- 1Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Macao Polytechnic University, Macao, China

- 2School of Mathematics and Statistics, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, China

While cross-border cooperation is a vital governance model for transnational challenges, many initiatives ultimately fail. Existing research exhibits a “cooperation bias,” focusing more on the conditions for success than on the systemic causes of failure, thus leaving a significant research gap. To address this gap, this study follows the PRISMA guidelines and employs a systematic literature review to conduct an in-depth thematic analysis of 138 academic articles specifically documenting cases of cross-border governance failure. The findings reveal that governance failures can be classified into an integrative typology comprising three core dimensions: (1) institutional design failure (e.g., hollowed-out implementation and monitoring, fragmentation of authority and responsibility); (2) political dynamics failure (e.g., primacy of national interests and sovereignty, asymmetric power relations); and (3) socioeconomic contextual failure (e.g., resource and capacity gaps, normative and cultural conflicts, and scale mismatches between problem and its governance). This study’s primary contribution is the systematic construction of an analytical framework for cross-border governance failure. By engaging in a critical dialogue with mainstream governance theories, the research challenges their inherent “cooperation bias” and argues that a profound understanding of failure is essential for both theoretical advancement and the construction of more resilient governance models.

1 Introduction

In an era defined by globalization and interdependence, cross-border cooperation has been widely established as the core governance paradigm for addressing transnational challenges (Hooghe and Marks, 2003). Issues ranging from ecological concerns like climate change and transboundary pollution to socioeconomic matters such as global supply chain disruptions and public health security inherently possess a complexity and cross-border nature that exceeds the capacity of any single sovereign state to manage alone. This makes collaborative governance a normative imperative (Young, 2002). Accordingly, a series of mainstream governance theories has provided a robust intellectual foundation for this ideal of cooperation. The analytical framework of multi-level governance (MLG) theory illuminates the dispersion and interaction of authority across supranational, national, and sub-national tiers, offering a pathway to understand the formulation and execution of cross-border policies (Stephenson, 2013). Network governance theory, in turn, emphasizes the effectiveness of flexible coordination through mechanisms like trust, reciprocity, and social capital—operating outside of hierarchy and markets—which is particularly suited for tackling complex problems marked by high uncertainty (Jones et al., 1997). Together, these theories have constructed an optimistic forecast: that through well-designed institutional arrangements and sustained social interaction, actors can effectively overcome collective action problems to achieve Pareto optimality. In practice, achievements from European Union integration to the establishment of various transboundary river basin management committees seem to affirm the viability of this cooperative vision (He et al., 2024).

However, a profound tension exists between this normative theoretical landscape and a large body of empirical evidence. Running parallel to the widely cited success stories is a more pervasive, yet often overlooked, reality: a vast number of cross-border cooperative initiatives encounter severe implementation deficits, prolonged stagnation, functional distortion, or even outright failure (Howlett and Ramesh, 2014). This “reality of failure” is not an occasional deviation or an isolated event, but a structural phenomenon that recurs across different geographical regions and issue areas. When the EU-US Privacy Shield agreement, designed to protect shared data privacy, was invalidated due to irreconcilable legal conflicts, or when border management projects aimed at promoting regional peace were stymied by the prioritization of national security logic, we are forced to confront a critical question: To what extent does the elegant logic depicted by cooperation theories obscure the deep-seated conflicts and fractures of the real world? This chasm between the ideal and the reality constitutes the logical point of departure for this study, demanding that we treat “failure” with theoretical seriousness and conduct a systematic inquiry into its underlying mechanisms.

Despite a wealth of research on cross-border governance, the mainstream narrative is marked by a significant “cooperation bias.” The research agenda has been largely dominated by the question of “how to foster cooperation,” leading to a systematic emphasis on analyzing successful cases and identifying enabling factors (Medhekar and Haq, 2022). Studies that do explore failure are often conducted as individual case studies, with explanations confined to context-specific variables such as leadership changes, funding disruptions, or sudden political conflicts. This orientation has resulted in the fragmentation of knowledge: while we have accumulated numerous disparate narratives on why specific initiatives failed, we have not developed a systematic body of knowledge on how they fail. Unlike previous studies that have primarily produced descriptive lists of barriers specific to single sectors (e.g., trade or water), there is a scarcity of integrative typologies that conceptually categorize these barriers into a coherent system of failure mechanisms applicable across different domains. Consequently, academia still lacks an integrative analytical framework that transcends cases, domains, and regions to conceptualize governance failure and identify its recurring, common mechanisms and patterns. This research gap not only limits a deeper understanding of the inherent vulnerabilities within governance systems but also impairs our ability to derive generalizable theoretical insights and practical lessons from failure.

To systematically address this research gap, this paper aims to answer the following three progressive research questions: First, what are the key mechanisms that lead to the failure of cross-border governance? Secondly, can these numerous and complex mechanisms of failure be categorized into a set of common, typical patterns or types? Thirdly, what are the theoretical implications of these systematic findings on failure mechanisms and patterns for understanding, critically reflecting upon, and advancing existing mainstream governance theories?

In response to these questions, this paper puts forward the following core argument: the failure of cross-border governance is not a random, unpredictable event. Rather, it stems from systemic mismatches, conflicts, and negative feedback loops among various mechanisms within three core dimensions: institutional design, political dynamics, and the socioeconomic context. Through a systematic literature review (SLR) of 138 cases of cross-border governance failure from around the globe, this study will construct an integrative analytical framework and a typology to explain such failures. We expect that this research will not only provide a clear analytical map of why cooperation fails but also foster a critical dialogue with existing governance theories, thereby deepening the understanding of the complexity of “governance” as a core concept.

This study’s core contribution is to provide the first systematic, empirically-based typology of cross-border governance failure, developed through a rigorous SLR. This typology moves beyond scattered descriptions of failure, aiming to uncover the common mechanisms and structural roots of governance collapse. In doing so, it theoretically deepens our understanding of the inherent vulnerabilities and the logic of “fracture” within governance systems. By moving “failure” from the periphery to the center of analysis, this paper seeks to correct the prevalent “cooperation bias” in existing governance theories and to offer a new analytical perspective for assessing and designing more resilient governance arrangements.

To systematically present this research, the paper is structured as follows: chapter two details the research methodology, including the design of the systematic literature review, the specific procedures for literature retrieval and screening (following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, PRISMA), and the coding and thematic analysis framework applied to the final corpus of 138 core articles. Chapter three presents the core findings, detailing the typology of cross-border governance failure derived from the literature. It provides in-depth explanations and illustrations for nine specific failure mechanisms organized around the three core dimensions: institutional design, political dynamics, and the socioeconomic context. Chapter four offers an in-depth discussion of these findings. It not only explores the interlinkages among the different failure mechanisms to construct an integrative framework but also reflects on the theoretical implications of the findings for mainstream governance theories. Furthermore, it provides practical insights for policymakers on building “resilient governance.” The final chapter concludes by summarizing the paper’s central arguments, acknowledging the study’s limitations, and proposing specific directions for the future research agenda.

2 Research methods and data

2.1 Systematic literature review (SLR) framework

To systematically answer the research questions regarding the key mechanisms, typical patterns, and theoretical implications of cross-border governance failure, this study employs the method of a systematic literature review SLR. Compared to a traditional narrative review, an SLR is a more rigorous, transparent, and replicable research method that aims to comprehensively identify, evaluate, and synthesize all relevant evidence within a specific research area through a clearly predefined process (Tranfield et al., 2003). Given that the objective of this research is not merely to describe existing literature but to distill a common analytical framework and typology from a large number of disparate cases, the SLR method is ideal for minimizing researcher selection bias and ensuring the systematic nature and robustness of the findings.

The entire review process strictly adheres to the guidelines provided by the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021). The PRISMA guidelines offer a clear, evidence-based reporting framework for the entire process of literature retrieval, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion, and it has become the gold standard for high-quality literature reviews in the social sciences (Liberati et al., 2009). Following these guidelines ensures that every step of our research is traceable and verifiable, thereby providing a solid methodological foundation for the reliability of our conclusions. Specifically, our research process comprised three core stages: first, defining a clear literature search strategy and scope; second, executing a systematic literature screening and assessment process; and third, conducting systematic data extraction and thematic analysis on the finally included articles. The subsequent sections will elaborate on these stages in detail.

2.2 Literature search, screening, and final sample

2.2.1 Literature search strategy

The literature search for this study was completed on August 12, 2025, using the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection. This database is considered an authoritative source for high-quality systematic reviews due to its extensive journal coverage and stringent inclusion criteria. While we acknowledge the existence of other databases like Scopus and the value of grey literature (e.g., government reports), the decision to rely exclusively on the WoS Core Collection was strategic. Our objective was to construct a theoretical typology based on rigorously peer-reviewed empirical evidence to ensure the methodological robustness of the identified failure mechanisms. WoS is widely recognized for its high standards of indexing, which helps minimize the inclusion of predatory or low-quality publications. Furthermore, for the purpose of conceptual framework construction, the goal was to achieve theoretical saturation through high-quality representative cases rather than to conduct an exhaustive census of all existing reports. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the search, no upper limit was placed on the publication year of the articles. The search strategy was designed as a multi-tiered and complementary system aimed at comprehensively capturing academic literature related to cross-border governance from multiple dimensions, including core concepts, theoretical foundations, key issues, and governance challenges. The detailed search strategy and query strings are provided in Table 1.

