Abstract

Climate change is driving cities to transition toward more sustainable urban systems, often implementing these transitions through spatial interventions. However, without a deliberate focus on spatial justice, such climate initiatives risk exacerbating existing socio-spatial inequalities, leading to issues such as green gentrification and maladaptation, which affect vulnerable populations the most. Participatory practices have the potential to foster just transitions, yet they are not well integrated into planning and design processes and are insufficiently linked to spatial justice. This paper introduces a framework that integrates participatory approaches into a typical planning and design cycle through a spatial justice perspective. The framework is applied to eight cases in various geographical contexts, encompassing a range of practices from participatory planning workshops to the development of digital participation tools. Our findings suggest that the framework enables both researchers and practitioners to adopt a more holistic approach to participation in planning and design. Furthermore, we identify key enablers, barriers, and lessons learned from these cases, offering insights that can inform urban practitioners, policymakers, and researchers in advancing spatial justice through participatory planning. Ultimately, this study contributes to enabling just urban transitions by providing a structured approach to embedding spatial justice in participatory planning and design.

1 Introduction

Facing more frequent and severe climate impacts, cities worldwide are pursuing ambitious goals across multiple sectors to become more sustainable, resilient, and climate neutral. These ambitions are usually encapsulated in strategic plans and entail a range of interventions that aim to reduce carbon emissions associated with urban activities and adapt the built environment to a changing climate (Krellenberg et al., 2019; Malekpour et al., 2015; Morrissey et al., 2018). Examples of such interventions include the promotion of sustainable transportation (Hrelja et al., 2015), implementation of green infrastructure (Barker et al., 2024), retrofitting of existing housing stock (Liyanage et al., 2024), transition to renewable energy sources (Kraaijvanger et al., 2023), and deployment of smart buildings (Spiliotis et al., 2020).

In highly complex and unequal spaces such as the city (Nijman and Wei, 2020), urban climate interventions have a profound impact on the livelihoods of individuals and communities, from daily disruptions to long-term infrastructure lock-ins that perpetuate inequality across the city (Kraaijvanger et al., 2023; Sundaram et al., 2024). Inequalities also emerge when climate interventions fail to achieve their intended goals and/or create adverse or unintended effects (Dodman et al., 2022). The negative consequences of climate adaptation measures are termed ‘maladaptation’ and refer to the “result of an intentional adaptation policy or measure directly increasing vulnerability for the targeted and/or external actor(s), and/or eroding preconditions for sustainable development by indirectly increasing society’s vulnerability” (Juhola et al., 2016, p. 139). Examining maladaptation from an urban perspective reveals, for example, that single-sectoral projects such as greening can lead to gentrification and the displacement of certain social groups and loss of collective identity (Anguelovski et al., 2019; Shaw and Hagemans, 2015).

In response to increasing urban inequalities and concerns about maladaptation, many scholars and international organisations have highlighted the need for justice considerations in sustainability and climate neutrality transitions (Avelino et al., 2024). Spatial planning, in particular, has an important role in preventing maladaptation, addressing existing and preventing future inequalities (New et al., 2022). Here, the concept of spatial justice appears as a suitable lens for understanding how spatial planning reinforces or creates new socio-spatial inequalities in urban areas (Soja, 2013). A spatial justice perspective on sustainability transitions calls for a critical reflection on how the burdens and benefits of transitions are spatially distributed among communities, how transition decision-making processes occur and who is involved, and how transition interventions contribute to the further marginalisation of specific social groups and communities. These attributes can be summarised in three dimensions of spatial justice: distributive, procedural and recognition, respectively (Rocco et al., 2024a; Rocco, n.d.).

Debates about spatial justice are often accompanied by discussions on public participation (Dadashpoor and Dehghan, 2025), usually in connection with recognitional and procedural dimensions. Participation enables public institutions to understand the diverse needs and aspirations of diverse groups, serving as a conduit for capturing contextual dynamics and local knowledge (Gonçalves et al., 2024; Herzog et al., 2024). Such contextual understanding helps to address the challenges and conflicts that emerge with the deployment of spatial interventions in urban areas (Herzog et al., 2024). Participation comes in various types, shapes and forms, from conventional formats like public hearings to interactive websites and working groups and more radical forms of radical democracy, such as participatory budgeting, liquid democracy, citizen assemblies, mini publics and immersive experiences (Baiocchi and Ganuza, 2014; Cammaerts, 2015; Dane et al., 2024; Farrell et al., 2023; Hofer and Kaufmann, 2023). More recently, the emergence of digital technologies has changed public participation, transitioning from traditional methods to digital platforms (Gonçalves et al., 2024; Kleinhans et al., 2022). Digital public participation tools and platforms have the potential to streamline stakeholder involvement, overcoming constraints of time, space, and participation capacity associated with traditional methods (Gonçalves et al., 2024; Kleinhans et al., 2022).

While participatory practices generally contribute to a sense of community ownership, commitment, responsibility, and social cohesion within communities and among stakeholders (Ellery and Ellery, 2019; Lachapelle, 2008; Qi et al., 2024; Suomalainen et al., 2022; Talò et al., 2014; Tassinari et al., 2023), several challenges remain. These include limited and unrepresentative participation, insufficient citizen/community influence on decisions, lack of clarity in how citizen contributions are used in final decisions, disparities in contextual and topical knowledge levels among stakeholders, repetition of participatory processes with the same socio-cultural groups leading to fatigue, among others (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2020; Fung, 2015; Gonçalves et al., 2024; Pateman et al., 2021). The lack of political will and resistance from diverse actors has also been observed as a barrier to participation (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2020; Gonçalves et al., 2024). Similar challenges and criticism accompany digital participation. In both in-person and digital versions, participatory practices require investments in time, capacity/training and management (Egli et al., 2020; Michail et al., 2025) that may compromise efforts to deliver inclusive practices. Moreover, issues such as audience size, sampling methods, bias, and data accuracy affect the quantity and quality of digital engagement (Brown and Kyttä, 2014); the digital divide and dynamics pertaining to specific socio-political contexts that influence how technology is used further complicate the implementation of digital participation processes (Ellul et al., 2013; Nold and Francis, 2017; Robinson et al., 2015; Selwyn, 2004; van Deursen and van Dijk, 2014).

Although various innovative tools and methods have been developed to facilitate and improve citizen and community engagement (Geekiyanage et al., 2021), these efforts remain largely disconnected from urban planning and design processes in practice, as participation is frequently reduced to a tokenistic exercise rather than being meaningfully embedded in decision-making (Kiss et al., 2022; Monno and Khakee, 2012; Yazar et al., 2025). Reasons for this disconnection can be found in the lack of implementation capacity, the lack of integration of participatory processes in governance arrangements, and the limitations of participatory tools (Ballatore et al., 2020; Falco and Kleinhans, 2018; Gonçalves et al., 2024; Kleinhans et al., 2022). With the increasing availability and diversity of new participatory methods and toolkits, implementation becomes more complex and challenging, as implementers may lack a clear understanding of when, where, how, and for whom to use different methods (Ataman et al., 2025). This may lead to paralysis and resistance to innovation, reliance on conventional participatory approaches even if they fail to be inclusive or effective, and a “one-size-fits-all mentality” that overlooks the complexity of participatory processes (Goncalves et al., 2025; Gonçalves et al., 2024). These trends are problematic because different planning and design activities require tailored tools and methods for addressing not only specific local problems but also the needs of people who will use them (both facilitators and participants) (Goncalves et al., 2025).

Literature also indicates that the relationship between participatory processes and spatial justice outcomes remains underexplored and insufficient. The presence of participatory mechanisms does not automatically guarantee more equitable spatial outcomes, as these processes are often poorly integrated into decision-making or constrained by existing power structures (Monno and Khakee, 2012). While participation and spatial justice are clearly related terms (Dadashpoor and Dehghan, 2025), a framework that supports the pursuit of spatial justice in participatory planning remains lacking. We argue that, without a deliberate emphasis on spatial justice in participatory planning and design processes, opportunities for justice-informed action are missed.

