- 1VIT-AP University, Amaravati, India

- 2Graphic Era Deemed to be University, Dehradun, India

- 3Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, New Delhi, India

Introduction: The creation of housing inclusivity is significant for uplifting the weaker section of society. The government has always taken relevant steps in developing nations to promote inclusivity in finance and housing for equitable national growth. This inclusion depends upon many parameters. There is a lack of comprehensive research addressing how existing housing policies and designs systematically exclude marginalized groups, highlighting a critical gap in achieving housing inclusivity. The present research focuses on creating a framework that integrates all such parameters to provide insight into which parameters should be given more importance and which should be given less importance during policy implications.

Methods: To achieve this, the research technique of PLS-SEM (Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling) was employed in the present study. Mathematical calculations in the tool named SMART PLS 4 were based on the conceptual model to ensure the credibility of the framed model. The analysis was employed on the responses collected from the respondents using a constructed research instrument, which involves convenience sampling techniques and snowball sampling.

Results: Ultimately, it can be inferred that government policies have the most significant impact on the financial improvement of low-income households, followed by perceptions of housing affordability and access to affordable housing finance.

Discussion: These findings have practical implications for government policy formulation, focusing on infrastructural development through loan assistance and regulatory support. Additionally, it is essential to provide tax incentives and necessary subsidies to the more vulnerable sections of society. Additionally, it is crucial to focus on financial empowerment through the cognition of efficient debt management to raise creditworthiness, as insinuated by the present research.

1 Introduction

The burgeoning exigencies of urban agglomerations, particularly within rapidly developing economies, have thrust the provision of affordable housing into the forefront of socio-economic discourse (Zhou and Shaw, 2004). The significance of affordable housing finance resides in its capacity to act as a pivotal instrument for ameliorating socio-economic disparities. Also, if the growth of the urban economy is inclusive in nature, the availability of finance for the development of housing infrastructure reduces the exclusionary consequences of market-driven housing dynamics., This dynamism facilitates the creation of stable residencies in the economy by empowering vulnerable sectors of society (Grover and Grover, 2014). Housing inclusivity enriches societal mobility and contributes to the compaction of location-based separation, eventually cultivating a more impartial urban infrastructre, where the necessities of residency do not intercept the accomplishment of civic and financial obligations (Sorensen and Chen, 2022).

Urban inclusivity, as a socio-spatial paradigm, symbolizes a paramount imperative for facilitating impartial and endurable urban growth (Flintrop, 2011). It is necessary to understand the walls that are built to separate rich and poor cannot be brought down without eliminating discrimination. For creating an equitable civilization, it is essential to nurture a resilient metropolitan fabric with multifarious demographic comrades. There is a need to establish a systematic framework that promotes housing inclusivity and empowers weaker sections of society, and the present research is an attempt to achieve this goal (Sorauf, 2024). It is critical to have an economic system where, despite the economic and social background, everyone is able to relish fair access to indispensable aids, prospects, and benefits, thereby encouraging a milieu facilitative to collaborative prosperity (Bozeman, 1974).

The present study covers the research gap of measuring the impact of access to affordable housing finance (Squires, 2008), financial empowerment of low-income households (Birkenmaier and Curley, 2009), housing affordability perception (Yap and Ng, 2018) and government policy support (Landis and McClure, 2010) on housing inclusivity (Landis and McClure, 2010). Housing finance, through the provision of accessible credit, catalyzes financial empowerment by enabling asset accumulation, fostering economic stability, and facilitating participation in wealth generation, thereby transforming domiciliary investment into a conduit for socio-economic mobility (Schwartz, 2013). Housing affordability perception encapsulates the subjective cognitive appraisal of the financial burden associated with securing adequate residential accommodations, a multifaceted construct influenced by individual economic circumstances, socio-cultural norms, and prevailing market dynamics, which collectively shape the perceived accessibility and commensurability of housing costs relative to disposable income, thereby modulating residential decision-making and impacting socio-economic well-being (Alev et al., 2015). The subjective construal of housing affordability, as a cognitive metric, wields significant influence over socio-economic decision-making, impacting residential mobility, financial planning, and overall well-being, thereby shaping individual and collective perceptions of urban economic equity (Tribe, 2010). Research on the impact of affordable housing finance on urban inclusivity is necessitated by the imperative to elucidate the causal nexus between financial instruments and socio-spatial equity, thereby informing policies aimed at mitigating urban fragmentation and fostering inclusive development (Revie and Bryson, 2004).

India’s rapidly urbanizing landscape, characterized by stark socio-economic disparities and a burgeoning affordable housing deficit, renders it an unparalleled locus for investigating the impact of housing finance on urban inclusivity, offering a unique opportunity to scrutinize the efficacy of financial instruments within a context of acute developmental challenges. The Indian urban housing finance milieu manifests as a complex nexus of burgeoning demand, evolving financial instruments, and persistent infrastructural deficits, characterized by rapid urbanization, precipitating an escalating need for residential units, particularly within the affordable housing segment, where projections from entities like the CII and Knight Frank India indicate a cumulative demand reaching 31.2 million units by 2030, valued at approximately INR 67 trillion; this demand, concentrated predominantly (95.2%) within the affordable sector, is met by a financial landscape comprising Scheduled Commercial Banks (SCBs) and Housing Finance Companies (HFCs), with the latter demonstrating significant market penetration within the estimated INR 13 trillion affordable housing loan market, where loan reliance is notably higher than in premium housing; governmental initiatives such as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) catalyze development, yet challenges persist, including the necessity for updated regulatory frameworks, particularly regarding the RBI’s definition of affordable housing within priority sector lending, the impact of rising EMI/Income ratios, and the need for innovative strategies like public-private partnerships and advanced construction technologies, all while the housing finance market is poised for significant expansion, fueled by escalating demand and positive government policies, promising job creation within the sector.

India’s urban inclusivity remains an intricate paradox wherein rapid monopolisation exacerbates socio-spatial stratification (Starr and Yilmaz, 2007), relegating economically disenfranchised cohorts to peripheralised enclaves despite proliferating governmental interventions, policy frameworks, and financial mechanisms aimed at fostering equitable access to housing (Bogin et al., 2021), infrastructural amenities, and participatory urban governance, thereby necessitating a recalibrated synthesis of systemic affordability, regulatory coherence, and socioeconomic integration to dismantle entrenched exclusionary paradigms (Evans, 2012).

The present research compares the impact of access to affordable housing, housing affordability perception, government policy’s financial empowerment of low-incomes households, and housing inclusivity. As per previously published research, these variables were found to significantly impact the financial empowerment of low-income households and housing inclusivity. By the application of structural equation modelling the comparison of influence of these variables will be measured with the help of standardized beta and whether this influence is significant or not will be measured with the help of Bootstrapping.

2 Literature review

Housing affordability is the ability of households to secure suitable housing without compromising their financial stability (Jurčišinová et al., 2025), and its significance lies in its direct impact on individual well-being, economic stability, and social equity within communities (Kim et al., 2025). Housing affordability has a direct influence on housing inclusivity (Tao et al., 2025). Housing inclusivity refers to the phenomenon of having access to housing infrastructure for marginalised sections of the economy (Thorns, 1988).

H1: Access to Affordable Housing Finance impacts the Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households.

Informed by Chernoff and Cheung (2024) exposition of infrastructural deficits, institutional lacunae, and data limitations impeding Indigenous economic advancement, the provision of affordable housing finance emerges as a pivotal mechanism for enhancing financial self-sufficiency among low-income households, thus substantiating the hypothesis that broadened fiscal pathways can attenuate systemic inequities and catalyze broader economic empowerment. Access to affordable housing finance is the result of several sub-factors. Majorly, it depends upon the prevailing interest rates at which house loans are available specifically to the marginalised section of society (Stutz and Kartman, 1982). Many macroeconomic factors also influence the availability of loans at the bank, which impacts the accessibility of affordable housing finance (Odeyemi and Skobba, 2022). Many a time, it is also noticed that because of weak economic background, marginalized people who fall into the low-income category are unable to become eligible for a home loan (Holme, 2022). Sometimes, the complexity of the application process also decreases the accessibility of housing finance. In the given sub-factors, housing finance becomes accessible to a person (Hromada et al., 2022).

The financial empowerment of low-income households is a significant latent variable for increasing housing inclusivity (Novoa et al., 2015). This empowerment can be achieved if an individual from a low-income household can maintain the required creditworthiness through efficient debt management by controlling their spending (Sani, 2015). Financial empowerment is also a result of income stability, which facilitates growth in the savings of marginalized people who invest judiciously in available alternatives (Sharam et al., 2015). This financial empowerment of low-income group seems to be directly influenced by affordable housing finance in the available literature.

H2: Access to Affordable Housing Finance impacts the Housing Inclusivity.

In the UK, Haycox et al. (2024) observed that housing inclusivity can be made possible if loans related to the construction and acquisition of houses can be made affordable. The research emphasised the importance of a policy framework that makes housing finance available to the public at a low interest rate. The benefit of affordability in the acquisition of how this will also have other macroeconomic benefits that can further contribute to the nation’s development (Kukk and Levenko, 2024; Saha et al., 2023).

Housing inclusivity is considered a crucial factor in financial inclusion (Simkins et al., 1992). If a developed nation can build an inclusive environment in terms of housing infrastructure, it can be inferred that there is a reasonable assessment of different economic opportunities (Linneman and Megbolugbe, 1992). To determine whether an economy has housing inclusivity, the diversity in the neighborhood can be evaluated in conjunction with the level of commodity integration. The presence of housing inclusivity not only means a person living in a house but it is also accompanied by a reasonable quality of life that further fosters social mobility (Berkhout and Hill, 1992). All these items that constitute housing inclusivity are possible if housing finance is affordable.

H3: Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households impacts Housing Inclusivity.

Housing inclusivity serves as a significant parameter for financial inclusion. Low-income households who own their own houses feel a sense of economic empowerment (Nair et al., 2020). As per research by Vijaya et al. (2018) livelihood empowerment and financial empowerment are significant parameters for housing inclusivity. The study further states that it is necessary, especially in rural areas, for a person to complete the construction of the house (Kilonzo et al., 2025). Providing a loan alone cannot be considered housing inclusivity; the loan must be sufficient to cover the complete construction of the house (Zhao et al., 2025).

H4: Government Policy Support impacts Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households.

