Introduction

The United Nations predicts that by 2050 over 2 billion people will be living in urban areas (United Nations, 2021). This increase is precipitated in large part by the growth of smart cities, these are developments in urban living where transnational networks have emerged as partly denationalized platforms for intertwined global capital and labor mobility and these cities offer international career opportunities and professional and social networks (De Falco, 2019). Smart cities are view by some to be the future of urban living and the UAE and Dubai in particular has focused heavily on smart city development to foster economic growth and make the city an attractive place to live and work (Lima, 2020). Smart cities are often a focus of expatriate talent, and Dubai is no different with approximately 90% of its population being expatriates (Government of Dubai, 2019). The Dubai Government has been very successful in increasing Foreign Direct Investment by acquiring quality international talent (Haak-Saheem, 2020) and quality of life, in which smart cities play a part, is an increasingly important factor in international talent acquisition (Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2020) particularly in the UAE (Kokt and Dreyer, 2018).

These cities are enabled by the development in ICT, big data, and AI (Ranchordás, 2020) and enable much greater access and interaction to city services for citizens, while making greater efficiencies through the use of technology. These cities' services encompass a wide range of domains (Giffinger and Gudrun, 2010); economy (covering business competitiveness and entrepreneurial activity), people (looking at social and human capital), governance (covering participation and public engagement), mobility (looking at transport and ICT), environment (around natural resources and sustainability), and finally, living (concerned with quality of life). These six domains form the basis of most definitions of smart cities (Camero and Alba, 2019; Erdogan, 2021). This complexity provides a diverse range of city experiences, which have not fully been examined through the lens of consumer behaviors.

Given the increasing demand for global talent, the apparent rise in smart cities and the complexity of the smart city phenomenon it is becoming increasingly important to understand what is perceived to be valuable to an expatriate to work in a smart city context to ensure the cities are developed in a way that is most fitting for expatriates in this public sector setting.

It is important to remember that value is highly subjective in nature (Holbrook, 2006; Cluley and Radnor, 2020). Value cannot be created in isolation and requires multiple actors to co-create it (traditionally customer and service provider), and furthermore, that value can only be realized through usage (Vargo and Lusch, 2008). It is in that individualistic and context-specific setting that the experience and behavior of smart city users is examined in this data.

Turning to the context of smart cities, while there is much written on the smart cities generally, little has been focused on the value co-creation area in what is a public sector space (Ojasalo and Kauppinen, 2024), nor users' perception of that value (El-Haddadeh et al., 2019). The aforementioned subjective nature of value and the individuals' behavior and experience within that value context also needs further exploration (Eggert et al., 2019). The needs and preferences of users are also under explored (Wirtz et al., 2021) as is the behavioral relationship between individual and service network (Peronard and Ballantyne, 2019). Value creation within smart cities and other public sector areas are increasingly being termed public value, to contrast from the more traditional private sector value creation. Public value is somewhat under researched (Cavallone and Palumbo, 2019; Hansen and Fuglsang, 2020; Yap et al., 2021), partially in relation to ICT (Verma, 2020).

Finally, public value in relation to expatriates; this is a group whose ICT-related behavior and experience have not been fully explored, particularly in relation to the smart city context (Arifa et al., 2021).

The aims of this research are to redress the gaps identified above, firstly to explore value co-creation in smart cities, which is overlooked in the current literature, secondly to examine the behavior of users in a public sector digital environment and finally to add to the current body of knowledge on expatriates' value creation experience.

Method

Data was collected using an online survey method via the SurveyMonkey application between the 8th and 26th of September 2023 in Dubai, UAE. As a result, a total of 445 responses were collected for further analysis, this sample size was considered sufficient as determined by a sample calculator (RoaSoft, 2004), which details a sample size of 385 based on an expatriate population the size of 2 million in Dubai, a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 5%. Given that the sample had more than exceeded the 385 respondents required the 3-week data collection period was deemed sufficient.

