- 1Instituto de Estudios Nacionales, Universidad de Panama, Panama City, Panama

- 2Sistema Nacional de Investigacion, Senacyt, Panama City, Panama

- 3Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Exactas y Tecnología, Universidad de Panama, Panama City, Panama

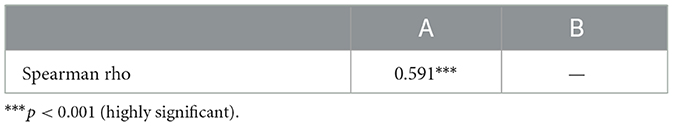

This article presents an analysis of President Trump's statements on the Panama Canal from the perspective of Mearsheimer's Offensive Realism, examining their impact on Panamanian national identity and perception of sovereignty complemented by Dependency Theory to account for Panama's position as a peripheral and dependent state. The research is based on statistical analysis of two public opinion surveys (n = 906, n = 732) conducted in February and April 2025, applying chi-square tests, correspondence analysis, and Spearman's correlation. Results reveal that Panamanians interpret these statements as a geopolitical strategy aimed at containing Chinese influence in the region, confirming Offensive Realism principles of power maximization and control of spheres of influence. Findings indicate that the Panama Canal is a symbol of Panamanian national identity and territorial sovereignty. The temporal analysis shows an evolution in public perception, where the narrative about the “Chinese threat” progressively lost credibility (p < 0.024), while identification with the Canal as a national symbol remained strong (Spearman's correlation = 0.591, p < 0.001). Provinces differed significantly in how they saw presidential comments and how the media handled information. Popular response based on historical memory and collective identity demonstrates national symbols used as defense mechanisms against external hegemonic pressures in the reconfiguration of the international order.

1 Introduction

The world within a framework of reconfiguration of the international order is characterized by the rivalry and disputes between powers such as Russia, China, and the United States, being that this last power who tries to maintain their global power and hegemony. Under this global scenario, regions such as Latin America have become an essential scenario for this contest, where the Panama Canal becomes the epicenter of a geopolitical dispute.

This article addresses, from the Panamanian context, the current struggle between the two superpowers of the twenty first century for global hegemony: the United States and China. The surveys used in this study have been previously described in a bulletin publication (Barsallo et al., 2025a,b), which provided contextual information and initial observations. The present article examines the controversial dispute over control of the ocean route and the Latin American region by analyzing two public opinion surveys. Particular attention is given to collective values such as historical memory, national identity, sovereignty, and the symbolic significance of the Panama Canal, which shape societal perceptions of this geopolitical issue. These values function as a defense mechanism in the context of President Donald Trump's statements, in which China is portrayed as a threat to U.S. national security and the Panama Canal is placed at the center of his offensive rhetoric. Such dynamics carry international implications of global scope.

In this sense, the offensive realism of Mearsheimer (2001) will be the theoretical framework used in this article to provide a political explanation around hegemony and power, indicating that the international system is anarchic therefore the states seek to maximize their power. However, most research using this theory has examined the behavior of major powers, rather than smaller states, this article will also focus on how the ordinary Panamanian reacts to this.

2 Theoretical framework: offensive realism

Offensive Realism is described in this section along with how it is applied to current power struggles. It connects the Panama Canal case to broader debates on hegemony, security, and how states compete for influence in the global order.

2.1 Offensive realism principles

Currently, international dynamics reflect a scenario of power struggles in which powers implement strategies to contain the advance of others. In this context, Popescu (2025), based on Kroenig (2020) analytical framework, identifies 2014 as the beginning of the era of disputes between the great powers. This period was characterized by China's expansion in the South China Sea through the construction of artificial islands. It was also marked by Russia's territorial expansionism, evidenced by the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. These developments contributed to reconfigurations in the security policies of other global powers, particularly the United States. To this, Mearsheimer (2021) argues that the case of China and the United States is an example of hegemonic competition and inevitable rivalry, as both powers seek to secure their sphere of dominance and influence.

These scenarios find their theoretical explanation in Offensive Realism (OR). It is a perspective that has been applied to analyze conflicts such as the one between Russia and Ukraine (Smith and Grant, 2022), the strategic rivalry between China and the United States (Mearsheimer, 2021), the ColdWar between United States and Russia (Labs, 1997), border and regional power disputes between China and India (Ahlawat and Hughes, 2018), etc.

This theory, developed by Mearsheimer (2001), argues that states, especially great powers, seek to maximize their control in order to survive in an anarchic international system where there is no higher authority to protect them (Smith and Grant, 2022). They seek to establish themselves as hegemonic powers in their geographical region and prevent the emergence of competitors (Romero, 2017). In this regard, Jordán (2018) points out that, according to Mearsheimer (2001), this behavior is ruled by five fundamental principles:

□ First principle: The international system lacks a central authority, so actors must ensure their own survival.

□ Second principle: States possess a degree of offensive military capability that allows them to destroy other states.

□ Third principle: States cannot be sure of the intentions of other states, which generates mistrust and preventive behavior.

□ Fourth principle: The goal of states is survival.

□ Fifth principle: States develop coherent strategies to maximize their chances of survival.

This framework provides analytical tools for understanding the behavior of major powers without endorsing specific state actions or policies.

2.2 Scenarios of offensive realism in the world

OR as a theoretical approach is based on the premise that the international system is anarchic (Mearsheimer, 2001), which has led to a struggle between powers that, from a historical perspective during the twentieth century, raises the issue of power play on a global scale. Proof of this is German and Japanese expansionism, which reflected an impulse of OR by maximizing security and power issues to ensure the survival of their foreign policy in the regional context of the world's largest continent in terms of territory and population. During this period of wars, both Germany and Japan acted under the logic of OR, pursuing regional hegemony through military expansion. In this regard, Christensen (1999) explains that the problem of security leads states to interpret the actions of others as threats, which in the interwar context succeeded in fostering impulses of expansion and confrontation.

Subsequently, there was the existing rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, which could be interpreted as a competition for hegemony during the Cold War (Mearsheimer, 2014). Later, during Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Iraq sought to expand its strategic resources and regional power, maximizing its power (Freedman and Karsh, 1993). Next, regarding the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, Toft (2005) explains how Mearsheimer's OR does not justify the invasion as such, as it differs from the US foreign policy at the time.

From another perspective, Dawood and Diniz (2024) argue that the application of Mearsheimer's OR to the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has been criticized for allegedly justifying Russian actions. However, the theoretical explanation differs fundamentally from moral support, arguing that academic analysis seeks to understand phenomena rather than approve specific behaviors.