This paper has a twofold aim: (1) to provide a conceptual framework to embed participatory practices in urban planning processes through a spatial justice lens, and (2) to provide insights from practice on barriers and enablers for the development and implementation of participatory practices to foster spatial justice. For that, we first develop a framework grounded in spatial justice theory and planning literature, which we then use to analyse eight cases of participatory practices. We consider cases that engage citizens as well as other local stakeholders in urban strategic planning. These cases include participatory workshops, storytelling, and digital engagement tools, among others. All cases are associated Horizon Europe UP2030 project (2023–2025), which leverages urban planning and design and inclusive participation to support socio-technical transitions required toward climate neutrality.

Combining key concepts from literature with empirical data from eight cases, the paper provides both a transferable framework to understand how participatory practices can foster spatial justice as well as practical insights to support both researchers and practitioners in adopting a more holistic approach to spatial justice through participatory planning. Ultimately, the study contributes to enabling just urban transitions by providing a structured approach to embedding spatial justice in participatory strategic planning.

In the next sections, the literature background and the conceptual framework proposed in the paper is described (Section 2 and 3), followed by the methodology and the eight cases in the paper (Section 4). Next, the results are presented and discussed (Sections 5 and 6, respectively). Finally, concluding thoughts and directions for future work are provided (Section 7).

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Planning paradigms

Planning thought has evolved through a sequence of overlapping paradigms, each shaped by changing socio-political conditions, epistemological assumptions, and institutional contexts. In the Western post-war period, the dominant paradigm was the rational-comprehensive model, closely associated with Keynesian welfare state planning. This model conceptualised planning as a scientific and technocratic endeavour, in which expert planners would diagnose problems, generate alternatives, and determine optimal solutions through linear processes of cost–benefit analysis, modelling, and forecasting (Davidoff, 1965; Faludi, 2013). It was under this paradigm that planning sought to produce public goods such as housing, transportation infrastructure, and sanitation systems, in the service of state-led development and redistribution (Diefendorf, 1989).

However, the limitations of technocratic rationality, expressed in its blindness to social conflict, inequality, and power, became increasingly evident by the 1960s and 1970s. Civil rights movements, urban uprisings, and feminist and anti-colonial struggles exposed the exclusions and injustices embedded in expert-led planning. This gave rise to advocacy planning and radical critiques of the profession. Planners such as Davidoff (1965) argued for a pluralistic approach in which planning served multiple publics, particularly marginalised groups. Arnstein’s (1969) classic “Ladder of Citizen Participation” denounced tokenistic forms of engagement and demanded deeper democratic inclusion. Concurrently, thinkers like Lefebvre (1974), Harvey (1973), and Castells (1972) provided structural critiques of planning as a tool of capitalist accumulation, spatial segregation, and state control, challenging its claim to neutrality.

In the 1980s and 1990s, communicative and collaborative planning gained prominence, influenced by the deliberative democratic theories of Habermas (1985, 1991, 2015). Scholars such as Forester (1982, 1999) and Healey (1998, 1999) reframed planning as a dialogical practice embedded in institutional and cultural contexts, emphasising stakeholder engagement, mutual understanding, and consensus-building. These approaches sought to democratise planning by foregrounding the co-production of knowledge, shared values, and collective reasoning. At the same time, strategic spatial planning emerged as a more managerial and integrative framework. It moved beyond traditional land-use planning to focus on cross-sectoral coordination, territorial competitiveness, and spatial visioning across governance scales (Albrechts et al., 2003; Healey, 2006; Ferreira et al., 2009). Strategic planning aimed to reconcile fragmented institutional landscapes and align public investment with long-term development goals, though it often retained a technocratic logic. Simultaneously, the rise of neoliberal urbanism reshaped planning practice. In many contexts, planning became subordinated to market rationality, promoting public–private partnerships (PPPs), entrepreneurial governance, and urban competitiveness (Harvey, 1989; Peck and Tickell, 2002). The planner’s role shifted from that of a redistributive technocrat to a facilitator of growth coalitions, often at the expense of social equity and spatial justice (Brenner, 2009; Fainstein, 2014).

While the planning paradigms described above have been more prominent in western countries, particularly in the US and (North West) Europe, in other geographies, planning has developed under different political, social, and historical trajectories, deeply shaped by postcolonial legacies, state-led development, and the realities of rapid (peri)urbanisation, informality, and inequality, often leading to hybrid practices that combine formal state planning with community-based arrangements (Miraftab, 2009; Frediani and Cociña, 2019; Kamana et al., 2024). In Asia, for example, state-led strategic and technocratic planning remains influential, emphasising economic growth, infrastructural expansion, and spatial order, although increasingly incorporating environmental and participatory dimensions (Kunzmann, 2015). Traditions of participatory planning as well as radical and insurgent planning have also emerged in these other geographies, particularly in Latin America and Africa but also parts of Asia, often as responses to authoritarian pasts and persistent inequality (Beard, 2003; Miraftab, 2009; Frediani and Cociña, 2019).

More recently, digitalisation and investments in smart cities worlwide have reshaped planning by enabling data-driven, real-time decision-making and more efficient urban management (Kitchin, 2014; Bibri, 2019). Tools like geographical information systems, sensors, and big data allow planners to model multi-sector, complex dynamics, aiming at evidence-based interventions (Pettit et al., 2018; Kandt and Batty, 2021). These technologies make planning increasingly technologically mediated, also influencing participatory approaches (Ataman et al., 2025; Falco and Kleinhans, 2018; Gonçalves et al., 2024; Pfeffer et al., 2013). However, these technologies also raise concerns about surveillance, citizenship, privacy, and inequality (Thatcher et al., 2016; Kitchin et al., 2019; Rose et al., 2020; Cardullo and Kitchin, 2025; Gonçalves et al., 2024). Another global trend in planning is the introduction of sustainable and resilient planning frameworks in response to global socio-ecological crises, aiming to integrate environmental, social, and economic considerations while addressing long-term challenges under conditions of uncertainty and complexity (Berke et al., 2006a; Bibri, 2019; Meerow et al., 2016), thus in line with strategic approaches (Albrechts et al., 2003).

From the above, it can be said that there is no single uncontested “main paradigm” in planning today, but rather an uneven landscape of planning practices in which market-based strategic action coexists with more emancipatory efforts that combine participatory and collaborative planning with sustainability and resilience frameworks, often shaped by the pressures of neoliberal urban governance (Angelo and Baiocchi, 2024). While collaborative and strategic approaches offer pathways toward more inclusive practices, they remain constrained by enduring power asymmetries, technocratic inertia, and the hegemony of market-based governance. Understanding planning as a historically contingent, politically embedded, and ethically charged practice is essential for reclaiming its emancipatory potential (Miraftab, 2009).

Planning paradigms often entail different planning activities. For example, rational planning focused on selecting and implementing the ‘most optimal’ plan from various alternatives, leading to practices like master planning. This structured process starts from understanding the problem in a given context and setting goals for the generation and evaluation of alternatives, with explicit links to implementation (Lawrence, 2000). Other authors include additional activities pertaining to planning processes, such as data analysis and outcome monitoring (Berke et al., 2006b) as well as stages emphasising sustainability in urban development (Teriman, 2012). More recently, Rocco et al., 2024b proposed a comprehensive model incorporating the activities of strategic planning and communicative action through an iterative series of steps and underlying the importance of public participation and stakeholder engagement in planning, which is well aligned with the hybrid planning paradigm of today that generally combines participatory planning with strategic sustainability and resilience frameworks.