As per the research conducted in Pakistan by a Hadar and Manos (2021), government policies are paramount for creating empowerment amongst low-income households. It is necessary that the government focus more on reducing the gap between rich and poor, and the Housing Act is a statistically significant parameter for that. Also, as per the Indian national mission on financial inclusion, the Indian government has taken many steps, such as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Ganga, 2025), to create financial empowerment in low-income households (Noreen et al., 2022). Also, the Indian government is found to be rigorously working on increasing financial inclusion through a relevant policy framework (Kaul and Raman, 2018).

Government policy support serves as a tool for economically weaker sections of society to combat financial exclusion (Aryeetey-Attoh, 1989). If government policies promote infrastructural development for low-income groups by providing loan assistance and tax incentives, inclusion becomes practical (Arnold and Skaburskis, 1989). Moreover, providing regulatory support to low-income groups in the form of subsidy programs is necessary for promoting financial empowerment and housing inclusivity (Nicholson, 1989).

H5: Government Policy Support impacts Housing Inclusivity.

The governments of developing nations are found to provide credit subsidy schemes to low-income groups to enhance housing inclusivity in their country (Kaul and Raman, 2018). The initiation of providing funds to low-income groups is always through appropriate government policy containing user-friendly terms and conditions for the people (Razin, 2022). Moreover, adequate steps must be taken for the proper execution of the policy at the ground level (Owen and Vedanthachari, 2023).

H6: Housing Affordability Perception impacts Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households.

Housing Affordability Perception is a dynamic, cognitively mediated assessment of residential financial accessibility shaped by socio-economic stratification, market volatilities, and policy-induced distortions (Hoxha, 2024). A research on Islamic finance by Wahab et al. (2016) focuses on the need to create a perception of affordability in the housing sector (Salga, 2005). The research aims to foster this perception to empower low-income households financially.

Financial empowerment and housing inclusion are possible only if there is a positive perception regarding housing affordability in the minds of people (Gan and Hill, 2009). When taking a loan for a building or acquiring a house, the first thing a low-income individual will do is conduct a cost–benefit analysis (Fisher et al., 2009). If the money going out of pocket is more than the perceived benefit of the tangible asset being purchased, it will result in a negative perception of housing affordability. It is essential to foster a positive perception in people’s minds by integrating down payment ease, reducing financial stress, facilitating housing stability (Bogdon and Can, 1997), and clarifying the differences between rental and ownership. If this perception is cultivated within the minds of marginalized people in society, the chances of financial empowerment among them will increase (Vizek, 2009; Withers, 1997).

H7: Housing Affordability Perception impacts Housing Inclusivity.

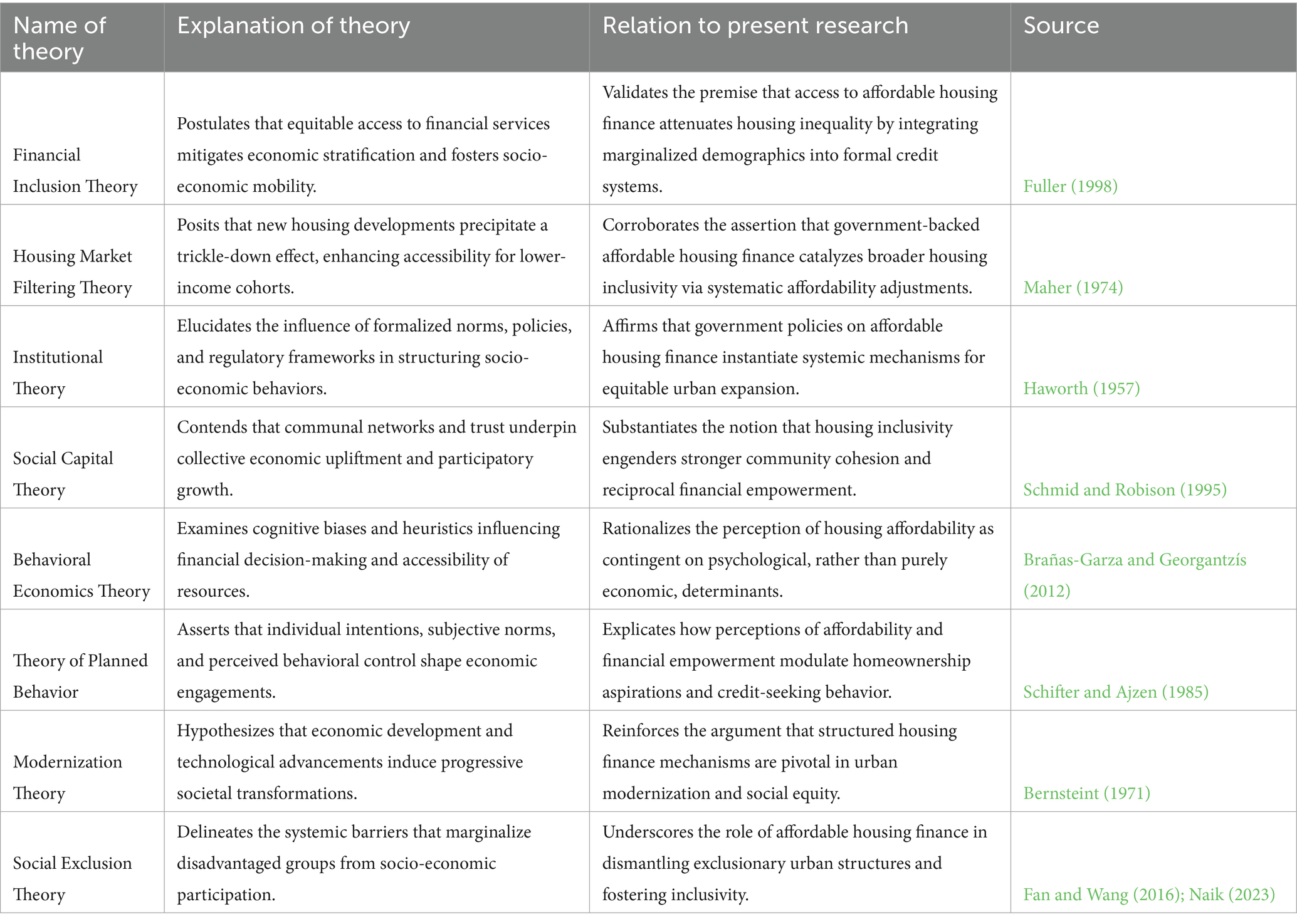

The intricate interplay between housing affordability perception and housing inclusivity manifests as a multifaceted socio-economic construct wherein subjective valuations of cost accessibility (Goidel and Gross, 1994), informed by macroeconomic indicators, policy frameworks, and socio-cultural paradigms, engender differential access to equitable habitation, thereby perpetuating spatial stratifications, socio-economic dichotomies, and systemic marginalization, as extant literature elucidates that affordability (Tang and Ma, 2018), often delineated through income-to-housing-cost ratios and broader economic indices, not only dictates material access but also shapes psychological predispositions toward residential attainability, fostering exclusionary mechanisms through perceived financial precarity (Rosén et al., 1992), institutional barriers, and cognitive biases that collectively exacerbate residential inequities, necessitating a holistic interrogation of affordability metrics, policy interventions (Robinson and Keefe, 1980), and socio-spatial dynamics to engender an inclusivity paradigm that transcends mere economic feasibility and encapsulates structural equity, distributive justice, and sustainable urban integration (Burrell, 1985; Table 1).

3 Research methodology

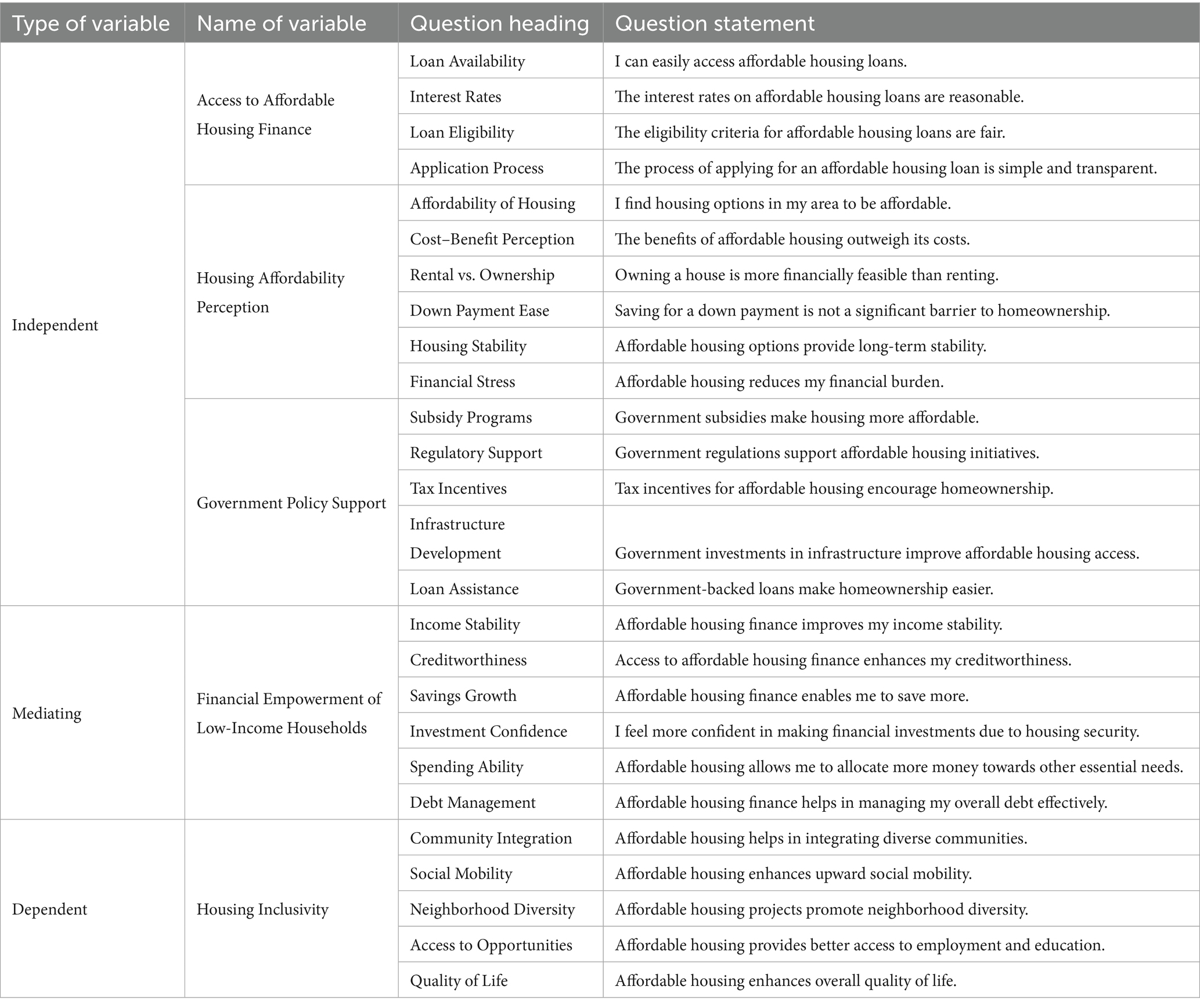

To meet the research objectives, the research instrument was developed after consulting various experts in the field, which is shown in Table 2. After the development of the questionnaire, it was circulated to a specified segment of respondents, who were identified through convenience sampling. Later, these respondents requested that the same questionnaire be filled out by people in their peer group, and snowball sampling was implemented at this stage; hence, the present research uses the integration of two sampling techniques, namely convenience and snowball sampling (Emerson, 2015).

