Abstract

Urban heat island (UHI) is the phenomenon where urban areas possess higher temperature than its surrounding rural areas. The present review examines the factors contributing to the UHI effect and the challenge faced by Indian cities in the context of environmental sustainability and health by referring to the literature of more than 40 cities between 2005 and 2023. The present study reviewed already available research which utilizes remote sensing techniques to study the UHI. This study mainly includes satellite data studies; while some fixed station studies, field observations and instrument measurement studies were also incorporated. The current scenario of UHI research in India highlights that the larger cities are studied the most and the smaller but developing cities still need to be explored for the UHI research. The identified key drivers of UHI are vegetation loss, impervious surface, unplanned urban agglomeration, anthropogenic heat and aggravated energy consumption. Different methods have been studied including different simulation techniques used in UHI research. Furthermore, the present review highlights how India can advance towards creating a more resilient, sustainable, and healthful urban environment through integration of green infrastructure, and execution of policies such as Heat Action Plan (HAP) aimed at mitigating UHI impacts. Finally, this study highlights future key directions to examine understudied UHI layers, i.e., Atmospheric and canopy layer UHI, smaller or medium sized urban centers and encouraged to study the region-specific factors such as topography, morphology and socio-economic factors in order to facilitate sustainable and resilient urban planning in India.

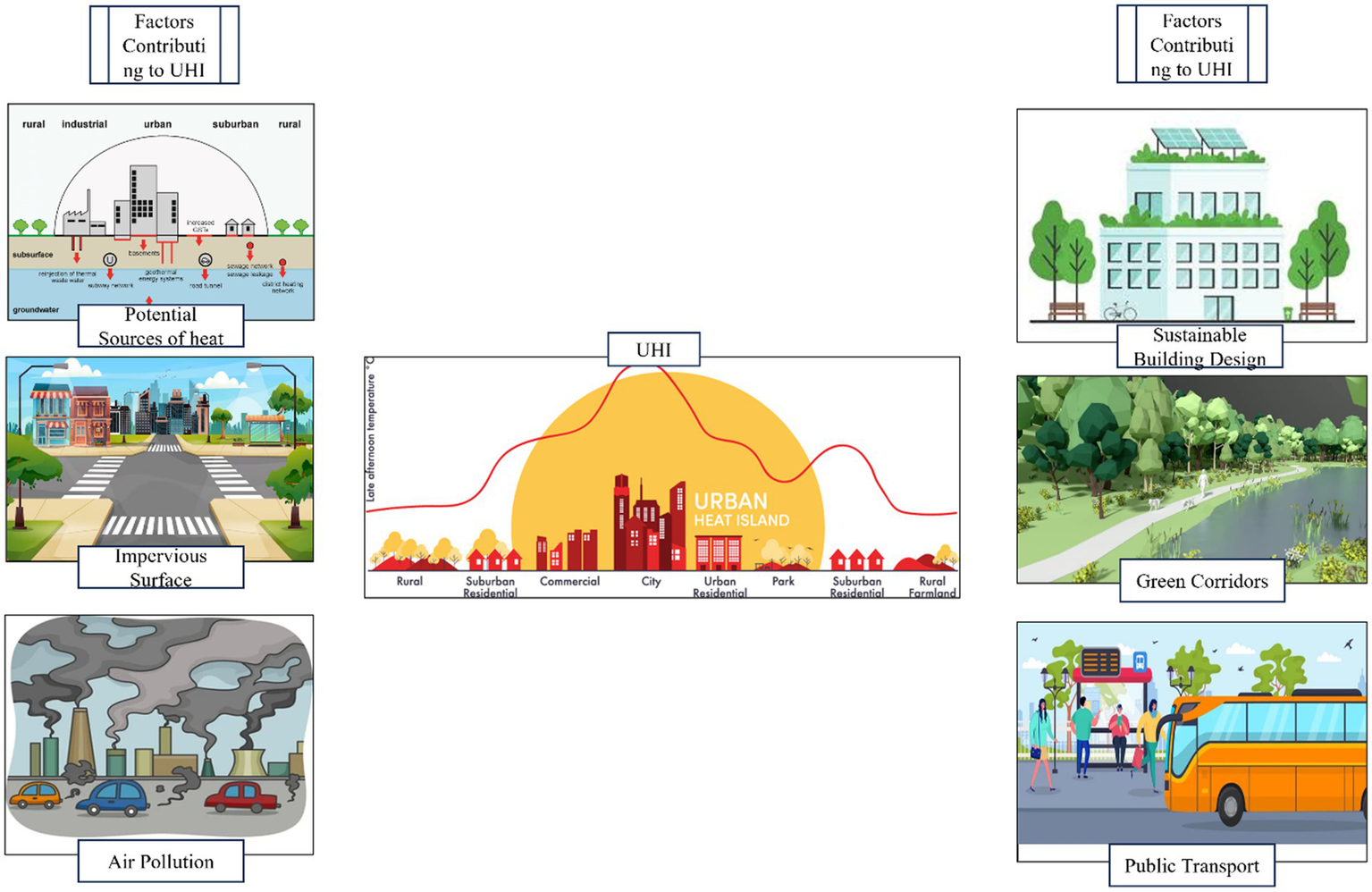

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

Systematic review of UHI research on over 40 Indian cities (2005–2023).

Urban areas exhibit higher temperatures than surrounding rural regions (0.5–10 °C).

Primary drivers are vegetation loss, high energy consumption, urban expansion and anthropogenic emissions.

Green infrastructure and urban planning mitigate UHI effects.

Policies like Heat Action Plan in India enhance urban climate resilience.

Integration of field-based observations and simulation models will enhance predictive capabilities.

Need to study UHI in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities and the need to study AUHI and CLUHI.

1 Introduction

The increased temperature of a city as compared to the surrounding rural settlements due to the presence of impervious surfaces and human activities, which results in the generation of a few or several heat pockets, is known as the UHI effect (Zhang et al., 2009). Luke Howard is the pioneer of urban climatic studies. Many scientists succeeded his study and carried out various experiments, which led to an understanding of the advanced urban environment (Heisler and Brazel, 2010; Stewart, 2019). UHI effect is one of the consequences of anthropogenic activities such as the prevalence of dark, non-reflective surfaces in urban settlements (Islam et al., 2024).

Urbanization and rapid economic development have led to significant changes in the physical environment of cities, which in turn has contributed to urban climate change (Kim and Brown, 2021). It is estimated that in the next four decades, 80% of the global population will live in urban areas (United Nations, 2014; Zhang, 2016; Hoornweg and Pope, 2017). Unbalanced urban expansion between cities due to a significant population influx has resulted in a marked difference in the urban form and services of the core and periphery of cities. Key difficulties include the expansion of slums, poor solid waste management, declining per capita water supply, erratic water quality, insufficient sewage coverage, and decreasing ambient air (Nandi and Gamkhar, 2013; Ghosh and Kansal, 2014). Rapid urbanization alters land use land cover (LULC) of an area which greatly influences the UHI; particularly with reference to reduced vegetation cover (Mohan and Kandya, 2015; Hassan et al., 2021). Hence, LULC change is one of the most effective ways to predict the extent of the effect of urban agglomeration on UHI (Gohain et al., 2023; Das et al., 2024). According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021), since the 1900s, the global surface temperature has increased by 0.74 °C and will continue to increase under all the current emission scenario up to 1.5 °C. Although the two phenomena are affected by each other, the urban climatic environment is directly and densely affected by global climate change (Kuttler, 2008; Misslin et al., 2016). Extreme heat wave events that are observed in urban areas are the result of this interaction (Basara et al., 2010; Rizvi et al., 2019). The higher temperature in urban areas compared to surrounding sub-urban and rural areas prompts increased energy consumption and health-related issues (Imam and Banerjee, 2016). Human influences have warmed the climate at an unprecedented rate as it has strengthened since Assessment Report 5 (AR5) (IPCC, 2021). Heat stress is perhaps the biggest climate threat to human health (Saeed et al., 2021; Jabbar et al., 2023). UHI has increased heat exposure numerous times particularly in urban areas (Yadav et al., 2023; Boyaj et al., 2024). Urbanization demands enhanced built-up activity in order to ensure residential areas and infrastructure for the rapidly rising population; thus, bringing about changes in the atmospheric conditions (Landsberg, 1981; Bai et al., 2017; Upreti et al., 2024). This leads to detrimental environmental degradation such as reduced precipitation, decreased soil infiltration capacity, increased runoff, decreased water table, and changes in surface albedo, which further imbalance the earth’s radiation (Veena et al., 2020; Kabisch et al., 2023). Emitted greenhouse gases (GHGs) are trapped in the atmosphere as a result of this disruption in the earth’s radiation and the growing number of automobiles and industries in urban regions. This exacerbates the UHI effect in densely populated places (Ramanathan and Feng, 2009; Irfan et al., 2024). Climate change and UHI affect each other by interacting and producing heat waves during extremely hot weather, exposing citizens to heat stress. Studies suggest synergy between climate change and UHI (Santamouris et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2020). The UHI effect poses a risk to human health (Cichowicz and Bochenek, 2024).

To create more resilient and sustainable city environments—cool roofs, urban greening (green roof, community parks, urban forestry), sustainable building designs, reduced impervious surface, innovative technologies (radiative paints, smart windows and BIPVs) and policy driven actions (heat action plan and certifications) are few of the strategies that work together to lower the urban temperature and improve the air quality as well. These are discussed in detail in the later section of the review.

Metropolitan cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Lucknow, Bengaluru and Chennai with high and compact populations have been extensively studied for UHI status in India (Pandey et al., 2009; Pandey et al., 2012; Mohan et al., 2012; Yadav et al., 2020; Gautam and Singh, 2018; Mohan et al., 2020; Mukherjee and Debnath, 2020; Mishra and Mathew, 2022; Shahfahad et al., 2023; Khan and Chatterjee, 2016; Bhowmick et al., 2023; Halder et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2017; Sarif and Gupta, 2019; Shukla and Jain, 2021; Verma and Garg, 2021; Ramachandra and Kumar, 2010; Sussman et al., 2019; Naidu and Chundeli, 2023, Devadas and Rose, 2009, Jeganathan et al., 2014, Amirtham, 2016; Kesavan et al., 2021, Rajan and Amirtham, 2021; Muthiah et al., 2022). Smaller cities and towns have received less research attention, leaving the UHI pattern and mitigation in such areas underexplored. Formation of heat pockets were concentrated towards the city centre. Temperature differences between the core and suburbs of cities range between 2 °C and 10 °C (Memon et al., 2009; Pandey et al., 2012; Sharmin et al., 2015; Vardoulakis et al., 2013; Tam et al., 2015; Rajan and Amirtham, 2021; Siddiqui et al., 2021; Islam et al., 2024). Diurnal studies revealed that commonly observed differences in temperature in the UHI effect are 10 °C during the night and 3–4 °C during the day (Tam et al., 2015; Azevedo et al., 2016; Mathew et al., 2018). Maximum UHI is recorded within a few hours of the sunset as the built-up structures release their stored heat from the daytime during this hour (Tzavali et al., 2015; Heisler and Brazel, 2015; Lai et al., 2018).

