Abstract

Introduction:

This article explores clinical law programs of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) and their role in advancing equitable development in urban communities which have been impacted by disinvestment, redlining, and gentrification. Building on the legacy of the Great Migration and subsequent urban decline, the communities where the six HBCU law schools, accredited by the American Bar Association (ABA), are located have experienced a range of development challenges. They are Orlando, Florida, Durham, North Carolina, Washington, D. C., Houston, Texas, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The study examines whether these law schools deliver what their stated priorities promise, namely, to meaningfully contribute to the equitable development goals of the communities where they are located.

Methods:

Using a systematic review of publicly available documents as well as case study materials from the five metro areas, the study reveals a strong alignment between the clinical work offered by the law schools in our sample and the development needs of the metropolitan areas where they are located.

Results:

These alignments are particularly evident in the areas of affordable housing, youth advocacy, immigration, and economic justice.

Discussion:

While the study is limited by its reliance on publicly available data, the findings suggest that HBCU law schools and their clinical programs provide critical contributions to the civic infrastructure of US metropolitan areas seeking to achieve equitable urban revitalization. The findings also identify opportunities for further research, to investigate the dynamics between law school clinical programs and equitable community development in more depth.

1 Introduction

The Great Migration during the period of 1940–1970 saw large groups of Black Americans emigrating from the Southern United States to the Northern and Western regions of the country in search of economic opportunities, improved quality of life and refuge from discrimination (Shi et al., 2022). The population shift, which saw an outmigration of rural populations into primarily metropolitan areas, sparked “the outmigration of White families away from cities and toward suburban areas also termed ‘White flight” (Boustan, 2010; Ferreira et al., 2024). The influx of a reported four 4 million Black migrants after World War II was not always embraced. Instead, it was met with policies, like redlining, that led to disinvestments in urban communities and a shift of resources to the suburbs (Aaronson et al., 2021). Redlining marked predominantly black neighborhoods as risky and therefore denied mortgages, insurance, and other services to residents of redlined areas (Archer, 2025).

There are a plethora of studies that indicate causal relationships between these policies and the socioeconomic discrimination against predominantly Black urban communities (Aaronson et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2022; Dreier, 2003; Robinson et al., 2020; Ferreira et al., 2024; Smith and Thorpe, 2020; Archer, 2025). For example, Dreier (2003) noted that middle class residents moving out in large numbers resulted in reduced tax revenues of local governments and the outmigration of local businesses. This diminished community resources to invest in schools, hospitals and health centers, police, and fire departments along with a decline of private sector services including grocery and department stores. The compounded consequences of these discriminatory policies were a reduced economic mobility of Black Americans and diminishing services for predominantly Black communities.

The resulting disparities garnered national attention, advocacy, and grassroots efforts to revitalize urban communities starting in the 1960s. Leading the way was the Fair Housing Act of 1968, followed by the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975, and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977. Dreier argues that all three legislations were enacted to combat ‘the role that lenders played in neighborhood decline and racial segregation’ (Dreier, 2003, p. 341).

At the same time, and set across the same landscape, law schools around the country joined community organizations to address the needs of marginalized and low-income residents in urban communities. Practicing attorneys and law school administrators recognized the gap of available legal representation for civil legal matters and embraced the idea of law school students providing much needed services to clients in exchange for academic credit. Grossman writes:

“…The social change of the late 1960’s which proved to have the greatest impact on the development of clinical legal education stemmed from the awakening interest of the government in the conditions of the poor… Among the governmental measures taken…was the provision of civil and criminal legal services to those unable to afford legal counsel” (Grossman, 1973, p. 173).

We define a clinical legal program as a program that allows law school students to practice law under the supervision of an experienced attorney. The American Bar Association standards require all ABA accredited programs to offer law students some form of hands-on training during their course of study (Kotkin, 2020). Simulation courses teach students particular competencies using simulated fact patterns rather than real-time, real-world problems” (American Association of Law Schools, 2017).

Clinical legal programs became especially popular as the demand for access to legal services increased overall and legal services were increasingly recognized as “essential” (Grossman, 1973, p. 174). While efforts to reinvest in urban communities did result in an increase in homeownership, tax revenues, and small business loan programs in urban centers, it also led to gentrification, which had further repercussions for marginalized communities in urban areas (Robinson et al., 2020). The term gentrification is attributed to Ruth Glass (Guan and Cao, 2020), who defined it in 1964 as a phenomenon that occurs when an inner-city neighborhood inhabited by primarily low-income and minority residents undergoes improvements and revitalization efforts that result in the reduced availability of affordable housing. These revitalization efforts further resulted in the displacement of long-time residents, disrupting schooling for children and youth, increasing self-reported stress and health problems, and a loss of a sense of belonging for predominantly Black low-income residents (Gómez, 2023; Dsouza, 2022; Smith and Thorpe, 2020; Green et al., 2013).

Despite these known negative impacts, Dsouza (2022) reports that low-income communities generally supported development efforts and infrastructure improvements that aim to promote a higher quality of life. This begs the question; how do communities go about achieving equitable development and revitalization and what (if any) efforts have been made to counteract gentrification? Research points to the necessity of stakeholder engagement and targeted approaches that recognize the need to take distinct characteristics of local communities into account in identifying development priorities and pathways (Hampton and O’Hara, 2024; Groark and McCall, 2018; Bloomgarden, 2017). We use the Arnstein’s Ladder of citizen participation to argue that HBCU law schools are vital in assuring that the citizens in the respective communities where the law schools operate have a voice in matters that are important to them. In fact, the law schools provide the advocacy necessary to represent the most vulnerable residents in need of legal representation.

The seminal work of Arnstein’s Ladder, first published in 1969 provides a topology arranged in a ladder pattern to describe citizen participation and the extent to which citizens are willing to engage. The latter pattern is arranged from bottom to top in the following order from non-participation (manipulation, therapy) to tokenism (informing, consultation, placation), and active participation (partnership, delegated power, citizen control). We argue that HBCU law schools have been in active partnership with citizens in their respective communities indicating a level of ‘active participation.’ In fact, their objective for providing legal representation is to ultimately move residents to full control of their lives by abating their legal problems (Arnstein, 2019). By nature of the client-attorney relationship, the clients and their voices and needs are central to the services provided by HBCU law schools which directly relates to the top rung of ‘active participation,’ in Arnstein’s ladder.

