Abstract

This study examines six participatory development cases situated in diverse institutional and sectoral contexts across Albania, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kosovo, the Philippines, and Tanzania. The study explores how systemic transformation emerges through co-design, adaptive learning, and institutional alignment,moving beyond linear input-output models of research impact. Using a developmental systems lens, the study treats impact not as a final result, but as a dynamic outcome shaped by the interplay of behavior, norms, and structures over time. Over 1,800 semi-structured interviews were triangulated with project documents, observational data, and binary logistic regression models to examine the influence of 10 participatory design features on sustained developmental outcomes. A key finding is that participation, particularly in monitoring, adaptive learning, and early framing, is not merely procedural but a systemic driver of institutional legitimacy, stakeholder trust, and long-term uptake. Countries with embedded participatory mechanisms, such as Ethiopia and Albania, showed deeper policy integration and structural change, while fragmented governance contexts, such as Tanzania and Kosovo, saw limited institutional embedding despite localized behavioral shifts. Crucially, the study argues that how research is done—who frames it, who participates in it, and how it adapts—is as consequential as what it seeks to achieve. Methodological integration of qualitative sensemaking and quantitative modeling offers practical insights into navigating complexity in research-to-impact pathways. Rather than serving as a report on six distinct cases, this article positions them as illustrations of a broader paradigm shift: from static, technocratic models to dynamic, participatory systems approaches. It offers both theoretical grounding and actionable guidance for researchers, implementers, and policymakers seeking to align evaluation and design with the realities of complex social systems.

Introduction

In the evolving field of development finance and cooperation, the relevance of Pyle's (1984) work, “Life After Project,” remains crucial, particularly in understanding the inclusion, sustainability, and scalability of development outcomes and the lessons that can be learned from both successes and failures. Pyle critiqued the tendency of pilot projects to generate initial enthusiasm by showcasing small-scale successes, only for their impact to diminish or disappear altogether once the projects end. This highlights the fundamental challenge of transitioning from pilot projects to sustainable, scalable initiatives that continue to generate impact long after the formal conclusion of the project.

This paper is primarily a research-based analysis informed by a developmental systems lens, a conceptual framework that emphasizes the complex, adaptive, and evolving nature of change processes across time and scales. Unlike conventional linear models of research dissemination, this study recognizes that the translation of research into societal impact is shaped by a constellation of dynamic interactions across actors, institutions, and contexts. In doing so, the study bridges a critical gap in current research by offering both empirical evaluation and theoretical reflection, with a particular focus on participatory development (Tacchi et al., 2010; Cousins and Earl, 2004; Chouinard and Milley, 2018).

While the cases are based in six countries, the study does not approach them as representative “country cases.” Instead, each case is treated as a distinct contextual system, comprising sectoral, institutional, and political dimensions, through which systemic impact is examined. This allows the analysis to avoid essentialist assumptions and focus on situated dynamics. Having this in mind, what distinguishes this paper is its dual aim: to empirically examine the factors shaping research-to-impact pathways, and to explore how participatory development both influences and is influenced by dynamic systems. Unlike many existing studies that assess impact retrospectively through structured models or treat participation as procedural, this paper positions participation as a systemic and epistemological force. For instance, Belcher and Hughes (2021) emphasize outputs within logic-based frameworks, overlooking adaptive complexity. Wailzer and Soyer (2022) co-develop participatory models but frame them within bounded theories of change. Faure et al. (2020) apply participatory assessments but focus on validation, not emergence. Even reflexive approaches like Blundo-Canto and Ferré (2022) stop short of theorizing participation as a driver of systemic change. Likewise, while Douthwaite et al. (2023) address long causal chains, their model lacks a fully integrated developmental systems perspective. This paper fills that gap by treating participation as a co-evolving mechanism in complex systems of change.

This study positions itself by theorizing participatory development as a co-evolutionary process within developmental systems. It provides a forward-looking model in which participation and system transformation are mutually constitutive, enabling more adaptive, inclusive, and contextually responsive research-to-impact pathways. The study also critiques conventional research-impact frameworks and advocates for approaches informed by evolutionary economics and complex systems thinking (Nishibe, 2006; Helbing and Kirman, 2013), which are more suitable for capturing the dynamics of systemic change. Success in development, this study argues, should be redefined to include structural transformations and long-term impacts rather than focusing solely on short-term metrics. Through a comparative analysis of projects in the six countries, this study highlights how context-specific factors influence development outcomes. By emphasizing stakeholder-centered approaches, it advocates for policies and practices that prioritize inclusivity, sustainability, and scalability. The findings aim to provide actionable guidance for researchers and practitioners to design and implement development projects that place disadvantaged groups at the core of defining success, ensuring their voices shape impactful, long-term outcomes.

The principle “Nothing About Them Without Them” serves as a guiding philosophy for effective development work, emphasizing the importance of involving primary stakeholders, often labeled as “beneficiaries,” in every phase of a project. From co-design to monitoring, evaluation, and learning, their involvement ensures that development initiatives genuinely address their needs and aspirations. This principle aligns with a broader focus on social justice, human rights, and participatory development (Gupta et al., 2015; Gupta and Pouw, 2017; Kyamusugulwa, 2013). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) further underline this by adopting the “Leave No One Behind” framework, which commits to prioritizing disadvantaged groups in development efforts (Weber, 2018).

At the heart of impactful development interventions is the identification and understanding of disadvantaged and excluded groups. These groups are often heterogeneous, including women, ethnic minorities, internal migrants, individuals with disabilities, and those living in remote areas. Structural inequalities, as noted by Bailey et al. (2017), limit access to essential resources, opportunities, and capabilities, leading to exclusion. This calls for development interventions to identify and address these root causes of exclusion during the development initiatives' analysis or research phase. As Stockless and Brière (2024) emphasize, this requires asking the right questions during the design phase, supported by research, to understand the systemic inequalities that prolong exclusion.

Recent research shows that inclusiveness in development is essential for translating research into impactful, long-term outcomes (Grin et al., 2010; Bradshaw et al., 2017). It extends beyond economic growth and income equality, focusing on empowering disadvantaged groups to actively participate in and benefit from development processes. Studies demonstrate that interventions grounded in inclusive research design, such as social and communication skills training and personalized support, significantly improve the social integration of individuals with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries (Saran et al., 2020). Research also confirms that enhancing individual agency through participatory approaches leads to better mental health outcomes and improved capacity for navigating social and economic opportunities (Shankar et al., 2019). This means that projects that integrate such evidence-driven strategies during the design and implementation phases achieve more sustainable and meaningful impacts, reducing the risk of perpetuating structural inequalities.

This study further highlights that effective development projects require collaboration across multiple stakeholders, emphasizing the importance of engaging those with power and resources alongside disadvantaged groups. Community-Based Inclusive Development (CBID) models illustrate how research-driven approaches enhance inclusiveness by involving disadvantaged populations in project planning and implementation (Varughese et al., 2025). This collaboration creates synergies between research insights and on-the-ground interventions, ensuring that projects are contextually responsive and adaptable.

However, many development projects fail to adequately incorporate insights from post-project evaluations (ex-post) into the design of new initiatives (ex-ante). As Garbero et al. (2023) argue, “inclusion by design” must be intentional and proactive, identifying barriers and opportunities for disadvantaged groups from the outset. This approach resonates with Sen's (1999) capabilities framework, which asserts that meaningful development occurs when interventions enhance the wellbeing, freedom, and agency of primary stakeholders.

Ensuring inclusivity in development requires multiple research-informed pathways to create systemic and transformative impact. One pathway involves leveraging opportunities within specific sectors. For example, in Albania, the information, communication, and technology (ICT) sector was identified for its potential to employ disadvantaged groups, including women, Roma communities, and disabled youth. This reflects labor market segmentation theory, which suggests that certain sectors offer more equitable access when inclusive strategies are implemented (Grimshaw et al., 2017). Another pathway focuses on geographical targeting, addressing spatial inequalities by implementing interventions tailored to regions with high concentrations of disadvantaged populations. In Kosovo, a job portal accessible in the Serbian language targeted Serbian communities, demonstrating strategies that address location-based barriers to opportunity (Bhaumik et al., 2011).

