- Southeast Asia Disaster Prevention Research Initiative (SEADPRI), Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, UKM, Bangi, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

Malaysia’s 2006 ratification of the UNESCO International Convention against doping in sport emphasized its commitment to advancing clean sport through robust national legal and policy frameworks. This review critically evaluates Malaysia’s subsequent implementation of the convention, specifically evaluating the establishment and operational role of the Anti-Doping Agency of Malaysia (ADAMAS), the alignment of national anti-doping rules with the World Anti-Doping Code, and the engagement of key governmental and sports institutions. Employing a systematic review methodology, the study synthesizes and analyses legislative texts, official reports, longitudinal testing data, and recent enforcement cases to evaluate the nation’s progress. The paper highlights significant national achievements, including expanded out-of-competition testing, the establishment of structured disciplinary procedures, and growing public awareness initiatives. Nevertheless, persistent challenges remain, notably a reliance on foreign laboratories, an over-reliance on urine-based testing, inherent resource limitations, and inconsistent compliance among national sports associations. The review concludes by proposing targeted recommendations designed to strengthen national anti-doping capacity, promote sustainable practices, and reinforce Malaysia’s crucial position as a regional advocate for clean sport.

1 Introduction

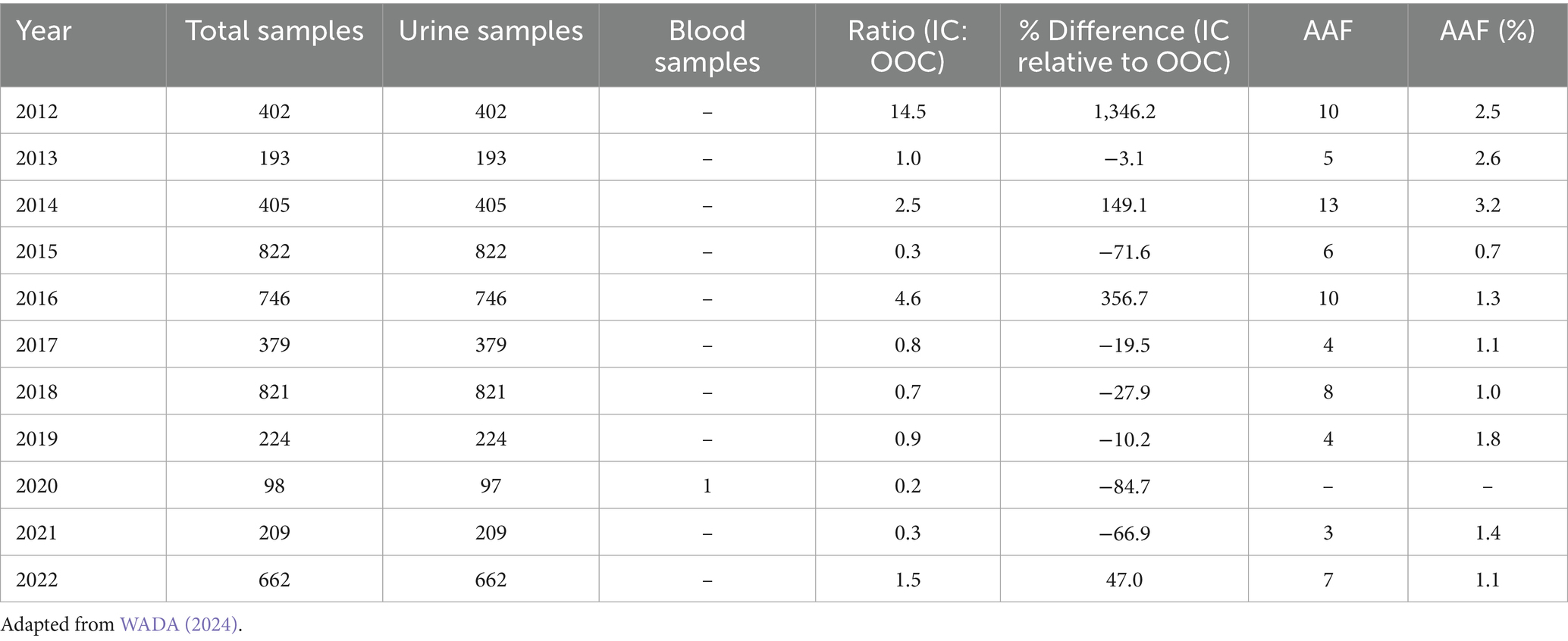

Doping in sport represents a persistent threat not only to athlete health but also to the fundamental principles of fair play and integrity that define athletic competition. While this is a global issue, Malaysia has faced its own significant challenges with the misuse of performance-enhancing drugs, demonstrating that the nation is not immune to this problem. High-profile cases have occasionally brought the issue to the forefront, such as the 8-month suspension of badminton star Lee Chong Wei in 2015 for an anti-inflammatory substance violation (Hider, 2015). More systemic issues have been observed in sports like weightlifting, which saw multiple athletes test positive for anabolic steroids at the 2022 SUKMA Games (The Malaysian Insight, 2022; TheVibes, 2022). These incidents, alongside others like the stripping of a national diver’s SEA Games gold medals in 2017 due to a stimulant found in a slimming product (FMT, 2017; ADAMAS, 2025a), highlight the varied and ongoing nature of doping threats in Malaysian sports. While anti-doping tests consistently reveal a low percentage of violations from 2012 to 2022 (peaking at 3.2% of 405 samples in 2014) (ADAMAS, 2025a; WADA, 2025a) the steady presence of adverse analytical findings (AAFs) confirms a persistent underlying issue that requires a robust national response.

The primary body tasked with spearheading this response is the ADAMAS, the nation’s designated National Anti-Doping Organization (NADO) established in 2007. ADAMAS is responsible for implementing a national anti-doping program aligned with the World Anti-Doping Code, which includes conducting in-competition (IC) and out-of-competition (OOC) testing, managing test results, investigating potential violations, and delivering anti-doping education to athletes and support personnel (ADAMAS, 2025a). However, its effectiveness is impacted by significant constraints. Unlike fully independent NADOs in other countries, ADAMAS operates directly under the Ministry of Youth and Sports and is not yet formally enshrined in a standalone act of Parliament, a status that presents foundational challenges to its autonomy, authority, and resources (SCOOP, 2024a). Consequently, Malaysia requires deliberate legislative action by Parliament to translate international convention obligations into enforceable domestic law, an authority rooted in Article 74 of the Federal Constitution (Hamid and Sein, 2006).

In response to the global doping threat, the international community developed a regulatory framework spearheaded by the UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport, the primary legally binding instrument compelling governments to take concrete action (UNESCO, 2005). By complementing the World Anti-Doping Code, the Convention aims to harmonise anti-doping policies globally, obligating signatory nations to restrict access to prohibited substances, support doping controls, and promote education and research. Malaysia demonstrated its commitment to this global effort by ratifying the Convention in 2006, formally pledging to align its national policies with these international standards.

While Malaysia’s ratification of the UNESCO Convention is well-documented, a significant research gap exists in the critical, long-term evaluation of its domestic implementation. Most discussions focus on the legal act of ratification, with fewer comprehensive analyses of the subsequent operational effectiveness and systemic vulnerabilities faced by the national anti-doping framework. To address this gap, this systematic review seeks to provide a comprehensive evaluation of Malaysia’s anti-doping framework by answering the following key research questions (RQ):

1. What are the trends in doping control in Malaysia from 2012 to 2022, specifically concerning the volume of IC vs. OOC testing and AAFs?