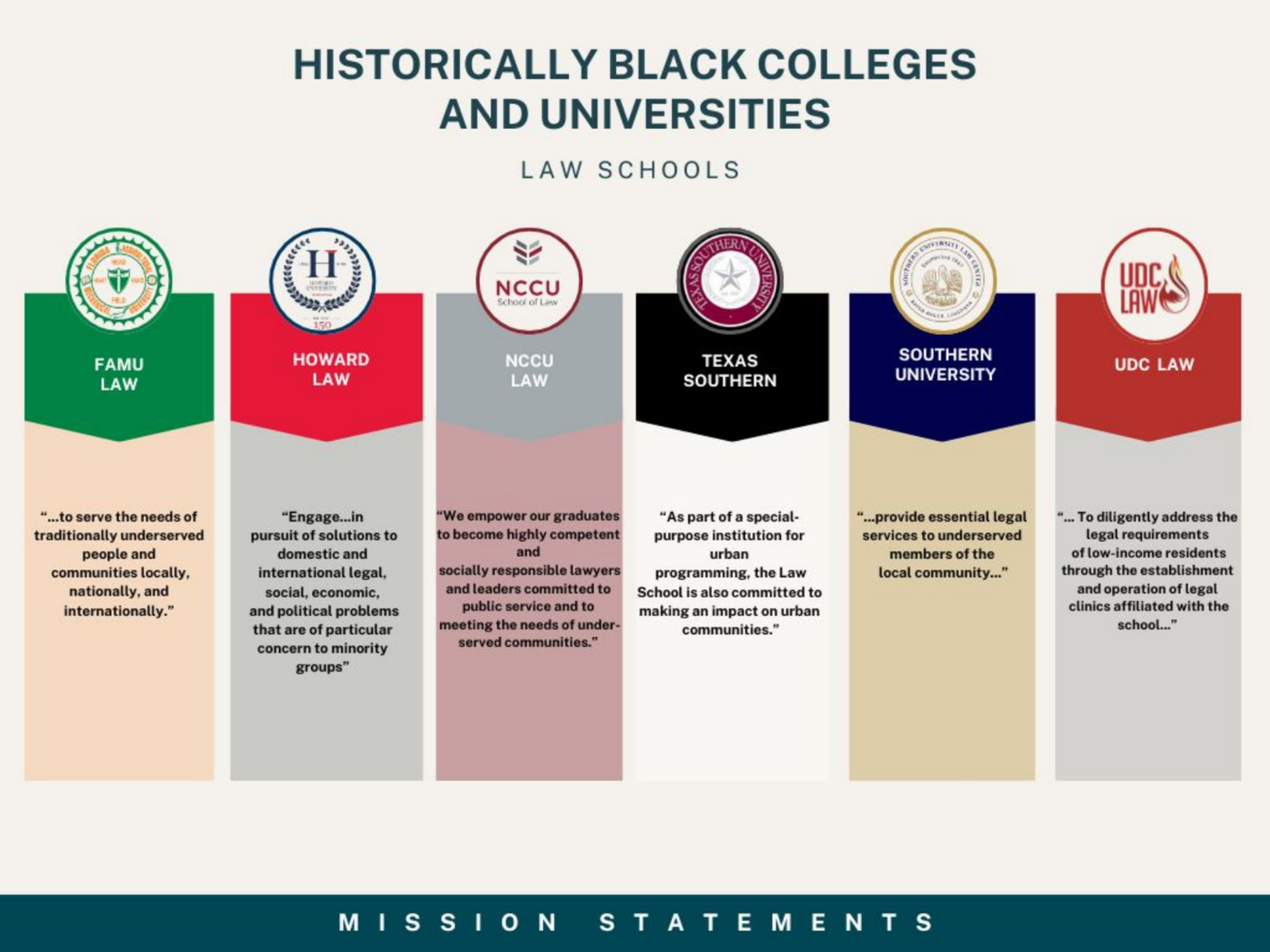

Recognizing that engagement and grass roots efforts by local community residents and organizations play a critical role in achieving progress for marginalized communities, this article explores whether law school clinical programs effectively address the equitable development needs of the communities where they are located thus promoting more equitable development goals in their metropolitan areas. The study focuses on six ABA accredited law schools at Historically Black College and Universities. Each of these law schools are explicit about their missions to serve vulnerable communities (Figure 1). Akintobi et al. (2025) further found that the law schools are committed to four key aspects of active participation, namely advocacy, representation, client outcomes, and engagement as key indicators of community involvement. This study presents the findings from a systematic review of publicly available documents from the communities where the six ABA accredited HBCU law schools are located to test the hypothesis that the engagement of HBCU law schools indeed meets the equitable development priorities of their communities. In addition to the systematic review, we introduce six case studies from Orlando, Florida, Durham, North Carolina, Washington, D. C., Houston, Texas, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to examine (1) the alignment between local legal needs and HBCU clinical initiatives, (2) the extent to which the clinical law programs contribute to equitable community development, and (3) the broader implications for urban development in underserved communities in the United States.

Figure 1

HBCU law school mission and value statements.

By situating the role of HBCU law school clinical programs within the broader discourse on urban development, this research explores the intersections between legal infrastructure, community engagement, and equitable development. The study therefore contributes to the growing body of literature on the role of legal institutions in shaping urban redevelopment beyond gentrification and offering insights into how community-based legal education can function as a catalyst for sustainable and inclusive urban development in historically underserved metropolitan areas in the U. S, and possibly in other locations.

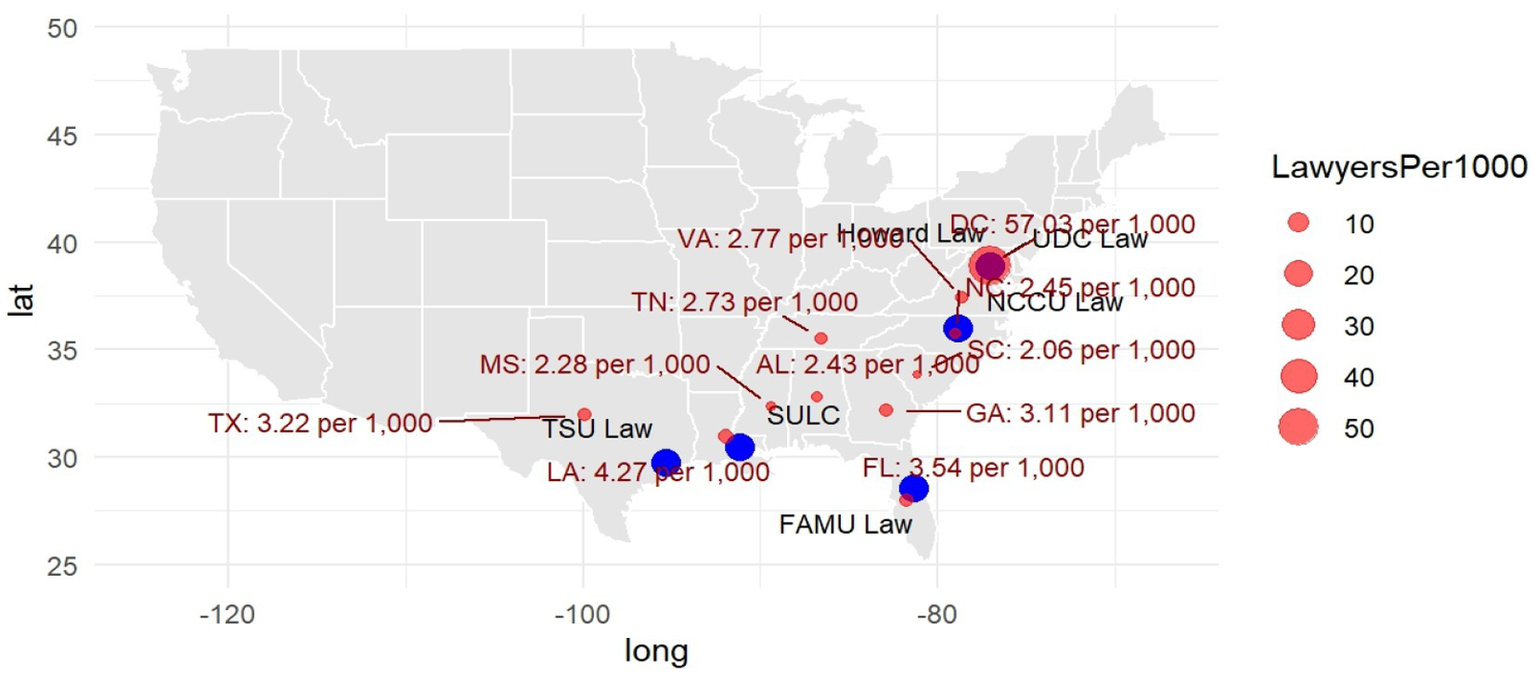

2 Access to justice: the history of disinvested US metropolitan areas

An examination of lawyer-to-population ratios across the 50 U. S. states reveals a stark contrast in the availability of legal professionals, in Southern versus Northern states (Figure 2). Southern states rank consistently below the national average of 3.8 lawyers per 1,000 residents. States such as New York, which has 9.6 lawyers per 1,000 residents, and Massachusetts, with 5.7 per 1,000 residents, maintain significantly higher concentrations of legal professionals than Southern states such as Mississippi (2.3 per 1,000), Alabama (2.4 per 1,000), and South Carolina (2.1 per 1,000). Even in states with the largest legal concentrations of legal professionals in the south, such as Texas (3.2 per 1,000) and Florida (3.6 per 1,000) for example, the density remains lower than in similarly populous states in the northern U. S. such as Illinois (5.0 per 1,000) and California (4.5 per 1,000) (American Bar Association, 2024). This suggests that, despite growing populations in metropolitan areas in the southern US, and increasing legal needs in Southern states, there continues to be a significant shortage in legal professionals.

Figure 2

HBCU law schools and legal representation in the mid-atlantic and Southern U. S.

The disparity in legal representation is even more pronounced in the rural South. The lack of legal representation disproportionately affects low-income individuals, and historically marginalized communities, limiting access to legal services in areas such as family law, housing disputes, and criminal defense. The underrepresentation of lawyers in southern states has broader implications for the administration of justice, as residents may struggle to secure adequate legal counsel or face delays in judicial proceedings due to overburdened legal professionals (Brigida, 2024a).

There are only six ABA-accredited HBCU law schools across the United States. All six share a common mission of expanding access to legal education in historically underrepresented communities. They were founded between 1869 and 1972.

Howard University School of Law (HUSL), founded in 1869, has a long history of legal activism, producing civil rights leaders like Charles Hamilton Houston, who shaped its mission to train “social engineers” committed to racial justice (Howard University School of Law, 2024c). Howard University School of Law offers students nine clinics. They provide 246 clinic seats and 342 simulation course seats.

North Carolina Central University School of Law (NCCU), established in 1939, prioritizes diversity and public-interest lawyering, offering eight clinical programs in areas such as criminal defense, intellectual property, and veterans’ law. The school provides 119 clinic seats and 464 simulation course seats (North Carolina Central University, 2020).

Texas Southern University Thurgood Marshall School of Law (TSU), founded in 1946, was created to increase diversity in the legal profession and is recognized as one of the most diverse law schools in the country. It offers four clinical programs, including immigration and criminal defense, with 70 clinic seats available (Thurgood Marshall School of Law, 2024).

Southern University Law Center (SULC), founded in 1947 to provide legal education to Black students excluded from Louisiana State University’s law school, now boasts the largest enrollment among HBCU law schools. With 10 clinics in areas including housing, youth justice, and economic justice, SULC offers the highest number of student clinic seats at 526 for the 2023–2024 academic year (Southern University Law Center, 2024b). FAMU Law founded in 1949 and re-established in 2002, focuses on training lawyers to serve traditionally underserved communities (Florida A&M University, 2024a).

Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University College of Law (FAMU) offers six clinical programs, including the Criminal Defense Clinic, Economic Justice Clinic, Housing Clinic, Mediation Clinic, Tax Clinic, and Youth Justice Clinic. During the 2023–2024 academic year, the school provided 40 seats for student participation in its clinical offerings and offered 296 simulation courses (Florida A&M University, 2024b).

University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law (UDC), originally established as Antioch Law School in 1972, and later merged with UDC in 1996, is nationally recognized for pioneering clinical legal education (University of the District of Columbia, 2021). It provides nine clinics in areas such as racial justice, housing advocacy, and whistleblower protection, reinforcing its commitment to serving marginalized communities. In the 2023–2024 academic year, the law school offered 165 clinic seats plus 210 seats in simulation courses (University of the District of Columbia, 2023).

Miles College of Law (MCL) admitted its first class in 1974. However, it is a non-ABA accredited institution that primarily serves part-time students in Alabama. Due to limited publicly available information, and the different accreditation standards, it is excluded from our sample of HBCU law schools (Miles College of Law, 2024).

3 Methodology

This study employs a systematic review of publicly available documents to identify the urban development goals of the five communities in which the ABA accredited HBCU law schools are located. The review follows the methodology outlined by

Gough et al. (2012)and further refined in the PRISMA statement (2020). It includes the following components:

Eligibility criteria

Information sources

Search strategy

Selection process

Data items

Effect measurers

Sources for the systematic review include publicly available documents such as development reports, strategic plans, and other documents summarizing strategic development and planning initiatives for each city in our sample. Search terms used include “[city name] + strategic plan” or “action plan,” “development report.” Websites were excluded from consideration if they did not have a “.gov” top-level domain, ensuring the reliability and official status of the sources.

To further substantiate the findings a secondary search was conducted using academic databases such as ProQuest and JSTOR, as well as newspaper archives, books, and book chapters. Search terms include the name of each city or its corresponding law school. Only sources published between 2010 and 2024 were included in the systematic review. In total, 72 publicly available documents were examined.

In addition, U. S. Census data for each of the five cities provided relevant socio-economic and demographic background data including population size, household income, education levels, age distribution, percentage of foreign-born populations and other relevant data.

The study then compares the dominant development priorities identified through the systematic review with case study materials describing the clinical work of the six HBCU law schools located in the five cities and metropolitan areas across the US. The case study method was selected because it facilitates in-depth analysis of each law school’s clinical programs within their specific community context (Cresswell, 2014). Including multiple case studies enables a comprehensive exploration of the economic, social, and cultural dimensions of community engagement across the sample, and facilitates the assessment of cross-cutting themes (Patton, 2002).

Additionally, an earlier study (Akintobi et al., 2025) presented a comprehensive analysis of focus areas and programmatic trends across clinical law programs offered by the six ABA accredited HBCU law schools in our sample. The study found that the clinical law programs share common impact areas, including advocacy for affordable housing, efforts to address poverty and economic inequities, and initiatives in youth justice, immigration, crime, and public safety. This provides a structured lens for evaluating how HBCU law school clinical programs function within their broader urban development context and what access they provide to legal services that are considered relevant from the perspective of local communities.

4 Community needs and objectives

Our systematic review of the publicly available documents published between 2010 and 2024 summarizes the development objectives of the five US metropolitan areas that are home to one or more of the HBCU law schools in our sample. We examined the development objectives of the five metropolitan areas using a combination of documents that provided information on the city and the HBCU that is located within the city. The results from the review are summarized in the following sections of the paper based on the following order: (1) Orlando, Florida, (2) Durham, North Carolina, (3) Washington, DC, (4) Houston, Texas, and (5) Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

4.1 Orlando, Florida

Orlando, Florida has a population of 320,742 residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023c). Orlando’s residents are majority White (43.2 percent), followed by Hispanic/Latino (35.6 percent), Black residents (22.9 percent), and Asian (4.4 percent) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023b). Less than 0.1 percent of residents are Native American and less than 0.1 percent are Hawaiian or Pacific-Islander (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023c). The median income of the city is $69,268 and 42.2% of Orlando residents hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. Just over fifteen (15.5) percent of Orlando residents live at or below the poverty level. Florida immigrant populations comprise of “21.6 percent of the state’s residents are “foreign-born and “26.6 percent [make up] the state’s labor force” (American Immigration Council, 2024). The growth of immigration to the United States has been met with growing concerns and contemporary nativism (Valle, 2022).

Recent policies and legislation, like the SB1718, have enhanced the penalties for undocumented immigrants and businesses that employ undocumented immigrants (The Florida Senate, 2023). Since the passing of SB1718, Florida companies have lost workers and put thousands of immigrants, both documented and undocumented “at risk of being arrested, charged, and prosecuted with a felony for transporting a vaguely defined category of immigrants into Florida, even for simple acts such as driving a family member to a doctor’s appointment or going on a family vacation” (ACLU of Florida, 2024; Garsd, 2024). The Farmworker Association of Florida and other organizations filed suit against Governor Ron DeSantis, Florida Attorney General, Ashley Moody, and others to persuade courts to grant an injunction to stop the active enforcement of the law. It has been well documented that immigration laws like SB1718 impact the daily lives of documented and undocumented immigrants placing this vulnerable community with a heightened need for advocacy and support.

Orlando’s rapid economic and population growth provides opportunities for wealth generation for minority business owners. However, there are barriers to entrepreneurship that disproportionately affect minorities and low-income individuals. Barriers to entrepreneurship and wealth generation include education, licensing and permits, accessing small business loans/financing, and navigating the process to applying for and securing a patent for innovations.

The top priorities for Orlando, Florida that emerged from the analysis of the city’s documents include transportation, housing, education, economic development, and a shared vision that aligns legislative priorities with public polices (Housing and Community Development, 2024; Giuliani, 2024).

4.2 Durham, North Carolina

Durham, North Carolina has a population of 296,186 residents. 40.5 percent of Durham’s residents are majority White 40.5 percent, 34.4 percent are Black, 14.7 percent are Hispanic or Latino, 6.1 percent are Asian, and the remaining races include Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, American Indian, and residents that have reported to be two or more races (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023c). Approximately 12.2 percent of Durham’s residents report income at or below poverty level. The median household income is $79,234 and 55.7 percent of the population has earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. It is important to note that the median income is stratified by race with Black residents and Hispanic residents reporting lower average incomes that non-Hispanic white residents (De Marco and Hunt, 2018).

Annually, the residents and government officials in the City of Durham produce an Annual Action Plan that identifies community needs and priorities. The Annual Action Plan of 2024 identified affordable housing, unsheltered residents, community development and promotion of entrepreneurship, and “a need for planning, administration, management, and oversight of federal, state, and local funded programs” as top priorities for the city (City of Durham, 2023).

The city experienced rapid growth between 2010 and 2016 (Staff, 2018). However, there were not enough homes to accommodate the influx of new residents. Additionally, “the housing shortage [was] especially acute for low-income households” (Staff, 2018). As property values rise along with rent prices and the “disparities in financial wellbeing persist,” evictions and displacement disproportionately affect low-income, predominantly Black neighborhoods (Sheridan, 2018; Staff, 2018).

The city’s FY24-26 strategic plan identifies creating and evaluating “new community policing strategies” and partnering with schools to augment outreach to at-risk youth among its citywide priorities (City of Durham, 2024). Crime prevention is a state-wide concern in North Carolina as the state has seen an increase in its crime rate from 2022 to 2023 (Guze, 2024). North Carolina passed several laws in the past 7 years aimed at reforming the juvenile justice system. The 2017 Juvenile Justice Reinvestment Act raised the age of the juvenile court jurisdiction to 18 (North Carolina Department of Public Safety, 2017). In 2019 the North Carolina General Assembly passed the Youth Accountability and Rehabilitation Act which provides greater access to rehabilitation services, emphasizing restorative justice and reducing the number of young people incarcerated in adult facilities. Most recently, the Second Chance Act (enacted in 2021) allows for the expungement of certain juvenile records, enabling young people to have a clean slate for future opportunities in education and employment (UNC School of Government, 2019).

The top priorities for Durham, North Carolina that emerged from the analysis of this city’s development documents indicate a focus on public safety, reducing disparities in housing and promoting financial equitable policies that ensure a more just future for Durham’s residents.

4.3 Washington, district of Columbia (Washington, DC)

Washington, D. C. has a population of 678,972 residents. The majority of the residents are Black 42.5 percent, White 36.6 percent, 12 percent are Hispanic or Latino, 4.0 percent are Asian, and the remaining two or more race at 4.52 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023a). Sixty-four percent of residents hold a bachelor’s degree or higher (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023a). However, despite a relatively high level of education and high median household income (in 2023 was $106,287), 15.2 percent of District of Columbia residents live at or below the poverty level. Most low-income households are primarily concentrated in the Eastern section of Washington, D. C. beyond the Anacostia River (Kids Count Data Kids Count Data Center, 2023).