Inclusive development also requires engagement with both formal and informal institutions that shape power relations. Projects challenge institutional barriers by involving public institutions, civil society organizations, and community leaders. This aligns with Gaventa's (2021) “power cube” framework, which emphasizes addressing visible, hidden, and invisible dimensions of power to enhance systemic inclusion. However, a key challenge for projects promoting inclusivity is balancing the pressure to deliver short-term results with the need for long-term systemic change by understanding key constraints during the research and design process. Donors and policymakers often prioritize immediate, measurable outcomes, such as job creation or increased investment, over deeper, structural transformation (Stanley and Connolly, 2023). This pressure can hinder projects from addressing the root causes of exclusion, resulting in only incremental improvements.

This means that achieving systemic change requires sustained efforts to reform how institutions operate and how disadvantaged groups access opportunities. These transformations often take time and do not yield immediate, quantifiable results, making it difficult to align with traditional evaluation models that emphasize linear cause-effect relationships and short-term outputs (Gutheil, 2021). To navigate these tensions, research suggests taking up adaptive management approaches that allow projects to respond to evolving conditions. Agile monitoring and evaluation systems track real-time changes and support adaptive interventions in complex environments (Synowiec et al., 2023). Despite these recommendations, many development evaluation models remain ill-equipped to capture non-linear, feedback-driven processes, creating a bias against systemic change initiatives (Reilly-King et al., 2024).

Materials and methods

This study explores how participatory development research can facilitate inclusive, sustainable, and scalable impact by driving systemic change within complex development contexts. Rather than treating impact as a linear outcome of knowledge dissemination, the research frames it as an emergent property of dynamic interactions between actors, institutions, and environments. It employs a developmental systems lens that highlights the importance of feedback loops, adaptive learning, and institutional evolution over time (Capra and Luisi, 2014; Senge, 2006). This lens enables a focus on how change unfolds across interdependent domains—behavioral, structural, and normative—rather than isolating discrete interventions.

However, systems thinking alone is often critiqued for its abstract, depoliticized treatment of power. It may obscure the influence of historical inequality, institutional inertia, and elite capture, which frequently undermine participatory intent and distort pathways to impact (Cooke and Kothari, 2001; Gaventa, 2006). To address these blind spots, the study integrates a Participatory Action Research (PAR) methodology that foregrounds the lived experiences, agency, and knowledge of stakeholders, particularly those traditionally excluded from decision-making. PAR offers a practical and ethical commitment to epistemic justice, ensuring that affected communities are not just consulted but actively shape the research process, from agenda-setting to interpretation and validation. This methodological synergy between systems thinking and participatory action enables a more reflexive, power-aware analysis of how research contributes to transformative development.

PAR: justification and implementation

This study employed PAR as a guiding methodological orientation to ensure that research processes were inclusive, contextually grounded, and responsive to the lived realities of local actors. PAR was used across all six countries as a framework for engaging stakeholders not only as informants but as co-designers and validators of the research process. This approach was particularly relevant in contexts where participatory development projects were already underway, and where community actors had experiential knowledge that could meaningfully inform both the framing and interpretation of research-to-impact pathways (Reason and Bradbury, 2008; Kindon et al., 2007; Pain and Kesby, 2007).

Co-design workshops were held at the start of the research process to identify priority themes and refine tools in collaboration with local actors, such as civil society groups in Kosovo, farmer cooperatives in Tanzania, and frontline service providers in Ethiopia. These engagements contributed to the adaptation of interview instruments to local cultural and institutional contexts and ensured that key concepts (e.g., “impact,” “inclusion,” “systemic change”) were aligned with stakeholders' lived experience. Additionally, facilitators were trained and supported to assist with interviews, contextual translation, and post-interview discussions, particularly in linguistically or politically sensitive settings.

PAR also supported iterative data validation through structured feedback sessions, where preliminary themes were shared with community participants for comment, correction, or expansion. For example, in Bangladesh, stakeholder feedback led to the refinement of one category from “technical training” to “confidence-building spaces,” reflecting participants' emphasis on emotional security as a precondition for participation. These exchanges helped ensure that interpretive accuracy was grounded in local narratives, not only the researcher's assumptions.

However, the use of PAR also presented practical and epistemological limitations. While participatory processes were widely welcomed in principle, time constraints, political sensitivities, the COVID pandemic, and power asymmetries within communities often limited the depth of engagement. In some settings, gatekeeping by local elites or organizational partners influenced who could participate in workshops or interviews, potentially reinforcing existing hierarchies, an issue noted in broader PAR literature as a recurring challenge (Cooke and Kothari, 2001; Cornwall, 2008). Furthermore, participation was uneven across sites. In Ethiopia and the Philippines, conflict and COVID-19-related disruptions meant that participatory activities had to be adapted for remote formats, which limited the inclusion of the most vulnerable populations.

There were also methodological trade-offs. While PAR enabled responsiveness and co-production, it introduced variability across contexts in how research was shaped and carried out. This posed challenges for comparability and consistency in data collection. In some contexts, researchers had to balance collaborative ideals with the need for analytical clarity and timeline management, highlighting the tension between deliberative depth and operational feasibility (Cahill, 2007; Pain and Francis, 2003). In addition, while many participants expressed appreciation for their involvement, not all had the capacity or interest to engage in reflexive processes, raising ethical questions about participation fatigue and over-asking in settings where time and resources were limited. Despite these constraints, PAR added significant value by enhancing contextual relevance, stakeholder legitimacy, and trust. It helped surface hidden narratives. This was true especially around power, legitimacy, and emotional safety, which might have been missed in conventional methods.

Country selection: rationale and limitations

It is important to emphasize that the term “country” is used here as a geographic anchor, not as an explanatory category. The study focuses on case-based systemic configurations, not national attributes, thereby avoiding reductionist comparisons. Based on this understanding, the six countries of Albania, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kosovo, the Philippines, and Tanzania were selected through purposive sampling to reflect institutional, geographic, and sectoral variation in research-to-impact dynamics. The selection was not designed for representativeness in a statistical sense, but rather to enable analytical generalization by examining contrasting systems where participatory development projects had been implemented with varying levels of institutional maturity and civic engagement (Flyvbjerg, 2006; Yin, 2017).

The selection was guided by five interlinked criteria. First, each country had an established participatory research initiative active during or before the study period, providing a foundation for stakeholder engagement and retrospective inquiry. All six projects explicitly stated that they used a systems approach, often presented as “Market Systems Development” (MSD). For example, Bangladesh featured gender-responsive agricultural programming focused on medicinal herbs for landless women, Ethiopia emphasized women's participation in income-generating sectors such as agriculture and hospitality, and the Philippines supported livelihood transitions for farmers post-disaster. Tanzania explored horticulture as a pathway to income and employment for youth and women, while Albania and Kosovo focused on youth education and employment.

Second, the study prioritized sectoral diversity to capture how inclusive development unfolds across different systems. The selected cases span agriculture, education, labor markets, and local governance. These were sectors marked by both institutional change and political contestation. These domains allowed analysis of varying institutional dynamics and power relations, from education-to-employment transitions in the Balkans to gendered agricultural innovation in South Asia and East Africa, and disaster-related reforms in Southeast Asia.

Third, institutional diversity was key. Countries ranged from relatively stable bureaucracies (e.g., Bangladesh, Albania) to more fragile or post-conflict settings (e.g., Ethiopia, Kosovo), allowing the study to observe how context-specific political and historical legacies shaped participatory processes and impact pathways (Thelen, 2004; Gaventa, 2006). Fourth, cultural and geographic variation was deliberately built into capture differences in local governance traditions, social hierarchies, and knowledge practices across South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Europe. This heterogeneity was valuable for analyzing how localized meanings of participation, legitimacy, and research relevance were co-constructed and challenged. Finally, all selected countries had established research partnerships or trusted local collaborators, which were essential for ensuring ethical engagement, cultural translation, and logistical feasibility (Clark et al., 2021).

Despite this strategic design, the approach carries important limitations. First, the purposive and context-driven selection means that findings cannot be generalized statistically to all development contexts; rather, they offer theory-building insights through comparative exploration of diverse cases (Yin, 2017). Second, access to some populations was constrained. In Ethiopia and parts of the Philippines, armed conflict and COVID-19 restrictions disrupted field activities, limited travel to remote regions, and restricted the participation of vulnerable groups, such as displaced persons, informal workers, and minority communities (Hickey and Mohan, 2004).

While local facilitators conducted interviews in participants' preferred languages and helped contextualize meanings, the process of transcription and translation inevitably led to some loss of nuance, particularly in emotionally charged or culturally specific terms. Even with back-translation checks, certain expressions of legitimacy, trust, or power could not be fully captured in English without interpretive framing.