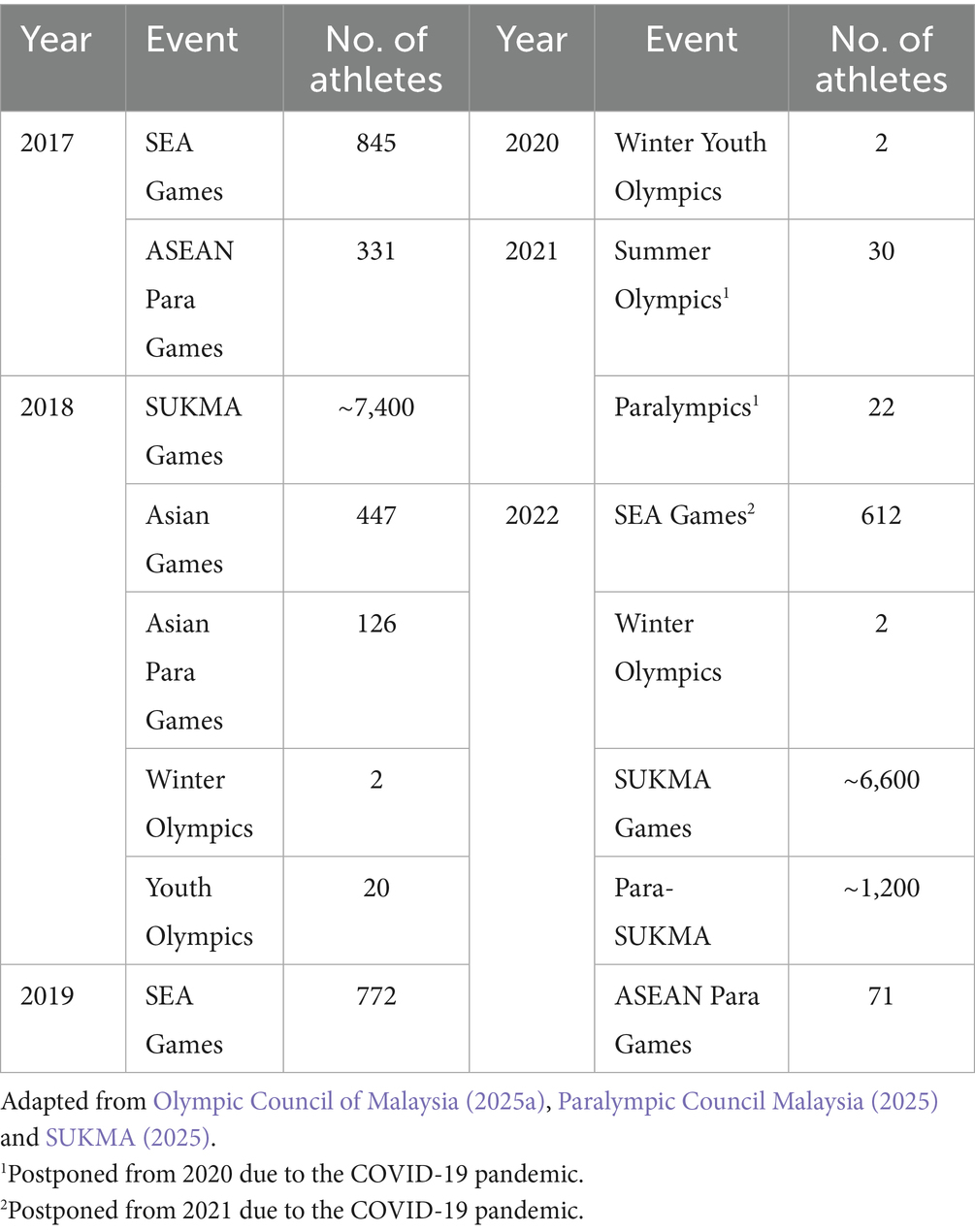

2. What is the ratio of doping samples collected to the number of athletes participating in international and major national sports events from 2017 to 2022?

3. How does Malaysia’s testing volume and strategy in 2022 compare with other NADOs?

4. What are the recent established procedures for results management, hearings, and appeals within Malaysia’s anti-doping framework?

5. What are the core strategies and target audiences of Malaysia’s anti-doping education and awareness initiatives?

6. What are the documented strengths, resource constraints, and key vulnerabilities affecting the implementation of the national anti-doping program?

The significance of this study is threefold. First, it provides evidence-based recommendations to inform national policymakers, ADAMAS, and the Ministry of Youth and Sports in strengthening Malaysia’s legal and operational anti-doping framework. Second, it contributes to the broader academic discourse on sports law and policy implementation, particularly within Malaysia’s dualist legal system. Finally, by offering a transparent critique, this paper assesses how the Convention’s international obligations have been translated into effective national action, ultimately addressing the critical question of what it truly means to move beyond ratification.

The following section will explain the methodology of this systematic review, followed by a brief description of Malaysia’s anti-doping architecture and finally addressing all the 6 RQs in section 4 and 5. Section 4.1 details the quantitative findings related to Malaysia’s doping control trends, testing ratios, and international comparisons (RQs 1–3). Following this, the qualitative findings are presented: Section 4.2 examines the procedures for results management (RQ 4), and Section 4.3 covers education and awareness initiatives (RQ 5). The final research question (RQ 6), which synthesizes these findings to identify systemic strengths and weaknesses, will be addressed in the discussion in Chapter 5.

2 Methodology

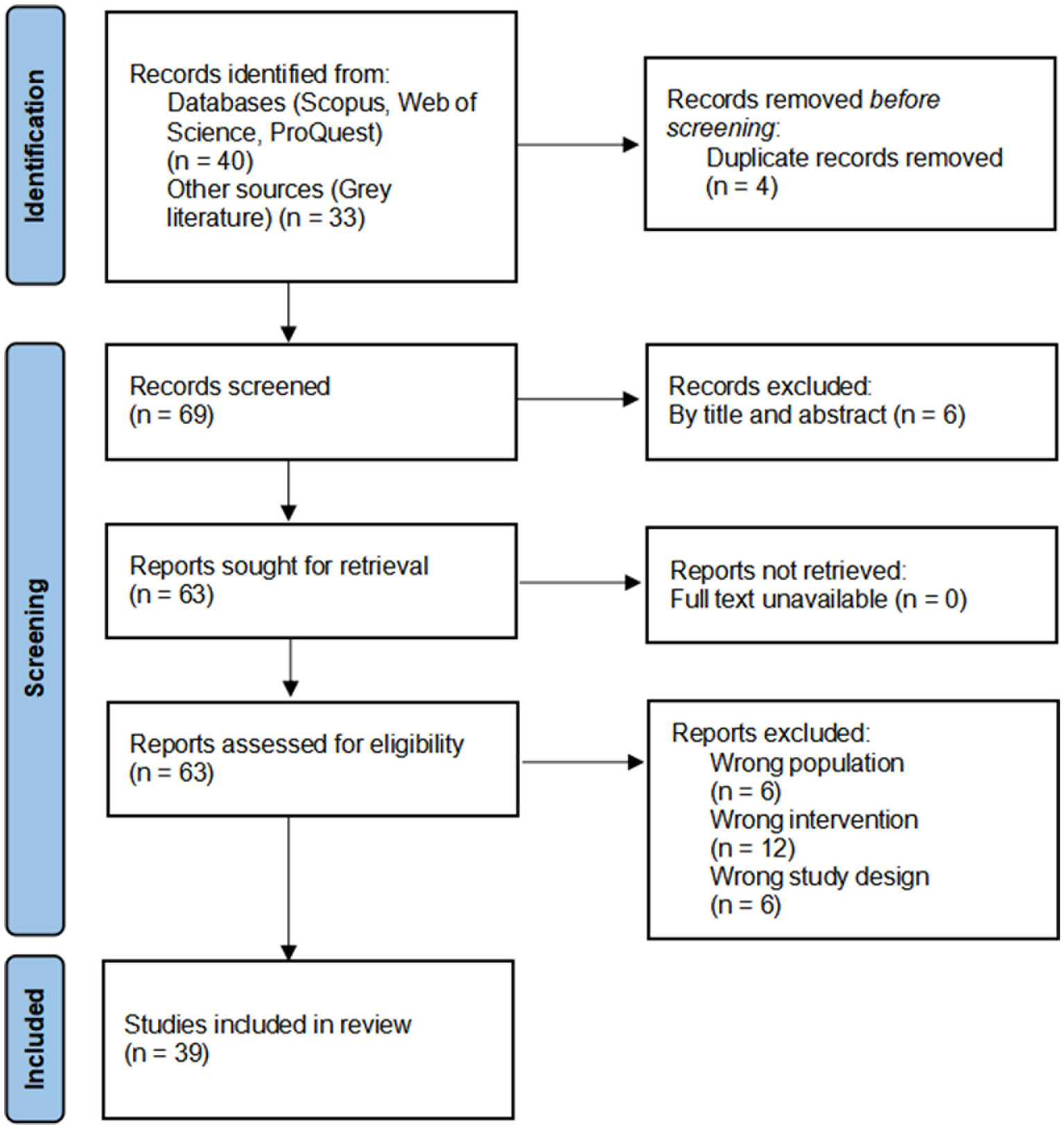

This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement. The review protocol was established a priori to define the research objectives, search strategy, and methods for data synthesis (Figure 1).

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Sources were included in this review if they met the following criteria: (1) directly addressed the legal, institutional, or operational aspects of anti-doping in Malaysia; (2) discussed the role of ADAMAS, Malaysia’s adherence to the UNESCO Convention, or the World Anti-Doping Code; and (3) were sourced from authoritative legal, governmental, or academic.

