- School of History and Culture, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

This article applied MDSD and process-tracing to compare the securitization acts of Italy regarding the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Baltic States’ withdrawal from the 17+1 Mechanism, analyzing them from the dimensions of driving factors and action pathways. The article finds that the securitization acts of both Italy and the Baltic States were driven by factors such as pressure from allies, ideological differences, geopolitical changes, and economic calculations. However, due to differences in national context and primary threat perception, Italy’s path aligns more closely with a Utilitarian logic, where actions are determined by a calculation of relative economic gains and alliance relationship cost. The Baltic States’ path corresponds more with a logic of ontological security, due to their security reliance on NATO and the Russia–Ukraine war, they emphasized a narrative of ideological confrontation between democracy and authoritarianism in their cooperation with China. In terms of action pathways, Italy engaged in intense political debates over the BRI, the turning point is Draghi government tightened the screening of Chinese investment and technology, then Meloni and members of BOI framed China as existential threat. The Baltic States directly use legislative power to constrict Chinese investment and technology in strategic sectors, and framed China as firm alliance of Russia to pose severe threat to EU’s security and democracy.

1 Introduction

The securitization of economic activities to serve political purposes is a common phenomenon in international relations. It often involves a country imposing sanctions on perceived sources of threats, typically specific nations or closely associated organizations and individuals, under the pretext of security concerns. For instance, the Biden administration tried to ban TikTok citing national security reasons and restricted semiconductor exports to China, among other measures. Scholars like Buzan argue that, aside from crises within the global economic system, there is no genuine economic security issue. Due to the inherently spillover nature of the economic domain, so-called “economic security” is often linked to the survival logic of other sectors (Buzan et al., 1998). This implies that most security screenings concerning economic cooperation, such as trade and investment, in the international system are driven by non-economic motives. However, the means to achieve economic securitization are not necessarily non-economic—examples include imposing protective tariffs, establishing investment screening mechanisms, and enacting economic penalties against relevant countries, organizations (primarily multinational corporations), and individuals. Portraying exports, investments, technologies, and even internet applications from competing countries as security threats has become increasingly commonplace in today’s world, and research on such securitization practices is relatively well-established (Wang, 2025).

However, these studies usually focus on the cases where a certain economic policy or cooperation project is securitized, and there are few studies on the securitization of a country’s global/regional economic initiatives or geo-economic strategies. The withdrawal of Italy from the China-led Belt and Road Initiative and the withdrawal of the Baltic States from the “17+1” Mechanism proposed by China provide comparable cases for observing the securitization behavior of global and regional economic initiatives. Unlike typical economic securitization cases, the main reasons for the withdrawal of these four countries from the economic cooperation initiatives and mechanisms led by China are said to be “not achieving the expected economic goals” and the threat to their ideology and values from China. However, neither the Belt and Road cooperation memorandums nor the “17+1” Mechanism involve specific economic benefit commitments. They are more about establishing cooperation intentions and building policy coordination platforms. The failure to achieve the expected investment and trade volume is not caused by the Belt and Road Initiative and the “17+1” Mechanism themselves. At the same time, these initiatives and mechanisms do not involve the promotion of ideology and values. Clearly, the withdrawal of Italy and the Baltic States has other hidden reasons.

Their behavior is contrary to the direction of securitization spilling over from the economic field to other fields. It belongs to the situation where non-economic fields spill over into the economic field. To analyze this phenomenon, we need to answer: Why did Italy and the Baltic States withdraw from the economic initiatives and economic cooperation mechanisms led by China? Did they adopt and what kind of securitization strategies did they adopt? These questions are the core of this study.

2 Theoretical perspective

The Copenhagen School opposes the traditional approach of security studies, which focuses primarily on military threats and adopts a state-centric orientation. Instead, it introduces the concept of securitization—a phenomenon in which an issue is presented as an existential threat to a relevant referent object (such as the state, government, or society), thereby justifying the state’s use of emergency measures (special powers) to address the threat. Securitization is an extreme form of politicization and consists of two key elements:

a. The intersubjective construction of an existential threat;

b. Response measures that break with routine politics.

In essence, securitization involves framing an issue as a primary and urgent threat, serving as a tool for securitizing actors to bypass routine political procedures and gain emergency powers (Buzan et al., 1998). The criterion for determining whether securitization has occurred is:

"whenever something took the form of the particular speech act of securitization, with a securitizing actor claiming an existential threat to a valued referent object in order to make the audience tolerate extraordinary measures that otherwise would not have been acceptable, this was a case of securitization" (Wæver, 2011).

In summary, securitization theory is a political theory that falls within the realm of human interaction and collective action. It involves the restructuring of power and obligation relationships among actors (speaker–audience) through speech acts (Wæver, 2015). The Copenhagen School expands the scope of securitization to five sectors: political, economic, military, societal, and environmental:

"Sectors serve to disaggregate a whole for purposes of analysis by selecting some of its distinctive patterns of interactions. But items identified by sectors lack the quality of independent existence…. Sectors might identify distinctive patterns, but they remain inseparable parts of complex wholes. The purpose of selecting them is simply to reduce complexity to facilitate analysis" (Buzan et al., 1998).

However, does this division of sectors represent an analytical perspective or does it carry ontological significance? Is securitization a differentiation within the political sector or an activity across different sectors? Drawing on the theory of functional differentiation, Albert and Buzan (2011) point out that the distinction between the political and economic sectors holds ontological significance, while the remaining three sectors are related to the perspective of observation—that is, they are shaped by social structures and narrative strategies. Securitization needs to be discussed within the context of the state, which implies that the division of sectors evolves alongside changes in social structures (the shift from traditional military-political security to non-traditional security reflects a transformation in social consciousness).

As mentioned earlier, due to the spillover nature of economic security, it often manifests as security demands in related domains, leading to ambiguity in the conceptual boundaries of economic security and its interconnectedness with other fields. Nevertheless, the academic community maintains a fundamental consensus on this concept. National economic security is widely defined as a country’s ability to protect its economy from internal and external threats while ensuring sustainable growth (Wang, 2025). The definition of economic security is highly correlated with changes in the international environment. During the Cold War, the concept of economic security emphasized the linkage between the economy and the military, focusing on resource allocation issues among different blocs (Mastanduno, 1998). In the post-Cold War era, the development of globalization shifted attention toward economic interdependence (Baldwin, 2016). Global trade networks are a double-edged sword, as their negative effects amplify the vulnerabilities of individual economies. Frequent international crises, such as the 2008 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia–Ukraine war, have spurred a revival of state-centric economic security studies. Researchers now place greater emphasis on resilience in the face of external shocks (Tooze, 2018) and the security of strategic sectors or critical supply chains (Farrell and Newman, 2019). Some studies also integrate non-traditional threats, such as cyber attacks (Segal, 2016).