Sustainable DC Equity Plan, report that “communities of color are more prone to experience deep and persistent gaps in income, health, employment, and education (Department of Energy and Environment, 2024). Socioeconomic status and education are positive indicators of community health and resilience (Graham, 2007). Graham notes, “lives are at their shortest and health is at its poorest among the individuals, households and communities in the poorest circumstances” (Graham, 2007, p. xi). There is evidence of wealth disparities where low-income households are more likely to face eviction, live in poor housing conditions, and experience poor health at a higher rate than wealthy-income households.

The United States Attorney Matthew Graves, stated that the total violent crime for 2024 in the District of Columbia crime rate is down by 23% from 2023 levels, the lowest it has been in over 30 years (US District Attorney’s Office DC, 2025). Interestingly, the District of Columbia experiences an increased rate of intimate partner violence whereby 1 in 2 women and more than 2 in 5 men reported experiencing intimate partner violence (Office of Victim Services and Justice Grants, 2024). Domestic violence has a ripple effect, impacting not only its victims, but also those in their care, the court system, and the wider community. The impact is intensified when victims are unable to afford legal representation.

The District of Columbia has acknowledged the number of youths involved in the justice system. The rate of arrests in the District of Columbia between 2016 and 2022 were double the national average at 52 arrests per 1,000 youth between the ages of 10 and 17 (DC Policy Center, 2023). In the 2018–2019 to 2019–20 academic years, 4 percent of public-school youth aged 10–17 were involved in the justice system. The youth were typically reported as male, Black, homeless, or eligible for public assistance. The District of Columbia has employed strategies to provide early intervention for young people in the District. There is still an apparent and increasing need for advocacy and guidance for young people involved in the justice system.

The three top priorities for the District of Columbia that emerged from our data analysis are public safety, especially addressing youth crime, addressing affordable housing and childcare, and achieving racial and economic equity (Howell, 2016).

4.4 Houston, Texas

Houston, Texas has a population of 2,314,157 residents. The majority of the residents are White 35.5 percent, Black 22.9 percent, 44.1 percent are Hispanic or Latino, 6.9 percent are Asian, 0.9 percent American Indian and Alaskan Native, 0.1 percent Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and two or more race at 19.2 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023b). Thirty six percent of Houston’s resident hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. The median household income in Houston is $62,894 and the percentage of residents who live at or below the poverty level is 19.7 percent.

Houston’s 2024 Annual Action Plan outlines eight goals and actionable steps toward improving the quality of life for the residents of Houston City. The eight goals include but are not limited to preserving and expanding the supply of affordable housing, providing housing for residents affected by HIV/AIDS, revitalizing neighborhoods with improvement to public facilities, eliminating environmental hazards (i.e., lead paint), and fostering economic development (business growth in low- and moderate-income areas) (Whitmire and Nichols, 2024). Additionally, Houston has seen the influx of foreign-born residents of which two thirds of all immigrants in Houston have legal status (Migration Policy Institute, 2023). The Migration Policy Institute “estimates about 360,000 adults in the metro area (at least 276,000 in Harris County alone) meet the criteria to become U. S. citizens, but face barriers to naturalization for reasons including limited proficiency in English and the cost to apply” (Migration Policy Institute, 2023). According to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), a tool that tracks open court cases, showed as of November 2024, Houston’s three immigration courts have a total of 99,630 pending cases (Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, 2024). The Houston Landing reported 117,000 pending cases and less than 29 percent of those cases having legal representation in 2023 (Brigida, 2024b). The large percentage of immigrants whose incomes fall well below the federal poverty line and nativist leaning laws, the pathway to citizenship for many Houston residents remains elusive (Brigida, 2024b).

Houston has a crime rate higher than the national average with a large minority population involved in the justice system (FBI Crime Data Explorer, 2024). In 2021, Houston courts reported the second and third highest number of total pending cases at the end of fiscal year 2021 (LaVoie, 2021). The comparatively high period between the submission of a case for decision and case disposition (final decision) suggests that there may be inefficiencies or delays in the decision-making process, potentially due to factors such as limited resources, procedural bottlenecks, or the complexity of the cases involved.

The three top priorities for Houston, Texas that emerged from our data analysis are public safety crime, infrastructure building of roads and streets, and affordable housing (University of Houston, 2025).

4.5 Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge, Louisiana has a population of 219,573 residents. The majority of the residents are Black 51.0 percent, White 35.0 percent, 6.5 percent are Hispanic or Latino, 3.6 percent are Asian. The median household income is $49,944 with 35.8 percent of residents have obtained a bachelor’s degree. Twenty-five percent of the residents of Baton Rouge live at or below the poverty level. Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s crime rate was at 30 percent increase during the COVID-19 pandemic (Stebbins, 2021). In 2020 Baton Rouge had the highest homicide rate in the United States with 952 reported violent crimes per 100,000 people (Stebbins, 2021).

Baton Rouge acknowledged that justice reform efforts were needed related to youth incarceration. Much of this effort was spearheaded by several lawsuits that revealed that teenage inmates were being deprived of food, clothing, medical care and were routinely beaten by guards (Butterfield, 2000). The State of Louisiana enacted two laws (the Senate Bill 323 and House Bill 746). Senate Bill 323 (Act 693) ensures that youths are placed in appropriate facilities and provided with opportunities to be transitioned to a less restrictive environment with positive progress. House Bill 746 limits the amount of confinement in secure facilities to 8 h with a maximum extension of 24 h per incident. The law also mandates data reporting to ensure compliance (Office of Juvenile Justice, 2024). The majority of youth involved in the justice system are Black, stem from low-income households, have limited access to legal services, and minimal community support to achieve equitable outcomes that breaks the cycle of incarceration.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana saw an influx of residents in 2005 as a result of Hurricane Katrina that caused devastation to New Orleans, a city located 82 miles northwest of Baton Rouge. Hurricane Katrina had deleterious and long-lasting impacts on the economic and social well-being of the residents of Baton Rouge. Hurricane Katrina impacted Baton Rouge housing infrastructure where thousands of New Orleans residents were displaced after Hurricane Katrina. Many evacuees from New Orleans did not or could not return to their previous residents. Fussell and Harris (2014) reported that the impact of Hurricane Katrina was felt mostly by vulnerable communities, primarily because they did not own their home prior to the hurricane hitting the area (Fussell and Harris, 2014). Green et al. (2013) suggest that the displacement of Black communities and the slow return to New Orleans may be due in large part to racially “discriminatory policies and practices that contributed to the disparity in the African American communities’ return to New Orleans. Political leaders in New Orleans paid more attention to the interests of developers and big businesses with the goal of restoring New Orleans rather than the interests of the predominantly black working class in the city” (Green et al., 2013, p.1). A reported 3,200 residents who were able to return to New Orleans received a grant from a government program entitled “Road Home” however, these residents were sued by the Department of Housing Urban Development (HUD) of the State of Louisiana for using the funds on repairs to their home rather than making their homes more flood proof (LaRose, 2023).

United States Secretary of Housing, Marcia Fudge, stated in a 2023 speech in Baton Rouge, that the Road Home program would be closed. She further announced the cessation of active litigation and judgments against homeowners who received funds from the project. Fudge also discussed HUD’s focus on climate change and how, natural disasters (like Hurricane Katrina) caused by the climate crisis exacerbates the issue of displacement and safe housing for disinvested communities (Targeted News Service, 2023). Fudge highlighted the need for improvements to and the provision of affordable housing for low-to middle-income families (Targeted News Service, 2023).

The three top priorities for Baton Rouge, Louisiana that emerged from our data analysis are affordable housing, public safety crime, and juvenile justice reforms.