2.2 Public participation

Various frameworks have been developed to unpack the complexity inherent in participatory processes, offering insights into the dynamics of stakeholder engagement, power relations, and decision-making structures. One of the first scholars to conceptualise public participation was Arnstein (1969). Amidst civil rights movements, anti-war protests, and countercultural movements in the late 1960s, Arnstein conceptualises public participation as levels of power distribution through which the “have-not” citizens and communities can be deliberately included in decision-making processes. Through the same critical lenses, Pretty (1995) later derived a typology of participation that considers how (material) resources interact with power dynamics. By analysing the interests of both facilitators and participants within participatory processes, White (1996) identified four major forms of public participation: nominal, instrumental, representative, and transformative. Two other important typologies are three-dimensional: The Democracy Cube (Fung, 2015) represents public participation using three dimensions, including authority and power levels, intensity of communicative exchange, and degree of participants’ inclusivity; and the PowerCube Framework (Gaventa, 2006), which explores power dynamics within participation processes across the three axes of levels, spaces, and forms of power.

A recent contribution to the conceptualisation of public participation is the 3A3 framework by Hofer and Kaufmann (2023), a multi-dimensional framework that embeds participation in planning processes and the wider context. The 3A3 framework defines public participation as consisting of three interacting dimensions (actors, arenas, and aims), each constituted by three interacting elements, thus encompassing nine elements in total. The first dimension – actors – addresses the subjects involved in participation, their roles, and applied recruitment strategies. The second dimension – arenas – examines how participatory processes are structured; it captures the spaces, formats and rhythms of participation. And lastly, the third dimension – aims – encompasses the issues, rationales and outcomes of participation. The framework is based on a comprehensive review of the existing participation frameworks and theories, and because of its comprehensiveness is a suitable frame for understanding diverse forms of participation, from top-down state-led to bottom-up insurgent participation.

2.3 Spatial justice

Debates about social (in)justices in cities are not recent. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when social and political movements of unprecedented strength took place around the world, urban scholars and academics were propelled to include a moral dimension into studies about the urban environment and the living conditions therein. This movement was the origin of critical urban theory. Key contributions during this period were Jacobs’ (1961) “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”; Sherry Arnstein’s “A Ladder Of Citizen Participation” (1969); Henri Lefebvre’s “The Production of Space”; Manuel Castell’s “The Urban Question” (1972); David Harvey’s “Social Justice in the City” (1973); among others. The concept of “spatial justice” emerged from these debates about social justice in cities. It has been developed and debated primarily by Dikeç (2009) and Soja (1980, 2013) in response to a dominant historical account of social justice. Influenced by Lefebvre’s spatial production theory, both scholars explore the dialectical relationship between (in)justice and spatiality and to role that spatialisation plays in the production and reproduction of domination and repression. Such a dialectical approach gave rise to what is today known as the “spatial turn” in the social sciences, where the spatial dimension of injustice is considered alongside its historical dimension. With an emphasis on the spatial dimension that is intentional and focused, though temporary, Soja argues, “spatial justice as such is not a substitute or alternative to social, economic, or other forms of justice but rather a way of looking at justice from a critical spatial perspective” (Soja, 2009, p. 2).

In parallel to urban critical studies, justice theory has also evolved within the field of political philosophy, strongly influenced by the distribution principles of ‘equal opportunity principle’ and the ‘difference principle’ by Rawls (1971), the ‘politics of difference’ by Young (1990), and the ‘politics of recognition’ by Fraser (2000). These ideas have consolidated as a conceptual framework for understanding (1) where injustices emerge, (2) which processes exist to address such injustices, and (3) which groups of society are marginalised and excluded (Jenkins et al., 2016; Schlosberg, 2004; Schlosberg and Collins, 2014). These refer to three core dimensions (or tenets) of social justice: distributive, procedural, and recognition (Rocco et al., 2024a; Rocco, n.d.). Importantly, the three dimensions are mutually reinforcing and should be addressed simultaneously, as inequitable distributions of benefits and burdens, limited participation in decisions, and lack of recognition all work to produce and reinforce socio-spatial injustices (Schlosberg and Collins, 2014).

Bridging the two fields of urban critical theory and political philosophy, a socio-spatial perspective on the three dimensions of justice considers the socio-spatial processes through which injustices are (re)produced (Soja, 2013), capturing distributive injustices (how benefits and burdens are distributed across space and how space influences such distributions), recognition injustices (how space contributes to oppression and dispossession of certain groups and how oppression in turn shapes space), and procedural injustice (how space affects decision-making and how decision-making sustains spatial inequalities) (Goncalves et al., 2025). In Fainstein (2014) concept of the just city, the three dimensions aligns with the governing principles of equity, democracy, and diversity. However, despite this strong theoretical and conceptual basis, a framework that links spatial justice, public participation, and strategic planning is still missing.

3 The SJ-3A3 conceptual framework

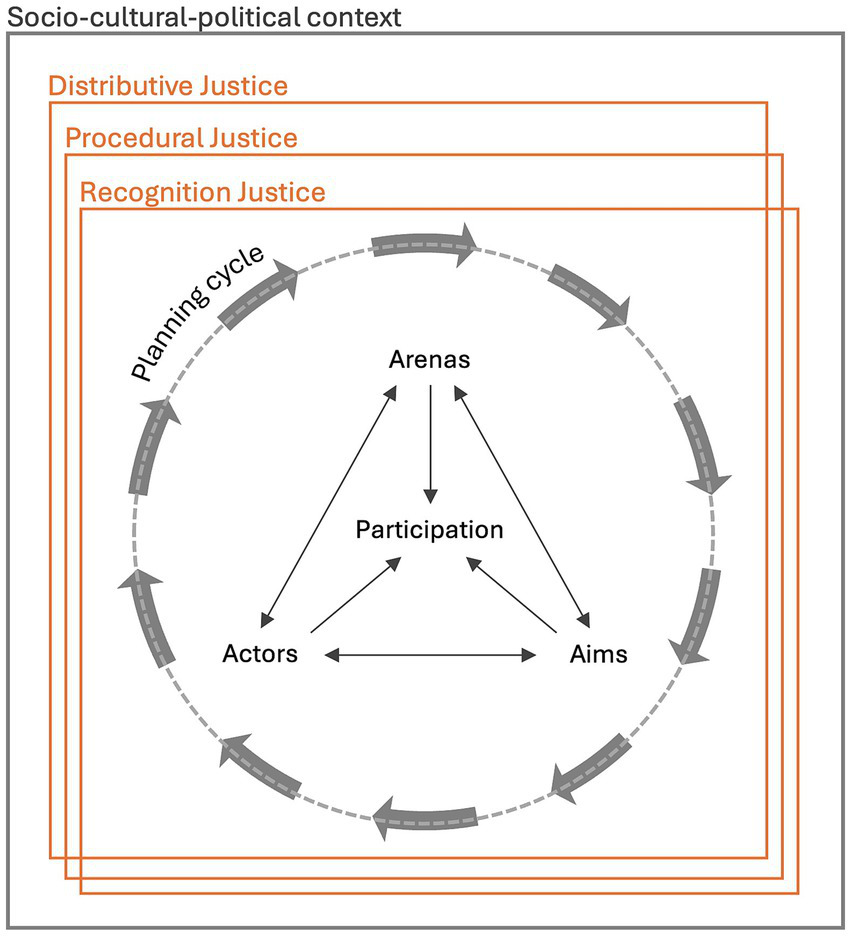

Integrating the literature presented above, we developed the SJ-3A3 framework (Figure 1), which aims to address the lack of integration between participatory practices and planning processes and introduce an explicit spatial justice (SJ) lens to participatory planning. The framework combines the TU Delft Strategic Planning Cycle (Rocco et al., 2024b) with the 3A3 conceptual framework for public participation (Hofer and Kaufmann, 2023), focusing on participatory practice through a spatial justice lens. Table 1 provides detailed descriptions of each dimension of the framework.

Figure 1

The SJ-3A3 conceptual framework. (adapted from Hofer and Kaufmann, 2023).