The data is collected in the capital of India: New Delhi. New Delhi is ideal for researching housing inclusivity due to its diverse population, stark socioeconomic disparities, and rapid urbanisation challenges (Bansal et al., 2024; Chopra and Sharma, 2021; Dar and Kashyap, 2025; Srivastava et al., 2009). The present study employs convenience and snowball sampling, collecting primary data through direct personal investigation in the first phase of data collection, and subsequently uses snowball sampling. The data comprise a sample size of 422 respondents, consisting of residents of slum areas, low-income group households, tenants in informal settlements, and migrant workers. Based on the responses collected from them, a dataset was created that was uploaded into SmartPLS 4 for the application of partial least squares structural equation modelling.

The results that will be produced by the application of software comprises of 2 stages:

• PLS Algorithm

• Bootstrapping

PLS algorithm tests the reliability and validity of the framed conceptual model, whereas bootstrapping performs hypothesis testing.

Furthermore, the research extends beyond a purely quantitative analysis, seeking to elucidate the phenomenological experiences of those directly affected by affordable housing finance. It scrutinises the nuanced perceptions of beneficiaries, examining how these financial interventions modulate their sense of security, community integration, and economic mobility. By integrating perceptual data with quantifiable financial metrics, the study aims to furnish a holistic understanding of the impact of affordable housing finance on the lived realities of urban residents. The application of PLS-SEM in SMART PLS 4, enables the simultaneous assessment of multiple latent constructs, providing a rigorous framework to unravel the complex causal relationships that underpin urban inclusivity. In essence, this investigation seeks to contribute a granular, empirically grounded perspective on how financial empowerment, mediated through accessible housing finance, can catalyse equitable and inclusive urban development.

A conceptual model is articulated and established on the variables extracted from the literature review to fulfill the research objective. Firstly, the algorithm was run on the conceptual model to commence the computations and entice a conclusion in the context of research objectives to discover the path coefficient and correlation as offered in Equations 1 and 2.

It is necessary to make these 2 calculations to support further analysis which will be based on cronbach alpha, composite reliability, and average variance extracted which were calculated on the basis of Equations 3–5 respectively.

After that discriminant validity of the scale framed was tested with the help of Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations by using the values given in Equation 6. This equation is applied to the conceptual model for the purpose of confirming discriminant validity among the variables used in research.

Sample chosen to respond to the questionnaire frame, their responses then go through the calculation of sample mean to study the nature of respondents. Sample mean is calculated by the formula given in Equation 7.

Standard deviation was also calculated as per Equation 8 to measure the difference amongst the construct.

Check the acceptability or rejection of the hypothesis, t statistics and p value are used as per Equations 9 and 10, respectively.

The conceptual model’s hypothesis testing was done by bootstrapping it on the sample set of 5,000 and applying Equation 11.