5 Analysis

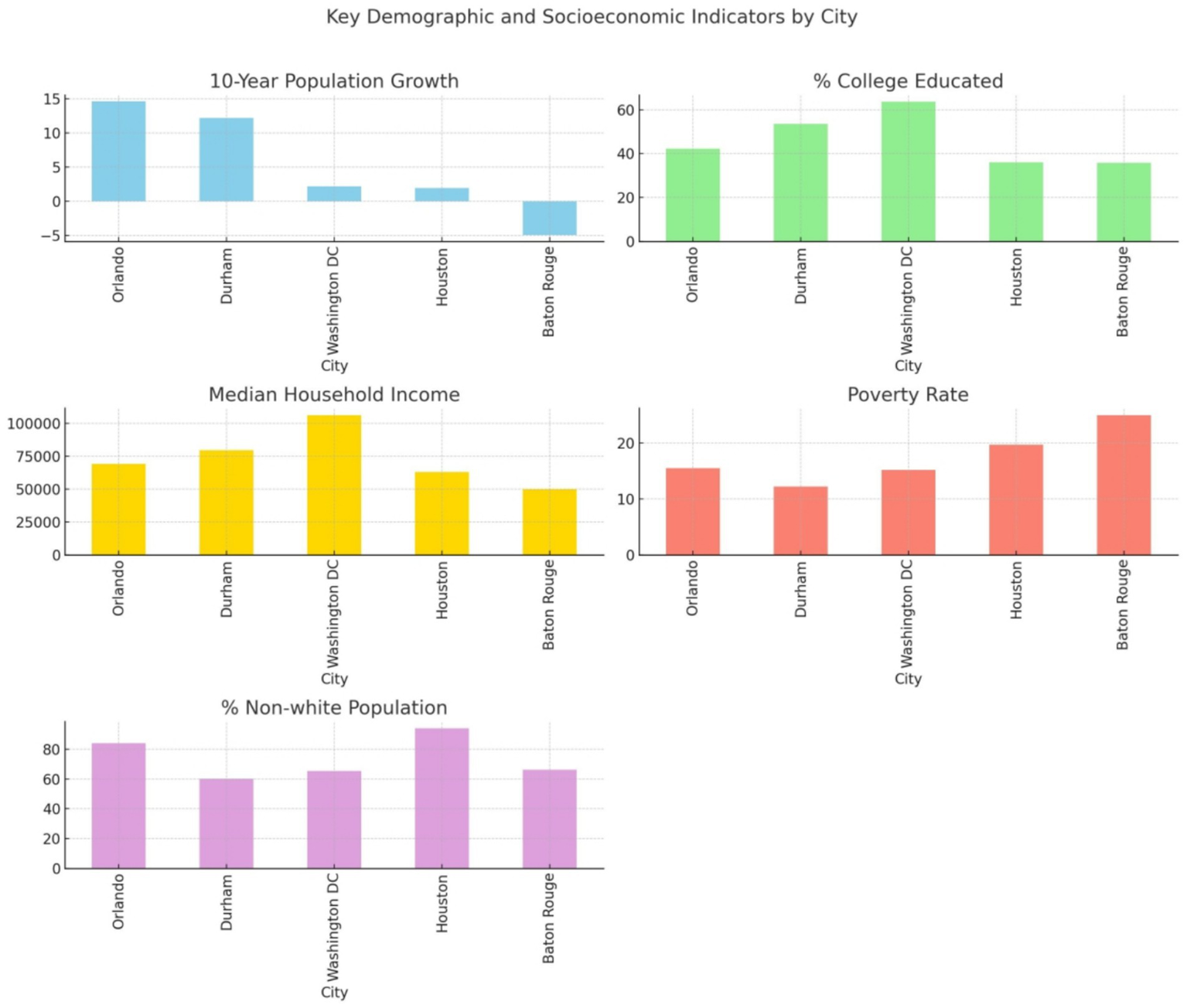

Figure 3 summarizes key demographic differences between the five cities in our sample. The differences in population growth rates are striking with Orlando and Durham showing significant growth over the past 10 years, while Washington, DC and Houston are essentially stagnant, and Baton Rouge experienced declining populations. This is largely due to the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which continues to have implications for the area even today. Education levels and household incomes follow predictably similar patterns with both being exceptionally high in Washington, DC followed by Durham and Orlando. Despite these strong indicators, DC’s unemployment rate is relatively high suggesting a strong bifurcation of the population.

Figure 3

Key demographic and socioeconomic indicators by city.

Compared to the national averages, the five cities in our sample have a higher population of elderly and children under the age of 18 than the national average for metropolitan areas in the US. They also have a higher percentage of non-white residents with a significantly higher foreign-born population. This denotes the need for robust family and youth advocacy services and the importance of immigration-focused legal clinics in these locations, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1

| Indicator/City | Orlando | Durham | Washington DC | Houston | Baton Rouge | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 320,742 | 296,186 | 678,972 | 2,314,157 | 219,573 | 345,426,571 |

| Populations Per Square Mile | 2780.4 | 1133.7 | 11,280.7 | 3598.4 | 2635.3 | N/A |

| % of non-white population | 84.1 | 60.3 | 65.5 | 94.1 | 66.4 | 62,080,044 Hispanic/Latino |

| % of foreign born | 21.6 | 15.2 | 13.3 | 28.8 | 7.4 | 14.3 |

| 10 yr. population growth | 14.6 | 12.2 | 2.2 | 1.9 | −4.93 | 0.98 |

| % of college educated | 42.2 | 53.5 | 63.6 | 36.0 | 35.8 | 36.2 |

| Median household income | $ 69,268 | $ 79,501 | $ 106,287 | $ 62,894 | $ 49,944 | $ 77,719 |

| Per person income | 41,985 | 46,931 | 75,253 | 41,142 | 33,415 | N/A |

| % Children <18 | 27.6 | 26.3 | 24.3 | 30.3 | 27 | 16 |

| % Elderly >65 | 11.1 | 15.1 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 14.2 | 11.3 |

| % Unemployment rate | 3.30 | 3.10 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 4.1 |

| % Poverty Rate | 15.5 | 12.2 | 15.2 | 19.7 | 25 | 11.1 |

Summary of key indicators of five US cities and US (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023a).

The elevated poverty rates in Baton Rouge (25%) and Houston (19.7%), indicate economic precarity which might be addressed through clinics focused on housing, consumer protection, and estate planning. Contrastingly, Washington D. C.’s high levels of educational attainment (63.6%), yet paradoxically a relatively high unemployment rate (6%), suggest that the city’s local economy is highly bifurcated and could potentially benefit from law school clinics that focus on economic justice, labor and employment law, and housing affordability.

Table 2 provides a summary of the development and planning needs identified by the five cities in our sample. Houston and Orlando report the largest number of community priorities with five (5) each. Interestingly, despite the published articles and newly passed laws centered around immigration, Orlando does not target pathways to naturalization as a top development need/goal. Both D. C. and Baton Rouge indicated three (3) identical priorities: housing, public safety, and juvenile justice/youth advocacy. While Baton Rouge and Washington, D. C. differ across nearly every key community indicator, Baton Rouge’s high poverty rate and D. C.’s dearth of affordable housing represent two distinct challenges that ultimately converge on the same outcome – housing insecurity. References to youth development efforts do not appear in the documents that meet the inclusion criteria of our systematic review. They may, however, be contained in more education-oriented documents that were not included in the systematic review development priorities.

Table 2

| Development Need/City | Orlando | Durham | Washington DC | Houston | Baton Rouge | Cumulative needs (of cities w. development need) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | X | X | X | X | X | 5 |

| Business start-ups | X | X | 2 | |||

| Youth development | 0 | |||||

| Immigration | X | 1 | ||||

| Public safety-crime | X | X | X | X | 4 | |

| Juvenile justice reforms | X | X | X | 3 | ||

| Transportation | X | 1 | ||||

| Road infrastructure | X | 1 | ||||

| Education | X | X | 2 | |||

| Economic development | X | X | X | 3 |

Top development needs identified in five US cities.

5.1 Analysis of legal services provided by HBCU law schools

A systematic review of the clinical law programs of the ABA accredited law schools in our sample found that all the schools are committed to a high level of public engagement and representation (see

Akintobi et al. (2025). Using publicly available data our study found evidence regarding the role HBCU law schools play in the following key areas:

“The HBCU law school helps to reduce the displacement/eviction of marginalized communities. The HBCU law school promotes affordable housing, property improvements/repairs for marginalized communities.”

The HBCU law school provides entrepreneurship support, training, or aid in the prevention of loss of generational wealth (i.e., wills and estates).

The HBCU law school advocates for youth under 18 years of age or work on initiatives that aim to reduce youth involvement in the justice system and advocate for alternatives to incarceration.

The HBCU law school helps asylum seekers and/or un-documented immigrants navigate the path to naturalization.

The HBCU law school helps to promote awareness, equitable safety measures and help to reduce disparities in the justice system (Akintobi et al., 2025).

Building on these findings, we further analyzed the specific clinical law programs offered by the law schools in our sample. The analysis follows a case study approach that offers a more in-depth description of the clinical law programs offered at each law school and the populations these programs engage. Since both Howard University and the University of the District of Columbia are located in Washington DC, the case study reviews the six ABA accredited law schools in our sample in order of their location like the previous review of the development and planning needs of each of the five metropolitan areas.

5.2 Florida A&M university college of law

Orlando identified immigration, entrepreneurship/small business growth, and affordable housing as top community development priorities. FAMU Law’s initiatives demonstrate evidence in each of these priority areas but also extend beyond the identified priorities of Orlando. Additional areas the FAMU law clinics cover include family/youth advocacy, crime prevention/ justice reform, and economic justice/generational wealth.

A central feature of FAMU Law’s outreach is the production of a television program called Legal Connections. The program is designed to inform the broader community about pertinent legal issues and available services (Strong, 2019). This recurring collaboration with Orange TV not only enhances public legal literacy but also provides a platform for law students and faculty to translate complex legal concepts into accessible information.

In addition to educational programming, FAMU Law frequently hosts pop-up legal service clinics, offering free, on-the-spot legal assistance to community members (Florida A&M University, 2023a). These clinics address immediate legal needs and exemplify the institution’s commitment to bridging gaps in legal access. Further reflecting its civic engagement, FAMU Law organized a naturalization ceremony for 20 new citizens, highlighting the school’s role in fostering civic participation and supporting immigrant communities (Florida A&M University, 2023b).