2.2.2 Literature screening and final sample

The literature screening process strictly followed the PRISMA guidelines, with the specific workflow illustrated in Figure 1. The multi-tiered search strategy described above initially retrieved 4,746 articles from the database. First, after merging all search results using reference management software, we removed 642 duplicate articles, which resulted in 4,104 unique records.

Subsequently, the screening was conducted in two stages. The first stage (initial screening) involved a review of titles and abstracts. The following inclusion criterion was applied: the article had to be related to governance, cooperation, or collaboration within a cross-border or transboundary context. At this stage, a large number of articles with clearly irrelevant topics were excluded. The second stage (detailed screening) consisted of a full-text review. Articles that passed the initial screening underwent a full-text assessment to determine if they met the study’s final inclusion criterion: the article must explicitly discuss, in the form of empirical analysis or a case study, one or more specific situations in which cross-border collaborative governance failed, reached a deadlock, triggered conflict, or was proven to be ineffective. This criterion was designed to precisely focus the research sample on “cases of failure,” thereby serving the central research questions of this paper. It is important to clarify that this study adopts a broad, functionalist definition of ‘failure’. We do not limit our analysis to the complete collapse of cooperative agreements. Instead, our operational definition explicitly includes ‘functional failure’, which encompasses prolonged stagnation, gridlock in decision-making, and the inability to achieve core policy objectives despite the continued formal existence of the institution. To ensure consistency and minimize selection bias, the entire screening process was conducted by two researchers working independently. Any disagreements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of an article at either stage were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Following this rigorous screening process, a final total of 138 articles were included for systematic analysis in this study. Together, these articles form the core database for constructing the typology of cross-border governance failure.

2.3 Thematic analysis and coding framework

To systematically extract and synthesize the core mechanisms of cross-border governance failure from the 138 included articles, this study employed the method of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis is a flexible and powerful qualitative method, particularly well-suited for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (or “themes”) within a diverse dataset.

The analytical process followed an iterative coding workflow, moving from specific details to abstract concepts. First, we conducted open coding on the core arguments concerning the causes of failure in each article. At this stage, we stayed closely grounded in the source text, using short phrases or sentences to distill the direct reasons for failure in each specific case. Examples of such initial codes include “lack of effective dispute resolution mechanisms,” “unilateral actions by dominant states,” or “cultural incompatibility of local communities.”

Second, after completing the initial coding for all articles, we proceeded to the axial coding stage. Here, we repeatedly compared, categorized, and consolidated the hundreds of initial codes generated in the previous step to identify their underlying connections. Similar or related codes were grouped into more abstract conceptual categories. For instance, multiple initial codes such as “lack of monitoring,” “no sanction clauses,” and “weak enforcement” might be collectively categorized under the theme “hollowing-out of implementation and monitoring mechanisms.”

Finally, through a higher level of abstraction and integration of these categories, we formulated the core analytical dimensions of this study, which constitute the “failure typology” to be elaborated in Chapter three. This process ensured that the final research findings are firmly grounded in the empirical evidence of the literature, rather than on the subjective preconceptions of the researchers. To ensure the reliability and validity of the coding process, a rigorous collaborative approach was adopted. Initially, two researchers independently conducted open coding on a subset of 20 articles to develop a preliminary codebook. They then met to compare codes, discuss discrepancies in interpretation, and refine the definitions of each code until a stable coding framework was established. Following this, the two researchers independently coded the remaining articles, holding regular meetings throughout the process to discuss emergent themes and resolve any ambiguities. This iterative process of independent coding followed by consensus-building discussions ensured that the final thematic analysis was both robust and deeply grounded in the source data.

3 Findings: a typology of cross-border governance failure

This chapter presents the core empirical findings of the study. Through a systematic thematic analysis and coding of the 138 articles on cases of cross-border governance failure, we have identified and synthesized a series of key mechanisms that lead to the breakdown of cooperation. These mechanisms do not exist in isolation but can be integrated into three interconnected core dimensions: failures of institutional design, failures of political dynamics, and failures of socio-economic context. This chapter will build a typology for explaining cross-border governance failure around these three dimensions, providing an in-depth explanation and systematic analysis of each failure mechanism based on the empirical evidence from the reviewed literature.

In our final sample analysis, we observed a notable prevalence of studies focused on water governance and cases drawn from the European and Asian contexts. This distribution reflects geopolitical realities: transboundary water resources represent the most critical and conflict-prone shared assets, while Europe and Asia act as the most active laboratories for observing the challenges of cross-border governance.

3.1 Dimension one: failures of institutional design

Institutional design serves as the “architectural blueprint” for cross-border governance, and its quality directly determines the robustness and sustainability of cooperative efforts. The systematic review reveals that a significant number of governance failures stem from inherent flaws within the institutional design itself. These deficiencies render governance arrangements vulnerable in the face of real-world challenges, ultimately leading to the stagnation or collapse of cooperation. This section focuses on three typical mechanisms of institutional design failure: the “hollowing-out” of implementation and monitoring, the “fragmentation” of authority and responsibility, and institutional “rigidity.”

3.1.1 Hollowing-out of enforcement and monitoring

A recurring theme of failure in the analyzed literature is that many cross-border cooperation agreements and governance mechanisms, though ambitious on paper, become “paper tigers” in practice due to a lack of robust enforcement and monitoring provisions (Chitakira et al., 2022; Renner et al., 2018). This “hollowing-out” phenomenon typically manifests as the failure of a governance arrangement to establish binding dispute resolution procedures, effective sanctions for non-compliance, and an independent third-party monitoring system. This problem is particularly prominent in the field of transboundary water resource management. Numerous studies point out that while many international river treaties establish principles for water allocation, they fail to specify concrete response measures or enforcement powers in the event of a breach by one party. Consequently, these agreements often become ineffective when faced with pressures such as drought or unilateral over-extraction of water (Al-Faraj, 2017; Do O, 2012; Sorg et al., 2014). For example, an analysis of the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses reveals that its commitments have fallen short precisely because of a lack of specific compliance mechanisms (Vasani, 2023). This dilemma is also evident in the legal regulation of multinational corporations, where many international soft-law norms intended to constrain corporate behavior have had minimal effect due to their lack of enforceability (Sachs, 2008). Similarly, in the case of environmental governance on the U.S.-Mexico border, the absence of enforcement and compliance mechanisms within its established cooperative commission has directly led to the continued deterioration of environmental conditions (Munoz-Melendez and Martinez-Pellegrini, 2022). This mechanism’s failure is not confined to the environmental sector; in the European Union, a lack of effective sanctions against non-compliant member states is also considered a key reason for the failure to achieve policy goals in cross-border financial regulation (Knaack, 2015), transport policy (Vickerman, 2015), and anti-corruption efforts (Ochnio, 2021). The literature further reveals that this lack of enforceability not only undermines the direct effectiveness of cooperative agreements but, more critically, also erodes the long-term trust among participating actors, making future cooperation even more difficult.

3.1.2 Fragmentation of roles and responsibilities

Another typical institutional flaw in cross-border governance is the “fragmentation” of the governance architecture. This fragmentation stems from unclear divisions of authority and responsibility, conflicting objectives, or coordination failures among multiple actors, ultimately leading to governance gridlock or policy vacuums (Marks and Miller, 2022). In complex governance systems, actors at different levels (international, national, local), from different sectors (environmental, economic, security), and of different types (government, NGOs, private sector) often operate independently according to their own mandates and goals, lacking an integrative institutional framework to coordinate their actions (Keskinen and Varis, 2012). In transnational migration governance, for example, the overlapping and conflicting functions of multiple state agencies (such as border control, internal affairs, and labor departments) frequently result in slow and mutually obstructive responses to migration issues, thereby triggering governance crises (Uzomah, 2024). In the realm of transboundary fisheries management, fragmented decision-making processes have also been identified as a significant cause of resource over-exploitation and ecosystem degradation (Abolhassani, 2023). Furthermore, the problem of institutional fragmentation is prominent in transboundary water resource management in Africa, where a lack of effective coordination among different regional organizations and national agencies hinders the achievement of integrated basin management objectives (Mwima, 2014). Recent research further confirms that during the COVID-19 global public health crisis, the uncoordinated, unilateral actions of EU member states regarding border closures, health data sharing, and vaccine procurement were a critical manifestation of the fragmentation of their internal coordination mechanisms (Novotny and Bohm, 2022). This lack of clearly defined authority and responsibility not only reduces governance efficiency but can also create institutional loopholes that allow certain actors to shirk responsibility and shift costs, ultimately undermining the foundations of the entire cooperative system.

