Abstract

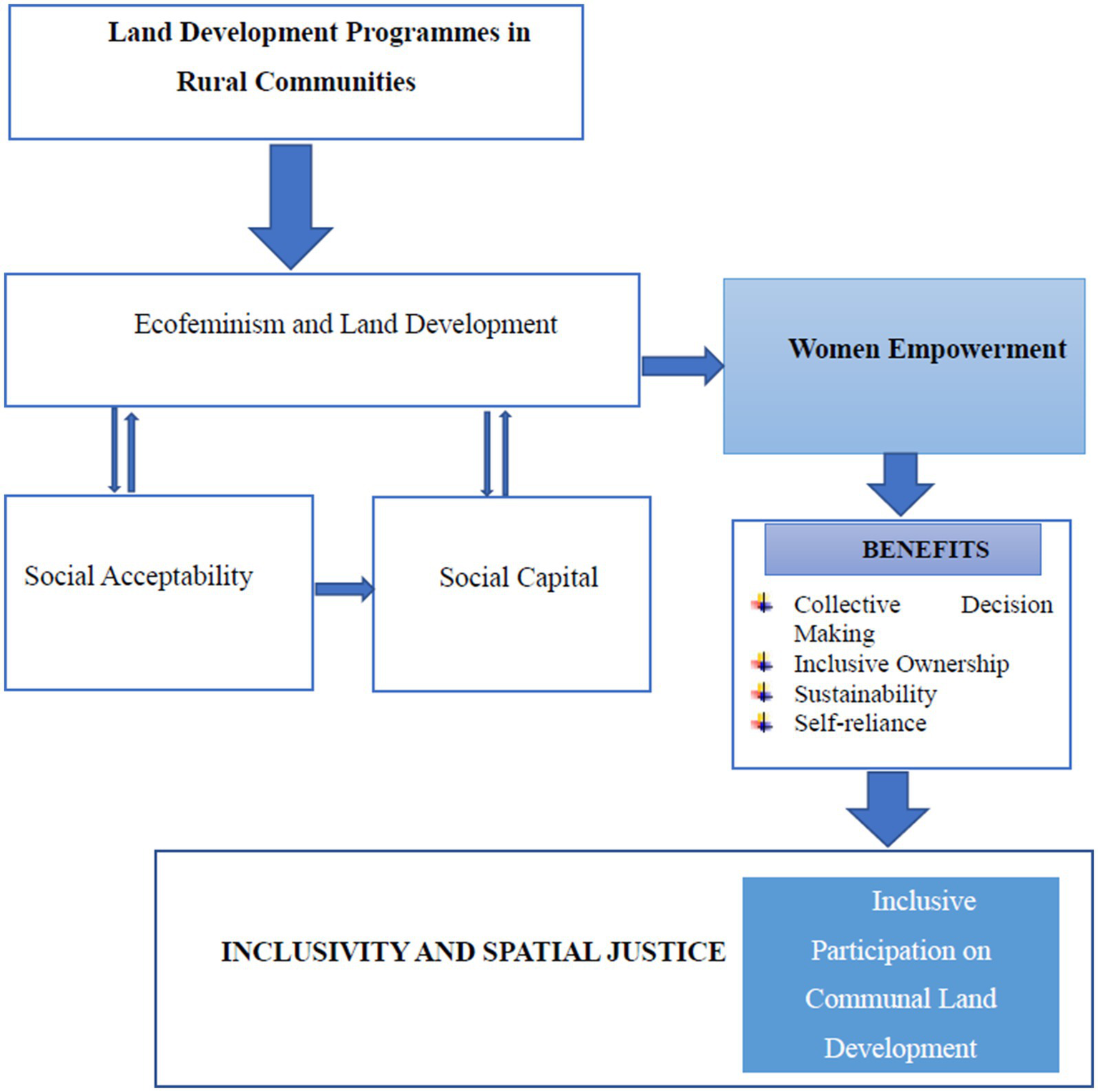

Participatory community development is considered as one of the important mechanisms of governance in ensuring inclusive and people centered development in emerging economies around the world. Remarkably, community participation has been promoted because of the associated perceived benefits such as collective decision making, ownership of community projects and sustainability of community initiatives. Despite all these associated benefits, there is an increasing concern that, in practice, community participation in relation to land development initiatives turned to be biased against and be exclusive of women. Against this backdrop, the conceptual study explores the prospects for women increased and meaningful participation in land development initiatives amid the patriarchal structures and barriers characterizing most of the societies in developing countries. Through the proposed conceptual framework, this study argues that to achieve inclusive participation in land development initiatives in communities, the agendas of women empowerment should be accompanied with ecofeminism, social capital and social acceptability principles as drivers of the transformation into the manifestation of inclusive participatory in relation to land development. The proposed conceptual framework together with the recommendations thereof in this study shed new insight to understand that, unless policies and programs of women empowerment on land development are synchronized with ecofeminist, social acceptability and social capital values, the realization of inclusive participation in communal land development in emerging economies will remain impossible.