The survey employed existing measurement constructs of information exchange, convenience, touchpoints, city experience, dimensions of value, and perceived service value. Information exchange relates to the quality of the content of the site or app, examining the suitability of the information for the user's purposes, e.g. accuracy, format and relevancy (Barnes and Vidgen, 2003). Convenience has long been examined in relation to services, and this is no different in the smart city realm. Convenience examines the extent to which the user interface (e.g., app, website, service center) is simple, intuitive, user friendly, time saving and effortless (Chang and Chen, 2008). Touchpoints is a slightly newer concept, it concerns itself with any point at which a customer interacts with the service provider across multiple channels and, therefore, is similar to service encounters (Jaakkola and Terho, 2021). The city experience focuses on the overall satisfaction experienced by users based on purchase or interaction and consumption experience (Verhoef et al., 2002). The four dimensions of value developed by Sweeney and Soutar (2001) have been widely used to examine aspects of value creation. The four dimensions are functional value (performance/quality), functional value (price/value for money), emotional value and social value. Quality can be defined broadly as superiority or excellence, as such perceived quality can be defined as the consumer's judgment about a product or service's overall excellence or superiority. In terms of price/value for money this construct concerns itself with the utility derived from the product due to the reduction of its perceived short term and longer-term costs. Emotional value derives from the product or service's ability to arouse feelings or affective states. Emotional value examines the associated feelings when participating with a service. The social value construct examines the utility derived from the product's ability to enhance social self-concept. The construct of perceived service value is newer to the literature and is focused in part on e-government activity, it is a mediator between service quality and citizens' continuous-use intention. The intention to use is a consequence of service quality, service value, and satisfaction (Li and Shang, 2020).

Responses were captured through 7-point Likert scales for analysis purposes. The selection of constructs was based on a detailed examination of current literature in the field examining those constructs that had been widely used by other studies, which provided confidence in their suitability as well as their relevance to the topic at hand.