Cross-country comparison also posed analytical challenges. Although a shared framework was applied across all cases, the degree of methodological adaptation required in each country, due to institutional realities, language, and political sensitivities, meant that comparisons had to remain interpretive and flexible. This shows the importance of reflexivity and humility in comparative research, particularly in global South contexts where uniformity may be both unrealistic and undesirable (Cornwall, 2008).

Data collection: semi-structured interviews and triangulation

The core qualitative data collection method was semi-structured interviews, chosen for their ability to strike a balance between comparability across sites and contextual depth. This approach allowed the research to pursue key themes: project participation, institutional shifts, adaptive learning, and developmental outcomes. The study tried, as much as possible, to remain responsive to localized meanings and participant narratives. Interviews typically lasted between 45 and 90 min, conducted in the native languages of participants by trained local facilitators and/or bilingual researchers, which significantly enhanced both rapport and data quality (Barriball and While, 1994; Ahlin, 2019).

Participants were briefed on the purpose of the research and informed of their rights, including confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized to ensure ethical data handling and minimize identification risks. To further enhance data reliability and mitigate researcher bias, triangulation was employed through three complementary strategies:

Document reviews

Data collectors examined project reports, monitoring and evaluation documents, training manuals, and institutional frameworks relevant to each case. This helped situate participant accounts within broader institutional processes and timelines and allowed researchers to validate or contrast interview findings against the official record (Kallio et al., 2016).

Project visits

Data collectors participated in site visits to project locations, where they observed the physical and organizational settings in which interventions were implemented. These visits facilitated real-time conversations with stakeholders, exposure to operational dynamics, and a deeper understanding of implementation realities, especially useful in evaluating participation, accessibility, and visible outcomes (Phillippi and Lauderdale, 2018).

Field observations

Structured and unstructured non-participant observation was conducted in community meetings, training sessions, market settings, and project demonstration sites. These observations helped capture non-verbal cues, gendered interactions, group hierarchies, and informal dynamics often missed in interviews. They also served as a critical tool to verify the coherence between stated narratives and observed practices (Gubrium and Holstein, 1998). Where permitted, transcripts were returned to participants for member checking, a process that increased trust and allowed respondents to review or clarify statements, enhancing both accuracy and reflexivity. However, logistical barriers such as limited connectivity, literacy constraints, and time availability made this step uneven across sites.

While semi-structured interviews provided rich and adaptable insights, challenges were evident. Comparability across contexts varied depending on how participants interpreted or re-framed questions. Interviewers had to balance following the guide with allowing space for emergent, locally significant themes. In some cases, power dynamics, especially in hierarchical or gendered contexts, subtly shaped what was voiced and what remained unspoken. The triangulated approach not only deepened validity but also clarified gaps between policy and practice, revealed discrepancies between official reports and community narratives, and strengthened the interpretive robustness of the qualitative analysis (Roulston and Choi, 2018; Cachia and Millward, 2011). To ensure relevance, inclusivity, and contextual sensitivity, the study employed a two-tiered sampling strategy, combining purposive and snowball sampling methods. These approaches are widely recognized in qualitative research for their ability to access information-rich cases and marginalized voices within complex social systems (Patton, 2011; Noy, 2008).

The primary method was purposive sampling, through which participants were deliberately selected based on their direct engagement in the observed projects. These included local project implementers, government partners, facilitators, and community-based “beneficiaries”. The aim was to capture perspectives from both “formal actors” (e.g., government or NGO staff) and “experiential actors” (e.g., youth participants, women entrepreneurs, or smallholder farmers) who were integral to the implementation or impact of interventions. Care was taken to ensure balance across gender, institutional roles, age, and geographic location, thereby increasing representational diversity and enhancing the credibility of findings (Palinkas et al., 2015). Particular attention was given to including women and youth in traditionally underrepresented sectors such as agricultural R&D and vocational education.

In more remote, fragile, or socially embedded contexts, such as ethnic minority groups, women in rural governance, or informal sector workers, snowball sampling was applied to supplement participant lists. Initial informants recommended others whose insights were vital for understanding institutional dynamics, exclusions, and informal networks within local systems. This method is especially effective in reaching “hidden” or “hard-to-reach” populations and generating insider knowledge (Noy, 2008; Sadler et al., 2010). While snowball sampling enriched the diversity of perspectives, it also presented risks of network bias, wherein dominant or vocal actors might overrepresent particular viewpoints. To counteract this, the study sought referrals across multiple entry points and community gatekeepers to ensure triangulated access.

Local facilitators were indispensable in both phases of sampling. Their presence helped establish community trust, facilitated linguistic translation of technical concepts, and ensured that culturally sensitive engagement protocols were followed. In many cases, they also identified non-verbal cues or informal hierarchies that helped the research team navigate power asymmetries. These relationships were especially important in communities where formal authority structures were weak or contested. Moreover, facilitators helped bridge logistical and sociocultural barriers, including low literacy levels, limited digital connectivity, and local dialect variations. These challenges are commonly cited in participatory research in low-income settings (Creswell and Poth, 2016; Guest et al., 2006).

Analytical strategy: integrating quantitative and qualitative methods

By integrating binary logistic regression and sensemaking-based qualitative analysis, the study sought to capture both measurable patterns of impact and the subjective meanings that shaped stakeholder engagement and outcomes. This approach aligned with the study's PAR ethos, which emphasized collaboration, contextual sensitivity, and mutual learning. It is important to clarify that while the regression model helps identify statistical associations, it is not the centerpiece of this study. Its purpose is to scaffold the more central methodological innovation: integrating participatory sensemaking with quantitative trends to advance complexity-informed evaluation.

The quantitative component used binary logistic regression to model the likelihood of specific development outcomes, such as behavioral adoption, institutional engagement, or sustained use of tools, based on a range of independent variables, including gender, age, education, institutional role, and level of participation. The regression models enabled the identification of statistically significant associations while controlling for confounding factors, offering a structured view of how participation patterns varied across demographic and institutional contexts. For instance, the models demonstrated that individuals who engaged in co-design or monitoring platforms were more likely to report continued use of research-derived practices. These findings echoed evidence from other development evaluations (McEvoy et al., 2016; Rinaldi, 2020), affirming that structured stakeholder engagement can influence long-term adoption of new behaviors or norms.

However, logistic regression, while useful for identifying associations, could not explain the underlying mechanisms or contextual conditions behind these patterns. It was therefore complemented by a robust qualitative analysis using sensemaking. Sensemaking, as developed by Weick (1995) and extended by Maitlis and Christianson (2014), focuses on how individuals and groups interpret change in situations of complexity or uncertainty. It is not merely about reporting facts, but about how stakeholders frame, justify, and emotionally respond to development processes. In this study, sensemaking enabled researchers to interpret not just whether change occurred, but how it was understood, what it meant to different actors, and why it was embraced or resisted.

Qualitative data, primarily from semi-structured interviews with over 1,800 participants, were analyzed using NVivo 12. The coding process was both deductive, based on the study's conceptual framework (shifts in behaviors, structures, and norms), and inductive, allowing new themes to emerge from the data itself. This dual approach enabled consistent thematic structuring across countries while also capturing local nuances, contested narratives, and emergent insights. For example, in the Philippines, research outputs were viewed by local officials not only as technical tools but as instruments of political legitimacy. In Ethiopia, women described project engagement as a process of redefining their public identities, not just as economic actors but as legitimate leaders within their communities.

This combined method provided powerful triangulation. Where regression models revealed patterns (e.g., platform participation correlated with behavior change), qualitative sensemaking helped explain the relational and institutional mechanisms behind those patterns, such as trust, peer learning, or symbolic recognition. In cases where quantitative data showed no significant effect, qualitative findings often exposed invisible barriers like elite capture, local skepticism, or governance failures that suppressed impact. This kind of integrative analysis enhanced both the validity and interpretive richness of the study, providing a layered understanding of how research engagement leads to, or fails to produce, systemic transformation.

Nevertheless, the integration of these methods was not without its challenges. One of the primary difficulties was the temporal and epistemological disconnect between quantitative and qualitative data. Regression analysis required standardized variables and clear causal relationships, while sensemaking relied on narrative depth and contextual specificity. Aligning these two modes of evidence required careful iterative work. The study revisited codes, refined models, and negotiated tensions between generalization and nuance. Another challenge involved data comparability across countries. While regression relied on consistent metrics, qualitative interviews varied in length, tone, and cultural framing, making synthesis across settings complex. Furthermore, software constraints occasionally made cross-case NVivo analysis cumbersome, particularly when working with multilingual datasets and team-based coding protocols.

