- German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg, Germany

Latin American regionalism is in flux. Regional organizations and forums have experienced crises—some have become paralyzed, while others have disintegrated. Against this backdrop, the concept of liquid regionalism has gained traction. This article explores the analytical value of the concept, examining how it can be operationalized and applied to the current configuration of Latin American regionalism. While liquid regionalism captures important structural dynamics, it may overlook some of the potential advantages of institutional flexibility and the variable geometry of multilateral cooperation. The article proposes broadening the analytical lens by integrating research on regional authority and its contestation. Liquid regionalism and the contestation of regional authority highlight different but intersecting and complementary dimensions of the regional landscape. The ‘solidification’ of Latin American regionalism depends on the consolidation of regional authority. The article distinguishes between different forms of authority: hard authority, soft authority, and smart authority. While more solid forms of regionalism require hard authority, soft authority—grounded in the pooling of expertise—is more compatible with liquid regionalism and a technocratic turn in Latin American regional governance.

1 Introduction

Looking back at the development of Latin American regionalism since the turn of the century, continuity can be observed on the one hand, which manifests itself in the ongoing existence of regional organizations such as MERCOSUR (Mercado Común del Sur), the Andean Community (CAN), the Central American Integration System (SICA), and as a Pan-American organization the Organization of American States (OAS). On the other hand, there have also been changes and innovations due to the emergence of new regional organizations and forums such as ALBA (Alianza Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América), CELAC (Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños), UNASUR (Unión de Naciones Suramericanas), and PROSUR (Foro para el Progreso de América del Sur) or informal groups (Lima Group). And there have been crises (Briceño, 2024) that led to the temporary paralysis of regional forums and organizations (such as CELAC) or even to their disintegration as in the case of PROSUR, the Lima Group and UNASUR.

Latin American regionalism is confronted with a volatile international environment, which since the global financial crisis of 2009 has been characterized by multiple and permanent crises, and by the systemic conflict between a still hegemonic power, the USA, and a competing emerging power, China. The wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, as well as the trade conflicts sparked by President Trump, have further complicated the international scenario, which is alternately characterized as polycrisis (Albert, 2024; Brosig, 2025), permacrisis (Katsikas et al., 2025) or, following Gramsci, as interregnum (Babic, 2020).

Crises are not new to Latin American regionalism (Agostinis and Nolte, 2023). These can have endogenous (triggered by the outcomes of regional cooperation) and exogenous causes which are not directly related to the processes of regional cooperation (or integration) but become stress factors (or stressors) for Latin American regional institutions. Stress factors interact with the characteristics of the region which can lead to an exogenously induced crisis if the stress factors are not mitigated. In terms of regional characteristics, Nolte and Weiffen (2021a,b) differentiate between the demand for regional cooperation (interdependencies and fault lines), regional identity (elite beliefs and mass support), and the supply side consisting of regional leadership and regional institutions.

Over the years, there has been a broad debate on the conceptualization of the fundamental characteristics of Latin American regional institutions. In a handbook article, Malamud (2022) summarizes quite succinctly some of the fundamental features of Latin American regionalism since the 1990s that characterize it regardless of its ups and downs. First, Latin American regionalism is segmented, which means that several subregional organizations (such as MERCOSUR, CAN or SICA) coexist. Second, it overlaps in terms of mandates and membership; most countries belong to several regional organizations (and forums), some of which perform similar tasks. Third, it is flexibly institutionalized which is reflected in “informal negotiation, muddling through, non-incorporation, and non-implementation,” as a result “real-existing regional institutions look very different from treaties and protocols” (Malamud, 2022, 232).

Fourth, Latin American regionalism is “sovereignty-boosting” which “means that Latin American governments aim at strengthening the nation state rather than reaping potential benefits from market integration” (Malamud, 2022, 232). Although the protection of sovereignty is also an important motivation for the creation of regional organizations, it represents “a major obstacle to the deepening of regional integration processes” (Serbin (2010, 18). The orientation of Latin American regionalism towards the protection of sovereignty has hindered the creation of strong, ideally supranational regional institutions capable of ensuring the continuity and sustainability of regional activities in times of crisis, particularly when there is no consensus between presidents (Malamud, 2015).

The ups and downs of regional forums and organizations in Latin America, their transformations and crises have led to the introduction of a variety of new concepts (Quiliconi and Salgado, 2017) that attempt to capture the particularities of each phase or wave of regionalism. Depending on whether regional organizations were in an upswing, or a downturn, different aspects and characteristics were highlighted. Due to the crisis of regional organizations and forums and, in extreme cases, their disintegration, the concept of liquid regionalism (Mariano et al., 2021, 2025) has recently gained traction (see, for example, Baptista and Junior, 2023) as it intends to capture the discontinuity and institutional weaknesses1 characterizing the current “wave of retraction” (Mariano et al., 2021, 4) of Latin American regionalism.

However, there are also recent studies that highlight the resilience of Latin American regional organizations under stress (Nolte and Weiffen, 2021a,b) and in crisis constellations (Agostinis and Nolte, 2023; Briceño, 2024). Another study shows that Latin American regionalism has become denser, as it has grown both in scope (in terms of the respective mandates of regional organizations) and regarding the diversity of actors with decision-making power (Carneiro, 2024).

At first glance, the results of these studies seem to contradict the thesis of liquid regionalism in Latin America. However, it is also conceivable that the resilience of regional institutions is due precisely to the differentiation and/or flexibilization of their tasks and functions (in terms of a “spill-around effect”; cf. Nolte and Weiffen, 2025) without leading to a strengthening of regional institutions (e.g., with regard to the enforcement of decisions and norms). Resilience and liquidity would then be two sides of the same coin. Drawing on the European experience, Hofmann and Mérand (2012, 134–135) have put forward arguments in favor of a “variable geometry” of differentiated multilateral cooperation and “institutional elasticity,” where “member states have the flexibility to opt out of certain institutionalized policy domains or they can push for their preferred policy preferences in another institution.”

According to Mariano et al. (2021, 7) their objective “is not just to establish a new concept (liquid regionalism), but also to adjust the analysis criteria to the current reality in the Americas, thus presenting a conceptual categorization that assists in creating a better understanding of regional processes on the American continent.” The question arises as to whether the concept lives up to this claim, what adjustments and additions may be appropriate and what paths there are to “solidify” Latin American regionalism.

The article first introduces and discusses the concept of liquid regionalism. It then examines the extent to which the concept captures the current development and structure of Latin American regionalism. Subsequently, the concept of regional authority is introduced to broaden the analytical perspective. At the start, approaches to define and measure regional authority are presented. Then the article discusses different modes of contesting regional authority. Finally, a distinction is made between different types of regional authority (hard, soft and smart regional authority). The final part of the article discusses strategies and pathways to overcome fluid regionalism and contested authority, and it explores how regional institutions and regional authority can become more “solid.” This article adopts an exploratory approach, aiming to broaden the research perspective on Latin American regionalism by discussing, refining, and integrating diverse analytical concepts and approaches. Simultaneously, it integrates an empirical dimension by evaluating the extent to which these conceptual frameworks effectively capture and explain the contradictory trajectory of the current wave of Latin American regionalism.

