Understanding consciousness could change what it means to be human

Consciousness is one of humanity’s biggest mysteries.

People have long tried to understand the connection between the mind, the brain, and the wider world—yet we still cannot explain what consciousness is or how it arises. Without that understanding, we are unable to fully grasp human experience or refine the ethical frameworks that guide medicine, law, and technology.

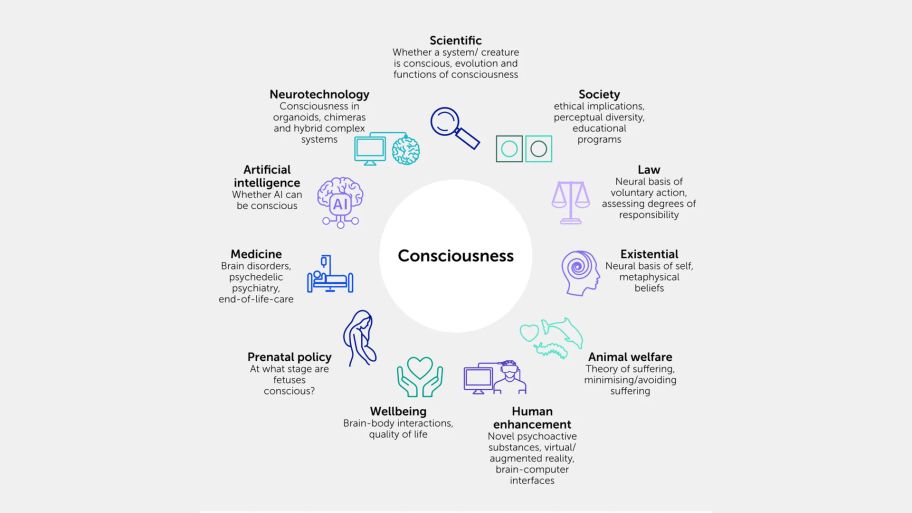

As society grapples with ethical questions about artificial intelligence (AI), animal welfare, prenatal policy, and advanced biomedical techniques, research into consciousness is more pressing than ever.

In their Frontiers in Science article, Cleeremans et al. review recent progress in consciousness research, identify ways the science can advance, and explore the implications of a deeper understanding of consciousness.

This explainer summarizes the article’s main points.

What is consciousness?

Consciousness can be defined as the state of being aware of our surroundings and of ourselves.

To some, consciousness is a biological process that one day may be detectable on a brain scan. To others, it is a form of information processing that could be used in machines. Another view is that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe, like mass or energy.

Across all these accounts, it is widely agreed that consciousness shapes the way we see ourselves, other species, technology, and even life’s meaning. Yet consciousness can be difficult to explain and study—partly because it means different things to different people.

Cleeremans et al. make three distinctions to help clarify what we mean when we discuss consciousness:

levels vs contents of consciousness: the level of consciousness is about how awake and aware someone is or is not. For example, someone in a deep sleep or a coma could be described as having a low level of consciousness. The contents of consciousness refer to what we are aware of, for example seeing a color, hearing music, or feeling hungry

perceptual awareness vs self-awareness: perceptual awareness is our experience of the external world—understanding that we are seeing a tree or hearing music instead of abstract patterns of light or sound. Self-awareness is the experience of sensing personal identity and emotion—for example, recognizing yourself in a mirror, or feeling happy

phenomenological vs functional aspects of consciousness: phenomenological aspects refer to what consciousness feels like—for example, the taste of chocolate or the pain of a headache. Functional aspects refer to what consciousness does, such as allowing us to integrate different types of information, and to plan into the future.

Why is understanding consciousness so difficult?

Researchers have developed dozens of ways to explain consciousness. Unfortunately, experimental approaches are often designed to support the theories being tested, rather than narrowing down the range of theories by falsifying or directly comparing them.

Cleeremans et al. describe four key factors that make studying consciousness especially difficult:

it raises deep philosophical questions about how experiences arise from the brain

it relies on gathering objective data about something inherently subjective

it requires theories that explain both underlying science and lived experience

it demands tests that can truly tell whether a being is conscious.

How are scientists making progress in understanding consciousness?

The field of consciousness research is evolving to take a more theory-driven approach, rather than simply mapping brain activity. Challenging each theory is helping to develop testable predictions and clarify key concepts.

Cleeremans et al. highlight four main groups of consciousness theories:

global workspace theory suggests that consciousness arises when information is made available and shared across the brain via a specialized global workspace, for use by different functions—like action and memory

higher-order theories suggest that a thought or feeling represented in some brain states only becomes conscious when there is another brain state that “points at it”, signaling that “this is what I am conscious of now”. They align with the intuition that being conscious of something means being aware of one’s own mental state

integrated information theory suggests that a system is conscious if its parts are highly connected and integrated in very specific ways defined by the theory, in line with the idea that every conscious experience is both unified and highly informative

predictive processing theory suggests that what we experience is the brain’s best guess about the world, based on predictions of what something will look or feel like, checked against sensory signals.

The field will benefit from greater collaboration across disciplines and between different groups of researchers, particularly with studies that test competing theories—so called “adversarial collaborations.” It will also be possible to perform experiments in more natural environments thanks to new technologies and methods, such as virtual reality headsets and wearable brain imaging.

What new methods are shaping the field?

Researchers have learnt a great deal from examining people with neurological disorders or injuries, using brain stimulation, and studying non-human animals. This work has identified neural signatures and behavioral markers that might indicate consciousness, as well as brain regions that contribute to awareness.

Researchers are also investigating “phenomenology”—how and why experiences feel they way they do. Studies like these combine tests such as brain scans with tests of perception. In both humans and other animals, new computational methods are increasingly being used to relate brain mechanisms to experiences.

What if we succeed in “solving” consciousness?

Progress in consciousness science is already influencing medicine, including improving the way we care for non-responsive patients, such as those in a coma, with severe brain injury, or advanced dementia. An improved understanding of the biology of awareness could also guide development of treatments for conditions such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.

A full understanding of how consciousness relates to the brain could also lead to tests that determine which entities are conscious. This would have significant ethical and societal ramifications in many areas:

medicine: better diagnostics, assessments, and care for patients

prenatal policy: identifying consciousness in fetuses would affect ethical and legal debates around pregnancy and reproductive rights

animal welfare: clarifying which animals are conscious would influence our moral and legal obligations towards them, affecting the way we conduct medical research and produce food and clothing

artificial consciousness: if consciousness can be created, potentially through AI or lab-grown brain cell cultures, it would raise immense ethical challenges. Mass-producing such systems could influence our moral and legal obligations towards them, and even AI systems that merely seem conscious raise major ethical and societal challenges

law: understanding how conscious and unconscious processes shape decision-making could challenge legal concepts like mens rea (guilty mind—the requirement to prove a person’s intent or knowledge of wrongdoing). This would make it more difficult to assign moral and criminal responsibility

neurotechnology and human enhancement: advances in brain–computer interfaces or virtual and augmented reality could expand or alter human consciousness in ways that raise ethical questions

human self-perception: understanding consciousness could reshape humanity’s view of its place in the universe, continuing a historical trend of science debunking the idea of human uniqueness.