4 Data analysis

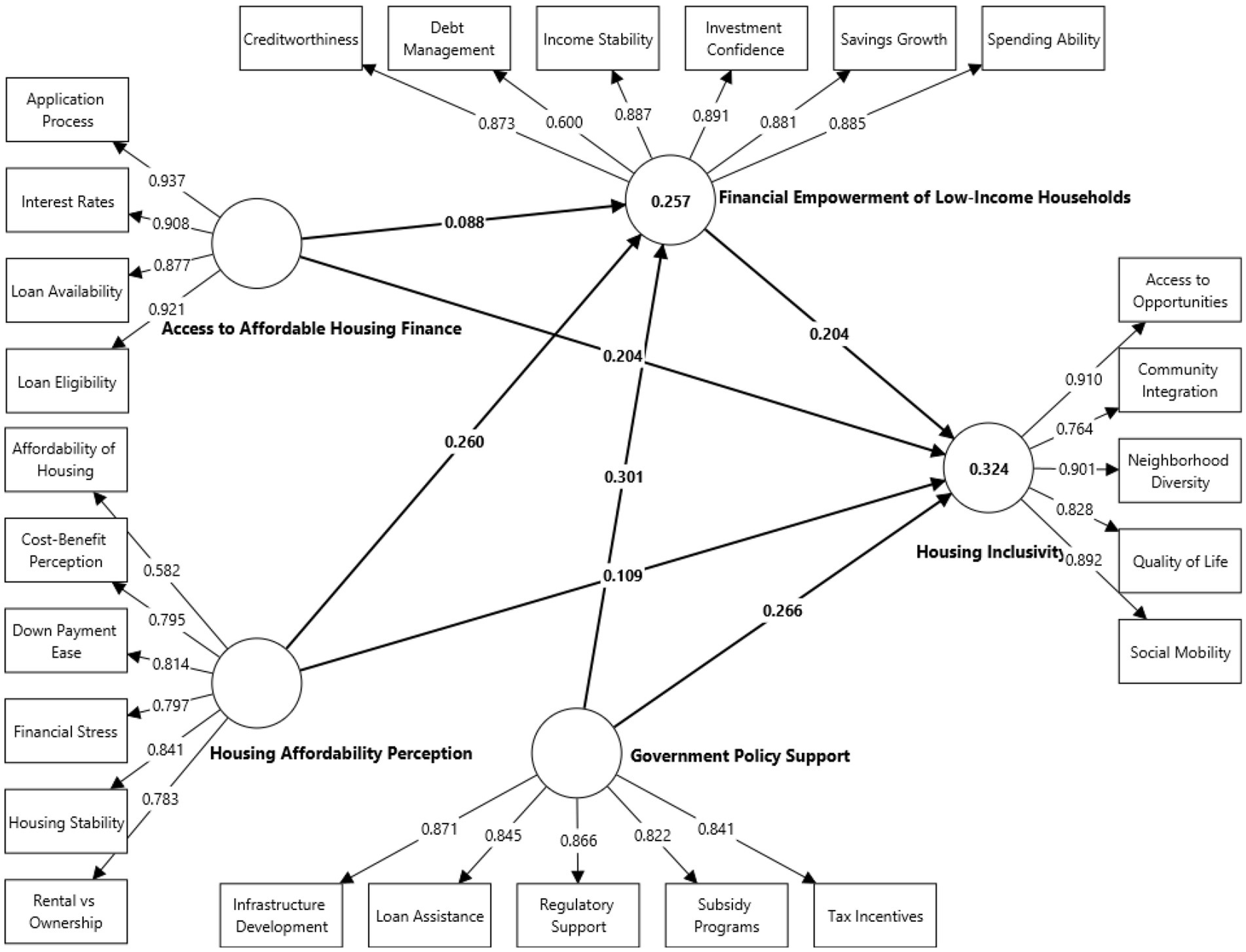

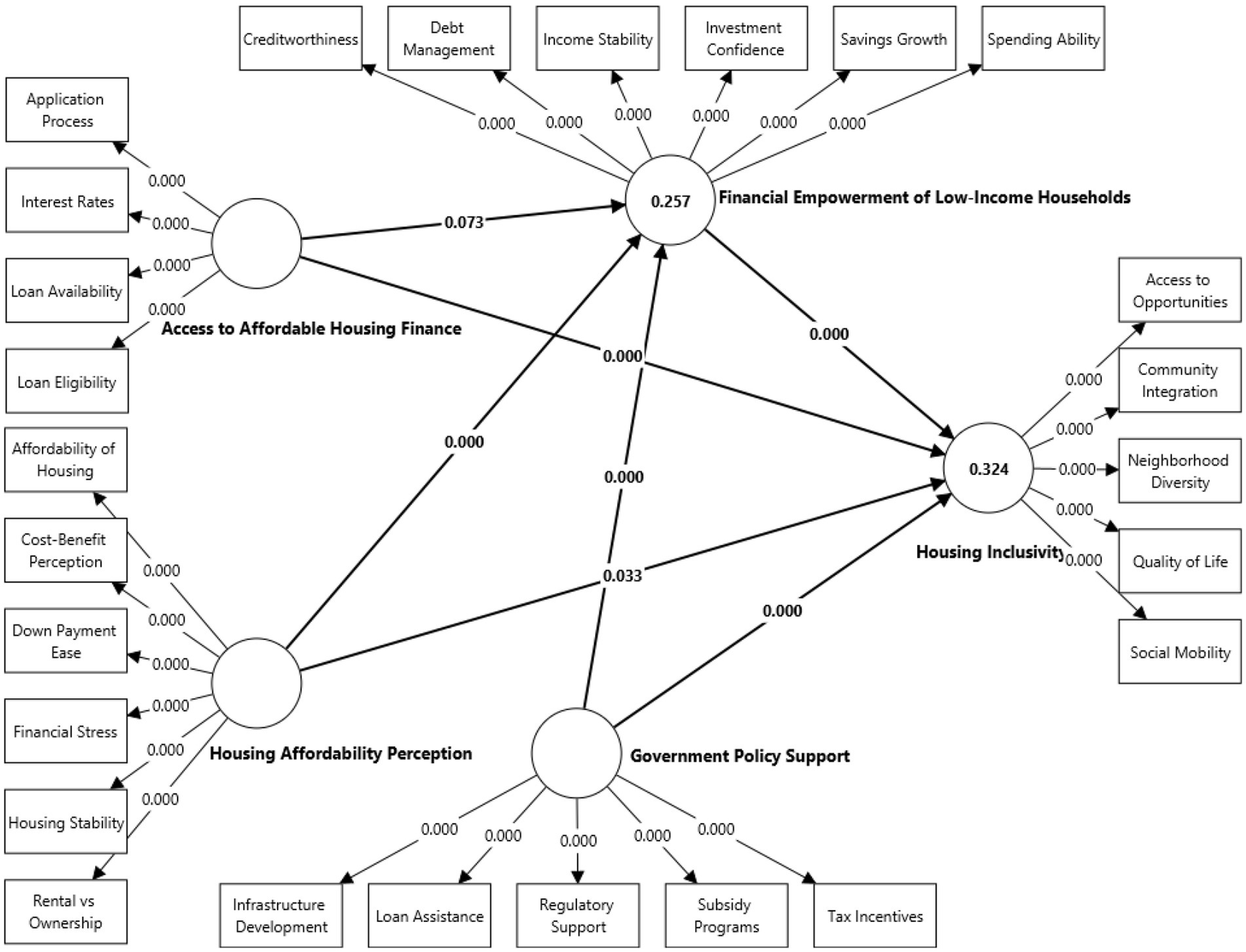

Informed by the partial least squares structural equation modeling in Figure 1 results, the diagram elucidates how “Access to Affordable Housing Finance”—anchored by factors like application processes, interest rates, and loan eligibility—exerts a direct positive influence on both “Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households” (e.g., via improved creditworthiness, debt management, and savings growth) and “Housing Inclusivity” (encompassing quality of life, neighborhood diversity, and social mobility), while “Housing Affordability Perception” (shaped by cost–benefit views, down payment feasibility, and financial stress) and “Government Policy Support” (evidenced by infrastructure development, loan assistance, and subsidy programs) intercede as additional accelerants that reinforce and synergize these relationships, ultimately generating a multifaceted framework wherein enhanced affordable finance channels, favorable housing perceptions, and enabling public policies coalesce to propel economically and socially inclusive outcomes for disadvantaged households.

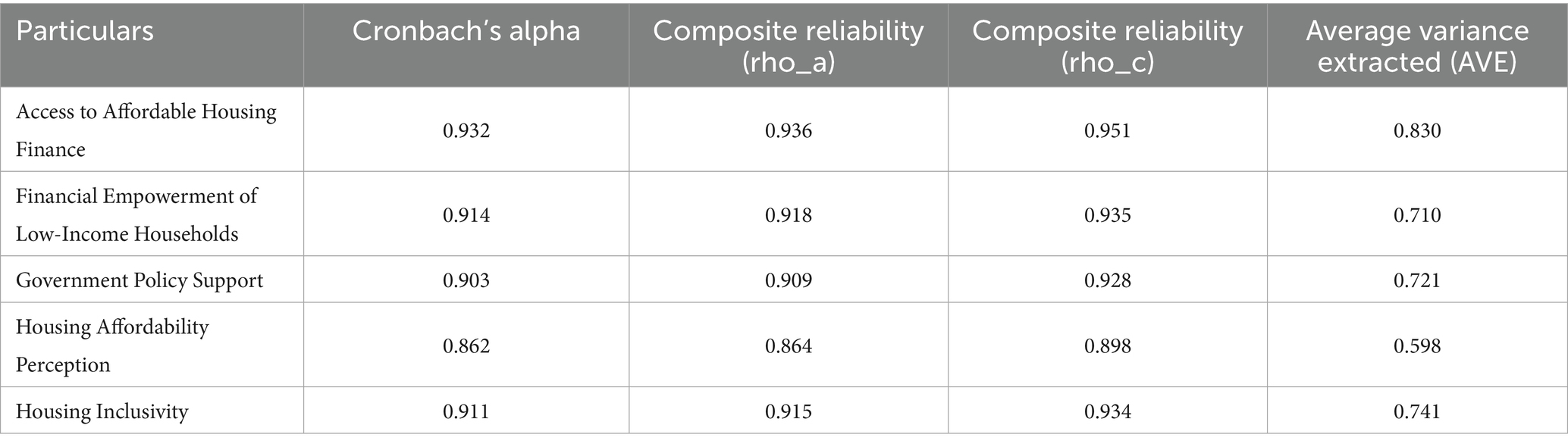

All constructs in Table 3—namely Access to Affordable Housing Finance, Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households, Government Policy Support, Housing Affordability Perception, and Housing Inclusivity—exhibit exemplary psychometric robustness (as evidenced by Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability indices significantly surpassing conventional thresholds, and AVE values well above 0.50), thereby confirming both their internal consistency and convergent validity within the measurement model.

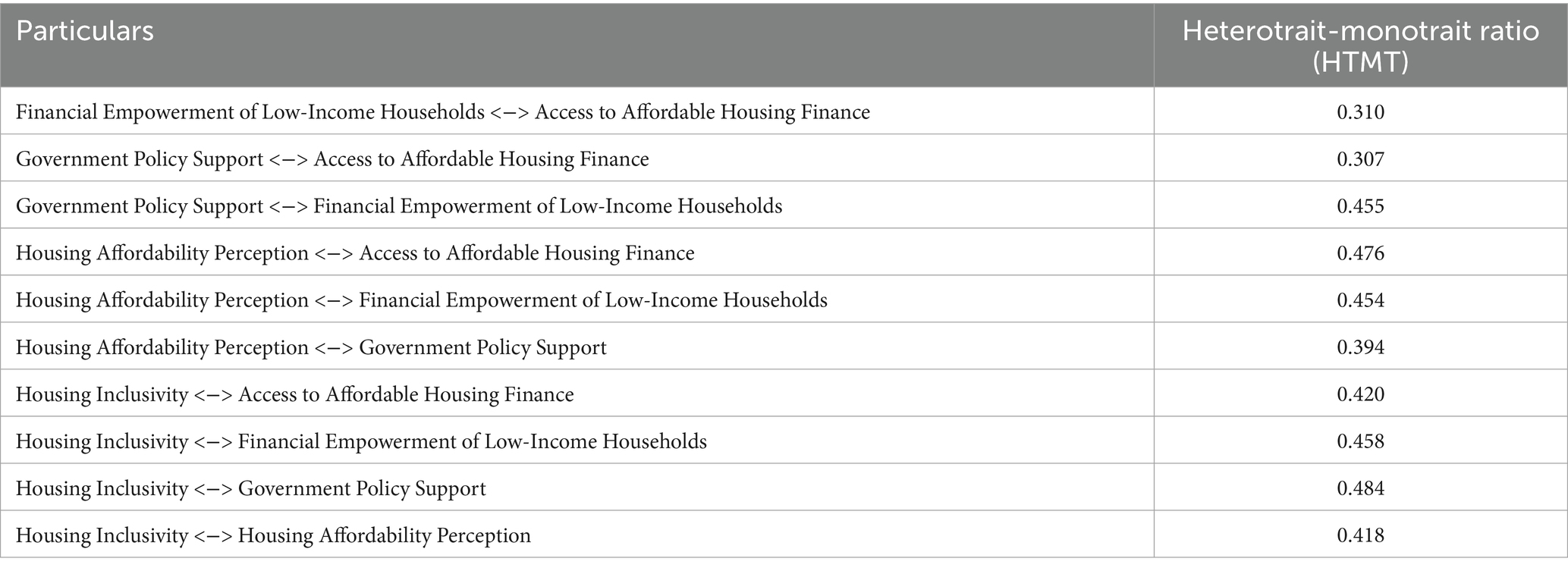

All inter-construct HTMT estimates in Table 4 remain comfortably below conventional thresholds (i.e., < 0.85), thereby bolstering the premise that each latent dimension—Access to Affordable Housing Finance, Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households, Government Policy Support, Housing Affordability Perception, and Housing Inclusivity—demonstrates robust discriminant validity within the measurement model.

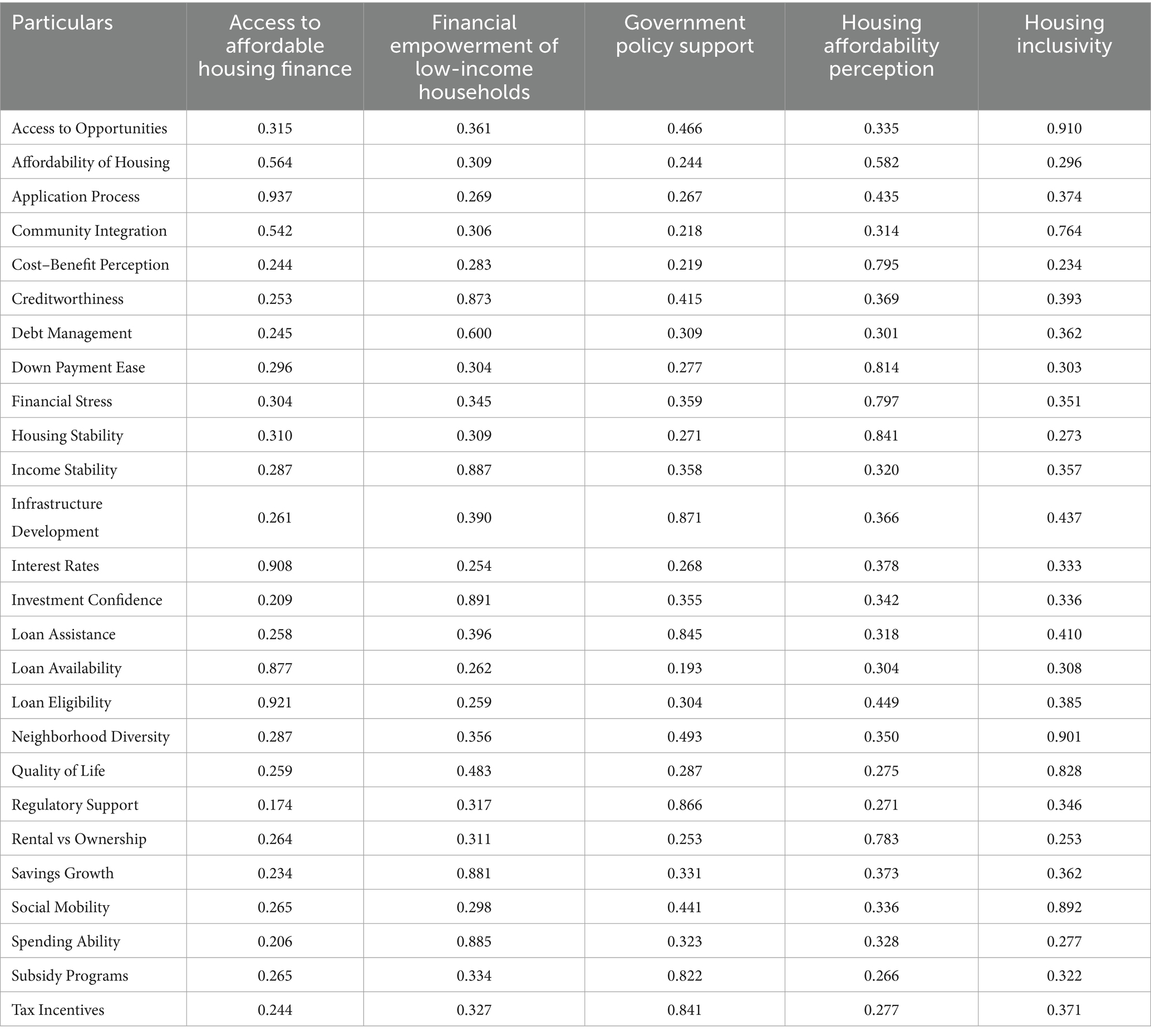

The cross-loading in Table 5 coefficients indisputably illustrates that each manifest variable predominantly saturates its respective latent construct relative to all alternative constructs, thereby corroborating the model’s convergent fidelity and discriminant robustness (Table 6).