Table 1

| Strategic planning aspects | ||

|---|---|---|

| Planning phase | Description | |

| 1 | Contextualisation | Identify contextual needs and priorities |

| 2 | Engagement | Engage key stakeholders |

| 3 | Visioning | Design a vision and strategic goals |

| 4 | Strategy design | Design alternative strategies |

| 5 | Strategy evaluation | Evaluate the impact and feasibility of alternative strategies |

| 6 | Policy design | Design policies according to the strategy and vision |

| 7 | (Spatial) Intervention design | Design (spatial) interventions according to the strategy and vision |

| 8 | Piloting | Pilot proposed policies/interventions |

| 9 | Pilot evaluation | Evaluate pilot results and adapt if necessary |

| 10 | Upscaling | Upscale policies and interventions based on the evaluation results |

| Public participation aspects | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Element | Description |

| Actors | Subjects | People involved in the process, generally categorised into (1) civil society (institutionalised and non-institutionalised), (2) the government or state, and (3) the business sector. |

| Roles | Subjects have different roles, which can be: Initiators, sponsors, organisers, decision-makers, facilitators, mediators, technical experts, participants in general (citizens, clients, beneficiaries). | |

| Recruitment | Open (self-selection) to closed (small, limited number of subjects) selection. Closed: random vs. targeted selection. | |

| Arenas | Spaces | Spaces are both physical (the venue where participation happens) and socially constructed (invited, created/claimed, closed). |

| Formats | Formats are various and diverse, including public hearings and meetings, deliberative fora like citizen juries, participatory budgeting, competitions, interactive websites, working groups, public forums, community meetings, online engagement, among many others. | |

| Rhythm | Refers to the time-component of participation, differentiating between fixed and pre-defined (both short and long-term) or ongoing open-ended processes. It also considers the time allocated to different subjects. | |

| Aims | Issues | Refers to the planning issue in question. |

| Rationales | Refers to the underlying ideologies and rationales, including the intentions of individuals at the subject-level and the rationales for why participation is called for in the first place (normative vs. pragmatic). | |

| Outcomes | Differentiates between tangible and intangible outcomes. | |

| Spatial justice lens | |

|---|---|

| Dimension | Description |

| Distributive | How benefits and burdens are distributed across space and how space influences such distributions |

| Procedural | How space affects decision-making and how decision-making sustains spatial inequalities |

| Recognition | How space contributes to oppression and dispossession of certain groups and how oppression in turn shapes space |

Description of the SJ-3A3 framework.

The framework emphasises the integration of public participation and stakeholder engagement in strategic planning through an iterative cycle. The cycle consists of a series of phases, including identifying needs, engaging stakeholders, visioning, designing strategies, evaluating feasibility and impact, designing policies, designing interventions, implementing and testing, evaluating, and scaling up. Translating the planning process into concrete phases helps to understand how participatory tools and methods can support specific planning activities.

The phases in the cycle are not meant as a rigid normative step-by-step guide, but a dynamic and flexible framework of possible and desirable planning activities logically articulated that supports collaboration between city stakeholders, enabling continuous adaptation and refinement of visions, strategies, and interventions in response to evolving urban challenges and local contexts. This approach ensures that planning processes are responsive to context, grounded in shared values, and geared toward achieving long-term outcomes.

The iterative cycle is based on the TU Delft Strategic Planning Cycle (Rocco et al., 2024b), a model of participatory strategic planning also developed within the UP2030 project and validated by partner municipalities involved in the project, as well as by researchers and practitioners engaged in participatory planning within sustainability transitions. It was considered sufficiently comprehensive to represent the diverse activities related to contemporary strategic planning while serving as a coherent framework connecting planning research and practice.

To understand participation, we adopt the 3A3 framework because its three dimensions and nine elements provide a comprehensive lens to understand the complexity of participation. This allows a comparison of different forms, ranging from informal, community-driven initiatives to institutionalised, government-led processes. This comparative potential is particularly relevant for analysing the eight case studies presented in this paper, which vary significantly in terms of scale, governance arrangements, and modes of participation (described in Section 4).

Finally, the explicit integration of a spatial justice lens positions the SJ-3A3 framework as a critical tool for participatory planning in sustainable urban development. By foregrounding distributional, procedural, and recognition aspects of participatory practices in planning and design, the framework ensures that questions of equity, inclusion, and representation are systematically considered. In doing so, it provides a sufficiently abstract yet practical structure for understanding how participatory practices can foster spatial justice in diverse urban contexts.

4 Methodology

In this section, we introduce the cases considered in the paper and explain how data collection and analysis was conducted.

4.1 Cases

Following a strategic perspective on planning beyond land-use (Albrechts et al., 2003) and a broad definition of participation as a “collective act and a moment, or a series of moments, in which people come together to jointly tackle a task and contribute to shaping a place” (Hofer and Kaufmann, 2023, p. 361), we consider eight diverse cases of participatory planning and design. The cases are diverse in nature, including the development and testing of new participation tools, the implementation of existing and well-established toolkits, as well as the use of data-based frameworks and simulations in participatory planning activities in collaboration with local actors and/or citizens. The approaches taken in the cases are therefore at different stages of development, from pilot research-based methodologies to fully developed commercial tools, shedding light on different dynamics related to the development and implementation of participatory instruments. This diversity allows us to investigate various ways in which citizens and stakeholders can be engaged in planning activities, beyond the traditional consultation processes. Furthermore, all cases include innovative methods with potential to foster spatial justice through participatory planning, being applied in various geographical contexts across Europe and beyond. Table 2 provides a summary of the eight cases analysed in the paper, which are described briefly next. All cases are associated Horizon Europe UP2030 project (2023–2025).

Table 2

| Case | Summary | Geographical context | Associated co-author(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Promoting active school travel | Contextualisation of tailored toolkits for school community engagement, with a focus on children’s routes to school | Belfast, United Kingdom Budapest, Hungary |

MS, NM |

| B | Evaluating housing policies using the UGEM model | Use of the UGEM model to assess housing policy scenarios | Thessaloniki, Greece | DK, SG |

| C | Digital storytelling for a just transition | Development of a digital participatory tool for citizen engagement | 10 European cities | MD, CV, NP, AG, SV |

| D | Assessing liveability in cities | Application of a multidimensional index at the city-level to support decision-making | 25 Spanish cities | ADS, AJ, MGH |

| E | Storytelling for participatory exchange | Development and pilot application of a new methodology for citizen engagement | Rotterdam, The Netherlands | AJ, TD, SA |

| F | Facilitating climate urban design | Contextualisation and application of a participatory toolkit for community engagement | Thessaloniki, Greece | CV |

| G | Community mapping for urban greening | Contextualisation of a participatory mapping tool for citizen and community engagement | Budapest, Hungary | LF |

| H | Benchmarking spatial justice in urban transitions | Development and pilot application of a new framework for qualitative assessment of resilience plans from a spatial justice perspective | 10 European cities Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

JG, RR |

Summary of the cases, geographical context, and paper co-author associated with the case (abbreviated by initials).

All cases are associated with the Horizon Europe UP2030 project (2023–2025).

Case A, Promoting Active and Safe School Travel, refers to the co-creation of participatory toolkits for active school travel developed in collaboration with local authorities and other local enablers for two municipalities. For the city of Belfast, the toolkit was developed in collaboration with the Belfast City Council (BCC) and Healthy Cities Belfast (HCB), and for the city of Budapest, with Centre for Budapest Transport (BKK). The toolkits are based on the Child and Youth Friendly Urban Design (CYFUD), an adaptable framework built on child-centred research and practice-based evidence. They aim to foster children’s safe and active travel to school, promoting inclusive urban planning and design, as well as their participation in the co-creation of healthy neighbourhoods.

