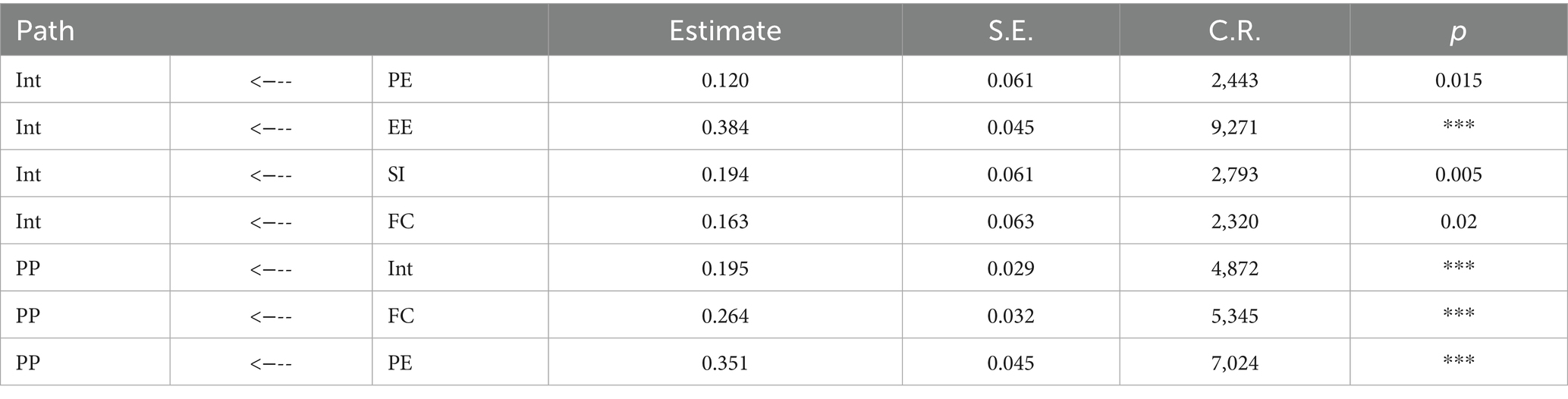

The results of the relationship test indicate a relationship between variables with varying levels of influence strength.

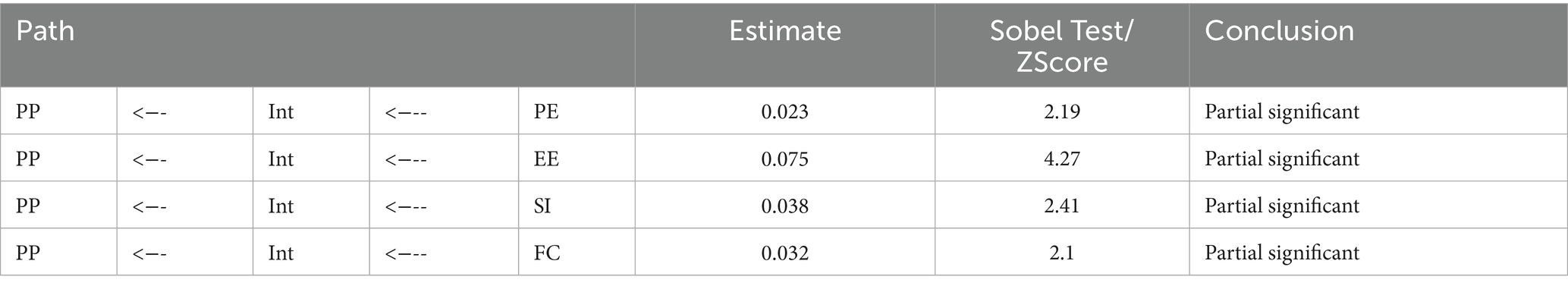

Next, are the results of the mediation variable test as can be seen in Table 4.

The results of the mediation test indicate that Intention acts as a partial mediator. Although the mediation effect is partial, its significance shows that Intention plays an important role as a mediator, while these independent variables can also have a direct effect on political participation. Effort Expectancy (EE) shows the strongest mediation effect through Intention, with the highest Z-score value (4.27), indicating that EE plays a more significant role in enhancing Intention, which ultimately impacts Perceived Performance.