Unlike economists’ focus on the generalized impact of economic security on the sustainable development of the international economy, international political economists study the phenomenon of economic securitization more from the perspectives of diplomatic relations and political interests. They argue that economic securitization describes a phenomenon where economics and security are interconnected in foreign interactions (Ren and Sun, 2021). This is manifested in states “politicizing” economic activities such as trade and investment on the grounds of security threats, using political security thinking to guide or intervene in their foreign economic activities.

In recent years, particularly policy-informing research has focused on the weaponization of interdependence. Unlike the classical theory of complex interdependence, Farrell and Newman (2019) propose a new perspective for understanding interdependence. They view economic interdependence as a structural force—a network architecture that can generate enduring, structural power imbalances among states. In their theory, the international economic network consists of “nodes” and “edges.” Nodes represent various actors in the network, while edges represent the connections that transmit information, resources, and influence between nodes, serving as the primary manifestation of interdependence. The more edges a node possesses, the denser its connections with other actors in the network. “Network structure” refers to the distribution of nodes and edges, which is closely related to the power of international actors. “Central nodes” or “hub nodes” occupying key positions in the network wield significant power, enabling them to alter the interests, identities, behaviors, and attitudes of other international actors, as well as to set and frame agendas. Once this asymmetric interdependent network structure is weaponized, the resulting economic coercion can jeopardize the autonomy of international actors, particularly states.

Concerns over economic coercion have prompted major international economic factors such as the United States, Japan, and the European Union to introduce economic security strategies. They claim that these measures are motivated by considerations of supply chain resilience, advocating strategies such as supply chain diversification, near-shoring, friend-shoring, and reshoring (onshoring) to enhance resilience. However, one of their unspoken primary objectives is to avoid excessive dependence on products and services from China, the “world’s factory,” lest they become subject to Chinese leverage. This has led them to adopt country-based risk identification and discriminatory policies: regarding goods and services from certain countries and regions as risks and attempting to reshape supply chains or reduce trade dependence; viewing exports of goods and services to certain countries and regions as risks and restricting them through export controls and technology embargoes; treating investments or mergers and acquisitions from certain countries and regions within their borders as risks and obstructing them through investment screenings; considering investments and mergers and acquisitions directed toward certain countries and regions as risks and imposing outward investment restrictions; and directly intervening in cross-border data flows, computing power layout, R&D outsourcing, and technical service provisions to certain countries or regions, deeming them risks. In short, the logic of this risk identification does not require sufficient evidence but simply presumes that the national origin of goods and services, as well as the national attributes of enterprises (even the nationality of shareholders and the national attributes of held enterprises), inherently equate to risk (Wang, 2025).

3 Methodology and selection of cases

Process-tracing serves as a powerful methodological supplement for securitization case studies, as it can clearly illustrate how securitization outcomes are achieved within a case—that is, how a series of mechanisms and facilitating conditions function (Robinson, 2017). However, the primary task of this article is first to identify the reasons for the securitizing acts by Italy and the Baltic States, and then to dissect the mechanisms. This implies that while employing process-tracing to delineate the causal mechanisms, this article also requires a comparative multi-case analysis to demonstrate causal effects (Wang, 2021). Therefore, the main methods adopted in this article are MDSD (most-different systems design) and process-tracing. The former is utilized for cross-case comparison between Italy and the Baltic States to analyze the reasons these countries withdrew from China-led economic cooperation initiatives, while process-tracing is applied to breaking down the causal mechanisms within each case. This demonstrates how, driven by a similar set of underlying reasons, security actors in different countries utilized different enabling conditions to achieve their objectives.

This article selects the withdrawal actions of Italy and the Baltic States as analysis objects for two main reasons. First, these four countries are the ones in Europe that have publicly announced their withdrawal from China’s economic cooperation initiatives. Studying the reasons behind their withdrawal and the pathways to achieving it holds profound practical implications for Chinese and European scholars and policymakers. Second, Italy and the Baltic States differ significantly in terms of national context, autonomy, collective memory and the scale of economic interactions with China. Yet, they all successively publicly announced their withdrawal from the BRI and the “17+1” Mechanism. This fits perfectly with the research requirements of the MDSD method, making them highly suitable for analyzing which common causes led to the withdrawal phenomenon.