Despite these challenges, the participatory design of the research process helped mitigate several risks. Adhering to the principle of “Nothing About Them Without Them,” the study included participants in co-analysis sessions, transcript reviews, and validation workshops. These steps ensured that stakeholder voices remained central in the interpretation of both quantitative results and qualitative insights. This reflexive engagement also helped ensure the cultural and ethical appropriateness of findings, while enhancing their policy relevance and stakeholder legitimacy.

Binary regression model

The detailed regression modeling is offered not as a demonstration of technical rigor alone, but to show how traditional statistical tools can be repositioned within a participatory and systems-oriented research logic. This reframing is central to methodological shifts needed in dynamic evaluation settings. To provide a rigorous, transparent, and actionable understanding of the conditions under which development research achieves systemic impact, the study used five steps of model specification (Equation 1), probability estimation (Equation 2), interpretation (Equation 3), marginal insights (Equation 4), and marginal effects and policy insights. Beyond confirming that participation matters, the model demonstrated that structured stakeholder engagement, adaptive learning, and gender-responsiveness are not simply ideals; they are also empirical drivers of success.

Given the binary nature of the outcome, where Y = 1 indicates a successful research-to-impact transition and Y = 0 indicates failure, the logistic regression model is structured to estimate the log odds of success as a function of key project design and stakeholder engagement variables. The general form of the model is expressed as:

In this model, P(Y=1) denotes the probability of achieving a successful development outcome, where Y represents the dependent variable, indicating whether the desired outcome was realized. The model incorporates:

-

β0: the intercept, representing the baseline log odds of success when all independent variables are zero.

-

β1,β2,…,βn: coefficients for independent variables X1, X2,…, Xn, which correspond to various factors associated with the 10 variables— from stakeholder involvement in project to co-creation of research questions, research relevance in design, valuing local knowledge, adaptive learning, resource allocation, collaborative networks, gender-sensitive indicators, stakeholder participation in M&E, and feedback mechanisms.

-

ϵ: the error term, accounting for unexplained variability in the model.

The probability function derived from Equation 1 is used to calculate individual probabilities of success as:

Equation 2 allows the study to model how different combinations of engagement and design features influence the predicted likelihood of success. For the estimation and interpretation, the coefficients βiwere estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), which identifies the values of β that maximize the probability of observing the actual outcomes in the data. For interpretation, odds ratios are derived from the estimated coefficients:

Equation 3 provides an intuitive measure: an odds ratio >1 indicates a positive association between Xi and project success, while a value below 1 suggests a negative relationship.

To assess the reliability of the binary logistic regression results, two key diagnostic tests were employed: the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and McFadden's pseudo-R2. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test evaluates whether the model's predicted probabilities align with actual outcomes. A non-significant result suggests good model fit. In this study, the test produced a p-value of 0.43, indicating no significant deviation between predicted and observed values, thus confirming a satisfactory fit.

The McFadden's pseudo-R2 was used to assess the model's explanatory power. With a value of 0.23, the model falls within the range typically deemed acceptable for social science models dealing with complex, behaviorally driven outcomes (0.2–0.4). This suggests that the selected predictors meaningfully account for variation in whether projects achieved sustained, inclusive impact. These diagnostics affirm that the regression estimates derived from Equations 1–3 are both statistically valid and substantively relevant.

While odds ratios provide useful information on relative likelihoods, they are often less intuitive for policy application. Hence, the study computed Average Marginal Effects (AMEs) to determine how much the probability of success changes with a one-unit increase in each Xi,holding other variables constant:

This marginal effect function (Equation 4) was particularly valuable in translating technical results into actionable recommendations. For example, stakeholder participation in co-design activities increased the probability of success by 15%−18% across multiple countries. In practice, this means that enhancing co-design practices can significantly improve the developmental outcomes of research investments.

Results

As presented in Tables 1, 2, the quantitative method shows a converging empirical narrative: participatory and adaptive features embedded in project design are not peripheral, but they are essential predictors of whether development interventions produce inclusive and sustained impact. As shown in Table 3, the consistency of these patterns across diverse countries and sectors enhances the generalizability of the study's conclusions and substantiates the claim that systemic change is not merely about delivering outputs but about shaping institutional relationships, trust, learning processes, and collective legitimacy. This reinforces a central argument of the study: how research is done—who frames it, who participates in it, and how it adapts—is as consequential as what it seeks to achieve.

Table 1

| Country | Sample size | Type of participants | Year(s) of data collection | Type of project |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 275 | Youth trainees, ICT instructors, and vocational program administrators | 2021–2023 | ICT employment and inclusive skills training |

| Bangladesh | 350 | Female farmers, NGO facilitators, and local agricultural officers | 2022–2023 | Access to land and gender-responsive agriculture |

| Ethiopia | 325 | Women farmers, agricultural entrepreneurs, and local development planners | 2019–2023 | Livelihood innovation and women's participation in agriculture and services |

| Kosovo | 275 | Local entrepreneurs, municipal officials, and CSO representatives | 2021–2023 | Inclusion in local economic development, such as skills and education |

| Philippines | 300 | Women farmers, disaster recovery personnel, and education officials | 2020–2022 | Post-disaster recovery and adaptive skills in relevant sector initiatives |

| Tanzania | 275 | Youth farmers, women in horticulture, and agricultural extension agents | 2022–2023 | Agricultural R&D and inclusion in market access |

Sample size, participants, and type of projects covered.

Table 2

| Variable code | Name | Type | Concept captured |

|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Stakeholder involvement in framing | Binary | Early co-creation and ownership |

| X2 | Participation in M&E | Binary | Reflexivity, mutual accountability |

| X3 | Integration of local knowledge | Binary | Contextual alignment and epistemic inclusion |

| X4 | Gender-sensitive indicators | Binary | Gender equity and inclusion |

| X5 | Adaptive learning mechanisms | Binary/ordinal | Flexibility, responsiveness |

| X6 | Resource adequacy | Ordinal | Implementation capacity and responsiveness |

| X7 | Collaborative networks | Binary/ordinal | Partnerships, institutional bridges |

| X8 | Policy/institutional alignment | Binary | System integration and policy uptake |

| X9 | Feedback accessibility | Binary | Knowledge, usability, and transparency |

| X10 | Stakeholder trust | Binary/ordinal | Legitimacy and relational quality |

Regression model variables.

Table 3

| Diagnostic test | Purpose | Observed result |

|---|---|---|

| Hosmer–Lemeshow Test | Evaluates the goodness-of-fit by comparing predicted probabilities with observed outcomes across deciles of risk. A non-significant p-value suggests that the model fits the data well | p = 0.43, indicating no significant discrepancy—thus, the model is a good fit |

| McFadden's pseudo-R2 | Measures the explanatory power of the logistic regression model. Values between 0.2 and 0.4 are typically considered acceptable in social sciences | R 2 = 0.23, suggesting moderate explanatory power and adequate model fit |

Model diagnostics summary.