Case B, Evaluating Housing Policies using the Urban Green Economy Model (UGEM) to evaluate policy scenarios at the urban level. UGEM is based on the Green Economy Model (GEM) (Bassi, 2015), which is designed to analyse green economy and low-carbon development scenarios at national or regional levels. The case in this paper refers to the downscaling of the GEM model to simulate policy scenarios at neighbourhood level, enabling the evaluation of spatial justice considerations within cities. After the adaptation, the UGEM will be employed to simulate two scenarios for the city of Thessaloniki based on the city’s Action Plan for the 2030 Agenda, namely (1) the impact of social housing for vulnerable districts, and (2) the impact of energy poverty policies that include energy-efficient measures and consequently carbon footprint mitigation.

Case C, Digital Storytelling for a Just Transition, refers to the development of Neutrality Story Maps (NSM), a communication platform developed with 10 European cities from the UP2030 project in a co-creative process including workshops, interviews and surveys. NSM allows citizens and policymakers to explore different ways of engaging in climate neutrality-related issues through digital storytelling and future scenarios. By enabling citizens to share their perspectives on climate and sustainability while helping cities communicate challenges and engage communities through an accessible multimedia format, the tool fosters trust between citizens and city officials.

Case D, Assessing Liveability in Cities, refers to the development of the Liveable Cities Index, a multi-method tool using 75 indicators distributed in 5 categories - Society, Environmental Quality, Health, Land Use, and Resources. The result is an aggregated index of liveability and a liveability ranking, with the possibility to disaggregate the index according to each category. As such, it provides either an overall or sectoral picture of the cities’ liveability situation, which allows the identification of improvement areas. The Liveable Cities Index has been employed in 25 Spanish cities.

Case E, Storytelling for Participatory Exchange, refers to the development and piloting of a new methodology for citizen engagement in urban development spaces. The methodology enables citizens to tell imaginary stories to reflect their real-life experiences, creating an engaging and productive space for participants to explore pre-determined topics and consider the future of their living environments. The methodology is centred around workshop settings where citizens create stories using a guided story- building process. Participant submissions are then analysed to understand the thoughts, feelings and desires contained in their imaginaries, with consensus identified across participant groups. The methodology was applied to a pilot case in the city of Rotterdam.

Case F, Facilitating Climate Urban Design, refers to the use of the Urban Design Climate Workshop (UDCW) Facilitation toolkit in the city of Thessaloniki, contributing to the development of the District Climate Action Plan for the Diotikirion district. The toolkit is a family of participatory tools supporting knowledge sharing and co-production in a multi-actor context, facilitating communication about urban climate resilience and bridging complex and science-based inputs with tacit knowledge.

Case G, Community Mapping for Urban Greening, refers to the creation of a Community Map in collaboration with Budapest’s City Planning Department to enable citizens across Budapest to identify potential locations to add or enhance green infrastructure, as part of the city’s plan to upgrade and renew its Green Infrastructure Strategy. A Community Map is an interactive web app that supports the development of bespoke maps to facilitate participatory planning, community engagement, and citizen science programmes. The system has been designed to allow new projects to be added without the requirement for additional development (programming), and an administration tool developed to support this task (Ellul et al., 2013). Each project is allocated custom themes depending on the project requirements and a variety of ‘skins’ can be configured to give the website a different appearance in each case.

Case H, Benchmarking Spatial Justice in Urban Transitions, refers to the use of the Spatial Justice Benchmarking Tool (SJBT) to assess transition plans of 10 European cities and the city of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil with respect to spatial justice. The SJBT is a qualitative multi-dimensional assessment framework that draws from justice theory and urban governance analysis. The tool was designed to evaluate how urban sustainability transition plans integrate spatial justice considerations by focusing on three core dimensions of justice: distributive, procedural, and recognition. It unpacks these dimensions into a set of nine evaluative criteria that examine how resources, decision-making processes, and the needs and identities of diverse social groups are addressed in planning (Lopez et al., 2024). The criteria can be utilised in policy analysis exercises but also serve as benchmark for discussion and policy design.

4.2 Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis were conducted in a collaborative process between December 2024 and June 2025. Specifically, the first and second authors defined the analytical framework described in Section 3. Based on this framework, a template was created in an online collaborative whiteboard platform to collect data from the eight cases. It included questions about the phases of the planning process, the actors, arenas, and aims of the case, and barriers and enablers to each of the three dimensions of spatial justice. The template was filled out by the co-authors who were involved in the cases and were responsible for collecting and providing data about their respective cases (Table 2). The analysis of the data collected was performed primarily by the first author and supported by all co-authors to gather additional data and for further clarifications, which were also documented in the online collaborative whiteboard platform. The analysis and results were discussed in several collective meetings among authors, and conclusions were drawn together.

5 Results

Table 3 presents a comprehensive summary of the results with the key findings related to the aspects of strategic planning, public participation, and spatial justice of the SJ-3A3 framework. Concerning the planning phases, a concentration of cases is observed in Phases 1–3 and Phase 9. Specifically, the contextualisation phase (Phase 1) and pilot evaluation have the highest number of cases, with six examples. This is followed by the stakeholder engagement and visioning (Phases 2 and 3), each with five cases, and then the strategy evaluation phase and upscaling (Phases 5 and 10) with four cases. Strategy design and intervention design (Phases 4 and 7) are each represented by just three cases, and policy design and piloting (Phases 6 and 8) have the fewest examples, with only two cases each. Next, the analysis of public participation reveals the diversity in actors, arenas and aims of the eight cases. This was expected given the broad definitions of strategic planning and participation adopted in this study. Finally, Table 3 also summarises the discussion on spatial justice by highlighting key enablers to each justice dimension.

Table 3

| Strategic planning aspects | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning phase | Case | ||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | ||

| 1 | Contextualisation | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 2 | Engagement | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 3 | Visioning | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 4 | Strategy design | X | X | X | |||||

| 5 | Strategy evaluation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 6 | Policy design | X | X | ||||||

| 7 | (Spatial) Intervention design | X | X | X | |||||

| 8 | Piloting | X | X | ||||||

| 9 | Pilot evaluation | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 10 | Upscaling | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Public participation aspects | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Element | Key findings |

| Actors | Subjects | Communities, individual citizens, specific groups (school children), decision-makers and public authorities, experts, practitioners, and researchers |

| Roles | Various roles due to the diversity of subjects in the cases Citizens and communities as co-creators |

|

| Recruitment | Related to place or group | |

| Arenas | Spaces | Digital, place-related, decision-making/institutional spaces |

| Formats | Workshops, online engagement, institutional sessions Type of data (quantitative standardised data vs. qualitative thick data) |

|

| Rhythm | Dependent on the case and on-demand or periodic and linked to the planning process | |

| Aims | Issues | Place-based, group-specific, policy/governance-related |

| Rationales | Mostly pragmatic Normative aspects related to focus on specific groups or (policy) issues |

|

| Outcomes | Mostly tangible Reflexive and inclusive processes as intangible outcomes |

|

| Spatial justice lens | |

|---|---|

| Dimension | Key enablers |

| Distributive | Visualisations of unequal distributions Use of comprehensive approaches to vulnerability as opposed to single indicators Cross-sectoral interventions Combination of quantitative and qualitative data |

| Procedural | Co-creation of the participation process and tools and tailoring to needs of specific contexts and groups Diverse participation approaches to attend to the diversity in stakeholders and citizens Transparency Open and standardised methodologies Situated recruitment process Monitoring and feedback mechanisms Representativeness of actors/citizens engaged in the participatory activities and number of participants Combination of participatory methodologies and tools throughout the planning cycle |

| Recognition | Digital literacy and access to digital devices Visualisations Co-creation of data Anonymity and privacy-preserving mechanisms Intersectional approach Thick data and situated knowledges (oral narrative, archives, photos, videos, ethnographic work, etc.) Plurality of narratives and perspectives Positionality of facilitators/moderators |

Summary of the results and key findings based on the SJ-3A3 framework.