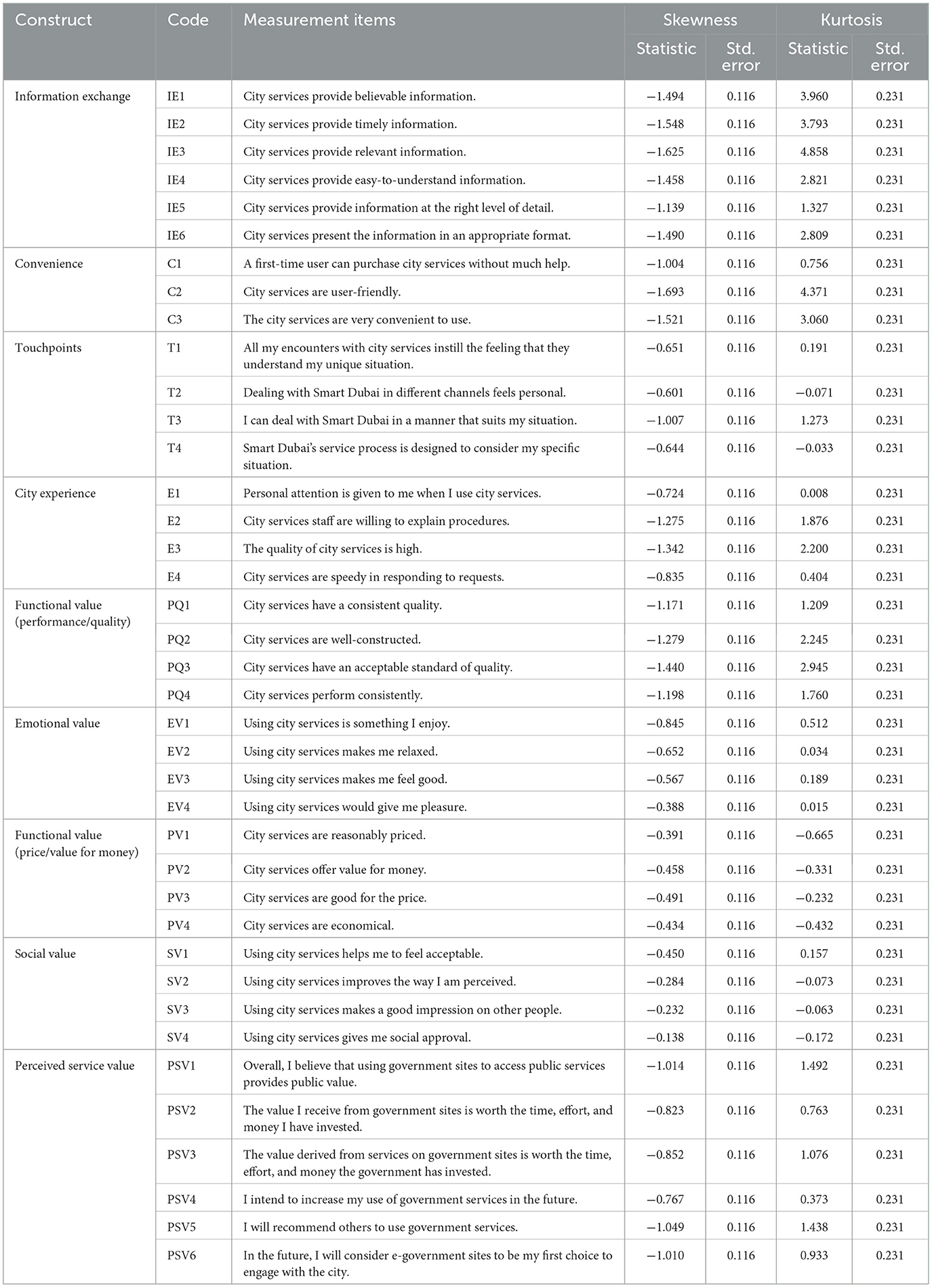

Table 1 shows the detailed measurement items for all nine constructs. Minor adaptations were made to some of the measurement items of each construct to reflect the smart city context in some areas. Additionally, Table 1 shows the normality of the dataset using skewness and kurtosis values. Skewness examines the symmetry of distribution within a dataset, ensuring even distribution of data; suitable values should be between −2 and +2, whereas kurtosis looks at the flatness of the data, showing consistency rather than peaks and troughs. Suitable values should be between −7 and +7 (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 2010). Based on the recommended criteria, the results confirm that the dataset is normally distributed, providing confidence to proceed with further reliability and validity tests.

Data description

Data characteristics

The survey's demographic data reveals a diverse respondent pool. The majority of participants were female (60.4%), followed by males (37.5%), with a small percentage (2.0%) preferring not to disclose their gender. In terms of age, over half of the respondents (55.1%) were between 18 and 24 years old, while 14.6% were aged 25–34, 14.4% were 35–44, 10.3% were 45–54, 4.5% were 55–64, and only 1.1% were 65 or older. Regarding expatriate experience, 62.9% had been expatriates for over 10 years, whereas 21.8% had spent 0–3 years abroad, 9.2% between 4–7 years, and 6.1% between 8–10 years. Regionally, the largest proportion of respondents came from the Subcontinent (59.0%), followed by Europe (17.0%), Africa (9.8%), the Americas (4.2%), the Middle East (4.5%), Oceania (2.0%), and Asia (3.5%).

Education levels varied, with nearly half (47.6%) holding a bachelor's degree, 34.2% possessing a postgraduate qualification, 17.5% having completed high school, and a small fraction (0.7%) only reaching middle school. Employment status showed that 43.8% were students, 38.9% were employed full-time, 7.6% worked part-time, 4.5% were self-employed, 2.2% were homemakers, and 2.9% were unemployed. In terms of monthly income, the majority (60.2%) earned < 20,000 AED, while 9.7% earned between 20,001 and 25,000 AED, and smaller percentages fell into higher income brackets, with 9.4% earning above 50,000 AED. This data provides a comprehensive overview of the survey respondents' demographic background.