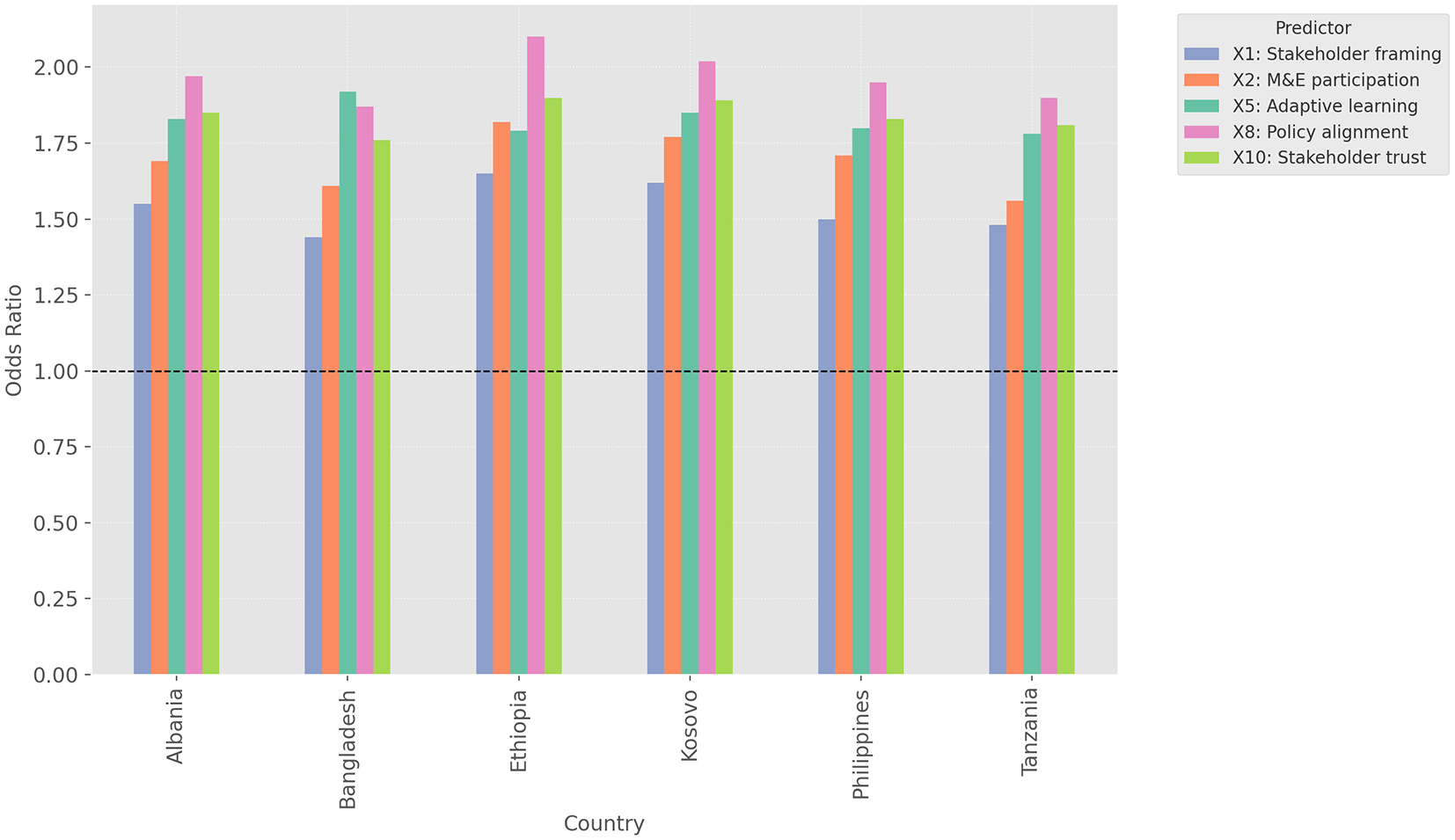

The logistic regression findings presented in Table 4 show empirical evidence for the central role of participatory design features in predicting the likelihood of achieving inclusive, sustained, and scalable development outcomes. Across the six countries, key predictors such as stakeholder participation in monitoring and evaluation (X2), adaptive learning mechanisms (X5), and policy alignment (X8) consistently demonstrated strong and statistically significant associations with project success. These variables often reached the 1% level of significance, with odds ratios ranging from 1.61 to 2.10, suggesting that these features do not just correlate with impact; they function as enabling conditions for systemic change.

Table 4

| Predictor | Albania (OR, CI, Sig) | Bangladesh (OR, CI, Sig) | Ethiopia (OR, CI, Sig) | Kosovo (OR, CI, Sig) | Philippines (OR, CI, Sig) | Tanzania (OR, CI, Sig) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1: stakeholder framing | 1.55 [1.01–2.37]* | 1.44 [0.97–2.13] | 1.65 [1.12–2.43]* | 1.62 [1.05–2.51]* | 1.50 [1.00–2.24]* | 1.48 [1.01–2.19]* |

| X2: M&E participation | 1.69 [1.11–2.58]* | 1.61 [1.08–2.42]* | 1.82 [1.21–2.74]** | 1.77 [1.15–2.72]* | 1.71 [1.15–2.55]* | 1.56 [1.06–2.30]* |

| X3: local knowledge | 1.49 [1.00–2.21]* | 1.52 [1.01–2.31]* | 1.47 [0.98–2.21] | 1.41 [0.94–2.10] | 1.45 [0.98–2.17] | 1.42 [0.95–2.11] |

| X4: gender indicators | 1.40 [0.91–2.15] | 1.38 [0.93–2.07] | 1.34 [0.89–2.03] | 1.36 [0.88–2.10] | 1.32 [0.87–2.01] | 1.30 [0.88–1.91] |

| X5: adaptive learning | 1.83 [1.22–2.75]** | 1.92 [1.30–2.85]** | 1.79 [1.15–2.78]* | 1.85 [1.21–2.81]** | 1.80 [1.23–2.65]** | 1.78 [1.19–2.66]* |

| X6: resource adequacy | 1.08 [0.76–1.53] | 1.06 [0.74–1.53] | 1.10 [0.78–1.56] | 1.14 [0.79–1.66] | 1.18 [0.81–1.71] | 1.12 [0.79–1.59] |

| X7: networks | 1.29 [0.91–1.84] | 1.43 [1.01–2.03]* | 1.25 [0.89–1.76] | 1.32 [0.90–1.94] | 1.30 [0.89–1.90] | 1.36 [1.01–1.95]* |

| X8: policy alignment | 1.97 [1.29–3.01]** | 1.87 [1.21–2.91]** | 2.10 [1.35–3.29]** | 2.02 [1.31–3.11]** | 1.95 [1.24–3.07]** | 1.90 [1.26–2.87]** |

| X9: feedback access | 1.32 [0.92–1.89] | 1.34 [0.89–2.02] | 1.58 [1.02–2.43]* | 1.36 [0.95–1.97] | 1.40 [0.94–2.09] | 1.29 [0.91–1.84] |

| X10: stakeholder trust | 1.85 [1.21–2.82]** | 1.76 [1.18–2.64]* | 1.90 [1.22–2.96]** | 1.89 [1.23–2.91]** | 1.83 [1.15–2.89]** | 1.81 [1.20–2.71]* |

Logistic regression results by country.

Significance levels for odds ratios are indicated as follows:

p < 0.05 (statistically significant at the 5% level).

p < 0.01 (statistically significant at the 1% level).

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Sig, significance level.

As a case in point, policy alignment (X8), significant across all six models, highlights the necessity of embedding project goals within existing institutional frameworks to secure legitimacy, coherence, and continuity. Similarly, adaptive learning (X5) emerged as a consistently significant driver of success. Projects with iterative feedback loops, reflexive adjustment mechanisms, and stakeholder-responsive learning were significantly more likely to sustain impact. These findings align with growing evidence in development research that highlights the importance of adaptive governance and learning-based implementation in achieving systemic change in complex contexts. Rather than following rigid plans, successful initiatives rely on iterative problem-solving and embedded learning structures. This supports approaches such as Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA), which emphasize local ownership, feedback loops, and institutional flexibility (Andrews et al., 2017; Ramalingam et al., 2014; Valters et al., 2016). The observed significance of co-design, monitoring engagement, and adaptive learning in this study reflects these principles and reinforces the need for research to act as a platform for continuous system learning.

Figure 1 shows the odds ratios for five key predictors of inclusive and sustained development impact across six countries. These predictors—stakeholder framing (X1), M&E participation (X2), adaptive learning (X5), policy alignment (X8), and stakeholder trust (X10)—consistently show odds ratios above 1, with most ranging between 1.5 and 2.1, confirming their strong positive association with project success. This reinforces the conclusion that participatory and adaptive elements are not auxiliary features but are core enabling conditions for systemic development impact.

Figure 1

Odds ratios of key predictors across countries.

Although not all variables were significant in every country, several others, particularly co-design of research framing (X1) and stakeholder trust (X10), achieved significance in at least four country models, reinforcing the centrality of epistemic inclusion and relational legitimacy. In contrast, resource adequacy (X6) and gender-sensitive indicators (X4) were less consistently significant. While their theoretical relevance remains intact, the statistical inconsistency suggests that their influence may be contingent upon institutional culture, project scale, or the depth of participatory practice, rather than their presence alone.

The robustness of the models is supported by the diagnostics presented in Table 5. All models demonstrated Hosmer–Lemeshow p-values above 0.38, indicating that the predicted probabilities were well-calibrated to observed outcomes. The McFadden's pseudo-R2 values, ranging from 0.21 to 0.25, are considered satisfactory within applied policy and social science research, especially when modeling complex behavioral, institutional, or relational processes. Importantly, Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) remained below the accepted threshold of 2.5 across all models, confirming the absence of multicollinearity and enhancing the interpretability of individual predictors. Sample sizes per country (between 275 and 350) further ensured adequate statistical power.