2 Liquid regionalism in theory and practice

Against the backdrop of the crises and disruptions of Latin American regionalism in the second half of the past decade it is not surprising that Latin American regionalism has been characterized as “liquid” in contrast to “solid.” Mariano et al. (2021, 2025) introduced the concept of liquid regionalism to capture this new wave of Latin American regionalism since 2010. They distinguish “liquid regionalism” from more solid forms of regionalism, characterized by “a well-established, durable, stable and clearly delimited order, which guides the behavior of actors from the construction of beliefs and loyalties, ensuring the permanence of order itself (through the logic of reproduction of values), and the ability to adjust to changes without causing drastic disruptions” (Mariano et al., 2021, 5) This could be seen as an ideal type of regional architecture that forms the antithesis to liquid regionalism.

Liquid regionalism differs in that it does not create an “enduring order.” Rather “the meaning and purpose of regionalism is not clearly established” (Mariano et al., 2021, 5). For the authors “liquid regionalism is characterized by the low commitment of actors (especially governments and state actors), which has reinforced the idea that regional norms and structures are volatile and changeable, designed not to crystallize or perpetuate themselves.” This leads to “the creation of flexible and informal institutional structures, free of any concerns as to setting up bureaucratic structures in charge of consolidating behaviors and safeguarding memories from which the actors can guide their actions in the short-, medium- and long-term” (Mariano et al., 2021, 6).

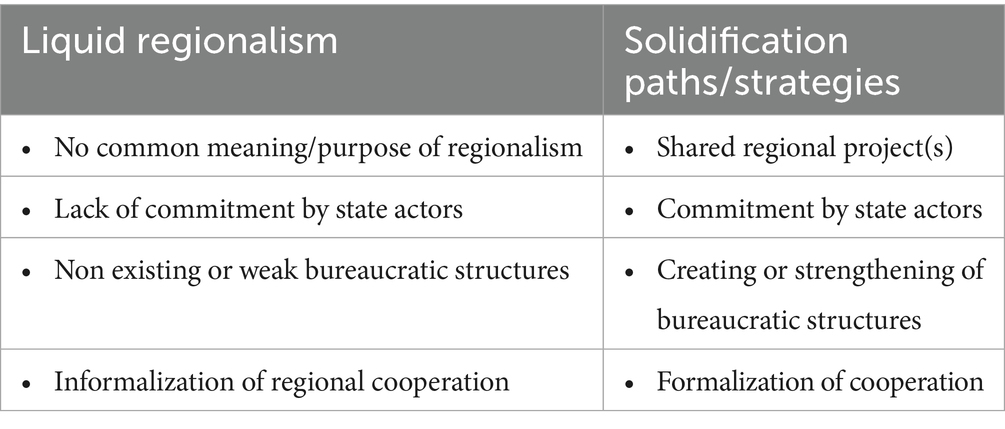

Four analytical dimensions can be derived from the preceding characterization of “liquid regionalism.”

• the meaning and purpose of regionalism which is not clearly established

• the commitment of actors (especially governments and state actors) to regionalism which is low

• regional norms and structures which are volatile and changeable

• institutional structures which are flexible and informal (no concerns as to setting up bureaucratic structures)

These dimensions can be used to examine the extent to which the characterization of the current wave of Latin American regionalism as liquid regionalism contributes to a better understanding of regional processes in the region.

According to the concept, the meaning and purpose of regionalism are not clearly established. At first glance, this is certainly true, since there is no overarching consensus among Latin American governments about the meaning and purpose of regionalism. What one can see are different, sometimes competing regional projects, which are also influenced by the power and status of the countries involved, and there are subregional projects implemented by regional organizations that define the purpose in their statutes. On this topic, the concept of liquid regionalism could be reconsidered and further developed. Often, it is less a question of the meaning and purpose of regionalism being unclear, but rather of the fact that we are dealing with partially competing and segmented regional projects that may overlap in terms of mandates and membership. A plural and multilayered regional architecture is not the result of flawed or capricious decisions, but rather the strategic outcome of conflicting interests among the governments involved (Nolte and Comini, 2016). Therefore, within the framework of liquid regionalism, a stronger focus should be placed on the competition between regional projects and the overlap of regional organizations.

With regard to the informalization of institutional structures, a contradictory picture emerges. On the one hand, informality appears to have declined since 2020. Informal regional forums (or informal intergovernmental organizations, as defined by Legler et al., 2025) such as the Lima Group and PROSUR have ceased to operate. In contrast, more institutionalized regional organizations have persisted (with the notable exception of UNASUR), and there are meetings of presidents and ministers within their formal framework.

Less institutionalized regional forums appear to face greater limitations in their functioning compared to formal regional organizations, and they attract markedly lower levels of presidential engagement. For example, after an interruption since January 2017 a presidential meeting of CELAC did not take place again until 2021, but not all presidents participated. At the CELAC summit in Kingston (San Vicente and the Grenadines) in March 2024, the presidents of Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, México, Nicaragua, Panamá, Paraguay, Perú, and Uruguay were absent and sent their foreign ministers or ambassadors. An attempt by the Honduran president to hold an extraordinary CELAC summit in January 2025 failed due to a lack of commitments by Latin American presidents to attend. At the IX CELAC summit in Tegucigalpa in April 2025 the presidents of Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panamá, Paraguay, Perú and Venezuela did not participate.

On the other hand, despite challenges to their survival and waning interest, there is evidence that informal and fluid (liquid) forms continue to play a role in Latin American regionalism. Efforts to relaunch UNASUR as a regional organization during the South American presidential summit in May 2023 culminated in the adoption of the more informal ‘Brasilia Consensus’ and its accompanying ‘roadmap’ (hoja de ruta) of October 2023, which proposed the creation of sectoral transnational networks alongside exploratory and informal ministerial meetings.

As far as the flexibility, volatility and changeability of institutional structures are concerned, the question arises as to whether this is really the case when one considers the various building blocks of Latin American regionalism. The only regional organization that disintegrated was UNASUR. From a highly legalistic perspective, some authors even claim that the organization never dissolved (Long and Suñé, 2022). Moreover, in 2023 the Brazilian, Argentine, and Colombian governments renewed their membership. However, this did not lead to any significant activity on the part of UNASUR. Two regional forums have disappeared (PROSUR and the Lima Group), but the other forums and regional organizations have not fundamentally changed in their structure and the norms they uphold.

More broadly, the question arises whether flexibility is necessarily a bad thing. The institutionalization of organizations also includes their ability to adjust to a changing environment and new challenges (Huntington, 1968, 13 called this adaptability). Furthermore, the flexibility of regional organizations can explain their resilience, as these organizations expand their activities into new fields in case of stagnation in already established areas (Nolte and Weiffen, 2025). However, this expansion (or spill-around) of activities may also be limited to mere declarations of intent (declaratory regionalism; Jenne et al., 2017). Nevertheless, in the context of a lack of consensus among governments on the goals of regional cooperation and diverging interests across policy areas, institutional elasticity and a variable geometry (Hofmann and Mérand, 2012) may be the best—and only—option.

For Mariano et al. (2021) the flexibility and informalization of institutional structures are linked to the lack of interest in establishing bureaucratic structures. However, this observation is neither new nor an exclusive feature of the current phase/wave of liquid regionalism. Already in earlier phases or waves of regionalism, authors had pointed out that Latin American regionalism is characterized by a tendency towards increasingly lighter institutional structures; and Sanahuja (2008) had introduced the concept of “light regionalism.” While the creation of supranational institutions was a fashionable theme in Latin American regionalism during the 1990s, regional governance in the first decade of the 21st century was characterized by lower institutional differentiation and the development of institutions with reduced responsibility and decision-making authority. For example, regional parliaments, previously considered an important element of integration projects, were no longer created. While the technical secretariats of MERCOSUR and CAN are not very strong (Closa and Casini, 2016), newer regional organizations (or forums) such as CELAC, ALBA, or the Pacific Alliance have no secretariats at all.