The subsequent sections describe these results in detail, starting with situating the cases in the planning cycle, as this helps to have a more concrete understanding of how participation is used in planning practice. Next, the analysis of public participation, through the dimensions of actors, aims and arenas is presented, followed by the analysis of the spatial justice in dimensions.

5.1 Situating cases in the strategic planning cycle

Table 3 shows how each case maps into the phases of the planning cycle. From this distribution, three participation patterns are identified: (1) Early-phase emphasis, with Cases A and E focusing primarily on the initial phases of the planning cycle; (2) Evaluation-oriented cases, with Cases B and H concentrated in the evaluative phases; and (3) Broad-coverage cases, with Cases C, D, F, and G connected to six out of ten planning activities, but in different ways. The cases and their connection to planning practice are described next, following these patterns.

Case A is primarily connected to the three initial phases of the planning cycle. Through a participatory process, the case involved local authorities and key enabling actors to identify existing initiatives that promote safe and active school travel (Phase 1). For the city of Belfast, the case focused on the Walking Bus pilot initiative, which encourages children to walk part or all of the route to school, aiming to increase walking, reduce car dependency, and improve air quality and local traffic conditions. Similarly, in Budapest, the School Street pilot program, which restricts car access on the school street for a week, enables more and safer active trips to school. For both cities, tailored participatory toolkits were developed to provide roadmaps and campaign material to engage schools with the initiatives identified and create awareness of their health benefits for school children (Phase 2). The toolkits include participatory activities to engage parents, teachers and different primary school age groups in mapping exercises, and through that reflect, assess and reimagine their route to/from school (Phase 3). In these specific cases, the toolkits aim to promote existing pilot initiatives, thus also contributing to upscaling efforts (Phase 10).

Case E also links to the initial phases of the planning cycle, but through storytelling. The novel participatory approach employed in this case uses a digital platform in a workshop setting, where participants build imaginary stories to reflect their perspectives on topics of local relevance. In the pilot case of Rotterdam, the subsequent analyses of the stories revealed citizen perceptions about local challenges, such as a lack of green space and pollution in the city, and their causes and potential solutions. The case also produced a series of visualisations of desired urban futures of participants, supported by literary and sentiment analysis. These insights are primarily connected to contextualisation and visioning (Phases 1 and 3), but the approach adopted also includes a dedicated recruitment process, supporting stakeholder engagement (Phase 2). The subsequent sharing of the materials developed in the workshop can engage further stakeholders, both citizens and other public/private actors (Phase 2), and the input collected and processed allows for the creation of actionable insights for decision-making stakeholders (Phase 4).

Concerning evaluation-based cases, Case B illustrates the use of scenario simulations for budget allocation and strategic design (Phase 5). Specifically, Case B will allow for the evaluation of two housing scenarios developed by the municipality of Thessaloniki in collaboration with key stakeholders such as the Local Housing Brokers Association and Local Technical Chamber. The two scenarios focused on (1) the impact of social housing for vulnerable districts, and (2) the impact of energy poverty policies that include energy-efficient measures and consequently carbon footprint mitigation. These scenarios can lead to policy pilots, which can be re-evaluated with the same simulation environment later in the planning cycle (Phase 9). Case H, in contrast, employs a qualitative approach to support the integration of spatial justice considerations in strategic planning. In this case, strategic documents of eleven municipalities were assessed against a spatial justice benchmark, generating critical insights for the prioritisation of alternatives in strategic design (Phase 5) and the assessment of pilot policies and (spatial) interventions (Phase 9), ultimately leading to institutional embedding of spatial justice principles into mainstream urban governance and planning practices (Phase 10).

Finally, we present the cases that cover a large part of the planning cycle. Case C links to six out of ten phases thanks to the flexibility afforded by digital participation platforms. In this case, three “types” of Neutrality Story Maps were co-created to address the diverse needs of the 10 cities in using digital storytelling for planning communication and citizen engagement. The three types defined based on co-creative workshops with 10 European cities are: (1) crowdsource stories from citizens to identify their needs and priorities (Phase 1), gather insights about their future vision of the city (Phase 3), engaging them in the urban planning and design process (Phase 2) as such, providing cities with crucial knowledge needed to define strategies grounded in the citizens’ lived realities (Phase 4), and evaluating the impact of specific interventions on people’s lives (Phase 9); (2) populate the platform with curated stories displayed on a timeline and a map to communicate their success stories and raise awareness (Phase 10); and (3) create a longer “scrollytelling1” article with data and maps intended at communicating the risks they are addressing in an accessible way with the possibility of using personas (Phase 10).

Case D supports several phases in the planning cycle by providing a comprehensive assessment of liveability in cities. In the early stages (Phase 1), the Liveable Cities Index used in the case provides a comprehensive framework to identify liveability needs and issues based on five categories: Society, Environmental Quality, Health, Land Use, and Resources. The five-dimensional framework is also useful to support feasibility and impact assessment (Phase 5) and co-designing policies and spatial interventions (Phases 6 and 7). In the late stages, it contributes to the evaluation and monitoring of liveability-related pilots (Phase 9) and their upscaling (Phase 10).

Case F is somewhat similar to Case C, in which it also uses diverse participatory methods and tools to support knowledge sharing and co-production in a multi-actor context, facilitating communication about urban climate resilience topics and bridging complex and science-based inputs with tacit local knowledge. The toolkit used in this case has been conceived to foster dialogue between experts and non-experts, to match urban design solutions for climate mitigation and adaptation with everyday practices and needs of citizens, and to address capacity building issues of public administrations and decision makers. The participatory tools employed include collaborative mapping (Phase 1) and a design visioning (Phase 3) exercise to survey the criticalities about the quality of the urban spaces, services, accessibility and the community priorities about urban design interventions (Phase 1). The UDCW facilitation toolkit has been used in synergy with UDCW simulation toolkit in an iterative process that methodologically allows for strategic evaluation (Phase 5) and co-design (Phase 7), while also supporting the definition of pilot actions (Phase 8).

Case G is connected to several phases throughout the planning cycle by enabling the integration of community input into the planning process from the very beginning. The Community Map developed in Case G primarily contribute to the identification of local needs and issues while engaging communities and individual citizens as key stakeholders earlier in the planning process (Phases 1 and 2). For example, in the case of Budapest, over eight hundred contributions were received in which detailed ideas and images were mapped on where and how to increase green spaces in the city. Three hundred of these proposals were identified as land managed by Budapest City Council. Subsequently, the council has recommended to start a pilot sponge city project, which would form the framework for small-scale green infrastructure projects part of the city’s new Green Infrastructure Strategy. This shows that community input is crucial for developing visions, strategies, policies, and (pilot) interventions that address the real and local needs of people (Phases 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8). Community maps can also help evaluate and monitor the piloting of policy and design interventions by following up with communities (Phase 9).

In summary, at the beginning of the planning cycle (Phases 1–3), we find cases in which participation is focused on citizens, specific groups and local communities. An exception is Case D, where the Liveable Cities Index can be applied on a more localised scale, such as neighbourhoods, providing a more disaggregated and detailed contextualisation of liveability at the local level, but does not involve citizen or community engagement. Next, strategy design (Phase 4) appears in three cases, where the input gathered in the previous three phases is used to inform strategy design, which constitutes an indirect engagement, since the participants are not directly involved in strategy design. This is also the cases in the piloting phase (Phase 8), where input from previous phases informs piloting interventions. Overall, Phases 5 to 10 present varying cases and no clear pattern. For example, the intervention design phase (Phase 7) includes data-driven frameworks (Liveable Cities Index, Case D), participatory workshops (Case F) and digital platforms (Case G). Similarly, the scale-up phase (Phase 10) includes digital platforms (Case B), data-driven frameworks (Case D), and the qualitative-based assessments (Case H).