1 Introduction and background

Communal land development is an important area of focus for both developed and developing countries as land is an important and invaluable resource for social and economic development. As defined by in the literature, communal or customary land tenure is a system that is used by mostly rural African people to organize, distribute, and own land (Branson, 2016; Winkler, 2019) for different developmental purposes. Remarkably, in rural communities people still use customary laws to control the use and administration of land (Branson, 2016), as well as the transfer of land rights (Wily, 2012). Of particular concern is that the ripple effects of the customary laws on land use and ownership often result in the exclusion of women’s participation in community development projects (Mishra and Sam, 2016) relating to communal land development. According to Cornwall (2003), women’s participation and involvement in communal land development projects is very limited and still a serious development issue in many developing countries. In the developing South region including Africa, the plight of women in terms of limited access to land has extensively been researched in several countries in the African region. This includes countries such as Madagascar, Ethiopia, and Sierra Leone (Jacoby and Minten, 2007; Bezabih and Holden, 2010; Bezu and Holden, 2014).

Though, by nature, women are perceived to be caring and having a loving attitude for the environment (Avantika, 2017), the dominant culture of patriarchy in developing societies continues to subordinate the role and meaningful participation of women in communal land development initiatives and programmes (Edström, 2014). To this extent, several policies and programs for women’s empowerment on land development remains ineffective because the societal environment and normative conditions wherein these policies are executed remain untransformed for embracing the inclusive and participatory community development orthodoxy.

Against this backdrop, this conceptual paper explores, from the feminist philosophical perspective, how inclusive participation in communal land development, as a mean to redressing the spatial injustices embedded in the primitive and patriarchal societal norms could be realized. In this paper, a conceptual framework is proposed to forge and elucidate the women empowerment outcomes and or benefits that could merge when synchronizing the tripartite of ecofeminism, social capital, and social acceptability values as the drivers towards the realization of inclusive participation in communal land development.

This research is a desktop study, and it used a systematic review of secondary data focusing on women’s participation and communal land development. We conducted a systematic review of case studies reporting on the participation of women in land issues in both developed and developing countries. According to De Jong et al. (2021), a systematic review is a preferable method when reviewing and reporting on secondary information. This paper used the thematic analysis tool to analyze documents and articles reviewed that align with the main topic. In thematic analysis, themes were formulated that focused on Women’s participation in Communal Land development, and women’s participation in communal land at the Mpumalanga province. The final step was interpreting and discussing secondary data in accordance with the formulated themes and presenting the findings to draw a conclusion.

1.1 Conceptual and theoretical framework

To advance the feminist argument, this conceptual study is underpinned on and guided by the conceptual and theoretical parameters of ecofeminism; social capital; and social acceptability.

1.1.1 Ecofeminism

The Ecofeminism philosophy looks closely to the relationship that women have with nature as it attempts to outlying new cultural horizons while addressing the environmental issues, patriarchy, sexism, class, gender and androcentrism (Puleo, 2017). This philosophical lens asserts that there are different factors such as patriarchal structures of power and capitalism which cause the oppression of women in their natural environment (Oktarina and Yulianti, 2022). Gender and environmental relations have valuable ramifications regarding the understanding of nature between men and women, the management and distribution of resources and responsibilities and the day-to-day life and well-being of people even today (Avantika, 2017). Likewise, women are seen as mother nature due to their responsibilities of producing lives and give food and protection to the living beings (Öztürk, 2020) to their families and communities. The ecofeminism advocates that women should be appreciated because they give priority to protection of and improving the capacity of nature, maintaining farming lands, and caring for nature and environment’s future (Avantika, 2017). Therefore, the aim of ecofeminism is to dismantle the gender disparities between men and women and liberate women from the male-dominate system (Öztürk, 2020) to forge inclusive participation of women in land related development initiatives. Dismantling these gender disparities also requires the establishing of strong social capital in rural communities.