3.1.3 Lack of institutional adaptability

The third form of institutional design failure manifests as the “rigidity” of governance mechanisms. This occurs when an institution, once established, lacks the flexibility to adjust and evolve in response to changes in the external environment, ultimately becoming obsolete as it cannot adapt to new challenges (see Table 2; VanNijnatten, 2020). Many cross-border governance arrangements are initially designed as static, “blueprint” solutions targeting specific problems under particular historical conditions (Huffman, 2009). However, these rigid institutions expose their vulnerability when confronted with technological shocks, political shifts, new scientific understanding, or sudden ecological crises. In the field of biodiversity conservation, for instance, some governance mechanisms have become trapped in a state of path-dependent “institutional lock-in,” rendering them unable to respond effectively to new threats posed by climate change (McClain et al., 2016). A particularly prominent example is the data transfer framework between the European Union and the United States. The successive invalidation of the “safe harbor” and “privacy shield” agreements was fundamentally rooted in their overly rigid design. They were unable to adapt and respond to the dynamic judicial reviews of data protection standards by the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Schrems line of cases, ultimately resulting in a major failure of cross-border data governance (McLaughlin, 2021). Together, these cases reveal that a successful cross-border governance institution requires not only present-day effectiveness but also a future-oriented, dynamic capacity for learning and adaptation.

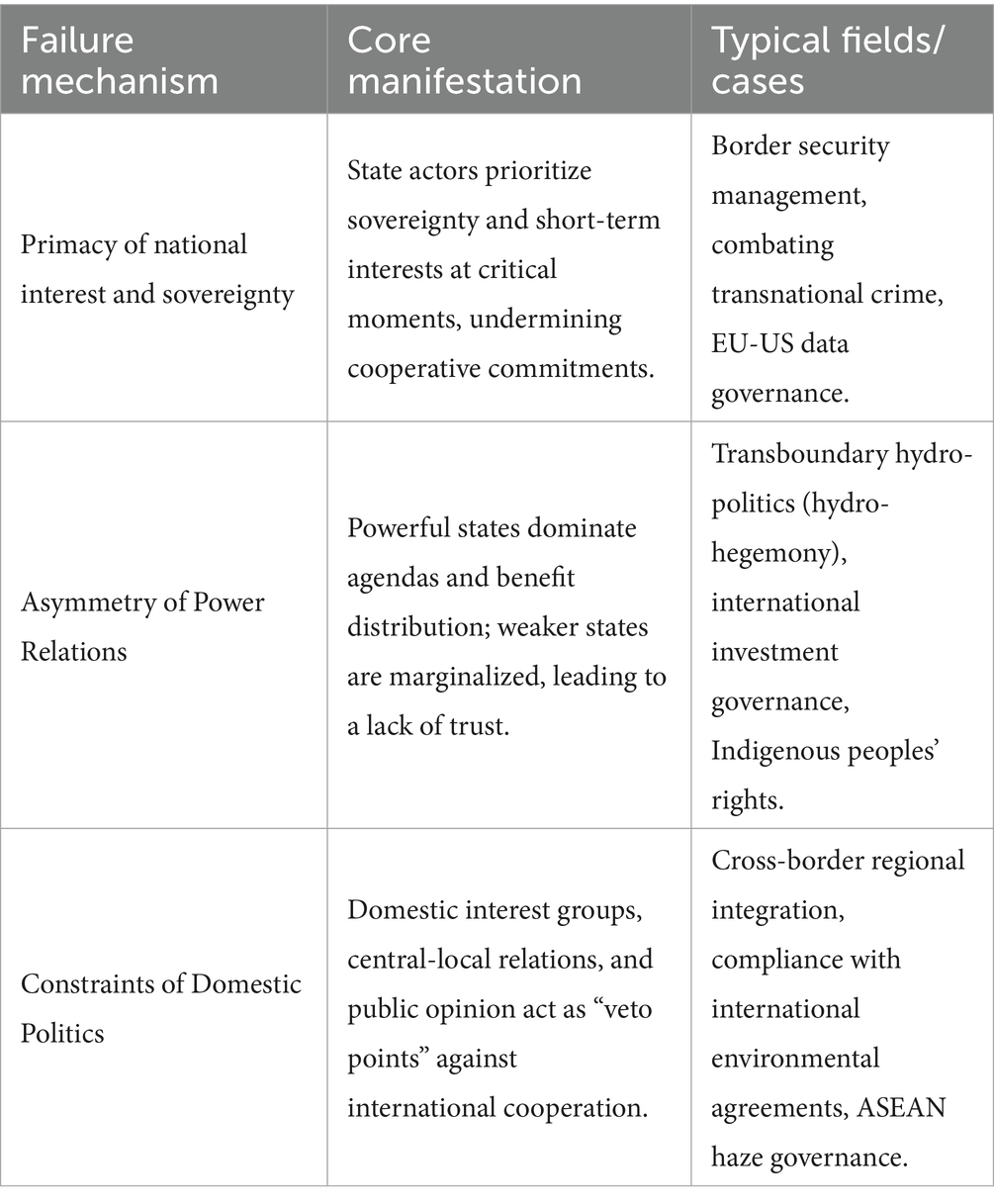

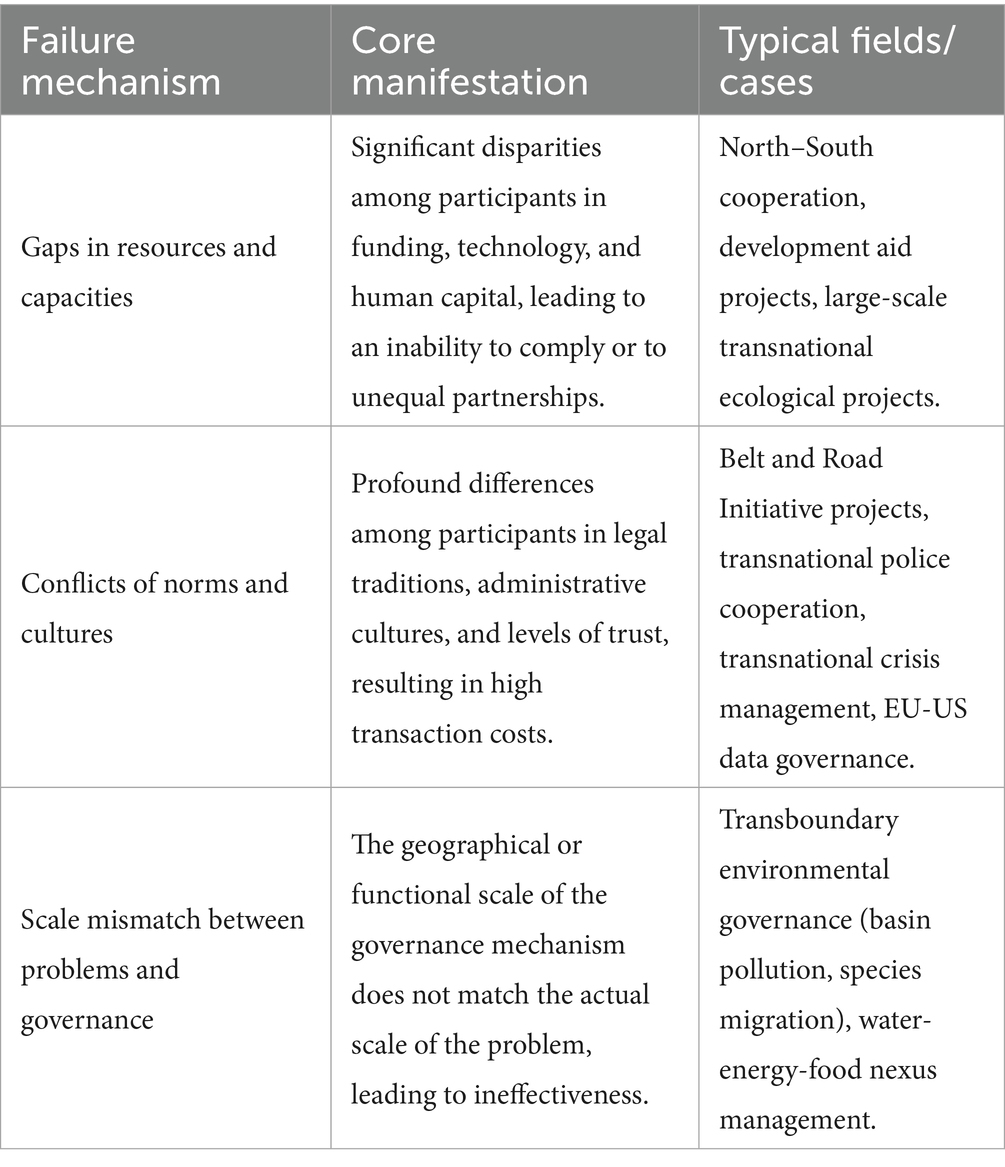

3.2 Dimension two: failures of political dynamics

If institutional design is the “skeleton” of cross-border governance, then political dynamics are the “blood” that drives or hinders its operation. The analysis reveals that even when an institutional design is formally perfect, the political realities rooted in interstate interactions are often the deeper cause of a cooperation’s ultimate failure. This section focuses on three key mechanisms of political dynamics failure: the “primacy” of national interest and sovereignty, the “asymmetry” of power relations, and the “constraints” of domestic politics.

