Abstract

Disasters are frequently framed as opportunities for transformative change. Yet in practice, recovery processes often restore unsustainable systems under the guise of resilience or return to normal. This article examines whether, how, and under what conditions post-disaster recovery can catalyze transformative recovery pathways with a focus on climate mitigation and adaptation. Our study presents an interdisciplinary analytical framework that integrates insights from transformative research, sustainability transitions, and resilience thinking, providing a pragmatic heuristic to navigate post-disaster recovery efforts. We apply the framework to four case studies that represent different systems triggered by different disruptions: agriculture in Italy (drought), housing in Türkiye (earthquake), mobility in Spain (flood), and energy in Ukraine (war). Our findings across the cases show that most recovery efforts fall short of reconfiguring the systems in focus, primarily reproducing pre-disaster patterns, with recovery processes commonly characterized by siloed governance, technocratic fixes, and fragmented activities. Still, disasters can also open opportunities for new climate solutions, collaborations, and narratives that can challenge existing regimes and path dependencies. This is possible through addressing the enablers and barriers that cut across different spheres of transformations. Based on the findings, we argue that transformative recovery cannot be enabled purely through risk management, technical adaptation, or return to normal, but must engage with questions of power, meaning, and governance. The study offers researchers a lens to analyze transformation potential across various types of systems and disruptions and provides policymakers and practitioners with insight into the conditions that are important for transformative recovery.

Introduction

With the increase of climate-related extreme weather events and growing global instability, disasters and other shocks have become more frequent and harder to manage. Post-disaster recovery is often framed as a “window of opportunity” for sustainable transformations, with crises acting as catalysts toward systemic change (Pelling, 2011). However, in practice, the urgent need to rebuild what was destroyed or lost tends to overshadow deeper reflections about what could, or should, be reimagined. Current evidence on climate change adaptation and post-disaster recovery endeavors suggests that meaningful changes in sustainability and climate governance are infrequent and difficult to achieve (Davidson et al., 2025).

To deepen understanding of how disasters may open or foreclose windows of opportunity for systemic transformation, recent studies highlight the potential and limitations of post-crisis experimentation. Davidson et al. (2025) introduce the concept of Natural Disaster–Induced Sustainability Experimentation based on the 2022 Queensland floods, showing how such events can catalyze innovative practices and leadership. Yet, they caution that without institutional support, these experiments often remain fragile and short-lived. Similarly, Rutherford et al. (2024), examining the 2022 Northern Rivers floods in New South Wales, show that while crises can enable new cross-scalar governance arrangements, entrenched institutional routines and fragmented responsibilities frequently undermine sustained change. Among others, factors in play include pre-existing conditions, degrees and frequency of disruptions, and features of political regimes (Povitkina et al., 2025). Shocks create ruptures between the old and the new, with outcomes being both open-ended and subject to manipulation, given the possibility to invoke emergency frames (Patterson et al., 2021). This double-edged nature of disruptions requires navigating transformative and non-transformative possibilities.

This challenge raises a few critical questions. Are disasters destined to reinforce the status quo? And under which conditions could recovery efforts enable alternative futures? While it's challenging to trace all the activities that follow disasters, climate adaptation and mitigation present a specific area that is particularly linked to post-disaster recovery. The urgency of climate action is closely linked to the increasing frequency of disasters, while mitigating the impacts of future disasters depends on how recovery efforts incorporate the lessons learned and address the root causes of unsustainability. Within this study, we therefore focus on the changes in climate mitigation and adaptation efforts within different systems, in the follow-up to major disruptions that trigger critical systems. To explore this, our analysis is structured around two interrelated questions:

-

How do post-disaster recovery processes engage climate transformation elements?

-

What are the barriers and enablers that shape these engagements?

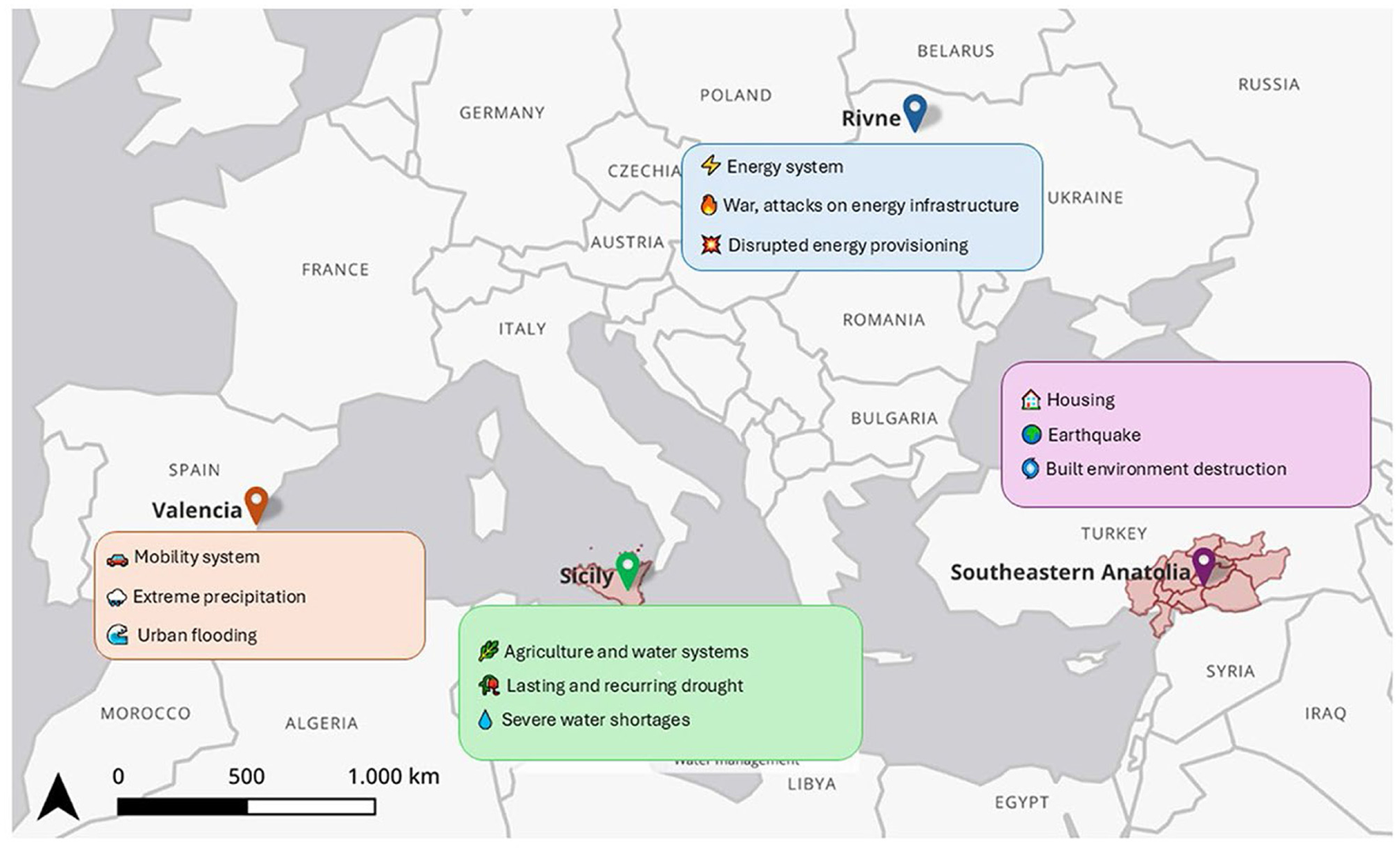

We investigate these questions through an analysis of four critical provisioning systems: agriculture in Sicily (Italy), housing in Southeastern Anatolia (Türkiye), mobility in València (Spain), and energy in Rivne (Ukraine). Each of these systems is significant for climate action and have experienced a distinct form of disruption: drought, earthquake, flood, and war, respectively (Figure 1). The cases provide a diverse set of empirical contexts to interrogate the dynamics of recovery and the potential for transformation. While they are not directly comparable, the cases resemble common features that allow for learning across diverse geographies, systems, and types of disruptions.

Figure 1

Locations of the selected case studies.

The study uses an interdisciplinary analytical framework that combines the Multi-level Perspective from the field of sustainability transitions (Geels, 2002; Geels and Schot, 2007), the Three Spheres of Transformation (O'Brien and Sygna, 2013) and the typology of system patterns with regard to resilience and sustainability by the European Environment Agency (2024) (EEA). The framework was designed to be able to grasp aspects that are commonly overseen by siloed approaches that rely on disciplinary perspectives and is presented further in detail and allowing for within-case depth and cross-case insights. Throughout the development of the cases, we held iterative team discussions that supported interpretive alignment, supporting the identification of recurring governance patterns, enabling conditions, and limitations across the cases.

This paper contributes to the emerging interdisciplinary studies of transformative resilience and recovery by tracing how climate mitigation and adaptation goals are engaged or neglected in recovery processes, and by identifying patterns that shape the potential for long-term system change. By attending to both enablers and barriers, and drawing insights from diverse contexts, the study seeks to inform more coherent, inclusive, and future-oriented approaches to post-disaster governance.

The study is further structured as follows. In the Materials and methods section, we introduce the framework and the main ideas guiding our thinking on recovery and transformations. We also introduce our approach to the case study selection and how we approached the collection and analysis of evidence. In the Results, we present a narrative for each case study based on a common structure, highlighting main developments and insights. Further, in the Analysis section, we provide a cross-cutting analysis of cases along the three spheres of transformations and regarding sustainability and resilience patterns. In the Discussion section, we connect our insights to broader evidence and debates around transformative recovery along with the main themes emerging from our analysis. In Conclusion, we reflect on the potential for further research for advancing transformative recovery pathways.