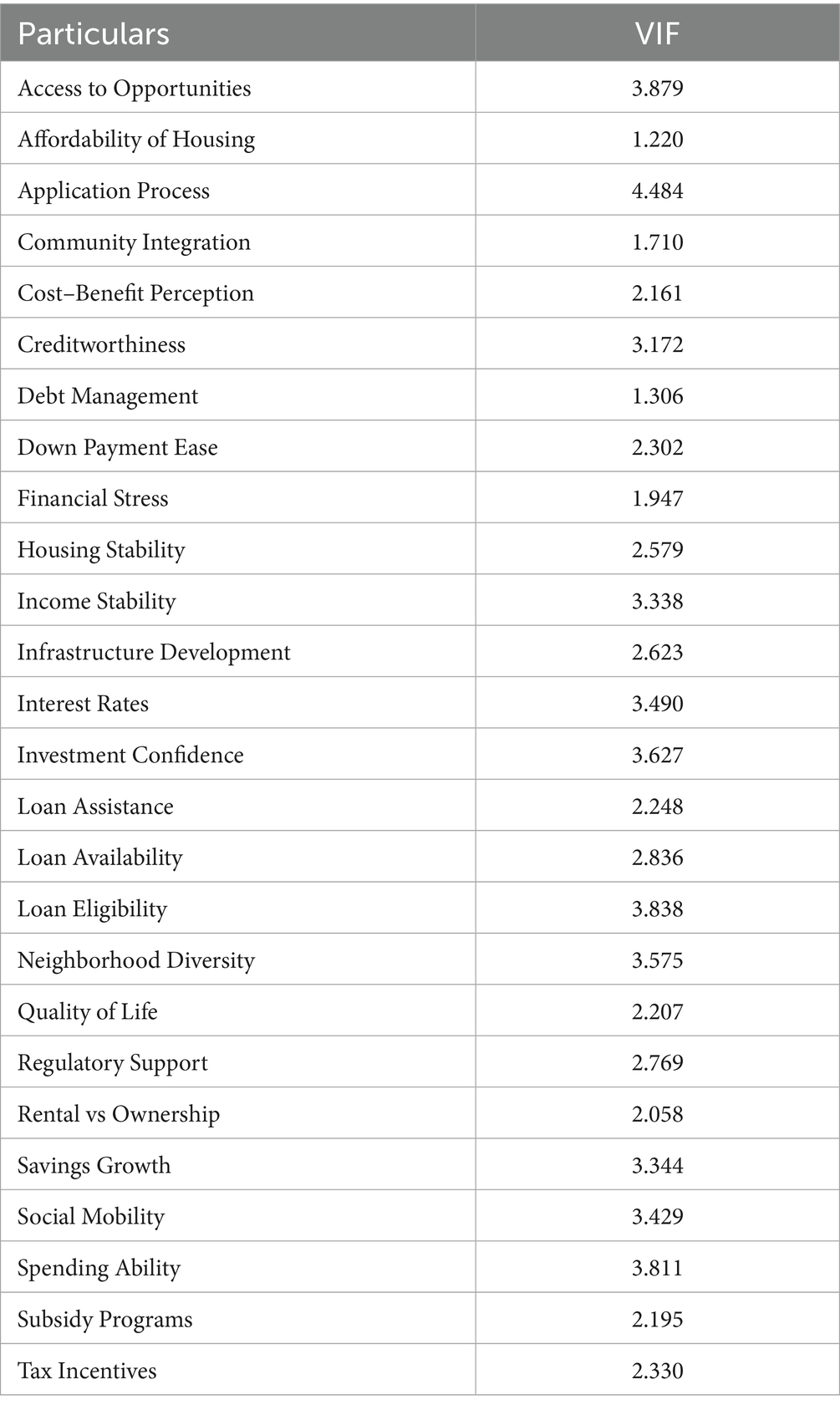

An inspection of the VIF coefficients reveals that, although a few indicators (e.g., “Application Process”) approach moderate collinearity thresholds (VIF ≈ 4–5), overall multicollinearity remains within acceptable bounds, thereby sustaining the structural integrity of the model and corroborating the validity of subsequent inferential analyses (Figure 2).

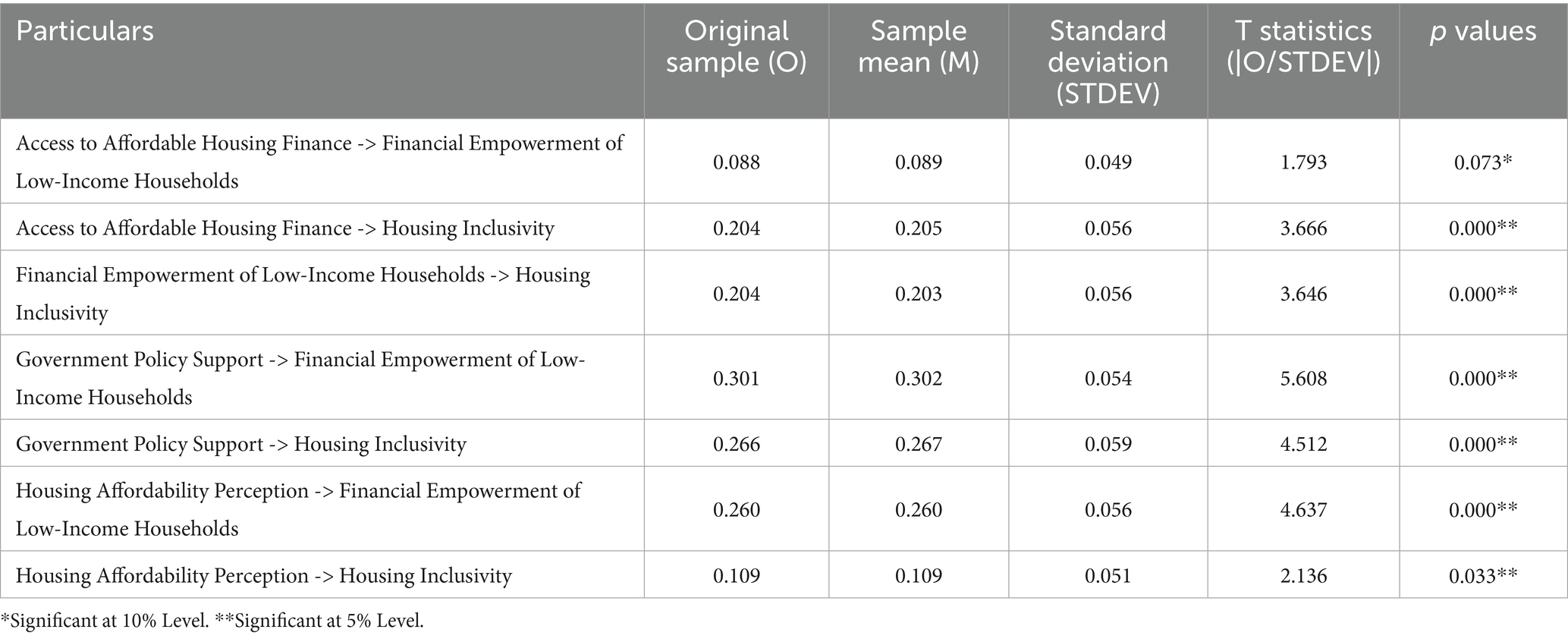

The bootstrap-based resampling procedure reveals that all hypothesized structural paths achieve statistical significance at the p < 0.05 threshold—with the singular exception of the direct linkage from Access to Affordable Housing Finance to Financial Empowerment of Low-Income Households (p = 0.073)—thereby substantiating the model’s overall predictive robustness while indicating one non-significant pathway.

Table 7 reveals insightful results from the application of bootstrapping for hypothesis testing on the conceptual model. Different relationships between variables and structural equation modelling will be helpful in policy formulation. The relationship between the variable of access to affordable housing finance and financial empowerment of low-income households is found to be statistically significant at the 10 per cent level, whereas all other relationships are found to be statistically significant at the 5 per cent level.

