Abstract

Progress in high-energy physics has long relied on electromagnetic calorimeters–total absorption devices used to measure the energy of electrons and photons. Recently, it has been shown that electromagnetic showers can develop more rapidly inside scintillating crystals when the incoming beam is aligned with a crystal axis within a few tenths of a degree. Building on this, we are developing and testing a novel type of calorimeter based on oriented crystals, which enables a significantly reduced depth for containing high-energy showers compared to conventional designs. We report here the full R&D path, from single-crystal studies across various materials to the construction of the first matrix of PWO crystals. The angular acceptance for shower acceleration is largely energy-independent, while the shower-length reduction becomes more pronounced at higher energies. This makes oriented-crystal calorimetry a promising solution for next-generation high-performance detectors. In addition to improving particle identification through reduced hadronic sensitivity, this technology is well-suited for forward calorimetry at colliders, fixed-target setups, and beam dumps for light dark matter searches. Furthermore, in -ray astrophysics, such compact calorimeters could enhance sensitivity above 1 GeV by increasing effective area without adding weight–ideal for space-based telescopes targeting high-energy transients and multi-messenger events.

1 Introduction

With the discovery of radioactivity and nuclear reactions, calorimeters were developed to measure the energy released in such processes. In particular, electromagnetic calorimeters (ECAL) are designed to measure the energy of particles that interact via the electromagnetic force, such as electrons (), positrons (), and photons . The energy measurement is achieved by inducing electromagnetic showers, where an incoming particle initiates a cascade of secondary electrons, positrons, and photons. At high energies, the dominant processes responsible for this cascade are pair production (PP), where a photon converts into an electron-positron pair, and bremsstrahlung, where charged particles emit hard photons when deflected by atomic nuclei.

There are two main types of ECALs: sampling and homogeneous. This manuscript focuses on the latter, made entirely of active materials like scintillating or Cherenkov crystals, noble liquids, or semiconductors, allowing for excellent energy resolution as the full particle energy is deposited in the active medium (Christian and Gianotti, 2003). Among available technologies, inorganic scintillating crystals stand out for their high light yield, compactness, and radiation hardness. Dense crystals such as (PWO), BGO, , and CsI offer precise and stable performance even in hard radiation environments, thanks to their high atomic number, structural stability, and chemical purity. As a result, they are widely adopted in precision experiments. Historically, experiments such as PHENIX at Brookhaven National Laboratory installed 412 crystals in the Muon Piston Calorimeter to reconstruct mesons for spin–asymmetry measurements in collisions (Franz, 2008). Today, CMS at CERN employs a large–scale crystal electromagnetic calorimeter (ECAL), enabling precision photon and electron measurements central to Higgs–boson studies (Chatrchyan et al., 2012). Looking ahead, PANDA at the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research is developing an electromagnetic calorimeter based on (PWO–II) crystals (Boca, 2014).

In these applications, the lattice structure and orientation of scintillating crystals are typically neglected, as the electromagnetic physics models used in calorimeter design treat the crystal medium as amorphous. However, it has been known since the 1950s that the crystal lattice can enhance both radiation emission by electrons and positrons and pair production by photons when the particle beam is aligned with crystallographic directions within a degree. These are precisely the fundamental processes underlying calorimeter operation, and the ORiEnted calOrimeter (OREO) project, presented in this manuscript, aims to fully exploit this potential. Indeed, these enhanced processes lead to an acceleration of the electromagnetic shower that can be harnessed to develop a highly compact calorimeter with reduced material budget, enhanced sensitivity, and improved resolution along the observation direction, compared to state-of-the-art systems, as detailed in the following sections.

2 Strong crystalline field

When a charged particle travels through a crystal at a small angle relative to the lattice plane or axis, successive collisions of the particles with the atoms in that plane/axis are correlated, allowing the replacement of individual atomic potentials with an average continuous planar/axial potential corresponding to strong electric fields of the order of – V/cm. At high energies, these fields are Lorentz-boosted and can exceed the Schwinger critical field ( V/cm), which is the threshold for the SF regime (Ritus, 1978; Schwinger, 1951). In the SF regime, the electrodynamics becomes non linear and the processes that mainly contribute to the development of the e.m. shower at high-energy, the PP by photons and the hard photons emission by , are significantly enhanced compared to in amorphous materials and non-aligned crystals (Baryshevsky and Tikhomirov, 1989; Baier et al., 1998; Uggerhøj, 2005; Baryshevskii and Tikhomirov, 1983; Baryshevskii and Tikhomirov, 1985). The SF condition , with being the Lorentz factor, is typically satisfied for particle energies above GeV in high- crystals. As increases, these effects become more pronounced, enhancing the electromagnetic shower development (Baier et al., 1998; Uggerhøj, 2005; Baryshevsky and Tikhomirov, 1989). This results in a shorter longitudinal extension of the shower, which is developed in fewer units of radiation length . In other words, in an oriented crystal, we observe a decrease of the effective , which is defined as the amount of matter an electron must travel to its initial energy be reduced by factor , compared to amorphous (or randomly oriented) media.