Materials and methods

Theoretical background and analytical framework

Disaster recovery has traditionally been situated within the Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) paradigm, codified in frameworks such as the Hyogo Framework for Action (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction Secretariat, 2015). This framework emphasizes preparedness, early warning, and recovery as central strategies for reducing vulnerability and managing hazards. However, DRR has often operated through restoration-oriented logic, seeking to return systems to pre-crisis conditions. While such strategies may mitigate immediate risks, they risk reinforcing social and ecological vulnerabilities—particularly when structural inequalities, fragmented governance, or extractive economic practices are left unchallenged (Gaillard, 2010; Tierney, 2020; Wisner et al., 2004). Moreover, the uptake of emergency frames in the aftermath of disasters can be used to reinforce previous agendas, incumbent power, and unsustainable trajectories (Patterson et al., 2021).

Considering these critiques, Build Back Better (BBB) was introduced as a corrective approach within the DRR agenda. Formalized in the Sendai Framework, BBB was intended to reframe recovery as an opportunity for improvement—not simply “build back the same.” It emphasized the integration of disaster preparedness, infrastructure resilience, and institutional strengthening into recovery processes (UNDRR, 2015). Importantly, BBB also introduced sustainability elements, including measures for climate resilience and equity. However, its implementation has remained uneven and largely technocratic, commonly defaulting to infrastructure-centric and efficiency-driven projects without considering broader changes (González-Muzzio et al., 2021; Gould and Lewis, 2018).

Acknowledging the limitations of existing approaches, this study aims to advance a more systemic and transformative approach to post-disaster recovery, drawing on insights from interdisciplinary fields of sustainability transitions, transformative research, and resilience studies. Our analysis is also informed by complementary insights from several other research areas and conceptual developments that have explored implications of and responses to major shocks, disruptions and disasters, such as disaster studies, emergency frames (Patterson et al., 2021), transformative adaptation (Davidson et al., 2025; Nightingale et al., 2022; Novalia and Malekpour, 2020), and political science (Povitkina et al., 2025).

In what follows, we structure our analytical framework around three interconnected dimensions of recovery. First, disruption: how crises destabilize existing regimes and open windows of opportunity. Second, response and immediate recovery: how actors engage within these openings across the three spheres of transformation. Third, stabilization and long-term recovery: how recovery pathways consolidate into new configurations with respect to resilience and sustainability.

Disruption and destabilization

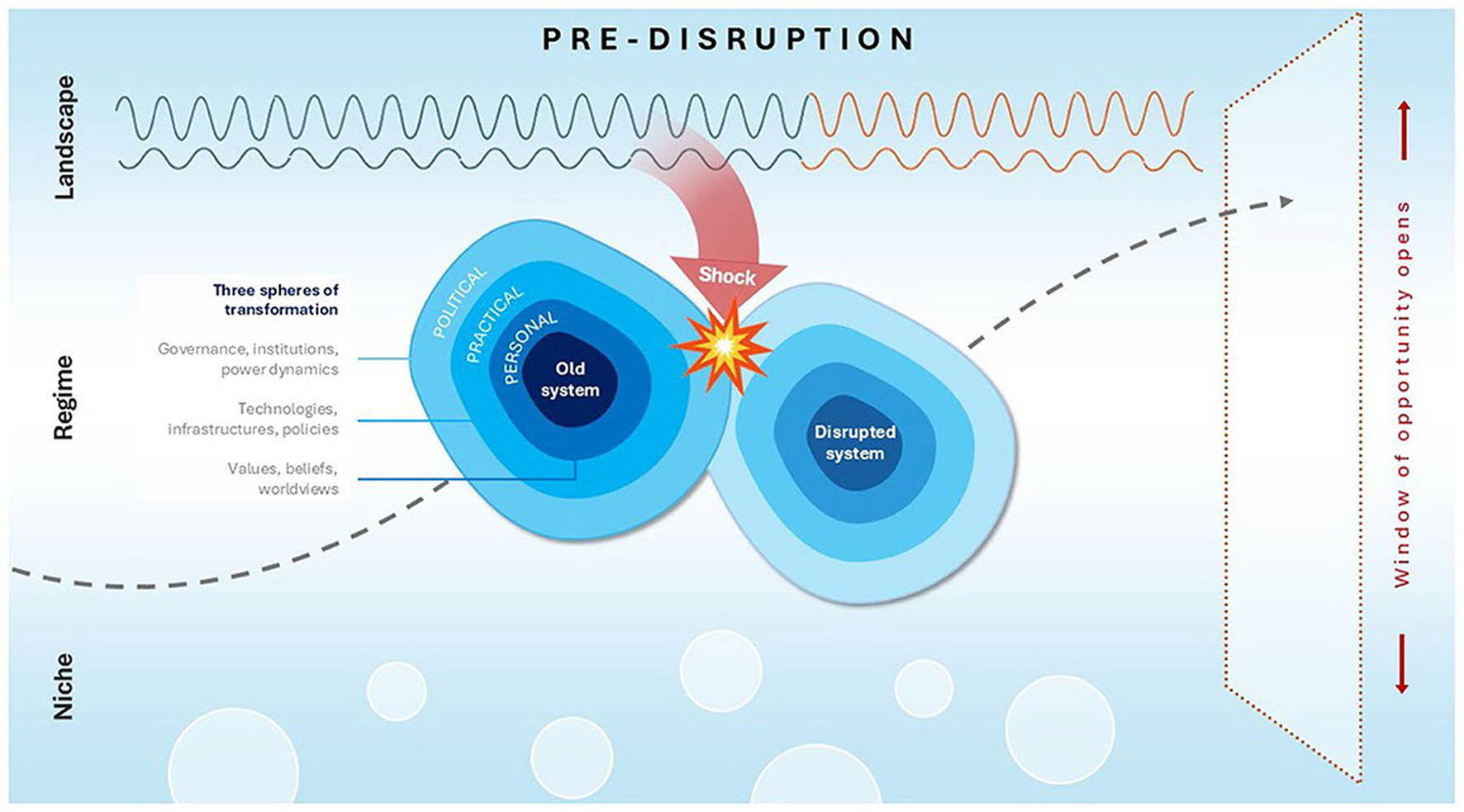

Transition theory, and particularly the multi-level perspective (MLP), frames systemic change as the outcome of interactions between niche innovations, dominant socio-technical regimes, and broader landscape pressures (Geels, 2002; Geels and Schot, 2007; Smith et al., 2005) Socio-technical regimes—such as energy, mobility, housing, or food—are stabilized by the interplay of technologies, policies, norms, and institutions (see Figure 2). These regimes tend to resist change due to strong path dependencies and “institutional lock-in.”

Figure 2

System destabilization through disruption.

Crises, including natural disasters, pandemics, and wars, can act as landscape shocks: they disrupt routines, weaken the legitimacy of existing systems, and create political and institutional fluidity. Such disruptions may open “windows of opportunity” for systemic experimentation and transformative alternatives (Avelino, 2017; Geels, 2014; Loorbach et al., 2017). To analyze these dynamics, we build on the MLP heuristic but extend it through the concept of provisioning, which highlights human needs and biophysical processes often overlooked in socio-technical perspectives (Schaffartzik et al., 2021).

In addition, we draw on the growing field of transformative research, which emphasizes that systemic change occurs across three interrelated spheres in the system (see Figure 2) (O'Brien et al., 2023; O'Brien and Sygna, 2013):

-

The practical sphere (what): technologies, infrastructures, and formal policies or actions.

-

The political sphere (how): governance arrangements, institutional dynamics, and power relations.

-

The personal sphere (why): values, beliefs, worldviews, and identities.

Transformation becomes possible when these spheres reinforce one another—when practical interventions are underpinned by institutional reforms and grounded in shared imaginaries. This framework has gained influence in climate governance, where it challenges technocratic adaptation and emphasizes more holistic and culturally embedded approaches (Head, 2022; Leach et al., 2015; O'Brien, 2018). It also highlights the symbolic and emotional dimensions of recovery: whether crises are interpreted as opportunities, ruptures, or threats depends on shared narratives of loss, justice, hope, and renewal (Eriksen et al., 2021; Kaika, 2017). Figure 2 illustrates this stage of destabilization, integrating the MLP, the three spheres of transformation, and conceptualizations of socio-political shocks (Geels and Schot, 2007; Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., 2020; O'Brien and Sygna, 2013).