Reliability and validity assessment

To confirm the reliability and validity of the dataset, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was first conducted with AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures). It is a statistical software used for structural equation modeling (SEM) that is particularly useful for conducting reliability and validity tests, as it allows researchers to assess measurement models through CFA (Arbuckle, 2019). As a result of the CFA, the goodness of fit indices (χ2/df = 2.337, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.937, NFI = 0.895, IFI = 0.937, and RMSEA = 0.055) shows that the measurement model demonstrates a good fit with data (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988; Hu and Bentler, 1999). Specifically, χ2/df (Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom) values between 2 and 3 suggest a reasonable model fit (Kline, 2016). CFI (Comparative Fit Index) and IFI (Incremental Fit Index) values above 0.90 generally indicate a good fit by comparing the proposed model to a null model (Byrne, 2016). However, IFI values slightly below 0.90 may still be considered acceptable, particularly in complex models or when sample sizes are limited (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2016). NFI (Normed Fit Index) values approaching 0.90 also indicate an acceptable fit (Bentler and Bonett, 1980), while RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) values below 0.06 suggest a close approximation of model fit to the population data (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

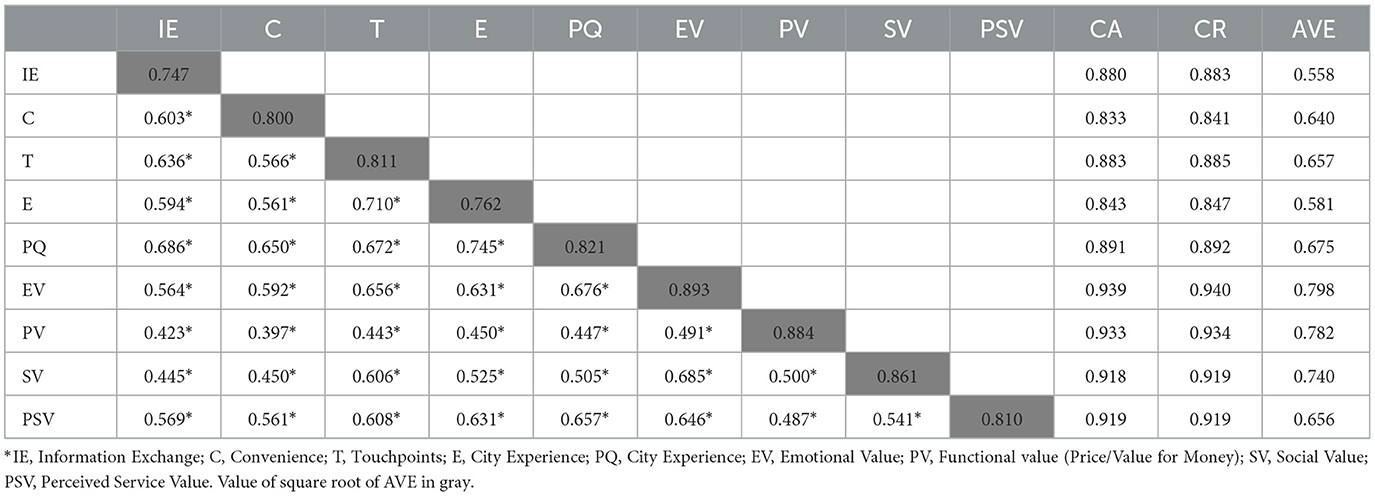

In addition, further reliability and validity tests were undertaken, and the results are shown in Table 2. The Cronbach's Alpha (CA) coefficients for all the constructs exceed 0.80, suggesting high internal consistency of the multiple measurement items of each construct (Taber, 2018). The composite reliability (CR) values for all the constructs are also >0.80, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values exceed 0.50. The results confirm the reliability and convergent validity. Lastly, as shown in Table 2, the lowest value of the square root of AVE is greater than the highest correlation coefficient, confirming the dataset's discriminant validity. The reliability and validity test results suggest the adequacy of the dataset for further inferential analysis (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Discussion

Implications

The dataset offers a comprehensive view of how expatriates perceive value creation in the public sector within a smart city context, making it a valuable resource for a broad range of research. It would benefit scholars to use this data set when looking at perceptions of value within a public service setting both on and offline, as well as those studying the behavior of expatriate workers or global talent. It can be applied to studies on value co-creation, public sector service provision, and the factors that attract global talent, such as expatriate workers. Additionally, it is relevant to researchers examining consumer behaviors in online service contexts.