An estimate of the relative angle between the incidence particle direction and the crystallographic axis, needed for the SF regime to occur, is defined by:where is the axial (planar) potential well depth of the crystal, is the electron mass, and is the speed of light (Baryshevskii and Tikhomirov, 1985). For angles of incidence bigger than , other coherent phenomena such as coherent bremsstrahlung and coherent pair production become relevant (Diambrini palazzi, 1968; Dyson and Überall, 1955; Leonovich Ter-Mikaelian, 1972). These effects lead to an enhancement of both Bethe-Heitler bremsstrahlung and pair production processes, even if less produced compared to the SF maximum, observable up to and at energies well below the SF threshold (Andersen et al., 1983).

Since the 1980’s, this phenomenon has been explored using single-element crystals such as silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), and tungsten (W) (Uggerhøj, 2005; Kirsebom et al., 1998). In particular, studies on high-, high-density metallic materials such as iridium and tungsten have been conducted since the 1990s, aiming to develop compact photon converters and high-intensity positron sources (Kirsebom et al., 1998; Artru et al., 2005; Bandiera et al., 2022; Moore et al., 1996). For instance, the NA48 experiment at CERN incorporated an iridium-crystal photon converter with a reduced effective , if compared to an amorphous material (Fanti et al., 2007). More recently, a more than twofold increase in energy deposition has been observed for 25–100 GeV photons passing through a 1 cm thick crystal1 (Biryukov and Chesnokov, 1997), further confirming the potential of oriented crystals in enhancing electromagnetic interactions (Soldani et al., 2022) to be used as compact photon absorber for neutral beams (Cortina Gil et al., 2022; HIKE Collaboration, 2023; Fry et al., 2025).

3 Oriented scintillating crystals

Dense scintillator crystals like PWO, BGO, , and CsI are widely used in compact electromagnetic calorimeters thanks to their high atomic number, which results in a short radiation length on the order of 1 cm (Christian and Gianotti, 2003). When properly oriented, these high-Z scintillators can exhibit an enhanced development of electromagnetic showers, similar to what is observed in single-element crystals.

Among all, PWO is one of the densest crystal scintillator ( 0.89 cm (Navas et al., 2024)), and also one of the most commonly used, radiation hard, and cost-effective material to build a compact high-resolution homogeneous calorimeter, as already demonstrated for the CMS ECAL. Thanks to its high atomic number and excellent crystallographic quality, PWO is also ideal for investigating SF effects and exploring its potential for realizing ultra-compact, high-performance calorimeters. A PWO crystal indeed has a scheelite-type structure, characterized by a tetragonal lattice with lattice constants and (Bandiera et al., 2023); a scheme of PWO structure is shown in Figure 1a. When PWO is oriented along its crystallographic axis [100], the axial potential well is approximately 500 eV, corresponding to a maximal axial field strength of (EV/cm) (Bandiera et al., 2023). This orientation () corresponds to a SF threshold of about 25 GeV for , with an associated acceptance angle 0.9 mrad.

FIGURE 1

![Diagram (a) illustrates an experimental setup for detecting particles, with labeled components such as PWO and γ CAL. It also shows an atomic structure, emphasizing an electron beam’s path. Diagram (b) is a graph displaying Spectrum of the energy lost with curves for random and on-axis electrons and positrons. The x-axis is labeled "energy loss E [GeV]" and the y-axis "dN/ΔE NdE [GeV^2]".](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1659893/xml-images/fsens-06-1659893-g001.webp)

(a) Top: Experimental setup at CERN SPS H4 line, as in the experiment reported in (Bandiera et al., 2018). (a) Bottom: Orientation of the PWO crystal relative to the impinging electron beam and the view of the crystal lattice from the beam’s perspective are also shown. Adapted from (Bandiera et al., 2018). (b) Radiation energy loss resulting from the interaction of 120 GeV positron and electron beams with 4 mm PWO crystal in random (light blue and blue dots) and axial ([001]) orientation (orange and red dots). Spectra are normalized w.r.t. the total number of incident particles (N). Adapted from (Soldani et al., 2022).

In 1999, the first studies were conducted on the electromagnetic cascade initiated by 26 GeV electrons, in axially oriented PWO, showing a limited increase in energy loss of about 10 of the beam energy as compared to random orientation (Baskov et al., 1999). The authors emphasized the importance of further investigations at higher energies (hundreds of GeV to TeV), where strong field effects become increasingly relevant and align with the energy scales of current and future high-energy physics experiments. They also highlighted the need for a dedicated Monte Carlo simulation to model electromagnetic shower development in oriented crystals.