1.1.2 Social capital

In the context of the patriarchal societal norms and customs that lead to the limited participation of women in communal land development, social capital can overcome the vertical barriers that make it difficult for individuals and groups with unequal social status or power to work together (Rowe, 2016) in their communities. The availability of social capital in communities can have positive outcomes in many ways towards the formation of new social ties and relationships to expand networks and to provide a broader set of new leaders with fresh ideas and information (Phillips and Pittman, 2014). In the same vein, Fabová and Janáková (2015) maintain that social capital is an intangible asset that allows people to share deep knowledge and develop winning strategies based on shared trust, norms, and mutual respect. In addition, the existence of a social network allows community members especially women to trust one another to solve existing problems. According to a study that was done by Mozumdar et al. (2017) which focused on the relevance of social capital in women’s business performance in Bangladesh, shared several positive outcomes that came from the social network of women towards their business performance. Moreover, social capital could increase the existence of informal safety nets amongst households to reduce risk and vulnerability (Nabil and Abd Eldayem, 2015). In this regard, Silvey and Elmhirst (2003) state that, as women in rural areas are usually excluded from participation in male-dominated social networks, women turned to be exposed to social shocks and be vulnerable to community risks. In relation to communal land development, Nabil and Abd Eldayem (2015) also indicate that the outcome of social capital is the reduction of information imperfections and enforcement of mechanisms that increase outputs, access to land and capital for all. Equally, amid the prevailing unequal social status and power between men and women, there is also a need for social acceptability values for building mutual trust and inclusion to see each other as an equal party in the development of communal land.

1.1.3 Social acceptability

The social acceptance conceptual framework includes features such as wanting to have a positive social contact with others; wanting a stable framework that guides the connections that individuals have with each other; and the behaviors and attitudes that influence tolerance for others (Leary, 2010: DeWall and Bushman, 2011). The relevance of this concept in this paper is its focus on the attitude, norms, and behavior which influence the acceptance of women and their participation in community development projects, in relation to land development. In essence, social acceptability is focusing on destigmatization and fighting the social rejection of women and injustices that affect women in low-income households (Kabeer, 2011), particularly in rural communities where the domination of patriarchal societal culture and norms continue to subordinate the role and participation of women in communal land development (Edström, 2014). In most of these communities, the social acceptability of women and their participation in social and economic development is highly influenced by kinship and relationship systems that is dominant in most rural areas. As observed by Nelson (1996), for women to have identities and be accepted in societies, they should belong in marriage institutions and construct their identities around marriage and family. As a result, there have been empowerment programmes that were introduced in different African countries to empower women to be socially accepted and to allow them to participate in their development (Habibov et al., 2017; Samuels and Ghimire, 2018; Samuels et al., 2018; Harper and Marcus, 2018). Equally, the drive for advocating the social acceptability norms should be mainstreamed in the patriarchy society to enable a mutual, inclusive, and meaningful participation for women in communal development projects. Eventually, the present conceptual framework in the following section illustrates how inclusive participation in communal land development, as a means towards redressing the spatial injustices embedded in the primitive and patriarchal societal norms, could be realized.

2 Towards inclusive participatory in land communal development for spatial justice

According to De Beer and Swanepoel (1998), in communities where popular participation or empowerment takes place, the emphasis is on mobilizing community knowledge and resources, community-led initiatives and decision-making, and attaining self-reliance. Equally, the proposed conceptual framework for inclusive participation in communal land development for spatial justice make the following proposition as direct benefits that could emanate from a feminist focused empowerment program of action: Collective decision making, inclusive ownership, self-reliance, and sustainability.

2.1 Collective decision making

Community development is based on the idea that all people are important and should have a voice in community decision-making, have the potential to contribute and share resources, and have a responsibility for community action and outcomes. However, as attested by Meaza (2009), collective decision-making in communities has been historically threatened by structural barriers, unequal socio-economic opportunities, and social disparities. In the context that individuals are expected to not work in isolation (De Liddo and Concilio, 2017), the social capital values should be seen as an intangible asset that could allow people to share deep knowledge and develop winning strategies based on shared trust, norms, and mutual respect (Fabová and Janáková, 2015). Inclusive participation of community members allows them to make informed decisions which will show collective intelligence, creativity, and innovation (Schuler, 2010). The involvement of community members in decision-making allows the formulation of need-specific projects to address issues of communities. Therefore, women in their ecofeminism poster as mothers (Öztürk, 2020) are to take greater responsibility to the decision making in the management and distribution of the natural resources such as land for the day-to-day life and well-being of people (Avantika, 2017) in their respective communities. Considering that education has been associated with increase ability of women to influence decision-making at households’ level which positively increase their participation in development (Habibov et al., 2017), women should be empowered to make informed decisions which will show collective intelligence, creativity, and innovation (Schuler, 2010) on communal land development.

2.2 Inclusive sense of ownership

A sense of ownership in community development is described as a concept through which to assess whose voice is heard, who has influence over decisions, and who is affected by the process and outcome (Lachapelle, 2008). With the prevalence of Indigenous culture based on patriarchal family structure and discriminative societal norms (UN Human Rights, 2013; Njoh and Ananga, 2016), women’s voice and influences are systematically eliminated in the processes of communal land development. One of the underpinning values and beliefs of community development is that ownership of the process and commitment for action is created when all people interact and trust each other to forge a strategic community development plan (Phillips and Pittman, 2014). Against this background, the issue of strong social capital, which bonds the community members together, becomes the prerequisites for community development, particularly in relation to land development initiatives where the voice of women is hardly heard. Considering that sense of ownership is related to who is affected by the process of making decisions (Lachapelle, 2008), women, from their mother nature responsibilities of producing lives, give food and protection to the living beings (Öztürk, 2020) are directly affected by the decision making on land development. As such, women should be socially accepted to actively contribute and participate to community development efforts (Lachapelle, 2008) to stimulate their sense of ownership (Phillips and Pittman, 2014) over the communal development processes and benefits thereof. Importantly, the sense of ownership in communal projects is meant to promote sustainable outcomes and empower local communities to develop programmes and projects that specifically addresses the needs of the people (Tumusiime and Cohen, 2017; Figure 1).