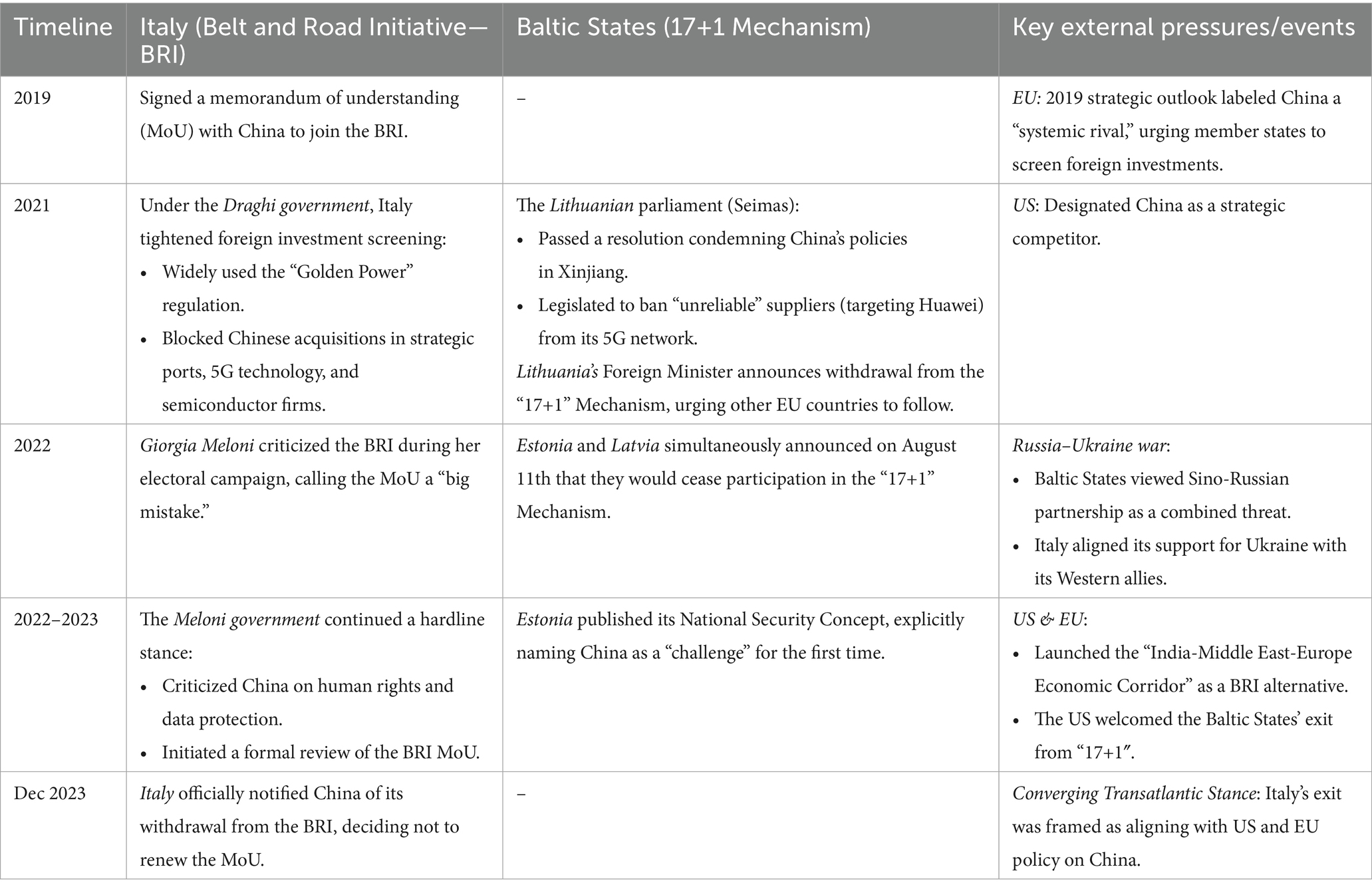

The methodological design for conducting within-case process-tracing requires a detailed presentation of the processes in these cases. Consequently, the analysis period spans from 2019 to December 2023. This timeframe covers key events such as Italy joining the BRI, the formal establishment of the “17+1” Mechanism, Lithuania announcing its withdrawal from “17+1,” Estonia and Latvia announcing their withdrawal from “17+1” on the same day, and the Meloni government in Italy announcing it would not renew the Belt and Road MoU. The consistency in the selected time period for the multi-case comparison also attempts to minimize differences in the impact of external events due to varying timeframes.

The primary data sources for this article are publicly available documents, statements, and related data from the official websites of China, Italy, the Baltic States, the United States, and the European Union, as well as interviews with relevant individuals and analyses from authoritative media outlets. These media sources include not only Chinese outlets like Global Times and Guancha.cn but also international authoritative media like the BBC and ANSA, as well as Lithuania’s local media LRT, striving for balanced and unbiased information sources.

At the level of conceptual operationalization, this article observes whether and how securitizing acts occurred through two dimensions: the discursive construction of an “existential threat” and policy/institutional changes. (1) The discursive construction of an “existential threat” refers to portraying participation in the BRI, “17+1,” and economic/technological cooperation with China as an existential threat to the nation, its people, or their way of life in official documents, political speeches, and media reports. This particularly includes employing a democracy vs. authoritarian narrative or politicizing economic and trade cooperation using political issues like Taiwan or Xinjiang. (2) At the level of institutional and policy changes, this primarily includes the introduction of extraordinary economic policies: activating special review mechanisms not commonly used in routine economic governance (e.g., strengthening foreign investment security screenings), implementing trade controls, protecting key sectors, etc. It also includes adjustments to the legal framework: bringing specific economic sectors (e.g., energy, finance, high-tech) under the scope of “national security” through legislation, often providing vague legal definitions to retain flexibility for intervention. The necessity of urgency and extraordinary measures involves emphasizing the immediacy of the economic threat and justifying emergency actions (such as administrative interventions or special legislation) that bypass routine political procedure.

4 Historical background

In March 2019, Italy and China signed a Memorandum of Understanding on the Belt and Road Initiative and issued a joint statement, which stated that: both sides recognize the huge potential of the Belt and Road Initiative in promoting connectivity and are willing to enhance the alignment of the Belt and Road Initiative with the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) and other initiatives, and deepen cooperation in ports, logistics and maritime transport. The Italian side is willing to build on the EU’s “EU Strategy on Connecting Europe and Asia” and take advantage of the opportunities provided by the China-EU Connectivity Platform to leverage its own strengths and cooperate with China. Both sides confirm their willingness to work together within the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to promote connectivity in line with the AIIB’s mission and functions. Both sides also expressed their desire to increase air links between the two countries and provide convenience for airlines of both sides to operate and enter each other’s markets (Guancha.cn, 2019).

However, 4 years later, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni informed Chinese Premier Li Qiang of Italy’s decision to withdraw from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Italy formally notified China of its exit in December 2023, just months before its membership was set to automatically renew in March 2024 for another five-year term. During her campaign for the September 2022 general elections, Meloni had already criticized the initiative, calling the memorandum of understanding (MoU) a “big mistake.” In September 2023, Italian Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani stated that “BRI membership has not produced the results we were hoping for.” Defense Minister Guido Crosetto went further, describing the decision to join as an “improvised and atrocious act” (Amaro, 2023).

In contrast, in August 2023, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs highlighted that since the signing of the MoU, bilateral trade between China and Italy had increased by 42%, reaching nearly $80 billion the previous year. Italy had been invited as a guest of honor at the Shanghai Import Expo and the Hainan Consumer Expo, enabling many Italian products to enter the Chinese market. The two countries collaborated on building large cruise ships and pursued third-market cooperation in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. Italy also became one of the most popular European travel destinations for Chinese tourists, and numerous Italian cultural and artistic exhibitions were warmly received in China (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, 2023). If expanded bilateral trade and closer Sino-Italian relations were not the outcomes Italy had hoped for, what exactly were they expecting?

Coincidentally, in May 2021, Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis announced the country’s withdrawal from the“17+1”cross-regional cooperation mechanism between China and Central and Eastern European countries. Landsbergis also urged other European countries to follow suit and exit the “17+1” Mechanism, accusing it of being a “divisive” factor for the European Union (Global Times, 2021). In November 2022, the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a statement on its website announcing that the country had not attended any meetings since the summit in February of the previous year and had decided not to participate in the cooperation mechanism. On the same day, the Latvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs made a similar announcement on its website, stating that, considering current diplomatic and trade policy priorities, Latvia would cease its participation in the mechanism (Guancha.cn, 2022).

The “17+1” Mechanism, officially known as the China-Central and Eastern European Countries Summit (17 CEE countries + China), held its first meeting in Warsaw in 2012. With Greece joining the mechanism in 2019, it was upgraded from “16+1” to “17+1.” Since 2012, trade between China and the 17 CEE countries has increased by nearly 85%, with an average annual growth rate of 8%—more than three times the growth rate of China’s overall foreign trade. In 2020, trade between China and these 17 countries exceeded $100 billion for the first time, reaching $103.45 billion. Despite the global COVID-19 pandemic, trade grew by 8.4% year-on-year, a rate more than four times that of China’s overall foreign trade during the same period. Specifically, trade between China and the 16 original member countries reached $95.64 billion, surpassing $90 billion for the first time and achieving an overall increase of 83.7% since the mechanism’s establishment (Han, 2021). This significant growth in trade volume clearly demonstrates the vast potential for market cooperation between China and the CEE countries.

In summary, both the Belt and Road Initiative and the “17+1” Mechanism, as global and regional economic cooperation platforms promoted by China, have provided participating countries with opportunities for trade and investment growth, particularly in infrastructure improvement, without attaching any conditions related to ideology or political values. So why did Italy and the Baltic States choose to withdraw one after another? Although the memorandums and mechanisms are symbolic and not legally binding, staying involved would at least entail no loss, while withdrawing carries the risk of deteriorating relations with China. Despite this, why did they still decide to exit?