As far as the flexibility and informalization of institutional structures and the lack of bureaucratic structures are concerned, the concept of liquid regionalism remains relatively vague (Mariano et al., 2025, 56–57). In this respect, it would make sense to broaden the perspective and include, for example, research on authority in international organizations. Does “the lack of concerns setting up bureaucratic structures” refer to a general lack of bureaucratic structures (such as in the case of most regional forums), the strength (resources) of the bureaucracy (budget and personal; Engel and Mattheis, 2019; Mattheis, 2024), or the autonomy of regional bureaucracies (regarding decision making or recruitment; Parthenay, 2024)? Comparative analyses of the response of Latin American regional organizations and forums in the COVID-19 pandemic indicate that the nature of bureaucratic structures has certainly played a role regarding their performance (Castro and Nolte, 2023; Ruano and Saltalamacchia, 2021).

Mariano et al. (2021) emphasize the low commitment of actors (especially governments and state actors) as a characteristic of liquid regionalism. In doing so, they make an important point that should be further elaborated and linked to the other dimensions of liquid regionalism (regional structures and norms). Both actors and structures (and norms) must be considered together, because actors, in principle the governments, question or contest the institutions and norms and thus make regionalism “liquid.” Apparently, it is not the structures that are fluid, but it is the willingness of the actors to act within the structures and to respect and implement their norms that fluctuates. This can be the result of competing and overlapping regional projects.

Not everything is new in liquid regionalism compared to previous waves. Regional projects do not start from scratch but build on previous experiences of regional institution building. There is a path dependency, and one may ask whether the new wave of regionalism has really “intrinsic characteristics different from those of previous periods” (Mariano et al., 2021, 1). The authors of the concept of liquid regionalism themselves later seem to have doubts about this claim. In the book version, published 4 years after the original article, Mariano et al. (2025, 5, 8) argue “that Liquid Regionalism is the essence of American regionalism and has always been present” and that “that the characteristics of Liquid Regionalism are structural to the regional logic of the Americas.”

3 From liquid regionalism to liquid regional authority

The concept of liquid regionalism is a good starting point when it comes to analyzing the current wave of regionalism. However, it should be adapted and expanded to broaden the research perspective and address some of the issues raised earlier. An expanding body of literature addresses the topic of authority within international organizations, including regional organizations. The existence or strengthening of regional authority is in some ways the opposite of liquid regionalism. A more solid regionalism presupposes the emergence and consolidation of regional authority. To this end, it is necessary to analyze who challenges or contests regional authority (and in what way) and thus liquefies institutional structures.

As Zürn (2023, 33) points out “authority is a functionally differentiated form of a right to do something; it is specialized in the sense that it is limited to certain tasks and functions.” In the case of regional authority, it is limited to the region. For a regional authority to emerge and be accepted, there must therefore be regional institutions and/or actors whose influence extends beyond the nation state. According to Zürn (2023, 46) international organizations “can be seen as an institutionalized authority.” Consequently, the institutional development and functional differentiation of regional organizations should provide insights into the scope and reach of regional authority, while also indicating pathways to consolidate fluid (liquid) structures.

3.1 Identifying and measuring regional authority

When it comes to the measurement of the authority of international organizations, there are two major databases, the International Authority Database (IAD) and the Measure of International Authority (MIA) database. Both projects aim to render international authority quantifiable to the extent that it is exercised by international organizations.

The IAD defines the authority “as the grant of the right to make binding decisions and/or competent judgments that is expressed through the formal properties and attributes of an organization” (Zürn et al., 2021, 432). According to the project description the authority “is jointly constituted by two dimensions: by its autonomy and by the bindingness of its rules and decisions” which reduces “the policy discretion of member states” (Zürn et al., 2021, 432). Empirically the IAD project measures authority in terms of seven policy functions of international organizations—agenda-setting, rulemaking, monitoring, norm interpretation, enforcement, knowledge generation and evaluation—and aggregates the partial results to determine the overall authority of an international organization.

The focus of the MIA project is “on legal authority, which is institutionalized, i.e., codified in recognized rules; circumscribed, i.e., specifying who has authority over whom for what; impersonal, i.e., designating roles, not persons; territorial, i.e., exercised in territorially defined jurisdictions” (Hooghe et al., 2017, 14). In contrast to the categories of autonomy and bindingness of the IAD project the MIA project disaggregates the authority of IOs in delegation and pooling. According to the project description “delegation describes the autonomous capacity of international actors to govern,” which “depends on the extent to which IO bodies are institutionally independent of state control and the role of these bodies in IO decision making” (Hooghe et al., 2017, 23, 25). In contrast, “pooling depends on the extent to which member states collectivize decision making in one or more IO bodies, the role of such bodies in agenda setting and the final decision, and the extent to which the decisions made by these bodies are binding on member states” (Hooghe et al., 2017, 25).

Both projects are interested in long-term trends The IAD covers 34 international organizations over the period 1920–2013, and the Measure of International Authority (MIA) database includes 76 international organizations for the period 1950–2019. Thus, the Latin American wave of liquid regionalism emerging since 2010 is only partially accounted for.

The aggregated data of the IAD project show that authority of international organizations has been increasing until middle of the first decade of the 21st century (Zürn et al., 2021). The MIA project data corroborates the increase of authority of international organizations (in the period 1950–2010) but more in the dimension of delegation than in pooling (Hooghe et al., 2019, 91–96). However, “since the mid-2000s, hardly any IOs have undergone reforms of their founding treaties that would have provided for the delegation of additional competences or the pooling of more sovereignty. Nor have any new IOs been created in this period that would have acquired additional authority in new areas” (Kreuder-Sonnen and Zangl, 2024, 5). This is precisely the period in which, first, new regional organizations emerged in Latin America and, later, regional organizations went through a crisis and were paralyzed or disintegrated.

Both databases include Latin American, Caribbean and Western Hemisphere regional organizations, the IAD four (only one Latin American RO) and the MIA in total nine (five Latin American ROs). And there are only four overlaps between both databases—CAN, CARICOM, OAS, and NAFTA. The assessment of the degree of authority for these four international organizations varies significantly. Regional forums (such as CELAC), which are not regional organizations, but important for Latin American regionalism are not included. Moreover, both projects do not include UNASUR, ALBA and the Pacific Alliance. In the IAD project MERCOSUR and SICA are missing.

Hence, the question arises as to what extent the regional organizations included in both projects are representative and appropriate for an analysis of regional authority in Latin America. In this respect, both databases have limited value for the questions raised by the concept of liquid regionalism and the dimensions of analysis based on it, which does not rule out the possibility that the categories developed there can be used for future analyses of Latin American regionalism.

Against the background of the intergovernmental character of regional cooperation in Latin America and the low commitment to and insufficient implementation of formal rules characterizing liquid regionalism (and other phases of regionalism), the concepts for measuring authority in international organizations are only of limited value for the analysis of the functioning of regional organizations in Latin America, as Mariano et al. (2025, 52) point out “even though there are rules and institutions, they are not capable of conditioning the participants’ behavior.” This aligns with Malamud’s (2022, 232) observation that, in the context of Latin American regionalism, “real-existing regional institutions look very different from treaties and protocols.” Interestingly, although they have developed a broad database to determine the formal authority of international organizations, Hooghe et al. (2019, 32) also admit a central limitation: “If one expects an analysis of the formal rules to point-predict IO decision making, one is clearly asking too much.”