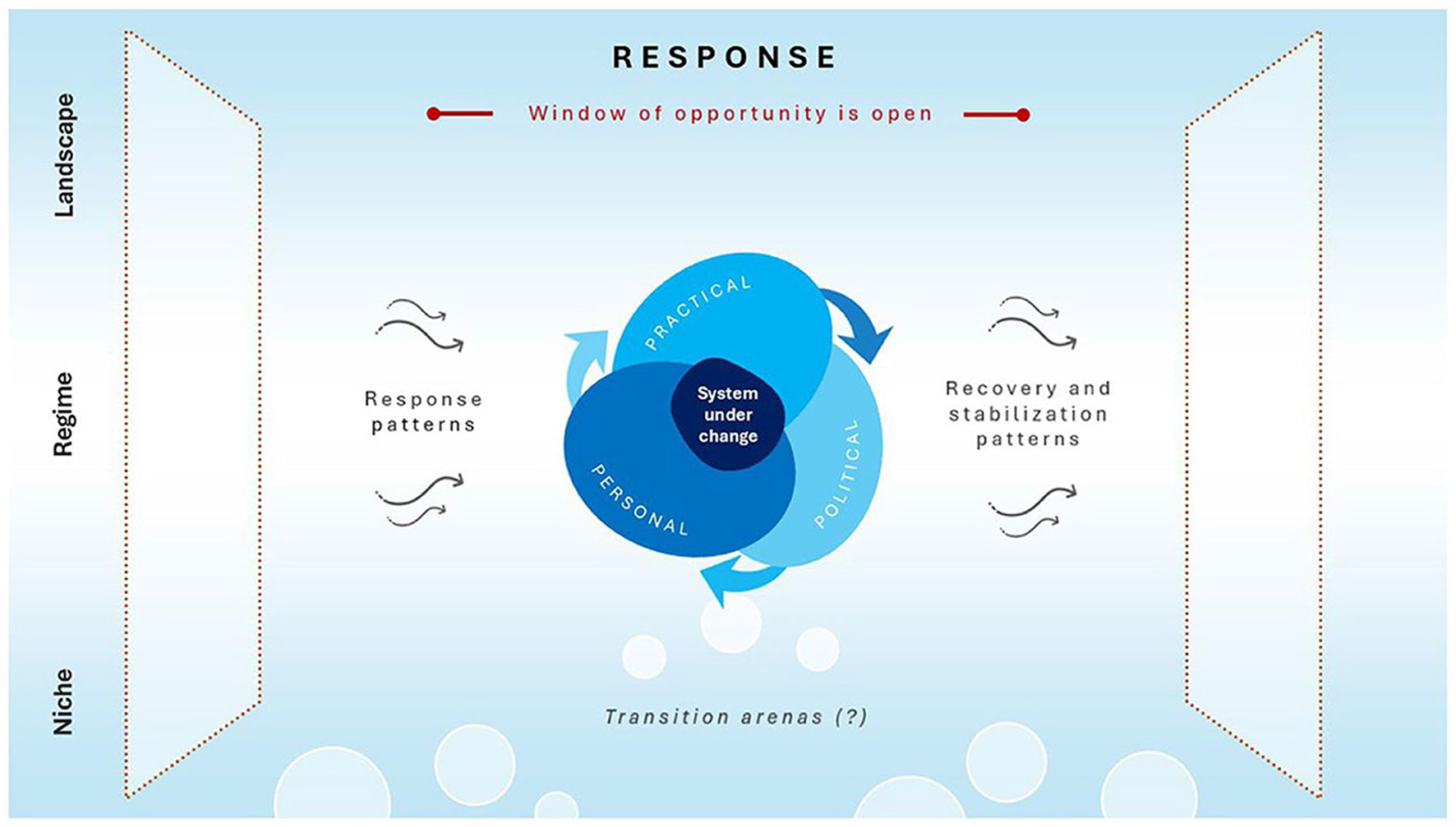

Response and immediate recovery

While disasters may disrupt regimes and open temporary space for alternative pathways, transformative recovery outcomes are far from guaranteed (Davidson et al., 2025; Povitkina et al., 2025). To seize such openings, transition scholars emphasize the role of transition arenas—dedicated, experimental governance platforms that bring together diverse actors across sectors to co-develop shared visions, strategies, and innovations (Avelino, 2017; Geels, 2014). These arenas create protected spaces for deliberation, learning, and coordination across system levels, which is especially critical in post-disaster contexts marked by fragmentation and inertia. Within the window of opportunity, change can unfold across the practical, political, and personal spheres (O'Brien and Sygna, 2013). Responses to disruption may trigger processes such as the upscaling of niche innovations, which can subsequently stabilize into emerging recovery pathways.

Figure 3 situates this stage, highlighting the possibilities of reconfiguration during the window of opportunity. Together, Figures 2, 3 illustrate a dynamic sequence: disruption destabilizes systems, and arenas of response shape whether recovery reinforces the status quo or advances systemic transformation.

Figure 3

System reconfiguration possibilities emerge within the window of opportunity.

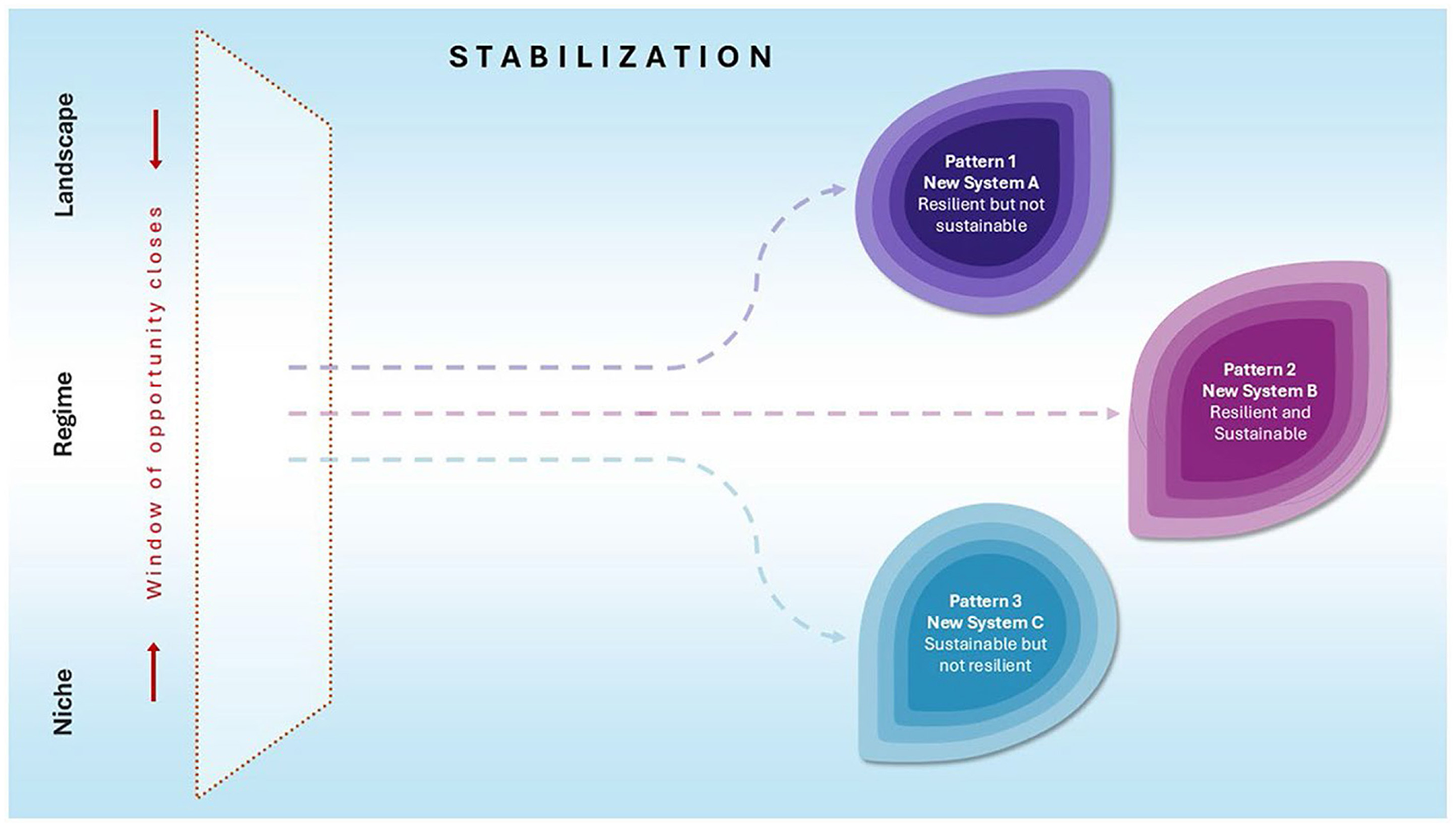

Stabilization and new system configurations

The final component of our framework concerns the qualities of the new system that emerge after disruption. Moving beyond the logic of simply “building back the same,” the European Environment Agency European Environment Agency, (2024) offers a compelling typology of trajectories: (i) Pattern 1: resilient but not sustainable, (ii) Pattern 2: sustainable but not resilient, and (iii) Pattern 3: sustainable and resilient (transformative resilience). The EEA's Garden example offers an intuitive and symbolic way of distinguishing between three system patterns (Table 1).

Table 1

| Pattern | Description | Example (garden example) |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern 1: resilient but not sustainable | •This trajectory represents systems that can recover from disruption in the short term but remain locked into unsustainable practices. The system survives, but only at the cost of its ecological and social foundations | •In the garden example, this is like using pesticides to quickly deal with pests—producing visible results but degrading the soil, biodiversity, and long-term resilience |

| Pattern 2: sustainable but not resilient | •This represents systems that are aligned with long-term sustainability goals (e.g., organic farming or low-impact technologies) but lack resilience to shocks. These systems fail when confronted by unanticipated stressors | •In garden terms, it's like a permaculture garden that lacks protective structures during a storm—valuable, but vulnerable |

| Pattern 3: transformative sustainability and resilience | •This is the desired trajectory, where systems adaptively reorganize after disruption and improve both their resilience and sustainability over time. This pattern emphasizes polycentric governance, innovation, local knowledge, and long-term vision | •The garden example here includes strategic diversity (different crops, pollinators, layered trees), learning from past shocks, and proactive care—representing systems that flourish through disruption, not despite it |

Three patterns of resilience and sustainability, based on European Environment Agency (2024).