3.2.1 Primacy of national interest and sovereignty

The essence of cross-border cooperation requires participants to cede a degree of autonomy in exchange for mutual benefits. However, when faced with critical decisions, the insistence of state actors on their own sovereignty and short-term interests constitutes the most direct challenge to cooperation (Behrens et al., 2008). Numerous cases from the systematic review demonstrate that when the commitments of cross-border cooperation conflict with national security, economic interests, or core political agendas, the latter are almost always given precedence. The border management practices between Israel and Jordan serve as a prime example; despite strong local aspirations for economic and social cooperation, Israel’s exclusionary securitization policies, grounded in national security considerations, ultimately stifled these cooperative initiatives (Arieli, 2012). In the fight against transnational organized crime, although nations face a common threat, political considerations involving sensitive issues like intelligence sharing and judicial sovereignty often override the practical need for law enforcement cooperation, leading to the failure of joint operations (Kurda, 2024). Similarly, efforts to advance asset recovery policies within the EU are frequently obstructed by member states’ reluctance to relinquish their domestic judicial autonomy (Ochnio, 2021). The most striking recent case is the EU-US cross-border data governance crisis sparked by the Schrems II ruling. The Court of Justice of the European Union ultimately invalidated the “Privacy Shield” agreement on the core grounds that U. S. national security surveillance laws failed to provide “essentially equivalent” protection for the data of EU citizens outside its sovereign territory. This clearly reveals the fragility of cooperative frameworks when the legal systems of two different sovereignties fundamentally clash (McLaughlin, 2021).

3.2.2 Asymmetry of power relations

The field of cross-border governance is not a vacuum composed of equal partners but is deeply embedded within imbalanced power structures (Lee and Paik, 2020). The literature analysis shows that asymmetries of power among participants—in military, economic, technological, or geopolitical terms—constitute another core mechanism of governance failure. This asymmetry often allows powerful states to dominate agenda-setting, rule-making, and the distribution of benefits, while weaker states are marginalized, their concerns left unaddressed (Lazniewska et al., 2023). In the domain of transboundary water resources, the theory of “hydro-hegemony” precisely describes this phenomenon: upstream or more powerful states leverage their advantageous position to control the flow and allocation of water, placing downstream or weaker states at a severe disadvantage in negotiations. This ultimately leads to the breakdown of cooperation or the establishment of highly inequitable agreements (Sakal, 2022; Sahu and Mohan, 2022). Turkey’s water policies in the South Caucasus (Sakal, 2022), as well as water disputes in the Ganges (Hanasz, 2017) and the Yarlung Zangbo-Brahmaputra river basins (Baruah et al., 2023), are all classic examples of power asymmetry eroding the foundations of cooperation. The impact of power asymmetry extends far beyond hydro-politics; in international environmental liability negotiations, conflicts of interest between developed and developing nations have also led to the failure of many agreements (Sachs, 2008). Furthermore, in the governance of North American border waters, power structures forged by colonial history have been criticized for failing to adequately represent the interests of marginalized groups, such as Indigenous peoples, and for continuing to produce negative outcomes (Strube and Thomas, 2021). Such power imbalances not only create substantive injustice but, more importantly, they destroy the minimal trust required for cooperation. This causes weaker parties, fearing exploitation or harm to their interests, to refuse participation or to comply only passively, ultimately leading to governance failure (Loodin et al., 2023).

3.2.3 Constraints of domestic politics

While states are the signatories of cross-border cooperation agreements, the costs and impacts of compliance are often borne by specific domestic regions, industries, or social groups. Consequently, domestic political agendas, the maneuvering of interest groups, and public opposition frequently become powerful “veto points” that obstruct or subvert international cooperation (see Table 3; Varkkey, 2014). The systematic review finds that many failures in cross-border governance do not stem from direct interstate conflict but are rather the result of a “misfit” between international commitments and the domestic political landscape. For example, when promoting cross-border regional integration, local governments or border communities may resist the national-level cooperative agenda due to fears of economic shocks, cultural erosion, or increased security risks (Miles, 2003). In environmental governance, interest groups from high-polluting industries often use political lobbying to prevent their governments from fulfilling commitments made in international climate or pollution control agreements (Marks and Miller, 2022). The case of cross-border cooperation between Poland and the Czech Republic vividly illustrates the complexity of domestic rules; differing administrative regulations in the two countries created asymmetries in cooperative projects, thereby weakening their effectiveness (Furmankiewicz and Trnkova, 2024). This dynamic is further exemplified by the recent dispute over the Turow Mine, where cross-border governance mechanisms failed to resolve environmental conflicts when confronted with strong domestic energy interests and local employment concerns (Böhm et al., 2025). Furthermore, the pressures of public opinion and electoral politics cannot be ignored. In some democracies, opposition parties or nationalist sentiment can politicize cross-border issues, portraying them as a “sell-out” of national sovereignty. This can compel the ruling government to adopt a more conservative or even regressive stance on cooperation, ultimately causing it to stagnate or fail (Chernolutskaia, 2022).

3.3 Dimension three: failures of socio-economic context

Beyond institutional design and political dynamics, the success or failure of cross-border governance is also deeply embedded in its specific socioeconomic context. These contextual factors constitute the “soil” for cooperation; if this soil is poor or unsuitable, the seeds of cooperation will struggle to take root and grow. The analysis finds that even with well-crafted institutions and sufficient political will, certain structural socioeconomic barriers can fundamentally undermine cooperative efforts. This section will explore three key mechanisms of contextual failure: the “gaps” in resources and capacities, the “conflicts” of norms and culture, and the “scale mismatch” between problems and governance.

3.3.1 Gaps in resources and capacities

Cross-border cooperation, particularly that which involves the implementation of concrete projects, requires participants to invest corresponding financial, technological, data, and human capital resources. However, in many governance practices, especially in contexts of South–South or North–South cooperation, vast disparities in these key resources and capacities among participants form a fundamental obstacle to the sustainability of cooperation (Sachs, 2008). The literature reveals that such “gaps” can lead to a series of cascading negative effects. First, the party with weaker capacity may be unable to effectively fulfill the obligations it committed to in an agreement. For example, a lack of necessary technical equipment and professional personnel for environmental monitoring, or insufficient financial resources to build supporting infrastructure, can make cooperation difficult from the very beginning (Mwima, 2014; Sambrook et al., 2014). Second, resource and capacity gaps can entrench unequal partnerships. In many development aid projects, the dominant-recipient dynamic between donors and beneficiaries in agenda-setting, project management, and evaluation standards often undermines the recipient’s sense of ownership and long-term capacity building. Once external aid is withdrawn, the cooperation becomes unsustainable (Hanasz, 2017). A recent analysis of transboundary protected areas in Africa confirms this, showing that despite grand international commitments, significant capacity gaps and inadequate funding among the participating countries have caused cooperation to exist only on paper, with project progress falling far short of expectations (Chitakira et al., 2022). This structural inequality ultimately makes the goals of cross-border cooperation unattainable and may even exacerbate development imbalances between regions.

3.3.2 Conflicts of norms and cultures

Effective cooperation depends not only on formal institutional arrangements but is also rooted in the shared norms, values, and trust among participants. When there are profound differences between parties in legal traditions, administrative cultures, business practices, or levels of social trust, significant transaction costs and barriers to cooperation can arise (Kratke, 1998). The literature analysis shows that this conflict of norms and cultures is a more subtle yet far-reaching mechanism of governance failure. For example, an analysis of cross-border economic cooperation between the Soviet Union and China reveals that the effectiveness of their collaboration was greatly diminished due to differing bureaucratic objectives (the Soviets focused on ideology, while the Chinese focused on trade) and gaps in business experience and risk awareness (Savchenko and Chernolutskaia, 2022). In transnational police cooperation, differences in police cultures and legal procedures among countries also severely hinder effective collaboration (Kurda, 2024; Carbune and Chiriac, 2020). In transnational crisis management, differing organizational cultures and communication protocols among national emergency response agencies often make it difficult to establish a unified command for action and information sharing, leading to coordination failure (Trbojevic and Radovanovic, 2024). A deeper level of conflict stems from differences in legal culture. The long-standing dilemma in EU-US cross-border data governance is rooted not only in conflicting legal statutes but also in a fundamental divergence in the value prioritization between the right to privacy (considered a fundamental human right in Europe) and national security (which holds a privileged position in the United States; McLaughlin, 2021). These cases demonstrate that ignoring deep-seated normative and cultural differences can cause even meticulously designed cooperative mechanisms to ultimately fail due to a lack of a shared foundation of understanding and trust.