FAMU Law’s clinical programs also emphasize social justice advocacy. The Racial Justice Fellows, in collaboration with the law school’s legal clinic, filed an amicus brief challenging Daytona Beach’s anti-panhandling ordinance. The brief contributed a critical First Amendment analysis, providing the court with deeper constitutional context (Florida A&M University, 2024c). This project highlights FAMU Law’s focus on constitutional rights advocacy and its use of clinical education to influence public policy.

Economic justice initiatives are another hallmark of FAMU Law’s outreach. The Economic Justice Clinic provides free legal services to small business owners (Paschall-Brown, 2023), and a significant partnership with Wells Fargo has allowed the law school to launch initiatives specifically targeting support for minority-owned businesses (Charnosky, 2022; Byrnes, 2021). These programs not only promote economic development but also align with FAMU Law’s mission to address systemic inequities through legal interventions.

Additionally, FAMU Law students actively contribute to law reform efforts. Through clinic work, students have engaged in drafting legislation intended to impact the lives of children who are wards of the state (Jones, 2010).

Collectively, these initiatives affirm FAMU Law’s dedication to integrating public service with legal education. Through innovative community outreach, strategic partnerships, policy advocacy, and robust clinical training, FAMU Law exemplifies a model of legal education that is both community-centered and socially conscious.

FAMU Law has a strong alignment with the city of Orlando, Florida in the area of affordable housing and economic development, particularly around the issue of entrepreneurship/small business growth.

5.3 North Carolina central university school of law

The NCCU Law clinical programs demonstrate significant alignment with the City of Durham’s priorities, particularly in the areas of family and youth advocacy, crime prevention, and housing stability. The Juvenile Law Clinic’s direct representation of 23 youth clients during first appearance hearings (North Carolina Central University, 2020), coupled with community engagement initiatives such as providing holiday meals to detained youth (North Carolina Central University, 2022), reflect strong support for Durham’s family and youth advocacy goals.

NCCU Law’s Housing Clinic partners with the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to promote fair housing awareness. This directly addresses the city’s concerns about gentrification and equitable housing access (Hyman, 2024). Through community-focused housing advocacy, the clinic contributes meaningfully to efforts aimed at mitigating displacement pressures in Durham’s rapidly changing neighborhoods.

A successful Civil Litigation Clinic has been able to achieve favorable settlements for clients (Alexander, 2023). The Clinic has also succeeded in filing litigation against local law enforcement for alleged constitutional violations (WRAL, 2015). These efforts demonstrate a commitment to promoting public accountability. While these efforts serve important functions within individual cases, there is limited evidence of broader systemic initiatives aimed at preventing crime at the community level. Expanding into policy reform advocacy or broader systemic interventions could further enhance alignment with Durham’s strategic emphasis on community-based crime prevention.

Specialized services provided by the Elder Law Project (Abernethy, 2023) and the Wills Clinic (Institute, Earl Carl, 2024) reflect a strong commitment to serving vulnerable populations. However, these services are less directly connected to the City of Durham’s core public priorities around youth, crime prevention, and housing stability. Strengthening the linkage between elder legal services and broader anti-displacement strategies could enhance the clinics’ relevance and strategic impact in the local context.

With more intentional development of systemic initiatives and tighter integration of some services in the city’s highest priority areas, the clinics could further amplify their contributions to Durham’s evolving civic goals.

5.4 Howard university school of law

Howard University School of Law (HUSL) has demonstrated a comprehensive approach to community-engaged legal practice, particularly emphasizing civil rights, housing justice, human rights advocacy, and economic justice. However, there are also key priority areas that are not consistently addressed. For example, there is no direct evidence of HUSL clinical program involvement in health equity, which is a priory for the District of Columbia. However, it is important to recognize that health equity is closely linked to factors such as housing, public safety, and economic justice. Therefore, it can be reasonably inferred that by advocating for affordable housing and working to mitigate the negative effects of gentrification—particularly in the District of Columbia—the HUSL clinical programs contribute to advancing health equity through the intersectionality of their initiatives.

HUSL’s clinics have made significant contributions to housing justice. Students from the Fair Housing Clinic collaborated with the D. C. Housing Authority to provide testimony before the D. C. Council Oversight Hearing (Howard University School of Law, 2024a). Additionally, the Law Clinic has engaged in national advocacy by submitting a formal response to HUD opposing a proposed rule that would weaken protections against housing discrimination (Cornelius, 2019). Their commitment to housing rights is further demonstrated through the submission of an amicus brief aimed at safeguarding the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (Crowell NNPA, Charlene, 2015), as well as through direct client services focused on eviction prevention (Habitat for Humanity, 2024).

Beyond housing, HUSL’s clinics address economic justice through specialized legal support. The Intellectual Property Patent Clinic provides inventors with assistance in preparing and filing patent applications under the supervision of licensed attorneys (Howard University School of Law, 2024b). In addition, the Law Clinic offers free estate planning services via student-led clinics supported by external grant funding (Staff, WI Web, 2023).

On the international front, HUSL has leveraged its Human and Civil Rights Clinics to address global issues. The Law Clinic presented to the United Nations on the inclusion of African Americans and marginalized communities in the Sustainable Development Goals (Lawrence, 2023) and signed a petition supporting continued U. S. funding of the International Service for Human Rights (International Service for Human Rights, 2019).

In the area of criminal justice reform, the HUSL Criminal Justice Clinic has engaged in high-impact litigation, including work on People of the State of California v. Ronnie Louvier (Bailer, 2023). Students also secured clemency for a clinic client under President Barack Obama’s administration (Howard Newsroom Staff, 2016). Additionally, the Civil Rights and Human Rights Clinics have drafted amicus briefs in cases challenging racial discrimination, such as Sewell v. State of Maryland (Cornelius, 2020), and filed petitions receiving recognition and dissenting commentary from Justice Sonia Sotomayor (Whitty, 2023).

The Movement Lawyering Clinic has advanced court access advocacy. Students surveyed Prince George’s County’s court system and pushed for more equitable bail practices (Howard University School of Law, 2023). Furthermore, the Clinic advocated successfully for statewide adoption of remote audio-visual access to all public proceedings (Robert, 2023). Students also organized campaigns for local clemency reform, highlighting systemic inequities in clemency processes (Gathright, 2021).

Current efforts in economic justice are promising but largely centered on patents and estate planning. Broader initiatives supporting small businesses, consumer rights, or workforce development could extend HUSL’s economic justice impact.

HUSL has aligned its top priorities with the District of Columbia around affordable housing, economic justice, and justice reforms.

5.5 University of the district of Columbia David A. Clarke school of law

The UDC David A. Clarke School of Law (UDC Law) demonstrates alignment with Washington, DC’s equitable development priorities. This is particularly evident in the areas of affordable housing, and health equity, while also contributing to entrepreneurship indirectly through economic justice work. UDC Law’s Community Development Clinic directly addresses affordable housing needs by representing housing cooperatives (Opara, 2023d). In a city where gentrification and housing affordability are key issues, the clinic’s support for co-op models helping low- and moderate-income residents maintain stable and affordable housing options is a critical intervention against displacement.

The Special Education Clinic now Youth Justice Clinic (Scholefield and Tulman, 2015) conducts educational interventions for at-risk youth, ensuring students with disabilities receive appropriate educational support, an important factor in breaking cycles of marginalization. Similarly, the Legislation Clinic’s initiative to provide menstrual supplies for women in shelters and schools (School, Stanford Law, 2019) not only addresses basic health equity needs but also advocates for dignity and access for vulnerable populations.

The Youth Justice Clinic further supports family and youth advocacy through direct services. Students teach paralegal courses to detained youth (Opara, 2023e), advocate for youth facing long-term suspensions (Israel, 2014), and assist with name and gender marker changes for transgender youth, promoting social inclusion and mental health (Opara, 2023e).

The Immigration and Human Rights Clinic significantly contributes to health equity and stability for marginalized residents by securing asylum for vulnerable individuals, obtaining work permits for residents facing homelessness, and dismissing deportation proceedings (Opara, 2023c; Harris, 2018). These interventions allow clients to access healthcare, employment, and housing, which are foundational to long-term well-being.

The Criminal Defense and Racial Justice Clinic supports family stability and economic security by hosting expungement clinics for DC residents (Opara, 2023a), helping individuals remove barriers to employment and housing caused by criminal records, aligning with DC’s emphasis on reentry and community reintegration.

The Tax Clinic’s assistance during calendar calls (Opara, 2023b) strengthens economic stability by helping clients navigate complex tax issues, although it is less directly tied to traditional definitions of entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, stable financial footing is a critical prerequisite for entrepreneurship, especially among underrepresented communities.