Mearsheimer (2001) indicates that powers exercise control beyond their borders and in the face of threats from other rival powers, maximizing their power. NATO, for example, fits this logic, which prevents other powers considered hostile from accumulating strength by providing strategic advantages to those in the alliance and denying them to its competitors, and making it impossible for potential hegemonic powers to access alliance members while facilitating preventive actions that reduce the costs and risks of future conflicts (Kumar, 2023).

2.3 United States and its regional historical hegemony

In 1823, the United States announced the Monroe Doctrine under the slogan “America for Americans.” This doctrine served as the foundation for preventing European powers, particularly France and Britain, from attempting to reconquer the newly independent Latin American territories. It also represented an early expression of regional hegemonic ambition, as the United States sought to exclude the European influence from the Western Hemisphere and establish itself as the dominant power in the American Continent.

Taking into account Mearsheimer's argument as indicated by Jordán (2018), powers that achieve hegemony seek to prevent the emergence of competitors within their own region. The United States has designed and implemented actions that have sought to maintain and expand its hegemony in the region and globally in order to ensure its survival as a power in the international system. In this context, Romero (2017) indicates that, in the practice, the US has carried out various actions based on OR, using its coercive power, acting preventively, prioritizing US security in the face of challenges to its regional dominance through constant military interventions, armament provisions and accumulation of military capabilities, a policy of hegemonic expansion, and subverting the liberal democratic order.

During the Cold War, a period of conflict between the United States and the former Soviet Union, these countries promoted military coups against democratically elected governments that were considered a threat to national security in order to maintain control of the hemisphere. The most emblematic cases are Guatemala in 1954 (Rodríguez Minayo, 2020), Chile in 1973 (Carassai and Coleman, 2024); direct military invasions justified by slogans to protect US citizens in the Dominican Republic in 1965 (Harvey, 2020), Grenada in 1983 (Rivard, 1985), Panama in 1989 (Yao, 2009), support for counterrevolutionary movements such as the Contras in Nicaragua in the 1980′s (Kruijt, 2011), and through the support of death squads as in the case of El Salvador in the 1980′s (Velázquez, 2019), prioritizing its national security policy over human rights.

This is also asserted by Lajtman and García Fernández (2022), who state that the use of hemispheric security is nothing more than a mechanism of hegemonic control through hard power and soft power. As they indicate in their study, this has evolved, with the armed forces being used to impose internal order, access to resources, and internal or external deterrence. To this end, security policy evolved from the Inter American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (TIAR) in 1947 (Organization of American States, 1947). Each period has seen the security doctrine adjusted with a view to regional control, as the authors point out.

2.4 Latin America in the geopolitical game

According to Carbajal-Glass (2023) and Leyva Pérez (2023), the international order shows evidence of the decline of the unipolar system led by the United States during the twenty first century. In this context, Chhabra et al. (2020) identifies the People's Republic of China as the main competitor of the US, while Mearsheimer (2021) raises the possibility of an imminent confrontation between the People's Republic of China and the United States. Meanwhile, the People's Republic of China has managed to penetrate the Panamanian territory, the so-called “backyard” of the United States, by establishing trade agreements, infrastructure investments, and alliances with governments.

As an emerging power, China has made large investments in Latin America as part of its foreign policy strategy. Moretti and Fernández (2022) and Shinn and Eisenman (2020), indicate that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is related to the political objectives proposed by the eighteenth Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

The initiative, officially known as “The Belt and Road,” was a project that sought to revive the ancient Silk Road through infrastructure networks and trade connections in Eurasia, Africa, and Europe, according to Lávut (2018). Latin America was seen as a resourcerich region and a strategic market for Chinese growth.

As described by Lávut (2018), it is interesting to point out that Panama was one of the first nations to sign the memorandum of understanding in 2017 related to the BRI, breaking diplomatic relations with Taiwan (Formosa). As of today, between 2017 and 2025, 21 Latin American countries have joined the BRI, with Panama being the first country to join in June 2017 and resigning in 2025. Meanwhile, other countries such as Antigua and Barbuda, Bolivia, and Ecuador joined in 2018, Argentina and Nicaragua in 2022, Cuba and the Dominican Republic in 2019, and the most recent, Colombia in 2025 (Nedopil, 2025). According to Sun (2023) and Zhou and Luk (2016), with the BRI, China has included elements of soft power in the region through cultural and media outlets aligned with its interests and a network of 39 Confucius Institutes.

This presence poses a threat to hemispheric security. According to Tellería Escobar (2024), in March 2023, China and Russia were identified as the main threats to US security, describing them as malign actors. To counter what is considered a threat, the use of integrated deterrence (Tellería Escobar, 2024) was proposed, a nonviolent mechanism that seeks to curb the rise of other powers through various less violent strategies (Jordán, 2018). This approach proposes a multidisciplinary and multidomain treatment, with the support of the government, industry, the private sector, academia, and allies in the region.

This prospective analysis of the US situation in the region is a return to the nineteenth century Monroe Doctrine, whose principle of maintaining the sphere of influence against rival powers is its ideological and political foundation. This leads to the practice of OR (Jordán, 2018), whose strategy under the previous administration of former US President Joe Biden was to declare the region a “strategic base of operations” and promote “integrated deterrence,” as indicated by Vázquez Ortiz and Cruz Herrera (2023), through unconventional warfare, as a new, as yet unclassified scheme of regional control. It was also followed by President Trump who seems determined in his second term to directly challenge Chinese influence in Latin America, placing the region at the center of global hegemonic competition (De Benedictis, 2025).

2.5 Small power behavior and foreign policy

The Isthmus of Panama has historically been a space of imperial disputes because of its geographical location (Erazo-Patiño, 2025). Currently, this dynamic focuses on the Panama Canal as the epicenter of the dispute between two logics of power, representing the traditional geopolitical vision of the United States government, which conceived the Canal as a strategic-military asset as part of its hemispheric hegemony (Poland and Spalding, 2003; Valdés, 2021). Although this study considers OR as its primary theoretical foundation to explain the behavior of the Trump administration and its rhetoric about “retaking the Canal,” the framework remains limited because it overlooks the role and agency of small states such as Panama, a common shortcoming of realism (Espósito, 2019).