To fully demonstrate the potential of the SF regime in scintillating crystals for enhancing electromagnetic shower containment, and thus improving calorimeter performance in forward geometries, a series of experiments were conducted starting from 2017 using single-crystal samples. The first experiment in the full SF regime were carried out at the H4 beamline at the CERN Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) using electron and positron beams of 120 GeV/c impinging on a 4 mm (0.45 ) crystal (Bandiera et al., 2018). The setup of the experiment is described in Figure 1a, where S1–S2 are plastic scintillators used for triggering, while SD1–SD3 are silicon detectors forming the tracking system. The triangle indicates the bending magnet, which deflects both the primary electrons and the secondary charged particles generated by photon interactions within the PWO crystal. Finally, the -CAL denotes the electromagnetic calorimeter used to detect the emitted photons. As shown in Figure 1b: when the crystal is axially oriented (), the spectrum of the radiated energy in photons (excluding the charged secondary produced, swept away by a bending magnet positioned after the PWO sample) collected by the -CAL shows a clear enhancement of the radiation emissions in the harder part of the distribution, with a peak at 100 GeV, and a strong suppression at low energy if compared to the amorphous case (random), the latter showing a standard Bremsstrahlung spectrum. This enhanced radiative loss along the crystal axis is observed for both electron and positron beams, and results in a 5-fold decrease of the effective radiation length for primary 120 GeV (Bandiera et al., 2018).

Advanced studies were conducted to directly investigate the shower development modification. This was accomplished by measuring the energy deposited by 120 GeV electrons in various PWO samples with thicknesses up to 4.6 , corresponding to the initial stage of the shower, where particles carry the highest energy and maintain the smallest angle relative to the primary trajectory–conditions under which SF effects are maximized. The setup is essentially the same as in (Bandiera et al., 2018), as shown in Figure 1a, with the main differences being the removal of the bending magnet and SD3 detector, and the replacement of the single PWO crystal with multiple PWO samples. The deposited energy was inferred from the scintillation light collected by a matrix of SiPMs coupled to the crystal samples. A significant increase in the deposited energy was observed as the PWO crystal orientation approached axial alignment, reaching up to three times the value measured in the amorphous configuration for the 4.6 sample (Soldani et al., 2024). Moreover, an enhancement was detected even at incidence angles well beyond the critical angle mrad for , as defined in Equation 1, with measurable effects beyond 1 (Soldani et al., 2024).

The analysis results were validated using a newly developed simulation code. In particular, simulations were carried out with a modified version of the FTFP_BERT Physics List, as the standard Geant4 toolkit does not yet implement the orientational effects in crystals, while instead treating the media as amorphous. In this modified version, the differential cross-sections for bremsstrahlung and pair production processes were scaled by energy-dependent coefficients (Bandiera et al., 2018; Bandiera et al., 2019). These scaling factors were precomputed through dedicated full Monte Carlo simulations, in which the probabilities of radiation emission and pair production in the axial field of a PWO lattice were evaluated by numerically integrating the quasiclassical Baier-Katkov formula along realistic particle trajectories (Bandiera et al., 2018; Bandiera et al., 2019).

This simulation model played a central role in optimizing both the choice of scintillator material and the design of the OREO oriented calorimeter prototype. Following extensive validation, the model has been integrated into the Geant4 simulation toolkit (Geant4, 2025; Sytov et al., 2023), providing a robust and reliable framework for simulating strong field effects.