Figure 1

Conceptual framework for inclusive participation in communal land development. Source: Authors’ invention.

2.3 Sustainability

According to Phillips and Pittman (2014), one prominent approach within sustainability planning is to emphasize and prioritize interconnections between community development issues such as land use, transportation, housing, economic development, environmental protection, and social equity as they are all related to each other. To achieve inclusivity and spatial justice, the traditional and problematic planning approach of treating these issues in isolation (Phillips and Pittman, 2014) should be redressed. Drawing from the ecofeminism philosophy which looks closely at the relationship that women have with nature as it attempts to outlying new cultural horizons while addressing the environment (Puleo, 2017), women’s active participation in communal land development should be seen as one of the key drivers towards the realization of sustainability in communities. Women’s participation can lead to the sustainability of development initiatives through community motivation. Given their closeness to and caring of nature, women have the potential to initiate and propose sustainable community development projects. For example, restoring a stream or riverfront that create an attractive new amenity for a community, as well as help to support nearby businesses, creating new civic gathering spaces, and bringing people together for stewardship activities and celebratory events (Phillips and Pittman, 2014). For women, working with these communal resources is a way to build community pride, identity, and a sense of self-reliance.

2.4 Self-reliance

As asserted by Weber and Carter (2003) in Lachapelle (2008, p. 56), “trust can be understood by examining relationships between individuals since trust is built and based upon repeated interactions and fulfillment of expectations leading in turn to an ability to act in confidence, with reliance and faith on the individual’s integrity or character.” Social capital therefore becomes the connection that links individuals to bond with and trust in each other (Rowe, 2016) while enabling leadership and self-reliant performances when working on community development initiatives. In a study conducted by Schaumberg and Flynn (2017), which aimed at evaluating the relationships between self-reliance and leadership, it was revealed that self-reliant female leaders were evaluated as better leaders than self-reliant male leaders. The authors further maintains that the female advantage in the relationship between self-reliance and leadership evaluations emerges because self-reliant female leaders are seen as more communal than self-reliant male leaders are. Therefore, in accordance with the ecofeminism philosophy, women should play a leading role in the management and distribution of communal land resources and responsibilities (Avantika, 2017).

3 Case studies demonstrating inclusive participation in land development

Inclusive participation has demonstrated positive impacts on the development of communal land. Kırmızı and Karaman (2021) argue that involving both men and women in collective land-use planning enhances the resilience and quality of the resulting plans. Moreover, integrating stakeholders with both shared and divergent interests into the decision-making process promotes broader engagement and strengthens participation in land-use planning. Similarly, a case study by Abolhasani et al. (2022) in Tehran’s Municipal Region 22 found a strong correlation between collective decision-making and improved urban land use outcomes. Their findings suggest that collaborative planning, involving a diverse range of actors, produces more effective and sustainable land development strategies compared to non-collaborative approaches. Additionally, the inclusion of multiple genders in decision-making processes helps to minimize conflicts and ensures that land-use policies reflect the needs of all citizens equitably.

A recent case study by He and Huang (2024) examining the role of social capital in influencing local farm households and land-use policies within China’s rural industrial context revealed that social capital plays a significant role in advancing land development. Their findings indicate that farmers’ social capital facilitates agricultural land transfers by providing access to critical information and strategic partnerships, thereby enhancing trading opportunities and market access. Furthermore, farmers benefit from improved land-use policies are endorsed by local governments (He and Huang, 2024). Similarly, Chen et al. (2023), using data from 1,017 farms in Hubei Province, found that strong social networks and social trust positively affect household-level land development. The presence of social capital and inclusive participation within communities promotes marketization, which in turn enables both male and female farmers to compete fairly and reduces regulatory barriers that hinder agricultural activities. Overall, inclusive participation, supported by decentralized decision-making and the collective social capital of community members, contributes positively to communal land development.