From social and economic viewpoints, it is observed that low-income residents are more likely to dwell in areas with high UHI intensity and are more subjected to heat-related severe problems (Bradford et al., 2015; Debnath et al., 2023). Factors like spatial factors, temporal factors, anthropogenic factors, and geographic factors supports UHI intensities (Deilami et al., 2018). The physical characteristics and layout of urban areas, such as the amount of green space, building density, and land use patterns are referred to as spatial factors (Aijaz, 2016). Temporal factors, on the other hand, are related to variations in UHI intensity due to changes over time, such as seasonal shifts and alterations in daily weather patterns (Siddiqui et al., 2021). Analysis of the diurnal, seasonal and annual changes and trends in land surface temperature and surface UHI intensity (SUHII) have been extensively examined for Indian cities like Lucknow, Pune, Kolkata and Jaipur were studied. These investigations reported an overall maximum average UHI intensity of 7.86 °C in Jaipur. The nighttime mean annual SUHI intensity ranged between 1.34 °C and 2.07 °C (Mathew et al., 2017; Siddiqui et al., 2021). Human activities such as deforestation and emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) that contribute to UHI formations are considered anthropogenic factors (Feng et al., 2012; Nica et al., 2019). Not only this, various geographical factors need to be taken into account while studying UHI (Grover and Singh, 2015; Mishra and Mathew, 2022). These factors might include the existence or absence of hilly terrains, the wind flow in the region as well as the presence of water bodies in the vicinity of urban areas (Collier, 2006).

Spatial data is used to study the pattern of urbanization and its development as well as its impact on UHI formation as built-up surfaces directly influence land surface temperature (Morabito et al., 2016; Mukherjee et al., 2017). Temporal data are crucial for monitoring the intensity and variability of UHI as it helps to study the phenomenon for various time scales and hence helps in understanding the full dynamics of temperature patterns and its driving forces (Tan, 2024). This review includes studies based on Remote sensing analyses, observational studies using instrument and fixed station, GIS-based studies, simulations modelling. The goal is to develop an insight into UHI and the methodologies used to study its factors affecting UHI, its impact and mitigations strategies.

1.1 Aims and objectives

The literature review aims to identify a future scope of UHI estimation in India by analyzing the present scenario and to determine the variables; besides evaluating their impact on UHI formation. Tools and methods were a major focus of this study based on the research carried out in India so far. This will help in understanding the trends of existing studies related to the magnitude and estimation of UHI. The study targets the following points:

-

To investigate current scenario of UHI research in India

-

To develop knowledge base of the methods of study use for estimation of UHI

-

To identify the research gap within the UHI domain that still that require further investigation

1.2 Structure of current review

The present review has four segments: the first section is Introduction which gives insights on the topic and related research that are being conducted in that field. The second section is the Materials and Method that explains the process of review; starting from searching with the keywords on various databases to the final selection and extraction of paper. The third section is Results and Discussion section that presents a comprehensive analysis of the UHI estimation in terms of techniques, dependent and independent variables; besides describing critical trends or gaps identified in the literature; and the fourth and final section includes the Conclusion, that summarizes the major findings, research gaps and thus provides future scope.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Bibliographic databases

This study utilizes a standard approach for the literature review to identify relevant papers on a particular topic of interest (in this case, UHI) by searching comprehensively on Scopus, Springer, Nature, and Science Direct as the main bibliographic databases. Since 2004, Scopus has been the largest database available, having the largest number of peer-reviewed journals and covering a wide range of disciplines, including urban climatology, environmental science, geography, and many more. These databases have a collection of scholarly articles as well as convenient and customized filters that can be used to sort research papers based on scientific criteria, language (English) a combination of keywords (Table 1), publication year (1999–2023), and subject area (Environmental science, energy, earth and planetary science). The initial data collected from Springer, Nature, Scopus, and Science Direct contained 1,655 publications, contributing 683, 42, 155, and 775, respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1

| Keywords | K1-UHI | K2-Estimate K3-Calculate K4-Quantify |

K5-Magnitude K6-India K7-LST K8-LULC K9-NDVI K10-NDBI |

K11-Impact K12-Health K13-Mitigation K14-Analyse |

K15-Satellite data K16-Remote sensing K17-Google Earth engine |

| Combinations | C1 K1 and K2 C2 K1 and K3 or K4 or K14 C3 K1, K5 and K6 C4 K1, K7, K8 C5 K1, K11, K12 and K13 C6 K1 and K2, K1 and K3 or K4 or K14 and K15 or K16 C7 K1 and K17, K7 and K17, K9, K10 and K17 |

||||

Terms and combinations used to perform SLR.

Figure 1

Flowchart of systematic literature review.

2.2 Search criteria

UHI was set as the constant base of the search, and along with it, keywords like India, LST, LULC, NDVI, NDBI, analysis, estimation, impact, health, mitigation, satellite data, remote sensing, and the Google Earth Engine were used in combination to refine the research process. Following research questions were addressed while screening the papers: (a) What are the factors that elevate the UHI effect? (b) What is the impact of UHI on human life? (c) What are the latest techniques to estimate UHI? (d) What could be the possible planning and mitigation techniques to combat UHI?

2.3 Screening and selection processes

By referring to the exclusion and inclusion criteria (whether the study was directly related to the magnitude and intensity of UHIs; and if not, does it relate to the UHI accompanying factors such as LST, LULC, NDVI, NDBI), duplicates were removed by checking the key bibliographic details or different version of the same study such as preprints, conference paper or only abstract and considering only the research articles having relevance to the topic of UHI in the Indian context were screened, narrowing down the numbers to 486 research articles. Furthermore, the papers were reduced to 208 by reviewing the keywords and abstracts that were relevant to the topic and the full text of the few of them were not available.

2.4 Final screening and analysis

In the final process of screening and selecting articles, 208 papers were critically studied excluding off-topic or incomplete studies, leaving 124 research articles on the list for in-depth study because of the robustness of their methodology and offers new insights to the field. Based on their relevance, quality, and methodology, further, these articles underwent filtering; where the quality depends upon the clear presentation of results. By fulfilling the criteria and answering the research questions, only 89 articles were found to evaluate UHI using satellite data and geospatial technologies that directly answers the research questions and provide actionable and impactful findings. Hence, these 89 studies were considered for the final review process as they provided valuable insights into the UHI phenomenon in India and its impact on health, energy consumption, air pollution, and overall environmental sustainability (Figure 2). These articles presented potential mitigation strategies as well as the importance of remote sensing and GIS in the UHI study.

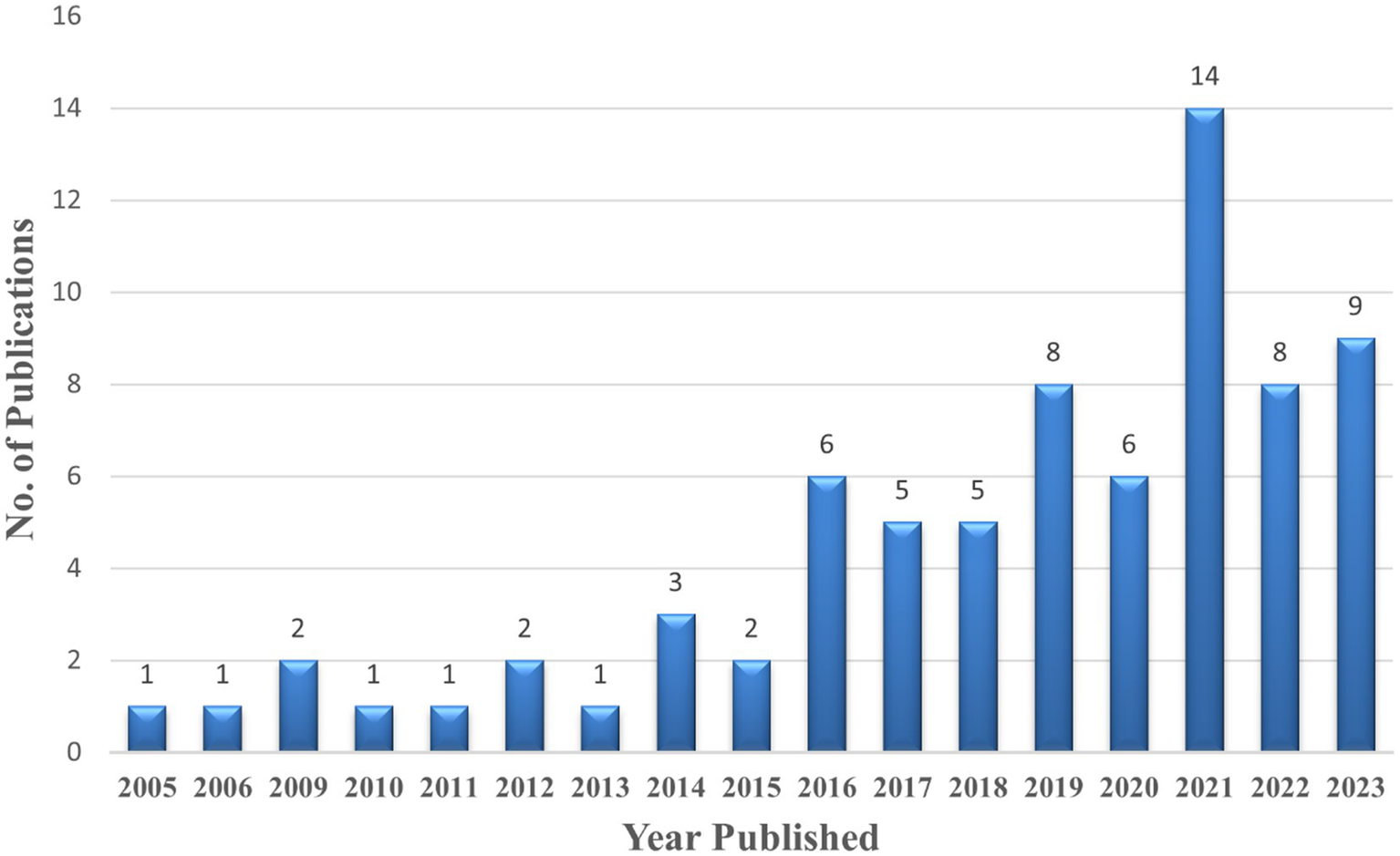

Figure 2

Number of publications during 2005–2023.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of publications which indicates the heightened interest of scientific community in the UHI phenomenon. Several factors such as rising urbanization, climate change, public health concerns, technological advancement and policy making can attribute towards this trend.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 UHI estimation

Most studies on UHIs in India predominantly focus on megacities; which results in a gap in UHI research for smaller cities and towns, that remain underexplored. A review of UHI studies based on their geographical location reveals that UHI studies have a significant concentration in Delhi, the capital of India and a highly urbanized city, accounting for 13.33% of the total studies (Pandey et al., 2009; Pandey et al., 2012; Mohan et al., 2012; Yadav et al., 2020; Gautam and Singh, 2018; Pramanik and Punia, 2020; Mohan et al., 2020; Mukherjee and Debnath, 2020; Mishra and Mathew, 2022). Similarly, Chennai covers 8% of the studies (Devadas and Rose, 2009; Jeganathan et al., 2014; Amirtham, 2016; Kesavan et al., 2021; Rajan and Amirtham, 2021; Muthiah et al., 2022); followed by Lucknow that comprised 5.3% (Singh et al., 2017; Sarif and Gupta, 2019; Shukla and Jain, 2021; Verma and Garg, 2021). On the other hand, Bengaluru (Ramachandra and Kumar, 2010; Sussman et al., 2019; Naidu and Chundeli, 2023), and Kolkata covers 4% each of the total review (Khan and Chatterjee, 2016; Bhowmick et al., 2023; Halder et al., 2021).

Although this review includes the UHI estimation studies dating back to 2005; however, 2019 onwards, a significant number of studies regarding UHI estimation have been carried out (Figure 2). Not only the UHI estimation, but these studies also focused on the main types of UHI, i.e., Atmospheric UHI (AUHI) and Surface UHI (SUHI); besides Canopy layer UHI (CLUHI) and Boundary layer UHI (BLUHI). It was observed that only 9.33% of the studies focused on AUHI; 2.6% on CLUHI, while the rest of 88% of the studies dealt with SUHI. This disparity in UHI studies focusing more on megacities as well as higher emphasis on SUHI necessitates the need for a holistic approach towards studying the UHI phenomenon. As AUHI remain under-represented, atmospheric dynamics remain underexplored because of the high cost of the measurement devices (Zhou et al., 2023). Atmospheric dynamics are better understood when AUHI studies are done as it provides reveals the vertical and horizontal distribution of heat and also helps forecasting heat waves by enhancing the result. For a deeper comprehension of how cities affect the climate system, the AUHI effect is essential (Mathew et al., 2023).