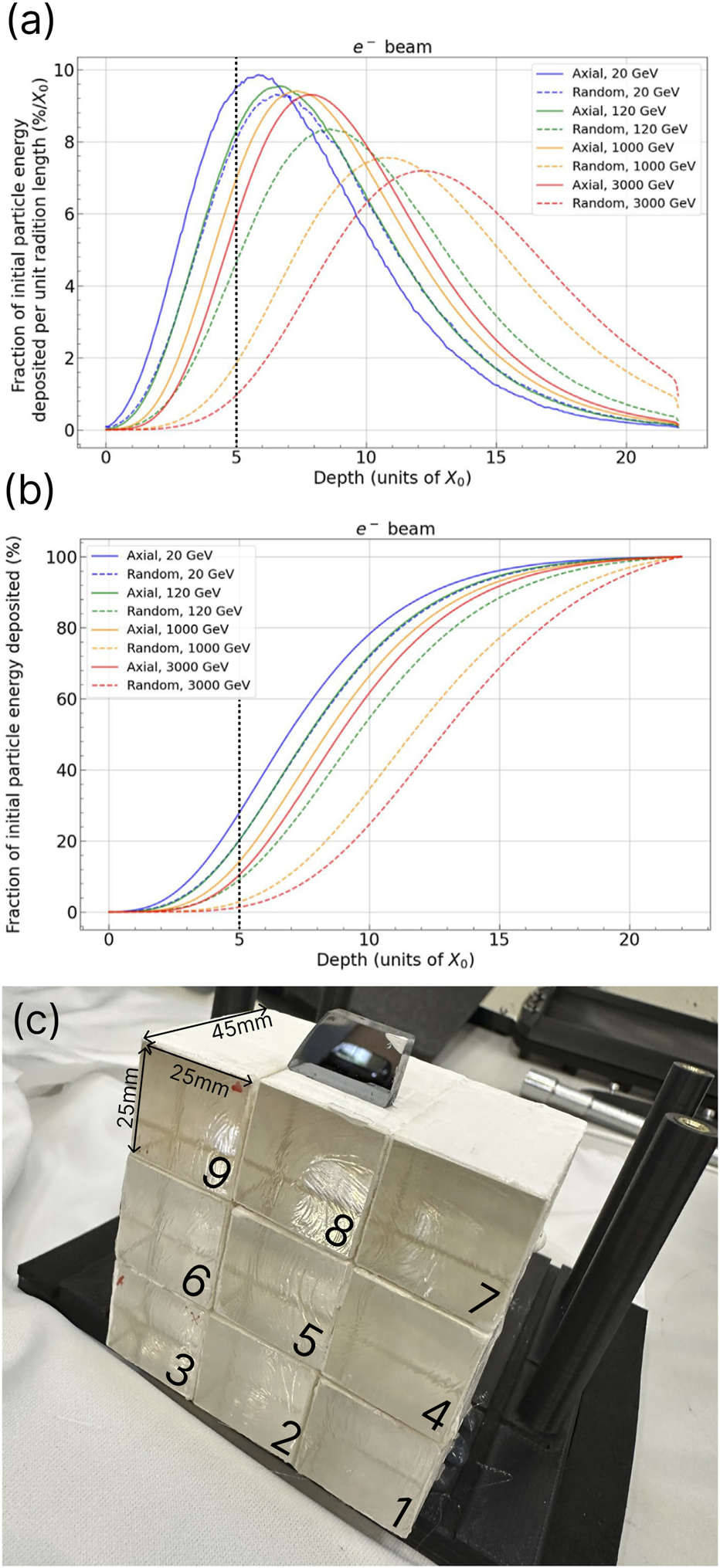

Insights into the acceleration of the shower development are provided by simulations, shown in Figure 2a, which display the fraction of energy deposited in a PWO crystal by a primary electron at different energies, as a function of crystal depth in units of nominal –i.e., the conventionally calculated value without accounting for lattice-induced effects–normalized to the primary energy. An enhancement of the deposited energy is observed in the first radiation length units when the crystal is in the axial configuration (), compared to the random orientation. This is accompanied by a clear shift of the shower maximum toward fewer units of radiation length. The effect becomes more evident as the energy of the primary particle increases (Bandiera et al., 2023): for instance, for 3 TeV electrons, the shower maximum is shifted from about 12.5 in random orientation to about 7.5 in axial orientation. Figure 2b shows the cumulative distribution of the percentage of energy deposited by the primary electron. The ratio between the energy deposition profiles in the axial and random configurations is not constant: the shower develops more rapidly in the 5–10 radiation lengths in the axial case, but this enhancement diminishes in the subsequent units. This effect is due to the fact that the secondary particles produced in the shower have lower energies, and their trajectory angles are no longer in the maximum effects acceptance angle of Equation 1. As a consequence, these particles are no longer in the SF regime, and the enhancement of the shower development is reduced.

FIGURE 2

Simulations of electromagnetic shower development initiated by primary electrons of various energies, comparing random PWO (dashed lines) and oriented (solid lines). Specifically, (a) Percentage of energy deposited per unit radiation length . (b) Cumulative energy deposition by the primary electron. In both panels, a black dotted line marks 5 , highlighting a value of particular interest for both past and upcoming experiments. Adapted from (Bandiera et al., 2023). (c) Photo of the first OREO oriented matrix on its support holder. The crystals are covered with a radiation-resistant white reflective paint. The silicon mirror on top works as a guide for the alignment of the matrix with respect to the beam. The figure is adapted from (Malagutti et al., 2024).

Studies on various scintillating materials, besides PWO crystals, were also carried out at the Mainz Microtron (MAMI) in Mainz, Germany, using an electron beam with a momentum of 855 MeV/ (Bandiera et al., 2024). The radiation emitted by the electrons interacting with axially oriented crystals, specifically , , was found to exceed that of non-oriented samples by up to a factor of three. Although the primary objective of the experiment was to investigate coherent radiation mechanisms at lower energies, such as channeling radiation and coherent bremsstrahlung (Leonovich Ter-Mikaelian, 1972), rather than to probe the SF regime, the results indicate that orientational effects–and by extension, SF effects–should be considered in the design and application of scintillating crystals.