The temporal scope for inclusion was twofold to align with the study’s analytical approach. For the qualitative analysis of the current policy landscape and institutional performance, the review primarily focused on sources published from the year 2018 to 2024. For the quantitative longitudinal analysis of testing trends, official WADA testing figures from 2012 to 2022 were included. Consequently, sources published before these specified timeframes were generally excluded.

In the second phase, sources identified through the search were systematically screened for inclusion based on their relevance, authority, and timeliness. Sources were included if they directly addressed the legal and institutional framework of anti-doping in Malaysia, the operational activities of ADAMAS, Malaysia’s adherence to the UNESCO Convention and the World Anti-Doping Code, or documented challenges and successes in national anti-doping efforts. The review focused on Malaysia’s ratification of the Convention in recent years (2018–2024 for qualitative, 2012–2022 for quantitative). Conversely, sources were excluded if they were not directly relevant to the Malaysian context, were published outside the specified year range, or originated from sources that could not be verified as credible.

2.2 Information sources and search strategy

The search for relevant information was conducted across two primary categories: peer-reviewed academic literature and official grey literature from key governing bodies.

For the academic literature, a systematic search was conducted in the Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and ProQuest databases, limited to articles published between 2018 and 2024. A single, comprehensive search string was developed for Scopus and WoS to maximize sensitivity, combining three core concepts: the Malaysian context, the core subject of doping, and a broad range of keywords related to the study’s objectives.

The full search string used for Scopus and WoS was:

(“Malaysia” OR “ADAMAS”) AND (“doping” OR “anti-doping”) AND (“sport” OR “athlete” OR “competition” OR “hearing” OR “sanction” OR “policy” OR “education” OR “awareness” OR “test” OR “sample” OR “manage*” OR “funding” OR “compliance” OR “laboratory”).

A simplified search string (Malaysia AND doping AND athlete) was used for ProQuest, supplemented with filters (limit paper category to athletes OR dietary supplements OR knowledge OR questionnaires OR drugs and sports OR attitudes) to refine the results.

For the grey literature, a targeted retrieval strategy was employed on the official websites of key national and international organizations. The websites of the Anti-Doping Agency of Malaysia,1 the Ministry of Youth and Sports,2 and the World Anti-Doping Agency3 were systematically reviewed to source foundational legal documents, such as the ADAMAS Anti-Doping Rules 2021, Anti-Doping Administration and Management System, and the Sports Development Act 1997. This process also included the collection of official annual testing statistics, lists of sanctioned athletes, and educational program reports. Additionally, official websites for the Olympic Council of Malaysia,4 the Paralympic Council of Malaysia,5 and the Malaysian Sports Event6 were utilised to gather statistics on athlete participation in major events from 2017 to 2022.

2.3 Selection process

The selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, as illustrated in the flow diagram (Figure 1). The initial search yielded 73 records from academic databases (n = 40) and grey literature (n = 33). After removing 4 duplicate records, 69 unique records were advanced to the screening phase.

During screening, the title and abstract of each record were reviewed for relevance to the study’s research questions, resulting in the exclusion of 6 records. The full text of the remaining 63 reports was then retrieved and assessed for eligibility. In this phase, 24 reports were excluded for the following reasons: the study population was not Malaysian (n = 6); the focus was incorrect (e.g., outside the date range or not related to doping in sports) (n = 12); or the study design was a secondary review or bibliometric analysis (n = 6). This systematic process resulted in a final corpus of 39 sources included in this review.

2.4 Data extraction and synthesis

A standardized data extraction form was used to collect relevant information from the 39 included sources. Data were categorized under predefined themes aligned with the study’s research questions, including testing trends, procedures for results management, educational initiatives, and documented systemic vulnerabilities.

The extracted data were synthesized using a multi-method approach. A thematic analysis was conducted on the qualitative data from legal texts and official reports to identify recurring patterns, successes, and challenges. For the quantitative data, a longitudinal descriptive analysis of official WADA testing figures from 2012 to 2022 was performed to identify statistical trends. The findings from both the qualitative and quantitative analyses were then integrated to provide a comprehensive evaluation of Malaysia’s anti-doping framework.

3 Malaysia anti-doping architecture

Malaysia’s anti-doping framework is operationalised through a network of governmental and sports bodies, underpinned by a combination of subsidiary rules and broader statutes. At its center is the ADAMAS, the nation’s designated NADO since its establishment in 2007 and subsequent separation from the National Sports Institute (ISN) in 2016 to operate directly under the Ministry of Youth and Sports (ADAMAS, 2025a). This reposition solidified its national role but also highlights a potential vulnerability. Unlike fully independent NADOs in other nations, ADAMAS’s position within a government ministry and its ongoing effort to be formally embedded in the Sports Development Act 1997 present foundational challenges to its autonomy and authority (SCOOP, 2024a). The former director of ADAMAS has repeatedly mentioned that achieving this legislative recognition is crucial for the agency to be fully empowered (SCOOP, 2024a).

The legal framework itself is a patchwork rather than a single, consolidated statute. The Sports Development Act 1997 (Act 576) provides the overarching authority for the Minister to regulate sports (Section 41(2)), but it lacks explicit anti-doping mechanisms (Kementerian Belia dan Sukan, 2023). Consequently, the most direct translation of the WADA Code is found in the ADAMAS Anti-Doping Rules 2021, which define violations and procedures but are secondary legislation (ADAMAS, 2021). This architecture is supported by other key bodies, including the National Sports Council (MSN), the ISN, and the Olympic Council of Malaysia, which contribute to compliance, education, and policy coordination (Kementerian Belia dan Sukan, 2021; Olympic Council of Malaysia, 2021; ADAMAS, 2023).

4 Implementation in practice: enforcement, sanctioning, and education

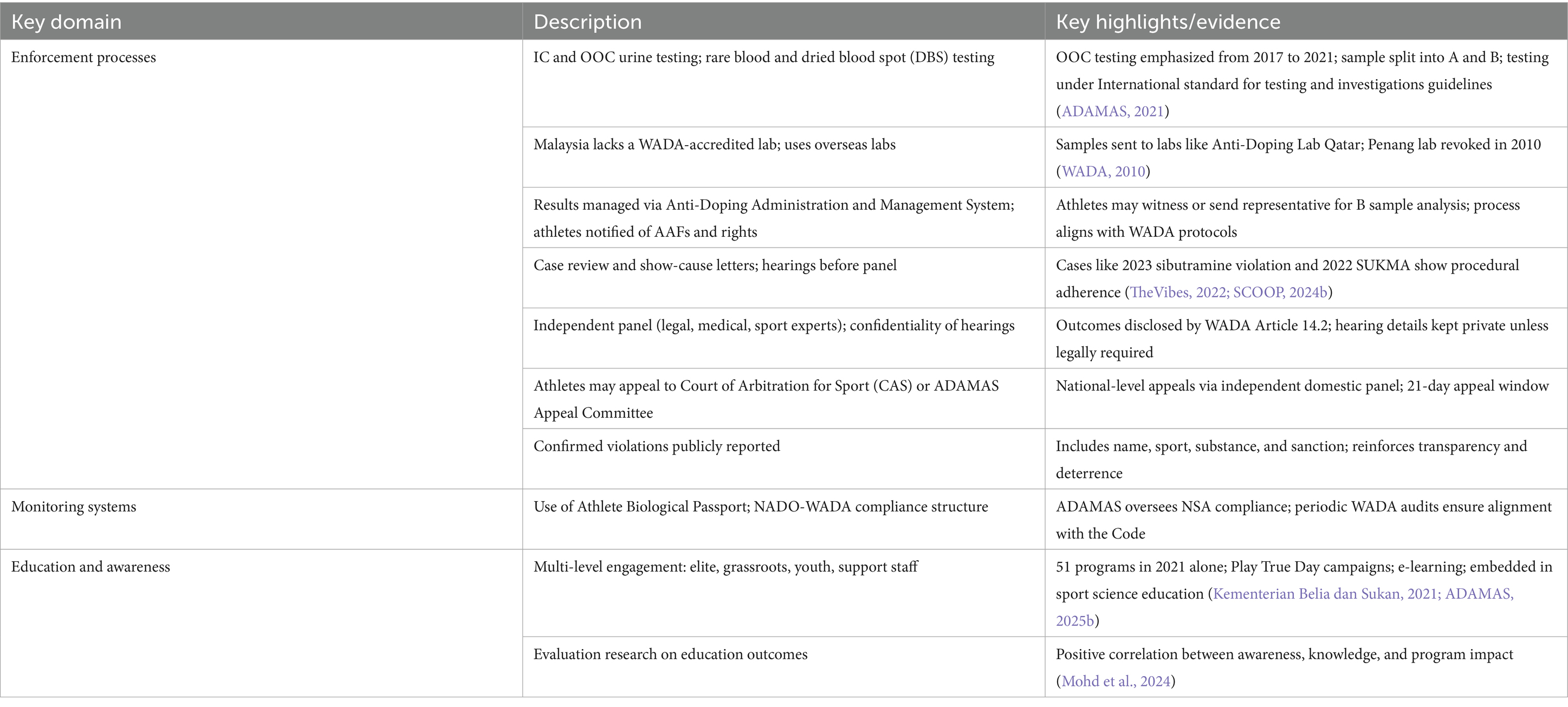

A summary of Malaysia’s core anti-doping functions is presented in Table 1, which outlines the key features of its enforcement processes, monitoring systems, and education and awareness initiatives.