Table 5

| Model | McFadden's R2 | Max VIF | Hosmer-Lemeshow p | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 0.23 | 2.2 | 0.42 | 275 |

| Bangladesh | 0.21 | 2.2 | 0.39 | 350 |

| Ethiopia | 0.23 | 2.4 | 0.43 | 300 |

| Kosovo | 0.24 | 2.1 | 0.38 | 275 |

| Philippines | 0.25 | 2.3 | 0.41 | 300 |

| Tanzania | 0.22 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 275 |

Model diagnostics summary.

Complementing these findings, Table 6 presents descriptive statistics that contextualize the coding and variable distribution across the study sample. Binary variables such as X1, X2, and X3 had mean values between 0.53 and 0.66, indicating that a majority of respondents across sites reported exposure to these participatory or inclusion-oriented interventions. This distribution also ensured adequate variation for regression modeling. The lone ordinal variable, resource adequacy (X6), had a mean score of 3.45 on a 5-point scale, with a standard deviation of 0.91, reflecting moderate variation in perceived implementation quality. These descriptive statistics affirm that the predictors are not overly skewed or clustered, and they align well with assumptions of logistic regression modeling.

Table 6

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1: stakeholder framing | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| X2: M&E participation | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| X3: local knowledge | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| X4: gender indicators | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| X5: adaptive learning | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| X6: resource adequacy | 3.45 | 0.91 | 1 | 5 |

| X7: networks | 0.6 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| X8: policy alignment | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| X9: feedback access | 0.56 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| X10: stakeholder trust | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

Descriptive statistics for independent variables.

Sensemaking and qualitative analysis across six countries

The qualitative component of this study was grounded, as mentioned in the previous section, in a sensemaking approach, following the work of Weick (1995) and Maitlis and Christianson (2014). This approach focuses not only on what changed in development processes but on how those changes were interpreted, contested, or embraced by individuals and groups. Rather than treating participants as passive informants, sensemaking positioned them as agents navigating uncertainty, institutional complexity, and shifting power dynamics. The goal was to understand how stakeholders constructed meaning around participation, knowledge use, and system transformation.

The qualitative findings show a fundamental insight: how stakeholders make sense of participation significantly shapes its outcomes. Whether interpreted as empowerment, legitimacy, strategy, or tokenism, participation takes on contextual meaning that either facilitates or constrains systemic change. The study's sensemaking approach—by foregrounding emotional, symbolic, and institutional interpretations—offers critical explanatory power that complements statistical generalizability. This reinforces a central argument in adaptive development literature: that development is not just about changing structures, but about shifting the meanings and relationships that sustain them (Andrews et al., 2017; Ramalingam et al., 2014).

A total of 1,800 semi-structured interviews were conducted across six countries—Albania, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kosovo, the Philippines, and Tanzania. These interviews involved local beneficiaries, civil society representatives, implementation staff, and government actors, selected through purposive sampling to capture diverse perspectives. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using NVivo 12, following a dual-phase coding strategy.

First, deductive coding was applied using the study's conceptual framework, focusing on three interdependent dimensions of systemic change: behavioral shifts, structural transformations, and normative reorientations (Ramalingam et al., 2014). This ensured theoretical consistency across cases. Second, inductive coding was performed using in-vivo and emergent thematic approaches, allowing locally constructed meanings and unexpected insights to surface organically. This included participant metaphors, affective framings, and culturally embedded expressions.

Cross-case patterns were examined using NVivo's matrix coding tools, enabling both comparative thematic synthesis and attention to context-specific deviations. Inter-coder agreement was tested through iterative refinement of the codebook to strengthen reliability and interpretive alignment (Valters et al., 2016).

Analysis revealed that the interpretive dynamics of participation varied significantly across settings but also coalesced around a set of recurring themes. In Albania, youth engagement in ICT-based platforms was described not merely as technical capacity-building but as a route to visibility and institutional legitimacy, what one participant called “being seen by the system.” This framing resonated with Weick's (1995) conception of sensemaking as identity-relevant enactment. In Bangladesh, women engaged in gender-responsive agriculture acknowledged new agency, but often spoke of navigating institutional silences—spaces where formal recognition coexisted with persistent exclusions from authority structures.

In Ethiopia, cooperative and governance participation among women was framed as both symbolic empowerment and practical inclusion, aligning with Maitlis and Christianson's (2014) idea of “emotion-infused meaning-making.” In Kosovo, economic development projects were appreciated, but stakeholders emphasized that civic recognition and interethnic trust carried more transformative value than material outputs. In the Philippines, participatory research tools were often interpreted as political instruments, useful for enhancing legitimacy in interactions with government institutions, what Ramalingam et al. (2014) refer to as “adaptive brokerage.” In Tanzania, youth and women narrated their involvement in horticultural interventions as a means of repositioning within labor and social hierarchies, shifting institutional roles, and challenging generational norms.

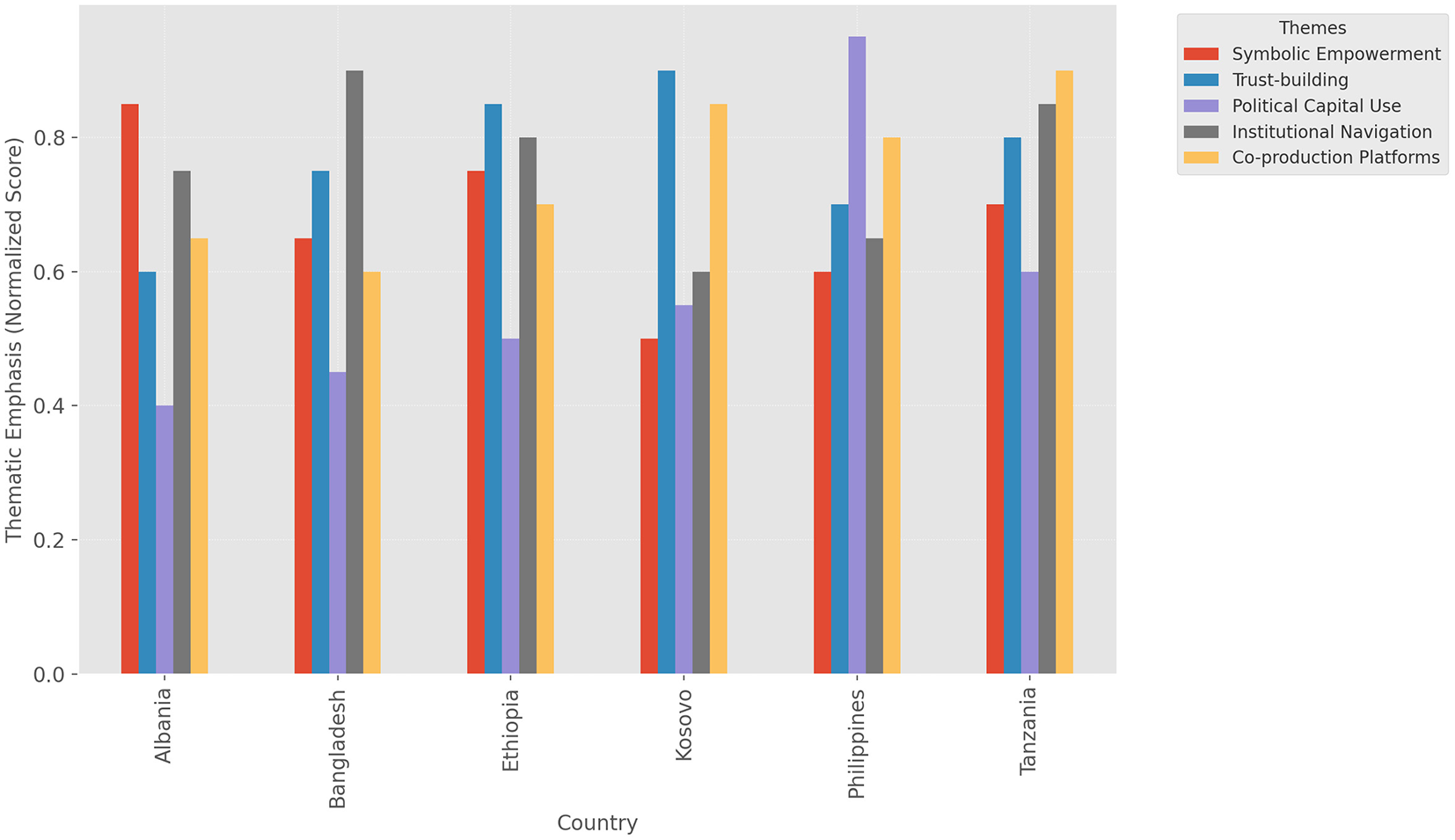

To do a deeper analysis of the findings, as shown in Figure 2, the theme of symbolic empowerment referred to how individuals perceived their participation as conferring status, legitimacy, or recognition, rather than simply transferring resources or knowledge. Symbolic empowerment played a critical role in normative shifts. It helped shift the social scripts around who was seen as capable, legitimate, or visible in institutional settings. This reinforced the idea that development outcomes are mediated by recognition and identity, not only resource flows.