4 Towards the first calorimeter prototype based on oriented scintillating crystals

Ultra-fast lead tungstate (PWO-UF) crystals of about were chosen by the OREO collaboration for the first prototype of the oriented calorimeter. PWO-UF is a third-generation PWO optimized for fast timing, with scintillation decay times below 1 ns, achieved by doping with yttrium and lanthanum ions to suppress slower components and improve radiation hardness (Bandiera et al., 2023; Korzhik et al., 2022). Despite a lower light yield, these crystals offer high density, compactness, and excellent radiation resistance, ideal for compact, granular, fast-response ECALs.

Nine crystals from Crytur (Ctytur, 2025) were characterized using a Panalytical High Resolution X-ray Diffractometer (HR XRD) equipped with a laser autocollimator (Malvern Panalytical, 2024). The miscut angle and mosaicity (spread of crystal plane orientations) were measured with microradian accuracy over the crystal surfaces (Malagutti et al., 2024). These measurements ensured minimal mosaicity and consistent miscut angles, critical for precise alignment and gap minimization.

Photoelastic laser conoscopy confirmed axis deviations below 100 rad, consistent with XRD results (Bandiera et al., 2023). Crystals were coated with radiation-resistant reflective paint and mounted on vacuum fixtures for assembly. A matrix formed the prototype’s first layer (Figure 2c), with crystals sized , miscut angles under 5 , and mosaicity below 300 rad.

The successful alignment of all of the crystals in the matrix is confirmed by measuring the angular deviation of each crystal from crystal-1 (as labeled in Figure 2c), with all deviations kept within 200 rad. This is well below the SF angular acceptance of 0.9 mrad, ensuring the entire layer remains within the SF regime. The full OREO prototype consists of two separate PWO-UF crystal layers: a 5 oriented layer followed by a second 11.2 non-oriented layer. The readout system of OREO comprises eighteen readout units–nine per layer, one per crystal mounted in a plastic holder with a spring-loaded mechanism that ensures stable SiPM–crystal coupling. Each unit houses four Hamamatsu Multi-Pixel Photon Counters arranged in a layout.

5 Discussion on future prospects and applications

The peculiarity of high-Z scintillating crystals of having a more compact electromagnetic shower development in the SF regime has enabled the successful realization of a prototype of OREO as an ultra-compact homogeneous electromagnetic calorimeter. This could easily lead to a less cumbersome detector with improved energy resolution, due to the decreased shower leakage.

The prototype described in the previous section will be tested at the CERN facilities with electron and positron beams in the 1–200 GeV range. The oriented matrix of (indicated by a black dotted line in Figures 2a,b) allows for investigating the initial part of shower development where the SF effects are maximal. In the upcoming experimental tests on beam, it will be possible to investigate how energy deposition varies with the orientation angle, including estimations of energy resolution, radiation length variations, and the Moliére radius.

Furthermore, since hadronic interactions are largely unaffected by SF effects, a compact oriented crystal calorimeter remains nearly transparent to hadrons, as detailed in (Monti-Guarnieri et al., 2024). This feature enhances /hadron discrimination and improves overall particle identification (PID) capabilities (see simulation studies in (Monti-Guarnieri et al., 2024)). To experimentally validate the PID performance of the OREO prototype, a dedicated test run with mixed hadron-electron beams is planned at the CERN SPS.

Once experimental validation of the first prototype is complete, the innovative approach offered by the OREO technology–enabling full electromagnetic shower containment within a significantly reduced volume compared to current detectors–has the potential to become a game-changing technique for efficient detection of electromagnetic particles. Its compactness and performance make it well-suited for immediate applications in both high-energy physics (HEP) and astroparticle physics.

In HEP, the OREO technology enables the construction of compact, high-resolution electromagnetic calorimeters, suitable for both collider and fixed-target experiments, the latter being intrinsically forward, at the energy and intensity frontiers. At colliders, the novel approach can be employed to decrease the shower leakage and improve the energy/angular resolution in the forward region, for which particles arrive directly from the interaction point with very little angular spread, as well as to increase the capability of multi-EM cluster separation. Furthermore, since photons can only be detected through their interaction with matter, the enhanced pair-production probability in the SF regime significantly increases OREO’s -detection efficiency. This makes it particularly well-suited for use as a small-angle photon veto in hadron beamlines.

Beyond traditional HEP applications, OREO allows a unique program to search for light dark matter candidates, using the missing-energy technique in fixed target experiments as the NA64 experiment at CERN (Nardi et al., 2018). For instance, if a dark photon is produced in the target, it can be identified via residual electromagnetic shower. The sensitivity of this approach is directly constrained by the total detector length, as the hypothetical dark particle produced within the calorimeter can only be detected if it survives over the entire length before decaying visibly. Therefore, a shorter detector implies higher sensitivity.