To broaden the vision of this case from Panama's position as a small power (behavioral concept) or small state (structural concept), we turn to the Dependency Theory applied to peripheral states. Small powers' foreign policy behavior reflects their subordinate position in the international system instead of pursuing independent agendas. They often align with or adapt to the interests of dominant powers to maintain aid, security, or access to markets (Fox, 2012). This is corroborated by the recent signing of the 2025 Memorandum of Understanding between the Panamanian Minister of Security and the US. Secretary of State that allows the reinstallation of US military bases in the Panama Canal, in deliberate violation of the Canal Neutrality Treaty.

These actions stem from concerns about how to prevent, lessen, or delay war as well as how to fend off greater force if it has already begun (Toje, 2010). More recently, Thorhallsson (2019) developed the Shelter Theory emphasizing that the political, economic, and social weakness leads small states to seek protection from great powers. The author argues that small states' foreign policy behavior reflects their structural dependence on larger powers and international frameworks, which limit their autonomy and shape their strategic choices, similar to that described in Dependency Theory.

2.6 The Panama Canal in the current regional context

The Panama Canal represents a distinctive element of identity and sense of belonging for the Panamanian population. It stands as a symbol of sovereignty and anticolonial resistance. In Smith's (1997) terms, this space located in the Panamanian isthmus can be understood as a “Historical Territory.” Its history has been closely tied to this transit zone, where the “Canal Zone” was established. For more than 90 years, this enclave remained under the jurisdiction of the U.S. government, functioning as a colonial territory between 1904 and 1999 (Pérez Ramos, 2025).

For Anderson (1993), this territory became a space of “fraternity and sacrifice,” around which claims for Panama's sovereign rights were articulated. These events include the Gesta de Inquilinato in 1925 (Moreno de Cuvillier, 2025), the rejection of the Bases Agreement or Filos-Haynes Treaty in 1947 (Pearcy Thomas, 1998), Operation Sovereignty in 1958 (Del Cid, 2016), Operation Flag Planting in 1959 (Sanchez, 2002), and, most emblematically, the Gesta del 9 de enero in 1964 (Centeno Jiménez, 2020). These events, later commemorated, contributed to strengthening the Panamanian collective imagination.

To complement this vision from a perspective of sovereign territory and national identity, and taking into account that since 1904 the Canal Zone was established as a border zone under US jurisdiction until 1999, Niño González and Jaramillo Ruiz (2018) assert that border security policies reshape perceptions of sovereignty and mold local identity narratives. This symbolic effect helps explain why external geopolitical statements about the Canal encounter strong popular resistance.

Building on this symbolic and identity-based reading, the Panama Canal transcends geopolitical and economic dimensions and becomes a conflict of symbolism and cultural representations. Two opposing views converge in this scenario: on the one hand, the view that interprets the canal as an emblem of US supremacy and security in the region, emphasizing the canal's importance for hemispheric security and global commercial interests. On the other hand, there is the conception that claims the Canal as a fundamental symbol of Panamanian national sovereignty and its identity as an independent state, highlighting its value as a tangible manifestation of national self-determination and the full exercise of territorial sovereignty.

The debate between these diverse visions illustrates how physical spaces can acquire multiple political and cultural meanings, transforming themselves into domains where not only material interests are contested, but also narratives about legitimacy, national identity, international projection, and global power hegemony.

3 Materials and methods

This article uses a comparative approach to examine Panamanian public perceptions regarding the recent US president statements about the Panama Canal. It compiles data from two distinct national survey waves that address Panamanian reactions on the statements performed by President Trump's declarations in early 2025. The present study uses secondary data. The datasets were transferred to the authors under an official data use agreement, as documented in the data access certificates available in each repository record. The authors were not involved in the data collection process. The datasets are publicly available in Mendeley Data.

Two datasets (Barsallo, 2025a,b) corresponding to public opinion surveys (or polls) conducted at two different times were analyzed. The first database originally contained (n = 947) responses, and the second contained (n = 732). Only four variables were common to both surveys, and these were used for the comparative analysis. In the first survey, 41 records lacked information for more than one of these variables and were therefore excluded, leaving 906 valid records in survey #1 and 732 in survey #2.

The analysis variables and their operationalizations were:

• Age in years, which was grouped into two groups ≤49 and >49;

• Reasons, the original question of which is: Why do you think President Trump has made these statements/demands? The options were five (5) multiple choice;

• Sufficient and complete: Do you consider that the information published in the media on these topics “President Trump's statements and demands” has been sufficient and complete to enlighten the Panamanian population? (4 level responses);

• Provinces, included 10 provinces and at least two regions, however, the largest proportion was concentrated in Panama (the country's capital), over 60% of the responses. The province of Panama concentrates around 39% of the country's population.

The analysis draws from two national opinion surveys. Survey #1 was administered on January 2025, coinciding with the immediate aftermath of President Trump's initial statements about the Panama Canal. It achieved broad national representation across Panama's provinces and indigenous territories. The sample comprised 394 males (41.6%), 514 females (54.3%), with 39 nonresponses (4.1%) for gender, and ages ranging from 18 to 75 years.

Survey #2 was conducted on April 2025, the capturing evolved public opinion 3 months later, allowing for assessment of temporal changes in public perception. It demonstrated similar national coverage with a slightly different gender distribution: 62% female participation and 38% male participation. Ages ranged from 18 to 75 years.

Both surveys show concentrated participation in Panama Province or Capital province (Survey #1: 62.83% and Survey #2: 64.8%), followed by Panama Oeste (Survey #1: 12.9% and Survey #2: 17.2%) in the second wave. This distribution pattern reflects the country's demographic concentration while maintaining representation from multiple provinces.

The temporal spacing between surveys provides a unique opportunity to examine the evolution of public opinion during a period of heightened diplomatic tension, enabling analysis of both immediate reactions and more considered responses to the geopolitical developments surrounding the Panama Canal sovereignty discourse.

In this article, the reported data were subjected to several statistical analyses in order to address the following research questions and objectives based on the theoretical framework and regional context:

• How can the recent statements and demands of the US government regarding the Panama Canal be interpreted in light of Mearsheimer's principles of offensive realism?

• How do the statements and demands of the US government regarding the Panama Canal relate to the national identity, sense of belonging, and perception of sovereignty of Panamanians?

Accordingly, the main objectives are:

• To analyze the practical application of Offensive Realism through the U.S. statements on the Panama Canal.

