Abstract

This study aims to clarify the intrinsic relationship among the establishment of FTZs, industrial agglomeration, the digital economy, and green technological innovation. This paper empirically examines the impact of the establishment of FTZs on regional GTI and its mechanisms, based on panel data from 285 cities between 2009 and 2022, using the DID method. The findings show that the establishment of FTZs significantly enhances the level of GTI in the cities where they are located, with the GTI index increasing by an average of 696.501 units. Regional analysis reveals that coastal FTZs have a significantly stronger positive effect on GTI than inland and border FTZs. Furthermore, the promotion of GTI by FTZs intensifies with rising per capita GDP. Mechanism analysis indicates that FTZs promote the development of green industries through industrial agglomeration and the digital economy, thereby further stimulating GTI. Based on these findings, this paper proposes four policy recommendations: (1) strengthen region-specific policies and develop strategies to support GTI tailored to regional characteristics; (2) promote industrial transformation and upgrading, encouraging the green transformation of traditional industries; (3) improve the policy support system and optimize incentives for GTI; (4) enhance the greening of the financial system to increase the marketization and internationalization of green financial products.

1 Introduction

In a critical period when the global economy is experiencing dual transitions of digitalization and green development, green technological innovation (GTI) has become a core driver of national competitiveness and sustainable development. Addressing climate change and achieving low-carbon development is not only a shared responsibility of all countries but also an inevitable trend in global economic restructuring and technological revolution. The Report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China emphasized the need to “innovate mechanisms for developing trade in services, foster digital trade, and accelerate the building of a strong trading nation,” while also making strategic arrangements to advance green development and promote harmony between humanity and nature. Against this backdrop, exploring effective pathways to foster GTI is particularly important for achieving the dual goals of high-quality economic growth and ecological protection.

Since the launch of China’s first Pilot Free Trade Zones (FTZs), these zones have served as new frontiers of reform and opening-up in the new era. Centered on institutional innovation, they have conducted extensive explorations in areas such as trade and investment liberalization, financial openness, and government function transformation, with the aim of generating policy practices that are replicable and scalable (Yao and Whalley, 2016; Guan et al., 2023; Akbari et al., 2019). Existing studies demonstrate that FTZs have played an active role in promoting trade, attracting foreign investment, and serving as important engines of regional economic growth (Bao et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2022; Feng et al., 2023; Bi et al., 2023).

Enhancing green innovation capacity is not only essential for strengthening the competitiveness of FTZs but also a foundation for promoting the green transformation of industries. Under the policy support of FTZs, regional industrial agglomeration has accelerated, leading to enterprise expansion and greater input of production factors, which in turn increases pressures of energy consumption and carbon emissions. Recent studies (Degirmenci et al., 2024; Aydin et al., 2025; Destek et al., 2025) indicate that GTI can reduce carbon emissions by fostering energy-saving and environmentally friendly technologies and clean production processes, and also regulate emissions by improving efficiency and resource utilization, thereby benefiting regions with strong industrial agglomeration. At the same time, Degirmenci et al. (2025) and Chen and Xie (2025) highlight that the digital economy—by optimizing factor allocation, facilitating information flows, and promoting technology diffusion—can reinforce the positive role of industrial agglomeration in advancing green innovation. This enhances regional spillover effects and injects momentum into the high-level openness and industrial upgrading of FTZs.

In this context, it is crucial to clarify the underlying relationships among FTZ development, industrial agglomeration, the digital economy, and GTI. Such an inquiry is highly relevant for identifying new drivers of green innovation and promoting high-quality development within FTZs. Accordingly, several questions arise: Have FTZ policies effectively promoted GTI? What are the underlying mechanisms? And how do industrial agglomeration and the digital economy mediate this relationship? Addressing these questions is of practical significance for optimizing FTZ policy design and better leveraging its role as a driver of green innovation. Using panel data from 285 Chinese cities, this study empirically investigates the impact of FTZs on GTI and explores the mechanisms through industrial agglomeration and the digital economy, aiming to provide empirical evidence and policy insights for green and low-carbon development as well as the high-standard construction of FTZs.

2 Literature review

As strategic platforms for China’s deepened reform and opening-up, FTZs have attracted considerable scholarly attention, particularly regarding their effects and outcomes. Existing studies have primarily focused on the impacts of FTZs on economic growth, international trade, industrial upgrading, and foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, Guan et al. (2023) found that FTZs significantly promoted the structural upgrading of the service sector in host cities by leveraging policy and institutional advantages to attract high-end domestic and foreign resources, thereby accelerating service industry transformation. Shahid et al. (2024) examined the role of FTZs in enhancing regional participation in global value chains and showed how the Shanghai FTZ facilitated industrial upgrading through trade and investment liberalization, innovation-driven initiatives, and the development of integrated service platforms. Similarly, Chen et al. (2022) argued that the establishment of FTZs substantially transformed domestic trade patterns, with general trade increasing by 11.8% and processing trade declining by 14.1%. Using a difference-in-differences (DID) approach, Li et al. (2023) demonstrated that FTZs significantly stimulated regional economic growth, while Cen and Wang (2024) emphasized that trade facilitation and investment liberalization policies improved cities’ foreign trade performance. At the industrial level, Ge et al. (2023) found that FTZ policies fostered structural transformation in both manufacturing and services, strengthening agglomeration effects in high value-added industries.

More recently, with GTI becoming a core element of China’s national strategy, scholars have begun to examine the role of FTZs in promoting green development and low-carbon transition. Ling et al. (2024) reported that FTZs significantly improved urban green total factor productivity (GTFP), with an average increase of 9.5% after their establishment. Using firm-level data, Wang et al. (2023) and Pan and Cao (2024) provided evidence that FTZs substantially enhanced GTI; between 2010 and 2021, cities hosting FTZs accounted for 63.92% of China’s low-carbon patent applications. Fan et al. (2022) and Lin et al. (2024) analyzed FTZs in the Yangtze River Delta and found that port environmental efficiency, measured by the GML index, exhibited an overall upward trajectory with cyclical fluctuations. Xu et al. (2024) and Xu et al. (2024) showed that FTZs encouraged firms’ environmental technological innovation by introducing high environmental standards and green trade rules. Jiang et al. (2021) and He and Ma (2025) further highlighted that financial liberalization within FTZs facilitated green financing, thereby supporting R&D in green technologies. In addition, other scholars have stressed the digital dimension of FTZs. Sun et al. (2025) and Lei et al. (2024) argued that FTZs act as “pressure-testing zones” for cross-border data flows, providing institutional safeguards for digital industrial innovation and green digital transformation.