Figure 2

Cross-country emphasis on key qualitative themes.

Symbolic empowerment was most pronounced in Albania, where young participants framed their involvement in ICT-based platforms as a means to be “seen” by institutions and the labor market. This reflects a context where institutional visibility is scarce, and formal inclusion mechanisms are limited. Participation was thus performative, and it reshaped participants' identities as legitimate social actors. In Ethiopia, especially among women in agricultural cooperatives and local governance, participation was experienced as public affirmation. Many described their increased involvement not just in terms of income or output, but as a way of transforming how others—and they themselves—understood their role in society.

Trust-building was another theme that captured how participatory processes create or reinforce relational legitimacy, especially in fractured or hierarchical institutional landscapes. Trust functions as an enabling condition for adaptive learning, institutional reform, and local ownership. It explains why M&E participation (X2) and stakeholder trust (X10) emerged as statistically significant predictors in the regression models. Trust is not an outcome, but rather it is a mechanism. It featured prominently in Kosovo. In a context of ethnic fragmentation, trust was not assumed; it had to be built. Participants noted that local governance forums fostered mutual recognition across ethnic lines, giving participation a symbolic and reconciliatory dimension. It was also clear in Tanzania, in both youth and women's narratives, that trust was a prerequisite for risk-taking and engagement. Many described how repeated interactions with facilitators and peer groups helped them redefine institutional relationships and gain confidence in voicing needs.

Political capital use reflected the instrumental use of participatory tools by local actors to gain legitimacy, resources, or leverage within political hierarchies. This demonstrated how participatory mechanisms are not neutral—they are often repurposed by actors to navigate or challenge existing power structures. This aligns with adaptive development theories, which argue for recognizing the political economy of learning and feedback loops (Ramalingam et al., 2014). It was dominant in the Philippines. Participants, especially local officials and community leaders, referred to participatory research and data collection as strategic assets. Tools like community scorecards and monitoring reports were used to claim attention from provincial or national institutions. Participation was valued not just for internal empowerment but for its external signaling value.

Institutional navigation also described how participants understood their role as navigating, adapting to, or resisting institutional constraints, particularly in opaque or exclusionary systems. It highlighted that even well-designed participatory platforms can be reinterpreted based on local political and cultural norms. This reveals a tension between formal inclusivity and real-world power asymmetries, a key explanation for null effects in variables like resource adequacy (X6).

It was especially important in Bangladesh, where women in agriculture projects framed their engagement not in terms of empowerment alone, but as calculated negotiation within patriarchal and bureaucratic spaces. They spoke of needing to “work around the rules” or engage selectively with officials. In Tanzania as well, youth participants explained how formal structures, such as cooperatives or producer groups, required constant adaptation to existing gatekeepers, local elites, or rigid administrative processes.

Lastly, the theme of co-production platforms captures instances where participants perceived themselves as active shapers of project design, decisions, or evaluation, moving beyond consultation into meaningful co-creation. In practice, this referred to co-production that reflected a high-trust, low-hierarchy engagement model. Its presence supported the quantitative finding that adaptive learning (X5) and stakeholder framing (X1) were significant predictors of success. This is the epistemic dimension of participation, where whose knowledge counts becomes a central axis of impact.

Co-production of platforms was most evident in Kosovo, in which participants emphasized that forums were not just ceremonial; they allowed for deliberative dialogue, joint priority-setting, and consensus-building. This created a sense of procedural justice and ownership. In Tanzania, co-production was visible in horticultural interventions where farmer-led innovation, youth-driven planning, and gender-sensitive adaptation were not only allowed but institutionalized.

Comparative discussion: pathways of systemic change

This article is best understood as a methodological contribution to the ongoing paradigm shift from linear, technocratic models of evaluation toward dynamic, participatory, and systems-based approaches. The six cases serve not as final proof points but as illustrations of how such a shift reconfigures research practice, insight generation, and institutional design.

Taking a step back from the individual findings, the most vital contribution of this article lies in its service to the broader methodological and conceptual reorientation currently underway in the field of development evaluation. Rather than offering six case-specific results, this study seeks to demonstrate what it means to operationalize complexity and systems thinking through participatory, context-responsive, and co-evolutionary research practice. The six cases serve not as bounded “country comparisons” but as living laboratories of this paradigm shift, each showing what such a transition demands in terms of design adaptations, epistemological commitments, and institutional recalibration.

The study provides concrete illustrations of how shifting from linear, input–output models to dynamic systems approaches transforms not only the framing of research questions but also the role of stakeholders, the nature of evidence, and the meaning of impact. Through its integration of PAR, sensemaking, and selective use of regression analysis, it advances methodological guidance on how to manage the tensions between rigor and relevance, standardization and flexibility, and institutional inertia and learning. The challenges and insights experienced, ranging from translation across epistemologies to issues of power asymmetry and symbolic legitimacy, are offered here as both challenges and opportunities for practitioners, funders, and policymakers attempting similar reconfigurations.

This study, thus, advocates for research and evaluation practices that are as adaptive and relational as the systems they seek to understand and influence. In doing so, it hopes to support those working at the frontlines of institutional innovation, especially where traditional regimes remain dominant but increasingly inadequate for achieving sustainable and inclusive development. The findings of this research point out systemic change through three lenses: behavioral, structural, and normative shifts. These dimensions represent distinct but interdependent levels through which research-led interventions influence inclusive and sustainable development outcomes. By triangulating regression findings, sensemaking data, and site-specific qualitative narratives, this study advances the literature by addressing key gaps: (i) a lack of granular comparative analysis of institutional change, (ii) insufficient empirical grounding of behavioral adaptations in participatory models, and (iii) limited theorization of normative transformation across diverse cultural contexts.

Behavioral shifts: co-design and adaptive learning

Behavioral shifts represent the most proximate and observable dimension of systemic change in development processes. These are changes in how individuals and groups engage, make decisions, and adapt their practices in response to new information, relationships, or tools. This study finds that such shifts were most clearly catalyzed through the mechanisms of co-design and adaptive learning approaches that allow stakeholders to move from passive participation to active ownership.

Across the six countries, Ethiopia and the Philippines are examples of the most substantive behavioral transformation. In Ethiopia, agricultural extension workers and women's cooperatives engaged in structured reflection sessions and peer-to-peer dialogues, facilitated by local researchers and NGOs. These sessions were not ancillary but built into the project's core delivery structure. Participants described refining strategies for livestock diversification and seasonal irrigation planning based on experiential feedback. These behaviors reflect the principles of double-loop learning, where actors not only adjust actions but reconsider underlying assumptions—a hallmark of adaptive systems (Argyris, 1976; Williams and Brown, 2018).

Similarly, in the Philippines, community members in disaster-prone areas, particularly in regions affected by typhoons and floods, utilized research outputs (e.g., flood risk maps, needs assessments) not just for awareness but as tools to negotiate with local authorities. Local leaders framed evidence as a means to justify their demands for budget reallocation and prioritized infrastructure. This practice exemplifies what the literature terms strategic appropriation of data, where behavioral agency is exercised in politically situated ways (Marcelo et al., 2016).

In contrast, the experience in Bangladesh and Tanzania reveals the limits of behavioral change when adaptive structures are underdeveloped. In Bangladesh, despite extensive NGO presence and training programs, the absence of localized control over digital monitoring tools restricted community feedback. Participants often lacked the capacity—or perceived legitimacy—to propose changes midstream. This reflects critiques from Angeli and Montefusco (2020) that adaptive systems can fail when digital inclusion and decision-making are decoupled. Similarly, in Tanzania, although horticulture-based livelihood initiatives were implemented widely, extension officers described a top-down delivery style with limited space for participant-led iteration. Bureaucratic rigidity and fear of reprimand for deviation from protocol were cited as barriers, echoing Howard et al.'s (2021) observations on incentive misalignment within hierarchical development systems.

The regression analysis provides further empirical validation of these patterns. As shown in Table 4, the predictors X5 (adaptive learning) and X1 (co-design of framing) were statistically significant in at least four of the six countries, with odds ratios generally ranging from 1.50 to 1.92. This suggests a strong and consistent association between participatory behavioral practices and the likelihood of successful systemic outcomes. In countries like Ethiopia, Albania, and the Philippines, where participatory framing was operationalized early in the research cycle, the odds of a project achieving measurable institutional or normative impact increased markedly.