5 Factors driving securitization

Comparing Italy’s withdrawal from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Baltic States’ exit from the “17+1″ Mechanism, it becomes evident that all four countries were influenced by pressure from allies (primarily the United States and the European Union) as well as ideological factors. The difference lies in the fact that Italy’s decision was driven more by frustration resulting from misaligned expectations with China, whereas the Baltic States were motivated to a greater extent by historical trauma and geopolitical considerations.

5.1 Pressure from Allies

Both Italy and the Baltic States were significantly influenced by the stance of their allies, such as the United States and the European Union, in shaping their policies toward China. The U.S. government and the European Commission have identified China as a key strategic competitor and have successively formulated economic security strategies to address perceived risks such as so-called economic coercion posed by China.

On the U.S. side, the first Trump Administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy asserted that “China seeks to displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region, expand the reaches of its state-driven economic model, and reorder the region in its favor.” It accused China of leveraging global economic initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative to coerce and induce other countries, thereby strengthening its geopolitical influence. In response, the U.S. declared it would “use existing and pursue new economic authorities and mobilize international actors to increase pressure on threats to peace and security in order to resolve confrontations short of military action.” The Trump administration specifically highlighted that “China is gaining a strategic foothold in Europe by expanding its unfair trade practices and investing in key industries, sensitive technologies, and infrastructure.” As a result, the U.S. committed to working with its allies to “contest China’s unfair trade and economic practices and restrict its acquisition of sensitive technologies” (2017 U.S. NSS).

In the 2022 National Security Strategy released by the Biden Administration (2022), China was further characterized as “the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it.” The report more directly accused China of economic coercion and weaponizing interdependence, stating: “Beijing frequently uses its economic power to coerce countries. It benefits from the openness of the international economy while limiting access to its domestic market, and it seeks to make the world more dependent on the PRC while reducing its own dependence on the world.” To counter China’s alleged strategy of “weaponizing interdependence,” the U.S. pledged to support allies “to make sovereign decisions in line with their interests and values, free from external pressure,” and to “work to provide high-standard and scaled investment, development assistance, and markets” (2022 U.S. NSS).

On the EU side, its 2019 report EU-China—A Strategic Outlook for the first time characterized China as “an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance.” It called for establishing “a more balanced and reciprocal economic relationship” with China, implicitly criticizing what it perceived as unfair and non-reciprocal Chinese economic practices. The document also warned EU member states about the “Trojan horse” risk posed by certain Chinese investments: “To detect and raise awareness of security risks posed by foreign investment in critical assets, technologies and infrastructure, Member States should ensure the swift, full and effective implementation of the Regulation on screening of foreign direct investment.” Furthermore, it emphasized that the EU must not allow China to divide it: “Neither the EU nor any of its Member States can effectively achieve their aims with China without full unity. In cooperating with China, all Member States, individually and within sub-regional cooperation frameworks, such as the 16+1 format, have a responsibility to ensure consistency with EU law, rules and policies”(European Commission, 2019). This specific mention of the “16+1” Mechanism reflects long-standing concerns among senior Brussels bureaucrats that such cooperation frameworks could fragment European unity.

In 2023, the European Commission expressed growing concerns over several risks, including:

• Risks to the resilience of supply chains, including energy security;

• Risks to the physical and cyber-security of critical infrastructure;

• Risks related to technology security and technology leakage;

• The risk of weaponization of economic dependencies or economic coercion.

To guard against these threats—particularly from non-market economies such as China—the Commission urged faster deployment of the Foreign Subsidies Regulation and full implementation of the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Screening Regulation (European Commission, 2023, 2024).

China’s growing economic, technological, and industrial capabilities have heightened concerns in the United States and the European Union regarding its perceived threat and strategic intentions. This has, to some extent, pressured these four countries to demonstrate alignment with the U.S. and EU through tangible actions. The decisions of Italy to withdraw from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Baltic States to exit the “17+1” Mechanism show clear signs of external influence.

Since taking office in 2022, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has pursued a more pro-Western and pro-NATO foreign policy compared to her predecessors (BBC, 2023). During her meeting with U.S. President Joe Biden in Washington in July 2023, both leaders committed to “strengthen bilateral and multilateral consultations on the opportunities and challenges posed by the People’s Republic of China” (Sacks, 2023). The Biden administration had already made its opposition to Italy’s renewal of the BRI memorandum clear. To reinforce transatlantic solidarity, U.S. persuasion undoubtedly played a significant role in shaping Italy’s decision (Hong, 2023). Although Meloni had criticized EU institutions during her 2022 election campaign, her administration has adopted a more pragmatic approach toward the EU since taking power, often aligning its policies with Brussels to establish Italy as a reliable member state (Wang, 2024). This also implies that Italy will strive to harmonize with EU standards in areas such as foreign investment screening. As noted by the Council on Foreign Relations, “Italian withdrawal from the BRI would reflect the growing transatlantic convergence on the challenge China poses” (Sacks, 2023).

The extent of a country’s power determines its room for maneuver within the international system. If Italy’s decision was influenced relatively indirectly by allied pressure, the Baltic States felt a more urgent need to unequivocally align themselves with the U.S. and EU positions. When announcing Lithuania’s withdrawal from the “17+1” Mechanism, Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis urged other European countries to follow suit, criticizing the format as “divisive” to EU unity. He argued that EU member states should abandon the “divisive ‘17+1′ model” and instead adopt a “more effective and united ‘27+1′ approach” in engaging with China (Chen, 2021; Lau, 2021). In 2022, when Estonia and Latvia announced their withdrawals from the “17+1″ Mechanism on the same day, U.S. State Department Deputy Spokesperson Vedant Patel welcomed the decision during a press briefing. He stated that the United States “respects and supports this sovereign decision” and will “continue to support Estonia and Latvia in their efforts to foster a more stable and prosperous Baltic region.” Patel emphasized that both countries are “important NATO allies and key partners to the United States on many issues,” adding that a central element of the Biden administration’s China policy is to “maintain alignment with allies across Europe and around the world” (Guancha.cn, 2022).

5.2 Ideological differences

Regarding the ideological and value-based differences between Italy, the Baltic States, and China, these four countries have sought to link the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the 17+1 Mechanism with issues such as Taiwan and human rights in China, framing their securitization actions within a narrative of “democracy vs. authoritarianism.”

In an interview with Taiwanese media, Meloni stated that China and Russia are attempting to establish a new anti-democratic world order, with China posing a threat to democratic values—particularly on the Taiwan issue. She emphasized that her right-wing coalition government firmly stands on the side of the anti-authoritarian camp (ANSA, 2022). Meloni’s reasons for withdrawing from the BRI include China’s suppression of Hong Kong activists, its claims over Taiwan, discrimination against the Uyghurs, and China’s controversial stance on the Russia–Ukraine war (Nadalutti and Rüland, 2024). Meloni adopted this approach partly to gain favor with the Biden administration and the increasingly China-skeptic European Union. On the other hand, a friendlier stance toward Taipei would allow her to monopolize a discourse rarely addressed by Italian politicians and help improve the standing of her far-right Brothers of Italy party by leveraging the “democracy vs. authoritarianism” narrative.