4.1 Testing strategy and sample analysis

An analysis of ADAMAS’s testing data from 2012 to 2022 reveals a program characterised by fluctuating intensity and strategic inconsistencies rather than steady growth (WADA, 2024). Table 2, which summarises ADAMAS’s annual testing statistics, including total sample volume, the ratio of IC to OOC tests, and the number of AAFs. Total sample collection has seen significant peaks and troughs, ranging from a high of 822 samples in 2015 to a low of 98 during the pandemic-affected year of 2020. While testing recovered to 662 samples in 2022, the overall volume appears critically low when compared with the number of athletes participating in high-priority national events like the SUKMA Games. Moreover, the strategic focus between IC and OOC testing has also been inconsistent. While ADAMAS shifted towards a more robust OOC emphasis between 2017 and 2021, the ratio reverted to a higher IC focus in 2022, moving away from the best-practice OOC-centric approach favoured by leading NADOs for detecting sophisticated, systematic doping.

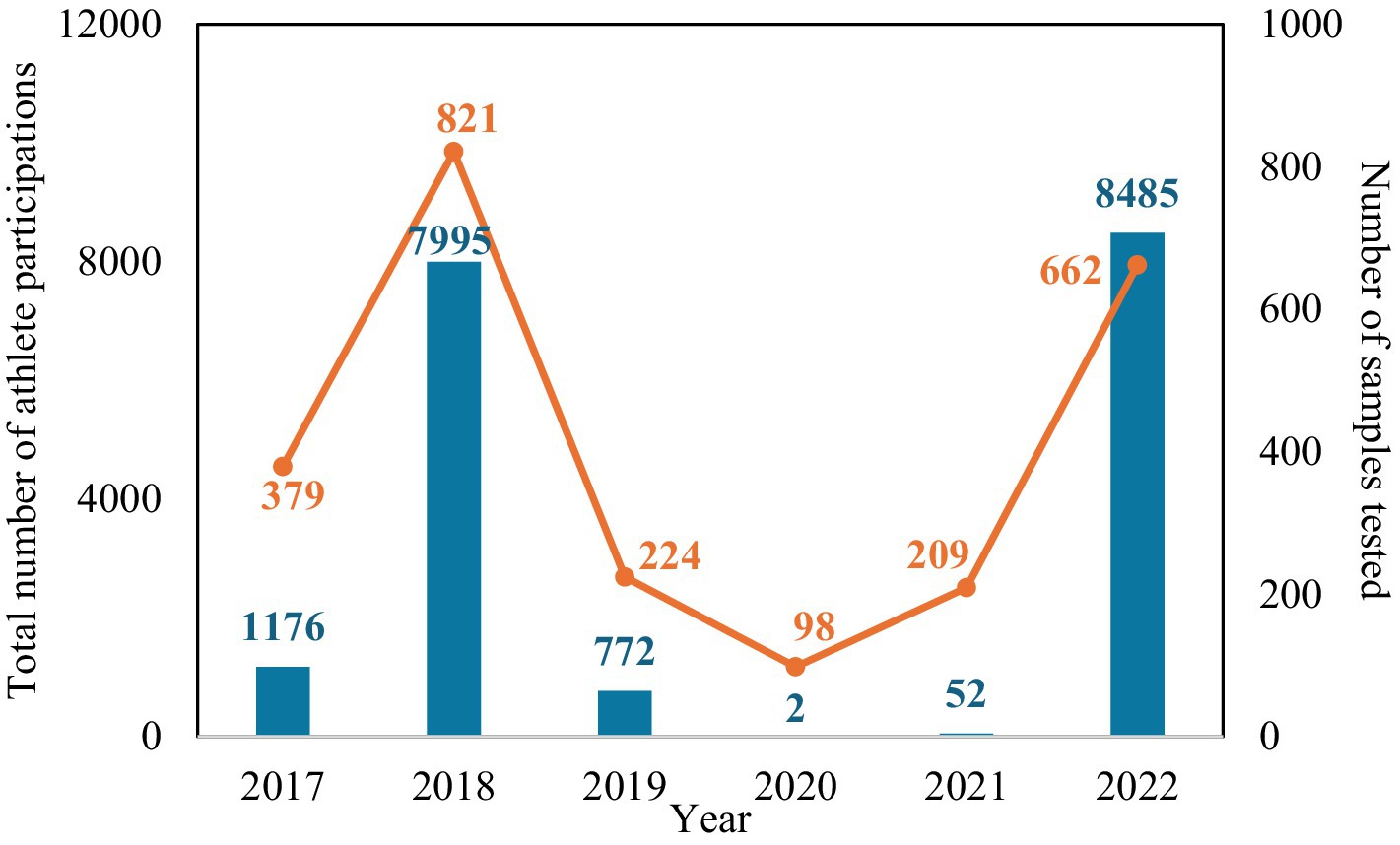

The challenge of achieving adequate testing coverage is starkly illustrated by comparing the large pool of high-priority athletes with the total number of samples collected annually. Table 3 quantifies the substantial number of Malaysian athletes participating in major national and international events between 2017 and 2022, while Figure 2 visually contrasts this large athlete pool against the comparatively small number of anti-doping tests conducted each year. This disparity suggests that only a small fraction of the athlete pool is tested, forcing ADAMAS to rely on targeted, intelligence-based testing rather than comprehensive coverage. For instance, in 2018, over 7,400 athletes participated in the SUKMA Games alone, in addition to 100 at other major events like the Asian Games. Yet, ADAMAS conducted only 821 total samples that year, which is equivalent to testing just 10.3% of those participants. Similarly, in 2022, with over 6,600 SUKMA participants and 100 more in other key events, only 662 total samples were collected, covering approximately 7.8% of the total participants. This stark disparity underscores a significant challenge in achieving comprehensive anti-doping coverage for the vast and dynamic pool of high-priority Malaysian athletes. Given the substantial number of participants, particularly in large national events like SUKMA which serve as critical pathways for national team selection, the current testing volumes suggest that only a small fraction of the eligible athlete population is subject to doping control annually. When the statistical probability of being tested is exceptionally low, the deterrent effect of the entire anti-doping program is fundamentally weakened, potentially fostering a culture where athletes perceive the risk of detection as minimal.

Figure 2. Comparison of Malaysian athlete participation in high-priority national and international sports events with total anti-doping samples tested (2017–2022). This figure visually contrasts the annual number of anti-doping samples collected from Table 2 with the estimated number of athletes participating in major events from Table 3.