The dataset itself provides insight to both city managers and academics who can turn their attention to improving public sector value co-creation in relation to expatriates, understanding the importance of information sharing via ICT and making it clear to users. The data demonstrates the importance of convenience in smart city services as well as the need for suitable touchpoints at which to engage with services. The data also provides insight into the city experience more generally in relation to the offline elements of the services. The data examines value more generally by using the established four dimensions of value which provides further evidence of their reliability while giving further insight into value in the expatriate and public value arenas. Turning to perceptive service value which is designed to focus on e-government this construct provides further evidence of the overall value created in a smart city environment, while providing further validation of this newer concept. Furthermore, as the dataset represents individuals of diverse national backgrounds living outside their countries of origin, it would be particularly useful for those investigating the expatriate experience.

Limitations

Despite the potential use of the dataset, certain limitations of the data should be considered. The data was collected through a cross-sectional quantitative survey, which may constrain the depth of insights. To enhance understanding, future research could incorporate qualitative methods to provide a more comprehensive perspective on value creation for expatriates in the context of smart cities. Additionally, as the data was collected exclusively in Dubai, UAE, the generalizability of the findings may be limited.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: Mendeley, doi: 10.17632/yp3mw4k46y.1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Middlesex University Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arifa, Y. N., El Baroudi, S., and Khapova, S. N. (2021). How do individuals form their motivations to expatriate? A review and future research agenda. Front. Sociol. 6, 1–17. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.631537

Bagozzi, R. R., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 16, 74–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327

Barnes, S. J., and Vidgen, R. (2003). Measuring web site quality improvements: a case study of the forum on strategic management knowledge exchange. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 103, 297–309. doi: 10.1108/02635570310477352

Bentler, P. M., and Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 88, 588–606. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (multivariate applications series). New York: Routledge.

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. 3rd ed. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315757421

Camero, A., and Alba, E. (2019). Smart City and information technology: a review. Cities 93, 84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.014

Cavallone, M., and Palumbo, R. (2019). Engaging citizens in collective co-production: insights from the Turnà a N'Domà (back to the future) project. TQM J. 31, 722–739. doi: 10.1108/TQM-02-2019-0040

Chang, H. H., and Chen, S. W. (2008). The impact of customer interface quality, satisfaction and switching costs on e-loyalty: Internet experience as a moderator. Comput. Human Behav. 24, 2927–2944. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2008.04.014

Cluley, V., and Radnor, Z. (2020). Rethinking co-creation: the fluid and relational process of value co-creation in public service organizations. Public Money Manag. 41, 563–572. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2020.1719672

De Falco, S. (2019). Are smart cities global cities? A European perspective. Eur. Plann. Stud. 27, 759–783. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1568396

Eggert, A., Kleinaltenkamp, M., and Kashyap, V. (2019). Mapping value in business markets: an integrative framework. Ind. Market. Manag. 79, 13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.03.004

El-Haddadeh, R., Weerakkody, V., Osmani, M., Thakker, D., and Kapoor, K. K. (2019). Examining citizens' perceived value of internet of things technologies in facilitating public sector services engagement. Gov. Inf. Q. 36, 310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.09.009

Erdogan, M. (2021). A new fuzzy approach for analyzing the smartness of cities: case study for Turkey. Sakarya University J. Sci. 25, 308–325. doi: 10.16984/saufenbilder.799469

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 38–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

Giffinger, R., and Gudrun, H. (2010). Smart cities ranking: an effective instrument for the positioning of the cities? ACE 4, 7–26. doi: 10.5821/ace.v4i12.2483

Government of Dubai (2019). Number of Population Estimated by Nationality, BMC Public Health. Available online at: https://www.dsc.gov.ae/Report/DSC_SYB_2019_01_03.pdf (accessed November 19, 2020).