In China, Lithuania is known as a “vanguard of anti-China sentiment,” notorious for its sharp criticisms and strong diplomatic maneuvers against China. Between 2019 and 2023, Lithuania first accused China of threatening its national security and repeatedly provoked China on issues related to Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Taiwan. It then announced its withdrawal from the “17+1” Mechanism and later allowed the Taiwanese authorities to establish a “Taiwanese Representative Office” in Vilnius—making it the first country with diplomatic ties with China to permit the use of the name “Taiwan” for such an office (Peng, 2024). Shortly before announcing its exit from the 17+1 Mechanism, Lithuania’s parliament, Seimas, passed a resolution condemning China’s treatment of its Uighur Muslim minority as “crimes against humanity” and “genocide.” It also called for a UN investigation into Beijing’s internment camps for Uighurs and urged the European Commission to reassess its relations with China (LRT.lt, 2021a).

Regarding the withdrawal of Estonia and Latvia, Sarah Kreps notes that as the Ukraine crisis dragged on and tensions in the Taiwan Strait escalated due to U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan, small states like Latvia and Estonia sought to “express loyalty” to the United States and other Western nations. By doing so, they aimed to solidify their position within the “pro-democracy” camp—much as during the Cold War. “These two countries are trying to send a very clear signal that they belong to the camp that supports ‘democracy,’ and they do not wish to align with countries perceived as opposing ‘democracy’” Kreps stated. “They want to demonstrate their loyalty… so that if they are in a vulnerable position, the U.S. and its Western allies will remember that and ensure they are repaid with strong defensive support” (Guancha.cn, 2022).

5.3 Geopolitical changes

With the outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war, strategic anxiety within the European Union and its member states toward Russia reached a peak. Condemning and sanctioning Russia, while voicing support for Ukraine, became the international diplomatic “correctness.” China’s refusal to openly criticize Russia became a significant factor leading Italy and the Baltic States to suspend cooperation. However, the impact of this major geopolitical shift brought about by the Russia-Ukraine war differed in weight between Italy and the Baltic States. For Italy, supporting Ukraine was a move to strengthen strategic coordination with the EU and the United States. China’s stance toward Russia had an indirect effect and served only as one of the catalytic factors in Italy’s decision to withdraw from the Belt and Road Initiative (Nadalutti and Rüland, 2024).

For the Baltic States, however, China and Russia are both viewed as challengers to the existing international order. As Frank Jüris, a China relations expert and research fellow at the ICDS’ Estonian Foreign Policy Institute, tweeted:

"In the defense of a rules-based world order, every country has a role to play! Estonia is not only showing the way in regard to Russia but also being the trailblazer in relations with China by leaving the 16+1 format of Chinese influence and co-option" (Vahtla, 2022).

China’s failure to clearly condemn Russia’s war against Ukraine, coupled with its declaration of a “no-limits” friendship with Vladimir Putin, is anathema to the Baltic States. They fear that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine could be a precursor to a broader attempt by Russia to reclaim its Soviet-era empire.

Underlying this geopolitical anxiety is the memory of Soviet aggression, oppression, and brutal rule over the Baltic States. These painful historical memories have been reignited by the current geopolitical reality of the Russia-Ukraine war. As a result, Russia is perceived as the greatest security threat by these countries, while China—increasingly aligned with Russia—is viewed as a concurrent challenger to the rules-based international order: another revisionist power. Thus, withdrawing from the 17+1 Mechanism serves as a political statement by the Baltic States: a stand against the perceived “axis of evil” formed by China and Russia, and an effort to block their expanding geopolitical ambitions. It must be noted that the Cold War mentality in these former Soviet bloc countries has not faded with time.

5.4 Economic calculations

The Baltic States had relatively limited economic engagement with China, and their trade relations were largely characterized by a trade surplus in China’s favor. As a result, withdrawing from the 17+1 Mechanism did not impose significant economic pressure on them. Lithuanian Ambassador to China, Diana Mickeviciene, argued that the decision was a reaction to the framework’s underwhelming economic outcomes. In 2020, China ranked 22nd among Lithuania’s export destinations. Meanwhile, Chinese exports to Lithuania grew rapidly, further widening the trade imbalance (Stec, 2021). China accounted for only 1% of Lithuania’s exports, meaning the Baltic state had less to lose compared to some of its European allies, noted Marcin Jerzewski, an expert on EU–Taiwan relations. At the same time, the Baltic countries stood to gain economic compensation from the Taiwanese authorities due to their confrontational stance toward China on Taiwan-related issues. As one report indicated, Taiwan—a major economy in its own right—was seen as a reliable alternative market for Lithuanian products (Nevett, 2021).

For Italy, however, the situation was entirely different. The country had originally intended to leverage its participation in the BRI to gain greater access for Italian products in the Chinese market and attract more investment from Chinese enterprises. Yet, the BRI MoU between Italy and China was not structured as a concrete economic or trade agreement. Instead, it expressed a general willingness to cooperate under the BRI framework and served largely as a symbolic gesture to enhance China’s global image as a provider of public goods (Mazzocco, 2023). This misalignment of expectations inevitably led to Italy’s frustration with the cooperation. When Italy decided to join the BRI in 2019, it had just endured three recessions within a decade and was eager to attract foreign investment and expand exports to China’s vast market. At the time, many Italians felt abandoned by Europe, and the populist government was skeptical of the EU—making China an appealing alternative for meeting its investment needs. Italy saw an opportunity to use its political influence to secure Chinese attention and investments ahead of other countries. However, trade and investment are market-driven, and Italy was clearly not the most favored partner for Chinese businesses or in the Chinese market. Joining the BRI does not automatically grant a country special status with China or guarantee increased trade and investment. Prime Minister Meloni pointed to the lack of tangible benefits following Italy’s accession, noting that “Italy is the only G7 member that signed up to the BRI, yet it is not the European or Western country with the strongest economic relations and trade flows with China” (Sacks, 2023).

Amid these unmet economic expectations, the United States offered Italy and other countries alternative options aimed at countering China’s growing influence in Europe and globally. In September 2023, just 3 months before Italy’s withdraw, US President Joe Biden, along with the leaders of India, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, announced the launch of a new trade corridor connecting India to the Middle East and Europe through railways and ports. The White House stated that the project would open a “new era of connectivity.” Some analysts view it as a direct challenge to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (Ebrahim, 2023).

6 Securitization pathways

Driven by pressure from allies, ideological differences, changes in the geopolitical landscape and economic calculations—though to varying degrees—Italy and the Baltic States decided to withdraw from the China-led Belt and Road Initiative and the 17+1 Mechanism. Their securitization actions and processes also differed, reflecting their distinct strategic circumstances and their respective positioning toward China.