5.2 Public participation analysis

The analysis of the actors, arenas and aims in each of the cases reveals that participation dimensions and associated elements are highly interlinked and influence each other (see Table 3). All cases have a planning issue as a starting point, which can be place-based (Cases E and F focus on the development of specific urban areas), group-specific (Cases A, C and G focus on individual citizens or specific groups), or policy/governance-related (Cases B, D and H contribute to policy/governance related to specific areas: housing, energy poverty, liveability and spatial justice). By looking at the intersection of subjects and format, three main combinations emerge: “multi-actor workshops,” “citizen digital participation,” and “institutional decision-making” settings, described next.

First, the “multi-actor workshop” setting of Cases A, E and F is defined based on a planning issue, which in turn influences the subjects involved and the spaces of participation. In Case A, a specific subject group (i.e., school children) is the starting point for the engagement, around whom a broader stakeholder ecosystem is included (i.e., school staff, educators and parents). The participatory activities take place in spaces between the school and the children’s home, given the focus on promoting safe walking routes. In contrast, in Cases E and F, a specific development area is the starting point for the identification of place-based subjects. In both cases, the spaces of participation in or near the development areas are prioritised.

Second, the “citizen digital participation” setting of Cases C and G takes individual citizens or specific communities as a starting point to address a specific planning issue. Specific groups, such as the youth, low-income households, and migrant communities, can be targeted through hybrid spaces, such as online outreach campaigns or through community representatives. Digital participation here can be passive, in the sense that citizens and communities are recipients of information shared by public authorities, or active, when they contribute with sharing data about their experiences or preferences. In the latter case, citizen data is treated as both ‘input’ for experts to make decisions and ‘stories’ for communicative purposes to engage and create awareness among other citizens and/or stakeholders.

Third, in the “institutional decision-making” setting of Cases B, D and H, the subjects involved are mostly local governance actors and experts (researchers and practitioners), who interact via a series of (periodic or on demand) meetings and internal sessions in institutional spaces. The cases, however, differ in their format: While Cases B and D are based on data-driven insights, Case H is based on qualitative assessments.

The combinations of format and subjects described above have implications for the other participation elements in Table 3. When it comes to roles, in a workshop format, an initiator or organiser is necessary and always present. Additionally, Cases E and F illustrate the role of citizens and communities as co-creators and co-designers in the workshops alongside technical experts. These cases also highlight the importance of a moderator/facilitator to mediate sessions, given the diversity of subjects involved. This brings the discussion to the recruitment. Among the cases in this study, one stands out with a dedicated recruitment methodology. In Cases E and F, the participants are identified through a collaborative process between the workshop facilitator (in this case, the Institute for Urban Excellence) and the participation initiator (role typically taken by municipalities or other bodies organising the participatory process), considering factors like previous involvement, projected impact, degree of representation, among others. In this process, the concept of snowballed stakeholder identification is key, to go beyond the awareness level of the initiator and attempt to reach less heard communities within a location. Communicative strategies were then designed with the initiator to recruit participants from target groups.

Another element is the rhythm of participation. In the “multi-actor workshop” settings, the length and frequency of participation is shaped by the format itself. Since workshops are organised locally and in-person, they require prior preparation and coordination among diverse actors, which often consumes more time than the workshop’s actual duration. In the “digital participation” setting, the flexibility of the digital environment allows for different rhythms. Engagement can follow an ongoing process without a set deadline or have a fixed pre-determined timeline. For example, Case G gathered citizen input through a data collection campaign with a fixed duration of two months, led by the Budapest City Council, which then informed concrete greening projects and the update of strategies in the city. The “institutional decision-making” setting operates through internal sessions either on-demand or periodic in iterative processes tied to strategic planning cycles, with frequency aligning with planning stages and project milestones. For example, in Case H, periodic check-ins can be used to monitor policy progress with respect to spatial justice.

Finally, the rationales and outcomes are discussed. Most cases have primarily pragmatic rationales, as they aim to respond to a specific issue, which in turn can be place-based, group-specific, or policy/planning-related. However, some cases also have a normative aspect, particularly Case H with the emphasis on spatial justice. Other cases that focus on marginalised groups also touch on normative aspects of participation, as they aim to foster inclusive planning by including usually unheard voices (e.g., Case F) or acting on specific policy issues such as energy poverty (e.g., Case B). The rationales are, in turn, connected to the types of outcomes observed: A pragmatic rationale leads to tangible outcomes, such as maps, datasets, policy recommendations, communication campaigns, while a normative rationale links to intangible outcomes, such as more reflective planning practices.

5.3 Spatial justice dimensions

Distributive justice emerged primarily in cases where participatory activities were used to reveal spatial inequalities and design and prioritise interventions. Case B, for example, allows for the assessment of policy scenarios targeting energy poverty and social housing, allowing for the identification of high-need areas and the distributional implications of proposed interventions. The identification of hotspot areas for priority intervention was also observed in Case F, but here the focus was on climate urban design interventions. These approaches provide critical evidence for redistribution claims toward vulnerable areas. Similarly, Case D offers data-based insights on liveability across urban contexts, helping to identify disadvantaged areas. However, while the index supports the identification of inequalities, it does not prescribe specific actions, and its effectiveness is contingent on the political will and institutional capacity to act on the index results. Another approach to distributive justice, seen in Cases F and H, focused on understanding intersectional vulnerabilities - how injustices are experienced differently across population groups. This case combined population data with participatory (thick) data to highlight spatially embedded intersectional injustices across population groups.

Distributive justice was supported by several enablers that helped make inequalities visible and actionable in the cases analysed. The use of visualisations, such as maps and visual storytelling, was particularly effective in highlighting uneven distributions of benefits and burdens. Moreover, approaches that employed comprehensive and intersectional understandings of vulnerability, rather than relying on single indicators, allowed for more targeted and situated interventions (Case F). The integration of quantitative and qualitative data further enabled planners to relate statistical patterns to lived experiences (Case F). Cross-sectoral collaborations and comprehensive data approaches (Cases F and D) that bridged urban domains were also considered crucial in addressing distributive justice.

However, key barriers remained. In Cases B and D, for example, the lack of high-resolution or disaggregated data (e.g., data only available at city-level rather than district or neighbourhood level) limited the capacity to identify and respond to localised needs. Even where data were available, translating data insights into actionable policy was highlighted as a challenge associated with a lack of institutional capacity, political constraints, and commitment. For example, Case A faced some resistance from the schools in the uptake of the active travel toolkits, which was then addressed through additional sessions with school representatives. Financial barriers also played a critical role, especially in urban regeneration efforts targeting vulnerable areas, where funding gaps may hinder the implementation of proposed interventions. Siloed sectoral approaches and a lack of political commitment to redistribution were also considered barriers across cases.

Procedural justice was approached in many cases through the idea of inclusive planning, based on the premise that the inclusion of citizens and other local stakeholders improves the fairness of planning processes. There was an emphasis on groups usually excluded from decision-making, such as children, the youth, and local communities affected by urban development (Cases A, C, E and F). Other cases illustrate the importance but also the challenge of including local actors and citizens in the creation of the participatory processes and the tools used for participation to ensure a proper user-tool-case combination. For example, in Case A, the participatory toolkits for active school travel were developed collaboratively in an iterative process that included input from experts, municipal agencies, local councils, schools and parents. Similarly, in Case C, the co-creation process has led to three different conceptualisations for a digital platform, which emerged from the different needs of municipalities. These two cases go beyond the inclusion of different stakeholders in the planning process, as they also tailor the process based on specific use cases and users: In Case A, the process was tailored to the specific planning issue of active mobility and the specific subject of school children. Similarly, Case C tailored the digital platforms based on the needs and capacity of municipalities to integrate new digital platforms for citizen engagement in their existing processes.