However, little research has integrated FTZs, industrial agglomeration, the digital economy, and GTI into a unified analytical framework. First, although much of the literature has examined the economic and trade effects of FTZs, few studies have systematically investigated their direct impacts on GTI and its underlying mechanisms. Second, while industrial agglomeration is widely recognized as a key feature of FTZs, its role in GTI remains unclear, and empirical evidence at the city level is limited. Third, although the digital economy is a focal area of FTZ development, existing discussions are mostly conceptual, with limited empirical support regarding its interaction with GTI.

This paper makes three main contributions. First, it develops an analytical framework that incorporates both industrial agglomeration and the digital economy to examine the mechanisms through which FTZs affect GTI. Second, it employs macro-level data from 285 Chinese cities and applies a multi-period DID approach to identify the net effects of FTZ policies, thereby improving the robustness of the findings. Third, it conducts heterogeneity analyses from the perspectives of locational characteristics and economic development levels, providing practical implications for designing differentiated policies to foster GTI in FTZs.

3 Model construction

3.1 Theoretical hypotheses

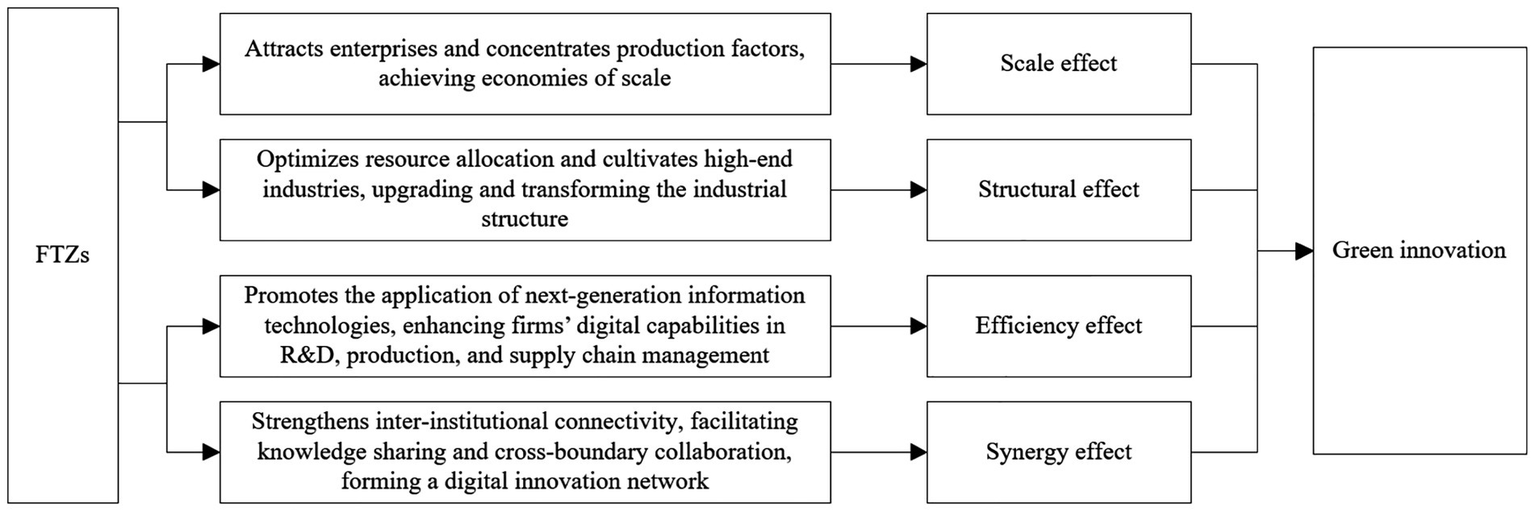

As frontier platforms for institutional innovation, FTZs can promote GTI through industrial agglomeration and the digital economy. The logical framework of this mechanism is illustrated in Figure 1.

-

Agglomeration Mechanism. According to Marshall’s theory of externalities, industrial agglomeration can enhance innovation through three main channels: a shared labor market, the availability of specialized intermediate inputs, and knowledge spillover effects (David and Rosenbloom, 1990; Beenstock and Felsenstein, 2010). In the field of green technologies, agglomeration facilitates access to specialized talents and resources for green R&D, strengthening interfirm collaboration and knowledge diffusion. This reduces R&D costs and accelerates the dissemination of innovations. Furthermore, new economic geography suggests that agglomeration can expand market demand and application scenarios for green technologies through economies of scale and spatial spillovers, thereby accelerating their marketization and industrialization. FTZs can thus create favorable institutional and industrial environments for GTI by fostering industrial agglomeration.

-

Digital Economy Mechanism. Drawing on the theory of digital empowerment, digital technologies can significantly promote GTI by reducing R&D costs, optimizing resource allocation, and enhancing interfirm connectivity (Carlsson, 2004; Bukht and Heeks, 2017; Javaid et al., 2024). Big data and artificial intelligence reduce uncertainties and trial-and-error costs in green technology R&D, improving efficiency. Platform-based business models, such as green supply chain management systems and smart energy platforms, further optimize resource allocation and facilitate the application and diffusion of green technologies. Additionally, the digital economy enables the intelligent transformation of green industries, enhancing the sustainability and capacity for iterative innovation of GTI.

-

Regional Heterogeneity Mechanism. However, the magnitude of these effects may vary across regions. Coastal FTZs, benefiting from favorable geographic locations, higher openness, and strong industrial bases, are more likely to attract multinational R&D centers and high-end talent, forming internationalized green technology clusters. The effects of industrial agglomeration and the digital economy are therefore more pronounced. In contrast, inland and border FTZs face constraints in infrastructure, factor mobility, and market size, resulting in relatively weaker agglomeration and digital empowerment effects. These differences help explain the heterogeneous impact of FTZs on GTI across regions.

Figure 1

Mechanism through which FTZs promote GTI via industrial agglomeration and the digital economy.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H1: FTZs promote the development of GTI in host cities.

H2: FTZs enhance local GTI through industrial agglomeration.

H3: FTZs foster local GTI by advancing the digital economy.

3.2 The basic model

This paper uses the implementation of FTZs policies as a quasi-natural experiment and employs the DID method to examine the effect of FTZs establishment on green finance. A treatment group consisting of 47 cities with established FTZs is selected, while cities without FTZs serve as the control group. The following DID model is constructed.

Wher is the dependent variable, which is constructed to examine the effect of FTZs on the development of green finance in the region. The subscripts i and t represent the i province and the t year, respectively. represents the model’s control variables. is the estimated coefficient of the variable. denotes the cross-sectional fixed effect, indicates the time fixed effect, and is the random error term.