Haak-Saheem, W. (2020). Talent management in Covid-19 crisis: how Dubai manages and sustains its global talent pool. Asian Bus. Manag. 298–301. doi: 10.1057/s41291-020-00120-4

Hair, J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multvariate Data Analysis. 7th edn. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Person Educational International.

Hansen, A. V., and Fuglsang, L. (2020). Living labs as an innovation tool for public value creation: possibilities and pitfalls. Innov. J. 25, 1–21.

Holbrook, M. B. (2006). Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: an illustrative photographic essay. J. Bus. Res. 59, 714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.01.008

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jaakkola, E., and Terho, H. (2021). Service journey quality: conceptualization, measurement and customer outcomes. J. Serv. Manag. 32, 1–27. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-06-2020-0233

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (4th ed.). 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Kokt, D., and Dreyer, T. F. (2018). Expatriate mentoring: the case of a multinational corporation in Abu Dhabi. SA J. Human Resour. Manag. 16, 1–11. doi: 10.4102/sajhrm.v16i0.974

Li, Y., and Shang, H. (2020). Service quality, perceived value, and citizens' continuous-use intention regarding e-government: Empirical evidence from China. Inf. Manag. 57:103197. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2019.103197

Lima, M. (2020). Smarter organizations: insights from a smart city hybrid framework. Int. Entrepr. Manag. J. 16, 1281–1300. doi: 10.1007/s11365-020-00690-x

Ojasalo, J., and Kauppinen, S. (2024). Public value in public service ecosystems. J. Nonprofit Public Sector Market. 36, 179–207. doi: 10.1080/10495142.2022.2133063

Peronard, J. P., and Ballantyne, A. G. (2019). Broadening the understanding of the role of consumer services in the circular economy: Toward a conceptualization of value creation processes. J. Clean. Prod. 239:118010. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118010

Ranchordás, S. (2020). Nudging citizens through technology in smart cities. Int. Rev. Law Comput. Technol. 34, 254–276. doi: 10.1080/13600869.2019.1590928

RoaSoft (2004). Sample size calculator. Available online at: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed November 12, 2021).

Rodríguez-Sánchez, J. L., González-Torres, T., Montero-Navarro, A., and Gallego-Losada, R. (2020). Investing time and resources for work–life balance: the effect on talent retention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:1920. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061920

Sweeney, J. C., and Soutar, G. N. (2001). Customer perceived value: the development of a multiple item scale. J. Retailing 77, 203–220. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00041-0

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of cronbach's alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 48, 1273–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Vargo, S. L., and Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 36, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

Verhoef, P. C., Franses, P. H., and Hoekstra, J. C. (2002). The effect of relational constructs on customer referrals and number of services purchased from a multiservice provider: does age of relationship matter? J. Acad. Market. Sci. 30, 202–216. doi: 10.1177/0092070302303002

Verma, S. (2020). Value co-creation through value-in-use experience: a netnographic approach. South Asian J. Manag. 27, 156–175.

Wirtz, B. W., Müller, W. M., and Schmidt, F. W. (2021). Digital public services in smart cities – an empirical analysis of lead user preferences. Public Organ. Rev. 21, 299–315. doi: 10.1007/s11115-020-00492-3

Keywords: perceived value, consumer psychology, smart cities, value co-creation, expatriates

Citation: Brown M and Han J (2025) Perceptions of value from smart city Dubai, an expatriate view: a data report. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1595460. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1595460

Received: 20 March 2025; Accepted: 11 June 2025;

Published: 01 July 2025.

Edited by:

Hussein Mohammed, Edith Cowan University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jucu Sebastian, West University of Timişoara, RomaniaMarcin Zygmunt, KULeuven, Belgium

Copyright © 2025 Brown and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew Brown, bS5icm93bkBtZHguYWMuYWU=

Matthew Brown

Matthew Brown Jeongsoo Han

Jeongsoo Han