The disproportionate focus on megacities and SUHI necessitates more evenly distributed research to fully understand UHI. Additionally, studying the effects of UHI on urban planning, public health, and climate resilience is critical for developing comprehensive mitigation strategies. Future research should encompass diverse metropolitan areas and investigate all UHI types to address these knowledge gaps and provide a more holistic understanding of UHI dynamics.

3.2 Factors elevating UHI

Urbanization demands concrete infrastructure to adjust increasing population which in turn, contributes to the anthropogenic heat addition (Jiang and Wei, 2024). Studies show that growing populations coincide with rising energy use, which accelerates the development of built-up regions and the loss of open places (Ullah et al., 2023). Building materials used to create new infrastructure often decreases the Earth’s albedo (Syros et al., 2024). Due to significant decrease in vegetation, caused by land use and land cover changes; rate of evapotranspiration is greatly affected. Buildings and impervious surfaces increase aerodynamics resistance which leads to decreased energy transfer from surface to the lower atmosphere and elevated near surface atmosphere, ultimately increasing the UHI (Li et al., 2019). Hence, infrastructure, anthropogenic heat addition, decrease in Earth’s albedo, reduced evapotranspiration and decreased energy transfer are the focus of the study to mark out their contribution in elevating UHI effect. In the cities like Delhi, aerosol distribution and presence of Yamuna River also contributes to the elevated surface temperature as aerosol play a role in scattering of radiation and the water body acts as heat sink which retains the heat during day and releases it slowly at night (Pandey et al., 2009). UHI phenomenon is highly affected by topography and urban morphology; urban location like Visakhapatnam having hills and valleys which probably affects the air circulation and heat distribution. The amount of heat emitted and absorbed by the city depends a lot on its urban density and arrangements of the building (Devi, 2006). Further, urban environments are significantly impacted by building morphology. Nevertheless, little is known about the relationship between building morphology and urban surroundings at various scales and times of year. In Beijing, there was a substantial relationship between building form and air temperature. Besides, building shape had a significant impact on relative humidity while building volume density had biggest effect on air temperature (Cao et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2025).

3.3 Impacts of UHI on human life

In summers, UHI effect is reported prominently which increases the energy demands and consumption and to meet these demands, conventional form of energy is used, resulting in greenhouse gas emissions. The greenhouse gas traps the radiating energy making the near surface air warmer. This causes local Hadley’s type of circulation which in turn creates the difference in spatial temperature of urban and sub-urban areas (Rao, 2014). This difference of temperature is popularly termed as UHI which is a local phenomenon. Studies have shown increased health risk due to heat waves in urban population as compared to sub-urban population because the UHI effect is observed in most of the urban settlement (Heaviside et al., 2017). Heat related illness and heat stroke are commonly found in urban settlements having high UHI effect. In the social strata; vulnerable social groups are more affected by health risks imposed by hot weather as they lack proper amenities to protect themselves. Ground-level pollution is magnified at places affected by UHI which can together cause respiratory discomfort, disturbance in consciousness, heat stroke, aggravated cardiovascular and neurological diseases (Khare et al., 2021). UHI worsen the air pollution as it adds to the building up of the dust dome and haze of contaminants which causes recirculation of pollutants (Devi, 2006). Bad air quality can exacerbate respiratory illness like bronchitis and asthma (Pandey et al., 2009). Increasing UHI effect can cause water stress in urban areas as the it raises the demand of water for cooling purposes (Muthiah et al., 2022).

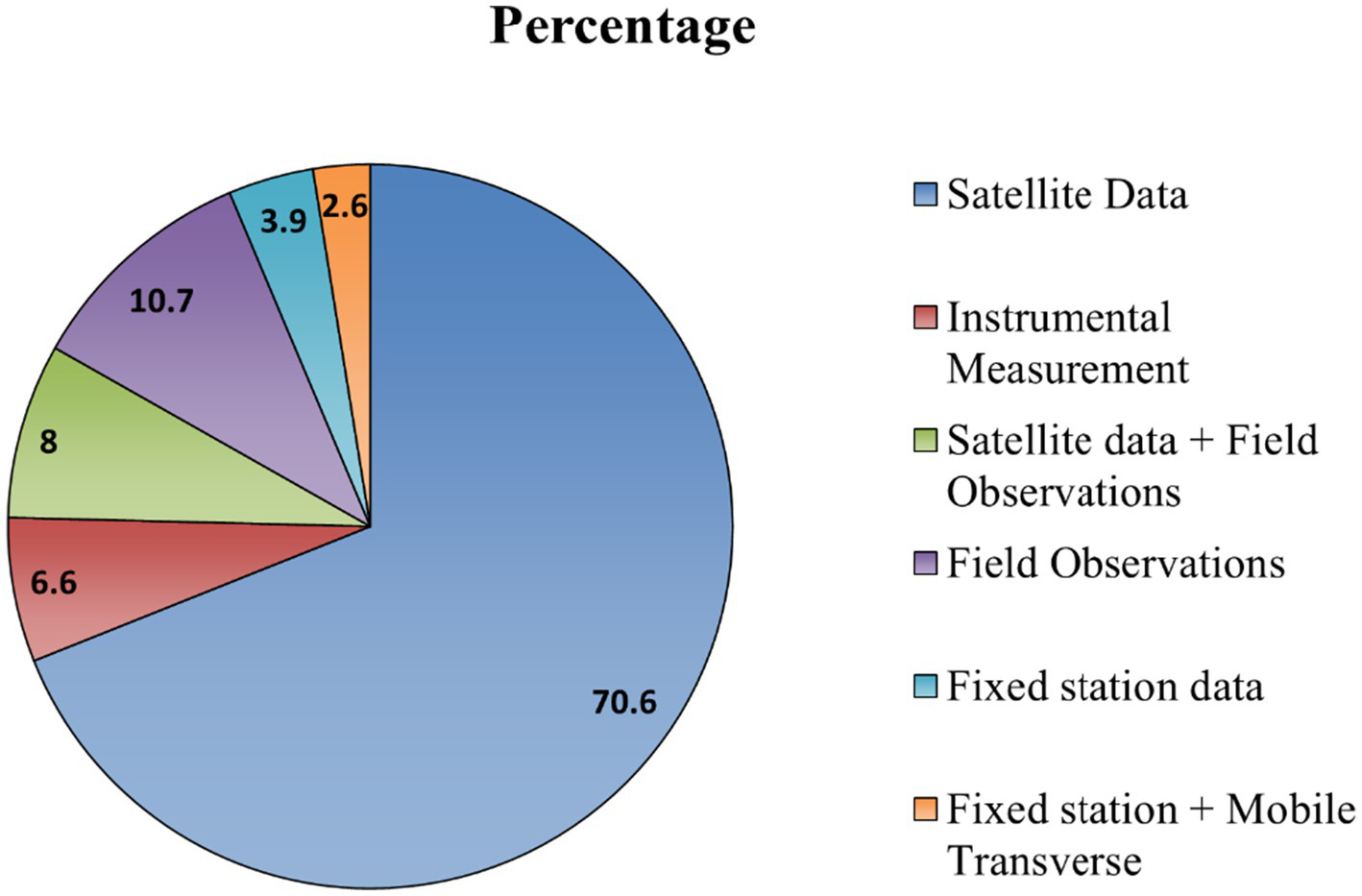

3.4 Datasets and techniques used for UHI estimation

In the current times, the main platform for measuring Earth’s physical and biophysical properties is a satellite, that makes use of electronic sensors digitally. MODIS and Landsat datasets are widely used for the estimation of UHI (Joshi et al., 2015; Jamal et al., 2023; Kaur and Pandey, 2020; Ramachandra and Kumar, 2010; Sussman et al., 2019; Naidu and Chundeli, 2023; Singh et al., 2023a; Kumar, 2022; Sethi et al., 2023; Barat et al., 2018; Khan and Bera, 2020; Mathew et al., 2016; Sahoo et al., 2022; Kesavan et al., 2021; Muthiah et al., 2022; Mishra and Garg, 2023; Pandey et al., 2009; Pandey et al., 2012; Gautam and Singh, 2018; Pramanik and Punia, 2020; Mohan et al., 2020; Mukherjee and Debnath, 2020; Mishra and Mathew, 2022; Neog, 2023; Choudhury et al., 2023; Bhowmick et al., 2023; Halder et al., 2021; Veettil and Grondona, 2018; Singh et al., 2017; Sarif and Gupta, 2019; Shukla and Jain, 2021; Verma and Garg, 2021; Dutta and Das, 2020; Kaur and Pandey, 2020; Shahfahad et al., 2023; Mukherjee et al., 2017; Chandrakar and Sinha, 2021; Sharma and Kale, 2022; Badugu et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2021; Vani and Prasad, 2019; Devi, 2006; Puppala and Singh, 2021; Kikon et al., 2016; Kedia et al., 2021; Chatterjee and Gupta, 2021). Throughout the review process, it was observed that approximately 71% of studies employed satellite datasets (Figure 3). Out of the total papers reviewed, only 8% utilized satellite data supplemented with field observations. Studies relying solely on field observations accounted for 10.7%, while 6.6% of the studies employed instrument measurements. Estimation based on fixed station data and mobile transverse together makes 3.9% of the entire study.

Figure 3

Methods of UHI study.

Although achieving 100% accuracy is not possible, when it comes to remote sensing data analysis, automatic image processing techniques are not adequate. Field observations are valued because they entail human interpretation, which includes point-by-point approach perception, concept development, and reformation (Bhatta, 2011). Therefore, studies integrating satellite data with field observations or ground truthing are considered more authentic and reliable.

Thermal remote sensing techniques are applied globally for UHI studies. According to the literature reviewed, the most used remote sensors in UHI studies include the Thematic Mapper (TM) on Landsat 4–5, the Enhanced Thematic Mapper (ETM+) on Landsat 7, the Thermal Infrared Sensors (TIRS) on Landsat 8–9, MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer), ASTER (Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer), AWiFS (Advanced Wide Field Sensor), and LISS-3 (Linear Imaging Self-Scanning Sensor 3) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Sensor | Satellite | Spatial resolution | Temporal resolution | Total no. of bands | Thermal band no. | Wavelength of thermal bands (μm) | Data availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM | Landsat 4 | 30 m (Resampled) | 16 days | 7 | 6 | 10.4–12.5 | 1982–1993 |

| TM | Landsat 5 | 30 m (Resampled) | 16 days | 7 | 6 | 10.4–12.5 | 1984–2011 |

| ETM+ | Landsat 7 | 30 m (Resampled) | 16 days | 8 | 6 | 10.4–12.5 | 1998–Present |

| TIRS1 | Landsat 8 | 30 m (Resampled) | 16 days | 11 | 10 & 11 | 10.6–12.5 | 2013–Present |

| TIRS2 | Landsat 9 | 30 m (Resampled) | 16 days | 11 | 10 & 11 | 10.6–12.5 | 2021–Present |

| MODIS | Terra | 1 km (approx) | Twice daily | 36 | 20, 22, 23, 29, 31 | 10.7–12.27 | 1999–Present |

| MODIS | Aqua | 1 km (approx) | Twice daily | 36 | 20, 22, 23, 31, 32 | 10.7–12.27 | 2002–Present |

| ASTER | Terra | 90 m | Twice daily | 14 | 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 | 8.125–11.65 | 1999–Present |

| AWiFS | Resourcesat 1 | 56 m (nadir),70 m (field edge) | 5 days | 4 | 2003–2013 | ||

| LISS 3 | Resourcesat 1 | 24 m | 24 days | 4 | 2003–2013 |

Commonly used remote sensors in UHI studies.