3.2 The exercise of regional authority

The liquidity of regional institutions also implies a liquidity of authority. With a view on “liquid authority” in global governance Krisch (2017, 249) argues “if authority can be liquid, we need to study social processes rather than formal delegation to identify, situate, and understand it. This implies that we need to shift the focus from the initial act of delegation to the development of authority over time, its perpetuation or challenge through social and institutional interactions.” Liquid regionalism and liquid regional authority imply that there are actors who exercise/uphold or contest the authority of regional institutions. When analyzing regional authority, it is essential to consider both institutions and actors, as well as the exercise and contestation of authority.

The brief overview of Latin American regionalism presented in this article demonstrates that a focus solely on the formal competences and authority of regional organizations offers an incomplete picture and may even result in analytical dead ends. To get the complete picture, it is necessary to broaden the analytical approach. First, it is important to distinguish between the lack of formal authority of regional organizations and the non-exercise of authority. When we speak of a crisis of authority, it is often not the lack of authority but the lack of the exercise of authority, or the contestation of authority. For (formal) authority to be effective, someone must claim and exercise authority.

Regional authority can be exercised by different actors: by regional intergovernmental organizations (and forums), but also by individual states or their governments. As long as there is no overarching authority with a monopoly on the use of force in the region, sovereign states and their governments remain the central actors. However, not all states are equal; there is a hierarchy in the international system and in the regional subsystems (Lake, 2009). Consequently, certain states have more possibilities to exercise authority within a region. This applies particularly to the so-called regional powers but also extends to secondary powers. However, even in the case of regional powers, a distinction must be made between their status as a regional power (with authority) and their will to exercise regional leadership (or regional authority) (Nolte and Schenoni, 2024).

Following a differentiation that was introduced by Lake (2009), it makes sense to differentiate between formal legal authority exercised in and by regional organizations and relational authority between a dominant state (or dominant states) and subordinated states based on the regional hierarchy of power and status. In practice, research on the two strands of regional authority, formal legal authority and relational authority between states, has become bifurcated. Research on legal authority primarily seeks to determine and measure its scope by analyzing the statutes of regional organizations, as demonstrated by the two previously mentioned projects and databases. In the case of relational authority, scholarly attention has primarily focused on the foreign policies of regional powers and the responses of follower states, particularly the strategies employed by secondary powers (Malamud, 2011; Schirm, 2010).

Legal authority and relational authority within a region are interrelated. Regional powers are expected to play an important role in regional organizations. And regional organizations are often instrumentalized by regional powers, or secondary powers, to assert foreign policy interests or to project power (Nolte, 2010, 2011). Powerful states, which include regional powers, can instrumentalize international institutions to exercise their authority, as Zürn (2023: 44) points out: “To the extent that the new international institutions exercise political authority, they set rules that reduce the room to maneuver for national states and govern formerly purely domestic affairs either directly or indirectly. Especially powerful states aim to use such authorities to exercise influence outside of their territory; at the same time, they often try to limit the authorities’ influence on their own affairs.”

In 21st-century Latin America, this dynamic has been most evident in the cases of Brazil and Venezuela. For a time, both countries competed for regional leadership, with Venezuela notably seeking to instrumentalize regional organizations as a means of regime boosting (Nolte, 2022a; Nolte and Mijares, 2022). On the one hand, power politics at times overshadowed the self-imposed goals set by regional organizations. On the other hand, the lack of interest of regional powers in the work of regional organizations could also undermine their authority, as it was the case of Brazil during the Temer and Bolsonaro presidencies. However, such disengagement does not necessarily affect their status (and authority) as regional powers (Nolte and Schenoni, 2024). There are good arguments for closer integration between research on comparative regionalism and the analysis of regional powers (Wehner, 2025).

Legal authority and relational authority within a region can reinforce each other. For example, regional powers can play a leading role by creating and supporting regional organizations and thereby strengthen their authority as was the case with Brazil during Lula’s first two presidencies. In this regard the leadership and authority of strong regional powers can compensate for the weak formal authority of regional organizations. The unwillingness to lead (Nolte and Schenoni, 2024) and the lack of interest of regional powers in regional organizations, on the other hand, can weaken their authority, as in the case of MERCOSUR during Bolsonaro’s presidency. However, the authority (or more precisely, the exercise of authority) by regional organizations can at times compensate for the absence of a regional leader, as in the case of SICA during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What additional examples for the exercise of regional (relational) authority by regional powers can be listed? One example is the convening of the first South American summit in Brasilia in 2000 during the presidency of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, which paved the way for the subsequent founding of UNASUR. Another example is Brazil’s influence in persuading Colombia to join UNASUR. A third example would be the revival of CELAC during Mexico’s pro tempore presidency in 2021–2022.

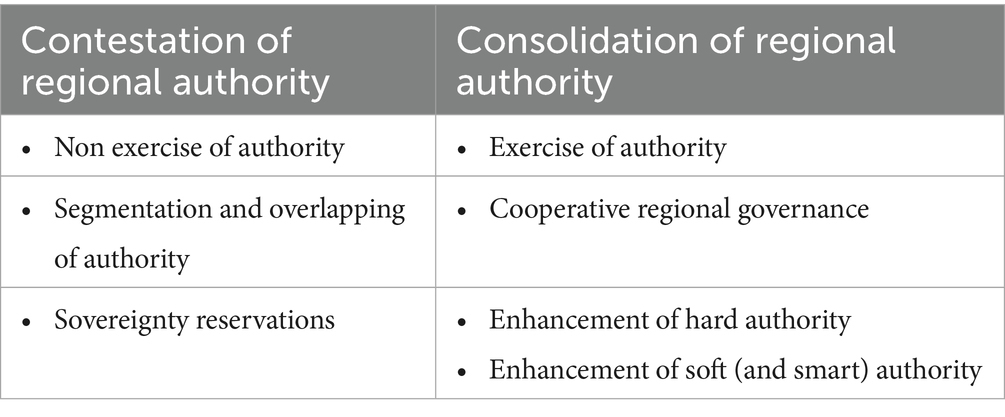

3.3 The contestation of regional authority

With regard to global institutions Krisch (2017, 245–246) notes that “the formal–legal delegation of significant powers is limited (…), and even where it exists it is frequently undermined by a lack of actual recognition or by institutional competition.” This statement applies equally to regional institutions and raises the question of how contestation of regional authority can be conceptualized, and which forms of contestation can be distinguished.

First, there is the contestation of the authority of regional powers, which can also have an impact on the authority of regional organizations: a negative impact if regional powers no longer support the authority of regional organizations; a positive impact if the loss of authority of regional powers results in more leeway for the authority of regional organizations. A clear example of the erosion of a regional power’s authority is the case of the Brazilian president’s invitation to his South American counterparts to Brasília in May 2023 to relaunch UNASUR—an initiative that ultimately resulted in a summit declaration that did not even mentions UNASUR.

Second, there is the contestation of the authority of regional organizations by other regional institutions. Overlapping of mandates and/or membership enables cross-institutional political strategies (by member countries) which can create overlapping spheres of authority und undermine the authority of regional organizations. This was the case in the conflicts between the OAS and UNASUR (Nolte, 2018).

Thirdly, there is the contestation of political authority within regional organizations by individual member countries/governments. According to the IAD project “States’ principled recognition of IO authority expresses itself in two ways: in the creation of, accession to, and continued operation of IOs; and, in that states endow them with specific competences to perform a set of policy functions in their stead” (Zürn et al., 2021, 432). Hence the authority of a regional organization becomes contested by governments in different ways, when they (1) withdraw from the regional organization (accession and continuity), as in the case of the withdrawal of Venezuela and Nicaragua from the OAS, (2) block its decision-making processes (operation), (3) reduce the policy functions (or policy portfolio; Hooghe et al., 2017) endowed to the regional organization, (4) undermine the bindingness of its rules and decisions, and (5) more general by deinstitutionalizing (Brosig and Karlsrud, 2024) and informalizing the regional organization through the bypassing of established rules of procedure and circumventing institutionalized forms of action (a topic that is central to the concept of liquid regionalism).