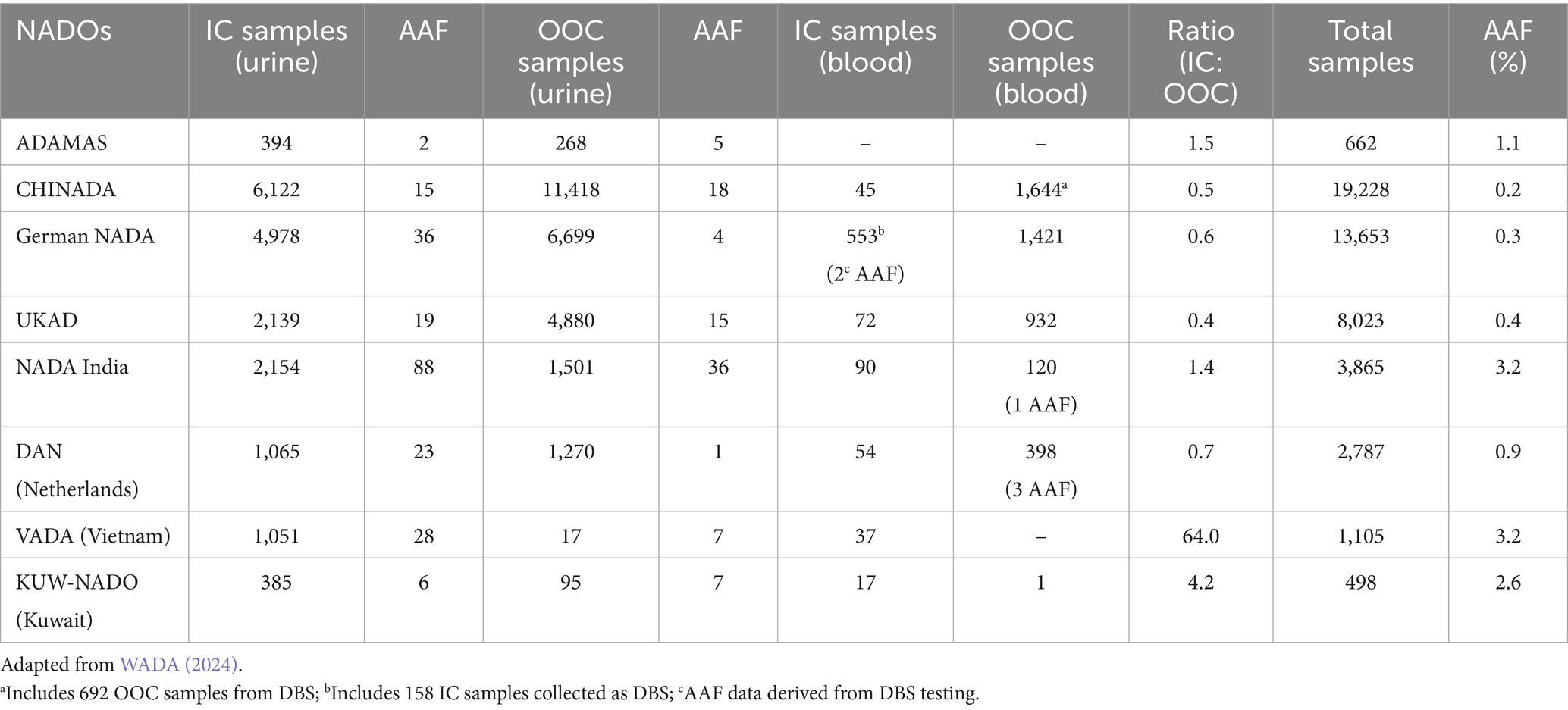

A critical deficiency in Malaysia’s program is the near-total absence of blood and DBS sampling (WADA, 2024). Across the entire decade from 2012 to 2022, only one blood sample was recorded by ADAMAS. This stands in stark contrast to the practices of other NADOs, a gap quantified in Table 4, which compares the testing statistics of ADAMAS with several other NADOs for the year 2022. For instance, while ADAMAS conducted zero blood tests in 2022, leading organizations such as the German NADA and UKAD conducted 1,974 and 1,004 blood tests, respectively. While such cross-national comparisons must be interpreted as a benchmark of operational scale rather than a direct performance ranking due to differing national sport mixes and event calendars, the complete absence of a blood testing program in Malaysia represents a fundamental gap in capability, not merely a statistical difference. This creates a significant blind spot, as blood is the only matrix for reliably detecting key substances like human growth hormone and certain types of erythropoietin. (WADA, 2021a). This gap is a direct consequence of Malaysia’s reliance on foreign labs and the associated logistical and financial burdens, effectively inhibiting its ability to conduct a truly comprehensive testing program against modern doping practices.

Moreover, a key factor underpinning the performance disparity shown in Table 4 is the presence of domestic WADA-accredited laboratories. Leading NADOs with high testing volumes, such as the German NADA (which operates two accredited labs in Cologne and Kreischa) and UKAD (one lab in London), possess this crucial infrastructure, as does NADA India (one lab in New Delhi). In contrast, ADAMAS has lacked a domestic accredited laboratory since its facility in Penang had its accreditation revoked in 2010. This absence of national infrastructure is the primary driver of the strategic gaps in its testing program. Without a local lab, the logistical complexity and significant financial burden of shipping samples overseas, particularly blood samples, which have stricter handling requirements, become prohibitive. This directly explains the near-total absence of blood testing in Malaysia’s program and forces a reliance on a less comprehensive, urine-only testing model.

4.2 Results management, sanctioning, and appeal

When a sample results in an AAF, Malaysia’s results management process aligns closely with the World Anti-Doping Code and its associated International Standards (ADAMAS, 2021; WADA, 2021b). The procedure ensures athlete rights through a structured notification process, the right to B-sample (a second portion of the original sample collected) analysis, and access to a fair hearing and subsequent appeal. The entire process is managed via the secure Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (WADA, 2025b).

Article 8 of the ADAMAS Anti-Doping Rules 2021 establishes the right to a fair hearing for any person asserted to have committed an anti-doping rule violation, which is conducted by a fair, impartial, and operationally independent hearing panel. This process is managed by the ADAMAS hearing committee, a body composed of an independent chair and four other independent members with legal, sports, medical, or scientific expertise who are appointed for a renewable 2-year term. For each case, a three-member panel, which must include one qualified lawyer and one qualified medical practitioner, is appointed to hear the case and issue a written decision with full reasons for the outcome. The article also provides a provision for an athlete or other person to waive their right to a hearing or for a case to be heard in a single hearing directly at the CAS with the consent of all relevant parties. Following a final decision that an anti-doping rule violation has been committed, Article 10 takes effect. The standard period of ineligibility is 4 years for intentional violations involving non-specified substances and 2 years for other violations. Sanctions can range from a reprimand to a lifetime ban for severe violations like trafficking or for a third offense.

This procedural soundness has been demonstrated in several recent cases in Malaysia. For instance, following the 2022 SUKMA Games, multiple athletes were issued show-cause letters and informed of their rights within the mandated 14-day window (The Malaysian Insight, 2022; TheVibes, 2022). A 2023 case involving a national high jump athlete testing positive for sibutramine further illustrates the process: after being notified, the athlete opted against a B-sample analysis and proceeded directly to a hearing, which resulted in a 2-year sanction backdated to the time of collection (SCOOP, 2024b). Hearings are conducted by an independent panel of legal, medical, and sporting experts to ensure impartiality (TheVibes, 2023). While final sanctions are publicly disclosed to ensure transparency and deterrence, the detailed content of the hearings remains confidential in accordance with WADA’s International standard for results management, a practice that balances transparency with athlete privacy (WADA, 2014, 2021b).

Additionally, according to the ADAMAS Anti-Doping Rules 2021, the appeal process is governed by Article 13 and provides two distinct routes based on an athlete’s competitive level. In cases involving International-level Athletes or those arising from an international event, the decision may be appealed exclusively to the CAS, as stipulated in Article 13.2.1. For all other athletes, the decision is first appealed domestically to the ADAMAS Appeal Committee, in accordance with Article 13.2.2. However, the decision of the domestic Appeal Committee is not necessarily final, as Article 13.2.3.2 grants WADA and the relevant International Federation the right to appeal that decision to the CAS.

While Malaysia’s results management process is procedurally aligned with the WADA Code, its overall effectiveness is subject to a critical consideration. There is a potential gap between transparency for deterrence and transparency for education. Publicly disclosing a sanction serves as a deterrent, but the confidentiality of hearing details, while protecting athlete privacy, may represent a missed opportunity for preventative education. For example, a case involving a substance like sibutramine, which is often found in contaminated supplements, could be used as a powerful, anonymized case study to educate the wider athlete community on the specific risks of supplement use. The current model focuses on punitive transparency, publicly disclosing the athlete’s name, sport, substance, and sanction length, whereas a shift towards including educational transparency could be a more effective long-term strategy for prevention.

4.3 Education and awareness initiatives

Education is a fundamental pillar of Malaysia’s anti-doping strategy, with ADAMAS conducting extensive outreach targeting athletes at all levels, from grassroots to elite, as well as coaches and support personnel (UNESCO, 2019; MalayMail, 2024; Olympic Council of Malaysia, 2025b). In 2021 alone, the agency ran 51 programs, including in-person workshops, e-learning modules, and social media campaigns aligned with WADA’s “Play True” initiative (Kementerian Belia dan Sukan, 2021; ADAMAS, 2025b). The ADAMAS education program includes a formal evaluation process (ADAMAS, 2025c). For instance, its 2021 report surveyed over 4,400 respondents from targeted groups. The resulting statistics showed that respondents had, on average, at least a solid understanding of the 2021 Anti-Doping Code and Rules. This indicates that the educational initiative has successfully reached 1,000 of individuals in relevant groups. However, the report also stated that 1,308 respondents (29%) believe that awareness of the importance of anti-doping is still lacking among athletes and their support personnel.