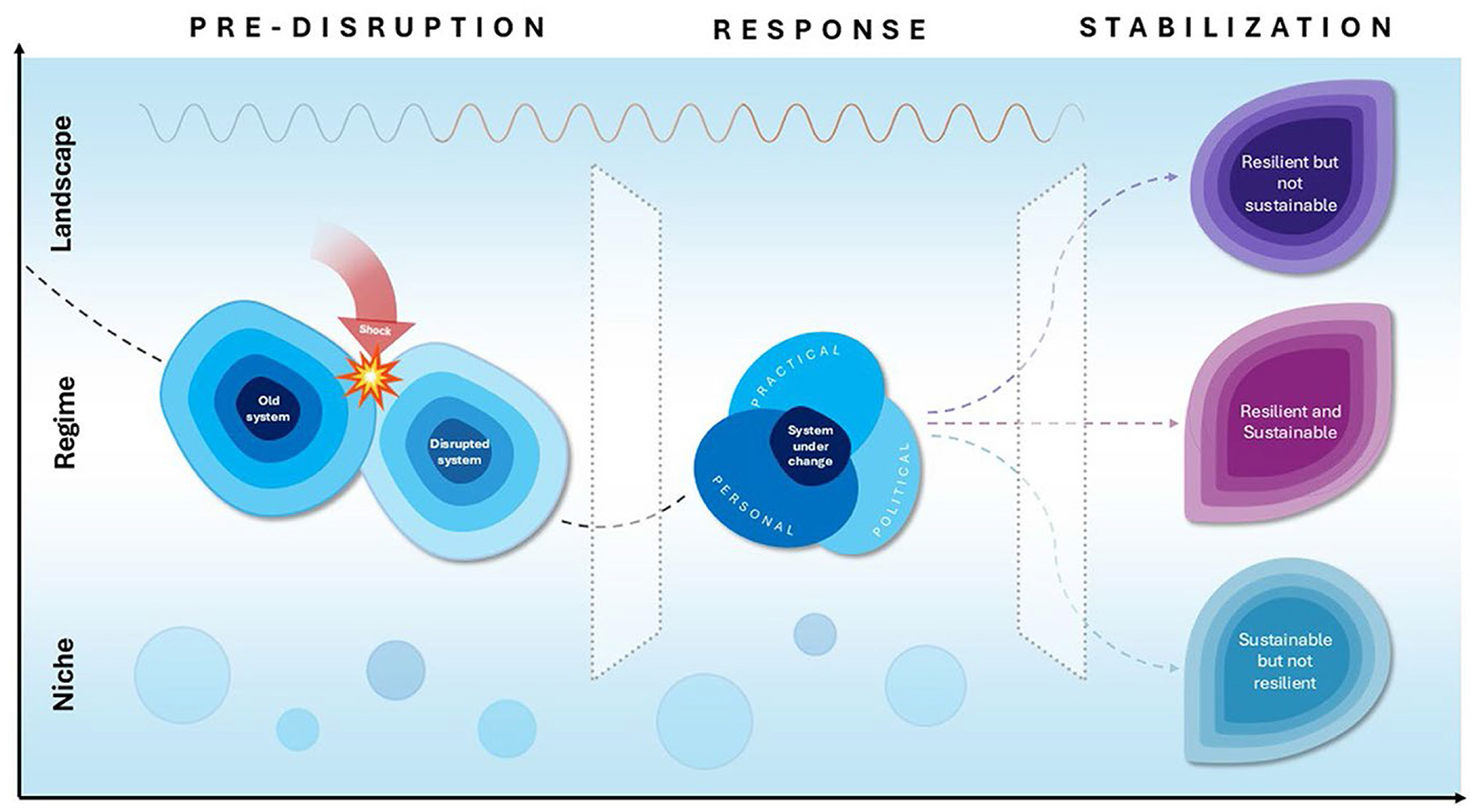

As the window of opportunity closes, the reconfigured system stabilizes and may follow one of the possible pathways. Figure 4 situates the described patterns within the broader sequence introduced earlier: following disruption (Figure 2) and the opening of a window of opportunity for responses (Figure 3), recovery pathways eventually stabilize into new systemic configurations. These may align with any of the three EEA patterns (European Environment Agency, 2024) —or revert to business-as-usual “building back the same”—depending on how responses unfold across the practical, political, and personal spheres (O'Brien et al., 2023). The concept of different recovery pathways also resonates with previous research on regime reconfiguration following socio-political shocks, which have informed our interpretation of the EEA typology (Herrfahrdt-Pähle et al., 2020).

Figure 4

Three generic recovery pathway patterns.

We use this typology to interrogate whether post-disaster interventions restore, incrementally adjust, or reorganize systems toward resilience and sustainability. By juxtaposing empirical evidence with this framework, we articulate a concept of transformative recovery, a process in which crises are leveraged not only to rebuild but also to reimagine and reconfigure systems toward both resilience and sustainability.

Figure 5 presents the overall analytical framework, integrating the MLP that frames the system configuration (Geels and Schot, 2007), the three spheres of transformation that unpack the dimensions of change (O'Brien and Sygna, 2013), and possible system reconfiguration options represented by the EEA resilience and sustainability pathways (European Environment Agency, 2024).

Figure 5

Transformative recovery analytical framework.

The framework aims to assess both the logic of recovery and the mechanisms that enable or constrain transformation. This structured approach helps trace not only what is rebuilt, but also how and to what ends, and whether the resulting configuration is resilient and/or sustainable.

Methodological approach and case study selection

This study employs an exploratory, multi-case study design to investigate how post-disaster recovery processes engage—or fail to engage—with elements of transformative recovery regarding climate adaptation and mitigation. Rather than comparing cases systematically, we aim to investigate how recovery trajectories unfold in different contexts, each shaped by distinct types of disruption, and what can be learned across those contexts. This approach is grounded in interpretive research traditions that value contextual depth and situated knowledge (Flyvbjerg, 2006; Yanow, 2000).

The selection of our cases follows a purposive logic, reflecting the inclusion of diverse forms of disruption (i.e. war, drought, earthquake, flood), governance scales (municipal, metropolitan, regional), and timescales of recovery (from acute to protracted). Such diversity enables the identification of patterns, blockages, and openings for transformative climate-centered recovery across different contexts, without assuming equivalence or generalizability. This strategy is consistent with approaches taken in recent climate governance research that uses heterogeneity to map typologies or identify enabling conditions (Boyd and Juhola, 2015; Castán Broto and Bulkeley, 2013). We treat the diversity of cases analyzed as sources of unique and distinct insights and as an opportunity for learning, while making it explicit that the cases are not directly comparable.

Data collection and analysis

Each case study was conducted by researchers with prior engagement in the specific context and sector, drawing on a combination of primary and secondary data. Data collection was designed to capture recovery processes using the following methods:

-

Policy and document analysis: a comprehensive review of policy documents, such as national disaster management plans, climate action plans, building codes, recovery strategies, and related reporting. This analysis allowed us to identify relevant policy objectives, implementation strategies, and intended outcomes related to climate adaptation, mitigation, and systemic change. It also included analyzing media reports and gray literature to provide context and connect climate issues to the broader recovery processes. For each case study, we identified the relevant scope of documents and the temporal scope of analysis, given the history, dynamics, and most recent developments around every case.

-

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders involved in the recovery process, including practitioners (e.g., engineers, planners, etc.), policymakers and public workers (e.g., government officials, international aid representatives, etc.), and community leaders (e.g., local representatives, NGO staff, etc.) were used to deepen and validate the analysis based on the documents. Overall, nine interviews were conducted across the case studies: three in Rivne (with one policymaker, one practitioner and one community leader), two in Sicily (one public worker and practitioner), three in Türkiye (two practitioners, along with a direct correspondence with government officials), and two in València (one with a policymaker and one group interview with two community leaders). Our approach to anonymization ensures that interviewees can be associated with the context and ensures that they are referred to in terms of the broader stakeholder groups they represent.

The collected data was analyzed using an abductive approach that involves moving between theory and empirical evidence to systematically and iteratively organize and interpret the data (Timmermans and Tavory, 2022). Inductively, recurring themes, patterns, and contradictions were identified within each case study, revealing insights into how recovery processes are framed and executed. Deductively, the data was analyzed along each of the three spheres of transformation, the stages of the recovery processes, relevance to the dimensions of mitigation and adaptation, as well as resilience and sustainability patterns. Following individual analyses of the cases, cross-cutting insights were extracted through iterative team discussions, providing a basis for extracting broader patterns and the basis for recommendations.

Results: cases of post-disaster recovery

Case 1. Rivne, Ukraine: energy system and full-scale Russian invasion

This case study examines how Rivne navigates energy system disruptions under wartime conditions. Since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, cities across the country have grappled with unprecedented attacks on energy infrastructure. Severely impacted by targeted attacks on energy infrastructure, Rivne's centralized energy model, reliant on the nearby Rivne Nuclear Power Plant and Russian-imported gas, has witnessed recurring attacks on substations, transmission infrastructure, and energy distribution nodes, undermining essential services, industrial production, and the life of the city in broader through frequent electricity outages lasting for hours. Amid this turmoil, the city reaffirmed its climate commitments, joining the EU's NetZeroCities Project1 and intensifying its efforts toward carbon neutrality and energy resilience by 2030. We further outline the changes induced by the war, with a focus on implications for energy systems and in relation to climate mitigation and adaptation.

Political sphere (how): shifting governance logics

Prior to the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022, Rivne's energy governance reflected a predominantly centralized and technocratic model shaped by national regulatory frameworks and vertically integrated, state-owned utilities (UNDP, 2023). Climate considerations were often subordinated to sectoral planning priorities (Guziy, 2025). Still, for more than a decade prior to 2022, the city already had a history of both dedicated climate action and grassroots organization. For example, in 2016, Rivne joined the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, developing its first Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP), later updated in 2018. Although this process was only semi-participatory, it opened the door to cooperation among municipal authorities, local environmental organizations, small businesses, and universities. These developments paralleled Ukraine's EU integration trajectory, which gradually embedded climate objectives into national planning (Government of Ukraine, 2021).

A more profound reorientation emerged after 2022, when Rivne was selected as one of the EU's 112 NetZeroCities Pilot Cities, a milestone that coincided with the onset of full-scale war (EIT, 2023). The escalation of Russian attacks on Ukraine's centralized energy infrastructure exposed the acute vulnerabilities of the existing system and underscored the strategic urgency of decentralized, renewable energy. As a result, the city's current formal commitment to carbon neutrality by 2030 represents both a normative and strategic pivot, aligning Rivne with European green transition ambitions while asserting energy sovereignty as a form of resistance. Current governance efforts include updating the city's development strategy for 2027, revising the SECAP, and drafting a dedicated NetZero Implementation Plan, according to the interviews. These processes feature collaborations between local government, civil society, universities, and international advisors.

While new collaborative models have emerged with the onset of war, the overall governance approach remains fragmented. There is no dedicated coordinating entity in charge of leading and overseeing the decarbonization trajectory that would connect actors and processes on a long-term basis. Leadership is diffused, and responsibilities are spread thinly across various municipal departments and external actors. This results in siloed decision-making, limited institutional learning, and a high dependence on the initiative of individual civil servants or external consultants.

As one civil servant noted:

“…There are many projects happening, but no one is holding the big picture. We work in silos, and when one person leaves, everything pauses.”

The situation is further complicated by unstable financing mechanisms. Although Rivne has been able to implement critical measures through NetZeroCities and other donor-funded programmes, most activities rely on short-term and externally driven project cycles. There is no long-term municipal financing strategy in place to sustain the transition of work beyond the current funding horizon. Another civil servant noted:

“…This process is working now because there is money. But if the money goes away, will anyone still be working on this?”