• To evaluate the relationship between identity, historical memory, and perceptions of sovereignty in shaping Panamanian responses;

• The analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics v.23 and the analytical approach included:

• Chi-square tests to examine differences in response distributions between Survey 1 (n = 906) and Survey 2 (n = 732) across categorical variables;

• Correspondence analysis to explore associations between survey waves, age groups (≤49 years vs. >49 years) and among the territory (provinces), perceptions on the media and the coverage of the current situation, and stated reasons for political declarations;

• Spearman's rank correlation to assess the relationship between national identity and sense of belonging measures related to the Panama Canal as part of the Panamanian territory. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Limitations in the original survey designs, such as question wording, sample representativeness, nonresponse bias, possible sampling bias, and temporal impacts between survey waves, may affect this secondary study. The study is restricted to variables from the original datasets, which might not include all pertinent components for a thorough theoretical analysis. Additionally, the use of secondary surveys imposes restrictions, as the instruments were not originally designed for this theoretical study. The short temporal frame between survey waves limits broader generalization, and the absence of detailed socioeconomic variables prevents deeper exploration of structural factors.

4 Results and discussion

The rhetoric employed by President Donald Trump under the principles of OR, expressing his intention to “take back the Canal” in order to contain the influence of a competitor within what he considers his historical sphere of influence, viewing China as a rival in this context, was directed primarily at the US audience on March 5, 2025 (Time Staff, 2025). This speech did not go unnoticed on the Panamanian side, where, as evidenced by the results of two opinion polls, the public identified President Trump's statements as part of the logic of US geostrategic interests.

In turn, these statements have encountered interesting resistance in the popular perception of Panamanians, where the Canal is not seen as strategic infrastructure, but as a symbol of national sovereignty and collective identity. To this, Anderson (1993) would say that the Panama Canal is an imagined community or, rather, a space where historical memory, anticolonial resistance, and national autonomy converge.

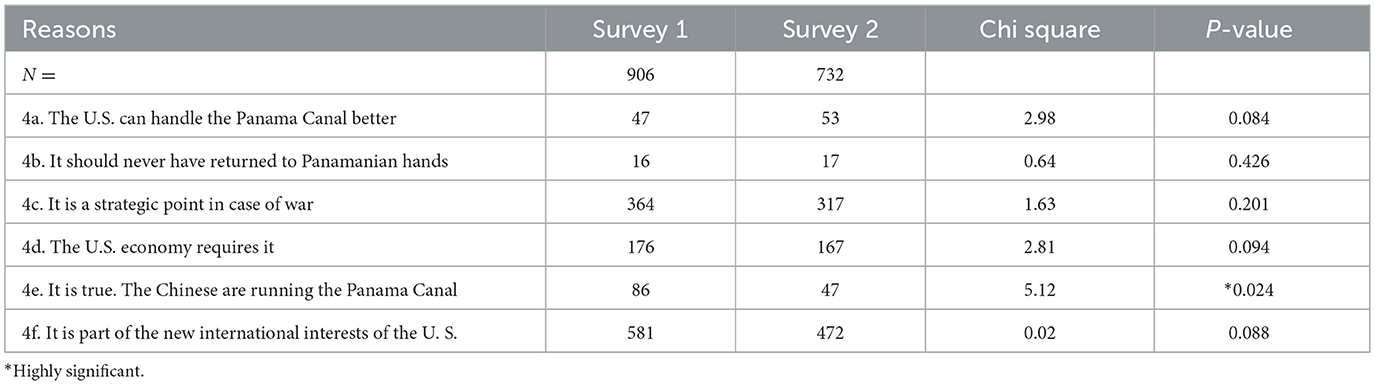

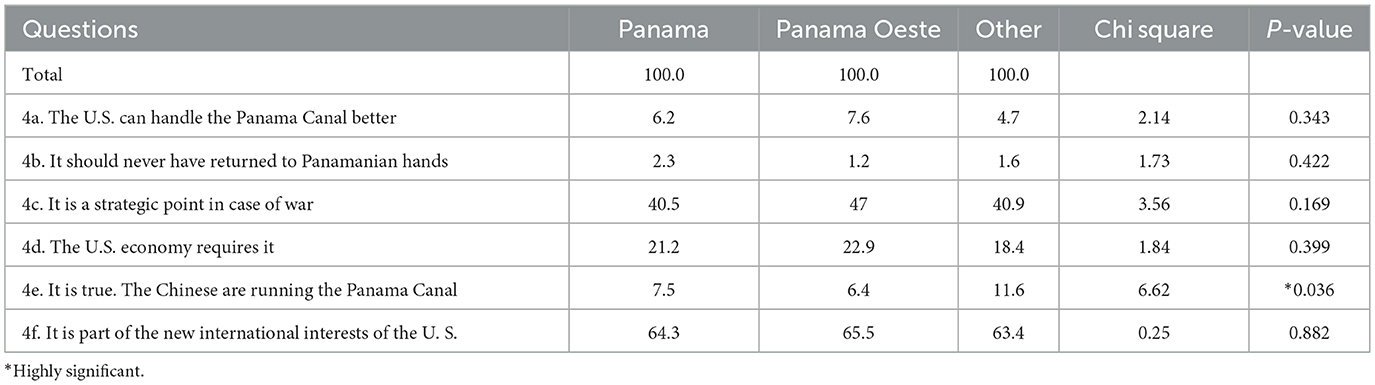

The arguments attempting to support President Trump's statements and demands showed no change in opinion between the two moments of the survey, with the exception of reason “4e. Because it's true. The Chinese are running the canal” (χ2 = 5.12; df = 1; p < 0.024) (Table 1).

Table 1. Statistical summary between the reasons for President Trump's statements and the surveys made.

The results suggest that the initial (survey 1) and subsequent (survey 2) narrative about the Chinese threat to the Canal may be losing credibility among Panamanians as time goes by. This finding is particularly relevant from the perspective of OR, as it suggests that, the justification based on the ‘Chinese threat' fails to gain traction as a convincing explanation for the local population in light of the abovementioned statements.

On a second occasion, a statistical association analysis was performed using the Chi-square statistic to observe differences between respondents‘ opinions regarding the reasons for President Trump's statements and the respondents' province of residence. Responses by province were divided into three groups according to the number of respondents represented in both surveys: the provinces of Panama, Panama Oeste, and Others. The first two provinces represent the capital and the next most populated province in the country. The last category, called Others, represents the remaining provinces.