Hence, regional authority can be contested by different actors and at different levels, but these interact and influence each other. The contestation of the authority of a regional power can affect the authority of regional organizations, or fuel competition between regional organizations, leading to a loss of authority in them. At the same time, the loss of authority in one regional organization can create scope for expanding authority in another, when there are overlapping spheres of authority. The existence or creation/strengthening of regional authority structures is in some ways the opposite of liquid regionalism. A more solid regionalism presupposes the emergence and consolidation of regional authority.

3.4 Hard, soft, and smart authority

In a region where, as Serbin (2010, 8) notes, there exists “an obsession with the norms of sovereignty and independence”, and where dynamics oscillate between competition for leadership and a vacuum of leadership, establishing authority in or through regional organizations proves particularly challenging. This context raises the question of whether it is meaningful to distinguish between different types of international authority. Regarding international power, Nye (2004) introduced the distinction between hard power and soft power, he later added the concept of smart power (Nye, 2008). Hard power is based on coercion and incentives, soft power is based on attraction and co-optation, and smart power is based on the right mix of both.

Based on the differentiation of power, a distinction could also be made between hard authority, soft authority, and smart authority in regional organizations (and forums). Following this idea, the different dimensions for measuring authority of the IAD project could be linked to different types of authority. Agenda setting and knowledge generation would correspond to soft authority, and rulemaking and enforcement to hard authority. When it comes to monitoring, norm interpretation, and evaluation, it depends on the design and the configuration whether they are classified as hard or soft authority.

As a result, the distinction between hard and soft authority could facilitate the interpretation of the authority profile of regional organizations. According to the IAD project, the authority values for the CAN are high in terms of agenda setting, norm interpretation and knowledge generation, in the mid-range for rule making and monitoring, and low for enforcement and evaluation (Zürn et al., 2021, 437). Regarding the distinction between hard and soft authority, CAN would be strong in soft authority but have less hard authority. This is one possible way to make the distinction between hard and soft authority analytically useful for the study of regional organizations. However, depending on the research perspective, alternative approaches may be more appropriate.

Klabbers (2023) equates soft authority with epistemic authority and recalls the longstanding debate on “soft law” in international law. From this perspective, hard authority can therefore be understood as the exercise of formal authority—usually by governments—through and within regional organizations. In contrast, soft authority is closely linked to the concept of epistemic authority, understood as the authority of experts grounded in knowledge and their capacity to provide interpretations of complex issues. Epistemic authority, a concept introduced by Zürn (2018 52–53), stands in contrast to political authority, which refers to the authority to make binding decisions.

As previously noted, authority within Latin American regionalism is often contested. In the context of soft authority, different forms of contestation can be identified. These include the imposition of hard authority, whereby the independent agency of experts is constrained, their decisions are politically overridden or disregarded, or expert knowledge is more broadly devalued in politics and society.

What about smart authority? The concept could be applied to the indirect or mediated exercise of authority by regional institutions, for example through the mechanism of orchestration, a concept that has recently been applied in the analysis of Latin American regional organizations and development banks (Legler, 2021; Palestini, 2024). According to Abbott et al. (2021, 140–141) in the case of orchestration an international organization (the orchestrator) works through a second actor (the intermediary) to influence a third actor in pursuit of its governance goals. It is an indirect and smart mode of governance; one might call it also smart authority. The overlap among regional organizations—in both mandates and membership—creates opportunities for orchestration, allowing actors to coordinate initiatives across institutional boundaries. To a certain extent, regional powers can also exercise smart authority if they do not assert their interests vis-à-vis other governments directly, but rather through their influence in regional organizations.

4 Overcoming liquid regionalism and contested authority

The concept of liquid regionalism and the analytical dimensions it contains offer a good starting point for the study of the current phase of Latin American regionalism. Based on the dimensions encompassed by the concept of liquid regionalism, pathways can be identified that contribute to rendering regionalism more “solid.” However, it is also necessary to critically assess how realistic it is to expect progress in the medium term.

In the current political climate, it is unlikely that shared regional project(s) will develop or progress in Latin America. The political and economic orientations of the governments are too different. There are clearly authoritarian regimes, electoral democracies (with more or less pronounced authoritarian tendencies), and liberal democracies. In such a constellation, the likelihood of closer political cooperation to advance joint regional projects is limited. The approaches to economic policy also vary widely, between an ultra-liberal economic policy and an economic policy in which the state still plays an important role, which makes economic integration more difficult; especially as intra-regional trade is low. Setbacks cannot be ruled out either, for example if the MERCOSUR member states begin to negotiate free trade agreements with third countries separately or make MERCOSUR’s common external tariff more permeable.

Furthermore, Latin America is a region exposed to the political and economic influence of external actors, which has a negative impact on the cohesion of the region and regional cooperation. Latin American governments have not succeeded in developing a common strategy to counter China’s growing economic and political influence in the region, and no unified and common position is emerging in the face of Donald Trump’s aggressive trade and migration policy. Each government is trying to find its own arrangement with the US government. In conclusion, the prospects for new shared regional projects appear rather bleak in the medium term. Hopes for a revival of Latin American regionalism—sparked by the election of several left-leaning presidents between 2018 and 2022, most notably the return of President Lula to power in Brazil (2022)—proved short-lived and ultimately failed to meet expectations (Nolte, 2022b, 2025).

Given the historical trajectory and underlying “DNA” of Latin American regionalism, the creation of new comprehensive bureaucratic structures appears rather unlikely. In this respect, even better use of existing bureaucratic structures would be a step forward. This is the case when the presidents and ministers of the member states of regional organizations (and forums) meet regularly within the framework of the existing decision-making bodies and the existing bureaucratic structures are kept functioning so that they can work in their areas of responsibility.

As already mentioned, the informalization of regional cooperation is currently less of a problem. Often, the primary challenge lies not in formalizing informal modes of cooperation, but in utilizing and consolidating existing formal structures. In this context, it is not the absence or liquidity of regional structures that defines Latin American regionalism, but rather the limited instrumentalization of those that already exist. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between the lack of formal authority of regional bodies and the lack of exercise of authority, or the blockade of authority.

For formal authority to be effective, it must be actively claimed or exercised. While institutions undoubtedly contribute to rendering regionalism more “solid,” they must also operate. The case of UNASUR illustrates this point: as long as the position of secretary general was filled, the organization managed to persist—even under adverse conditions. When the governments could not agree on the election of a new secretary general, i.e., when this institution did not function, UNASUR became paralyzed and slowly disintegrated.

While the concept of liquid regionalism highlights that the meaning and purpose of regionalism are not clearly defined, it could more fully address the fact that multiple, sometimes competing and segmented regional and sub-regional projects coexist—often overlapping in both mandates and membership. As a result, authority at the regional level is not concentrated but dispersed and divided in “loosely coupled spheres of authority,” which “can be defined as fields that are governed by one or more authorities” (Zürn, 2018, 56). Overlapping enables cross-institutional political strategies—often referred to as “chessboard politics”—which can undermine authority within regional organizations. And it creates coordination problems between different “spheres of authority,” which can, however, be mitigated or overcome within the framework of cooperative regional governance (Nolte, 2016). At the same time, overlapping makes possible a variable geometry of regional cooperation and strategies of orchestration.