4 Research findings

The findings of the study have revealed that there is a lack of women’s participation in communal land development. Reviewed literature has revealed that there is an existing gender gap in access, usage, and occupation of communal land (Poudyal, 2009; Edström, 2014; Catacutan and Naz, 2015; Opoku et al., 2025). To achieve sustainable and equitable development, there should be equal participation of men and women in communal land development. On the other hand, women are perceived to play a crucial role in the development of urban and rural areas. Women are seen as key role players in helping communities achieve food security and income generation through the usage of communal land (Etefa, 2020). However, Kiptot and Franzel (2012) revealed through the usage of feminist theories that women’s participation in land usage and management is highly shaped by gender roles and inequalities. Furthermore, women are often negatively affected by the gender inequalities that hinder their participation in land development (Opoku et al., 2025).

The findings of the study also revealed that women tend to be more involved in land activities as compared to their male counterparts. The statistical evidence has shown that that 80% of women in sub-Saharan Africa are engaging in agricultural-related activities that require access to land (Etefa, 2020). Furthermore, globally, 85% of women engage with the land through land weeding, 60% of women do harvesting, 50% engage in planting and 30% of women engage in plowing (Etefa, 2020). These statistical data show the importance of women in accessing land and ensuring that they participate in communal land development. As much as women are involved in land activities in different countries, their participation in decision-making processes that relate to land is lacking. Furthermore, only 12.8% of women have access to operational assets such as land reflecting the gender disparity in land tenure ownership in agriculture (n.d). In patriarchal societies, land inheritance is carried from fathers to husbands and not to women. Women are not allowed to inherit land or be active managers of communal land for development (Bahrami-Rad, 2021). Women are excluded from participating in the inheritance of land in rural areas within sub-Saharan Africa.

5 Recommendations and implications

This section of the paper will cover the recommendations and implications for policy and practice.

5.1 Implications for policy

This research used the ecofeminism approach as a theoretical framework to describe the relationship that women have with the natural environment. According to Husein et al. (2021) ecofeminism as a theoretical underpinning shows the marginalization of women in different development programmes. Different women of ethnic minorities are marginalized in different parts of the world and have limited access to resources such as the land (Husein et al., 2021). There are various inequalities and injustices that women have experienced which affect their participation and empowerment. According to Oktarina and Yulianti (2022) the combination of cultural, political, economic, and social factors has impacted the lives of women and their participation in their own development. Furthermore, the authors stated that women’s empowerment and participation in development is important to improve the quality of life for women in rural areas (Oktarina and Yulianti, 2022). The paper has argued that women should participate in communal land development for inclusivity. Ecofeminism also covers different factors such as patriarchal structures of power and capitalism in the degradation of the environment and the oppression of women. According to Ghasemi et al. (2021) for sustainability in the environment and protection of natural resources, there should be an increase involvement of women in economic and political roles in all spheres of society.

5.2 Implication for practice

The implication for practice is aligns with empirical evidence regarding the participation of women in communal land development in developing countries. When looking at Kenya as a developing country that is situated in Africa, the realization is that there are several international and national policies that address gender equality and empowerment. However, the participation of women in communal land is limited (Mwambi et al., 2021). Collected evidence from people working in a communal land that produces, and processes dairy products revealed that women are underrepresented in that participating sector (Katothya, 2017). Men are usually the head of operations in several sectors and women only benefit by being married to their male counterparts (Mwambi et al., 2021). When looking at women’s participation in communal land in Rwanda, it has been noted that it is one of the countries that is progressive in advocating for women’s rights in regard to land rights and acquisition for gender equality (Djurfeldt, 2020). However, the policies in Rwanda protect and give land to women that are within marital structures. The policies do not support the participation of widows or single women in land ownership (Djurfeldt, 2020).

The implication for practice can be applied in the Mpumalanga Province, considering that in this province, the agriculture sector contributes significantly to the country’s economy. The province prioritizes the empowerment of the youth and women to be involved in land-based projects (Mpumalanga Provincial Government, 2011). The provincial department has a program such as the Masibuyele Emasimini program which aims to facilitate the participation of people in land usage and production (Mpumalanga Provincial Government, 2011). As much as the provincial government promotes the participation of women in communal land development, Ngomane and Sebola (2022) argued that in the Mpumalanga province, there is still limited participation of women in land development. Furthermore, Maduane (2022) revealed that 70% of commercial farmers are males while 30% are females in Mpumalanga. This show a huge gap between men and women who are working within the agriculture sector. There are different factors that has been attributed to the lack of women’s participation in communal land development within the Mpumalanga province. Maduane (2022) mentioned operational challenges, financial challenges, patriarchal challenges and, males’ inheritance of land as some of the factors that negatively affect the participation of women in communal land development. There should be adequate involvement of women within the province to achieve Inclusive Participation in Communal Land Development.