3.3.3 Scale mismatch between problems and governance

The final contextual failure mechanism stems from a “scale mismatch,” where the established governance mechanism does not align with the actual scale of the problem it is meant to solve, whether geographically, functionally, or administratively (see Table 4; Hirsch, 2020). Ecosystems and socioeconomic problems have their own intrinsic operational scales, whereas governance arrangements are often constrained by pre-existing administrative boundaries and political jurisdictions. When a mismatch occurs between these two, governance failure is almost inevitable (Abolhassani, 2023). Transboundary environmental governance is a classic domain for this issue. For example, a local pollution control agreement for a specific river segment cannot solve the problem of agricultural non-point source pollution originating from the entire upstream basin. Similarly, a biodiversity conservation area confined to the territory of a single country can hardly protect species that require transnational migration (Li et al., 2024). This geographical scale mismatch leads to governance actions that “treat the symptom, not the cause,” failing to address the root of the problem. Furthermore, a functional scale mismatch can be equally critical. For instance, attempting to solve complex transboundary water issues through cooperation within a single sector (such as water management) while ignoring its strong interconnections with other sectors like energy, agriculture, and ecology (the so-called “water-energy-food nexus”) results in a “functional silo” approach to governance that is bound to fail (Wineland et al., 2022). The essence of scale mismatch is the dilemma of “using the wrong tool to solve a problem at the wrong scale,” which highlights the critical importance of a systemic, cross-scalar understanding of the problem itself when designing cross-border governance mechanisms.

4 Discussion

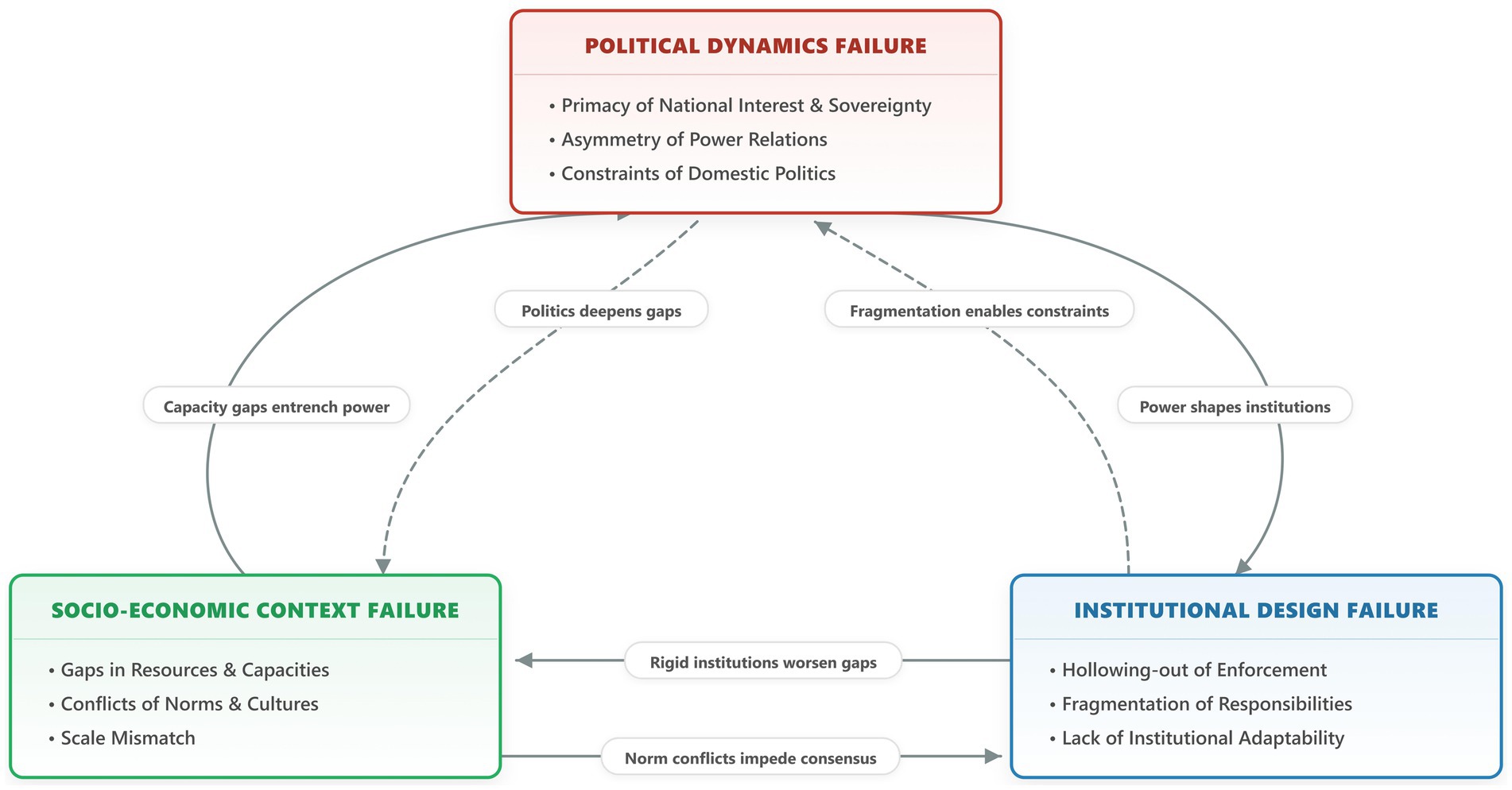

4.1 An integrative framework: the interplay of failure mechanisms

The three dimensions and their internal mechanisms presented in Chapter three are not a mutually exclusive “checklist of problems” but rather collectively form an interwoven and dynamically evolving “system of failure.” The failure of cross-border governance is rarely an isolated event triggered by a single factor; instead, it is a systemic process in which multiple mechanisms transmit effects across dimensions, mutually reinforce one another, and create vicious feedback loops. To more intuitively illustrate these complex interlinkages, we propose an integrative analytical framework of cross-border governance failure (see Figure 2). The framework is designed to clarify how a failure in any single dimension can act as a “trigger” for a chain reaction, amplifying the negative effects throughout the entire governance system via a fully interconnected network. This section, guided by the framework, will systematically elaborate on six core causal pathways that exist among the three dimensions.

4.1.1 The bidirectional shaping of political dynamics and institutional design

First, a profound, bidirectional relationship exists between politics and institutions. On the one hand, political power shapes the form of institutions. Numerous cases from the systematic review show that the “asymmetry” of power relations (a political dynamic) is an initial condition that shapes institutional arrangements (Zeitoun and Mirumachi, 2008). Powerful actors often leverage their advantageous negotiating position to dominate the institutional design process, creating governance frameworks that benefit themselves but lack universal binding force. This directly leads to the “hollowing-out” of enforcement and monitoring mechanisms (an institutional design failure), as powerful parties have neither the will nor the incentive to establish a strong oversight system that could effectively constrain their own behavior (Gerlak and Schmeier, 2014; Redelinghuys and Pelser, 2013). In the field of transboundary water resources, for example, “hydro-hegemonic” states use their power advantage to shape cooperative agreements that are strong on principle but weak on enforcement, thereby preserving their own freedom of action (Sakal, 2022).

On the other hand, institutional flaws can, in turn, create opportunities for destructive political behavior. An institutional architecture characterized by the “fragmentation” of authority and responsibility (an institutional design failure) can create numerous “veto points” for the “constraints” of domestic politics (a political dynamic; Bovaird, 2004). When the roles and responsibilities of multiple departments or levels of government are unclear, domestic interest groups or local governments opposed to cooperation can exploit this institutional ambiguity to selectively implement or even overtly resist international commitments. This allows the cross-border cooperation to be effectively “hollowed out” at the domestic level (Marks and Miller, 2022). In this context, institutional fragmentation is no longer merely a question of efficiency; it evolves directly into a political problem, providing legitimate institutional space for domestic “anti-cooperation” forces.

4.1.2 The mutual entrenchment of political dynamics and socioeconomic context

Second, political dynamics and the socioeconomic context can form a vicious cycle of mutual entrenchment. On the one hand, socioeconomic disparities are a root cause of political inequality. The “gaps” in resources and capacities (a socioeconomic context) are not just technical barriers to cooperation but are also structural factors that entrench power imbalances. When significant disparities in funding, technology, and human capital exist between participants, weaker parties, even if they join the governance process, often lack the necessary information and negotiating capacity to make their voices heard effectively (Sachs, 2008). This capacity gap further reinforces the “asymmetry” of power relations (a political dynamic), leading to the thorough marginalization of weaker parties in institutional negotiations and the exclusion of their core concerns from the final institutional design (Lee and Paik, 2020).