Various methodologies employed in UHI studies have been illustrated in Figure 3. These include utilizing satellite data, instrument measurements, fixed station data and field observations independently, data from satellite and field observations in combination; along with fixed station data and mobile transverse data. As the review indicates satellite data is used predominantly in majority of the studies because it offers extensive spatial coverage, temporal consistency, and accessibility.

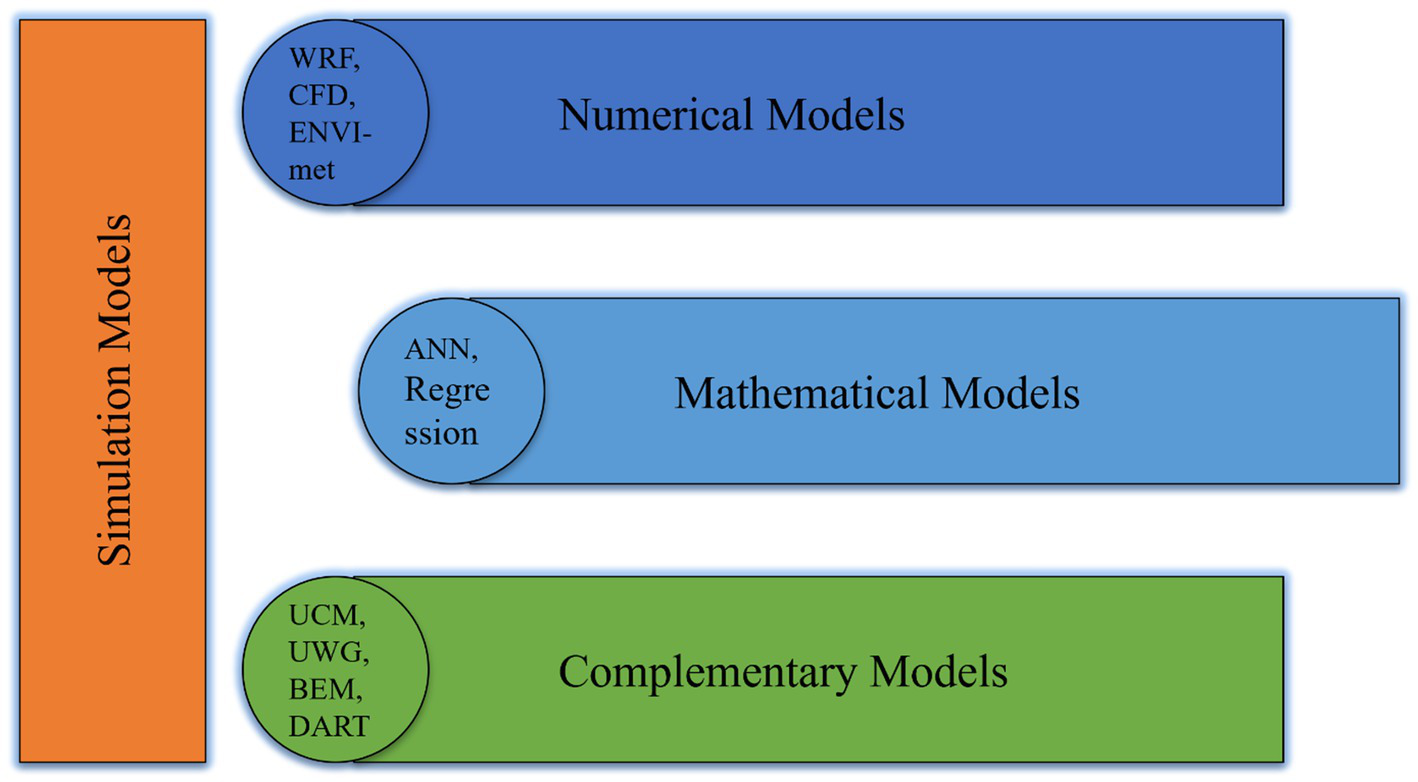

3.5 Simulation techniques for UHI

The urban climate has multiple scales, i.e., Micro-scale, Meso-scale and Macro scale models (Balany et al., 2020; Mathew et al., 2024). Various simulation models are used to study different urban environment at contrasting scales as required (Xu et al., 2020; Imran et al., 2021). Simulation models are effective methods for analysing, forecasting, and refining UHI abatement methods (Balany et al., 2020; Susca and Pomponi, 2020, Adilkhanova et al., 2022). As compared to observational analysis, simulation techniques have some benefits as they allow us to compare multiple parameters for better analysis (Li and Bou-Zied 2014; Yang et al., 2016; He et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021). Researchers can evaluate the mechanism by using modeling tools that underlies UHI effect on meteorological variables to assess the significance of various cause and effect relationship between the phenomenon hence help in finding the solutions (Khan et al., 2020; Imran et al., 2021; Assaf and Assaad, 2023). This section examines the various simulation model types used in UHI studies (Supplementary Table S1). It seeks to summarize three primary simulation models: Numerical Models, Mathematical models and Complementary models (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Different types of simulation models.

3.5.1 ENVI-met

It is a high-resolution 3D modelling program that proficiently simulates complicated microclimatic phenomena with a resolution of 5 M or less which enables detail analysis (Liu et al., 2021; Cortes et al., 2022). Sastry et al. (2013) carried out field surveys and verified findings using the microscale model ENVI-met software to examine how vegetation, water bodies, and reflecting materials affect urban hotspots and established a good correlation. This software evaluates indices like PET (Physiological Equivalent Temperature) and UTCI (Universal Thermal Comfort Index) and identifies areas with heat stress and suggest interventions to enhance comfort (Ziaul and Pal, 2021). Kotharkar and Dongarsane (2024) studied UHI effect and thermal stress in Nagpur using ENVI-met software. It helped map thermal conditions by measuring comfort indices like Air temperature (AT), PET and UTCI and highlighted that nighttime heat stress needed more focus in the study area (Kotharkar and Dongarsane, 2024).

3.5.2 Computational fluid dynamics model

It is an efficient simulation tool which is used to analyze air flow, heat transfer and other physical phenomena in complex environments like urban areas (Ku and Tsai, 2024). To solve the equation governing cutaways and thermodynamics, it employs numerical methods and algorithms. It is popular for modelling in micro weather conditions like wind patterns around the building as it creates virtual simulation of air flow (Islam et al., 2024). Although by coupling it with larger scale weather model, we can predict air movements on both micro and mesoscale, including complex city layouts (Kadaverugu et al., 2021). Studies shows the potential of CFD for urban climate studies, specifically UHI circulation illustrated by connecting mesoscale and microscale physics and the results highlight how urban design (building height, porosity, and heat flux) can reduce the consequences of UHIC (Wang and Li, 2016). Popular CFD software are CFX, ANYSYS, Phoenics, Fluent and OpenFOAM (Wang and Li, 2016; Islam et al., 2024). CFD simulation is gaining popularity globally but remain limited in India (Veena et al., 2020).

3.5.3 Weather research and forecasting model and urban canopy model

It is widely used for predicting and simulating atmospheric phenomena at various scales from local to global (Zhu and Ooka, 2023; Sussman et al., 2024). This model highlights how urban surfaces contribute to the UHI effects and also studies how LULC configuration affect the UHI intensity (Morini et al., 2018). It can be incorporated with complementary models such as urban canopy models (UCM) and building energy models (BEM), to simulate urban climate dynamics, which help in assessing the impact of urbanization and building designs on temperature patterns (Mughal et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2023a; Singh and Sharston, 2023). Aslam et al. (2017) used the Advanced Research WRF (ARW) model (version 3.7) to assess how Delhi’s ground heat flux, wind speed, and UHI changed during the day. Mughal et al. (2020) coupled WRF with multilayer urban canopy model (MLUCM) to evaluate mitigation scenario such as cool roofs and adjusting thermostat settings. We can use this model to experiment and implement the urban plans virtually for simulating outcomes to better understand and anticipate their potential results (Morini et al., 2018; Mughal et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2023a). Another model is Urban canopy model which is a computational tool which stimulates the interaction between urban infrastructures and the atmosphere. In UCMs, unlike CFD the airflow model is separated from the energy budget equations (Mirzaei, 2015). It captures the effect of buildings, roads and other surfaces as canopy and their effect on energy, momentum and moisture exchange (Joshi et al., 2025). UCM coupled with WRF is one of the popular simulation models used in urban environment studies to simulate urban meteorological conditions during the summer and winter period (Li et al., 2019; Ding and Chen, 2024; Prasad and Satyanarayana, 2024).

3.5.4 Statistical models

These models are mathematical framework that used to analyse data, identify trends, relationships and hence based on the observed patterns; infer prediction (Hoffmann et al., 2012; Jato-Espino, 2019). To interpret relationships between variables, they rely on statistical techniques like regression, co relations, machine learning and probability theory (Mathew et al., 2019; Tehrani et al., 2024). Studies demonstrate its utility in analysing the critical link between urban landscape changes and LST increments for densely populated urban areas (Mohan et al., 2022; Gupta and Aithal, 2024). These models need a vast amount of data to train a model (Ashtiani et al., 2014).

3.5.5 Urban weather generator model

It simulates urban climate dynamics by integrating data (urban canopy air temperature and humidity) from nearby weather stations and neighbourhood scale energy balances (Bueno et al., 2013; Salvati et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2022). It estimates local hourly urban canopy air temperature and humidity profiles and analyses the influence of urban layouts and vegetation on UHI intensity (Zhang et al., 2024; Ye et al., 2025). The density of buildings and the amount of vegetation on the urban site must be homogenous in order to get accurate results (Salvati et al., 2017). It is mostly coupled with other models to get improvised results such as convolutional neural network (CNN) (Ye et al., 2025). UWG model is good for studying UHI as it can generate regional meteorological files within a shorter time frame (Ach-chakhar et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025).

3.5.6 Building energy model (BEM)

BEM simulates and analyses the energy performance of buildings (Reeves et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2023; Manapragada and Natanian, 2025). Factors like heat transfer, energy consumption and thermal comfort within urban environment can be assessed using this model (Pan et al., 2023; Joshi and Teller, 2024). In order to accurately model energy usage, these tools examine important parameters including geometry, materials, occupant behaviour, and equipment utilization. Additionally, they assist in identifying and putting energy-saving measures into practice (Sun et al., 2017; Cellura et al., 2017; Manapragada and Natanian, 2025). It is usually coupled with other models such as WRF and town energy balance model (TEB) and CFD (Singh and Sharston, 2023; Joshi and Teller, 2024; Manapragada and Natanian, 2025).

3.5.7 Discrete anisotropic radiative transfer model (DART)

DART is a 3D simulation model designed to study radiative transfer of the complex environment particularly how surfaces and structure interact with solar (shortwave) radiation and thermal (longwave) emissions in urban areas (Zhen et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). By incorporating detailed surface materials and vegetation properties, DART can model mean radiant temperature (Tmrt) at various scales which helps to identify urban hotspots and areas requiring intervention (Dissegna et al., 2021). It can study optical properties such as reflectance, emissivity, leaf area index, leaf area density to enable their thermal behaviour simulation (Sari, 2021; Zhang et al., 2025).

4 Mitigation strategies for countering UHI and recommendations for India

There is growing body of literature suggesting that microclimate is directly affected by the exacerbation of global temperatures (Yang and Chen, 2020). UHI mainly increases the urban environmental temperature and air pollution, in addition; it highly impacts the energy consumption, heat mortality and reduced health quality (Liu et al., 2021). To address the adverse effects of UHI, mitigation measures must be implemented.