3.3 Variable description

-

1 Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study is GTI. Data on GTI are obtained from the patent database of the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). Following the Guidelines for Green Patent Classification (CNIPA, 2012), we identify green patents in environmental protection, energy-saving, and new energy technologies. Specifically, we focus on the number of granted green invention patents, excluding utility models and design patents. Compared with alternative indicators such as green technology investment or R&D expenditure, the number of green invention patents is more intuitive, quantifiable, and better captures the originality and breakthrough nature of innovations. Tracking this indicator allows us to effectively evaluate the actual impact of FTZ policies on GTI.

-

2 Core explanatory variable

The core explanatory variable is FTZs, defined as a dummy variable. If city i officially established an FTZ in year t, the FTZ variable takes the value 1 from year t onward; otherwise, it is 0. Prior to 2022, the State Council had approved 21 FTZ pilot zones nationwide. The treatment group in this study consists of 47 cities hosting pilot zones within these 21 FTZs (see Table 1). China had a total of 293 prefecture-level cities by 2022. However, due to missing data for some cities (e.g., Shigatse and Chamdo), the final sample comprises 285 cities, with the remaining 238 cities without FTZs serving as the control group.

-

3 Control variables: technological level and industrial structure

Table 1

| No. | Province | City | Year established |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shanghai | Shanghai | 2013 |

| 2 | Tianjin | Tianjin | 2015 |

| 3 | Fujian | Fuzhou | 2015 |

| Xiamen | 2015 | ||

| 4 | Guangdong | Guangzhou | 2015 |

| Shenzhen | 2015 | ||

| Zhuhai | 2015 | ||

| 5 | Liaoning | Shenyang | 2017 |

| Dalian | 2017 | ||

| Yingkou | 2017 | ||

| 6 | Zhejiang | Zhoushan | 2017 |

| Hangzhou | 2020 | ||

| Ningbo | 2020 | ||

| Jinhua | 2020 | ||

| 7 | Hubei | Wuhan | 2017 |

| Yichang | 2017 | ||

| Xiangyang | 2017 | ||

| 8 | Henan | Zhengzhou | 2017 |

| Luoyang | 2017 | ||

| Kaifeng | 2017 | ||

| 9 | Chongqing | Chongqing | 2017 |

| 10 | Sichuan | Chengdu | 2017 |

| Luzhou | 2017 | ||

| 11 | Shaanxi | Xi’an | 2017 |

| 12 | Hainan | Sanya | 2018 |

| Haikou | 2018 | ||

| 13 | Shandong | Jinan | 2019 |

| Qingdao | 2019 | ||

| Yantai | 2019 | ||

| 14 | Jiangsu | Nanjing | 2019 |

| Suzhou | 2019 | ||

| Lianyungang | 2019 | ||

| 15 | Guangxi | Nanning | 2019 |

| Qinzhou | 2019 | ||

| Chongzuo | 2019 | ||

| 16 | Hebei | Shijiazhuang | 2019 |

| Tangshan | 2019 | ||

| 17 | Beijing | Beijing | 2019 |

| 18 | Yunnan | Kunming | 2019 |

| 19 | Heilongjiang | Harbin | 2019 |

| Heihe | 2019 | ||

| 20 | Hunan | Changsha | 2020 |

| Yueyang | 2020 | ||

| Chenzhou | 2020 | ||

| 21 | Anhui | Hefei | 2020 |

| Wuhu | 2020 | ||

| Bengbu | 2020 |

Cities with FTZs and their year of establishment.

This study selects the following control variables: ① Economic development level (Ecde), represented by the logarithm of per capita GDP; ② Degree of informatization (Deif), measured by the proportion of postal and telecommunications income in GDP; ③ Level of financial development (Lefe), represented by the proportion of total deposits and loans of financial institutions in the region to GDP; ④ Government intervention (Goin), measured by the proportion of the general government budget to GDP.

3.4 Data sources

The data used in this study comes from authoritative sources such as the National Bureau of Statistics, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the People’s Bank of China, and various statistical yearbooks, including national and provincial statistical yearbooks, environmental status bulletins, and specialized statistical yearbooks such as the China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Financial Yearbook, China Agricultural Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, and China Tertiary Industry Statistical Yearbook. Missing data for some variables were supplemented using interpolation methods, resulting in a panel dataset for 285 cities from 2009 to 2022.

4 Empirical regression analysis

4.1 Benchmark regression results

This study first estimates the direct impact of FTZs on regional GTI. The p-value of the Hausman test is 0.000, leading us to reject the null hypothesis. This indicates that individual effects are correlated with the explanatory variables, and thus a fixed effects model is appropriate. Additionally, the regression controls for time and regional effects, with the baseline estimation results shown in Table 2. Column (1) includes only the FTZs dummy variable. Columns (2)–(5) sequentially add control variables for economic development, informatization degree, financial development, and government intervention. The estimated coefficient of FTZs is statistically significant and positive across all columns, indicating that the establishment of FTZs significantly promotes GTI in host cities, confirming Hypothesis H1. According to the coefficient in column (5), the establishment of FTZs is associated with an increase of approximately 696.501 units in the local GTI index, demonstrating that FTZs contribute substantially to enhancing regional GTI.

Table 2

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DID | 712.174*** (185.739) | 707.059*** (3.86) | 701.190*** (3.87) | 699.159*** (3.83) | 696.501*** (3.83) |

| Ecde | −91.327 (−1.38) | −100.192 (−1.46) | −115.181* (−1.86) | −138.003** (−2.02) | |

| Deif | −1136.166** (−2.00) | −1338.096* (−1.89) | −1143.642** (−1.90) | ||

| Lefe | −12.942 (−0.64) | −9.314 (−0.43) | |||

| Goin | −246.775 (−1.20) | ||||

| Control Time Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control Region Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cons | 35.831 (1.46) | 951.091 (1.45) | 1079.323 (1.56) | 1255.181** (2.04) | 1518.962** (2.20) |

| N | 3,990 | 3,990 | 3,990 | 3,990 | 3,990 |

| R 2 | 0.660 | 0.680 | 0.682 | 0.690 | 0.688 |

Regression coefficient of the impact of FTZs on GTI.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *,**, *** indicate significance levels of 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively.