National-level policy also adds friction. While Rivne's civil society actors advocate for distributed renewables and municipal energy autonomy (Ecoclub Rivne, 2023, 2024), national strategy continues to prioritize centralized energy solutions, including nuclear expansion (Cretti et al., 2024). This creates a disconnect between local climate ambitions and the broader energy policy environment.

Practical sphere (what): adaptive infrastructure

Before the full-scale invasion, local climate initiatives focused largely on upgrading existing systems. For example, in 2021, the city implemented 58 infrastructure projects valued at 50.4 million UAH—mostly targeting maintenance of electricity systems, engineering networks, roofing, and elevators. Although 65% of the funding came from municipal budgets, the remainder was co-financed by residents, reflecting limited but growing community engagement.

The onset of war in 2022 radically altered this context. Repeated attacks on national grid infrastructure led to widespread disruptions, catalyzing emergency energy stabilization measures and a pivot toward decentralization. Under the NetZeroCities pilot, Rivne prioritized investments in solar energy for critical infrastructure—including hospitals and water utilities (Rivne Vodokanal, 2024), and began retrofitting existing infrastructure to meet enhanced energy efficiency standards (State Agency on Energy Efficiency Energy Saving of Ukraine, 2024).

The development of a digital “Municipal Energy Passport” platform, as a part of the NetZeroCities pilot, marked another important step, enabling data-driven planning, real-time monitoring, and better integration of renewable energy systems. Simultaneously, the city launched a series of capacity-building initiatives, training municipal employees, schoolchildren, building managers, and technical professionals in renewable energy technologies and energy management.

One civil servant explains:

“…We are not just creating concepts. We are actually insulating buildings, installing solar collectors and heat pumps… it is not only about saving budgets, but also reducing emissions.”

Despite these advances, the second and third winters of the war were especially cold and challenging. Rolling blackouts and power rationing significantly disrupted daily life. Emergency measures that do not go well with the decarbonization direction, including the acquisition of diesel generators, temporary localized energy storage, and installation of cogeneration units, provided critical short-term relief.

Moreover, several other actions taken by the municipality also might not follow the declared NetZero targets. A civil society actor shared the following observation: “…Some actions go against climate targets—like cutting down trees for parking or buying diesel buses. These contradict what is written in the plans.” Thus, while alternative measures manifested and were supported by diverse actors, including the policy actors, the dominant mode of response and recovery focused on obvious and immediate solutions.

Personal sphere (why): evolving narratives of resilience and sovereignty

Prior to the war, climate discourse in Rivne, where it existed, was primarily couched in terms of cost savings, energy efficiency, and reliability. Public engagement remained modest, while environmental NGOs and youth-led initiatives advocated for broader change.

The invasion catalyzed a significant shift in local narratives. Energy independence became reframed not just as a technical goal but as a symbol of national sovereignty and survival. An interviewee from the municipality puts it: “People may not talk about climate per se, but they understand the value of energy sovereignty.” Citizens' interest in installing solar panels, reducing household consumption, and upgrading insulation has increased. Civil society organizations have amplified this through public education campaigns and participatory tools. Ecoclub, for example, facilitated a city-wide vulnerability assessment and supported citizen engagement with mapping tools and feedback loops.

Local leaders, civil society, and everyday citizens increasingly view renewable energy as a form of resistance—detaching Ukraine's future from fossil-fuel dependency on Russia and enabling greater self-determination. As one city official stated during Rivne EUROFORUM: “Solar panels are our new shields.” This narrative shift is visible in local public events such as Rivne EUROFORUM, which provides spaces for dialogue, education, and vision-building around energy futures and climate neutrality (Rivne City Council, 2025). In broader terms, the narrative shift has focused on the role of energy in resilience and sovereignty, while its implications for climate mitigation and adaptation are yet to be seen over the longer term, as multiple actors representing coupled framing of solutions and rationales continue to compete for funding while the national narrative remains focused around centralization and control over the energy system (Table 2).

Table 2

| Sphere | Observed actions and dynamics | Critical gaps and challenges | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practical | •Solar for critical infrastructure (hospitals, water systems) •Municipal Energy Passport (data-based planning) •Capacity-building for energy professionals Participation in NetZeroCities |

•Continued dependence on diesel generators and nuclear power •No stable financing for green infrastructure •Project-driven initiatives not scaled city-wide |

•Patchy and fragile progress; experimentation not yet institutionalized |

| Political | •Emerging patched hybrid governance (city, civil society, university) •Local decarbonization center Coordination with EU platforms |

•Siloed municipal departments, no formal transition office or team •Local-national misalignment (national focus on nuclear). |

•Governance is adaptive but fragmented; lacks consolidation and durable mandate |

| Personal | •Strong symbolic and survival link between energy autonomy from Russian oil and gas and sovereignty •Civil society (e.g., Ecoclub) is deeply engaged •Rise in public interest in renewables |

•No institutionalized participatory planning for recovery | •Transformative potential exists, but a broader deliberative culture is underdeveloped to lift a collective narrative |

Ukraine case study.

Case 2. Food production systems throughout the drought in Sicily, Italy

This case examines how Sicily navigated intersecting crises in its agricultural and water systems during the 2024 drought emergency. Historically reliant on rain-fed crops and centralized water infrastructure, the region experienced one of the most extreme climate-induced water shortages in Europe (Zachariah et al., 2024). The drought, preceded by decades of declining rainfall and rising temperatures (Aschale et al., 2024; Granata et al., 2024), exposed long-standing vulnerabilities in water governance and agricultural systems. Failures to implement preventive maintenance and structural measures led to reservoir depletion, crop failures exceeding 60%, and rationing for civil use (Catalano, 2025; Duello, 2024). The national government declared a state of emergency in May 2024 (Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri - Dipartimento della Protezione Civile, 2024), appointing extraordinary commissioners for both drought management and the livestock sector (Regione Sicilia, 2024b,c). The crisis was not only climatic but also a governance failure, compounded by demographic decline, youth emigration, and economic fragility (ISTAT, 2024; ANSA, 2024; Arena, 2023).

Political sphere (how): shifting governance under pressure

Sicilian water governance has long been marked by fragmentation and centralization. Before reforms, management relied on regional basins and Ambiti Territoriali Ottimali (ATOs) at the provincial scale (Regione Sicilia, 2024a). The EU Water Framework Directive (2000), transposed through Italian Legislative Decree 152/2006 (Decreto Legislativo 3 Aprile 2006, 2006), created seven national river basin districts, including Sicily, though initially without a single authority. Law 221/2015 later concentrated responsibilities within unified basin authorities (Governo Italiano, 2015), leading to the establishment of the Sicily River Basin Authority (Regione Sicilia, 2020). Wholesale infrastructure was placed under Siciliacque, while local operators managed distribution. Centralized governance was under the authority of the River Basin Authority and the concessionaire.

Planning instruments such as the River Basin District Management Plan, the Water Conservation Plan, and the 2020 Regional Plan to Combat Droughts set out water conservation, infrastructure maintenance, wastewater reuse, and emergency measures. Yet, implementation lagged due to outdated infrastructure, insufficient resources, weak regional–local coordination and limited public engagement. Interviewees emphasized this gap: “Approved plans get put away in a drawer,” one practitioner noted, while another stressed “a persisting problem of political will.” Both observed that “environmental concerns are often an excuse, used to cover the lack of funding,” pointing to incremental cuts in infrastructure budgets for southern regions in favor of “tax reduction” policies (Avvenire, 2012; TPI, 2021).

The 2024 drought prompted extraordinary centralization. Three regional commissioners were appointed, and a multidisciplinary working group of technicians and politicians managed emergency funds (Regione Sicilia, 2024c). As one public worker explained, the emergency was the “winning method to bring everyone around the same table.” Simplified procedures and €20 million in extraordinary funds (later expanded) were released (Regione Sicilia, 2024d). Yet, decisions focused narrowly on maintaining water supply and supporting agriculture. “The aim was to ensure water supply and avoid service interruptions,” a practitioner recalled. This strengthened operational capacity but did not alter governance structures.

After the crisis peak, no permanent inter-institutional mechanisms were created. A public worker urged a “structural return to the ordinary,” stressing the need for long-term investments. Drought governance remained framed as exceptional rather than systemic, closing the window of opportunity for institutional learning. As a result, responses amounted to incremental adaptation, not transformative governance. Academic initiatives hinted at alternatives. In western Sicily, participatory action research brought together farmers and researchers to co-develop agroecological strategies (Conte et al., 2024). Yet these experiments remained disconnected from mainstream policy processes.

Overall, Sicily's political response remained reactive, and emergency driven. Centralized authority and persistent underfunding constrained preventive action, while bottom-up initiatives lacked institutional uptake. The resulting governance landscape reflected complex multi-level interactions and competing national–regional interests, ultimately sidelining local experimentation that could have supported more transformative pathways.

Practical sphere (what): coping, adapting, and incremental innovations

Sicily retains a deep repertoire of traditional agroecological knowledge. Dryland farming systems based on rain-fed cereals, almonds, and olives are central to local identities and practices of place-making (Ferrara et al., 2025). Ancient irrigation techniques, such as stone cisterns and saje, testify to centuries of adaptation to semi-arid conditions (Lofrano et al., 2013). These systems, however, have been increasingly displaced by industrial agriculture, with ecological and cultural costs (Cammarata et al., 2021). More recent innovations—drip irrigation, drought-resistant crops, wastewater reuse—have been promoted as alternatives (Aiello et al., 2013) and were tested through the EU LIFE ADAPT2CLIMA project, while rainwater harvesting remained a key practice, already integrated into building codes in cities like Catania.