5.3 The following recommendations are made based on the discussion of this conceptual paper

Social capital can lead to the achievement of positive outcomes in communities. According to Phillips and Pittman (2014) the availability of social capital in communities leads to the formation of different relationships that provide ideas and social networks. The existence of social capital between men and women in communities can lead to an exchange of new ideas and information for developments in communal land. Access to land has been seen as an individual and collective human right in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasant and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP) (Pacheco Rodriguez and Rosales Lozada, 2020). Furthermore, women’s rights to land should be recognized in several declarations to ensure their protection and equal access to land. Men and women should have equal access to communal land for their development and empowerment.

It is recommended that the social acceptability of women in land issues should be promoted. Too often, women’s equal right to land is not recognized in different countries and different legislatives fail to explicitly grant women equal tenure rights and allocation of communal land (Claeys and Martignoni, 2021; Claeys et al., 2022). Furthermore, the patriarchal societal culture and norms in rural communities to surpass the participation of women in communal land development (Edström, 2014). Therefore, women need to be socially accepted by communities so that they can have access to and ownership to communal land. Different legislatives in different countries should explicitly state the conditions in which women can have access and ownership towards land. Policies should consider the relationship that women are perceived to have with the natural environment in accordance with the Ecofeminism framework.

6 Conclusion

This conceptual paper has articulated and advanced a feminist posture as the necessary intervention to transform the patriarchal societal norms rooted in most of the rural communities in developing South countries. The paper has revealed that access to communal land is increasingly becoming difficult due to several factors such as droughts, degradation, population growth, and infrastructure development that is occurring in people’s land (Akall, 2021). In rural areas, women may have access to communal land for food and fuel. However, their participation in communal land development is limited. Women are not considered in decision-making processes that involve land usage and development (Claeys and Martignoni, 2021). This study argues that, by embracing the philosophical principles as echoed in the ecofeminism, social capital, and social acceptance theoretical frameworks, new cultural horizons and norms could emerge to transform the patriarchal structures and barriers—prevailing in most of the societies in developing South countries such as in Africa.

The conceptual paper revealed that there are perceived benefits when there is inclusive participation in communal land development. The perceived benefits discussed in the paper are collective decision-making, inclusive ownership, self-reliance, and sustainability. To achieve sustainable and equitable development, there should be equal participation of men and women in communal land development. Both men and women play a crucial role in land development. It is key responsibility of both genders to achieve food security and income generation in both developed and developing countries. Therefore, there should be inclusive participation in communal land development. This conceptual paper further maintains that, unless policies and programs of women empowerment on land-related development projects are synchronized with new cultural horizons that are informed by a feminist posture, the realization of the inclusivity and spatial justice goals will not be attained. The recommendations of the research are based on ensuring social acceptability and social capital for communities for inclusive participation in communal land development. Further empirical research is needed to focus on how feminist cultural norms could be influenced in societies in different parts of the World.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

TL: Writing – original draft. HZ: Writing – original draft. TS: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The University of Mpumalanga has financially support the publication of the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. This article benefited from the use of Grammarly (Version 1.216.0, based on generative AI language models) to correct spelling and grammatical errors. The tool was used to improve the readability of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abolhasani S. Taleai M. Lakes T. (2022). A collective decision-making framework for simulating urban land-use planning: an application of game theory with event-driven actors. Comput. Environ. Urban. Syst.94:101795. doi: 10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2022.101795

2

Akall G. (2021). Effects of development interventions on pastoral livelihoods in Turkana County, Kenya. Pastoralism11, 1–23. doi: 10.1186/s13570-021-00197-2

3

Avantika B. (2017). Achieving sustainable development through ecofeminism. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3350209 (Accessed November 11, 2017).

4

Bahrami-Rad D. (2021). Keeping it in the family: female inheritance, inmarriage, and the status of women. J. Dev. Econ.153, 102–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102714

5

Bezabih M. Holden S. (2010). The role of land certification in reducing gender gaps in productivity in rural Ethiopia. Environment for Development Discussion Paper-Resources for the Future (RFF), 10–23.

6

Bezu S. Holden S. (2014). Demand for second-stage land certification in Ethiopia: evidence from household panel data. Land Use Policy41, 193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.05.013

7

Branson N. (2016). Land, law and traditional leadership in South Africa. Africa Research Institute. (June, 2016). Available online at: https://www.africanresearchinstitute.org/pdf (Accessed June, 2016).

8

Catacutan D. Naz F. (2015). Gender roles, decision-making and challenges to agroforestry adoption in Northwest Vietnam. Int. Forestry Rev.17, 22–32. doi: 10.1505/146554815816086381

9

Chen Y. Qin Y. Zhu Q. (2023). Study on the impact of social capital on agricultural land transfer decision: based on 1017 questionnaires in Hubei Province. Land12, 1–22. doi: 10.3390/land12040861

10

Claeys P. Lemke S. Camacho J. (2022). Women's communal land rights. Front. Sustain. Food Syst.6, 1–3. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.877545

11

Claeys P. Martignoni J. B. (2021). Women are peasants too. Gender equality and the UN declaration on the rights of peasants. CAWR policy brief. Available online at: https://www.coventry.ac.uk/globalassets/media/global/08-new-research-section/cawr/cawr-policy-briefs/womenare-peasants-too-policy-brief---14-12-21.pdf (Accessed April 09, 2025).