4.2 Parallel trend test

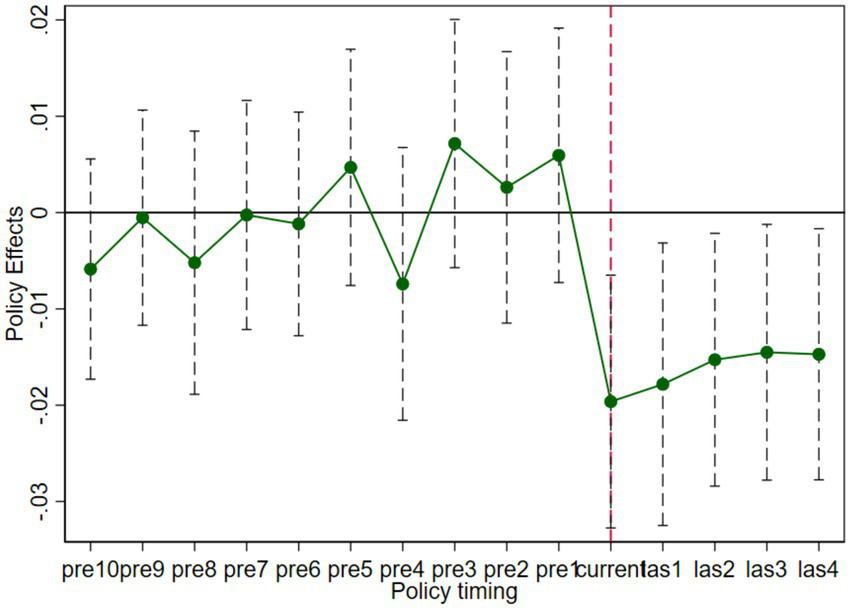

The core assumption of the DID method is that the treatment and control groups should exhibit parallel trends prior to policy implementation. This study employs an event-study approach, generating interaction terms between the treatment group dummy for cities with FTZs and year dummies for periods before and after the policy, replacing the original FTZs variable, and estimating them within the baseline fixed-effects model. To eliminate level differences in coefficients before policy implementation, the pre-policy interaction term coefficients were demeaned. The results (Figure 2) show that the demeaned pre-policy interaction term coefficients fluctuate around zero, and the joint F-test yields F(10,284) = 2.55, p = 0.0058, indicating that the treatment and control groups exhibited similar trends before the policy, supporting the parallel trends assumption. After policy implementation, the interaction term coefficients show an upward trend, with most years significantly negative, suggesting that the FTZs policy effectively promoted the improvement of GTI in the cities where it was implemented (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Results of the parallel trend test.

Figure 3

![A graph showing a scatter plot with blue circles and an orange density curve overlay. The x-axis is labeled "_b[did]…" and the y-axes are "p" on the left and "kdensity beta" on the right. A red horizontal line and a vertical dashed line are also present. A legend indicates blue circles for "p" and the orange line for "kdensity beta."](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1652437/xml-images/frsc-07-1652437-g003.webp)

Results of the placebo test.

4.3 Robustness test

-

Placebo Test. This study conducts a placebo test to examine the robustness of the main results. The sample includes 285 cities, 47 of which host FTZs. For the placebo test, 47 cities are randomly selected from the 285 cities to form a pseudo-treatment group, while the remaining cities serve as the control group. A placebo coefficient (βfalse) is estimated, and this procedure is repeated 1,000 times to generate 1,000 βfalse values. Figure 2 shows the kernel density distribution of the 1,000 estimated placebo coefficients and their corresponding p-values. The mean of βfalse is close to zero, and the majority of p-values are greater than 0.1. The vertical dashed line represents the actual estimated coefficient, which is significantly different from the placebo estimates. These results suggest that randomly assigning treatment groups does not produce a significant effect of FTZs on local GTI. Therefore, the baseline regression results are not driven by random chance, indicating that the findings are policy-relevant and robust.

-

Variable Replacement. To further test the robustness of the baseline regression results, this study employs an alternative dependent variable approach by replacing the original number of green invention patent applications with the number of green utility model patent grants and green invention patent grants. The regression results are presented in Table 3. It can be observed that, whether using the original number of green invention patent applications or the alternative indicators of green utility model patent grants and green invention patent grants, the estimated coefficients of the core explanatory variable FTZs remain significantly positive at the 1% level. This indicates that the promoting effect of FTZs policies on GTI is robust and does not depend on a specific patent type or measurement method.

-

Excluding Policy Interference. In addition to the FTZs policy, other national initiatives—such as the establishment of innovative cities, pilot cities for intellectual property development, “Made in China 2025” cities, and pilot zones for the development of next-generation artificial intelligence—may also influence GTI. To address this, this study sequentially excludes these pilot cities and examines the changes in the regression results. As shown in Table 4, after removing these pilot cities, the regression coefficients of FTZs on green technology remain significantly positive, indicating that the promoting effect of FTZs on GTI is not affected by other policies, thereby confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

-

Robustness Check Using Propensity Score Matching (PSM). To further verify the robustness of the baseline regression results, this study employs the propensity score matching (PSM) method. The probability of a city being selected into an FTZs is estimated via a logistic regression. A 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching is conducted with a caliper of 0.05. After matching, the sample covers 219 cities, totaling 1,114 observations. The balance test indicates that the standardized differences of all covariates between the treatment and control groups are below 10% and statistically insignificant, suggesting that the matched sample achieves good covariate balance. A DID fixed-effects regression is then performed on the matched sample. As shown in Table 5, the coefficients for DID and PSM-DID are 696.501 and 362.696, respectively, indicating that FTZs still have a significantly positive effect on GTI. This confirms the reliability of the policy effect and validates the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Table 3

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of green invention patent applications in the current year | Number of green utility model patent grants in the current year | Number of green invention patent grants in the current year | |

| DID | 696.501*** (3.83) | 891.368*** (4.31) | 245.077*** (4.30) |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control Time Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control Regional Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cons | 1518.962** (2.20) | 3002.706*** (2.87) | 673.847*** (2.79) |

| N | 3,990 | 3,987 | 3,987 |

| R2 | 0.688 | 0.643 | 0.602 |

Regression coefficients of the effect of FTZs on GTI.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *,**, *** represent significance levels of 10, 5, and 1%, respectively.

Table 4

| Variables | Innovative cities | Pilot cities for IP development | “Made in China 2025” cities | Next-generation AI innovation pilot zones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| DID | 638.156** (2.53) | 900.573*** (3.94) | 518.145** (2.50) | 252.344** (2.30) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 1214.055* (1.88) | 1334.131* (1.82) | 578.605 (1.17) | 492.122 (1.51) |

| N | 3,427 | 3,441 | 3,567 | 3,763 |

| R 2 | 0.695 | 0.676 | 0.664 | 0.721 |

Regression results after excluding cities under specific policy pilots.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *,**, *** represent significance levels of 10, 5, and 1%, respectively.

Table 5

| Variable | DID | PSM-DID |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| DID | 696.501*** (3.83) | 362.696** (2.45) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes |

| Control time effects | Yes | Yes |

| Control regional effects | Yes | Yes |

| Cons | 1518.962** (2.20) | 6639.586* (1.85) |

| N | 3,990 | 1,114 |

| R 2 | 0.688 | 0.502 |

Comparison of regression results using PSM-DID.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *, **, *** represent significance levels of 10, 5, and 1%, respectively.