In space-borne astrophysics, adhering to strict weight and volume constraints is essential. For missions such as the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope’s Large Area Telescope (LAT) (Atwood et al., 2009), which targets high-energy (HE) and very high-energy (VHE) rays, one of the primary challenges is the limited photon flux combined with a diffuse and isotropic background. The OREO technology offers a compelling solution by allowing a significant reduction in the longitudinal depth of the electromagnetic calorimeter, while preserving the detection efficiency of conventional calorimeters, if employed in pointing strategy. This reduction enables an increase in the detector’s transverse area without increasing the total mass, thus improving photon detection statistics in the GeV regime. Furthermore, a space-borne telescope equipped with an OREO-based electromagnetic calorimeter could achieve enhanced sensitivity above 1 GeV in the pointing direction, owing to the increased pair-production yield when operated in a pointing configuration. It is important to note that such a detector would remain fully operational under standard conditions, including for off-axis or high-incidence-angle particles, and when not used in pointing mode. This versatility makes the technology well-suited for investigating unresolved sources observed by Fermi-LAT, as well as for enabling the development of lighter detectors suitable for rapid-response, fast-rotating satellites designed to capture HE/VHE transients and multi-messenger events.

Statements

Author contributions

LB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. PF: Data curation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Group members of Oriented Calorimeter Collaboration

L. Bandiera, N. Canale, F. Davì, P. Fedeli, A. Gianoli, V. Guidi, L. Malagutti, A. Mazzolari, R. Negrello, G. Paternò, M. Romagnoni, A. Saputi, S. Squerzanti, A. Sytov, Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy; V. G. Baryshevsky, V. Haurylavets, M. Korjik, A. Lobko, V. V. Tikhomirov, Institute for Nuclear Problems, Belarusian State University, Minsk, Belarus; L. Bomben, G. Lezzani, Mangiacavalli, M. Prest, G. Saibene, A. Selmi, E. Vallazza, G. Zuccalà, Universit`a degli Studi dell’Insubria, Como, Italy; L. Bomben, G. Lezzani, Mangiacavalli, M. Prest, G. Saibene, A. Selmi, E. Vallazza, G. Zuccalà, INFN Sezione di Milano Bicocca, Milan, Italy; N. Canale, F. Cescato, P. Fedeli, V. Guidi, A. Mazzolari, R. Negrello, M. Romagnoni, Dipartimento di Fisica e Scienze Della Terra, Universit`a Degli Studi di Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy; F. Davì, L. Montalto, D. Rinaldi, Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Edile e Architettura, Universit`a Politecnica Delle Marche, Ancona, Italy; De Salvador, F. Sgarbossa, D. Valzani, Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Laboratori Nazionali di Legnaro, Legnaro, Italy; De Salvador, F. Sgarbossa, D. Valzani, Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università Degli Studi di Padova, Padua, Italy; F. Longo, P. Monti Guarnieri, Universit‘a degli Studi di Trieste, Trieste, Italy; F. Longo, P. Monti Guarnieri, INFN Sezione di Trieste, Trieste, Italy; L. Montalto, M. Moulson, D. Rinaldi, M. Soldani, INFN Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati, Frascati, Italy; L. Perna, Gran Sasso Science Institute,INFN Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso, L’Aquila, Italy

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was primarily funded by INFN CSN5 through the STORM and OREO projects. We also acknowledge partial support from the INFN CSN5 Geant4-INFN initiative, as well as the CSN1 NA62 and RD-FLAVOUR projects. Additional support was provided by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN 2022Y87K7X), and by the European Commission through Horizon 2020 AIDAinnova (Grant Agreement No. 101004761) and Horizon 2020 MSCA IF Global TRILLION (Grant Agreement No. 101032975).

Acknowledgments

We thank CRYTUR, spol. s.r.o. (Turnov, Czech Republic) and Molecular Technology (MolTech) GmbH (Berlin, Germany) for supplying the crystals used in this work. We are also grateful to the CERN PS/SPS coordinators and the SPS North Area staff for their valuable support during the experimental setup phase. In particular, we are indebted to N. Charitonidis, P. Boisseau Bourgeois, S. Girod, M. Lazzaroni, and B. Rae for their assistance. We would also like to thank A. Celentano and L. Marsicano for insightful discussions on the potential applications of this work in light dark matter searches. Finally, we acknowledge fruitful discussions with E. Cavazzuti, L. Costamante, S. Cutini, M. Duranti, R. Gaitskell, S. M. Koushiappas and V. Vagelli regarding possible applications in gamma-ray astrophysics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Solely to assist with English language refinement.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^The indices in the square brackets identify crystallographic directions following Miller notation.