Transparency and open data and methodologies were identified as enablers of procedural justice. For instance, Cases B, D and F exemplify how planning tools can rely on shared data sources and visualisations to ensure that stakeholders understand both the rationale and implications of policy and design decisions. This helps reduce information asymmetries between experts, policymakers, and civil society. Another critical aspect of procedural justice was early engagement. Cases A, E and F all stress the importance of involving citizens and stakeholders from the beginning of the planning cycle to ensure that decisions are better informed and more representative from the start. Procedural justice is also evident in some cases that promote responsive planning through monitoring, feedback, and reflection. This responsiveness ensures that planning processes do not remain static but evolve alongside updates in data (Case D), community input (Case C), facilitator reflections (Case F), and benchmarking mechanisms (Case H).

Cases also demonstrated the enabling value of co-creating participatory processes and tools in ways that are tailored to the specificities of different groups and urban contexts. Rather than positioning participation as a secondary step, these cases incorporate stakeholders directly into the development and implementation of participation instruments, ensuring that processes reflect diverse perspectives and local knowledge. Related to that, the combination of diverse methodologies within participatory processes was also considered as an enabler, as it helps uncover different knowledge and perspectives. This was particularly strong in Case F, where a toolkit with different engagement methods was employed. Equally important were situated recruitment strategies, which fostered inclusive and local participation (for example, Cases A and E). Efforts to embed transparency through both open and standardised methodologies to build public trust and increase accountability were another enabler, particularly in data-driven cases like Cases B and D, alongside the possibility to monitor interventions through data and citizen feedback. For example, the digital platforms of Cases C and G allow for on-going citizen input on implemented interventions.

Despite these enablers, several barriers remain. Given the centrality of participation to procedural justice, one major challenge is ensuring the representativeness of participants. The translation of citizen insights into policy remained a recurrent difficulty, often due to rigid institutional processes or a lack of alignment with formal planning frameworks. This was particularly visible in cases that involved “less conventional” types of citizen engagement, such as storytelling (Cases C, E and F). Related to this is a risk of misinterpretation of participatory data, potentially leading to misaligned or ineffective interventions. Tokenist participation also emerged as a procedural barrier that can undermine inclusive planning, which was linked to “one-off” participation without adequate follow-up or integration into decision-making processes, which risks reinforcing procedural injustices. The latter was a general concern, given that all cases considered in this study are part of an innovation research project.

Recognition justice is addressed across several cases primarily through an explicit commitment to understanding vulnerabilities, their root causes, and the structural dynamics of exclusion and marginalisation. This approach is particularly evident in Case F, but also in Cases A, C, E, G and H. Most of these cases go beyond identifying inequalities by acknowledging the lived experiences of marginalised groups and embedding this understanding into planning processes. The integration of lived experiences and situated knowledge plays a central role in contextualising planning actions. In Cases C, E, F and G, citizens and communities contribute personal narratives, local insights, and community priorities that shape the direction and content of planning efforts. This attention to everyday realities ensures that planning is not only top-down but also reflective of local complexities and shows that the co-production of data is also a critical element of recognition justice. In Cases C, E, F and G, for example, citizens and stakeholders can influence different planning phases through participatory workshops and digital participation. This not only legitimised planning outcomes but ensured that diverse experiences were formally acknowledged in planning processes. In other cases, recognition justice is expressed through a focus on specific policy targets, such as social housing (Case B), energy poverty (Case B), liveability (Case D), and broader spatial justice objectives (Case H). In these cases, targeted policy assessments help reveal and prioritise areas of social vulnerability, ensuring that these concerns are not overlooked in strategic planning.

Recognition justice was found to be enabled by a deliberate focus on exposing and understanding the root causes of exclusion, marginalisation, and vulnerability, with Cases F and H adopting an explicit intersectional lens. The co-creation of (thick) data, through storytelling, community mapping, ethnographic methods, and other participatory means, allowed for the inclusion of lived experiences and situated knowledge, which is important for bringing nuance to standardised types of data. Related to this is the awareness of the positionality of facilitators. Overall, a plurality of narratives and perspectives was considered crucial to recognition justice, highlighting that people experience and value space differently. Reflections on the biases of dominant knowledge systems have led researchers and facilitators to treat oral histories and individual narratives as equally valid. In particular, in Case F, participatory mapping, layering scientific climate data with community observations, stories, and everyday experiences, has been used to complement the quantitative assessment of climate risks. In this case, participatory tools enabled different sources of knowledge to be discussed and interpreted collectively, negotiating final outcomes based on the co-creation of narratives that inform design through both thick data and performance-based information (Visconti, 2025). Efforts were also made to ensure privacy and anonymity, helping to protect sensitive information of personal testimonies.

Cross-cutting all justice dimensions, but particularly procedural and recognition justice, several cases demonstrate that engagement with specific groups requires tailored participatory methods. For example, the participatory toolkits for active school travel promotion (Case A) include planning activities that account for children’s diverse mobilities, such “wheeling” for children who use wheelchairs. It also offers indoor and outdoor activities suitable for different age groups and abilities, employing visual, drawing, and writing exercises to support various modes of expression. A diversity of participatory methods is also observed in the toolkit approach employed in Case F. Storytelling and collective storytelling approaches in Cases C and E further support the recognition of multiple subjectivities, allowing participants to express their experiences in their own terms and contribute meaningfully to the planning narrative. In Case C, in particular, the use of personas provides an additional layer of procedural and recognition justice while protecting the privacy of participants. Participants can choose how much personal information they want to share and can share their story using a persona instead of their real name and image for instance. For example, the city of Belfast in Case C opted for the use of personas to communicate the stories collected from the community.

6 Discussion

The SJ-3A3 framework presented in this paper proves to be a useful tool to make spatial justice explicit in participatory planning practice. The cases analysed also demonstrate that there is potential to integrate spatial justice considerations in urban planning through innovative, inclusive participatory practices. We argue that this is one step in the direction of addressing the disconnection between participatory instruments and planning practice.

However, for integrative approaches to be successful, it is crucial to develop processes that effectively integrate different types of knowledge and address questions of epistemic justice. Quantitative data associated with expert-based approaches is often prioritised over qualitative (thick) data emerging from participatory activities. The question of whose knowledge is valued also cuts across socio-economic status, gender, and race. Such hierarchies not only influence whose perspectives are included but also affect recognition and representation, which are core dimensions of spatial justice. In this regard, innovative approaches for knowledge integration, such as the Gluon model, designed to bridge disciplinary divides and foster collaboration across boundaries (Brand et al., 2025), offer potential ways forward for advancing both epistemic and spatial justice in planning.

More broadly, power dynamics in participatory planning must be acknowledged and addressed. Participation does not inherently result in more equitable or just planning outcomes (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2020). The SJ-3A3 framework can help make justice-related impacts explicit, but its use requires a critical and reflective approach as well as strategies to redistribute and reorganise decision-making power (Kleinhans et al., 2015; Roth et al., 2023; Yazar et al., 2025). Without this, participation risks reproducing existing socio-spatial dynamics rather than contributing to spatial justice outcomes. We therefore strongly caution against a superficial or procedural use of the framework, which would ultimately reinforce the status quo.

The cases analysed in this paper are associated with an innovation-driven research project, in which new methods and approaches were co-created with and piloted by municipalities. This demonstrates the potential of embedding justice considerations into participatory practices but also highlights limitations: cases were context-specific and reliant on preconditions of experimentation, such as motivated municipalities and available research funding. Concerns about “one-off” participation and tokenistic engagement, noted earlier in this paper, remain barriers to procedural justice, and by extension to spatial justice. The lack of continuity leads to frustration and erodes trust between public authorities and local actors, particularly marginalised groups (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2020; Gonçalves et al., 2024). Fully addressing the disconnection between participation and planning therefore requires dedicated efforts to embed innovative methods and approaches within existing practices (Goncalves et al., 2026), so that participation contributes systemically to spatial justice rather than temporary consultation.