12

Cornwall A. (2003). Whose voices? Whose choices? Reflections on gender and participatory development. World Dev.31, 1325–1342. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00086-X

13

De Beer F. Swanepoel H. (1998). Community development and beyond: Issues, structures and procedures. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

14

De Jong L. Bruin S. Knoop J. Van Vliet J. (2021). Understanding land-use change conflict: a systematic review of case studies. J. Land Use Sci.16, 223–239. doi: 10.1080/1747423X.2021.1933226

15

De Liddo A. Concilio G. (2017). Making decision in open communities: collective actions in the public realm. Group Decis. Negot.26, 847–856. doi: 10.1007/s10726-017-9543-9

16

DeWall C. N. Bushman B. J. (2011). Social acceptance and rejection: the sweet and the bitter. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci.20, 256–260. doi: 10.1177/0963721411417545

17

Djurfeldt A. A. (2020). Gendered land rights, legal reform and social norms in the context of land fragmentation-a review of the literature for Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. Land Use Policy90, 104–305. doi: 10.1016/j.landuse.pol.2019.104305

18

Edström J. (2014). The male order development encounter. IDS Bull.45, 111–123. doi: 10.1111/1759-5436.12076

19

Etefa D. F. (2020). Exploration of contributions of women in rural development and determinant factors influencing their participation, the case of agricultural cooperatives in Ethiopia

20

Fabová Ľ. Janáková H. (2015). Impact of the business environment on development of innovation in Slovak Republic. Proc. Econ. Finan.34, 66–72. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01602-0

21

Ghasemi M. Badsar M. Falahati L. Karamidehkordi E. (2021). The mediation effect of rural women empowerment between social factors and environment conservation (combination of empowerment and ecofeminist theories). Environ. Dev. Sustain.1–23. doi: 10.1007/s10668-021-01237-y

22

Habibov N. Barrett B. J. Chernyak E. (2017). Understanding women's empowerment and its determinants in post-communist countries: results of Azerbaijan National Survey. Women's Stud. Int. Forum62, 125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2017.05.002

23

Harper C. Marcus R. (2018). “What can a focus on gender norms contribute to girls’ empowerment?” in Empowering adolescent girls in developing countries (London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group). pp. 22–40.

24

He L. Huang J. (2024). Social capital, government guidance and contract choice in agricultural land transfer. PLoS One19, 1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0303392

25

Husein S. Herdiansyah H. Putri L. G. (2021). An ecofeminism perspective: a gendered approach in reducing poverty by implementing sustainable development practices in Indonesia. J. Int. Womens Stud.22, 210–228.

26

Jacoby H. G. Minten B. (2007). Is land titling in sub-Saharan Africa cost-effective? Evidence from Madagascar. World Bank Econ. Rev.21, 461–485. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhm011

27

Kabeer N. (2011). Between affiliation and autonomy: navigating pathways of women's empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Dev. Chang.42, 499–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01703.x

28

Katothya G. (2017). Gender assessment of dairy value chains: evidence from Kenya (925109621x). Available online at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/f6aa894d-2d70-47fa-8f30-6d30ae353011/content (Accessed June 07, 2024).

29

Kiptot E. Franzel S. (2012). Gender and agroforestry in Africa: a review of women’s participation. Agrofor. Syst.84, 35–58. doi: 10.1007/s10457-011-9419-y

30

Kırmızı Ö. Karaman A. (2021). A participatory planning model in the context of historic urban landscape: the case of Kyrenia’s historic port area. Land Use Policy102:105130. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105130

31

Lachapelle P. R. (2008). A sense of ownership in community development: understanding the potential for participation in community planning efforts. Community Dev.39, 52–59. doi: 10.1080/15575330809489730

32

Leary M. R. (2010). A comprehensive review for readers wishing to expand their knowledge on the field of social acceptance and rejection.

33

Maduane (2022). Exploring the challenges and opportunities of rural women farmers in selected provinces in South Africa. Master’s dissertation. North-West University.

34

Meaza A. (2009). Factors affecting women participation in politics and decision making. Master’s dissertation. University of Connecticut.

35

Mishra K. Sam A. G. (2016). Does women’s land ownership promote their empowerment? Empirical evidence from Nepal. World Dev.78, 360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.003

36

Mozumdar L. Farid K. S. Sarma P. K. (2017). Relevance of social capital in women’s business performance in Bangladesh. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ.15, 87–94. doi: 10.3329/jbau.v15i1.33533

37

Mpumalanga Provincial Government (2011). Comprehensive rural development programme concept document. Mbombela: Government Printers.