Additionally, recent research involving 62 Malaysian athletes confirms a strong positive correlation between these educational programs and the athletes’ resulting knowledge and awareness (Mohd et al., 2024). The study highlighted awareness as a particularly strong predictor of program success, underscoring the value of proactive and accessible education. However, while these initiatives are effective at disseminating information, their direct impact on reducing doping intent or behaviour remains an area requiring further research, moving from measuring awareness to assessing behavioural change.

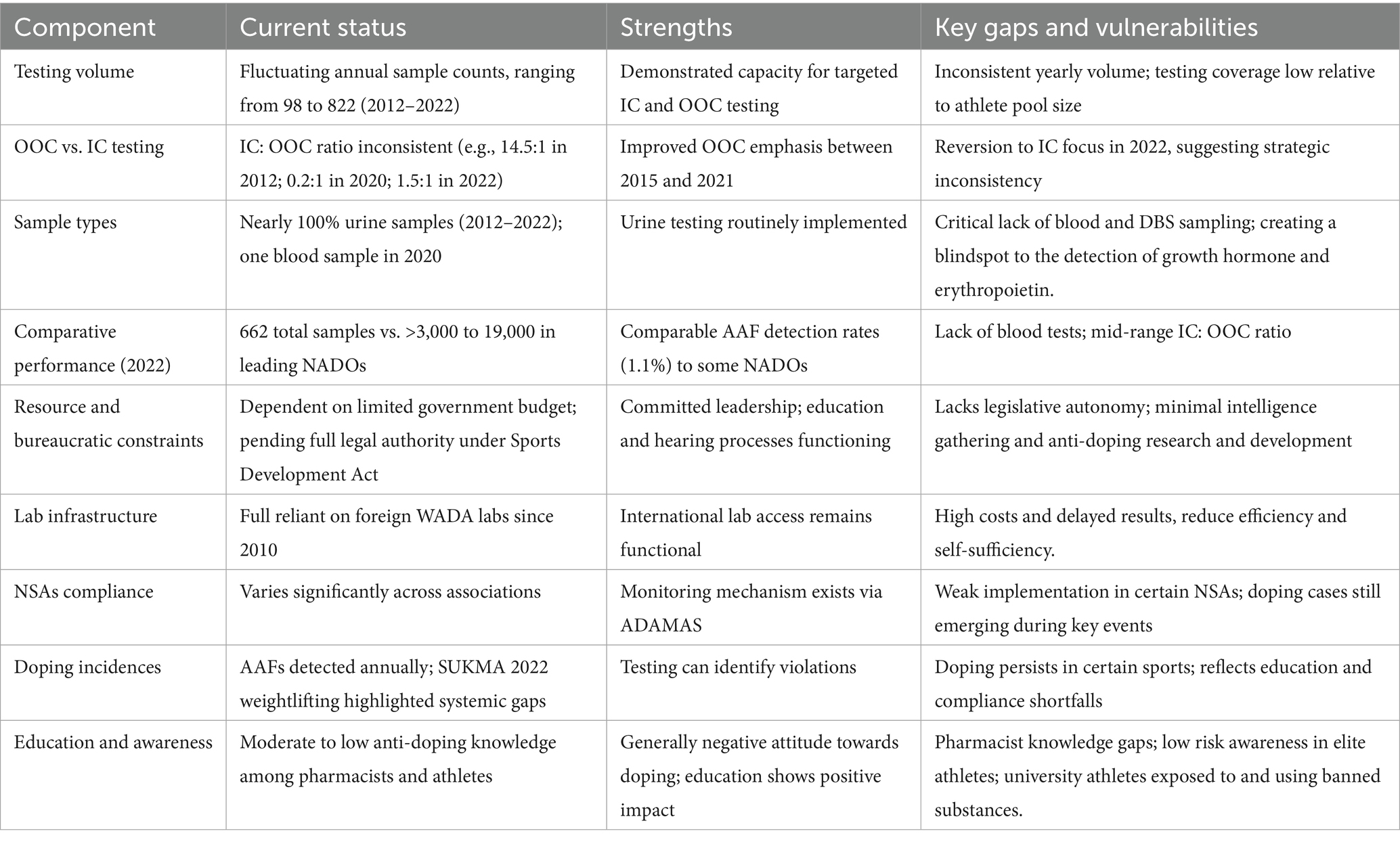

5 Key strengths and vulnerabilities

Despite a functional procedural framework, Malaysia’s anti-doping system is hampered by several vulnerabilities that hinder its full alignment with the UNESCO Convention’s objectives and international best practices. A summary of the key strengths and vulnerabilities within Malaysia’s anti-doping framework is presented in the following Table 5.

5.1 The resource and autonomy deficit

A primary challenge is the dual constraint of limited resources and incomplete legislative autonomy. NADOs in developing nations often operate with significantly constrained budgets compared to their counterparts in more developed countries (Ruwuya et al., 2022; Read et al., 2024). This funding pressure limits critical resource allocation for intelligence gathering, comprehensive testing, and widespread educational outreach. Compounding this is ADAMAS’s lack of full statutory independence. Unlike leading NADOs enshrined in dedicated legislation that grants them robust autonomy (Department for Culture Media and Sport, 2021; UK National Anti-Doping, 2021; NADA, 2025), ADAMAS’s continued effort to be formally included in the Sports Development Act 1997 means it remains subject to systemic bureaucratic hindrance, a status Malaysia is still actively striving to change (SCOOP, 2024a).

5.2 Dependency on foreign laboratories

One of the most significant structural weaknesses is Malaysia’s 100% dependency on foreign WADA-accredited laboratories since its own lab in Penang had its accreditation revoked in 2010 (WADA, 2010). This reliance creates substantial logistical hurdles, increases result turnaround times, and incurs significant financial costs. A former minister estimated that analysing samples overseas is nearly five times more expensive than doing so domestically (New Straits Times, 2015). While the upfront investment to establish a new lab is considerable (estimated at USD 4.2 million), the long-term strategic benefits of self-reliance, national expertise, and research capacity are immense. This dependency starkly contrasts with regional counterparts like Thailand and major Asian economies like China and India, all of which operate their own accredited facilities (WADA, 2025c).

5.3 Inconsistent compliance and persistent doping

A study of Malaysian doping cases from 2005 to 2022 indicates that doping remains a persistent challenge, with violations frequently clustering around major competitions like the SEA Games, Asian Games, and SUKMA Games (Rahman et al., 2024). This pattern implies that the heightened pressures of high-stakes competition may be a key factor motivating athletes towards the use of prohibited substances. The data further reveal that anabolic agents are the most commonly detected substance class, with a higher prevalence of violations among male athletes, particularly in sports with high physical demands like bodybuilding, weightlifting, athletics, and cycling. Although the COVID-19 pandemic led to a temporary decline in cases in 2020 due to minimal sporting events and reduced testing, the subsequent resurgence in 2021 and 2022 (Table 2) highlights the tenacity of the problem and reinforces the need for sustained and comprehensive anti-doping measures.

Unfortunately, ensuring consistent anti-doping compliance across all National Sports Associations (NSAs) remains a persistent challenge. Experts have observed that violations appear more frequently in certain sports like weightlifting and athletics, suggesting that anti-doping education and monitoring are not uniformly implemented at the grassroots level (Twenty Two, 2023). The continued emergence of doping cases at major national events, such as the multiple positives in weightlifting at the 2022 SUKMA Games, serves as a reminder that despite all efforts, doping persists. While these detections prove the testing system works, their occurrence undermines public trust and highlights that the existing vulnerabilities in resources, autonomy, and testing strategy have real-world consequences for clean sport in Malaysia.

5.4 Knowledge gaps among healthcare professionals and athletes

Systematic reviews of anti-doping education in Malaysia reveal that research on healthcare professionals has focused almost exclusively on pharmacists, consistently identifying significant knowledge gaps. A survey of 384 community pharmacists in Malaysia indicated a moderate to limited level of knowledge regarding doping (Voravuth et al., 2022). Significant knowledge deficits were identified, as 65.9% of respondents did not recognize inadvertent doping as an anti-doping rule violation, and 90% demonstrated poor awareness of specific doping scenarios within the country. This aligns with findings from a study of 108 community pharmacists in Kuala Lumpur, which found that while they believe their role in doping prevention is important, their actual knowledge on the topic is poor, and they feel unprepared to offer related services (Lim et al., 2018a). This knowledge deficit also extends to those in training, as a survey of 273 final-year Malaysian pharmacy students revealed a moderate level of knowledge, though it was significantly higher in those who had attended courses on drugs in sport (Chan et al., 2019).