References

1

Andersen J. U. Bonderup E. Pantell R. H. (1983). Channeling radiation. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci.33, 453–504. 10.1146/annurev.ns.33.120183.002321

2

Artru X. Baier V. Beloborodov K. Bogdanov A. Bukin A. Burdin S. et al (2005). Summary of experimental studies, at cern, on a positron source using crystal effects. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms240 (3), 762–776. 10.1016/j.nimb.2005.04.134

3

Atwood W. B. Abdo A. A. Ackermann M. Althouse W. Anderson B. Axelsson M. et al (2009). The large area telescope on the fermi gamma-ray space telescope mission. Astrophysical J.697 (2), 1071–1102. 10.1088/0004-637x/697/2/1071

4

Baier V. N. Katkov V. M. Strakhovenko V. M. (1998). Electromagnetic processes at high energies in oriented single crystals.

5

Bandiera L. Tikhomirov V. Romagnoni M. Argiolas N. Bagli E. Ballerini G. et al (2018). Strong reduction of the effective radiation length in an axially oriented scintillator crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett.121, 021603. 10.1103/physrevlett.121.021603

6

Bandiera L. Haurylavets V. Tikhomirov V. (2019). Compact electromagnetic calorimeters based on oriented scintillator crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip.936, 124–126. 10.1016/j.nima.2018.07.085

7

Bandiera L. Bomben L. Camattari R. Cavoto G. Chaikovska I. Chehab R. et al (2022). Crystal-based pair production for a lepton collider positron source. Eur. Phys. J. C82 (8), 699. 10.1140/epjc/s10052-022-10666-6

8

Bandiera L. Baryshevsky V. G. Canale N. Carsi S. Cutini S. Davì F. et al (2023). A highly-compact and ultra-fast homogeneous electromagnetic calorimeter based on oriented lead tungstate crystals. Front. Phys.11, 1254020. 10.3389/fphy.2023.1254020

9

Bandiera L. Camattari R. Canale N. De Salvador D. Guidi V. Klag P. et al (2024). Investigation of radiation emitted by sub gev electrons in oriented scintillator crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip.1060, 169022. 10.1016/j.nima.2023.169022

10

Baryshevskii V. B. Tikhomirov V. V. (1983). Creation of transversely polarized high-energy electrons and positrons in crystals. Sov. Phys. - JETP Engl. Transl.58 (1), 7.

11

Baryshevskii V. G. Tikhomirov V. V. (1985). Pair production in a slowly varying electromagnetic field and the pair production process. Phys. Lett. A113 (6), 335–340. 10.1016/0375-9601(85)90178-1

12

Baryshevsky V. G. Tikhomirov V. V. (1989). Synchrotron type radiation processes in crystals and polarization phenomena accompanying them. Sov. Phys. Usp.32, 1013–1032. 10.1070/pu1989v032n11abeh002778

13

Baskov V. A. Bugorsky A. P. Kachanov V. A. Khablo V. A. Kim V. V. Luchkov B. I. et al (1999). Electromagnetic cascades in oriented crystals of garnet and tungstate. Phys. Lett. B456 (1), 86–89. 10.1016/s0370-2693(99)00444-x

14

Biryukov V. I. K. V. M. Chesnokov Y. A. (1997). Crystal channeling and its application at high-energy accelerators. Springer.

15

Boca G. (2014). The panda experiment: physics goals and experimental setup. EPJ Web Conf.72, 00002. 10.1051/epjconf/20147200002

16

Chatrchyan S. Khachatryan V. Sirunyan A. M. Tumasyan A. Adam W. Aguilo E. et al (2012). Observation of a new boson at a mass of 125 gev with the cms experiment at the lhc. Phys. Lett. B716 (1), 30–61. 10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.021

17

Christian W. Gianotti F. (2003). Calorimetry for particle physics. Rev. Mod. Phys.75, 1243–1286. 10.1103/revmodphys.75.1243

18

Cortina Gil E. Jerhot J. Lurkin N. Numao T. Velghe B. Wong V. W. S. et al (2022). Hike, high intensity kaon experiments at the cern sps: letter of intent. Tech. Rep. CERN-SPSC-2022-031, SPSC-I-257, SPSC-I-257. 10.48550/arXiv.2211.16586

19

Ctytur (2025). Integrated crystal based solutions. Available online at: https://www.crytur.com/.

20

Diambrini palazzi G. (1968). High-energy bremsstrahlung and electron pair production in thin crystals. Rev. Mod. Phys.40, 611–631. 10.1103/revmodphys.40.611

21

Dyson F. J. Überall H. (1955). Anisotropy of bremsstrahlung and pair production in single crystals. Phys. Rev.99, 604–605. 10.1103/physrev.99.604

22

Fanti V. Lai A. Marras D. Musa L. Nappi A. Batley R. et al (2007). The beam and detector for the na48 neutral kaon cp violation experiment at cern. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip.574 (3), 433–471. 10.1016/j.nima.2007.01.178

23

Franz A. (2008). Highlights from PHENIX - i. J. Phys. G.35, 104002. 10.1088/0954-3899/35/10/104002

24

Fry J. Goudzovski Ev. Lazzeroni C. Reddel T. Romano A. Sanders J. et al (2025). Proposal of the KOTO II experiment. Tech. Rep. 10.48550/arXiv.2501.14827

25

Geant4 (2025). Geant4. Available online at: https://geant4.web.cern.ch/.