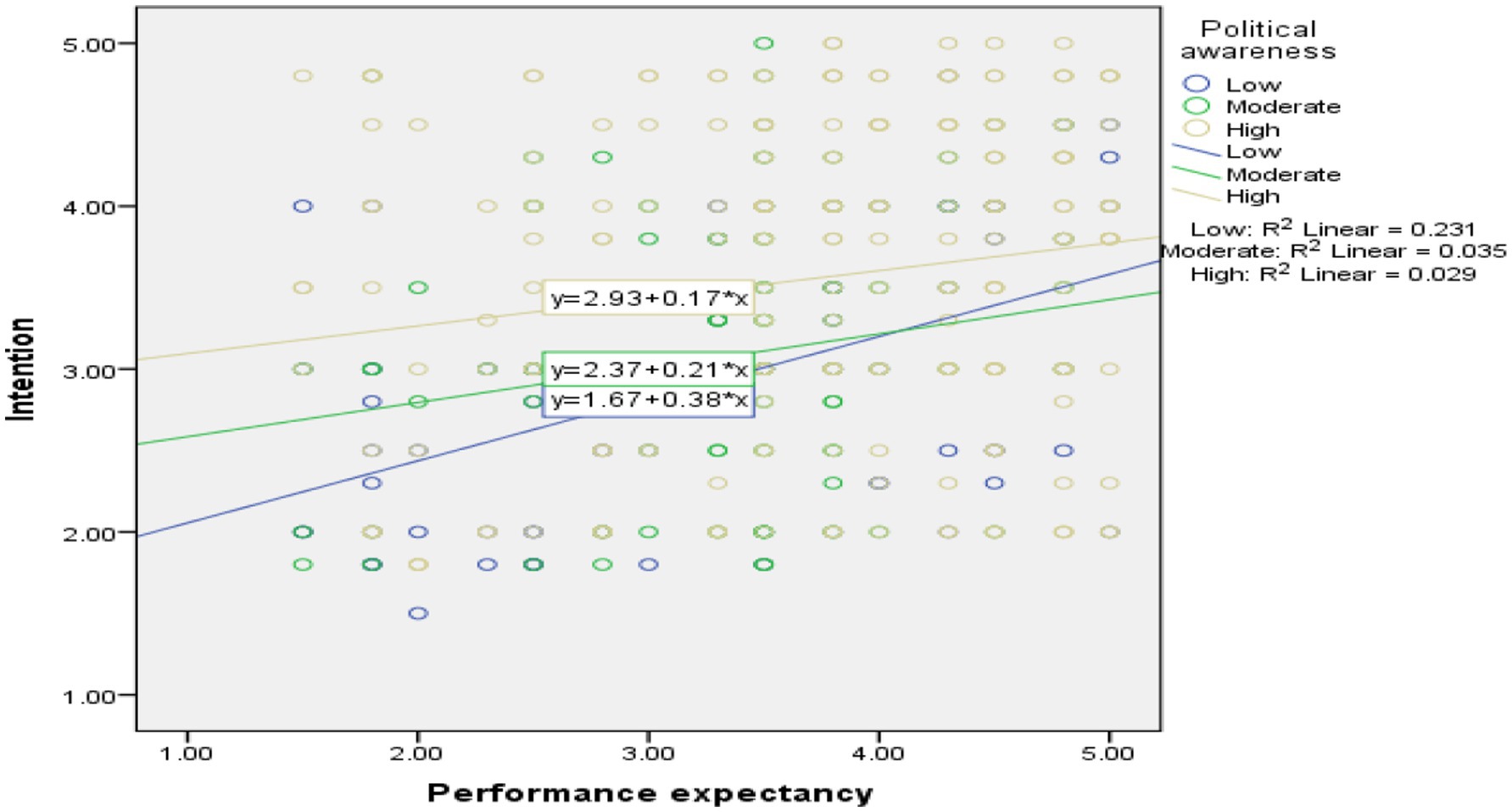

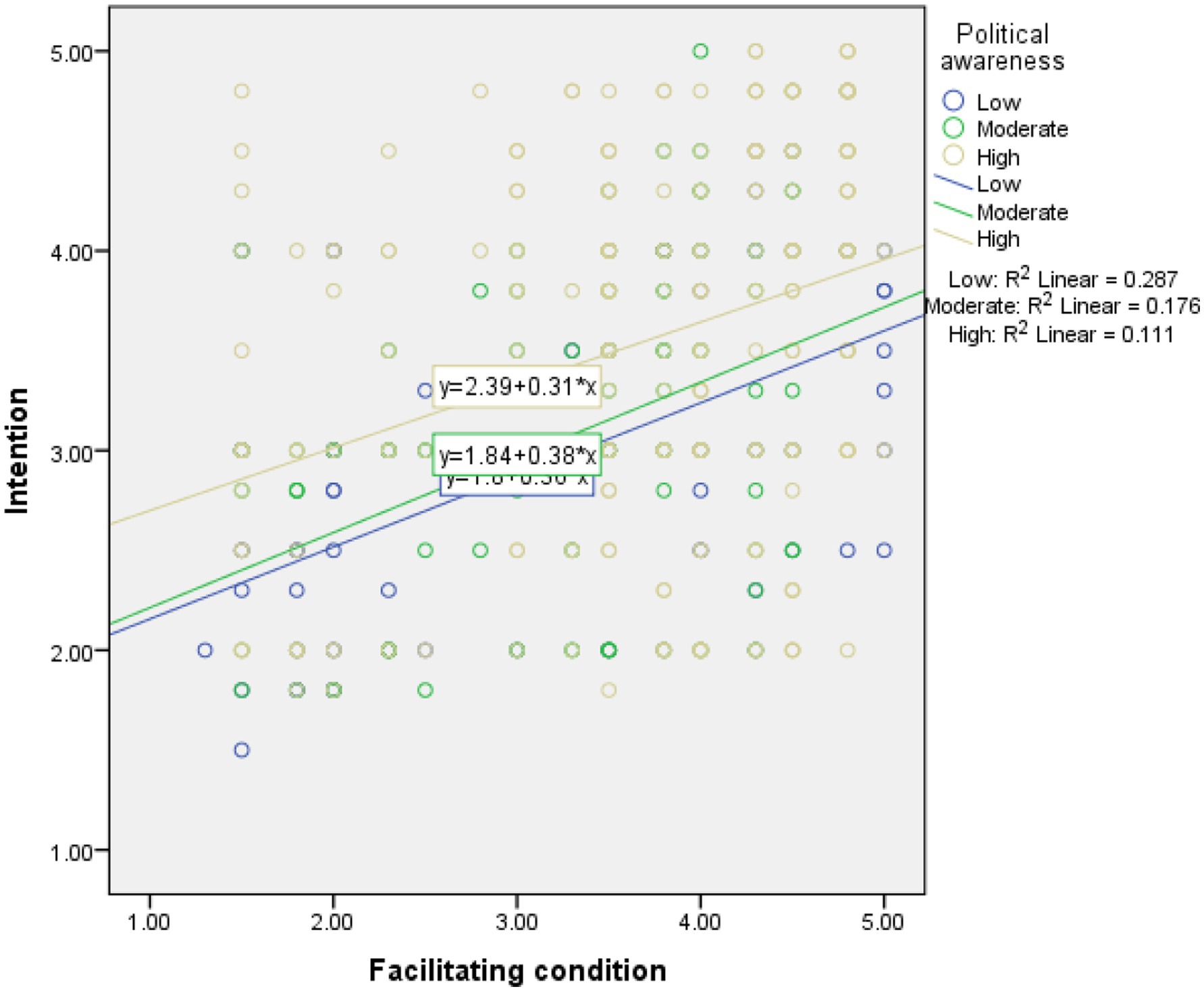

The results of the moderation test can be seen in the Figure 3.