At the farm level, adaptive responses emerged, though often guided by markets rather than climate considerations. Some producers have shifted to tropical crops: mango, avocado, banana, papaya, once unthinkable in Mediterranean conditions (Nunn, 2024). While interpreted as innovation, these crops demand high water inputs (Cárceles Rodríguez et al., 2023), potentially worsening scarcity and reinforcing extractive models without regulation. At the community scale, initiatives like Sicilia Integra trained unemployed youth and migrants in agroecology, merging traditional knowledge with regenerative practices (UNDESA, 2019), while the Palma Nana Cooperative offered experiential education in sustainability and rural living (Palma Nana, 2025)

Among the most innovative proposals stand pilot projects or recommendations by universities and the third sector (Cirelli and Sciuto, 2024). A notable example is the research project by Conte et al. (2024) in Western Sicily, where researchers and farmers co-developed agroecological alternatives to industrial agriculture through action research. The advocacy of rainwater harvesting promoted by the interviewer also extends to wastewater reuse, highlighted as a key measure to expand water supply, with proven viability for irrigation, also discussed in existing publications (e.g. Aiello et al., 2013). Yet, as the interviewee emphasized, prior to the drought emergency, such technical proposals were disregarded by institutional actors, underscoring the persistent disconnect between knowledge production and policy implementation.

Governmental crisis measures prioritized continuity over transformation. The national government allocated €20 million, later expanded to €2 billion in infrastructure spending (Regione Sicilia, 2024d). Civil Protection relied on short-term measures: emergency water trucking, reactivated wells, subsidies for farmers, and mobile desalination units deployed only in June 2025 (Regione Sicilia, 2020). As one engineer explained, “The aim was to ensure water supply and avoid service interruptions.” Another acknowledged that while a medium-term investment plan existed, “it was never integrated into institutional mechanisms.” Infrastructural investments thus focused on maintaining existing systems, not redesigning them.

Interviewees confirmed both the sector's slow shift and its constraints. Civil servants stressed the lack of gray infrastructure—dams, reservoirs, maintenance—as the main bottleneck. They also pointed to the political use of climate narratives: “Climate change is turning into an alibi for everyone” and “Environmental concern is often a pretext. The real issue is a lack of funding.” These testimonies reveal how climate discourse can obscure systemic deficits, sustaining reactive rather than structural responses.

Nevertheless, some openings emerged. Universities demonstrated that treated wastewater reuse could meet up to 15% of agricultural demand. As the interviewed practitioner observed, “The agricultural sector became more accepting of treated wastewater reuse after the drought.” Yet uptake remains contingent on investment, public acceptance, and political commitment. Overall, practical responses to the drought reinforced absorptive capacity—the ability to buffer shocks without learning or changing—rather than triggering systemic innovation. Academia and civil society have advanced viable pathways, but without institutional integration, their transformative potential remains marginal.

Personal sphere (why): changing perceptions and frustrated agency

In Sicily, where “water scarcity is a historical issue,” as noted by the practitioner interviewed, communities have long adapted to prolonged drought through inherited practices, such as underground rainwater cisterns in ancient dwellings (Lofrano et al., 2013). These forms of Indigenous Knowledge highlight the enduring role of agricultural heritage—deeply tied to identity—in shaping adaptive practices (Conte et al., 2024).

The 2024 drought, however, was both a material and symbolic rupture. Despite farmers' embedded knowledge, governmental responses were technocratic and top-down, marginalizing local actors. Farmers were forced to abandon harvests and cull livestock (Duello, 2024), turning the crisis into one that undermined livelihoods and dignity as much as material production. “Citizens became more aware,” the practitioner stated, noting that the drought drew “greater media attention.” Yet no genuine community-level dialogue emerged, and trust eroded as funds targeted only short-term relief. These reinforced perceptions of a detached government, while opportunities to mobilize community agency were left untapped.

Some cultural shifts nevertheless appeared. Farmers began “asking for support to implement water-harvesting solutions,” as was mentioned by the interviewed practitioner, suggesting a willingness to engage in adaptive change. Citizens increasingly recognized drought as systemic rather than exceptional. The crisis thus exposed the fragility of existing governance, while simultaneously sowing seeds of transformation through revived Indigenous Knowledge and local resilience practices.

Public institutions continued to frame the drought in narrow technical terms, emphasizing immediate water logistics and emergency management over long-term social and ecological transformation. In some cases, climate change discourse was used to obscure structural neglect. As one civil servant remarked, “Climate change is turning into an alibi for everyone.” This instrumentalization of climate narratives served to justify top-down decisions and deflect attention from governance failures, further undermining trust and civic engagement.

Yet, the drought also acted as a catalyst for rethinking. Among certain segments of the population—particularly younger generations and community-rooted actors—a shift in consciousness began to take shape. Local initiatives emerged that enacted small-scale but meaningful transitions: agroecological cooperatives, permaculture gardens, and informal water-sharing networks (Conte et al., 2024). For example, in places like the Belice Valley, grassroots assemblies brought together farmers, hydrologists, artists, and students to reframe water not as a commodity, but as a common good (Centro di Ricerche Economiche e Sociali del Meridione, 2025) Though informal and lacking institutional backing, these gatherings embodied a nascent cultural transformation, one in which drought is reimagined not solely as a technical problem, but as a political and ethical challenge that demands collective reorientation.

Grassroots initiatives such as Coltivare il Futuro increasingly invoked the language of territorial sovereignty, environmental stewardship, and regenerative futures (Palmeri and Bissanti, 2025). These emerging narratives argue that climate responses must be rooted in historical memory, local knowledge systems, and the agency of those directly affected (Nanni et al., 2021). In contexts like Sicily—where rural abandonment and demographic decline converge with ecological precarity—such actors insist that recovery cannot be reduced to material infrastructure alone.

Together, these shifts signal the early stages of a cultural metamorphosis. While not yet dominant in the collective narrative, they open space for alternative imaginaries of recovery—ones that foreground relational, place-based, and intergenerational forms of resilience (Table 3).

Table 3

| Sphere | Observed actions and dynamics | Critical gaps and challenges | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practical | •Emergency measures: subsidies, water trucks, reactivation of desalination plants •Limited experimentation with agroecology and irrigation upgrades |

•Fragmented implementation •No scale-up of sustainable innovations •No systemic water governance reform |

•Short-term relief prioritized over structural change |

| Political | •Crisis governance is centralized in regional authorities •Some EU funding mechanisms triggered •Disconnected rural planning and agricultural policy |

•Absence of coordination across water, agriculture, and climate sectors •No cross-level or participatory governance structure |

•Governance remains reactive and siloed |

| Personal | •Rising awareness among farmers about climate risks •Local cooperatives and activist networks engaged in resilience and climate mitigation discourses |

•Farmers' experiential knowledge marginalized •Lack of inclusive planning processes •No mechanisms for value-driven dialogue |

•Potential exists, but not institutionally activated |

Italy case study.

Case 3. Post-earthquake reconstruction in Türkiye: barriers and pathways for sustainable building practices

This case study traces how Southeastern Türkiye has approached systemic recovery of its construction sector following the 2023 earthquakes, amid compounding social and political pressures. In February 2023, devastating earthquakes in southern Türkiye resulted in over 55,000 fatalities and severe damage or destruction to approximately 280,000 buildings across 11 provinces, displacing around 1.5 million people (Presidency of Strategy Budget, 2023). Cities like Hatay and Kahramanmaraş experienced extensive damage, with entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble under harsh winter conditions (Çetin et al., 2023). The Turkish government responded swiftly with a massive reconstruction program, pledging to build approximately 650,000 new homes. By early 2024, around 319,000 units were committed, with over 200,000 completed and approximately 120,000 under construction. However, this rapid rebuilding effort, managed by the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change (MoEUCC) and the Housing Development Administration of the Republic of Türkiye (TOKI), prioritized speed and earthquake safety, largely neglecting the integration of sustainability practices crucial for Türkiye's long-term climate change adaptation and mitigation goals. Despite Türkiye's stated commitments to climate-responsive policies—including a 2053 net-zero carbon target, sustainable energy transitions, and green building practices—the reconstruction process remained largely disconnected from these sustainability objectives.

Political sphere: centralized governance, fragmented climate integration

Türkiye historically responds to large-scale disasters through centralized governance structures. These structures are defined by regulations such as Law No. 7269 (Law on Measures and Assistance Regarding Disasters Affecting Public Life) and Law No. 6306 (Law on Transformation of Areas Under Disaster Risk). These laws grant substantial authority to national institutions such as MoEUCC, TOKI, and the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (AFAD), significantly limiting local stakeholders and community participation (Özdogan et al., 2024).

During the 2023 earthquake recovery, this top-down institutional legacy was reinforced rather than reformed. Regional and municipal actors were sidelined, and the decision-making process remained centralized in the hands of governmental bodies and political appointees (Resmî Gazete, 2023). In this governance context, climate considerations and participatory planning processes were left largely at the discretion of central authorities. The urgency of recovery was framed primarily through the lens of rapid housing production, leaving little room for deliberation or local input (Oguz and Hansu, 2025). In line with that, the Turkish government expanded expropriation powers to facilitate swift reconstruction, often favoring peripheral land development and urban sprawl over sustainable in-situ rebuilding strategies (Çakir, 2023). Although new buildings now meet improved seismic standards, they generally lack integration of climate-responsive principles.

However, a more sustainable direction is not absent. Türkiye's national green building certification system, Yeşil Bina Sertifikasi (YeS-TR), offers a potential avenue to align reconstruction with climate mitigation and resilience goals. Developed by MoEUCC, YeS-TR is a comprehensive framework that incorporates multiple modules—such as integrated design, building materials, energy and water efficiency, indoor environmental quality, and innovation—drawing on both international standards and local environmental conditions (ÇSB, 2020; Umumi Hayata Müessir Afetler Dolayisiyle Alinacak Tedbirlerle Yapilacak Yardimlara Dair Kanun, 1959).

Although YeS-TR certification remains voluntary today, it will become mandatory for new public buildings exceeding 10,000 square meters starting in January 2026 (ÇSB, 2024). According to our interviews, one of the certification's lead developers emphasized its value in the post-disaster context:

“YeS-TR provides feasible and grounded recommendations suitable for Türkiye's unique environmental and socio-economic conditions.”