The analysis revealed significant differences between provinces only in section 4.e (χ2 = 6.62; p = 0.036). In this case, a higher percentage of respondents from provinces other than Panama and Panama Oeste (11.6%) considered that “the Chinese are running the canal,” compared to 7.5% in the province of Panama and 6.4% in Panama Oeste (Table 2). The findings show clear results inclining the balance toward the provinces in the interior of the country.

Table 2. Percentage distribution of opinions, by province, according to the reasons given for President Trump's statements.

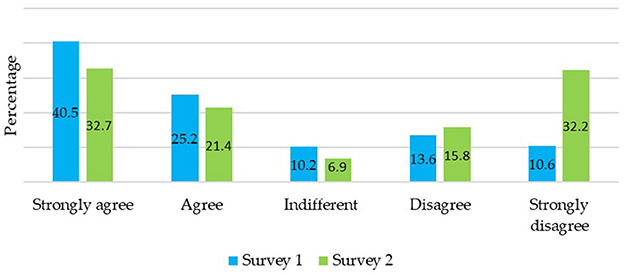

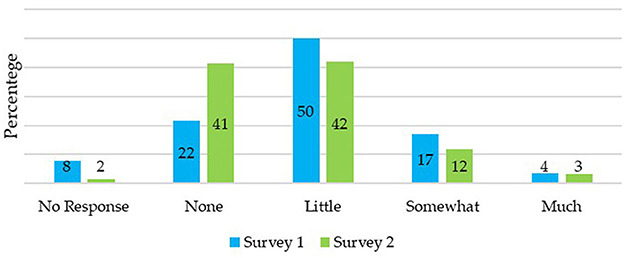

On the other hand, a comparison was made between surveys and the responses of Panamanians regarding the handling of information by the media, assessing whether it was sufficient and complete on the part of the United States using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. This analysis showed that there were statistically significant changes or differences in the responses between the two survey moments (U = 291785, p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Opinion on the sufficiency and completeness of the information published in the media, according to surveys.

These findings allow us to infer that the evolution in perception of media coverage reflects a process of maturation in public and individual analysis of the issue. The significant change between the two surveys shows that the Panamanian population has developed a more critical perspective on the quality and quantity of information available through the media.

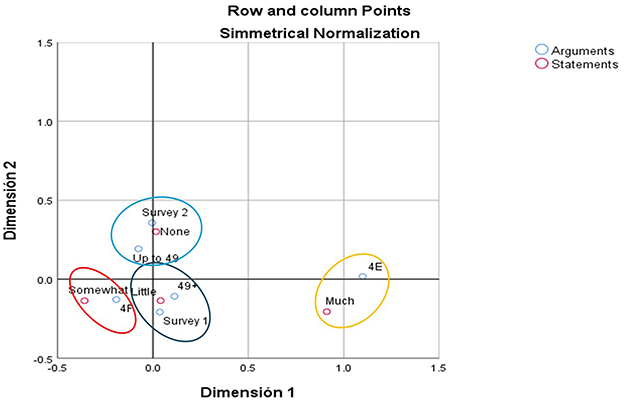

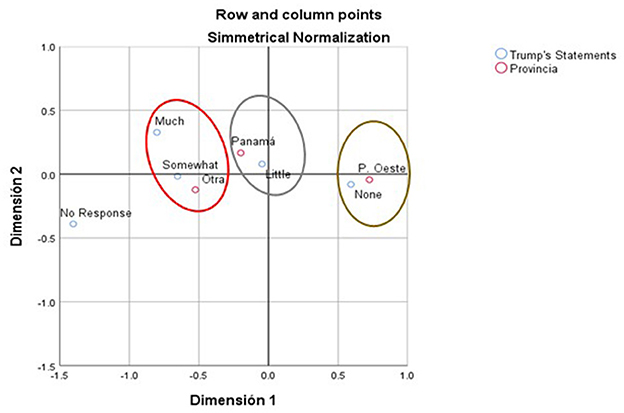

A correspondence analysis was performed between the respondents' answers (Figure 2), including the following:

• Survey 1 and Survey 2 (G1 and G2).

• Age grouped into two large groups: people aged 49 and under, and those over 49 (49 being the median age considering both sets of responses or surveys).

• Media coverage in terms of “sufficient and complete” information to inform the public about President Trump's statements (measured using a 4point Likert scale).

○ The reasons why President Trump made such statements and demands. The two main reasons:

• 4E. Because it is true. The Chinese are running the Canal.

• 4F. Because it is part of the new international interests of the United States.

The results of the correspondence analysis show that in survey 1, the information published in the media was “little,” according to those over 49 years of age. Those aged 49 and under in survey 2 considered this information to be ‘nothing' or “none.” However, those who considered that there was “quite a lot” of information gave as their reason for these statements that the Panama Canal “is part of the new international interests of the United States”; and they indicated “a lot” of information or being sufficiently informed that “it is true. The Chinese are running the Canal.”

These results reveal generational and media consumption patterns that have influenced the interpretation of the statements. Older groups tend to consider media information insufficient, while younger groups perceive a total absence of information that satisfies them. This suggests different expectations and sources of information between generations, which has important implications for the formation of public opinion on issues of national sovereignty.

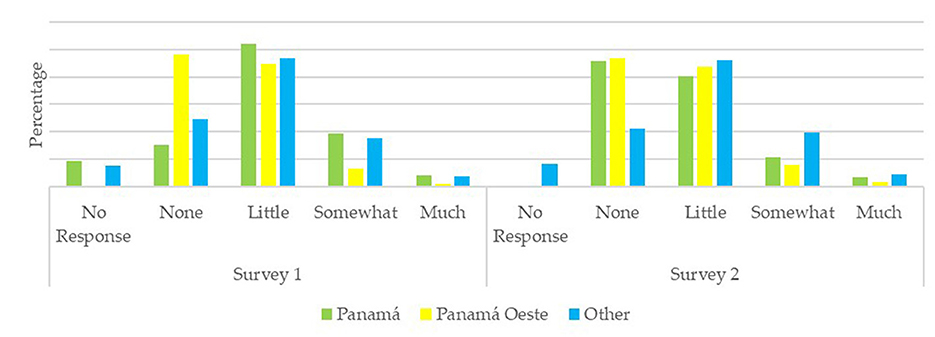

On the other hand, differences in opinion regarding the media's handling of President Trump's statements were compared by province and survey (time of survey), with statistical significance observed at both times of the survey (p < 0.001). This shows that the media's coverage of the adequacy and completeness of these statements showed differences in the population, according to province, on both occasions when the survey was conducted (Figure 3). Similarly, at the global level, this association between the perception of the statements published by the media and the provinces remains.