While UDC Law’s clinics cover family/youth advocacy, affordable housing, there is less direct evidence of programming focused on entrepreneurship. Current efforts, such as tax advocacy and economic justice work, lay the groundwork for entrepreneurship but could be expanded through more targeted business formation support or small business clinics to match DC’s growing entrepreneurial ecosystem. In addition, although the clinics serve many health equity-related needs (e.g., through immigration and education advocacy), a more explicit focus on public health law, mental health advocacy, or healthcare access could further reinforce UDC Law’s leadership in client focused clinical law programs that advance g health equity across diverse communities.

Like HUSL, UDC Law has aligned its top priorities with the District of Columbia in the areas of affordable housing, juvenile justice reforms, and economic justice.

5.6 Texas Southern university Thurgood Marshall college of law

The TSU Law clinical programs demonstrate strong alignment with several of Houston’s critical civic needs, particularly in the areas of immigration, family and youth advocacy, economic justice, and the preservation of generational wealth. The Wills, Probate, and Guardianship Clinic directly addresses the city’s focus on economic justice and generational wealth by assisting a high volume of clients—managing between 40 and 70 cases per semester, with 8–10 students each handling 5–7 cases (Institute, Earl Carl, 2024). Estate planning services are vital in Houston, where economic disparities are deeply racialized and wealth preservation among historically marginalized communities is essential to closing the racial wealth gap.

The Law Clinic’s partnership with other Houston law schools and organizations to provide continuing education for lawyers representing undocumented minors (PR Newswire, 2014) is a strong response to Houston’s significant immigrant population. The city is a hub for immigrants, and protecting the rights of unaccompanied youth supports broader family stability.

Additionally, the TSU Immigration Clinic’s $1 million grant to represent clients in naturalization proceedings (Texas Southern University, 2023) addresses critical needs in immigration, civic engagement, and economic integration. By facilitating lawful status and citizenship, TSU Law helps combat displacement, promote economic participation, and foster community stability. Finally, TSU Law’s Immigration Clinic helps to reduce the backlog of immigration cases in the Houston court system.

However, while TSU Law’s clinical programs are clearly impactful at the individual level, there is limited evidence of engagement with systemic advocacy strategies that could influence broader structural change in Houston. Given the city’s pressing needs in areas like affordable housing and displacement, health equity, injury and damage litigation, environmental justice, and entrepreneurship support, TSU could expand its clinical work to include policy advocacy, strategic litigation, and targeted collaborations with grassroots movements. Additionally, while collaboration is a strength, more formal tracking and public reporting of community outcomes would enhance the clinics’ visibility and demonstrate measurable contributions to Houston’s systemic challenges.

TSU Law clinical programs have a strong alignment with the city of Houston, Texas in the areas of affordable housing and public safety crime.

5.7 Southern university law center

The Southern University Law Center (SULC) addresses Baton Rouge’s identified community priorities in the areas of affordable housing, economic justice, family and youth advocacy, and crime prevention.

The Disaster Recovery Clinic provides direct legal services to individuals facing housing insecurity following natural disasters, such as (WAFB Staff, 2016; Southern University Law Center, 2024a). By assisting clients with relief applications, insurance claims, and recovery aid, SULC is directly contributing to Baton Rouge’s focus on affordable housing and stabilizing vulnerable populations affected by environmental challenges. Given Louisiana’s recurring exposure to natural disasters, this clinic fulfills an ongoing need in the community.

The SULC Technology and Entrepreneurship Clinic and the broader Entrepreneurship Clinic initiatives also support economic justice. By helping form 33 new businesses and serving 140 clients (Travis, 2022) and by donating essential equipment like printers to graduates of entrepreneurship programs (St. John the Baptist Parish, 2021), SULC fosters local entrepreneurship and wealth-building opportunities. Small business support is crucial to Baton Rouge’s broader strategies for reducing poverty and enhancing economic self-sufficiency among historically marginalized communities.

Family and youth advocacy are also supported through SULC’s partnership with the Louisiana Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), where legal services such as expungements and tax credit assistance are provided to individuals facing systemic barriers to stability (Department of Children and Family Services, 2020). The expungement services align with the city’s crime prevention goals, helping remove legal obstacles that limit employment, housing, and educational opportunities for individuals with criminal records.

Additionally, the wills and estate clinic hosted by (Southern University Law Center, 2024c) contributes to preserving generational wealth and promoting economic justice — a critical step in closing racial wealth gaps that persist across Baton Rouge.

However, while SULC’s clinics clearly align with many of the city’s urgent needs, there is an opportunity to more explicitly integrate environmental justice advocacy into its portfolio, especially given Louisiana’s vulnerability to environmental degradation and climate risks. Current disaster recovery efforts are vital but could be complemented by systemic initiatives, such as advocating for stronger environmental protections or representing communities affected by industrial pollution.

SULC Law has a strong alignment with the city of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, focuses on affordable housing, public safety crime, and juvenile justice reforms.

Table 3 summarizes the clinical law programs offered at the six ABA accredited law schools. Howard, UDC and Southern offer a particularly robust scope of programs followed by North Carolina and Florida. Overall, the clinical law programs are well aligned with the needs of their communities, and possibly even overperform especially with respect to youth programming.

Table 3

| Program focus Law school | FAMU | NCCU | HUSL/ UDC | TSU | SULC | Cumulative # of Law Schools | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Business/Economic Justice | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Youth Development | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Immigration | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Safety/policing | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 |

| Family Law | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Estates Wills/Trusts | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Civil Rights | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Tax | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

Summary of the programmatic priorities of the 6 HBCU law schools.

6 Conclusion

Our systematic review of publicly available development and planning documents in five US cities, namely (1) Orlando, Florida, (2) Durham, North Carolina, (3) Washington, D. C., (4). Houston, Texas, and (5) Baton Rouge, Louisiana identified not only top development priorities but a recurring theme of equitable development goals across the five cities. The reason these cities were selected is that they are home to six (6) ABA accredited law schools at HBCU institutions of higher learning. A comparison between the development priorities of the five cities and the clinical law programs offered at the six law schools finds several close alignments, but also some divergent trends.

Table 4 summarizes the programmatic offerings and services for the HBCU law schools included in the study and illustrates that the clinical law programs were well aligned with community priorities of the cities in our sample. There are, however, some notable misalignments. For example, FAMU Law provides advocacy services in the majority of the areas the community indicated as key development priorities. However, we did not find evidence that FAMU provides services that can assist in addressing transportation challenges despite the fact that this is a high priority area for Orlando. On the other hand, SULC’s clinic addresses all three of Baton Rouge’s development needs plus four additional areas that are relevant, albeit not necessarily a top priority.

Table 4

| Development Need/City | Orlando/FAMU | Durham/NCCU | Washington DC/HUSL/UDC | Houston/TSU | Baton Rouge/SULC | Cumulative needs ()/Programs () | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | 5 | |

| Business start-ups | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Youth development | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | 6 | |||||

| Immigration | X | X | X | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Public safety-crime | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 4 | 6 | |

| Juvenile justice reforms | X | X | X | X | X | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| Transportation | X | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Road infrastructure | X | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Education | X | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Economic development | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 3 | 4 | |||

Summary of equitable development needs and clinical law programs in selected US cities.

Two gaps stand out as they reveal programming that goes beyond the development priorities identified by the cities. This is particularly true for Washington, D. C., which has the benefit of two accredited HBCU law schools whose programs both overlap and complement each other.

Some limitations of the study must also be acknowledged. They include the reliance on publicly available documents which may not fully capture the scope of the development priorities of the five cities examined. Similarly, further research may reveal additional services provided by the law schools in our sample that are not evident from their publicly available documents. The reliance on publicly available data may have the potential of introducing bias since not all development priorities or clinical law program offerings may be fully captured in the data. To offset this potential bias, we engaged in triangulation of our data using other available sources to corroborate our findings. Lapan et al. (2012) suggested that triangulation of data increases the reliability and trustworthiness of the findings (p. 246). Future research might add interviews or focus groups with relevant stakeholders from both the cities and law schools to further enrich the analysis and reveal additional areas where the clinical law programs support the development priorities of their communities. Moreover, our study focused on the ABA accredited law schools at HBCUs given their historical commitment to relevant service that benefits the communities and local stakeholders where the law schools are located. Additional research regarding the development contributions of law schools in general may provide further insights regarding the community relevance of law schools in general. Merriam (1995) provided guidance on strategies that strengthen reliability and validity of research in that the user will determine its use and application. This study incorporated the four strategies identified by Merriam to strengthen external validity. These include (a) a detailed description of the law schools (b) multisite design describing all six of the ABA accredited law schools and their legal clinics, (c) describing in detail each of the clinical legal programs and comparing each program across community impact indicators, and a case-by-case examination of the number of clinical legal programs and describing their legal offerings within their respective communities.

Despite these limitations, the study highlights the critical role HBCU law schools play in supporting the equitable development efforts of historically underserved urban areas in the US and particularly in the southern states. It contributes to the growing recognition that community-based legal education can serve as essential civic infrastructure, advancing inclusive and just urban transformation beyond traditional redevelopment models.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

AA: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Project administration, Conceptualization, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Validation. SO’H: Project administration, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation. EH: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JB: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aaronson D. Hartley D. Mazumder B. (2021). The Effects of the 1930s HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol.13, 355–392. doi: 10.1257/pol.20190414

2

Abernethy M. (2023). Law School Pro Bono Service Award: NCCU School of Law Elder Law Project–North Carolina Bar Association. Available online at: https://www.ncbar.org/member/focus/law-school-pro-bono-award-nccu-school-of-law-elder-law-project/ (Accessed June 12, 2023).