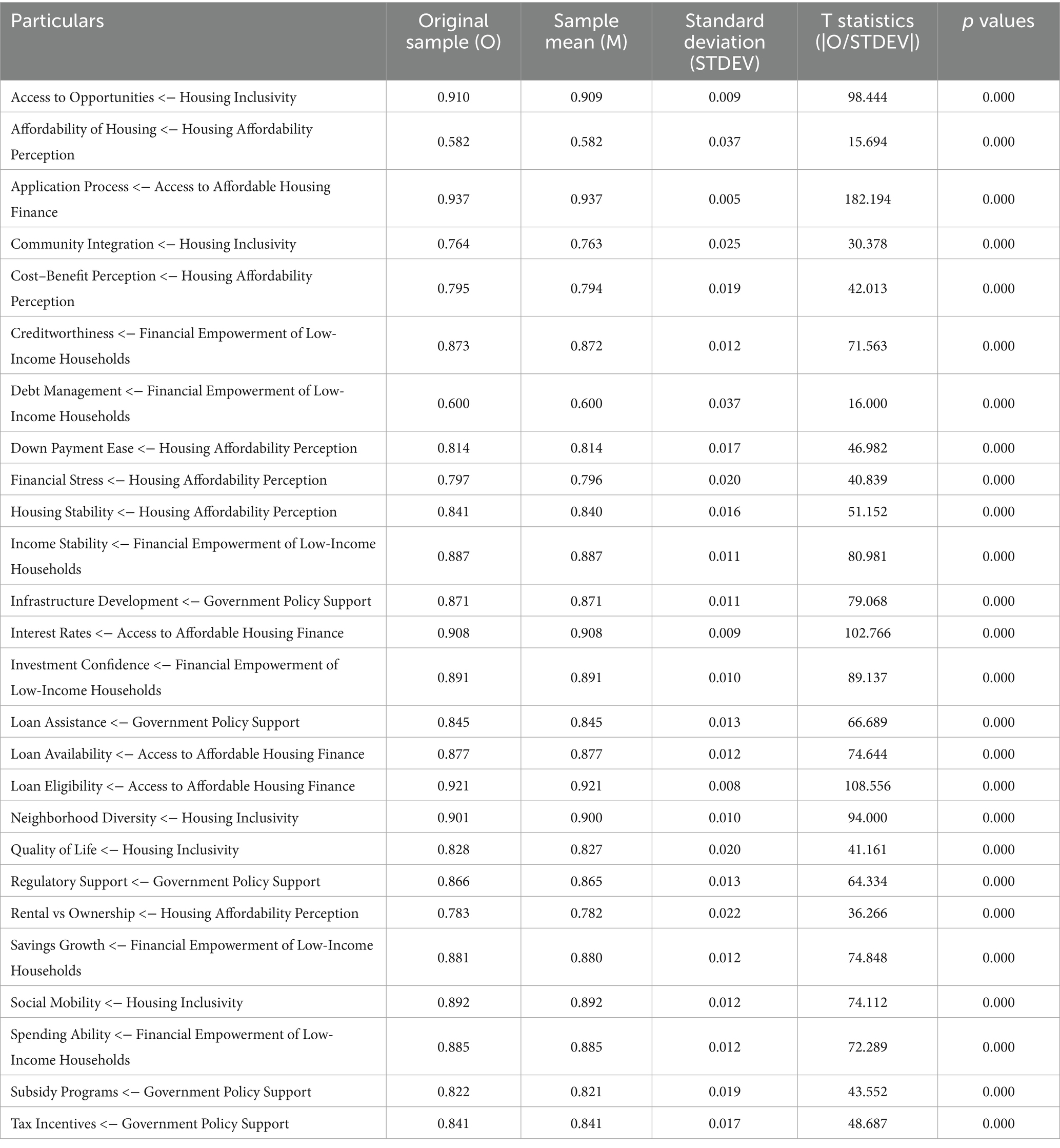

The uniformly robust factor loadings (all p < 0.001) and associated T-statistics convincingly validate each item’s alignment with its respective latent construct in Table 8, thereby reinforcing the measurement model’s convergent legitimacy and indicating that the indicators substantially capture the intended theoretical dimensions.

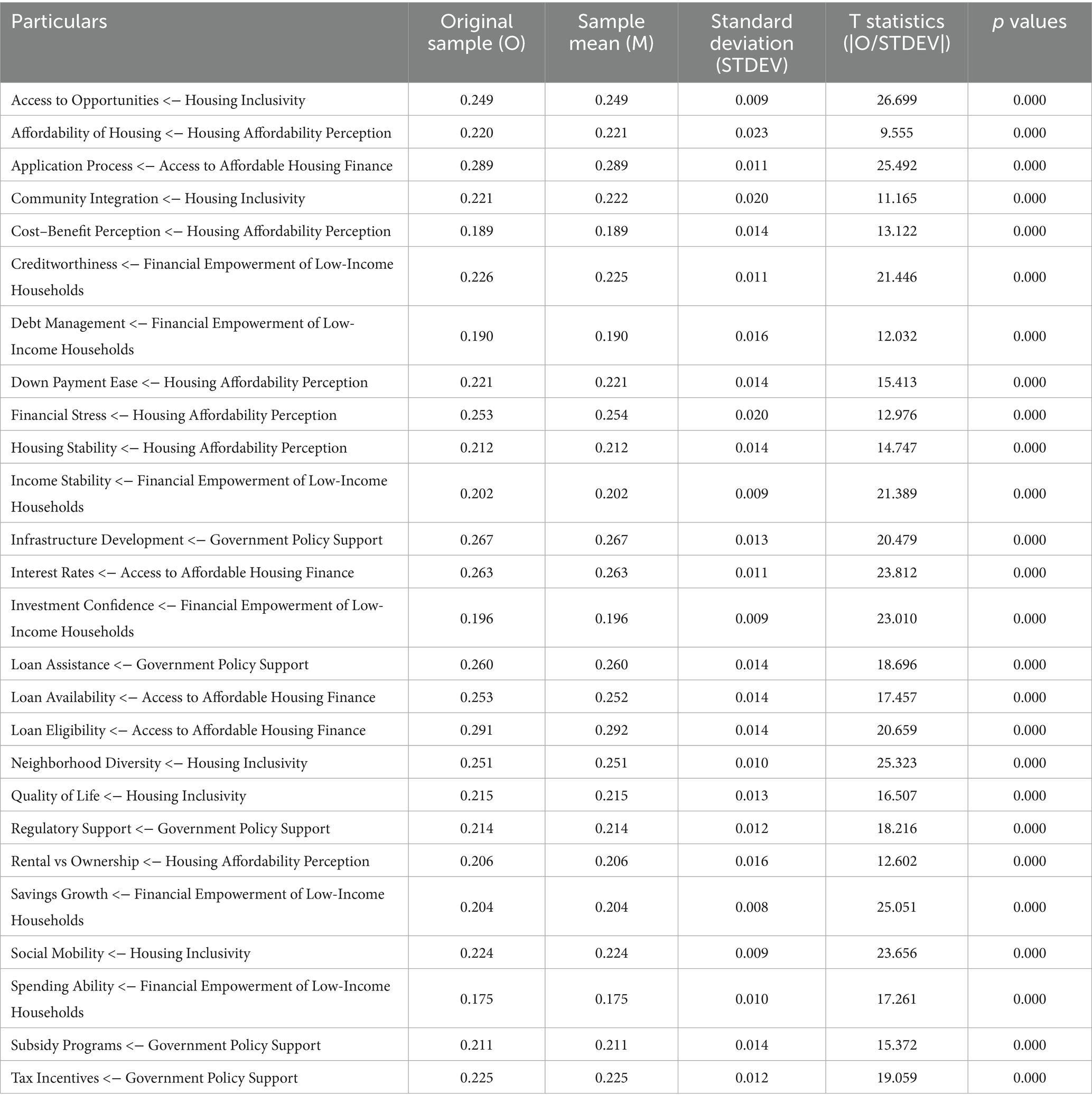

As evidenced by the uniformly significant outer weights and T-statistics in Table 9, the measurement model’s reflective specification is robustly supported, as each item demonstrably contributes meaningfully to its latent construct—indicating strong indicator reliability and further buttressing the latent dimensions’ theoretical salience through the high loadings and uniformly low p-values.

5 Discussion

The first relationship measures the impact of access to affordable housing finance on the financial empowerment of low-income households. The probability value of the relationship is 0.073, which shows a significant relationship at a 10% level of significance. This relationship is positive in nature, as the beta value in Figure 1 is 0.088. The inferential statistical examination underscores the marginally significant yet impactful positive correlation between financial accessibility in the housing sector and the economic fortification of socioeconomically disadvantaged demographics, thereby necessitating policy architects to recalibrate fiscal interventions, optimise subsidy allocations, and engineer equitable lending frameworks that amplify affordability without exacerbating systemic risk, ensuring that strategic resource distribution is empirically substantiated to maximise socioeconomic upliftment while minimising unintended market distortions.

The second segment measures the impact of access to affordable housing finance on housing inclusivity. The probability value is zero, which signifies a statistically significant impact on access to housing finance and housing inclusivity. Moreover, the relationship between the variables is positive, indicating that if the government is interested in increasing the housing inclusivity level of its country, the affordability of housing finance must be improved. These findings are parallel with the previous studies (Alkhan, 2020; Burk, 1988; Kahler, 2006).

The third relationship is between financial empowerment and housing inclusivity. Based on the statistical analysis, this relationship was also found to be statistically significant, as the probability value for the given association is also zero. Barry and Aho (2020) also draws a similar conclusion and has evidenced the significance of financial empowerment for enhancing inclusivity in the housing sector.

According to the 4th measurement model, government policy has a statistically significant impact on the financial empowerment of low-income households. The relationship between the variables is positive, and hence, it is relevant for government policy formulation. This relationship implies that government policy plays a crucial role in strengthening the weaker section of the economy. One of the basic needs for the public is housing, and to fulfil it, government policy plays a significant role. Previously published literature supports these findings (Bogin et al., 2020; Keasey and Hudson, 2007) and highlights the relevance of different elements of government policies for improving the lower sector of the populace.

The 5th association is measured between the variable of government policy support and housing inclusivity. The relationship between these variables is positive and statistically significant as the beta value is 0.266, and the probability value is zero. Based on these statistical values, it can be interpreted that if government policies are supportive in terms of infrastructural development, loan assistance, tax incentives, regulatory support and subsidy programs, it will lead to the creation of inclusivity in the housing sector of the economy. Do similar results have been witnessed in the studies conducted by Artis (1963) and Monkkonen (2019).

The 6th hypothesis measures the impact of housing affordability perception on the financial empowerment of low-income households. A statistically significant relationship has been found between the two variables, as the probability value is zero, and the relationship is positive, as the value of the beta coefficient is 0.260. There are studies that emphasise the importance of building housing affordability perception to empower the weaker sections of society (Pritchard, 2002). Housing affordability perception can be increased by reducing financial stress by generating awareness of rental versus ownership comparison, building cost–benefit perception, and generating ease in the down payment (Jarrett, 1962). Previous studies published stress empowering low-income households with adequate debt management and income stability, creating investment confidence and increasing the worthiness of the low-income section of the economy (Shukla, 2022).

Considering the 7th hypothesis, it can be interpreted that housing inclusivity can be enhanced by creating a positive perception regarding the affordability of a house. These findings parallel the previous studies such as Bennett and Loucks (1994) and Cooper (2018). Housing inclusivity is a significant variable that can be achieved by integrating items like access to opportunities, community integration, neighbourhood diversity, quality of life, and social mobility.