According to the test results, political Awareness, Performance Expectancy, and Intention. For the group with low political awareness, Performance Expectancy strongly influences Intention, whereas, for individuals with moderate to high political awareness, the use of technology does not strengthen the intention to participate in politics (Figure 4).

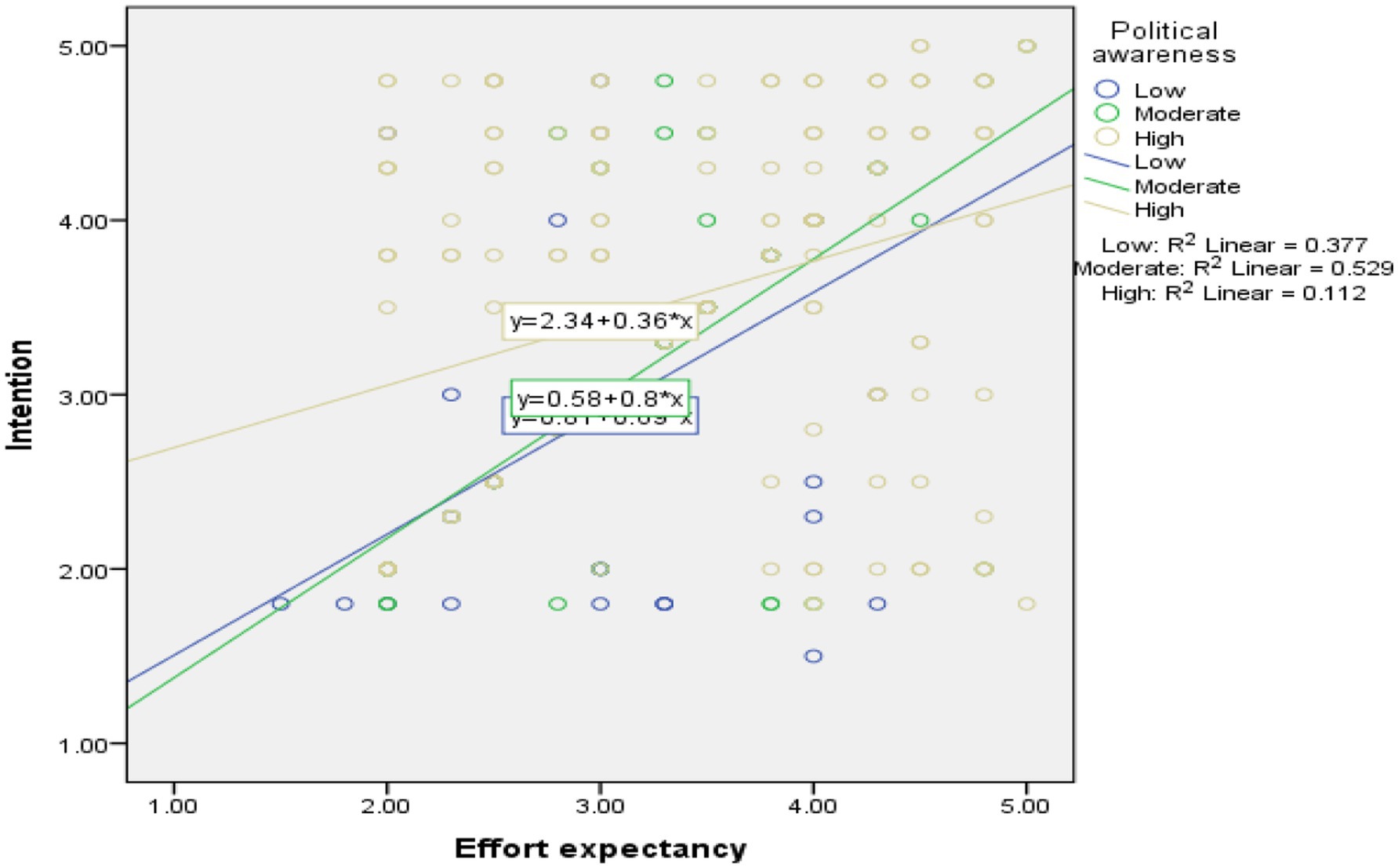

The study results indicate that users with low and moderate Political Awareness show a stronger relationship between Effort Expectancy and Intention, whereas, for those with high Political Awareness, the ease of use factor is less significant in strengthening the intention to participate in politics. For individuals with high Political Awareness, Effort Expectancy has a weak influence on Intention. The ease of using technology is less emphasized. Users may focus more on aspects such as ethical values, political implications, or the social impact of using technology when forming their intention to participate in politics. On the other hand, there is the formation of spaces that constitute a combination of online and offline hybrid activism among Gen Z (Figure 5).