3

ACLU of Florida . (2024). Federal Court Temporarily Blocks Key Provision of Florida’s Anti-Immigrant SB 1718. American Civil Liberties Union (blog). Available online at: https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/federal-court-blocks-floridas-anti-immigrant-sb-1718 (Accessed May 22, 2024).

4

Akintobi A. Harrison E. O’Hara S. Brittain J. (2025). Community Cornerstones: An Analysis of HBCU Law School Clinical Programs’ Impact on Surrounding Communities.

5

Alexander A. (2023). Salisbury, Rowan Settle Suit with Elderly Woman Who Was Pulled by Hair at Police Stop. Charlotte Observer. Available online at: https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/crime/article279863834.html (Accessed September 28, 2023).

6

American Association of Law Schools . (2017). “Association of American Law Schools - Section on Clinical Legal Education Glossaary for Experiential Education.” Available at: https://www.aals.org/app/uploads/2017/05/AALS-policy-Vocabulary-list-FINAL.pdf.

7

American Bar Association . (2024). ABA Profile of the Legal Profession. Available online at: https://www.americanbar.org/news/reporter_resources/profile-of-profession/.

8

American Immigration Council . (2024). Take a Look: How Immigrants Drive the Economy in Florida. American Immigration Council, 2024. Available online at: https://map.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/locations/florida/.

9

Archer D. N. (2025). Dividing lines: how transportation infrastructure reinforces racial inequality. W. W. Norton.

10

Arnstein S. R. (2019). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association; Vol 85, No 1 - Get Access. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01944363.2018.1559388

11

Bailer B. (2023). Howard University Law Students Campaign Against the Criminalization of Hip-Hop. The Dig at Howard University. Available online at: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/howard-university-law-students-campaign-against-criminalization-hip-hop (Accessed December 11, 2023).

12

Bloomgarden A. H. (2017). Out of the armchair: about community impact. Int. J. Res. Serv. Learn. Community Engagem.5, 21–23. doi: 10.37333/001c.29752

13

Boustan L. P. (2010). Was Postwar Suburbanization ‘White Flight’? Evidence from the Black Migration. Q. J. Econ.125, 417–443. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2010.125.1.417

14

Brigida A. C. (2024). Houston Is Experiencing a Serious Lack of Immigration Lawyers, a Trend Seen Nationwide. Available online at: https://houstonlanding.org/houston-is-experiencing-a-serious-lack-of-immigration-lawyers-a-trend-seen-nationwide/ (Accessed February 1, 2024).

15

Butterfield F. (2000). Settling Suit, Louisiana Abandons Private Youth Prisons. New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast), September 8, 2000, sec. A.

16

Byrnes J. (2021). FAMU College of Law Will Begin Initiative to Support Minority-Owned Businesses with Grant from Wells Fargo. Central Florida Public Media. Available online at: https://www.cfpublic.org/2021-11-16/famu-college-of-law-will-begin-initiative-to-support-minority-owned-businesses-with-grant-from-wells-fargo (Accessed November 16, 2021).

17

Charnosky C. (2022). Florida A&M Law Launches Economic Justice Initiative to Support Minority-Owned Businesses. Daily Business Review. Available online at: https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/2022/03/22/florida-am-law-launches-economic-justice-initiative-to-support-minority-owned-businesses/. (Accessed March 22, 2022).

18

City of Durham . (2023). HUD Annual Funding Documents Durham, NC, 2023. Available online at: https://www.durhamnc.gov/4607/HUD-Annual-Funding-Documents.

19

City of Durham . (2024). City of Durham Strategic Plan | Durham, NC, 2024. Available online at: https://www.durhamnc.gov/183/City-of-Durham-Strategic-Plan.

20

Cornelius M. (2019). Howard Law Students, Faculty Experts Respond to HUD’s Move to Restrict Fair Housing Regulations. The Dig at Howard University. Available online at: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/howard-law-students-faculty-experts-respond-huds-move-restrict-fair-housing-regulations. (Accessed October 28, 2019).

21

Cornelius M. (2020). Howard University’s Clinical Law Center Calls out Racial Discrimination in Sewell v. State of Maryland. The Dig at Howard University. Available online at: https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/howard-universitys-clinical-law-center-calls-out-racial-discrimination-sewell-v-state-maryland (Accessed April 10, 2020).

22

Cresswell J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

23

Crowell NNPA, Charlene . (2015). Supreme Court to Review Fair Housing Law: [3]. University Wire, Politics. Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1771568092/abstract/E3D1BDDF7A3A4CE9PQ/1 (Accessed February 15, 2015).

24

DC Policy Center . (2023). D.C. Voices: Juvenile Justice - D.C. Policy Center. Available online at: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/dc-juvenile-justice/ (Accessed November 1, 2023)

25

De Marco A. Hunt H. (2018). Racial Inequality, Poverty and Gentrification in Durham, North Carolina Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute. Available online at: https://fpg.unc.edu/publications/racial-inequality-poverty-and-gentrification-durham-north-carolina.

26

Department of Children and Family Services . (2020). Southern University Law Center, DCFS Enter Poverty Innovation Project Louisiana Department of Children and Family Services. Available online at: https://www.dcfs.louisiana.gov/news/southern-university-law-center-dcfs-enter-poverty-innovation-project (Accessed February 21, 2020).

27

Department of Energy and Environment . (2024). Equity Sustainable DC. Department of Energy and Environment. Available online at: https://sustainable.dc.gov/equity.

28

Dreier P. (2003). The future of community reinvestment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc.69, 341–353. doi: 10.1080/01944360308976323

29

Dsouza N. (2022). Exploring residents’ perceptions of neighborhood development and revitalization for active living opportunities. Prev. Chronic Dis.19:33. doi: 10.5888/pcd19.220033

30

FBI Crime Data Explorer . (2024). CDE. Available online at: https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/query.

31

Ferreira F. Kenney J. Smith B. (2024). Household mobility, networks, and gentrification of minority neighborhoods in the United States. J. Labor Econ.42, S61–S94. doi: 10.1086/728805

32

Florida A&M University . (2023a). Law News Releases. Available online at: https://law.famu.edu/newsroom/news-releases/famu-law-offers-pop-up-legal-clinic-designed-to-help-underserved-residents.php (Accessed January 10, 2023).

33

Florida A&M University . (2023b). Law News Releases. Available online at: https://law.famu.edu/newsroom/news-releases/new-citizens-welcomed-at-naturalization-ceremony-at-famu-law.php.

34

Florida A&M University . (2024a). About Us. Available online at: https://law.famu.edu/about-us/index.php.

35

Florida A&M University . (2024b). Consumer Information (ABA Required Disclosures). Available online at: https://law.famu.edu/aba-consumer-info.php.

36

Florida A&M University . (2024c). Spotlight. Available online at: https://law.famu.edu/spotlight.php.

37

Fussell E. Harris E. (2014). Homeownership and housing displacement after hurricane Katrina among low-income African-American mothers in new Orleans. Soc. Sci. Q.95, 1086–1100. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12114

38

Garsd J. (2024). A Year Later, Florida Businesses Say the State’s Immigration Law Dealt a Huge Blow. National NPR. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2024/04/26/1242236604/florida-economy-immigration-businesses-workers-undocumented (Accessed April 26, 2024).

39

Gathright J. (2021). Advocates Say New D.C. Clemency Rules Give Too Much Power To The Feds. DCist (blog). Available online at: https://dcist.com/story/21/09/11/dc-clemency-proposed-regulations-rules-statehood/. (Accessed September 11, 2021).

40

Giuliani T. (2024). Advancing Orlando’s Future: Why 2025 Legislative Priorities Matter | Orlando Economic Partnership. Available at: https://news.orlando.org/blog/advancing-orlandos-future-why-2025-legislative-priorities-matter/.

41

Gómez E. M. (2023). Memory in analog: analyzing the impacts of rapid urban growth on youth. Hum. Organ.82, 369–381. doi: 10.17730/1938-3525-82.4.369

42

Gough D. Thomas J. Oliver S. (2012). Clarifying Differences between Review Designs and Methods. Systematic Reviews1:28. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

43

Graham H. (2007). Unequal Lives. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

44

Green R. D. Kouassi M. Mambo B. (2013). Housing, race, and recovery from Hurricane Katrina. Rev. Black Polit. Econ.40, 145–163. doi: 10.1007/s12114-011-9116-0

45

Groark C. J. McCall R. B. (2018). Lessons learned from 30 years of a university-community engagement center. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engage.22, 7–29.

46

Grossman G. S. (1973). Clinical Legal Education: History and Diagnosis. J. Leg. Educ.26, 162–193.

47