Another major stumbling block for more solid regional structures are the sovereignty reservations of Latin American governments (the “foundational taboo” of Latin American regionalism; Mariano et al., 2025, 44), which prefer “sovereignty-boosting” to more integration and the creation of stronger regional institutions. In this respect, there can be no doubt that “regionalism light” limits the possibilities of establishing and exercising hard authority.

The characteristics of Latin American regionalism listed above—segmentation and overlapping, sovereignty reservations, and the non-exercise of authority—can be seen as different dimensions of the contestation of regional authority. Liquid regionalism and the contestation of regional authority capture different, intersecting and complementary aspects of Latin American regionalism. The “solidification” of Latin American regionalism supposes the consolidation of regional authority which could be hard, soft and smart authority.

Authority can be exercised by regional powers directly or indirectly through regional organizations. Due to the intergovernmental nature of Latin American regionalism, it can also be exercised collectively by member governments in regional organizations and forums, depending on the formal powers granted to these institutions. At present, both the willingness and the capacity of regional powers (or secondary powers) to exercise regional authority—whether directly or indirectly—appear to be limited, particularly in light of the uncertainty over whether there are sufficient followers to endorse or align with such leadership (Malamud, 2011; Schirm, 2010). The exercise of collective authority by regional organizations or forums depends on the existence and articulation of common interests and is hampered by ideological differences between governments.

The segmentation and overlapping of regional authority can be overcome by cooperative regional governance, which has been defined (Nolte, 2016, 10) “as a regional architecture that includes a central regional organization that is at least loosely connected with other regional ones. The core norms supported by the central institution are not contested. It is not necessary that all major actors support the same regional organizations, but only that they cooperate with and support the central regional organization and the regional project related to it. Thus, overlapping membership (including associated members)—as an element of norm diffusion and consensus building—is combined with a tendency to divide tasks between existing organizations.” The institutional overlapping among regional organizations within the framework of cooperative regional governance broadens the scope for orchestration and enables a variable geometry of regional cooperation.

There is no central regional organization encompassing Latin America and the Caribbean as a whole—only a regional forum, CELAC, which partially competes with the Pan-American Organization of American States (OAS). Likewise, there is currently no central regional organization for South America, a role that UNASUR temporarily fulfilled in the past. While some South American governments (Argentina under Alberto Fernández, Brazil, and Colombia) declared their rejoining of UNASUR, others never formally withdrew, some did not rejoin (Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Uruguay), and still others can be classified as inactive or uninterested (such as Peru and Argentina under Milei). Furthermore, UNASUR did not demonstrate any significant activities that would allow it to be classified as an active regional organization. Therefore, Latin America and South America are characterized by segmented regional governance, as key state actors support different regional organizations and promote different regional projects within a (macro-)region. Segmented regional governance might be mitigated and partially overcome through the creation of intergovernmental or transnational policy networks, which may vary in their degree of formalization. This pathway is outlined for South America in the so-called “Brasilia Consensus” of May 2023 and its accompanying roadmap from October 2023, which envision flexible, issue-based, and sectoral cooperation among governments—without proposing the establishment of new regional organizations.

Due to the strong reservations to cede sovereignty, it is unlikely that new regional institutions endowed with hard authority will emerge in the medium term, or that the formal authority of existing regional organizations will be significantly reinforced. Within these constraints, even the effective exercise of formal authority already vested in regional organizations would represent a significant step forward. Given that hard authority is difficult to establish, it makes sense to consider how other forms of regional authority, such as soft and smart authority, can be developed and consolidated to strengthen regional authority overall.

As mentioned before, soft authority is closely linked to the concept of “epistemic authority,” the authority of experts based on knowledge. The sovereignty-defending and boosting character of Latin American regionalism excludes the “pooling of sovereignty” and limits the “delegation of authority” according to the definition of the MIA project (for the concepts, see Lenz and Marks, 2016). Both are not parts of the “DNA” of Latin American regionalism.

However, the inability to achieve a “pooling of sovereignty” does not preclude the “pooling of expertise” or the development of soft authority. The significance of “soft” or “epistemic” authority varies depending on the nature of regional cooperation and integration: it tends to be lower in more political and multipurpose regional projects, and higher in technical or functionally oriented projects.

Faced with the problem of politically induced setbacks for regional cooperation in Latin America some authors (Actis and Malacalza, 2021; Tussie, 2023) have proposed a more technical, sectoral, and pragmatic approach to regional cooperation (a “technical-scientific multilateralism”; Rodrigues and Kleiman, 2020; Legler, 2021), with the aim of better insulating regional projects from the spillover of political conflicts. Such a technocratic turn in regional cooperation (referred to as “technoregionalism” by Castro-Silva and Quiliconi, forthcoming) would elevate the significance of epistemic (or soft) authority.

From a broader perspective this approach can be situated in a tradition of political thinking about international cooperation that can be summarized under the analytical concept of “technocratic internationalism,” which refers to a programmatic intellectual attitude that combines cross-border cooperation and expert governance (Steffek, 2021). As far as the technocratic approach is concerned, it is worth going back to the writings of Mitrany and his “functionalist approach” (Nolte, 2024). Mitrany was very skeptical about the creation of supranational bodies and overcoming the nation state. His strategy aimed at perforating the nation state without overcoming it (at least in the medium term), which can also be described as a strategy with a focus on soft authority exercised by experts and technocrats.

The development of soft authority in Latin American regionalism requires the establishment of transnational technical bodies or networks endowed with a certain degree of bureaucratic autonomy, enabling them to exercise agency whenever their functional area of competence is affected—as was the case with public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such technical bodies or networks may draw support from a functional constituency—a term coined by Mitrany (1965)—consisting of actors who either benefit from their activities or are invested in sustaining their work. Development banks that provide funding for the activities of technical bodies can be considered part of the functional constituency. Such technocratic agency—or soft authority—supported by a functional constituency can partially compensate for the lack of political leadership (and the will to exercise it) and the absence of hard authority in regional cooperation, thereby enhancing the resilience of regional institutions.

Functional constituencies play a crucial role in reinforcing soft authority by providing legitimacy, support, and continuity to technocratic actors and institutions. The emergence of a functional constituency depends on several key prerequisites. First, there must be an original political mandate that authorizes experts or technocrats to operate within a specific policy area relevant to the constituency. Second, once this mandate is granted, these actors must be able to act with a degree of autonomy and be shielded from political conflicts that are unrelated to their functional domain. Third, experts or technocrats should develop a sense of responsiveness toward their societal target group—that is, the constituency whose interests and needs they are expected to address and represent.

This section introduced new concepts such as pooling of expertise, soft authority, smart authority, and functional constituencies that warrant further clarification and empirical testing to assess their analytical utility. To advance this research agenda, it is particularly valuable to engage with recent scholarship on transnational networks—especially within the Pacific Alliance (Castro-Silva, 2022, 2023, 2025)—as well as studies on regulatory governance (Bianculli, 2021), technical-sectoral cooperation, notably in infrastructure development (Agostinis and Palestini, 2021, 2024), and recruitment patterns within regional bureaucracies (Parthenay, 2024).