In India, summer temperatures can reach up to 50° C, and the average annual global irradiance received by most parts of the country is 5,000 Wh/m2/day or more (Ramachandran and Jain, 2011). Thus, India being a tropical climatic and rapid urbanizing country offers a great potential for implementing environmental and non-environmental measures to counter the UHI effect. Various studies have proposed different mitigation strategies, categorizing them into roof, non-roof, and covered parking strategies (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b; Rajagopal et al., 2023; Elhabodi et al., 2023). Broadly, these measures may be categorized into passive cooling, active cooling, and urban planning interventions.

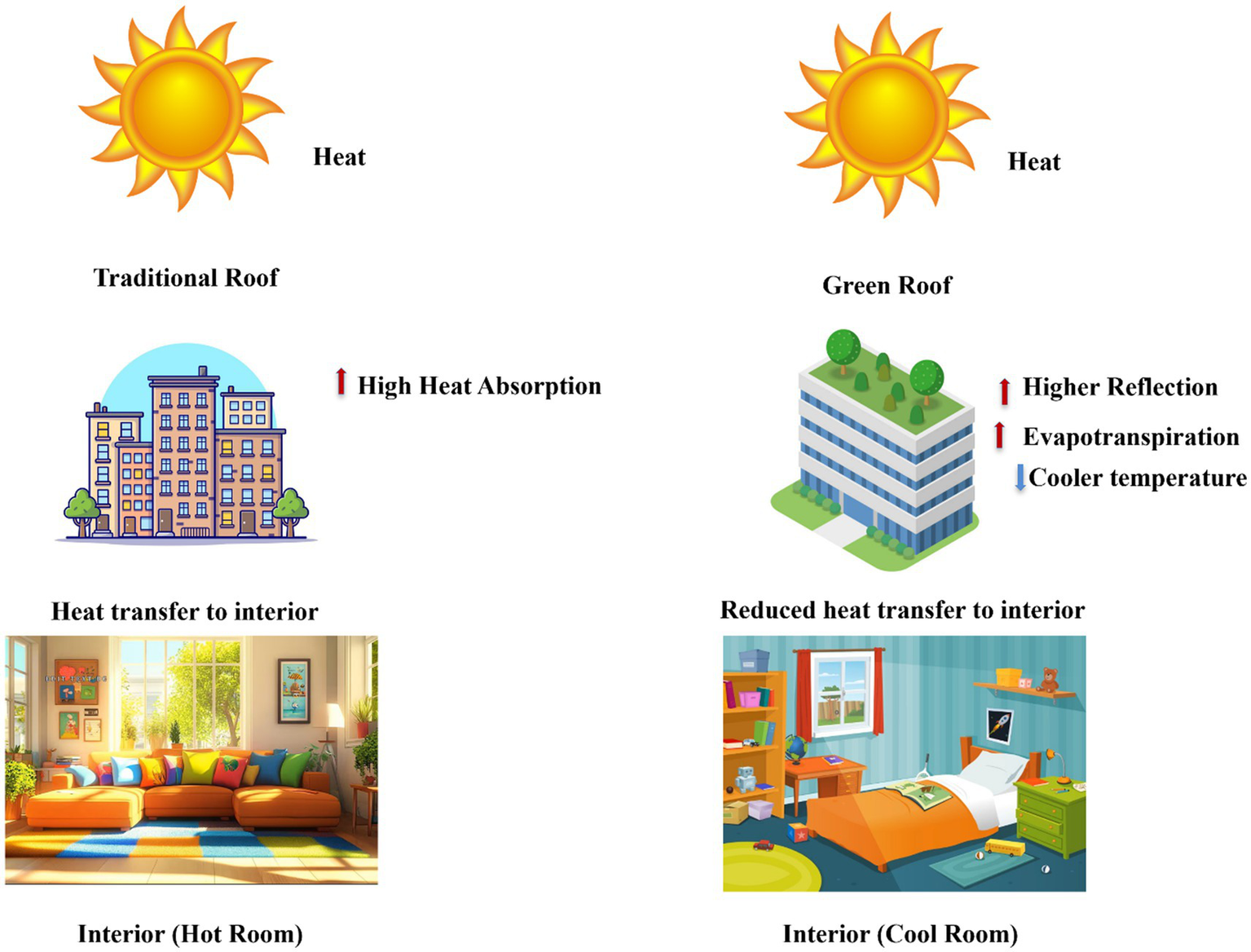

Environmental measures such as increasing urban vegetation by creating green walls, green roofs, green parks and urban forestry is one of the best passive cooling strategies besides utilizing cool materials such as reflective roofs and pavements to minimize surface temperatures (Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). Green roofs are partially or fully vegetated roofs and growing medium, installed over waterproof membrane (Khare et al., 2021). Expanding green areas not only ameliorates evaporation capacity, which lowers near-surface air temperatures, but also counteracts the UHI effect, improves poor air quality and regulates temperature (Santamouris and Osmond, 2022), as shown in Figure 3. Reducing impervious surfaces also helps lower near air and surface temperatures, thus, aiding in UHI mitigation. Sustainable roof solutions like green roofs, which involve insulating spaces with a vegetative layer on the rooftop, have proven effective. Studies have demonstrated that installing green roofs can reduce indoor temperatures by upto 5.1 °C when combined with solar thermal shading (Kumar and Kaushik, 2005); depending on insulation, roof design, and other building-specific factors. It contributes to lower energy costs for cooling, improved comfort for building occupants, and a decrease in the overall UHI effect as the vegetation cover over the rooftop reduces the surface temperature and thereby reduces the temperature of the building interior (Figure 5). This happens due to evaporation and increased surface reflection.

Figure 5

Green roof combating UHI.

Another category of passive strategies are cool pavements and roofs. Compared to traditional materials, these surfaces are made to reflect more sunlight and absorb less heat. Applying high-albedo materials or reflective coatings can drastically lower surface temperatures, which will lessen heat storage and radiative heating of the urban atmosphere. According to studies, depending on local climate conditions and urban morphology, the widespread use of cool surfaces can reduce urban temperatures by 1–3 °C (Larsen, 2015; Zhou et al., 2022).

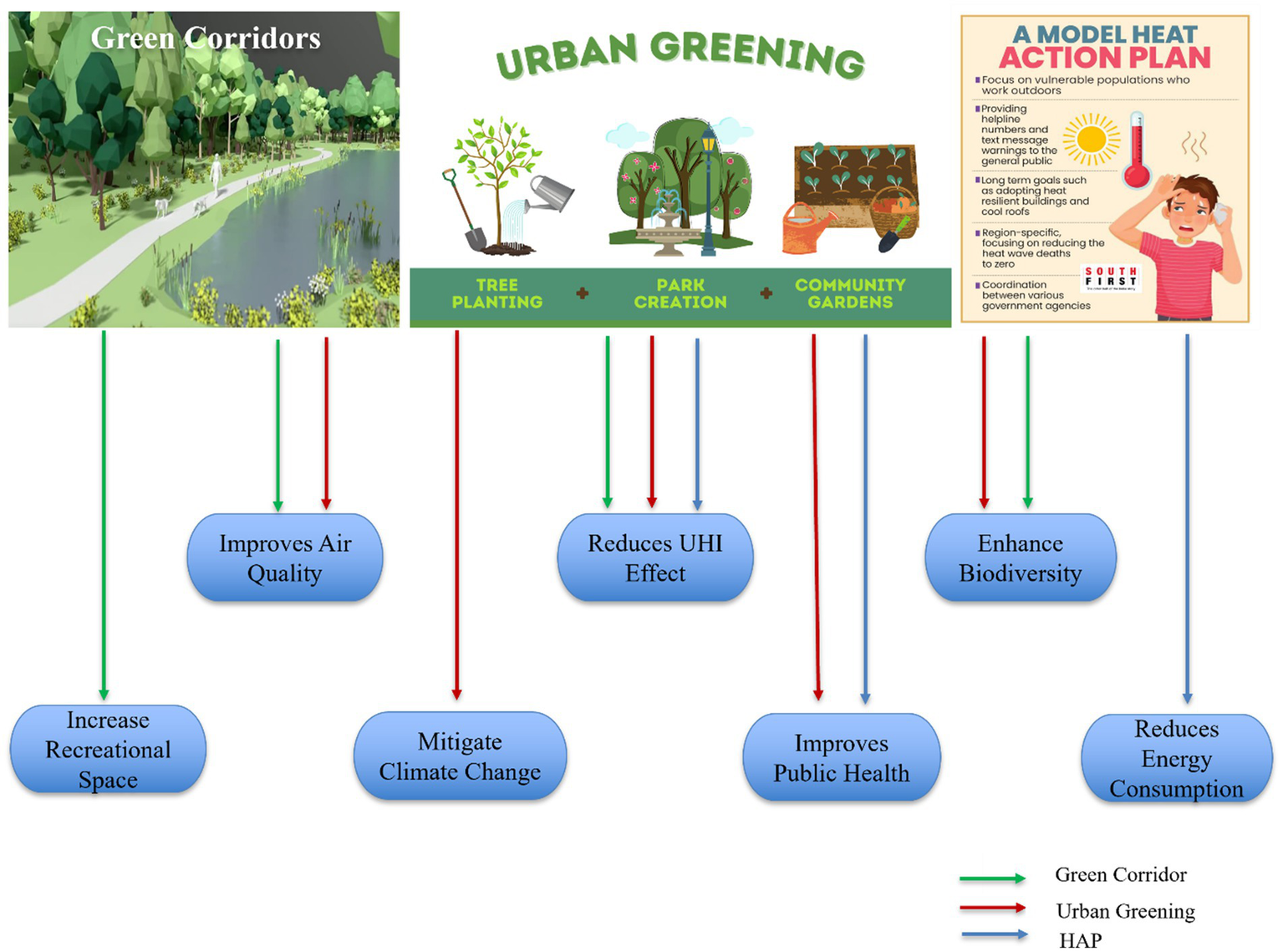

There are several urban greening initiatives taken by Indian government such as National Urban Greening Policies, development of Green Corridors, and Smart Cities Mission with a motive of enhancing green cover of cities, creating sustainable and resilient urban environment that withstand the challenges of urbanization and climate change (Fatima et al., 2018; Ramaiah and Avtar, 2019; Shah et al., 2021; Das et al., 2022; Aman et al., 2022). These initiatives prove that coordinated community participation and innovative solutions can help in addressing the challenges posed by UHI effect.

Other than this the most effective way is UHI simulation as it helps determine the effect of urbanization on local climate and plan designed targeted mitigation strategies.

Non-environmental measures focus on reducing electricity usage to decrease energy consumption through energy-efficient building designs, promoting economical and fuel-efficient transportation modes, encouraging the use of public transport, and implementing urban planning policies that prioritize non-motorized transport and create more pleasant and healthier urban spaces (Rajagopal et al., 2023). Innovative technologies include reflective and radiative cooling paints, smart materials, building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) and thermochromic smart windows (Aburas et al., 2019; Cheela et al., 2021; Elhabodi et al., 2023). Radiative cooling paints keep the surface cooler by reflecting more sunlight and radiating absorbed heat back into the atmosphere. Thus, it decreases the need of air conditioning as it helps in lowering down the indoor temperature (Chen and Lu, 2020; Khare et al., 2021; Cheela et al., 2021). For instance, roof whitening has been shown to reduce energy needs by 8.8%, with a research study indicating a 49% reduction in heat flow from the roof to underlying spaces in different climatic zones of India, such as hot, dry, humid, and warm zones (Arumugam et al., 2015; Rawat and Singh, 2022).

Smart materials such as thermochromic material changes its color according to the temperature which in turn reduces energy required for heating or cooling purpose (Aburas et al., 2019; Santamouris and Yun, 2020; Zhang et al., 2022a, 2022b). For Kolkata metropolitan region, thermochromic materials had been an excellent heat mitigation technology (Khan et al., 2022). Similar results were obtained in the study conducted for different climatic zones which documented for the energy saving of 15 to 35% varying for hot-dry to tropical climatic conditions (Rawat and Singh, 2022).