5 Heterogeneity analysis

-

1 Location of FTZs

Considering the significant differences among China’s FTZs in terms of economic development level, policy environment, and demand for GTI, a heterogeneity analysis was conducted by categorizing regions into coastal, inland, and border areas. The results are presented in Table 6. The regression outcomes indicate that the promoting effect of FTZs on GTI varies significantly across regions. In coastal areas, the FTZs coefficient is 930.457 with a t-value of 2.27, significant at the 0.05 level, suggesting that FTZs have a significant positive impact on enhancing GTI in these regions. In inland areas, the DID coefficient is 631.028 with a t-value of 3.55, significant at the 1% level, indicating that the effect of FTZs on GTI is weaker than in coastal areas. In border regions, the DID coefficient is −9.095 with a t-value of −0.15, which is not statistically significant at the 0.1 level, implying a relatively weak promoting effect of FTZs on GTI in these areas. This result may be attributed to the coastal regions’ advantages in foreign investment openness and internationalization, which facilitate the inflow of advanced green technologies and management practices through higher levels of FDI (Langinier et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2025). Additionally, coastal areas benefit from more developed transportation, logistics, and information infrastructure, creating favorable conditions for the diffusion and application of green technologies (Ma et al., 2025; Ahmar et al., 2025).

-

2 Economic development level

Table 6

| Variable | Coastal | Inland | Border |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| DID | 930.457** (2.27) | 631.028*** (3.55) | −9.095 (−0.15) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control time effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control regional effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cons | 853.553* (1.80) | 1011.294** (2.31) | 450.721 (1.52) |

| N | 3,570 | 3,721 | 3,385 |

| R 2 | 0.644 | 0.732 | 0.716 |

Comparison of green finance effects of FTZs in Coastal, Inland, and Border Regions.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *, **, *** represent significance levels of 10, 5, and 1%, respectively.

Further examination of the heterogeneous effects of economic development level on the impact of FTZs on GTI reveals important insights. Per capita GDP is a key indicator for measuring economic development, and regional economic disparities directly influence factors such as demand for GTI, policy support, and market environment. Therefore, we classify the sample into regions with high, medium-high, medium, and low per capita GDP levels, with the benchmark regression results shown in Table 7.

Table 7

| Variable | High | Upper-middle | Middle | Low |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| DID | 1269.635*** (2.75) | 1355.385*** (3.15) | 237.827* (1.94) | −21.972 (−1.02) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control time effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control regional effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cons | 609.745 (1.30) | 57.351 (1.35) | 756.074** (2.01) | 464.367 (1.58) |

| N | 3,497 | 3,497 | 3,497 | 3,483 |

| R 2 | 0.667 | 0.660 | 0.758 | 0.716 |

Impact of FTZs on GTI based on economic development level.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *,**, *** indicate significance levels of 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively.

The results indicate that in regions with high per capita GDP, the promoting effect of FTZs on GTI is 1,269.635, significant at the 1% level, suggesting that economically developed areas have more mature demand and support systems for GTI, allowing FTZs to effectively drive its development. In regions with upper-middle per capita GDP, the effect is 1,355.385, also significant at the 1% level, indicating that although these regions are economically well-off, their infrastructure or policy support for GTI is relatively lagging, making the promoting effect of FTZs more pronounced. In regions with medium per capita GDP, the effect is 237.827, significant at the 10% level, reflecting that these regions have moderate economic levels and still lack sufficient support or demand for GTI, resulting in a weaker effect of FTZs. In regions with low per capita GDP, the effect of FTZs is −21.972 and not significant, indicating that FTZs have no noticeable impact on GTI in these areas. These findings are consistent with the conclusions of Balsalobre-Lorente et al. (2025), Rakpho et al. (2023), Ullah et al. (2024), Meo and Anees (2025), Meo et al. (2024), Meo and Adebayo (2025), and Meo et al. (2025).

6 Mechanism analysis

6.1 Selection of mediating variables

-

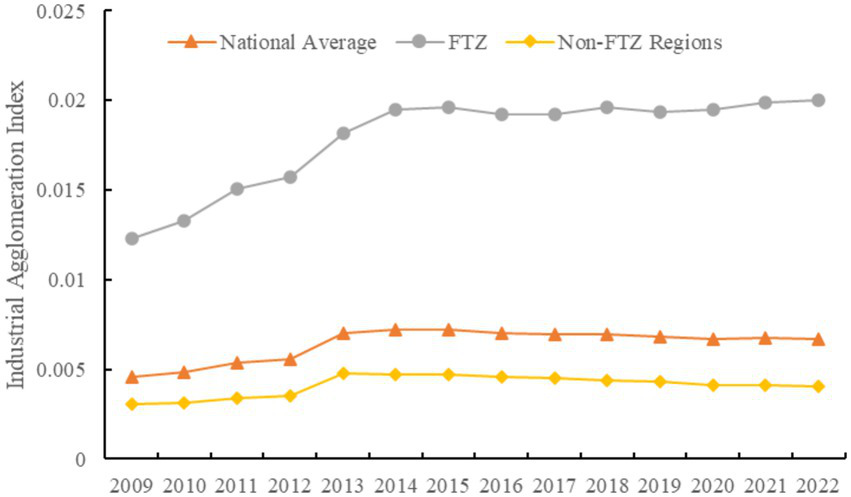

1 Industrial agglomeration

Industrial agglomeration refers to the spatial concentration of businesses, institutions, and related upstream and downstream enterprises in similar or related industries within a specific region. It reflects the spatial distribution and degree of geographical concentration of industries. Many scholars use location entropy to measure industrial agglomeration, as it eliminates regional scale differences and better reflects spatial distribution. Following Chen et al. (2021), this study uses the number of employed persons per unit area to indicate regional industrial agglomeration. Figure 4 presents the results. The national industrial agglomeration level is represented by the average index of 285 cities, FTZ cities by the average of 47 cities, and non-FTZ cities by the average of the remaining 238 cities. From 2009 to 2013, the national industrial agglomeration index increased from 0.0046 to 0.0070, peaking at 0.0072 in 2015, and then fluctuating downward to 0.0067 by 2022. FTZ cities consistently exhibited higher indices, rising from 0.0123 in 2009 to 0.0200 in 2022, with the most notable increase between 2013 and 2016. Non-FTZ cities had relatively low indices, starting at 0.0030 in 2009 and reaching only 0.0040 by 2022, with improvement before 2013 followed by gradual decline.

-

2 Digital economy

Figure 4

Industrial agglomeration index from 2009 to 2022.