On the other hand, political decisions can, in turn, exacerbate socioeconomic divides. Unilateral actions taken by state actors based on the “primacy” of national sovereignty (a political dynamic) often directly worsen the socioeconomic conditions of a specific region. For example, exclusionary border management policies based on national security concerns can stifle spontaneous economic and social cooperation among borderland populations, thereby deepening their economic marginalization (a socioeconomic context; Arieli, 2012). This “de-cooperation” driven by political decisions adds further strain to an already fragile socioeconomic foundation.

4.1.3 The disjuncture between institutional design and socioeconomic context

Finally, a bidirectional relationship of disjuncture and mutual erosion also exists between institutional design and the socioeconomic context. On the one hand, socioeconomic conflicts hinder the formation of institutional consensus. When profound “conflicts” of norms and cultures (a socioeconomic context) exist between participants, they may struggle to even agree on the basic goals, principles, and procedures of cooperation. For instance, the long-standing dilemma of EU-US cross-border data governance is rooted in a fundamental divergence in the value prioritization between the right to privacy and national security. This deep-seated difference in legal culture renders any institutional arrangement fragile and makes a stable consensus difficult to form (McLaughlin, 2021).

On the other hand, rigid institutions can worsen socioeconomic predicaments. An institutional arrangement that lacks adaptability (an institutional design failure), when faced with new technological shocks or socioeconomic changes, not only fails to solve problems but may itself become a source of their exacerbation. For example, a rigid transboundary resource management institution that fails to adjust to new scientific evidence or the impacts of climate change can lead to severe inequities in resource allocation, thereby intensifying socioeconomic conflicts between regions (a socioeconomic context; Af Rosenschold et al., 2014). In such cases, the institution itself becomes a “stumbling block” to the healthy development of the socioeconomic system.

In summary, the failure of cross-border governance is a complex, systemic emergent phenomenon. As illustrated in Figure 2, the complete, bidirectional causal chains among the three dimensions together weave an inescapable “web of failure.” Therefore, the diagnosis of and response to failure must transcend any single mechanism and adopt a more holistic and systemic perspective.

4.2 Theoretical implications: what failures teach us about governance theories

By systematically analyzing cases of failure, this study not only constructs an explanatory typology but, more importantly, offers a critical perspective from which to re-examine the mainstream theories that dominate contemporary governance research. We find that many widely accepted governance theories, such as network governance, multi-level governance, and new institutionalism, have made outstanding contributions to explaining why cooperation occurs and how it functions. However, their theoretical frameworks often have an embedded “cooperation bias.” This bias tends to treat cooperation as a default and desirable goal, focusing primarily on the conditions and mechanisms that foster it, while relatively neglecting the “dark side”—the forces that systemically and structurally lead to the failure of cooperation.

Network governance theory posits the network as an effective mode of coordination based on trust and reciprocity, distinct from markets and hierarchies (Jones et al., 1997). However, the findings of this study challenge this idealized vision of the network. The mechanisms revealed in Chapter Three—such as the “asymmetry of power relations,” the “primacy of national interest,” and “conflicts of norms and cultures”—demonstrate that a governance network is far from a neutral platform for collaboration. Instead, it is often an arena for power struggles and conflicts of interest. A successful “network” may not arise from the spontaneous collaborative will of its actors but requires preconditions such as a benign power structure, a shared normative foundation, and sufficient complementary resources. When these preconditions are absent (a common situation in cross-border contexts), a network not only fails to promote cooperation but may become a tool for powerful states to control weaker ones, or for the core to control the periphery, thereby exacerbating rather than resolving governance dilemmas. Therefore, the study of failure urges network governance theory to more systematically integrate “anti-network” factors like power, conflict, and inequality into its core analytical framework.

Similarly, the schools of institutional analysis represented by multi-level governance and new institutionalism provide sophisticated analytical tools for understanding the formation, evolution, and impact of institutions in the cross-border field (Hooghe and Marks, 2003; North, 1990). These theories emphasize how formal and informal “rules of the game” shape actors’ expectations and reduce transaction costs. However, the abundant evidence of institutional “hollowing-out,” “fragmentation,” and “rigidity” in this study suggests that institutions themselves can be strategically designed as “tools of failure.” Powerful actors may intentionally create institutions with unclear responsibilities and weak oversight to evade their own accountability; rigid institutions can become a “protective shield” for vested interests resisting change. In such cases, the institution is no longer the solution to the problem but becomes part of the problem itself. This challenges a latent functionalist tendency in institutionalist theory, which often assumes that institutions exist primarily to achieve collective goals. The study of failure, in contrast, reveals the “dysfunctional” aspect of institutions. It argues that studying “why institutions fail” is as important as studying “why they work,” and it prompts us to shift our analytical focus from “how institutions enable cooperation” to “what political and social forces cause the systemic failure of institutions.”

In conclusion, this study does not aim to reject mainstream governance theories outright. Instead, by systematically presenting the side of governance failure, it seeks to offer a critical supplement and corrective. The study of failure is not merely an empirical addition to existing theories; it is a necessary path for developing and deepening these theories. It reminds us that any theory of “good governance” must be built upon a profound understanding of “bad governance.”

4.3 Practical implications: towards resilient governance

Ultimately, the purpose of learning from a systematic analysis of failure is to better achieve success. The findings of this study offer important practical implications for policymakers and practitioners seeking to build more resilient cross-border governance mechanisms that can better withstand the risks of failure. Resilient governance does not refer to a perfect, failure-proof system, but rather to a capacity to anticipate risks, adapt to change, and even learn and recover from failures (Folke et al., 2016). Based on the findings of this research, we propose the following three core practical principles.

First, governance design should shift from pursuing the “optimal” to embracing the “adaptive.” As revealed in Chapter three, “institutional rigidity” is a key mechanism leading to failure. Traditional governance models tend to seek static, one-off “blueprint” solutions, but these are extremely vulnerable in uncertain cross-border environments. Therefore, practitioners should embed the concept of adaptive management into institutional design from the very outset (Gunderson, 1999). Specific measures include setting clauses for regular review and revision within cooperative agreements;for instance, in hydropolitics, this implies moving away from fixed quotas to dynamic allocation models based on real-time climate data; establishing independent, evidence-based joint monitoring and evaluation committees empowered to recommend adjustments to decision-making bodies; and, where feasible, adopting an “experimentalist governance” approach by using small-scale pilot projects to test different cooperation models and iterating based on feedback (Sabel and Zeitlin, 2012).

Second, the governance process must directly confront and proactively manage asymmetries of power and capacity. This study’s findings repeatedly confirm that the “asymmetry of power relations” and “gaps in capacities” are structural forces that erode the foundations of cooperation. Avoiding these issues only gives rise to cooperative frameworks that are superficially equitable but practically unsustainable. Therefore, building resilient governance requires making “empowerment” a core part of the agenda. For participants with weaker capacities, cooperative agreements should explicitly include long-term, targeted capacity-building plans covering technical training, financial support, and institutional development (Mwima, 2014; Sambrook et al., 2014). At the same time, the active introduction of neutral third-party mediation and arbitration mechanisms can effectively buffer the excessive influence of powerful states in negotiations and create a more level playing field for weaker parties (Trondalen, 2004). Specifically in transborder security cooperation, this could involve establishing joint command centers with shared data access to prevent unilateral dominance. Furthermore, designing fairer and more transparent cost–benefit sharing mechanisms to ensure that the outcomes of cooperation benefit all participants is the fundamental guarantee for sustaining long-term relationships and building mutual trust.

Finally, governance practices must extend beyond formal agreements to invest heavily in the cultivation of trust and shared norms. The large number of failure cases, particularly those stemming from “conflicts of norms and cultures” and the “constraints of domestic politics,” demonstrate that a formal agreement alone is far from sufficient to support robust cooperation. Trust, shared understanding, and cross-cultural communication skills are the indispensable “social capital” of cross-border cooperation (Coleman, 1988). To this end, policymakers should invest more resources in “Track II” diplomacy and cross-societal dialogues. For example, before official negotiations begin, unofficial workshops, joint research projects, and expert group dialogues can effectively bridge cognitive divides and create a positive atmosphere for official talks. Encouraging regular exchange mechanisms among communities, businesses, and non-governmental organizations in border regions, as well as implementing personnel exchanges and joint training programs between government agencies of the relevant countries, can all help to subtly cultivate a shared administrative culture and professional norms, thereby providing a solid social foundation for the formal governance framework.

5 Conclusion and future research agenda

5.1 Review of core findings

This paper aimed to systematically answer the core question: “Why does cross-border cooperation fail?” Through a systematic review and thematic analysis of 138 academic articles on cases of cross-border governance failure, this study has made two primary contributions.

First, this study constructed an integrative typology that explains the failure of cross-border governance. The research found that numerous governance failures do not stem from single, incidental causes but can be categorized into three interconnected core dimensions: failures of institutional design (manifested in hollowing-out of enforcement and monitoring, fragmentation of roles and responsibilities, and lack of institutional adaptability); failures of political dynamics (manifested in primacy of national interest and sovereignty, asymmetry of power relations, and constraints of domestic politics); and failures of socio-economic context (manifested in gaps in resources and capacities, conflicts of norms and cultures, and scale mismatch between problems and governance). This typology is the first to systematically and trans-domainly present the key mechanisms leading to the failure of cooperation, providing a clear analytical map for understanding the “fractures” in governance.