Our correspondence with MoEUCC confirmed this growing institutional interest. A ministry representative noted:

“the certification's initial implementation in public building processes would substantially elevate awareness, technical expertise, and practical experience within the construction industry, eventually supporting voluntary uptake in private construction due to proven economic and environmental benefits”

Of particular relevance is YeS-TR's Adaptation, Conservation, and Ecology (AKE) module, which uniquely includes a dedicated disaster resilience component—something rarely found in other green building systems. This module encourages comprehensive disaster risk assessments, sustainable site selection, and climate-adaptive land use planning. As the ministry noted:

“The ‘Disaster Resilience' theme within the AKE module constitutes a critical component of sustainable site selection and land-use planning in Türkiye, given the country's frequent exposure to various disasters. It has no equivalent in international certification systems, making it a unique and strong feature of our national green certification…. This module significantly contributes to national disaster mitigation efforts. It aims to advance disaster awareness and to demonstrate that disaster impacts can effectively be minimized through proactive measures.”

Despite these promising developments, YeS-TR has not yet been systematically incorporated into post-earthquake reconstruction across affected provinces. Institutional uptake remains slow, and without a clear regulatory push, its impact may remain marginal. Moreover, the centralized governance structure continues to limit the scope of local innovation and civic agency in shaping a transformative recovery.

In sum, Türkiye's post-disaster governance reflects a deep institutional inertia shaped by decades of centralization. Yet, embedded within this landscape are tools—like YeS-TR—that hold potential for more inclusive, climate-aligned reconstruction.

Practical sphere: potentials for climate- responsive innovations

Despite the existence of science-based frameworks such as the YeS-TR green building certification and the availability of climate-resilient design principles, practical uptake remained minimal. While YeS-TR has been promoted for public buildings and includes a module on disaster resilience, most new constructions conformed to traditional, cost and speed driven models with limited attention to energy efficiency, sustainable materials, or land-use adaptation. A pilot energy efficient design initiative in Hatay, for instance, demonstrated that incorporating renewable energy and passive design strategies could significantly reduce energy demand (Saleh et al., 2024), yet such examples have not been scaled or mainstreamed.

Instead, reconstruction was dominated by a highly centralized and opaque governance structure. Tenders were often awarded to large, politically affiliated companies through non-transparent processes (Toker, 2023). In the initial weeks following the earthquake, President Erdogan's promises to complete all disaster housing within 1 year as part of his local election campaign (Erem 2024) received widespread media attention, raising public expectations. Built environment professionals frequently emphasized that this timeline was unrealistic and would likely lead to long-term environmental, economic, and social problems.

Contractor-driven practices also shaped the urban form of recovery. Reconstruction sites were frequently located on the periphery of affected cities, as guided by the current laws and regulations, requiring the expropriation of agricultural lands, forests, and even olive groves (Bianet, 2023). The demolition of undamaged buildings within designated reserve areas—including the building of the Chamber of Architects Kahramanmaraş Branch, despite its structurally intact condition— alongside the adoption of rapid and simplified construction practices concentrated on urban peripheries instead of in-situ reconstruction, has been significantly criticized by built environment specialists (Batuman, 2024). Concerns have been raised that such practices could lead to adverse environmental impacts, increased infrastructure costs, and enduring social issues in the long term. In many cases, retrofitting damaged but salvageable buildings—a more cost-effective and environmentally responsible solution, were dismissed in favor of demolition and new construction. Yet engineers estimated that retrofitting could have secured thousands of structures at a fraction of the cost and environmental footprint of rebuilding (Aktas et al., 2024).

Furthermore, while seismic codes have improved since 2018, weak enforcement remains a persistent challenge. Even before the 2023 disaster, construction amnesties had allowed thousands of non-compliant buildings to be legalized, undermining the credibility of regulatory systems (TMMOB, 2018). Against this backdrop, civil society and academic initiatives advocating for ecologically sensitive reconstruction faced significant challenges in gaining traction. Particularly in Hatay, the expropriation of agricultural lands and olive groves for reconstruction purposes was met with strong opposition from local communities. Robust civic initiatives and collective solidarity emerged, explicitly demanding a more ecological reconstruction approach, as exemplified by grassroots mobilizations such as the Dikmece resistance (Arti Gerçek, 2023).

Personal sphere: dominant narratives, urgent needs, and shifting perspectives

Understanding public perceptions and attitudes toward climate change adaptation and mitigation in post-disaster reconstruction is critical for achieving effective recovery outcomes. In disaster contexts, prevailing narratives and prior exposure to climate-responsive solutions significantly shape community priorities, often creating tension between immediate relief and long-term sustainability goals.

Following the 2023 earthquakes, communities experiencing severe hardships in temporary housing, such as tents and container settlements, understandably prioritized immediate access to permanent housing solutions. This priority was heightened by the government's pledge to deliver disaster housing within 1 year, which elevated societal expectations for rapid reconstruction. Consequently, proposals emphasizing sustainability, such as green building standards, climate-adaptive designs, or participatory planning processes, were often perceived as potential delays rather than beneficial enhancements.

The government's framing of the recovery process as an emergency, while undoubtedly justified by the urgent conditions, further restricted opportunities for meaningful public deliberation and democratic engagement, which might take longer than standardized housing projects. By predominantly emphasizing speed, this approach overlooked equally critical factors such as sustainability, inclusivity, and local participation—elements that inherently require more extended timelines but are vital to ensuring durable, resilient outcomes beyond immediate relief.

Additionally, the unprecedented scale of destruction strengthened the perception among local stakeholders that only centralized governmental intervention could adequately manage recovery efforts. Field interviews with municipal authorities in affected cities explicitly illustrate this perspective. A representative from one district in Hatay noted: “The current reconstruction approach excludes local ideas and priorities; however, relying solely on local governments and communities would also be insufficient for managing recovery efforts following a disaster of this magnitude. Central government involvement remains essential, but it must be based on genuine cooperation.” This observation highlights a recurring practical tension: effective recovery requires balancing central oversight, necessary due to resource and capacity limitations, with locally driven initiatives.

Nevertheless, evidence indicates a gradual shift in public perspectives toward sustainability, driven by strategic interventions and practical demonstrations. Current public projects employing the YeS-TR certification illustrate the tangible practicality and long-term advantages of systematically integrating sustainable construction methodologies, provided they receive consistent political backing (ÇSB, 2023). Studies clearly demonstrate benefits, including improved environmental performance, lasting economic savings, and greater resilience in the built environment (Kartal et al., 2020) Simultaneously, civil society organizations, NGOs, and built environment professionals increasingly advocate for environmentally responsible approaches. Their advocacy reflects growing public awareness about environmental degradation and concerns regarding the expropriation of agricultural lands, forests, and olive groves for new settlements.

Addressing the existing tensions requires clearly demonstrating the tangible practicality and long-term advantages of sustainable reconstruction. Yet, achieving broad societal acceptance for sustainable reconstruction necessitates continuous educational initiatives, transparent governance practices, and meaningful reforms within the construction industry. By strategically leveraging existing scientific knowledge and technical expertise, it is possible to enhance both public support and practical adoption of sustainability measures. Ultimately, such efforts hold the potential to transform Türkiye's post-earthquake reconstruction into an internationally exemplary model of climate-responsive recovery, embedding resilience within governance frameworks, construction practices, and broader societal attitudes (Table 4).

Table 4

| Sphere | Observed actions and dynamics | Critical gaps and challenges | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political | •Centralized recovery led by MoEUCC, TOKI, AFAD—Local and civil actors sidelined—Contracts favor political allies | •Exclusion of democratic input •Weak accountability and transparency •Climate goals subordinated to urgency |

•Governance is shaped by top-down control and opacity |

| Practical | •Rapid housing delivery prioritized •Emphasis on earthquake safety •Public projects with YeS-TR certification system -new builds on rural land |

•Sustainability marginal or symbolic •No mandatory green standards •Urban sprawl, missed retrofitting options |

•Speed-driven reconstruction hinders climate integration |

| Personal | •Public demand for fast shelter •Low climate awareness and demand for sustainable solutions |

•Green building seen as a potential delay •Social and cultural needs ignored—Emerging awareness among youth and NGOs |

•Dominant narratives limit change, but cracks emerged |

Türkiye case study.

Case 4. València: DANA flooding and the struggle for climate-conscious mobility transformation

On October 29, 2024, the València metropolitan area was struck by a catastrophic DANA (isolated high-altitude depression), unleashing 771 l/m2 in 24 h, of which 185 were accumulated in just one hour, a record for Spain in that period (AEMET, 2024). The floods claimed more than 232 lives representing 70% of all deaths linked to torrential rains in Europe throughout 2024, submerged entire neighborhoods, and destroyed over 120,000 vehicles (La Moncloa, 2024). Many fatalities occurred in underground garages and during evening commutes, with people trapped in cars or swept away by torrents. The event underscored how València's car-dependent infrastructure not only failed under extreme conditions but actively amplified vulnerability. This case study therefore investigates whether the disaster would reinforce the status quo or catalyze systemic transformation in urban mobility and climate resilience.

Political sphere: fragmented governance meets public pressure

Prior to the disaster, València's mobility governance reflected chronic fragmentation and a reliance on reactive, sectoral planning. The dismantling of the city's integrated emergency coordination unit in 2023 delayed critical alerts and exposed institutional unpreparedness. Despite policy frameworks promoting climate action—such as EU directives, Low Emission Zone (LEZ) plans, and a Metropolitan Mobility Plan focused on public transport expansion, deterrent parking, and Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platforms—car-centric development remained dominant. At the time of the flood, approximately 60% of daily commutes in the region were made by private vehicles (GVA, 2022).

These dynamics unfolded within a broader governance landscape marked by transition. In recent years, València has embraced a progressive, mission-oriented approach through its participation in the EU Cities Mission and the formation of multi-actor partnerships to advance climate neutrality, experimentation, and participatory governance (Blanes et al., 2024; Udovyk et al., 2025a,b). However, following the 2023 municipal elections, this trajectory began to shift. The new political leadership has reoriented priorities toward a more technocratic governance model, emphasizing digital and technological innovation over deliberative, systemic transition—highlighting how political change can redefine the contours of urban climate governance (Blanes et al., 2024; Udovyk et al., 2025a,b).