BIPVs are solar panels integrated into windows, facades and roofs which reduces the dependency of external non-renewable energy source of power generation; by generating on site energy generation (Skandalos et al., 2022; Elhabodi et al., 2023). According to the literature available, BIPVs installation experiments has been conducted in India for both moderate and cold climatic regions—Bangalore, and Srinagar respectively, to test the energy consumption differences between the conventional and BIPVs installed system (Agrawal and Tiwari, 2011). Similar studies have been conducted in different climatic zones of India such as Mount Abu, Jodhpur, Mumbai, New Delhi, Kolkata, and Bhopal (Ranjan et al., 2008; Rai et al., 2021). The Indian government has recognized the PV solar energy capabilities as the future energy security of India and thus targeted the goal 100 GW till 2022 which is progressing significantly to reach its target in the coming years (Hairat and Ghosh, 2017).

Though these mitigation techniques have quantifiable advantages; there are several obstacles to their practical deployment. In addition to reducing the UHI impact, the majority of environmental and non-environmental interventions also reduce energy consumption, air and water pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions (Akbari, 2011; Santamouris, 2014; Aram et al., 2019; Lai et al., 2019). Besides offering thermal insulation in both summer and winter, they help prolong the roof’s lifespan by shielding it from inclement weather, UV rays, and temperature drops (Khare et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021). Due to their high maintenance and life cycle costs, all these advantages have drawbacks (Akbari and Matthews, 2012; Seifhashemi et al., 2018). Another difficulty is choosing a roof type based on the climatic zones (Khare et al., 2021).

Heat action plan included both environmental and non-environmental measures to combat the UHI effect and mitigating the health impact of extreme heat, implemented in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. It was South Asia’s first Heat Action Plan (Nastar, 2020). This plan helped in improving urban resilience to heat waves and reducing heat related mortality (Hess et al., 2018; Golechha et al., 2021). As cities grapple with issues like UHI effect, air pollution and rapid urbanization, the initiatives like urban greening and green corridors comes into picture to create more sustainable and liveable areas. Tree plantation drives, green roofs and walls, urban parks and gardens, urban farming are a part of urban greening measures taken by the Indian Government (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Benefits of green corridors, urban greening, and heat action plan (HAP) in combating UHI.

Increasing infrastructure in cities demands sustainable building designs. To ensure the design sustainability, assessments like Green Rating for Integrated Habitat Assessment (GRIHA) and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) have come into operation. These are national rating systems for green buildings developed by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) and U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) respectively. These are adopted by different bodies in India, Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) and Indian Green Building Council (IGBC) correspondingly (Arya and Sharma, 2022). Both target on the factors like energy conservation, waste reduction, health and well-being, and environmental protection (Bahale and Schuetze, 2023); hence, encouraging innovative sustainable practices and technology. Key features and common benefits of GRIHA and LEED certification system is depicted (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Key features and common benefits of GRIHA and LEED certification system.

India’s efforts to reduce UHI are still in the nascent state (Sharma et al., 2021). Government is providing rebates and incentives under GRIHA, LEED, IGBC rated green buildings (USGBC, 2014; TERI, 2020; Arya and Sharma, 2022; Kadiwal, 2025). Government initiatives have successfully raised awareness and started significant legal and infrastructure improvements, but institutional, financial, and technological constraints still prevent them from reaching their full potential (Khare et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021). More integrated policies, funding sources, capacity training, and scaled initiatives that correspond with regional contexts are needed to address these constraints (Seifhashemi et al., 2018; Kadiwal, 2025).

In conclusion, to properly address the issue of UHI, both environmental and non-environmental measures must be put into place. These can significantly reduce the urban temperature and improve overall urban climate resilience. As described above, the implementation of environmental initiatives underscores the importance of a multifaceted approach to urban planning and energy management in combating the UHI effect and fostering sustainable urban development. Heat Action Plan (HAP), urban greening and green corridors benefit the environment by decreasing greenhouse gas emissions and the urban carbon footprint.

The systematic review on UHIs (UHIs) in this manuscript offers a comprehensive examination of the factors driving UHI formation, the wide-ranging impacts, and potential mitigation strategies. The main causes are identified as anthropogenic factors, including impervious surfaces, densely populated areas, and decreased vegetation cover. In addition to raising local temperatures, these factors also increase energy use, air pollution, and health hazards, which disproportionately impact vulnerable groups.

A critical review of this manuscript reveals UHI in various geographic areas of the world; however, it falls short in evaluating the socio-economic aspects of UHI impacts, especially in low-income urban areas with limited adaptation capacity. Furthermore, a lot of mitigation techniques-like cool pavements, urban forestry, and green roofs—are discussed in the manuscript. Still, it requires a careful assessment of their long-term feasibility or cost-effectiveness in light of climate change.

The review correctly highlights the necessity of integrated urban planning, to ensure functions for social equity and economic viability along with environmental protection to create sustainable, resilient, and inclusive cities; but it frequently addresses individual solutions rather than advocating for cross-sectoral policies that integrate social justice and climate resilience.

In addition to taking local cultural, economic, and environmental contexts into consideration, future research should place a high priority on participatory approaches that involve communities in the co-development of adaptive solutions.

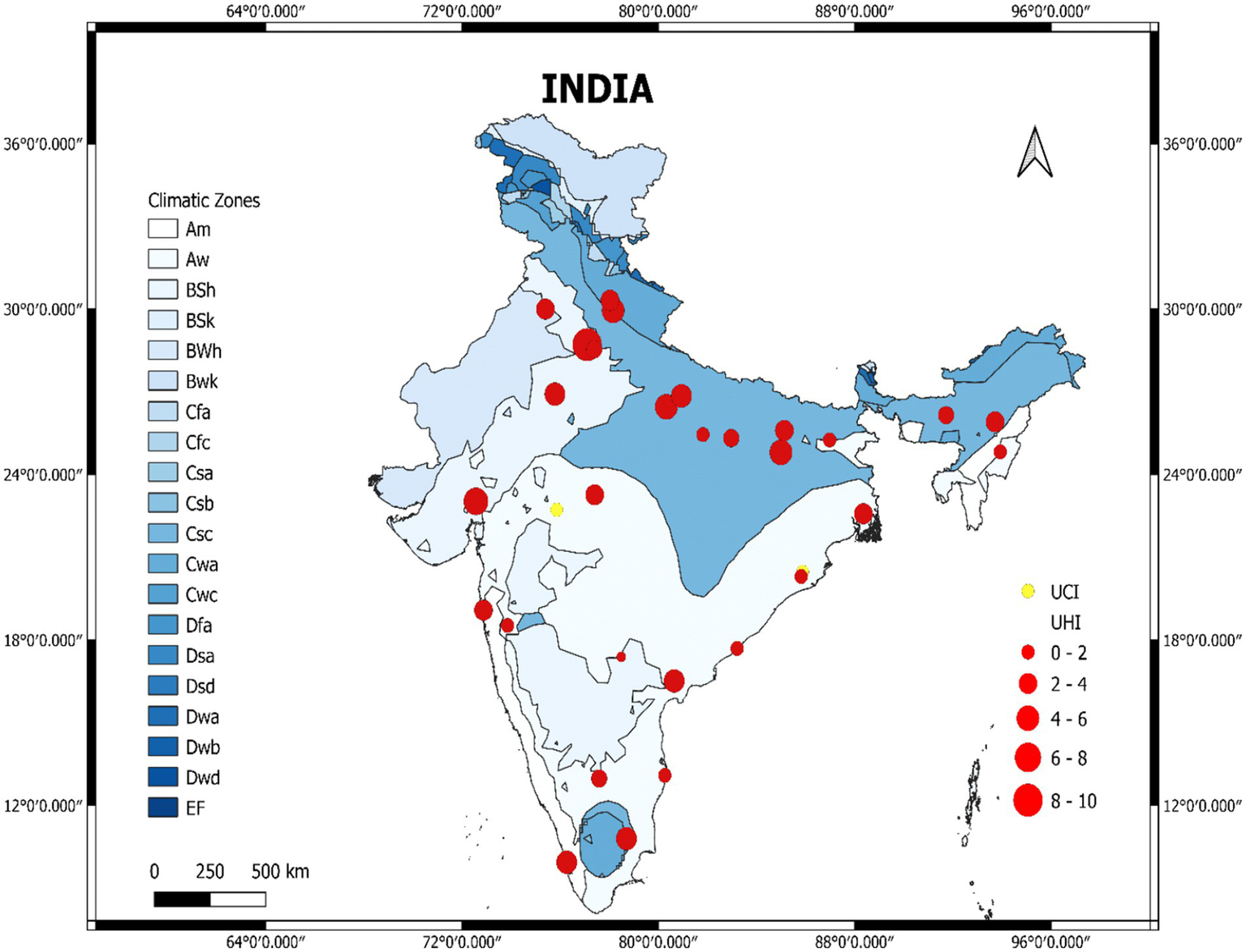

This map (Figure 8) illustrates the UHI Intensity (UHII) across India based on the Köppen climate classification. The climate zones that are being taken into account are Tropical (Am, Aw), Arid (BSh, BSk, BWh, Bwk), Temperate (Cfa, Cfc, Csa, Csb, Csc, Cwa, Cwc), Cold (Dfa, Dsa, Dsd, Dwa, Dwb, Dwd), Polar (EF). Red circles indicate that the UHI is positive, but yellow circles indicate that Urban Cool Island has been reported at the location. The size of circles indicates the magnitude of UHII ranging from 0 to 10 °C. BSh (Arid Climate) experienced the highest UHII with magnitude of 8–10 followed by Csc (Temperate Climate) having magnitude of 4–6; however, in the north eastern region, low UHII magnitude reported ranging from 0 to 2. Unexpectedly, two cities (Indore and Cuttack) of tropical climate reported UCI. This figure was created using QGIS software.

Figure 8

UHI intensity (UHII) map of India.

A compilation of the review carried out in the present study has been tabulated in Supplementary Table S2.

5 Conclusions and limitations

In the present study, the extant literature on the UHI phenomenon in over 40 Indian cities spanning from 2005 to 2023 was systematically reviewed, with an emphasis on the methodologies employed, the specific variables and indices investigated. It also focussed on the spatio-temporal factors that contribute to the UHI effect. This study endeavours to compile the existing body of knowledge on the UHI effect, providing a comprehensive guide for researchers to gain an overview of the UHI phenomenon in India and its dynamics. The study analysed that the primary drivers of increased urban temperatures are unplanned urban agglomeration, decreased vegetation cover, elevated energy consumption, anthropogenic heat emissions, and extensive built-up areas. This review also elucidates the connection between the UHI effect and its consequent impacts on heat-related illnesses and deteriorating air quality. The present study revealed that satellite data are extensively used due to better spatial and temporal resolution; and have advantages over ground-based studies in terms of time and human efforts. Consequently, it is recommended to incorporate satellite data analysis along with field observations for better decision making. Field observations offer ground-truth data that can validate and supplement the insights derived from satellite pictures, addressing potential limitations such as resolution restrictions and temporal breaches. This suggestion is made to increase the accuracy and comprehensiveness of UHI investigations. The role of simulation models in UHI has also been studied to underscore their importance. This study also reviewed both environmental and non-environmental measures implemented to mitigate the UHI effect for a holistic understanding of the approaches that can be employed to reduce urban heat. It is necessary to evaluate these measures for developing integrated and sustainable solutions that address the multifaceted nature of the UHI phenomenon. The study delineates the scope of future research, as outlined in the following points:

-

Since the majority of studies concentrate on Surface UHI (SUHI), there remains substantial scope for further exploration into Atmospheric UHI (AUHI) and Canopy Layer UHI (CLUHI) phenomena.

-

As most of the studies are focused around larger cities, keeping in mind the ever-increasing urban agglomeration and climate sensitivity; understudied Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities provide future scope of UHI study. UHI estimation of smaller but fast-growing cities is necessary to have a smart and sustainable infrastructure.