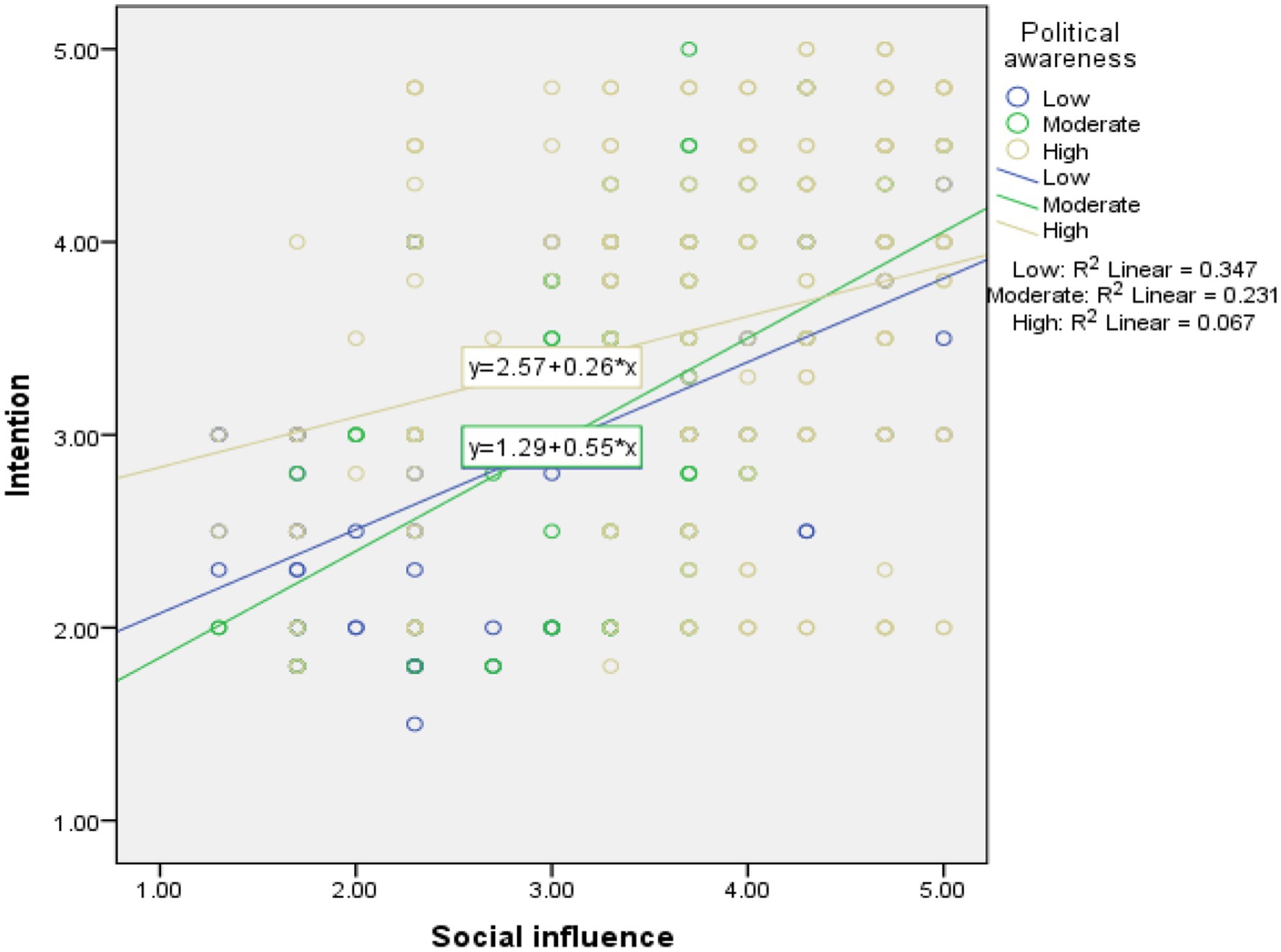

Consistent with UTAUT2, social influence has a different impact on the intention to behave based on the level of political awareness, which acts as a moderating factor. According to UTAUT2, factors such as experience or voluntariness can moderate the effect of social influence. Here, political awareness can be considered as a substitute for these moderating factors, influencing how responsive individuals are to social pressure. Individuals with high political awareness are more likely to rely on their personal beliefs or knowledge rather than being influenced by others in their intention to participate. In contrast, those with moderate or low political awareness are more responsive to social influence when it comes to their intentions (Figure 6).

In groups with low political awareness, adequate support or infrastructure strengthens the intention to participate. This may be because they require more assistance or encouragement from their surrounding environment to form an intention to engage in politics. In contrast, individuals with high political awareness tend to be less influenced by these external conditions, in line with the assumption of UTAUT2 that external factors are less important for individuals who are more independent or knowledgeable.

5 Discussion

Based on the results of the study, Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, Social Influence, and Facilitating Conditions influence political intention and participation. Intention mediates the effect of the variables in the UTAUT model, and Political Awareness strengthens this effect. This is consistent with previous studies, such as Venkatesh et al. (2012), Jain and Jain (2022), and Tseng et al. (2022) which indicate that in the context of political participation, these influences remain consistent.

The analysis results show that the four factors in the UTAUT collectively have a positive and significant impact on the use of social media for online political participation. More specifically, the analysis reveals that Perceived Usefulness (PU) has a positive and significant effect in predicting the use of social media for political participation. This means that the higher Generation Z’s perception of the usefulness of social media for political activities, the greater their tendency to use it. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) also proves to have a positive and significant effect; the easier social media is to use, the more likely Generation Z is to use it as a tool for online political participation.

Technology has facilitated the formation of action networks and the spread of political ideas. The concept of action frames is highly relevant in this context, where social media serves as a platform for various political narratives that can quickly spread and mobilize the masses, as proposed by Bennett and Segerberg (2012, 2015). Digital technology enables the formation of action networks at lower costs through action frames — media, symbols, or objects disseminated via communication technologies — making it easier for individuals to participate in social movements without relying on formal organizations. The differences between various internet technologies do not diminish the interaction between specific technologies and human users for political actions (Pond and Lewis, 2017). Technology adoption is based on perceived benefits (or ease of use) in encouraging an individual to use technology, in line with the UTAUT conceptual framework. This aligns with Harff and Schmuck (2024), Harris et al. (2023), and Dekoninck (2022) who articulated the important role of social influence in technology adoption for political participation. Social influence facilitates decentralized forms of participation consistent with connective action theory.