The digital economy refers to an economic form that relies on digital technologies and promotes economic activities and social productivity through the Internet, Internet of Things (IoT), big data, artificial intelligence (AI), and cloud computing. Following the research approach of Xia et al. (2024), Iormom et al. (2025a), Ozkan et al. (2025), and Iormom et al. (2025b), this study selects four indicators to measure the level of digital economy development: the number of broadband Internet users per 100 people, the proportion of employees in the computer services and software industry relative to total urban employment, per capita total telecommunication services, and the number of mobile phone users per 100 people.

To aggregate these four indicators into a digital economy index, this study employs Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction. First, all indicators are standardized to ensure positive directionality. Then, principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1 are extracted, retaining only one principal component, which accounts for 91.96% of the cumulative variance, indicating that it effectively represents the overall information. The weights for each indicator are: broadband Internet users per 100 people 0.216, proportion of computer services and software employees 0.211, per capita telecommunication services 0.214, and mobile phone users per 100 people 0.214. According to Table 8, the national digital economy index increased from −0.210 in 2009 to 0.868 in 2022, with FTZs generally exceeding the national average (reaching 0.902 in 2022), indicating that FTZs policies and institutional innovations have significantly promoted the development of the digital economy.

Table 8

| Year | Total average | FTZs | Non-FTZs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | −0.210 | −0.191 | −0.308 |

| 2010 | −0.159 | −0.136 | −0.273 |

| 2011 | −0.095 | −0.073 | −0.202 |

| 2012 | 0.049 | 0.070 | −0.050 |

| 2013 | 0.103 | 0.124 | 0.003 |

| 2014 | 0.341 | 0.370 | 0.198 |

| 2015 | 0.411 | 0.437 | 0.280 |

| 2016 | 0.490 | 0.527 | 0.308 |

| 2017 | 0.539 | 0.571 | 0.380 |

| 2018 | 0.612 | 0.644 | 0.456 |

| 2019 | 0.683 | 0.727 | 0.468 |

| 2020 | 0.721 | 0.758 | 0.536 |

| 2021 | 0.800 | 0.840 | 0.600 |

| 2022 | 0.868 | 0.902 | 0.702 |

Digital economy index from 2009 to 2022.

6.2 Mediating effect analysis

Table 9 presents the analysis of the mediating effects of industrial agglomeration (TROP) and the digital economy (DICE) on the impact of FTZs on the level of GTI. Columns (1) and (2) show the effect of FTZs on industrial agglomeration and the digital economy, respectively, while column (3) introduces the industrial agglomeration variable and examines the effect of FTZs on GTI in the respective cities. Column (4) adds the digital economy variable and evaluates its impact on GTI.

Table 9

| Variable | TROP | DICE | GTI | GTI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| DID | 0.003* (1.77) | 0.108*** (2.78) | 581.793*** (3.98) | 675.083*** (3.92) |

| TROP | 31008.61*** (2.62) | |||

| DICE | 196.839** (2.19) | |||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control time effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Control regional effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cons | 0.010** (2.14) | 0.048 (0.13) | 1203.041** (2.13) | 1509.416*** (2.24) |

| N | 3,987 | 3,987 | 3,987 | 3,987 |

| R 2 | 0.918 | 0.917 | 0.648 | 0.679 |

Mediator effect regression coefficient.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *,**, *** indicate significance levels of 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively.

Columns (1) and (2) demonstrate that FTZs significantly promote both industrial agglomeration and the digital economy in their cities. Columns (3) and (4) show that FTZs significantly enhance the level of GTI, with GTI of 581.793 and 675.083, respectively. The t-values for both are 3.98 (column 3) and 3.92 (column 4), both significant at the 1% level. Further analysis reveals that industrial agglomeration (TROP) has a significant positive impact on GTI, with a regression coefficient of 581.793 and a t-value of 3.98 (column 3), indicating that industrial agglomeration boosts green investment demand and promotes the development of GTI. Similarly, the digital economy (DICE) also plays a significant role in driving GTI, with a regression coefficient of 675.083 and a t-value of 3.92 (column 4), suggesting that the digital economy advances green industry development and further accelerates GTI. The R2 values for the overall regression models are 0.648 (column 3) and 0.679 (column 4), indicating that the models have strong explanatory power. Therefore, the results suggest that FTZs effectively enhance the level of GTI by fostering industrial agglomeration and the digital economy.

To further test the significance of the aforementioned mediation pathways, this study employs the Bootstrap method with 5,000 resamples and calculates bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. The results are shown in Table 10. The mediating effect of industrial agglomeration is 114.708, with a 95% confidence interval of [50.518, 208.072], which does not include 0; the mediating effect of the digital economy is 21.418, with a 95% confidence interval of [9.310, 39.808], also excluding 0. These findings indicate that both mediation pathways—“FTZs → Industrial Agglomeration → GTI” and “FTZs → Digital Economy → GTI”—are statistically significant, thereby supporting the proposed hypotheses.

Table 10

| Mediation pathway | Mediating effect | Bootstrap SE | Bootstrap 95% CI (Percentile) | Bootstrap 95% CI (Bias-Corrected) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DID → Industrial agglomeration → GTI | 114.708** | 39.922 | [48.536, 204.249] | [50.518, 208.072] | Significant |

| DID → Digital economy → GTI | 21.418** | 7.774 | [8.840, 38.875] | [9.310, 39.808] | Significant |

Bootstrap test results of mediation effects.

(1) T-values are in parentheses; (2) *,**, *** indicate significance levels of 10%, 5%, and 1%, respectively.

7 Conclusion and outlook

7.1 Main findings

The research results show.

-

1 According to the regression analysis, the establishment of FTZs significantly enhances the GTI index of the host cities by approximately 696.501 units. This conclusion is supported by robustness tests.

-

2 The promoting effect of FTZs on GTI varies significantly across regions. The effect is strongest in coastal areas, while in inland and border areas, the impact of FTZs on local GTI is not significant. Furthermore, as per capita GDP increases, the effect of FTZs on GTI strengthens significantly.

-

3 FTZs promote the development of green industries through industrial agglomeration and the digital economy, which in turn accelerates the growth of GTI.

7.2 Policy recommendations

Strengthen region-specific policies. Tailor GTI support policies based on the geographical location and economic foundation of each FTZs. In developed coastal regions, leverage geographic and economic advantages to establish international green technology funds, attract multinational R&D centers and leading green technology enterprises, and promote the localization and industrialization of advanced green technologies. At the same time, further enhance the construction of green industry clusters to drive high-quality development of GTI. For inland and remote regions, focus on improving digital infrastructure (e.g., 5G, industrial internet, data centers) to reduce the costs of green technology transactions and applications. Through technology introduction, talent development, and intellectual property protection, accelerate the enhancement of GTI capabilities and narrow the regional innovation gap.