-

In order to enhance the resilience of cities; it is quintessential to comprehend factors such as topography, urban morphology, urban density, and building arrangements. These provide insights into the unique characteristics and vulnerabilities of each region, paving the way for targeted developmental strategies to mitigate UHI effects and promote sustainable urban planning.

-

Integrating large-area, rapid-assessment strength of satellites, precision of field data and predictive power of simulation models can support both immediate and long-term resilience and sustainability of the Indian cities as satellite studies provide broad spatial coverage and long-term trends. However, the gap regarding atmospheric and surface characteristics of the cities can be overcome by ground-based observations. The validated and calibrated data can be used to train simulation models and hence, be utilitarian in future projections.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PrP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. PuP: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. PrP acknowledges UGC Junior Research Fellowship provided by University Grants Commission (UGC) with UGC Reference ID: 210510697735 for pursuing her research work.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to University of Allahabad, Prayagraj and Central University of Punjab, Bathinda for providing the necessary facilities to carry out the present review.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used LUCID CHART tool in order to prepare the figures used in the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1649138/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aburas M. Soebarto V. Williamson T. Liang R. Ebendorff-Heidepriem H. Wu Y. (2019). Thermochromic smart window technologies for building application: a review. Appl. Energy255:113522. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113522

2

Ach-chakhar M. El Bat M. S. Guernouti S. Romani Z. Draoui A (2025) Impact of heatwaves on energy performance and thermal comfort in urban buildings: integrated approach with microclimatic modeling. Available online at: SSRN 5169362.

3

Adilkhanova I. Ngarambe J. Yun G. Y. (2022). Recent advances in black box and white-box models for UHI prediction: implications of fusing the two methods. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.165:112520. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112520

4

Agrawal B. Tiwari G. N. (2011). An energy and exergy analysis of building integrated photovoltaic thermal systems. Energy Sources Part A33, 649–664. doi: 10.1080/15567030903226280

5

Aijaz R. (2016). Challenge of making smart cities in India. Asie. Visions87, 5–9. Available online at: https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/migrated_files/documents/atoms/files/av87_smart_cities_india_aijaz_4.pdf

6

Akbari H. (2011). Using cool roofs to reduce energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and urban heat-island effects: Findings from an India experiment.

7

Akbari H. Kolokotsa D. (2016). Three decades of UHIs and mitigation technologies research. Energ. Buildings133, 834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.09.067

8

Akbari H. Matthews H. D. (2012). Global cooling updates: reflective roofs and pavements. Energ. Buildings55, 2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.02.055

9

Aman A. Rafiq M. Dastane O. Sabir A. A. (2022). Green corridor: a critical perspective and development of research agenda. Front. Environ. Sci.10:982473. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.982473

10

Amirtham L. R. (2016). Urbanization and its impact on UHI intensity in Chennai metropolitan area, India. Indian J. Sci. Technol.9, 1–8. doi: 10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i5/87201

11

Aram F. García E. H. Solgi E. Mansournia S. (2019). Urban green space cooling effect in cities. Heliyon5, 1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01339,

12

Arumugam R. S. Garg V. Ram V. V. Bhatia A. (2015). Optimizing roof insulation for roofs with high albedo coating and radiant barriers in India. J. Build. Eng., 2, 52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2015.04.004

13

Arya A. Sharma R. L. (2022). Strategies for green building rating in India: a comparison of LEED and GRIHA criteria. Mater Today Proc57, 2311–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2022.01.100

14

Ashtiani A. Mirzaei P. A. Haghighat F. (2014). Indoor thermal condition in UHI: comparison of the artificial neural network and regression methods prediction. Energ. Buildings76, 597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.03.018

15

Aslam M. Y. Krishna K. R. Beig G. Tinmaker M. I. R. Chate D. M. (2017). Seasonal variation of UHI and its impact on air-quality using SAFAR observations at Delhi, India. Am. J. Clim. Change6, 294–305. doi: 10.4236/ajcc.2017.62015

16

Assaf G. Assaad R. H. (2023). Using data-driven feature engineering algorithms to determine the Most critical factors contributing to the urban Heat Island effect associated with global warming. Comput. Civil Eng.1055–1062.

17

Azevedo J. A. Chapman L. Muller C. L. (2016). Quantifying the daytime and night-time UHI in Birmingham, UK: a comparison of satellite derived land surface temperature and high resolution air temperature observations. Remote Sens8:153. doi: 10.3390/rs8020153

18

Baby M. M. Arya G. (2016). A study of UHI and its mapping. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res.4, 45–47. doi: 10.70729/IJSER15706

19

Badarinath K. V. S. Chand T. R. K. Madhavilatha K. Raghavaswamy V. (2005). Studies on UHIs using Envisat AATSR data. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens.33, 495–501. doi: 10.1007/BF02990734

20

Badugu A. Arunab K. Mathew A. Sarwesh P. (2023). Spatial and temporal analysis of UHI effect over Tiruchirappalli city using geospatial techniques. Geod. Geodyn.14, 275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.geog.2022.10.004

21

Bahale S. Schuetze T. (2023). Comparative analysis of neighborhood sustainability assessment systems from the USA (LEED–ND), Germany (DGNB–UD), and India (GRIHA–LD). Land12:1002. doi: 10.3390/land12051002

22

Bai X. McPhearson T. Cleugh H. Nagendra H. Tong X. Zhu T. et al . (2017). Linking urbanization and the environment: conceptual and empirical advances. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour.42, 215–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-061128

23

Balany F. Ng A. W. Muttil N. Muthukumaran S. Wong M. S. (2020). Green infrastructure as an urban heat island mitigation strategy—a review. Water, 12:3577.

24

Barat A. Kumar S. Kumar P. Parth Sarthi P. (2018). Characteristics of surface UHI (SUHI) over the Gangetic plain of Bihar, India. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci.54, 205–214. doi: 10.1007/s13143-018-0004-4

25

Barat A. Parth Sarthi P. Kumar S. Kumar P. Sinha A. K. (2021). Surface UHI (SUHI) over riverside cities along the Gangetic plain of India. Pure Appl. Geophys.178, 1477–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00024-021-02701-6

26

Basara J. B. Basara H. G. Illston B. G. Crawford K. C. (2010). The impact of the UHI during an intense heat wave in Oklahoma City. Adv. Meteorol.2010:230365. doi: 10.1155/2010/230365

27

Bhatta B. (2011). Remote sensing and GIS(2nd ed.).Oxford University Press (India).

28

Bhattacharjee A. Kamble S. Kamal N. Golhar P. Kumari V. Bhargava A. (2022). UHI effect: a case study of Jaipur, India. Int. J. Earth Sci. Knowl. Appl.4, 133–139. doi: 10.1007/9

29

Bhowmick D. Mukherjee K. Dash P. Mondal R. (2023). Use of “local climate zones” for detecting UHI: a case study of Kolkata metropolitan area, India. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci.1164:012007. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1164/1/012007

30

Borbora J. Das A. K. (2014). Summertime UHI study for Guwahati City, India. Sustain. Cities Soc.11, 61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2013.12.001

31

Borthakur M. Nath B. K. (2012). A study of changing urban landscape and heat island phenomenon in Guwahati metropolitan area. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ.2, 1–6. Available online at: https://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-1112/ijsrp-p1127.pdf

32

Boyaj A. Karrevula N. R. Sinha P. Patel P. Mohanty U. C. Niyogi D. (2024). Impact of increasing urbanization on heatwaves in Indian cities. Int. J. Climatol.44, 4089–4114. doi: 10.1002/joc.8570

33

Bradford K. Abrahams L. Hegglin M. Klima K. (2015). A heat vulnerability index and adaptation solutions for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Environ. Sci. Technol.49, 11303–11311. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03127,

34

Budhiraja B. Agrawal G. Pathak P. (2020). UHI effect of a polynuclear megacity Delhi–compactness and thermal evaluation of four sub-cities. Urban Clim.32:100634. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100634

35

Bueno B. Norford L. Hidalgo J. Pigeon G. (2013). The urban weather generator. J. Build. Perform. Simul.6, 269–281. doi: 10.1080/19401493.2012.718797

36

Cao Q. Luan Q. Liu Y. Wang R. (2021). The effects of 2D and 3D building morphology on urban environments: a multi-scale analysis in the Beijing metropolitan region. Build. Environ.192:107635. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107635

37

Cellura M. Guarino F. Longo S. Mistretta M. (2017). Modeling the energy and environmental life cycle of buildings: a co-simulation approach. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.80, 733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.273

38

Chandrakar S. Sinha M. K. (2021). “Comparative analysis of NDVI and LST to identify UHI effect using remote sensing and GIS” in Water resource technology: management for engineering applications, eds. DubeyV.MishraS. R. K.Michalska-DomańskaM.DeshpandeV.Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. 9, 99–100.

39

Chatterjee S. Gupta K. (2021). Exploring the spatial pattern of UHI formation in relation to land transformation: a study on a mining industrial region of West Bengal, India. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ.23:100581. doi: 10.1016/j.rsase.2021.100581

40

Cheela V. S. John M. Biswas W. Sarker P. (2021). Combating UHI effect—a review of reflective pavements and tree shading strategies. Buildings11:93. doi: 10.3390/buildings11030093

41

Chen J. Lu L. (2020). Development of radiative cooling and its integration with buildings: a comprehensive review. Sol. Energy212, 125–151. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2020.10.013

42

Choudhury U. Singh S. K. Kumar A. Meraj G. Kumar P. Kanga S. (2023). Assessing land use/land cover changes and UHI intensification: a case study of Kamrup Metropolitan District, Northeast India (2000–2032). Earth4, 503–521. doi: 10.3390/earth4030026

43

Cichowicz R. Bochenek A. D. (2024). Assessing the effects of UHIs and air pollution on human quality of life. Anthropocene46:100433. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2024.100433

44

Collier C. G. (2006). The impact of urban areas on weather. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc.132, 1–25. doi: 10.1256/qj.05.199

45

Cortes A. Rejuso A. J. Santos J. A. Blanco A. (2022). Evaluating mitigation strategies for UHI in Mandaue City using ENVI-met. J. Urban Manag.11, 97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jum.2022.01.002

46

Das M. Das A. Momin S. (2022). Quantifying the cooling effect of urban green space: a case from urban parks in a tropical mega metropolitan area (India). Sustain. Cities Soc.87:104062. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2022.104062

47

Das A. Saha P. Dasgupta R. Inacio M. Das M. Pereira P. (2024). How do the dynamics of urbanization affect the thermal environment? A case from an urban agglomeration in lower Gangetic plain (India). Sustainability16:1147. doi: 10.3390/su16031147

48

Debnath K. B. Jenkins D. Patidar S. Peacock A. D. Bridgens B. (2023). Climate change, extreme heat, and south Asian megacities: impact of heat stress on inhabitants and their productivity. ASME J. Eng. Sustain. Build. Cities4. doi: 10.1115/1.4064021

49

Deilami K. Kamruzzaman M. Liu Y. (2018). UHI effect: a systematic review of spatio-temporal factors, data, methods, and mitigation measures. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf.67, 30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jag.2017.12.009

50

Devadas M. D. Rose A. L. (2009). Urban factors and the intensity of heat island in the city of Chennai. In Seventh International Conference on Urban Climate (Vol. 29).

51

Devi S. S. (2006). UHIs and environmental impact. In 86th American Meteorological Society Annual Meeting, Atlanta, Georgia.