6.1 Italy’s securitization pathway

Italy’s securitization of the Belt and Road Initiative involved extensive internal debate and unfolded over a relatively long period. At the time of signing the memorandum, the Italian government was divided over whether to endorse the agreement with China. Matteo Salvini, then interior minister and one of the top leaders of the coalition government in March 2019, was openly skeptical of the agreement. “If it’s a matter of helping Italian companies to invest abroad we are willing to talk to anyone,” Salvini said. “If it’s a question of colonising Italy and its firms by foreign powers, no and the treatment of sensitive data is a national interest. Therefore the issue of telecommunications and the treatment of data cannot be merely economic” (ANSA, 2019). The League is split on Italy’s memorandum of understanding with China on the BRI but the 5-Star Movement is solidly with businesses on it. League leader Salvini had spoken of colonisation while Industry Undersecretary Michele Geraci, also of the League, “strongly supports the agreement.”

6.1.1 Policy changes as the turning point: Draghi government tightened the screenings of Chinese investment and technology

After the signing, the economic cooperation between the two countries did not go smoothly either. Italy has strengthened its scrutiny of Chinese investments over fears about inappropriate technology transfer, under former Prime Minister Mario Draghi, who preceded Meloni’s government and followed Conte’s (Mazzocco, 2023). Draghi took a much more circumspect course toward Beijing. Tightening the 2012 “golden power” law, a legal mechanism to regulate FDI in security-relevant economic sectors, Draghi’s government blocked Chinese investments in critical infrastructure such as the ports in Trieste and Genoa, 5G telecommunication technology, and space technology. With these measures Draghi realigned Italy with the West’s China-critical “de-risking” policy. The Draghi government also halted the acquisition of the Italian semiconductor company LPE by Shenzhen Investment Holding, and vetoed the creation of a joint venture between Zhejiang Jingsheng Mechanical and the Hong Kong branch of Applied Materials, a leader in software production for semiconductors. His intervention also involved other sectors, such as in the case of the food company Verisem, which was in talks to be acquired by a Swiss firm largely owned by Chinese state-owned giant Sinochem. At the same year, Draghi announced his plan to re-examine the conditions of Italy’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative. On China, Giorgia Meloni appears to be following in the footsteps of her predecessor by maintaining a skeptical stance and calling for a reassessment of the Belt and Road memorandum signed in 2019. Her outspoken criticism of Beijing became particularly visible during the pandemic through her Twitter activity, where she raised concerns over human rights issues and insufficient data protection—often using such rhetoric to undermine rival political parties that held softer attitudes toward China. In an interview with Reuters, she pledged to counter Chinese and Russian ambitions in the West and vowed that Italy would not become “a weak link” in the Western alliance under her leadership (Gragnani, 2022).

6.1.2 Discursive construction: Meloni and members of BOI framed China as an existential threat

Within her party, Brothers of Italy (BOI), there appears to be broad consensus regarding a firm approach to China. Deputy Federico Mollicone has labeled Beijing “a new enemy,” comparable to state sponsors of terrorism. Nicola Procaccini, a BOI member of the European Parliament, has criticized China’s expanding influence in the EU’s strategic sectors and called for a tougher stance. At the regional level, Francesco Torselli, a BOI representative on the Regional Council of Tuscany, has voiced concerns over the growing presence of Chinese enterprises in the area, arguing that they pose unfair competition to smaller Italian businesses. The party’s hawkish posture seems to be motivated both by concerns over the vulnerability of Italian and European industries and by opposition to Chinese immigration (Gragnani, 2022). Giorgia Meloni has consistently rejected a hedging strategy toward China. In light of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, escalating tensions between the U.S. and China, and the limited economic returns from Italy’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, she believes that Italy’s security interests are better served through a recalibrated balancing strategy (Nadalutti and Rüland, 2024).

6.2 The securitization pathway of the Baltic States

In contrast to Italy, the securitization measures taken by the three Baltic States were more direct. They perceived China as an emerging security threat (often associated with the threat from Russia) and, taking into account factors such as supply chain resilience and China’s potential weaponization of interdependence, they securitized Chinese investments, technologies, and the 17+1 Mechanism itself, ultimately announcing their immediate withdrawal from the framework.

6.2.1 Institutional changes: Seimas passed law to constrict Chinese technology and investment in strategic sectors

Prior to exiting the 17+1 Mechanism, Seimas passed amendments to the Law on Communications and the Law on the Protection of Objects of Importance to Ensuring National Security. These amendments prohibit unreliable manufacturers and suppliers from participating in the electronic communications market and require that equipment be vetted for compliance with national security interests before radio frequencies are allocated for 5G networks. Lithuanian military intelligence has stated that Huawei’s involvement in the development of 5G wireless infrastructure poses a security risk, citing Chinese laws that require companies to share information with the government. In response, Telia has begun replacing Huawei equipment with next-generation Ericsson mobile base stations across Lithuania (LRT.lt, 2021b). Beyond skepticism toward Chinese communication technology, there were deeper concerns. “China has aims to take over strategic infrastructure in various countries, […] why should we embroil ourselves in these risks?” However, the underlying worry was the political cost of engaging with China, since deeper cooperation with Beijing could strain relations with the United States—the region’s primary security guarantor (LRT.lt, 2021c).

6.2.2 Discursive construction: Latvian Prime Minister and Estonian prime minister framed China as firm alliance of Russia to pose severe threat to EU’S security and democracy

Latvian Prime Minister Kariņš expressed interest in strengthening the EU’s economic autonomy, noting that the COVID-19 pandemic had exposed the bloc’s dependence on products from third countries, particularly China, and highlighted vulnerabilities in supply chains. He emphasized that promoting production development within the EU aligns with Latvia’s interests and supports the goals of smart reindustrialization, creating new opportunities for production models. The implementation of the European Green Deal is also crucial for Latvia to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, which are largely imported from Russia. At the same time, Kariņš (2022) stressed the need to implement the Green Deal’s goals wisely and pragmatically to ensure societal benefits. All of this indicates that the Latvian government intends to reduce its reliance on “authoritarian countries” such as China and Russia in terms of economy and energy, in order to ensure its economic security. Estonian Prime Minister Kallas pointed out the need to remain vigilant regarding China’s behavior (Eesti Vabariigi Valitsus, 2021). In Estonia’s National Security Concept, one of the key updates is the clear identification of the Russian Federation as the greatest security threat to Estonia, citing its goal to dismantle and reshape the European security architecture and the rules-based world order while reinstating a policy of spheres of influence. Another notable change from the 2017 version is the mention of China—which is expanding its influence internationally and in strategic sectors—as a challenge for the first time (Eesti Vabariigi Valitsus,2023).