These knowledge gaps within the healthcare community are particularly concerning given the direct risks faced by athletes, especially at the elite level. A study focusing on 50 elite Malaysian athletes highlighted a significant risk of unintentional doping, stemming from a disconnect between practice and awareness (Balaravi et al., 2017). It was found that while a substantial 72% of these athletes use nutritional supplements, only 38% are aware of the associated doping risks. This vulnerability is further intensified by the finding that at least 25% of commercially available supplements are contaminated with banned substances, placing even well-intentioned athletes in a precarious position (Balaravi et al., 2017).

This environment of risk is not confined to the elite level; it also permeates the university sports population where the next generation of athletes is developed. Research on 182 Malaysian university athletes reveals that despite a generally negative attitude towards doping, direct exposure to banned substances is a reality (Lim et al., 2018b). Specifically, 12% of these student athletes reported having been offered a banned substance. Of this group that was offered, 4.4% admitted to using the substances for non-medical reasons, while 13.7% used them for medical purposes, indicating a tangible pathway from offer to use.

6 Recommendations

To fundamentally strengthen Malaysia’s anti-doping framework and ensure its full alignment with the UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport, the following specific and actionable recommendations are proposed:

To address the current systemic bureaucratic constraints and establish a robust legal foundation, it is crucial that Parliament prioritises the drafting and enactment of a comprehensive, standalone Anti-Doping Act. This dedicated legislation would consolidate all disparate anti-doping regulations, including the UNESCO Convention’s provisions and the World Anti-Doping Code, into a single, cohesive statute, thereby overcoming the current reliance on fragmented legal instruments. Concurrently, this Act should explicitly enhance ADAMAS’s legislative embedding, granting it fully functional autonomy and adequate resources. This independence, akin to leading international NADOs, would empower ADAMAS with the necessary legal authority and operational freedom to streamline processes, accelerate decision-making, and significantly enhance its capacity for intelligence gathering and enforcement, moving beyond its current ‘work-in-progress’ status under existing acts. Furthermore, sustainable funding models must be diversified for ADAMAS, beyond current governmental allocations, to support continuous investment in all pillars of anti-doping. This includes dedicated budget lines for human capital development, advanced intelligence-led investigations, and sophisticated data analytics, directly addressing identified resource limitations.

A critical priority to mitigate the complete dependency on foreign laboratories and associated high costs is the allocation of necessary capital investment (estimated at USD 4.2 million) and operational funding to establish a WADA-accredited anti-doping laboratory in Malaysia. This strategic investment would significantly reduce the substantial financial burden (approximately USD 200 per sample currently) and logistical complexities associated with sending samples overseas. With a domestic laboratory, ADAMAS can then consistently implement advanced testing methodologies, particularly comprehensive blood sample collection, including DBS analysis, which is notably absent from current national testing figures. This would enhance the detection of substances more effectively identified in blood and enable full participation in the Athlete Biological Passport program. Moreover, establishing a local laboratory would foster the development of national scientific expertise in anti-doping analysis and facilitate collaboration with local universities for performance biomarker studies and innovative detection technologies, thereby addressing the current limited anti-doping research capacity.

To enhance compliance and accountability across the entire sporting ecosystem, clear and legally binding requirements must be introduced for all NSAs to adopt and consistently adhere to code-compliant anti-doping regulations. This involves ensuring adequate anti-doping education at grassroots levels, timely reporting of athlete whereabouts information, and prompt adoption of updates to the Anti-Doping Code, particularly addressing the inconsistent compliance observed among NSAs. Stricter measures and clearer sanctions, as outlined in Article 9 of the UNESCO Convention, must also be enforced against athlete support personnel found guilty of anti-doping rule violations. To ensure systematic progress, a national roadmap with specific, measurable benchmarks should be developed to track and ensure consistent anti-doping compliance across all NSAs, especially focusing on less-established associations where doping incidences appear more prevalent. Finally, anti-doping efforts should include ongoing, localized research on doping prevalence and attitudes within Malaysia, alongside the continuous development of tailored education programs for vulnerable groups, utilising diverse methods, such as e-learning and interactive seminars to maximize outreach and impact.

7 Conclusion

This review has thoroughly evaluated Malaysia’s anti-doping framework, assessing its legislative foundations, enforcement mechanisms, and alignment with the UNESCO International Convention against Doping in Sport. Our findings highlight Malaysia’s significant progress in establishing a robust anti-doping system, largely compliant with the World Anti-Doping Code. Key successes include the development of a strong legal and institutional framework through ADAMAS and its comprehensive Anti-Doping Rules 2021. Malaysia has also implemented strategic and expanding testing programs, notably an emphasis on OOC testing from 2017 to 2021, which reflects a proactive stance against doping. The effective enforcement of WADA-compliant penalties, demonstrated by recent athlete sanctions, emphasizes a commitment to accountability. Furthermore, substantial gains in anti-doping education and awareness have fostered a more informed and ethical sporting environment, as supported by local research.

Despite these achievements, several obstacles continue to hinder Malaysia’s full alignment with the UNESCO Convention. These include resource and bureaucratic limitations that restrict ADAMAS’s operational capacity and outreach. Malaysia’s complete dependence on foreign WADA-accredited laboratories creates significant financial and logistical burdens. This reliance restricts sample analysis primarily to urine, leaving a critical blindspot for detecting blood-specific doping agents like growth hormone and erythropoietin. Establishing a national laboratory would also require a significant initial investment. In addition, inconsistent anti-doping compliance among certain NSAs and recurring doping cases at major national events, such as the SUKMA 2022 weightlifting cases, reflect ongoing difficulties in achieving widespread adherence to clean sport practices.

This review is necessarily limited by its reliance on publicly available data and its macro-level focus on policy frameworks. These limitations open clear avenues for future research. Future studies should therefore employ qualitative methods, such as interviews with key stakeholders, to capture the internal perspectives on policy implementation. Further research could also investigate the socio-cultural drivers of doping in Malaysia, complementing this study’s policy focus and providing a more holistic understanding of the issue. Addressing these identified vulnerabilities will be crucial for Malaysia to fully realise its commitment to clean sport and solidify its standing as a leader in anti-doping within the region.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

JC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. LT: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was fully funded by Research University Grant GUP-2023-066 from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AAF, Adverse analytical finding; ADAMAS, Anti-doping agency of Malaysia; CAS, Court of Arbitration for Sport; DBS, Dried blood spot; IC, In-competition; NADO, National Anti-Doping Organization; NSA, National Sports Associations; OOC, Out-of-competition.

Footnotes

References

ADAMAS. (2021). Anti-doping agency of Malaysia (ADAMAS) anti-doping rules 2021. Available online at: https://www.adamas.gov.my/en/home-adamas/resources.html?download=14:adamas-anti-doping-rules-2021 (Accessed June 13, 2025).

ADAMAS. (2023). Anti-doping briefing for athletes and coaching staff of Malaysia's shooting sports at the National Sports Institute (NSI) Bukit Jalil. Available online at: https://www.adamas.gov.my/en/component/content/article/148-taklimat-anti-doping-atlet-dan-staf-kejurulatihan-sukan-menembak-malaysia-di-institut-sukan-negara-isn-bukit-jalil.html?catid=91&Itemid=934 (Accessed June 13, 2025).

ADAMAS. (2025a). Anti-doping agency Malaysia. Available online at: https://www.adamas.gov.my/en/home-adamas/about-us.html (Accessed June 13, 2025).

ADAMAS. (2025b). Play true day campaign 2025: ‘play true – it starts with you’. Available online at: https://www.adamas.gov.my/en/component/content/article/169-kempen-play-true-day-2025-play-true-it-starts-with-you.html?catid=91&Itemid=934 (Accessed June 16, 2025).

ADAMAS. (2025c). Resources. Available online at: https://www.adamas.gov.my/en/home-adamas/resources.html (Accessed June 16, 2025).

Balaravi, B., Chin, M. Q., Karppaya, H., Chai, W. J., Samantha, Q. L. W., and Ramadas, A. (2017). Knowledge and attitude related to nutritional supplements and risk of doping among national elite athletes in Malaysia. Malays. J. Nutr. 23, 409–423.

Chan, S. Y., Lim, M. C., Shamsuddin, A. F., and Mahmood, T. M. T. (2019). Knowledge, attitude and perception of Malaysian pharmacy students towards doping in sports. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 49, 135–141. doi: 10.1002/jppr.1478

Department for Culture Media and Sport. (2021). UK National Anti-doping Policy (2021). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-anti-doping-policy-consultation/outcome/uk-national-anti-doping-policy-2021 (Accessed June 20, 2025).