Ultimately, it can be inferred that government policies have the most significant impact on the financial improvement of low-income households, followed by perceptions of housing affordability and access to affordable housing finance. Correspondingly, access to affordable housing finance is statistically significant at 10% and has the least standardised beta value of 0.088. Hence, while the government plans to empower low-income households, the primary focus should be on making favourable policies for such income groups and running campaigns to create a positive perception of house affordability. Moreover, access to affordable housing finance should be considered because it also positively impacts financial empowerment. The present research provides different items to be integrated into government policies, the housing of mobility perception and access to affordable housing finance as a framework for increasing the probability of success of creating an inclusive housing infrastructure for the people.

The present study underlines significant actionable claims. According to the results, an attempt has been made to increase the financial empowerment of low-income households and enhance housing inclusivity. Upon assessing the statistical findings, it can be inferred that government policies have the most significant impact on increasing economic empowerment. This is also true in the context of housing inclusivity. Therefore, there is a need for the development of appropriate government policy support that inculcates requisite infrastructural development loan assistance, regulatory support, subsidy programs, and tax incentives. This will empower low-income households financially by increasing their creditworthiness, promoting efficient debt management, enhancing income stability, fostering investment confidence, promoting growth in their savings, and improving their spending ability. Moreover, access to affordable housing finance and perceptions of housing affordability are also statistically significant in boosting housing inclusivity. Housing inclusivity is essential and comprises access to opportunities, commodity integration, neighbourhood diversity, quality of life, and social mobility. All these elements of housing inclusivity are influenced by reasonable access to affordable housing finance, a favourable perception of housing affordability, and government policy support. It is necessary to have an actionable approach to accessing affordable housing finance by simplifying the application process, lowering interest rates, making loans available through efficient rationing, and making loan eligibility criteria more transparent. Furthermore, the perception of housing affordability depends on the level of clarity between rental and ownership, housing stability, everyday financial stress, ease of down payment, cost–benefit perception, and the affordability of housing. If all the elements are integrated Through required political intervention, the problem of reducing the gap between the rich and poor can be solved at an increasing rate.

6 Conclusion

In developing nations, housing inclusivity signifies the indispensable amelioration of socio-economic disparities through the provision of equitable domiciliary access, thereby catalysing holistic societal advancement. Enhancing governmental policy frameworks to fortify affordable housing finance accessibility, bolster financial empowerment mechanisms, and recalibrate perceptions of housing affordability is imperative for catalysing comprehensive housing inclusivity, thereby engendering a socioeconomically resilient urban landscape. The present research has provided a framework for increasing housing inclusivity, which will enhance the likelihood of success for government plans aimed at uplifting the weaker sections of society. To increase the level of housing inclusivity, the maximum focus needs to be on developing conducive government policy support for low-income groups. This government policy support takes the form of infrastructure development, loan assistance, regulatory support, subsidy programs, and tax incentives. The second most important parameter after government policy support is the financial empowerment of low-income households and access to affordable housing finance. Moreover, the perception of housing affordability also has a positive impact on statistical inclusivity in all housing. Keeping all these parameters and sub-parameters in mind, a robust framework supporting mathematical calculation 4 promoting housing inclusivity can be administered. Like other researchers, this study also faces certain limitations, including the time frame within which it was conducted and the limited scope of the area to which the respondents belong. However, this research supports the findings of similar studies conducted in various regions. This ensures an parallel structure of findings, facilitating the generalizability and universality of the results.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SNM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alev, Ü., Allikmaa, A., and Kalamees, T. (2015). “Potential for finance and energy savings of detached houses in Estonia” in Energy Procedia, vol. 78. eds. Perino, M., and Corrado, V. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Ltd.), 907–912.

Alkhan, A. M. (2020). Analysing product utilization by Islamic retail banks: the case of Bahrain Islamic bank and Kuwait finance house-Bahrain. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 10, 415–426. doi: 10.18488/journal.aefr.2020.104.415.426

Arnold, E., and Skaburskis, A. (1989). Measuring Ontario’s increasing housing affordability problem. Soc. Indic. Res. 21, 501–515. doi: 10.1007/BF00513458

Artis, M. J. (1963). Monetary policy and financial intermediaries: the hire purchase finance houses. Bullet. Oxford Univ. Inst. Econ. Stat. 25, 11–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.1963.mp25001002.x

Aryeetey-Attoh, S. (1989). Housing affordability ratios in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Yearbook Conf. Latin Am. Geograph. 15, 49–58.

Bansal, N., Narwal, M., and Prinkle, P. (2024). Determinants of patient satisfaction in healthcare industry in Delhi using PLS-SEM. J. Health Manag. 26, 743–751. doi: 10.1177/09720634231216064

Barry, T. J., and Aho, M. K. (2020). Up or down! House management and public finance theory from America’s era of Hastert. Int. J. Public Policy Admin. Res. 7, 44–57. doi: 10.18488/journal.74.2020.71.44.57

Bennett, R. W., and Loucks, C. (1994). Savings and loan and finance industry PAC contributions to incumbent members of the house banking committee. Public Choice 79, 83–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01047920

Berkhout, V., and Hill, M. (1992). Urban consolidation and housing affordability. Aust. Planner 30, 20–24. doi: 10.1080/07293682.1992.9657544

Bernsteint, H. (1971). Modernization theory and the sociological study of development. J. Dev. Stud. 7, 141–160. doi: 10.1080/00220387108421356

Birkenmaier, J., and Curley, J. (2009). Financial credit: social work’s role in empowering low-income families. J. Community Pract. 17, 251–268. doi: 10.1080/10705420903117973

Bogdon, A. S., and Can, A. (1997). Indicators of local housing affordability: comparative and spatial approaches. Real Estate Econ. 25, 43–80. doi: 10.1111/1540-6229.00707

Bogin, A. N., Bruestle, S. D., and Doerner, W. M. (2021). Correction to: How Low Can House Prices Go? Estimating a Conservative Lower Bound. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 54, 97–116. doi: 10.1007/s11146-015-9538-8

Bogin, A. N., Doerner, W. M., and Larson, W. D. (2020). Correction to: local house Price paths: accelerations, declines, and recoveries. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 58, 201–222. doi: 10.1007/s11146-017-9643-y

Bozeman, B. (1974). Review Symposium: Congress: politics and spending: the politics of finance: the house committee on ways and means, by John F. Manley. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1970. Am. Politics Res. 2, 354–355. doi: 10.1177/1532673X7400200306

Brañas-Garza, P., and Georgantzís, N. (2012). Presentation experimental and behavioral economics theory, tools and topics. Rev. Int. Sociol. 70, 9–13. doi: 10.3989/ris.2011.04.15

Burk, K. (1988). Finance, foreign policy and the Anglo-American bank: the house of Morgan, 1900–31. Hist. Res. 61, 199–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.1988.tb01060.x

Burrell, B. C. (1985). Women’s and men’s campaigns for the U.S. house of representatives, 1972-1982 a finance gap? Am. Politics Res. 13, 251–272. doi: 10.1177/1532673X8501300301

Chernoff, A., and Cheung, C. (2024). An overview of indigenous economies within Canada. Can. Public Policy 50, 364–390. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2023-053

Chopra, V., and Sharma, J. G. (2021). SEM-EDAX analysis of the soil samples of river Yamuna in Delhi region. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 20, 93–103. doi: 10.46488/NEPT.2021.v20i01.010

Cooper, M. (2018). The strategy of default: liquid foundations in the house of finance; [Fondations liquides L’abstraction financière au risque de la fuite des investis]. Multitudes 71, 46–58. doi: 10.3917/mult.071.0046

Dar, H., and Kashyap, K. (2025). Structural equation modeling (SEM) approach for envisaging the connotation among medical tourists’ satisfaction, attitude and loyalty: a case of Delhi-NCR, India. Int. J. Spa Wellness 8:5867. doi: 10.1080/24721735.2025.2455867

Emerson, R. W. (2015). Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: how does sampling affect the validity of research? J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 109, 164–168. doi: 10.1177/0145482X1510900215

Evans, E. (2012). From finance to equality: the substantive representation of women’s interests by men and women MPs in the house of commons. Representation 48, 183–196. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2012.686688

Fan, X., and Wang, J. (2016). “How social interactions demotivate customer participation in creativity tasks: from the perspective of social exclusion theory.” Proceedings of international conference on service science, ICSS, 2016-February. pp. 75–78.

Fisher, L. M., Pollakowski, H. O., and Zabel, J. (2009). Amenity-based housing affordability indexes. Real Estate Econ. 37, 705–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6229.2009.00261.x

Flintrop, J. (2011). Finance: a well-ordered house; [Finanzen: Ein gut bestelltes haus]. Dtsch. Arztebl. 108, A1295–A1296.

Fuller, D. (1998). Credit union development: financial inclusion and exclusion. Geoforum 29, 145–157. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7185(98)00009-8

Gan, Q., and Hill, R. J. (2009). Measuring housing affordability: looking beyond the median. J. Hous. Econ. 18, 115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jhe.2009.04.003

Ganga, A. (2025). Defending land rights amid urban development insights from Rajiv Awas Yojana in Visakhapatnam. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 60, 59–67.

Goidel, R. K., and Gross, D. A. (1994). A systems approach to campaign finance in U.S. house elections. Am. Politics Res. 22, 125–153. doi: 10.1177/1532673X9402200201

Grover, R., and Grover, C. (2014). The role of house price indices in managing the integration of finance and housing markets in the European union. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 7, 270–294. doi: 10.1108/JERER-02-2014-0013

Hadar, R., and Manos, R. (2021). “Government policy and financial inclusion: Analyzing the impact of the Indian national mission for financial inclusion” in Inclusive financial development eds. Ahmad, A. H., Llewellyn, D. T., and Murinde, V. (Massachusetts, in the USA: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd).

Haworth, L. L. (1957). An institutional theory of the city and planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 23, 135–143. doi: 10.1080/01944365708978242

Haycox, H., Hill, E., Finney, N., Meer, N., Rhodes, J., and Leahy, S. (2024). Housing governance and racialisation: ‘inclusivity’ in housing access and experience. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 50, 4545–4562. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2024.2344505

Holme, J. J. (2022). Growing up as rents rise: how housing affordability impacts children. Rev. Educ. Res. 92, 953–995. doi: 10.3102/00346543221079416

Hoxha, V. (2024). Examining the nexus of building regulations, urban planning, and housing prices and affordability: insights from Prishtina, Kosovo. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adap. doi: 10.1108/IJBPA-11-2023-0172

Hromada, E., Čermáková, K., and Piecha, M. (2022). Determinants of house prices and housing affordability dynamics in the Czech Republic. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 14, 119–132. doi: 10.24818/ejis.2022.24

Jarrett, F. G. (1962). Pastoral finance houses and rural credit 1949-50 to 1958-59. Aust. J. Agric. Econ. 6, 62–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8489.1962.tb00302.x

Jurčišinová, V., Forbes, C. S., Ng, J. W. J., and Želinský, T. (2025). The mediating role of financial well-being in the relationship between housing affordability and mental health. Sci. Rep. 15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-00997-1

Kahler, S. C. (2006). 2006 resolutions range from welfare philosophy to finances: seven measures to be deliberated by house of delegates. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 228, 1837–1840

Kaul, M., and Raman, T. V. (2018). Challenges in implementation of credit linked subsidy scheme under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY-CLSS). Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 9, 937–943.