UTAUT explains how personal choices and expressions are made in the digital space. However, interactions between individuals can trigger collective action, even physically in the field. The results of this study provide insight into how technology, particularly social media, shapes the political participation landscape of Generation Z. Generation Z participants in the digital space are no longer bound by rigid personal identities or collective ideologies. Individuals are motivated to engage in political activities based on personal motivation, interests, or identities. Each individual can join actions or campaigns without feeling obligated to belong to a particular organization. Social media and digital platforms enable Generation Z to participate directly and spontaneously, spreading political messages and actions through personal connections, such as sharing on social media, without requiring formal structures or organizations. Their involvement is more temporary and flexible, depending on issues or campaigns they find relevant. Political participants from Generation Z tend to be more independent and inspired to act either individually or within networks.

Technology not only influences individuals personally but also triggers collective action based on shared views about relevant political issues, pressures, and the existence of virtual public spaces where people can connect with others who share similar political interests (Hansson et al., 2024; Kim and Kim, 2025; Lukito et al., 2024). Connectivity on social media becomes a form of collective action based on common political perspectives. Digitalization enables politically driven action that is more network-based and individual-oriented. In this form of action, participation occurs through direct connections between individuals, and the nature of the action is more flexible, decentralized, and personalized, in contrast to traditional collective action, which is more hierarchical and structured. This aligns with the study of Bernroider et al. (2022), who emphasize collective action based on connections within the digital space. Leong et al. (2020) argue that social media plays a crucial role in transforming and shaping the dynamics of collective action, offering new ways for individuals to interact, participate, and engage in social movements while confronting challenges related to commitment and the sustainability of relationships. However, collective action does not solely rely on resources and collective identities; it also depends on the dynamic relationships that evolve interdependently among individuals. This creates new forms of involvement that can either strengthen or weaken social movements. Therefore, movements and connectivity in the digital space are highly dynamic, causing political participation among Generation Z to be equally fluid.

Connective action facilitated by social media provides new opportunities for Generation Z to engage in politics in a way that is easier, more efficient, and personalized, in line with findings from UTAUT, which highlight the importance of perceived usefulness and ease of use in determining technology adoption. However, on the other hand, there is a high level of dynamism in the digital world, where individual participation is fluid. Political awareness not only strengthens the intention to participate in politics but also encourages collective action in politics. Social media platforms facilitate the formation of wide social networks, ease communication, and strengthen collective identity, thereby encouraging collective political participation. Therefore, to ensure the stability of choices and participation, understanding the political awareness of Generation Z is essential. Building political awareness should be the primary orientation, as it enhances the likelihood of sustained and meaningful political engagement in the digital age. This aligns with Naranjo-Zolotov et al. (2019) and Lai and Beh (2025) who explored psychological aspects to avoid the trap of technological solutionism in participation. Participation intention is not merely the result of technology perception, but also political trust and perception of government legitimacy (Huda and Amin, 2023). In this study, political awareness is conceptualized as a multifaceted construct related to psychological, cognitive, and social aspects that closely influences how Generation Z understands and interacts politically to support democratic governance processes. The study results open opportunities for developing new theoretical frameworks of UTAUT that are more adaptive in explaining young generation’s digital political participation through social media.

In line with previous studies on the importance of political awareness, such as Zagidullin et al. (2021) and Claassen (2011), individuals with high political awareness tend to have more independent motivation and intention to participate in digital politics. They are less reliant on external conditions or social influence and are instead driven by a deep understanding of political issues. In contrast, individuals with low political awareness require more support or facilitating conditions to form the intention to participate in politics. This reinforces the importance of political awareness in determining how an individual interacts with and participates in the digital political environment.

However, it must be understood that according to the moderation test results, the position of the moderating variable, namely political awareness, presents a paradox. The testing results demonstrate an increasing moderating effect that progressively diminishes as political awareness increases among Generation Z cohorts. This aligns with Showden et al. (2025) who argued that Generation Z creates spaces reflecting the integration of online and offline elements (third space) termed hybrid activism. Generation Z forms a third space that constitutes a combination of digital space and real action space for political participation. This condition weakens the intention to adopt social media for political participation. According to connective action theory, users connect the online world with offline real political participation such as field demonstrations as actual behavior without high intention to adopt social media technology for political participation. Actual political behavior becomes more tangible as political awareness increases. Online interactions expand reach through social media as articulated by Kim and Kim (2025).

This aligns with connective action theory as articulated by Bennett and Segerberg (2012) and Kasimov (2025) that political mobilization in the digital era no longer always depends on strong collective identities, formal organizations, or uniform struggle frameworks. Connective action enables individuals to act based on personalized individual action frames while remaining connected through digital technology (such as social media, forums, or online communication platforms). This condition causes the intensity of social media usage for political participation to decline. Resonance with particular messages, issues, or symbols that spread horizontally in digital spaces is actualized in the form of real participation. However, Generation Z’s participatory forms in the third space represent a double-edged sword. Without wisdom in using social media and understanding responsible political participation channels, the third space is vulnerable to disruption and may even become a space that undermines democratic order. However, social media and digital technologies can be powerful tools for those with high political awareness to voice their political aspirations, without relying on external factors that facilitate Generation Z’s participation in politics.