26

HIKE Collaboration (2023). High intensity kaon experiments (hike) at the cern sps: proposal for phases 1 and 2. Tech. Rep. CERN-SPSC-2023-031, SPSC-P-368. 10.48550/arXiv.2311.08231

27

Kirsebom K. Kononets Y. Mikkelsen U. Møller S. Uggerhøj E. Worm T. et al (1998). Pair production by 5–150 gev photons in the strong crystalline fields of germanium, tungsten and iridium. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B135, 143–148. 10.1016/s0168-583x(97)00589-2

28

Korzhik M. Brinkmann K. T. Dormenev V. Follin M. Houzvicka J. Kazlou D. et al (2022). Ultrafast pwo scintillator for future high energy physics instrumentation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip.1034, 166781. 10.1016/j.nima.2022.166781

29

Leonovich Ter-Mikaelian M. (1972). High-energy electromagnetic processes in condensed media. Number 29. John Wiley and Sons.

30

Malagutti L. Selmi A. Bandiera L. Baryshevsky V. Bomben L. Canale N. et al (2024). High-precision alignment techniques for realizing an ultracompact electromagnetic calorimeters using oriented high-z scintillator crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip.1069, 169869. 10.1016/j.nima.2024.169869

31

Malvern Panalytical (2024). Panalytical, x-ray diffractometer. Available online at: https://www.malvernpanalytical.com.

32

Monti-Guarnieri P. Bandiera L. Canale N. Carsi S. De Salvador D. Guidi V. et al (2024). Particle identification capability of a homogeneous calorimeter composed of oriented crystals. JINST19 (10), P10014. 10.1088/1748-0221/19/10/p10014

33

Moore R. Parker M. A. Baurichter A. Kirsebom K. Medenwaldt R. Mikkelsen U. et al (1996). Measurement of pair-production by high energy photons in an aligned tungsten crystal. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms119 (1), 149–155. 10.1016/0168-583x(96)00347-3

34

Nardi E. Carvajal C. D. R. Ghoshal A. Meloni D. Raggi M. (2018). Resonant production of dark photons in positron beam dump experiments. Phys. Rev. D.97, 095004. 10.1103/physrevd.97.095004

35

Navas S. Amsler C. Gutsche T. Hanhart C. Hernández-Rey J. J. Lourenço C. et al (2024). Review of particle physics. Phys. Rev. D.110 (3), 030001. 10.1103/PhysRevD.110.030001

36

Ritus V. I. (1978). Method of eigenfunctions and mass operator in quantum electrodynamics of a constant field. Sov. Phys. JETP48, 788.

37

Schwinger J. (1951). On gauge invariance and vacuum polarization. Phys. Rev.82, 664–679. 10.1103/physrev.82.664

38

Soldani M. Bandiera L. Bomben L. Brizzolari C. Camattari R. De Salvador D. et al (2024). Acceleration of electromagnetic shower development and enhancement of light yield in oriented scintillating crystals. arXiv:2404.12016398. 10.22323/1.398.0853

39

Soldani M. Monti-Guarnieri P. Selmi A. Argiolas N. Bomben L. Brizzolari C. et al (2022). Enhanced electromagnetic radiation in oriented scintillating crystals at the 100-mev and sub-gev scales. Proceeding Sci. 10.22323/1.398.0853

40

Sytov A. Bandiera L. Cho K. Cirrone G. A. P. Guatelli S. Haurylavets V. et al (2023). Geant4 simulation model of electromagnetic processes in oriented crystals for accelerator physics. J. Korean Phys. Soc.83, 132–139. 10.1007/s40042-023-00834-6

41

Uggerhøj U. I. (2005). The interaction of relativistic particles with strong crystalline fields. Rev. Mod. Phys.77, 1131–1171. 10.1103/revmodphys.77.1131

Summary

Keywords

crystals, electromagnetic calorimeter, inorganic scintillator, strong field, high-energy physics

Citation

Bandiera L, Fedeli P and the Oriented Calorimeter Collaboration (2025) High-performance electromagnetic calorimeter with oriented crystals to open new pathways in particle and astroparticle physics. Front. Sens. 6:1659893. doi: 10.3389/fsens.2025.1659893

Received

04 July 2025

Revised

23 October 2025

Accepted

05 November 2025

Published

03 December 2025

Volume

6 - 2025

Edited by

Alberto Quaranta, University of Trento, Italy

Reviewed by

Ivica Friščić, University of Zagreb Faculty of Science, Croatia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Bandiera, Fedeli and the Oriented Calorimeter Collaboration.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: L. Bandiera, laura.bandiera@fe.infn.it; P. Fedeli, pierluigi.fedeli@fe.infn.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.