The Table 1, Figure 1 above reveals two distinct causal pathways for securitization:

6.2.3 Italy’s path: gradual securitization driven by a cost–benefit calculus

The core logic was a process of strategic weighing and calculation. Italy’s initial participation was motivated by the expectation of economic gains. Its decision to exit was driven by the failure to meet these economic expectations, coupled with the rising political and diplomatic costs of maintaining the cooperation within the transatlantic alliance. The Draghi government served as the pivotal turning point, systematically reframing economic engagement with China from an “opportunity” to a “risk.” This was operationalized through technical policy tools like the “Golden Power” mechanism, which laid the groundwork for securitization and paved the way for the Meloni government’s final withdrawal. The process was prolonged and involved significant internal debate. Securitization was achieved not through sudden declaration, but through a gradual escalation of policy measures.

6.2.4 The Baltic States’ path: radical securitization driven by an existential threat perception

This was an identity and survival-driven process. As frontline NATO states with a deep historical trauma regarding Russia, the Baltic States perceived the war in Ukraine through a lens of existential threat. In this context, they framed China as an ally of Russia and a concurrent challenger to the Western “rules-based international order.” Their securitization moves were direct and swift. They bypassed prolonged internal debate, instead using legislation, official statements, and the act of withdrawal itself to categorically define China and the cooperation frameworks as a clear and present security threat. The process was immediate and decisive. Securitization was accomplished through overt threat-framing and a clean political break.

In summary, the causal mechanism diagram demonstrates that: shared driving factors (top level) were interpreted through distinct national filters (middle level: national context and primary threat perception), which ultimately gave rise to differentiated securitization pathways and behaviors (bottom level). Italy’s path aligns more closely with a Utilitarian logic, where actions are determined by a calculation of material gains and losses. The Baltic States’ path corresponds more with a logic of Ontological Security—the need to secure a stable sense of self and identity, which in this case was profoundly threatened by the resurgent Russian aggression and China’s perceived association with it. Despite these divergent paths, both culminated in the same policy outcome: withdrawal from China’s regional economic initiatives and alignment with the US and EU-led strategy of “de-risking” from China.

7 Conclusion

Italy’s withdrawal from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Baltic States’ exit from the “17+1” Mechanism provide a comparative multinational case study on the securitization of China’s global and regional economic initiatives. Drawing on securitization theory and recent advances in economic security research—such as the weaponization of interdependence—we find that the securitization actions of Italy and the Baltic States were primarily influenced by factors including pressure from allies, ideological differences, geopolitical changes, and economic calculations. However, due to differences in national context and historical memory, Italy’s decision to withdraw was mainly driven by unfulfilled economic expectations and a desire to strengthen transatlantic alliances, with ideological and geopolitical factors playing a more indirect role. In contrast, the Baltic States, which rely heavily on NATO for security and reached a peak of strategic alarm regarding Russia following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, placed greater emphasis on a narrative of democracy vs. authoritarianism in their exit process, with economic considerations carrying less weight. In terms of implementing securitization, Italy engaged in an extended political debate and a gradual process of imposing security reviews on Chinese investments and technologies. The Baltic States, on the other hand, explicitly framed China as a security threat, securitizing the 17+1 cooperation mechanism by citing concerns over supply chain resilience and the weaponization of interdependence, ultimately leading to their announcement of withdrawal.

This comparative case study offers at least two policy insights for European and Chinese policymakers who intend to advance global and regional economic cooperation initiatives in Europe:

(1) European countries should not politicize their economic and trade cooperation with China. In particular, they should not resort to the narrative of democracy vs. authoritarianism and use issues such as Taiwan and Xinjiang as excuses. This is a political red line for China and will only further deteriorate the relations between the two countries.

(2) The Central and Eastern European countries, especially those in the former Soviet bloc, should not tie China to Russia in terms of strategy. They should abandon the mindset of ideological camp division and adopt a pragmatic approach towards China’s technologies and products. They should also introduce Chinese investment in infrastructure construction to achieve their own development.

(3) For Chinese policymakers and enterprise: under principled cooperation frameworks such as memorandums of understanding and high-level dialogues, more concrete, structured, and goal-oriented economic agreements should be concluded. For instance, specific technical collaboration projects could be signed with Italy in the new energy vehicle industry. Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers interested in establishing production lines and sales outlets in Italy should be encouraged to engage with the Italian government on detailed cooperation plans, clarifying tangible benefits such as technology upgrades and job creation for Italy.

(4) China should active response to address the security concerns of European countries, especially smaller states. Regular security dialogues could help alleviate anxieties, while people-to-people exchanges between civil society organizations in China and target countries should be strengthened. Increased public diplomacy efforts would improve China’s national image within these societies, truly embodying the principle of “policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds.”

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JL: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albert, M., and Buzan, B. (2011). Securitization, sectors and functional differentiation. Secur. Dialogue 42, 413–425. doi: 10.1177/0967010611418710

Amaro, S. (2023). Italy’s BRIexit: Not All Roads Lead to Beijing. Available online at: https://www.orfonline.org/research/italy-s-briexit-not-all-roads-lead-to-beijing (accessed March 4, 2025)

ANSA. (2019).China/Italy: no to colonisation on Belt and Road-Salvini. Available online at: https://www.ansa.it/english/news/2019/03/11/chinaitaly-no-to-colonisation-on-belt-and-road-salvini_268eef47-4669-4334-96ce-794b7f906aba.html (accessed May 22, 2025)

ANSA. (2022).Meloni: "Non rinnoverei l'adesione alla via della seta cinese." Available online at: https://www.ansa.it/sito/notizie/politica/2022/09/23/meloni-non-rinnoverei-ladesione-alla-via-della-seta-cinese_c6c5a8b3-a9a7-4d82-91cc-41d669584cd5.html#google_vignette (accessed May 22, 2025)

Baldwin, R. (2016). The great convergence: Information technology and the new globalization. Cambridge, MA: The belknap press of Harvard University press.

BBC. (2023). Belt and Road: Italy pulls out of flagship Chinese project. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-67634959 (accessed March 4, 2025)

Buzan, B., Waever, O., and de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: a new framework for analysis. Boulder, London: Lynne Rienner Publisher.

Chen, S.J. (2021). Lithuania has withdrawn from the China-CECC 17+1 cooperation. Available online at: https://k.sina.com.cn/article_1887344341_707e96d5020012vu1.html (accessed May 22, 2025)

Ebrahim, N. (2023). New US-backed India-Middle East trade route to challenge China’s ambitions. Available online at: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/09/11/middleeast/us-india-gulf-europe-corridor-mime-intl/index.html (accessed May 22, 2025)

Eesti Vabariigi Valitsus. (2021). Prime Minister Kallas will discuss strengthening the alliance’s deterrence and defence stance at the NATO Summit. Available online at: https://www.valitsus.ee/en/news/prime-minister-kallas-will-discuss-strengthening-alliances-deterrence-and-defence-stance-nato (accessed July 9, 2025)

Eesti Vabariigi Valitsus. (2023). Speech of the Prime Minister Kaja Kallas at the presentation of the National Security Concept in the Riigikogu on 6 February 2023. Available online at: https://www.valitsus.ee/en/news/speech-prime-minister-kaja-kallas-presentation-national-security-concept-riigikogu-6-february (accessed July 9, 2025)

European Commission. (2019). EU-China–a strategic outlook. JOIN (2019) 5 final. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2023). European economic security strategy. JOIN (2023) 20 final. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2024). Advancing European economic security: an introduction to five new initiatives. COM (2024) 22 final. Brussels: European Commission.