Second, this study moved beyond a static list of failure mechanisms to propose an integrative analytical framework that reveals their internal linkages. The research emphasizes the complex interplay and cascading effects among the failure mechanisms of different dimensions; for example, political power asymmetry is often the root cause of the hollowing-out of institutional design. Building on this, the study engaged in a critical dialogue with mainstream governance theories such as network governance and new institutionalism, arguing for the existence of a “cooperation bias” within them and positing that the study of failure is a crucial path for correcting and advancing existing theory.

5.2 Research limitations

Although this study strove for rigor, it is subject to several inherent limitations. First, the literature search relied primarily on the WoS Core Collection and was focused on English-language publications. This may have introduced a “language bias,” potentially excluding important research findings published in other languages. Second, due to the nature of the systematic review method, our analysis was based mainly on published academic literature. This may have led to the omission of rich cases and insights contained within “grey literature,” such as government reports and non-governmental organization assessments, which constitutes a form of “publication bias.” Third, the unit of analysis in this study was the “failure mechanism.” While we sought to synthesize evidence from multiple cases for each mechanism, the scope of a review piece precluded an in-depth, process-tracing analysis of any single, specific case of failure. These limitations leave important space for future research to explore.

Further methodological limitations should also be acknowledged. First, this review did not employ a standardized tool (e.g., CASP or JBI checklists) to formally assess the risk of bias within each of the 138 included studies. This means our findings are based on all studies that met the eligibility criteria, without weighting them according to their internal methodological rigor. Second, we did not conduct a formal certainty of evidence assessment (e.g., using GRADE-CERQual) for our synthesized findings. Therefore, the failure typology presented in this paper should be interpreted as a comprehensive “phenomenon map” of the reasons for failure reported in the existing academic literature, rather than a “strength rating” of their causal impact. Future research could build upon our framework by applying these formal assessment tools to test the robustness and generalizability of the failure mechanisms we have identified.

5.3 Future research agenda

Based on this study’s findings and limitations, we contend that research on cross-border governance failure is still in its early stages. Future scholarly inquiry could be deepened in the following directions:

First, moving from “why failures occur” to “how to learn from failure.” This study has focused primarily on diagnosing failure. However, a more constructive question is whether and how actors can learn from failed experiences and make adaptive adjustments (Birkland, 2019). Future research could employ process-tracing or comparative case study methods to conduct deep dives into cases that experienced failure but ultimately achieved institutional repair or the revival of cooperation. Such work could reveal the learning mechanisms and organizational routines that underpin “resilient governance.”

Second, deepening the causal analysis of specific failure mechanisms. This study has constructed a macro-level typology. However, the micro-processes through which each failure mechanism (such as the “asymmetry of power relations” or “scale mismatch”) is triggered and evolves in a specific context to ultimately cause the collapse of cooperation still require more in-depth exploration. Future research could focus on a particular mechanism identified in this study and conduct more targeted comparative case analyses to establish more fine-grained causal chains.

Third, systematically incorporating the role of non-state actors into the analytical framework. The analysis in this study has focused primarily on state or intergovernmental actors. In contemporary global governance, however, the role of non-state actors—such as multinational corporations, large technology platforms, and international non-governmental organizations—is increasingly prominent. They can be facilitators of cooperation, but they can also be producers of governance failure. For example, the control over cross-border data flows by tech giants poses a significant challenge to traditional state-centric data governance frameworks (Verbeke and Hutzschenreuter, 2021). Future research needs to systematically investigate the roles and impacts of these actors in governance failure. Beyond the tech sector, research should also explore how civil society organizations and NGOs influence failure—either by their exclusion from governance design, which leads to a legitimacy deficit, or by their uncoordinated actions that may exacerbate normative conflicts.

Fourth, prospectively assessing the risks of governance failure in emerging domains. Most of the cases in this study were drawn from traditional domains like the environment, the economy, and security. However, with the rapid advancement of technology, new cross-border governance challenges are constantly emerging. In new fields such as artificial intelligence, gene editing, outer space exploration, and even global carbon markets, the initial signs of potential “conflicts of norms and cultures,” “scale mismatch,” and “capacity gaps” are already visible (Kalenzi, 2022). Future research should be more forward-looking, identifying and warning of the potential risks of cross-border governance failure in these emerging domains to provide theoretical support for building more anticipatory and adaptive governance mechanisms.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed for this study can be found in the FigShare at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30073126. The FigShare link for the PRISMA checklist of this article is http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30157246.

Author contributions

JC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. YY: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation. YP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. YX: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Methodology. HH: Formal analysis, Validation, Project administration, Writing – original draft. HJ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. CW: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research is supported by Macao Polytechnic University, RP/FCHS-04/2022.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abolhassani, A. (2023). Scalar politics in transboundary fisheries management: the Western and Central Pacific fisheries commission as an eco-scalar fix for South Pacific albacore tuna management. Mar. Policy 152:105583. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105583

Af Rosenschold, J. M. R., Rozema, J. G., and Frye-Levine, L. A. (2014). Institutional inertia and climate change: a review of the new institutionalist literature. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 5, 639–648. doi: 10.1002/wcc.292

Al-Faraj, F. A. M. (2017). “Collective impact of upstream anthropogenic interventions and prolonged droughts on downstream basin’s development in arid and semi-arid areas: the Diyala Transboundary Basin” in Water resources in arid areas: The way forward, (Eds.) Osman, A, Anvar, K, Mingjie, C, Ali, A-M, Talal, A-H, and Ian, C. Cham: Springer. 31–41.

Arieli, T. (2012). Borders of peace in policy and practice: national and local perspectives of Israel-Jordan border management. Geopolitics 17, 658–680. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2011.638015

Baruah, T., Barua, A., and Vij, S. (2023). Hydropolitics intertwined with geopolitics in the Brahmaputra River basin. WIREs Water 10:1626. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1626

Behrens, V., Rauschmayer, F., and Wittmer, H. (2008). Managing international ‘problem’ species: why Pan-European cormorant management is so difficult. Environ. Conserv. 35, 55–63. doi: 10.1017/S037689290800444X

Birkland, T. A. (2019). An introduction to the policy process: Theories, concepts, and models of public policy making. 5th Edn. New York: Routledge.

Böhm, H., Boháč, A., Novotný, L., and Kurowska-Pysz, J. (2025). The impact of the dispute over the Turów mine on polish-Czech cross-border cooperation. GeoScape 19, 77–91. doi: 10.2478/geosc-2025-0006

Bovaird, T. (2004). Public–private partnerships: from contested concepts to prevalent practice. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 70, 199–215. doi: 10.1177/0020852304044250

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carbune, A., and Chiriac, R. (2020). Institutional obstacles in cross-border cooperation between Romania and Republic of Moldova. In European finance, business and regulation (EUFIRE 2020). pp. 111–119. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lorena-Popescul-Dumitrasciuc-2/publication/344781240_IMPLEMENTATION_OF_THE_GDPR_IN_THE_ROMANIAN_ENTREPRENEURIAL_BUSINESS/links/61879446d7d1af224bc0f226/IMPLEMENTATION-OF-THE-GDPR-IN-THE-ROMANIAN-ENTREPRENEURIAL-BUSINESS.pdf#page=111 (Accessed August 15, 2025).

Chernolutskaia, E. (2022). Cross-border cooperation vs territorial issue: Kuril Islands in the period of market transformations. Istoriia 13:01. doi: 10.18254/S207987840019952-6

Chitakira, M., Nhamo, L., Torquebiau, E., Magidi, J., Ferguson, W., Mpandeli, S., et al. (2022). Opportunities to improve eco-agriculture through transboundary governance in transfrontier conservation areas. Diversity 14:461. doi: 10.3390/d14060461

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 94, S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943

Do O, A. (2012). Drought planning and management in transboundary river basins: the case of the Iberian Guadiana. Water Policy 14, 784–799. doi: 10.2166/wp.2012.173

Folke, C., Biggs, R., Norström, A. V., Reyers, B., and Rockström, J. (2016). Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol. Soc. 21:341. doi: 10.5751/ES-08748-210341

Furmankiewicz, M., and Trnkova, G. (2024). Cross-border cooperation of polish and Czech area-based partnerships supported by rural development programmes: genuinely international or solely national projects? Moravian Geogr. Rep. 32, 137–150. doi: 10.2478/mgr-2024-0012

Gerlak, A. K., and Schmeier, S. (2014). Climate change and transboundary waters: a study of discourse in the Mekong River commission. J. Environ. Dev. 23, 358–386. doi: 10.1177/1070496514537276