5 Conclusions and outlook

Liquid regionalism offers a valuable analytical lens for understanding the structural challenges Latin American regionalism faces today and for exploring potential pathways toward greater institutional solidity. The analytical concept highlights structural deficits and constraints inherent in Latin American regionalism. However, it tends to overlook the potential benefits or positive externalities associated with liquid regional structures. Institutional flexibility makes regionalism more resilient and can facilitate the adaptation to a changing environment and new challenges. “Liquidity” represents both a challenge and a dynamic feature of Latin American regionalism. While it places limits on the institutional design of regional cooperation, it also enhances the adaptability and resilience of regional projects, enabling their continuous transformation—though not necessarily leading to their institutional solidification.

Despite its analytical strength in capturing various facets of Latin American regionalism, the concept of liquid regionalism leaves certain elements underexplored, such as the competition between regional projects and actors, the overlapping of regional organizations and forums, the lack of exercise and the contestation of regional authority. It is therefore worthwhile to broaden the analytical scope of liquid regionalism by incorporating insights from research on authority and the contestation of authority in international organizations.

The article introduces the concept of soft authority which integrates well with the concept of liquid regionalism. While enhancing and consolidating hard authority in Latin American regionalism may prove challenging, advancing soft authority appears more feasible. In this sense, soft authority, grounded in transnational and trans-governmental technical bodies and networks, may serve as a mechanism to make liquid regionalism more solid and resilient. Moreover, soft authority aligns well with the technocratic turn in Latin American regionalism.

By broadening the analytical perspective and incorporating new conceptual tools such as soft and smart authority the article explores potential avenues for solidifying Latin American regionalism even under adverse conditions. In response to the central theme of this special issue, one might ask to what extent Latin American regionalism—characterized by the notion of liquid regionalism—is equipped to respond to the challenges posed by a period of polycrisis. There is no clear-cut answer to that question. While political disunity and the lack of supranational regional bodies make it difficult for Latin American governments to articulate a common response to exogenous induced stress, the fluidity or flexibility of regional structures can facilitate responses to new challenges and the integration of new topics in the regional agenda.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DN: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Other authors (Legler et al., 2025) introduced the concept of informal intergovernmental organizations (IIGOs) to capture the fluidity and informality of Latin American regional organizations.

References

Abbott, K., Snidal, D., Genschel, P., and Zangl, B. (2021). “Orchestration: global governance through intermediaries” in The spectrum of international institutions. An interdisciplinary collaboration on global governance. eds. K. W. Abbott and D. Snidal (London and New York: Routledge), 140–171.

Actis, E., and Malacalza, B. (2021). Las políticas exteriores de América Latina en tiempos de autonomía líquida. Nueva Soc. 291, 114–126.

Agostinis, G., and Nolte, D. (2023). Resilience to crisis and resistance to change: a comparative analysis of the determinants of crisis outcomes in Latin American regional organisations. Int. Relat. 37, 117–143. doi: 10.1177/00471178211067366

Agostinis, G., and Palestini, S. (2021). Transnational governance in motion: regional development banks, power politics, and the rise and fall of South America’s infrastructure integration. Governance 34, 765–784. doi: 10.1111/gove.12529

Agostinis, G., and Palestini, S. (2024). “Infrastructure. Explaining the divergent experiences of Central and South America” in South American policy regionalism. Drivers and barriers to international problem solving. eds. L. E. Armijo, M. Fraundorfer, and S. D. Rhodes (New York: Routledge), 107–123.

Albert, M. J. (2024). Navigating the polycrisis: mapping the futures of capitalism and the earth. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

Babic, L. (2020). Let’s talk about the interregnum: Gramsci and the crisis of the liberal world order. Int. Aff. 96, 767–786. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiz254

Baptista, J. V. D. M., and Junior, N. G. (2023). From post-hegemonic regionalism to the liquid: an assessment of social participation in Mercosur. Pensam. Propio 28, 14–40.

Bianculli, A. (2021). “Regulatory cooperation and international relations” in Oxford research encyclopedia of international studies. https://oxfordre.com/internationalstudies/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.001.0001/acrefore-9780190846626-e-658

Briceño, R. J. (Ed.) (2024). El regionalismo latinoamericano: entre la crisis y la resiliencia. Ciudad de México: Ediciones Eón.

Brosig, M. (2025). From neologism to promising research agenda? The global polycrisis and IR. Int. Relat. :00471178251333294. doi: 10.1177/00471178251333294

Brosig, M., and Karlsrud, J. (2024). How ad hoc coalitions deinstitutionalize international institutions. Int. Aff. 100, 771–789. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiae009

Carneiro, C. L. (2024). Regional governance in Latin America: the more the merrier? Rev. Bras. Polit. Int. 67:e004. doi: 10.1590/0034-7329202400104

Castro, R., and Nolte, D. (2023). El covid-19 y la crisis del regionalismo latinoamericano: lecciones que pueden ser aprendidas y sus limitaciones. Relac. Int. 52, 135–152. doi: 10.15366/relacionesinternacionales2023.52.007

Castro-Silva, J. (2022). Difusión y redes en la cooperación regional: la institucionalidad comercial de la Alianza del Pacífico. Colomb. Int. 109, 31–58. doi: 10.7440/colombiaint109.2022.02

Castro-Silva, J. (2023). The deepening of the Pacific Alliance's commercial agenda: the role of policy networks in regulatory governance. Lat. Am. Policy 14, 91–108. doi: 10.1111/lamp.12281

Castro-Silva, J. (2025). La gobernanza regional compleja del comercio electrónico latinoamericano: una perspectiva comparada de la Alianza del Pacífico, la Comunidad Andina y el Mercosur. Colomb. Int. 121, 155–186. doi: 10.7440/colombiaint121.2025.06

Castro-Silva, J., and Quiliconi, C. (forthcoming). “Latin American regionalism between resilience and crisis” in Elgar encyclopedia of Latin American politics (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Closa, C., and Casini, L. (2016). Comparative regional integration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Engel, U., and Mattheis, F. (Eds.) (2019). The finances of regional organizations in the global south: follow the money. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Hofmann, S., and Mérand, F. (2012). “Regional organizations à la carte: the effects of institutional elasticity” in International relations theory and regional transformation. ed. T. V. Paul (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 133–157.

Hooghe, L., Lenz, T., and Marks, G. (2019). A theory of international organization. A postfunctionalist theory of Governance,Volume IV. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Lenz, T., Bezuijen, J., Ceka, B., and Derderyan, S. (2017). Measuring international authority. A postfunctionalist theory of governance, volume III. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huntington, S. P. (1968). Political order in changing societies. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Jenne, N., Schenoni, L. L., and Urdinez, F. (2017). Of words and deeds: Latin American declaratory regionalism, 1994–2014. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 30, 195–215. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2017.1383358

Katsikas, D., Tedesco Lins, M. A. D., and Ribeiro Hoffmann, A. (Eds.) (2025). Finance, growth and democracy: connections and challenges in Europe and Latin America in the era of permacrisis. Cham: Springer.

Klabbers, J. (2023). “Soft authority in global governance” in Research handbook on soft law. eds. M. Eliantonio, E. Korkea-aho, and U. Mörth (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing), 162–176.

Kreuder-Sonnen, C., and Zangl, B. (2024). The politics of IO authority transfers: explaining informal internationalisation and unilateral renationalisation. J. Eur. Public Policy 32, 954–979. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2024.2325008

Krisch, N. (2017). Liquid authority in global governance. Int. Theory 9, 237–260. doi: 10.1017/S1752971916000269

Legler, T. (2021). Presidentes y orquestadores. La gobernanza de la pandemia de COVID-19 en las Américas. Foro Int. 244, 333–385. doi: 10.24201/fi.v61i2.2833

Legler, T., Martins, J. P., and Iniestra, A. (2025). The untold story: informal intergovernmental organisations in Latin America. Third World Q., 1–20. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2025.2470999

Lenz, T., and Marks, G. (2016). “Regional institutional design: delegation and pooling” in Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism. eds. T. Börzel and T. Risse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 513–537.