Figure 3. Percentage distribution of opinions regarding information management according to province and survey.

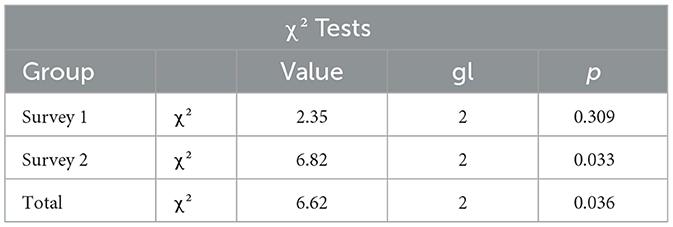

The differential analysis with respect to item 4e, by province and survey, showed statistically significant differences in the second survey (χ2=2.35; gl = 2, p = 0.309), but not in the first survey (p < 0.309) (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of the statistical significance of the association between subsection 4.E and provinces, according to survey.

A final simple correspondence analysis was conducted to compare the sufficiency and completeness of information published in the media regarding President Trump's statements (Figure 4). The analysis considered three groups of provinces in the country: Panama (65.3%), Panama Oeste (15.2%), and Others (19.5%). Statistical significance was verified (χ2 = 23.687, gl = 8, p = 0.003). The results showed that Dimension 1 explained 99.7% of the variance, while Dimension 2 accounted for only 0.3%. Therefore, Dimension 1 represents the main axis of the analysis. The association between the province of Panama Oeste and the responses of “none” can be highlighted. In other words, they perceived little information from the media regarding Trump's statements. Respondents from the province of Panama perceived little information (in terms of sufficiency and completeness), while those from other provinces associated it with the responses “somewhat” and “much.” Nonresponses were not relevant in the overall structure of the analysis. These results are significant because the role of media in shaping how the population interprets the statements and the underlying reasons associated with them is highlighted.

Figure 4. Factorial map that represents the management of information by the media in terms of sufficiency and completeness about the statements of President Trump and provinces.

Regarding the national identity of Panamanians and their sense of belonging, two key questions related to the Panama Canal were analyzed from the first survey. Participants were asked: How identified do you feel with the Panama Canal? and their degree of agreement with the expression: The Channel is yours, it is mine, it belongs to everyone!

Based on the responses, it was concluded that the higher the score, the greater the degree of identity and/or agreement. Spearman's correlation analysis (Table 4) was applied to verify the association between identification with the Canal and the sense of collective belonging. Spearman's correlation analysis between Identification and Expression was used to verify the degree of association between both questions, whose measurement scales were ordinal type with scales respectively. The results showed 10 and 5, a value of rs = 0.591, with high statistical significance (p < 0.001). Reaffirming the identity of the Panamanian with the Panama Canal. This confirms that the Canal is not only an work of infrastructure and operational logistics but also, as Smith (1997) argues, part of a historical territory filled with meanings derived from struggles that shaped the national myth.

Regarding Panamanians' perceptions of two statements about the Panama Canal, in survey 1: “The Canal is yours, it is mine, it belongs to everyone!” and survey 2: “The Canal will continue to be ours in the future,” it is possible to identify a collective belief, with a high degree of certainty, that the Panama Canal will indeed continue to belong to Panamanians (Figure 5). It should be noted that the statement in survey 1 represents Panamanians' sense of belonging in the present, and the statement in survey 2 represents Panamanians' sense of belonging and their vision of the future.

5 Conclusions

This study has examined President Donald Trump's statements on the Panama Canal through the lens of Mearsheimer's Offensive Realism. In this way, it has provided empirical evidence on the power dynamics in the contemporary hegemonic rivalry between the United States and China, putting into context the historical importance of the interoceanic route of the Panama Canal. The findings contribute significantly to the understanding of how international relations theories and their geopolitical strategies manifest themselves in specific regional contexts and impact the formation of public opinion.

The results presented in this article show that President Donald Trump's statements referring to the Panama Canal, the territory it occupies, and insinuations about its management are an example of Offensive Realism. In this particular case, OR is perpetrated through his statements and actions that seek to contain and reverse China's presence in the region where Panama plays a key role. However, these actions did not affect the respondent's perception. On the contrary, both surveys show that values such as identity and sense of belonging linked to historical memory are strong elements in the issue of sovereignty over the Panama Canal.

The main result confirms the practical application of the principles of OR in maximizing power in the face of perceived hegemonic threats. Statistical analysis revealed that most respondents interpreted these statements as part of the “new international interests of the United States,” validating Mearsheimer's theory on the preventive behavior of hegemonic powers.

The temporal dimension of the analysis demonstrated the evolution of public perceptions, evidencing a significant decline in the credibility of the narrative about the “Chinese threat.” It was observed that narratives focused on external threats do not indefinitely maintain their power of popular conviction, contradicting theoretical expectations about the sustainability of discourses of control and protection.

The study revealed a strong correlation between national identification with the Panama Canal and a sense of collective belonging, confirming Anderson's (1993) and Smith's (1997) conceptualization of imagined communities and their role in the construction of national identity. This result is particularly relevant to the theory of national identity, as it demonstrates how territorial symbols transcend their operational function to become elements that constitute the collective imagination.

The provincial differences identified suggest that political geography also influences perceptions of external threats. This is evidenced by the provinces in the interior of the country showing greater susceptibility to narratives about Chinese influence. This pattern can be explained by differences in access to information, socioeconomic contexts, and proximity to centers of political power.

Findings on media consumption exposed distinctive generational patterns in the evaluation of news coverage. It was evident that different age cohorts have divergent expectations regarding the quality and quantity of information needed to form opinions on issues of national sovereignty. This has important implications for political communication theory in contexts of geopolitical crisis.

This study contributes to academic literature by providing empirical evidence of the applicability of Offensive Realism in contexts of states with limited territory and population, while expanding the traditional theoretical scope focused on great powers. Its theoretical implications applied to the Panamanian case suggest that the effectiveness of Offensive Realism as a hegemonic strategy may be limited by the use of identity symbols as mechanisms of political defense. Future lines of research could explore comparative cases in other Latin American contexts, including the role of social media in shaping opinions on territorial sovereignty.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the Panama Canal functions simultaneously as an object of geopolitical dispute and as a symbol of national cohesion, highlighting the complexity of power dynamics in the contemporary international system. The Panamanian popular response, characterized by the maintenance of sovereignist perceptions despite hegemonic pressures, illustrates how national identity can become a significant political resource in the context of the reconfiguration of the world order.