38

Mwambi M. Bijman J. Galie A. (2021). The effect of membership in producer organizations on women's empowerment: evidence from Kenya. Women's Stud. Int. Forum87, 102–492. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102492

39

Nabil N. A. Abd Eldayem G. E. (2015). Influence of mixed land-use on realizing the social capital. HBRC J.11, 285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.hbrcj.2014.03.009

40

Nelson J. A. (1996). Feminism, objectivity and economics. London: Routledge.

41

Ngomane T. S. Sebola M. P. (2022). “Land rights: Mpumalanga communities' attitudes towards women's land ownership.” International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives (IPADA). pp. 59–65.

42

Njoh A. J. Ananga E. (2016). The development hypothesis of women empowerment in the millennium development goals tested in the context women’s access to land in Africa. Soc. Indic. Res.128, 89–104. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1020-8

43

Oktarina T. N. Yulianti A. (2022). The role of women in sustainable development and environmental protection: a discourse of ecofeminism in Indonesia. Indonesian J. Environ. Law Sustain. Dev.1, 107–138. doi: 10.15294/ijel.v1i2.58137

44

Opoku P. Ali A. K. Ampadu-Daaduam P. Akoto D. A. (2025). Breaking the barriers for women participation in agroforestry in the context of AfCFTA. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospacial Sci.8, 1–11. doi: 10.48346/IMIST.PRSM/ajlp-gs.v8i1.51986

45

Öztürk Y. M. (2020). An overview of ecofeminism: women, nature, and hierarchies. J. Acad. Soc. Sci. Stud.13, 1–10. doi: 10.29228/JASSS.45458

46

Pacheco Rodriguez M. N. Rosales Lozada L. F. (2020). The United Nations declaration on the rights of peasants and other people working in rural areas: one step forward in the promotion of human rights for the most vulnerable, (123).

47

Phillips R. Pittman R. (2014). An introduction to community development. 2nd Edn. New York: Routledge.

48

Poudyal M. (2009). Tree tenure in agroforestry parklands: Implications for the management, utilization and ecology of shea and locust bean trees in northern Ghana.

49

Puleo A. H. (2017). What is ecofeminism. Quad. Mediterr.25, 27–34. Available at: https://www.iemed.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/What-is-Ecofeminism_.pdf (Accessed February 18, 2025).

50

Rowe J. (2016). Theories of local economic development. 1st Edn. New York: Routledge.

51

Samuels F. Ghimire A. (2018). “Small but persistent steps on the road to gender equality: marriage patterns in far West Nepal” in Empowering adolescent girls in developing countries (London: Routledge).

52

Samuels F. Ghimire A. Maclure M. (2018). “Continuity and slow change: how embedded programmes improve the lives of adolescent girls” in Empowering adolescent girls in developing countries (London: Routledge).

53

Schaumberg R. L. Flynn F. J. (2017). Self-reliance: a gender perspective on its relationship to communality and leadership evaluations. Acad. Manag. J.60, 1859–1881. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.0018

54

Schuler D. (2010). Community networks and the evolution of civic intelligence. AI & Soc.25, 291–307. doi: 10.1007/s00146-009-0260-z

55

Silvey R. Elmhirst R. (2003). Engendering social capital: Women workers and rural–urban networks in Indonesia’s crisis. London: Elsevier Science Ltd, Great Britain.

56

Tumusiime E. Cohen M. J. (2017). Promoting country ownership and inclusive growth? An assessment of feed the future. Dev. Pract.27, 4–15. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2017.1258037

57

UN Human Rights (2013). Realizing women’s rights to land and other productive resources. New York: UN Women.

58

Wily L. A. (2012). “Customary land tenure in the modern world” in Rights to resources in crisis: Reviewing the fate of customary tenure in Africa (Washington DC: The Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI)).

59

Winkler T. (2019). Exploring some of the complexities of planning on ‘communal land’ in the former Transkei. Town Reg. Plann.75, 6–16. doi: 10.18820/2415-0495/trp75i1.3

Summary

Keywords

community development, communal land, ecofeminism, inclusive participation, social acceptability, social capital

Citation

Zulu HP, Lukhele TM and Sabela PT (2025) A conceptual framework for inclusive participation in communal land development: feminism perspective. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1467650. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1467650

Received

20 July 2024

Accepted

11 June 2025

Published

01 July 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Soledad Soza, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

Reviewed by

Juan Mansilla Sepúlveda, Temuco Catholic University, Chile

Marbella Sánchez-Soriano, National Institute of Technology of Mexico, Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zulu, Lukhele and Sabela.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Themba Mfanafuthi Lukhele, themba.lukhele@ump.ac.zaHlengiwe Patronella Zulu, hlengiwe.zulu@ump.ac.za

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.