Gunderson, L. H. (1999). Resilience, flexibility and adaptive management-antidotes for spurious certitude? Conserv. Ecol. 3:107. doi: 10.5751/ES-00089-030107

Hanasz, P. (2017). Muddy waters: international actors and transboundary water cooperation in the Ganges-Brahmaputra problemshed. Water Altern. 10, 459–474. Available online at: https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol10/v10issue2/365-a10-2-15/file

He, X., Li, G., and Du, H. (2024). Evolution of cooperation with early social influence for explaining collective action. Chaos 34:123140. doi: 10.1063/5.0242606,

Hirsch, P. (2020). Scaling the environmental commons: broadening our frame of reference for transboundary governance in Southeast Asia. Asia Pac. Viewp. 61, 190–202. doi: 10.1111/apv.12253

Hooghe, L., and Marks, G. (2003). Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 97, 233–243. doi: 10.1017/S0003055403000649

Howlett, M., and Ramesh, M. (2014). The two orders of governance failure: design mismatches and policy capacity issues in modern governance. Polic. Soc. 33, 317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2014.10.002

Huffman, J. L. (2009). Comprehensive river basin management: the limits of collaborative, stakeholder-based, water governance. Nat. Resour. J. 49, 117–149. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24889189

Jones, C., Hesterly, W. S., and Borgatti, S. P. (1997). A general theory of network governance: exchange conditions and social mechanisms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 22, 911–945. doi: 10.2307/259249

Kalenzi, C. (2022). Artificial intelligence and blockchain: how should emerging technologies be governed? Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 7:801549. doi: 10.3389/frma.2022.801549,

Keskinen, M., and Varis, O. (2012). Institutional cooperation at a basin level: for what, by whom? Lessons learned from Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Lake. Nat. Res. Forum 36, 50–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2012.01445.x

Knaack, P. (2015). Innovation and deadlock in global financial governance: transatlantic coordination failure in OTC derivatives regulation. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 22, 1217–1248. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2015.1099555

Kratke, S. (1998). Problems of cross-border regional integration: the case of the German-polish border area. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 5, 249–262. doi: 10.1177/096977649800500304

Kurda, C. (2024). The evolution of international policing against gypsies in Central Europe: 1870-1945. Cent. Eur. Hist. 57, 182–203. doi: 10.1017/S0008938923000511

Lazniewska, E., Bohac, A., and Kurowska-Pysz, J. (2023). Asymmetry as a factor weakening resilience and integration in the sustainable development of the polish-Czech borderland in the context of the dispute about the Turow mine. Probl. Ekorozw. 18, 139–151. doi: 10.35784/pe.2023.1.14

Lee, T., and Paik, W. (2020). Asymmetric barriers in atmospheric politics of transboundary air pollution: a case of particulate matter (PM) cooperation between China and South Korea. Int. Environ. Agreem.: Politics Law Econ. 20, 123–140. doi: 10.1007/s10784-019-09463-6

Li, H., Pandey, P., Li, Y., Wang, T., Singh, R., Peng, Y., et al. (2024). Transboundary cooperation in the Tumen River basin is the key to Amur leopard (Panthera pardus) population recovery in the Korean peninsula. Animals 14:59. doi: 10.3390/ani14010059

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100,

Loodin, N., Eckstein, G., Singh, V. P., and Sanchez, R. (2023). Assessment of the trust crisis between upstream and downstream states of the Helmand River basin (1973-2022): a half-century of optimism or cynicism? ACS ES&T Water 3, 1654–1668. doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.2c00428

Marks, D., and Miller, M. A. (2022). A transboundary political ecology of air pollution: slow violence on Thailand’s margins. Environ. Policy Gov. 32, 305–319. doi: 10.1002/eet.1976

McClain, S. N., Bruch, C., and Secchi, S. (2016). Adaptation in the Tisza: innovation and tribulation at the sub-basin level. Water Int. 41, 813–834. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2016.1214774

McLaughlin, E. W. (2021). Schrems’s slippery slope: strengthening governance mechanisms to rehabilitate EU-US cross-border data transfers after Schrems II. Fordham Law Rev. 90, 217–259. Available online at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol90/iss1/6

Medhekar, A., and Haq, F. (2022). “Cross-border cooperation for bilateral trade, travel, and tourism: a challenge for India and Pakistan” in Research anthology on measuring and achieving sustainable development goals. ed. Management Association, I (Hershey: IGI Global), 812–829.

Miles, J. (2003). “Cascades International Park: a case study” in Protected areas and the regional planning imperative in North America. eds. J. Nelson, J. Day, L. Sportza, C. Vazquez, and J. Loucky (Calgary: University of Calgary Press), 219–233.

Munoz-Melendez, G., and Martinez-Pellegrini, S. E. (2022). Environmental governance at an asymmetric border, the case of the US-Mexico border region. Sustainability 14:1712. doi: 10.3390/su14031712

Mwima, H. K. (2014). Environmental governance dimensions and perspectives for three transboundary African lakes. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 17, 97–102. doi: 10.1080/14634988.2014.873332

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Novotny, L., and Bohm, H. (2022). New re-bordering left them alone and neglected: Czech cross-border commuters in German-Czech borderland. Eur. Soc. 24, 333–353. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2022.2052144

Ochnio, A. H. (2021). The tangled path from identifying financial assets to cross-border confiscation: deficiencies in EU asset recovery policy. Europ. J. Crime Crim. Law Crim. Just. 29, 218–240. doi: 10.1163/15718174-BJA10024,

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71,

Redelinghuys, N., and Pelser, A. J. (2013). Challenges to cooperation on water utilisation in the southern Africa region. Water Policy 15, 554–569. doi: 10.2166/wp.2013.116

Renner, T., Meijerink, S., and van der Zaag, P. (2018). Progress beyond policy making? Assessing the performance of Dutch-German cross-border cooperation in Deltarhine. Water Int. 43, 996–1015. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2018.1526562

Sabel, C. F., and Zeitlin, J. (2012). Experimentalist governance. In The Oxford handbook of governance. pp. 169–183. Available online at: https://charlessabel.com/papers/Sabel%20and%20Zeitlin%20handbook%20chapter%20final%20(with%20abstract).pdf (Accessed August 15, 2025).

Sachs, N. (2008). Beyond the liability wall: strengthening tort remedies in international environmental law. UCLA Law Rev. 55, 837–904. Available online at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1494&context=law-faculty-publications

Sahu, A. K., and Mohan, S. (2022). From securitization to security complex: climate change, water security and the India-China relations. Int. Politics 59, 320–345. doi: 10.1057/s41311-021-00313-4

Sakal, H. B. (2022). The risks of hydro-hegemony: Turkey’s environmental policies and shared water resources in the South Caucasus. Caucas. Surv. 10, 294–323. doi: 10.30965/23761202-20220016

Sambrook, K., Holt, R. H. F., Sharp, R., Griffith, K., Roche, R. C., Newstead, R. G., et al. (2014). Capacity, capability and cross-border challenges associated with marine eradication programmes in Europe: the attempted eradication of an invasive non-native ascidian, Didemnum vexillum in Wales, United Kingdom. Mar. Policy 48, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.03.018

Savchenko, A. E., and Chernolutskaia, E. N. (2022). Limits of effectiveness of regional economic cooperation between the USSR and China in 1985-1988. Vestnik Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Univ. Istoriya-Tomsk State Univ. J. Hist. 78, 73–82. doi: 10.17223/19988613/78/10

Sorg, A., Mosello, B., Shalpykova, G., Allan, A., Clarvis, M. H., and Stoffel, M. (2014). Coping with changing water resources: the case of the Syr Darya River basin in Central Asia. Environ. Sci. Pol. 43, 68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.11.003

Stephenson, P. (2013). Twenty years of multi-level governance: ‘where does it come from? What is it? Where is it going?’. J. Eur. Public Policy 20, 817–837. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.781818

Strube, J., and Thomas, K. A. (2021). Damming rainy Lake and the ongoing production of hydrocolonialism in the US-Canada boundary waters. Water Altern. 14, 135–157. Available online at: https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol14/v14issue1/607-a14-1-2/file

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., and Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 14, 207–222. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.00375

Trbojevic, M., and Radovanovic, M. (2024). Disaster management in the Western Balkans territory - condition analysis and conceptualisation of the cross-border cooperation model. J. Homeland Secur. Emerg. Manag. 21, 243–271. doi: 10.1515/jhsem-2021-0038

Trondalen, J. M. (2004). Growing controversy over wise international water governance. Water Sci. Technol. 49, 61–66. doi: 10.2166/wst.2004.0416,

Uzomah, N. L. (2024). European union border technology in Africa: experiences en route. Popul. Space Place 30:2824. doi: 10.1002/psp.2824

VanNijnatten, D. L. (2020). The potential for adaptive water governance on the US-Mexico border: application of the OECD’S water governance indicators to the Rio Grande/Bravo Basin. Water Policy 22, 1047–1066. doi: 10.2166/wp.2020.120