The research has methodological limitations that should be considered in future research. The cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of definitive causal relationships, and geographical representativeness could be expanded to improve the quantities of marginal rural populations. Likewise, the absence of detailed socioeconomic variables limits the understanding of structural factors that could influence the perceptions analyzed.

In practical terms, future studies could complement quantitative data with qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups to capture discourses of identity more deeply. From a policy perspective, reinforcing civic education and historical memory around the Canal may strengthen national cohesion and resilience against external hegemonic pressures.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Barsallo, Gabisel (2025a), “Es el Canal de Panama de los panameños?”, Mendeley Data, V2, https://10.17632/925n6xk2z2.2 – Barsallo, Gabisel (2025b), “Lo que demanda el Presidente Trump de Panama”, Mendeley Data, V1, https://10.17632/h4ttcxrf67.1.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

VO: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GB: Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EM: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. RY-O: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The APC was funded by Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Posgrado, Universidad de Panamá.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this article for superficial text editing (e.g., grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting).

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahlawat, D., and Hughes, L. (2018). India–China stand-off in Doklam: aligning realism with national characteristics. Round Table 107, 613–625. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2018.1530376

Anderson, B. (1993). Comunidades Imaginadas: Reflexiones Sobre el Origen y La Difusión Del Nacionalismo. Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2nd Edn. Available online at: https://www.felsemiotica.com/descargas/Anderson-Benedict-Comunidades-imaginadas.-Reflexiones-sobre-el-origen-y-la-difusión-del-nacionalismo.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Barsallo, G. (2025a). Es el Canal de Panama de los panameños? Mendeley Data, V2, doi: 10.17632/925n6xk2z2.2

Barsallo, G. (2025b). Lo que demanda el Presidente Trump de Panama, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/h4ttcxrf67.1

Barsallo, G., Mendoza, E., Yanis-Orobio, R., and Ortíz Salazar, V. (2025a). Análisis de Coyuntura, Vol. 19. Instituto de Estudios Nacionales, Universidad de Panamá.

Barsallo, G., Mendoza, E., Yanis-Orobio, R., and Ortíz Salazar, V. (2025b). Análisis de Coyuntura, Vol. 20. Instituto de Estudios Nacionales, Universidad de Panamá. Available online at: https://iden.up.ac.pa/sites/instestudiosnacionales/files/2025-02/Análisis%20de%20coyuntura%20Vol.19.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Carassai, S., and Coleman, K. (2024). Reexaminando los golpes de estado en la tardía Guerra fría en América Latina. Índice Histórico. Español. 137, 18–44. doi: 10.1344/IHE2024.137.2

Carbajal-Glass, F. (2023). Riesgo político, seguridad y geopolítica: América Latina y la competencia estratégica Estados Unidos-China. URVIO Rev. Lat. Estud. Segur. 36, 104–117. doi: 10.17141/urvio.36.2023.5842

Centeno Jiménez, M. (2020). La ruta archivística: “Panamá, 9 de enero de 1964”. Cátedra 17, 80–92. doi: 10.48204/j.catedra.n17a6

Chhabra, T., Doshi, R., Hass, R., and Kimball, E. (2020). Global China: Regional Influence and Strategy. SB: Brookings. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FP_20200720_regional_chapeau.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Christensen, T. J. (1999). China, the US-Japan alliance, and the security dilemma. Int. Secur. 23, 49–80. doi: 10.1162/isec.23.4.49

Dawood, L., and Diniz, E. P. L. (2024). The realist debate in the context of the war in Ukraine: balancing dynamics, international change and strategic calculus. Rev. Bras. Polít. Int. 67:7329202400105. doi: 10.1590/0034-7329202400105

De Benedictis, M. (2025). Patear el tablero: Donald Trump y su vínculo con América Latina. Boletín del Departamento de América Latina y El Caribe, 91, 1–10. Available online at: https://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.19185/pr.19185.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Del Cid, J. (2016). El Relato de Los Héroes (1940–1960): La Operación Soberanía. Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Panama, Panama.

Erazo-Patiño., L. A. (2025). “Visión estratégica de Panamá: entre la búsqueda de su identidad nacional y la injerencia extranjera,” en Seguridad y Defensa. Estudios de Caso Desde La Cultura y el Pensamiento Estratégico, eds. C. E. Álvarez Calderón, F. N. Cufiño Gutiérrez, E. F. Orozco Becerra, and G. A. Orozco Becerra (Bogota: Sello Editorial ESMIC), 191–216. doi: 10.21830/9786289640281.08

Espósito, S. (2019). Estados pequeños en el sistema internacional: estrategias de proyección y espacios de incidencia. (Bachelor thesis), Universidad de San Andrés. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10908/18759

Fox, A. (2012). The Power of Small States: Diplomacy in World War II. The Influence of Small Powers, University of Chicago Press. 180-188. Available online at: https://www.diplomacy.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/powerofsmallstat001511mbp.pdf doi: 10.1515/9780295802107-002 (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Freedman, L., and Karsh, E. (1993). The Gulf Conflict, 1990-1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Harvey, H. (2020). Revisitando el punto de inflexión interamericano en la guerra fría: la crisis dominicana de 1965, la intervención de estados unidos y la fuerza interamericana de la paz. Hum. Revista Univ. 27, 25–63. doi: 10.25185/7.2

Jordán, J. (2018). El conflicto internacional en la zona gris: una propuesta teórica desde la perspectiva del realismo ofensivo. Rev. Esp. Cienc. Polít. 48, 129–151. doi: 10.21308/recp.48.05

Kroenig, M. (2020). The Return of Great Power Rivalry: Democracy Vs. Autocracy From the Ancient World to the US. and China. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190080242.001.0001

Kruijt, D. (2011). Revolución y Contrarrevolución: el Gobierno Sandinista y la Guerra de la Contra en Nicaragua, 1980-1990. Desafíos 23-II, pp. 53-81. Available online at: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3596/359633170008.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Kumar, A. (2023). An analytical study of Russia-Ukraine war in reference to the offensive realist approach in international relations. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 18, 926–933. doi: 10.30574/wjarr.2023.18.3.0906

Labs, E. J. (1997). Beyond victory: offensive realism and the expansion of war aims. Secur. Stud. 6, 1–49. doi: 10.1080/09636419708429321