FMT. (2017). Diver Ng loses SEA Games gold medals after failing doping test. Available online at: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2017/10/26/diver-ng-loses-sea-games-gold-medals-after-failing-doping-test (Accessed June 23, 2025).

Hamid, A. G., and Sein, K. M. (2006). Judicial application of international law in Malaysia, an analysis, Malaysian Bar Badan Peguam Malaysia. Available online at: https://www.malaysianbar.org.my/article/news/legal-and-general-news/legal-news/judicial-application-of-international-law-in-malaysia-an-analysis (Accessed June 13, 2025).

Hider, S. (2015). Eight months suspension for Shuttler. Available online at: https://www.antidopingdatabase.com/news/eight-months-suspension-for-shuttler (Accessed September 21, 2025).

Kementerian Belia dan Sukan. (2021). Agency anti-doping of Malaysia education report 2021. Available online at: https://www.adamas.gov.my/en/home-adamas/resources.html?download=13:education-programs-report-2021 (Accessed June 20, 2025).

Kementerian Belia dan Sukan. (2023). Sport development act 1997. Available online at: https://www.kbs.gov.my/akta-dasar/345-akta-576.html?download=2405:sports-development-act-1997-576 (Accessed June 13, 2025).

Lim, M. C., Hatah, E., and Shamsuddin, A. F. (2018a). The readiness of community pharmacists as counsellors for athletes in addressing issues of the use and misuse of drugs in sports. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 37, 1049–1055.

Lim, M. C., Shamsuddin, A. F., and Mahmood, T. M. T. (2018b). Knowledge, attitude and practice on doping of Malaysian student athletes. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 11:72. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2018.v11i5.23598

MalayMail. (2024). Sports minister urges bodybuilding clubs to boost anti-doping awareness at amateur level. Available online at: https://www.malaymail.com/news/sports/2024/10/27/sports-minister-urges-bodybuilding-clubs-to-boost-anti-doping-awareness-at-amateur-level/155029 (Accessed June 16, 2025).

Mohd, N. N. H., Che, S. M., Yaacob, M., and Saref, Z. (2024). Effectiveness of Adamas anti-doping program: a perception study of Malaysian athletes. Asian People J. 7, 18–32. doi: 10.37231/apj.2024.7.2.587

NADA. (2025). NADA Germany’s organisation. Available online at: https://www.nada.de/en/organisation (Accessed June 20, 2025).

New Straits Times. (2015). KBS to set up new anti-doping lab in Bukit Jalil. Available online at: https://www.nst.com.my/news/2015/09/kbs-set-new-anti-doping-lab-bukit-jalil (Accessed: June 13, 2025).

Olympic Council of Malaysia (2021). Bye law to sub article 5.11 of the constitution of OCM. Available online at: ics.com.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/OCM-Bye-Law-Anti-Doping.pdf (Accessed June 13, 2025).

Olympic Council of Malaysia. (2025a). Games. Available online at: https://olympics.com.my/ (Accessed June 16, 2025).

Olympic Council of Malaysia. (2025b). Malaysia: anti-doping. Available online at: https://olympics.com.my/integrity/anti-doping/#anti-doping-roles (Accessed June 16, 2025).

Paralympic Council Malaysia. (2025). Events. Available online at: https://www.paralympic.org.my/ (Accessed June 16, 2025).

Rahman, S. K. A., Razali, M. R. M., Yeo, W. K., and Rahmat, N. (2024). Doping trends in Malaysian sports: analysis of banned substances usage among athletes. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 12, 943–952. doi: 10.13189/saj.2024.120606

Read, D., Skinner, J., Smith, A. C., Lock, D., and Stanic, M. (2024). The challenges of harmonising anti-doping policy implementation. Sport Manag. Rev. 27, 365–386. doi: 10.1080/14413523.2023.2288713

Ruwuya, J., Juma, B. O., and Woolf, J. (2022). Challenges associated with implementing anti-doping policy and programs in Africa. Front. Sports Act. Liv. 4:966559. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2022.966559

SCOOP. (2024a). Adamas director bids farewell, urges continued push for anti-doping authority under sports act. Available online at: https://www.scoop.my/sports/231798/adamas-director-bids-farewell-urges-continued-push-for-anti-doping-authority-under-sports-act/ (Accessed June 19, 2025).

SCOOP. (2024b). High jump athlete faces two-year ban for doping. Available online at: https://www.scoop.my/sports/154976/high-jump-athlete-faces-two-year-ban-for-doping/ (Accessed June 14, 2025).

SUKMA. (2025). Malaysian sports event. Available online at: https://www.nsc.gov.my/sukan-malaysia-sukma/ (Accessed June 14, 2025).

The Malaysian Insight. (2022). 2 weightlifting medallists at 20th Sukma fail doping test. Available online at: https://www.themalaysianinsight.com/s/419958 (Accessed June 14, 2025).

TheVibes. (2022). Anti-doping body to act against two Sukma weightlifting medallists. Available online at: https://www.thevibes.com/articles/sports/81475/anti-doping-body-to-act-against-two-sukma-weightlifting-medallists (Accessed June 14, 2025).

TheVibes. (2023). Athletics athlete temporarily suspended for failing doping test: Adamas. Available online at: https://www.thevibes.com/articles/sports/94411/athletics-athlete-temporarily-suspended-for-failing-doping-test-adamas (Accessed June 16, 2025).

Twenty Two. (2023). Malaysia needs clear roadmap, onus on sports associations to curb doping violations. Available at: https://twentytwo13.my/malaysia-needs-clear-roadmap-onus-on-sports-associations-to-curb-doping-violations/ (Accessed: June 16, 2025).

UK National Anti-Doping. (2021). New UK national anti-doping policy launches. Available online at: https://www.ukad.org.uk/news/new-uk-national-anti-doping-policy-launches (Accessed June 20, 2025).

UNESCO. (2005). International convention against doping in sport. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000142594 (Accessed June 13, 2025).

UNESCO. (2019). 10 Dec outreach program on anti-doping in conjunction with Malaysia Unesco day 2019. Available online at: https://www.unesco.org.my/component/content/article/outreach-program-on-anti-doping-in-conjunction-with-malaysia-unesco-day-2019?catid=11 (Accessed June 16, 2025).

Voravuth, N., Chua, E. W., Mahmood, T. M. T., Lim, M. C., Puteh, S. E. W., Safii, N. S., et al. (2022). Engaging community pharmacists to eliminate inadvertent doping in sports: a study of their knowledge on doping. PLoS One 17:e0268878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268878

WADA. (2010). WADA revokes Penang laboratory accreditation. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/news/wada-revokes-penang-laboratory-accreditation (Accessed June 13, 2025).

WADA. (2014). Results management, hearings and decisions guidelines. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wada_guidelines_results_management_hearings_decisions_2014_v1.0_en.pdf (Accessed June 16, 2025).

WADA. (2021a). Guidelines for implementing an effective testing program. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/isti_guidelines_for_implementing_an_effective_testing_program_final.pdf (Accessed June 23, 2025).

WADA. (2021b). World anti-doping code 2021. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/2021_wada_code.pdf (Accessed June 16, 2025).

WADA. (2024). 2022 anti-doping testing figures. Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/2022_anti-doping_testing_figures_en.pdf (Accessed 20 November, 2024).

WADA. (2025a). Anti-doping statistics. Available at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/data-research/anti-doping-statistics (Accessed: March 12, 2025)

WADA. (2025b). Anti-doping administration & management system (ADAMS). Available online at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/adams (Accessed June 13, 2025).

WADA. (2025c). Accredited laboratories for doping control analysis. Available at: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/wada_accredited_laboratories_en_june.doc_0.pdf (Accessed: June 20, 2025).

Keywords: anti-doping, UNESCO convention, sports law, doping control, policy implementation, ADAMAS

Citation: Chin JJCC and Tan LL (2025) Beyond ratification: a critical review of Malaysia’s implementation of the UNESCO anti-doping convention. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1689693. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1689693

Edited by:

Stylianos Ioannis Tzagkarakis, Hellenic Open University, GreeceReviewed by:

Jan Exner, Charles University, CzechiaNurul Hidayana Mohd Noor, MARA University of Technology, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Chin and Tan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ling Ling Tan, bGluZ2xpbmdAdWttLmVkdS5teQ==

Jeremy Jason Chwan Chuong Chin

Jeremy Jason Chwan Chuong Chin Ling Ling Tan

Ling Ling Tan