6 Conclusion, implications, and direction for future research

The main variables in the UTAUT model—Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, Social Influence, and Facilitating Conditions—have a significant effect on political intention and participation, with Intention acting as a mediator and political awareness as a reinforcing factor. Technology plays a crucial role in forming action networks and spreading political ideas, in line with the concept of action frames. In the digital space, Generation Z tends to be more independent, focusing on issues that are personally relevant without being tied to collective ideologies or formal organizations. Social media enables spontaneous and flexible participation, making their political engagement more dynamic and based on personal interests or identities. Social media also supports collective action based on networks, where individuals connect in virtual public spaces to share political views. Unlike traditional hierarchical collective action, digital political action is more decentralized and personalized. Connective action on social media provides Generation Z with a more accessible and efficient way to participate in politics. Political awareness strengthens their intention to participate and triggers collective action, expanding social networks, reinforcing collective identities, and encouraging more inclusive and responsive political participation.

The Connective Action Theory and the UTAUT provide an excellent framework for understanding how technology, particularly social media, has revolutionized political participation, especially among younger generations like Generation Z. The integration of UTAUT and Connective Action Theory has the potential to expand the understanding of mechanisms for building collective action based on shared political orientations and views. The study’s findings offer a new analytical framework for understanding contemporary social movements based on a micro-level understanding of political intention and participation in line with the UTAUT model. The research helps us comprehend how technology can reshape the political landscape from the individual level to the macro level, influencing election outcomes. The dynamics of political participation in the digital space are more individualistic, decentralized, and network-based, highlighting the need for political awareness to moderate the use of technology for political engagement. These findings also contribute to a more adaptive and relevant theoretical framework for the digital era in examining political participation, particularly among younger generations who prefer more flexible and personal modes of engagement.

A deep understanding based on Connective Action Theory and UTAUT has significant implications for developing more effective communication strategies on social media. Political parties, non-profit organizations, and activists can leverage these findings to design content that is relevant, engaging, and easily comprehensible to increase youth engagement. Media literacy is essential for equipping young people with critical skills to evaluate the information they encounter on social media. This will help them become more informed and responsible digital citizens. For the government, social media can be optimized to shape public opinion and encourage political participation. Policies that support equitable access to technology and protect freedom of expression are crucial.

Given the research limitations that the study focused only on Generation Z students in North Sumatra, the results are less generalizable to other Indonesian regions with different social, cultural, and political conditions. Future research should investigate Generation Z across various provinces or cross-nationally with different cultures to achieve more comprehensive results. Data collection should not rely solely on self-report questionnaire surveys. Alternative data collection methods such as in-depth interviews or social media content analysis would provide more contextual understanding of political participation meanings. The research modified UTAUT by incorporating political awareness as a moderator and connecting it with connective action theory. However, political-psychological aspects such as political cynicism, institutional trust, or ideological orientation have not been fully accommodated, whereas these factors can influence digital political participation. The research did not differentiate in-depth characteristics of each platform (TikTok, Instagram, Twitter/X, Facebook) despite each medium having different algorithmic logic, audiences, and impacts on political participation. Comparative exploration of how different platforms affect political intention and actual participation is needed.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical clearance and approval were granted by the Health Research Ethical Committee of Universitas Sumatera Utara. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. TS: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AS: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Lembaga Penelitian Universitas Sumatera Utara under Grant number 28/UN5.2.3.1/PPM/KP-TALENTA/R/2023.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alam, M. S., Khan, T.-U.-Z., Dhar, S. S., and Munira, K. S. (2020). HR professionals’ intention to adopt and use of artificial intelligence in recruiting talents. Bus. Perspect. Rev. 2, 15–30. doi: 10.38157/business-perspective-review.v2i2.122

Amin, M., and Ritonga, A. D. (2024). Diversity, local wisdom, and unique characteristics of millennials as capital for innovative learning models: evidence from North Sumatra, Indonesia. Societies 14:260. doi: 10.3390/soc14120260

Andersen, K., Ohme, J., Bjarnøe, C., Bordacconi, M. J., Albæk, E., and De Vreese, C. (2020). Generational gaps in political media use and civic engagement: from baby boomers to generation Z (1st ed.). London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003111498

Bartle, J. (2000). Political awareness, opinion constraint and the stability of ideological positions. Polit. Stud. 48, 467–484. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00270

Bennett, W. L., and Livingston, S. (2025). Platforms, politics, and the crisis of democracy: connective action and the rise of illiberalism. Perspect. Polit., 1–20. doi: 10.1017/S1537592724002123

Bennett, W. L., and Segerberg, A. (2009). Collective action dilemmas with individual mobilization through digital networks. In European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) General Conference, Potsdam.

Bennett, W. L., and Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 15, 739–768. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661

Bennett, W. L., and Segerberg, A. (2015). “The logic of connective action: digital media and the personalization of contentious politics” in Handbook of digital politics (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 287–338.

Bernroider, E. W. N., Harindranath, G., and Kamel, S. (2022). From connective actions in social movements to offline collective actions: an individual level perspective. Inf. Technol. People 35, 205–230. doi: 10.1108/ITP-08-2020-0556

Camilleri, M. A., and Camilleri, A. C. (2023). Learning from anywhere, anytime: utilitarian motivations and facilitating conditions for mobile learning. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 28, 1687–1705. doi: 10.1007/s10758-022-09608-8

Carlisle, J. E., and Patton, R. C. (2013). Is social media changing how we understand political engagement? An analysis of Facebook and the 2008 presidential election. Polit. Res. Q. 66, 883–895. doi: 10.1177/1065912913482758

Chinedu-Okeke, C. F., and Obi, I. (2016). Social media as a political platform in Nigeria: a focus on electorates in south-eastern Nigeria. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 21, 6–22. Available online at: https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol.%2021%20Issue11/Version-1/B2111010622.pdf

Claassen, R. L. (2011). Political awareness and electoral campaigns: maximum effects for minimum citizens? Polit. Behav. 33, 203–223. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9129-6

Coleman, S., and Freelon, D. (2015). Introduction: Conceptualizing digital politics. In Coleman, S., and Freelon, D. (Eds.)1–15.