Lajtman, T., and García Fernández, A. (2022). Dependência estratégica dos estados unidos e militarização na América Latina. Rev. Estud. Pesq. Sobre Am. 15, 62–83. doi: 10.21057/10.21057/repamv15n2.2021.36677

Lávut, A. A. (2018). La iniciativa China “la franja y la ruta” y los países de América Latina y el caribe. Iberoamérica 2, 42–67. Available online at: https://dar.org.pe/archivos/publicacion/205_informe_grefi.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Leyva Pérez, R. (2023). De Obama a Biden: continuidad y ruptura en la estrategia de contención de EE.UU. frente a China. Polít. Int. 4, 185–205. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.8422893

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2014). Why the Ukraine crisis is the West's fault: the liberal delusions that provoked Putin. Fore. Aff. 93, 77–89. Available online at: https://www.mearsheimer.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Why-the-Ukraine-Crisis-Is.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2021). The inevitable rivalry: America, China, and the tragedy of great-power politics. Fore. Aff. 100:48. Available online at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-10-19/inevitable-rivalry-cold-war (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Moreno de Cuvillier, L. (2025). La huelga inquilinaria de 1925. ¿Qué se ha dicho y escrito sobre ella?. Rev. Panameña Cienc. Soc. 9, 137–144. doi: 10.48204/2710-7531.7107

Moretti, L., and Fernández, V. R. (2022). La lógica geopolítica del Estado chino y la Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta en la Argentina. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 42, 135–158. Available online at: https://biblioteca-repositorio.clacso.edu.ar/bitstream/CLACSO/171369/1/revista-42.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Nedopil, C. (2025). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2024. Griffith Asia Institute and Green Finance & Development Center, FISF, Brisbane. doi: 10.25904/1912/5784

Niño González, C. A., and Jaramillo Ruiz, F. (2018). Una aproximación geopolítica a la política binacional de seguridad fronteriza entre Colombia y Panamá. Ópera 23, 81–96. doi: 10.18601/16578651.n23.06

Organization of American States (1947). Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (Rio Treaty). Signed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Depositary: Pan American Union. Entered into force December 3, 1948. Available online at: https://www.oas.org/juridico/english/treaties/b-29.html (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Pearcy Thomas, L. (1998). We Answer Only to God: Politics and the Military in Panama 1903-1947. Alburquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Pérez Ramos, P. (2025). Historia de la construcción del Canal de Panamá. Tesis de Licenciatura. Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife. Available online at: http://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/42685 (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Poland, J. L., and Spalding, S. (2003). Emperadores de la Jungla: La Historia Escondida de Estados Unidos en Panamá. Panamá: Instituto de Estudios Nacionales.

Popescu, I. (2025). No Peer Rivals: American Grand Strategy in the Era of Great Power Competition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.12393858

Rodríguez Minayo, M. N. (2020). El intervencionismo de los Estados Unidos en Guatemala durante la Guerra Fría. Tesis de grado. Universidad de Valladolid. Available online at: http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/45716 (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Romero, R. (2017). Realismo ofensivo, base de la política exterior de los EE. UU. hacia Latinoamérica. ECA Estud. centrom. 72, 277–295. doi: 10.51378/eca.v72i750.3257

Sanchez, P. M. (2002). The end of hegemony? Panama and the United States. Int. J. World Peace 19, 57–89. doi: 10.2307/20753364

Shinn, D. N., and Eisenman, J. (2020). Evolving principles and guiding concepts: how China gains African support for its core national interests. Orbis 64, 271–288. doi: 10.1016/j.orbis.2020.02.009

Smith, A. (1997). La Identidad Nacional. Editorial Trama. Available online at: http://bivir.uacj.mx/Reserva/Documentos/rva2006156.pdf (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Smith, N. R., and Grant, D. (2022). Mearsheimer, realism, and the Ukraine War. Ann. Uk. Stud. 44, 175–200. doi: 10.1515/auk-2022-2023

Sun, S.-C. (2023). The confucius institutes: China's cultural soft power strategy. J. Cult. Values Educ. 6, 52–68. doi: 10.46303/jcve.2023.4

Tellería Escobar, L. (2024). El Comando Sur y los actores malignos: protección regional o continuidad del dominio estadounidense? Polít. Int. (La Habana) 6, 221–233. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.13857145

Thorhallsson, B. (2019). Small States and Shelter Theory: Iceland's External Affairs. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429463167

Time Staff (2025). Read the transcript of Trump's 2025 speech to Congress Here [Speech transcript]. Time. Available online at: https://time.com/7264688/trump-speech-congress-2025-transcript/ (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Toft, P. (2005). John J. Mearsheimer: an offensive realist between geopolitics and power. J. Int. Relat. Dev. 8, 381–408. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065

Toje, A. (2010). The European Union as a Small Power: After the Post-Cold War. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230281813

Valdés, F. (2021). Roles que ha desempeñado el Canal de Panamá, 1914 - 2020. Rev. Cient. Orb. Cógn. 5(2), 95–110. Available online at: https://revistas.up.ac.pa/index.php/orbis_cognita/article/view/2323 (Accessed September 1, 2025).

Vázquez Ortiz, Y. B., and Cruz Herrera, L. (2023). Estados Unidos-América Latina: Guerra no Convencional, disuasión integrada, integración cívico-militar y cooperación, 07, 31–44. Available online at: http://www.cna.cipi.cu/cna/article/view/146

Velázquez, N. B. (2019). Las buenas intenciones no bastan: la política exterior de Estados Unidos hacia América Latina en el siglo XX. Histórica 43, 113–154. doi: 10.18800/historica.201901.004

Keywords: offensive realism, national identity, geopolitics, Panama Canal, perception of sovereignty

Citation: Ortiz V, Barsallo G, Mendoza E and Yanis-Orobio R (2025) Sovereignty and national identity: the Panamanian perception of the canal and US foreign policy. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1713340. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1713340

Received: 25 September 2025; Accepted: 15 October 2025;

Published: 05 November 2025.

Edited by:

Jonnathan Jimenez-Reina, Escuela Superior de Guerra (ESDEG), ColombiaReviewed by:

César Niño, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, ColombiaEduardo Tzili Apango, Autonomous Metropolitan University Xochimilco Campus, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Ortiz, Barsallo, Mendoza and Yanis-Orobio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gabisel Barsallo, Z2FiaXNlbC5iYXJzYWxsby1hQHVwLmFjLnBh

Victor Ortiz1

Victor Ortiz1 Gabisel Barsallo

Gabisel Barsallo