Promote industrial transformation and upgrading. FTZs should accelerate the green transformation of traditional high-pollution industries, with particular emphasis on energy, manufacturing, and chemical sectors, applying green technologies to achieve pollutant reduction and efficient resource utilization. Encourage enterprises to develop projects in new environmentally friendly materials, renewable energy technologies, and smart green equipment, forming industrial clustering effects of GTI. Policies such as tax incentives, fiscal subsidies, and green procurement can be used to motivate enterprises to invest in green technologies, promoting coordinated development across the green industrial chain.

Enhance the policy support system. Governments should increase financial support for key green technology R&D, and introduce incentives such as innovation vouchers and green technology awards to encourage breakthrough research. Optimize regulatory and standards systems for GTI, establish transparent evaluation and certification mechanisms, and lower market entry barriers. Encourage financial institutions to participate in investment and risk-sharing for GTI, improving policy precision and implementation effectiveness.

Advance the greening of the financial system. Promote the innovation and development of green financial instruments, such as green bonds, green funds, green loans, and green insurance, to provide diversified financing channels for green technology enterprises. Strengthen the coordination between financial policies and industrial policies to ensure GTI receives sufficient support in funding, market access, and policy environment. In coastal FTZs, guide international financial institutions to invest in green projects; in inland FTZs, focus on developing local green financing platforms and digital financial services to reduce corporate financing costs.

7.3 Limitations and future research directions

Despite the robust findings of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on city-level panel data from 2009 to 2022, which may not fully capture micro-level firm behaviors or sector-specific dynamics. Future research could employ firm-level or industry-level datasets to provide more granular insights into the mechanisms through which FTZs promote green technological innovation. Second, although this study considers key mediating factors such as industrial agglomeration and the digital economy, other potential channels—such as human capital mobility, international technology spillovers, and environmental regulation stringency—were not explicitly examined. Future studies could incorporate these additional factors to enrich the understanding of FTZs’ effects on green innovation. Third, this paper focuses on the context of China; thus, the generalizability of the results to other countries or regions with different institutional settings may be limited. Comparative studies across multiple countries or regions could help validate and extend the findings.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

SJ: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HG: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SY: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Validation, Funding acquisition. HZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

HZ was employed by Zhongshang Guoneng Group Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ahmar M. Ali F. He C. Jiang Y. (2025). Understanding the role of socio-economic, demographic, environmental, infrastructural, and institutional attributes in the uptake of biogas technology in Pakistan: proposing and implementing a novel step-wise framework. Energy Econ.148:108699. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2025.108699

2

Akbari M. Azbari M. E. Chaijani M. H. (2019). Performance of the firms in a free-trade zone: the role of institutional factors and resources. Eur. Manag. Rev.16, 363–378. doi: 10.1111/emre.12163

3

Aydin M. Degirmenci T. Ahmed Z. Apergis N. (2025). Do the energy taxes, green technological innovation, and energy productivity enable the green energy transition in EU countries? Evidence from novel panel data estimators. Renew. Energy. 249:123236. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2025.123236

4

Balsalobre-Lorente D. Topaloglu E. E. Nur T. Pilař L. (2025). The management of environmental taxation, ICT, and financial development over the load capacity in advanced economies. J. Environ. Manag.392:126878. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126878

5

Bao T. Dai Y. Feng Y. Liu S. Wang R. (2023). Trade liberalisation and trade and capital flows: evidence from China pilot free trade zones. World Econ.46, 1408–1422. doi: 10.1111/twec.13387

6

Beenstock M. Felsenstein D. (2010). Marshallian theory of regional agglomeration. Pap. Reg. Sci.89, 155–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1435-5957.2009.00253.x

7

Bi S. Shao L. Tu C. Lai W. Cao Y. Hu J. (2023). Achieving carbon neutrality: the effect of China pilot free trade zone policy on green technology innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30, 50234–50247. doi: 10.1007/s11356-023-25803-1

8

Bukht R. Heeks R. (2017). Defining, conceptualising and measuring the digital economy. Int. Organ. Res. J.13, 143–172. doi: 10.17323/1996-7845-2018-02-07

9

Carlsson B. (2004). The digital economy: what is new and what is not?Struct. Change Econ. Dyn.15, 245–264. doi: 10.1016/j.strueco.2004.02.001

10

Cen C. Wang P. (2024). Platform advantages or" policy trap" for neighbors? Export effects of establishing free trade zone in China: a quasi-natural experiment. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance96:103634. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2024.103634

11

Chen A. Dai T. Partridge M. D. (2021). Agglomeration and firm wage inequality: evidence from China. J. Reg. Sci.61, 352–386. doi: 10.1111/jors.12512

12

Chen W. Hu Y. Liu B. Wang H. Zheng M. (2022). Does the establishment of pilot free trade test zones promote the transformation and upgradation of trade patterns?Econ. Anal. Policy76, 114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2022.07.012

13

Chen C. Xie X. (2025). Digital economy development, industrial structure development, and green finance. Finance Res. Lett. 108152. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2025.108152

14

David P. A. Rosenbloom J. L. (1990). Marshallian factor market externalities and the dynamics of industrial localization. J. Urban Econ.28, 349–370. doi: 10.1016/0094-1190(90)90033-J

15

Degirmenci T. Aydin M. Cakmak B. Y. Yigit B. (2024). A path to cleaner energy: the nexus of technological regulations, green technological innovation, economic globalization, and human capital. Energy311:133316. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2024.133316

16

Degirmenci T. Okoth E. Erdem A. (2025). Political governance and tourism development: the roles of globalisation, stability, economic growth, and taxation in top destinations. Tour. Recreat. Res., 1–13. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2025.2465963

17

Destek M. A. Degirmenci T. Kocak E. (2025). How does bank loans affect carbon emissions? A comparison of household and business loans. Environ. Develop. Sustain., 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10668-025-06232-1

18

Fan G. Xie X. Chen J. Wan Z. Yu M. Shi J. (2022). Has China's free trade zone policy expedited port production and development?Mar. Policy137:104951. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104951

19

Feng Y. Li Y. Nie C. (2023). The effect of place-based policy on urban land green use efficiency: evidence from the pilot free-trade zone establishment in China. Land12:701. doi: 10.3390/land12030701

20

Ge Q. Q. Liu X. H. Zhang Y. C. Liu S. Q. (2023). Has China’s free trade zone policy promoted the upgrading of service industry structure?: based on the empirical test of 185 prefecture-level cities in China. Econ. Anal. Policy80, 1171–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2023.10.008

21

Guan C. Huang J. Jiang R. Xu W. (2023). The impact of pilot free trade zone on service industry structure upgrading. Econ. Anal. Policy78, 472–491. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2023.03.024

22

He Y. Ma J. (2025). Collaborative development of logistics hubs and free trade zones, digital finance and economic resilience. Financ. Res. Lett.:108229. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2025.108229

23

Iormom B. I. Iorember P. T. Diyoke K. Abbas J. (2025a). Urbanization, digital systems adoption, and environmental integration in the Euro-Mediterranean region: is the IT transition green?Energy Res. Lett.6. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-5349024/v1

24

Iormom B. I. Jato T. P. Ishola A. Diyoke K. (2025b). Economic policy uncertainty, institutional quality, and renewable energy transitioning in Nigeria. Energy Res. Lett.6. doi: 10.46557/001c.127515

25

Javaid M. Haleem A. Singh R. P. Sinha A. K. (2024). Digital economy to improve the culture of industry 4.0: a study on features, implementation and challenges. Green Technol. Sustain.2:100083. doi: 10.1016/j.grets.2024.100083

26

Jiang Y. Wang H. Liu Z. (2021). The impact of the free trade zone on green total factor productivity——evidence from the Shangh pilot free trade zone. Energy Policy, 148:112000.