Importantly, these findings also advance the scholarly conversation by providing rare cross-country evidence for claims that are often asserted but seldom quantified. Much of the literature on co-design and learning (e.g., Chambers, 1997; Westley et al., 2017) emphasizes principles but lacks comparative empirical backing. This study addresses that gap by linking behavioral mechanisms directly to observed outcomes across varied governance and cultural contexts.

Moreover, the qualitative sensemaking process informed not just that behavioral change occurred, but how it was experienced and interpreted by participants. In Albania, young ICT trainees described digital platforms as “an escape from clientelism,” signaling not only a new skillset but a shift in political consciousness. In Kosovo, community members cited improved confidence in engaging with municipal authorities after participating in framing workshops. These accounts reveal that co-design is not only a design method—it is a relational practice that builds cognitive, emotional, and political capacity.

Structural shifts: institutional alignment and collaborative networks

Structural shifts involve long-term transformations in how institutions function, how policies interact, and how organizations collaborate. They represent the “rules of the game” (North, 1990) that either constrain or enable systemic change. In the context of this study, structural change was operationalized through policy alignment (X8) and networked collaboration (X7), two variables that consistently influenced whether research processes translated into embedded, durable outcomes.

Among the six countries, Bangladesh and Albania demonstrated the strongest structural change outcomes. In Bangladesh, the integration of project monitoring and evaluation (M&E) tools within district-level (upazila) planning cycles enhanced local ownership and responsiveness. Local administrators reported that evidence generated by the research teams helped structure resource allocation for land leasing governance and other services, contributing to long-term shifts in budgetary accountability. This aligns with the work of Andrews et al. (2017), who stress the importance of building “capability traps” into bureaucracies through iterative feedback systems.

In Albania (rreth), cross-sectoral ICT employment initiatives provided a model for institutional collaboration. The involvement of ministries, municipal offices, civil society organizations (CSOs), and youth groups fostered horizontal coordination that persisted beyond the lifespan of the intervention. Interviewees noted that government uptake of participatory digital tools (e.g., employment portals, certification tracking) changed not only administrative routines but also inter-ministerial communication practices. These findings align with Borrás and Edquist (2013), who argue that institutional coherence and horizontal policy coordination are key enablers of system innovation in development.

Kosovo also showed emerging forms of structural transformation, particularly in the economic development and rural inclusion sectors. Here, CSO–government collaboration focused on integrating local business priorities into municipal planning. While not yet institutionalized into national policy, this cooperation marks an important transition from donor-driven programming to embedded, local governance-led planning processes. These types of “meso-level coalitions” are frequently cited as precursors to broader structural change (Geels and Schot, 2007).

By contrast, the Philippines showed the challenges of institutional lock-in. Despite strong technical outputs from disaster resilience research, fragmented mandates between national agencies and local government units (LGUs), combined with frequent staff turnover, have weakened coordination. Several respondents described stalled initiatives due to unclear ownership or conflicting regulations. This reflects Arthur's (1989) theory of increasing returns, where path-dependent systems reinforce suboptimal equilibria, and North's (1990) claim that institutions tend to persist even when ineffective, due to sunk costs and political resistance to reform.

The regression results substantiate these qualitative findings. Policy alignment (X8) was a statistically significant predictor of impact in five of the six countries, with odds ratios between 1.87 and 2.10 (see Table 4). This variable was particularly influential in Albania, Ethiopia, and Bangladesh—countries where institutional relationships between research implementers and public administrators were strong from the outset. Moreover, collaborative networks (X7) showed positive associations in countries like Kosovo and Bangladesh, where inter-organizational relationships were either institutionalized or leveraged through formal coordination platforms.

Importantly, diagnostics such as Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) remained below 2.5 for all variables, indicating that structural indicators operated independently of behavioral ones. This is conceptually important: structural shifts do not simply emerge from changed behavior—they must be deliberately cultivated, politically negotiated, and technically supported. The findings thus support the position of Westley et al. (2011), who argue that multi-level transitions require both enabling structures and active institutional entrepreneurs to overcome lock-in and inertia.

Additionally, this study contributes to the literature on absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990) by showing that systems with pre-existing channels for feedback, such as Bangladesh's local government planning committees or Albania's ICT hubs, were more capable of translating research into embedded institutional processes. Conversely, systems with fragmented authority or poor retention (e.g., the Philippines) failed to absorb even high-quality research due to organizational instability.

Normative shifts: gender equity and social recognition

Normative change refers to the transformation of socially shared values, perceptions of legitimacy, and expectations about roles and behavior. In development practice, these shifts are essential but complex, as they touch on how people interpret identity, power, and recognition. As theorized by North (1990) and refined through sensemaking frameworks (Weick, 1995; Maitlis and Christianson, 2014), norms are not merely regulatory. They are deeply emotional and relational, maintained through symbolic practices and community consensus. This study adopts this conceptual lens to examine how development interventions influenced gender roles, social visibility, and symbolic legitimacy across six diverse contexts.

Findings from this study reveal that normative change was the most uneven of the three domains assessed (in addition to behavior and structures). It is more difficult to quantify and more sensitive to context than behavioral or structural shifts. Nevertheless, powerful shifts did emerge in Ethiopia and Bangladesh, where gender-responsive interventions were explicitly designed to reshape social hierarchies. In Ethiopia, for example, women participating in agricultural cooperatives reported that their roles evolved from supportive laborers to knowledge holders, individuals whose decisions carried weight within their communities (Uraguchi, 2010). This transition was not only about increased participation; it was also about symbolic recognition, or what Johnson et al. (2016) describe as emotional legitimacy, which is the moment when a person's contributions are publicly acknowledged as valid and valued.

Similarly, in Bangladesh, projects targeting land governance and farming systems made deliberate efforts to include women in training, monitoring, and planning processes. As women gained skills and voice in these forums, they were increasingly accepted as decision-makers. This reconfiguration of gender roles was particularly meaningful in rural areas, where patriarchal structures often constrained female agency. The data show that this visibility of women being seen and heard in public forums was itself a form of transformation, confirming the work of Tavenner and Crane (2019) as well as Carter et al. (2014) on the role of public acknowledgment (e.g., bilateral donors) in norm change with what evidence and outcomes.

By contrast, in Tanzania and Kosovo, attempts to shift gender or inclusion norms encountered resistance, and normative gains remained marginal. In these settings, local stakeholders framed development interventions, especially those focused on women's leadership or minority inclusion, as externally imposed. In Kosovo, the entrenchment of political polarization and ethnic tensions created barriers to trust, while in Tanzania, traditional leaders questioned the legitimacy of changing gender roles, citing cultural and religious norms. These findings align with Duran (2019) and Lončar (2016), who argue that normative interventions that lack cultural resonance or local ownership can provoke backlash, rather than transformation.

The results of the logistic regression offer partial empirical support for these patterns. Gender-sensitive indicators (X4) showed statistically significant associations with positive project outcomes in Ethiopia and Bangladesh (β = 0.47 and β = 0.46, respectively), but not in Tanzania or Kosovo. Yet this statistical variability does not diminish the relevance of the shifts observed. As sensemaking interviews confirmed, even in countries where gender-sensitive indicators (X4) lacked statistical significance, symbolic actions, such as women publicly moderating meetings or young people questioning hierarchy, represented critical steps toward social realignment.

From a theoretical perspective, these findings make three important contributions. First, they extend sensemaking theory by showing that normative change is not only about framing new meanings, but also about earning recognition within emotionally charged social orders. Second, the study challenges the adequacy of universal indicators for norm change, highlighting that transformation is often context-dependent, non-linear, and mediated through symbolic performances. Third, it reinforces the idea that normative legitimacy emerges relationally, from trust, endorsement, and repeated social interactions, not solely from access or inclusion.

From a practical standpoint, the study emphasizes that symbolic infrastructure is as important as institutional architecture. In other words, projects must not only provide roles for underrepresented actors; they must build spaces where these actors can be seen, heard, and affirmed. This includes designing participatory processes that make emotional and social shifts visible (Cornwall, 2008), such as storytelling platforms, public forums, and peer-to-peer exchanges. Moreover, interventions need to be culturally embedded, drawing on local idioms of legitimacy and aligning with community-held values to avoid perceptions of imposition or political manipulation.

Conclusion: practical implications for research-to-impact pathways