Davis, F. D. (1985). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems.

Deckman, M. M. (2024). The politics of gen Z: How the youngest voters will shape our democracy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dekoninck, H., and Schmuck, D. (2022). The Mobilizing Power of Influencers for Pro-Environmental Behavior Intentions and Political Participation. Environ. Commun, 16, 458–472. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2022.2027801

Durotoye, T., Goyanes, M., Berganza, R., and Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2025). Online and social media political participation: political discussion network ties and differential social media platform effects over time. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev., 1–21. doi: 10.1177/08944393251332640

Earl, J., McKee Hurwitz, H., Mejia Mesinas, A., Tolan, M., and Arlotti, A. (2013). Twitter and protest policing during the Pittsburgh G20. Information. Communication & Society, 16, 459–478. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.777756

Finch, G. (1974). Participation in America: political democracy and social equality. by Sidney Verba and Norman H. Nie. Political Science Quarterly, 89, 674–676. doi: 10.2307/2148474

Fox, S. (2014). Is it time to update the definition of political participation? Parliamentary Affairs, 67, 495–505. doi: 10.1093/pa/gss094

Gibson, R., and Cantijoch, M. (2013). Conceptualizing and measuring participation in the age of the internet: is online political engagement really different to offline? J. Polit. 75, 701–716. doi: 10.1017/S0022381613000431

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hansson, K., Sveningsson, M., and Ganetz, H. (2024). Processes of recognition: from connective to collective action in the Swedish #MeToo movement. Fem. Media Stud., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2024.2443000

Harff, D., and Schmuck, D. (2024). Is authenticity key? Mobilization by social media influencers versus celebrities and young people’s political participation. Psychol. Mark. 41, 2757–2771. doi: 10.1002/mar.22082

Harris, B. C., Foxman, M., and Partin, W. C. (2023). “Don’t make me ratio you again”: how political influencers encourage platformed political participation. Soc. Media Soc. 9:7944. doi: 10.1177/20563051231177944

He, T., and Li, S. (2019). A comparative study of digital informal learning: the effects of digital competence and technology expectancy. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 1744–1758. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12778

Hooghe, M. (2014). Defining political participation: how to pinpoint an elusive target? Acta Polit. 49, 337–348. doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.7

Huda, M. N., and Amin, K. (2023). Understanding the intention to use LAPOR application as e-democracy in Indonesia: an integrating ECM and UTAUT perspective. eDemocracy Open Gov. 15, 22–47. doi: 10.29379/jedem.v15i1.786

Jain, V., and Jain, P. (2022). From industry 4.0 to education 4.0: acceptance and use of videoconferencing applications in higher education of Oman. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 14, 1079–1098. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-10-2020-0378

Kabakus, A. K., Bahcekapili, E., and Ayaz, A. (2023). The effect of digital literacy on technology acceptance: an evaluation on administrative staff in higher education. J. Inf. Sci. 51, 930–941. doi: 10.1177/01655515231160028

Kabra, G., Ramesh, A., Akhtar, P., and Dash, M. K. (2017). Understanding behavioural intention to use information technology: insights from humanitarian practitioners. Telematics Inform. 34, 1250–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.05.010

Kanagavel, R., and Chandrasekaran, V. (2014). Creating’ political awareness through social networking – an empirical study with special reference to Tamil Nadu elections, 2011. J. Soc. Media Stud. 1, 71–81. doi: 10.15340/214733661177

Karatzogianni, A., Ong, J., Kuntsman, A., and Xin, L. (2023). “Digital politics: defining, exploring and challenging the field” in Digital politics, digital histories, digital futures (Emerald Publishing Limited), 11–23. doi: 10.1108/978-1-80382-201-320231002

Karpf, D. (2017). Digital politics after trump. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 41, 198–207. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2017.1316675

Kasimov, A. (2025). Decentralized hate: sustained connective action in online far-right community. Soc. Mov. Stud. 24, 199–217. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2023.2204427

Kim, D. K. D., and Kim, I. (2025). Social media as a seed of connective democracy in Myanmar (Burma): freedom of speech, contractarianism, and strategic use of social media. Soc. Media Soc. 11:9996. doi: 10.1177/20563051251329996

Koc-Michalska, K., and Lillker, D. G. (2019). Digital politics: Mobilization, engagement and participation. New York: Routledge.

Lai, R., and Beh, L. S. (2025). The impact of political efficacy on citizens’ e-participation in digital government. Adm. Sci. 15, 1–23. doi: 10.3390/admsci15010017

Lawrence, R. G. (2023). The politics of force: Media and the construction of police brutality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lee, S., Nanz, A., and Heiss, R. (2022). Platform-dependent effects of incidental exposure to political news on political knowledge and political participation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 127:107048. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107048

Leong, C., Faik, I., Tan, F. T. C., Tan, B., and Khoo, Y. H. (2020). Digital organizing of a global social movement: from connective to collective action. Inf. Organ. 30:100324. doi: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2020.100324

Livingstone, S., and Third, A. (2017). Children and young people’s rights in the digital age: an emerging agenda. New Media Soc. 19, 657–670. doi: 10.1177/1461444816686318

Lu, Y., Huang, Y. H. C., Kao, L., and Chang, Y. T. (2023). Making the long march online: some cultural dynamics of digital political participation in three Chinese societies. Int. J. Press/Politics 28, 160–183. doi: 10.1177/19401612211028552