Farrell, H., and Newman, A. (2019). Weaponized interdependence: how global economic networks shape state coercion. Int. Secur. 44, 42–79. doi: 10.1162/isec_a_00351

Global Times. (2021). Lithuania's withdrawal from the "17+1" cooperation mechanism has not affected the achievements made over the past nine years since its establishment, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said. The mechanism will not be affected by individual incidents. Available online at: https://world.huanqiu.com/article/43FmuxGb281 (accessed March 14, 2025)

Gragnani, L. (2022). The new Italian government could be a headache for China. Available online at: https://chinaobservers.eu/the-new-italian-government-could-be-a-headache-for-china/ (accessed May 23, 2025)

Guancha.cn. (2019). China-Italy joint communique: memorandum of understanding on jointly promoting the Belt and Road initiative. Available online at: https://www.guancha.cn/internation/2019_03_23_494776.shtml (accessed June 9, 2025)

Guancha.cn. (2022). Estonia and Latvia announced their withdrawal from the China-CEEC cooperation mechanism. Experts: a gesture of loyalty to the US and the West. Available online at: https://www.guancha.cn/internation/2022_08_12_653427.shtml (accessed May 26, 2025)

Han, M. (2021). The 17+1 cooperation initiative has facilitated the further upgrading of the cross-regional multilateral cooperation model. Available online at: http://www.cass.cn/xueshuchengguo/guojiyanjiuxuebu/202102/t20210219_5312281.shtml (accessed May 26, 2025)

Hong, X. (2023).The US forced Italy to withdraw from the "Belt and Road Initiative"? Experts' interpretation: the final decision remains to be seen. Available online at: https://news.hbtv.com.cn/p/2641098.html (accessed July 15, 2025)

Kariņš, K. (2022). Latvijas ārpolitikas kursa pamatā ir sadarbības stiprināšana ar ES un NATO. Available online at: https://www.mk.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/karins-latvijas-arpolitikas-kursa-pamata-ir-sadarbibas-stiprinasana-ar-es-un-nato (accessed July 4, 2025)

Lau, S. (2021). Lithuania pulls out of China’s 17+1 bloc in Eastern Europe. Available online at: https://www.politico.eu/article/lithuania-pulls-out-china-17-1-bloc-eastern-central-europe-foreign-minister-gabrielius-landsbergis/ (accessed May 26, 2025)

LRT.lt. (2021a). Lithuania quits ‘divisive’ China 17+1 group. Available online at: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1416061/lithuania-quits-divisive-china-17plus1-group (accessed May 26, 2025)

LRT.lt. (2021b). Lithuania bans ‘unreliable’ technologies from its 5G network. Available online at: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1417429/lithuania-bans-unreliable-technologies-from-its-5g-network (accessed May 26, 2025)

LRT.lt. (2021c). Lithuania mulls leaving China’s 17+1 forum, expanding links with Taiwan. Available online at: https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1356107/lithuania-mulls-leaving-china-s-17plus1-forum-expanding-links-with-taiwan (accessed May 26, 2025)

Mastanduno, M. (1998). Economics and security in statecraft and scholarship. Int. Organ. 52, 825–854. doi: 10.1162/002081898550761

Mazzocco, I. (2023). Italy withdraws from China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Available online at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/italy-withdraws-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed March 4, 2025)

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC. (2023). Foreign Ministry spokesperson’s response to media reports on Italy’s consideration of not extending the belt and road cooperation document. Available online at: https://www.mfa.gov.cn/fyrbt_673021/dhdw_673027/202308/t20230804_11122253.shtml (accessed March 14, 2025)

Nadalutti, E., and Rüland, J. (2024). What explains Rome’s brief engagement with the BRI? Available online at: https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/hedging-light-italys-intermezzo-with-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/ (accessed May 23, 2025)

Nevett, J. (2021). Lithuania: the European state that dared to defy China then wobbled. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-59879762 (accessed May 26, 2025)

Peng, X. Z. (2024). The changes in Lithuania's policy towards China and its provocative actions regarding Taiwan. Available online at: https://gb.crntt.com/doc/1069/7/5/6/106975691.html?coluid=266&kindid=0&docid=106975691&mdate=1031110546 (Accessed July 15, 2025)

Ren, L., and Sun, Z. M. (2021). Securitization of economic issues and the network power of hegemony. World Econ. Polit. 6, 83–69.

Robinson, C. (2017). Tracing and explaining securitization: social mechanisms, process tracing and the securitization of irregular migration. Secur. Dialogue 48, 505–523. doi: 10.1177/0967010617721872

Sacks, D. (2023). Why is Italy withdrawing from China’s Belt and Road Initiative? Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/blog/why-italy-withdrawing-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative (accessed March 4, 2025)

Segal, A. (2016). The hacked world order: how nations fight, trade, maneuver, and manipulate in the digital age. New York: Public affairs.

Stec, G. (2021). Lithuania leaves 17+1 yet the format lives on. Available online at: https://merics.org/en/merics-briefs/171-format-diplomatic-damage-control-eu-us-cooperation (accessed May 26, 2025)

Trump Administration. (2017). National security strategy of the United States of America. Washington: Trump Administration.

Vahtla, A. (2022). Estonia, Latvia withdrawing from China's 16+1 cooperation format. Available online at: https://news.err.ee/1608682231/estonia-latvia-withdrawing-from-china-s-16-1-cooperation-format (accessed May 26, 2025)

Wæver, O. (2011). Politics, security, theory. Secur. Dialogue 42, 465–480. doi: 10.1177/0967010611418718

Wæver, O. (2015). The theory act: responsibility and exactitude as seen from securitization. Int. Relat. 29, 121–127. doi: 10.1177/0047117814526606d

Wang, T.S. (2024). After two years in office, what kind of "performance report" has Meloni presented? Available online at: https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2024–10/28/nw.D110000gmrb_20241028_2-12.htm (accessed May 22, 2025)

Keywords: Belt and Road initiative, 17+1 Mechanism, securitization, economic security, Sino–European collaboration

Citation: Liu J (2025) A comparative study of Italy’s withdrawal from the Belt and Road Initiative and the Baltic States’ withdrawal from the 17+1 Mechanism. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1714150. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1714150

Edited by:

Nikos Papadakis, University of Crete, GreeceReviewed by:

Georgia Dimari, Ecorys, United KingdomRoberto L. Barbeito, Rey Juan Carlos University, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juanping Liu, bGl1anVhbnBpbmdAbHp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Juanping Liu

Juanping Liu