The flood spurred rapid, though uneven, policy responses. The Spanish government allocated over €1 billion for transport recovery, including €465 million through the Plan Reinicia Auto for vehicle replacement (Real Decreto-Ley 8/2024, de 28 de Noviembre, Por El Que Se Adoptan Medidas Urgentes Relativas al Plan REINICIA AUTO+, Pub. L. No. 8/2024, 2024) Simultaneously, the regional government passed the Climate-Resilient Mobility Act, banning construction in floodplains and mandating flood risk assessments for new infrastructure.

Citizen science and advocacy played a significant role. Post-flood maps developed by the Universitat de València, combining satellite and crowdsourced data, were cited in parliamentary debates. There was a demand for elevated bike lanes and resilient transit hubs, calling attention to the systemic risks of car-centered planning. As one activist noted: “This wasn't just weather—it was policy failure on wheels.”

Yet, the reforms coexisted with contradictions. National subsidies promoted vehicle renewal over public transit, while conservative coalitions (PP–Vox) framed green reforms as “economic sabotage.” Governance thus oscillated between transformative ambition and regime-preserving investments, limiting the coherence of post-disaster strategy. Crucially, what remained absent was a shared governance space where diverse stakeholders (including citizens, local governments, businesses, and civil society) could co-create long-term recovery pathways to address mobility recovery. Although various expert groups and intergovernmental committees convened to address aspects of recovery, these efforts operated in silos and lacked mechanisms for inclusive deliberation, vision-building, or systemic learning. This absence limited the capacity for reflexive, anticipatory governance and hindered the emergence of a cohesive transformation strategy.

Practical sphere: cars as catalysts of crisis, mobility niches under pressure

The flood transformed the city's dominant mode of transport—cars—into sources of chaos and death. Residents drowned attempting to reach or retrieve vehicles; streets clogged with floating cars impeded emergency response. “We found seven bodies in a garage where they were trying to save their cars,” said a firefighter. “The water just came too fast.” In contrast, cycling and walking became vital mobility alternatives. The Turia River footbridge emerged as a lifeline—renamed the “Solidarity Bridge” by residents—when all other routes were impassable. Informal walking routes and pre-existing bike lanes played unexpected roles in maintaining connectivity.

Prior to the flood, València piloted several niche innovations: bike-sharing schemes, electric scooters, and smart mobility zones in selected districts. Reports from Las Naves, the city's innovation agency, documented modest shifts toward non-motorized trips. However, these innovations remained siloed, underfunded, and insufficiently scaled. Post-flood investment prioritized road and drainage repairs, while alternative mobility received rhetorical support but limited resources.

“When there was pure mud on the streets, cycling, public transport, and citizen collaboration gained weight. I once took the train, which was a shuttle bus, and for example, I know other people who organized themselves with the few people who had vehicles. It was the time of the post, when we still hadn't recovered… but now it's the time of the avalanche of vehicles. Everyone has restocked their vehicle, and people I know who had two and three vehicles have completely restocked their vehicles.”

The continued dominance of car-based solutions—particularly through subsidies—suggests a missed opportunity to realign infrastructure with climate-resilient principles. “We're rebuilding the old system with newer cars,” commented one mobility planner. “It's reconstruction without transformation.” In fact, one cyclist activist who played a key role delivering bikes to the population in the first months of the crisis, pledged that “the first thing that the Regional Government did when they re-opened the metro service, we to forbid the entrance of bikes in the trains,” which meant a significant step back from previous multi-mode sustainable mobility policies. In fact, the only innovative solution that seems to prevail is the building of high-rise parking spaces on the edges of towns to empty the streets of cars through pedestrianization and green spaces. This is expected to contribute to increased security in case of flooding and to urban space quality.

Personal sphere: from complacency to cognitive dissonance

Before the disaster, car ownership in València was deeply normalized—viewed as a necessity for commuting, comfort, and status. Confidence in flood defenses, combined with the convenience of driving, created a sense of safety that proved fatally misleading. Climate risks were seen as distant, and mobility choices were rarely linked to environmental consequences.

The DANA disaster triggered a deep emotional rupture. Cars, once symbols of security, became associated with death, helplessness, and debris. “They floated like toys and killed people,” said one survivor. “We'll never look at parking garages the same again.”

Public discourse momentarily shifted. Solidarity narratives circulated widely, centered on shared trauma and the use of bicycles or footpaths to navigate the submerged city. Yet, this collective awareness did not translate into widespread behavioral or cultural change. A survey by the Polytechnic University of València found that the most frequently cited recovery priority was car replacement—not public transport or climate-safe infrastructure.

“It was surreal,” recalled one resident. “We were driving shiny new subsidized electric cars through streets full of mud, collapsed houses, and dead gardens. Everything was broken—but we still needed to drive.”

This illustrates a fundamental disjuncture between emotional awareness and structural alternatives. Without reliable public transit or participatory platforms for reimagining mobility futures, even a rupture of this scale failed to anchor a transformation narrative (Table 5).

Table 5

| Sphere | Observed actions and dynamics | Critical gaps and challenges | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practical | •Mobility reforms launched (Climate-Resilient Mobility Act, LEZs, active mobility plans) •Some EU conditionalities used •Grassroots initiatives mobilization |

•Car replacement subsidies (Plan Reinicia Auto) contradicted climate goals •Infrastructure still prioritizes private car use |

•Climate-smart measures are emerging but inconsistently applied and undermined by legacy systems |

| Political | •Climate-mobility integration initiated through new legislation •Some cross-sector governance experimentation at the municipal level •Strong technical leadership |

•Political fragmentation: tensions between progressive agendas and car-centric coalitions •No functioning transition arena |

•Politically contested; institutional innovation exists but lacks coherence and enforcement |

| Personal | •Rising public support for bike infrastructure, resilience awareness | •Car dependency is still dominant and is the main cultural narrative | •High awareness and will to change in some groups; broader value shift still shallow and contested |

Spain case study.

Analysis

Analysis across cases along the three spheres of transformation

Political sphere: governance without anticipation

As for the cases, in response to disruptions, the governance mode was primarily reactive and siloed. Türkiye exemplified centralized recovery, with national agencies excluding municipalities from planning processes and bypassing public accountability. Italy's drought response was fragmented across agriculture, water, and climate departments, without a cross-sector transition mandate. Even in relatively decentralized Spain, strategic contradictions impeded structural transition in mobility.

Where new institutional forms emerged, however, recovery showed signs of transformative potential. Rivne developed a civic–academic–municipal alliance, supported by EU climate frameworks, enabling the city to adopt a long-term energy transition pathway. This case highlights how multi-scalar coalitions and hybrid governance configurations provide the scaffolding for experimentation and adaptation (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2013; Hölscher et al., 2019). In more constrained settings, like Türkiye and Italy, civil society coalitions and rural networks also pursued alternative recovery logics, albeit without formal mandates or sustained funding.

These examples highlight a key insight from transition theory: transformative change requires not only better policy, but new arenas for policy formation, where participatory visioning and institutional learning can co-evolve (Frantzeskaki et al., 2012).

Practical sphere: infrastructure without imagination

Across all cases, recovery actions were dominated by a technical, infrastructure-focused rationality centered on short-term continuity rather than long-term system change. In Türkiye, centralized recovery efforts in post-earthquake housing reconstruction adhered to earthquake design standards but neglected environmental sustainability and participatory design, thus disregarding potential long-term impacts. Similarly, Sicily's drought response relied on desalination infrastructure, neglecting regenerative land use and water management practices. Ukraine's response to energy infrastructure damage involved mass procurement of diesel generators to ensure winter survival—reinforcing fossil fuel dependence rather than accelerating a renewable transition. In València, the paradox of promoting bike lanes while simultaneously subsidizing car replacement (via Plan Reinicia Auto) reflects a lack of internal policy coherence and reveals the limitations of technocratic adaptation under conflicting agendas.

Yet even in cases with advanced pilots, such as agroecological initiatives in Sicily or climate-friendly solutions in Türkiye, transformative potential remained under-realized due to the absence of institutional mechanisms to consolidate learning, scale innovation, or formalize change, factors considered crucial for advancing transition agendas (Loorbach et al., 2017; Stirling, 2014). Without political support or budgetary anchoring, these initiatives functioned more as symbolic signals than structural shifts.

Personal sphere: recovery without narrative change

Across all four cases, the personal sphere—the realm of values, identity, emotion, and meaning—emerged as the most underdeveloped yet foundational dimension of recovery. While infrastructure was rebuilt and policies reformed, the deeper symbolic and cultural ruptures caused by disaster were almost unacknowledged. Recovery governance dominated by technocratic scripts marginalized experiential knowledge, erased trauma, and foreclosed opportunities for collective sense-making.

This tendency manifested in diverse ways across the cases. In Türkiye, the recovery process was framed around urgency, positioning centralized reconstruction as the quickest solution and influencing perceptions of alternative approaches as unnecessary obstacles causing delays. In Sicily, technical water management solutions sidelined long-standing local ecological knowledge, and climate change was framed to be the “one to be blamed”. In València, mobility planning remained embedded in a depoliticized, expert-driven discourse, detached from lived experience. Across these contexts, there were few, if any, institutional mechanisms for narrative renegotiation, public mourning, or imaginative reorientation—practices essential for rebuilding not just infrastructure but meaning.

As transformation scholars argue, structural and technological shifts remain fragile and performative unless they are accompanied by shifts in culture, identity, and affect (Fazey et al., 2018; Head, 2022). As Brown and Westaway (2011) emphasize, affect, and memory are not peripheral to climate governance—they are constitutive of it. Such shifts, however, are hard to predict and steer. Narrative changes across cases could be observed if linked to the necessity and poignant inexpedience of dominant storylines. In Rivne, for instance, the growth in decentralized energy was catalyzed not only by damaged infrastructure, but by a broader reframing of energy as a question of sovereignty and survival from the Russian attacks—a narrative that galvanized civic participation and legitimized alternative energy system configurations.