Lukito, J., Lee, T., Martin, Z., Glover, K., Hu, A., and Cui, Z. (2024). Connective action in Myanmar: a mixed-method analysis of spring revolution. Inf. Commun. Soc. 27, 1422–1440. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2023.2289973

McCargo, D. (2021). Disruptors’ dilemma? Thailand’s 2020 gen Z protests. Crit. Asian Stud. 53, 175–191. doi: 10.1080/14672715.2021.1876522

Micó, J.-L., and Casero-Ripollés, A. (2013). Political activism online: organization and media relations in the case of 15M in Spain. Inf. Commun. Soc. 17, 858–871. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.830634

Milbrath, L. W., and Goel, M. L. (1977). Political participation: how and why do people get involved in politics? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 72, 1482–1484. doi: 10.2307/1954644

Naranjo-Zolotov, M., Oliveira, T., and Casteleyn, S. (2019). Citizens’ intention to use and recommend e-participation: drawing upon UTAUT and citizen empowerment. Inf. Technol. People 32, 364–386. doi: 10.1108/ITP-08-2017-0257

Ohme, J., De Vreese, C. H., and Albæk, E. (2018). From theory to practice: how to apply van Deth’s conceptual map in empirical political participation research. Acta Polit. 53, 367–390. doi: 10.1057/s41269-017-0056-y

Parmelee, J. H., Perkins, S. C., and Beasley, B. (2022). Personalization of politicians on Instagram: what generation Z wants to see in political posts. Inf. Commun. Soc. 26, 1773–1788. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2022.2027500

Pond, P., and Lewis, J. (2017). Riots and twitter: connective politics, social media and framing discourses in the digital public sphere. Inf. Commun. Soc. 22, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1366539

Reuter, O. J., and Szakonyi, D. (2015). Online social media and political awareness in authoritarian regimes. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 45, 29–51. doi: 10.1017/S0007123413000203

Rouidi, M., Elouadi, A. E., Hamdoune, A., Choujtani, K., and Chati, A. (2022). TAM-UTAUT and the acceptance of remote healthcare technologies by healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Inform. Med. Unlocked 32:101008. doi: 10.1016/j.imu.2022.101008

Ruess, C., Hoffmann, C. P., Boulianne, S., and Heger, K. (2021). Online political participation: the evolution of a concept. Inf. Commun. Soc. 26, 1495–1512. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.2013919

Saud, M., and Margono, H. (2021). Indonesia’s rise in digital democracy and youth’s political participation. J. Inf. Technol. Polit. 18, 443–454. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2021.1900019

Sekaran, U., and Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Showden, C. R., Barker-Clarke, E., Sligo, J., and Nairn, K. (2025). The connective is communal: hybrid activism in online & offline spaces. Soc. Mov. Stud. 24, 139–158. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2023.2171387

Situmorang, T. P., and Ritonga, A. D. (2025). TikTok and politics: a bibliometric mapping of research trends. Stud. Media Commun. 13:212. doi: 10.11114/smc.v13i3.7616

Stieglitz, S., and Dang-Xuan, L. (2012). “Political communication and influence through microblogging—an empirical analysis of sentiment in twitter messages and retweet behavior.” 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pp. 3500–3509.

Szymkowiak, A., Melović, B., Dabić, M., Jeganathan, K., and Kundi, G. S. (2021). Information technology and gen Z: the role of teachers, the internet, and technology in the education of young people. Technol. Soc. 65:101565. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101565

Theocharis, Y., Boulianne, S., Koc-Michalska, K., and Bimber, B. (2023). Platform affordances and political participation: How social media reshape political engagement. West Eur. Politics, 46, 788–811. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2087410

Theocharis, Y., and Van Deth, J. W. (2017). Political participation in a changing world: Conceptual and empirical challenges in the study of citizen engagement. New York: Routledge.

Tseng, T. H., Lin, S., Wang, Y. S., and Liu, H. X. (2022). Investigating teachers’ adoption of MOOCs: the perspective of UTAUT2. Interact. Learn. Environ. 30, 635–650. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2019.1674888

Turner, A. (2015). Generation Z: technology and social interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 71, 103–113. doi: 10.1353/jip.2015.0021

Van Deth, J. W. (2014). A conceptual map of political participation. Acta Polit. 49, 349–367. doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.6

Venkatesh, V. (2022). Adoption and use of AI tools: a research agenda grounded in UTAUT. Ann. Oper. Res. 308, 641–652. doi: 10.1007/s10479-020-03918-9

Venkatesh, V., and Davis, F. D. (2000). Theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 46, 186–204. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 27, 425–478. doi: 10.2307/30036540

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., and Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 36, 157–178. doi: 10.2307/41410412

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., and Xu, X. (2016). Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: a synthesis and the road ahead. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 17, 328–376. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00428

Williams, M. L. (2021). Students’ perceptions of the adoption and use of social media in academic libraries: a UTAUT study. Communication 47, 76–94. doi: 10.1080/02500167.2021.1876123

Keywords: generation Z, digital politics, online political participation, social media, UTAUT model

Citation: Amin M, Ritonga AD, Situmorang TP and Santoso AD (2025) Revolutionizing political participation: a modified UTAUT model for generation Z in the digital era. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1681050. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1681050

Edited by:

Alberto Asquer, SOAS University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Evie Ariadne, Universitas Padjadjaran, IndonesiaMohammad Nurul Huda, Diponegoro University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Amin, Ritonga, Situmorang and Santoso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muryanto Amin, bXVyeWFudG9hbWluQHVzdS5hYy5pZA==

Muryanto Amin

Muryanto Amin Alwi Dahlan Ritonga

Alwi Dahlan Ritonga Tonny Pangihutan Situmorang1

Tonny Pangihutan Situmorang1