27

Langinier C. Martínez-Zarzoso I. RayChaudhuri A. (2025). Environmental regulations and green innovation: the role of trade and technology transfer. Energy Econ.150:108755. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2025.108755

28

Lei C. Lang W. Mei H. Fang H. Qiangqiang S. (2024). The impact of the free trade zones construction on green technological innovation efficiency——evidence from 288 cities in Chinese. Heliyon10:e27728. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27728

29

Li L. Jiang H. Liu M. Wu Q. (2023). Developing a model between trade openness and economic recovery: panel data analysis for Chinese pilot-regions. Renew. Energy217:119132. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2023.119132

30

Lin X. Jing X. Cheng F. Wang M. (2024). Exploration of port environmental efficiency measurement and influential factors in the Yangtze River Delta pilot free trade zone. Mar. Pollut. Bull.206:116766. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116766

31

Ling J. Peng J. Peng T. (2024). Can institutional opening-up promote green development in cities? Evidence from China's pilot free trade zones. J. Clean. Prod.473:143573. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143573

32

Ma J. Ni J. Zhao Y. Wu J. (2025). Environmental regulation, digital technology application and low-carbon supply chain resilience: evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag.389:126087. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126087

33

Meo M. S. Adebayo T. S. (2025). Role of financial regulations and climate policy uncertainty in reducing CO2 emissions—an application of bootstrap subsample rolling-window Granger causality. Clean Techn Environ Policy 27, doi: 10.1007/s10098-024-02991-z

34

Meo M. S. Ademokoya A. A. Abubakar A. B. (2025). Energy-related uncertainty, financial regulations, and environmental sustainability in the United States. Clean Techn. Environ. Policy27, 2269–2288. doi: 10.1007/s10098-024-02961-5

35

Meo M. S. Anees A. (2025). Tech collaboration & digital inclusion: reshaping global trade in the age of climate policy. Sustainable Futures. 10, 100890. Avilable online at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666188825004551

36

Meo M. S. Erum N. Ayad H. (2024). Understanding how climate preferences, environmental policy stringency, and energy policy uncertainty shape renewable energy investments in Germany. Clean Techn. Environ. Policy26, 4483–4503. doi: 10.1007/s10098-024-02876-1

37

Ozkan O. Iormom B. I. Usman O. Uzuner G. (2025). Fossil fuel efficiency as a pathway to decarbonisation and the role of international trade: A perspective of the LCC hypothesis: O. Development and Sustainability: Ozkan et al. Environment, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10668-025-06351-9

38

Pan A. Cao X. (2024). Pilot free trade zones and low-carbon innovation: evidence from listed companies in China. Energy Econ.136:107752. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107752

39

Rakpho P. Chitksame T. Kaewsompong N. (2023). The effect of environmental taxes and economic growth on carbon emission in G7 countries applying panel kink regression. Energy Rep.9, 1384–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2023.05.185

40

Shahid R. Shahid H. Shijie L. Mahmood F. Yifan N. (2024). Impact of opening-up on industrial upgrading in global value chain: a difference-in-differences estimation for Shanghai pilot free trade zone. Kybernetes53, 6139–6154. doi: 10.1108/K-03-2023-0440

41

Sun J. Fang X. Gao X. Dai G. (2025). Does the free trade zone strategy promote urban low-carbon transformation? Experimental evidence from China. Sustain. Futures9:100431. doi: 10.1016/j.sftr.2025.100431

42

Ullah S. Niu B. Meo M. S. (2024). Digital inclusion and environmental taxes: a dynamic duo for energy transition in green economies. Appl. Energy361:122911. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.122911

43

Wang G. Hou Y. Du S. Shen C. (2023). Do pilot free trade zones promote green innovation efficiency in enterprises?–evidence from listed companies in China. Heliyon.9:e21079. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21079

44

Xia L. Baghaie S. Sajadi S. M. (2024). The digital economy: challenges and opportunities in the new era of technology and electronic communications. Ain Shams Eng. J.15:102411. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2023.102411

45

Xu S. Shen R. Zhang Y. Cai Y. (2024). Fostering regional innovation efficiency through pilot free trade zones: evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy.81, 356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2023.12.004

46

Xu M. Wang H. Geng H. Hong H. Wu L. (2024). Study on rapid policy-based strategic environmental assessment: taking China’s regional development policy in Zhejiang pilot free trade zone as an example. Water-Energy Nexus7, 227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.wen.2024.09.001

47

Yao D. Whalley J. (2016). The China (Shanghai) pilot free trade zone: background, developments and preliminary assessment of initial impacts. World Econ.39, 2–15. doi: 10.1111/twec.12364

48

Zhao A. Wang J. Guan H. (2022). Has the free trade zone construction promoted the upgrading of the city’s industrial structure?Sustainability14:5482. doi: 10.3390/su14095482

49

Zhao R. Xu J. Zhao Y. Feng Y. (2025). Resource allocation pattern to green technology innovation efficiency: synergy between environmental resource orchestration and firms' digital capabilities. J. Innov. Knowl.10:100760. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2025.100760

Summary

Keywords

free trade zone, green technological innovation, mediation effect, mechanism testing, difference-in-differences

Citation

Zhang H, Jia S, Ren B and Ge H (2025) Does the free trade zone promote green technological innovation?—evidence from the perspective of industrial agglomeration and digital economy in 285 cities in China. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1652437. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1652437

Received

27 June 2025

Accepted

30 September 2025

Published

28 November 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Xiang Gao, Shanghai Business School, China

Reviewed by

Muhammad Saeed Meo, Sunway University, Malaysia

Bruce Iortile Iormom, University of Mkar, Nigeria

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Jia, Ren and Ge.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongling Ge, Hongling.Ge@cqu-edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.