Long, G., and Suñé, N. (2022). Hacia una nueva Unasur. Vías de reactivación para una integración suramericana permanente. Washington: Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR).

Malamud, A. (2011). A leader without followers? The growing divergence between the regional and global performance of Brazilian foreign policy. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 53, 1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-2456.2011.00123.x

Malamud, A. (2015). “Interdependence, leadership and institutionalization: the triple deficit and fading prospects of Mercosur” in Limits to regional integration. ed. S. Dosenrode (Farnham: Ashgate), 163–178.

Malamud, A. (2022). “Regionalism in the Americas: segmented, overlapping, and sovereignty-boosting” in Handbook on global governance and regionalism. eds. J. Rüland and A. Carrapatoso (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 230–247.

Mariano, K. L. P., Bressan, R. N., and Luciano, B. T. (2021). Liquid regionalism: a typology for regionalism in the Americas. Rev. Bras. Polit. Int. 64:e004. doi: 10.1590/0034-7329202100204

Mariano, K. L. P., Bressan, R. N., and Luciano, B. T. (2025). Liquid regionalism in the Americas. an analysis of contemporary regional developments. Cham: Springer.

Mattheis, F. (2024) Regional organizations and their resources, Handbook of regional cooperation and integration P. LombaerdeDe Cheltenham Edward Elgar Publishing 431–441.

Mitrany, D. (1965). The prospect of integration: federal or functional. J. Common Market Stud. 4, 119–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.1965.tb01124.x

Nolte, D. (2010). How to compare regional powers: analytical concepts and research topics. Rev. Int. Stud. 36, 101–126. doi: 10.1017/026021051000135X

Nolte, D. (2011). “Regional powers and regional governance” in Regional powers and regional orders. eds. N. Godehardt and D. Nabers (London: Routledge), 49–67.

Nolte, D. (2016). “Regional governance from a comparative perspective” in Economy, politics and governance challenges. ed. V. M. González-Sánchez (New York: Nova Science Publishers), 1–16.

Nolte, D. (2018). Costs and benefits of overlapping regional organizations in Latin America: the case of OAS and UNASUR. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 60, 128–153. doi: 10.1017/lap.2017.8

Nolte, D. (2022a). “From UNASUR to PROSUR. Institutional challenges to consolidate regional cooperation” in South American cooperation: regional and international challenges in the post-pandemic. eds. M. Deciancio and C. Quiliconi (New York: Routledge), 113–129.

Nolte, D. (2022b). Auge y declive del regionalismo latinoamericano en la primera marea rosa: lecciones para el presente. Ciclos Hist. Econom. Soc. 29, 3–26. doi: 10.56503/CICLOS/Nro.59(2022)pp.3-26

Nolte, D. (2024). “Reintegrando el funcionalismo al estudio del regionalismo latinoamericano: perspectivas y limitaciones” in La integración regional ante nuevas perspectivas de cambio. eds. E. Vieira-Posada and L. F. Vargas A (Bogotá: Ediciones Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia), 31–55.

Nolte, D. (2025). “New regional dynamics in Latin America or old wine in new bottles?” in Latin America in the new world (dis)order. eds. P. Birle and C. Zilla (London and New York: Routledge), 28–43.

Nolte, D., and Comini, N. (2016). UNASUR: Regional Pluralism as a Strategic Outcome. Contexto Int. 38, 545–565. doi: 10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380200002

Nolte, D., and Mijares, V. M. (2022). Unasur: an eclectic analytical perspective of its disintegration. Colomb. Int. 111, 83–109. doi: 10.7440/colombiaint111.2022.04

Nolte, D., and Schenoni, L. L. (2024). To lead or not to lead: regional powers and regional leadership. Int. Polit. 61, 40–59. doi: 10.1057/s41311-021-00355-8

Nolte, D., and Weiffen, B. (Eds.) (2021a). Regionalism under stress: Europe and Latin America in comparative perspective. London and New York: Routledge.

Nolte, D., and Weiffen, B. (2021b). How regional organizations cope with recurrent stress: the case of South America. Rev. Bras. Polit. Int. 64:e006. doi: 10.1590/0034-7329202100206

Nolte, D., and Weiffen, B. (2025). The resilience of Latin American regionalism: a neofunctionalist perspective. Polit. Vierteljahr. 66, 697–718. doi: 10.1007/s11615-024-00571-w

Palestini, S. (2024). Orchestrating regionalism: the Interamerican Development Bank and the Central American electric system. Rev. Policy Res. 41, 329–346. doi: 10.1111/ropr.12389

Parthenay, K. (2024). The Agency of the Global South’s regional organizations through the institutionalization of staff recruitment. Glob. Stud.Q. 4:ksae009. doi: 10.1093/isagsq/ksae009

Quiliconi, C., and Salgado, R. (2017). Latin American integration: regionalism à la carte in a multipolar world? Colomb. Int. 92, 15–41. doi: 10.7440/colombiaint92.2017.01

Rodrigues, G., and Kleiman, A. (2020). COVID-19: ¿una nueva oportunidad para el multilateralismo? For. Aff. Latinoam. 20, 36–43.

Ruano, L., and Saltalamacchia, N. (2021). Latin American and Caribbean regionalism during the COVID-19 pandemic: saved by functionalism? Int. Spectator 56, 93–113. doi: 10.1080/03932729.2021.1900666

Sanahuja, J. A. (2008). “Del regionalismo abierto al regionalismo posliberal. Crisis y cambio en la integración regional en América Latina” in Anuario de la Integración Regional de América Latina y el Gran Caribe 7. eds. L. Martínez Alfonso, L. Peña, and M. Vazquez (Buenos Aires: CRIES), 11–54.

Schirm, S. A. (2010). Leaders in need of followers: emerging powers in global governance. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 16, 197–221. doi: 10.1177/1354066109342922

Serbin, A. (2010). Regionalismo y soberanía nacional en América Latina: los nuevos desafíos. Buenos Aires: CRIES (Documentos CRIES 15).

Steffek, J. (2021). International organization as technocratic utopia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tussie, D. (2023). “The promise of active-non-alignment and its intersection with post-hegemonic regionalism” in Latin American foreign policies in the New World order. The active non-alignment option. eds. C. Fortin, J. Heine, and C. Ominami (London and New York: Anthem Press), 201–214.

Wehner, L. (2025). “Regional powers and comparative regionalism” in Handbook of international relations. ed. C. G. Thies (Cheltenham: Edgar Elgar), 254–270.

Zürn, M. (2018). Theory of global governance. Authority, legitimacy and contestation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zürn, M. (2023). “Authority in International Relations: contracted, inscribed, or reflexive?” in Rule in international politics. eds. C. Daase, N. Deitelhoff, and A. Witt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 33–60.

Keywords: Latin American regionalism, liquid regionalism, regional authority, hard authority, soft authority, smart authority, comparative regionalism, functional constituency

Citation: Nolte D (2025) Latin America: liquid regionalism and contested regional authority. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1682061. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1682061

Edited by:

António Raimundo, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Paula Ruiz Camacho, Universidad Externado de Colombia Facultad de Derecho, ColombiaJonatan Badillo Reguera, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Nolte. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Detlef Nolte, ZGV0bGVmLm5vbHRlQGdpZ2EtaGFtYnVyZy5kZQ==

Detlef Nolte

Detlef Nolte