52

Ding W. Chen H. (2024). Investigating the microclimate impacts of blue–green space development in the urban–rural fringe using the WRF-UCM model. Urban Clim.54:101865. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2024.101865

53

Ding L. Xiao X. Wang H. (2025). Temporal and spatial variations of urban surface temperature and correlation study of influencing factors. Sci. Rep.15:914. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-85146-4,

54

Dissegna M. A. Yin T. Wu H. Lauret N. Wei S. Gastellu-Etchegorry J. P. et al . (2021). Modeling mean radiant temperature distribution in urban landscapes using DART. Remote Sens13:1443. doi: 10.3390/rs13081443

55

Dutta I. Das A. (2020). Exploring the spatio-temporal pattern of regional heat island (RHI) in an urban agglomeration of secondary cities in eastern India. Urban Clim.34:100679. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100679

56

Elhabodi T. S. Yang S. Parker J. Khattak S. He B. J. Attia S. (2023). A review on BIPV-induced temperature effects on UHIs. Urban Clim.50:101592. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101592

57

Fatima S. Kunkulol R. Gangadhar A. H. Megha S. Kunwar V. Deepak P. R. et al . (2018). Awareness about the concept of green corridor among medical student and doctors in a rural medical College of Maharashtra, India. Int. J. Clin. Biomed. Res., 38–43. doi: 10.31878/ijcbr.2018.43.09

58

Feng J. M. Wang Y. L. Ma Z. G. Liu Y. H. (2012). Simulating the regional impacts of urbanization and anthropogenic heat release on climate across China. J. Clim.25, 7187–7203. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00333.1

59

Gastellu-Etchegorry J. P. (2008). 3D modeling of satellite spectral images, radiation budget and energy budget of urban landscapes. Meteorog. Atmos. Phys.102, 187–207. doi: 10.1007/s00703-008-0344-1

60

Gautam R. Singh M. K. (2018). UHI over Delhi punches holes in widespread fog in the Indo-Gangetic Plains. Geophys. Res. Lett.45, 1114–1121. doi: 10.1002/2017GL076794

61

Ghosh R. Kansal A. (2014) Urban challenges in India and the mission for a sustainable habitat. Interdisciplina. 2, 281–304. doi: 10.22201/ccich.24485705e.2014.2.46530

62

Gohain K. J. Goswami A. Mohammad P. Kumar S. (2023). Modelling relationship between land use land cover changes, land surface temperature and UHI in Indore city of Central India. Theor. Appl. Climatol.151, 1981–2000. doi: 10.1007/s00704-023-04371-x

63

Golechha M. Mavalankar D. Bhan S. C. (2021). “India: Heat wave and action plan implementation in Indian cities” in Urban climate science for planning healthy cities, eds. RenC.McGregorG.Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 285–308. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-87598-5_13

64

Goswami A. Mohammad P. Sattar A. (2016). A temporal study of UHI —A evaluation of Ahmedabad city, Gujarat. In International Conference on Climate Change Mitigation and Technologies for Adaptation (pp. 1–5).

65

Grover A. Singh R. B. (2015). Analysis of UHI in relation to normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI): a comparative study of Delhi and Mumbai. Environments2, 125–138. doi: 10.3390/environments2020125

66

Gupta N. Aithal B. H. (2024). Urban land surface temperature forecasting: a data-driven approach using regression and neural network models. Geocarto Int.39:2299145. doi: 10.1080/10106049.2023.2299145

67

Hairat M. K. Ghosh S. (2017). 100 GW solar power in India by 2022–a critical review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.73, 1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.02.012

68

Halder B. Bandyopadhyay J. Banik P. (2021). Monitoring the effect of urban development on UHI based on remote sensing and geo-spatial approach in Kolkata and adjacent areas, India. Sustain. Cities Soc.74:103186. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.103186

69

Halder B. Bandyopadhyay J. Khedher K. M. Fai C. M. Tangang F. Yaseen Z. M. (2022). Delineation of urban expansion influences UHIs and natural environment using remote sensing and GIS-based in industrial area. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.29, 73147–73170. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-20821-x,

70

Hassan T. Zhang J. Prodhan F. A. Pangali Sharma T. P. Bashir B. (2021). Surface UHIs dynamics in response to LULC and vegetation across South Asia (2000–2019). Remote Sens13:3177. doi: 10.3390/rs13163177

71

He B. J. (2018). Potentials of meteorological characteristics and synoptic conditions to mitigate UHI effects. Urban Clim.24, 26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2018.01.004

72

He X. Wang J. Feng J. Yan Z. Miao S. Zhang Y. et al . (2020). Observational and modeling study of interactions between UHI and heatwave in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod.247:119169. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119169

73

Heaviside C. Macintyre H. Vardoulakis S. (2017). The urban heat island: implications for health in a changing environment. Current Environ. Health Reports, 4, 296–305. doi: 10.1007/s40572-017-0150-3

74

Heisler G. M. Brazel A. J. (2010). The urban physical environment: temperature and UHIs. Urban Ecosyst. Ecol.55, 29–56. doi: 10.2134/agronmonogr55.c2

75

Heisler G. M. Brazel A. J. (2015). The urban physical environment: temperature and UHIs. Agron. Monogr., 29–56. doi: 10.2134/agronmonogr55.c2

76

Hess J. J. Lm S. Knowlton K. Saha S. Dutta P. Ganguly P. et al . (2018). Building resilience to climate change: pilot evaluation of the impact of India’s first heat action plan on all-cause mortality. J. Environ. Public Health2018, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2018/7973519,

77

Hoffmann P. Krueger O. Schlünzen K. H. (2012). A statistical model for the UHI and its application to a climate change scenario. Int. J. Climatol.32:1238. doi: 10.1002/joc.2348

78

Hoornweg D. Pope K. (2017). Population predictions for the world’s largest cities in the 21st century. Environ. Urban.29, 195–216. doi: 10.1177/0956247816663557

79

Imam A. U. Banerjee U. K. (2016). Urbanisation and greening of Indian cities: problems, practices, and policies. Ambio45, 442–457. doi: 10.1007/s13280-015-0763-4,

80

Imran H. M. Shammas M. I. Rahman A. Jacobs S. J. Ng A. W. M. Muthukumaran S. (2021). Causes, modeling and mitigation of UHI: a review. Earth Sci.10, 244–264. doi: 10.11648/j.earth.20211006.11

81

IPCC (2021) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (Accessed 24 December, 2023).

82

Irfan M. Musarat M. A. Alaloul W. S. Ghufran M. (2024). “Radiative forcing on climate change: assessing the effect of greenhouse gases on energy balance of earth” in Advances and technology development in greenhouse gases: Emission, capture and conversion (Elsevier), 137–167. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-19066-7.00012-6

83

Islam S. Karipot A. Bhawar R. Sinha P. Kedia S. Khare M. (2024). UHI effect in India: a review of current status, impact and mitigation strategies. Discover Cities1, 1–28. doi: 10.1007/s44327-024-00033-3

84

Jabbar H. K. Hamoodi M. N. Al-Hameedawi A. N. (2023). UHIs: a review of contributing factors, effects and data. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (vol. 1129, no. 1, p. 012038). IOP Publishing.

85

Jagtap A. A. Shedge D. K. Mane P. B. (2024). Exploring the effects of land use/land cover (LULC) modifications and land surface temperature (LST) in Pune, Maharashtra with anticipated LULC for 2030. Int. J. Geoinform.20. doi: 10.52939/ijg.v20i2.3065

86

Jain M. (2023). Two decades of nighttime surface UHI intensity analysis over nine major populated cities of India and implications for heat stress. Front. Sustain. Cities5:1084573. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1084573

87

Jamal S. Saqib M. Ahmad W. S. Ahmad M. Ali M. A. Ali M. B. (2023). Unraveling the complexities of land transformation and its impact on urban sustainability through land surface temperature analysis. Appl. Geomat.15, 719–741. doi: 10.1007/s12518-023-00521-y

88

Jato-Espino D. (2019). Spatiotemporal statistical analysis of the UHI effect in a Mediterranean region. Sustain. Cities Soc.46:101427. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101427

89

Jayasheela A. Tholiya J. J. (2018). Impact of vegetation in mitigating the UHI effect at Vishrantwadi, Pune, India. In Advances in Smart Cities and Machine Learning, Singapore: Springer. 123, 83–95. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-1427-9_12

90

Jeganathan A. Andimuthu R. Prasannavenkatesh R. Kumar D. S. (2014). Spatial variation of temperature and indicative of the UHI in Chennai metropolitan area, India. Theor. Appl. Climatol.123, 83–95. doi: 10.1007/s00704-014-1331-8

91

Jiang S. Wei Z. (2024). Urbanization exacerbated the rapid growth of summer cooling demands in China from 1980 to 2023. Sustain. Cities Soc.106:105382. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2024.105382

92

Joshi K. Kumari M. Mishra V. N. Prasad R. Zhran M. (2025). Geoinformatics based evaluation of heat mitigation strategies through urban green spaces in a rapidly growing city of India: implications for urban resilience. Theor. Appl. Climatol.156, 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s00704-025-05411-4

93

Joshi R. Raval H. Pathak M. Prajapati S. Patel A. Singh V. et al . (2015). UHI characterization and isotherm mapping using geo-informatics technology in Ahmedabad city, Gujarat state, India. Int. J. Geosci.6, 274–285. doi: 10.4236/ijg.2015.63021

94

Joshi M. Y. Teller J. (2024). Assessing UHI mitigation potential of realistic roof greening across local climate zones: a highly-resolved weather research and forecasting model study. Sci. Total Environ.944:173728. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173728

95

Kabisch N. Remahne F. Ilsemann C. Fricke L. (2023). The UHI under extreme heat conditions: a case study of Hannover, Germany. Sci. Rep.13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-49058-5

96

Kadaverugu R. Purohit V. Matli C. Biniwale R. (2021). Improving accuracy in simulation of urban wind flows by dynamic downscaling WRF with OpenFOAM. Urban Clim.38:100912. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100912

97

Kadiwal N. R. (2025) Comparative evaluation of green building standards in India. Stockholm, Sweden: KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

98

Kaur R. Pandey P. (2020). Monitoring and spatio-temporal analysis of UHI effect for Mansa district of Punjab, India. Adv. Environ. Res.9, 19–39. doi: 10.12989/aer.2020.9.1.019

99

Kaur R. Pandey P. (2022). Spatial trends of surface UHI in Bathinda: a semiarid city of northwestern India. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol., 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s13762-021-03742-z

100

Kedia S. Bhakare S. P. Dwivedi A. K. Islam S. Kaginalkar A. (2021). Estimates of change in surface meteorology and UHI over Northwest India: impact of urbanization. Urban Clim.36:100782. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100782

101

Kesavan R. Muthian M. Sudalaimuthu K. Sundarsingh S. Krishnan S. (2021). ARIMA modeling for forecasting land surface temperature and determination of UHI using remote sensing techniques for Chennai city, India. Arab. J. Geosci.14. doi: 10.1007/s12517-021-07351-5

102

Khan R. Aribam B. Alam W. (2023). Estimation of impacts of land use and land cover (LULC) changes on land surface temperature (LST) within greater Imphal urban area using geospatial technique. Acta Geophys.71, 2811–2823. doi: 10.1007/s11600-023-01159-5

103

Khan Z. T. Bera D. (2020). Assessment of UHI in Bilaspur city, Chhattisgarh. J. Glob. Resour.6, 189–197. doi: 10.46587/JGR.2019.v06i01.030

104

Khan A. Carlosena L. Feng J. Khorat S. Khatun R. Doan Q. V. et al . (2022). Optically modulated passive broadband daytime radiative cooling materials can cool cities in summer and heat cities in winter. Sustainability14:1110. doi: 10.3390/su14031110

105

Khan A. Chatterjee S. (2016). Numerical simulation of UHI intensity under urban–suburban surface and reference site in Kolkata, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ.2, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40808-016-0264-x

106

Khan A. Chatterjee S. Wang Y. (2020). Urban Heat Island Modeling for Tropical Climates.. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/C2019-0-04185-8

107

Khare V. R. Vajpai A. Gupta D. (2021). A big picture of urban heat island mitigation strategies and recommendation for India. Urban Climate.37:100845.

108