Keasey, K., and Hudson, R. (2007). Finance theory: a house without windows. Crit. Perspect. Account. 18, 932–951. doi: 10.1016/j.cpa.2006.06.002

Kilonzo, H. M., Muriithi, M., and Ongeri, B. O. (2025). Drivers of housing financing in Kenya. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. doi: 10.1108/IJHMA-09-2024-0139

Kim, S., Kim, D., and Bekkers, P. (2025). Multi-family housing development in suburban communities: does it contribute to housing affordability and socioeconomic diversity? Cities 163:106035. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2025.106035

Kukk, M., and Levenko, N. (2024). Measuring the effects of borrower-based policies on new housing loans. Econ. Anal. Policy 82, 666–684. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2024.04.011

Landis, J. D., and McClure, K. (2010). Rethinking federal housing policy. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 76, 319–348. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2010.484793

Linneman, P. D., and Megbolugbe, I. F. (1992). Housing affordability: myth or reality? Urban Stud. 29, 369–392. doi: 10.1080/00420989220080491

Maher, C. A. (1974). Spatial patterns in urban housing markets: filtering in Toronto, 1953-71. Can. Geogr./Géogr. Can. 18, 108–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.1974.tb00113.x

Monkkonen, P. (2019). Empty houses across North America: housing finance and Mexico’s vacancy crisis. Urban Stud. 56, 2075–2091. doi: 10.1177/0042098018788024

Naik, K. (2023). “Inclusive dreams and excluded realities: applying social exclusion theory to the analysis of xenophobia in the south African ‘rainbow nation.’” in Contemporary discourses in social exclusion. eds. Alemanji, A. A., Meijer, C. M, Kwazema, M., and Benyah F. E. K. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

Nair, R. J., Brembilla, E., Hopfe, C., and Mardaljevic, J. (2020). “Influence of building design on occupant comfort in adaptive climate zones” in 11th Windsor Conference: Resilient Comfort, WINDSOR 2020 - Proceedings. eds. Roaf, S., Nicol, F., and Finlayson, W. (Windsor, UK: NCEUB 2020), 633–646.

Nicholson, G. (1989). Non-solution solutions to housing affordability. Town Country Planning 58, 344–346.

Noreen, M., Mia, M. S., Ghazali, Z., and Ahmed, F. (2022). Role of government policies to Fintech adoption and financial inclusion: a study in Pakistan. Univer. J. Account. Finan. 10, 37–46. doi: 10.13189/ujaf.2022.100105

Novoa, A. M., Ward, J., Malmusi, D., Díaz, F., Darnell, M., Trilla, C., et al. (2015). How substandard dwellings and housing affordability problems are associated with poor health in a vulnerable population during the economic recession of the late 2000s. Int. J. Equity Health 14:120. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0238-z

Odeyemi, E., and Skobba, K. (2022). Housing affordability among rural and urban female-headed householders in the United States. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 43, 854–866. doi: 10.1007/s10834-021-09802-3

Owen, R., and Vedanthachari, L. (2023). Exploring the role of U.K. government policy in developing the university entrepreneurial finance ecosystem for cleantech. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 70, 1026–1039. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2022.3153319

Pritchard, J. (2002). Preliminary submission to the house of representatives economic, finance and public administration committee inquiry into cost shifting by state governments to local government. Aust. J. Public Adm. 61, 10–13. doi: 10.1111/1467-8500.00295

Razin, A. (2022). Understanding national-government policies regarding globalization: a trade-finance analysis. J. Gov. Econ. 8:100060. doi: 10.1016/j.jge.2023.100060

Robinson, I. C., and Keefe, D. G. (1980). Commodity analysis: its application in the context of the south African mining finance house. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 80, 112–122.

Rosén, M., Aberg, G., Andersson, R., Angelin, B., Borgå, P., Gilliam, H., et al. (1992). How to finance preventive care within the buy-sell system and house-physician organizations?; [Hur finansiera det förebyggande arbetet i köp-sälj-och husläkarorganisationer?]. Lakartidningen 89, 3455–3456

Saha, A., Rooj, D., and Sengupta, R. (2023). Loan to value ratio and housing loan default – evidence from microdata in India. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 18, 4545–4564. doi: 10.1108/IJOEM-10-2020-1272

Salga, J. (2005). The eastern European workshop on housing finance and housing affordability. Acta Oecon. 55, 89–93. doi: 10.1556/aoecon.55.2005.1.5

Sani, N. M. (2015). Relationship between housing affordability and house ownership in Penang. Jurnal Teknol. 75, 65–70. doi: 10.11113/jt.v75.5236

Schifter, D. E., and Ajzen, I. (1985). Intention, perceived control, and weight loss. An application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 49, 843–851. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.843

Schmid, A. A., and Robison, L. J. (1995). Applications of social capital theory. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 27, 59–66. doi: 10.1017/S1074070800019593

Schwartz, H. (2013). Power house: the struggle over mortgage finance. Forum (Germany) 11, 33–46. doi: 10.1515/forum-2013-0029

Sharam, A., Bryant, L., and Alves, T. (2015). De-risking development of medium density housing to improve housing affordability and boost supply. Aust. Planner 52, 210–218. doi: 10.1080/07293682.2015.1034146

Shukla, R. (2022). Sources of finance and in-House R&D: a study of electronic firms in India. Euras. Stud. Bus. Econ. 21, 57–77. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-94036-2_4

Simkins, C., Oelofse, M., and Gardner, D. (1992). Designing a market-driven state-aided housing programme for South Africa - an application of the urban foundation’s housing affordability model. Urban Forum 3, 13–38. doi: 10.1007/BF03036537

Sorauf, F. J. (2024). “Varieties of experience: campaign finance in the house and senate” in Elections in America ed. Schlozman, K. L. (UK: Taylor and Francis).

Sorensen, A., and Chen, P. (2022). Identity in campaign finance and elections: the impact of gender and race on money raised in 2010–2018 U.S. house elections. Polit. Res. Q. 75, 738–753. doi: 10.1177/10659129211022846

Squires, G. D. (2008). Urban development and unequal access to housing finance services. N. Y. L. Sch. L. Rev. 53:255.

Srivastava, A., Jain, V. K., and Srivastava, A. (2009). SEM-EDX analysis of various sizes aerosols in Delhi India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 150, 405–416. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0239-0

Starr, M. A., and Yilmaz, R. (2007). Bank runs in emerging-market economies: evidence from Turkey’s special finance houses. South. Econ. J. 73, 1112–1132. doi: 10.1002/j.2325-8012.2007.tb00820.x

Stutz, F. P., and Kartman, A. E. (1982). Housing affordability and spatial price variations in the United States. Econ. Geogr. 58, 221–235. doi: 10.2307/143511

Tang, Y., and Ma, C. (2018). Fiscal pressure, land finance and ratchet effects of house prices. China Finance Econ. Rev. 7, 73–94. doi: 10.1515/cfer-2018-070105

Tao, L., Pang, L., Tong, D., and Hui, E. C. M. (2025). Disentangling housing affordability of migrant households through the lens of trade-offs: evidence from urban China. Habitat Int. 162:103437. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2025.103437

Thorns, D. C. (1988). New solutions to old problems: housing affordability and access within Australia and New Zealand. Environ. Plann. A. 20, 71–82. doi: 10.1068/a200071

Tribe, L. H. (2010). “Testimony of Laurence h. tribe, house of representatives committee on the judiciary, hearing on “the first amendment and campaign finance reform after citizens United”” in The first amendment: select issues ed. Ferro, R. L. (Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc).

Vijaya, N., Prabhakaran, P., and Lakshmi, A. (2018). “Effectiveness of housing schemes in rural India: a case study of vellanad, Kerala” in Emerging trends in engineering, science and Technology for Society, energy and environment - proceedings of the international conference in emerging trends in engineering, science and technology, ICETEST 2018. eds. Vanchipura, R., and Jiji, K.S. (Leiden, The Netherlands: CRC Press/Balkema), 951–956.

Vizek, M. (2009). Housing affordability in Croatia and selected European countries; [Priuštivost stanovanja u Hrvatskoj i odabranim europskim zemljama]. Rev. Soc. Polit. 16, 281–297. doi: 10.3935/rsp.v16i3.809

Wahab, N. A., Hamzah, H., and Yusof, R. M. (2016). Promoting housing affordability in Malaysia: can Islamic finance play a role? Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 6, 88–102.

Withers, S. D. (1997). Demographic polarization of housing affordability in six major United States metropolitan areas. Urban Geogr. 18, 296–323. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.18.4.296

Yap, J. B. H., and Ng, X. H. (2018). Housing affordability in Malaysia: perception, price range, influencing factors and policies. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 11, 476–497. doi: 10.1108/IJHMA-08-2017-0069

Zhao, Y., Dong, L., Sun, Y., and Zhang, N. (2025). Extreme precipitation, energy poverty and the moderating effects of digital inclusive finance: evidence from China’s householders. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 112:107849. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2025.107849

Keywords: financial inclusion, finance, loan, home loan, equity, government policy

Citation: Syed K, Mohanty SN, Bhatnagar M, Kumar P, Khanna R and Jain A (2025) Exploring the impact of affordable housing finance on urban inclusivity: a structural equation modelling study of access, perception, and financial empowerment. Front. Sustain. Cities. 7:1602317. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1602317

Edited by:

Mohammad K. Najjar, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, BrazilReviewed by:

Roberto Bruno, University of Calabria, ItalyKunle Elizah Ogundipe, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Syed, Mohanty, Bhatnagar, Kumar, Khanna and Jain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mukul Bhatnagar, bXVrdWxiaGF0bmFnYXIxOTkzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Khasim Syed1

Khasim Syed1 Mukul Bhatnagar

Mukul Bhatnagar Pawan Kumar

Pawan Kumar